Thomas Palaiologos on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Thomas Palaiologos or Palaeologus ( el, Θωμᾶς Παλαιολόγος; 1409 – 12 May 1465) was

As the

As the

Shortly after being appointed as despots, Constantine and Thomas, together with Theodore, decided to join forces in an attempt to seize the flourishing and strategic port of

Shortly after being appointed as despots, Constantine and Thomas, together with Theodore, decided to join forces in an attempt to seize the flourishing and strategic port of

Among the actions taken during the brothers' project of strengthening the despotate was to reconstruct the Hexamilion wall, destroyed by the Turks in 1431. Together, they completely restored the wall, which was finished in March 1444. The wall was destroyed by the Turks again in 1446 after Constantine had attempted to expand his control northwards and had refused the sultan's demands of dismantling the wall. Constantine and Thomas were determined to hold the wall and had brought all their available forces, amounting to perhaps as many as twenty thousand men, to defend it. Despite this, the battle by the wall in 1446 was an overwhelming Turkish victory, with Constantine and Thomas barely escaping with their lives. Turahan Bey was sent south to take Mystras and devastate Constantine's lands while Sultan Murad II led his forces in the north of the Peloponnese. Although Turahan failed to take Mystras, this was of little consequence as Murad did not wish to conquer the Morea at the time, merely to instill terror, and the Turks soon left the peninsula, devastated and depopulated. Constantine and Thomas were in no position to ask for a truce and were forced to accept Murad as their lord and pay him tribute, promising to never again restore the Hexamilion wall.

Their former co-despot Theodore died in June 1448, and on 31 October of the same year, Emperor John VIII passed away. The potential successors to the throne were Constantine, Demetrios and Thomas. John had not formally designated and heir, though everyone knew he favored Constantine and ultimately, the will of their mother,

Among the actions taken during the brothers' project of strengthening the despotate was to reconstruct the Hexamilion wall, destroyed by the Turks in 1431. Together, they completely restored the wall, which was finished in March 1444. The wall was destroyed by the Turks again in 1446 after Constantine had attempted to expand his control northwards and had refused the sultan's demands of dismantling the wall. Constantine and Thomas were determined to hold the wall and had brought all their available forces, amounting to perhaps as many as twenty thousand men, to defend it. Despite this, the battle by the wall in 1446 was an overwhelming Turkish victory, with Constantine and Thomas barely escaping with their lives. Turahan Bey was sent south to take Mystras and devastate Constantine's lands while Sultan Murad II led his forces in the north of the Peloponnese. Although Turahan failed to take Mystras, this was of little consequence as Murad did not wish to conquer the Morea at the time, merely to instill terror, and the Turks soon left the peninsula, devastated and depopulated. Constantine and Thomas were in no position to ask for a truce and were forced to accept Murad as their lord and pay him tribute, promising to never again restore the Hexamilion wall.

Their former co-despot Theodore died in June 1448, and on 31 October of the same year, Emperor John VIII passed away. The potential successors to the throne were Constantine, Demetrios and Thomas. John had not formally designated and heir, though everyone knew he favored Constantine and ultimately, the will of their mother,

Constantinople ultimately

Constantinople ultimately

Neither brother could raise the sum demanded by the Sultan and they were divided in their policies. While Demetrios, probably the more realistic of the two, had more or less given up hope of Christian aid from the west and thought it might be best to placate the Turks, Thomas retained hope that the Papacy might yet call for a crusade to restore the Byzantine Empire. Thomas's hopes were not ridiculous; the Fall of Constantinople had been received with as much horror in Western Europe as it had been in the few remaining Byzantine territories in the East. In September 1453,

Neither brother could raise the sum demanded by the Sultan and they were divided in their policies. While Demetrios, probably the more realistic of the two, had more or less given up hope of Christian aid from the west and thought it might be best to placate the Turks, Thomas retained hope that the Papacy might yet call for a crusade to restore the Byzantine Empire. Thomas's hopes were not ridiculous; the Fall of Constantinople had been received with as much horror in Western Europe as it had been in the few remaining Byzantine territories in the East. In September 1453,

In the end, no crusade ever set out to combat the Ottomans. Due to their conviction that help would arrive, and being unable to pay, the two despots had not paid their annual tribute to the Ottomans for three years. With no money coming from the Morea, and the looming threat of Western aid, Mehmed eventually lost his patience with the Palaiologoi. The Ottoman army marched from Adrianople in May 1458 and entered the Morea, where the only real resistance was faced at

In the end, no crusade ever set out to combat the Ottomans. Due to their conviction that help would arrive, and being unable to pay, the two despots had not paid their annual tribute to the Ottomans for three years. With no money coming from the Morea, and the looming threat of Western aid, Mehmed eventually lost his patience with the Palaiologoi. The Ottoman army marched from Adrianople in May 1458 and entered the Morea, where the only real resistance was faced at

When Thomas had first heard of Mehmed's invasion, he had initially taken refuge at

