Theories Of General Anaesthetic Action on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A general anaesthetic (or anesthetic) is a

A general anaesthetic (or anesthetic) is a

A nonspecific mechanism of general anaesthetic action was first proposed by Emil Harless and

A nonspecific mechanism of general anaesthetic action was first proposed by Emil Harless and

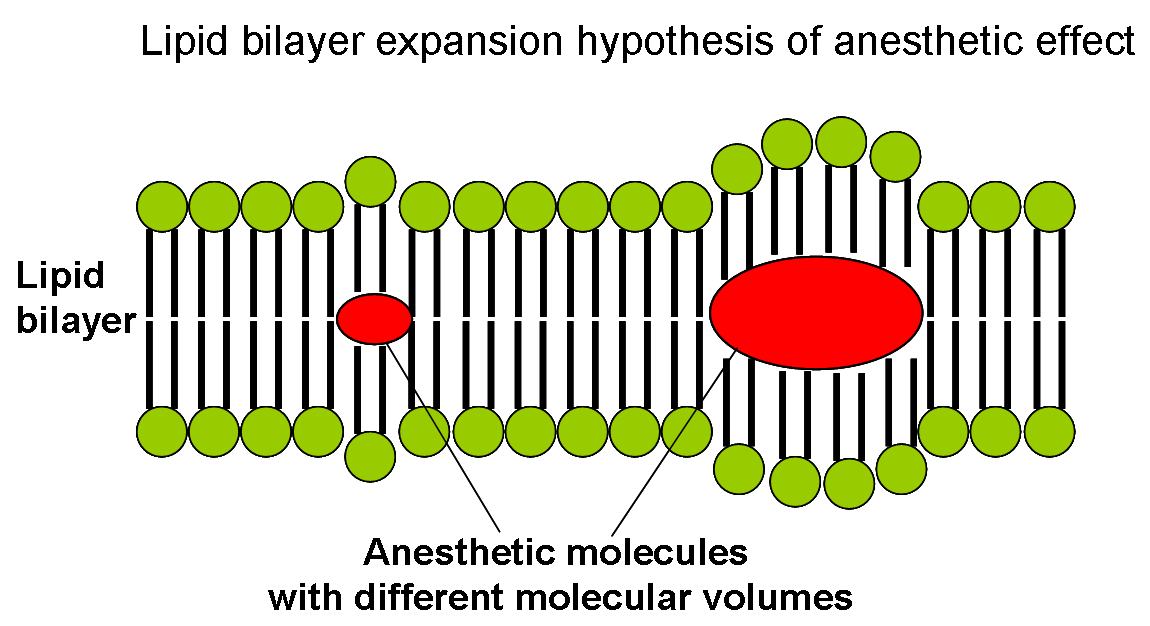

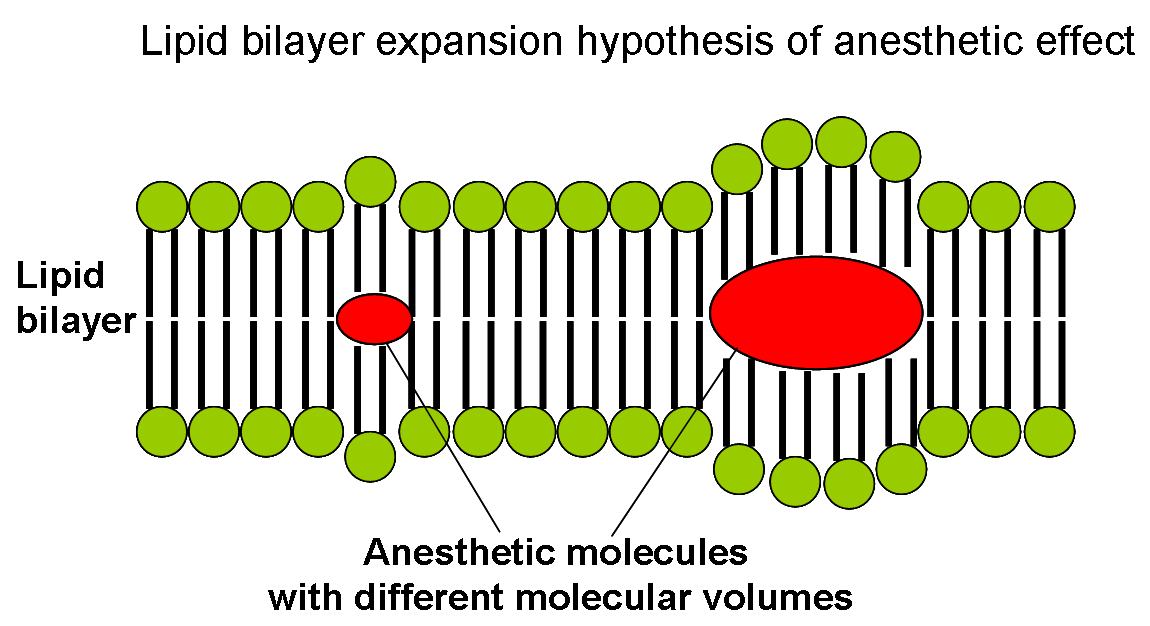

From the correlation between lipid solubility and anaesthetic potency, both Meyer and Overton had surmised a unitary mechanism of general anaesthesia. They assumed that solubilization of lipophilic general anaesthetic in lipid bilayer of the neuron causes its malfunction and anaesthetic effect when critical concentration of anaesthetic is reached. Later in 1973 Miller and Smith suggested the critical volume hypothesis also called lipid bilayer expansion hypothesis.

They assumed that bulky and hydrophobic anaesthetic molecules accumulate inside the hydrophobic (or lipophilic) regions of neuronal lipid membrane causing its distortion and expansion (thickening) due to volume displacement. Accumulation of critical amounts of anaesthetic causes membrane thickening sufficient to reversibly alter function of membrane ion channels thus providing anaesthetic effect. Actual chemical structure of the anaesthetic agent per se is not important, but its molecular volume plays the major role: the more space within membrane is occupied by anaesthetic - the greater is the anaesthetic effect.

Based on this theory, in 1954 Mullins suggested that the Meyer-Overton correlation with potency can be improved if molecular volumes of anaesthetic molecules are taken into account. This theory existed for over 60 years and was supported by experimental fact that increases in atmospheric pressure reverse anaesthetic effect (pressure reversal effect).

Then other,

From the correlation between lipid solubility and anaesthetic potency, both Meyer and Overton had surmised a unitary mechanism of general anaesthesia. They assumed that solubilization of lipophilic general anaesthetic in lipid bilayer of the neuron causes its malfunction and anaesthetic effect when critical concentration of anaesthetic is reached. Later in 1973 Miller and Smith suggested the critical volume hypothesis also called lipid bilayer expansion hypothesis.

They assumed that bulky and hydrophobic anaesthetic molecules accumulate inside the hydrophobic (or lipophilic) regions of neuronal lipid membrane causing its distortion and expansion (thickening) due to volume displacement. Accumulation of critical amounts of anaesthetic causes membrane thickening sufficient to reversibly alter function of membrane ion channels thus providing anaesthetic effect. Actual chemical structure of the anaesthetic agent per se is not important, but its molecular volume plays the major role: the more space within membrane is occupied by anaesthetic - the greater is the anaesthetic effect.

