Theorem on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In

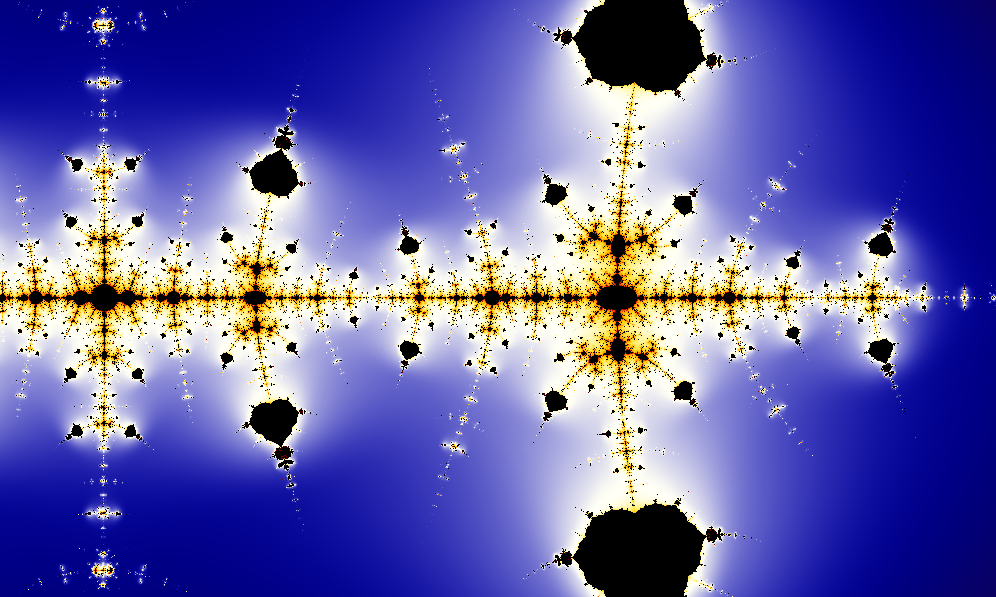

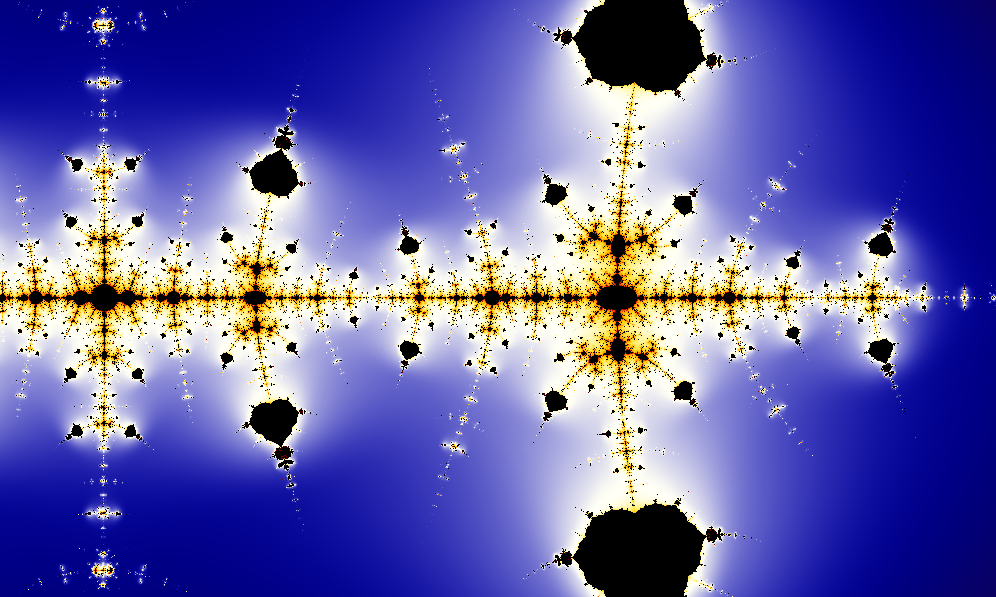

Some theorems are " trivial", in the sense that they follow from definitions, axioms, and other theorems in obvious ways and do not contain any surprising insights. Some, on the other hand, may be called "deep", because their proofs may be long and difficult, involve areas of mathematics superficially distinct from the statement of the theorem itself, or show surprising connections between disparate areas of mathematics. A theorem might be simple to state and yet be deep. An excellent example is

Some theorems are " trivial", in the sense that they follow from definitions, axioms, and other theorems in obvious ways and do not contain any surprising insights. Some, on the other hand, may be called "deep", because their proofs may be long and difficult, involve areas of mathematics superficially distinct from the statement of the theorem itself, or show surprising connections between disparate areas of mathematics. A theorem might be simple to state and yet be deep. An excellent example is

Nonetheless, there is some degree of empiricism and data collection involved in the discovery of mathematical theorems. By establishing a pattern, sometimes with the use of a powerful computer, mathematicians may have an idea of what to prove, and in some cases even a plan for how to set about doing the proof. It is also possible to find a single counter-example and so establish the impossibility of a proof for the proposition as-stated, and possibly suggest restricted forms of the original proposition that might have feasible proofs.

For example, both the

Nonetheless, there is some degree of empiricism and data collection involved in the discovery of mathematical theorems. By establishing a pattern, sometimes with the use of a powerful computer, mathematicians may have an idea of what to prove, and in some cases even a plan for how to set about doing the proof. It is also possible to find a single counter-example and so establish the impossibility of a proof for the proposition as-stated, and possibly suggest restricted forms of the original proposition that might have feasible proofs.

