Timeline Of The Development Of Tectonophysics (after 1952) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The evolution of

* 1953, the

* 1953, the

* John F. Dewey applies Plate tectonics .

* Plate tectonics:

**

* John F. Dewey applies Plate tectonics .

* Plate tectonics:

**

Global plate reconstructions

with velocity fields from 150 Ma to present in 10 Ma increments.

Actually, there were two main "schools of thought" that pushed

Actually, there were two main "schools of thought" that pushed

tectonophysics

Tectonophysics, a branch of geophysics, is the study of the physical processes that underlie tectonic deformation. The field encompasses the spatial patterns of stress, strain, and differing rheologies in the lithosphere and asthenosphere of the ...

is closely linked to the history of the continental drift

Continental drift is the hypothesis that the Earth's continents have moved over geologic time relative to each other, thus appearing to have "drifted" across the ocean bed. The idea of continental drift has been subsumed into the science of pla ...

and plate tectonics

Plate tectonics (from the la, label=Late Latin, tectonicus, from the grc, τεκτονικός, lit=pertaining to building) is the generally accepted scientific theory that considers the Earth's lithosphere to comprise a number of large ...

hypotheses

A hypothesis (plural hypotheses) is a proposed explanation for a phenomenon. For a hypothesis to be a scientific hypothesis, the scientific method requires that one can test it. Scientists generally base scientific hypotheses on previous obser ...

. The continental drift/ Airy-Heiskanen isostasy

Isostasy (Greek ''ísos'' "equal", ''stásis'' "standstill") or isostatic equilibrium is the state of gravitational equilibrium between Earth's crust (or lithosphere) and mantle such that the crust "floats" at an elevation that depends on its ...

hypothesis had many flaws and scarce data. The fixist/ Pratt-Hayford isostasy, the contracting Earth and the expanding Earth concepts had many flaws as well.

The idea of continents with a permanent location, the geosyncline theory, the Pratt-Hayford isostasy, the extrapolation of the age of the Earth by Lord Kelvin as a black body cooling down, the contracting Earth, the Earth as a solid and crystalline body, is one school of thought. A lithosphere creeping over the asthenosphere is a logical consequence of an Earth with internal heat by radioactivity decay, the Airy-Heiskanen isostasy, thrust fault

A thrust fault is a break in the Earth's crust, across which older rocks are pushed above younger rocks.

Thrust geometry and nomenclature

Reverse faults

A thrust fault is a type of reverse fault that has a dip of 45 degrees or less.

If ...

s and Niskanen's mantle

A mantle is a piece of clothing, a type of cloak. Several other meanings are derived from that.

Mantle may refer to:

*Mantle (clothing), a cloak-like garment worn mainly by women as fashionable outerwear

**Mantle (vesture), an Eastern Orthodox ve ...

viscosity determinations.

Making sense of the puzzle pieces

Great Global Rift

A mid-ocean ridge (MOR) is a seafloor mountain system formed by plate tectonics. It typically has a depth of about and rises about above the deepest portion of an ocean basin. This feature is where seafloor spreading takes place along a diver ...

, running along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, was discovered by Bruce Heezen

Bruce Charles Heezen (; April 11, 1924 – June 21, 1977) was an American geologist. He worked with oceanographic cartographer Marie Tharp at Columbia University to map the Mid-Atlantic Ridge in the 1950s.

Biography

Heezen was born in Vinton, Io ...

( Lamont Group) (Puzzle pieces: Seismic-refraction and Sonar survey of the rifts). , , , ,

** Their world ocean floor map was published 1977. Austrian painter Heinrich Berann worked on it.

** Nowadays the seafloor maps have a better resolution by the SEASAT

Seasat was the first Earth-orbiting satellite designed for remote sensing of the Earth's oceans and had on board one of the first spaceborne synthetic-aperture radar (SAR). The mission was designed to demonstrate the feasibility of global satelli ...

, Geosat

The GEOSAT (GEOdetic SATellite) was a U.S. Navy Earth observation satellite, launched on March 12, 1985 into an 800 km, 108° inclination orbit, with a nodal period of about 6040 seconds. The satellite carried a radar altimeter capable of m ...

/ERM and ERS-1/ERM (European Remote-Sensing Satellite

European Remote Sensing satellite (ERS) was the European Space Agency's first Earth-observing satellite programme using a polar orbit. It consisted of 2 satellites, ERS-1 and ERS-2.

ERS-1

ERS-1 launched 17 July 1991 from Guiana Space Centre ...

/Exact Repeat Mission) missions.

* World map of earthquake epicenters, oceanic ones mainly .

* 1954–1963: Alfred Rittmann was elected IAV

IAV GmbH Ingenieurgesellschaft Auto und Verkehr, (literal ''Engineer Society Automobile and Traffic''), abbreviated to IAV GmbH, is an engineering company in the automotive industry, designing products for powertrain, electronics and vehicle de ...

President (IAV at that time) for three periods.

* 1956, S. K. Runcorn becomes a drifter. ,

** Statistics by Ronald Fisher

Sir Ronald Aylmer Fisher (17 February 1890 – 29 July 1962) was a British polymath who was active as a mathematician, statistician, biologist, geneticist, and academic. For his work in statistics, he has been described as "a genius who a ...

. ,

** Jan Hospers work (magnetic poles and geographical poles coincide the last 23 Ma).

** Self-exciting dynamo theory

In physics, the dynamo theory proposes a mechanism by which a celestial body such as Earth or a star generates a magnetic field. The dynamo theory describes the process through which a rotating, convecting, and electrically conducting fluid can ...

of Elsasser- Bullard.

* S. W. Carey, plate tectonics . But he believed here in an Expanding Earth

The expanding Earth or growing Earth hypothesis argues that the position and relative movement of continents is at least partially due to the volume of Earth increasing. Conversely, geophysical global cooling was the hypothesis that various feat ...

.

* 1958, Henry William Menard

Henry William Menard (December 10, 1920 – February 9, 1986) was an American geologist.

Life and career

He earned a B.S. and M.S. from the California Institute of Technology in 1942 and 1947, having served in the South Pacific during World War ...

notes that most mid-ocean ridges are halfway between the two continental edges ( cited in ).

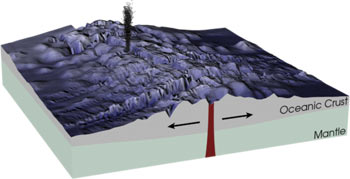

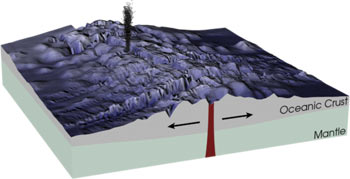

* Seafloor spreading

Seafloor spreading or Seafloor spread is a process that occurs at mid-ocean ridges, where new oceanic crust is formed through volcanic activity and then gradually moves away from the ridge.