Based on this theory, in 1954 Mullins suggested that the Meyer-Overton correlation with potency can be improved if molecular volumes of anaesthetic molecules are taken into account. This theory existed for over 60 years and was supported by experimental fact that increases in atmospheric pressure reverse anaesthetic effect (pressure reversal effect).

Then other,

If general anaesthetics disrupt ion channels by partitioning into and perturbing the lipid bilayer, then one would expect that their solubility in lipid bilayers would also display the cutoff effect. However, partitioning of alcohols into lipid bilayers does not display a cutoff for long-chain alcohols from ''n''-

If general anaesthetics disrupt ion channels by partitioning into and perturbing the lipid bilayer, then one would expect that their solubility in lipid bilayers would also display the cutoff effect. However, partitioning of alcohols into lipid bilayers does not display a cutoff for long-chain alcohols from ''n''- However, cutoff effect can still be explained in the frame of lipid hypothesis. In short-chain alkanols (A) segments of the chain are rather rigid (in terms of conformational enthropy) and very close to hydroxyl group tethered to aqueous interfacial region ("buoy"). Consequently, these segments efficiently redistribute lateral stresses from the bilayer interior toward the interface. In long-chain alkanols (B) hydrocarbon chain segments are located further from hydroxyl group and are more flexible than in short-chain alkanols. Efficiency of pressure redistribution decreases as the length of hydrocarbon chain increases until anaesthetic potency is lost at some point. It was proposed that polyalkanols (C) will have anaesthetic effect similar to short-chain 1-alkanols if the chain length between two neighbouring hydroxyl groups is smaller than the cutoff. This idea was supported by the experimental evidence because polyhydroxyalkanes 1,6,11,16-hexadecanetetraol and 2,7,12,17-octadecanetetraol exhibited significant anaesthetic potency as was originally proposed.

Rebuttal to the objection: The argument assumes that all classes of anaesthetics must work the same on the membrane. It is quite possible that one or two classes of molecules could work through a non-membrane mediated mechanism. For example, the alcohols were shown to incorporate into the lipid membrane via an enzymatic transphosphatidylation reaction. The ethanol metabolite bound to and inhibited an anesthetic channel. And while this mechanism may contradict a single unitary mechanism of anaesthesia, it does not preclude a membrane mediated one.

However, cutoff effect can still be explained in the frame of lipid hypothesis. In short-chain alkanols (A) segments of the chain are rather rigid (in terms of conformational enthropy) and very close to hydroxyl group tethered to aqueous interfacial region ("buoy"). Consequently, these segments efficiently redistribute lateral stresses from the bilayer interior toward the interface. In long-chain alkanols (B) hydrocarbon chain segments are located further from hydroxyl group and are more flexible than in short-chain alkanols. Efficiency of pressure redistribution decreases as the length of hydrocarbon chain increases until anaesthetic potency is lost at some point. It was proposed that polyalkanols (C) will have anaesthetic effect similar to short-chain 1-alkanols if the chain length between two neighbouring hydroxyl groups is smaller than the cutoff. This idea was supported by the experimental evidence because polyhydroxyalkanes 1,6,11,16-hexadecanetetraol and 2,7,12,17-octadecanetetraol exhibited significant anaesthetic potency as was originally proposed.

Rebuttal to the objection: The argument assumes that all classes of anaesthetics must work the same on the membrane. It is quite possible that one or two classes of molecules could work through a non-membrane mediated mechanism. For example, the alcohols were shown to incorporate into the lipid membrane via an enzymatic transphosphatidylation reaction. The ethanol metabolite bound to and inhibited an anesthetic channel. And while this mechanism may contradict a single unitary mechanism of anaesthesia, it does not preclude a membrane mediated one.

There are two modern lipid hypothesis. The most recent hypothesis postulates that ordered lipids in the plasma membrane contain a structured binding site for the lipid

There are two modern lipid hypothesis. The most recent hypothesis postulates that ordered lipids in the plasma membrane contain a structured binding site for the lipid  Thus, according to the modern lipid hypothesis anaesthetics do not act directly on their membrane protein targets, but rather perturb specialized lipid matrices at the protein-lipid interface, which act as mediators. This is a new kind of transduction mechanism, different from the usual key-lock interaction of ligand and receptor, where the anaesthetic (ligand) affects the function of membrane proteins by binding to the specific site on the protein. Thus, some membrane proteins are proposed to be sensitive to their lipid environment.

A slightly different detailed molecular mechanism of how bilayer perturbation can influence the ion-channel was proposed in the same year. Oleamide (fatty acid amide of oleic acid) is an endogenous anaesthetic found in vivo (in the cat's brain) and it is known to potentiate sleep and lower the temperature of the body by closing the gap junction channel connexion. The detailed mechanism is shown on the picture: the well-ordered lipid(green)/cholesterol(yellow) ring that exists around connexon (magenta) becomes disordered on treatment with anaesthetic (red triangles), promoting a closure of connexon ion channel. This decreases brain activity and induces lethargy and anaesthetic effect.

Recently super resolution imaging showed direct experimental evidence that volatile anesthetic disrupt the ordered lipid domains as predicted. In the same study, a related mechanism emerged where the anesthetics released the enzyme

Thus, according to the modern lipid hypothesis anaesthetics do not act directly on their membrane protein targets, but rather perturb specialized lipid matrices at the protein-lipid interface, which act as mediators. This is a new kind of transduction mechanism, different from the usual key-lock interaction of ligand and receptor, where the anaesthetic (ligand) affects the function of membrane proteins by binding to the specific site on the protein. Thus, some membrane proteins are proposed to be sensitive to their lipid environment.

A slightly different detailed molecular mechanism of how bilayer perturbation can influence the ion-channel was proposed in the same year. Oleamide (fatty acid amide of oleic acid) is an endogenous anaesthetic found in vivo (in the cat's brain) and it is known to potentiate sleep and lower the temperature of the body by closing the gap junction channel connexion. The detailed mechanism is shown on the picture: the well-ordered lipid(green)/cholesterol(yellow) ring that exists around connexon (magenta) becomes disordered on treatment with anaesthetic (red triangles), promoting a closure of connexon ion channel. This decreases brain activity and induces lethargy and anaesthetic effect.

Recently super resolution imaging showed direct experimental evidence that volatile anesthetic disrupt the ordered lipid domains as predicted. In the same study, a related mechanism emerged where the anesthetics released the enzyme

In the early 1980s, Nicholas P. Franks and William R. Lieb demonstrated that the Meyer-Overton correlation can be reproduced using a soluble protein. They found that two classes of proteins are inactivated by clinical doses of anaesthetic in the total absence of lipids. These are

In the early 1980s, Nicholas P. Franks and William R. Lieb demonstrated that the Meyer-Overton correlation can be reproduced using a soluble protein. They found that two classes of proteins are inactivated by clinical doses of anaesthetic in the total absence of lipids. These are

The GABAA receptor (GABAAR) is an ionotropic receptor activated by the inhibitory neurotransmitter γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA).

Activation of the GABAA receptor leads to influx of

The GABAA receptor (GABAAR) is an ionotropic receptor activated by the inhibitory neurotransmitter γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA).

