The Unabomber on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Theodore John Kaczynski ( ; born May 22, 1942), also known as the Unabomber (), is an American

Theodore John Kaczynski was born in

Theodore John Kaczynski was born in

Kaczynski attended Evergreen Park Community High School, where he excelled academically. He played the

Kaczynski attended Evergreen Park Community High School, where he excelled academically. He played the

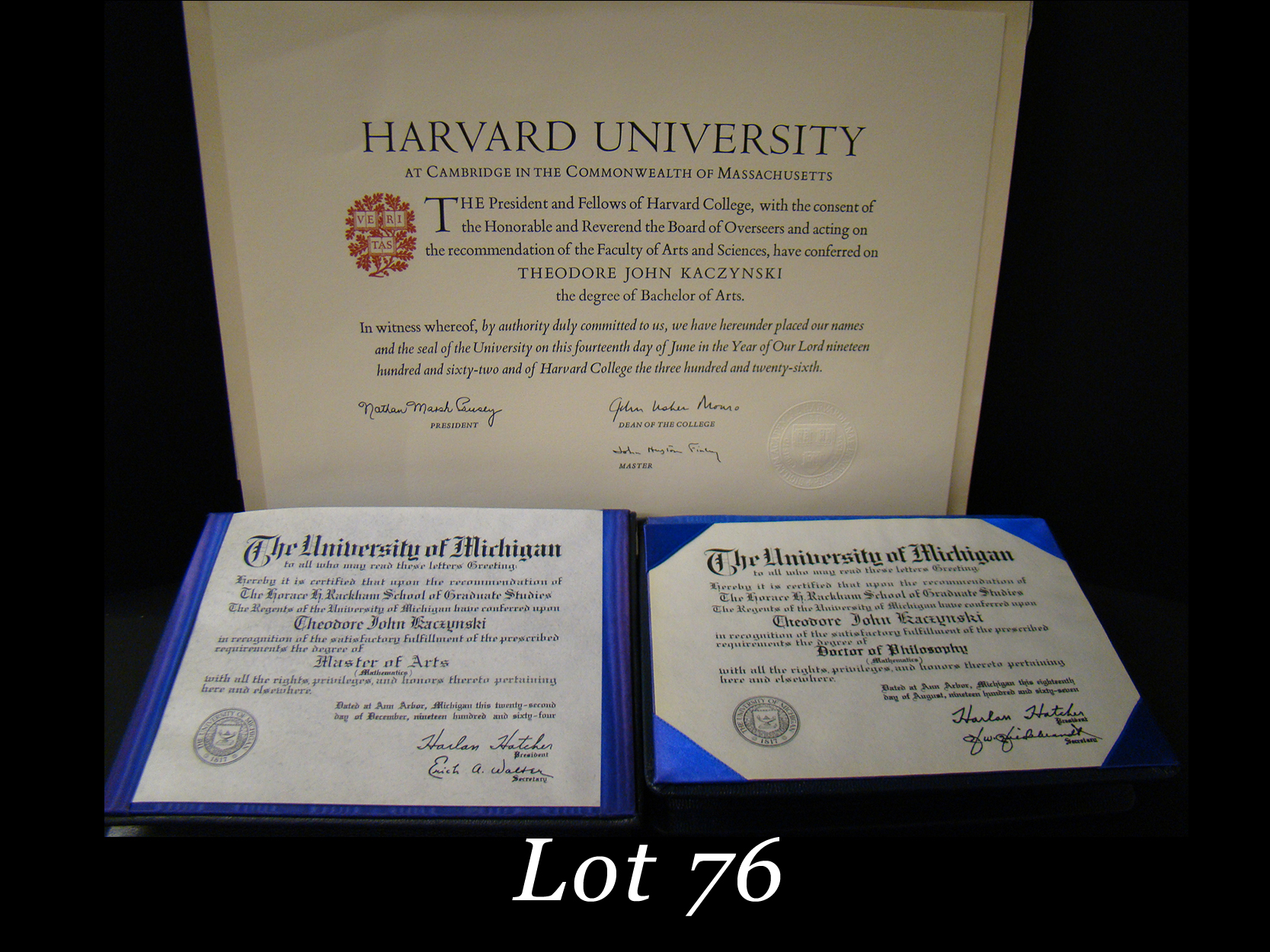

