Thomas Fitch (politician) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

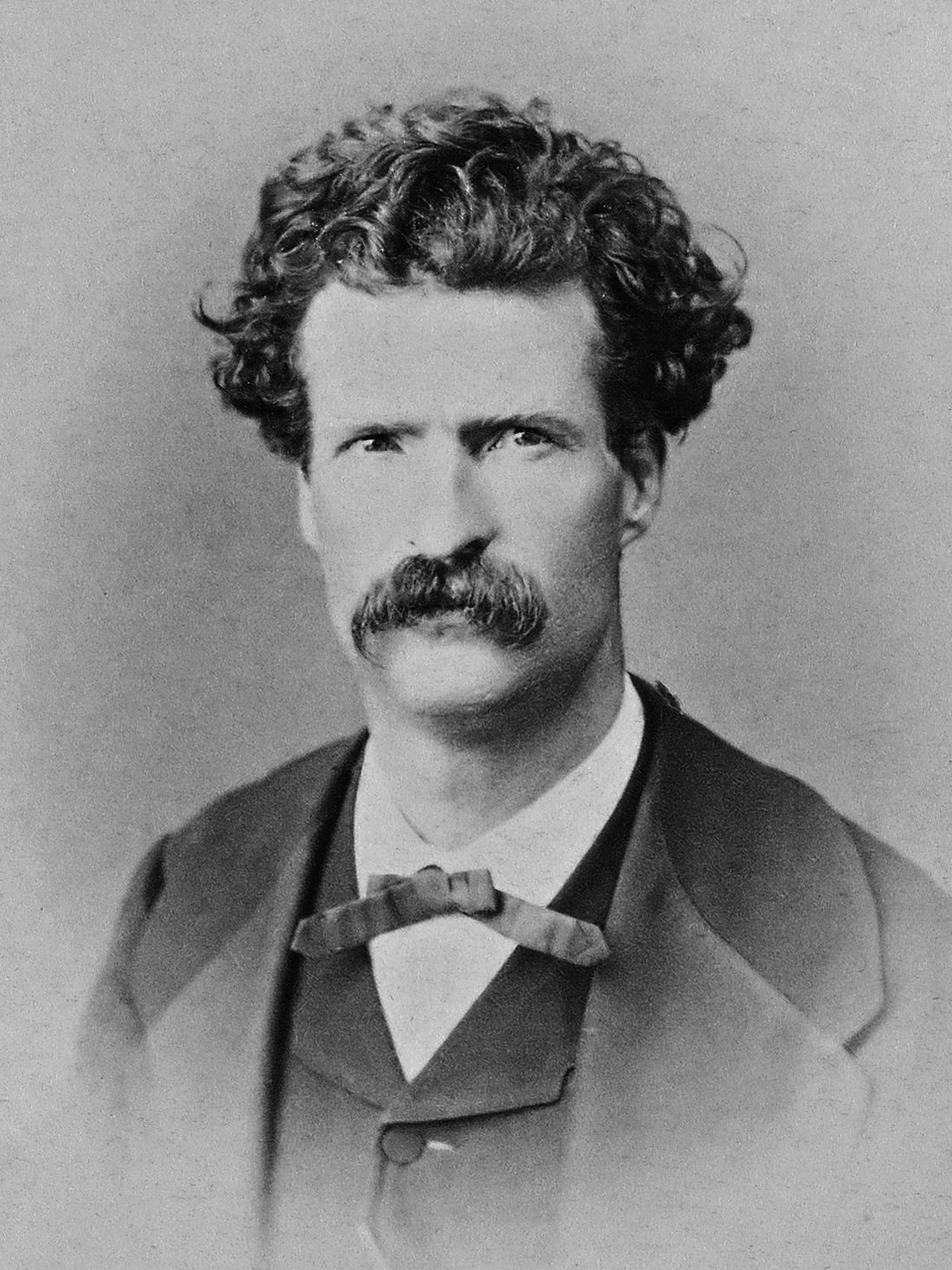

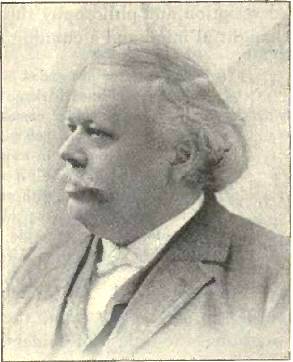

Thomas Fitch (January 27, 1838 – November 12, 1923) was an American

In 1863 he went to Nevada where he was named editor of the ''Virginia Daily Union''. On August 1, 1863,

In 1863 he went to Nevada where he was named editor of the ''Virginia Daily Union''. On August 1, 1863,

Fitch kept up his law studies and in 1864 was admitted to the bar by the

Fitch kept up his law studies and in 1864 was admitted to the bar by the

On May 1, 1871, he went to Salt Lake City in connection with mining litigation, and while there was retained by

On May 1, 1871, he went to Salt Lake City in connection with mining litigation, and while there was retained by

On October 27, 1881, just one day after the

On October 27, 1881, just one day after the

After his time in Arizona, Fitch spent two years traveling through Europe, the Southern United States, and California, after which he lived in Arizona for four years where he practiced law. In 1880 he removed to Minneapolis and formed a partnership with Mr. Morrison, which took the title of Morrison and Fitch.

In 1884 he left Arizona and for the next eight years resided part of the time in San Diego, and some time in San Francisco County. In 1891, he defended Ed Tewksbury who was accused of murdering Tom Graham in one of the final acts of violence growing out of the

After his time in Arizona, Fitch spent two years traveling through Europe, the Southern United States, and California, after which he lived in Arizona for four years where he practiced law. In 1880 he removed to Minneapolis and formed a partnership with Mr. Morrison, which took the title of Morrison and Fitch.

