Theresienstadt Ghetto on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Theresienstadt Ghetto was established by the SS during World War II in the fortress town of Terezín, in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia ( German-occupied Czechoslovakia). Theresienstadt served as a waystation to the

extermination camps

Nazi Germany used six extermination camps (german: Vernichtungslager), also called death camps (), or killing centers (), in Central Europe during World War II to systematically murder over 2.7 million peoplemostly Jewsin the Holocaust. The v ...

. Its conditions were deliberately engineered to hasten the death of its prisoners, and the ghetto also served a propaganda role. Unlike other ghettos, the exploitation of forced labor was not economically significant.

The ghetto was established by the transportation of Czech Jews in November 1941. The first German and Austrian Jews arrived in June 1942; Dutch and Danish Jews came at the beginning in 1943, and prisoners of a wide variety of nationalities were sent to Theresienstadt in the last months of the war. About 33,000 people died at Theresienstadt, mostly from malnutrition and disease. More than 88,000 people were held there for months or years before being deported to extermination camps

Nazi Germany used six extermination camps (german: Vernichtungslager), also called death camps (), or killing centers (), in Central Europe during World War II to systematically murder over 2.7 million peoplemostly Jewsin the Holocaust. The v ...

and other killing sites; the Jewish Council's ('' Judenrat'') role in choosing those to be deported has attracted significant controversy. Including 4,000 of the deportees who survived, the total number of survivors was around 23,000.

Theresienstadt was known for its relatively rich cultural life, including concerts, lectures, and clandestine education for children. The fact that it was governed by a Jewish self-administration as well as the large number of "prominent" Jews imprisoned there facilitated the flourishing of cultural life. This spiritual legacy has attracted the attention of scholars and sparked interest in the ghetto. In the postwar period, a few of the SS perpetrators and Czech guards were put on trial, but the ghetto was generally forgotten by the Soviet authorities. The Terezín Ghetto Museum is visited by 250,000 people each year.

Background

The fortress town of Theresienstadt ( cs, Terezín) is located in the north-west region ofBohemia

Bohemia ( ; cs, Čechy ; ; hsb, Čěska; szl, Czechy) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. Bohemia can also refer to a wider area consisting of the historical Lands of the Bohemian Crown ruled by the Bohem ...

, across the river from the city of Leitmeritz ( cs, Litoměřice) and about north of Prague. Founded on 22 September 1784 on the orders of the Habsburg monarch Joseph II, it was named Theresienstadt, after his mother Maria Theresa

Maria Theresa Walburga Amalia Christina (german: Maria Theresia; 13 May 1717 – 29 November 1780) was ruler of the Habsburg dominions from 1740 until her death in 1780, and the only woman to hold the position ''suo jure'' (in her own right). ...

of Austria. Theresienstadt was used as a military base by Austria-Hungary and later by the First Czechoslovak Republic after 1918, while the " Small Fortress" across the river was a prison. Ironically Theresienstadt had been the place of imprisonment for Franz Ferdinand murderer Gavrilo Princip, who had (albeit inadverently) set off an extremely unlikely butterfly effect that would ultimate lead to World War II and the Holocaust. Following the Munich Agreement in September 1938, Germany annexed the Sudetenland

The Sudetenland ( , ; Czech and sk, Sudety) is the historical German name for the northern, southern, and western areas of former Czechoslovakia which were inhabited primarily by Sudeten Germans. These German speakers had predominated in the ...

(German-speaking region of Czechoslovakia). Although Leitmeritz was ceded to Germany, Theresienstadt remained in the Czechoslovak rump state until the German invasion German invasion may refer to:

Pre-1900s

* German invasion of Hungary (1063)

World War I

* German invasion of Belgium (1914)

* German invasion of Luxembourg (1914)

World War II

* Invasion of Poland

* German invasion of Belgium (1940)

...

of the Czech lands on 15 March 1939. The Small Fortress became a Gestapo prison in 1940 and the fortress town became a Wehrmacht military base, with about 3,500 soldiers and 3,700 civilians, largely employed by the army, living there in 1941.

In October 1941, as the Reich Security Main Office

The Reich Security Main Office (german: Reichssicherheitshauptamt or RSHA) was an organization under Heinrich Himmler in his dual capacity as ''Chef der Deutschen Polizei'' (Chief of German Police) and ''Reichsführer-SS'', the head of the Nazi ...

(RSHA) was planning transports of Jews from Germany, Austria, and the Protectorate to the ghettos in Nazi-occupied Eastern Europe, a meeting was held in which it was decided to convert Theresienstadt into a transit center for Czech Jews. Those present included Adolf Eichmann

Otto Adolf Eichmann ( ,"Eichmann"

''

''

RSHA section IV B 4 (Jewish affairs) and Hans Günther, the director of the Central Office for Jewish Emigration in Prague. Reinhard Heydrich, the RSHA chief, approved of Theresienstadt as a location for the ghetto. At the Wannsee Conference on 20 January 1942, Heydrich announced that Theresienstadt would be used to house Jews over the age of 65 from the Reich, as well as those who had been severely wounded fighting for the Central Powers in World War I or won the Iron Cross 1st Class or a higher decoration during that war. These Jews could not plausibly perform forced labor, and therefore Theresienstadt helped conceal the true nature of deportation to the East. Later, Theresienstadt also came to house "prominent" Jews whose disappearance in an extermination camp could have drawn attention from abroad. To lull victims into a false sense of security, the SS advertised Theresienstadt as a "spa town" where Jews could retire, and encouraged them to sign fraudulent home purchase contracts, pay "deposits" for rent and board, and surrender life insurance policies and other assets.

On 24 November 1941, the first trainload of deportees arrived at the Sudeten barracks in Theresienstadt; they were 342 young Jewish men whose task was to prepare the town for the arrival of thousands of other Jews beginning 30 November. Another transport of 1,000 men arrived on 4 December; this included Jakob Edelstein and the original members of the Council of Elders. Deportees to the ghetto had to surrender all possessions except for of luggage, which they had to carry with them from the railway station at Bauschowitz (Bohušovice), away; the walk was difficult for elderly and ill Jews, many of whom died on the journey. After arriving, prisoners were sent to the ( en, sluice), where they were registered and deprived of their remaining possessions.

The 24 November and 4 December transports, consisting mostly of Jewish craftsmen, engineers, and other skilled workers of Zionist sympathies, were known as the '' Aufbaukommando'' (Work Detail) and their members were exempt from deportation until September 1943. The members of the ''Aufbaukommando'' used creative methods to improve the infrastructure of the ghetto and prepare it to house an average of 40,000 people during its existence. The construction project was funded by stolen Jewish property. When the first transport arrived, there was only one vat for coffee with a capacity of ; by the next year, there were sufficient kettles to make 50,000 cups of ersatz coffee in two hours. The waterworks often broke down during the first months due to inadequate capacity. To improve potable water supply, and so everyone could wash daily, workers drilled wells and overhauled the pipe system. The Germans provided the materials for these improvements, largely to reduce the chance of communicable disease spreading beyond the ghetto, but Jewish engineers directed the projects.

Jews lived in the eleven barracks in the fortress, while civilians continued to inhabit the 218 civilian houses. Segregation between the two groups was strictly enforced and resulted in harsh punishments on Jews who left their barracks. By the end of the year, 7,365 people had been deported to the ghetto, of whom 2,000 were from

On 24 November 1941, the first trainload of deportees arrived at the Sudeten barracks in Theresienstadt; they were 342 young Jewish men whose task was to prepare the town for the arrival of thousands of other Jews beginning 30 November. Another transport of 1,000 men arrived on 4 December; this included Jakob Edelstein and the original members of the Council of Elders. Deportees to the ghetto had to surrender all possessions except for of luggage, which they had to carry with them from the railway station at Bauschowitz (Bohušovice), away; the walk was difficult for elderly and ill Jews, many of whom died on the journey. After arriving, prisoners were sent to the ( en, sluice), where they were registered and deprived of their remaining possessions.

The 24 November and 4 December transports, consisting mostly of Jewish craftsmen, engineers, and other skilled workers of Zionist sympathies, were known as the '' Aufbaukommando'' (Work Detail) and their members were exempt from deportation until September 1943. The members of the ''Aufbaukommando'' used creative methods to improve the infrastructure of the ghetto and prepare it to house an average of 40,000 people during its existence. The construction project was funded by stolen Jewish property. When the first transport arrived, there was only one vat for coffee with a capacity of ; by the next year, there were sufficient kettles to make 50,000 cups of ersatz coffee in two hours. The waterworks often broke down during the first months due to inadequate capacity. To improve potable water supply, and so everyone could wash daily, workers drilled wells and overhauled the pipe system. The Germans provided the materials for these improvements, largely to reduce the chance of communicable disease spreading beyond the ghetto, but Jewish engineers directed the projects.

Jews lived in the eleven barracks in the fortress, while civilians continued to inhabit the 218 civilian houses. Segregation between the two groups was strictly enforced and resulted in harsh punishments on Jews who left their barracks. By the end of the year, 7,365 people had been deported to the ghetto, of whom 2,000 were from

The first transport from Theresienstadt left on 9 January 1942 for the Riga Ghetto. It was the only transport whose destination was known to the deportees; other transports simply departed for "the East". The next day, the SS publicly hanged nine men for smuggling letters out of the ghetto, an event that caused widespread outrage and disquiet. The first transports targeted mostly able-bodied people. If one person in a family were selected for a transport, family members would typically volunteer to accompany them, which has been analyzed as an example of family solidarity or social expectations. From June 1942, the SS interned elderly and "prominent" Jews from the Reich at Theresienstadt. Due to the need to accommodate these Jews, the non-Jewish Czechs living in Theresienstadt were expelled, and the town was closed off by the end of June. In May, the self-administration had reduced rations for the elderly in order to increase the food available to hard laborers, as part of its strategy to save as many children and young people as possible to emigrate to Palestine after the war.