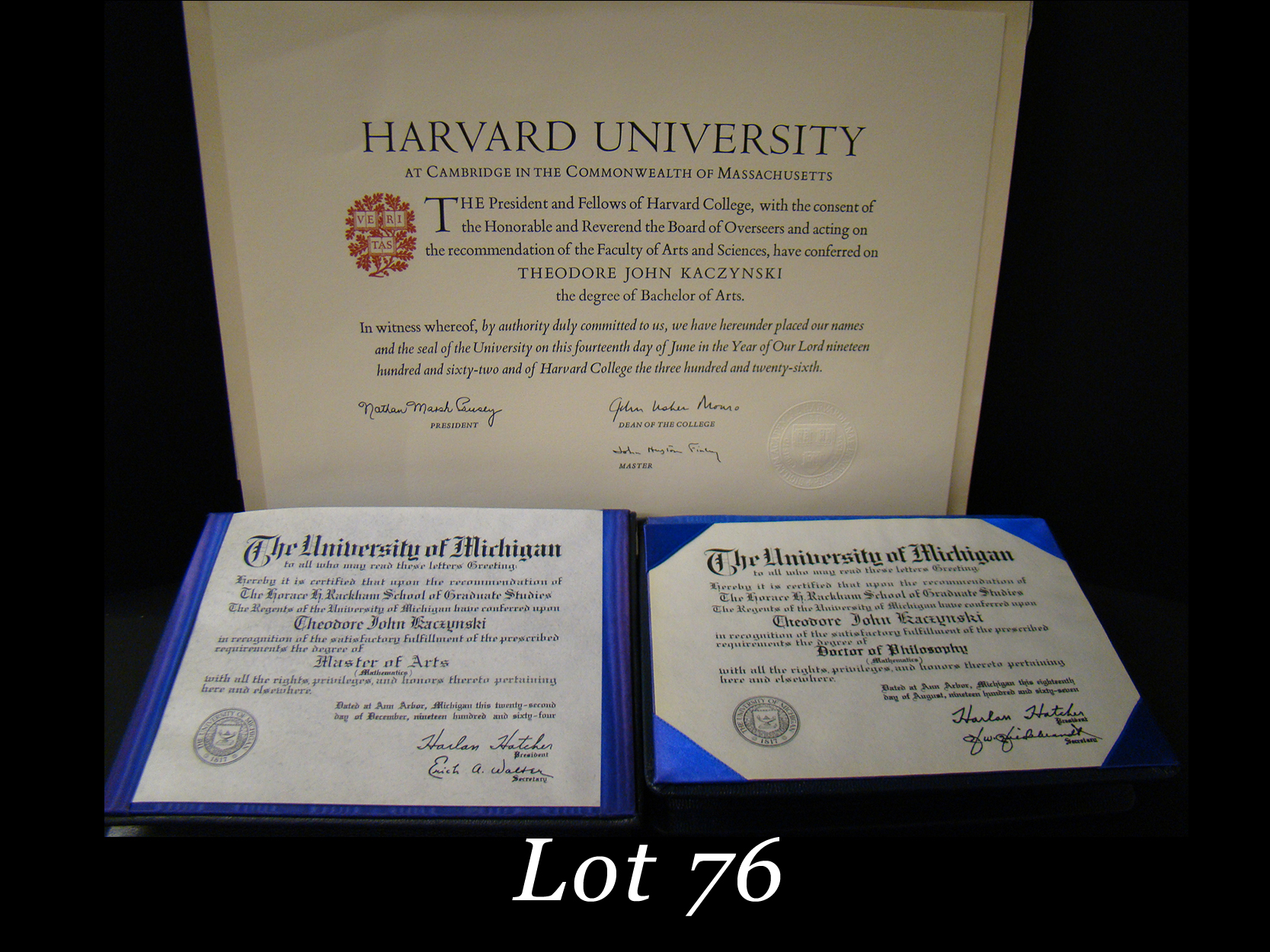

During his first year at Harvard, Kaczynski lived at 8 Prescott Street, which was designed to accommodate the youngest, most precocious incoming students in a small, intimate living space. For the following three years, he lived at

During his first year at Harvard, Kaczynski lived at 8 Prescott Street, which was designed to accommodate the youngest, most precocious incoming students in a small, intimate living space. For the following three years, he lived at

