Theory Of Exhalations on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Early writing on mineralogy, especially on gemstones, comes from ancient

The ancient Greek writers

The ancient Greek writers  Ancient Greek terminology of minerals has also stuck through the ages with widespread usage in modern times. For example, the Greek word

Ancient Greek terminology of minerals has also stuck through the ages with widespread usage in modern times. For example, the Greek word

For example, Pliny devoted five entire volumes of his work

For example, Pliny devoted five entire volumes of his work

In the early 16th century AD, the writings of the

In the early 16th century AD, the writings of the

The medieval Chinese

The medieval Chinese

Mineralogy: A historical review

. ''Journal of Geological Education'', 32, 288–298. *Needham, Joseph (1986). ''Science and Civilization in China: Volume 3''. Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd. *Povarennykh A.S. (1972) "A Short History of Mineralogy and the Classification of Minerals". Crystal Chemical Classification of Minerals, 3–26. Springer, Boston, MA. *Ramsdell, Lewis S. (1963). ''Encyclopedia Americana: International Edition: Volume 19''. New York: Americana Corporation. *Sivin, Nathan (1995). ''Science in Ancient China''. Brookfield, Vermont: VARIORUM, Ashgate Publishing.

Virtual Museum of the History of MineralogyGeorg Agricola's "Textbook on Mineralogy" on gemstones and minerals

— ''translated from Latin by Mark Bandy; Original title: "De Natura Fossilium".'' {{Minerals +

Babylonia

Babylonia (; Akkadian: , ''māt Akkadī'') was an ancient Akkadian-speaking state and cultural area based in the city of Babylon in central-southern Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq and parts of Syria). It emerged as an Amorite-ruled state c. ...

, the ancient Greco-Roman

The Greco-Roman civilization (; also Greco-Roman culture; spelled Graeco-Roman in the Commonwealth), as understood by modern scholars and writers, includes the geographical regions and countries that culturally—and so historically—were di ...

world, ancient and medieval China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

, and Sanskrit

Sanskrit (; attributively , ; nominally , , ) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in South Asia after its predecessor languages had diffused there from the northwest in the late ...

texts from ancient India

According to consensus in modern genetics, anatomically modern humans first arrived on the Indian subcontinent from Africa between 73,000 and 55,000 years ago. Quote: "Y-Chromosome and Mt-DNA data support the colonization of South Asia by m ...

.Needham, Volume 3, 637. Books on the subject included the Naturalis Historia

The ''Natural History'' ( la, Naturalis historia) is a work by Pliny the Elder. The largest single work to have survived from the Roman Empire to the modern day, the ''Natural History'' compiles information gleaned from other ancient authors. ...

of Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/2479), called Pliny the Elder (), was a Roman author, naturalist and natural philosopher, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the emperor Vespasian. He wrote the encyclopedic '' ...

which not only described many different minerals but also explained many of their properties. The German Renaissance

The German Renaissance, part of the Northern Renaissance, was a cultural and artistic movement that spread among Germany, German thinkers in the 15th and 16th centuries, which developed from the Italian Renaissance. Many areas of the arts and ...

specialist Georgius Agricola

Georgius Agricola (; born Georg Pawer or Georg Bauer; 24 March 1494 – 21 November 1555) was a German Humanist scholar, mineralogist and metallurgist. Born in the small town of Glauchau, in the Electorate of Saxony of the Holy Roman Empir ...

wrote works such as '' De re metallica'' (''On Metals'', 1556) and ''De Natura Fossilium

''De Natura Fossilium'' is a scientific text written by Georg Bauer also known as Georgius Agricola, first published in 1546. The book represents the first scientific attempt to categorize minerals, rocks and sediments since the publication of Pl ...

'' (''On the Nature of Rocks'', 1546) which began the scientific approach to the subject. Systematic scientific studies of minerals and rocks developed in post-Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ideas ...

Europe.Needham, Volume 3, 636. The modern study of mineralogy was founded on the principles of crystallography

Crystallography is the experimental science of determining the arrangement of atoms in crystalline solids. Crystallography is a fundamental subject in the fields of materials science and solid-state physics (condensed matter physics). The wor ...

and microscopic

The microscopic scale () is the scale of objects and events smaller than those that can easily be seen by the naked eye, requiring a lens (optics), lens or microscope to see them clearly. In physics, the microscopic scale is sometimes regarded a ...

study of rock sections with the invention of the microscope

A microscope () is a laboratory instrument used to examine objects that are too small to be seen by the naked eye. Microscopy is the science of investigating small objects and structures using a microscope. Microscopic means being invisibl ...

in the 17th century.

Europe and the Middle East

The ancient Greek writers

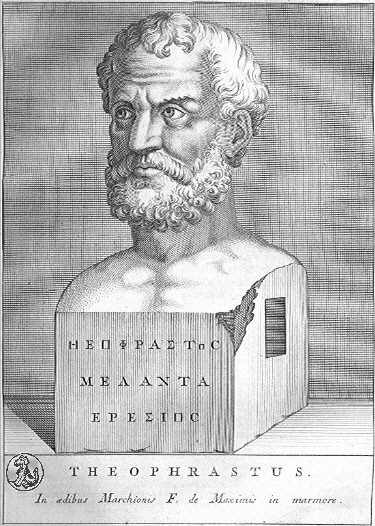

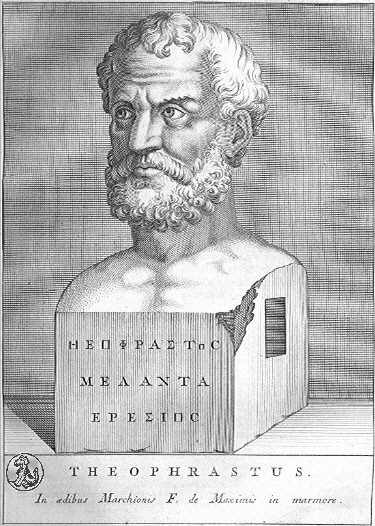

The ancient Greek writers Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of phil ...