101,761 prisoners arrived at Theresienstadt in 1942, causing the population to peak, on 18 September 1942, at 58,491. The death rate also peaked that month with 3,941 deaths. Corpses remained unburied for days and gravediggers carrying coffins through the streets were a regular sight. To alleviate overcrowding, the Germans deported 18,000 mostly elderly people in nine transports in the autumn of 1942. Most of the people deported from Theresienstadt in 1942 were killed immediately, either in the

The first transport from Theresienstadt left on 9 January 1942 for the Riga Ghetto. It was the only transport whose destination was known to the deportees; other transports simply departed for "the East". The next day, the SS publicly hanged nine men for smuggling letters out of the ghetto, an event that caused widespread outrage and disquiet. The first transports targeted mostly able-bodied people. If one person in a family were selected for a transport, family members would typically volunteer to accompany them, which has been analyzed as an example of family solidarity or social expectations. From June 1942, the SS interned elderly and "prominent" Jews from the Reich at Theresienstadt. Due to the need to accommodate these Jews, the non-Jewish Czechs living in Theresienstadt were expelled, and the town was closed off by the end of June. In May, the self-administration had reduced rations for the elderly in order to increase the food available to hard laborers, as part of its strategy to save as many children and young people as possible to emigrate to Palestine after the war.

101,761 prisoners arrived at Theresienstadt in 1942, causing the population to peak, on 18 September 1942, at 58,491. The death rate also peaked that month with 3,941 deaths. Corpses remained unburied for days and gravediggers carrying coffins through the streets were a regular sight. To alleviate overcrowding, the Germans deported 18,000 mostly elderly people in nine transports in the autumn of 1942. Most of the people deported from Theresienstadt in 1942 were killed immediately, either in the

The inmates were also allowed slightly more privileges, including postal correspondence and the right to receive food parcels. On 24 August 1943, 1,200 Jewish children from the Białystok Ghetto in Poland arrived at Theresienstadt. They refused to be disinfected due to their fear that the showers were gas chambers. This incident was one of the only clues as to what happened to those deported from Theresienstadt. The children were held in strict isolation for six weeks before deportation to Auschwitz; none survived. On 9 November 1943, Edelstein and other ghetto administrators were arrested, accused of covering up the escape of fifty-five prisoners. Two days later, commandant

The inmates were also allowed slightly more privileges, including postal correspondence and the right to receive food parcels. On 24 August 1943, 1,200 Jewish children from the Białystok Ghetto in Poland arrived at Theresienstadt. They refused to be disinfected due to their fear that the showers were gas chambers. This incident was one of the only clues as to what happened to those deported from Theresienstadt. The children were held in strict isolation for six weeks before deportation to Auschwitz; none survived. On 9 November 1943, Edelstein and other ghetto administrators were arrested, accused of covering up the escape of fifty-five prisoners. Two days later, commandant

In February 1944, the SS embarked on a "beautification" (german: Verschönerung) campaign to prepare the ghetto for the Red Cross visit. Many "prominent" prisoners and Danish Jews were re-housed in private, superior quarters. The streets were renamed and cleaned; sham shops and a school were set up; the SS encouraged the prisoners to perform an increasing number of cultural activities, which exceeded that of an ordinary town in peacetime. As part of the preparations, 7,503 people were sent to the family camp at Auschwitz in May; the transports targeted sick, elderly, and disabled people who had no place in the ideal Jewish settlement.

For the remaining prisoners conditions improved somewhat: according to one survivor, "The summer of 1944 was the best time we had in Terezín. Nobody thought of new transports." On 23 June 1944, the visitors were led on a tour through the " Potemkin village"; they did not notice anything amiss and the ICRC representative, Maurice Rossel, reported that no one was deported from Theresienstadt. Rabbi Leo Baeck, a spiritual leader at Theresienstadt, stated that "The effect on our morale was devastating. We felt forgotten and forsaken." In August and September, a propaganda film that became known as '' Der Führer schenkt den Juden eine Stadt'' ("The Führer Gives a City to the Jews"), was shot, but it was never distributed.

On 23 September, Eppstein, Zucker, and Murmelstein were told that Theresienstadt's war production was inadequate and as a consequence 5,000 Jews would be deported to a new labor camp run by Zucker. On 27 September, Eppstein was arrested and shot at the Small Fortress for alleged breaches of the law. Murmelstein became Jewish elder and retained the post until the end of the war. The deportation of the majority of the remaining population to Auschwitz—18,401 people in eleven transports—commenced the next day and lasted until 28 October.

Previously, the self-administration had chosen the people to be deported but now the SS made the selections, ensuring that many members of the Jewish Council, ''Aufbaukommando'' workers, and cultural figures were deported and murdered at Auschwitz. The first two transports removed all former

In February 1944, the SS embarked on a "beautification" (german: Verschönerung) campaign to prepare the ghetto for the Red Cross visit. Many "prominent" prisoners and Danish Jews were re-housed in private, superior quarters. The streets were renamed and cleaned; sham shops and a school were set up; the SS encouraged the prisoners to perform an increasing number of cultural activities, which exceeded that of an ordinary town in peacetime. As part of the preparations, 7,503 people were sent to the family camp at Auschwitz in May; the transports targeted sick, elderly, and disabled people who had no place in the ideal Jewish settlement.

For the remaining prisoners conditions improved somewhat: according to one survivor, "The summer of 1944 was the best time we had in Terezín. Nobody thought of new transports." On 23 June 1944, the visitors were led on a tour through the " Potemkin village"; they did not notice anything amiss and the ICRC representative, Maurice Rossel, reported that no one was deported from Theresienstadt. Rabbi Leo Baeck, a spiritual leader at Theresienstadt, stated that "The effect on our morale was devastating. We felt forgotten and forsaken." In August and September, a propaganda film that became known as '' Der Führer schenkt den Juden eine Stadt'' ("The Führer Gives a City to the Jews"), was shot, but it was never distributed.

On 23 September, Eppstein, Zucker, and Murmelstein were told that Theresienstadt's war production was inadequate and as a consequence 5,000 Jews would be deported to a new labor camp run by Zucker. On 27 September, Eppstein was arrested and shot at the Small Fortress for alleged breaches of the law. Murmelstein became Jewish elder and retained the post until the end of the war. The deportation of the majority of the remaining population to Auschwitz—18,401 people in eleven transports—commenced the next day and lasted until 28 October.

Previously, the self-administration had chosen the people to be deported but now the SS made the selections, ensuring that many members of the Jewish Council, ''Aufbaukommando'' workers, and cultural figures were deported and murdered at Auschwitz. The first two transports removed all former

Theresienstadt became the destination of transports as the Nazi concentration camps were evacuated. After transports to Auschwitz had ceased, 416 Slovak Jews were sent from Sereď to Theresienstadt on 23 December 1944; additional transports in 1945 brought the total to 1,447. The Slovak Jews told the Theresienstädters about the fate of those deported to the East, but many refused to believe it. 1,150 Hungarian Jews who had survived a death march to Vienna arrived in March. In 1945, 5,200 Jews living in mixed marriages with "Aryans", who had been previously protected, were deported to Theresienstadt.

On 5 February 1945, after negotiations with Swiss politician

Theresienstadt became the destination of transports as the Nazi concentration camps were evacuated. After transports to Auschwitz had ceased, 416 Slovak Jews were sent from Sereď to Theresienstadt on 23 December 1944; additional transports in 1945 brought the total to 1,447. The Slovak Jews told the Theresienstädters about the fate of those deported to the East, but many refused to believe it. 1,150 Hungarian Jews who had survived a death march to Vienna arrived in March. In 1945, 5,200 Jews living in mixed marriages with "Aryans", who had been previously protected, were deported to Theresienstadt.

On 5 February 1945, after negotiations with Swiss politician  Starting on 20 April, between 13,500 and 15,000 concentration camp prisoners, mostly Jews, arrived at Theresienstadt after surviving death marches from camps about to be liberated by the Allies. The prisoners were in very poor physical and mental shape, and, like the Białystok children, refused disinfection fearing that they would be gassed. They were starving and infected with lice and typhoid fever, an epidemic of which soon raged in the ghetto and claimed many lives. A Theresienstadt prisoner described them as "no longer people, they are wild animals".

The Red Cross took over administration of the ghetto and removed the SS flag on 2 May 1945; the SS fled on 5–6 May. On 8 May, Red Army troops skirmished with German forces outside the ghetto and liberated it at 9 pm. On 11 May, Soviet medical units arrived to take charge of the ghetto; the next day, Jiří Vogel, a Czech Jewish communist, was appointed elder and served until the ghetto was dissolved. Theresienstadt was the only Nazi ghetto liberated with a significant population of survivors. On 14 May, Soviet authorities imposed a strict quarantine to contain the typhoid epidemic; more than 1,500 prisoners and 43 doctors and nurses died around the time of liberation. After two weeks, the quarantine ended and the administration focused on returning survivors to their countries of origin; repatriation continued until 17 August 1945.

