transposon mutagenesis on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Transposon mutagenesis, or transposition mutagenesis, is a

The Tn5 transposon system is a model system for the study of transposition and for the application of transposon mutagenesis. Tn5 is a bacterial composite transposon in which genes (the original system containing

The Tn5 transposon system is a model system for the study of transposition and for the application of transposon mutagenesis. Tn5 is a bacterial composite transposon in which genes (the original system containing

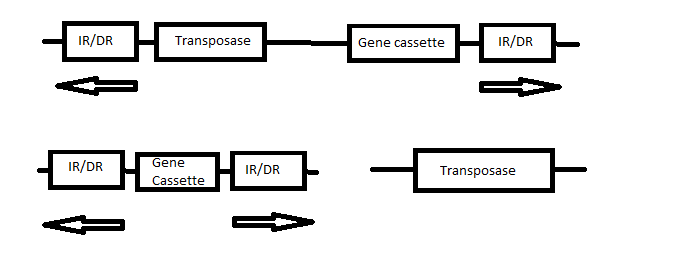

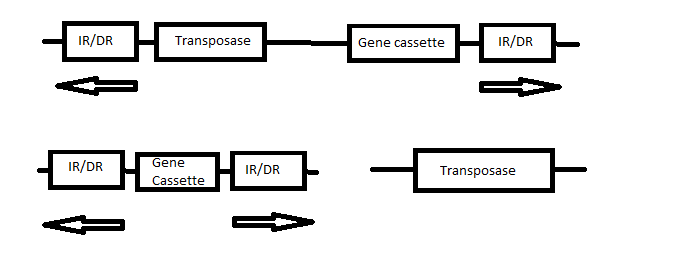

The mechanism of the SBTS is similar to the Tn5 transposon system, however the enzyme and gene sequences are eukaryotic in nature as opposed to prokaryotic. The system's tranposase can act in ''trans'' as well as in ''cis'', allowing a diverse collection of transposon structures. The transposon itself is flanked by inverted repeat sequences, which are each repeated twice in a direct fashion, designated IR/DR sequences. The internal region consists of the gene or sequence to be transposed, and could also contain the transposase gene. Alternatively, the transposase can be encoded on a separate plasmid or injected in its protein form. Yet another approach is to incorporate both the transposon and the transposase genes into a viral vector, which can target a cell or tissue of choice. The transposase protein is extremely specific in the sequences that it binds, and is able to discern its IR/DR sequences from a similar sequence by three base pairs. Once the enzyme is bound to both ends of the transposon, the IR/DR sequences are brought together and held by the transposase in a Synaptic Complex Formation (SCF). The formation of the SCF is a checkpoint ensuring proper cleavage.

The mechanism of the SBTS is similar to the Tn5 transposon system, however the enzyme and gene sequences are eukaryotic in nature as opposed to prokaryotic. The system's tranposase can act in ''trans'' as well as in ''cis'', allowing a diverse collection of transposon structures. The transposon itself is flanked by inverted repeat sequences, which are each repeated twice in a direct fashion, designated IR/DR sequences. The internal region consists of the gene or sequence to be transposed, and could also contain the transposase gene. Alternatively, the transposase can be encoded on a separate plasmid or injected in its protein form. Yet another approach is to incorporate both the transposon and the transposase genes into a viral vector, which can target a cell or tissue of choice. The transposase protein is extremely specific in the sequences that it binds, and is able to discern its IR/DR sequences from a similar sequence by three base pairs. Once the enzyme is bound to both ends of the transposon, the IR/DR sequences are brought together and held by the transposase in a Synaptic Complex Formation (SCF). The formation of the SCF is a checkpoint ensuring proper cleavage.