(384–322 BC) and Theophrastus

Theophrastus (; grc-gre, Θεόφραστος ; c. 371c. 287 BC), a Greek philosopher and the successor to Aristotle in the Peripatetic school. He was a native of Eresos in Lesbos.Gavin Hardy and Laurence Totelin, ''Ancient Botany'', Routledge ...

(370–285 BC) were the first in the Western tradition to write of minerals and their properties, as well as metaphysical

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that studies the fundamental nature of reality, the first principles of being, identity and change, space and time, causality, necessity, and possibility. It includes questions about the nature of conscio ...

explanations for them. The Greek philosopher

Ancient Greek philosophy arose in the 6th century BC, marking the end of the Greek Dark Ages. Greek philosophy continued throughout the Hellenistic period and the period in which Greece and most Greek-inhabited lands were part of the Roman Empire ...

Aristotle wrote his ''Meteorologica

''Meteorology'' (Greek: ; Latin: ''Meteorologica'' or ''Meteora'') is a treatise by Aristotle. The text discusses what Aristotle believed to have been all the affections common to air and water, and the kinds and parts of the earth and the affect ...

'', and in it theorized that all the known substances were composed of water, air, earth, and fire, with the properties of dryness, dampness, heat, and cold.Bandy, i (Forward). The Greek philosopher and botanist

Botany, also called , plant biology or phytology, is the science of plant life and a branch of biology. A botanist, plant scientist or phytologist is a scientist who specialises in this field. The term "botany" comes from the Ancient Greek wo ...

Theophrastus wrote his ''De Mineralibus'', which accepted Aristotle's view, and divided minerals into two categories: those affected by heat and those affected by dampness.

The metaphysical emanation and exhalation (''anathumiaseis'') theory of Aristotle included early speculation on earth sciences including mineralogy. According to his theory, while metals were supposed to be congealed by means of moist exhalation, dry gaseous exhalation (''pneumatodestera'') was the efficient material cause of minerals found in the Earth's soil.Needham, Volume 3, 636-637. He postulated these ideas by using the examples of moisture on the surface of the earth (a moist vapor 'potentially like water'), while the other was from the earth itself, pertaining to the attributes of hot, dry, smoky, and highly combustible ('potentially like fire'). Aristotle's metaphysical theory from times of antiquity had wide-ranging influence on similar theory found in later medieval Europe, as the historian Berthelot notes:

Ancient Greek terminology of minerals has also stuck through the ages with widespread usage in modern times. For example, the Greek word

Ancient Greek terminology of minerals has also stuck through the ages with widespread usage in modern times. For example, the Greek word asbestos

Asbestos () is a naturally occurring fibrous silicate mineral. There are six types, all of which are composed of long and thin fibrous crystals, each fibre being composed of many microscopic "fibrils" that can be released into the atmosphere b ...

(meaning 'inextinguishable', or 'unquenchable'), for the unusual mineral known today containing fibrous

Fiber or fibre (from la, fibra, links=no) is a natural or artificial substance that is significantly longer than it is wide. Fibers are often used in the manufacture of other materials. The strongest engineering materials often incorporate ...

structure.Needham, Volume 3, 656. The ancient historians Strabo

Strabo''Strabo'' (meaning "squinty", as in strabismus) was a term employed by the Romans for anyone whose eyes were distorted or deformed. The father of Pompey was called "Pompeius Strabo". A native of Sicily so clear-sighted that he could see ...

(63 BC–19 AD) and Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/2479), called Pliny the Elder (), was a Roman author, naturalist and natural philosopher, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the emperor Vespasian. He wrote the encyclopedic '' ...

(23–79 AD) both wrote of asbestos, its qualities, and its origins, with the Hellenistic

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

belief that it was of a type of vegetable

Vegetables are parts of plants that are consumed by humans or other animals as food. The original meaning is still commonly used and is applied to plants collectively to refer to all edible plant matter, including the flowers, fruits, stems, ...

. Pliny the Elder listed it as a mineral common in India, while the historian Yu Huan

Yu Huan ( third century) was a historian of the state of Cao Wei during the Three Kingdoms period of China.

Life

Yu Huan was from Jingzhao Commandery, which is around present-day Xi'an, Shaanxi.''Shitong'' vol. 12. He is best known for writing ...

(239–265 AD) of China listed this 'fireproof cloth' as a product of ancient Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

or Arabia

The Arabian Peninsula, (; ar, شِبْهُ الْجَزِيرَةِ الْعَرَبِيَّة, , "Arabian Peninsula" or , , "Island of the Arabs") or Arabia, is a peninsula of Western Asia, situated northeast of Africa on the Arabian Plate. ...