Starting on 20 April, between 13,500 and 15,000 concentration camp prisoners, mostly Jews, arrived at Theresienstadt after surviving death marches from camps about to be liberated by the Allies. The prisoners were in very poor physical and mental shape, and, like the Białystok children, refused disinfection fearing that they would be gassed. They were starving and infected with lice and typhoid fever, an epidemic of which soon raged in the ghetto and claimed many lives. A Theresienstadt prisoner described them as "no longer people, they are wild animals".

The Red Cross took over administration of the ghetto and removed the SS flag on 2 May 1945; the SS fled on 5–6 May. On 8 May, Red Army troops skirmished with German forces outside the ghetto and liberated it at 9 pm. On 11 May, Soviet medical units arrived to take charge of the ghetto; the next day, Jiří Vogel, a Czech Jewish communist, was appointed elder and served until the ghetto was dissolved. Theresienstadt was the only Nazi ghetto liberated with a significant population of survivors. On 14 May, Soviet authorities imposed a strict quarantine to contain the typhoid epidemic; more than 1,500 prisoners and 43 doctors and nurses died around the time of liberation. After two weeks, the quarantine ended and the administration focused on returning survivors to their countries of origin; repatriation continued until 17 August 1945.

The economy of Theresienstadt was highly corrupt. Besides the "prominent" prisoners, young Czech Jewish men had the highest status in the ghetto. As the first prisoners in the ghetto (whether in the ''Aufbaukommando'' or through connections to the ''Aufbaukommando'') most of the privileged positions in the ghetto fell to this group. Those in charge of distributing food typically skimmed off the deliveries to save more for themselves or their friends, which heightened the starvation for elderly Jews in particular. The SS also stole deliveries of food intended for prisoners. Many of the functionaries in the Transport Department enriched themselves by accepting bribes. Powerful individuals attempted, and often succeeded, to exempt their friends from deportation, a fact that was noted by prisoners at the time. Because Czech Zionists had a disproportionate influence in the self-administration, they were often able to secure better jobs and exemptions to transport for other Czech Zionists.

The economy of Theresienstadt was highly corrupt. Besides the "prominent" prisoners, young Czech Jewish men had the highest status in the ghetto. As the first prisoners in the ghetto (whether in the ''Aufbaukommando'' or through connections to the ''Aufbaukommando'') most of the privileged positions in the ghetto fell to this group. Those in charge of distributing food typically skimmed off the deliveries to save more for themselves or their friends, which heightened the starvation for elderly Jews in particular. The SS also stole deliveries of food intended for prisoners. Many of the functionaries in the Transport Department enriched themselves by accepting bribes. Powerful individuals attempted, and often succeeded, to exempt their friends from deportation, a fact that was noted by prisoners at the time. Because Czech Zionists had a disproportionate influence in the self-administration, they were often able to secure better jobs and exemptions to transport for other Czech Zionists.

Over the lifetime of the ghetto, about 15,000 children lived in Theresienstadt, of whom about 90% perished after deportation. The Youth Welfare Office (german: Jugendfürsorge) was responsible for their housing, care, and education. Before June 1942, when the Czech civilians were evicted from the town, children lived with their parents in the barracks and were left unsupervised during the day. After the eviction, some of the houses were taken over by the Youth Welfare Office for use as children's homes. The intention was to keep the children somewhat insulated from the harsh conditions in the ghetto so that they would not succumb to "demoralization". Aided by teachers and helpers recruited from former educators and students, the children lived in collectives of 200–300 per house, separated by language. Within each house, children were assigned to rooms by gender and age. Their housing was superior to that of other inmates and they were also better fed.

The leadership of the Youth Welfare Office, including its head, , and Redlich's deputy Fredy Hirsch, were Labor Zionism, left-wing Zionists with a background in the Zionist youth movements, youth movements. However, Redlich agreed that a good-quality non-Zionist education was preferred to a bad Zionist one. Because of this, the ideological quality of education depended on the inclination of the person who ran the home; this was formalized in a 1943 agreement. According to historian Anna Hájková, Zionists regarded the youth homes as hakhshara (preparation) for future life on a kibbutz in Palestine; Rothkirchen argues that the intentional community of the children's homes resembled kibbutzim. Different educators used Jewish assimilation, assimilationism, Communism, or Zionism as the basis of their educational philosophies; Communist philosophy increased after the Red Army's military victories on the Eastern Front (World War II), Eastern Front in 1943 and 1944.

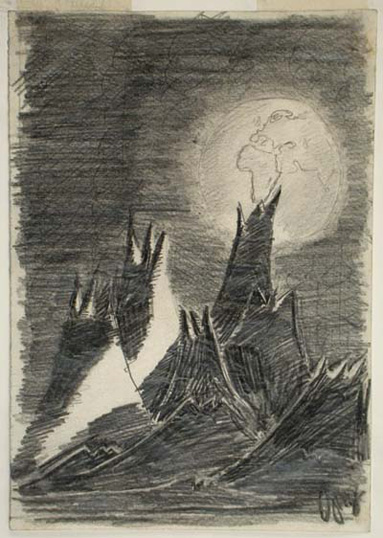

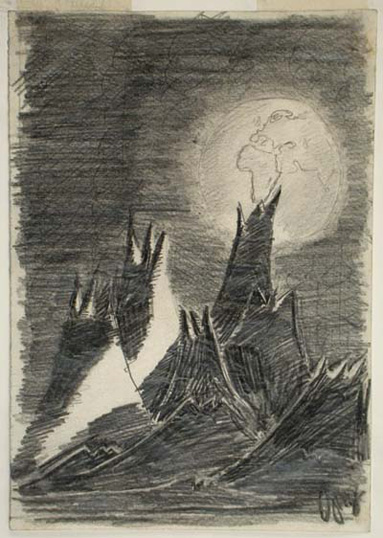

Although education was forbidden, the teachers continued to clandestinely teach general education subjects including Czech, German, history, geography, and mathematics. Study of the Hebrew language was mandatory despite the increased danger to educators if they were caught. Children also participated in cultural activities in the evenings after their lessons. Many of the children's homes produced magazines, of which the best known is ''Vedem'' from Home One (L417). Hundreds of children made drawings under the guidance of the Viennese art therapist Friedl Dicker-Brandeis. According to Rothkirchen, caring for the children was the self-administration's greatest achievement and the drawings left by children were Theresienstadt's "most precious legacy".

Over the lifetime of the ghetto, about 15,000 children lived in Theresienstadt, of whom about 90% perished after deportation. The Youth Welfare Office (german: Jugendfürsorge) was responsible for their housing, care, and education. Before June 1942, when the Czech civilians were evicted from the town, children lived with their parents in the barracks and were left unsupervised during the day. After the eviction, some of the houses were taken over by the Youth Welfare Office for use as children's homes. The intention was to keep the children somewhat insulated from the harsh conditions in the ghetto so that they would not succumb to "demoralization". Aided by teachers and helpers recruited from former educators and students, the children lived in collectives of 200–300 per house, separated by language. Within each house, children were assigned to rooms by gender and age. Their housing was superior to that of other inmates and they were also better fed.

The leadership of the Youth Welfare Office, including its head, , and Redlich's deputy Fredy Hirsch, were Labor Zionism, left-wing Zionists with a background in the Zionist youth movements, youth movements. However, Redlich agreed that a good-quality non-Zionist education was preferred to a bad Zionist one. Because of this, the ideological quality of education depended on the inclination of the person who ran the home; this was formalized in a 1943 agreement. According to historian Anna Hájková, Zionists regarded the youth homes as hakhshara (preparation) for future life on a kibbutz in Palestine; Rothkirchen argues that the intentional community of the children's homes resembled kibbutzim. Different educators used Jewish assimilation, assimilationism, Communism, or Zionism as the basis of their educational philosophies; Communist philosophy increased after the Red Army's military victories on the Eastern Front (World War II), Eastern Front in 1943 and 1944.

Although education was forbidden, the teachers continued to clandestinely teach general education subjects including Czech, German, history, geography, and mathematics. Study of the Hebrew language was mandatory despite the increased danger to educators if they were caught. Children also participated in cultural activities in the evenings after their lessons. Many of the children's homes produced magazines, of which the best known is ''Vedem'' from Home One (L417). Hundreds of children made drawings under the guidance of the Viennese art therapist Friedl Dicker-Brandeis. According to Rothkirchen, caring for the children was the self-administration's greatest achievement and the drawings left by children were Theresienstadt's "most precious legacy".

Theresienstadt was characterized by a rich cultural life, especially in 1943 and 1944, which greatly exceeded that in other Nazi concentration camps and ghettos. The inmates were free from the usual rules of Nazi censorship and the ban on "degenerate art". The origins began in the spontaneous "friendship evenings" organized by the first prisoners in December 1941; many promising artists had arrived in the ''Aufbaukommando'' transports, including the musicians Karel Švenk, Rafael Schächter, and Gideon Klein. Švenk's "Terezín March" became the unofficial anthem for the ghetto. Later, the activities were sponsored by the self-administration and organized by the ''Freizeitgestaltung'' ("Free Time Department", FZG), led by Otto Zucker. Zucker's department had a wide variety of artists to choose from. Although most performers had to work full-time at other jobs in addition to their creative activity, a few were hired by the FZG. However, the FZG was unusually effective at exempting performers from deportation. Because women were expected to take care of domestic chores in addition to full-time work and men were appointed as the conductors and directors who selected performers, very few women were able to participate in cultural life. Official efforts to improve the quality of performances increased during the "beautification" process that began in December 1943.