"Transposon Mutagenisis" - Food Ingredient News

* * {{cite journal , author=Cook WB, Miles D , title=Transposon mutagenesis of nuclear photosynthetic genes in ''Zea mays'' , journal=Photosyn. Res. , volume=18 , issue=1–2 , pages=33–59 , date=October 1988 , pmid=24425160 , doi=10.1007/BF00042979 , s2cid=7654879 Molecular biology Mobile genetic elements Mutagenesis

biological

Biology is the scientific study of life. It is a natural science with a broad scope but has several unifying themes that tie it together as a single, coherent field. For instance, all organisms are made up of cells that process hereditary in ...

process that allows genes to be transferred to a host organism's chromosome

A chromosome is a long DNA molecule with part or all of the genetic material of an organism. In most chromosomes the very long thin DNA fibers are coated with packaging proteins; in eukaryotic cells the most important of these proteins are ...

, interrupting or modifying the function of an extant

Extant is the opposite of the word extinct. It may refer to:

* Extant hereditary titles

* Extant literature, surviving literature, such as ''Beowulf'', the oldest extant manuscript written in English

* Extant taxon, a taxon which is not extinct, ...

gene

In biology, the word gene (from , ; "...Wilhelm Johannsen coined the word gene to describe the Mendelian units of heredity..." meaning ''generation'' or ''birth'' or ''gender'') can have several different meanings. The Mendelian gene is a ba ...

on the chromosome and causing mutation

In biology, a mutation is an alteration in the nucleic acid sequence of the genome of an organism, virus, or extrachromosomal DNA. Viral genomes contain either DNA or RNA. Mutations result from errors during DNA or viral replication, mi ...

. Transposon mutagenesis is much more effective than chemical mutagenesis, with a higher mutation frequency and a lower chance of killing the organism. Other advantages include being able to induce single hit mutations, being able to incorporate selectable marker A selectable marker is a gene introduced into a cell, especially a bacterium or to cells in culture, that confers a trait suitable for artificial selection. They are a type of reporter gene used in laboratory microbiology, molecular biology, and gen ...

s in strain construction, and being able to recover genes after mutagenesis. Disadvantages include the low frequency of transposition in living systems, and the inaccuracy of most transposition systems.

History

Transposon mutagenesis was first studied byBarbara McClintock

Barbara McClintock (June 16, 1902 – September 2, 1992) was an American scientist and cytogeneticist who was awarded the 1983 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. McClintock received her PhD in botany from Cornell University in 1927. There s ...

in the mid-20th century during her Nobel Prize-winning work with corn. McClintock received her BSc in 1923 from Cornell’s College of Agriculture. By 1927 she had her PhD in botany, and she immediately began working on the topic of maize

Maize ( ; ''Zea mays'' subsp. ''mays'', from es, maíz after tnq, mahiz), also known as corn (North American and Australian English), is a cereal grain first domesticated by indigenous peoples in southern Mexico about 10,000 years ago. Th ...

chromosomes. In the early 1940s, McClintock was studying the progeny of self-pollinated maize plants which resulted from crosses

Crosses may refer to:

* Cross, the symbol

Geography

* Crosses, Cher, a French municipality

* Crosses, Arkansas, a small community located in the Ozarks of north west Arkansas

Language

* Crosses, a truce term used in East Anglia and Lincolnshire ...

having a broken chromosome 9. These plants were missing their telomere

A telomere (; ) is a region of repetitive nucleotide sequences associated with specialized proteins at the ends of linear chromosomes. Although there are different architectures, telomeres, in a broad sense, are a widespread genetic feature mos ...

s. This research prompted the first discovery of a transposable element

A transposable element (TE, transposon, or jumping gene) is a nucleic acid sequence in DNA that can change its position within a genome, sometimes creating or reversing mutations and altering the cell's genetic identity and genome size. Transp ...

, and from there transposon mutagenesis have been exploited as a biological tool.

Dynamics

In the case ofbacteria

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were among ...