For example, both the

An enormous theorem: the classification of finite simple groups

Richard Elwes, Plus Magazine, Issue 41 December 2006. Another theorem of this type is the

For a theory to be closed under a derivability relation, it must be associated with a

For a theory to be closed under a derivability relation, it must be associated with a

Theorem of the Day

{{Authority control Logical consequence Logical expressions Mathematical proofs Mathematical terminology Statements Concepts in logic de:Theorem

mathematics

Mathematics is a field of study that discovers and organizes methods, Mathematical theory, theories and theorems that are developed and Mathematical proof, proved for the needs of empirical sciences and mathematics itself. There are many ar ...

and formal logic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the study of deductively valid inferences or logical truths. It examines how conclusions follow from premises based on the structure o ...

, a theorem is a statement that has been proven, or can be proven. The ''proof'' of a theorem is a logical argument

An argument is a series of Sentence (linguistics), sentences, Statement (logic), statements, or propositions some of which are called premises and one is the Logical consequence, conclusion. The purpose of an argument is to give Reason (argument) ...

that uses the inference rules of a deductive system

A formal system is an abstract structure and formalization of an axiomatic system used for deducing, using rules of inference, theorems from axioms.

In 1921, David Hilbert proposed to use formal systems as the foundation of knowledge in math ...

to establish that the theorem is a logical consequence

Logical consequence (also entailment or logical implication) is a fundamental concept in logic which describes the relationship between statement (logic), statements that hold true when one statement logically ''follows from'' one or more stat ...

of the axiom

An axiom, postulate, or assumption is a statement that is taken to be true, to serve as a premise or starting point for further reasoning and arguments. The word comes from the Ancient Greek word (), meaning 'that which is thought worthy or ...

s and previously proved theorems.

In mainstream mathematics, the axioms and the inference rules are commonly left implicit, and, in this case, they are almost always those of Zermelo–Fraenkel set theory

In set theory, Zermelo–Fraenkel set theory, named after mathematicians Ernst Zermelo and Abraham Fraenkel, is an axiomatic system that was proposed in the early twentieth century in order to formulate a theory of sets free of paradoxes suc ...

with the axiom of choice

In mathematics, the axiom of choice, abbreviated AC or AoC, is an axiom of set theory. Informally put, the axiom of choice says that given any collection of non-empty sets, it is possible to construct a new set by choosing one element from e ...

(ZFC), or of a less powerful theory, such as Peano arithmetic. Generally, an assertion that is explicitly called a theorem is a proved result that is not an immediate consequence of other known theorems. Moreover, many authors qualify as ''theorems'' only the most important results, and use the terms ''lemma'', ''proposition'' and ''corollary'' for less important theorems.

In mathematical logic

Mathematical logic is the study of Logic#Formal logic, formal logic within mathematics. Major subareas include model theory, proof theory, set theory, and recursion theory (also known as computability theory). Research in mathematical logic com ...

, the concepts of theorems and proofs have been formalized in order to allow mathematical reasoning about them. In this context, statements become well-formed formula

In mathematical logic, propositional logic and predicate logic, a well-formed formula, abbreviated WFF or wff, often simply formula, is a finite sequence of symbols from a given alphabet that is part of a formal language.

The abbreviation wf ...

s of some formal language

In logic, mathematics, computer science, and linguistics, a formal language is a set of strings whose symbols are taken from a set called "alphabet".

The alphabet of a formal language consists of symbols that concatenate into strings (also c ...

. A theory

A theory is a systematic and rational form of abstract thinking about a phenomenon, or the conclusions derived from such thinking. It involves contemplative and logical reasoning, often supported by processes such as observation, experimentation, ...

consists of some basis statements called ''axioms'', and some ''deducing rules'' (sometimes included in the axioms). The theorems of the theory are the statements that can be derived from the axioms by using the deducing rules. This formalization led to proof theory

Proof theory is a major branchAccording to , proof theory is one of four domains mathematical logic, together with model theory, axiomatic set theory, and recursion theory. consists of four corresponding parts, with part D being about "Proof The ...

, which allows proving general theorems about theorems and proofs. In particular, Gödel's incompleteness theorems

Gödel's incompleteness theorems are two theorems of mathematical logic that are concerned with the limits of in formal axiomatic theories. These results, published by Kurt Gödel in 1931, are important both in mathematical logic and in the phi ...

show that every consistent

In deductive logic, a consistent theory is one that does not lead to a logical contradiction. A theory T is consistent if there is no formula \varphi such that both \varphi and its negation \lnot\varphi are elements of the set of consequences ...

theory containing the natural numbers has true statements on natural numbers that are not theorems of the theory (that is they cannot be proved inside the theory).

As the axioms are often abstractions of properties of the physical world

The universe is all of space and time and their contents. It comprises all of existence, any fundamental interaction, physical process and physical constant, and therefore all forms of matter and energy, and the structures they form, from s ...

, theorems may be considered as expressing some truth, but in contrast to the notion of a scientific law

Scientific laws or laws of science are statements, based on repeated experiments or observations, that describe or predict a range of natural phenomena. The term ''law'' has diverse usage in many cases (approximate, accurate, broad, or narrow ...

, which is ''experimental

An experiment is a procedure carried out to support or refute a hypothesis, or determine the efficacy or likelihood of something previously untried. Experiments provide insight into cause-and-effect by demonstrating what outcome occurs whe ...

