Topaz, Utah on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Topaz War Relocation Center, also known as the Central Utah Relocation Center (Topaz) and briefly as the Abraham Relocation Center, was an American concentration camp which housed Americans of Japanese descent and immigrants who had come to the United States from Japan, called '' Nikkei''. President

In December 1941, the

In December 1941, the

After Topaz was closed, the land was sold and most of the buildings were auctioned off, disassembled, and removed from the site. Even the water pipes and utility poles were sold. Numerous foundations, concrete-lined excavations and other ground-level features can be seen at the various sites, but few buildings remain, and natural vegetation has taken over most of the abandoned areas.

In 1976, the Japanese American Citizens League placed a monument on the northwestern corner of the central area. On March 29, 2007,

After Topaz was closed, the land was sold and most of the buildings were auctioned off, disassembled, and removed from the site. Even the water pipes and utility poles were sold. Numerous foundations, concrete-lined excavations and other ground-level features can be seen at the various sites, but few buildings remain, and natural vegetation has taken over most of the abandoned areas.

In 1976, the Japanese American Citizens League placed a monument on the northwestern corner of the central area. On March 29, 2007,

The Topaz Museum digital archive

with links to photographs of camp, ''The Topaz Times'', and the elementary school diary

Doren Benjamin Boyce papers

MSS 7980

Duane L. Bishop conversations

MSS 2222

Walton LeGrande Law papers

MSS 8293 *From the J. Willard Marriott Library,

Topaz Oral Histories

Topaz Internment Camp Documents, 1942–1943

MSS 170, Merrill-Cazier Library,

War Relocation Authority Photographs of Japanese-American Evacuation and Resettlement

Hisako Hibi pictorial collection concerning the Tanforan Assembly Center and the Central Utah Relocation Center

Photographs from the Yoshiaki Moriwaki family papers

Topaz Times

at the

Franklin Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

signed Executive Order 9066 in February 1942, ordering people of Japanese ancestry to be incarcerated in what were euphemistically called "relocation centers" like Topaz during World War II. Most of the people incarcerated at Topaz came from the Tanforan Assembly Center

The Tanforan Assembly Center was created to temporarily detain nearly 8,000 Japanese Americans, mostly from the San Francisco Bay Area, under the auspices of Executive Order 9066. After the order was signed in February 1942, the Wartime Civil Cont ...

and previously lived in the San Francisco Bay Area

The San Francisco Bay Area, often referred to as simply the Bay Area, is a populous region surrounding the San Francisco, San Pablo, and Suisun Bay estuaries in Northern California. The Bay Area is defined by the Association of Bay Area Go ...

. The camp was opened in September 1942 and closed in October 1945.

The camp, approximately west of Delta, Utah

Delta is the largest city in Millard County, Utah, United States. It is located in the northeastern area of Millard County along the Sevier River and is surrounded by farmland. The population was 3,436 at the 2010 census.

History

Delta was ori ...

, consisted of , with a main living area. Most internees lived in the main living area, though some lived off-site as agricultural and industrial laborers. The approximately 9,000 internees and staff made Topaz into the fifth-largest city in Utah at the time. The extreme temperature fluctuations of the arid area combined with uninsulated barracks made conditions very uncomfortable, even after the belated installation of pot-bellied stoves. The camp housed two elementary schools and a high school, a library, and some recreational facilities. Camp life was documented in a newspaper, ''Topaz Times'', and in the literary publication ''Trek''. Internees worked inside and outside the camp, mostly in agricultural labor. Many internees became notable artists.

In the winter of 1942–1943, a loyalty questionnaire asked prisoners if they would declare their loyalty to the United States of America and if they would be willing to enlist. The questions were divisive, and prisoners who were considered "disloyal" because of their answers on the loyalty questionnaire were sent to the Tule Lake

Tule Lake ( ) is an intermittent lake covering an area of , long and across, in northeastern Siskiyou County and northwestern Modoc County in California, along the border with Oregon.

Geography

Tule Lake is fed by the Lost River. The eleva ...

Segregation Camp. One internee, James Wakasa, was shot and killed for being too close to the camp's fence. Topaz prisoners held a large funeral and stopped working until administrators relaxed security.