Many musicians performed at the ghetto. Karel Ančerl conducted an orchestra composed largely of professional musicians. Karl Fischer, a Moravian cantor, led various choirs. The Ghetto Swingers performed jazz music, and Viktor Ullmann composed more than 20 works while imprisoned at Theresienstadt, including the opera ''Der Kaiser von Atlantis''. The children's opera ''Brundibár'', composed in 1938 by Hans Krása, was first performed at Theresienstadt on 23 September 1943. A hit, it was performed 55 times (about once a week) until the transports of autumn 1944. The work of the musicians was exploited by the Nazis in the two propaganda films made in the ghetto. Only the social elite could get tickets for events, and attending musical and theatrical performances became a status symbol.

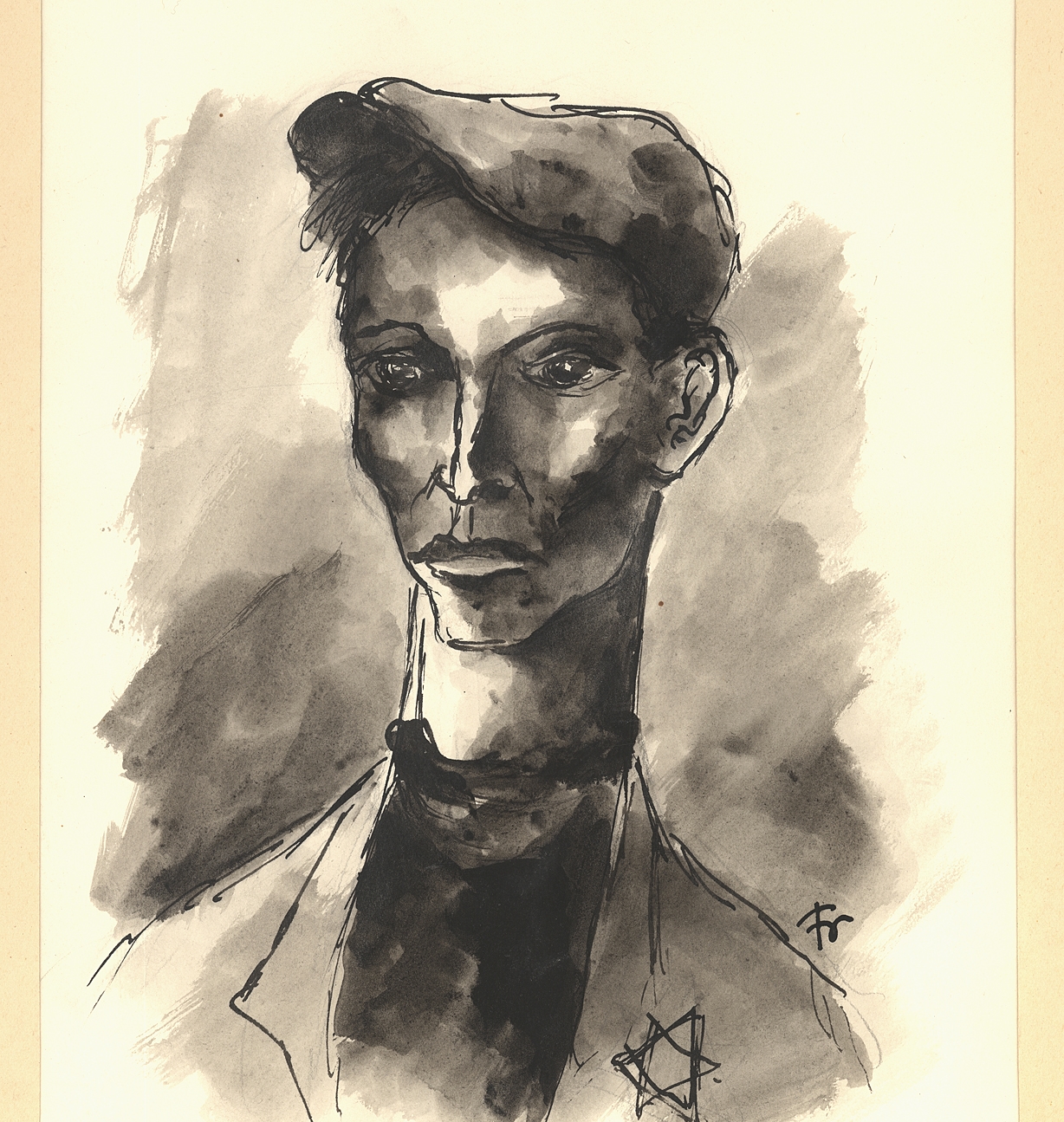

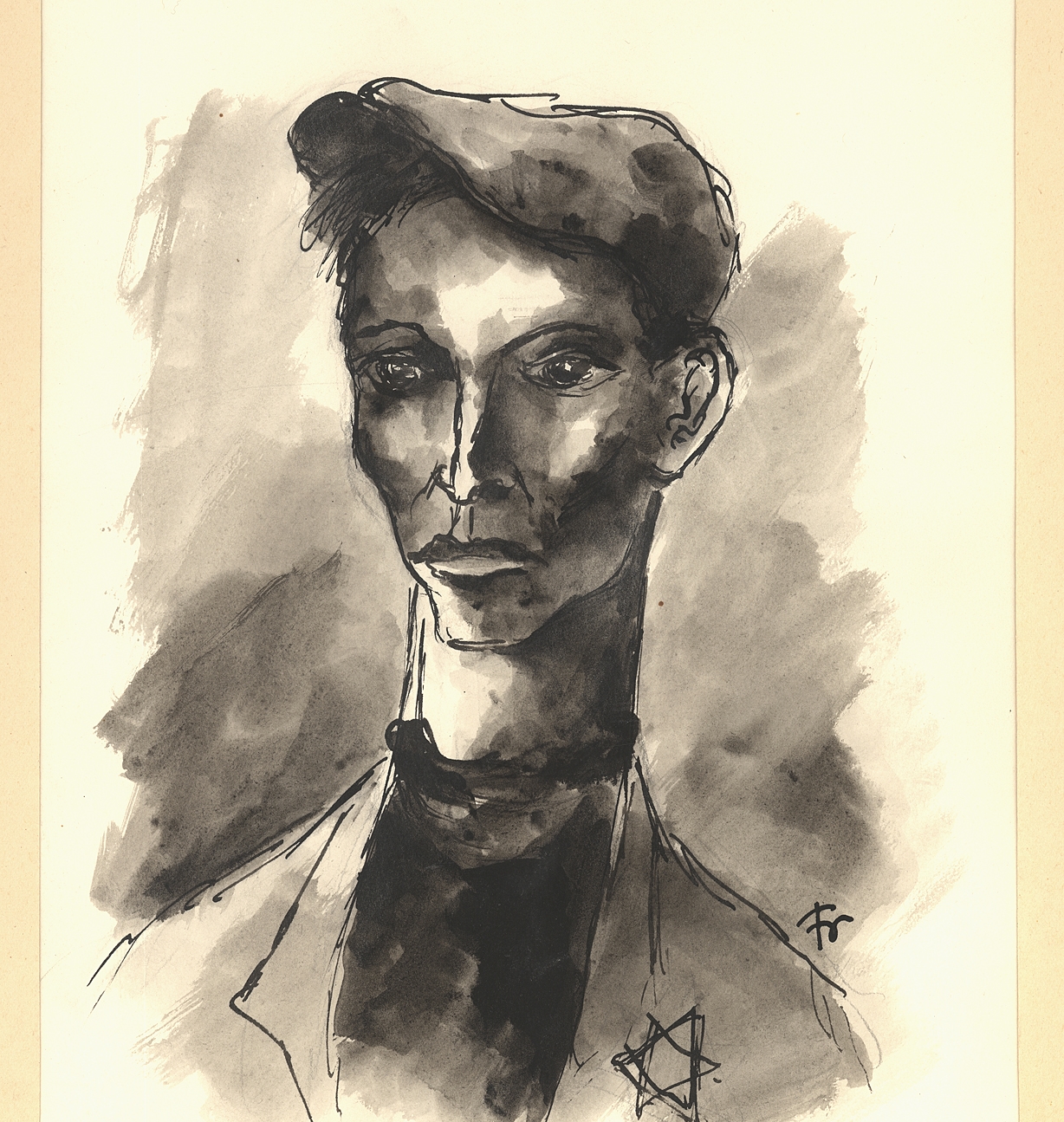

The visual arts were developed by a circle of artists, including Bedřich Fritta, Norbert Troller, Leo Haas, Otto Ungar, and Petr Kien, who were officially employed by the Arts Department of the self-administration to create drawings and graphs of work at Theresienstadt on the orders of the SS. The artists, however, depicted the ghetto's actual conditions in their spare time. Several of these artists were caught smuggling their work out of the ghetto. Accused of "atrocity propaganda", they were arrested on 20 July 1944 and tortured at the Small Fortress. Much of their artwork was not rediscovered until many years later, but has been a useful tool for historians to glimpse the ghetto elite as well the widespread misery in the ghetto.

The Ghetto Central Library opened in November 1942 and contained 60,000 books and 15 full-time librarians by the end of 1943. As head of the library, the Central Secretariat appointed the philosopher Emil Utitz, who individually approved borrowers. It eventually grew to over 100,000 volumes from Jewish libraries all over Europe or brought by prisoners to the ghetto. The library was criticized for the high proportion of Hebrew-language works and the lack of fiction, but prisoners were desperate for any kind of reading material. At least 2,309 lectures were delivered in the ghetto, on a variety of subjects including Judaism, Zionism, art, music, science, and economics, by 489 different people, leading the ghetto to be described as an "open university".