'', the justification of the truth of a theorem is purely deductive

Deductive reasoning is the process of drawing valid inferences. An inference is valid if its conclusion follows logically from its premises, meaning that it is impossible for the premises to be true and the conclusion to be false. For example, th ...

.

A ''conjecture

In mathematics, a conjecture is a conclusion or a proposition that is proffered on a tentative basis without proof. Some conjectures, such as the Riemann hypothesis or Fermat's conjecture (now a theorem, proven in 1995 by Andrew Wiles), ha ...

'' is a tentative proposition that may evolve to become a theorem if proven true.

Theoremhood and truth

Until the end of the 19th century and thefoundational crisis of mathematics

Foundations of mathematics are the logical and mathematical framework that allows the development of mathematics without generating self-contradictory theories, and to have reliable concepts of theorems, proofs, algorithms, etc. in particul ...

, all mathematical theories were built from a few basic properties that were considered as self-evident; for example, the facts that every natural number

In mathematics, the natural numbers are the numbers 0, 1, 2, 3, and so on, possibly excluding 0. Some start counting with 0, defining the natural numbers as the non-negative integers , while others start with 1, defining them as the positive in ...

has a successor, and that there is exactly one line that passes through two given distinct points. These basic properties that were considered as absolutely evident were called postulates or axioms

An axiom, postulate, or assumption is a statement that is taken to be true, to serve as a premise or starting point for further reasoning and arguments. The word comes from the Ancient Greek word (), meaning 'that which is thought worthy or f ...

; for example Euclid's postulates. All theorems were proved by using implicitly or explicitly these basic properties, and, because of the evidence of these basic properties, a proved theorem was considered as a definitive truth, unless there was an error in the proof. For example, the sum of the interior angles of a triangle

A triangle is a polygon with three corners and three sides, one of the basic shapes in geometry. The corners, also called ''vertices'', are zero-dimensional points while the sides connecting them, also called ''edges'', are one-dimension ...

equals 180°, and this was considered as an undoubtable fact.

One aspect of the foundational crisis of mathematics was the discovery of non-Euclidean geometries

In mathematics, non-Euclidean geometry consists of two geometries based on axioms closely related to those that specify Euclidean geometry. As Euclidean geometry lies at the intersection of metric geometry and affine geometry, non-Euclidean geo ...

that do not lead to any contradiction, although, in such geometries, the sum of the angles of a triangle is different from 180°. So, the property ''"the sum of the angles of a triangle equals 180°"'' is either true or false, depending whether Euclid's fifth postulate is assumed or denied. Similarly, the use of "evident" basic properties of sets leads to the contradiction of Russell's paradox

In mathematical logic, Russell's paradox (also known as Russell's antinomy) is a set-theoretic paradox published by the British philosopher and mathematician, Bertrand Russell, in 1901. Russell's paradox shows that every set theory that contains ...

. This has been resolved by elaborating the rules that are allowed for manipulating sets.

This crisis has been resolved by revisiting the foundations of mathematics to make them more rigorous. In these new foundations, a theorem is a well-formed formula

In mathematical logic, propositional logic and predicate logic, a well-formed formula, abbreviated WFF or wff, often simply formula, is a finite sequence of symbols from a given alphabet that is part of a formal language.

The abbreviation wf ...

of a mathematical theory

A theory is a systematic and rational form of abstract thinking about a phenomenon, or the conclusions derived from such thinking. It involves contemplative and logical reasoning, often supported by processes such as observation, experimentation, ...

that can be proved from the axiom

An axiom, postulate, or assumption is a statement that is taken to be true, to serve as a premise or starting point for further reasoning and arguments. The word comes from the Ancient Greek word (), meaning 'that which is thought worthy or ...

s and inference rules of the theory. So, the above theorem on the sum of the angles of a triangle becomes: ''Under the axioms and inference rules of Euclidean geometry

Euclidean geometry is a mathematical system attributed to ancient Greek mathematics, Greek mathematician Euclid, which he described in his textbook on geometry, ''Euclid's Elements, Elements''. Euclid's approach consists in assuming a small set ...

, the sum of the interior angles of a triangle equals 180°''. Similarly, Russell's paradox disappears because, in an axiomatized set theory, the ''set of all sets'' cannot be expressed with a well-formed formula. More precisely, if the set of all sets can be expressed with a well-formed formula, this implies that the theory is inconsistent, and every well-formed assertion, as well as its negation, is a theorem.

In this context, the validity of a theorem depends only on the correctness of its proof. It is independent from the truth, or even the significance of the axioms. This does not mean that the significance of the axioms is uninteresting, but only that the validity of a theorem is independent from the significance of the axioms. This independence may be useful by allowing the use of results of some area of mathematics in apparently unrelated areas.

An important consequence of this way of thinking about mathematics is that it allows defining mathematical theories and theorems as mathematical object

A mathematical object is an abstract concept arising in mathematics. Typically, a mathematical object can be a value that can be assigned to a Glossary of mathematical symbols, symbol, and therefore can be involved in formulas. Commonly encounter ...

s, and to prove theorems about them. Examples are Gödel's incompleteness theorems

Gödel's incompleteness theorems are two theorems of mathematical logic that are concerned with the limits of in formal axiomatic theories. These results, published by Kurt Gödel in 1931, are important both in mathematical logic and in the phi ...

. In particular, there are well-formed assertions than can be proved to not be a theorem of the ambient theory, although they can be proved in a wider theory. An example is Goodstein's theorem, which can be stated in Peano arithmetic, but is proved to be not provable in Peano arithmetic. However, it is provable in some more general theories, such as Zermelo–Fraenkel set theory

In set theory, Zermelo–Fraenkel set theory, named after mathematicians Ernst Zermelo and Abraham Fraenkel, is an axiomatic system that was proposed in the early twentieth century in order to formulate a theory of sets free of paradoxes suc ...