(Chinese: Daqin

Daqin (; alternative transliterations include Tachin, Tai-Ch'in) is the ancient Chinese name for the Roman Empire or, depending on context, the Near East, especially Syria. It literally means "great Qin"; Qin () being the name of the founding dyna ...

). Although documentation of these minerals in ancient times does not fit the manner of modern scientific classification, there was nonetheless extensive written work on early mineralogy.

Pliny the Elder

For example, Pliny devoted five entire volumes of his work

For example, Pliny devoted five entire volumes of his work Naturalis Historia

The ''Natural History'' ( la, Naturalis historia) is a work by Pliny the Elder. The largest single work to have survived from the Roman Empire to the modern day, the ''Natural History'' compiles information gleaned from other ancient authors. ...

(77 AD) to the classification of "earths, metals, stones, and gems".Ramsdell, 164. He not only describes many minerals not known to Theophrastus

Theophrastus (; grc-gre, Θεόφραστος ; c. 371c. 287 BC), a Greek philosopher and the successor to Aristotle in the Peripatetic school. He was a native of Eresos in Lesbos.Gavin Hardy and Laurence Totelin, ''Ancient Botany'', Routledge ...

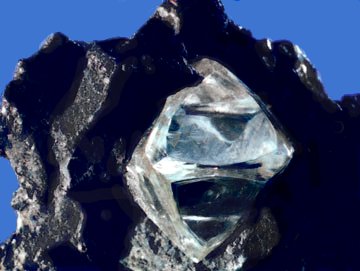

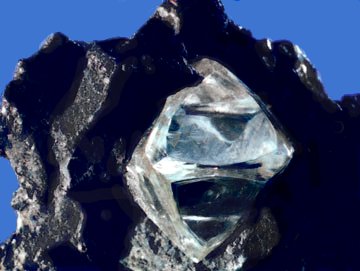

, but discusses their applications and properties. He is the first to correctly recognise the origin of amber

Amber is fossilized tree resin that has been appreciated for its color and natural beauty since Neolithic times. Much valued from antiquity to the present as a gemstone, amber is made into a variety of decorative objects."Amber" (2004). In Ma ...

for example, as the fossilised remnant of tree resin from the observation of insects trapped in some samples. He laid the basis of crystallography

Crystallography is the experimental science of determining the arrangement of atoms in crystalline solids. Crystallography is a fundamental subject in the fields of materials science and solid-state physics (condensed matter physics). The wor ...

by discussing crystal habit

In mineralogy, crystal habit is the characteristic external shape of an individual crystal or crystal group. The habit of a crystal is dependent on its crystallographic form and growth conditions, which generally creates irregularities due to l ...

, especially the octahedral

In geometry, an octahedron (plural: octahedra, octahedrons) is a polyhedron with eight faces. The term is most commonly used to refer to the regular octahedron, a Platonic solid composed of eight equilateral triangles, four of which meet at ea ...

shape of diamond

Diamond is a Allotropes of carbon, solid form of the element carbon with its atoms arranged in a crystal structure called diamond cubic. Another solid form of carbon known as graphite is the Chemical stability, chemically stable form of car ...

. His discussion of mining methods is unrivalled in the ancient world, and includes, for example, an eye-witness

In law, a witness is someone who has knowledge about a matter, whether they have sensed it or are testifying on another witnesses' behalf. In law a witness is someone who, either voluntarily or under compulsion, provides testimonial evidence, e ...

account of gold mining

Gold mining is the extraction of gold resources by mining. Historically, mining gold from alluvial deposits used manual separation processes, such as gold panning. However, with the expansion of gold mining to ores that are not on the surface ...

in northern Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

, an account which is fully confirmed by modern research.

However, before the more definitive foundational works on mineralogy in the 16th century, the ancients recognized no more than roughly 350 minerals to list and describe.Needham, Volume 3, 646.

Jabir and Avicenna

Islamic alchemists advanced thesulfur-mercury theory of metals

Abū Mūsā Jābir ibn Ḥayyān (Arabic: , variously called al-Ṣūfī, al-Azdī, al-Kūfī, or al-Ṭūsī), died 806−816, is the purported author of an enormous number and variety of works in Arabic, often called the Jabirian corpus. The ...

, a theory that is first found in pseudo-Apollonius of Tyana's ''Sirr al-khalīqa'' (''The Secret of Creation'', c. 750–850) and in the Arabic writings attributed to Jābir ibn Ḥayyān (written c. 850–950). It would remain the basis of all theories of metallic composition until the eighteenth century.

With philosophers such as Proclus

Proclus Lycius (; 8 February 412 – 17 April 485), called Proclus the Successor ( grc-gre, Πρόκλος ὁ Διάδοχος, ''Próklos ho Diádokhos''), was a Greek Neoplatonist philosopher, one of the last major classical philosophers ...

