Thomas Richard Pearce on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Thomas Richard Pearce (1859–1908), born Thomas Richard Millett, was an Irish ship master in the UK merchant marine. He served his apprenticeship on

Thomas Richard Millett was born on 31 October 1859 at Millbrook, near

Thomas Richard Millett was born on 31 October 1859 at Millbrook, near

Pearce was on duty in the small hours of 1 June when ''Loch Ard'' struck rocks on the

Pearce was on duty in the small hours of 1 June when ''Loch Ard'' struck rocks on the  In the water three passengers, Reginald Jones, Arthur Mitchell, and the Carmichaels' second daughter, Eva, clung to a

In the water three passengers, Reginald Jones, Arthur Mitchell, and the Carmichaels' second daughter, Eva, clung to a  Pearce planned to move from Glenample to stay with an aunt in the Toorak area of Melbourne. On 20 June the Victorian Humane Society held its annual award ceremony in Melbourne Town Hall. Sir

Pearce planned to move from Glenample to stay with an aunt in the Toorak area of Melbourne. On 20 June the Victorian Humane Society held its annual award ceremony in Melbourne Town Hall. Sir

Pearce was engaged to Edith Strasenburgh, whose brother Robert was a fellow-apprentice killed on ''Loch Ard''. On 14 August 1884 they were married at

Pearce was engaged to Edith Strasenburgh, whose brother Robert was a fellow-apprentice killed on ''Loch Ard''. On 14 August 1884 they were married at

On 21 November 1906 in

On 21 November 1906 in

By 1942 Robert was Master of the refrigerated cargo ship . She was unusually swift for a cargo ship, capable of up to , so she was selected to take part in

By 1942 Robert was Master of the refrigerated cargo ship . She was unusually swift for a cargo ship, capable of up to , so she was selected to take part in

sailing ship

A sailing ship is a sea-going vessel that uses sails mounted on masts to harness the power of wind and propel the vessel. There is a variety of sail plans that propel sailing ships, employing square-rigged or fore-and-aft sails. Some ships c ...

s with Aitken & Lilburn's Loch Line

The Loch Line of Glasgow, Scotland, was a group of colonial clippers managed by Messrs William Aitken and James Lilburn. They plied between the United Kingdom and Australia from 1867 to 1911.Fayle, Charles (2006)''A Short History of the World's S ...

, and then rose through the ranks on steamship

A steamship, often referred to as a steamer, is a type of steam-powered vessel, typically ocean-faring and seaworthy, that is propelled by one or more steam engines that typically move (turn) propellers or paddlewheels. The first steamships ...

s with the Royal Mail Steam Packet Company

The Royal Mail Steam Packet Company was a British shipping company founded in London in 1839 by a Scot, James MacQueen. The line's motto was ''Per Mare Ubique'' (everywhere by sea). After a troubled start, it became the largest shipping group ...

(RMSP).

On sailing ships Pearce survived three shipwrecks: those of ''Eliza Ramsden'' in 1875, in 1878, and in 1879. When ''Loch Ard'' was wrecked he saved a passenger from drowning, for which the Victorian Humane Society awarded him his first ever Gold Medal.

Pearce's stepfather was a ship master, both of Pearce's sons went to sea, and all three died in shipwrecks. In 1906 Pearce took early retirement due to ill-health. His death in 1908, aged only 49, prompted RMSP to found its superannuation fund

A pension fund, also known as a superannuation fund in some countries, is any plan, fund, or scheme which provides retirement income.

Pension funds typically have large amounts of money to invest and are the major investors in listed and priva ...

.

Upbringing

Thomas Richard Millett was born on 31 October 1859 at Millbrook, near

Thomas Richard Millett was born on 31 October 1859 at Millbrook, near Cappawhite

Cappawhite, also Cappaghwhite (), is a village in County Tipperary, Ireland and is located on the R505 regional road from Cashel to County Limerick. Close major towns near the village include Tipperary Town which is 12 kilometres south of the v ...

, County Tipperary

County Tipperary ( ga, Contae Thiobraid Árann) is a county in Ireland. It is in the province of Munster and the Southern Region. The county is named after the town of Tipperary, and was established in the early 13th century, shortly after th ...

, Ireland. He was the son of Richard and Emily Millett. Richard was an engineer, emigrated with his wife and children to Melbourne

Melbourne ( ; Boonwurrung/Woiwurrung: ''Narrm'' or ''Naarm'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Victoria, and the second-most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Its name generally refers to a met ...

, and then travelled on business to New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island count ...