In 1983, Jane Beckwith founded the Topaz Museum Board. Topaz became a U.S. National Historic Landmark

A National Historic Landmark (NHL) is a building, district, object, site, or structure that is officially recognized by the United States government for its outstanding historical significance. Only some 2,500 (~3%) of over 90,000 places listed ...

in 2007. After many years of organizing, fundraising, and collecting information and artifacts, the Topaz Museum was built in Delta and debuted with a display of the art created at Topaz. Permanent exhibits, installed in 2017, chronicle the people who were interned there and tell their stories.

Terminology

Since the end of World War II, there has been debate over the terminology used to refer to Topaz and the other camps in which Americans of Japanese ancestry and their immigrant parents were imprisoned by theUnited States government

The federal government of the United States (U.S. federal government or U.S. government) is the national government of the United States, a federal republic located primarily in North America, composed of 50 states, a city within a fede ...

during the war. Topaz has been referred to as a "relocation camp," "relocation center," "internment camp

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simply ...

," and "concentration camp

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simply ...

," and the controversy over which term is the most accurate and appropriate continued throughout the late 1990s. In a preface to a 1997 book on Topaz written and published by the Topaz Museum, the Topaz Museum Board informs readers that it is accurate to refer to the camps as a "detention camp" or "concentration camp" and its residents as "prisoners" or "internees".

History

In December 1941, the

In December 1941, the Imperial Japan

The also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was a historical nation-state and great power that existed from the Meiji Restoration in 1868 until the enactment of the post-World War II 1947 constitution and subsequent forma ...

attacked Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service upon the United States against the naval base at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Territory of Hawaii, j ...

in Hawaii. Shortly afterwards in February 1942, President Franklin Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

signed Executive Order 9066. The order forced approximately 120,000 Americans of Japanese descent (''Nisei

is a Japanese-language term used in countries in North America and South America to specify the ethnically Japanese children born in the new country to Japanese-born immigrants (who are called ). The are considered the second generation, ...

'') and Japanese-born residents (''Issei

is a Japanese-language term used by ethnic Japanese in countries in North America and South America to specify the Japanese people who were the first generation to immigrate there. are born in Japan; their children born in the new country are ...

'') in California

California is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, located along the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the List of states and territori ...

, Oregon

Oregon () is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. The Columbia River delineates much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while the Snake River delineates much of it ...

, Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered o ...

, and Alaska

Alaska ( ; russian: Аляска, Alyaska; ale, Alax̂sxax̂; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, Anáaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U.S., ...

on the West Coast of the United States

The West Coast of the United States, also known as the Pacific Coast, Pacific states, and the western seaboard, is the coastline along which the Western United States meets the North Pacific Ocean. The term typically refers to the contiguous U.S ...

to leave their homes. About 5,000 left the off-limits area during the "voluntary evacuation" period, and avoided internment

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simpl ...

. The remaining 110,000 were soon removed from their homes by Army and National Guard troops.

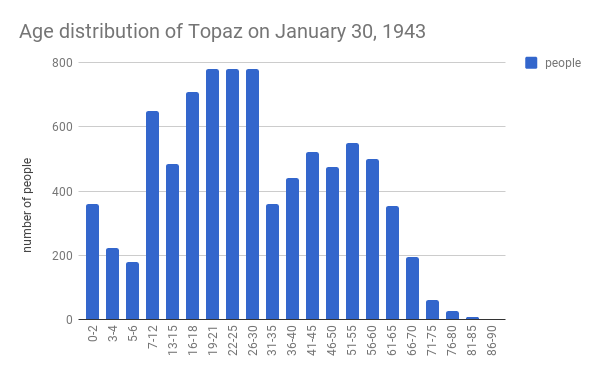

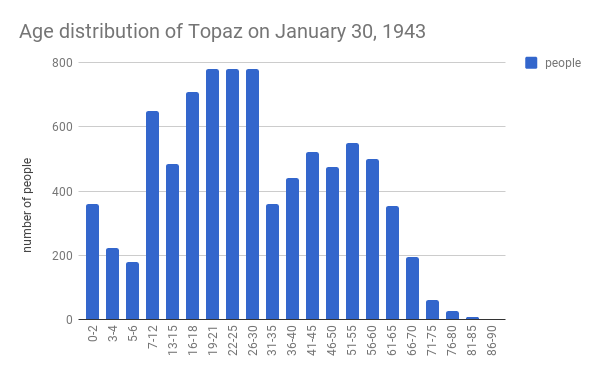

Topaz was opened September 11, 1942, and eventually became the fifth-largest city in Utah, with over 9,000 internees and staff, and covering approximately (mostly used for agriculture). A total of 11,212 people lived at Topaz at one time or another. Utah governor Herbert B. Maw opposed the relocation of any Japanese Americans into the state, stating that if they were such a danger to the West Coast, they would be a danger to Utah. Most internees arrived at Topaz from the Tanforan

The Shops at Tanforan is a regional shopping mall in San Bruno, California, United States. It is located on the San Francisco Peninsula, south of San Francisco city limits.