, the theory of Neoplatonism

Neoplatonism is a strand of Platonism, Platonic philosophy that emerged in the 3rd century AD against the background of Hellenistic philosophy and Hellenistic religion, religion. The term does not encapsulate a set of ideas as much as a chain of ...

also spread to the Islamic world

The terms Muslim world and Islamic world commonly refer to the Islamic community, which is also known as the Ummah. This consists of all those who adhere to the religious beliefs and laws of Islam or to societies in which Islam is practiced. In ...

during the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

, providing a basis for metaphysical ideas on mineralogy in the medieval Middle East as well. The medieval Islamic scientists expanded upon this as well, including the Persian

Persian may refer to:

* People and things from Iran, historically called ''Persia'' in the English language

** Persians, the majority ethnic group in Iran, not to be conflated with the Iranic peoples

** Persian language, an Iranian language of the ...

scientist Ibn Sina

Ibn Sina ( fa, ابن سینا; 980 – June 1037 CE), commonly known in the West as Avicenna (), was a Persian polymath who is regarded as one of the most significant physicians, astronomers, philosophers, and writers of the Islamic G ...

(ابوعلى سينا/پورسينا) (980-1037 AD), also known as ''Avicenna'', who rejected alchemy

Alchemy (from Arabic: ''al-kīmiyā''; from Ancient Greek: χυμεία, ''khumeía'') is an ancient branch of natural philosophy, a philosophical and protoscientific tradition that was historically practiced in China, India, the Muslim world, ...

and the earlier notion of Greek metaphysics that metallic and other elements could be transformed into one another. However, what was largely accurate of the ancient Greek and medieval metaphysical ideas on mineralogy was the slow chemical change in composition of the Earth's crust.

Georgius Agricola, 'Father of Mineralogy'

In the early 16th century AD, the writings of the

In the early 16th century AD, the writings of the German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ger ...

scientist Georg Bauer, pen-name Georgius Agricola

Georgius Agricola (; born Georg Pawer or Georg Bauer; 24 March 1494 – 21 November 1555) was a German Humanist scholar, mineralogist and metallurgist. Born in the small town of Glauchau, in the Electorate of Saxony of the Holy Roman Empir ...

(1494-1555 AD), in his ''Bermannus, sive de re metallica dialogus'' (1530) is considered to be the official establishment of mineralogy in the modern sense of its study. He wrote the treatise while working as a town physician and making observations in Joachimsthal, which was then a center for mining

Mining is the extraction of valuable minerals or other geological materials from the Earth, usually from an ore body, lode, vein, seam, reef, or placer deposit. The exploitation of these deposits for raw material is based on the economic via ...

and metallurgic smelting

Smelting is a process of applying heat to ore, to extract a base metal. It is a form of extractive metallurgy. It is used to extract many metals from their ores, including silver, iron, copper, and other base metals. Smelting uses heat and a ch ...

industries. In 1544, he published his written work ''De ortu et causis subterraneorum'', which is considered to be the foundational work of modern physical geology

Geology () is a branch of natural science concerned with Earth and other astronomical objects, the features or rocks of which it is composed, and the processes by which they change over time. Modern geology significantly overlaps all other Ear ...

. In it (much like Ibn Sina) he heavily criticized the theories laid out by the ancient Greeks such as Aristotle. His work on mineralogy and metallurgy continued with the publication of ''De veteribus et novis metallis'' in 1546, and culminated in his best known works, the '' De re metallica'' of 1556. It was an impressive work outlining applications of mining

Mining is the extraction of valuable minerals or other geological materials from the Earth, usually from an ore body, lode, vein, seam, reef, or placer deposit. The exploitation of these deposits for raw material is based on the economic via ...

, refining, and smelting

Smelting is a process of applying heat to ore, to extract a base metal. It is a form of extractive metallurgy. It is used to extract many metals from their ores, including silver, iron, copper, and other base metals. Smelting uses heat and a ch ...

metals, alongside discussions on geology of ore bodies, surveying

Surveying or land surveying is the technique, profession, art, and science of determining the terrestrial two-dimensional or three-dimensional positions of points and the distances and angles between them. A land surveying professional is ca ...

, mine construction, and ventilation

Ventilation may refer to:

* Ventilation (physiology), the movement of air between the environment and the lungs via inhalation and exhalation

** Mechanical ventilation, in medicine, using artificial methods to assist breathing

*** Ventilator, a ma ...

. He praises Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/2479), called Pliny the Elder (), was a Roman author, naturalist and natural philosopher, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the emperor Vespasian. He wrote the encyclopedic '' ...

for his pioneering work Naturalis Historia

The ''Natural History'' ( la, Naturalis historia) is a work by Pliny the Elder. The largest single work to have survived from the Roman Empire to the modern day, the ''Natural History'' compiles information gleaned from other ancient authors. ...

and makes extensive references to his discussion of minerals and mining methods. For the next two centuries this written work remained the authoritative text on mining in Europe.

Agricola had many various theories on mineralogy based on empirical observation, including understanding of the concept of ore

Ore is natural rock or sediment that contains one or more valuable minerals, typically containing metals, that can be mined, treated and sold at a profit.Encyclopædia Britannica. "Ore". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 7 April 2 ...

channels that were formed by the circulation of ground waters ('succi') in fissure

A fissure is a long, narrow crack opening along the surface of Earth. The term is derived from the Latin word , which means 'cleft' or 'crack'. Fissures emerge in Earth's crust, on ice sheets and glaciers, and on volcanoes.

Ground fissure

A ...

s subsequent to the deposition of the surrounding rocks. As will be noted below, the medieval Chinese previously had conceptions of this as well.

For his works, Agricola is posthumously known as the "Father of Mineralogy".