In 1884 he left Arizona and for the next eight years resided part of the time in San Diego, and some time in San Francisco County. In 1891, he defended Ed Tewksbury who was accused of murdering Tom Graham in one of the final acts of violence growing out of the

lawyer

A lawyer is a person who practices law. The role of a lawyer varies greatly across different legal jurisdictions. A lawyer can be classified as an advocate, attorney, barrister, canon lawyer, civil law notary, counsel, counselor, solic ...

and politician

A politician is a person active in party politics, or a person holding or seeking an elected office in government. Politicians propose, support, reject and create laws that govern the land and by an extension of its people. Broadly speaking, a ...

. He defended President Brigham Young

Brigham Young (; June 1, 1801August 29, 1877) was an American religious leader and politician. He was the second President of the Church (LDS Church), president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), from 1847 until his ...

of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, informally known as the LDS Church or Mormon Church, is a Nontrinitarianism, nontrinitarian Christianity, Christian church that considers itself to be the Restorationism, restoration of the ...

and other church leaders when Young and his denomination were prosecuted for polygamy

Crimes

Polygamy (from Late Greek (') "state of marriage to many spouses") is the practice of marrying multiple spouses. When a man is married to more than one wife at the same time, sociologists call this polygyny. When a woman is married ...

in 1871 and 1872. He also successfully defended Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; traditional dates 15 October 7021 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Roman poet of the Augustan period. He composed three of the most famous poems in Latin literature: t ...

, Morgan, and Wyatt Earp

Wyatt Berry Stapp Earp (March 19, 1848 – January 13, 1929) was an American lawman and gambler in the American West, including Dodge City, Deadwood, and Tombstone. Earp took part in the famous gunfight at the O.K. Corral, during which law ...

along with Doc Holliday

John Henry Holliday (August 14, 1851 – November 8, 1887), better known as Doc Holliday, was an American gambler, gunfighter, and dentist. A close friend and associate of lawman Wyatt Earp, Holliday is best known for his role in the event ...

when they were accused of murdering Billy Clanton

William Harrison Clanton (1862 – October 26, 1881) was an outlaw Cochise County Cowboys, Cowboy in Cochise County, Arizona Territory. He, along with his father Newman Haynes Clanton, Newman Clanton and brother Ike Clanton, worked a ranch nea ...

, and Tom and Frank McLaury

Frank McLaury born Robert Findley McLaury (March 3, 1849 – October 26, 1881) was an American outlaw. He and his brother Tom owned a ranch outside Tombstone, Arizona, Arizona Territory during the 1880s, and had ongoing conflicts with lawmen W ...

during the October 26, 1881 Gunfight at the O.K. Corral

The gunfight at the O.K. Corral was a thirty-second shootout between lawmen led by Virgil Earp and members of a loosely organized group of outlaws called the Cowboys that occurred at about 3:00 p.m. on Wednesday, October 26, 1881, in ...

.

Fitch wrote for and edited a number of newspapers during his life and served in multiple political offices. He was a stout Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

and campaigned for Abraham Lincoln across Nevada. He developed a reputation as a capable lawyer and a terrific speaker and was nicknamed the "silver-tongued orator of the Pacific." He was a member of the California State Assembly

The California State Assembly is the lower house of the California State Legislature, the upper house being the California State Senate. The Assembly convenes, along with the State Senate, at the California State Capitol in Sacramento.

The A ...

in 1862 and 1863. In 1864, he was living in Virginia City, Nevada

Virginia City is a census-designated place (CDP) that is the county seat of Storey County, Nevada, and the largest community in the county. The city is a part of the Reno– Sparks Metropolitan Statistical Area.

Virginia City developed as a boom ...

, where he edited the ''Virginia Daily Union''. He became friends with Mark Twain

Samuel Langhorne Clemens (November 30, 1835 – April 21, 1910), known by his pen name Mark Twain, was an American writer, humorist, entrepreneur, publisher, and lecturer. He was praised as the "greatest humorist the United States has p ...

who credited him with improving his writing. Fitch was a delegate to the Nevada state constitutional convention and also served as a member of the Utah state constitutional convention. He was a member of the Arizona Territorial Legislature

The Arizona Territorial Legislature was the legislative body of Arizona Territory. It was a bicameral legislature consisting of a lower house, the House of Representatives, and an upper house, the Council. Created by the Arizona Organic Act, the le ...

in 1879.

He witnessed the laying of the first rail at the western terminus of the Overland Route in Sacramento and the last one at Promontory Point in Utah. He practiced law, mostly in Nevada, Utah, and Arizona, moving frequently during his life among these states. He also briefly practiced law in Minnesota and New York. According to one obituary he was one of "the three great orators who kept California loyal to the Union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

during the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

".

Family life

Fitch was born in New York City on January 27, 1838. His father Thomas was a merchant and he attended public schools. His family had lived inNew England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian provinces ...

for six or seven generations. One of his ancestors, Sir Thomas Fitch, was Governor of Connecticut when it was a colony. At age ten years he "made the struggle of life alone," "when a young man" and until the age of 21 "was engaged in merchandising."

Thomas married three times. He married his first wife Mary H Wainright in 1858 in San Francisco, California. They had two sons, Francis born 1859 and Thomas born 1862. Mary died giving birth to Thomas.

His second wife was Anna Mariska Shultz. They married in 1863 in San Francisco, California. Anna died in 1904 in Los Angeles California.

His third wife was Serena (Rena) Fitch née Dodds. They married on 28 March 1905 in San Bernardino, California

Move west

He moved toChicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

, Illinois, in 1855, and then to Milwaukee

Milwaukee ( ), officially the City of Milwaukee, is both the most populous and most densely populated city in the U.S. state of Wisconsin and the county seat of Milwaukee County. With a population of 577,222 at the 2020 census, Milwaukee is ...

, Wisconsin, in 1856, where he started work as a clerk. In 1859, he found a job as local editor for the Milwaukee ''Free Democrat'' where he worked for one year before moving to San Francisco, California, in the summer of 1860.

Upon arriving in San Francisco, he campaigned across the state for the election of Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

and Hannibal Hamlin

Hannibal Hamlin (August 27, 1809 – July 4, 1891) was an American attorney and politician who served as the 15th vice president of the United States from 1861 to 1865, during President Abraham Lincoln's first term. He was the first Republican ...

for U.S. President and U.S. Vice President "with telling effect".