, where in 1874 he died. Captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

Robert George Augustus Pearce married his widow, and Thomas Richard Millett took Pearce's surname. In 1875 RGA Pearce was killed when his command, , was wrecked off the coast of Queensland

)

, nickname = Sunshine State

, image_map = Queensland in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Queensland in Australia

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, established_ ...

.

Thomas Richard Pearce, as he now was, began his marine apprenticeship

Apprenticeship is a system for training a new generation of practitioners of a Tradesman, trade or profession with on-the-job training and often some accompanying study (classroom work and reading). Apprenticeships can also enable practitioners ...

with a voyage to Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

. Then he was a member of the crew of the sailing barque ''Eliza Ramsden'', when she was wrecked just inside Port Phillip

Port Phillip (Kulin languages, Kulin: ''Narm-Narm'') or Port Phillip Bay is a horsehead-shaped bay#Types, enclosed bay on the central coast of southern Victoria (Australia), Victoria, Australia. The bay opens into the Bass Strait via a short, ...

Heads on 24 July 1875. That was exactly five months after his stepfather was killed on ''Gothenburg''.

''Loch Ard''

By early 1877 Pearce was with Messrs Aitken and Lilburn ofGlasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popul ...

, and was serving on ''Loch Ard'' between the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

and Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a Sovereign state, sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous List of islands of Australia, sma ...

.

Pearce was on ''Loch Ard'' in February 1878, when she loaded cargo at East India Docks

The East India Docks were a group of docks in Blackwall, east London, north-east of the Isle of Dogs. Today only the entrance basin and listed perimeter wall remain visible.

History Early history

Following the successful creation of the We ...

in London. This was his third voyage on her. She called at Gravesend

Gravesend is a town in northwest Kent, England, situated 21 miles (35 km) east-southeast of Charing Cross (central London) on the Bank (geography), south bank of the River Thames and opposite Tilbury in Essex. Located in the diocese of Ro ...

, Kent

Kent is a county in South East England and one of the home counties. It borders Greater London to the north-west, Surrey to the west and East Sussex to the south-west, and Essex to the north across the estuary of the River Thames; it faces ...

, where her compasses were adjusted. She left there on 1, 2 or 3 March 1878 (reports differ). She was carrying cargo, 17 passengers and 37 crew, bound for Melbourne

Melbourne ( ; Boonwurrung/Woiwurrung: ''Narrm'' or ''Naarm'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Victoria, and the second-most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Its name generally refers to a met ...

. The passengers included a Dr and Mrs Carmichael from Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of th ...

, a wealthy couple who were emigrating with their four daughters and two sons.

Pearce was on duty in the small hours of 1 June when ''Loch Ard'' struck rocks on the

Pearce was on duty in the small hours of 1 June when ''Loch Ard'' struck rocks on the Shipwreck Coast

The Shipwreck Coast of Victoria, Australia stretches from Cape Otway to Port Fairy, a distance of approximately 130 km. This coastline is accessible via the Great Ocean Road, and is home to the limestone formations called The Twelve Apos ...

of Victoria

Victoria most commonly refers to:

* Victoria (Australia), a state of the Commonwealth of Australia

* Victoria, British Columbia, provincial capital of British Columbia, Canada

* Victoria (mythology), Roman goddess of Victory

* Victoria, Seychelle ...

. Passengers came on deck, some wearing only their nightclothes. The ship had four boats, including a lifeboat on the port

A port is a maritime facility comprising one or more wharves or loading areas, where ships load and discharge cargo and passengers. Although usually situated on a sea coast or estuary, ports can also be found far inland, such as Ham ...

side and a gig

Gig or GIG may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Gig'' (Circle Jerks album) (1992)

* ''Gig'' (Northern Pikes album) (1993)

* ''The Gig'', a 1985 film written and directed by Frank D. Gilroy

* GIG, a character in ''Hot Wheels AcceleRacers'' ...

. These were the only boats carried the right way up, ready to be launched. The other boats were stowed bottom up.

Some reports said that the ship had only five lifebelts and six lifejackets. Dr Carmichael and the ship's steward got the lifejackets out of the ship's lazarette

The lazarette (also spelled lazaret) of a boat is an area near or aft of the cockpit. The word is similar to and probably derived from lazaretto. A lazarette is usually a storage locker used for gear or equipment a sailor or boatswain would us ...

, and put them on six of the passengers: Dr and Mrs Carmichael, their elder daughters Raby and Eva, and a Mr and Mrs Stuckey. The jackets were in poor condition, and their strings broke several times when fastened.