After the foundational work written by Agricola, it is widely agreed by the scientific community that the ''Gemmarum et Lapidum Historia'' of Anselmus de Boodt

Anselmus de Boodt or Anselmus Boëtius de Boodt (Bruges, 1550 - Bruges, 21 June 1632) was a Flemish humanist, mineralogist, physician and naturalist. Along with the German known as Georgius Agricola, de Boodt was responsible for establishing m ...

(1550–1632) of Bruges

Bruges ( , nl, Brugge ) is the capital and largest City status in Belgium, city of the Provinces of Belgium, province of West Flanders in the Flemish Region of Belgium, in the northwest of the country, and the sixth-largest city of the countr ...

is the first definitive work of modern mineralogy. The German mining chemist

A chemist (from Greek ''chēm(ía)'' alchemy; replacing ''chymist'' from Medieval Latin ''alchemist'') is a scientist trained in the study of chemistry. Chemists study the composition of matter and its properties. Chemists carefully describe th ...

J.F. Henckel wrote his ''Flora Saturnisans'' of 1760, which was the first treatise in Europe to deal with geobotanical minerals, although the Chinese had mentioned this in earlier treatises of 1421 and 1664.Needham, Volume 3, 678. In addition, the Chinese writer Du Wan made clear references to weathering and erosion processes in his ''Yun Lin Shi Pu'' of 1133, long before Agricola's work of 1546.

China and the Far East

In ancient China, the oldest literary listing of minerals dates back to at least the 4th century BC, with the ''Ji Ni Zi'' book listing twenty four of them.Needham, Volume 3, 643. Chinese ideas of metaphysical mineralogy span back to at least the ancient Han Dynasty (202 BC–220 AD). From the 2nd century BC text of the ''Huai Nan Zi'', the Chinese used ideologicalTaoist

Taoism (, ) or Daoism () refers to either a school of philosophical thought (道家; ''daojia'') or to a religion (道教; ''daojiao''), both of which share ideas and concepts of Chinese origin and emphasize living in harmony with the ''Tao'' ...

terms to describe meteorology

Meteorology is a branch of the atmospheric sciences (which include atmospheric chemistry and physics) with a major focus on weather forecasting. The study of meteorology dates back millennia, though significant progress in meteorology did not ...

, precipitation

In meteorology, precipitation is any product of the condensation of atmospheric water vapor that falls under gravitational pull from clouds. The main forms of precipitation include drizzle, rain, sleet, snow, ice pellets, graupel and hail. ...

, different types of minerals, metallurgy, and alchemy.Needham, Volume 3, 640. Although the understanding of these concepts in Han times was Taoist in nature, the theories proposed were similar to the Aristotelian theory of mineralogical exhalations (noted above). By 122 BC, the Chinese had thus formulated the theory for metamorphosis of minerals, although it is noted by historians such as Dubs that the tradition of alchemical-mineralogical Chinese doctrine stems back to the School of Naturalists headed by the philosopher Zou Yan

Zou Yan (; ; 305 BC240 BC) was a Chinese philosopher and spiritual writer best known as the representative thinker of the Yin and Yang School (or School of Naturalists) during the Hundred Schools of Thought era in Chinese philosophy.

Biography

Z ...

(305 BC–240 BC).Needham, Volume 3, 641. Within the broad categories of rocks and stones (shi) and metals and alloys (jin), by Han times the Chinese had hundreds (if not thousands) of listed types of stones and minerals, along with theories for how they were formed.

In the 5th century AD, Prince Qian Ping Wang of the Liu Song Dynasty

Song, known as Liu Song (), Former Song (前宋) or Song of (the) Southern Dynasty (南朝宋) in historiography, was an imperial dynasty of China and the first of the four Southern dynasties during the Northern and Southern dynasties period. ...

wrote in the encyclopedia ''Tai-ping Yu Lan'' (circa 444 AD, from the lost book ''Dian Shu'', or ''Management of all Techniques''):

''The most precious things in the world are stored in the innermost regions of all. For example, there isIn ancient and medieval China, mineralogy became firmly tied toorpiment Orpiment is a deep-colored, orange-yellow arsenic sulfide mineral with formula . It is found in volcanic fumaroles, low-temperature hydrothermal veins, and hot springs and is formed both by sublimation and as a byproduct of the decay of another a .... After a thousand years it changes intorealgar Realgar ( ), also known as "ruby sulphur" or "ruby of arsenic", is an arsenic sulfide mineral with the chemical formula α-. It is a soft, sectile mineral occurring in monoclinic crystals, or in granular, compact, or powdery form, often in assoc .... After another thousand years the realgar becomes transformed into yellow gold.''Needham, Volume 3, 638.

empirical

Empirical evidence for a proposition is evidence, i.e. what supports or counters this proposition, that is constituted by or accessible to sense experience or experimental procedure. Empirical evidence is of central importance to the sciences and ...

observations in pharmaceutics and medicine

Medicine is the science and practice of caring for a patient, managing the diagnosis, prognosis, prevention, treatment, palliation of their injury or disease, and promoting their health. Medicine encompasses a variety of health care pract ...