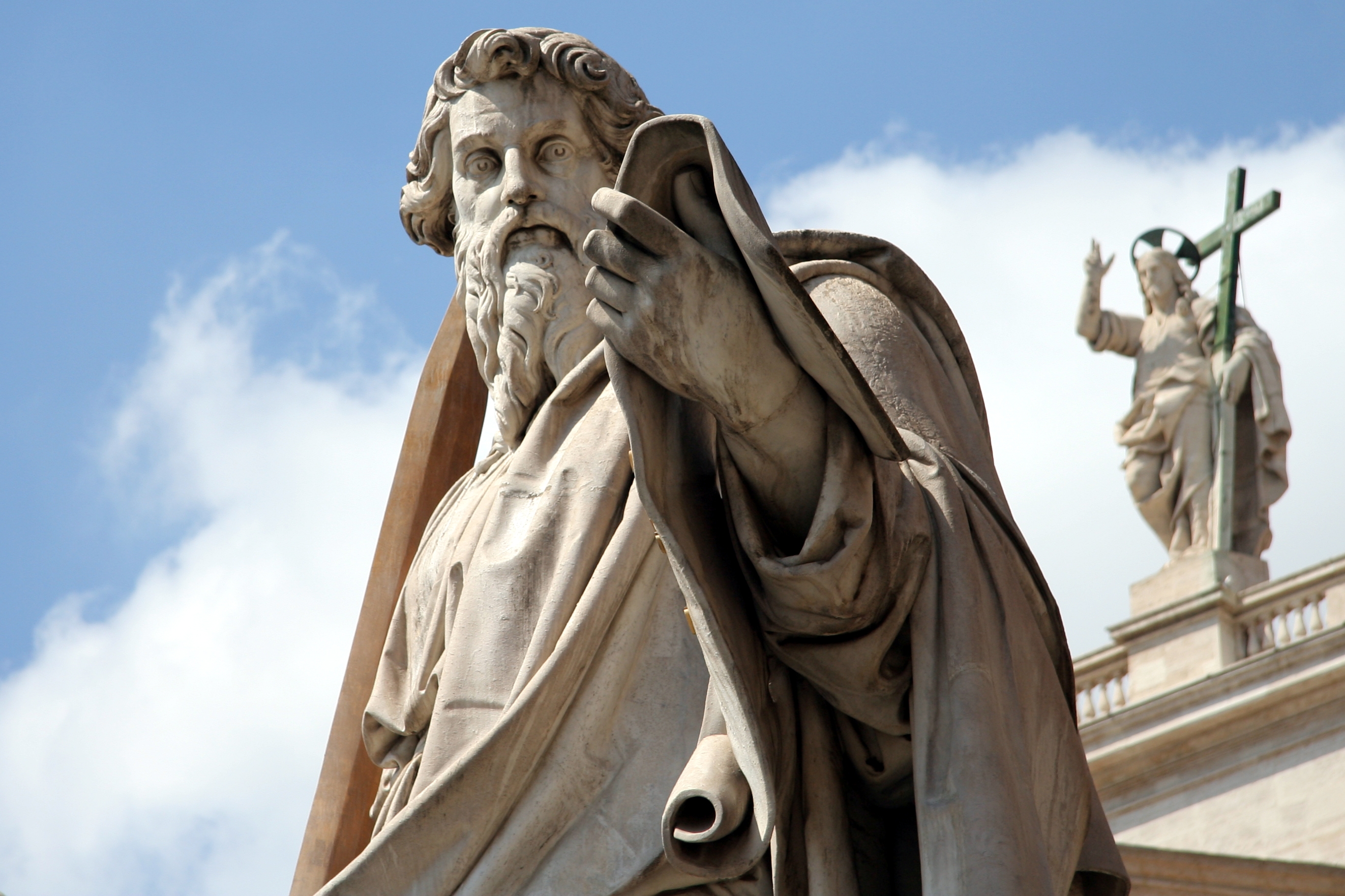

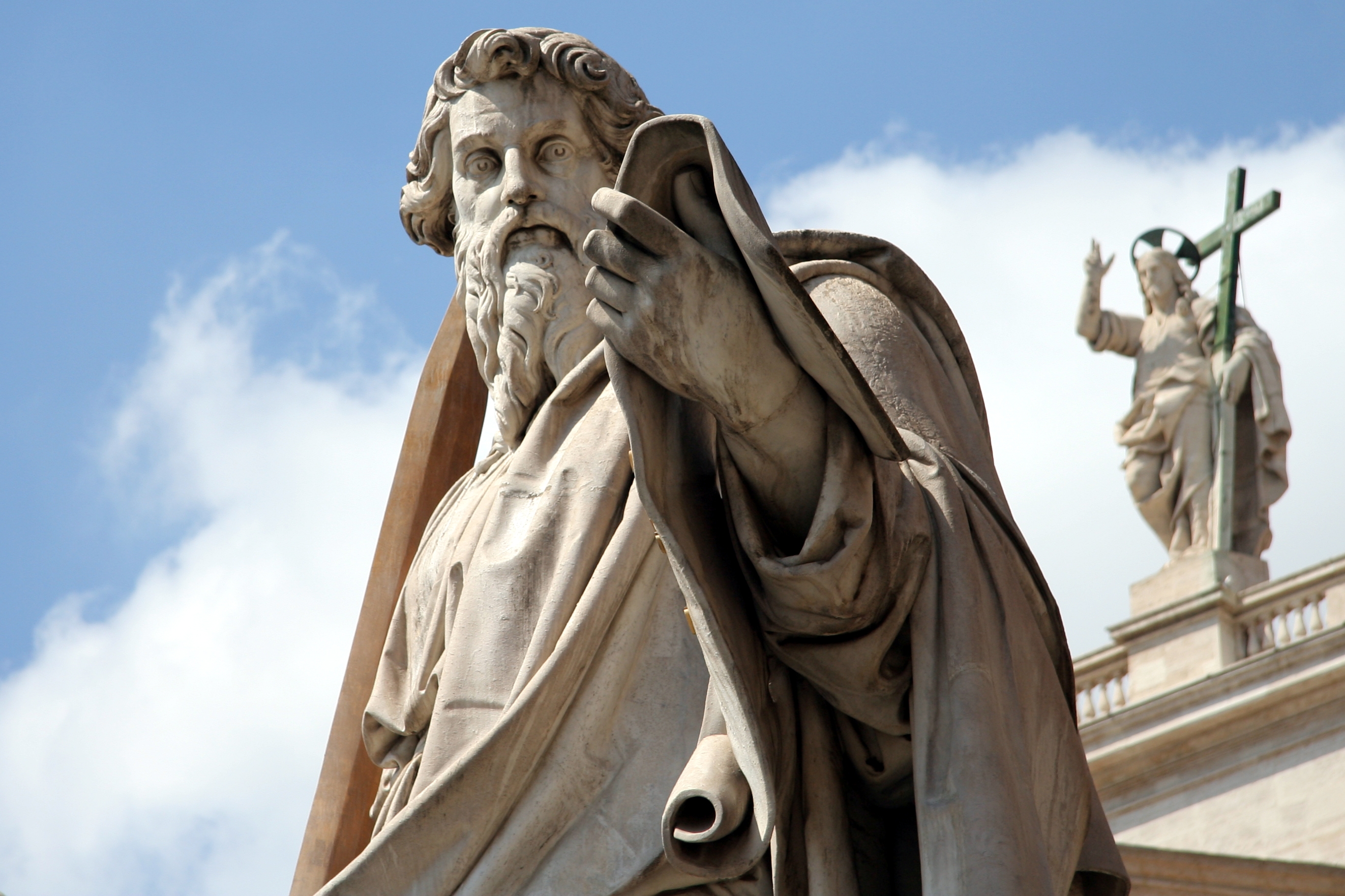

When Thomas had first heard of Mehmed's invasion, he had initially taken refuge at  During his stay in Rome, Thomas, on account of his "tall and handsome appearance", served as the model of the statue of

During his stay in Rome, Thomas, on account of his "tall and handsome appearance", served as the model of the statue of

It is generally accepted that Thomas had four children with Catherine Zaccaria, due to George Sphrantzes giving this number. These four children were:

*

It is generally accepted that Thomas had four children with Catherine Zaccaria, due to George Sphrantzes giving this number. These four children were:

*

Despot of the Morea

The Despotate of the Morea ( el, Δεσποτᾶτον τοῦ Μορέως) or Despotate of Mystras ( el, Δεσποτᾶτον τοῦ Μυστρᾶ) was a province of the Byzantine Empire which existed between the mid-14th and mid-15th centu ...

from 1428 until the fall of the despotate in 1460, although he continued to claim the title until his death five years later. He was the younger brother of Constantine XI Palaiologos

Constantine XI Dragases Palaiologos or Dragaš Palaeologus ( el, Κωνσταντῖνος Δραγάσης Παλαιολόγος, ''Kōnstantînos Dragásēs Palaiológos''; 8 February 1405 – 29 May 1453) was the last List of Byzantine em ...

, the final Byzantine emperor

This is a list of the Byzantine emperors from the foundation of Constantinople in 330 AD, which marks the conventional start of the Eastern Roman Empire, to its fall to the Ottoman Empire in 1453 AD. Only the emperors who were recognized as le ...

. Thomas was appointed as Despot of the Morea by his oldest brother, Emperor John VIII Palaiologos

John VIII Palaiologos or Palaeologus ( gr, Ἰωάννης Παλαιολόγος, Iōánnēs Palaiológos; 18 December 1392 – 31 October 1448) was the penultimate Byzantine emperor, ruling from 1425 to 1448.

Biography

John VIII was ...

, in 1428, joining his two brothers and other despots Theodore

Theodore may refer to:

Places

* Theodore, Alabama, United States

* Theodore, Australian Capital Territory

* Theodore, Queensland, a town in the Shire of Banana, Australia

* Theodore, Saskatchewan, Canada

* Theodore Reservoir, a lake in Sask ...

and Constantine, already governing the Morea. Though Theodore proved reluctant to cooperate with his brothers, Thomas and Constantine successfully worked to strengthen the despotate and expand its borders. In 1432, Thomas brought the remaining territories of the Latin Principality of Achaea

The Principality of Achaea () or Principality of Morea was one of the three vassal states of the Latin Empire, which replaced the Byzantine Empire after the capture of Constantinople during the Fourth Crusade. It became a vassal of the Kingdom o ...

, established during the Fourth Crusade

The Fourth Crusade (1202–1204) was a Latin Christian armed expedition called by Pope Innocent III. The stated intent of the expedition was to recapture the Muslim-controlled city of Jerusalem, by first defeating the powerful Egyptian Ayyubid S ...

more than two hundred years earlier, into Byzantine hands by marrying Catherine Zaccaria Catherine Zaccaria or Catherine Palaiologina ( grc-x-medieval, Αἰκατερίνα Παλαιολογίνα; died 26 August 1462) was the daughter of the last Prince of Achaea, Centurione II Zaccaria. In September 1429 she was betrothed to the Byz ...

, daughter and heir to the principality.

In 1449, Thomas supported the ascension of his brother Constantine, who then became Emperor Constantine XI, to the throne despite the machinations of his other brother, Demetrios

Demetrius is the Latinized form of the Ancient Greek male given name ''Dēmḗtrios'' (), meaning “Demetris” - "devoted to goddess Demeter".

Alternate forms include Demetrios, Dimitrios, Dimitris, Dmytro, Dimitri, Dimitrie, Dimitar, Dumit ...

, who himself desired the throne. After Constantine's rise to the throne, Demetrios was then assigned by Constantine to govern the Morea with Thomas but the two brothers found it difficult to cooperate, often quarreling with each other. In the aftermath of the Fall of Constantinople

The Fall of Constantinople, also known as the Conquest of Constantinople, was the capture of the capital of the Byzantine Empire by the Ottoman Empire. The city fell on 29 May 1453 as part of the culmination of a 53-day siege which had begun o ...

and end of the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

in 1453, Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II

Mehmed II ( ota, محمد ثانى, translit=Meḥmed-i s̱ānī; tr, II. Mehmed, ; 30 March 14323 May 1481), commonly known as Mehmed the Conqueror ( ota, ابو الفتح, Ebū'l-fetḥ, lit=the Father of Conquest, links=no; tr, Fâtih Su ...

allowed Thomas and Demetrios to continue to rule as Ottoman vassals in the Morea. Thomas hoped to turn the small despotate into a rallying point of a campaign to restore the empire, hoping to gain support from the Papacy

The pope ( la, papa, from el, πάππας, translit=pappas, 'father'), also known as supreme pontiff ( or ), Roman pontiff () or sovereign pontiff, is the bishop of Rome (or historically the patriarch of Rome), head of the worldwide Cathol ...

and Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's countries and territories vary depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the ancient Mediterranean ...

. Constant quarreling with Demetrios, who supported the Ottomans instead, eventually led Mehmed to invade and conquer the Morea in 1460.

Thomas and his family, including his wife Catherine and his three younger children Zoe, Andreas

Andreas ( el, Ἀνδρέας) is a name usually given to males in Austria, Greece, Cyprus, Denmark, Armenia, Estonia, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Finland, Flanders

Flanders (, ; Dutch: ''Vlaanderen'' ) is the Flemish-speaking northern portion of B ...

and Manuel, escaped into exile to the Venetian-held city of Methoni and then to Corfu

Corfu (, ) or Kerkyra ( el, Κέρκυρα, Kérkyra, , ; ; la, Corcyra.) is a Greek island in the Ionian Sea, of the Ionian Islands, and, including its small satellite islands, forms the margin of the northwestern frontier of Greece. The isl ...