.

Epistemological considerations

Many mathematical theorems are conditional statements, whose proofs deduce conclusions from conditions known as hypotheses orpremise

A premise or premiss is a proposition—a true or false declarative statement—used in an argument to prove the truth of another proposition called the conclusion. Arguments consist of a set of premises and a conclusion.

An argument is meaningf ...

s. In light of the interpretation of proof as justification of truth, the conclusion is often viewed as a necessary consequence of the hypotheses. Namely, that the conclusion is true in case the hypotheses are true—without any further assumptions. However, the conditional could also be interpreted differently in certain deductive system

A formal system is an abstract structure and formalization of an axiomatic system used for deducing, using rules of inference, theorems from axioms.

In 1921, David Hilbert proposed to use formal systems as the foundation of knowledge in math ...

s, depending on the meanings assigned to the derivation rules and the conditional symbol (e.g., non-classical logic

Non-classical logics (and sometimes alternative logics or non-Aristotelian logics) are formal systems that differ in a significant way from standard logical systems such as propositional and predicate logic. There are several ways in which this ...

).

Although theorems can be written in a completely symbolic form (e.g., as propositions in propositional calculus

The propositional calculus is a branch of logic. It is also called propositional logic, statement logic, sentential calculus, sentential logic, or sometimes zeroth-order logic. Sometimes, it is called ''first-order'' propositional logic to contra ...

), they are often expressed informally in a natural language such as English for better readability. The same is true of proofs, which are often expressed as logically organized and clearly worded informal arguments, intended to convince readers of the truth of the statement of the theorem beyond any doubt, and from which a formal symbolic proof can in principle be constructed.

In addition to the better readability, informal arguments are typically easier to check than purely symbolic ones—indeed, many mathematicians would express a preference for a proof that not only demonstrates the validity of a theorem, but also explains in some way ''why'' it is obviously true. In some cases, one might even be able to substantiate a theorem by using a picture as its proof.

Because theorems lie at the core of mathematics, they are also central to its aesthetics

Aesthetics (also spelled esthetics) is the branch of philosophy concerned with the nature of beauty and taste (sociology), taste, which in a broad sense incorporates the philosophy of art.Slater, B. H.Aesthetics ''Internet Encyclopedia of Ph ...

. Theorems are often described as being "trivial", or "difficult", or "deep", or even "beautiful". These subjective judgments vary not only from person to person, but also with time and culture: for example, as a proof is obtained, simplified or better understood, a theorem that was once difficult may become trivial. On the other hand, a deep theorem may be stated simply, but its proof may involve surprising and subtle connections between disparate areas of mathematics. Fermat's Last Theorem

In number theory, Fermat's Last Theorem (sometimes called Fermat's conjecture, especially in older texts) states that no three positive number, positive integers , , and satisfy the equation for any integer value of greater than . The cases ...

is a particularly well-known example of such a theorem.

Informal account of theorems

Logically, many theorems are of the form of anindicative conditional

In natural languages, an indicative conditional is a conditional sentence such as "If Leona is at home, she isn't in Paris", whose grammatical form restricts it to discussing what could be true. Indicatives are typically defined in opposition to c ...

: ''If A, then B''. Such a theorem does not assert ''B'' — only that ''B'' is a necessary consequence of ''A''. In this case, ''A'' is called the ''hypothesis'' of the theorem ("hypothesis" here means something very different from a conjecture

In mathematics, a conjecture is a conclusion or a proposition that is proffered on a tentative basis without proof. Some conjectures, such as the Riemann hypothesis or Fermat's conjecture (now a theorem, proven in 1995 by Andrew Wiles), ha ...

), and ''B'' the ''conclusion'' of the theorem. The two together (without the proof) are called the ''proposition'' or ''statement'' of the theorem (e.g. "''If A, then B''" is the ''proposition''). Alternatively, ''A'' and ''B'' can be also termed the '' antecedent'' and the '' consequent'', respectively. The theorem "If ''n'' is an even natural number

In mathematics, the natural numbers are the numbers 0, 1, 2, 3, and so on, possibly excluding 0. Some start counting with 0, defining the natural numbers as the non-negative integers , while others start with 1, defining them as the positive in ...

, then ''n''/2 is a natural number" is a typical example in which the hypothesis is "''n'' is an even natural number", and the conclusion is "''n''/2 is also a natural number".

In order for a theorem to be proved, it must be in principle expressible as a precise, formal statement. However, theorems are usually expressed in natural language rather than in a completely symbolic form—with the presumption that a formal statement can be derived from the informal one.

It is common in mathematics to choose a number of hypotheses within a given language and declare that the theory consists of all statements provable from these hypotheses. These hypotheses form the foundational basis of the theory and are called axiom

An axiom, postulate, or assumption is a statement that is taken to be true, to serve as a premise or starting point for further reasoning and arguments. The word comes from the Ancient Greek word (), meaning 'that which is thought worthy or ...

s or postulates. The field of mathematics known as proof theory

Proof theory is a major branchAccording to , proof theory is one of four domains mathematical logic, together with model theory, axiomatic set theory, and recursion theory. consists of four corresponding parts, with part D being about "Proof The ...

studies formal languages, axioms and the structure of proofs.

Fermat's Last Theorem

In number theory, Fermat's Last Theorem (sometimes called Fermat's conjecture, especially in older texts) states that no three positive number, positive integers , , and satisfy the equation for any integer value of greater than . The cases ...

