Name

Documents from the 17th century variously render the spelling of Tisquantum's name as ''Tisquantum'', ''Tasquantum'', and ''Tusquantum'', and alternately call him ''Squanto'', ''Squantum'', ''Tantum'', and ''Tantam''. Even the two ''Mayflower'' settlers who dealt with him closely spelled his name differently; Bradford nicknamed him "Squanto", while Edward Winslow invariably referred to him as ''Tisquantum'', which historians believe was his proper name. One suggestion of the meaning is that it is derived from the Algonquian expression for ''the rage of theEarly life

Almost nothing is known of Tisquantum's life before his first contact with Europeans, and even when and how that first encounter took place is subject to contradictory assertions. First-hand descriptions of him written between 1618 and 1622 do not remark on his youth or old age, and Salisbury has suggested that he was in his twenties or thirties when he was captured and taken to Spain in 1614. If that was the case, he would have been born around 1585 (±10 years).Native culture

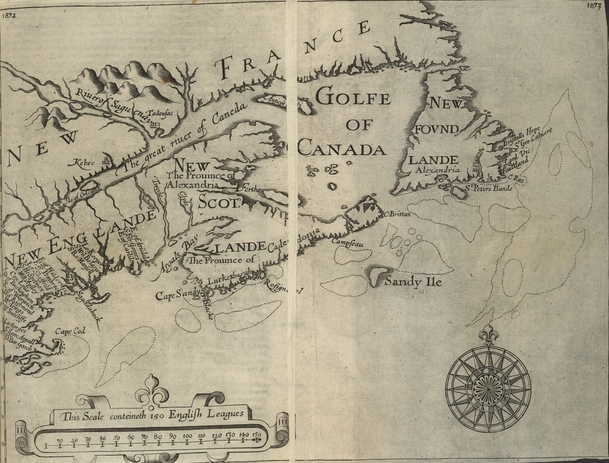

The tribes who lived in southern New England at the beginning of the 17th century referred to themselves as ''

The tribes who lived in southern New England at the beginning of the 17th century referred to themselves as ''Contact with Europeans

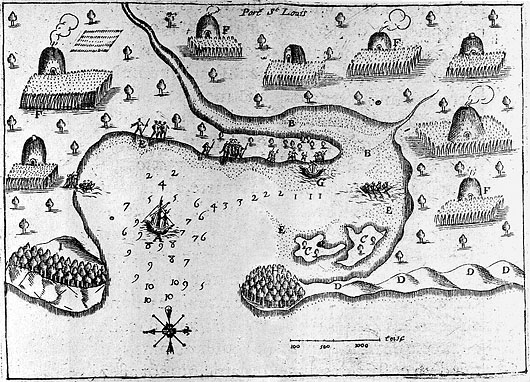

The Ninnimissinuok had sporadic contact with European explorers for nearly a century before the landing of the ''Mayflower'' in 1620. The fishermen off the Newfoundland banks fromThe first kidnappings

In 1605, George Weymouth set out on an expedition to explore the possibility of settlement in upper New England, sponsored by Henry Wriothesley and Thomas Arundell. They had a chance encounter with a hunting party, then decided to kidnap a number of Indians. The capture of Indians was "a matter of great importance for the full accomplement of our voyage".

They took five captives to England and gave three to Sir

In 1605, George Weymouth set out on an expedition to explore the possibility of settlement in upper New England, sponsored by Henry Wriothesley and Thomas Arundell. They had a chance encounter with a hunting party, then decided to kidnap a number of Indians. The capture of Indians was "a matter of great importance for the full accomplement of our voyage".

They took five captives to England and gave three to Sir Captain George Weymouth, having failed at finding aCircumstantial evidence makes nearly impossible the claim that it was Tisquantum among the three taken by Gorges. Adams maintains that "it is not supposable that a member of the Pokánoket tribe would be passing the summer of 1605 in a visit among his deadly enemies the Tarratines, whose language was not even intelligible to him ... and be captured as one of a party of them in the way described by Rosier," and no modern historian entertains this as fact.Northwest Passage The Northwest Passage (NWP) is the sea route between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans through the Arctic Ocean, along the northern coast of North America via waterways through the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. The eastern route along the Arct ..., happened into a River on the Coast of ''America'', called ''Pemmaquid'', from whence he brought five of the Natives, three of whose names were ''Manida'', ''Sellwarroes'', and ''Tasquantum'', whom I seized upon, they were all of one Nation, but of severall parts, and severall Families; This accident must be acknowledged the meanes under God of putting on foote, and giving life to all our Plantations.

Abduction

In 1614, an English expedition headed by John Smith sailed along the coast of Maine and Massachusetts Bay collecting fish and furs. Smith returned to England in one of the vessels and left Thomas Hunt in command of the second ship. Hunt was to complete the haul of cod and proceed to

In 1614, an English expedition headed by John Smith sailed along the coast of Maine and Massachusetts Bay collecting fish and furs. Smith returned to England in one of the vessels and left Thomas Hunt in command of the second ship. Hunt was to complete the haul of cod and proceed to  According to Gorges, Hunt took the Indians to the

According to Gorges, Hunt took the Indians to the Return to New England

According to the report by the Toward the end of 1619, Dermer and Tisquantum sailed down the New England coast to Massachusetts Bay. They discovered that all inhabitants had died in Tisquantum's home village at Patucket, so they moved inland to the village of Nemasket. Dermer sent Tisquantum to the village of Pokanoket near

Toward the end of 1619, Dermer and Tisquantum sailed down the New England coast to Massachusetts Bay. They discovered that all inhabitants had died in Tisquantum's home village at Patucket, so they moved inland to the village of Nemasket. Dermer sent Tisquantum to the village of Pokanoket near Plymouth Colony

