Thomas Richardson (judge) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir Thomas Richardson (1569 – 4 February 1635) of Honingham in Norfolk,RICHARDSON, Thomas, 2nd Baron Cramond (1627-74), of Honingham, Norf. Published in The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1660-1690, ed. B.D. Henning, 198

Sir Thomas Richardson (1569 – 4 February 1635) of Honingham in Norfolk,RICHARDSON, Thomas, 2nd Baron Cramond (1627-74), of Honingham, Norf. Published in The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1660-1690, ed. B.D. Henning, 198

/ref> was an English judge and politician who sat in the House of Commons of England, House of Commons from 1621 to 1622. He was

History-The village & the people , Honingham Village website , Page 9

Retrieved 13 October 2016. He was subsequently

/ref> When Parliament met on 30 January 1621, he was chosen Speaker of the House of Commons. The excuses which he made before accepting this office appear to have been more than formal, for an eye-witness reports that he "wept downright". On 25 March 1621, he was

Richardson was advanced to the chief-justiceship of the king's bench on 24 October 1631, and served on the western circuit. He was not a

Richardson was advanced to the chief-justiceship of the king's bench on 24 October 1631, and served on the western circuit. He was not a

Richardson married twice:

*Firstly to Ursula Southwell (d.1624), the third daughter of John Southwell of Barham Hall in

Richardson married twice:

*Firstly to Ursula Southwell (d.1624), the third daughter of John Southwell of Barham Hall in

Sir Thomas Richardson (1569 – 4 February 1635) of Honingham in Norfolk,RICHARDSON, Thomas, 2nd Baron Cramond (1627-74), of Honingham, Norf. Published in The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1660-1690, ed. B.D. Henning, 198

Sir Thomas Richardson (1569 – 4 February 1635) of Honingham in Norfolk,RICHARDSON, Thomas, 2nd Baron Cramond (1627-74), of Honingham, Norf. Published in The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1660-1690, ed. B.D. Henning, 198/ref> was an English judge and politician who sat in the House of Commons of England, House of Commons from 1621 to 1622. He was

Speaker of the House of Commons Speaker of the House of Commons is a political leadership position found in countries that have a House of Commons, where the membership of the body elects a speaker to lead its proceedings.

Systems that have such a position include:

* Speaker of ...

for this parliament. He was later Chief Justice of the Common Pleas

The chief justice of the Common Pleas was the head of the Court of Common Pleas, also known as the Common Bench or Common Place, which was the second-highest common law court in the English legal system until 1875, when it, along with the other ...

and Chief Justice of the King's Bench.

Background and early life

Richardson was born at Hardwick, Depwade Hundred,Norfolk

Norfolk () is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in East Anglia in England. It borders Lincolnshire to the north-west, Cambridgeshire to the west and south-west, and Suffolk to the south. Its northern and eastern boundaries are the No ...

, and was baptised there on 3 July 1569, the son of William Richardson whose family were said to be descended from the younger son of a Norman family, John, who moved to county Durham in about 1100. Other branches of the family included the Richardsons of the Briary in county Durham, and the Richardsons of Glanbrydan Park and Pantygwydr, Wales. However, the History of Parliament

The History of Parliament is a project to write a complete history of the United Kingdom Parliament and its predecessors, the Parliament of Great Britain and the Parliament of England. The history will principally consist of a prosopography, in w ...

biography of his grandson states that he was "of Norfolk peasant stock". The coat of arms he used (''Argent, on a chief sable three lion's heads erased of the first'') was certainly that of the ancient gentry family of Richardson, of many branches.

He was educated at Norwich School

Norwich School (formally King Edward VI Grammar School, Norwich) is a selective English independent day school in the close of Norwich Cathedral, Norwich. Among the oldest schools in the United Kingdom, it has a traceable history to 1096 as a ...

, and matriculated at Christ's College, Cambridge

Christ's College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. The college includes the Master, the Fellows of the College, and about 450 undergraduate and 170 graduate students. The college was founded by William Byngham in 1437 as ...

in June 1584.