The lifeboat was washed overboard. Pearce and five crewmen were in the boat for a few minutes, but it capsized. Pearce found himself under the boat, but swam out. The boat righted and capsized again more than once, but each time Pearce clung to its upturned keel. The boat and other wreckage drifted into an inlet that was then called The Caves and is now called Loch Ard Gorge

The Loch Ard Gorge is part of Port Campbell National Park, Victoria, Australia, about three minutes' drive west of The Twelve Apostles.

History

The gorge is named after the clipper that was shipwrecked on 1 June 1878 near the end of a thre ...

. There it struck a rock, throwing Pearce into the water. He swam ashore, using a floating table as a buoyancy aid.

In the water three passengers, Reginald Jones, Arthur Mitchell, and the Carmichaels' second daughter, Eva, clung to a

In the water three passengers, Reginald Jones, Arthur Mitchell, and the Carmichaels' second daughter, Eva, clung to a hen coop

Poultry farming is the form of animal husbandry which raises domesticated birds such as chickens, ducks, turkeys and geese to produce meat or eggs for food. Poultry – mostly chickens – are farmed in great numbers. More than 60 billion ch ...

that was floating among the wreckage. The coop kept turning over, so the trio transferred to a floating spar

SPAR, originally DESPAR, styled as DE SPAR, is a Dutch multinational that provides branding, supplies and support services for independently owned and operated food retail stores. It was founded in the Netherlands in 1932, by Adriaan van Well, ...

. Later Jones and then Mitchell were washed away, and Carmichael lost consciousness, but her lifejacket and the spar kept her afloat and alive. Later she regained consciousness, but she did not know how to swim. Pearce heard her call for help and swam out. It took him an hour in the rough sea to bring her ashore in the gorge. Pearce and Carmichael were the only survivors of the 54 people aboard. Each was 19 years old.

Carmichael was cold and weak. Pearce brought her to a cave under a cliff, then found two coats and a case of brandy among the wreckage. He gave the coats to Carmichael, and they shared a half-bottle of brandy. He rested for a couple of hours, then left Carmichael asleep and climbed about up a cliff. He found and followed a track. Early that afternoon he met a man on horseback called George Ford. Ford rode for help to Glenample at Curdie's Inlet, the station

Station may refer to:

Agriculture

* Station (Australian agriculture), a large Australian landholding used for livestock production

* Station (New Zealand agriculture), a large New Zealand farm used for grazing by sheep and cattle

** Cattle statio ...

of Peter McArthur, JP, and Hugh Gibson. Gibson and some men rode to the gorge, and brought a buggy to carry Carmichael, but she had woken up and wandered away. They found her about from where Pearce left her, and then with some difficulty helped her up the cliff.

Pearce and Carmichael stayed with for some days at Glenample. Pearce helped with the recovery of salvage and identification of bodies from the wreck, while Mrs Gibson nursed Carmichael. The bodies of Carmichael's mother and her elder sister Raby were found, as well of those of Jones and Mitchell, and on 5 June the four were buried on the clifftop. By 7 June a Captain Trouton of the Australasian Steam Navigation Company

The Australasian Steam Navigation Company (ASN Co) was a shipping company of Australia which operated between 1839 and 1887.

Company history

The company was started as the Hunter River Steam Navigation Company in 1839. In March 1851, the compa ...

in Sydney

Sydney ( ) is the capital city of the state of New South Wales, and the most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Sydney Harbour and extends about towards the Blue Mountain ...

had started a subscription fund to make a presentation to Pearce as a reward for saving Carmichael.

On 15 June the Mayor of Melbourne

This is a list of the mayors and lord mayors of the City of Melbourne, a Local government in Australia, local government area of Victoria (Australia), Victoria, Australia.

Mayors (1842–1902)

Lord mayors (1902–1980)

The title of "Lord ...

chaired a meeting at Melbourne Town Hall

Melbourne Town Hall is the central city town hall of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, and is a historic building in the state of Victoria since 1867. Located in the central business district on the northeast corner of the intersection between S ...

to decide how best to use the various public donations being made as a testimonial to Pearce. A group of horseracing gamblers had donated £32 10 s, and Melbourne City Corporation staff had donated £5. There were proposals that the money be spent on sending him to navigation college, or even that a ship be bought for him and named ''Eva Carmichael''. Aitken and Lilburn's agents in Melbourne were John Blyth & Co, whose representative told the meeting that when Pearce reached Melbourne he would join their ship ''Loch Shiel'' to complete his apprenticeship.