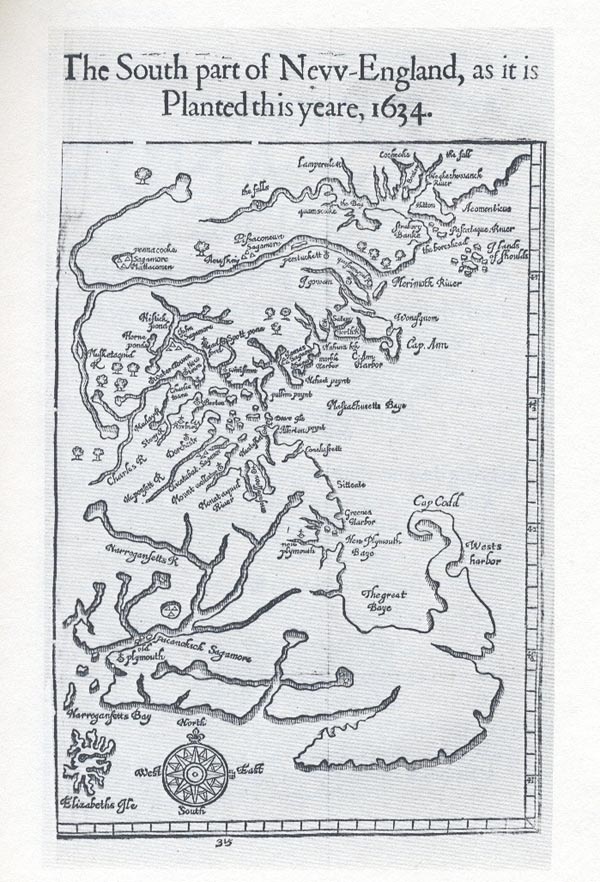

The Massachusett Indians were north of Plymouth Colony, led by Chief Massasoit, and the Pokanoket tribe were north, east, and south. Tisquantum was living with the Pokanokets, as his native tribe of the Patuxets had been effectively wiped out prior to the arrival of the ''Mayflower''; indeed, the Pilgrims had established the Patuxets former habitation as the site of Plymouth Colony. The Narragansett tribe inhabited Rhode Island.

Massasoit was faced with the dilemma whether to form an alliance with the Plymouth colonists, who might protect him from the Narragansetts, or try to put together a tribal coalition to drive out the colonists. To decide the issue, according to Bradford's account, "they got all the Powachs of the country, for three days together in a horrid and devilish manner, to curse and execrate them with their conjurations, which assembly and service they held in a dark and dismal swamp." Philbrick sees this as a convocation of shamans brought together to drive the colonists from the shores by supernatural means. Tisquantum had lived in England, and he told Massassoit "what wonders he had seen" there. He urged Massasoit to become friends with the Plymouth colonists, because his enemies would then be "Constrained to bowe to him". Also connected to Massasoit was

The Massachusett Indians were north of Plymouth Colony, led by Chief Massasoit, and the Pokanoket tribe were north, east, and south. Tisquantum was living with the Pokanokets, as his native tribe of the Patuxets had been effectively wiped out prior to the arrival of the ''Mayflower''; indeed, the Pilgrims had established the Patuxets former habitation as the site of Plymouth Colony. The Narragansett tribe inhabited Rhode Island.

Massasoit was faced with the dilemma whether to form an alliance with the Plymouth colonists, who might protect him from the Narragansetts, or try to put together a tribal coalition to drive out the colonists. To decide the issue, according to Bradford's account, "they got all the Powachs of the country, for three days together in a horrid and devilish manner, to curse and execrate them with their conjurations, which assembly and service they held in a dark and dismal swamp." Philbrick sees this as a convocation of shamans brought together to drive the colonists from the shores by supernatural means. Tisquantum had lived in England, and he told Massassoit "what wonders he had seen" there. He urged Massasoit to become friends with the Plymouth colonists, because his enemies would then be "Constrained to bowe to him". Also connected to Massasoit was Guide to frontier survival

Massasoit and his men left the day after the treaty, but Samoset and Tisquantum remained. Tisquantum and Bradford developed a close friendship, and Bradford relied on him heavily during his years as governor of the colony. Bradford considered him "a special instrument sent of God for their good beyond their expectation".''OPP'': and . Tisquantum instructed them in survival skills and acquainted them with their environment. "He directed them how to set their corn, where to take fish, and to procure other commodities, and was also their pilot to bring them to unknown places for their profit, and never left them till he died." The day after Massasoit left Plymouth, Tisquantum spent the day at Eel River treading eels out of the mud with his feet. The bucketful of eels he brought back were "fat and sweet". Collection of eels became part of the settlers' annual practice. But Bradford makes special mention of Tisquantum's instruction concerning local horticulture. He had arrived at the time of planting for that year's crops, and Bradford said that "Squanto stood them in great stead, showing them both the manner how to set it, and after how to dress and tend it." Bradford wrote that Sqanto showed them how to fertilize exhausted soil:He told them, except they got fish and set with it orn seedin these old grounds it would come to nothing. And he showed them that in the middle of April they should have store enough f fishcome up the brook by which they began to build, and taught them how to take it, and where to get other provisions necessary for them. All of which they found true by trial and experience.Edward Winslow made the same point about the value of Indian cultivation methods in a letter to England at the end of the year:

We set the last Spring some twentie Acres of ''Indian'' Corne, and sowed some six Acres of Barly and Pease; and according to the manner of the ''Indians'', we manured our ground with Herings or rather Shadds, which we have in great abundance, and take with great ease at our doores. Our Corn did prove well, & God be praysed, we had a good increase of ''Indian''-Corne, and our Barly indifferent good, but our Pease were not worth the gathering, for we feared they were too late sowne.The method shown by Tisquantum became the regular practice of the settlers. Tisquantum also showed the Plymouth colonists how they could obtain pelts with the "few trifling commodities they brought with them at first". Bradford reported that there was not "any amongst them that ever saw a beaver skin till they came here and were informed by Squanto". Fur trading became an important way for the colonists to pay off their financial debt to their financial sponsors in England.