, and there are many other examples of simple yet deep theorems in number theory

Number theory is a branch of pure mathematics devoted primarily to the study of the integers and arithmetic functions. Number theorists study prime numbers as well as the properties of mathematical objects constructed from integers (for example ...

and combinatorics

Combinatorics is an area of mathematics primarily concerned with counting, both as a means and as an end to obtaining results, and certain properties of finite structures. It is closely related to many other areas of mathematics and has many ...

, among other areas.

Other theorems have a known proof that cannot easily be written down. The most prominent examples are the four color theorem and the Kepler conjecture. Both of these theorems are only known to be true by reducing them to a computational search that is then verified by a computer program. Initially, many mathematicians did not accept this form of proof, but it has become more widely accepted. The mathematician Doron Zeilberger has even gone so far as to claim that these are possibly the only nontrivial results that mathematicians have ever proved. Many mathematical theorems can be reduced to more straightforward computation, including polynomial identities, trigonometric identities and hypergeometric identities.

Relation with scientific theories

Theorems in mathematics and theories in science are fundamentally different in theirepistemology

Epistemology is the branch of philosophy that examines the nature, origin, and limits of knowledge. Also called "the theory of knowledge", it explores different types of knowledge, such as propositional knowledge about facts, practical knowle ...

. A scientific theory cannot be proved; its key attribute is that it is falsifiable, that is, it makes predictions about the natural world that are testable by experiment

An experiment is a procedure carried out to support or refute a hypothesis, or determine the efficacy or likelihood of something previously untried. Experiments provide insight into cause-and-effect by demonstrating what outcome occurs whe ...

s. Any disagreement between prediction and experiment demonstrates the incorrectness of the scientific theory, or at least limits its accuracy or domain of validity. Mathematical theorems, on the other hand, are purely abstract formal statements: the proof of a theorem cannot involve experiments or other empirical evidence in the same way such evidence is used to support scientific theories.

Nonetheless, there is some degree of empiricism and data collection involved in the discovery of mathematical theorems. By establishing a pattern, sometimes with the use of a powerful computer, mathematicians may have an idea of what to prove, and in some cases even a plan for how to set about doing the proof. It is also possible to find a single counter-example and so establish the impossibility of a proof for the proposition as-stated, and possibly suggest restricted forms of the original proposition that might have feasible proofs.

For example, both the

Nonetheless, there is some degree of empiricism and data collection involved in the discovery of mathematical theorems. By establishing a pattern, sometimes with the use of a powerful computer, mathematicians may have an idea of what to prove, and in some cases even a plan for how to set about doing the proof. It is also possible to find a single counter-example and so establish the impossibility of a proof for the proposition as-stated, and possibly suggest restricted forms of the original proposition that might have feasible proofs.

For example, both the Collatz conjecture

The Collatz conjecture is one of the most famous List of unsolved problems in mathematics, unsolved problems in mathematics. The conjecture asks whether repeating two simple arithmetic operations will eventually transform every positive integer ...

and the Riemann hypothesis

In mathematics, the Riemann hypothesis is the conjecture that the Riemann zeta function has its zeros only at the negative even integers and complex numbers with real part . Many consider it to be the most important unsolved problem in pure ...

are well-known unsolved problems; they have been extensively studied through empirical checks, but remain unproven. The Collatz conjecture

The Collatz conjecture is one of the most famous List of unsolved problems in mathematics, unsolved problems in mathematics. The conjecture asks whether repeating two simple arithmetic operations will eventually transform every positive integer ...

has been verified for start values up to about 2.88 × 1018. The Riemann hypothesis

In mathematics, the Riemann hypothesis is the conjecture that the Riemann zeta function has its zeros only at the negative even integers and complex numbers with real part . Many consider it to be the most important unsolved problem in pure ...

has been verified to hold for the first 10 trillion non-trivial zeroes of the zeta function. Although most mathematicians can tolerate supposing that the conjecture and the hypothesis are true, neither of these propositions is considered proved.

Such evidence does not constitute proof. For example, the Mertens conjecture is a statement about natural numbers that is now known to be false, but no explicit counterexample (i.e., a natural number ''n'' for which the Mertens function ''M''(''n'') equals or exceeds the square root of ''n'') is known: all numbers less than 1014 have the Mertens property, and the smallest number that does not have this property is only known to be less than the exponential of 1.59 × 1040, which is approximately 10 to the power 4.3 × 1039. Since the number of particles in the universe is generally considered less than 10 to the power 100 (a googol

A googol is the large number 10100 or ten to the power of one hundred. In decimal notation, it is written as the digit 1 followed by one hundred zeros: 10,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000, ...

), there is no hope to find an explicit counterexample by exhaustive search.

The word "theory" also exists in mathematics, to denote a body of mathematical axioms, definitions and theorems, as in, for example, group theory

In abstract algebra, group theory studies the algebraic structures known as group (mathematics), groups.

The concept of a group is central to abstract algebra: other well-known algebraic structures, such as ring (mathematics), rings, field ( ...

(see mathematical theory

A theory is a systematic and rational form of abstract thinking about a phenomenon, or the conclusions derived from such thinking. It involves contemplative and logical reasoning, often supported by processes such as observation, experimentation, ...

). There are also "theorems" in science, particularly physics, and in engineering, but they often have statements and proofs in which physical assumptions and intuition play an important role; the physical axioms on which such "theorems" are based are themselves falsifiable.