, transposition mutagenesis is usually accomplished by way of a plasmid

A plasmid is a small, extrachromosomal DNA molecule within a cell that is physically separated from chromosomal DNA and can replicate independently. They are most commonly found as small circular, double-stranded DNA molecules in bacteria; how ...

from which a transposon

A transposable element (TE, transposon, or jumping gene) is a nucleic acid sequence in DNA that can change its position within a genome, sometimes creating or reversing mutations and altering the cell's genetic identity and genome size. Transpo ...

is extracted and inserted into the host chromosome. This usually requires a set of enzyme

Enzymes () are proteins that act as biological catalysts by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different molecules known as products. A ...

s including transposase

A transposase is any of a class of enzymes capable of binding to the end of a transposon and catalysing its movement to another part of a genome, typically by a cut-and-paste mechanism or a replicative mechanism, in a process known as transposition ...

to be translated

Translation is the communication of the meaning of a source-language text by means of an equivalent target-language text. The English language draws a terminological distinction (which does not exist in every language) between ''transla ...

. The transposase can be expressed either on a separate plasmid, or on the plasmid containing the gene to be integrated. Alternatively, an injection of transposase mRNA

In molecular biology, messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) is a single-stranded molecule of RNA that corresponds to the genetic sequence of a gene, and is read by a ribosome in the process of Protein biosynthesis, synthesizing a protein.

mRNA is ...

into the host cell can induce translation and expression

Expression may refer to:

Linguistics

* Expression (linguistics), a word, phrase, or sentence

* Fixed expression, a form of words with a specific meaning

* Idiom, a type of fixed expression

* Metaphorical expression, a particular word, phrase, o ...

. Early transposon mutagenesis experiments relied on bacteriophage

A bacteriophage (), also known informally as a ''phage'' (), is a duplodnaviria virus that infects and replicates within bacteria and archaea. The term was derived from "bacteria" and the Greek φαγεῖν ('), meaning "to devour". Bacteri ...

s and conjugative bacterial plasmids for the insertion of sequences. These were very non-specific, and made it difficult to incorporate specific genes. A newer technique called shuttle mutagenesis uses specific cloned genes from the host species to incorporate genetic elements. Another effective approach is to deliver transposons through viral capsid

A capsid is the protein shell of a virus, enclosing its genetic material. It consists of several oligomeric (repeating) structural subunits made of protein called protomers. The observable 3-dimensional morphological subunits, which may or may ...

s. This facilitates integration into the chromosome and long-term transgene

A transgene is a gene that has been transferred naturally, or by any of a number of genetic engineering techniques, from one organism to another. The introduction of a transgene, in a process known as transgenesis, has the potential to change the ...

expression.

Tn5 transposon system

The Tn5 transposon system is a model system for the study of transposition and for the application of transposon mutagenesis. Tn5 is a bacterial composite transposon in which genes (the original system containing

The Tn5 transposon system is a model system for the study of transposition and for the application of transposon mutagenesis. Tn5 is a bacterial composite transposon in which genes (the original system containing antibiotic resistance

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) occurs when microbes evolve mechanisms that protect them from the effects of antimicrobials. All classes of microbes can evolve resistance. Fungi evolve antifungal resistance. Viruses evolve antiviral resistance. ...

genes) are flanked by two nearly identical insertion sequence Insertion element (also known as an IS, an insertion sequence element, or an IS element) is a short DNA sequence that acts as a simple transposon, transposable element. Insertion sequences have two major characteristics: they are small relative to o ...

s, named IS50R and IS50L corresponding to the right and left sides of the transposon respectively. The IS50R sequence codes for two proteins, Tnp and Inh. These two proteins are identical in sequence, save for the fact that Inh is lacking the 55 N-terminal

The N-terminus (also known as the amino-terminus, NH2-terminus, N-terminal end or amine-terminus) is the start of a protein or polypeptide, referring to the free amine group (-NH2) located at the end of a polypeptide. Within a peptide, the ami ...

amino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although hundreds of amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the alpha-amino acids, which comprise proteins. Only 22 alpha am ...

s. Tnp codes for a transposase for the entire system, and Inh encodes an inhibitor

Inhibitor or inhibition may refer to:

In biology

* Enzyme inhibitor, a substance that binds to an enzyme and decreases the enzyme's activity

* Reuptake inhibitor, a substance that increases neurotransmission by blocking the reuptake of a neurotra ...

of transposase. The DNA-binding domain

Domain may refer to:

Mathematics

*Domain of a function, the set of input values for which the (total) function is defined