, where Catherine and the children stayed. In the hopes of raising support for a crusade to restore his lands in the Morea, and possibly the Byzantine Empire itself, Thomas travelled to Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

, where he was received and provided for by Pope Pius II

Pope Pius II ( la, Pius PP. II, it, Pio II), born Enea Silvio Bartolomeo Piccolomini ( la, Aeneas Silvius Bartholomeus, links=no; 18 October 1405 – 14 August 1464), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 19 August ...

. His hopes of retaking the Morea never materialized and he died in Rome on 12 May 1465. After his death, his claims were inherited by his oldest son Andreas, who also attempted to rally support for a campaign to restore the fallen despotate and the Byzantine Empire.

Biography

Early life and appointment as despot

Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

fell apart and fragmented over the course of the 14th century, the emperors of the Palaiologan

The House of Palaiologos ( Palaiologoi; grc-gre, Παλαιολόγος, pl. , female version Palaiologina; grc-gre, Παλαιολογίνα), also found in English-language literature as Palaeologus or Palaeologue, was a Byzantine Greek ...

dynasty came to feel that the only sure way to keep their remaining holdings intact was to grant them to their sons, receiving the title of despot, as appanages to defend and govern. Emperor Manuel II Palaiologos

Manuel II Palaiologos or Palaeologus ( gr, Μανουὴλ Παλαιολόγος, Manouēl Palaiológos; 27 June 1350 – 21 July 1425) was Byzantine emperor from 1391 to 1425. Shortly before his death he was tonsured a monk and received the n ...

(1391–1425) had a total of six sons who survived infancy. Manuel's eldest surviving son, John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Secon ...

, was raised to co-emperor and designated to succeed Manuel as sole emperor upon his death. The second eldest son, Theodore

Theodore may refer to:

Places

* Theodore, Alabama, United States

* Theodore, Australian Capital Territory

* Theodore, Queensland, a town in the Shire of Banana, Australia

* Theodore, Saskatchewan, Canada

* Theodore Reservoir, a lake in Sask ...

was designated as Despot of the Morea

The Despotate of the Morea ( el, Δεσποτᾶτον τοῦ Μορέως) or Despotate of Mystras ( el, Δεσποτᾶτον τοῦ Μυστρᾶ) was a province of the Byzantine Empire which existed between the mid-14th and mid-15th centu ...

and the third eldest, Andronikos, was made Despot of Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki (; el, Θεσσαλονίκη, , also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece, with over one million inhabitants in its Thessaloniki metropolitan area, metropolitan area, and the capi ...

in 1408 at just eight years old. Manuel's younger sons, Constantine

Constantine most often refers to:

* Constantine the Great, Roman emperor from 306 to 337, also known as Constantine I

*Constantine, Algeria, a city in Algeria

Constantine may also refer to:

People

* Constantine (name), a masculine given name ...

, Demetrios

Demetrius is the Latinized form of the Ancient Greek male given name ''Dēmḗtrios'' (), meaning “Demetris” - "devoted to goddess Demeter".

Alternate forms include Demetrios, Dimitrios, Dimitris, Dmytro, Dimitri, Dimitrie, Dimitar, Dumit ...

, and Thomas (the youngest, born in 1409), were kept in Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

as there was not sufficient land left to grant them. The younger children; Theodore, Andronikos, Constantine, Demetrios and Thomas were frequently described as having the distinction of Porphyrogennetos

Traditionally, born in the purple (sometimes "born to the purple") was a category of members of royal families born during the reign of their parent. This notion was later loosely expanded to include all children born of prominent or high-ranking ...

("born in the purple"; born in the imperial palace during the reign of their father), a distinction that does not appear to have been shared by the emperor-to-be John.

Relations between the Palaiologos brothers were not always good. Though the young John and Constantine appears to have got on well with each other, relations between Constantine and the younger Demetrios and Thomas were not as friendly. The complex relationships between the sons of Manuel II were put to the test when John, now Emperor John VIII, appointed Constantine as Despot of the Morea in 1428. Since his brother Theodore refused to step down from his role as despot, the despotate became governed by two members of the imperial family for the first time since its creation in 1349. Soon thereafter, the younger Thomas (aged 19) was also appointed as Despot of the Morea, meaning that the nominally undivided despotate had effectively disintegrated into three smaller principalities.

Theodore did not make way for Constantine or Thomas in the despotate's capital, Mystras

Mystras or Mistras ( el, Μυστρᾶς/Μιστρᾶς), also known in the '' Chronicle of the Morea'' as Myzithras (Μυζηθρᾶς), is a fortified town and a former municipality in Laconia, Peloponnese, Greece. Situated on Mt. Taygetus, ne ...

. Instead, Theodore granted Constantine lands throughout the Morea, including the northern harbor town of Aigio

Aigio, also written as ''Aeghion, Aegion, Aegio, Egio'' ( el, Αίγιο, Aígio, ; la, Aegium), is a town and a former municipality in Achaea, West Greece, on the Peloponnese. Since the 2011 local government reform, it is part of the municipali ...

, fortresses and towns in Laconia

Laconia or Lakonia ( el, Λακωνία, , ) is a historical and administrative region of Greece located on the southeastern part of the Peloponnese peninsula. Its administrative capital is Sparta. The word ''laconic''—to speak in a blunt, c ...

(in the south), and Kalamata

Kalamáta ( el, Καλαμάτα ) is the second most populous city of the Peloponnese peninsula, after Patras, in southern Greece and the largest city of the homonymous administrative region. As the capital and chief port of the Messenia reg ...

and Messenia

Messenia or Messinia ( ; el, Μεσσηνία ) is a regional unit (''perifereiaki enotita'') in the southwestern part of the Peloponnese region, in Greece. Until the implementation of the Kallikratis plan on 1 January 2011, Messenia was a ...

in the west. Constantine made his capital as despot the town Glarentza

Glarentza ( el, Γλαρέντζα), also known as or Clarenia, Clarence, or Chiarenza, was a medieval town located near the site of modern Kyllini in Elis, at the westernmost point of the Peloponnese peninsula in southern Greece. Founded in th ...

. Meanwhile, Thomas was given lands in the north and based himself in the castle of Kalavryta

Kalavryta ( el, Καλάβρυτα) is a town and a municipality in the mountainous east-central part of the regional unit of Achaea, Greece. The town is located on the right bank of the river Vouraikos, south of Aigio, southeast of Patras and ...

.

Despot under the Byzantine Empire

Strengthening the Morea

Patras

)

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demographics1_title2 =

, demographics1_info2 =

, timezone1 = EET

, utc_offset1 = +2

, ...

in the north-west of the Morea, then under the rule of its Catholic Archbishop. The campaign, which was unsuccessful, possibly due to Theodore's reluctance to partake, was Thomas's first experience of war. Constantine later captured Patras on his own, ending 225 years of foreign ownership.

Thomas's early tenure as Despot of the Morea was not without acquisitions either. For years, Thomas and Constantine had been eating away at the last remnants of the Principality of Achaea, a crusader state established during the Fourth Crusade

The Fourth Crusade (1202–1204) was a Latin Christian armed expedition called by Pope Innocent III. The stated intent of the expedition was to recapture the Muslim-controlled city of Jerusalem, by first defeating the powerful Egyptian Ayyubid S ...

in 1204 which had once governed almost the entire peninsula. It was Thomas who finally brought an end to the principality by marrying Catherine Zaccaria Catherine Zaccaria or Catherine Palaiologina ( grc-x-medieval, Αἰκατερίνα Παλαιολογίνα; died 26 August 1462) was the daughter of the last Prince of Achaea, Centurione II Zaccaria. In September 1429 she was betrothed to the Byz ...

, daughter and heir of the final prince, Centurione II Zaccaria

Centurione II Zaccaria (died 1432), scion of a powerful Genoese merchant family established in the Morea, was installed as Prince of Achaea by Ladislaus of Naples in 1404 and was the last ruler of the Latin Empire not under Byzantine suzerainty ...

. With Centurione's death in 1432, Thomas could claim control over all of his remaining territories. By the 1430s, Thomas and Constantine had ensured that nearly the entire Peloponnese was once more in Byzantine hands for the first time since 1204, the only exception being the few port towns and cities held by the Republic of Venice

The Republic of Venice ( vec, Repùblega de Venèsia) or Venetian Republic ( vec, Repùblega Vèneta, links=no), traditionally known as La Serenissima ( en, Most Serene Republic of Venice, italics=yes; vec, Serenìsima Repùblega de Venèsia, ...

.

Murad II

Murad II ( ota, مراد ثانى, Murād-ı sānī, tr, II. Murad, 16 June 1404 – 3 February 1451) was the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1421 to 1444 and again from 1446 to 1451.

Murad II's reign was a period of important economic deve ...

, Sultan of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

, which occupied most of the Byzantine Empire's former territory and had relegated the empire and the despotate as effectively vassal states, felt uneasy about the recent string of Byzantine successes in the Morea. In 1431, Turahan Bey

Turahan Bey or Turakhan Beg ( tr, Turahan Bey/Beğ; sq, Turhan Bej; el, Τουραχάνης, Τουραχάν μπέης or Τουραχάμπεης;PLP 29165 died in 1456) was a prominent Ottoman military commander and governor of Thessaly ...

, a Turkish general who governed Thessaly

Thessaly ( el, Θεσσαλία, translit=Thessalía, ; ancient Thessalian: , ) is a traditional geographic and modern administrative region of Greece, comprising most of the ancient region of the same name. Before the Greek Dark Ages, Thes ...