Terminology

A number of different terms for mathematical statements exist; these terms indicate the role statements play in a particular subject. The distinction between different terms is sometimes rather arbitrary, and the usage of some terms has evolved over time. * An ''axiom

An axiom, postulate, or assumption is a statement that is taken to be true, to serve as a premise or starting point for further reasoning and arguments. The word comes from the Ancient Greek word (), meaning 'that which is thought worthy or ...

'' or ''postulate'' is a fundamental assumption regarding the object of study, that is accepted without proof. A related concept is that of a ''definition

A definition is a statement of the meaning of a term (a word, phrase, or other set of symbols). Definitions can be classified into two large categories: intensional definitions (which try to give the sense of a term), and extensional definitio ...

'', which gives the meaning of a word or a phrase in terms of known concepts. Classical geometry discerns between axioms, which are general statements; and postulates, which are statements about geometrical objects. Historically, axioms were regarded as " self-evident"; today they are merely ''assumed'' to be true.

* A ''conjecture

In mathematics, a conjecture is a conclusion or a proposition that is proffered on a tentative basis without proof. Some conjectures, such as the Riemann hypothesis or Fermat's conjecture (now a theorem, proven in 1995 by Andrew Wiles), ha ...

'' is an unproved statement that is believed to be true. Conjectures are usually made in public, and named after their maker (for example, Goldbach's conjecture

Goldbach's conjecture is one of the oldest and best-known list of unsolved problems in mathematics, unsolved problems in number theory and all of mathematics. It states that every even and odd numbers, even natural number greater than 2 is the ...

and Collatz conjecture

The Collatz conjecture is one of the most famous List of unsolved problems in mathematics, unsolved problems in mathematics. The conjecture asks whether repeating two simple arithmetic operations will eventually transform every positive integer ...

). The term ''hypothesis'' is also used in this sense (for example, Riemann hypothesis

In mathematics, the Riemann hypothesis is the conjecture that the Riemann zeta function has its zeros only at the negative even integers and complex numbers with real part . Many consider it to be the most important unsolved problem in pure ...

), which should not be confused with "hypothesis" as the premise of a proof. Other terms are also used on occasion, for example ''problem'' when people are not sure whether the statement should be believed to be true. Fermat's Last Theorem

In number theory, Fermat's Last Theorem (sometimes called Fermat's conjecture, especially in older texts) states that no three positive number, positive integers , , and satisfy the equation for any integer value of greater than . The cases ...

was historically called a theorem, although, for centuries, it was only a conjecture.

* A ''theorem'' is a statement that has been proven to be true based on axioms and other theorems.

* A ''proposition

A proposition is a statement that can be either true or false. It is a central concept in the philosophy of language, semantics, logic, and related fields. Propositions are the object s denoted by declarative sentences; for example, "The sky ...

'' is a theorem of lesser importance, or one that is considered so elementary or immediately obvious, that it may be stated without proof. This should not be confused with "proposition" as used in propositional logic

The propositional calculus is a branch of logic. It is also called propositional logic, statement logic, sentential calculus, sentential logic, or sometimes zeroth-order logic. Sometimes, it is called ''first-order'' propositional logic to contra ...

. In classical geometry the term "proposition" was used differently: in Euclid

Euclid (; ; BC) was an ancient Greek mathematician active as a geometer and logician. Considered the "father of geometry", he is chiefly known for the '' Elements'' treatise, which established the foundations of geometry that largely domina ...

's ''Elements'' (), all theorems and geometric constructions were called "propositions" regardless of their importance.

* A '' lemma'' is an "accessory proposition" - a proposition with little applicability outside its use in a particular proof. Over time a lemma may gain in importance and be considered a ''theorem'', though the term "lemma" is usually kept as part of its name (e.g. Gauss's lemma, Zorn's lemma

Zorn's lemma, also known as the Kuratowski–Zorn lemma, is a proposition of set theory. It states that a partially ordered set containing upper bounds for every chain (that is, every totally ordered subset) necessarily contains at least on ...

, and the fundamental lemma).

* A ''corollary

In mathematics and logic, a corollary ( , ) is a theorem of less importance which can be readily deduced from a previous, more notable statement. A corollary could, for instance, be a proposition which is incidentally proved while proving another ...

'' is a proposition that follows immediately from another theorem or axiom, with little or no required proof. A corollary may also be a restatement of a theorem in a simpler form, or for a special case: for example, the theorem "all internal angles in a rectangle

In Euclidean geometry, Euclidean plane geometry, a rectangle is a Rectilinear polygon, rectilinear convex polygon or a quadrilateral with four right angles. It can also be defined as: an equiangular quadrilateral, since equiangular means that a ...

are right angle

In geometry and trigonometry, a right angle is an angle of exactly 90 Degree (angle), degrees or radians corresponding to a quarter turn (geometry), turn. If a Line (mathematics)#Ray, ray is placed so that its endpoint is on a line and the ad ...

s" has a corollary that "all internal angles in a ''square

In geometry, a square is a regular polygon, regular quadrilateral. It has four straight sides of equal length and four equal angles. Squares are special cases of rectangles, which have four equal angles, and of rhombuses, which have four equal si ...

'' are right angle

In geometry and trigonometry, a right angle is an angle of exactly 90 Degree (angle), degrees or radians corresponding to a quarter turn (geometry), turn. If a Line (mathematics)#Ray, ray is placed so that its endpoint is on a line and the ad ...

s" - a square being a special case of a rectangle.

* A ''generalization

A generalization is a form of abstraction whereby common properties of specific instances are formulated as general concepts or claims. Generalizations posit the existence of a domain or set of elements, as well as one or more common characteri ...