The site was originally used as a horse racing track from 1899 until 1 ...

or Santa Anita Assembly Centers; the majority hailed from the San Francisco Bay Area. Sixty-five percent were ''Nisei'', American citizens born to Japanese immigrants. The camp was governed by Charles F. Ernst until June 1944, when the position was taken over by Luther T. Hoffman following Ernst's resignation. It was closed on October 31, 1945.

Topaz was originally known as the Central Utah Relocation Authority, and then the Abraham Relocation Authority, but the names were too long for post office regulations. The final name, Topaz, came from Topaz Mountain

Topaz Mountain is a summit in the Thomas Range of Utah, east of the Thomas caldera. The summit and surrounding area are known for their abundances of semiprecious minerals including topaz, red beryl and opal.

Geology and geography

Topaz Mounta ...

which overlooks the camp from away.

Topaz was the primary internment site in the state of Utah

Utah ( , ) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. Utah is a landlocked U.S. state bordered to its east by Colorado, to its northeast by Wyoming, to its north by Idaho, to its south by Arizona, and to it ...

. A smaller camp existed briefly a few miles north of Moab

Moab ''Mōáb''; Assyrian: 𒈬𒀪𒁀𒀀𒀀 ''Mu'abâ'', 𒈠𒀪𒁀𒀀𒀀

''Ma'bâ'', 𒈠𒀪𒀊 ''Ma'ab''; Egyptian: 𓈗𓇋𓃀𓅱𓈉 ''Mū'ībū'', name=, group= () is the name of an ancient Levantine kingdom whose territo ...

, which was used to isolate a few men considered to be troublemakers prior to their being sent to Leupp, Arizona. A site at Antelope Springs, in the mountains west of Topaz, was used as a recreation area by the residents and staff of Topaz.

Life

Climate

Most internees came from the San Francisco Bay Area, which has awarm-summer Mediterranean climate

A Mediterranean climate (also called a dry summer temperate climate ''Cs'') is a temperate climate sub-type, generally characterized by warm, dry summers and mild, fairly wet winters; these weather conditions are typically experienced in the ...

, with moist mild winters and dry summers. Topaz had an extreme climate, located at above sea level in the Sevier Desert

The Sevier Desert is a large arid section of central-west Utah, United States, and is located in the southeast of the Great Basin. It is bordered by deserts north, west, and south; its east border is along the mountain range and valley sequences ...

. A "Midlatitude Desert" under the Köppen classification Köppen is a German surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* Bernd Köppen (born 1951), German pianist and composer

* Carl Köppen (1833-1907), German military advisor in Meiji era Japan

* Edlef Köppen (1893–1939), German author an ...

, temperatures could vary greatly throughout the day. The area experienced powerful winds and dust storms. One such storm caused structural damage to 75 buildings in 1944. Temperatures could reach below freezing from mid-September until the end of May. The average temperature in January was . Spring rains turned the clay soil to mud, which bred mosquitoes. Summers were hot, with occasional thunderstorms and temperatures that could exceed . In 1942, the first snowfall occurred on October 13, before camp construction was fully complete.

Architecture and living arrangements

Topaz contained a living complex known as the "city", about , as well as extensive agricultural lands. Within the city, forty-two blocks were for internees, thirty-four of which were residential. Each residential block housed 200–300 people, housed in barracks that held five people within a single room. Families were generally housed together, while single adults would be housed with four other unrelated individuals. Residential blocks also contained a recreation hall, a mess hall, an office for the block manager, and a combined laundry/toilet/bathing facility. Each block contained only four bathtubs for all the women and four showers for all the men living there. These packed conditions often resulted in little privacy for residents. Barracks were built out of wood frame covered intarpaper

Tar paper is a heavy-duty paper used in construction. Tar paper is made by impregnating paper or fiberglass mat with tar, producing a waterproof material useful for roof construction. Tar paper is distinguished from roofing felt, which is impreg ...