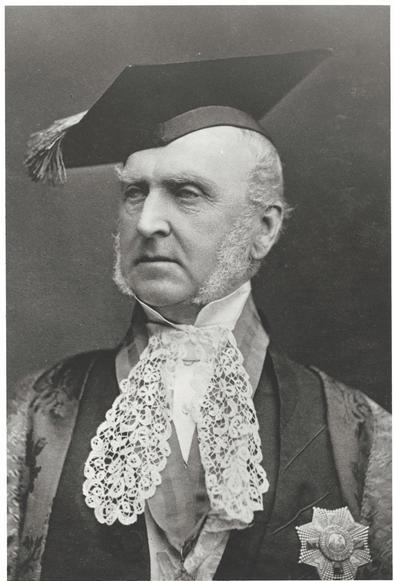

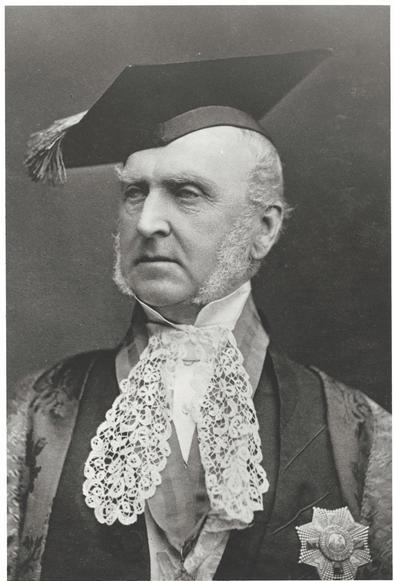

Pearce planned to move from Glenample to stay with an aunt in the Toorak area of Melbourne. On 20 June the Victorian Humane Society held its annual award ceremony in Melbourne Town Hall. Sir

Pearce planned to move from Glenample to stay with an aunt in the Toorak area of Melbourne. On 20 June the Victorian Humane Society held its annual award ceremony in Melbourne Town Hall. Sir Redmond Barry

Sir Redmond Barry, (7 June 181323 November 1880), was a colonial judge in Victoria, Australia of Anglo-Irish origins. Barry was the inaugural Chancellor of the University of Melbourne, serving from 1853 until his death in 1880. He is arguably ...

presented the awards, including a Gold Medal to Pearce, the first the Society had ever awarded.

On 21 June the Steam Navigation Board met at the Custom House in Melbourne to inquire into the loss of ''Loch Ard''. Pearce testified to the Board that a fortnight before the ship reached the Australian coast, he and the officers noted that the ship's compasses were slightly out of adjustment, with a slight disagreement between the standard and binnacle

A binnacle is a waist-high case or stand on the deck of a ship, generally mounted in front of the helmsman, in which navigational instruments are placed for easy and quick reference as well as to protect the delicate instruments. Its traditional p ...

compasses. Contrary to earlier newspaper reports, he told the inquiry that he believed the ship carried about 16 lifejackets.

According to a 1934 report, Pearce was engaged to be married, but he offered to Carmichael to break off his engagement and marry her instead. The report claims that she declined his offer as they had "nothing in common" and it would be wrong for him to abandon his fiancée.

On 18 July ''Loch Shiel'' left Hobson's Bay

The City of Hobsons Bay is a local government area in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. It comprises the south-western suburbs between 6 and 20 km from the Melbourne city centre.

It was founded on 22 June 1994 during the amalgamation of l ...

, bound for London, presumably with Pearce aboard. Carmichael returned to Ireland, where she later married a Thomas Townshend from County Cork

County Cork ( ga, Contae Chorcaí) is the largest and the southernmost county of Ireland, named after the city of Cork, the state's second-largest city. It is in the province of Munster and the Southern Region. Its largest market towns are ...

.

''Loch Sunart'' and ''Loch Katrine''

Pearce continued his apprenticeship in ''Loch Sunart''. In January 1879 she left Glasgow for Melbourne, but on 13 January she was wrecked on Skullmartin Rock inBallywalter

Ballywalter ( and ''Walter'') is a village or townland (of 437 acres) and civil parish in County Down, Northern Ireland. It is on the east (Irish Sea) coast of the Ards Peninsula between Donaghadee and Ballyhalbert. Ballywalter was formerly know ...

Bay, on the coast of the Ards Peninsula

The Ards Peninsula () is a peninsula in County Down, Northern Ireland, on the north-east coast of Ireland. It separates Strangford Lough from the North Channel of the Irish Sea. Towns and villages on the peninsula include Donaghadee, Millisle ...

, County Down

County Down () is one of the six counties of Northern Ireland, one of the nine counties of Ulster and one of the traditional thirty-two counties of Ireland. It covers an area of and has a population of 531,665. It borders County Antrim to the ...