Activation of the GABAA receptor leads to influx of

A general anaesthetic (or anesthetic) is a

A general anaesthetic (or anesthetic) is a drug

A drug is any chemical substance that causes a change in an organism's physiology or psychology when consumed. Drugs are typically distinguished from food and substances that provide nutritional support. Consumption of drugs can be via insuffla ...

that brings about a reversible loss of consciousness

Consciousness, at its simplest, is sentience and awareness of internal and external existence. However, the lack of definitions has led to millennia of analyses, explanations and debates by philosophers, theologians, linguisticians, and scien ...

. These drugs are generally administered by an anaesthetist/anesthesiologist

Anesthesiology, anaesthesiology, or anaesthesia is the medical specialty concerned with the total perioperative care of patients before, during and after surgery. It encompasses anesthesia, intensive care medicine, critical emergency medicine, ...

in order to induce or maintain general anaesthesia

General anaesthesia (UK) or general anesthesia (US) is a medically induced loss of consciousness that renders the patient unarousable even with painful stimuli. This effect is achieved by administering either intravenous or inhalational general ...

to facilitate surgery

Surgery ''cheirourgikē'' (composed of χείρ, "hand", and ἔργον, "work"), via la, chirurgiae, meaning "hand work". is a medical specialty that uses operative manual and instrumental techniques on a person to investigate or treat a pat ...

.

General anaesthetics have been widely used in surgery since 1842 when Crawford Long

Crawford Williamson Long (November 1, 1815 – June 16, 1878) was an American surgeon and pharmacist best known for his first use of inhaled sulfuric ether as an anesthetic, discovered by performing surgeries on disabled African American slaves ...

for the first time administered diethyl ether

Diethyl ether, or simply ether, is an organic compound in the ether class with the formula , sometimes abbreviated as (see Pseudoelement symbols). It is a colourless, highly volatile, sweet-smelling ("ethereal odour"), extremely flammable liq ...

to a patient and performed a painless operation. It has long been believed that general anaesthetics exert their effects (analgesia, unconsciousness, immobility) through a membrane mediated mechanism or by directly modulating the activity of membrane proteins in the neuronal membrane.

In general, different anaesthetics exhibit different mechanisms of action such that there are numerous molecular targets at all levels of integration within the central nervous system

The central nervous system (CNS) is the part of the nervous system consisting primarily of the brain and spinal cord. The CNS is so named because the brain integrates the received information and coordinates and influences the activity of all par ...

.

However, for certain intravenous anaesthetics, such as propofol

Propofol, marketed as Diprivan, among other names, is a short-acting medication that results in a decreased level of consciousness and a lack of memory for events. Its uses include the starting and maintenance of general anesthesia, sedation f ...

and etomidate

Etomidate (USAN, INN, BAN; marketed as Amidate) is a short-acting intravenous anaesthetic agent used for the induction of general anaesthesia and sedation for short procedures such as reduction of dislocated joints, tracheal intubation, cardiove ...

, the main molecular target has been identified to be GABAA receptor, with particular β subunits playing a crucial role.

The concept of specific interactions between receptors and drugs first introduced by Paul Ehrlich

Paul Ehrlich (; 14 March 1854 – 20 August 1915) was a Nobel Prize-winning German physician and scientist who worked in the fields of hematology, immunology, and antimicrobial chemotherapy. Among his foremost achievements were finding a cure ...

in 1897 states that drugs act only when they are bound to their targets (receptors). The identification of concrete molecular targets for general anaesthetics, however, was made possible only with the modern development of molecular biology

Molecular biology is the branch of biology that seeks to understand the molecular basis of biological activity in and between cells, including biomolecular synthesis, modification, mechanisms, and interactions. The study of chemical and physi ...

techniques for single amino acid mutations in protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, respo ...

s of genetically engineered mice.

Lipid solubility-anaesthetic potency correlation (the Meyer-Overton correlation)

A nonspecific mechanism of general anaesthetic action was first proposed by Emil Harless and

A nonspecific mechanism of general anaesthetic action was first proposed by Emil Harless and Ernst von Bibra

Ernst von Bibra (9 June 1806 in Schwebheim – 5 June 1878 in Nuremberg) was a German Naturalist ( Natural history scientist) and author. Ernst was a botanist, zoologist, metallurgist, chemist, geographer, travel writer, novelist, duellis ...

in 1847.

They suggested that general anaesthetic

General anaesthetics (or anesthetics, see spelling differences) are often defined as compounds that induce a loss of consciousness in humans or loss of righting reflex in animals. Clinical definitions are also extended to include an induced coma ...

s may act by dissolving in the fatty fraction of brain cells and removing fatty constituents from them, thus changing activity of brain cells and inducing anaesthesia. In 1899 Hans Horst Meyer

Hans Horst Meyer (17 March 1853 – 6 October 1939) was a German pharmacologist. He studied medicine and did research in pharmacology. The Meyer-Overton hypothesis on the mode of action on general anaesthetics is partially named after him. H ...

published the first experimental evidence of the fact that anaesthetic potency is related to lipid solubility. Two years later a similar theory was published independently by Charles Ernest Overton

Charles Ernest Overton (1865–1933) was a British physiologist and biologist, now regarded as a pioneer of the theory of the cell membrane.

In the last years of the 19th century Overton did experimental work, allowing the distinction to be drawn ...

.

Meyer compared the potency of many agents, defined as the reciprocal of the molar concentration

In chemistry, concentration is the abundance of a constituent divided by the total volume of a mixture. Several types of mathematical description can be distinguished: '' mass concentration'', ''molar concentration'', ''number concentration'', an ...

required to induce anaesthesia in tadpoles, with their olive oil/water partition coefficient

In the physical sciences, a partition coefficient (''P'') or distribution coefficient (''D'') is the ratio of concentrations of a compound in a mixture of two immiscible solvents at equilibrium. This ratio is therefore a comparison of the solub ...

. He found a nearly linear relationship between potency and the partition coefficient for many types of anaesthetic molecules such as alcohol

Alcohol most commonly refers to:

* Alcohol (chemistry), an organic compound in which a hydroxyl group is bound to a carbon atom

* Alcohol (drug), an intoxicant found in alcoholic drinks

Alcohol may also refer to:

Chemicals

* Ethanol, one of sev ...

s, aldehyde

In organic chemistry, an aldehyde () is an organic compound containing a functional group with the structure . The functional group itself (without the "R" side chain) can be referred to as an aldehyde but can also be classified as a formyl grou ...

s, ketone

In organic chemistry, a ketone is a functional group with the structure R–C(=O)–R', where R and R' can be a variety of carbon-containing substituents. Ketones contain a carbonyl group –C(=O)– (which contains a carbon-oxygen double bo ...

s, ether

In organic chemistry, ethers are a class of compounds that contain an ether group—an oxygen atom connected to two alkyl or aryl groups. They have the general formula , where R and R′ represent the alkyl or aryl groups. Ethers can again be c ...

s, and ester

In chemistry, an ester is a compound derived from an oxoacid (organic or inorganic) in which at least one hydroxyl group () is replaced by an alkoxy group (), as in the substitution reaction of a carboxylic acid and an alcohol. Glycerides ar ...

s.

The anaesthetic concentration required to induce anaesthesia in 50% of a population of animals (the EC50) was independent of the means by which the anaesthetic was delivered, i.e., the gas or aqueous phase.