History of study

Earlier theories by Alfred Wegener an ...

** December 1960, Harry H. Hess

Harry Hammond Hess (May 24, 1906 – August 25, 1969) was an American geologist and a United States Navy officer in World War II who is considered one of the "founding fathers" of the unifying theory of plate tectonics. He is best known for his th ...

(preprint and a report for the Navy): Sonar and seafloor spreading (personal communication formally published in 1962 (Puzzle pieces: his World War II seafloor profiles, , and the Great Global Rift). , , ,

** 1961, Robert S. Dietz

Robert Sinclair Dietz (September 14, 1914 – May 19, 1995) was a scientist with the US Coast and Geodetic Survey. Dietz, born in Westfield, New Jersey, was a marine geologist, geophysicist and oceanographer who conducted pioneering research along ...

.

* , the Permian tillite

image:Geschiebemergel.JPG, Closeup of glacial till. Note that the larger grains (pebbles and gravel) in the till are completely surrounded by the matrix of finer material (silt and sand), and this characteristic, known as ''matrix support'', is d ...

at Squantum, Massachusetts, was reclassified as turbidite

A turbidite is the geologic deposit of a turbidity current, which is a type of amalgamation of fluidal and sediment gravity flow responsible for distributing vast amounts of clastic sediment into the deep ocean.

Sequencing

Turbidites were ...

. It was used as argument by anti-drifters.

* P. M. S. Blakett (1960), Blakett's former lecturer S. K. Runcorn

(Stanley) Keith Runcorn (19 November 1922 – 5 December 1995) was a British physicist whose paleomagnetic reconstruction of the relative motions of Europe and America revived the theory of continental drift and was a major contribution to plat ...

(1962), Runcorn's former student E. Irving: Paleomagnetism.

** References: , , , , , ,

* 1962, S.K. Runcorn applies the Rayleigh's theory of convection: convection occurs if viscosity under the crust is less than 1026-1027 CGS units.

* 1962, Subduction

Subduction is a geological process in which the oceanic lithosphere is recycled into the Earth's mantle at convergent boundaries. Where the oceanic lithosphere of a tectonic plate converges with the less dense lithosphere of a second plate, the ...

in the Aleutian Islands

The Aleutian Islands (; ; ale, Unangam Tanangin,”Land of the Aleuts", possibly from Chukchi language, Chukchi ''aliat'', "island"), also called the Aleut Islands or Aleutic Islands and known before 1867 as the Catherine Archipelago, are a cha ...

, Robert R. Coats

Robert Roy Coats (1910–1995) was an American geologist known for his studies of the Aleutian Islands and his exhaustive report of Elko County, Nevada. He was born in Toronto, Canada, and grew up in Marshalltown, Iowa and Seattle, Washington. He ...

(USGS).

*

** The uncertainty of the distance between Europe and North America is too great to confirm the continental drift hypothesis. It states wrongly that the lock-and-key form of South America and Africa is less good if the continental shelf is taken into account. Note: the truth is that neither A. Wegener nor C. Schuchert used the east coastline of South America and west coastline of Africa, really; these coastlines don't fit .

Plate tectonics

* Publication of theVine–Matthews–Morley hypothesis

The Vine–Matthews–Morley hypothesis, also known as the Morley–Vine–Matthews hypothesis, was the first key scientific test of the seafloor spreading theory of continental drift and plate tectonics. Its key impact was that it allowed the r ...

. ,

** Frederick Vine

Frederick John Vine FRS (born 17 June 1939) is an English marine geologist and geophysicist. He made key contributions to the theory of plate tectonics, helping to show that the seafloor spreads from mid-ocean ridges with a symmetrical pattern ...

is working under Drummond Matthews

Drummond Hoyle Matthews FRS (5 February 1931 – 20 July 1997), known as "Drum", was a British marine geologist and geophysicist and a key contributor to the theory of plate tectonics. His work, along with that of fellow Briton Fred Vine an ...

, University of Cambridge

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

.

** Lawrence W. Morley's independent paper was not accepted.

* John Tuzo Wilson

John Tuzo Wilson (October 24, 1908 – April 15, 1993) was a Canadian geophysicist and geologist who achieved worldwide acclaim for his contributions to the theory of plate tectonics.

''Plate tectonics'' is the scientific theory that the rigi ...

, a former fixist/contractionist up to around 1959.

** J. T. Wilson spends much of 1965 in Cambridge and Hess joined him in the second half. Wilson develops the transform fault concept. , , , ,

** Wilson cycle

The Wilson Cycle is a model that describes the opening and closing of ocean basins and the subduction and divergence of tectonic plates during the assembly and disassembly of supercontinents. A classic example of the Wilson Cycle is the opening an ...

, .

** Frederick Vine, applies the transform fault

A transform fault or transform boundary, is a fault along a plate boundary where the motion is predominantly horizontal. It ends abruptly where it connects to another plate boundary, either another transform, a spreading ridge, or a subductio ...

concept, the Vine–Matthews–Morley hypothesis and the seafloor spreading concept on the Juan de Fuca Ridge

The Juan de Fuca Ridge is a mid-ocean spreading center and divergent plate boundary located off the coast of the Pacific Northwest region of North America. The ridge separates the Pacific Plate to the west and the Juan de Fuca Plate to the east ...

. He does not get a constant spreading rate as the Jaramillo reversal (Geomagnetic reversal

A geomagnetic reversal is a change in a planet's magnetic field such that the positions of magnetic north and magnetic south are interchanged (not to be confused with geographic north and geographic south). The Earth's field has alternated ...

) is unknown.

* , , .

* Wells, finds on growth rings of Devonian corals the maximum Earth expansion during this time to be less than 0.6 mm/year , . Heezen, abandons the expanding Earth theory as it requires a radial expansion of 4–8 mm/year for the Atlantic Ocean alone .

* 1966, East South America and West Africa, rocks and their ages match where they were joint: South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring countri ...

/ Santa de la Ventana, Argentina

Argentina (), officially the Argentine Republic ( es, link=no, República Argentina), is a country in the southern half of South America. Argentina covers an area of , making it the second-largest country in South America after Brazil, th ...

; Ghana

Ghana (; tw, Gaana, ee, Gana), officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country in West Africa. It abuts the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean to the south, sharing borders with Ivory Coast in the west, Burkina Faso in the north, and To ...

/ São Luís do Maranhão

SAO or Sao may refer to:

Places

* Sao civilisation, in Middle Africa from 6th century BC to 16th century AD

* Sao, a town in Boussé Department, Burkina Faso

* Saco Transportation Center (station code SAO), a train station in Saco, Maine, U.S. ...

, Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

.