, sent his troops south to demolish the Morea's primary defensive fortifications, the Hexamilion wall

The Hexamilion wall ( el, Εξαμίλιον τείχος, "six-mile wall") was a defensive wall constructed across the Isthmus of Corinth, guarding the only land route onto the Peloponnese peninsula from mainland Greece.

History

Early for ...

, in an effort to remind the despots that they were the Sultan's vassals.

In March 1432, Constantine, possibly desiring to be closer to Mystras, made a new territorial agreement, presumably approved by Theodore and John VIII, with Thomas. Thomas agreed to cede his fortress Kalavryta to Constantine, who made it his new capital, in exchange for Elis

Elis or Ilia ( el, Ηλεία, ''Ileia'') is a historic region in the western part of the Peloponnese peninsula of Greece. It is administered as a regional unit of the modern region of Western Greece. Its capital is Pyrgos. Until 2011 it was ...

, which Thomas made his new capital. Though relations between the three despots thus appears to have been good in 1432, they soon soured. John VIII had no sons to succeed him and it was thus assumed that his successor would be one of his four surviving brothers (Andronikos having died some time before). John VIII's preferred successor was Constantine and though this choice was accepted by Thomas, who had developed good relations with his older brother, it was resented by the still older Theodore. When Constantine was summoned to the capital in 1435, Theodore believed this was to appoint Constantine as co-emperor and designated heir, which was not actually the case, and he too travelled to Constantinople to raise his objections. The quarrel between Constantine and Theodore was not resolved until the end of 1436, when the future Patriarch Gregory Mammas was sent to reconcile them and prevent civil war. When Constantine was summoned to act as regent in Constantinople while John VIII was away at the Council of Florence

The Council of Florence is the seventeenth ecumenical council recognized by the Catholic Church, held between 1431 and 1449. It was convoked as the Council of Basel by Pope Martin V shortly before his death in February 1431 and took place in ...

from 1437 to 1440, Theodore and Thomas stayed in the Morea. In November 1443, Constantine gave over control of Selymbria

Selymbria ( gr, Σηλυμβρία),Demosthenes, '' de Rhod. lib.'', p. 198, ed. Reiske. or Selybria (Σηλυβρία), or Selybrie (Σηλυβρίη), was a town of ancient Thrace on the Propontis, 22 Roman miles east from Perinthus, and 44 Rom ...

, which he had received after helping to deal with the rebellion of their younger brother Demetrios, to Theodore, who in turn abandoned his position as Despot of the Morea, making Constantine and Thomas the sole Despots of the Morea. Though this brought Theodore closer to Constantinople, it also made Constantine the ruler of the capital of the Morea and one of the most powerful men in the small empire. With Theodore and Demetrios out of their way, Constantine and Thomas hoped to strengthen the Morea, by now the cultural center of the Byzantine world, and make it a safe and nearly self-suffient principality. The philosopher Gemistus Pletho

Georgios Gemistos Plethon ( el, Γεώργιος Γεμιστός Πλήθων; la, Georgius Gemistus Pletho /1360 – 1452/1454), commonly known as Gemistos Plethon, was a Greek scholar and one of the most renowned philosophers of the late By ...

advocated that while Constantinople was the New Rome, Mystras and the Morea could become the "New Sparta

Sparta ( Doric Greek: Σπάρτα, ''Spártā''; Attic Greek: Σπάρτη, ''Spártē'') was a prominent city-state in Laconia, in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (, ), while the name Sparta referre ...

", a centralized and strong Hellenic kingdom in its own right.

Turkish attacks and the accession of Constantine XI

Among the actions taken during the brothers' project of strengthening the despotate was to reconstruct the Hexamilion wall, destroyed by the Turks in 1431. Together, they completely restored the wall, which was finished in March 1444. The wall was destroyed by the Turks again in 1446 after Constantine had attempted to expand his control northwards and had refused the sultan's demands of dismantling the wall. Constantine and Thomas were determined to hold the wall and had brought all their available forces, amounting to perhaps as many as twenty thousand men, to defend it. Despite this, the battle by the wall in 1446 was an overwhelming Turkish victory, with Constantine and Thomas barely escaping with their lives. Turahan Bey was sent south to take Mystras and devastate Constantine's lands while Sultan Murad II led his forces in the north of the Peloponnese. Although Turahan failed to take Mystras, this was of little consequence as Murad did not wish to conquer the Morea at the time, merely to instill terror, and the Turks soon left the peninsula, devastated and depopulated. Constantine and Thomas were in no position to ask for a truce and were forced to accept Murad as their lord and pay him tribute, promising to never again restore the Hexamilion wall.

Their former co-despot Theodore died in June 1448, and on 31 October of the same year, Emperor John VIII passed away. The potential successors to the throne were Constantine, Demetrios and Thomas. John had not formally designated and heir, though everyone knew he favored Constantine and ultimately, the will of their mother,

Among the actions taken during the brothers' project of strengthening the despotate was to reconstruct the Hexamilion wall, destroyed by the Turks in 1431. Together, they completely restored the wall, which was finished in March 1444. The wall was destroyed by the Turks again in 1446 after Constantine had attempted to expand his control northwards and had refused the sultan's demands of dismantling the wall. Constantine and Thomas were determined to hold the wall and had brought all their available forces, amounting to perhaps as many as twenty thousand men, to defend it. Despite this, the battle by the wall in 1446 was an overwhelming Turkish victory, with Constantine and Thomas barely escaping with their lives. Turahan Bey was sent south to take Mystras and devastate Constantine's lands while Sultan Murad II led his forces in the north of the Peloponnese. Although Turahan failed to take Mystras, this was of little consequence as Murad did not wish to conquer the Morea at the time, merely to instill terror, and the Turks soon left the peninsula, devastated and depopulated. Constantine and Thomas were in no position to ask for a truce and were forced to accept Murad as their lord and pay him tribute, promising to never again restore the Hexamilion wall.

Their former co-despot Theodore died in June 1448, and on 31 October of the same year, Emperor John VIII passed away. The potential successors to the throne were Constantine, Demetrios and Thomas. John had not formally designated and heir, though everyone knew he favored Constantine and ultimately, the will of their mother, Helena Dragaš

Helena Dragaš ( sr, Јелена Драгаш, ''Jelena Dragaš'', el, , ''Helénē Dragásē''; c. 1372 – 23 March 1450) was the empress consort of Byzantine emperor Manuel II Palaiologos and mother of the last two emperors, John VIII ...

(who also preferred Constantine), prevailed. Both Thomas, who had no intention of claiming the throne, and Demetrios, who most certainly did, hurried to Constantinople and reached the capital before Constantine. Though Demetrios was favored by many due to his anti-unionist sentiment, Helena reserved her right to act as regent until her eldest son, Constantine arrived, stalling Demetrios's attempt at seizing the throne. Thomas accepted Constantine's appointment and Demetrios, who soon thereafter joined in proclaiming Constantine as his new emperor, was overruled. Byzantine historian and Palaiologos loyalist George Sphrantzes

George Sphrantzes, also Phrantzes or Phrantza ( el, Γεώργιος Σφραντζής or Φραντζής; 1401 – c. 1478), was a late Roman (Byzantine) historian and Imperial courtier. He was an attendant to Emperor Manuel II Palaiologos, ''p ...

then informed Sultan Murad II, who also accepted the ascension of Constantine, now Emperor Constantine XI. In order to remove Demetrios from the capital and its vicinity, Constantine made Demetrios Despot of the Morea, to rule the despotate together with Thomas. Demetrios was granted Mystras and primarily ruled the southern and eastern parts of the despotate, with Thomas ruling Corinthia

Corinthia ( el, Κορινθία ''Korinthía'') is one of the regional units of Greece. It is part of the region of Peloponnese. It is situated around the city of Corinth, in the north-eastern part of the Peloponnese peninsula.

Geography

Cori ...

and the north-west, variously using Patras or Leontari as his capital.

In 1451, Sultan Murad II, by then old and tired and having let go of all intentions of conquering Constantinople, died and was succeeded as sultan by his young and vigorous son Mehmed II

Mehmed II ( ota, محمد ثانى, translit=Meḥmed-i s̱ānī; tr, II. Mehmed, ; 30 March 14323 May 1481), commonly known as Mehmed the Conqueror ( ota, ابو الفتح, Ebū'l-fetḥ, lit=the Father of Conquest, links=no; tr, Fâtih Su ...

, who was determined above all else to take the city. In 1452, during the preparation stages of the Ottoman siege of Constantinople, Constantine XI sent an urgent message to the Morea, requesting that one of his brothers bring their forces to help him defend the city. To prevent aid coming from the Morea, Mehmed II sent Turahan Bey to devastate the peninsula once more. The Turkish attack was repelled by an army commanded by Matthaios Asan

Matthew Palaiologos Asen ( el, Ματθαῖος Παλαιολόγος Ἀσάνης; died 29 March 1467) was a late Byzantine aristocrat and official, related to the Asen and Palaiologos dynasties.

Life

He was the son of Paul Asen, and brot ...

, brother-in-law of Demetrios, but this victory came too late to offer any aid to Constantinople.