Theresienstadt was characterized by a rich cultural life, especially in 1943 and 1944, which greatly exceeded that in other Nazi concentration camps and ghettos. The inmates were free from the usual rules of Nazi censorship and the ban on "degenerate art". The origins began in the spontaneous "friendship evenings" organized by the first prisoners in December 1941; many promising artists had arrived in the ''Aufbaukommando'' transports, including the musicians Karel Švenk, Rafael Schächter, and Gideon Klein. Švenk's "Terezín March" became the unofficial anthem for the ghetto. Later, the activities were sponsored by the self-administration and organized by the ''Freizeitgestaltung'' ("Free Time Department", FZG), led by Otto Zucker. Zucker's department had a wide variety of artists to choose from. Although most performers had to work full-time at other jobs in addition to their creative activity, a few were hired by the FZG. However, the FZG was unusually effective at exempting performers from deportation. Because women were expected to take care of domestic chores in addition to full-time work and men were appointed as the conductors and directors who selected performers, very few women were able to participate in cultural life. Official efforts to improve the quality of performances increased during the "beautification" process that began in December 1943.

Many musicians performed at the ghetto. Karel Ančerl conducted an orchestra composed largely of professional musicians. Karl Fischer, a Moravian cantor, led various choirs. The Ghetto Swingers performed jazz music, and Viktor Ullmann composed more than 20 works while imprisoned at Theresienstadt, including the opera ''Der Kaiser von Atlantis''. The children's opera ''Brundibár'', composed in 1938 by Hans Krása, was first performed at Theresienstadt on 23 September 1943. A hit, it was performed 55 times (about once a week) until the transports of autumn 1944. The work of the musicians was exploited by the Nazis in the two propaganda films made in the ghetto. Only the social elite could get tickets for events, and attending musical and theatrical performances became a status symbol.

The visual arts were developed by a circle of artists, including Bedřich Fritta, Norbert Troller, Leo Haas, Otto Ungar, and Petr Kien, who were officially employed by the Arts Department of the self-administration to create drawings and graphs of work at Theresienstadt on the orders of the SS. The artists, however, depicted the ghetto's actual conditions in their spare time. Several of these artists were caught smuggling their work out of the ghetto. Accused of "atrocity propaganda", they were arrested on 20 July 1944 and tortured at the Small Fortress. Much of their artwork was not rediscovered until many years later, but has been a useful tool for historians to glimpse the ghetto elite as well the widespread misery in the ghetto.

The Ghetto Central Library opened in November 1942 and contained 60,000 books and 15 full-time librarians by the end of 1943. As head of the library, the Central Secretariat appointed the philosopher Emil Utitz, who individually approved borrowers. It eventually grew to over 100,000 volumes from Jewish libraries all over Europe or brought by prisoners to the ghetto. The library was criticized for the high proportion of Hebrew-language works and the lack of fiction, but prisoners were desperate for any kind of reading material. At least 2,309 lectures were delivered in the ghetto, on a variety of subjects including Judaism, Zionism, art, music, science, and economics, by 489 different people, leading the ghetto to be described as an "open university".

Theresienstadt was the only Nazi concentration center where religious observance was not banned. Although they were all Jewish according to the Nuremberg Laws, deportees came from a wide variety of strains of Judaism and Christianity; others were atheists. Some communities and individuals, particularly from Moravia, brought their Torah scrolls, Shofar, tefillin, and other religious items with them to the ghetto. Edelstein, who was religious, appointed a team of rabbis to oversee the burial of the dead. The believers, who were largely elderly Jews from Austria and Germany, frequently gathered in makeshift areas to pray on Shabbat. Rabbis and Leo Baeck ministered not just to Jews but to Christian converts and others needing comfort.

Theresienstadt's cultural life has been viewed differently by different prisoners and commentators. Adler stresses that an unusually high number of inmates were culturally active; however, cultural activity could lead to a kind of self-deception about reality. Ullmann believed that the activities represented spiritual resistance to Nazism and a "spark of humanity": "By no means did we Psalm 137, sit weeping by the rivers of Babylon; our endeavors in the arts were commensurate with our will to live."

Theresienstadt was the only Nazi concentration center where religious observance was not banned. Although they were all Jewish according to the Nuremberg Laws, deportees came from a wide variety of strains of Judaism and Christianity; others were atheists. Some communities and individuals, particularly from Moravia, brought their Torah scrolls, Shofar, tefillin, and other religious items with them to the ghetto. Edelstein, who was religious, appointed a team of rabbis to oversee the burial of the dead. The believers, who were largely elderly Jews from Austria and Germany, frequently gathered in makeshift areas to pray on Shabbat. Rabbis and Leo Baeck ministered not just to Jews but to Christian converts and others needing comfort.

Theresienstadt's cultural life has been viewed differently by different prisoners and commentators. Adler stresses that an unusually high number of inmates were culturally active; however, cultural activity could lead to a kind of self-deception about reality. Ullmann believed that the activities represented spiritual resistance to Nazism and a "spark of humanity": "By no means did we Psalm 137, sit weeping by the rivers of Babylon; our endeavors in the arts were commensurate with our will to live."

Approximately 141,000 Jews, mostly from the Protectorate, Germany, and Austria, were sent to Theresienstadt before 20 April 1945. The majority came from just five cities: Prague (40,000), Vienna (15,000), Berlin (13,500), Brno (9,000), and Frankfurt (4,000). Between 13,500 and 15,000 survivors of death marches arrived after that date, including some 500 people who were at Theresienstadt twice, which brought the total to 154,000. Before 20 April, 33,521 people died at Theresienstadt, and an additional 1,567 people died between 20 April and 30 June. 88,196 people were deported from Theresienstadt between 9 January 1942 and 28 October 1944. Of prisoners who arrived before 20 April, 17,320 were liberated at Theresienstadt, about 4,000 survived deportation, and 1,630 were rescued before the end of the war. In all, there were about 23,000 survivors.

A further 239 people were transferred to the Small Fortress before 12 October 1944; most were murdered there. 37 others were taken by the Gestapo on 20 February 1945. Before 1945, 37 people escaped, and twelve were recaptured and returned to Theresienstadt; according to Adler it is unlikely that most of the remainder were successful. A further 92 people escaped in early 1945 and 547 departed by their own unauthorized action after the departure of the SS on 5 May.

Approximately 141,000 Jews, mostly from the Protectorate, Germany, and Austria, were sent to Theresienstadt before 20 April 1945. The majority came from just five cities: Prague (40,000), Vienna (15,000), Berlin (13,500), Brno (9,000), and Frankfurt (4,000). Between 13,500 and 15,000 survivors of death marches arrived after that date, including some 500 people who were at Theresienstadt twice, which brought the total to 154,000. Before 20 April, 33,521 people died at Theresienstadt, and an additional 1,567 people died between 20 April and 30 June. 88,196 people were deported from Theresienstadt between 9 January 1942 and 28 October 1944. Of prisoners who arrived before 20 April, 17,320 were liberated at Theresienstadt, about 4,000 survived deportation, and 1,630 were rescued before the end of the war. In all, there were about 23,000 survivors.

A further 239 people were transferred to the Small Fortress before 12 October 1944; most were murdered there. 37 others were taken by the Gestapo on 20 February 1945. Before 1945, 37 people escaped, and twelve were recaptured and returned to Theresienstadt; according to Adler it is unlikely that most of the remainder were successful. A further 92 people escaped in early 1945 and 547 departed by their own unauthorized action after the departure of the SS on 5 May.

In 1947, it was decided to convert the Small Fortress into a memorial to the victims of Nazi persecution. Adler rescued a large number of documents and paintings from Theresienstadt after the war and lodged them with the Jewish Museum in Prague; this material formed the bedrock of the collections now held at the Jewish Museum in Prague and in Theresienstadt itself. However, the Jewish legacy was not recognized in the post-war era because it did not fit into the Soviet ideology of class struggle promoted in the postwar Czechoslovak Socialist Republic, and discredited the official position of Soviet Anti-Zionism, anti-Zionism (exemplified by the 1952 Slánský trial and intensified following the 1967 Six-Day War). Although there were memorial plaques in the former ghetto, none mentioned Jews.

The Terezín Ghetto Museum was inaugurated in October 1991, after the Velvet Revolution ended Communist rule in Czechoslovakia, as part of the fiftieth anniversary commemorations of the former ghetto. The museum is funded by the Czech Ministry of Culture and includes a section devoted to researching the history of Theresienstadt. In 2001, the director reported that about 250,000 people visit Theresienstadt every year; prominent visitors have included the President of Germany, German presidents Richard von Weizsäcker and Roman Herzog, President of Israel, Israeli presidents Chaim Herzog and Ezer Weizmann, as well as Václav Havel, the President of the Czech Republic. In 2015, former United States Secretary of State (United States), Secretary of State Madeleine Albright unveiled a plaque at the former ghetto commemorating her 26 relatives who had been imprisoned there.

In 1947, it was decided to convert the Small Fortress into a memorial to the victims of Nazi persecution. Adler rescued a large number of documents and paintings from Theresienstadt after the war and lodged them with the Jewish Museum in Prague; this material formed the bedrock of the collections now held at the Jewish Museum in Prague and in Theresienstadt itself. However, the Jewish legacy was not recognized in the post-war era because it did not fit into the Soviet ideology of class struggle promoted in the postwar Czechoslovak Socialist Republic, and discredited the official position of Soviet Anti-Zionism, anti-Zionism (exemplified by the 1952 Slánský trial and intensified following the 1967 Six-Day War). Although there were memorial plaques in the former ghetto, none mentioned Jews.