Meyer and Overton had discovered the striking correlation between the physical properties of general anaesthetic molecules and their potency: the greater the lipid solubility of a compound in olive oil, the greater its anaesthetic potency. This correlation is true for a wide range of anaesthetics with lipid solubilities ranging over 4-5 orders of magnitude if olive oil is used as the oil phase. However, this correlation can be improved considerably in terms of both the quality of the correlation and the increased range of anaesthetics if bulk octanol or a fully hydrated fluid lipid bilayer is used as the "oil" phase. It was also noted also that volatile anaesthetics are additive in their effects (a mixture of a half dose of two different volatile anaesthetics gave the same anaesthetic effect as a full dose of either drug alone).

Early lipid hypotheses of general anaesthetic action

From the correlation between lipid solubility and anaesthetic potency, both Meyer and Overton had surmised a unitary mechanism of general anaesthesia. They assumed that solubilization of lipophilic general anaesthetic in lipid bilayer of the neuron causes its malfunction and anaesthetic effect when critical concentration of anaesthetic is reached. Later in 1973 Miller and Smith suggested the critical volume hypothesis also called lipid bilayer expansion hypothesis.

They assumed that bulky and hydrophobic anaesthetic molecules accumulate inside the hydrophobic (or lipophilic) regions of neuronal lipid membrane causing its distortion and expansion (thickening) due to volume displacement. Accumulation of critical amounts of anaesthetic causes membrane thickening sufficient to reversibly alter function of membrane ion channels thus providing anaesthetic effect. Actual chemical structure of the anaesthetic agent per se is not important, but its molecular volume plays the major role: the more space within membrane is occupied by anaesthetic - the greater is the anaesthetic effect.

Based on this theory, in 1954 Mullins suggested that the Meyer-Overton correlation with potency can be improved if molecular volumes of anaesthetic molecules are taken into account. This theory existed for over 60 years and was supported by experimental fact that increases in atmospheric pressure reverse anaesthetic effect (pressure reversal effect).

Then other,

From the correlation between lipid solubility and anaesthetic potency, both Meyer and Overton had surmised a unitary mechanism of general anaesthesia. They assumed that solubilization of lipophilic general anaesthetic in lipid bilayer of the neuron causes its malfunction and anaesthetic effect when critical concentration of anaesthetic is reached. Later in 1973 Miller and Smith suggested the critical volume hypothesis also called lipid bilayer expansion hypothesis.

They assumed that bulky and hydrophobic anaesthetic molecules accumulate inside the hydrophobic (or lipophilic) regions of neuronal lipid membrane causing its distortion and expansion (thickening) due to volume displacement. Accumulation of critical amounts of anaesthetic causes membrane thickening sufficient to reversibly alter function of membrane ion channels thus providing anaesthetic effect. Actual chemical structure of the anaesthetic agent per se is not important, but its molecular volume plays the major role: the more space within membrane is occupied by anaesthetic - the greater is the anaesthetic effect.

Based on this theory, in 1954 Mullins suggested that the Meyer-Overton correlation with potency can be improved if molecular volumes of anaesthetic molecules are taken into account. This theory existed for over 60 years and was supported by experimental fact that increases in atmospheric pressure reverse anaesthetic effect (pressure reversal effect).

Then other, physicochemical

Physical chemistry is the study of macroscopic and microscopic phenomena in chemical systems in terms of the principles, practices, and concepts of physics such as motion, energy, force, time, thermodynamics, quantum chemistry, statistical mecha ...

theories of anaesthetic action emerged that took into account the diverse chemical nature of general anaesthetics and suggested that anaesthetic effect is exerted through some perturbation of the lipid bilayer. Several types of bilayer perturbations were proposed to cause anaesthetic effect, including (1) changes in phase separation, (2) changes in bilayer thickness, (3) changes in order parameters, or (4) changes in curvature elasticity.

According to the lateral phase separation theory anaesthetics exert their action by fluidizing nerve membranes to a point when phase separations in the critical lipid regions disappear. This anaesthetic-induced fluidization makes membranes less able to facilitate the conformational changes in proteins that may be the basis for such membrane events as ion gating, synaptic transmitter release, and transmitter binding to receptors. More recent techniques with super resolution imaging show that the anesthetics do not overcome phase separation—the phase separation persists. Rather saturated lipids within the phase separation can undergo a transitions from ordered to disordered which is dramatically affected by anesthetics. Nonetheless the concept of proteins moving between phase separated lipids in response to anesthetic has now been shown to be correct.

All these early lipid theories were generally thought to suffer from four weaknesses (full description with rebuttals see in sections below):

* Stereoisomers of an anaesthetic drug have very different anaesthetic potency whereas their oil/gas partition coefficients are similar

* Certain drugs that are highly soluble in lipids, and therefore expected to act as anaesthetics, exert convulsive effect instead (and therefore were called nonimmobilizers).

* A small increase in body temperature affects membrane density and fluidity as much as general anaesthetics, yet it does not cause anaesthesia.

* Increasing the chain length in a homologous series of straight-chain alcohols or alkanes increases their lipid solubility, but their anaesthetic potency stops increasing beyond a certain cutoff length.

Therefore, the correlation between lipid solubility and potency of general anaesthetics was thought to be a necessary but insufficient condition for inferring a lipid target site. General anaesthetics could equally well be binding to hydrophobic

In chemistry, hydrophobicity is the physical property of a molecule that is seemingly repelled from a mass of water (known as a hydrophobe). In contrast, hydrophiles are attracted to water.

Hydrophobic molecules tend to be nonpolar and, th ...

target sites on proteins in the brain, but given the chemical diversity of anesthetics this would likely need to include more than one site and those sites would not inherently preclude a site in the membrane. For protein's, one reason that more polar

Polar may refer to:

Geography

Polar may refer to:

* Geographical pole, either of two fixed points on the surface of a rotating body or planet, at 90 degrees from the equator, based on the axis around which a body rotates

* Polar climate, the c ...

general anaesthetics could be less potent is that they have to cross the blood–brain barrier

The blood–brain barrier (BBB) is a highly selective semipermeable membrane, semipermeable border of endothelium, endothelial cells that prevents solutes in the circulating blood from ''non-selectively'' crossing into the extracellular fluid of ...

to exert their effect on neurons in the brain.

Objections to the early lipid hypotheses

1. Stereoisomers of an anaesthetic drug

Stereoisomers that represent mirror images of each other are termedenantiomers

In chemistry, an enantiomer ( /ɪˈnænti.əmər, ɛ-, -oʊ-/ ''ih-NAN-tee-ə-mər''; from Ancient Greek ἐνάντιος ''(enántios)'' 'opposite', and μέρος ''(méros)'' 'part') – also called optical isomer, antipode, or optical anti ...

or optical isomers

In chemistry, a molecule or ion is called chiral () if it cannot be superposed on its mirror image by any combination of rotations, translations, and some conformational changes. This geometric property is called chirality (). The terms are d ...

(for example, the isomers of R-(+)- and S-(−)-etomidate).

Physicochemical effects of enantiomers are always identical in an achiral environment (for example in the lipid bilayer). However, in vivo enantiomers of many general anaesthetics (e.g. isoflurane

Isoflurane, sold under the brand name Forane among others, is a general anesthetic. It can be used to start or maintain anesthesia; however, other medications are often used to start anesthesia rather than isoflurane, due to airway irritation w ...