** Nowadays, the fit between Africa and South America is based on paleomagnetism, slightly different from the older "Bullard's Fit" (based on least-square fitting of 500 fathom (c. 900 m) contours across the Atlantic). ,

* Closure:

** November 1965, Geological Society of America, Brent Dalrymple (Brent Dalrymple

G. Brent Dalrymple (born May 9, 1937) is an American geologist, author of ''The Age of the Earth'' and ''Ancient Earth, Ancient Skies'', and National Medal of Science winner.

He was born in Alhambra, California. After receiving a Ph.D. from Unive ...

, Richard Doell

Richard Doell (1923 – March 6, 2008) was a distinguished American scientist known for developing the time scale for geomagnetic reversals with Allan V. Cox and Brent Dalrymple. This work was a major step in the development of plate tectonics. Do ...

and Allan V. Cox

Allan Verne Cox (December 17, 1926 – January 27, 1987) was an American geophysicist. His work on dating geomagnetic reversals, with Richard Doell and Brent Dalrymple, made a major contribution to the theory of plate tectonics. Allan Cox won ...

– USGS) brought to Frederik Vine attention that there is the Jaramillo "reversal" (publ. mid-1966 !!!). ,

** February 1966, Vine visits the Lamont group (Walt Pitman and Neil Opdyke) and tells them that their 'discovered' Emperor reversal was already named as Jaramillo reversal. And shows the reversal on the Walt Pitman's graphik (cm/ vertical), surprising Pitman, Opdyke and even himself , . Many anti-drifters changed their mind after the publication of these magnetometer readings of sediment core (Eltanin-19), geomagnetic reversals .

** The Vine–Matthews–Morley hypothesis is the first scientific test to confirm the seafloor spreading concept. Earth Sciences paradigm shift, from fix continents to plate tectonics :

*** Magnetometer readings of sediment cores, geomagnetic reversals: ratio of cm (vertical).

*** Magnetic profiles of seafloor, geomagnetic reversals: ratio of km (horizontal).

*** Radiometric analysis of lava flows, geomagnetic reversals: ratio of Ma (time).

* Conference in New York in November 1966, sponsored by NASA ( cited in ).

** Maurice Ewing

William Maurice "Doc" Ewing (May 12, 1906 – May 4, 1974) was an American geophysicist and oceanographer.

Ewing has been described as a pioneering geophysicist who worked on the research of seismic reflection and refraction in ocean basin ...

to Edward Bullard

Sir Edward Crisp Bullard FRS (21 September 1907 – 3 April 1980) was a British geophysicist who is considered, along with Maurice Ewing, to have founded the discipline of marine geophysics. He developed the theory of the geodynamo, pioneered ...

: "You don't believe all this rubbish, do you, Teddy?"

* Even Maurice Ewing (Lamont–Doherty Earth Observatory

The Lamont–Doherty Earth Observatory (LDEO) is the scientific research center of the Columbia Climate School, and a unit of The Earth Institute at Columbia University. It focuses on climate and earth sciences and is located on a 189-acre (64 h ...

) came to accept seafloor spreading by April 1967 and cited (along with his brother John Ewing) the case for Vine-Matthews-Morley Hypothesis as "strong support for the hypothesis of spreading.

**

* Around 1967, Marshall Kay

Marshall Kay (November 10, 1904 – September 4, 1975) was a geologist and professor at Columbia University. He is best known for his studies of the Ordovician of New York, Newfoundland, and Nevada, but his studies were global and he published wid ...

becomes a drifter.

* In 1967, W. Jason Morgan

William Jason Morgan (born October 10, 1935) is an American geophysicist who has made seminal contributions to the theory of plate tectonics and geodynamics. He retired as the Knox Taylor Professor emeritus of geology and professor of geoscienc ...

proposed that the Earth's surface consists of 12 rigid plates that move relative to each other . Two months later, in 1968, Xavier Le Pichon

Xavier Le Pichon (born 18 June 1937 in Qui Nhơn, French protectorate of Annam (after South Vietnam and today Vietnam) is a French geophysicist. Among many other contributions, he is known for his comprehensive model of plate tectonics (1968), h ...

published a complete model based on 6 major plates with their relative motions (, received 2 January 1968). The Englishmen Dan McKenzie and Robert Parker published the quantitative principles for plate tectonics

Plate tectonics (from the la, label=Late Latin, tectonicus, from the grc, τεκτονικός, lit=pertaining to building) is the generally accepted scientific theory that considers the Earth's lithosphere to comprise a number of large ...

(Euler's rotation theorem

In geometry, Euler's rotation theorem states that, in three-dimensional space, any displacement of a rigid body such that a point on the rigid body remains fixed, is equivalent to a single rotation about some axis that runs through the fixed p ...

: Individual aseismic areas move as rigid plates on the surface of a sphere, quote: "a block on a sphere can be moved to any other conceivable orientation by a single rotation about a properly chosen axis.") .

** Note I: although (received 30 August 1967, revised 30 November 1967 and published 15 March 1968) was published later than (published 30 December 1967), priority belongs to Morgan. It is based on a presentation at the American Geophysical Union

The American Geophysical Union (AGU) is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization of Earth, atmospheric, ocean, hydrologic, space, and planetary scientists and enthusiasts that according to their website includes 130,000 people (not members). AGU's act ...

's 1967 meeting (title: ''Rises, Trenches, Great Faults, and Crustal Blocks'').

** Note II: W. Jason Morgan shared with Fred Vine an office in the Princeton University

Princeton University is a private university, private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth, New Jersey, Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the List of Colonial Colleges, fourth-oldest ins ...

for two years, and a scientific paper from H. W. Menard drifted his attention to plate tectonics. It was probably the long faults on (cited in ) and the Euler's rotation theorem that gave him the idea.

* End of the continental drift controversy in the USA: ''North Atlantic – Geology and Continental Drift, a Symposium (1969)''; American Association of Petroleum Geologists

The American Association of Petroleum Geologists (AAPG) is one of the world's largest professional geological societies with more than 40,000 members across 129 countries as of 2021. The AAPG works to "advance the science of geology, especially as ...

(AAPG) ( cited in ).

Geodynamics

Mantle plume

A mantle plume is a proposed mechanism of convection within the Earth's mantle, hypothesized to explain anomalous volcanism. Because the plume head partially melts on reaching shallow depths, a plume is often invoked as the cause of volcanic hot ...

controversy (, ): The relationship between subducted seafloor

The seabed (also known as the seafloor, sea floor, ocean floor, and ocean bottom) is the bottom of the ocean. All floors of the ocean are known as 'seabeds'.

The structure of the seabed of the global ocean is governed by plate tectonics. Most of ...