The Terezín Ghetto Museum was inaugurated in October 1991, after the Velvet Revolution ended Communist rule in Czechoslovakia, as part of the fiftieth anniversary commemorations of the former ghetto. The museum is funded by the Czech Ministry of Culture and includes a section devoted to researching the history of Theresienstadt. In 2001, the director reported that about 250,000 people visit Theresienstadt every year; prominent visitors have included the President of Germany, German presidents Richard von Weizsäcker and Roman Herzog, President of Israel, Israeli presidents Chaim Herzog and Ezer Weizmann, as well as Václav Havel, the President of the Czech Republic. In 2015, former United States Secretary of State (United States), Secretary of State Madeleine Albright unveiled a plaque at the former ghetto commemorating her 26 relatives who had been imprisoned there.

online version

paginated 1–11. * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum image gallery for Theresienstadt

{{good article Theresienstadt Ghetto, Litoměřice District Jewish Austrian history Jewish Danish history Jewish Dutch history Buildings and structures in the Ústí nad Labem Region The Holocaust in Bohemia and Moravia Ghettos in Nazi-occupied Europe

History

1941

On 24 November 1941, the first trainload of deportees arrived at the Sudeten barracks in Theresienstadt; they were 342 young Jewish men whose task was to prepare the town for the arrival of thousands of other Jews beginning 30 November. Another transport of 1,000 men arrived on 4 December; this included Jakob Edelstein and the original members of the Council of Elders. Deportees to the ghetto had to surrender all possessions except for of luggage, which they had to carry with them from the railway station at Bauschowitz (Bohušovice), away; the walk was difficult for elderly and ill Jews, many of whom died on the journey. After arriving, prisoners were sent to the ( en, sluice), where they were registered and deprived of their remaining possessions.

The 24 November and 4 December transports, consisting mostly of Jewish craftsmen, engineers, and other skilled workers of Zionist sympathies, were known as the '' Aufbaukommando'' (Work Detail) and their members were exempt from deportation until September 1943. The members of the ''Aufbaukommando'' used creative methods to improve the infrastructure of the ghetto and prepare it to house an average of 40,000 people during its existence. The construction project was funded by stolen Jewish property. When the first transport arrived, there was only one vat for coffee with a capacity of ; by the next year, there were sufficient kettles to make 50,000 cups of ersatz coffee in two hours. The waterworks often broke down during the first months due to inadequate capacity. To improve potable water supply, and so everyone could wash daily, workers drilled wells and overhauled the pipe system. The Germans provided the materials for these improvements, largely to reduce the chance of communicable disease spreading beyond the ghetto, but Jewish engineers directed the projects.

Jews lived in the eleven barracks in the fortress, while civilians continued to inhabit the 218 civilian houses. Segregation between the two groups was strictly enforced and resulted in harsh punishments on Jews who left their barracks. By the end of the year, 7,365 people had been deported to the ghetto, of whom 2,000 were from

On 24 November 1941, the first trainload of deportees arrived at the Sudeten barracks in Theresienstadt; they were 342 young Jewish men whose task was to prepare the town for the arrival of thousands of other Jews beginning 30 November. Another transport of 1,000 men arrived on 4 December; this included Jakob Edelstein and the original members of the Council of Elders. Deportees to the ghetto had to surrender all possessions except for of luggage, which they had to carry with them from the railway station at Bauschowitz (Bohušovice), away; the walk was difficult for elderly and ill Jews, many of whom died on the journey. After arriving, prisoners were sent to the ( en, sluice), where they were registered and deprived of their remaining possessions.

The 24 November and 4 December transports, consisting mostly of Jewish craftsmen, engineers, and other skilled workers of Zionist sympathies, were known as the '' Aufbaukommando'' (Work Detail) and their members were exempt from deportation until September 1943. The members of the ''Aufbaukommando'' used creative methods to improve the infrastructure of the ghetto and prepare it to house an average of 40,000 people during its existence. The construction project was funded by stolen Jewish property. When the first transport arrived, there was only one vat for coffee with a capacity of ; by the next year, there were sufficient kettles to make 50,000 cups of ersatz coffee in two hours. The waterworks often broke down during the first months due to inadequate capacity. To improve potable water supply, and so everyone could wash daily, workers drilled wells and overhauled the pipe system. The Germans provided the materials for these improvements, largely to reduce the chance of communicable disease spreading beyond the ghetto, but Jewish engineers directed the projects.

Jews lived in the eleven barracks in the fortress, while civilians continued to inhabit the 218 civilian houses. Segregation between the two groups was strictly enforced and resulted in harsh punishments on Jews who left their barracks. By the end of the year, 7,365 people had been deported to the ghetto, of whom 2,000 were from Brno

Brno ( , ; german: Brünn ) is a city in the South Moravian Region of the Czech Republic. Located at the confluence of the Svitava and Svratka rivers, Brno has about 380,000 inhabitants, making it the second-largest city in the Czech Republic ...

and the rest from Prague.

1942

The first transport from Theresienstadt left on 9 January 1942 for the Riga Ghetto. It was the only transport whose destination was known to the deportees; other transports simply departed for "the East". The next day, the SS publicly hanged nine men for smuggling letters out of the ghetto, an event that caused widespread outrage and disquiet. The first transports targeted mostly able-bodied people. If one person in a family were selected for a transport, family members would typically volunteer to accompany them, which has been analyzed as an example of family solidarity or social expectations. From June 1942, the SS interned elderly and "prominent" Jews from the Reich at Theresienstadt. Due to the need to accommodate these Jews, the non-Jewish Czechs living in Theresienstadt were expelled, and the town was closed off by the end of June. In May, the self-administration had reduced rations for the elderly in order to increase the food available to hard laborers, as part of its strategy to save as many children and young people as possible to emigrate to Palestine after the war.

101,761 prisoners arrived at Theresienstadt in 1942, causing the population to peak, on 18 September 1942, at 58,491. The death rate also peaked that month with 3,941 deaths. Corpses remained unburied for days and gravediggers carrying coffins through the streets were a regular sight. To alleviate overcrowding, the Germans deported 18,000 mostly elderly people in nine transports in the autumn of 1942. Most of the people deported from Theresienstadt in 1942 were killed immediately, either in the

The first transport from Theresienstadt left on 9 January 1942 for the Riga Ghetto. It was the only transport whose destination was known to the deportees; other transports simply departed for "the East". The next day, the SS publicly hanged nine men for smuggling letters out of the ghetto, an event that caused widespread outrage and disquiet. The first transports targeted mostly able-bodied people. If one person in a family were selected for a transport, family members would typically volunteer to accompany them, which has been analyzed as an example of family solidarity or social expectations. From June 1942, the SS interned elderly and "prominent" Jews from the Reich at Theresienstadt. Due to the need to accommodate these Jews, the non-Jewish Czechs living in Theresienstadt were expelled, and the town was closed off by the end of June. In May, the self-administration had reduced rations for the elderly in order to increase the food available to hard laborers, as part of its strategy to save as many children and young people as possible to emigrate to Palestine after the war.

101,761 prisoners arrived at Theresienstadt in 1942, causing the population to peak, on 18 September 1942, at 58,491. The death rate also peaked that month with 3,941 deaths. Corpses remained unburied for days and gravediggers carrying coffins through the streets were a regular sight. To alleviate overcrowding, the Germans deported 18,000 mostly elderly people in nine transports in the autumn of 1942. Most of the people deported from Theresienstadt in 1942 were killed immediately, either in the Operation Reinhard

or ''Einsatz Reinhard''

, location = Occupied Poland

, date = October 1941 – November 1943

, incident_type = Mass deportations to extermination camps

, perpetrators = Odilo Globočnik, Hermann Höfle, Richard Thomalla, Erwin L ...

death camps

Nazi Germany used six extermination camps (german: Vernichtungslager), also called death camps (), or killing centers (), in Central Europe during World War II to systematically murder over 2.7 million peoplemostly Jewsin the Holocaust. The v ...

or at mass execution sites in the Baltic States and Belarus, such as Kalevi-Liiva

Kalevi-Liiva are sand dunes in Jõelähtme Parish in Harju County, Estonia. The site is located near the Baltic coast, north of the Jägala, Estonia, Jägala village and the former Jägala concentration camp. It is best known as the execution sit ...

and Maly Trostenets

Maly Trostenets (Maly Trascianiec, , "Little Trostenets") is a village near Minsk in Belarus, formerly the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic. During Nazi Germany's occupation of the area during World War II (when the Germans referred to it ...

. Many transports have no known survivors. The Germans selected a small number of healthy young people for forced labor. In all, 42,000 people, mostly Czech Jews, were deported from Theresienstadt in 1942, of whom only 356 survivors are known.

1943

In January, seven thousand people were deported toAuschwitz concentration camp

Auschwitz concentration camp ( (); also or ) was a complex of over 40 concentration and extermination camps operated by Nazi Germany in occupied Poland (in a portion annexed into Germany in 1939) during World War II and the Holocaust. It con ...

. During the same month, the Jewish community leaders from Berlin and Vienna arrived, and the leadership was reorganized to include Paul Eppstein

Paul Maximilian Eppstein (born 4 March 1902 in Ludwigshafen am Rhein; died 27 or 28 September 1944 in the Little Fortress of Theresienstadt) was a German sociologist, Zionist and elder in the Theresienstadt ghetto.