In 1962, Kaczynski enrolled at the

In 1962, Kaczynski enrolled at the

After resigning from Berkeley, Kaczynski moved to his parents' home in

After resigning from Berkeley, Kaczynski moved to his parents' home in

In 1981, a package bearing the return address of a

In 1981, a package bearing the return address of a

In 1995, Kaczynski mailed several letters to media outlets outlining his goals and demanding a major newspaper print his 35,000-word essay ''Industrial Society and Its Future'' (dubbed the "Unabomber manifesto" by the FBI) verbatim. He stated he would "desist from terrorism" if this demand was met. There was controversy as to whether the essay should be published, but Attorney General

In 1995, Kaczynski mailed several letters to media outlets outlining his goals and demanding a major newspaper print his 35,000-word essay ''Industrial Society and Its Future'' (dubbed the "Unabomber manifesto" by the FBI) verbatim. He stated he would "desist from terrorism" if this demand was met. There was controversy as to whether the essay should be published, but Attorney General

Because of the material used to make the mail bombs, U.S. postal inspectors, who initially had responsibility for the case, labeled the suspect the "Junkyard Bomber". FBI Inspector Terry D. Turchie was appointed to run the UNABOM (University and Airline Bomber) investigation. In 1979, an FBI-led task force that included 125 agents from the FBI, the

Because of the material used to make the mail bombs, U.S. postal inspectors, who initially had responsibility for the case, labeled the suspect the "Junkyard Bomber". FBI Inspector Terry D. Turchie was appointed to run the UNABOM (University and Airline Bomber) investigation. In 1979, an FBI-led task force that included 125 agents from the FBI, the