, flood basalt

A flood basalt (or plateau basalt) is the result of a giant volcanic eruption or series of eruptions that covers large stretches of land or the ocean floor with basalt lava. Many flood basalts have been attributed to the onset of a hotspot reach ...

s and continental rifting is uncovered. , , , , ,

*** Plume tectonics

Plume tectonics is a geoscientific theory that finds its roots in the mantle doming concept which was especially popular during the 1930s and initially did not accept major plate movements and continental drifting. It has survived from the 1970s ...

: , ,

** Slab pull force

Slab pull is a geophysical mechanism whereby the cooling and subsequent densifying of a subducting tectonic plate produces a downward force along the rest of the plate. In 1975 Forsyth and Uyeda used the inverse theory method to show that, of the m ...

, Slab suction force (Back-arc basin

A back-arc basin is a type of geologic basin, found at some convergent plate boundaries. Presently all back-arc basins are submarine features associated with island arcs and subduction zones, with many found in the western Pacific Ocean. Most of ...

) and Ridge push force

Ridge push (also known as gravitational sliding) or sliding plate force is a proposed driving force for plate motion in plate tectonics that occurs at mid-ocean ridges as the result of the rigid lithosphere sliding down the hot, raised asthenosp ...

:

*** Back-arc basin , ,

*** Similar to a landslide, seafloor sinks and subducts , , , ,

** Wilson cycle

The Wilson Cycle is a model that describes the opening and closing of ocean basins and the subduction and divergence of tectonic plates during the assembly and disassembly of supercontinents. A classic example of the Wilson Cycle is the opening an ...

: slab pull/ subduction

Subduction is a geological process in which the oceanic lithosphere is recycled into the Earth's mantle at convergent boundaries. Where the oceanic lithosphere of a tectonic plate converges with the less dense lithosphere of a second plate, the ...

opens a space on western South America and the sliding seafloor away from the Mid-Atlantic Ridge

The Mid-Atlantic Ridge is a mid-ocean ridge (a divergent or constructive plate boundary) located along the floor of the Atlantic Ocean, and part of the longest mountain range in the world. In the North Atlantic, the ridge separates the North Ame ...

on eastern South America occupies the new available space.

** Overview: viscous resistance, slab thickness, slab bending, trench migration and seismic coupling, slab width, slab edges and mantle return flow:

***

***

***

* Current plate motions. , ,

* Pacific Plate

The Pacific Plate is an oceanic tectonic plate that lies beneath the Pacific Ocean. At , it is the largest tectonic plate.

The plate first came into existence 190 million years ago, at the triple junction between the Farallon, Phoenix, and Iza ...

, lower mantle

A mantle is a piece of clothing, a type of cloak. Several other meanings are derived from that.

Mantle may refer to:

*Mantle (clothing), a cloak-like garment worn mainly by women as fashionable outerwear

**Mantle (vesture), an Eastern Orthodox ve ...

has a greater viscosity

* Tibetan Plateau

The Tibetan Plateau (, also known as the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau or the Qing–Zang Plateau () or as the Himalayan Plateau in India, is a vast elevated plateau located at the intersection of Central, South and East Asia covering most of the Ti ...

, collision generates heat ,

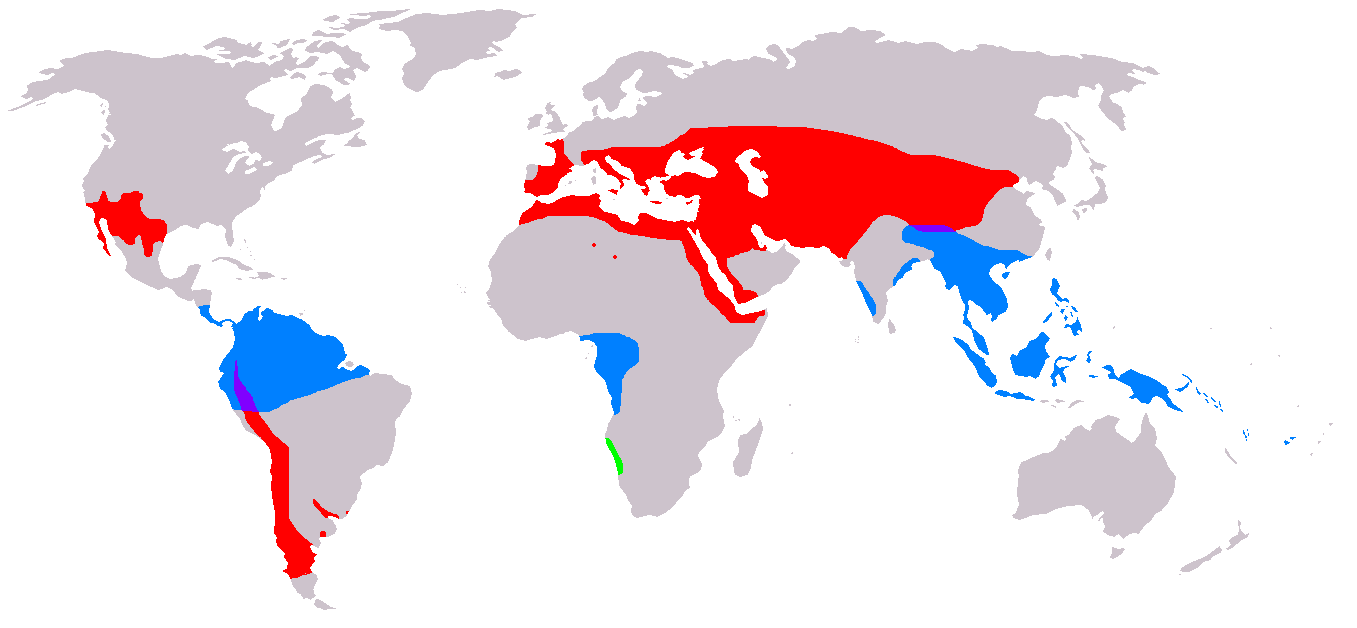

* Paleogeography

Palaeogeography (or paleogeography) is the study of historical geography, generally physical landscapes. Palaeogeography can also include the study of human or cultural environments. When the focus is specifically on landforms, the term pale ...

( and ):

** Order Cycadales

Cycads are seed plants that typically have a stout and woody (ligneous) trunk with a crown of large, hard, stiff, evergreen and (usually) pinnate leaves. The species are dioecious, that is, individual plants of a species are either male or ...

, genus ''Bowenia

The genus ''Bowenia'' includes two living and two fossil species of cycads in the family Stangeriaceae, sometimes placed in their own family Boweniaceae. They are entirely restricted to Australia. The two living species occur in Queensland. '' ...

''

** Family Araucariaceae

Araucariaceae – also known as araucarians – is an extremely ancient family of coniferous trees. The family achieved its maximum diversity during the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods and the early Cenozoic, when it was distributed almost worldw ...

found in Norfolk Island

Norfolk Island (, ; Norfuk: ''Norf'k Ailen'') is an external territory of Australia located in the Pacific Ocean between New Zealand and New Caledonia, directly east of Australia's Evans Head and about from Lord Howe Island. Together with ...

, Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a Sovereign state, sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous List of islands of Australia, sma ...

, Vanuatu

Vanuatu ( or ; ), officially the Republic of Vanuatu (french: link=no, République de Vanuatu; bi, Ripablik blong Vanuatu), is an island country located in the South Pacific Ocean. The archipelago, which is of volcanic origin, is east of no ...

, New Caledonia

)

, anthem = ""

, image_map = New Caledonia on the globe (small islands magnified) (Polynesia centered).svg

, map_alt = Location of New Caledonia

, map_caption = Location of New Caledonia

, mapsize = 290px

, subdivision_type = Sovereign st ...

, Papua New Guinea

Papua New Guinea (abbreviated PNG; , ; tpi, Papua Niugini; ho, Papua Niu Gini), officially the Independent State of Papua New Guinea ( tpi, Independen Stet bilong Papua Niugini; ho, Independen Stet bilong Papua Niu Gini), is a country i ...

, Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania between the Indian and Pacific oceans. It consists of over 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, Java, Sulawesi, and parts of Borneo and New Guine ...

, Malaysia

Malaysia ( ; ) is a country in Southeast Asia. The federation, federal constitutional monarchy consists of States and federal territories of Malaysia, thirteen states and three federal territories, separated by the South China Sea into two r ...

, Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

, New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu

Hiri Motu, also known as Police Motu, Pidgin Motu, or just Hiri, is a language of Papua New Guinea, which is spoken in surrounding areas of Port Moresby (Capital of Papua New Guinea).

It is a simplified version of ...

, Argentina

Argentina (), officially the Argentine Republic ( es, link=no, República Argentina), is a country in the southern half of South America. Argentina covers an area of , making it the second-largest country in South America after Brazil, th ...

, Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the east a ...

, and southern Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

. Coal fossils found on the British Isles

The British Isles are a group of islands in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-western coast of continental Europe, consisting of the islands of Great Britain, Ireland, the Isle of Man, the Inner and Outer Hebrides, the Northern Isles, ...

.

** ''Magnolia

''Magnolia'' is a large genus of about 210 to 340The number of species in the genus ''Magnolia'' depends on the taxonomic view that one takes up. Recent molecular and morphological research shows that former genera ''Talauma'', ''Dugandiodendro ...

'', subgenus ''Magnolia'':

*** Section ''Magnolia'', found in the Neotropical realm

The Neotropical realm is one of the eight biogeographic realms constituting Earth's land surface. Physically, it includes the tropical terrestrial ecoregions of the Americas and the entire South American temperate zone.

Definition

In bioge ...

*** Section ''Gwillimia'', found in Asia including Borneo

Borneo (; id, Kalimantan) is the third-largest island in the world and the largest in Asia. At the geographic centre of Maritime Southeast Asia, in relation to major Indonesian islands, it is located north of Java, west of Sulawesi, and eas ...

*** Section ''Blumiana'', found in Asia, including Sumatra

Sumatra is one of the Sunda Islands of western Indonesia. It is the largest island that is fully within Indonesian territory, as well as the sixth-largest island in the world at 473,481 km2 (182,812 mi.2), not including adjacent i ...

and Borneo

*** Section ''Talauma'', found in the Neotropical realm

*** Section ''Manglietia'', found in Asia

*** Section ''Kmeria'', found in Asia

*** Section ''Rhytidospermum'', found in Asia and ''Magnolia tripetala

''Magnolia tripetala'', commonly called umbrella magnolia or simply umbrella-tree, is a deciduous tree native to the eastern United States in the Appalachian Mountains, the Ozarks, and the Ouachita Mountains. The name "umbrella tree" derives fr ...

'' (L.) L. in Southeast USA

*** Section ''Auriculata'', ''Magnolia fraseri

''Magnolia fraseri'', commonly known as Fraser magnolia, mountain magnolia, earleaf cucumbertree, or mountain-oread, is a species of magnolia native to the south-eastern United States in the southern Appalachian Mountains and adjacent Atlantic an ...

'' Walt. found in Southeast USA

*** Section ''Macrophylla'', '' Magnolia macrophylla'' Michx. found in Southeast USA

** ''Magnolia'', subgenus ''Yulania'':

*** Section ''Yulania'', found in Asia and ''Magnolia acuminata

''Magnolia acuminata'', commonly called the cucumber tree (often spelled as a single word "cucumbertree"), cucumber magnolia or blue magnolia, is one of the largest magnolias, and one of the cold-hardiest. It is a large forest tree of the Easte ...

'' (L.) L. found in East USA

*** Section ''Michelia'', found in Asia including the Indomalayan realm

The Indomalayan realm is one of the eight biogeographic realms. It extends across most of South and Southeast Asia and into the southern parts of East Asia.

Also called the Oriental realm by biogeographers, Indomalaya spreads all over the Indi ...

** Note: a bee

Bees are winged insects closely related to wasps and ants, known for their roles in pollination and, in the case of the best-known bee species, the western honey bee, for producing honey. Bees are a monophyly, monophyletic lineage within the ...

fossil of the genus '' Melittosphex'', is considered ''"an extinct lineage of pollen-collecting Apoidea sister

A sister is a woman or a girl who shares one or more parents with another individual; a female sibling. The male counterpart is a brother. Although the term typically refers to a familial relationship, it is sometimes used endearingly to refer to ...

to the modern bees"'', and dates from the early Cretaceous

The Early Cretaceous ( geochronological name) or the Lower Cretaceous (chronostratigraphic name), is the earlier or lower of the two major divisions of the Cretaceous. It is usually considered to stretch from 145 Ma to 100.5 Ma.

Geology

Pro ...

(c. 100 Ma). Insect-pollinated flowering plant

Flowering plants are plants that bear flowers and fruits, and form the clade Angiospermae (), commonly called angiosperms. The term "angiosperm" is derived from the Greek words ('container, vessel') and ('seed'), and refers to those plants th ...

s need bees (unranked taxon Anthophila

Bees are winged insects closely related to wasps and ants, known for their roles in pollination and, in the case of the best-known bee species, the western honey bee, for producing honey. Bees are a monophyletic lineage within the superfami ...

, of the superfamily Apoidea

The superfamily (zoology), superfamily Apoidea is a major group within the Hymenoptera, which includes two traditionally recognized lineages, the "sphecidae, sphecoid" wasps, and the bees. Molecular phylogeny demonstrates that the bees arose from ...