. No lives were lost, and all passengers and crew were safely brought ashore in boats.

According to one account, Pearce completed his apprenticeship on another Aitken and Lilburn ship, ''Loch Katrine''.

Marriage and children

Pearce was engaged to Edith Strasenburgh, whose brother Robert was a fellow-apprentice killed on ''Loch Ard''. On 14 August 1884 they were married at

Pearce was engaged to Edith Strasenburgh, whose brother Robert was a fellow-apprentice killed on ''Loch Ard''. On 14 August 1884 they were married at St George's, Hanover Square

St George's, Hanover Square, is an Anglican church, the parish church of Mayfair in the City of Westminster, central London, built in the early eighteenth century as part of a project to build fifty new churches around London (the Queen Anne C ...

, London. They had two sons and a daughter. Both sons were apprenticed to Aitken and Lilburn: the elder, Thomas William Pearce, in ''Loch Vennachar

''Loch Vennachar'' was an iron-hulled, three-masted clipper ship that was built in Scotland in 1875 and lost with all hands off the coast of South Australia in 1905. She spent her entire career with the Glasgow Shipping Company, trading betwee ...

'' and the younger, Robert Strasenburgh Pearce, in ''Loch Etive''.

On an unknown date in September 1905 ''Loch Vennachar'' was lost with all hands on the west coast of Kangaroo Island

Kangaroo Island, also known as Karta Pintingga (literally 'Island of the Dead' in the language of the Kaurna people), is Australia's third-largest island, after Tasmania and Melville Island. It lies in the state of South Australia, southwest ...

, South Australia

South Australia (commonly abbreviated as SA) is a state in the southern central part of Australia. It covers some of the most arid parts of the country. With a total land area of , it is the fourth-largest of Australia's states and territories ...

. Thomas William was one of three apprentices killed in the wreck. It was his fourth trip to Australia aboard her.

''Orinoco'' and ''Trent''

After his apprenticeship with Aitken and Lilburn, Pearce changed to steamships and rose through the ranks of the Royal Mail Steam Packet Company. By 1905 he was Master of an RMSP ship "trading betweenSouthampton

Southampton () is a port city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. It is located approximately south-west of London and west of Portsmouth. The city forms part of the South Hampshire built-up area, which also covers Po ...

and the West Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Greater A ...