Life

Paul Eppstein was the son ...

, a German Zionist, and Benjamin Murmelstein

Benjamin Israel Murmelstein (9 June 1905 – 27 October 1989) was an Austrian rabbi. He was one of 17 community rabbis in Vienna in 1938 and the only one remaining in Vienna by late 1939. An important figure and board member of the Jewish group i ...

, an Austrian rabbi; Edelstein was forced to act as Eppstein's deputy. At the beginning of February, Ernst Kaltenbrunner

Ernst Kaltenbrunner (4 October 190316 October 1946) was a high-ranking Austrian SS official during the Nazi era and a major perpetrator of the Holocaust. After the assassination of Reinhard Heydrich in 1942, and a brief period under Heinrich ...

, head of the RSHA, proposed the deportation of an additional five thousand elderly Jews. SS chief Heinrich Himmler refused, due to the increasing need for Theresienstadt as an alibi to conceal information on the Holocaust reaching the Western Allies. There were no more transports from Theresienstadt until the deportation of 5,000 Jews to the Theresienstadt family camp at Auschwitz in September.

The inmates were also allowed slightly more privileges, including postal correspondence and the right to receive food parcels. On 24 August 1943, 1,200 Jewish children from the Białystok Ghetto in Poland arrived at Theresienstadt. They refused to be disinfected due to their fear that the showers were gas chambers. This incident was one of the only clues as to what happened to those deported from Theresienstadt. The children were held in strict isolation for six weeks before deportation to Auschwitz; none survived. On 9 November 1943, Edelstein and other ghetto administrators were arrested, accused of covering up the escape of fifty-five prisoners. Two days later, commandant

The inmates were also allowed slightly more privileges, including postal correspondence and the right to receive food parcels. On 24 August 1943, 1,200 Jewish children from the Białystok Ghetto in Poland arrived at Theresienstadt. They refused to be disinfected due to their fear that the showers were gas chambers. This incident was one of the only clues as to what happened to those deported from Theresienstadt. The children were held in strict isolation for six weeks before deportation to Auschwitz; none survived. On 9 November 1943, Edelstein and other ghetto administrators were arrested, accused of covering up the escape of fifty-five prisoners. Two days later, commandant Anton Burger

Anton "Toni" Burger (19 November 1911 – 25 December 1991) was a (Captain) in the German Nazi SS, in Greece (1944) and of Theresienstadt concentration camp.

Military career

Anton Burger was born in Neunkirchen, Austria, the son of a station ...

ordered a census of the entire ghetto population, approximately 36,000 people at that time. All inmates, regardless of age, were required to stand outside in freezing weather from 7 am to 11 pm; 300 people died on the field from exhaustion. Five thousand prisoners, including Edelstein and the other arrested leaders, were sent to the family camp at Auschwitz on 15 and 18 December.

293 Jews arrived at Theresienstadt from Westerbork (in the Netherlands) in April 1943, but the rest of the 4,894 Jews eventually deported from Westerbork to Theresienstadt arrived during 1944. 450 Jews from Denmark—the few who had not escaped to Sweden—arrived in October 1943. The Danish government's inquiries after them prevented their deportation, and eventually the SS authorized representatives of the Danish Red Cross and the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) to visit Theresienstadt. The RSHA archives were transported to Theresienstadt in July 1943, reducing the space for prisoners, and stored in the Sudeten barracks until they were burned on 17 April 1945 on SS orders.

1944

In February 1944, the SS embarked on a "beautification" (german: Verschönerung) campaign to prepare the ghetto for the Red Cross visit. Many "prominent" prisoners and Danish Jews were re-housed in private, superior quarters. The streets were renamed and cleaned; sham shops and a school were set up; the SS encouraged the prisoners to perform an increasing number of cultural activities, which exceeded that of an ordinary town in peacetime. As part of the preparations, 7,503 people were sent to the family camp at Auschwitz in May; the transports targeted sick, elderly, and disabled people who had no place in the ideal Jewish settlement.

For the remaining prisoners conditions improved somewhat: according to one survivor, "The summer of 1944 was the best time we had in Terezín. Nobody thought of new transports." On 23 June 1944, the visitors were led on a tour through the " Potemkin village"; they did not notice anything amiss and the ICRC representative, Maurice Rossel, reported that no one was deported from Theresienstadt. Rabbi Leo Baeck, a spiritual leader at Theresienstadt, stated that "The effect on our morale was devastating. We felt forgotten and forsaken." In August and September, a propaganda film that became known as '' Der Führer schenkt den Juden eine Stadt'' ("The Führer Gives a City to the Jews"), was shot, but it was never distributed.

On 23 September, Eppstein, Zucker, and Murmelstein were told that Theresienstadt's war production was inadequate and as a consequence 5,000 Jews would be deported to a new labor camp run by Zucker. On 27 September, Eppstein was arrested and shot at the Small Fortress for alleged breaches of the law. Murmelstein became Jewish elder and retained the post until the end of the war. The deportation of the majority of the remaining population to Auschwitz—18,401 people in eleven transports—commenced the next day and lasted until 28 October.

Previously, the self-administration had chosen the people to be deported but now the SS made the selections, ensuring that many members of the Jewish Council, ''Aufbaukommando'' workers, and cultural figures were deported and murdered at Auschwitz. The first two transports removed all former

In February 1944, the SS embarked on a "beautification" (german: Verschönerung) campaign to prepare the ghetto for the Red Cross visit. Many "prominent" prisoners and Danish Jews were re-housed in private, superior quarters. The streets were renamed and cleaned; sham shops and a school were set up; the SS encouraged the prisoners to perform an increasing number of cultural activities, which exceeded that of an ordinary town in peacetime. As part of the preparations, 7,503 people were sent to the family camp at Auschwitz in May; the transports targeted sick, elderly, and disabled people who had no place in the ideal Jewish settlement.

For the remaining prisoners conditions improved somewhat: according to one survivor, "The summer of 1944 was the best time we had in Terezín. Nobody thought of new transports." On 23 June 1944, the visitors were led on a tour through the " Potemkin village"; they did not notice anything amiss and the ICRC representative, Maurice Rossel, reported that no one was deported from Theresienstadt. Rabbi Leo Baeck, a spiritual leader at Theresienstadt, stated that "The effect on our morale was devastating. We felt forgotten and forsaken." In August and September, a propaganda film that became known as '' Der Führer schenkt den Juden eine Stadt'' ("The Führer Gives a City to the Jews"), was shot, but it was never distributed.

On 23 September, Eppstein, Zucker, and Murmelstein were told that Theresienstadt's war production was inadequate and as a consequence 5,000 Jews would be deported to a new labor camp run by Zucker. On 27 September, Eppstein was arrested and shot at the Small Fortress for alleged breaches of the law. Murmelstein became Jewish elder and retained the post until the end of the war. The deportation of the majority of the remaining population to Auschwitz—18,401 people in eleven transports—commenced the next day and lasted until 28 October.

Previously, the self-administration had chosen the people to be deported but now the SS made the selections, ensuring that many members of the Jewish Council, ''Aufbaukommando'' workers, and cultural figures were deported and murdered at Auschwitz. The first two transports removed all former Czechoslovak Army

The Czechoslovak Army (Czech and Slovak: Československá armáda) was the name of the armed forces of Czechoslovakia. It was established in 1918 following Czechoslovakia's declaration of independence from Austria-Hungary.

History

In the fi ...

officers, who were thought to be a threat for causing an uprising at Theresienstadt. By November, only 11,000 people were left at Theresienstadt, most of them elderly; 70% were female. That month, the ashes of deceased prisoners were removed by women and children. The remains of 17,000 people were dumped in the Eger River

Eger ( , ; ; also known by other alternative names) is the county seat of Heves County, and the second largest city in Northern Hungary (after Miskolc). A city with county rights. Eger is best known for its castle, thermal baths, baroque ...

and the remainder of the ashes were buried in pits near Leitmeritz.

1945

Theresienstadt became the destination of transports as the Nazi concentration camps were evacuated. After transports to Auschwitz had ceased, 416 Slovak Jews were sent from Sereď to Theresienstadt on 23 December 1944; additional transports in 1945 brought the total to 1,447. The Slovak Jews told the Theresienstädters about the fate of those deported to the East, but many refused to believe it. 1,150 Hungarian Jews who had survived a death march to Vienna arrived in March. In 1945, 5,200 Jews living in mixed marriages with "Aryans", who had been previously protected, were deported to Theresienstadt.

On 5 February 1945, after negotiations with Swiss politician

Theresienstadt became the destination of transports as the Nazi concentration camps were evacuated. After transports to Auschwitz had ceased, 416 Slovak Jews were sent from Sereď to Theresienstadt on 23 December 1944; additional transports in 1945 brought the total to 1,447. The Slovak Jews told the Theresienstädters about the fate of those deported to the East, but many refused to believe it. 1,150 Hungarian Jews who had survived a death march to Vienna arrived in March. In 1945, 5,200 Jews living in mixed marriages with "Aryans", who had been previously protected, were deported to Theresienstadt.

On 5 February 1945, after negotiations with Swiss politician Jean-Marie Musy

Jean-Marie Musy (10 April 1876 – 19 April 1952) was a Swiss politician.

Affiliated with the Christian Democratic People's Party of Switzerland, he was elected to the Federal Council of Switzerland on 11 December 1919 served until 30 April 193 ...