, thiopental

Sodium thiopental, also known as Sodium Pentothal (a trademark of Abbott Laboratories), thiopental, thiopentone, or Trapanal (also a trademark), is a rapid-onset short-acting barbiturate general anesthetic. It is the thiobarbiturate analog of pe ...

, etomidate

Etomidate (USAN, INN, BAN; marketed as Amidate) is a short-acting intravenous anaesthetic agent used for the induction of general anaesthesia and sedation for short procedures such as reduction of dislocated joints, tracheal intubation, cardiove ...

) can differ greatly in their anaesthetic potency despite the similar oil/gas partition coefficients. For example, the R-(+) isomer of etomidate is 10 times more potent anaesthetic than its S-(-) isomer. This means that optical isomers partition identically into lipid, but have differential effects on ion channels

Ion channels are pore-forming membrane proteins that allow ions to pass through the channel pore. Their functions include establishing a resting membrane potential, shaping action potentials and other electrical signals by gating the flow of io ...

and synaptic transmission

Neurotransmission (Latin: ''transmissio'' "passage, crossing" from ''transmittere'' "send, let through") is the process by which signaling molecules called neurotransmitters are released by the axon terminal of a neuron (the presynaptic neuron), ...

. This objection provides a compelling evidence that the primary target for anaesthetics is not the achiral lipid bilayer itself but rather stereoselective binding sites on membrane proteins that provide a chiral

Chirality is a property of asymmetry important in several branches of science. The word ''chirality'' is derived from the Greek (''kheir''), "hand", a familiar chiral object.

An object or a system is ''chiral'' if it is distinguishable from ...

environment for specific anaesthetic-protein docking interactions.

Rebuttal to the objection: 1) Stereo selective transport of the anesthetic was never considered. Anesthetics are hydrophobic and transported bound to proteins in the blood. Any stereo selective binding to the transport protein would change the concentration at the site of action. Furthermore a protein sink in the membrane could bind one of the isomers slightly better and reduce the effective concentration the membrane experiences. All stereo isomers are effective anesthetics, they only shifted the sensitivity, suggesting selective transport and selective protein sinks need to be considered. 2) Lipids are chiral, the same as proteins. And like proteins, lipids have ordered and disordered regions. The field failed to investigate the chirality of ordered lipids due to a lack of knowledge of their existence.

2. Nonimmobilizers

All general anaesthetics induce immobilization (absence of movement in response to noxious stimuli) through depression of spinal cord functions, whereas their amnesic actions are exerted within the brain. According to the Meyer-Overton correlation the anaesthetic potency of the drug is directly proportional to its lipid solubility, however, there are many compounds that do not satisfy this rule. These drugs are strikingly similar to potent general anaesthetics and are predicted to be potent anaesthetics based on their lipid solubility, but they exert only one constituent of the anaesthetic action (amnesia) and do not suppress movement (i.e. do not depress spinal cord functions) as all anaesthetics do. These drugs are referred to as nonimmobilizers. The existence of nonimmobilizers suggests that anaesthetics induce different components of anaesthetic effect (amnesia and immobility) by affecting different molecular targets and not just the one target (neuronal bilayer) as it was believed earlier. Good example of non-immobilizers are halogenated alkanes that are very hydrophobic, but fail to suppress movement in response to noxious stimulation at appropriate concentrations. See also:flurothyl

Flurothyl (Indoklon) (IUPAC names: 1,1,1-trifluoro-2-(2,2,2-trifluoroethoxy)ethane or bis(2,2,2-trifluoroethyl) ether) is a volatile liquid drug from the halogenated ether family, related to inhaled anaesthetic agents such as diethyl ether, b ...

.

Rebuttal to the objection: This is a logical fallacy. The existence of less than 10-20 related compounds that are known to disobey the Meyer-Overton hypothesis in no way negates the hundreds if not thousands of chemically diverse compounds that do obey the Meyer-Overton hypothesis. The hypothesis does not require that every molecule ever tested obeys the hypothesis for the hypothesis to be true. Exceptions can exists for reasons unrelated to the mechanism underlying the Meyer-Overton hypothesis.

3. Temperature increases do not have anaesthetic effect

Experimental studies have shown that general anaesthetics including ethanol are potent fluidizers of natural and artificial membranes. However, changes in membrane density and fluidity in the presence of clinical concentrations of general anaesthetics are so small that relatively small increases in temperature (~1 °C) can mimic them without causing anaesthesia. The change in body temperature of approximately 1 °C is within the physiological range and clearly it is not sufficient to induce loss of consciousness per se. Thus membranes are fluidized only by large quantities of anaesthetics, but there are no changes in membrane fluidity when concentrations of anaesthetics are small and restricted to pharmacologically relevant. Rebuttal to the objection: Early studies only considered the fluidity of the bulk lipid membrane. Recent work has shown that small temperature changes can cause large changes in fluidity in ordered nanoscopic lipid domains in both animals and cells.4. Effect vanishes beyond a certain chain length

According to the Meyer-Overton correlation, in ahomologous series

In organic chemistry, a homologous series is a sequence of compounds with the same functional group and similar chemical properties in which the members of the series can be branched or unbranched, or differ by molecular formula of and molecu ...

of any general anaesthetic (e.g. ''n''-alcohol

Alcohol most commonly refers to:

* Alcohol (chemistry), an organic compound in which a hydroxyl group is bound to a carbon atom

* Alcohol (drug), an intoxicant found in alcoholic drinks

Alcohol may also refer to:

Chemicals

* Ethanol, one of sev ...

s, or alkanes), increasing the chain length increases the lipid solubility, and thereby should produce a corresponding increase in anaesthetic potency. However, beyond a certain chain length the anaesthetic effect disappears. For the ''n''-alcohols, this cutoff occurs at a carbon chain length of about 13 and for the ''n''-alkanes at a chain length of between 6 and 10, depending on the species.

If general anaesthetics disrupt ion channels by partitioning into and perturbing the lipid bilayer, then one would expect that their solubility in lipid bilayers would also display the cutoff effect. However, partitioning of alcohols into lipid bilayers does not display a cutoff for long-chain alcohols from ''n''-

If general anaesthetics disrupt ion channels by partitioning into and perturbing the lipid bilayer, then one would expect that their solubility in lipid bilayers would also display the cutoff effect. However, partitioning of alcohols into lipid bilayers does not display a cutoff for long-chain alcohols from ''n''-decanol

1-Decanol is a straight chain fatty alcohol with ten carbon atoms and the molecular formula C10H21OH. It is a colorless to light yellow viscous liquid that is insoluble in water and has an aromatic odor. The interfacial tension against water at ...

to ''n''- pentadecanol. A plot of chain length vs. the logarithm of the lipid bilayer/buffer partition coefficient ''K'' is linear, with the addition of each methylene group causing a change in the Gibbs free energy

In thermodynamics, the Gibbs free energy (or Gibbs energy; symbol G) is a thermodynamic potential that can be used to calculate the maximum amount of work that may be performed by a thermodynamically closed system at constant temperature and pr ...

of -3.63 kJ/mol.

The cutoff effect was first interpreted as evidence that anaesthetics exert their effect not by acting globally on membrane lipids but rather by binding directly to hydrophobic pockets of well-defined volumes in proteins. As the alkyl chain

In organic chemistry, an alkyl group is an alkane missing one hydrogen.