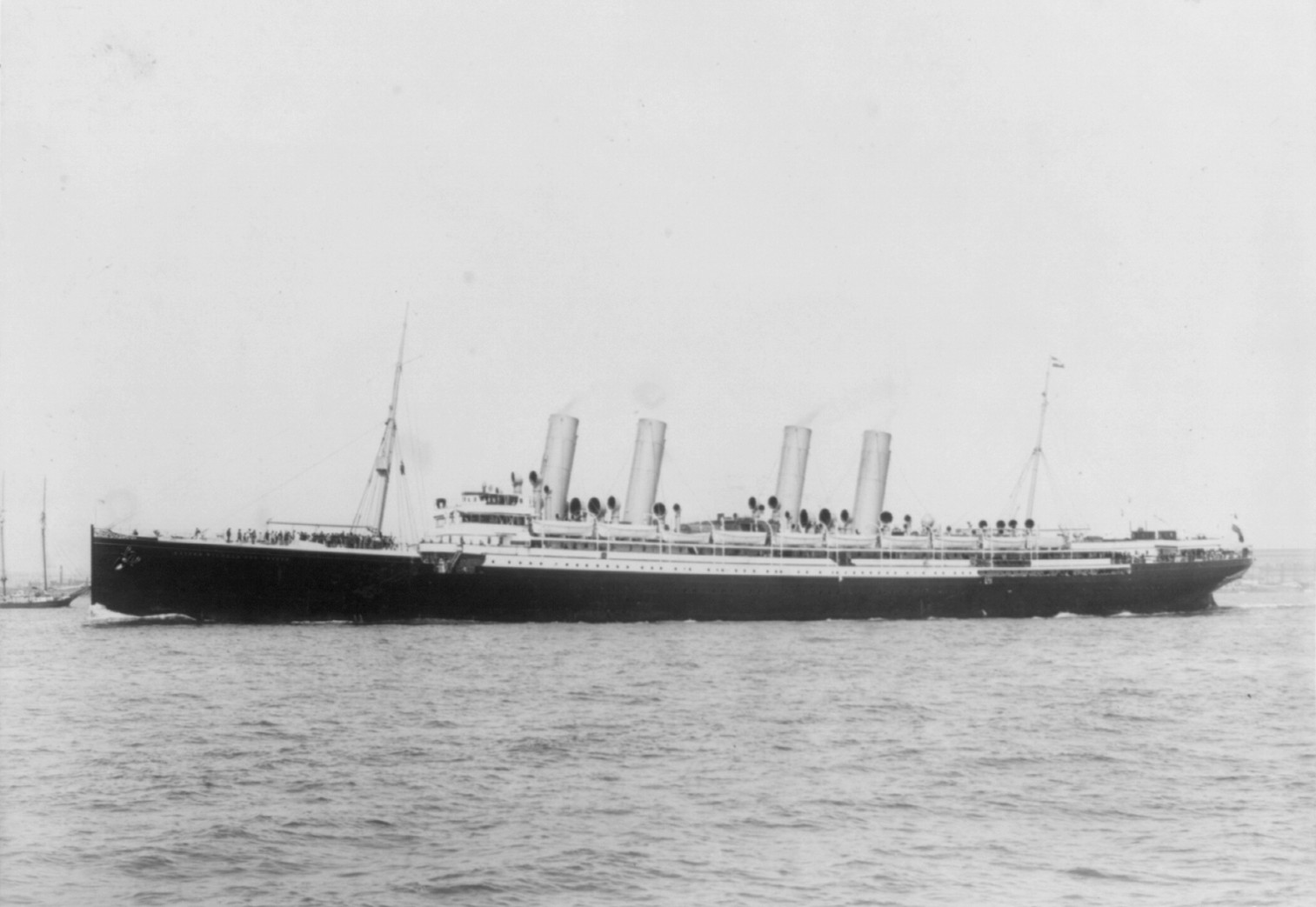

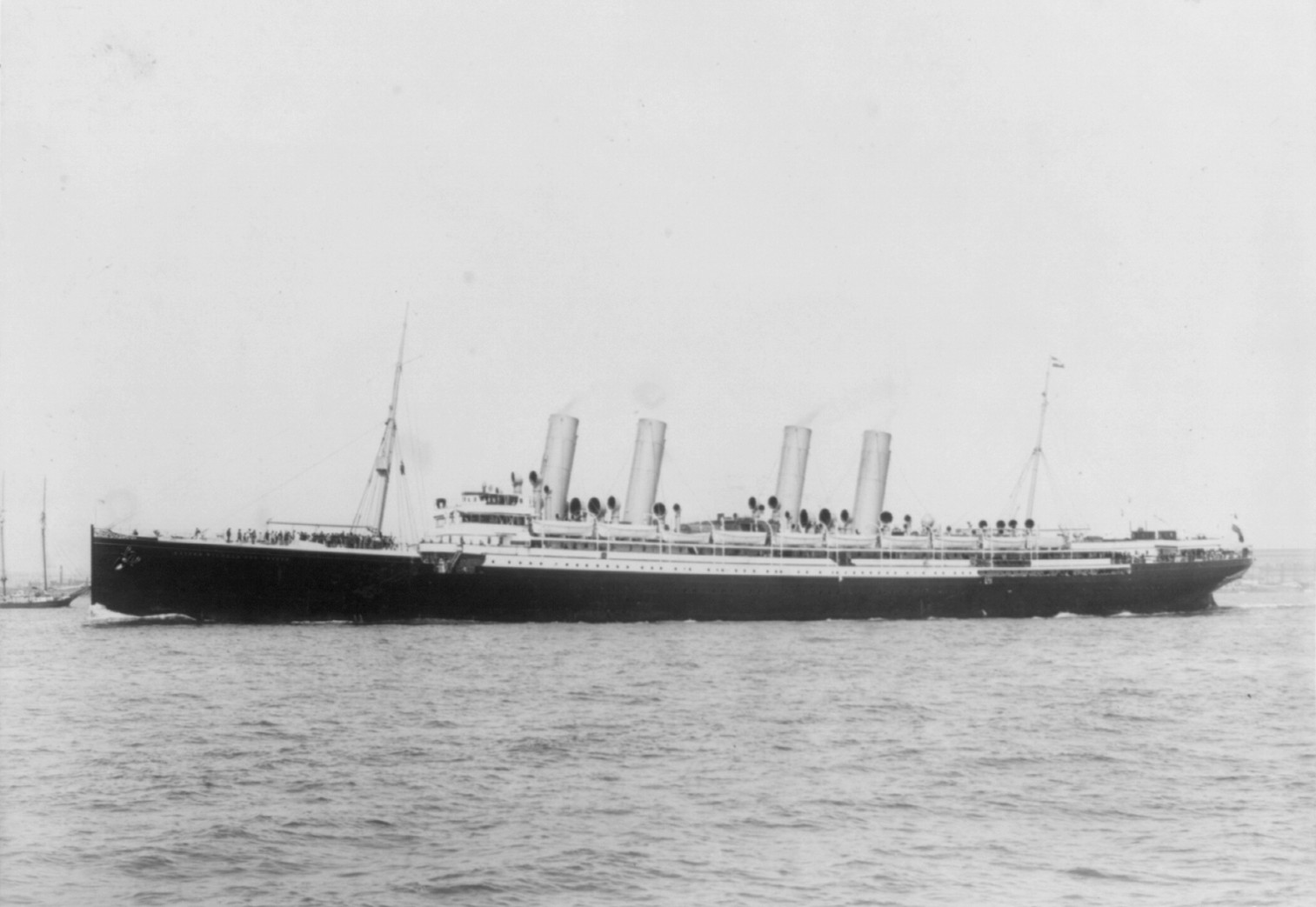

". In 1906 he was given command of the liner .

On 21 November 1906 in

On 21 November 1906 in Cherbourg

Cherbourg (; , , ), nrf, Chèrbourg, ) is a former commune and subprefecture located at the northern end of the Cotentin peninsula in the northwestern French department of Manche. It was merged into the commune of Cherbourg-Octeville on 28 Feb ...

Harbour ''Orinoco'' collided in fog with the Norddeutscher Lloyd

Norddeutscher Lloyd (NDL; North German Lloyd) was a German shipping company. It was founded by Hermann Henrich Meier and Eduard Crüsemann in Bremen on 20 February 1857. It developed into one of the most important German shipping companies of th ...

transatlantic

Transatlantic, Trans-Atlantic or TransAtlantic may refer to:

Film

* Transatlantic Pictures, a film production company from 1948 to 1950

* Transatlantic Enterprises, an American production company in the late 1970s

* ''Transatlantic'' (1931 film), ...

ocean liner

An ocean liner is a passenger ship primarily used as a form of transportation across seas or oceans. Ocean liners may also carry cargo or mail, and may sometimes be used for other purposes (such as for pleasure cruises or as hospital ships).

Ca ...

. ''Orinoco''s clipper bow penetrated ''Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse''s starboard

Port and starboard are nautical terms for watercraft and aircraft, referring respectively to the left and right sides of the vessel, when aboard and facing the bow (front).

Vessels with bilateral symmetry have left and right halves which are ...

side, killing four people aboard the German ship and at least one on ''Orinoco''. A court of inquiry found ''Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse'' wholly responsible for the collision.

RMSP then gave Pearce command of the liner , also trading between Southampton and the West Indies. However, less than two years after the collision he was relieved of his command due to ill-health. He died on 14 December 1908, and is buried in Southampton Old Cemetery