. For example, the famous horologist

Horology (; related to Latin '; ; , interfix ''-o-'', and suffix ''-logy''), . is the study of the measurement of time. Clocks, watches, clockwork, sundials, hourglasses, clepsydras, timers, time recorders, marine chronometers, and atomic clo ...

and mechanical

Mechanical may refer to:

Machine

* Machine (mechanical), a system of mechanisms that shape the actuator input to achieve a specific application of output forces and movement

* Mechanical calculator, a device used to perform the basic operations of ...

engineer

Engineers, as practitioners of engineering, are professionals who invent, design, analyze, build and test machines, complex systems, structures, gadgets and materials to fulfill functional objectives and requirements while considering the l ...

Su Song

Su Song (, 1020–1101), courtesy name Zirong (), was a Chinese polymathic scientist and statesman. Excelling in a variety of fields, he was accomplished in mathematics, Chinese astronomy, astronomy, History of cartography#China, cartography, ...

(1020–1101 AD) of the Song Dynasty

The Song dynasty (; ; 960–1279) was an imperial dynasty of China that began in 960 and lasted until 1279. The dynasty was founded by Emperor Taizu of Song following his usurpation of the throne of the Later Zhou. The Song conquered the rest ...

(960–1279 AD) wrote of mineralogy and pharmacology

Pharmacology is a branch of medicine, biology and pharmaceutical sciences concerned with drug or medication action, where a drug may be defined as any artificial, natural, or endogenous (from within the body) molecule which exerts a biochemica ...

in his ''Ben Cao Tu Jing'' of 1070. In it he created a systematic approach to listing various different minerals and their use in medicinal concoctions, such as all the variously known forms of mica

Micas ( ) are a group of silicate minerals whose outstanding physical characteristic is that individual mica crystals can easily be split into extremely thin elastic plates. This characteristic is described as perfect basal cleavage. Mica is ...

that could be used to cure various ills through digestion

Digestion is the breakdown of large insoluble food molecules into small water-soluble food molecules so that they can be absorbed into the watery blood plasma. In certain organisms, these smaller substances are absorbed through the small intest ...

.Needham, Volume 3, 648. Su Song also wrote of the subconchoidal fracture of native cinnabar

Cinnabar (), or cinnabarite (), from the grc, κιννάβαρι (), is the bright scarlet to brick-red form of Mercury sulfide, mercury(II) sulfide (HgS). It is the most common source ore for refining mercury (element), elemental mercury and ...

, signs of ore beds, and provided description on crystal form.Needham, Volume 3, 649. Similar to the ore channels formed by circulation of ground water mentioned above with the German scientist Agricola, Su Song made similar statements concerning copper carbonate Copper carbonate may refer to :

;Copper (II) compounds and minerals

* Copper(II) carbonate proper, (neutral copper carbonate): a rarely seen moisture-sensitive compound.

* Basic copper carbonate (the "copper carbonate" of commerce), actually a cop ...

, as did the earlier ''Ri Hua Ben Cao'' of 970 AD with copper sulfate

The sulfate or sulphate ion is a polyatomic anion with the empirical formula . Salts, acid derivatives, and peroxides of sulfate are widely used in industry. Sulfates occur widely in everyday life. Sulfates are salts of sulfuric acid and many ar ...

.

The Yuan Dynasty

The Yuan dynasty (), officially the Great Yuan (; xng, , , literally "Great Yuan State"), was a Mongol-led imperial dynasty of China and a successor state to the Mongol Empire after its division. It was established by Kublai, the fifth ...

scientist Zhang Si-xiao (died 1332 AD) provided a groundbreaking treatise on the conception of ore beds from the circulation of ground waters and rock fissures, two centuries before Georgius Agricola would come to similar conclusions.Needham, Volume 3, 650. In his ''Suo-Nan Wen Ji'', he applies this theory in describing the deposition of minerals by evaporation

Evaporation is a type of vaporization that occurs on the surface of a liquid as it changes into the gas phase. High concentration of the evaporating substance in the surrounding gas significantly slows down evaporation, such as when humidi ...

of (or precipitation from) ground waters in ore channels.Needham, Volume 3, 651.

In addition to alchemical theory posed above, later Chinese writers such as the Ming Dynasty

The Ming dynasty (), officially the Great Ming, was an Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China, ruling from 1368 to 1644 following the collapse of the Mongol Empire, Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming dynasty was the last ort ...

physician

A physician (American English), medical practitioner (Commonwealth English), medical doctor, or simply doctor, is a health professional who practices medicine, which is concerned with promoting, maintaining or restoring health through th ...

Li Shizhen

Li Shizhen (July 3, 1518 – 1593), courtesy name Dongbi, was a Chinese acupuncturist, herbalist, naturalist, pharmacologist, physician, and writer of the Ming dynasty. He is the author of a 27-year work, found in the ''Compendium of M ...

(1518–1593 AD) wrote of mineralogy in similar terms of Aristotle's metaphysical theory, as the latter wrote in his pharmaceutical

A medication (also called medicament, medicine, pharmaceutical drug, medicinal drug or simply drug) is a drug used to diagnose, cure, treat, or prevent disease. Drug therapy (pharmacotherapy) is an important part of the medical field and re ...

treatise ''Běncǎo Gāngmù'' (本草綱目, ''Compendium of Materia Medica

The ''Bencao gangmu'', known in English as the ''Compendium of Materia Medica'' or ''Great Pharmacopoeia'', is an encyclopedic gathering of medicine, natural history, and Chinese herbology compiled and edited by Li Shizhen and published in the ...