Continued rule in the Morea

Initial tenure under Ottoman rule

fell

A fell (from Old Norse ''fell'', ''fjall'', "mountain"Falk and Torp (2006:161).) is a high and barren landscape feature, such as a mountain or Moorland, moor-covered hill. The term is most often employed in Fennoscandia, Iceland, the Isle o ...

on 29 May 1453, Constantine XI dying in its defense, ending the Byzantine Empire. In the aftermath of Constantinople's fall, and Constantine XI's death in defense of it, one of the most pressing threats to the new Ottoman regime was the possibility that one of Constantine XI's surviving relatives would find a following and return to reclaim the empire. Luckily for Mehmed II, the two despots in the Morea represented scarcely more than a nuisance and were allowed to keep their titles and lands. When emissaries of Thomas and Demetrios visited the Sultan at Adrianople some months after Constantinople's fall, the Sultan demanded no surrender of territory, only that the despots were to pay an annual tribute of 10,000 ducats. Because the Morea was allowed to continue to exist, many Byzantine refugees fled to the despotate, which made it somewhat of a Byzantine government-in-exile. Some of these influential refugees and courtiers even raised the idea of proclaiming Demetrios, the elder brother, as the Emperor of the Romans and the legitimate successor of Constantine XI. Both Thomas and Demetrios might have considered making their small despotate the rallying point of a campaign to restore the empire, with considerable fertile and wealthy territory under the despotate's control, there did seem for a moment to be a possibility that the empire could live on in the Morea. However, Thomas and Demetrios were never able to cooperate and spent most of their resources fighting each other rather than preparing for a struggle against the Turks. Since Thomas had spent most of his life in the Morea, and Demetrios most of his life elsewhere, the two brothers hardly knew each other.

Shortly after Constantinople fell, a revolt broke out against the despots in the Morea, prompted by the many Albanian immigrants to the region being unhappy with the actions of the local Greek landowners. The Albanians had respected earlier despots, such as Constantine and Theodore, but despised the two current despots and without central authority from Constantinople, they saw their opportunity to gain control of the despotate for themselves. In Thomas's part of the despotate, the rebels chose to proclaim John Asen Zaccaria John Asen Zaccaria or Asanes Zaccaria ( it, Giovanni Asano Zaccaria; died 1469) was the bastard son of the last Prince of Achaea, Centurione II Zaccaria (reigned 1404–1430). From 1446 on, he was kept imprisoned in the Chlemoutsi castle by the Byza ...

, bastard son of the last Prince of Achaea

The Prince of Achaea was the ruler of the Principality of Achaea, one of the crusader states founded in Greece in the aftermath of the Fourth Crusade (1202–1204). Though more or less autonomous, the principality was never a fully independent s ...

, as their leader and in Demetrios's part of the despotate, the leader of the revolt was Manuel Kantakouzenos

Manuel Kantakouzenos (or Cantacuzenus) ( Greek: Μανουήλ Καντακουζηνός, ''Manouēl Kantakouzēnos''), (c. 1326 – Mistra, Peloponnese, 10 April 1380). ''Despotēs'' in the Despotate of Morea or the Peloponnese from 25 Oct ...

, grandson of Demetrios I Kantakouzenos Demetrios I Kantakouzenos ( el, Δημήτριος Καντακουζηνός; 1343 – 1384) was a governor of the Morea and the grandson of Emperor John VI Kantakouzenos. Demetrios was the son of Matthew Kantakouzenos, governor of Morea, and I ...

(who had served as despot until 1384) and great-great-grandson of Emperor John VI Kantakouzenos

John VI Kantakouzenos or Cantacuzene ( el, , ''Iōánnēs Ángelos Palaiológos Kantakouzēnós''; la, Johannes Cantacuzenus; – 15 June 1383) was a Byzantine Greek nobleman, statesman, and general. He served as grand domestic under An ...

(1347–1354). With no hope of defeating the Albanians on their own, the despots appealed to the only power near enough and strong enough to aid them; the Ottomans. Mehmed II did not wish to see the despotate pass into the hands of Albanians, and out of his control, and sent an army to quell the rebellion in December 1453. The rebellion was not fully crushed until October 1454, when Turahan Bey arrived to aid the despots in firmly establishing their authority in the region. In return for the aid, Mehmed demanded a heavier tribute from Thomas and Demetrios, amounting to 12,000 ducats annually rather than the previous 10,000.

The possibility of Western aid

Pope Nicholas V

Pope Nicholas V ( la, Nicholaus V; it, Niccolò V; 13 November 1397 – 24 March 1455), born Tommaso Parentucelli, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 6 March 1447 until his death in March 1455. Pope Eugene IV, Po ...

issued the crusading bull

A crusade bull or crusading bull ( la, bulla cruciata) was a papal bull that granted privileges, including indulgences, to those who took part in the crusades against infidels.. A bull is an official document issued by a pope and sealed with a lea ...

''Etsi ecclesia Christi

''Etsi ecclesia Christi'' is a papal bull issued by Pope Nicholas V on 30 September 1453 in response to the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Empire.Norman Housley, ''Crusading and the Ottoman Threat, 1453–1505'' (Oxford: Oxford University ...

'', which called on Christians throughout the west to take the cross and embark on a crusade to recover Constantinople. The response was enthusiastic; some of Europe's most powerful and influential rulers came forward to take the cross, including Philip the Good

Philip III (french: Philippe le Bon; nl, Filips de Goede; 31 July 1396 – 15 June 1467) was Duke of Burgundy from 1419 until his death. He was a member of a cadet line of the Valois dynasty, to which all 15th-century kings of France belonge ...

of Burgundy in February 1454 and Alfonso the Magnanimous

Alfonso the Magnanimous (139627 June 1458) was King of Aragon and King of Sicily (as Alfonso V) and the ruler of the Crown of Aragon from 1416 and King of Naples (as Alfonso I) from 1442 until his death. He was involved with struggles to the t ...

of Aragon and Naples in November 1455. Alfonso promised to personally lead a host of 50,000 men and 400 ships against the Ottomans. At Frankfurt, Holy Roman Emperor Frederick III assembled a council of German princes and proposed that 40,000 men be sent to Hungary, where the Ottomans had suffered a crushing defeat at Belgrade in 1456. If the combined forces of Hungary, Aragon, Burgundy and the Holy Roman Empire had been unleashed to exploit the victory at Belgrade, Ottoman control of the Balkans would have been seriously threatened.

Despite the Ottomans having secured the position of the two despots in the recent Albanian uprising, the possibility of Western aid to restore Byzantine territory proved too enticing to resist. In 1456, Thomas sent John Argyropoulos

John Argyropoulos (/ˈd͡ʒɑn ˌɑɹd͡ʒɪˈɹɑ.pə.ləs/ el, Ἰωάννης Ἀργυρόπουλος ''Ioannis Argyropoulos''; it, Giovanni Argiropulo; surname also spelt ''Argyropulus'', or ''Argyropulos'', or ''Argyropulo''; c. 1415 – 2 ...

as an envoy to the West to discuss the possibility of aid for the Morea. Argyropolous had been a carefully thought-out choice since he had been an ardent supporter of the Council of Florence, which meant that he was well received by Pope Nicholas V's successor, Pope Callixtus III

Pope Callixtus III ( it, Callisto III, va, Calixt III, es, Calixto III; 31 December 1378 – 6 August 1458), born Alfonso de Borgia ( va, Alfons de Borja), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 8 April 1455 to his ...

, in Rome. From Rome, Argyropoulos also moved on to Milan, England and France and further envoys were sent to Aragon (because of Alfonso's involvement in the crusading plans) and Venice (since Thomas were hoping that he could secure refuge in Venetian territory in the event of an Ottoman attack on the Morea). A crusade seemed so imminent that even the decidedly anti-Western Demetrios softened his anti-Latin stance and sent envoys of his own. Argyropoulos probably arrived in Rome at around the same time as Demetrios's envoy, Frankoulios Servopoulos Frankoulios Servopoulos ( el, Φραγγούλιος Σερβόπουλος; ) was a Byzantine official in Constantinople and the Despotate of the Morea and an émigré to Italy.

Servopoulos is attested for the first time in 1442, being in the serv ...

, and the two envoys travelled through Europe, visiting the same courts, independently of each other. Thomas and Demetrios proved to be incapable of working together even with foreign diplomacy.

Moreot civil war and the fall of the Morea

In the end, no crusade ever set out to combat the Ottomans. Due to their conviction that help would arrive, and being unable to pay, the two despots had not paid their annual tribute to the Ottomans for three years. With no money coming from the Morea, and the looming threat of Western aid, Mehmed eventually lost his patience with the Palaiologoi. The Ottoman army marched from Adrianople in May 1458 and entered the Morea, where the only real resistance was faced at

In the end, no crusade ever set out to combat the Ottomans. Due to their conviction that help would arrive, and being unable to pay, the two despots had not paid their annual tribute to the Ottomans for three years. With no money coming from the Morea, and the looming threat of Western aid, Mehmed eventually lost his patience with the Palaiologoi. The Ottoman army marched from Adrianople in May 1458 and entered the Morea, where the only real resistance was faced at Corinth

Corinth ( ; el, Κόρινθος, Kórinthos, ) is the successor to an ancient city, and is a former municipality in Corinthia, Peloponnese, which is located in south-central Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform, it has been part o ...