The term ''alkyl'' is intentionally unspecific to include many possible substitutions.

An acyclic alkyl has the general formula of . A cycloalkyl is derived from a cycloalk ...

grows, the anaesthetic fills more of the hydrophobic pocket and binds with greater affinity. When the molecule is too large to be entirely accommodated by the hydrophobic pocket, the binding affinity no longer increases with increasing chain length. Thus the volume of the n-alkanol chain at the cutoff length provides an estimate of the binding site volume. This objection provided the basis for protein hypothesis of anaesthetic effect (see below).

However, cutoff effect can still be explained in the frame of lipid hypothesis. In short-chain alkanols (A) segments of the chain are rather rigid (in terms of conformational enthropy) and very close to hydroxyl group tethered to aqueous interfacial region ("buoy"). Consequently, these segments efficiently redistribute lateral stresses from the bilayer interior toward the interface. In long-chain alkanols (B) hydrocarbon chain segments are located further from hydroxyl group and are more flexible than in short-chain alkanols. Efficiency of pressure redistribution decreases as the length of hydrocarbon chain increases until anaesthetic potency is lost at some point. It was proposed that polyalkanols (C) will have anaesthetic effect similar to short-chain 1-alkanols if the chain length between two neighbouring hydroxyl groups is smaller than the cutoff. This idea was supported by the experimental evidence because polyhydroxyalkanes 1,6,11,16-hexadecanetetraol and 2,7,12,17-octadecanetetraol exhibited significant anaesthetic potency as was originally proposed.

Rebuttal to the objection: The argument assumes that all classes of anaesthetics must work the same on the membrane. It is quite possible that one or two classes of molecules could work through a non-membrane mediated mechanism. For example, the alcohols were shown to incorporate into the lipid membrane via an enzymatic transphosphatidylation reaction. The ethanol metabolite bound to and inhibited an anesthetic channel. And while this mechanism may contradict a single unitary mechanism of anaesthesia, it does not preclude a membrane mediated one.

However, cutoff effect can still be explained in the frame of lipid hypothesis. In short-chain alkanols (A) segments of the chain are rather rigid (in terms of conformational enthropy) and very close to hydroxyl group tethered to aqueous interfacial region ("buoy"). Consequently, these segments efficiently redistribute lateral stresses from the bilayer interior toward the interface. In long-chain alkanols (B) hydrocarbon chain segments are located further from hydroxyl group and are more flexible than in short-chain alkanols. Efficiency of pressure redistribution decreases as the length of hydrocarbon chain increases until anaesthetic potency is lost at some point. It was proposed that polyalkanols (C) will have anaesthetic effect similar to short-chain 1-alkanols if the chain length between two neighbouring hydroxyl groups is smaller than the cutoff. This idea was supported by the experimental evidence because polyhydroxyalkanes 1,6,11,16-hexadecanetetraol and 2,7,12,17-octadecanetetraol exhibited significant anaesthetic potency as was originally proposed.

Rebuttal to the objection: The argument assumes that all classes of anaesthetics must work the same on the membrane. It is quite possible that one or two classes of molecules could work through a non-membrane mediated mechanism. For example, the alcohols were shown to incorporate into the lipid membrane via an enzymatic transphosphatidylation reaction. The ethanol metabolite bound to and inhibited an anesthetic channel. And while this mechanism may contradict a single unitary mechanism of anaesthesia, it does not preclude a membrane mediated one.

Modern lipid hypothesis

There are two modern lipid hypothesis. The most recent hypothesis postulates that ordered lipids in the plasma membrane contain a structured binding site for the lipid

There are two modern lipid hypothesis. The most recent hypothesis postulates that ordered lipids in the plasma membrane contain a structured binding site for the lipid palmitate

Palmitic acid (hexadecanoic acid in IUPAC nomenclature) is a fatty acid with a 16-carbon chain. It is the most common saturated fatty acid found in animals, plants and microorganisms.Gunstone, F. D., John L. Harwood, and Albert J. Dijkstra. The Li ...

. It is a lipid binding site within a lipid structure, not a protein structure. Proteins that contain a covalently attache palmitate (palmitoylation

Palmitoylation is the covalent attachment of fatty acids, such as palmitic acid, to cysteine (''S''-palmitoylation) and less frequently to serine and threonine (''O''-palmitoylation) residues of proteins, which are typically lipid bilayer, memb ...

) are targeted to the ordered lipids through the lipid-lipid interaction. The binding of palmitate to the lipid domain is cholesterol dependent and the cell regulates the protein by nanoscopic localization. The anesthetics work by inserting into the membrane between the cholesterol and the palmitate, which disrupts the ability of the cholesterol to bind to and sequester the protein into an inactive state. This membrane mediated mechanism was demonstrated experimentally by Pavel and colleagues in 2020. They showed the enzyme phospholipase

A phospholipase is an enzyme that hydrolyzes phospholipids into fatty acids and other lipophilic substances. Acids trigger the release of bound calcium from cellular stores and the consequent increase in free cytosolic Ca2+, an essential step in ...

D2 (PLD2) is anesthetic sensitive and activates the potassium channel TREK-1

Potassium channel subfamily K member 2, also known as TREK-1, is a protein that in humans is encoded by the ''KCNK2'' gene.

This gene encodes K2P2.1, a lipid-gated ion channel belonging to the two-pore-domain background potassium channel protein ...

through a membrane mediated mechanism. The anesthetics displaced PLD2 from ordered lipid domains allowing the enzyme to be activated by substrate presentation Substrate presentation is a biological process that activates a protein. The protein is sequestered away from its substrate and then activated by release and exposure of the protein to its substrate. A substrate is typically the substance on which ...

and activate the channel.

The second lipid hypothesis states that anaesthetic effect happens if solubilization of general anaesthetic in the bilayer causes a redistribution of membrane lateral pressures.

Each bilayer membrane has a distinct profile of how lateral pressures are distributed within it. Most membrane proteins (especially ion channels) are sensitive to changes in this lateral pressure distribution profile. These lateral stresses are rather large and vary with depth within the membrane. According to the modern lipid hypothesis a change in the membrane lateral pressure profile shifts the conformational equilibrium of certain membrane proteins known to be affected by clinical concentrations of anaesthetics such as ligand-gated ion channels. This mechanism is also nonspecific because the potency of the anaesthetic is determined not by its actual chemical structure, but by the positional and orientational distribution of its segments and bonds within the bilayer.

In 1997, Cantor suggested a detailed mechanism of general anesthesia based on lattice statistical thermodynamics. It was proposed that incorporation of amphiphilic and other interfacially active solutes (e.g. general anaesthetics) into the bilayer increases the lateral pressure selectively near the aqueous interfaces, which is compensated by a decrease in lateral pressure toward the centre of the bilayer. Calculations showed that general anaesthesia likely involves inhibition of the opening of the ion channel in a postsynaptic ligand-gated membrane protein by the following mechanism:

* A channel tries to open in response to a nerve impulse thus increasing the cross-sectional area of the protein more near the aqueous interface than in the middle of the bilayer;

* Then the anaesthetic-induced increase in lateral pressure near the interface shifts the protein conformational equilibrium back to the closed state, since channel opening will require greater work against the higher pressure at interface. This is the first hypothesis that provided not just correlations of potency with structural or thermodynamic properties, but a detailed mechanistic and thermodynamic understanding of anaesthesia.