Role in settler diplomacy

Thomas Morton stated that Massasoit was freed as a result of the peace treaty and "suffered isquantumto live with the English", and Tisquantum remained loyal to the colonists. One commentator has suggested that the loneliness occasioned by the wholesale extinction of his people was the motive for his attachment to the Plymouth settlers. Another has suggested that it was self-interest that he conceived while in the captivity of the Pokanoket. The settlers were forced to rely on Tisquantum because he was the only means by which they could communicate with the surrounding Indians, and he was involved in every contact for the 20 months that he lived with them.Mission to Pokanoket

Plymouth Colony decided in June that a mission to Massasoit in Pokatoket would enhance their security and reduce visits by Indians who drained their food resources. Winslow wrote that they wanted to ensure that the peace treaty was still valued by the Pokanoket and to reconnoiter the surrounding country and the strength of the various tribes. They also hoped to show their willingness to repay the grain that they took on Cape Cod the previous winter, in the words of Winslow to "make satisfaction for some conceived injuries to be done on our parts".Mission to the Nauset

Winslow writes that young John Billington had wandered off and had not returned for five days. Bradford sent word to Massasoit, who made inquiry and found that the child had wandered into a Manumett village, who turned him over to the Nausets. Ten settlers set out and took Tisquantum as a translator and Tokamahamon as "a special friend," in Winslow's words. They sailed toAction to save Tisquantum in Nemasket

The men returned to Plymouth after rescuing the Billington boy, and it was confirmed to them that Massasoit had been ousted or taken by the Narragansetts. They also learned thatMission to the Massachuset people

The Plymouth colonists resolved to meet with the Massachusetts Indians who had frequently threatened them. On August 18, a crew of ten settlers set off around midnight, with Tisquantum and two other Indians as interpreters, hoping to arrive before daybreak. But they misjudged the distance and were forced to anchor off shore and stay in the shallop over the next night. Once ashore, they found a woman coming to collect the trapped lobsters, and she told them where the villagers were. Tisquantum was sent to make contact, and they discovered that the sachem presided over a considerably reduced band of followers. His name was Obbatinewat, and he was a tributary of Massasoit. He explained that his current location within Boston harbor was not a permanent residence since he moved regularly to avoid the Tarentines and the ''Squa Sachim'' (the widow of On Friday, September 21, the colonists went ashore and marched a house where Nanepashemet was buried. They remained there and sent Tisquantum and another Indian to find the people. There were signs of hurried removal, but they found the women together with their corn and later a man who was brought trembling to the settlers. They assured him that they did not intend harm, and he agreed to trade furs with them. Tisquantum urged the colonists to simply "rifle" the women and take their skins on the ground, that "they are a bad people and oft threatned you," but the colonists insisted on treating them fairly. The women followed the men to the shallop, selling them everything that they had, including the coats off their backs. As the colonists shipped off, they noticed that the many islands in the harbor had been inhabited, some cleared entirely, but all the inhabitants had died. They returned with "a good quantity of beaver", but the men who had seen Boston Harbor expressed their regret that they had not settled there.

On Friday, September 21, the colonists went ashore and marched a house where Nanepashemet was buried. They remained there and sent Tisquantum and another Indian to find the people. There were signs of hurried removal, but they found the women together with their corn and later a man who was brought trembling to the settlers. They assured him that they did not intend harm, and he agreed to trade furs with them. Tisquantum urged the colonists to simply "rifle" the women and take their skins on the ground, that "they are a bad people and oft threatned you," but the colonists insisted on treating them fairly. The women followed the men to the shallop, selling them everything that they had, including the coats off their backs. As the colonists shipped off, they noticed that the many islands in the harbor had been inhabited, some cleared entirely, but all the inhabitants had died. They returned with "a good quantity of beaver", but the men who had seen Boston Harbor expressed their regret that they had not settled there.

Peace regime

During the fall of 1621 the Plymouth settlers had every reason to be contented with their condition, less than one year after the "starving times". Bradford expressed the sentiment with biblical allusion that they found "the Lord to be with them in all their ways, and to bless their outgoings and incomings ..." Winslow was more prosaic when he reviewed the political situation with respect to surrounding natives in December 1621: "Wee have found the ''Indians'' very faithfull in their Covenant of Peace with us; very loving and readie to pleasure us ...," not only the greatest, Massasoit, "but also all the Princes and peoples round about us" for fifty miles. Even a sachem from Martha's Vineyard, who they never saw, and also seven others came in to submit to King James "so that there is now great peace amongst the ''Indians'' themselves, which was not formerly, neither would have bin but for us ..."Thanksgiving

Bradford wrote in his journal that come fall together with their harvest of Indian corn, they had abundant fish and fowl, including many turkeys they took in addition to venison. He affirmed that the reports of plenty that many report "to their friends in England" were not "feigned but true reports". He did not, however, describe any harvest festival with their native allies. Winslow, however, did, and the letter which was included in ''Mourt's Relation'' became the basis for the tradition of "the first Thanksgiving". Winslow's description of what was later celebrated as the first Thanksgiving was quite short. He wrote that after the harvest (of Indian corn, their planting of peas were not worth gathering and their harvest of barley was "indifferent"), Bradford sent out four men fowling "so we might after a more special manner rejoice together, after we had gathered the fruit of our labours ..." The time was one of recreation, including the shooting of arms, and many Natives joined them, including Massasoit and 90 of his men, who stayed three days. They killed five deer which they presented to Bradford, Standish and others in Plymouth. Winslow concluded his description by telling his readers that "we are so farre from want, that we often wish you partakers of our plentie."The Narragansett threat