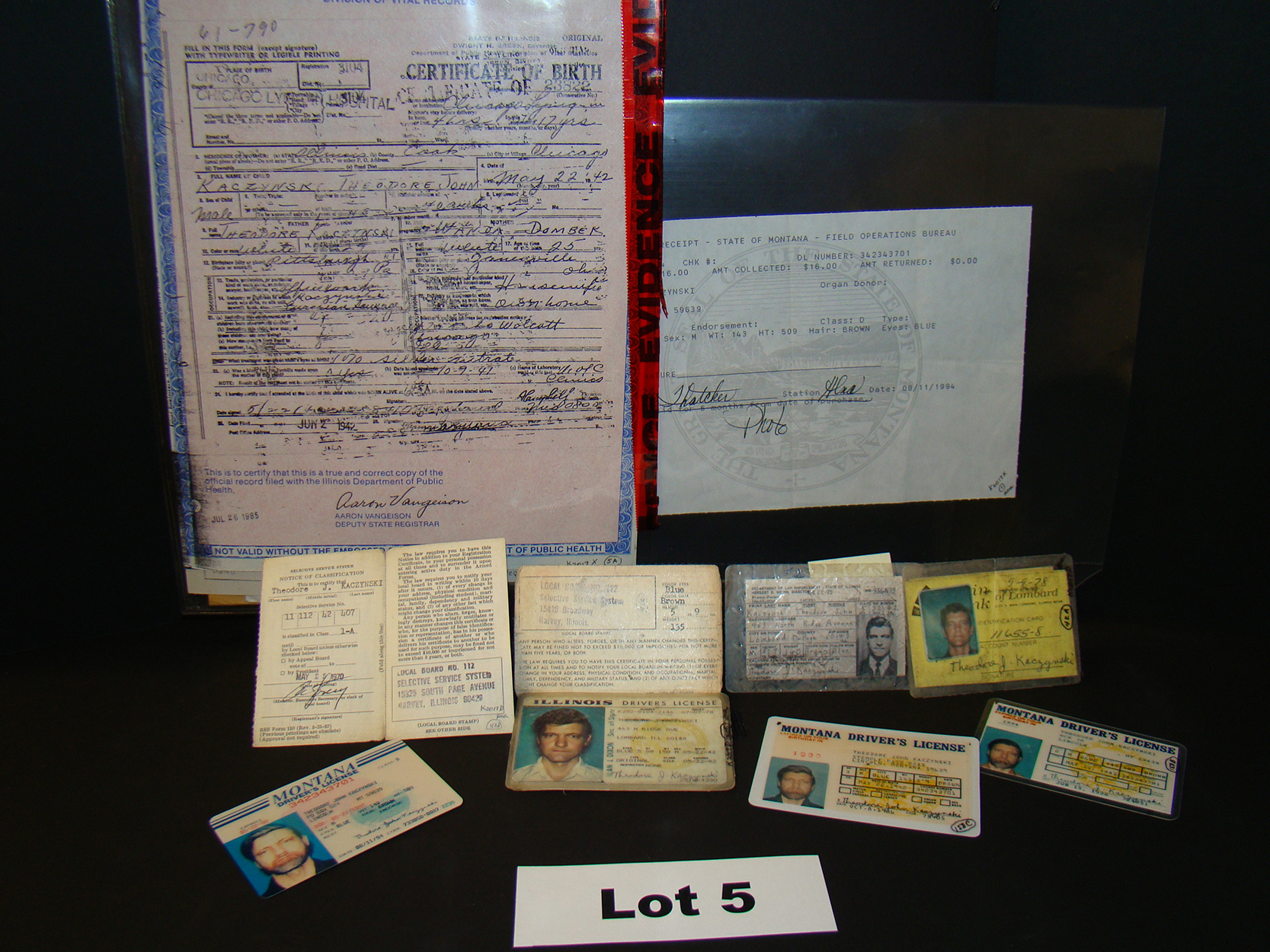

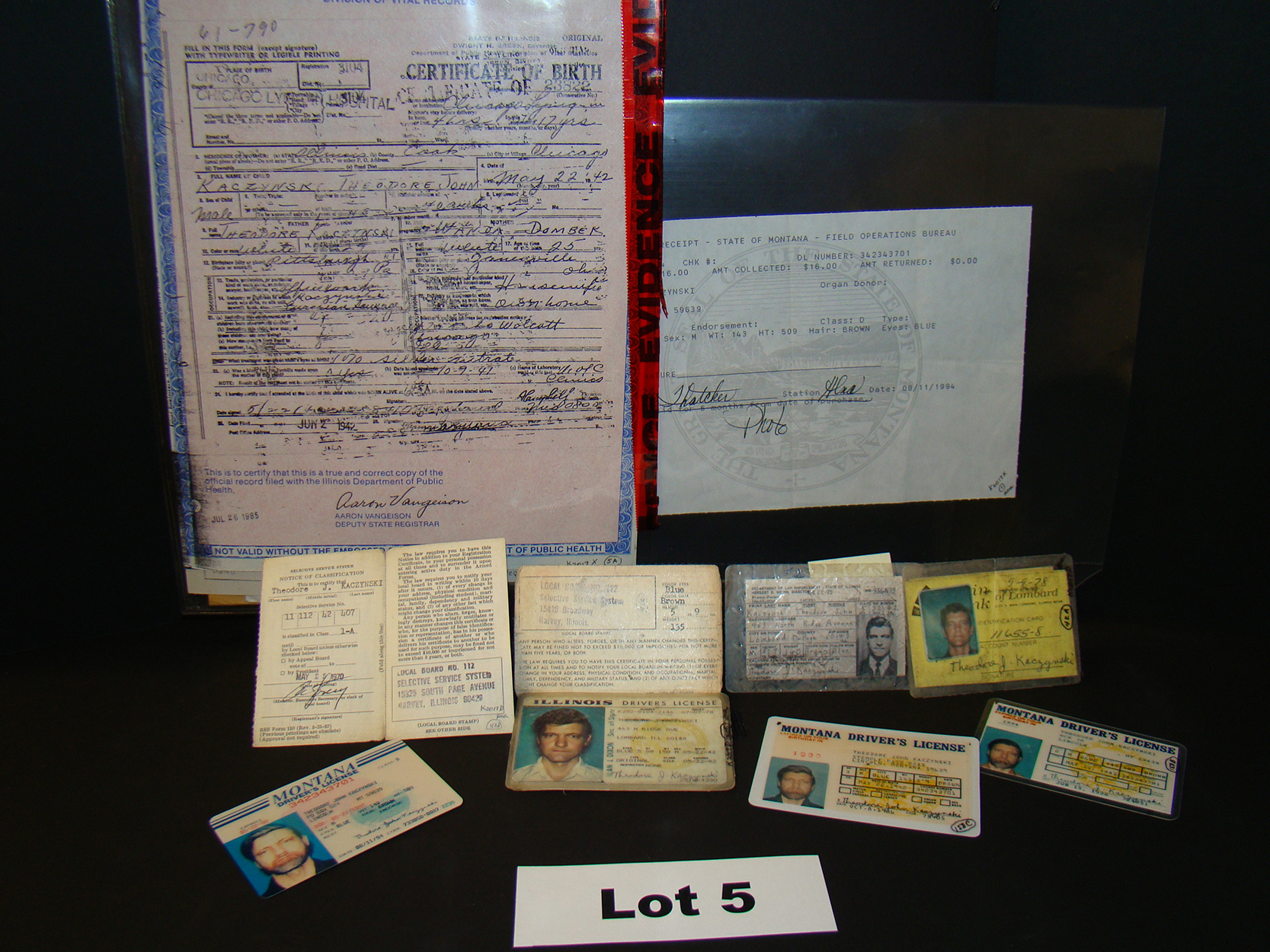

FBI agents arrested an unkempt Kaczynski at his cabin on April 3, 1996. A search revealed a cache of bomb components, 40,000 hand-written journal pages that included bomb-making experiments, descriptions of the Unabomber crimes and one live bomb. They also found what appeared to be the original typed manuscript of ''Industrial Society and Its Future''. By this point, the Unabomber had been the target of the most expensive investigation in FBI history at the time. A 2000 report by the United States Commission on the Advancement of Federal Law Enforcement stated that the task force had spent over $50 million throughout the course of the investigation.

After his capture, theories emerged naming Kaczynski as the

FBI agents arrested an unkempt Kaczynski at his cabin on April 3, 1996. A search revealed a cache of bomb components, 40,000 hand-written journal pages that included bomb-making experiments, descriptions of the Unabomber crimes and one live bomb. They also found what appeared to be the original typed manuscript of ''Industrial Society and Its Future''. By this point, the Unabomber had been the target of the most expensive investigation in FBI history at the time. A 2000 report by the United States Commission on the Advancement of Federal Law Enforcement stated that the task force had spent over $50 million throughout the course of the investigation.

After his capture, theories emerged naming Kaczynski as the

Kaczynski is serving eight life sentences without the possibility of parole at

Kaczynski is serving eight life sentences without the possibility of parole at

Ted Kaczynski

britannica.com

Kaczynski, Ted

encyclopedia.com

Unabomber (Profile)

The Canadian Encyclopedia

Unabomber — FBI

fbi.gov

Anarchist Library writings of Theodore Kaczynski