). Beetle

Beetles are insects that form the order Coleoptera (), in the superorder Endopterygota. Their front pair of wings are hardened into wing-cases, elytra, distinguishing them from most other insects. The Coleoptera, with about 400,000 describ ...

s may have originated during the Lower Permian

The Permian ( ) is a geologic period and stratigraphic system which spans 47 million years from the end of the Carboniferous Period million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Triassic Period 251.9 Mya. It is the last period of the Paleoz ...

, up to 299 Ma. Flies

Flies are insects of the order Diptera, the name being derived from the Greek δι- ''di-'' "two", and πτερόν ''pteron'' "wing". Insects of this order use only a single pair of wings to fly, the hindwings having evolved into advanced ...

evolved c. 250 Ma, moth

Moths are a paraphyletic group of insects that includes all members of the order Lepidoptera that are not butterflies, with moths making up the vast majority of the order. There are thought to be approximately 160,000 species of moth, many of w ...

s and wasp

A wasp is any insect of the narrow-waisted suborder Apocrita of the order Hymenoptera which is neither a bee nor an ant; this excludes the broad-waisted sawflies (Symphyta), which look somewhat like wasps, but are in a separate suborder. Th ...

s evolved c. 150 Ma.

*

** Total estimated radiogenic heat

A radiogenic nuclide is a nuclide that is produced by a process of radioactive decay. It may itself be radioactive (a radionuclide) or stable (a stable nuclide).

Radiogenic nuclides (more commonly referred to as radiogenic isotopes) form some of ...

release (from neutrino research): 19 Terawatts

** Total directly observed heat release through Earth's surface: 31 Terawatts

* Seismic anisotropy

Seismic anisotropy is a term used in seismology to describe the directional dependence of the velocity of seismic waves in a medium (rock) within the Earth.

Description

A material is said to be anisotropic if the value of one or more of its prope ...

, ,

* Plate reconstruction

:''This article describes techniques; for a history of the movement of tectonic plates, see Geological history of Earth.''

Plate reconstruction is the process of reconstructing the positions of tectonic plates relative to each other (relative motio ...

: Torsvik, Trond Helge and Gaina, Carmen, Center for Geodynamics at NGU (Geological Survey of Norway

Geological Survey of Norway ( no, Norges geologiske undersøkelse), abbreviation: ''NGU'', is a Norwegian government agency responsible for geologic mapping and research. The agency is located in Trondheim with an office in Tromsø, with about 2 ...

), PGP (Physics of Geological Processes, University of Oslo, Norway); Müller, R. Dietmar, EarthByte Group, University of Sydney

The University of Sydney (USYD), also known as Sydney University, or informally Sydney Uni, is a public research university located in Sydney, Australia. Founded in 1850, it is the oldest university in Australia and is one of the country's si ...

; Scotese, C.R., Ziegler, A.M. and Van der Voo, R., University of Michigan

, mottoeng = "Arts, Knowledge, Truth"

, former_names = Catholepistemiad, or University of Michigania (1817–1821)

, budget = $10.3 billion (2021)

, endowment = $17 billion (2021)As o ...

, University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, U of C, or UChi) is a private research university in Chicago, Illinois. Its main campus is located in Chicago's Hyde Park neighborhood. The University of Chicago is consistently ranked among the b ...

and University of Texas

The University of Texas at Austin (UT Austin, UT, or Texas) is a public research university in Austin, Texas. It was founded in 1883 and is the oldest institution in the University of Texas System. With 40,916 undergraduate students, 11,075 ...

, Arlington; Ziegler, P.A. and Stampfli, Gérard, University of Basel

The University of Basel (Latin: ''Universitas Basiliensis'', German: ''Universität Basel'') is a university in Basel, Switzerland. Founded on 4 April 1460, it is Switzerland's oldest university and among the world's oldest surviving universit ...

and University of Lausanne

The University of Lausanne (UNIL; french: links=no, Université de Lausanne) in Lausanne, Switzerland was founded in 1537 as a school of Protestant theology, before being made a university in 1890. The university is the second oldest in Switzer ...

.

** , ,

*Global plate reconstructions

with velocity fields from 150 Ma to present in 10 Ma increments.

Overview

Many concepts had to be changed: *Uniformitarianism

Uniformitarianism, also known as the Doctrine of Uniformity or the Uniformitarian Principle, is the assumption that the same natural laws and processes that operate in our present-day scientific observations have always operated in the universe in ...

instead of catastrophism

In geology, catastrophism theorises that the Earth has largely been shaped by sudden, short-lived, violent events, possibly worldwide in scope.

This contrasts with uniformitarianism (sometimes called gradualism), according to which slow increment ...

.

* Empirical science instead of creationism

Creationism is the religious belief that nature, and aspects such as the universe, Earth, life, and humans, originated with supernatural acts of divine creation. Gunn 2004, p. 9, "The ''Concise Oxford Dictionary'' says that creationism is 't ...

.

* Plutonism

Plutonism is the geologic theory that the igneous rocks forming the Earth originated from intrusive magmatic activity, with a continuing gradual process of weathering and erosion wearing away rocks, which were then deposited on the sea bed, re- ...

instead of neptunism

Neptunism is a superseded scientific theory of geology proposed by Abraham Gottlob Werner (1749–1817) in the late 18th century, proposing that rocks formed from the crystallisation of minerals in the early Earth's oceans.

The theory took its na ...

, but hydrothermal secondary mineralization occurs.

* Seafloor of sima

Sima or SIMA may refer to:

People

* Sima (Chinese surname)

* Sima (given name), a Persian feminine name in use in Iran and Turkey

* Sima (surname)

Places

* Sima, Comoros, on the island of Anjouan, near Madagascar

* Sima de los Huesos, a cav ...

instead of sial

In geology, the term sial refers to the composition of the upper layer of Earth's crust, namely rocks rich in aluminium silicate minerals. It is sometimes equated with the continental crust because it is absent in the wide oceanic basins, but ...

.

* Baron Kelvin got the age of the Earth too short.

* The concept of Earth crust and mantle

A mantle is a piece of clothing, a type of cloak. Several other meanings are derived from that.

Mantle may refer to:

*Mantle (clothing), a cloak-like garment worn mainly by women as fashionable outerwear

**Mantle (vesture), an Eastern Orthodox ve ...

.

* Airy-Heiskanen isostasy

Isostasy (Greek ''ísos'' "equal", ''stásis'' "standstill") or isostatic equilibrium is the state of gravitational equilibrium between Earth's crust (or lithosphere) and mantle such that the crust "floats" at an elevation that depends on its ...

model instead of the Pratt-Hayford model.

* Thrust fault

A thrust fault is a break in the Earth's crust, across which older rocks are pushed above younger rocks.

Thrust geometry and nomenclature

Reverse faults

A thrust fault is a type of reverse fault that has a dip of 45 degrees or less.

If ...

s had to be accepted.