, within the domain governed by Demetrios. Leaving his artillery to bombard and besiege that city, Mehmed left with most of his army to devastate and conquer the northern parts of the despotate, under Thomas's jurisdiction. Corinth at last gave up in August, after several cities in the north had already surrendered, and Mehmed imposed a heavy retribution on the Morea. The territory under the two brothers was drastically reduced, Corinth, Patras

)

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demographics1_title2 =

, demographics1_info2 =

, timezone1 = EET

, utc_offset1 = +2

, ...

and much of the north-west of the peninsula were annexed into the Ottoman Empire and provided with Turkish governors, with the Palaiologoi only being allowed to keep the south, including the despotate's nominal capital, Mystras, on the condition that they paid their annual tribute to the sultan.

Almost as soon as Mehmed had left the Morea, the two brothers began quarreling with each other again. Mehmed's victory had only increased the antagonism between Thomas and Demetrios. Demetrios had shifted to becoming even more pro-Ottoman after Mehmed had promised the despot that he would marry his daughter Helena, whereas Thomas increasingly hoped for western aid as the regions of the Morea annexed by Mehmed had been almost the entire area ruled by Thomas, including his capital of Patras. In January 1459, Thomas rebelled against Demetrios and the Ottomans, joining with a number of Albanian lords. They seized the fortress of Kalavryta and much of the land in the central Morea and besieged Kalamata

Kalamáta ( el, Καλαμάτα ) is the second most populous city of the Peloponnese peninsula, after Patras, in southern Greece and the largest city of the homonymous administrative region. As the capital and chief port of the Messenia reg ...

and Mantineia

Mantineia (also Mantinea ; el, Μαντίνεια; also Koine Greek ''Antigoneia'') was a city in ancient Arcadia, Greece, which was the site of two significant battles in Classical Greek history.

In modern times it is a former municipality in ...

, fortresses held by Demetrios. Demetrios responded by seizing Leontari and called for aid from the Turkish governors in the northern Morea. There were many attempts made to broker peace between the two brothers, such as Mehmed ordering the Bishop of Lacedaemon to make the two swear to keep the peace, but any truce lasted only briefly. Many of the Byzantine nobles in the Morea could only look on in horror as the civil war raged on. George Sphrantzes summed up the conflict with the following words:

Although Demetrios had more soldiers and resources, Thomas and the Albanians were able to appeal to the West for aid. After a successful skirmish against the Ottomans, Thomas sent 16 captured Turkish soldiers, alongside some of his armed guards, to Rome to convince the Pope that he was engaging in a holy war against the Muslims. The scheme worked and the Pope sent 300 Italian soldiers under the Milanese condottieri

''Condottieri'' (; singular ''condottiero'' or ''condottiere'') were Italian captains in command of mercenary companies during the Middle Ages and of multinational armies during the early modern period. They notably served popes and other Europ ...

Gianone da Cremona to aid Thomas. With these reinforcements, Thomas gained the upper hand and it looked as if Demetrios was about to be defeated, having retreated to the town of Monemvasia and having sent Matthaios Asan to Adrianople to beg Mehmed for aid. Thomas's pleas to the west represented a real threat to the Ottomans, a threat made even greater through the support of the plan by the vocal Cardinal Bessarion

Bessarion ( el, Βησσαρίων; 2 January 1403 – 18 November 1472) was a Byzantine Greek Renaissance humanist, theologian, Catholic cardinal and one of the famed Greek scholars who contributed to the so-called great revival of letters ...

, a Byzantine refugee who had escaped the empire years earlier. Pope Pius II

Pope Pius II ( la, Pius PP. II, it, Pio II), born Enea Silvio Bartolomeo Piccolomini ( la, Aeneas Silvius Bartholomeus, links=no; 18 October 1405 – 14 August 1464), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 19 August ...

convened a council in 1459 in Mantua

Mantua ( ; it, Mantova ; Lombard language, Lombard and la, Mantua) is a city and ''comune'' in Lombardy, Italy, and capital of the Province of Mantua, province of the same name.

In 2016, Mantua was designated as the Italian Capital of Culture ...

and sent Bessarion and some others to preach for a crusade against the Ottomans throughout Europe.

Determined to subjugate Greece, Mehmed decided that the destruction of the despotate and its full annexation directly into his empire was the only possible solution. The sultan assembled his army once more in April 1460 and led it in person first to Corinth and then on to Mystras. Although Demetrios had ostensibly been on the sultan's side, Mehmed invaded Demetrios's territory first. Demetrios surrendered to the Ottomans without a fight, fearing retribution and already having sent his family to safety in Monemvasia

Monemvasia ( el, Μονεμβασιά, Μονεμβασία, or ) is a town and municipality in Laconia, Greece. The town is located on a small island off the east coast of the Peloponnese, surrounded by the Myrtoan Sea. The island is connected t ...

. Mystras thus fell into Ottoman hands on 29 May 1460, exactly seven years after Constantinople's fall. The few places in the Morea that dared resist the sultan's army were devastated as per Islamic law, the men being massacred and the women and children being taken away. As large numbers of Greek refugees escaped to Venetian-held territories such as Methoni and Koroni

Koroni or Corone ( el, Κορώνη) is a town and a former Communities and Municipalities of Greece, municipality in Messenia, Peloponnese (region), Peloponnese, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Pylos ...

, the Morea was slowly subdued, the last resistance being led by Constantine Graitzas Palaiologos, a relative of Thomas and Demetrios, at Salmenikon in July 1461.

Life in exile

When Thomas had first heard of Mehmed's invasion, he had initially taken refuge at

When Thomas had first heard of Mehmed's invasion, he had initially taken refuge at Mantineia

Mantineia (also Mantinea ; el, Μαντίνεια; also Koine Greek ''Antigoneia'') was a city in ancient Arcadia, Greece, which was the site of two significant battles in Classical Greek history.

In modern times it is a former municipality in ...

to wait and see how the invasion unfolded. Once it became clear that the Ottomans were marching towards Leontari and would soon arrive outside Mantineia, Thomas, his entourage (including other Greek nobles, such as George Sphrantzes), his wife Catherine and his children Andreas

Andreas ( el, Ἀνδρέας) is a name usually given to males in Austria, Greece, Cyprus, Denmark, Armenia, Estonia, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Finland, Flanders

Flanders (, ; Dutch: ''Vlaanderen'' ) is the Flemish-speaking northern portion of B ...

, Manuel and Zoe fled to Methoni. Thomas and his companions fled to the island of Corfu

Corfu (, ) or Kerkyra ( el, Κέρκυρα, Kérkyra, , ; ; la, Corcyra.) is a Greek island in the Ionian Sea, of the Ionian Islands, and, including its small satellite islands, forms the margin of the northwestern frontier of Greece. The isl ...

on ships provided by Venice, arriving there on 22 July 1460. Although Catherine and the children stayed on Corfu, the island was only a temporary refuge for Thomas, and the local government was unwilling to allow him to stay for too long in fear of antagonizing the Ottomans. Thomas was unsure of where to travel to next, he attempted to travel to Ragusa Ragusa is the historical name of Dubrovnik. It may also refer to:

Places Croatia

* the Republic of Ragusa (or Republic of Dubrovnik), the maritime city-state of Ragusa

* Cavtat (historically ' in Italian), a town in Dubrovnik-Neretva County, Cro ...

, but the city's senate firmly rejected his arrival. Around the same time, Mehmed II sent messengers to Thomas to implore him to enter into a "treaty of friendship", promising him lands in return for his return to Greece. Unsure of what to do, Thomas sent emissaries to both Mehmed and the Papacy (to tell the Pope of his predicament). The envoy to Mehmed found the sultan at Veria

Veria ( el, Βέροια or Βέρροια), officially transliterated Veroia, historically also spelled Berea or Berœa, is a city in Central Macedonia, in the geographic region of Macedonia, northern Greece, capital of the regional unit of I ...

and was, despite the sultan's words, immediately arrested and put in chains along with his entourage.

A few days later the envoy was set free and returned to Thomas at Corfu with a message; either Thomas was to come to Mehmed in person, or he was to send some of his children. In light of this, Thomas decided that he had no choice; the West was his only option. On 16 November 1460, he left his wife and children behind on Corfu and set sail for Italy, landing in Ancona

Ancona (, also , ) is a city and a seaport in the Marche region in central Italy, with a population of around 101,997 . Ancona is the capital of the province of Ancona and of the region. The city is located northeast of Rome, on the Adriatic S ...

. In March 1461, Thomas arrived in Rome, where he hoped to convince Pope Pius II to call for a crusade. As the brother of the final Byzantine emperor, Thomas was the highest profile ruler in exile out of all the many Christians who escaped the Balkans over the course of the Ottoman conquest.

Upon arriving in Rome, Thomas met with Pius II, who bestowed him with the Golden Rose

The Golden Rose is a gold ornament, which popes of the Catholic Church have traditionally blessed annually. It is occasionally conferred as a token of reverence or affection. Recipients have included churches and sanctuaries, royalty, military ...