The cemetery has had various titles including The Cemetery by the Common, Hill Lane Cemetery and is currently known as Southampton Old Cemetery. An Act of Parliament was required in 1843 to acquire the land from Southampton Common. It covers an ...

.

RMSP deputed one of its Directors to attend Pearce's funeral. There is no record of RMSP having taken such a step for the death of any officer previously. Edith Pearce was widowed with two surviving children. Some RMSP Directors proposed paying her £500 ''ex gratia''. Others disagreed, so the Court of Directors held a special meeting. The meeting not only approved the proposal to pay her £500, but also decided to establish a superannuation fund to provide for retirees and their dependants.

Robert Pearce

Robert Pearce completed his apprenticeship with Aitken and Lilburn. In October 1915 he was commissioned as asub-lieutenant

Sub-lieutenant is usually a junior officer rank, used in armies, navies and air forces.

In most armies, sub-lieutenant is the lowest officer rank. However, in Brazil, it is the highest non-commissioned rank, and in Spain, it is the second high ...

in the Royal Naval Reserve

The Royal Naval Reserve (RNR) is one of the two volunteer reserve forces of the Royal Navy in the United Kingdom. Together with the Royal Marines Reserve, they form the Maritime Reserve. The present RNR was formed by merging the original Ro ...

. By December 1918 he was a full lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often sub ...

and was mentioned in dispatches

To be mentioned in dispatches (or despatches, MiD) describes a member of the armed forces whose name appears in an official report written by a superior officer and sent to the high command, in which their gallant or meritorious action in the face ...

at Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

. In October 1919 he was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross The Distinguished Service Cross (D.S.C.) is a military decoration for courage. Different versions exist for different countries.