**Domain of definition of a partial function

**Natural domain of a partial function

**Domain of holomorphy of a function

* Do ...

of Tnp resides in the 55 N-terminal amino acids, and so these residues are essential for function. The IS50R and IS50L sequences are both flanked by 19-base pair

A base pair (bp) is a fundamental unit of double-stranded nucleic acids consisting of two nucleobases bound to each other by hydrogen bonds. They form the building blocks of the DNA double helix and contribute to the folded structure of both DNA ...

elements on the inside and outside ends of the transposon, labelled IE and OE respectively. Mutation of these regions results in an inability of transposase genes to bind to the sequences. The binding interactions between transposase and these sequences is very complicated, and is affected by DNA methylation

DNA methylation is a biological process by which methyl groups are added to the DNA molecule. Methylation can change the activity of a DNA segment without changing the sequence. When located in a gene promoter, DNA methylation typically acts t ...

and other epigenetic

In biology, epigenetics is the study of stable phenotypic changes (known as ''marks'') that do not involve alterations in the DNA sequence. The Greek prefix '' epi-'' ( "over, outside of, around") in ''epigenetics'' implies features that are "o ...

marks. In addition, other proteins seem to be able to bind with and affect the transposition of the IS50 elements, such as DnaA.

The most likely pathway of Tn 5 transposition is the common pathway for all transposon systems. It begins with Tnp binding the OE and IE sequences of each IS50 sequence. The two ends are brought together, and through oligomer

In chemistry and biochemistry, an oligomer () is a molecule that consists of a few repeating units which could be derived, actually or conceptually, from smaller molecules, monomers.Quote: ''Oligomer molecule: A molecule of intermediate relativ ...

ization of DNA, the sequence is cut out of the chromosome. After introducing 9-base pair 5' ends in target DNA, the transposon and its incorporated genes are inserted into the target DNA, duplicating the regions on either end of the transposon. Genes of interest can be genetically engineered

Genetic engineering, also called genetic modification or genetic manipulation, is the modification and manipulation of an organism's genes using technology. It is a set of technologies used to change the genetic makeup of cells, including t ...

into the transposon system between the IS50 sequences. By placing the transposon under the control of a host promoter, the genes will be expressed. Incorporated genes usually include, in addition to the gene of interest, a selectable marker A selectable marker is a gene introduced into a cell, especially a bacterium or to cells in culture, that confers a trait suitable for artificial selection. They are a type of reporter gene used in laboratory microbiology, molecular biology, and gen ...

to identify transformants, a eukaryotic

Eukaryotes () are organisms whose cells have a nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, and many unicellular organisms, are Eukaryotes. They belong to the group of organisms Eukaryota or Eukarya, which is one of the three domains of life. Bacte ...

promoter/terminator

Terminator may refer to:

Science and technology

Genetics

* Terminator (genetics), the end of a gene for transcription

* Terminator technology, proposed methods for restricting the use of genetically modified plants by causing second generation s ...

(if expressing in a eukaryote), and 3' UTR sequences to separate genes in a polycistronic

A cistron is an alternative term for "gene". The word cistron is used to emphasize that genes exhibit a specific behavior in a cis-trans test; distinct positions (or loci) within a genome are cistronic.

History

The words ''cistron'' and ''gene ...

stretch of sequence.

Sleeping Beauty transposon system

TheSleeping Beauty transposon system

The ''Sleeping Beauty'' transposon system is a synthetic DNA transposon designed to introduce precisely defined DNA sequences into the chromosomes of vertebrate animals for the purposes of introducing new traits and to discover new genes and thei ...