{{DEFAULTSORT:Kaczynski, Ted 1942 births 20th-century American criminals 20th-century American mathematicians Activists from Illinois American anarchists American environmentalists American hermits American male criminals American people convicted of murder American people imprisoned on charges of terrorism American people of Polish descent American prisoners sentenced to life imprisonment Bombers (people) Complex analysts Criminals from Chicago Fugitives Green anarchists Harvard College alumni Inmates of ADX Florence Insurrectionary anarchists Living people Mathematicians from Illinois Neo-Luddites People convicted of murder by the United States federal government People from Evergreen Park, Illinois People from Lewis and Clark County, Montana People with personality disorders 20th-century American philosophers Prisoners sentenced to life imprisonment by the United States federal government School bombings in the United States Simple living advocates Social critics University of California, Berkeley College of Letters and Science faculty University of Michigan College of Literature, Science, and the Arts alumni Violence and postal systems

domestic terrorist

Domestic terrorism or homegrown terrorism is a form of terrorism in which victims "within a country are targeted by a perpetrator with the same citizenship" as the victims.Gary M. Jackson, ''Predicting Malicious Behavior: Tools and Techniques ...

and former mathematics professor. Between 1978 and 1995, Kaczynski killed three people and injured 23 others in a nationwide mail bomb

A letter bomb, also called parcel bomb, mail bomb, package bomb, note bomb, message bomb, gift bomb, present bomb, delivery bomb, surprise bomb, postal bomb, or post bomb, is an explosive device sent via the mail, postal service, and designed ...

ing campaign against people he believed to be advancing modern technology and the destruction of the environment. He authored ''Industrial Society and Its Future

''Industrial Society and Its Future'', generally known as the ''Unabomber Manifesto'', is a 1995 anti-technology essay by Ted Kaczynski, the "Unabomber". The manifesto contends that the Industrial Revolution began a harmful process of natural ...