'' of a theorem is a theorem with a similar statement but a broader scope, from which the original theorem can be deduced as a special case (a ''corollary'').

Other terms may also be used for historical or customary reasons, for example:

* An '' identity'' is a theorem stating an equality between two expressions, that holds for any value within its domain (e.g. Bézout's identity

In mathematics, Bézout's identity (also called Bézout's lemma), named after Étienne Bézout who proved it for polynomials, is the following theorem:

Here the greatest common divisor of and is taken to be . The integers and are called B� ...

and Vandermonde's identity).

* A ''rule'' is a theorem that establishes a useful formula (e.g. Bayes' rule and Cramer's rule

In linear algebra, Cramer's rule is an explicit formula for the solution of a system of linear equations with as many equations as unknowns, valid whenever the system has a unique solution. It expresses the solution in terms of the determinants of ...

).

* A ''law

Law is a set of rules that are created and are enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior, with its precise definition a matter of longstanding debate. It has been variously described as a science and as the ar ...

'' or ''principle

A principle may relate to a fundamental truth or proposition that serves as the foundation for a system of beliefs or behavior or a chain of reasoning. They provide a guide for behavior or evaluation. A principle can make values explicit, so t ...

'' is a theorem with wide applicability (e.g. the law of large numbers, law of cosines

In trigonometry, the law of cosines (also known as the cosine formula or cosine rule) relates the lengths of the sides of a triangle to the cosine of one of its angles. For a triangle with sides , , and , opposite respective angles , , and (see ...

, Kolmogorov's zero–one law, Harnack's principle, the least-upper-bound principle, and the pigeonhole principle

In mathematics, the pigeonhole principle states that if items are put into containers, with , then at least one container must contain more than one item. For example, of three gloves, at least two must be right-handed or at least two must be l ...

).

A few well-known theorems have even more idiosyncratic names, for example, the division algorithm

A division algorithm is an algorithm which, given two integers ''N'' and ''D'' (respectively the numerator and the denominator), computes their quotient and/or remainder, the result of Euclidean division. Some are applied by hand, while others ar ...

, Euler's formula, and the Banach–Tarski paradox

The Banach–Tarski paradox is a theorem in set-theoretic geometry, which states the following: Given a solid ball in three-dimensional space, there exists a decomposition of the ball into a finite number of disjoint subsets, which can then ...

.

Layout

A theorem and its proof are typically laid out as follows: :''Theorem'' (name of the person who proved it, along with year of discovery or publication of the proof) :''Statement of theorem (sometimes called the ''proposition'')'' :''Proof'' :''Description of proof'' :''End'' The end of the proof may be signaled by the lettersQ.E.D.

Q.E.D. or QED is an initialism of the List of Latin phrases (full), Latin phrase , meaning "that which was to be demonstrated". Literally, it states "what was to be shown". Traditionally, the abbreviation is placed at the end of Mathematical proof ...

(''quod erat demonstrandum'') or by one of the tombstone marks, such as "□" or "∎", meaning "end of proof", introduced by Paul Halmos

Paul Richard Halmos (; 3 March 1916 – 2 October 2006) was a Kingdom of Hungary, Hungarian-born United States, American mathematician and probabilist who made fundamental advances in the areas of mathematical logic, probability theory, operat ...

following their use in magazines to mark the end of an article.

The exact style depends on the author or publication. Many publications provide instructions or macros for typesetting in the house style.

It is common for a theorem to be preceded by definition

A definition is a statement of the meaning of a term (a word, phrase, or other set of symbols). Definitions can be classified into two large categories: intensional definitions (which try to give the sense of a term), and extensional definitio ...

s describing the exact meaning of the terms used in the theorem. It is also common for a theorem to be preceded by a number of ''propositions'' or ''lemmas'' which are then used in the proof. However, lemmas are sometimes embedded in the proof of a theorem, either with nested proofs, or with their proofs presented after the proof of the theorem.

Corollaries to a theorem are either presented between the theorem and the proof, or directly after the proof. Sometimes, corollaries have proofs of their own that explain why they follow from the theorem.

Lore

It has been estimated that over a quarter of a million theorems are proved every year. The well-known aphorism, "A mathematician is a device for turning coffee into theorems", is probably due to Alfréd Rényi, although it is often attributed to Rényi's colleague Paul Erdős (and Rényi may have been thinking of Erdős), who was famous for the many theorems he produced, thenumber

A number is a mathematical object used to count, measure, and label. The most basic examples are the natural numbers 1, 2, 3, 4, and so forth. Numbers can be represented in language with number words. More universally, individual numbers can ...

of his collaborations, and his coffee drinking.

The classification of finite simple groups

In mathematics, the classification of finite simple groups (popularly called the enormous theorem) is a result of group theory stating that every List of finite simple groups, finite simple group is either cyclic group, cyclic, or alternating gro ...

is regarded by some to be the longest proof of a theorem. It comprises tens of thousands of pages in 500 journal articles by some 100 authors. These papers are together believed to give a complete proof, and several ongoing projects hope to shorten and simplify this proof.Richard Elwes, Plus Magazine, Issue 41 December 2006. Another theorem of this type is the

four color theorem

In mathematics, the four color theorem, or the four color map theorem, states that no more than four colors are required to color the regions of any map so that no two adjacent regions have the same color. ''Adjacent'' means that two regions shar ...

whose computer generated proof is too long for a human to read. It is among the longest known proofs of a theorem whose statement can be easily understood by a layman.