'', 1596). Another figure from the Ming era, the famous geographer

A geographer is a physical scientist, social scientist or humanist whose area of study is geography, the study of Earth's natural environment and human society, including how society and nature interacts. The Greek prefix "geo" means "earth" a ...

Xu Xiake

Xu Xiake (, January 5, 1587 – March 8, 1641), born Xu Hongzu (), courtesy name Zhenzhi (), was a Chinese travel writer and geographer of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), known best for his famous geographical treatise, and noted for his bravery ...

(1587–1641) wrote of mineral beds and mica schists in his treatise.Needham, Volume 3, 645. However, while European literature on mineralogy became wide and varied, the writers of the Ming and Qing

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing,, was a Manchu-led imperial dynasty of China and the last orthodox dynasty in Chinese history. It emerged from the Later Jin dynasty founded by the Jianzhou Jurchens, a Tungusic-speaki ...

dynasties wrote little of the subject (even compared to Chinese of the earlier Song era). The only other works from these two eras worth mentioning were the ''Shi Pin'' (Hierarchy of Stones) of Yu Jun in 1617, the ''Guai Shi Lu'' (Strange Rocks) of Song Luo in 1665, and the ''Guan Shi Lu'' (On Looking at Stones) in 1668. However, one figure from the Song era that is worth mentioning above all is Shen Kuo.

Theories of Shen Kuo

Song Dynasty

The Song dynasty (; ; 960–1279) was an imperial dynasty of China that began in 960 and lasted until 1279. The dynasty was founded by Emperor Taizu of Song following his usurpation of the throne of the Later Zhou. The Song conquered the rest ...

statesman and scientist Shen Kuo

Shen Kuo (; 1031–1095) or Shen Gua, courtesy name Cunzhong (存中) and pseudonym Mengqi (now usually given as Mengxi) Weng (夢溪翁),Yao (2003), 544. was a Chinese polymathic scientist and statesman of the Song dynasty (960–1279). Shen wa ...

(1031-1095 AD) wrote of his land formation theory involving concepts of mineralogy. In his ''Meng Xi Bi Tan'' (梦溪笔谈; ''Dream Pool Essays

''The Dream Pool Essays'' (or ''Dream Torrent Essays'') was an extensive book written by the Chinese polymath and statesman Shen Kuo (1031–1095), published in 1088 during the Song dynasty (960–1279) of China. Shen compiled this encycloped ...

'', 1088), Shen formulated a hypothesis for the process of land formation (geomorphology

Geomorphology (from Ancient Greek: , ', "earth"; , ', "form"; and , ', "study") is the scientific study of the origin and evolution of topographic and bathymetric features created by physical, chemical or biological processes operating at or n ...

); based on his observation of marine

Marine is an adjective meaning of or pertaining to the sea or ocean.

Marine or marines may refer to:

Ocean

* Maritime (disambiguation)

* Marine art

* Marine biology

* Marine debris

* Marine habitats

* Marine life

* Marine pollution

Military

* ...

fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

shells in a geological stratum in the Taihang Mountains

The Taihang Mountains () are a Chinese mountain range running down the eastern edge of the Loess Plateau in Shanxi, Henan and Hebei provinces. The range extends over from north to south and has an average elevation of . The principal peak is ...

hundreds of miles from the Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the continen ...

.Sivin, III, 23. He inferred that the land was formed by erosion of the mountains and by deposition of silt

Silt is granular material of a size between sand and clay and composed mostly of broken grains of quartz. Silt may occur as a soil (often mixed with sand or clay) or as sediment mixed in suspension with water. Silt usually has a floury feel when ...

, and described soil erosion

Soil erosion is the denudation or wearing away of the upper layer of soil. It is a form of soil degradation. This natural process is caused by the dynamic activity of erosive agents, that is, water, ice (glaciers), snow, air (wind), plants, and ...

, sedimentation

Sedimentation is the deposition of sediments. It takes place when particles in suspension settle out of the fluid in which they are entrained and come to rest against a barrier. This is due to their motion through the fluid in response to the ...

and uplift.Sivin, III, 23-24. In an earlier work of his (circa 1080), he wrote of a curious fossil of a sea-orientated creature found far inland.Needham, Volume 3, 618. It is also of interest to note that the contemporary author of the ''Xi Chi Cong Yu'' attributed the idea of particular places under the sea where serpents and crabs were petrified to one Wang Jinchen. With Shen Kuo's writing of the discovery of fossils, he formulated a hypothesis for the shifting of geographical climates throughout time.Needham, Volume 3, 614. This was due to hundreds of petrified

In geology, petrifaction or petrification () is the process by which organic material becomes a fossil through the replacement of the original material and the filling of the original pore spaces with minerals. Petrified wood typifies this proce ...

bamboo

Bamboos are a diverse group of evergreen perennial flowering plants making up the subfamily Bambusoideae of the grass family Poaceae. Giant bamboos are the largest members of the grass family. The origin of the word "bamboo" is uncertain, bu ...

s found underground in the dry climate of northern China, once an enormous landslide upon the bank of a river revealed them. Shen theorized that in pre-historic times, the climate of Yanzhou must have been very rainy and humid like southern China, where bamboos are suitable to grow.