'', a 35,000-word manifesto

A manifesto is a published declaration of the intentions, motives, or views of the issuer, be it an individual, group, political party or government. A manifesto usually accepts a previously published opinion or public consensus or promotes a ...

and social critique opposing industrialization

Industrialisation ( alternatively spelled industrialization) is the period of social and economic change that transforms a human group from an agrarian society into an industrial society. This involves an extensive re-organisation of an econo ...

, rejecting leftism

Left-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy. Left-wing politics typically involve a concern for those in soci ...

, and advocating for a nature-centered form of anarchism

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not necessa ...

.

A mathematics prodigy

Prodigy, Prodigies or The Prodigy may refer to:

* Child prodigy, a child who produces meaningful output to the level of an adult expert performer

** Chess prodigy, a child who can beat experienced adult players at chess

Arts, entertainment, and ...

, Kaczynski attended Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

and the University of Michigan

, mottoeng = "Arts, Knowledge, Truth"

, former_names = Catholepistemiad, or University of Michigania (1817–1821)

, budget = $10.3 billion (2021)

, endowment = $17 billion (2021)As o ...

. In 1971, he abandoned his academic career to pursue a primitive life, moving to a remote cabin without electricity

Electricity is the set of physical phenomena associated with the presence and motion of matter that has a property of electric charge. Electricity is related to magnetism, both being part of the phenomenon of electromagnetism, as described ...

or running water

Tap water (also known as faucet water, running water, or municipal water) is water supplied through a tap, a water dispenser valve. In many countries, tap water usually has the quality of drinking water. Tap water is commonly used for drinking, ...

near Lincoln, Montana

Lincoln is an unincorporated community and census-designated place (CDP) in Lewis and Clark County, Montana, United States. As of the 2010 census, the population was 1,013.

History

Meriwether Lewis passed through the area on his return to St. ...

, where he lived as a recluse while learning survival skills

Survival skills are techniques that a person may use in order to sustain life in any type of natural environment or built environment. These techniques are meant to provide basic necessities for human life which include water, food, and shelte ...

to become self-sufficient. After witnessing the destruction of the wilderness

Wilderness or wildlands (usually in the plural), are natural environments on Earth that have not been significantly modified by human activity or any nonurbanized land not under extensive agricultural cultivation. The term has traditionally re ...

surrounding his cabin, he concluded that living in nature was becoming impossible and resolved to fight industrialization and its destruction of nature through terrorism. In 1979, Kaczynski became the subject of what was, by the time of his arrest, the longest and most expensive investigation in the history of the Federal Bureau of Investigation

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic intelligence and security service of the United States and its principal federal law enforcement agency. Operating under the jurisdiction of the United States Department of Justice, ...

(FBI). The FBI used the case identifier UNABOM (University and Airline Bomber) before his identity was known, resulting in the media naming him the "Unabomber".

In 1995, Kaczynski sent a letter to ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' promising to "desist from terrorism" if the ''Times'' or ''The Washington Post

''The Washington Post'' (also known as the ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'') is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C. It is the most widely circulated newspaper within the Washington metropolitan area and has a large nati ...

'' published his manifesto, in which he argued that his bombings were extreme but necessary in attracting attention to the erosion of human freedom and dignity by modern technologies that require mass organization

A mass movement denotes a political party or movement which is supported by large segments of a population. Political movements that typically advocate the creation of a mass movement include the ideologies of communism, fascism, and liberalism. Bo ...

. The FBI and Attorney General Janet Reno

Janet Wood Reno (July 21, 1938 – November 7, 2016) was an American lawyer who served as the 78th United States attorney general. She held the position from 1993 to 2001, making her the second-longest serving attorney general, behind only Wi ...

pushed for the publication of the essay, which appeared in ''The Washington Post'' in September 1995. Upon reading it, Kaczynski's brother, David

David (; , "beloved one") (traditional spelling), , ''Dāwūd''; grc-koi, Δαυΐδ, Dauíd; la, Davidus, David; gez , ዳዊት, ''Dawit''; xcl, Դաւիթ, ''Dawitʿ''; cu, Давíдъ, ''Davidŭ''; possibly meaning "beloved one". w ...

, recognized the prose style and reported his suspicions to the FBI. Kaczynski was arrested in 1996, and—maintaining that he was sane—tried and failed to dismiss his court-appointed lawyers because they wanted him to plead insanity to avoid the death penalty

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that t ...