The various treaties created a system where the English settlers filled the vacuum created by the epidemic. The villages and tribal networks surrounding Plymouth now saw themselves as tributaries to the English and (as they were assured) King James. The settlers also viewed the treaties as committing the Natives to a form of vassalage. Nathaniel Morton, Bradford's nephew, interpreted the original treaty with Massasoit, for example, as "at the same time" (not within the written treaty terms) acknowledging himeself "content to become the Subject of our Sovereign Lord the King aforesaid, His Heirs and Successors, and gave unto them all the Lands adjacent, to them and their Heirs for ever". The problem with this political and commercial system was that it "incurred the resentment of the Narragansett by depriving them of tributaries just when Dutch traders were expanding their activities in the arragansettbay". In January 1622 the Narraganset responded by issuing an ultimatum to the English. In December 1621 the ''Fortune'' (which had brought 35 more settlers) had departed for England. Not long afterwards rumors began to reach Plymouth that the Narragansett were making warlike preparations against the English. Winslow believed that that nation had learned that the new settlers brought neither arms nor provisions and thus in fact weakened the English colony. Bradford saw their belligerency as a result of their desire to "lord it over" the peoples who had been weakened by the epidemic (and presumably obtain tribute from them) and the colonists were "a bar in their way". In January 1621/22 a messenger from Narraganset sachem Canonicus (who travelled with Tokamahamon, Winslow's "special friend") arrived looking for Tisquantum, who was away from the settlement. Winslow wrote that the messenger appeared relieved and left a bundle of arrows wrapped in a rattlesnake skin. Rather than let him depart, however, Bradford committed him to the custody of Standish. The captain asked Winslow, who had a "speciall familiaritie" with other Indians, to see if he could get anything out of the messenger. The messenger would not be specific but said that he believed "they were enemies to us." That night Winslow and another (probably Hopkins) took charge of him. After his fear subsided, the messenger told him that the messenger who had come from Canonicus last summer to treat for peace, returned and persuaded the sachem on war. Canonicus was particularly aggrieved by the "meannesse" of the gifts sent him by the English, not only in relation to what he sent to colonists but also in light of his own greatness. On obtaining this information, Bradford ordered the messenger released.

When Tisquantum returned he explained that the meaning of the arrows wrapped in snake skin was enmity; it was a challenge. After consultation, Bradford stuffed the snake skin with powder and shot and had a Native return it to Canonicus with a defiant message. Winslow wrote that the returned emblem so terrified Canonicus that he refused to touch it, and that it passed from hand to hand until, by a circuitous route, it was returned to Plymouth.

In December 1621 the ''Fortune'' (which had brought 35 more settlers) had departed for England. Not long afterwards rumors began to reach Plymouth that the Narragansett were making warlike preparations against the English. Winslow believed that that nation had learned that the new settlers brought neither arms nor provisions and thus in fact weakened the English colony. Bradford saw their belligerency as a result of their desire to "lord it over" the peoples who had been weakened by the epidemic (and presumably obtain tribute from them) and the colonists were "a bar in their way". In January 1621/22 a messenger from Narraganset sachem Canonicus (who travelled with Tokamahamon, Winslow's "special friend") arrived looking for Tisquantum, who was away from the settlement. Winslow wrote that the messenger appeared relieved and left a bundle of arrows wrapped in a rattlesnake skin. Rather than let him depart, however, Bradford committed him to the custody of Standish. The captain asked Winslow, who had a "speciall familiaritie" with other Indians, to see if he could get anything out of the messenger. The messenger would not be specific but said that he believed "they were enemies to us." That night Winslow and another (probably Hopkins) took charge of him. After his fear subsided, the messenger told him that the messenger who had come from Canonicus last summer to treat for peace, returned and persuaded the sachem on war. Canonicus was particularly aggrieved by the "meannesse" of the gifts sent him by the English, not only in relation to what he sent to colonists but also in light of his own greatness. On obtaining this information, Bradford ordered the messenger released.

When Tisquantum returned he explained that the meaning of the arrows wrapped in snake skin was enmity; it was a challenge. After consultation, Bradford stuffed the snake skin with powder and shot and had a Native return it to Canonicus with a defiant message. Winslow wrote that the returned emblem so terrified Canonicus that he refused to touch it, and that it passed from hand to hand until, by a circuitous route, it was returned to Plymouth.

Double dealing

Notwithstanding the colonists' bold response to the Narragansett challenge, the settlers realized their defenselessness to attack. Bradford instituted a series of measures to secure Plymouth. Most important they decided to enclose the settlement within a pale (probably much like what was discovered surrounding Nenepashemet's fort). They shut the inhabitants within gates that were locked at night, and a night guard was posted. Standish divided the men into four squadrons and drilled them in where to report in the event of alarm. They also came up with a plan of how to respond to fire alarms so as to have a sufficient armed force to respond to possible Native treachery. The fence around the settlement required the most effort since it required felling suitable large trees, digging holes deep enough to support the large timbers and securing them close enough to each other to prevent penetration by arrows. This work had to be done in the winter and at a time too when the settlers were on half rations because of the new and unexpected settlers. The work took more than a month to complete.False alarms