On 5 March 1587, he was admitted a student at Lincoln's Inn

The Honourable Society of Lincoln's Inn is one of the four Inns of Court in London to which barristers of England and Wales belong and where they are called to the Bar. (The other three are Middle Temple, Inner Temple and Gray's Inn.) Lincoln ...

, where he was called to the bar on 28 January 1595. In about 1600 he purchased the estate of Honingham in Norfolk, which he made his seat.

In 1605 he was deputy steward to the dean and chapter of Norwich

Norwich () is a cathedral city and district of Norfolk, England, of which it is the county town. Norwich is by the River Wensum, about north-east of London, north of Ipswich and east of Peterborough. As the seat of the See of Norwich, with ...

, around which time he built Honingham Hall

Honingham Hall was a large country house at Honingham in Norfolk.

History

The house was commissioned by Sir Thomas Richardson, Chief Justice of the King’s Bench in 1605. After passing down the Richardson family it was bought by Richard Bayli ...

.Retrieved 13 October 2016.

recorder

Recorder or The Recorder may refer to:

Newspapers

* ''Indianapolis Recorder'', a weekly newspaper

* ''The Recorder'' (Massachusetts newspaper), a daily newspaper published in Greenfield, Massachusetts, US

* ''The Recorder'' (Port Pirie), a news ...

of Bury St. Edmunds

Bury St Edmunds (), commonly referred to locally as Bury, is a historic market, cathedral town and civil parish in Suffolk, England.OS Explorer map 211: Bury St.Edmunds and Stowmarket Scale: 1:25 000. Publisher:Ordnance Survey – Southampton A ...

and then Norwich

Norwich () is a cathedral city and district of Norfolk, England, of which it is the county town. Norwich is by the River Wensum, about north-east of London, north of Ipswich and east of Peterborough. As the seat of the See of Norwich, with ...

. In 1614, he was Lent Reader

A reader in one of the Inns of Court in London was originally a senior barrister of the Inn who was elected to deliver a lecture or series of lectures on a particular legal topic. Two readers (known as Lent and Autumn Readers) would be elected annu ...

at Lincoln's Inn, and on 13 October of the same year became serjeant-at-law

A Serjeant-at-Law (SL), commonly known simply as a Serjeant, was a member of an order of barristers at the English and Irish Bar. The position of Serjeant-at-Law (''servientes ad legem''), or Sergeant-Counter, was centuries old; there are writ ...

. At about the same time he was made chancellor to the queen

Queen or QUEEN may refer to:

Monarchy

* Queen regnant, a female monarch of a Kingdom

** List of queens regnant

* Queen consort, the wife of a reigning king

* Queen dowager, the widow of a king

* Queen mother, a queen dowager who is the mother ...

.

Speaker of the House of Commons

In 1621, Richardson was electedMember of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members of ...

for St Albans

St Albans () is a cathedral city in Hertfordshire, England, east of Hemel Hempstead and west of Hatfield, Hertfordshire, Hatfield, north-west of London, south-west of Welwyn Garden City and south-east of Luton. St Albans was the first major ...

. Browne Willis ''Notitia parliamentaria, or, An history of the counties, cities, and boroughs in England and Wales: ... The whole extracted from mss. and printed evidences'' 1750 pp. 176-195"> Browne Willis ''Notitia parliamentaria, or, An history of the counties, cities, and boroughs in England and Wales: ... The whole extracted from mss. and printed evidences'' 1750 pp. 176-195/ref> When Parliament met on 30 January 1621, he was chosen Speaker of the House of Commons. The excuses which he made before accepting this office appear to have been more than formal, for an eye-witness reports that he "wept downright". On 25 March 1621, he was

knighted

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the Christian denomination, church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood ...

at Whitehall

Whitehall is a road and area in the City of Westminster, Central London. The road forms the first part of the A roads in Zone 3 of the Great Britain numbering scheme, A3212 road from Trafalgar Square to Chelsea, London, Chelsea. It is the main ...

when he brought King James congratulations of the commons upon the recent censure of Sir Giles Mompesson

Giles Mompesson (c. 1583 – 1663) was an English office holder and courtier who sat in the House of Commons between 1614 and 1621, when he was sentenced for corruption. He was officially a "notorious criminal" whose career was based on speculat ...