, lodging in the Ospedale di Santo Spirito in Sassia

The Hospital of the Holy Spirit ( it, L'Ospedale di Santo Spirito in Sassia) is the oldest hospital in Europe, located in Rome, Italy. It now serves as a convention center. The complex lies in rione Borgo, east of Vatican City and next to the mo ...

and a pension of 300 ducat

The ducat () coin was used as a trade coin in Europe from the later Middle Ages from the 13th to 19th centuries. Its most familiar version, the gold ducat or sequin containing around of 98.6% fine gold, originated in Venice in 1284 and gained wi ...

s each month (for a total of 3600 annually). In addition to the papal pension, Thomas also received an additional 200 ducats a month from the cardinals and 500 ducats from the Republic of Venice, which also begged him not to return to Corfu as to not affect Venice's already tenuous relations with the Ottomans. Thomas's many followers considered the money provided to him to be barely enough to support the despot, and certainly nowhere near enough to also support themselves. The Papacy recognized Thomas as the rightful Despot of the Morea and the true heir to the Byzantine Empire, though Thomas never claimed the imperial title.

Saint Paul

Paul; grc, Παῦλος, translit=Paulos; cop, ⲡⲁⲩⲗⲟⲥ; hbo, פאולוס השליח (previously called Saul of Tarsus;; ar, بولس الطرسوسي; grc, Σαῦλος Ταρσεύς, Saũlos Tarseús; tr, Tarsuslu Pavlus; ...

which to this day stands in front of the St. Peter's Basilica

The Papal Basilica of Saint Peter in the Vatican ( it, Basilica Papale di San Pietro in Vaticano), or simply Saint Peter's Basilica ( la, Basilica Sancti Petri), is a church built in the Renaissance style located in Vatican City, the papal e ...

. On 12 April 1462, Thomas gave the supposed skull of Saint Andrew the Apostle

Andrew the Apostle ( grc-koi, Ἀνδρέᾱς, Andréās ; la, Andrēās ; , syc, ܐܰܢܕ݁ܪܶܐܘܳܣ, ʾAnd’reʾwās), also called Saint Andrew, was an Apostles in the New Testament, apostle of Jesus according to the New Testament. He ...

, a precious relic which had been in Byzantine hands for centuries, to Pius II. Pius received the skull from Cardinal Bessarion at the Ponte Milvio

The Milvian (or Mulvian) Bridge ( it, Ponte Milvio or ; la, Pons Milvius or ) is a bridge over the Tiber in northern Rome, Italy. It was an economically and strategically important bridge in the era of the Roman Empire and was the site of the f ...

. The ceremony, which was hailed as a return of Andrew to his relatives, the Romans (as symbolic descendants of Saint Peter

Saint Peter; he, שמעון בר יונה, Šimʿōn bar Yōnāh; ar, سِمعَان بُطرُس, translit=Simʿa̅n Buṭrus; grc-gre, Πέτρος, Petros; cop, Ⲡⲉⲧⲣⲟⲥ, Petros; lat, Petrus; ar, شمعون الصفـا, Sham'un ...

) is depicted on Pius II's grave.

In the 1460s, plans for a crusade against the Ottomans were once more underway. Pius II had made the recovery of Constantinople one of the primary goals of his pontificate and his 1459 council at Mantua had secured the promise of an army amounting to a total of 80,000 men from various of the great powers in Western Europe. Naval support for the plans was secured in 1463, when Venice formally declared war on the Ottomans as a result of Turkish incursions into their territories in Greece. In October 1463, Pius II formally declared war on the Ottoman Empire after Mehmed had refused his suggestion of converting to Christianity. While many of the Balkan exiles in the West were happy to live out their lives in obscurity, Thomas hoped to eventually restore control over Byzantine territory. As such, he staunchly supported the crusading plans.

In early 1462, Thomas left to Rome to tour Italy and drum up support for a crusade, carrying with him papal letters of indulgence

In the teaching of the Catholic Church, an indulgence (, from , 'permit') is "a way to reduce the amount of punishment one has to undergo for sins". The '' Catechism of the Catholic Church'' describes an indulgence as "a remission before God o ...

. Thomas brought with him letters by Pius II who described him as "a prince who was born to the illustrious and ancient family of the Palaiologoi ... a man who is now an immigrant, naked, robbed of everything except his lineage". Like his father Manuel II and his brother John VIII before him, Thomas's possessed a certain royal charisma and good looks, which ensured that his appeals did not fall on deaf ears. The Mantuan ambassador to Rome described him as "a handsome man with a fine, serious look about him and a noble and quite lordly bearing" and Milanese ambassadors who encountered him in Venice wrote that Thomas was "as dignified as any man on Earth can be". Of the many courts Thomas visited, serious objections to his appeal was made only by Venice, where the local senate made it clear that they wanted nothing to do with him. Not only did they make Thomas leave the city, but they sent ambassadors to Rome to request that he not accompany the expedition because his presence would "produce terrible and incongrous scandals". The reason for Venice's wrath against Thomas might be his advances on Venetian territories during his time as despot, or the fact that his quarreling with his brother Demetrios effectively doomed the Morean despotate. Despite Thomas's hopes, no expedition sat out for Greece. When the army was ready to set sail in 1464, Pius II travelled to Ancona to join the crusade, but died there on 15 August. Without Pius II's leadership, the crusade disbanded almost immediately, with all the ships returning home one by one.

Upon the death of his wife in August 1462, Thomas summoned his children (who still remained at Corfu) to Rome, but they only arrived in the city after Thomas had died on 12 May 1465. Though Thomas had been largely bypassed and forgotten by the Roman elite after Pius II's death in 1464, he was buried with honor in the St. Peter's Basilica, where his grave would survive the destruction and removal of the tombs of the Palaiologan emperors in Constantinople during the early years of Ottoman rule. Modern efforts to locate his grave within the Basilica have so far proven fruitless.

Children and descendants

It is generally accepted that Thomas had four children with Catherine Zaccaria, due to George Sphrantzes giving this number. These four children were:

*

It is generally accepted that Thomas had four children with Catherine Zaccaria, due to George Sphrantzes giving this number. These four children were:

* Helena Palaiologina

Helena Palaiologina ( el, ; 3 February 1428 – 11 April 1458) was a Byzantine princess of the Palaiologos family, who became Queen of Cyprus and Armenia, titular Queen consort of Jerusalem, and Princess of Antioch through her marriage to King ...

(1431 – 7 November 1473), the older of the couple's two daughters, Helena was married to Lazar Branković

Lazar Branković ( sr-cyr, Лазар Бранковић; c. 1421 – 20 February 1458) was a Serbian despot, prince of Rascia from 1456 to 1458. He was the third son of Đurađ Branković and his wife Eirene Kantakouzene. He was succeeded by hi ...

, a son of Đurađ Branković

Đurađ Branković (; sr-cyr, Ђурађ Бранковић; hu, Brankovics György; 1377 – 24 December 1456) was the Serbian Despot from 1427 to 1456. He was one of the last Serbian medieval rulers. He was a participant in the battle of Anka ...

, Despot of Serbia. By the time of the Morea's fall, Helena had long since moved to Smederevo

Smederevo ( sr-Cyrl, Смедерево, ) is a city and the administrative center of the Podunavlje District in eastern Serbia. It is situated on the right bank of the Danube, about downstream of the Serbian capital, Belgrade.

According to ...

with her husband (who eventually became the Despot of Serbia in 1456). Lazar died in 1458 and Helena was left to care for the couple's three daughters. In 1459, Mehmed II invaded Serbia and put an end to the despotate, but Helena was allowed to leave the country. After spending some time in Ragusa Ragusa is the historical name of Dubrovnik. It may also refer to:

Places Croatia

* the Republic of Ragusa (or Republic of Dubrovnik), the maritime city-state of Ragusa

* Cavtat (historically ' in Italian), a town in Dubrovnik-Neretva County, Cro ...

, she moved to Corfu and lived there with her mother and siblings. After that, Helena became a nun and lived on the island of Lefkada

Lefkada ( el, Λευκάδα, ''Lefkáda'', ), also known as Lefkas or Leukas ( Ancient Greek and Katharevousa: Λευκάς, ''Leukás'', modern pronunciation ''Lefkás'') and Leucadia, is a Greek island in the Ionian Sea on the west coast of G ...

, where she died in November 1473. Though Helena had many descendants through her three daughters Jelena Jelena, also written Yelena and Elena, is a Slavic given name. It is a Slavicized form of the Greek name Helen, which is of uncertain origin. Diminutives of the name include Jelica, Jelka, Jele, Jela, Lena, Lenotschka, Jeca, Lenka, and Alena.

Not ...

, Milica

Milica ( sr-Cyrl, Милица; pronounced 'Millitsa') is a feminine name popular in Balkan countries. It is a diminutive form of the given name Mila, meaning 'kind', 'dear' or 'sweet'. The name was used for a number of queens and princesses, inc ...

and Jerina Brankovic, none of them carried on the Palaiologos name.

* Zoe Palaiologina

Zoe Palaiologina ( grc-x-byzant, Ζωή Παλαιολογίνα), whose name was later changed to Sophia Palaiologina (russian: София Фоминична Палеолог; ca. 1449 – 7 April 1503), was a Byzantine princess, member of ...

( 1449 – 7 April 1503), the younger daughter of Thomas and Catherine, Zoe was married off to Ivan III, Grand Prince of Moscow, by Pope Sixtus IV

Pope Sixtus IV ( it, Sisto IV: 21 July 1414 – 12 August 1484), born Francesco della Rovere, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 9 August 1471 to his death in August 1484. His accomplishments as pope include ...

in 1472, in the hope of converting the Russians to Roman Catholicism. The Russians did not convert, with the marriage being celebrated according to Eastern Orthodox tradition. Zoe was called "Sophia" in Russia and her marriage to Ivan III served to strengthen Moscow's claim to be the "Third Rome

The continuation, succession and revival of the Roman Empire is a running theme of the history of Europe and the Mediterranean Basin. It reflects the lasting memories of power and prestige associated with the Roman Empire itself.