He wrote for the San Francisco ''Gazette'' and became editor of the ''Times''. While in San Francisco he married his second wife Anna Mariska Shultz in 1863. He read law

Reading law was the method used in common law countries, particularly the United States, for people to prepare for and enter the legal profession before the advent of law schools. It consisted of an extended internship or apprenticeship under the ...

at the firm of Shafter, Heydenfeld & Gould in San Francisco.

In 1862, he moved to the California foothills and El Dorado County

El Dorado County (), officially the County of El Dorado, is a county located in the U.S. state of California. As of the 2020 census, the population was 191,185. The county seat is Placerville. The County is part of the Sacramento- Roseville-A ...

, where he wrote for the Placerville ''Republican''. He was elected to the California State Assembly

The California State Assembly is the lower house of the California State Legislature, the upper house being the California State Senate. The Assembly convenes, along with the State Senate, at the California State Capitol in Sacramento.

The A ...

as the representative for the 15th District in 1862 and 1863.

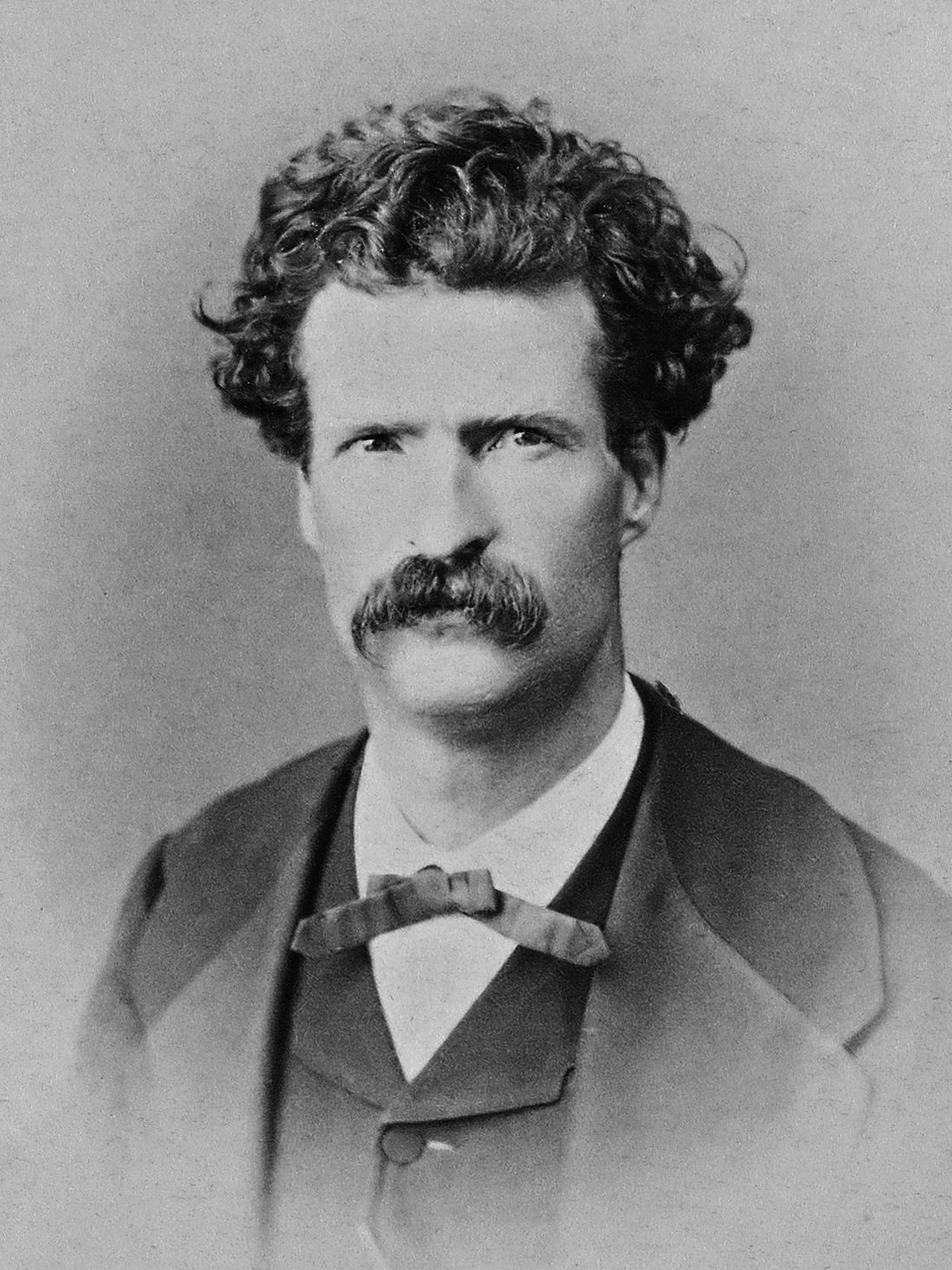

Association with Mark Twain

In 1863 he went to Nevada where he was named editor of the ''Virginia Daily Union''. On August 1, 1863,

In 1863 he went to Nevada where he was named editor of the ''Virginia Daily Union''. On August 1, 1863, Samuel Clemens

Samuel Langhorne Clemens (November 30, 1835 – April 21, 1910), known by his pen name Mark Twain, was an American writer, humorist, entrepreneur, publisher, and lecturer. He was praised as the "greatest humorist the United States has pr ...

(who also wrote under the nom de plume

A pen name, also called a ''nom de plume'' or a literary double, is a pseudonym (or, in some cases, a variant form of a real name) adopted by an author and printed on the title page or by-line of their works in place of their real name.

A pen na ...

of "Mark Twain") was writing for the Virginia City newspaper, the ''Territorial Enterprise

The ''Territorial Enterprise'', founded by William Jernegan and Alfred James on December 18, 1858, was a newspaper published in Virginia City, Nevada. Published for its first two years in Genoa in what was then Utah Territory, new owners Jonath ...