Thus, according to the modern lipid hypothesis anaesthetics do not act directly on their membrane protein targets, but rather perturb specialized lipid matrices at the protein-lipid interface, which act as mediators. This is a new kind of transduction mechanism, different from the usual key-lock interaction of ligand and receptor, where the anaesthetic (ligand) affects the function of membrane proteins by binding to the specific site on the protein. Thus, some membrane proteins are proposed to be sensitive to their lipid environment.

A slightly different detailed molecular mechanism of how bilayer perturbation can influence the ion-channel was proposed in the same year. Oleamide (fatty acid amide of oleic acid) is an endogenous anaesthetic found in vivo (in the cat's brain) and it is known to potentiate sleep and lower the temperature of the body by closing the gap junction channel connexion. The detailed mechanism is shown on the picture: the well-ordered lipid(green)/cholesterol(yellow) ring that exists around connexon (magenta) becomes disordered on treatment with anaesthetic (red triangles), promoting a closure of connexon ion channel. This decreases brain activity and induces lethargy and anaesthetic effect.

Recently super resolution imaging showed direct experimental evidence that volatile anesthetic disrupt the ordered lipid domains as predicted. In the same study, a related mechanism emerged where the anesthetics released the enzyme

Thus, according to the modern lipid hypothesis anaesthetics do not act directly on their membrane protein targets, but rather perturb specialized lipid matrices at the protein-lipid interface, which act as mediators. This is a new kind of transduction mechanism, different from the usual key-lock interaction of ligand and receptor, where the anaesthetic (ligand) affects the function of membrane proteins by binding to the specific site on the protein. Thus, some membrane proteins are proposed to be sensitive to their lipid environment.

A slightly different detailed molecular mechanism of how bilayer perturbation can influence the ion-channel was proposed in the same year. Oleamide (fatty acid amide of oleic acid) is an endogenous anaesthetic found in vivo (in the cat's brain) and it is known to potentiate sleep and lower the temperature of the body by closing the gap junction channel connexion. The detailed mechanism is shown on the picture: the well-ordered lipid(green)/cholesterol(yellow) ring that exists around connexon (magenta) becomes disordered on treatment with anaesthetic (red triangles), promoting a closure of connexon ion channel. This decreases brain activity and induces lethargy and anaesthetic effect.

Recently super resolution imaging showed direct experimental evidence that volatile anesthetic disrupt the ordered lipid domains as predicted. In the same study, a related mechanism emerged where the anesthetics released the enzyme phospholipase D

Phospholipase D (EC 3.1.4.4, lipophosphodiesterase II, lecithinase D, choline phosphatase, PLD; systematic name phosphatidylcholine phosphatidohydrolase) is an enzyme of the phospholipase superfamily that catalyses the following reaction

: a ph ...

(PLD) from lipid domains and the enzyme bound to and activated TREK-1

Potassium channel subfamily K member 2, also known as TREK-1, is a protein that in humans is encoded by the ''KCNK2'' gene.

This gene encodes K2P2.1, a lipid-gated ion channel belonging to the two-pore-domain background potassium channel protein ...

channel by the production of phosphatidic acid. These results showed experimentally that the membrane is a physiologically relevant target of general anesthetics.

Membrane protein hypothesis of general anaesthetic action

In the early 1980s, Nicholas P. Franks and William R. Lieb demonstrated that the Meyer-Overton correlation can be reproduced using a soluble protein. They found that two classes of proteins are inactivated by clinical doses of anaesthetic in the total absence of lipids. These are

In the early 1980s, Nicholas P. Franks and William R. Lieb demonstrated that the Meyer-Overton correlation can be reproduced using a soluble protein. They found that two classes of proteins are inactivated by clinical doses of anaesthetic in the total absence of lipids. These are luciferase

Luciferase is a generic term for the class of oxidative enzymes that produce bioluminescence, and is usually distinguished from a photoprotein. The name was first used by Raphaël Dubois who invented the words ''luciferin'' and ''luciferase'', ...

s, which are used by bioluminescent

Bioluminescence is the production and emission of light by living organisms. It is a form of chemiluminescence. Bioluminescence occurs widely in marine vertebrates and invertebrates, as well as in some Fungus, fungi, microorganisms including ...

animals and bacteria to produce light, and cytochrome P450

Cytochromes P450 (CYPs) are a Protein superfamily, superfamily of enzymes containing heme as a cofactor (biochemistry), cofactor that functions as monooxygenases. In mammals, these proteins oxidize steroids, fatty acids, and xenobiotics, and are ...

, which is a group of heme

Heme, or haem (pronounced / hi:m/ ), is a precursor to hemoglobin, which is necessary to bind oxygen in the bloodstream. Heme is biosynthesized in both the bone marrow and the liver.

In biochemical terms, heme is a coordination complex "consisti ...

proteins that hydroxylate a diverse group of compounds, including fatty acid

In chemistry, particularly in biochemistry, a fatty acid is a carboxylic acid with an aliphatic chain, which is either saturated or unsaturated. Most naturally occurring fatty acids have an unbranched chain of an even number of carbon atoms, fr ...

s, steroid

A steroid is a biologically active organic compound with four rings arranged in a specific molecular configuration. Steroids have two principal biological functions: as important components of cell membranes that alter membrane fluidity; and a ...

s, and xenobiotic

A xenobiotic is a chemical substance found within an organism that is not naturally produced or expected to be present within the organism. It can also cover substances that are present in much higher concentrations than are usual. Natural compo ...

s such as phenobarbital

Phenobarbital, also known as phenobarbitone or phenobarb, sold under the brand name Luminal among others, is a medication of the barbiturate type. It is recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) for the treatment of certain types of ep ...

. Remarkably, inhibition of these proteins by general anaesthetics was directly correlated with their anaesthetic potencies. Luciferase inhibition also exhibits a long-chain alcohol cutoff, which is related to the size of the anaesthetic-binding pocket.

These observations were important because they demonstrated that general anaesthetics may also interact with hydrophobic protein sites of certain proteins, rather than affect membrane proteins indirectly through nonspecific interactions with lipid bilayer as mediator. The sites are enzymatic surfaces that non specifically block the binding of the enzymes substrate. Whether anesthetics bind in a lock and key mechanism capable of initiating the large scale conformational changes that open ion channels and transporters has not yet been definitely demonstrated.

It was shown that anaesthetics alter the functions of many cytoplasmic signalling proteins, including protein kinase C

In cell biology, Protein kinase C, commonly abbreviated to PKC (EC 2.7.11.13), is a family of protein kinase enzymes that are involved in controlling the function of other proteins through the phosphorylation of hydroxyl groups of serine and t ...

, however, the proteins considered the most likely molecular targets of anaesthetics are ion channels. According to this theory general anaesthetics are much more selective than in the frame of lipid hypothesis and they bind directly only to small number of targets in the central nervous system mostly ligand-gated ion channel

Ligand-gated ion channels (LICs, LGIC), also commonly referred to as ionotropic receptors, are a group of transmembrane ion-channel proteins which open to allow ions such as Na+, K+, Ca2+, and/or Cl− to pass through the membrane in res ...

s in synapse

In the nervous system, a synapse is a structure that permits a neuron (or nerve cell) to pass an electrical or chemical signal to another neuron or to the target effector cell.