Several polit ...

", the ideological and spiritual successor to the Byzantine Empire. Zoe and Ivan III had several children, who in turn had numerous descendants and though none carried the Palaiologos name, many of them used the double-headed eagle

In heraldry and vexillology, the double-headed eagle (or double-eagle) is a charge (heraldry), charge associated with the concept of Empire. Most modern uses of the symbol are directly or indirectly associated with its use by the late Byzantin ...

iconography of Byzantium. The famous Ivan the Terrible

Ivan IV Vasilyevich (russian: Ива́н Васи́льевич; 25 August 1530 – ), commonly known in English as Ivan the Terrible, was the grand prince of Moscow from 1533 to 1547 and the first Tsar of all Russia from 1547 to 1584.

Ivan ...

, Russia's first Tsar

Tsar ( or ), also spelled ''czar'', ''tzar'', or ''csar'', is a title used by East Slavs, East and South Slavs, South Slavic monarchs. The term is derived from the Latin word ''Caesar (title), caesar'', which was intended to mean "emperor" i ...

, was Sophia's grandson.

*Andreas Palaiologos

Andreas Palaiologos or Palaeologus ( el, Ἀνδρέας Παλαιολόγος; 17 January 1453 – June 1502), sometimes anglicized to Andrew, was the eldest son of Thomas Palaiologos, Despot of the Morea. Thomas was a brother of Constantine& ...

(17 January 1453 – June 1502), the older of the couple's two sons and the third child overall, Andreas lived most of his life in Rome, surviving on a gradually declining papal pension. After Thomas's death, Andreas was recognized by the Papacy and others in Italy as the rightful heir to the Despotate of the Morea and he would later go on to claim the title ''Imperator Constantinopolitanus'' ("Emperor of Constantinople") as well, hoping to one day restore the fallen Byzantine Empire. He attempted to organize an expedition to restore the empire in 1481, but his plans failed and he later ceded the rights to the imperial title to Charles VIII of France

Charles VIII, called the Affable (french: l'Affable; 30 June 1470 – 7 April 1498), was King of France from 1483 to his death in 1498. He succeeded his father Louis XI at the age of 13.Paul Murray Kendall, ''Louis XI: The Universal Spider'' (Ne ...

, hoping to use him as a champion against the Turks. Andreas died poor in Rome, whether or not he had any children is uncertain. His will specified that his titles were to be granted to the Catholic Monarchs

The Catholic Monarchs were Queen Isabella I of Castile and King Ferdinand II of Aragon, whose marriage and joint rule marked the ''de facto'' unification of Spain. They were both from the House of Trastámara and were second cousins, being bot ...

in Spain (though they never used them).

* Manuel Palaiologos

Manuel Palaiologos or Palaeologus ( el, Μανουήλ Παλαιολόγος, translit=Manouēl Palaiologos; 2 January 1455 – before 1513) was the youngest son of Thomas Palaiologos, a brother of Constantine XI Palaiologos, the final Byzantine ...

(2 January 1455 – before 1512), the youngest of the four children, Manuel lived in Rome and lived off Papal money, much the same as his brother. As the pension deteriorated and Manuel (as second-in-line) did not have any titles to sell, he instead travelled Europe in search of someone to hire him in a military capacity. Failing to find satisfactory offers, Manuel surprised everyone else involved by travelling to Constantinople in 1476 and throwing himself on the mercy of Sultan Mehmed II, who graciously received him. He married an unknown woman and stayed in Constantinople for the rest of his life. Manuel had two sons, one of which died young and another which converted to Islam and whose eventual fate is uncertain.

Sphrantzes may not have been well acquainted with Thomas's family. He gives the age of Thomas's wife at time of her death as 70, which means that she would have given birth to Manuel at the unlikely age of 65. It is known that Thomas had at least one child who is not mentioned by Sphrantzes; a daughter (whose name is unknown) who died in infancy, recorded in a funeral oration. Later sources other than the work of Sphrantzes differ considerably in the number of children ascribed to Thomas. Whereas some, such as Charles du Fresne

Charles du Fresne, sieur du Cange (; December 18, 1610 in Amiens – October 23, 1688 in Paris, aged 77), also known simply as Charles Dufresne, was a distinguished French philologist and historian of the Middle Ages and Byzantium.

Life

Educat ...

(1680), give the same four children mentioned by Sphrantzes, others, such as Antonio Albizzi

Antonio is a masculine given name of Etruscan origin deriving from the root name Antonius. It is a common name among Romance language-speaking populations as well as the Balkans and Lusophone Africa. It has been among the top 400 most popular male ...

(1627) give only two children (the sons Andreas and Manuel). Leo Allatius (1648) gives three sons (John, Andreas and Manuel). This means that even a relatively short time after Thomas's death, the number of children he had was unclear.

Genealogist Peter Mallat concluded in 1985 that this uncertainty, as well as the fact that Thomas's eldest known child, Helena, was born almost twenty years before his second eldest known child, Zoe, as meaning that it is possible that Thomas had more children than the generally accepted four. Some later Italian genealogies dating to the 17th century and onwards give Thomas two more sons; a bastard son named Rogerio and a fourth legitimate son, also named Thomas. The existence of Rogerio and Thomas the Younger is overwhelmingly dismissed as fantasy in modern scholarship. There is some scant evidence of the existence of a second Thomas Palaiologos in the 15th century as a "Thomas Palaiologos, Despot of the Morea" is recorded as having married a sister of Queen Isabella of Clermont

Isabella of Clermont ( – 30 March 1465), also known as Isabella of Taranto, was queen of Naples as the first wife of King Ferdinand I of Naples, and a feudatory of the kingdom as the holder and ruling Princess of the Principality of Taranto in ...

in 1444 (something Thomas could not have done as he was married at the time and ruling in the Morea). Rogerio's existence is based on a handful of unauthenticated documents and the oral tradition of his supposed descendants, the "Paleologo Mastrogiovanni". Though the individual documents themselves have little questionable content, they are contradictory when examined as a whole and do not necessarily corroborate Thomas having a son by the name Rogerio. Sphrantzes wrote on the birth of Andreas Palaiologos on 17 January 1453 that the boy was "a continuator and heir" of the Palaiologan lineage, a phrase which makes little sense if Andreas was not Thomas's first-born son (if they would have existed, both Rogerio and Thomas the Younger would have been older than Andreas).

In the late 16th century, a family with the last name Paleologus

The House of Palaiologos ( Palaiologoi; grc-gre, Παλαιολόγος, pl. , female version Palaiologina; grc-gre, Παλαιολογίνα), also found in English-language literature as Palaeologus or Palaeologue, was a Byzantine Greeks, ...

, living in Pesaro

Pesaro () is a city and ''comune'' in the Italian region of Marche, capital of the Province of Pesaro e Urbino, on the Adriatic Sea. According to the 2011 census, its population was 95,011, making it the second most populous city in the Marche, ...

in Italy, claimed descent from Thomas through a supposed third son, called John. This family later mainly lived in Cornwall

Cornwall (; kw, Kernow ) is a historic county and ceremonial county in South West England. It is recognised as one of the Celtic nations, and is the homeland of the Cornish people. Cornwall is bordered to the north and west by the Atlantic ...

and contained figures such as Theodore Paleologus

Theodore Paleologus ( it, Teodoro Paleologo; – 21 January 1636) was a 16th and 17th-century Italian nobleman, soldier and assassin. According to the genealogy presented on Theodore's tombstone, he was a direct male-line descendant of the Pala ...

, who worked as a soldier and hired assassin, and Ferdinand Paleologus, who retired in Barbados in the late 17th century. The existence of a son of Thomas called John cannot be proven with any certainty as no mention is made of a son by that name in contemporary records. It is possible that John was a real historical figure, possibly an illegitimate son of Thomas, or perhaps his grandson through of either of his known sons, Andreas or Manuel. John's existence could be corroborated by the mention of a son by this name by Allatius in 1648 (though this is too late to act as an independent source) and contemporary documents in Pesaro discussing a Leone Palaiologos (the names Leone and John are similar in their Latin forms; ''Leonis'' and ''Ioannes'') as living there.

See also

* Succession to the Byzantine EmpireReferences

Citations

Cited bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Palaiologos, Thomas 1409 births 1465 deaths 15th-century Byzantine emperors 15th-century Despots of the Morea Burials at St. Peter's Basilica Byzantine people of the Byzantine–Ottoman wars Byzantine pretenders after 1453 Converts to Roman Catholicism from Eastern OrthodoxyThomas

Thomas may refer to:

People

* List of people with given name Thomas

* Thomas (name)

* Thomas (surname)

* Saint Thomas (disambiguation)

* Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) Italian Dominican friar, philosopher, and Doctor of the Church

* Thomas the A ...

Former Greek Orthodox Christians

Greek Roman Catholics

Thomas

Thomas may refer to:

People

* List of people with given name Thomas

* Thomas (name)

* Thomas (surname)

* Saint Thomas (disambiguation)

* Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) Italian Dominican friar, philosopher, and Doctor of the Church

* Thomas the A ...

Porphyrogennetoi

Sons of Byzantine emperors