, with wooden floors. Many internees moved into the barracks before they were completed, exposing them to harsh weather. Eventually, they were lined with sheetrock

Drywall (also called plasterboard, dry lining, wallboard, sheet rock, gypsum board, buster board, custard board, and gypsum panel) is a panel made of calcium sulfate dihydrate (gypsum), with or without additives, typically extruded between thick ...

, and the floors filled with masonite

Masonite is a type of hardboard, a kind of engineered wood, which is made of steam-cooked and pressure-molded wood fibers in a process patented by William H. Mason. It is also called Quartrboard, Isorel, hernit, karlit, torex, treetex, and pr ...

. While the construction began in July 1942, the first inmates moved in in September 1942, and the camp was not completed until early 1943. Camp construction was completed in part by 214 interned laborers who volunteered to arrive early and help build the camp. Rooms were heated by pot-bellied stoves. There was no furniture provided. Inmates used communal leftover scrap wood from construction to build beds, tables, and cabinets. Some families also modified their living quarters with fabric partitions. Water came from wells and was stored in a large wooden tank, and was "almost undrinkable" because of its alkalinity.

Topaz also included a number of communal areas: a high school, two elementary schools, a 28-bed hospital, at least two churches, and a community garden. There was a cemetery as well, although it was never used. All 144 people who died in the camp were cremated and their ashes were held for burial until after the war. The camp was patrolled by 85–150 policemen, and was surrounded by a barbed wire fence. Manned watchtowers with searchlights were placed every surrounding the perimeter of the camp.

Daily life

The camp was designed to be self-sufficient, and the majority of land within the camp was devoted to farming. Topaz inmates raised cattle, pigs, and chickens in addition to feed crops and vegetables. The vegetables were high-quality and won awards at the Millard County Fair. Due to harsh weather, poor soil, and short growing conditions, the camp was not able to supply all of its animal feed. Topaz contained two elementary schools: Desert View Elementary and Mountain View Elementary. Topaz High School educated students grades 7–12, and there was also an adult education program. The schools were taught by a combination of local teachers and internees. They were under-equipped and overcrowded, but enthusiastic teachers did their best. Topaz High School developed a devoted community, with frequent reunions after internment ended, and a final reunion in 2012. Sports were popular within the schools as well as the adult population, with sports includingbaseball

Baseball is a bat-and-ball sport played between two teams of nine players each, taking turns batting and fielding. The game occurs over the course of several plays, with each play generally beginning when a player on the fielding tea ...

, basketball, and sumo

is a form of competitive full-contact wrestling where a ''rikishi'' (wrestler) attempts to force his opponent out of a circular ring (''dohyō'') or into touching the ground with any body part other than the soles of his feet (usually by thr ...

wrestling. Cultural associations sprung up throughout the camp. Topaz had a newspaper called the ''Topaz Times'', a literary publication called ''Trek'', and two libraries which eventually contained almost 7,000 items in both English and Japanese. Artist Chiura Obata

was a well-known Japanese-American artist and popular art teacher. A self-described "roughneck", Obata went to the United States in 1903, at age 17. After initially working as an illustrator and commercial decorator, he had a successful career a ...

led the Tanforan Art School at Topaz, offering art instruction to over 600 students. Internment rules usurped parental authority, and teenagers often ate meals with their friends and only joined their families to sleep at night. This combined with a lack of privacy made it difficult for parents to discipline and bond with their children, which contributed to teenage delinquency in the camp.

Some internees were permitted to leave the camp to find employment. In 1942, internees were able to get permission to leave the camp for employment in nearby Delta, where they filled labor shortages caused by the draft, mostly in agricultural labor. In 1943 over 500 internees obtained seasonal agricultural work outside the camp, with another 130 working in domestic and industrial jobs. Polling showed that a majority of Utahns supported this policy. One teacher at the camp art school, Chiura Obata, was allowed to leave Topaz to run classes at nearby universities and churches.