. In the chair, he proved a veritable King Log

The Frogs Who Desired a King is one of Aesop's Fables and numbered 44 in the Perry Index. Throughout its history, the story has been given a political application.

The fable

According to the earliest source, Phaedrus, the story concerns a gro ...

and his term of office was marked by the degradation of Bacon

Bacon is a type of salt-cured pork made from various cuts, typically the belly or less fatty parts of the back. It is eaten as a side dish (particularly in breakfasts), used as a central ingredient (e.g., the bacon, lettuce, and tomato sand ...

. He was not re-elected to parliament in the next election.

Judicial advancement

On 20 February 1625, Richardson was madeking's serjeant

A Serjeant-at-Law (SL), commonly known simply as a Serjeant, was a member of an order of barristers at the English and Irish Bar. The position of Serjeant-at-Law (''servientes ad legem''), or Sergeant-Counter, was centuries old; there are writ ...

. On 28 November 1626, he succeeded Sir Henry Hobart as Chief Justice of the Common Pleas

The chief justice of the Common Pleas was the head of the Court of Common Pleas, also known as the Common Bench or Common Place, which was the second-highest common law court in the English legal system until 1875, when it, along with the other ...

, after a vacancy of nearly a year. His advancement was said to have cost him £17,000 and his second marriage (see infra). He judged on 13 November 1628, that it was illegal to use the rack to elicit confession from Felton, the murderer of Duke of Buckingham's. His opinion had the concurrence of his colleagues and marks a significant point in the history of English criminal jurisprudence. In the following December he presided at the trial of three of the Jesuits

The Society of Jesus ( la, Societas Iesu; abbreviation: SJ), also known as the Jesuits (; la, Iesuitæ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

arrested in Clerkenwell

Clerkenwell () is an area of central London, England.

Clerkenwell was an ancient parish from the mediaeval period onwards, and now forms the south-western part of the London Borough of Islington.

The well after which it was named was redisco ...

, and secured the acquittal of two of them by requiring proof, which was not forthcoming, of their orders.

In the same year he took part in the careful review of the law of constructive treason Constructive treason is the judicial extension of the statutory definition of the crime of treason. For example, the English Treason Act 1351 declares it to be treason "When a Man doth compass or imagine the Death of our Lord the King". This was su ...

This arose from the case of Hugh Pine who was charged with that crime for speaking words that were derogatory to the king's majesty. The result of Richardsons's review was to limit the offence to cases of imagining the king's death. He concurred in the guarded and somewhat evasive opinion on the extent of privilege of parliament which the king

King is the title given to a male monarch in a variety of contexts. The female equivalent is queen, which title is also given to the consort of a king.

*In the context of prehistory, antiquity and contemporary indigenous peoples, the tit ...

elicited from the judges after the turbulent scenes which preceded the dissolution of parliament on 4 March 1629. He was as lenient as he could be when he imposed a fine of £500 without imprisonment in the case of Richard Chambers, and his agreement with harsh sentences passed upon Alexander Leighton

Alexander Leighton (c. 15701649) was a Scottish medical doctor and puritan preacher and pamphleteer best known for his 1630 pamphlet that attacked the Anglican church and which led to his torture by King Charles I.

Early life

Leighton was ...

and William Prynne

William Prynne (1600 – 24 October 1669), an English lawyer, voluble author, polemicist and political figure, was a prominent Puritan opponent of church policy under William Laud, Archbishop of Canterbury (1633–1645). His views were presbyter ...

may have been dictated by timidity, and there contrast strongly with the tenderness which he showed Henry Sherfield

Henry Sherfield (1572 (baptised) – January 1634) was an English lawyer and politician who sat in the House of Commons from 1621 to 1629. He held strong Puritan views, and was taken through a celebrated court case as a result of his iconoclastic ...