By the beginning of March, the fortification of the settlement had been accomplished. It was now time when the settlers had promised the Massachuset they would come to trade for furs. They received another alarm however, this time from Hobomok, who was still living with them. Hobomok told of his fear that the Massachuset had joined in a confederacy with the Narraganset and if Standish and his men went there, they would be cut off and at the same time the Narraganset would attack the settlement at Plymouth. Hobomok also told them that Tisquantum was part of this conspiracy, that he learned this from other Natives he met in the woods and that the settlers would find this out when Tisquantum would urge the settlers into the Native houses "for their better advantage". This allegation must have come as a shock to the English given that Tisquantum's conduct for nearly a year seemed to have aligned him perfectly with the English interest both in helping to pacify surrounding societies and in obtaining goods that could be used to reduce their debt to the settlers' financial sponsors. Bradford consulted with his advisors, and they concluded that they had to make the mission despite this information. The decision was made partly for strategic reasons. If the colonists cancelled the promised trip out of fear and instead stayed shut up "in our new-enclosed towne", they might encourage even more aggression. But the main reason they had to make the trip was that their "Store was almost emptie" and without the corn they could obtain by trading "we could not long subsist ..." The governor therefore deputed Standish and 10 men to make the trip and sent along both Tisquantum and Hobomok, given "the jealousy between them".''OPP'': and . Not long after the shallop departed, "an Indian belonging to Squanto's family" came running in. He betrayed signs of great fear, constantly looking behind him as if someone "were at his heels". He was taken to Bradford to whom he told that many of the Narraganset together with Corbitant "and he thought Massasoit" were about to attack Plymouth. Winslow (who was not there but wrote closer to the time of the incident than did Bradford) gave even more graphic details: The Native's face was covered in fresh blood which he explained was a wound he received when he tried speaking up for the settlers. In this account he said that the combined forces were already at Nemasket and were set on taking advantage of the opportunity supplied by Standish's absence. Bradford immediately put the settlement on military readiness and had the ordnance discharge three rounds in the hope that the shallop had not gone too far. Because of calm seas Standish and his men had just reached Gurnet's Nose, heard the alarm and quickly returned. When Hobomok first heard the news he "said flatly that it was false ..." Not only was he assured of Massasoit's faithfulness, he knew that his being a ''pniese'' meant he would have been consulted by Massasoit before he undertook such a scheme. To make further sure Hobomok volunteered his wife to return to Pokanoket to assess the situation for herself. At the same time Bradford had the watch maintained all that night, but there were no signs of Natives, hostile or otherwise. Hobomok's wife found the village of Pokanoket quiet with no signs of war preparations. She then informed Massasoit of the commotion at Plymouth. The sachem was "much offended at the carriage of Tisquantum" but was grateful for Bradford's trust in him assasoit He also sent word back that he would send word to the governor, pursuant to the first article of the treaty they had entered, if any hostile actions were preparing.Allegations against Tisquantum

Winslow writes that "by degrees wee began to discover ''Tisquantum''," but he does not describe the means or over what period of time this discovery took place. There apparently was no formal proceeding. The conclusion reached, according to Winslow, was that Tisquantum had been using his proximity and apparent influence over the English settlers "to make himselfe great in the eyes of" local Natives for his own benefit. Winslow explains that Tisquantum convinced locals that he had the ability to influence the English toward peace or war and that he frequently extorted Natives by claiming that the settlers were about to kill them in order "that thereby hee might get gifts to himself to work their peace ..." Bradford's account agrees with Winslow's to this point, and he also explains where the information came from: "by the former passages, and other things of like nature", evidently referring to rumors Hobomok said he heard in the woods. Winslow goes much further in his charge, however, claiming that Tisquantum intended to sabotage the peace with Massasoit by false claims of Massasoit aggression "hoping whilest things were hot in the heat of bloud, to provoke us to march into his Country against him, whereby he hoped to kindle such a flame as would not easily be quenched, and hoping if that blocke were once removed, there were no other betweene him and honour" which he preferred over life and peace. Winslow later remembered "one notable (though) wicked practice of this ''Tisquantum''"; namely, that he told the locals that the English possessed the "plague" buried under their storehouse and that they could unleash it at will. What he referred to was their cache of gunpowder.Massasoit's demand for Tisquantum

Captain Standish and his men eventually did go to the Massachuset and returned with a "good store of Trade". On their return, they saw that Massasoit was there and he was displaying his anger against Tisquantum. Bradford did his best to appease him, and he eventually departed. Not long afterward, however, he sent a messenger demanding that Tisquantum be put to death. Bradford responded that although Tisquantum "deserved to die both in respect of him assasoitand us", but said that Tisquantum was too useful to the settlers because otherwise, he had no one to translate. Not long afterward, the same messenger returned, this time with "divers others", demanding Tisquantum. They argued that Tisquantum being a subject of Massasoit, was subject, pursuant to the first article of the Peace Treaty, to the sachem's demand, in effect, rendition. They further argued that if Bradford would not produce pursuant to the Treaty, Massasoit had sent many beavers' skins to induce his consent. Finally, if Bradford still would not release him to them, the messenger had brought Massasoit's own knife by which Bradford himself could cut off Tisquantum's head and hands to be returned with the messenger. Bradford avoided the question of Massasoit's right under the treaty but refused the beaver pelts saying that "It was not the manner of the ''English'' to sell men's lives at a price ..." The governor called Tisquantum (who had promised not to flee), who denied the charges and ascribed them to Hobomok's desire for his downfall. He nonetheless offered to abide by Bradford's decision. Bradford was "ready to deliver him into the hands of his Executioners" but at that instance, a boat passed before the town in the harbor. Fearing that it might be the French, Bradford said he had to first identify the ship before dealing with the demand. The messenger and his companions, however, "mad with rage, and impatient at delay" left "in great heat".Final mission with the settlers

Arrival of the ''Sparrow''

The ship the English saw pass before the town was not French, but rather a shallop from the ''Sparrow'', a shipping vessel sponsored by Thomas Weston and one other of the Plymouth settlement's sponsors, which was plying the eastern fishing grounds. This boat brought seven additional settlers but no provisions whatsoever "nor any hope of any". In a letter they brought, Weston explained that the settlers were to set up a salt pan operation on one of the islands in the harbor for the private account of Weston. He asked the Plymouth colony, however, to house and feed these newcomers, provide them with seed stock and (ironically) salt, until he was able to send the salt pan to them. The Plymouth settlers had spent the winter and spring on half rations in order to feed the settlers that had been sent nine months ago without provisions. Now Weston was exhorting them to support new settlers who were not even sent to help the plantation. He also announced that he would be sending another ship that would discharge more passengers before it would sail on to Virginia. He requested that the settlers entertain them in their houses so that they could go out and cut down timber to lade the ship quickly so as not to delay its departure. Bradford found the whole business "but cold comfort to fill their hungry bellies". Bradford was not exaggerating. Winslow described the dire straits. They now were without bread "the want whereof much abated the strength and the flesh of some, and swelled others". Without hooks or seines or netting, they could not collect the bass in the rivers and cove, and without tackle and navigation rope, they could not fish for the abundant cod in the sea. Had it not been for shellfish which they could catch by hand, they would have perished. But there was more, Weston also informed them that the London backers had decided to dissolve the venture. Weston urged the settlers to ratify the decision; only then might the London merchants send them further support, although what motivation they would then have he did not explain. That boat also, evidently, contained alarming news from the South. John Huddleston, who was unknown to them but captained a fishing ship that had returned from Virginia to the Maine fishing grounds, advised his "good friends at Plymouth" of the massacre in the Jamestown settlements by the Powhatan in which he said 400 had been killed. He warned them: "Happy is he whom other men's harms doth make to beware." This last communication Bradford decided to turn to their advantage. Sending a return for this kindness, they might also seek fish or other provisions from the fishermen. Winslow and a crew were selected to make the voyage to Maine, 150 miles away, to a place they had never been. In Winslow's reckoning, he left at the end of May for Damariscove. Winslow found the fishermen more than sympathetic and they freely gave what they could. Even though this was not as much as Winslow hoped, it was enough to keep them going until the harvest. When Winslow returned, the threat they felt had to be addressed. The general anxiety aroused by Huddleston's letter was heightened by the increasingly hostile taunts they learned of. Surrounding villagers were "glorying in our weaknesse", and the English heard threats about how "easie it would be ere long to cut us off". Even Massasoit turned cool towards the English, and could not be counted on to tamp down this rising hostility. So they decided to build a fort on burying hill in town. And just as they did when building the palisade, the men had to cut down trees, haul them from the forest and up the hill and construct the fortified building, all with inadequate nutrition and at the neglect of dressing their crops.Weston's English settlers