Internees were also sometimes permitted to leave the camp for recreation. A former Civilian Conservation Corps

The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) was a voluntary government work relief program that ran from 1933 to 1942 in the United States for unemployed, unmarried men ages 18–25 and eventually expanded to ages 17–28. The CCC was a major part of ...

camp at Antelope Springs, in mountains to the west, was taken over as a recreation area for internees and camp staff, and two buildings from Antelope Springs were brought to the central area to be used as Buddhist and Christian churches. During a rock hunting expedition in the Drum Mountains

The Drum Mountains or Detroit Mountains are a desert range in Juab and Millard counties of western Utah. They lie within the Basin and Range Province, which is a series of generally north-south trending mountain ranges and valleys (or basins) ex ...

, west of Topaz, Akio Uhihera and Yoshio Nishimoto discovered and excavated a rare iron meteorite, which the Smithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums and education and research centers, the largest such complex in the world, created by the U.S. government "for the increase and diffusion of knowledge". Founded ...

acquired.

Camp politics

In 1943, the War Relocation Authority (WRA) issued all adult internees a questionnaire assessing their level of Americanization. It was entitled "Application for Leave Clearance". Questions asked about what language they spoke most frequently, their religion, and recreational activities. Participating in judo and kendo were "Japanese" activities, while playing baseball or being Christian were considered "American". Two questions asked prisoners if they were willing to fight in the US Armed Forces and if they would swear allegiance to the United States and renounce loyalty to the Emperor of Japan. Many Japanese-bornIssei

is a Japanese-language term used by ethnic Japanese in countries in North America and South America to specify the Japanese people who were the first generation to immigrate there. are born in Japan; their children born in the new country are ...

, who were barred from attaining American citizenship, resented the second question, feeling that an affirmative answer would leave them effectively stateless. Some Issei volunteered to join the army, even though there was no enlistment procedure for non-citizens. Others objected on other political grounds. In Topaz, nearly a fifth of male residents answered "no" to the question about allegiance. Inmates expressed their anger through a few scattered assaults against other inmates who they perceived as too close to the administration. Chiura Obata was among those attacked, resulting in his immediate release for fear of further assaults. A reworded version of the questionnaire for Issei did not require them to renounce their loyalty to the emperor of Japan. In response to the questionnaires, some Nisei formed the Resident Council for Japanese American Civil Rights, which encouraged other prisoners to register for the draft if their civil rights were restored.

A military sentry fatally shot 63-year-old chef James Hatsuaki Wakasa on April 11, 1943, while he was walking his dog inside the camp fence. Internees went on strike protesting the death and surrounding secrecy. They held a large funeral for Wakasa as a way to express their outrage. In response, the administration determined that fears of subversive activity at the camp were largely without basis, and significantly relaxed security. The military decided that officers who had been at war in the Pacific would not be assigned to guard duty at Topaz. The guard who shot Wakasa was reassigned after being found not guilty of violating military law; this information was not given to internees.

Topaz internees Fred Korematsu

was an American civil rights activist who resisted the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II. Shortly after the Imperial Japanese Navy launched its attack on Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive O ...

and Mitsuye Endo

Mitsuye Maureen Endo Tsutsumi (May 10, 1920 – April 14, 2006) was an American woman of Japanese descent who was placed in an internment camp during World War II. Endo filed a writ of habeas corpus that ultimately led to a United States Supre ...

challenged their internment in court. Korematsu's case was heard and rejected at the US Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point of ...

('' Korematsu v. United States''), the largest case to challenge internment, while Endo's case was upheld.

After closing

After Topaz was closed, the land was sold and most of the buildings were auctioned off, disassembled, and removed from the site. Even the water pipes and utility poles were sold. Numerous foundations, concrete-lined excavations and other ground-level features can be seen at the various sites, but few buildings remain, and natural vegetation has taken over most of the abandoned areas.

In 1976, the Japanese American Citizens League placed a monument on the northwestern corner of the central area. On March 29, 2007,

After Topaz was closed, the land was sold and most of the buildings were auctioned off, disassembled, and removed from the site. Even the water pipes and utility poles were sold. Numerous foundations, concrete-lined excavations and other ground-level features can be seen at the various sites, but few buildings remain, and natural vegetation has taken over most of the abandoned areas.

In 1976, the Japanese American Citizens League placed a monument on the northwestern corner of the central area. On March 29, 2007, United States Secretary of the Interior

The United States secretary of the interior is the head of the United States Department of the Interior. The secretary and the Department of the Interior are responsible for the management and conservation of most federal land along with natural ...