, the iconoclastic bencher of Lincoln's Inn.

Chief Justice of the King’s Bench

Richardson was advanced to the chief-justiceship of the king's bench on 24 October 1631, and served on the western circuit. He was not a

Richardson was advanced to the chief-justiceship of the king's bench on 24 October 1631, and served on the western circuit. He was not a puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Catholic Church, Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become m ...

but in Lent 1632 he made and order, at the instance of the Somerset

( en, All The People of Somerset)

, locator_map =

, coordinates =

, region = South West England

, established_date = Ancient

, established_by =

, preceded_by =

, origin =

, lord_lieutenant_office =Lord Lieutenant of Somerset

, lord_ ...

magistrates, for suppressing the 'wakes' or Sunday revels, which were a fertile source of crime in the county.

He directed the order to be read in church and this brought him into conflict with Laud, who sent for him and told him it was the king's pleasure he should rescind the order. Richardson ignored this instruction until the king

King is the title given to a male monarch in a variety of contexts. The female equivalent is queen, which title is also given to the consort of a king.

*In the context of prehistory, antiquity and contemporary indigenous peoples, the tit ...

himself repeated it. He then, at the ensuing summer Assizes

The courts of assize, or assizes (), were periodic courts held around England and Wales until 1972, when together with the quarter sessions they were abolished by the Courts Act 1971 and replaced by a single permanent Crown Court. The assizes e ...

(1633), laid the matter fairly before the justices and grand jury, professing his inability to comply with the royal mandate on the ground that the order had been made by the joint consent of the whole bench, and was in fact a mere confirmation and enlargement of similar orders made in the county since the time of Queen Elizabeth, all which he substantiated from the county records. This caused him to be cited before the council, reprimanded, and transferred to the Essex circuit. 'I am like,' he muttered as he left the council board, 'to be choked with the archbishop's lawn sleeves.'

Death

Richardson died at his house inChancery Lane

Chancery Lane is a one-way street situated in the ward of Farringdon Without in the City of London. It has formed the western boundary of the City since 1994, having previously been divided between the City of Westminster and the London Boroug ...

on 4 February 1635 and was buried in the north aisle of the choir of Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

, beneath a marble monument. There is a bust by Hubert Le Sueur

Hubert Le Sueur (c. 1580 – 1658) was a French sculptor with the contemporaneous reputation of having trained in Giambologna's Florentine workshop. He assisted Giambologna's foreman, Pietro Tacca, in Paris, in finishing and erecting the equestria ...

.

Judicial reputation

Richardson was a capable lawyer and a weak man, much addicted to flouts and jeers. 'Let him have the ''Book of Martyrs

The ''Actes and Monuments'' (full title: ''Actes and Monuments of these Latter and Perillous Days, Touching Matters of the Church''), popularly known as Foxe's Book of Martyrs, is a work of Protestant history and martyrology by Protestant Engl ...

he said, when the question whether Prynne should be allowed the use of books was before the court; 'for the puritans do account him a martyr.' He could also make a caustic jest at his own expense. 'You see now’ he dryly remarked, as he avoided a missile aimed at him by a condemned felon by stooping low, 'if I had been an upright judge I had been slain.' He possessed some polite learning, which caused John Taylor, the water poet, to dedicate to him one of the impressions of his ''Superbiae Flagellum'' (1621).

Marriages and issue

Richardson married twice:

*Firstly to Ursula Southwell (d.1624), the third daughter of John Southwell of Barham Hall in

Richardson married twice:

*Firstly to Ursula Southwell (d.1624), the third daughter of John Southwell of Barham Hall in Suffolk

Suffolk () is a ceremonial county of England in East Anglia. It borders Norfolk to the north, Cambridgeshire to the west and Essex to the south; the North Sea lies to the east. The county town is Ipswich; other important towns include Lowes ...