, Himmler released a transport of 1,200 Jews (mostly from Germany and Holland) from Theresienstadt to neutral Switzerland; Jews on this transport traveled in Pullman passenger cars, were provided with various luxuries, and had to remove their Star of David badges. Jewish organisations deposited a ransom of 5 million Swiss francs in escrowed accounts. The Danish king Christian X secured the release of the Danish internees from Theresienstadt on 15 April 1945. The White Buses, organised in cooperation with the Swedish Red Cross, repatriated the 423 surviving Danish Jews.

Starting on 20 April, between 13,500 and 15,000 concentration camp prisoners, mostly Jews, arrived at Theresienstadt after surviving death marches from camps about to be liberated by the Allies. The prisoners were in very poor physical and mental shape, and, like the Białystok children, refused disinfection fearing that they would be gassed. They were starving and infected with lice and typhoid fever, an epidemic of which soon raged in the ghetto and claimed many lives. A Theresienstadt prisoner described them as "no longer people, they are wild animals".

The Red Cross took over administration of the ghetto and removed the SS flag on 2 May 1945; the SS fled on 5–6 May. On 8 May, Red Army troops skirmished with German forces outside the ghetto and liberated it at 9 pm. On 11 May, Soviet medical units arrived to take charge of the ghetto; the next day, Jiří Vogel, a Czech Jewish communist, was appointed elder and served until the ghetto was dissolved. Theresienstadt was the only Nazi ghetto liberated with a significant population of survivors. On 14 May, Soviet authorities imposed a strict quarantine to contain the typhoid epidemic; more than 1,500 prisoners and 43 doctors and nurses died around the time of liberation. After two weeks, the quarantine ended and the administration focused on returning survivors to their countries of origin; repatriation continued until 17 August 1945.

Starting on 20 April, between 13,500 and 15,000 concentration camp prisoners, mostly Jews, arrived at Theresienstadt after surviving death marches from camps about to be liberated by the Allies. The prisoners were in very poor physical and mental shape, and, like the Białystok children, refused disinfection fearing that they would be gassed. They were starving and infected with lice and typhoid fever, an epidemic of which soon raged in the ghetto and claimed many lives. A Theresienstadt prisoner described them as "no longer people, they are wild animals".

The Red Cross took over administration of the ghetto and removed the SS flag on 2 May 1945; the SS fled on 5–6 May. On 8 May, Red Army troops skirmished with German forces outside the ghetto and liberated it at 9 pm. On 11 May, Soviet medical units arrived to take charge of the ghetto; the next day, Jiří Vogel, a Czech Jewish communist, was appointed elder and served until the ghetto was dissolved. Theresienstadt was the only Nazi ghetto liberated with a significant population of survivors. On 14 May, Soviet authorities imposed a strict quarantine to contain the typhoid epidemic; more than 1,500 prisoners and 43 doctors and nurses died around the time of liberation. After two weeks, the quarantine ended and the administration focused on returning survivors to their countries of origin; repatriation continued until 17 August 1945.

Command and control authority

Theresienstadt was a hybrid of ghetto and concentration camp, with features of both. It was established by order of the RSHA in 1941 and, unlike other concentration camps, was not administered by the SS Main Economic and Administrative Office. Instead, the SS commandant reported to Hans Günther, the director of the Central Office for Jewish Emigration in Prague, whose superior was Adolf Eichmann. Theresienstadt also fell under the command of SS and Police Leader Karl Hermann Frank, the chief of police in the Protectorate, as it was classified as a SS-and-police-run camp. The SS commandant was in charge of some 28 SS men, 12 civilian employees, the Czech gendarmes who guarded the ghetto, and the Jewish self-administration. The first commandant wasSiegfried Seidl

Siegfried Seidl (24 August 1911 – 4 February 1947) was an Austrian career officer and World War II commandant of the Theresienstadt concentration camp located in the present-day Czech Republic. He also was commandant of the Bergen-Belsen, an ...

, who was replaced by Anton Burger

Anton "Toni" Burger (19 November 1911 – 25 December 1991) was a (Captain) in the German Nazi SS, in Greece (1944) and of Theresienstadt concentration camp.

Military career

Anton Burger was born in Neunkirchen, Austria, the son of a station ...

on 3 July 1943. Burger was reassigned and replaced by Karl Rahm

Karl Rahm (2 April 1907 – 30 April 1947) was a Sturmbannführer (major) in the German ''Schutzstaffel'' who, from February 1944 to May 1945, served as the commandant of the Theresienstadt concentration camp. Rahm was the third and final command ...

in January 1944; Rahm governed the ghetto until the SS fled on 5 May 1945. All of the SS commandants were assigned to Theresienstadt with the rank SS-'' Obersturmführer''.

The ghetto was guarded by 150–170 Czech gendarmes at one time. The guards, who often smuggled letters and food in return for bribes, were frequently rotated to avoid contacts developing between guards and prisoners. Fourteen of the guards were imprisoned at the Small Fortress for helping or contacting Jews; two died as a result of their imprisonment. The first gendarme commander, Theodor Janeček

Theodor is a masculine given name. It is a German form of Theodore. It is also a variant of Teodor.

List of people with the given name Theodor

* Theodor Adorno, (1903–1969), German philosopher

* Theodor Aman, Romanian painter

* Theodor Blueger, ...

, was a "rabid antisemite" whose behavior "sometimes surpass dthe SS in cruelty", according to Israeli historian Livia Rothkirchen

Livia Rothkirchen (1922 – March 2013) was a Czechoslovak-born Israeli historian and archivist. She was the author of several books about the Holocaust, including ''The Destruction of Slovak Jewry'' (1961), the first authoritative description of ...

. Janeček was replaced by Miroslaus Hasenkopf on 1 September 1943. The Ghetto Guard, a police force made up of Jewish prisoners, was formed on 6 December 1941 and reported to the Jewish self-administration. It was reconstituted several times and comprised 420 men at its peak in February 1943.

Jewish self-administration

The Jewish self-administration or self-government (german: jüdische Selbstverwaltung) nominally governed the ghetto. The self-administration included the Jewish elder (german: Judenältester), a deputy, and the Council of Elders (german: Ältestenrat) and a Central Secretariat beneath which various departments administered life in the ghetto. The first of the Jewish elders of Theresienstadt was Jakob Edelstein, a Zionist leader. Edelstein and his deputy,Otto Zucker

Otto is a masculine German given name and a surname. It originates as an Old High German short form (variants ''Audo'', '' Odo'', ''Udo'') of Germanic names beginning in ''aud-'', an element meaning "wealth, prosperity".

The name is recorded f ...

, initially planned to convert Theresienstadt into a productive economic center and thereby avoid deportations; they were unaware that the Nazis already planned to deport all the Jews and convert Theresienstadt into a German settlement. Theresienstadt was the only Jewish community in Nazi-occupied Europe that was led by Zionists.

The self-administration was characterized by excessive bureaucracy. In his landmark study ''Theresienstadt 1941–45'', H. G. Adler's list of all of the departments and sub-departments was 22 pages long. In 1943, when representatives of the Austrian and German Jewish community arrived at the ghetto, the administration was reorganized to include Austrian and German Jews. Paul Eppstein, from Berlin, was appointed as the liaison with the SS command, while Edelstein was obliged to act as his deputy. The SS used the national divisions to sow intrigue and disunity.

Corruption

The economy of Theresienstadt was highly corrupt. Besides the "prominent" prisoners, young Czech Jewish men had the highest status in the ghetto. As the first prisoners in the ghetto (whether in the ''Aufbaukommando'' or through connections to the ''Aufbaukommando'') most of the privileged positions in the ghetto fell to this group. Those in charge of distributing food typically skimmed off the deliveries to save more for themselves or their friends, which heightened the starvation for elderly Jews in particular. The SS also stole deliveries of food intended for prisoners. Many of the functionaries in the Transport Department enriched themselves by accepting bribes. Powerful individuals attempted, and often succeeded, to exempt their friends from deportation, a fact that was noted by prisoners at the time. Because Czech Zionists had a disproportionate influence in the self-administration, they were often able to secure better jobs and exemptions to transport for other Czech Zionists.

The economy of Theresienstadt was highly corrupt. Besides the "prominent" prisoners, young Czech Jewish men had the highest status in the ghetto. As the first prisoners in the ghetto (whether in the ''Aufbaukommando'' or through connections to the ''Aufbaukommando'') most of the privileged positions in the ghetto fell to this group. Those in charge of distributing food typically skimmed off the deliveries to save more for themselves or their friends, which heightened the starvation for elderly Jews in particular. The SS also stole deliveries of food intended for prisoners. Many of the functionaries in the Transport Department enriched themselves by accepting bribes. Powerful individuals attempted, and often succeeded, to exempt their friends from deportation, a fact that was noted by prisoners at the time. Because Czech Zionists had a disproportionate influence in the self-administration, they were often able to secure better jobs and exemptions to transport for other Czech Zionists.

Health care

Because of the unhygienic conditions in the ghetto and shortages of clean water, medicine, and food, many prisoners fell ill. 30% of the ghetto's population was classified as sick withscarlet fever

Scarlet fever, also known as Scarlatina, is an infectious disease caused by ''Streptococcus pyogenes'' a Group A streptococcus (GAS). The infection is a type of Group A streptococcal infection (Group A strep). It most commonly affects childr ...

, typhoid, diphtheria, polio, or encephalitis

Encephalitis is inflammation of the brain. The severity can be variable with symptoms including reduction or alteration in consciousness, headache, fever, confusion, a stiff neck, and vomiting. Complications may include seizures, hallucinations, ...