'', and reported that Fitch had challenged Joseph T. Goodman, the editor of the competing newspaper, the ''Enterprise'', to a duel. Goodman wrote an insulting article about Fitch, and Fitch impulsively challenged Goodman to a duel. Goodman had not written the article, but stood behind it and accepted the challenge. Before the duel commenced, Goodman learned that Fitch was unfamiliar with guns and at the first shot, deliberately wounded Fitch below the knee. Goodman instantly ran to Fitch's side and apologized, and insisted on taking care of Fitch until he healed. The two men became friends.

Clemens reported the duel differently: "They went out to fight this morning, with navy revolvers, at fifteen paces. The police interfered and prevented the duel." Fitch, his wife, sister-in-law, and mother-in-law occupied a suite of rooms across the hall from Clemens and Dan DeQuille

William Wright (1829–1898), better known by the pen name Dan DeQuille or Dan De Quille, was an American author, journalist, and humorist. He was best known for his written accounts of the people, events, and silver mining operations on the Com ...

in the Dagget Building in Virginia City. Fitch started his own eight-page weekly literary journal, ''The Weekly Occidental'', in which Clemens was very interested. Fitch planned to publish a novel in serial form, with successive weekly chapters contributed by Fitch, his wife Anna, J. T. Goodman, Dan De Quille, Rollin M. Daggett and Clemens. The ''Occidental'' was published from October 29, 1864, until April 15, 1865, but ceased publication before Twain could contribute.

Clemens credited Fitch with giving him his "first really profitable lesson" in writing. In 1866, Clemens presented his lecture on the Sandwich Islands to a crowd in Washoe City. Clemens commented that, "When I first began to lecture, and in my earlier writings, my sole idea was to make comic capital out of everything I saw and heard." Fitch told him, "Clemens, your lecture was magnificent. It was eloquent, moving, sincere. Never in my entire life have I listened to such a magnificent piece of descriptive narration. But you committed one unpardonable sin—the unpardonable sin. It is a sin you must never commit again. You closed a most eloquent description, by which you had keyed your audience up to a pitch of the intensest interest, with a piece of atrocious anti-climax which nullified all the really fine effect you had produced."

Admitted to bar

Fitch kept up his law studies and in 1864 was admitted to the bar by the

Fitch kept up his law studies and in 1864 was admitted to the bar by the Nevada Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of Nevada is the highest state court of the U.S. state of Nevada, and the head of the Nevada Judiciary. The main constitutional function of the Supreme Court is to review appeals made directly from the decisions of the distric ...

. In the same year he was elected from Virginia City as a delegate to the Nevada State Constitutional Convention. He was nominated by the Union Party and unsuccessfully campaigned for the role as territorial delegate to Congress from the Nevada Territory in 1864. He also campaigned across Nevada for Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

and Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. He assumed the presidency as he was vice president at the time of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a Dem ...

. In 1865 Fitch moved to Washoe County and soon after was appointed county district attorney. When his term as district attorney expired in 1866, he moved to Belmont, Nevada

Belmont is a ghost town in Nye County, Nevada, United States along former State Route 82. The town is a historic district listed in the National Register of Historic Places. It is Nevada Historical Marker number 138.

History

Belmont was establi ...

, and practiced law there until 1868. He was elected as a Republican to the U.S. House of Representatives and the Forty-first Congress of the United States, serving from March 4, 1869 – March 3, 1871, and opened his first law practice.

In December 1869, he spoke against the pending anti-polygamy

Crimes

Polygamy (from Late Greek (') "state of marriage to many spouses") is the practice of marrying multiple spouses. When a man is married to more than one wife at the same time, sociologists call this polygyny. When a woman is married ...

Cullom Bill, which would strip the Utah territory

The Territory of Utah was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from September 9, 1850, until January 4, 1896, when the final extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Utah, the 45th state. ...

's residents of local authority. It proposed instead to outlaw the Utah Territorial Legislature, eliminate the offices of the territorial marshal and attorney general and transfer their authority to federal officers, give the federally appointed Governor the authority to appoint all officers in the territory, excluding constables, and place all local and territorial matters in the hands of federally appointed officials. Fitch attempted to persuade Congress that they should avoid the prospect of another Mormon war.

His opposition to the bill may have cost him votes at home, and he was not reelected in 1870 even though he represented the dominant Republican party. In 1870, his wife published her first novel, ''Bound Down: Or Life And Its Possibilities''. Tom and his wife published ''Better days: or, A millionaire of to-morrow'' in 1891, and she wrote two more books in 1891 and 1893.

Defends Brigham Young and church leaders

On May 1, 1871, he went to Salt Lake City in connection with mining litigation, and while there was retained by

On May 1, 1871, he went to Salt Lake City in connection with mining litigation, and while there was retained by Brigham Young

Brigham Young (; June 1, 1801August 29, 1877) was an American religious leader and politician. He was the second President of the Church (LDS Church), president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), from 1847 until his ...

as an attorney and general counsel to the Church. He was in charge of all the criminal and civil litigation in which Brigham Young and other Church leaders were involved.

On October 2, 1871, Brigham Young, Daniel H. Wells

Daniel Hanmer Wells (October 27, 1814 – March 24, 1891) was an American apostle of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) and the 3rd mayor of Salt Lake City.

Biography

Early life

Wells was born in Trenton, New Yor ...

and others were served with an arrest warrant by U. S. Marshal at Young's residence in Salt Lake City. He was charged with lewd and lascivious cohabitation with his plural wives but allowed to remain in his home guarded by a marshal. The next day Apostle George Q. Cannon

George Quayle Cannon (January 11, 1827 – April 12, 1901) was an early member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), and served in the First Presidency under four successive pr ...

was also arrested on similar charges. On October 9, 1871, Brigham Young appeared before Chief Justice Thomas McKean

Thomas McKean (March 19, 1734June 24, 1817) was an American lawyer, politician, and Founding Father. During the American Revolution, he was a Delaware delegate to the Continental Congress, where he signed the Continental Association, the United ...

in the case of People versus Brigham Young, Sr.. Fitch represented the church leaders and arranged for Young's bail. Fitch moved to quash the indictment.