(SBTS) is the first successful non-viral vector

Vector most often refers to:

*Euclidean vector, a quantity with a magnitude and a direction

*Vector (epidemiology), an agent that carries and transmits an infectious pathogen into another living organism

Vector may also refer to:

Mathematic ...

for incorporation of a gene cassette

In biology, a gene cassette is a type of mobile genetic element that contains a gene and a recombination site. Each cassette usually contains a single gene and tends to be very small; on the order of 500–1000 base pairs. They may exist incorpora ...

into a vertebrate

Vertebrates () comprise all animal taxa within the subphylum Vertebrata () ( chordates with backbones), including all mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish. Vertebrates represent the overwhelming majority of the phylum Chordata, ...

genome. Up until the development of this system, the major problems with non-viral gene therapy have been the intracellular breakdown of the transgene due to it being recognized as Prokaryote

A prokaryote () is a single-celled organism that lacks a nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. The word ''prokaryote'' comes from the Greek πρό (, 'before') and κάρυον (, 'nut' or 'kernel').Campbell, N. "Biology:Concepts & Connec ...

s and the inefficient delivery of the transgene into organ systems. The SBTS revolutionized these issues by combining the advantages of viruses and naked DNA. It consists of a transposon containing the cassette of genes to be expressed, as well as its own transposase enzyme. By transposing the cassette directly into the genome of the organism from the plasmid, sustained expression of the transgene can be attained. This can be further refined by enhancing the transposon sequences and the transposase enzymes used. SB100X is a hyperactive mammalian transposase which is roughly 100x more efficient than the typical first-generation transposase. Incorporation of this enzyme into the cassette results in even more sustained transgene expression (over one year). Additionally, transgenesis frequencies can be as high as 45% when using pronuclear injection into mouse zygote

A zygote (, ) is a eukaryotic cell formed by a fertilization event between two gametes. The zygote's genome is a combination of the DNA in each gamete, and contains all of the genetic information of a new individual organism.

In multicellula ...

s.

The mechanism of the SBTS is similar to the Tn5 transposon system, however the enzyme and gene sequences are eukaryotic in nature as opposed to prokaryotic. The system's tranposase can act in ''trans'' as well as in ''cis'', allowing a diverse collection of transposon structures. The transposon itself is flanked by inverted repeat sequences, which are each repeated twice in a direct fashion, designated IR/DR sequences. The internal region consists of the gene or sequence to be transposed, and could also contain the transposase gene. Alternatively, the transposase can be encoded on a separate plasmid or injected in its protein form. Yet another approach is to incorporate both the transposon and the transposase genes into a viral vector, which can target a cell or tissue of choice. The transposase protein is extremely specific in the sequences that it binds, and is able to discern its IR/DR sequences from a similar sequence by three base pairs. Once the enzyme is bound to both ends of the transposon, the IR/DR sequences are brought together and held by the transposase in a Synaptic Complex Formation (SCF). The formation of the SCF is a checkpoint ensuring proper cleavage.

The mechanism of the SBTS is similar to the Tn5 transposon system, however the enzyme and gene sequences are eukaryotic in nature as opposed to prokaryotic. The system's tranposase can act in ''trans'' as well as in ''cis'', allowing a diverse collection of transposon structures. The transposon itself is flanked by inverted repeat sequences, which are each repeated twice in a direct fashion, designated IR/DR sequences. The internal region consists of the gene or sequence to be transposed, and could also contain the transposase gene. Alternatively, the transposase can be encoded on a separate plasmid or injected in its protein form. Yet another approach is to incorporate both the transposon and the transposase genes into a viral vector, which can target a cell or tissue of choice. The transposase protein is extremely specific in the sequences that it binds, and is able to discern its IR/DR sequences from a similar sequence by three base pairs. Once the enzyme is bound to both ends of the transposon, the IR/DR sequences are brought together and held by the transposase in a Synaptic Complex Formation (SCF). The formation of the SCF is a checkpoint ensuring proper cleavage. HMGB1

High mobility group box 1 protein, also known as high-mobility group protein 1 (HMG-1) and amphoterin, is a protein that in humans is encoded by the ''HMGB1'' gene.

HMG-1 belongs to the high mobility group and contains a HMG-box domain.