* The expanding Earth

The expanding Earth or growing Earth hypothesis argues that the position and relative movement of continents is at least partially due to the volume of Earth increasing. Conversely, geophysical global cooling was the hypothesis that various feat ...

and the contracting Earth

Before the concept of plate tectonics, global cooling was a geophysical theory by James Dwight Dana, also referred to as the contracting earth theory. It suggested that the Earth had been in a molten state, and features such as mountains formed as ...

concept had to be given up.

The shifting and evolution of knowledge and concepts, were from:

* Eduard Suess

Eduard Suess (; 20 August 1831 - 26 April 1914) was an Austrian geologist and an expert on the geography of the Alps. He is responsible for hypothesising two major former geographical features, the supercontinent Gondwana (proposed in 1861) and t ...

(alpine geology: theory of thrusting as a modification of the geosyncline

A geosyncline (originally called a geosynclinal) is an obsolete geological concept to explain orogens, which was developed in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, before the theory of plate tectonics was envisaged. Şengör (1982), p. 11 A geo ...

hypothesis), ;

* then to Alfred Wegener

Alfred Lothar Wegener (; ; 1 November 1880 – November 1930) was a German climatologist, geologist, geophysicist, meteorologist, and polar researcher.

During his lifetime he was primarily known for his achievements in meteorology and a ...

(continental drift

Continental drift is the hypothesis that the Earth's continents have moved over geologic time relative to each other, thus appearing to have "drifted" across the ocean bed. The idea of continental drift has been subsumed into the science of pla ...

), , ;

* then to Arthur Holmes

Arthur Holmes (14 January 1890 – 20 September 1965) was an English geologist who made two major contributions to the understanding of geology. He pioneered the use of radiometric dating of minerals, and was the first earth scientist to grasp ...

(a model with convection), ;

* then to Felix Andries Vening Meinesz

Felix Andries Vening Meinesz (30 July 1887 – 10 August 1966) was a Dutch geophysicist and geodesist. He is known for his invention of a precise method for measuring gravity (gravimetry). Thanks to his invention, it became possible to measure g ...

( gravity anomalies along the oceanic trench

Oceanic trenches are prominent long, narrow topographic depressions of the ocean floor. They are typically wide and below the level of the surrounding oceanic floor, but can be thousands of kilometers in length. There are about of oceanic tren ...

es implied that the crust was moving) and A. Rittmann (subduction

Subduction is a geological process in which the oceanic lithosphere is recycled into the Earth's mantle at convergent boundaries. Where the oceanic lithosphere of a tectonic plate converges with the less dense lithosphere of a second plate, the ...

), , ;

* then to Samuel Warren Carey

Samuel Warren Carey Order of Australia, AO (1 November 1911, in Campbelltown, New South Wales, Campbelltown – 20 March 2002, in Hobart) was an Australian geologist and a professor at the University of Tasmania. He was an early advocate of ...

(plate tectonics

Plate tectonics (from the la, label=Late Latin, tectonicus, from the grc, τεκτονικός, lit=pertaining to building) is the generally accepted scientific theory that considers the Earth's lithosphere to comprise a number of large ...

), ; Harry Hammond Hess

Harry Hammond Hess (May 24, 1906 – August 25, 1969) was an American geologist and a United States Navy officer in World War II who is considered one of the "founding fathers" of the unifying theory of plate tectonics. He is best known for his th ...

and Robert S. Dietz

Robert Sinclair Dietz (September 14, 1914 – May 19, 1995) was a scientist with the US Coast and Geodetic Survey. Dietz, born in Westfield, New Jersey, was a marine geologist, geophysicist and oceanographer who conducted pioneering research along ...

(seafloor spreading

Seafloor spreading or Seafloor spread is a process that occurs at mid-ocean ridges, where new oceanic crust is formed through volcanic activity and then gradually moves away from the ridge.

History of study

Earlier theories by Alfred Wegener an ...

), , ;

* then to John Tuzo Wilson

John Tuzo Wilson (October 24, 1908 – April 15, 1993) was a Canadian geophysicist and geologist who achieved worldwide acclaim for his contributions to the theory of plate tectonics.

''Plate tectonics'' is the scientific theory that the rigi ...

(seafloor spreading), , (transform faults

A transform fault or transform boundary, is a fault along a plate boundary where the motion is predominantly horizontal. It ends abruptly where it connects to another plate boundary, either another transform, a spreading ridge, or a subductio ...

), and (Wilson cycle

The Wilson Cycle is a model that describes the opening and closing of ocean basins and the subduction and divergence of tectonic plates during the assembly and disassembly of supercontinents. A classic example of the Wilson Cycle is the opening an ...

), ;

* then to the confirmation of the Vine–Matthews–Morley hypothesis

The Vine–Matthews–Morley hypothesis, also known as the Morley–Vine–Matthews hypothesis, was the first key scientific test of the seafloor spreading theory of continental drift and plate tectonics. Its key impact was that it allowed the r ...

, and paradigm shift, and ;

* then to Jason Morgan, Dan McKenzie and Robert Parker (quantification of plate tectonics), , ; its uncertainty was quantified by Theodore C. Chang;

* and then to computer simulation with slab pull

Slab pull is a geophysical mechanism whereby the cooling and subsequent densifying of a subducting tectonic plate produces a downward force along the rest of the plate. In 1975 Forsyth and Uyeda used the inverse theory method to show that, of the m ...

and "ridge-push

Ridge push (also known as gravitational sliding) or sliding plate force is a proposed driving force for plate motion in plate tectonics that occurs at mid-ocean ridges as the result of the rigid lithosphere sliding down the hot, raised asthenosp ...

" , , and with nice works published by the Scripps Institution of Oceanography

The Scripps Institution of Oceanography (sometimes referred to as SIO, Scripps Oceanography, or Scripps) in San Diego, California, US founded in 1903, is one of the oldest and largest centers for oceanography, ocean and Earth science research ...

, the EarthByte Group (R. Dietmar Müller) and the Center for Geodynamics (Trond Helge Torsvik and Carmen Gaina).

Actually, there were two main "schools of thought" that pushed

Actually, there were two main "schools of thought" that pushed plate tectonics

Plate tectonics (from the la, label=Late Latin, tectonicus, from the grc, τεκτονικός, lit=pertaining to building) is the generally accepted scientific theory that considers the Earth's lithosphere to comprise a number of large ...

forward:

* The "alternative concepts to e.g. Harold Jeffreys

Sir Harold Jeffreys, FRS (22 April 1891 – 18 March 1989) was a British mathematician, statistician, geophysicist, and astronomer. His book, ''Theory of Probability'', which was first published in 1939, played an important role in the revival ...

group", James Hutton

James Hutton (; 3 June O.S.172614 June 1726 New Style. – 26 March 1797) was a Scottish geologist, agriculturalist, chemical manufacturer, naturalist and physician. Often referred to as the father of modern geology, he played a key role i ...