On October 12, Judge McKean issued his decision on Fitch's motion to quash the indictment in which he positioned the case as a trial of the entire church.

McKean charged the defense with "proving that the polygamous practices charged in the indictment are not crimes." On October 16, Young pleaded innocent. The attorneys asked for time to prepare for the case and based on McKean's ruling, Fitch inferred that the trial would proceed in March. Young departed for St. George, Utah and Fitch left for New York. Shortly after their departure, McKean set the trial date for November 20. Assistant defense attorney Hempstead protested, and the prosecutor demanded forfeiture of Young's bail. The Associated Press

The Associated Press (AP) is an American non-profit news agency headquartered in New York City. Founded in 1846, it operates as a cooperative, unincorporated association. It produces news reports that are distributed to its members, U.S. newspa ...

ran a story that Brigham Young had fled from justice.

William "Wild Bill" Hickman, who had been arrested and jailed for murdering government arms dealer Richard Yates during the Utah War

The Utah War (1857–1858), also known as the Utah Expedition, Utah Campaign, Buchanan's Blunder, the Mormon War, or the Mormon Rebellion was an armed confrontation between Mormon settlers in the Utah Territory and the armed forces of the US go ...

, implicated Brigham Young and others in Yates' murder. Hickman was excommunicated

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to end or at least regulate the communion of a member of a congregation with other members of the religious institution who are in normal communion with each other. The purpose ...

from the church as a result, although he was never convicted, nor was Young ever indicted based on his testimony. On April 15, 1872, the U. S. Supreme Court ruled in "Clinton ''et al'' vs. Englebrecht ''et al''" that McKean's indictments were invalid, and Young and others were released from further prosecution.

He was elected a member of the 1872 Utah Constitutional Convention On the second day of the convention, he harshly criticized federal Judge McKean, who had been appointed by President Grant

Grant or Grants may refer to:

Places

*Grant County (disambiguation)

Australia

* Grant, Queensland, a locality in the Barcaldine Region, Queensland, Australia

United Kingdom

*Castle Grant

United States

* Grant, Alabama

*Grant, Inyo County, C ...

in 1870 as Chief Justice of Utah Territorial Supreme Court. McKean had removed virtually all locally elected officials from their roles and supplanted their authority with federal officials he appointed. McKean believed that he had a divinely appointed mission in Utah, "to the carrying out of which he was evidently prepared to subordinate all other considerations." He said this included "whenever and wherever I may find the local or federal laws obstructing or interfering therewith, by God's blessing I shall trample them under my feet." Fitch described him as "A sort of missionary exercising judicial functions," "a very determined man," "of considerable personal courage," "but not fit to be a judge."

During February and March Fitch spoke eloquently about the political necessity of forgoing polygamy from the Utah state constitution.

On April 6, 1873, William H. Hooper and Thomas Fitch were elected as United States senators from the proposed State of Deseret, should it be admitted into the Union.

While practicing law in Utah, he very likely followed the prosecution of John D. Lee

John Doyle Lee (September 6, 1812 – March 23, 1877) was an American pioneer and prominent early member of the Latter Day Saint Movement in Utah. Lee was later convicted as a mass murderer for his complicity in the Mountain Meadows massacre, s ...

. Lee had been charged with murder in what was probably the most closely followed trial of the 19th century, the Mountain Meadows Massacre

The Mountain Meadows Massacre (September 7–11, 1857) was a series of attacks during the Utah War that resulted in the mass murder of at least 120 members of the Baker–Fancher emigrant wagon train. The massacre occurred in the southern U ...

. Lee was the only person brought to trial for the attack, in which "a band of Mormons dressed as Paiute Indians ambushed a wagon train heading to California and killed more than a hundred innocents." Spicer and Fitch would later meet again in 1881 in Tombstone, Arizona as a result of the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral

The gunfight at the O.K. Corral was a thirty-second shootout between lawmen led by Virgil Earp and members of a loosely organized group of outlaws called the Cowboys that occurred at about 3:00 p.m. on Wednesday, October 26, 1881, in ...

. He was defended by Wells Spicer

Wells W. Spicer (1831–1885 or 1887) was an American journalist, prospector, politician, lawyer and judge whose legal career immersed him in two significant events in frontier history: the Mountain Meadows massacre in the Utah Territory in 1857; ...

and Fitch was probably acquainted with Spicer's work as an attorney. In 1874 Fitch returned to San Francisco and made his home there until 1877.

In 1877 he relocated to Prescott, Arizona, where he practiced law until 1884 and served as an adviser to Governor John C. Frémont

John Charles Frémont or Fremont (January 21, 1813July 13, 1890) was an American explorer, military officer, and politician. He was a U.S. Senator from California and was the first Republican nominee for president of the United States in 1856 ...

. Clark Churchill joined him as a partner during 1878–1880. In 1878 he and several other members of the bar founded the Prescott Dramatic Association, an amateur theater

Amateur theatre, also known as amateur dramatics, is theatre performed by amateur actors and singers. Amateur theatre groups may stage plays, revues, musicals, light opera, pantomime or variety shows, and do so for the social activity as well as f ...

troupe. He cast Harry Du Souchet in a role while Du Souchet was still a telegraph operator

A telegraphist (British English), telegrapher (American English), or telegraph operator is an operator who uses a telegraph key to send and receive the Morse code in order to communicate by land lines or radio.

During the Great War the Royal ...

and before he became famous in New York City.

In 1879 he was elected a member of the 10th Arizona Territorial Legislature

The 10th Arizona Territorial Legislative Assembly was a session of the Arizona Territorial Legislature which convened on January 6, 1879, in Prescott, Arizona Territory. The session was the last to be composed of nine Council members and eightee ...

representing Yavapai County

Yavapai County is near the center of the U.S. state of Arizona. As of the 2020 census, its population was 236,209, making it the fourth-most populous county in Arizona. The county seat is Prescott.