Functio ...

is a non-histone

In biology, histones are highly basic proteins abundant in lysine and arginine residues that are found in eukaryotic cell nuclei. They act as spools around which DNA winds to create structural units called nucleosomes. Nucleosomes in turn are wr ...

protein from the host which is associated with eukaryotic chromatin. It enhances the preferential binding of the transposase to the IR/DR sequences and is likely essential for SCF complex formation/stability. Transposase cleaves the DNA at the target sites, generating 3' overhangs. The enzyme then targets TA dinucleotides in the host genome as target sites for integration. The same enzymatic catalytic site which cleaved the DNA is responsible for integrating the DNA into the genome, duplicating the region of the genome in the process. Although transposase is specific for TA dinucleotides, the high frequency of these pairs in the genome indicates that the transposon undergoes fairly random integration.

Practical applications

As a result of the capacity of transposon mutagenesis to incorporate genes into most areas of target chromosomes, there are a number of functions associated with the process. *Virulence

Virulence is a pathogen's or microorganism's ability to cause damage to a host.

In most, especially in animal systems, virulence refers to the degree of damage caused by a microbe to its host. The pathogenicity of an organism—its ability to ca ...

genes in viruses and bacteria can be discovered by disrupting genes and observing for a change in phenotype

In genetics, the phenotype () is the set of observable characteristics or traits of an organism. The term covers the organism's morphology or physical form and structure, its developmental processes, its biochemical and physiological proper ...

. This has importance in antibiotic

An antibiotic is a type of antimicrobial substance active against bacteria. It is the most important type of antibacterial agent for fighting bacterial infections, and antibiotic medications are widely used in the treatment and prevention of ...

production and disease control.

* Non-essential genes can be discovered by inducing transposon mutagenesis in an organism. The transformed genes can then be identified by performing PCR on the organism's recovered genome

In the fields of molecular biology and genetics, a genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding ge ...

using an ORF

ORF or Orf may refer to:

* Norfolk International Airport, IATA airport code ORF

* Observer Research Foundation, an Indian research institute

* One Race Films, a film production company founded by Vin Diesel

* Open reading frame, a portion of the ...

-specific primer

Primer may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Films

* ''Primer'' (film), a 2004 feature film written and directed by Shane Carruth

* ''Primer'' (video), a documentary about the funk band Living Colour

Literature

* Primer (textbook), a t ...

and a transposon-specific primer. Since transposons can incorporate themselves into non-coding regions of DNA, the ORF-specific primer ensures that the transposon interrupted a gene. Because the organism survived after homologous integration, the interrupted gene was clearly non-essential.

* Cancer-causing genes can be identified by genome-wide mutagenesis and screening of mutants containing tumours. Based on the mechanism and results of the mutation, cancer

Cancer is a group of diseases involving abnormal cell growth with the potential to invade or spread to other parts of the body. These contrast with benign tumors, which do not spread. Possible signs and symptoms include a lump, abnormal b ...

-causing genes can be identified as oncogene

An oncogene is a gene that has the potential to cause cancer. In tumor cells, these genes are often mutated, or expressed at high levels.

s or tumour-suppressor genes.

Specific examples

''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' virulence gene cluster identification

In 1999, the virulence genes associated with ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis

''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (M. tb) is a species of pathogenic bacteria in the family Mycobacteriaceae and the causative agent of tuberculosis. First discovered in 1882 by Robert Koch, ''M. tuberculosis'' has an unusual, waxy coating on its c ...

'' were identified through transposon mutagenesis-mediated gene knockout

A gene knockout (abbreviation: KO) is a genetic technique in which one of an organism's genes is made inoperative ("knocked out" of the organism). However, KO can also refer to the gene that is knocked out or the organism that carries the gene kno ...

. A plasmid named pCG113 containing kanamycin

Kanamycin A, often referred to simply as kanamycin, is an antibiotic used to treat severe bacterial infections and tuberculosis. It is not a first line treatment. It is used by mouth, injection into a vein, or injection into a muscle. Kanamycin ...

resistance genes and the IS''1096'' insertion sequence was engineered to contain variable 80-base pair tags. The plasmids were then transformed into ''M. tuberculosis'' cells by electroporation

Electroporation, or electropermeabilization, is a microbiology technique in which an electrical field is applied to cells in order to increase the permeability of the cell membrane, allowing chemicals, drugs, electrode arrays or DNA to be introdu ...