. He pleaded guilty to all charges in 1998 and was sentenced to eight consecutive life terms in prison without the possibility of parole.

Early life

Childhood

Theodore John Kaczynski was born in

Theodore John Kaczynski was born in Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

on May 22, 1942, to working-class parents Wanda Theresa (''née

A birth name is the name of a person given upon birth. The term may be applied to the surname, the given name, or the entire name. Where births are required to be officially registered, the entire name entered onto a birth certificate or birth re ...

'' Dombek) and Theodore Richard Kaczynski, a sausage maker. The two were Polish Americans

Polish Americans ( pl, Polonia amerykańska) are Americans who either have total or partial Poles, Polish ancestry, or are citizens of the Republic of Poland. There are an estimated 9.15 million self-identified Polish Americans, representing abou ...

who were raised as Catholics but later became atheists. They married on April 11, 1939.

From first to fourth grade (ages six to nine), Kaczynski attended Sherman Elementary School in Chicago, where administrators described him as healthy and well-adjusted. In 1952, three years after David was born, the family moved to suburban Evergreen Park, Illinois; Ted transferred to Evergreen Park Central Junior High School. After testing scored his IQ at 167, he skipped the sixth grade. Kaczynski later described this as a pivotal event: previously he had socialized with his peers and was even a leader, but after skipping ahead of them he felt he did not fit in with the older children, who bullied him.

Neighbors in Evergreen Park later described the Kaczynski family as "civic-minded folks", one recalling the parents "sacrificed everything they had for their children". Both Ted and David were intelligent, but Ted exceptionally so. Neighbors described him as a smart but lonely individual.

High school

Kaczynski attended Evergreen Park Community High School, where he excelled academically. He played the

Kaczynski attended Evergreen Park Community High School, where he excelled academically. He played the trombone

The trombone (german: Posaune, Italian, French: ''trombone'') is a musical instrument in the Brass instrument, brass family. As with all brass instruments, sound is produced when the player's vibrating lips cause the Standing wave, air column ...

in the marching band

A marching band is a group of instrumental musicians who perform while marching, often for entertainment or competition. Instrumentation typically includes brass, woodwind, and percussion instruments. Most marching bands wear a uniform, ofte ...

and was a member of the mathematics, biology, coin, and German clubs. In 1996, a former classmate said: "He was never really seen as a person, as an individual personality... He was always regarded as a walking brain, so to speak." During this period, Kaczynski became intensely interested in mathematics, spending hours studying and solving advanced problems. He became associated with a group of like-minded boys interested in science and mathematics, known as the "briefcase boys" for their penchant for carrying briefcases.

Throughout high school, Kaczynski was ahead of his classmates academically. Placed in a more advanced mathematics class, he soon mastered the material. He skipped the eleventh grade, and by attending summer school he graduated at age 15. Kaczynski was one of his school's five National Merit finalists

The National Merit Scholarship Program is a United States academic scholarship competition for recognition and university scholarships administered by the National Merit Scholarship Corporation (NMSC), a privately funded, not-for-profit organizati ...

and was encouraged to apply to Harvard

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

. While still at age 15, he was accepted to Harvard and entered the university on a scholarship

A scholarship is a form of financial aid awarded to students for further education. Generally, scholarships are awarded based on a set of criteria such as academic merit, diversity and inclusion, athletic skill, and financial need.

Scholarsh ...

in 1958 at age 16. A classmate later said Kaczynski was emotionally unprepared: "They packed him up and sent him to Harvard before he was ready... He didn't even have a driver's license."

Harvard University

During his first year at Harvard, Kaczynski lived at 8 Prescott Street, which was designed to accommodate the youngest, most precocious incoming students in a small, intimate living space. For the following three years, he lived at

During his first year at Harvard, Kaczynski lived at 8 Prescott Street, which was designed to accommodate the youngest, most precocious incoming students in a small, intimate living space. For the following three years, he lived at Eliot House

Eliot House is one of twelve undergraduate residential Houses at Harvard University. It is one of the seven original houses at the college. Opened in 1931, the house was named after Charles William Eliot, who served as president of the universit ...