Yavapai County comprises the Prescott, AZ M ...

and was chosen as Chairman of the House Judiciary Committee. He served alongside Johnny Behan

John Harris Behan (October 24, 1844 – June 7, 1912) was an American law enforcement officer and politician who served as Sheriff of Cochise County in the Arizona Territory, during the gunfight at the O.K. Corral and was known for his opposit ...

from Mohave County

Mohave County is in the northwestern corner of the U.S. state of Arizona. As of the 2020 census, its population was 213,267. The county seat is Kingman, and the largest city is Lake Havasu City. It is the fifth largest county in the United St ...

. Later in 1879 he moved his law practice to the frontier

A frontier is the political and geographical area near or beyond a boundary. A frontier can also be referred to as a "front". The term came from French in the 15th century, with the meaning "borderland"—the region of a country that fronts o ...

silver-mining boomtown

A boomtown is a community that undergoes sudden and rapid population and economic growth, or that is started from scratch. The growth is normally attributed to the nearby discovery of a precious resource such as gold, silver, or oil, although ...

of Tombstone. He was joined by William J. Hunsaker from San Diego. In October 1881 Fitch and Hunsaker were hired by the Earps when they were indicted for murder. Behan was by this time the Cochise County Sheriff and a witness for the prosecution during the Earp's preliminary hearing that determined whether the Earps and Doc Holliday

John Henry Holliday (August 14, 1851 – November 8, 1887), better known as Doc Holliday, was an American gambler, gunfighter, and dentist. A close friend and associate of lawman Wyatt Earp, Holliday is best known for his role in the event ...

would face murder charges as a result of the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral

The gunfight at the O.K. Corral was a thirty-second shootout between lawmen led by Virgil Earp and members of a loosely organized group of outlaws called the Cowboys that occurred at about 3:00 p.m. on Wednesday, October 26, 1881, in ...

.

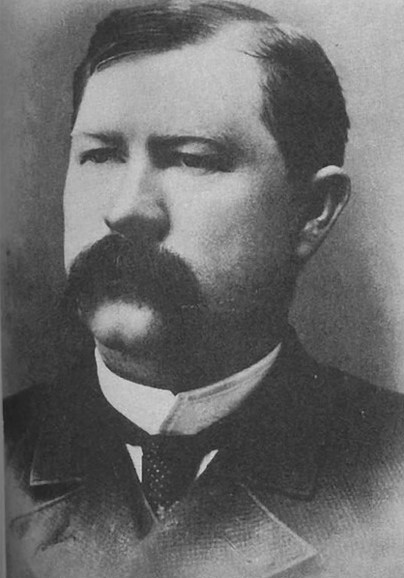

Defends Earps and Doc Holliday

On October 27, 1881, just one day after the

On October 27, 1881, just one day after the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral

The gunfight at the O.K. Corral was a thirty-second shootout between lawmen led by Virgil Earp and members of a loosely organized group of outlaws called the Cowboys that occurred at about 3:00 p.m. on Wednesday, October 26, 1881, in ...

that left Billy Clanton

William Harrison Clanton (1862 – October 26, 1881) was an outlaw Cochise County Cowboys, Cowboy in Cochise County, Arizona Territory. He, along with his father Newman Haynes Clanton, Newman Clanton and brother Ike Clanton, worked a ranch nea ...

and Tom and Frank McLaury

Frank McLaury born Robert Findley McLaury (March 3, 1849 – October 26, 1881) was an American outlaw. He and his brother Tom owned a ranch outside Tombstone, Arizona, Arizona Territory during the 1880s, and had ongoing conflicts with lawmen W ...

dead and Morgan and Virgil Earp

Virgil Walter Earp (July 18, 1843 – October 19, 1905) was both deputy U.S. Marshal and Tombstone, Arizona City Marshal when he led his younger brothers Wyatt and Morgan, and Doc Holliday, in a confrontation with outlaw Cowboys at the Gunfig ...

wounded, Ike Clanton

Joseph Isaac Clanton (1847 – June 1, 1887) was a member of a loose association of outlaws known as The Cowboys who clashed with lawmen Wyatt, Virgil and Morgan Earp as well as Doc Holliday. On October 26, 1881, Clanton was present at the Gunf ...

filed murder charges. A preliminary hearing was convened by Judge Wells Spicer

Wells W. Spicer (1831–1885 or 1887) was an American journalist, prospector, politician, lawyer and judge whose legal career immersed him in two significant events in frontier history: the Mountain Meadows massacre in the Utah Territory in 1857; ...

on October 31. The Earps chose "the Silver-Tongued Orator of the Pacific Slope" as their lead attorney. Doc Holliday

John Henry Holliday (August 14, 1851 – November 8, 1887), better known as Doc Holliday, was an American gambler, gunfighter, and dentist. A close friend and associate of lawman Wyatt Earp, Holliday is best known for his role in the event ...

was defended by United States Court Commissioner Thomas J. Drum.

Preliminary hearing

The preliminary hearing turned into a month-long dramatic court-room confrontation, the longest in Arizona history. The legal purpose of the hearing was to determine whether a crime had actually been committed, and whether there was "sufficient cause" to bring the four defendants to trial. Fitch was 43 when he arrived in Tombstone early in 1881. He brought a wealth of trial experience incriminal law

Criminal law is the body of law that relates to crime. It prescribes conduct perceived as threatening, harmful, or otherwise endangering to the property, health, safety, and moral welfare of people inclusive of one's self. Most criminal law i ...

from his time in California, Nevada, and Utah. Fitch also contributed US$10,000 to Wyatt Earp's defense fund.

Prosecution blame Earps

The prosecution presented considerable evidence in an attempt to bind the Earps and Holliday over for trial. On the second day of the hearings, William Allen testified for the prosecution that "the firing commenced by the Earp party. I think it was Doc Holliday who fired first." Johnny Behan testified that he tried to prevent the confrontation. I "told them...I was down there for the purpose of disarming the Clantons and McLaurys. They wouldn't heed me, paid no attention. And I said, 'Gentleman, I am Sheriff of this County, and I am not going to allow any trouble if I can help it.' They brushed past me." He saidCowboys

A cowboy is a professional pastoralist or mounted livestock herder, usually from the Americas or Australia.