, Eduard Suess

Eduard Suess (; 20 August 1831 - 26 April 1914) was an Austrian geologist and an expert on the geography of the Alps. He is responsible for hypothesising two major former geographical features, the supercontinent Gondwana (proposed in 1861) and t ...

, Alfred Wegener

Alfred Lothar Wegener (; ; 1 November 1880 – November 1930) was a German climatologist, geologist, geophysicist, meteorologist, and polar researcher.

During his lifetime he was primarily known for his achievements in meteorology and a ...

, Alexander du Toit

Alexander Logie du Toit FRS ( ; 14 March 1878 – 25 February 1948) was a geologist from South Africa and an early supporter of Alfred Wegener's theory of continental drift.

Early life and education

Du Toit was born in Newlands, Cape Town in ...

, Arthur Holmes

Arthur Holmes (14 January 1890 – 20 September 1965) was an English geologist who made two major contributions to the understanding of geology. He pioneered the use of radiometric dating of minerals, and was the first earth scientist to grasp ...

and Felix Andries Vening Meinesz

Felix Andries Vening Meinesz (30 July 1887 – 10 August 1966) was a Dutch geophysicist and geodesist. He is known for his invention of a precise method for measuring gravity (gravimetry). Thanks to his invention, it became possible to measure g ...

(together with J.H.F. Umbgrove, B.G. Escher and Ph.H. Kuenen). Holmes, Vening Meinesz and Umbgrove had some experience in Burma or Indonesia (Pacific Ring of Fire

The Ring of Fire (also known as the Pacific Ring of Fire, the Rim of Fire, the Girdle of Fire or the Circum-Pacific belt) is a region around much of the rim of the Pacific Ocean where many Types of volcanic eruptions, volcanic eruptions and ...

).

** The alpine geology "school of thought": , , , , and . With the theory of thrusting, nappe

In geology, a nappe or thrust sheet is a large sheetlike body of rock (geology), rock that has been moved more than or above a thrust fault from its original position. Nappes form in compressional tectonic settings like continental collision z ...

s, thrust fault

A thrust fault is a break in the Earth's crust, across which older rocks are pushed above younger rocks.

Thrust geometry and nomenclature

Reverse faults

A thrust fault is a type of reverse fault that has a dip of 45 degrees or less.

If ...

s and subduction

Subduction is a geological process in which the oceanic lithosphere is recycled into the Earth's mantle at convergent boundaries. Where the oceanic lithosphere of a tectonic plate converges with the less dense lithosphere of a second plate, the ...

s.

* The "Princeton University" group around H. H. Hess: Felix Andries Vening Meinesz, Harry Hammond Hess

Harry Hammond Hess (May 24, 1906 – August 25, 1969) was an American geologist and a United States Navy officer in World War II who is considered one of the "founding fathers" of the unifying theory of plate tectonics. He is best known for his th ...

, John Tuzo Wilson

John Tuzo Wilson (October 24, 1908 – April 15, 1993) was a Canadian geophysicist and geologist who achieved worldwide acclaim for his contributions to the theory of plate tectonics.

''Plate tectonics'' is the scientific theory that the rigi ...

, W. Jason Morgan

William Jason Morgan (born October 10, 1935) is an American geophysicist who has made seminal contributions to the theory of plate tectonics and geodynamics. He retired as the Knox Taylor Professor emeritus of geology and professor of geoscienc ...

and Frederick Vine

Frederick John Vine FRS (born 17 June 1939) is an English marine geologist and geophysicist. He made key contributions to the theory of plate tectonics, helping to show that the seafloor spreads from mid-ocean ridges with a symmetrical pattern ...

. Overview of plate tectonics in: .

** Vening Meinesz (together with J.H.F. Umbgrove, B.G. Escher and Ph.H. Kuenen) had more evidence that the established paradigm and the reality do not match. But as all geophysicist

Geophysics () is a subject of natural science concerned with the physical processes and physical properties of the Earth and its surrounding space environment, and the use of quantitative methods for their analysis. The term ''geophysics'' som ...

s he could not really believe in crust motions in such a large scale and he knew Wegener's Continental drift hypothesis fate too. accumulated even more evidence, but he prudently introduced them as geopoetry, quote: "Little of brilliant summary remains pertinent when confronted by the relatively small but crucial amount of information collected in the intervening years. Like Umbgrove, I shall consider this paper an essay in geopoetry."

* The IAV/ IAVEI board (i.e., B.G. Escher and A. Rittmann) probably never dumped the idea that the South Atlantic is under extension

Extension, extend or extended may refer to:

Mathematics

Logic or set theory

* Axiom of extensionality

* Extensible cardinal

* Extension (model theory)

* Extension (predicate logic), the set of tuples of values that satisfy the predicate

* E ...

.

* And the anti-drifters were in a way right as well. Although convection would mix up the mantle

A mantle is a piece of clothing, a type of cloak. Several other meanings are derived from that.

Mantle may refer to:

*Mantle (clothing), a cloak-like garment worn mainly by women as fashionable outerwear

**Mantle (vesture), an Eastern Orthodox ve ...

and make it homogeneous. The seafloor cycle with subduction and upwelling is something between conduction and convection, it allows for its inhomogeneity in a quasi-steady state. The mantle and the continents are in a way passive, the heat sink of the earth is the seafloor. So that the heat generated in the earth gets neutralised.

Wegener's continental drift hypotheses is a logical consequence of: the theory of thrusting (alpine geology), the isostasy, the continents forms resulting from the supercontinent Gondwana break up, the past and present-day life forms on both sides of the Gondwana continent margins, and the Permo-Carboniferous moraine deposits in South Gondwana.

Graphics

See also

*References

Notes

Cited books

* * P.M.S. Blackett, E.C. Bullard and S.K. Runcorn (ed). A Symposium on Continental Drift, held on 28 October 1965. pp. 323: ** ** ** * Expanding Earth from pp. 311–349. * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * ** * * ** * ** * * * * Wegener pp. 72–75. * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * ** * *Cited articles

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * Review of Allan Krill, ''Fixists vs. Mobilists in the Geology Contest of the Century, 1844–1969''. * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * Just an overview of the article in Petermanns Geographische Mitteilungen. * * * He gives reasons for the paleo connection of the Americas and Eurasia-Africa by naming paleontological similarities, parallelism of coastal forms and the recently researched submarine Atlantic mountain range as ideal seam of continental splits (p. 181). * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * * * {{Cite web , url=http://csmres.jmu.edu/geollab/Fichter/Wilson/Wilson.html , title=Wilson Cycle: and A Plate Tectonic Rock Cycle , publisher=Lynn S. Fichter Plate tectonics History of Earth science Geology timelines 20th century in science 21st century in science