Theorems in logic

Inmathematical logic

Mathematical logic is the study of Logic#Formal logic, formal logic within mathematics. Major subareas include model theory, proof theory, set theory, and recursion theory (also known as computability theory). Research in mathematical logic com ...

, a formal theory is a set of sentences within a formal language

In logic, mathematics, computer science, and linguistics, a formal language is a set of strings whose symbols are taken from a set called "alphabet".

The alphabet of a formal language consists of symbols that concatenate into strings (also c ...

. A sentence is a well-formed formula

In mathematical logic, propositional logic and predicate logic, a well-formed formula, abbreviated WFF or wff, often simply formula, is a finite sequence of symbols from a given alphabet that is part of a formal language.

The abbreviation wf ...

with no free variables. A sentence that is a member of a theory is one of its theorems, and the theory is the set of its theorems. Usually a theory is understood to be closed under the relation of logical consequence

Logical consequence (also entailment or logical implication) is a fundamental concept in logic which describes the relationship between statement (logic), statements that hold true when one statement logically ''follows from'' one or more stat ...

. Some accounts define a theory to be closed under the semantic consequence relation (), while others define it to be closed under the syntactic consequence, or derivability relation ().

deductive system

A formal system is an abstract structure and formalization of an axiomatic system used for deducing, using rules of inference, theorems from axioms.

In 1921, David Hilbert proposed to use formal systems as the foundation of knowledge in math ...

that specifies how the theorems are derived. The deductive system may be stated explicitly, or it may be clear from the context. The closure of the empty set under the relation of logical consequence yields the set that contains just those sentences that are the theorems of the deductive system.

In the broad sense in which the term is used within logic, a theorem does not have to be true, since the theory that contains it may be unsound relative to a given semantics, or relative to the standard interpretation of the underlying language. A theory that is inconsistent has all sentences as theorems.

The definition of theorems as sentences of a formal language is useful within proof theory

Proof theory is a major branchAccording to , proof theory is one of four domains mathematical logic, together with model theory, axiomatic set theory, and recursion theory. consists of four corresponding parts, with part D being about "Proof The ...

, which is a branch of mathematics that studies the structure of formal proofs and the structure of provable formulas. It is also important in model theory

In mathematical logic, model theory is the study of the relationship between theory (mathematical logic), formal theories (a collection of Sentence (mathematical logic), sentences in a formal language expressing statements about a Structure (mat ...

, which is concerned with the relationship between formal theories and structures that are able to provide a semantics for them through interpretation.

Although theorems may be uninterpreted sentences, in practice mathematicians are more interested in the meanings of the sentences, i.e. in the propositions they express. What makes formal theorems useful and interesting is that they may be interpreted as true propositions and their derivations may be interpreted as a proof of their truth. A theorem whose interpretation is a true statement ''about'' a formal system (as opposed to ''within'' a formal system) is called a ''metatheorem

In logic, a metatheorem is a statement about a formal system proven in a metalanguage. Unlike theorems proved within a given formal system, a metatheorem is proved within a metatheory, and may reference concepts that are present in the metatheo ...

''.

Some important theorems in mathematical logic are:

* Compactness of first-order logic

* Completeness of first-order logic

* Gödel's incompleteness theorems of first-order arithmetic

* Consistency of first-order arithmetic

* Tarski's undefinability theorem

* Church-Turing theorem of undecidability

* Löb's theorem

* Löwenheim–Skolem theorem

In mathematical logic, the Löwenheim–Skolem theorem is a theorem on the existence and cardinality of models, named after Leopold Löwenheim and Thoralf Skolem.

The precise formulation is given below. It implies that if a countable first-order ...

* Lindström's theorem

* Craig's theorem

* Cut-elimination theorem

Syntax and semantics

The concept of a formal theorem is fundamentally syntactic, in contrast to the notion of a ''true proposition,'' which introducessemantics

Semantics is the study of linguistic Meaning (philosophy), meaning. It examines what meaning is, how words get their meaning, and how the meaning of a complex expression depends on its parts. Part of this process involves the distinction betwee ...

. Different deductive systems can yield other interpretations, depending on the presumptions of the derivation rules (i.e. belief

A belief is a subjective Attitude (psychology), attitude that something is truth, true or a State of affairs (philosophy), state of affairs is the case. A subjective attitude is a mental state of having some Life stance, stance, take, or opinion ...

, justification or other modalities). The soundness

In logic and deductive reasoning, an argument is sound if it is both Validity (logic), valid in form and has no false premises. Soundness has a related meaning in mathematical logic, wherein a Formal system, formal system of logic is sound if and o ...

of a formal system depends on whether or not all of its theorems are also validities. A validity is a formula that is true under any possible interpretation (for example, in classical propositional logic, validities are tautologies). A formal system is considered semantically complete when all of its theorems are also tautologies.

Interpretation of a formal theorem

Theorems and theories

See also

* Law (mathematics) * List of theorems * List of theorems called fundamental *Formula

In science, a formula is a concise way of expressing information symbolically, as in a mathematical formula or a ''chemical formula''. The informal use of the term ''formula'' in science refers to the general construct of a relationship betwe ...

*Inference

Inferences are steps in logical reasoning, moving from premises to logical consequences; etymologically, the word '' infer'' means to "carry forward". Inference is theoretically traditionally divided into deduction and induction, a distinct ...

* Toy theorem

Citations

Notes

References

Works cited

* * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * *External links

* *Theorem of the Day

{{Authority control Logical consequence Logical expressions Mathematical proofs Mathematical terminology Statements Concepts in logic de:Theorem