Cowboy(s) or The Cowboy(s) may also refer to:

Film and television

* ''Cowboy'' (1958 film), starring Glenn Ford

* ''Cowboy'' (1966 film), ...

had put up their hands or thrown open their coats to show they weren't armed, and that Doc Holliday had fired first. He testified that the first five shots had come from the Earps. He clearly blamed the Earps and Doc Holliday for instigating the shootout.

Fitch had seen Judge Wells Spicer

Wells W. Spicer (1831–1885 or 1887) was an American journalist, prospector, politician, lawyer and judge whose legal career immersed him in two significant events in frontier history: the Mountain Meadows massacre in the Utah Territory in 1857; ...

as an attorney defend John D. Lee

John Doyle Lee (September 6, 1812 – March 23, 1877) was an American pioneer and prominent early member of the Latter Day Saint Movement in Utah. Lee was later convicted as a mass murderer for his complicity in the Mountain Meadows massacre, s ...

in the notorious 1875 Mountain Meadows Massacre

The Mountain Meadows Massacre (September 7–11, 1857) was a series of attacks during the Utah War that resulted in the mass murder of at least 120 members of the Baker–Fancher emigrant wagon train. The massacre occurred in the southern U ...

, and it was likely that he had developed a deep appreciation for the judge. The two men had a great deal in common. Both had practiced criminal law, had written for newspapers, and both were Republicans. Fitch may have based his defense on what he saw as Spicer's repugnance of the perjured testimony and unjust outcome in Lee's case. In a preliminary hearing

Within some criminal justice, criminal justice systems, a preliminary hearing, preliminary examination, preliminary inquiry, evidentiary hearing or probable cause hearing is a proceeding, after a criminal complaint has been filed by the prosecuto ...

, the attorneys usually do not reveal their entire defense strategy. Fitch may have chosen to use the hearing as a forum to expose the entire case because he thought Spicer held considerably skepticism about the prosecution's case and would allow Fitch considerable latitude. Judge Spicer made several rulings favorable to the defense.

Prepares written testimony

Fitch had Wyatt Earp prepare a written statement, as permitted by Section 133 of Arizona law, which would not allow the prosecution tocross-examine

In law, cross-examination is the interrogation of a witness called by one's opponent. It is preceded by direct examination (in Ireland, the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, South Africa, India and Pakistan known as examination-in-chief) and ...

him. The prosecution vociferously objected. Although the statute wasn't specific about whether it was legal for a defendant to read his statement, Spicer allowed his testimony to proceed.

Fitch was very successful in cornering witnesses into offering conflicting testimony or saying they did not remember. In several instances, he obtained testimony from prosecution witnesses and followed up with statements corroborated by others that conflicted with the prior testimony. Prosecution witnesses repeatedly stumbled when Fitch asked them questions, in many instances replying weakly, "I don't remember." Tombstone's chief prosecutor was Republican Lyttleton Price, who was aided by Ben Goodrich and, three days into the hearing, by co-counsel Will McLaury, brother to the dead Cowboys Frank and Tom McLaury. Will McLaury left his Texas law practice and his children with a caretaker to help prosecute the Earps and Doc Holliday. He summed up his attitude towards the Earps in a letter to a law partner: "I think I can hang them."

Exposes prosecution weaknesses

Cochise County Sheriff Johnny Behan testimony for the prosecution crumbled under Fitch's questioning. Behan testified that he had seen Doc Holliday holding a shotgun prior to the gunfight. He then offered an improbable scenario: Doc Holliday had first fired a nickel-plated pistol, then fired the shotgun, and then resuming shooting with the pistol. Another influential witness for the defense was Deputy District Attorney Winfield Scott Williams. In earlier testimony, Behan denied telling Virgil on the night after the gunfight that Virgil had acted properly. Williams testified that Sheriff Behan had inaccurately reported that conversation during which, according to Williams, Behan told Virgil that one of the McLaury brothers drew his gun first, and "You did perfectly right." Behan denied that he said anything resembling this. Fitch's ability to impeach the testimony of the County Sheriff and key witness probably influenced Judge Spicer, who had been subject to perjured testimony in the John D. Lee case that resulted in his client's execution. Fitch was able to damage Ike Clanton's credibility through skillful questioning. In response to his questioning, Clanton denied seeking confirmation from Wyatt Earp about the reward offered by Wells, Fargo & Co, " dead or alive", for the stage robbers. When shown the telegram confirming the reward would be paid in either circumstance, he denied having ever seen it before. On November 12, he got Clanton to testify that he had never spoken to Ned Boyle on the morning of the gunfight, and on November 23, Boyle's testimony contradicted Clanton's. During Ike Clanton's testimony undercross-examination

In law, cross-examination is the interrogation of a witness called by one's opponent. It is preceded by direct examination (in Ireland, the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, South Africa, India and Pakistan known as examination-in-chief) and m ...

by Fitch, he said "I don't remember" 14 times. This and other contradictions impugned Clanton's testimony.