Synapses are essential to the transmission of nervous impulses from ...

s and G-protein coupled receptors

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), also known as seven-(pass)-transmembrane domain receptors, 7TM receptors, heptahelical receptors, serpentine receptors, and G protein-linked receptors (GPLR), form a large group of protein family, evolution ...

altering their ion flux. Particularly Cys-loop receptors are plausible targets for general anaesthetics that bind at the interface between the subunits. The Cys-loop receptor superfamily includes inhibitory receptors ( GABAA receptors, GABAC receptors, glycine receptor

The glycine receptor (abbreviated as GlyR or GLR) is the receptor of the amino acid neurotransmitter glycine. GlyR is an ionotropic receptor that produces its effects through chloride current. It is one of the most widely distributed inhibitory ...

s) and excitatory receptors (nicotinic acetylcholine receptor

Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, or nAChRs, are receptor polypeptides that respond to the neurotransmitter acetylcholine. Nicotinic receptors also respond to drugs such as the agonist nicotine. They are found in the central and peripheral ne ...

and 5-HT3 serotonin receptor). General anaesthetics can inhibit the channel functions of excitatory receptors or potentiate functions of inhibitory receptors, respectively.

A number of experimental and computational studies have shown that general anaesthetics could alter the dynamics in the flexible loops that connect α-helices in a bundle and are exposed to the membrane-water interface of Cys-loop receptors. The main binding pockets of general anaesthetics, however, are located within transmembrane four-α-helix bundles of Cys-loop receptors.

GABAA receptor is a major target of general anesthetics

The GABAA receptor (GABAAR) is an ionotropic receptor activated by the inhibitory neurotransmitter γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA).

Activation of the GABAA receptor leads to influx of

The GABAA receptor (GABAAR) is an ionotropic receptor activated by the inhibitory neurotransmitter γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA).

Activation of the GABAA receptor leads to influx of chloride ion

The chloride ion is the anion (negatively charged ion) Cl−. It is formed when the element chlorine (a halogen) gains an electron or when a compound such as hydrogen chloride is dissolved in water or other polar solvents. Chloride salts ...

s, which causes hyperpolarization of the neuronal membranes.

The GABAA receptor has been identified as the main target of intravenous anesthetics such as propofol

Propofol, marketed as Diprivan, among other names, is a short-acting medication that results in a decreased level of consciousness and a lack of memory for events. Its uses include the starting and maintenance of general anesthesia, sedation f ...

and etomidate

Etomidate (USAN, INN, BAN; marketed as Amidate) is a short-acting intravenous anaesthetic agent used for the induction of general anaesthesia and sedation for short procedures such as reduction of dislocated joints, tracheal intubation, cardiove ...

.

The binding site of propofol

Propofol, marketed as Diprivan, among other names, is a short-acting medication that results in a decreased level of consciousness and a lack of memory for events. Its uses include the starting and maintenance of general anesthesia, sedation f ...

on mammalian GABAA receptors has been identified by photolabeling using a diazirine

Diazirines are a class of organic molecules consisting of a carbon bound to two nitrogen atoms, which are double-bonded to each other, forming a cyclopropene-like ring, 3''H''-diazirene. They are isomeric with diazocarbon groups, and like them ...

derivative. Strong activation of tonic GABAA receptor conductance by clinical concentrations of propofol has been confirmed with electrophysiological recordings from hippocampal CA1 neurons in adult rat brain slice

The slice preparation or brain slice is a laboratory technique in electrophysiology that allows the study of a synapse or neural circuit in isolation from the rest of the brain, in controlled physiological conditions. Brain tissue is initially ...

s.

GABAA receptors that contain β3-subunits are the main molecular targets for the anesthetic actions of etomidate

Etomidate (USAN, INN, BAN; marketed as Amidate) is a short-acting intravenous anaesthetic agent used for the induction of general anaesthesia and sedation for short procedures such as reduction of dislocated joints, tracheal intubation, cardiove ...

, whereas the β2-containing GABAA receptors are involved in the sedation

Sedation is the reduction of irritability or agitation by administration of sedative drugs, generally to facilitate a medical procedure or diagnostic procedure. Examples of drugs which can be used for sedation include isoflurane, diethyl ether, ...

elicited by this drug. Electrophysiological experiments with amnestic concentrations of etomidate have also shown enhancement of tonic GABAA conductance of CA1 pyramidal neurons in hippocampal slices. Potent activation of GABAA receptor-mediated inhibition with resulting strong depression of firing rates of neocortical neurons has been also demonstrated for clinical concentrations of volatile anesthetics

An inhalational anesthetic is a chemical compound possessing general anesthetic properties that can be delivered via inhalation. They are administered through a face mask, laryngeal mask airway or tracheal tube connected to an anesthetic vapor ...

such as isoflurane

Isoflurane, sold under the brand name Forane among others, is a general anesthetic. It can be used to start or maintain anesthesia; however, other medications are often used to start anesthesia rather than isoflurane, due to airway irritation w ...

, enflurane

Enflurane (2-chloro-1,1,2-trifluoroethyl difluoromethyl ether) is a halogenated ether. Developed by Ross Terrell in 1963, it was first used clinically in 1966. It was increasingly used for inhalational anesthesia during the 1970s and 1980s but is ...

and halothane

Halothane, sold under the brand name Fluothane among others, is a general anaesthetic. It can be used to induce or maintain anaesthesia. One of its benefits is that it does not increase the production of saliva, which can be particularly useful i ...

.

Other molecular targets

The enhancement of GABAA receptor activity is unlikely to be the only mechanism to account for the wide range of behavioural effects of general anaesthetics. Accumulating experimental data suggests that modulation oftwo-pore domain potassium channel

The two-pore-domain or tandem pore domain potassium channels are a family of 15 members that form what is known as leak channels which possess Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz (open) rectification. These channels are regulated by several mechanisms including ...

s, or voltage-gated sodium channel

Sodium channels are integral membrane proteins that form ion channels, conducting sodium ions (Na+) through a cell's membrane. They belong to the superfamily of cation channels and can be classified according to the trigger that opens the channel ...

s may also account for some of the actions of volatile anaesthetic agents. Alternatively, inhibition of glutamate-gated N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor

The ''N''-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (also known as the NMDA receptor or NMDAR), is a glutamate receptor and ion channel found in neurons. The NMDA receptor is one of three types of ionotropic glutamate receptors, the other two being AMPA and ...

s by ketamine

Ketamine is a dissociative anesthetic used medically for induction and maintenance of anesthesia. It is also used as a recreational drug. It is one of the safest anesthetics, as, in contrast with opiates, ether, and propofol, it suppresses ne ...

, xenon

Xenon is a chemical element with the symbol Xe and atomic number 54. It is a dense, colorless, odorless noble gas found in Earth's atmosphere in trace amounts. Although generally unreactive, it can undergo a few chemical reactions such as the ...

, and nitrous oxide

Nitrous oxide (dinitrogen oxide or dinitrogen monoxide), commonly known as laughing gas, nitrous, or nos, is a chemical compound, an oxide of nitrogen with the formula . At room temperature, it is a colourless non-flammable gas, and has a ...

provides a mechanism of action in keeping with a predominant analgesic profile.

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Theories Of General Anaesthetic Action Anesthesia Membrane biology