Dirk Kempthorne

Dirk Arthur Kempthorne (born October 29, 1951) is an American politician who served as the 49th United States Secretary of the Interior from 2006 to 2009 under President George W. Bush. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a ...

designated "Central Utah Relocation Center Site" a National Historic Landmark

A National Historic Landmark (NHL) is a building, district, object, site, or structure that is officially recognized by the United States government for its outstanding historical significance. Only some 2,500 (~3%) of over 90,000 places listed ...

.

In 1982, Delta High School teacher Jane Beckwith and her journalism students began to study Topaz. She spearheaded the creation of the Topaz Museum Board in 1983, which oversaw the Topaz Museum, which initially shared space with the Great Basin Museum. Funding from the Japanese-American Confinement Sites organization enabled the Topaz Board to construct its own museum building in 2013. In 2015, the museum formally opened with an exhibition of art created at Topaz, entitled "When Words Weren't Enough: Works on Paper from Topaz, 1942–1945". The museum closed for remodeling in November 2016, and reopened in 2017 as a traditional museum focused on the history of Topaz. By 2017, the Topaz Museum and Board had purchased 634 of the 640 acres of the original internment site.

In media

In film

Using a smuggled camera,Dave Tatsuno

Dave Tatsuno (born Masaharu Tatsuno August 18, 1913 – January 26, 2006, in California) was a Japanese American businessman who documented life in his family's internment camp during World War II. His footage was later compiled into the film ...

shot film of Topaz. The documentary ''Topaz

Topaz is a silicate mineral of aluminium and fluorine with the chemical formula Al Si O( F, OH). It is used as a gemstone in jewelry and other adornments. Common topaz in its natural state is colorless, though trace element impurities can mak ...

'' uses film he shot from 1943 to 1945. This film was an inductee of the 1997 National Film Registry

The National Film Registry (NFR) is the United States National Film Preservation Board's (NFPB) collection of films selected for preservation, each selected for its historical, cultural and aesthetic contributions since the NFPB’s inception i ...

list, with the added distinction of being the second "home movie

A home movie is a short amateur film or video typically made just to preserve a visual record of family activities, a vacation, or a special event, and intended for viewing at home by family and friends. Originally, home movies were made on ph ...

" to be included on the Registry and the only color footage of camp life.

Topaz War Relocation Center is the setting for the 2007 film '' American Pastime'', a dramatization based on actual events, which tells the story of ''Nikkei'' baseball in the camps. A portion of the camp was duplicated for location shooting in Utah's Skull Valley, approximately west of Salt Lake City and north of the actual Topaz site. The film used some of Tatsuno's historical footage. In addition to Tatsuno's ''Topaz

Topaz is a silicate mineral of aluminium and fluorine with the chemical formula Al Si O( F, OH). It is used as a gemstone in jewelry and other adornments. Common topaz in its natural state is colorless, though trace element impurities can mak ...

'', Ken Verdoia made a 1987 documentary, also entitled ''Topaz''.

In literature

Yoshiko Uchida

Yoshiko Uchida (November 24, 1921 – June 21, 1992) was an award-winning Japanese American writer of children's books based on aspects of Japanese and Japanese American history and culture. A series of books, starting with ''Journey to Topaz'' ...

's young adult novel ''Journey to Topaz'' (published in 1971) recounts the story of Yuki, a young Japanese American girl, whose world is disrupted when, shortly after Pearl Harbor, she and her family must leave their comfortable home in the Berkeley, California

Berkeley ( ) is a city on the eastern shore of San Francisco Bay in northern Alameda County, California, United States. It is named after the 18th-century Irish bishop and philosopher George Berkeley. It borders the cities of Oakland and Emer ...

suburbs for the dusty barracks of Topaz. The book is largely based on Uchida's personal experiences: she and her family were interned at Topaz for three years.

Julie Otsuka

Julie Otsuka is an American author.

Biography

Otsuka was born in 1962, in Palo Alto, California. Her father worked as an aerospace engineer and her mother worked as a lab technician before she gave birth to Otsuka. Both of her parents were of Ja ...

's novel '' When the Emperor was Divine'' (published in 2002) tells the story of a family forced to relocate from Berkeley to Topaz in September 1942. Each of the novel's five chapters is told from the point of view of a different character. Critics praised the book's "precise but poetic evocation of the ordinary" and "ability to empathize".