Earps exonerated

After a month of testimony from 30 witnesses, Spicer concluded that there was not enough evidence to indict the men. In his ruling, he noted that Ike Clanton had the night before, while unarmed, publicly declared that the Earp brothers and Holliday had insulted him, and that when he was armed he intended to shoot them or fight them on sight. On the morning of the shooting Ike was armed with revolver and Winchester rifle. Spicer noted that: Spicer specifically noted that Ike Clanton claimed the Earps were out to murder him, yet while unarmed had been allowed by the Earps to escape unharmed from the fight. He wrote, "the great fact, most prominent in the matter, to wit, that Isaac Clanton was not injured at all, and could have been killed first and easiest." He described Frank McLaury's insistence that he would not give up his weapons unless the marshal and his deputies also gave up their arms as a "proposition both monstrous and startling!" Spicer said that Virgil in "calling upon Wyatt Earp, and J. H. Holliday to assist him... committed an injudicious and censurable act, and although in this he acted incautiously and without due circumspection," in the end "the Earps acted wisely, discretely and prudentially, to secure their own self preservation." "He needed the assistance and support of staunch and true friends, upon whose courage, coolness and fidelity he could depend..." Spicer noted that if Wyatt and Holliday had not backed up Marshal Earp, then he would have faced even more overwhelming odds than he had, and could not possibly have survived. He invited the grand jury to confirm his findings, and two weeks later, it agreed with Spicer's finding and also refused to indict the men.Later career

After his time in Arizona, Fitch spent two years traveling through Europe, the Southern United States, and California, after which he lived in Arizona for four years where he practiced law. In 1880 he removed to Minneapolis and formed a partnership with Mr. Morrison, which took the title of Morrison and Fitch.

In 1884 he left Arizona and for the next eight years resided part of the time in San Diego, and some time in San Francisco County. In 1891, he defended Ed Tewksbury who was accused of murdering Tom Graham in one of the final acts of violence growing out of the

After his time in Arizona, Fitch spent two years traveling through Europe, the Southern United States, and California, after which he lived in Arizona for four years where he practiced law. In 1880 he removed to Minneapolis and formed a partnership with Mr. Morrison, which took the title of Morrison and Fitch.

In 1884 he left Arizona and for the next eight years resided part of the time in San Diego, and some time in San Francisco County. In 1891, he defended Ed Tewksbury who was accused of murdering Tom Graham in one of the final acts of violence growing out of the Pleasant Valley War

The Pleasant Valley War, sometimes called the Tonto Basin Feud, or Tonto Basin War, or Tewksbury-Graham Feud, was a range war fought in Pleasant Valley, Arizona in the years 1882–1892. The conflict involved two feuding families, the Grahams an ...

in central Arizona. He settled in New York City in December 1892 for a period before he returned full-time to Arizona in 1893. He briefly moved to Utah in 1894 when the territory was granted statehood and announced his candidacy for United States senator but failed to receive the nomination. Fitch returned to Arizona and settled in Phoenix where he remained through at least 1896.

Later in his life he credited his oratorical skills to the influence of Col. E. D. Baker and Thomas Starr King

Thomas Starr King (December 17, 1824 – March 4, 1864), often known as Starr King, was an American Universalist and Unitarian minister, influential in California politics during the American Civil War, and Freemason. Starr King spoke z ...

and to the time he spent with Mark Twain

Samuel Langhorne Clemens (November 30, 1835 – April 21, 1910), known by his pen name Mark Twain, was an American writer, humorist, entrepreneur, publisher, and lecturer. He was praised as the "greatest humorist the United States has p ...

and Joaquin Miller

Cincinnatus Heine Miller (; September 8, 1837 – February 17, 1913), better known by his pen name Joaquin Miller (), was an American poet, author, and frontiersman. He is nicknamed the "Poet of the Sierras" after the Sierra Nevada, about which h ...

. He also said he was influenced by the friendship of Leland Stanford

Amasa Leland Stanford (March 9, 1824June 21, 1893) was an American industrialist and politician. A member of the Republican Party, he served as the 8th governor of California from 1862 to 1863 and represented California in the United States Se ...

, Collis P. Huntington

Collis Potter Huntington (October 22, 1821 – August 13, 1900) was an American industrialist and railway magnate. He was one of the Big Four of western railroading (along with Leland Stanford, Mark Hopkins, and Charles Crocker) who invested ...

, Mark Hopkins and Charles Crocker

Charles Crocker (September 16, 1822 – August 14, 1888) was an American railroad executive who was one of the founders of the Central Pacific Railroad, which constructed the westernmost portion of the first transcontinental railroad, and took ...

. He spoke in Phoenix in 1906 in support of the territory's desire for dual statehood with New Mexico. He lived at different times in San Diego and in Honolulu. While in Hawaii, he represented sake

Sake, also spelled saké ( ; also referred to as Japanese rice wine), is an alcoholic beverage of Japanese origin made by fermenting rice that has been polished to remove the bran. Despite the name ''Japanese rice wine'', sake, and indee ...

manufacturers who were attempting to have their product classified as a beer instead of a liquor for customs purposes. In 1909 moved to Los Angeles where he became a writer for the Los Angeles Times

The ''Los Angeles Times'' (abbreviated as ''LA Times'') is a daily newspaper that started publishing in Los Angeles in 1881. Based in the LA-adjacent suburb of El Segundo since 2018, it is the sixth-largest newspaper by circulation in the Un ...

, a position he held through 1916. He died at a Masonic

Freemasonry or Masonry refers to Fraternity, fraternal organisations that trace their origins to the local guilds of Stonemasonry, stonemasons that, from the end of the 13th century, regulated the qualifications of stonemasons and their inte ...

home in Decoto, California, on November 12, 1923. He was interred in Cypress (later renamed Chapel of the Chimes) Cemetery in Decoto (later Hayward), California.

References

Further reading

* * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Fitch, Thomas 1838 births 1923 deaths Journalists from New York City Nevada Unionists Republican Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Nevada Republican Party members of the California State Assembly Utah Republicans Arizona Republicans Members of the Arizona Territorial Legislature District attorneys in Nevada American lawyers admitted to the practice of law by reading law American frontier Arizona lawyers Cochise County conflict Editors of California newspapers Editors of Wisconsin newspapers Hawaii Republicans Lawyers from Milwaukee Lawyers from San Francisco People from Nye County, Nevada People from Placerville, California People of the American Old West People of Utah Territory Politicians from Chicago Politicians from Honolulu Politicians from Milwaukee Politicians from Prescott, Arizona Politicians from Salt Lake City Politicians from San Diego Politicians from San Francisco Utah lawyers 19th-century American lawyers 19th-century American newspaper editors 19th-century American politicians Burials in Alameda County, California