. She was buried at St. Andrew's, Holborn, on 13 June 1624. By Ursula Southwell, he had twelve children, including:

**Sir Thomas Richardson (d. 12 March 1645), K.B., ''Master of Cramond'', who by special remainder

In property law of the United Kingdom and the United States and other common law countries, a remainder is a future interest given to a person (who is referred to as the transferee or remainderman) that is capable of becoming possessory upon the n ...

became the heir apparent

An heir apparent, often shortened to heir, is a person who is first in an order of succession and cannot be displaced from inheriting by the birth of another person; a person who is first in the order of succession but can be displaced by the b ...

to the Scottish title of his step-mother Elizabeth, 1st Baroness Cramond (d.1651), but predeceased her. He married firstly Elizabeth Hewett, a daughter of Sir William Hewett of Pishiobury, Sawbridgeworth, Hertfordshire. The title was inherited by his son Thomas Richardson, 2nd Lord Cramond

Thomas Richardson, 2nd Lord Cramond (19 June 162716 May 1674) of Honingham Hall, Norfolk was an English politician who sat in the House of Commons from 1660 to 1674.

Richardson was the son of Sir Thomas Richardson and his wife Elizabeth Hewitt ...

(1627–74), of Honingham. The title became extinct in 1735 on the death, without issue, of William Richardson, 5th Lord Cramond.