*Distinguished Service Cross (Australia)

*Distinguished Service Cross (United Kingdom)

*Distinguished Service Cross (U ...

. One source says Robert was on a minesweeping

Minesweeping is the practice of the removal of explosive naval mines, usually by a specially designed ship called a minesweeper using various measures to either capture or detonate the mines, but sometimes also with an aircraft made for that ...

naval trawler

Naval trawlers are vessels built along the lines of a fishing trawler but fitted out for naval purposes; they were widely used during the First and Second World Wars. Some—known in the Royal Navy as "Admiralty trawlers"— were purpose-built to ...

when she accidentally hauled aboard a live mine

Mine, mines, miners or mining may refer to:

Extraction or digging

* Miner, a person engaged in mining or digging

*Mining, extraction of mineral resources from the ground through a mine

Grammar

*Mine, a first-person English possessive pronoun

...

. It detonated, sinking the trawler, and Robert was one of only two survivors. Another source says he served on Q-ship

Q-ships, also known as Q-boats, decoy vessels, special service ships, or mystery ships, were heavily armed merchant ships with concealed weaponry, designed to lure submarines into making surface attacks. This gave Q-ships the chance to open f ...

s.

In his Merchant Navy career, Robert served with Aberdeen and Commonwealth Line and then Shaw, Savill & Albion Line

Shaw, Savill & Albion Line was the trading name of Shaw, Savill and Albion Steamship Company, a British shipping company that operated ships between Great Britain, Australia and New Zealand.

History

The company was created in 1882 by the ama ...

. He lived in the Watson's Bay suburb of Sydney

Sydney ( ) is the capital city of the state of New South Wales, and the most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Sydney Harbour and extends about towards the Blue Mountain ...

. By the early 1930s he was Chief Officer

A chief mate (C/M) or chief officer, usually also synonymous with the first mate or first officer, is a licensed mariner and head of the deck department of a merchant ship. The chief mate is customarily a watchstander and is in charge of the ship ...

on the refrigerated cargo steamship ''Pakeha''. Eva Townshend, by then widowed and living in Bedford

Bedford is a market town in Bedfordshire, England. At the 2011 Census, the population of the Bedford built-up area (including Biddenham and Kempston) was 106,940, making it the second-largest settlement in Bedfordshire, behind Luton, whilst ...

, England, traced him with the help of a London newspaper, and wrote asking to meet him and "talk over the old days".

By 1942 Robert was Master of the refrigerated cargo ship . She was unusually swift for a cargo ship, capable of up to , so she was selected to take part in

By 1942 Robert was Master of the refrigerated cargo ship . She was unusually swift for a cargo ship, capable of up to , so she was selected to take part in Operation Pedestal

Operation Pedestal ( it, Battaglia di Mezzo Agosto, Battle of mid-August), known in Malta as (), was a British operation to carry supplies to the island of Malta in August 1942, during the Second World War. Malta was a base from which British ...

to relieve Malta. The cargo in her holds included ammunition, and her deck cargo included containers of aviation spirit. ''Waimarama'' sailed in convoy from the Firth of Clyde

The Firth of Clyde is the mouth of the River Clyde. It is located on the west coast of Scotland and constitutes the deepest coastal waters in the British Isles (it is 164 metres deep at its deepest). The firth is sheltered from the Atlantic ...

via Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

to the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the e ...

.

On 13 August, enemy torpedo boat

A torpedo boat is a relatively small and fast naval ship designed to carry torpedoes into battle. The first designs were steam-powered craft dedicated to ramming enemy ships with explosive spar torpedoes. Later evolutions launched variants of se ...

s and aircraft attacked the convoy. Three or four bombs dropped by a Junkers Ju 88

The Junkers Ju 88 is a German World War II ''Luftwaffe'' twin-engined multirole combat aircraft. Junkers Aircraft and Motor Works (JFM) designed the plane in the mid-1930s as a so-called ''Schnellbomber'' ("fast bomber") that would be too fast ...

hit ''Waimarama''. Within minutes she "blew up with a roar and a sheet of flame with clouds of billowing smoke". Robert Pearce was killed, along with all but two of her crew. In February 1943 he was posthumously mentioned in dispatches "For gallantry, skill and resolution while an important Convoy was fought through to Malta in the face of relentless attacks by day and night from enemy aircraft, submarines and surface forces".

References

Bibliography

* * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Pearce, Thomas 1859 births 1908 deaths 19th-century sailors British Merchant Navy officers Burials at Southampton Old Cemetery People from County Tipperary Shipwreck survivors