They might have thought they reached the end of their problems, but in June 1622 the settlers saw two more vessels arrive, carrying 60 additional mouths to feed. These were the passengers that Weston had written would be unloaded from the vessel going on to Virginia. That vessel also carried more distressing news. Weston informed the governor that he was no longer a part of the company sponsoring the Plymouth settlement. The settlers he sent just now, and requested the Plymouth settlement to house and feed, were for his own enterprise. The "sixty lusty men" would not work for the benefit of Plymouth; in fact he had obtained a patent and as soon as they were ready they would settle an area in Massachusetts Bay. Other letters also were brought. The other venturers in London explained that they had bought out Weston, and everyone was better off without him. Weston, who saw the letter before it was sent, advised the settlers to break off from the remaining merchants, and as a sign of good faith delivered a quantity of bread and cod to them. (Although, as Bradford noted in the margin, he "left not his own men a bite of bread.") The arrivals also brought news that the ''Fortune'' had been taken by French pirates, and therefore all their past effort to export American cargo (valued at £500) would count for nothing. Finally Robert Cushman sent a letter advising that Weston's men "are no men for us; wherefore I prey you entertain them not"; he also advised the Plymouth Separatists not to trade with them or loan them anything except on strict collateral."I fear these people will hardly deal so well with the savages as they should. I pray you therefore signify to Squanto that they are a distinct body from us, and we have nothing to do with them, neither must be blamed for their faults, much less can warrant their fidelity." As much as all this vexed the governor, Bradford took in the men and fed and housed them as he did the others sent to him, even though Weston's men would compete with his colony for pelts and other Native trade. But the words of Cushman would prove prophetic. Weston's men, "stout knaves" in the words of Thomas Morton, were roustabouts collected for adventure and they scandalized the mostly strictly religious villagers of Plymouth. Worse, they stole the colony's corn, wandering into the fields and snatching the green ears for themselves. When caught, they were "well whipped", but hunger drove them to steal "by night and day". The harvest again proved disappointing, so that it appeared that "famine must still ensue, the next year also" for lack of seed. And they could not even trade for staples because their supply of items the Natives sought had been exhausted. Part of their cares were lessened when their coasters returned from scouting places in Weston's patent and took Weston's men (except for the sick, who remained) to the site they selected for settlement, called Wessagusset (now Weymouth). But not long after, even there they plagued Plymouth, who heard, from Natives once friendly with them, that Weston's settlers were stealing their corn and committing other abuses. At the end of August a fortuitous event staved off another starving winter: the ''Discovery'', bound for London, arrived from a coasting expedition from Virginia. The ship had a cargo of knives, beads and other items prized by Natives, but seeing the desperation of the colonists the captain drove a hard bargain: He required them to buy a large lot, charged them double their price and valued their beaver pelts at 3s. per pound, which he could sell at 20s. "Yet they were glad of the occasion and fain to buy at any price ..."

Weston's men, "stout knaves" in the words of Thomas Morton, were roustabouts collected for adventure and they scandalized the mostly strictly religious villagers of Plymouth. Worse, they stole the colony's corn, wandering into the fields and snatching the green ears for themselves. When caught, they were "well whipped", but hunger drove them to steal "by night and day". The harvest again proved disappointing, so that it appeared that "famine must still ensue, the next year also" for lack of seed. And they could not even trade for staples because their supply of items the Natives sought had been exhausted. Part of their cares were lessened when their coasters returned from scouting places in Weston's patent and took Weston's men (except for the sick, who remained) to the site they selected for settlement, called Wessagusset (now Weymouth). But not long after, even there they plagued Plymouth, who heard, from Natives once friendly with them, that Weston's settlers were stealing their corn and committing other abuses. At the end of August a fortuitous event staved off another starving winter: the ''Discovery'', bound for London, arrived from a coasting expedition from Virginia. The ship had a cargo of knives, beads and other items prized by Natives, but seeing the desperation of the colonists the captain drove a hard bargain: He required them to buy a large lot, charged them double their price and valued their beaver pelts at 3s. per pound, which he could sell at 20s. "Yet they were glad of the occasion and fain to buy at any price ..."