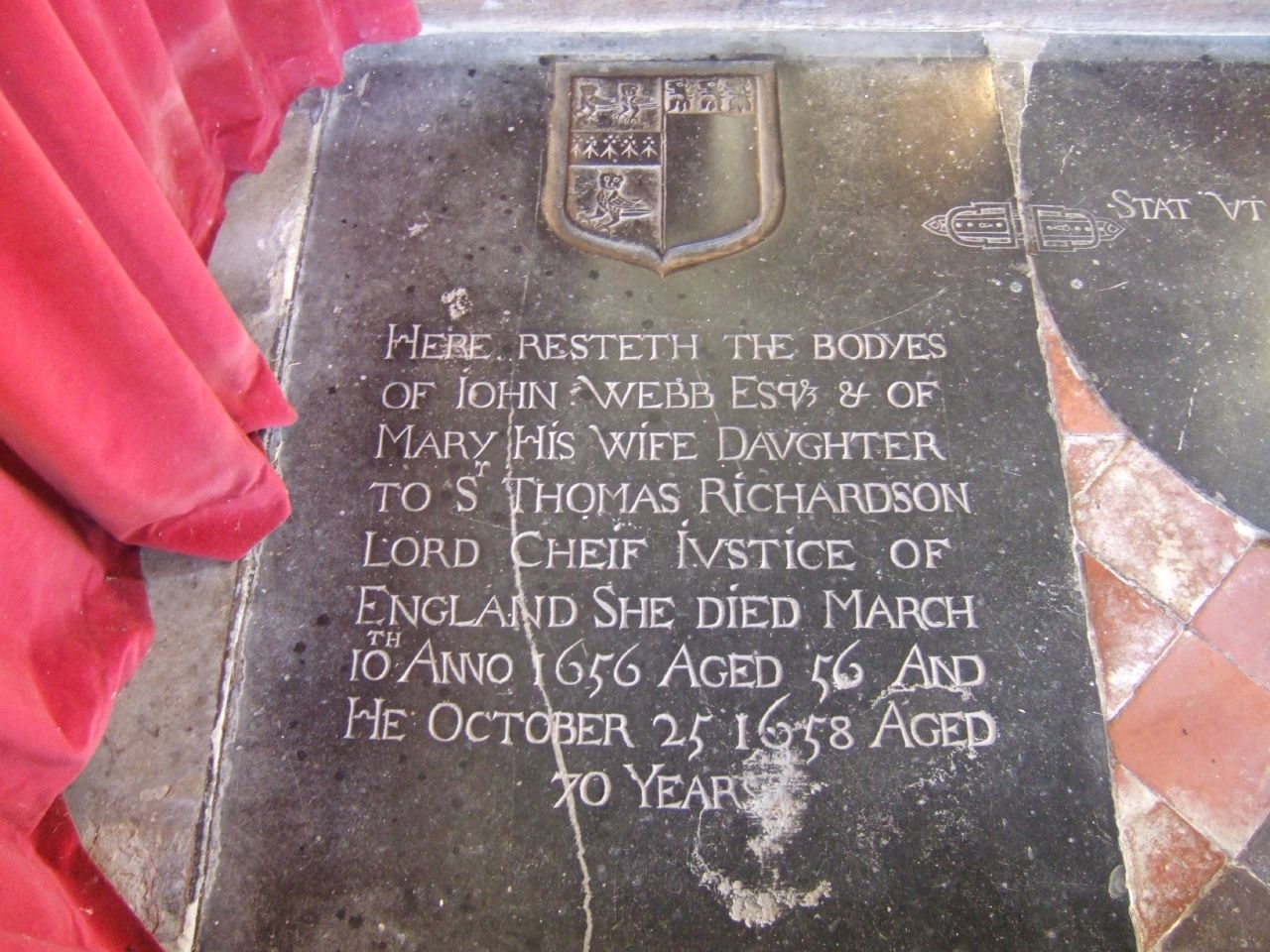

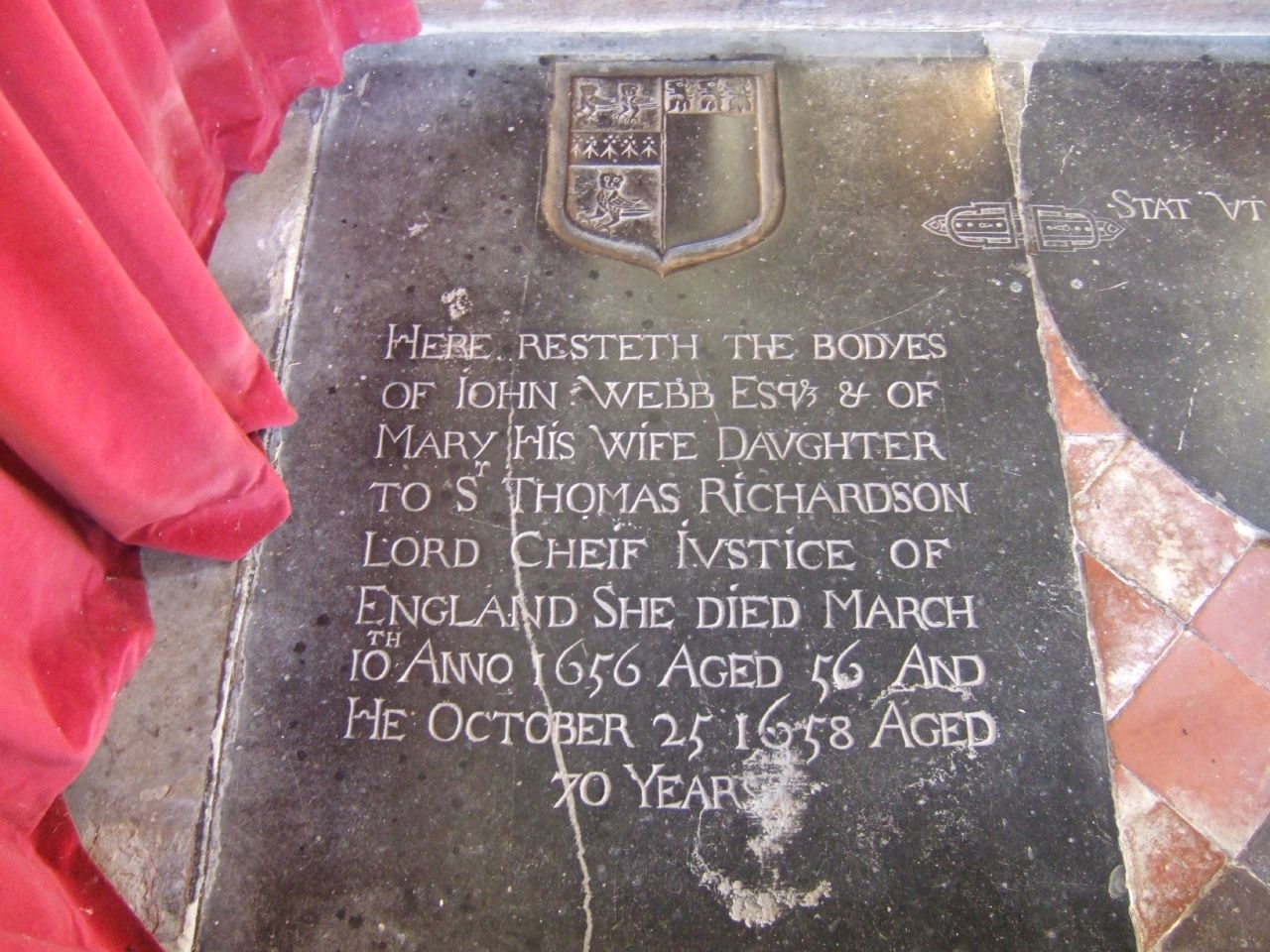

**Mary Richardson (1600 – 10 March 1656/7) who married John Webb (1588 – 25 October 1658) of Breckles in Norfolk.Inscribed ledger stone in Breckles Church, Norfolk :File:St Margaret's church Breckles Norfolk (264010538).jpg The couple's inscribed ledger stone survives in Breckles Church.

**Elizabeth Richardson (1607 – 13 July 1655), 3rd daughter, who married Robert Wood (4 August 1601 – 31 December 1680) of Braconash, the grandson of Sir Robert Wood

Sir Robert Wood of Norwich, Norfolk, was an English politician.

He was Mayor of Norwich, and was knighted by Queen Elizabeth I in 1578.

He was knighted on Queen Elizabeth I's progress in Norfolk. Francis Blomefield, Rector of Fersfield in Nor ...

of Norwich.

*Secondly, at St Giles in the Fields

St Giles in the Fields is the Anglican parish church of the St Giles district of London. It stands within the London Borough of Camden and belongs to the Diocese of London. The church, named for St Giles the Hermit, began as a monastery and ...

, Middlesex, on 14 December 1626, he married Elizabeth Beaumont (d.1651), widow of Sir John Ashburnham and a daughter of Sir Thomas Beaumont of Stoughton, Leicestershire. She was the maternal second cousin once removed of George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham

George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham, 28 August 1592 – 23 August 1628), was an English courtier, statesman, and patron of the arts. He was a favourite and possibly also a lover of King James I of England. Buckingham remained at the ...

. Without issue. On 28 February 1629, Elizabeth was created Lady Cramond

The title of Lord (of) Cramond was a title in the nobility of Scotland. It was created on 23 February 1628 for Dame Elizabeth Richardson. She was married to Sir Thomas Richardson, the second marriage for both, and had no children together. The ...

in the peerage of Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the ...

, for life, with special remainder

In property law of the United Kingdom and the United States and other common law countries, a remainder is a future interest given to a person (who is referred to as the transferee or remainderman) that is capable of becoming possessory upon the n ...

to her stepson Sir Thomas Richardson, KB, who died in her lifetime on 12 March 1645, and thus his son Thomas Richardson succeeded to the peerage on her death in April 1651. The title became extinct by the death, without issue, of William Richardson, 5th Lord Cramond, in 1735.

References

AttributionBibliography

*External links

* * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Richardson, Thomas 1569 births 1635 deaths Chief Justices of the Common Pleas Speakers of the House of Commons of England English MPs 1621–1622 Lord chief justices of England and Wales People educated at Norwich School Alumni of Christ's College, Cambridge Members of Lincoln's Inn People from Shelton and Hardwick 16th-century English judges 17th-century English judges Politicians from Norwich People from Honingham Judges from Norwich Knights Bachelor