In a similar way, the historian Joseph Needham

Noel Joseph Terence Montgomery Needham (; 9 December 1900 – 24 March 1995) was a British biochemist, historian of science and sinologist known for his scientific research and writing on the history of Chinese science and technology, in ...

likened Shen's account with the Scottish scientist Roderick Murchison

Sir Roderick Impey Murchison, 1st Baronet, (19 February 1792 – 22 October 1871) was a Scotland, Scottish geologist who served as director-general of the British Geological Survey from 1855 until his death in 1871. He is noted for investigat ...

(1792–1871), who was inspired to become a geologist after observing a providential landslide. In addition, Shen's description of sedimentary deposition predated that of James Hutton

James Hutton (; 3 June O.S.172614 June 1726 New Style. – 26 March 1797) was a Scottish geologist, agriculturalist, chemical manufacturer, naturalist and physician. Often referred to as the father of modern geology, he played a key role i ...

, who wrote his groundbreaking work in 1802 (considered the foundation of modern geology).Needham, Volume 3, 604 The influential philosopher Zhu Xi

Zhu Xi (; ; October 18, 1130 – April 23, 1200), formerly romanized Chu Hsi, was a Chinese calligrapher, historian, philosopher, poet, and politician during the Song dynasty. Zhu was influential in the development of Neo-Confucianism. He con ...

(1130–1200) wrote of this curious natural phenomena of fossils as well, and was known to have read the works of Shen Kuo.Chan, 15. In comparison, the first mentioning of fossils found in the West was made nearly two centuries later with Louis IX of France

Louis IX (25 April 1214 – 25 August 1270), commonly known as Saint Louis or Louis the Saint, was King of France from 1226 to 1270, and the most illustrious of the Direct Capetians. He was crowned in Reims at the age of 12, following the ...

in 1253 AD, who discovered fossils of marine animals (as recorded in Joinville's records of 1309 AD).Chan, 14.

America

Perhaps the most influential mineralogy text in the 19th and 20th centuries was the ''Manual of Mineralogy'' byJames Dwight Dana

James Dwight Dana Royal Society of London, FRS FRSE (February 12, 1813 – April 14, 1895) was an American geologist, mineralogist, volcanologist, and zoologist. He made pioneering studies of mountain-building, volcano, volcanic activity, and the ...

, Yale professor, first published in 1848. The fourth edition was entitled ''Manual of Mineralogy and Lithology'' (ed. 4, 1887). It became a standard college text, and has been continuously revised and updated by a succession of editors including W. E. Ford (13th-14th eds., 1912–1929), Cornelius S. Hurlbut (15th-21st eds., 1941–1999), and beginning with the 22nd by Cornelis Klein. The 23rd edition is now in print under the title ''Manual of Mineral Science (Manual of Mineralogy)'' (2007), revised by Cornelis Klein and Barbara Dutrow

Barbara Dutrow (born 1956) is an American geologist who is the Adolphe G. Gueymard Professor of Geology at Louisiana State University. Dutrow wrote the textbook ''Manual of Mineral Science''. She was elected President of the Geological Society of ...

.

Equally influential was Dana's ''System of Mineralogy'', first published in 1837, which has consistently been updated and revised. The 6th edition (1892) being edited by his son Edward Salisbury Dana

Edward Salisbury Dana (November 16, 1849 – June 16, 1935) was an American mineralogist and physicist. He made important contributions to the study of minerals, especially in the field of crystallography.

Life and career

E. S. Dana was born in N ...

. A 7th edition was published in 1944, and the 8th edition was published in 1997 under the title ''Dana's New Mineralogy: The System of Mineralogy of James Dwight Dana and Edward Salisbury Dana'', edited by R. V. Gaines ''et al.''

See also

*Timeline of the discovery and classification of minerals Georgius Agricola is considered the 'father of mineralogy'. Nicolas Steno founded the stratigraphy (the study of stratum, rock layers (strata) and layering (stratification)), the geology characterizes the rocks in each layer and the mineralogy chara ...

Notes

References

*Bandy, Mark Chance and Jean A. Bandy (1955). ''De Natura Fossilium''. New York: George Banta Publishing Company. *Chan, Alan Kam-leung and Gregory K. Clancey, Hui-Chieh Loy (2002).'' Historical Perspectives on East Asian Science, Technology and Medicine''. Singapore: Singapore University Press * Hazen, Robert M. (1984).Mineralogy: A historical review

. ''Journal of Geological Education'', 32, 288–298. *Needham, Joseph (1986). ''Science and Civilization in China: Volume 3''. Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd. *Povarennykh A.S. (1972) "A Short History of Mineralogy and the Classification of Minerals". Crystal Chemical Classification of Minerals, 3–26. Springer, Boston, MA. *Ramsdell, Lewis S. (1963). ''Encyclopedia Americana: International Edition: Volume 19''. New York: Americana Corporation. *Sivin, Nathan (1995). ''Science in Ancient China''. Brookfield, Vermont: VARIORUM, Ashgate Publishing.

External links

Virtual Museum of the History of Mineralogy

— ''translated from Latin by Mark Bandy; Original title: "De Natura Fossilium".'' {{Minerals +

Mineralogy

Mineralogy is a subject of geology specializing in the scientific study of the chemistry, crystal structure, and physical (including optical) properties of minerals and mineralized artifacts. Specific studies within mineralogy include the proces ...