Trading expedition with Weston's men

The ''Charity'' returned from Virginia at the end of September–beginning of October. It proceeded on to England, leaving the Wessagusset settlers well provisioned. The ''Swan'' was left for their use as well. It was not long after they learned that the Plymouth settlers had acquired a store of trading goods that they wrote Bradford proposing that they jointly undertake a trading expedition, they to supply the use of the ''Swan.'' They proposed equal division of the proceeds with payment for their share of the goods traded to await arrival of Weston. (Bradford assumed they had burned through their provisions.) Bradford agreed and proposed an expedition southward of the Cape. Winslow wrote that Tisquantum and Massasoit had "wrought" a peace (although he doesn't explain how this came about). With Tisquantum as guide, they might find the passage among theDeath

The sickness seems to have greatly shaken Bradford, for they lingered there for several days before he died. Bradford described his death in some detail:In this place Tisquantum fell sick of Indian fever, bleeding much at the nose (which the Indians take as a symptom of death) and within a few days died there; desiring the Governor to pray for him, that he might go to the Englishmen's God in Heaven; and bequeathed sundry of his things to English friends, as remembrances of his love; of whom they had a great loss.''OPP'': and .Without Tisquantum to pilot them, the English settlers decided against trying the shoals again and returned to Cape Cod Bay. The English Separatists were comforted by the fact that Tisquantum had become a Christian convert. William Wood writing a little more than a decade later explained why some of the Ninnimissinuok began recognizing the power of "the ''Englishmens'' God, as they call him": "because they could never yet have power by their conjurations to damnifie the ''English'' either in body or goods" and since the introduction of the new spirit "the times and seasons being much altered in seven or eight years, freer from lightning and thunder, and long droughts, suddaine and tempestuous dashes of rain, and lamentable cold Winters". Philbrick speculates that Tisquantum may have been poisoned by Massasoit. His bases for the claim are (i) that other Native Americans had engaged in assassinations during the 17th century; and (ii) that Massasoit's own son,

Assessment, memorials, representations, and folklore

Historical assessment

Because almost all the historical records of Tisquantum were written by English Separatists and because most of that writing had the purpose to attract new settlers, give account of their actions to their financial sponsors or to justify themselves to co-religionists, they tended to relegate Tisquantum (or any other Native American) to the role of assistant to them in their activities. No real attempt was made to understand Tisquantum or Native culture, particularly religion. The closest that Bradford got in analyzing him was to say "that Tisquantum sought his own ends and played his own game, ... to enrich himself". But in the end, he gave "sundry of his things to sundry of his English friends". Historians' assessment of Tisquantum depended on the extent they were willing to consider the possible biases or motivations of the writers. Earlier writers tended to take the colonists' statements at face value. Current writers, especially those familiar with ethnohistorical research, have given a more nuanced view of Tisquantum, among other Native Americans. As a result, the assessment of historians has run the gamut. Adams characterized him as "a notable illustration of the innate childishness of the Indian character". By contrast, Shuffelton says he "in his own way, was quite as sophisticated as his English friends, and he was one of the most widely traveled men in the New England of his time, having visited Spain, England, and Newfoundland, as well as a large expanse of his own region." Early Plymouth historian Judge John Davis, more than a half century before, also saw Tisquantum as a "child of nature", but was willing to grant him some usefulness to the enterprise: "With some aberrations, his conduct was generally irreproachable, and his useful services to the infant settlement, entitle him to grateful remembrance." In the middle of the 20th century Adolf was much harder on the character of Tisquantum ("his attempt to aggrandize himself by playing the Whites and Indians against each other indicates an unsavory facet of his personality") but gave him more importance (without him "the founding and development of Plymouth would have been much more difficult, if not impossible."). Most have followed the line that Baylies early took of acknowledging the alleged duplicity and also the significant contribution to the settlers' survival: "Although Squanto had discovered some traits of duplicity, yet his loss was justly deemed a public misfortune, as he had rendered the English much service."Memorials and landmarks

As for monuments and memorials, although many (as Willison put it) "clutter up the Pilgrim towns there is none to Squanto..." The first settlers may have named after him the peninsula called Squantum once in Dorchester, now in Quincy, during their first expedition there with Tisquantum as their guide. Thomas Morton refers to a place called "Squanto's Chappell", but this is probably another name for the peninsula.Literature and popular entertainment

Tisquantum rarely makes appearances in literature or popular entertainment. Of all the 19th century New England poets and story tellers who drew on pre-Revolution America for their characters, only one seems to have mentioned Tisquantum. And whileDidactic literature and folklore

Where Tisquantum is most encountered is in literature designed to instruct children and young people, provide inspiration, or guide them to a patriotic or religious truth. This came about for two reasons. First, Lincoln's establishment of Thanksgiving as a national holiday enshrined the New England Anglo-Saxon festival, vaguely associated with an American strain of Protestantism, as something of a national origins myth, in the middle of a divisive Civil War when even some Unionists were becoming concerned with rising non-Anglo-Saxon immigration. This coincided, as Ceci noted, with the "noble savage" movement, which was "rooted in romantic reconstructions of Indians (for example, ''Hiawatha'') as uncorrupted natural beings—who were becoming extinct—in contrast to rising industrial and urban mobs". She points to the Indian Head coin first struck in 1859 "to commemorate their passing.'" Even though there was only the briefest mention of "Thanksgiving" in the Plymouth settlers' writings, and despite the fact that he was not mentioned as being present (although, living with the settlers, he likely was), Tisquantum was the focus around both myths could be wrapped. He is, or at least a fictionalized portrayal of him, thus a favorite of a certain politically conservative American Protestant groups. The story of the selfless "noble savage" who patiently guided and occasionally saved the "Pilgrims" (to whom he was subservient and who attributed their good fortune solely to their faith, all celebrated during a bounteous festival) was thought to be an enchanting figure for children and young adults. Beginning early in the 20th century Tisquantum entered high school textbooks, children's read-aloud and self-reading books, more recently learn-to-read and coloring books and children's religious inspiration books. Over time and particularly depending on the didactic purpose, these books have greatly fictionalized what little historical evidence remains of Tisquantum's life. Their portraits of Tisquantum's life and times spans the gamut of accuracy. Those intending to teach a moral lesson or tell history from a religious viewpoint tend to be the least accurate even when they claim to be telling a true historical story. Recently there have been attempts to tell the story as accurately as possible, without reducing Tisquantum to a mere servant of the English. There have even been attempts to place the story in the social and historical context of fur trade, epidemics and land disputes. Almost none, however, have dealt with Tisquantum's life after "Thanksgiving" (except occasionally the story of the rescue of John Billington). An exception to all of that is the publication of a "young adult" version of Philbrick's best-selling adult history. Nevertheless, given the sources which can be drawn on, Tisquantum's story inevitably is seen from the European perspective.Notes, references and sources