In his poetry collection ''Topaz'' (published in 2013), Brian Komei Dempster examines the experience of his mother and her family, tying the history of persecution and internment to subsequent generations’ search for a 21st-century identity.

In art

Much of the art made by detainees at the camp depicted life there, and survives. Drawings and woodcuts by Chiura Obata and Matsusaburō (George) Hibi are among the most prominent. Some of it is collected in ''The Art of Gaman: Arts and Crafts from the Japanese American Internment Camps, 1942–1946'' by Delphine Hirasuna, and has been exhibited in Topaz and at the Wight Art Gallery. In 2018, the Utah Museum of Fine Arts exhibited many Chiura Obata's works, including some made at Topaz.See also

*Japanese American Internment

Japanese may refer to:

* Something from or related to Japan, an island country in East Asia

* Japanese language, spoken mainly in Japan

* Japanese people, the ethnic group that identifies with Japan through ancestry or culture

** Japanese diaspor ...

* List of inmates of Topaz War Relocation Center

This is a list of inmates of Topaz War Relocation Center, an American concentration camp in Utah used during World War II to hold people of Japanese descent.

*Karl Ichiro Akiya (1909–2001), a writer and political activist.

*Richard Aoki (1938� ...

References

External links

The Topaz Museum digital archive

with links to photographs of camp, ''The Topaz Times'', and the elementary school diary

Archival links

*Papers from non-internee people at Topaz from the L. Tom Perry Special Collections,Harold B. Lee Library

The Harold B. Lee Library (HBLL) is the main academic library of Brigham Young University (BYU) located in Provo, Utah. The library started as a small collection of books in the president's office in 1876 before moving in 1891. The Heber J. Gr ...

, Brigham Young University

Brigham Young University (BYU, sometimes referred to colloquially as The Y) is a private research university in Provo, Utah. It was founded in 1875 by religious leader Brigham Young and is sponsored by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day ...

:

Doren Benjamin Boyce papers

MSS 7980

Duane L. Bishop conversations

MSS 2222

Walton LeGrande Law papers

MSS 8293 *From the J. Willard Marriott Library,

University of Utah

The University of Utah (U of U, UofU, or simply The U) is a public research university in Salt Lake City, Utah. It is the flagship institution of the Utah System of Higher Education. The university was established in 1850 as the University of De ...

Topaz Oral Histories

Topaz Internment Camp Documents, 1942–1943

MSS 170, Merrill-Cazier Library,

Utah State University

Utah State University (USU or Utah State) is a public land-grant research university in Logan, Utah. It is accredited by the Northwest Commission on Colleges and Universities. With nearly 20,000 students living on or near campus, USU is Utah's ...

*Collections from the University of California Calisphere:

War Relocation Authority Photographs of Japanese-American Evacuation and Resettlement

Bancroft Library

The Bancroft Library in the center of the campus of the University of California, Berkeley, is the university's primary special-collections library. It was acquired from its founder, Hubert Howe Bancroft, in 1905, with the proviso that it retai ...

Hisako Hibi pictorial collection concerning the Tanforan Assembly Center and the Central Utah Relocation Center

Japanese American National Museum

The is located in Los Angeles, California, and dedicated to preserving the history and culture of Japanese Americans. Founded in 1992, it is located in the Little Tokyo area near downtown. The museum is an affiliate within the Smithsonian Affil ...

Photographs from the Yoshiaki Moriwaki family papers

The Bancroft Library

The Bancroft Library in the center of the campus of the University of California, Berkeley, is the university's primary special-collections library. It was acquired from its founder, Hubert Howe Bancroft, in 1905, with the proviso that it retai ...

Topaz Times

at the

Library of Congress

The Library of Congress (LOC) is the research library that officially serves the United States Congress and is the ''de facto'' national library of the United States. It is the oldest federal cultural institution in the country. The library is ...

{{Authority control

1942 establishments in Utah

1945 disestablishments in Utah

Buildings and structures in Millard County, Utah

Great Basin National Heritage Area

Internment camps for Japanese Americans

National Historic Landmarks in Utah

Prisons in Utah

World War II on the National Register of Historic Places

Temporary populated places on the National Register of Historic Places

Buddhism in Utah

Harold B. Lee Library-related 20th century articles