. Colonies were plated on kanamycin to select for resistant cells. Colonies that underwent random transposition events were identified by '' Bam'' HI digestion

Digestion is the breakdown of large insoluble food molecules into small water-soluble food molecules so that they can be absorbed into the watery blood plasma. In certain organisms, these smaller substances are absorbed through the small intest ...

and Southern blot

A Southern blot is a method used in molecular biology for detection of a specific DNA sequence in DNA samples. Southern blotting combines transfer of electrophoresis-separated DNA fragments to a filter membrane and subsequent fragment detecti ...

ting using an internal IS''1096'' DNA probe. Colonies were screened for attenuated multiplication to identify colonies with mutations in candidate virulence genes. Mutations leading to an attenuated phenotype were mapped by amplification of adjacent regions to the IS''1096'' sequences and compared with the published ''M. tuberculosis'' genome. In this instance transposon mutagenesis identified 13 pathogenic

In biology, a pathogen ( el, πάθος, "suffering", "passion" and , "producer of") in the oldest and broadest sense, is any organism or agent that can produce disease. A pathogen may also be referred to as an infectious agent, or simply a germ ...

loci in the ''M. tuberculosis'' genome which were not previously associated with disease. This is essential information in understanding the infectious cycle of the bacterium.

''PiggyBac (PB)'' transposon mutagenesis for cancer gene discovery

The '' PiggyBac'' (PB) transposon from the cabbage looper moth ''Trichoplusia'' ''ni'' was engineered to be highly active in mammalian cells, and is capable of genome-wide mutagenesis. Transposons contained both ''PB'' and ''Sleeping Beauty'' inverted repeats, in order to be recognized by both transposases and increase the frequency of transposition. In addition, the transposon contained promoter and enhancer elements, a splice donor and acceptors to allow gain- or loss-of-function mutations depending on the transposon's orientation, and bidirectionalpolyadenylation

Polyadenylation is the addition of a poly(A) tail to an RNA transcript, typically a messenger RNA (mRNA). The poly(A) tail consists of multiple adenosine monophosphates; in other words, it is a stretch of RNA that has only adenine bases. In euk ...

signals. The transposons were transformed into mouse cells ''in vitro

''In vitro'' (meaning in glass, or ''in the glass'') studies are performed with microorganisms, cells, or biological molecules outside their normal biological context. Colloquially called "test-tube experiments", these studies in biology an ...

'' and mutants containing tumours were analyzed. The mechanism of the mutation leading to tumour formation determined if the gene was classified as an oncogene or a tumour-suppressor gene. Oncogenes tended to be characterized by insertions in regions leading to overexpression of a gene, whereas tumour-suppressor genes were classified as such based on loss-of-function mutations. Since the mouse is a model organism for the study of human physiology and disease, this research will help lead to an increased understanding of cancer-causing genes and potential therapeutic targets.

See also

* Transposons as a genetic tool *Transposable element

A transposable element (TE, transposon, or jumping gene) is a nucleic acid sequence in DNA that can change its position within a genome, sometimes creating or reversing mutations and altering the cell's genetic identity and genome size. Transp ...

* Transposase

A transposase is any of a class of enzymes capable of binding to the end of a transposon and catalysing its movement to another part of a genome, typically by a cut-and-paste mechanism or a replicative mechanism, in a process known as transposition ...

* Barbara McClintock

Barbara McClintock (June 16, 1902 – September 2, 1992) was an American scientist and cytogeneticist who was awarded the 1983 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. McClintock received her PhD in botany from Cornell University in 1927. There s ...

References

External links

*"Transposon Mutagenisis" - Food Ingredient News

* * {{cite journal , author=Cook WB, Miles D , title=Transposon mutagenesis of nuclear photosynthetic genes in ''Zea mays'' , journal=Photosyn. Res. , volume=18 , issue=1–2 , pages=33–59 , date=October 1988 , pmid=24425160 , doi=10.1007/BF00042979 , s2cid=7654879 Molecular biology Mobile genetic elements Mutagenesis