Notes

References

Sources

Primary

* The book was first published in . An annotated version is contained in . * * This is the modern critical edition of the manuscript by William Bradford entitled simply '' Of plimouth plantation''. In the notes and references the manuscript (as opposed to the printed versions) is sometimes referred to as ''OPP''. The first book of the manuscript had been copied into Plymouth church records by Nathaniel Morton, Bradford's nephew and secretary, and it was this version that was annotated and printed in , the original at a time having been missing since the beginning of theInternet Archive

When the manuscript was returned to Massachusetts at the end of the 19th century, the Massachusetts legislature commissioned a new transcription to be published. While the version that resulted was more faithful to the idiosyncratic orthography of Bradford, it contained, according to Morison, many of the same mistakes as the transcription published in 1856. The legislature's version was published in 1898. A copy is hosted by th

Internet Archive

That version was the basis of the annotated version published as The 1982 Barnes & Noble reprint of this edition can be found online a

HathiTrust

A digitized version with most of Davis's annotations and notes removed is hosted a

the University of Maryland's Early Americas Digital Archive

The most amply annotated and literrally transcribed edition of the work is . The history of the manuscript is described in the Editorial Preface to the 1856 publication by the Massachusetts Historical Society and more fully in the Introduction of Morison's edition (pp. xxvii–xl), which also contains a history of the published editions of the manuscript (pp. xl–xliii). * A facsimile reprint with introduction by Luther S. Livingston and published by Dodd, Mead & Co. in 1903 is hosted by th

Internet Archive

A digitized version (with page numbers) is also hosted by th

University of Michigan

An annotated version can also be found in . * * Hosted by Internet Archives

Volume I

1567–35 (1880)

Volume II

1604–1610 (1878)

Volume III

1611–1618 (1882). * Repinted in * * (Reprint of 1674 manuscript.) * Published under the authorship of "

Volume I

an

Volume II

* A facsimile reproduction is contained in An early annotated edition is This book is largely based on the manuscript ''Of Plymouth Plantation'' by William Bradford, Morton's uncle. * , an annotated version of which, retaining the original orthography, is contained, together with introductory matter and notes, in * This work (the authors of which are not credited) is commonly called ''

HathiTrust

A version with contemporary orthography and comments was published in connection with the Plimouth Plantation, Inc. as * * The original imprint was "In fower parts, each containing five bookes". All four volumes (parts) are hosted online by th

Library of Congress

The 1905–07 reproduction was printed in 20 volumves (one for each "book"): * The pamphlet was reprinted in an 1877 edition hosted online b

HathiTrust

It is reprinted with annotations at . * This book is reprinted in . A digitized version can be downloaded fro

The Digital Commons at University of Nebraska–Lincoln

* * . Macmillan published a verbatim version of the first printing (with different pagination) of this work as well as Smith's 1630 autobiography and his ''Sea Grammar'': The Macmillan version, is hosted by the Library of Congress in two volumes)

Volume I

an

Volume II

A searchable version (with various download options) of the same book is hosted by the Internet Archive

Voume I

an

Volume II

The ''Generall History of Virginia'' is also contained in . The work was twice republished in Smith's life (in 1726 and 1727) and immediately after his death (in 1732). * * * A digitized version with modern typeface but 1643 pagination is hosted by th

University of Michigan

* The work is reprinted, with annotations, in . * A facsimile reproduction, with original pagination, is printed in an 1865 edition, together with a new preface and one from a 1764 reprinting, by The Society of Boston and hosted by th

Internet Archive

Secondary

* Online (via HathiTrust)("The Settlement of Boston Bay" is found in Volume 1, pp. 1–360. The chapter on Tisquantum is found at pp. 23–44.) * * Hosted online by the Internet Archive

Volume I

an

Volume II

* * * * In three volumes, online, at the Internet Archive, as follows

Volume 1

consists of Baxter's memoir of Sir Ferdinando Gorges and ''A briefe relation of the discovery and plantation of New England ...'' (London: J. Haviland for W. Bladen, 1622)

Volume 2

includes ''A briefe narration of the original undertakings of the advancement of plantation into the parts of American... by ... Sir Ferdinando Gorges ...'' (London: E. Brudenell, for N. Brook, 1658) as well as other works of Gorges and his son Thomas Gorges

Volume 3

is devoted to Gorges's letters and other papers, 1596–1646. * * * * * * (The work consists of first-hand accounts of early voyages to the New World, with introduction and notes by Burrage.) * * * * * * * * * * * (A copy is also hosted by th

HathiTrust

) * * * * * Hosted by the Internet Archive in two volumes

Volume I

an

Voume II

* * The work is in two volumes hosted on the Internet Archive a

Volume I

an

Volume II

* (William C. Sturtevant, general editor.) * * * * (This essay was originally a lecture delivered before the Lowell Institute, January 29, 1869.) * * * First of three volumes. * * * * * * * * * The work is hosted on the Internet Archive

Volume 1

an

Volume II

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * (William C. Sturtevant, general editor.) * * * * * * * * * * * This is a reprint of an article by the same name published in ''Johns Hopkins Hospital Bulletin''. 20 (224): 340–49 (November 1909). * * * Da Capo published a facsimile reprinting of this volume in 1971.

External links

Modern History Sourcebook: William Bradford: ''from'' History of Plymouth Plantation, c. 1650 · Treaty with the Indians 1621

{{DEFAULTSORT:Tisquantum Wampanoag people American folklore Burials in Massachusetts Native Americans connected with Plymouth Colony Plymouth, Massachusetts 1622 deaths 17th-century American slaves 16th-century births 17th-century Native Americans Native American history of Massachusetts Native American people from Massachusetts