. Housemates and other students at Harvard described Kaczynski as a very intelligent but socially reserved person. Kaczynski earned his Bachelor of Arts

Bachelor of arts (BA or AB; from the Latin ', ', or ') is a bachelor's degree awarded for an undergraduate program in the arts, or, in some cases, other disciplines. A Bachelor of Arts degree course is generally completed in three or four years ...

degree in mathematics from Harvard in 1962, finishing with a GPA

Grading in education is the process of applying standardized measurements for varying levels of achievements in a course. Grades can be assigned as letters (usually A through F), as a range (for example, 1 to 6), as a percentage, or as a numbe ...

of 3.12.

Psychological study

In his second year at Harvard, Kaczynski participated in a study described by author Alston Chase as a "purposely brutalizing psychological experiment" led by Harvard psychologistHenry Murray

Henry Alexander Murray (May 13, 1893 – June 23, 1988) was an American psychologist at Harvard University, where from 1959 to 1962 he conducted a series of psychologically damaging and purposefully abusive experiments on minors and underg ...

. Subjects were told they would debate personal philosophy with a fellow student and were asked to write essays detailing their personal beliefs and aspirations. The essays were given to an anonymous individual who would confront and belittle the subject in what Murray himself called "vehement, sweeping, and personally abusive" attacks, using the content of the essays as ammunition. Electrodes

An electrode is an electrical conductor used to make contact with a nonmetallic part of a circuit (e.g. a semiconductor, an electrolyte, a vacuum or air). Electrodes are essential parts of batteries that can consist of a variety of materials de ...

monitored the subject's physiological reactions. These encounters were filmed, and subjects' expressions of anger and rage were later played back to them repeatedly. The experiment lasted three years, with someone verbally abusing and humiliating Kaczynski each week. Kaczynski spent 200 hours as part of the study.

Kaczynski's lawyers later attributed his hostility towards mind control

Brainwashing (also known as mind control, menticide, coercive persuasion, thought control, thought reform, and forced re-education) is the concept that the human mind can be altered or controlled by certain psychological techniques. Brainwashin ...

techniques to his participation in Murray's study. Some sources have suggested that Murray's experiments were part of Project MKUltra

Project MKUltra (or MK-Ultra) was an illegal human experimentation program designed and undertaken by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), intended to develop procedures and identify drugs that could be used in interrogations to weak ...

, the Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, ...

's research into mind control.Moreno (2012). Chase and others have also suggested that this experience may have motivated Kaczynski's criminal activities.Chase (2003), pp. 18–19. Kaczynski stated he resented Murray and his co-workers, primarily because of the invasion of his privacy he perceived as a result of their experiments. Nevertheless, he said he was "quite confident that isexperiences with Professor Murray had no significant effect on the course of islife".

Mathematics career

In 1962, Kaczynski enrolled at the

In 1962, Kaczynski enrolled at the University of Michigan

, mottoeng = "Arts, Knowledge, Truth"

, former_names = Catholepistemiad, or University of Michigania (1817–1821)

, budget = $10.3 billion (2021)

, endowment = $17 billion (2021)As o ...

, where he earned his master's

A master's degree (from Latin ) is an academic degree awarded by universities or colleges upon completion of a course of study demonstrating mastery or a high-order overview of a specific field of study or area of professional practice.

and doctoral

A doctorate (from Latin ''docere'', "to teach"), doctor's degree (from Latin ''doctor'', "teacher"), or doctoral degree is an academic degree awarded by universities and some other educational institutions, derived from the ancient formalism ''li ...

degrees in mathematics in 1964 and 1967, respectively. Michigan was not his first choice for postgraduate education

Postgraduate or graduate education refers to Academic degree, academic or professional degrees, certificates, diplomas, or other qualifications pursued by higher education, post-secondary students who have earned an Undergraduate education, un ...

; he had applied to the University of California, Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California) is a public land-grant research university in Berkeley, California. Established in 1868 as the University of California, it is the state's first land-grant u ...

, and the University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, U of C, or UChi) is a private research university in Chicago, Illinois. Its main campus is located in Chicago's Hyde Park neighborhood. The University of Chicago is consistently ranked among the b ...

, both of which accepted him but offered him no teaching position or financial aid. Michigan offered him an annual grant of $2,310 () and a teaching post.

At Michigan, Kaczynski specialized in complex analysis

Complex analysis, traditionally known as the theory of functions of a complex variable, is the branch of mathematical analysis that investigates Function (mathematics), functions of complex numbers. It is helpful in many branches of mathemati ...

, specifically geometric function theory

Geometric function theory is the study of geometric properties of analytic functions. A fundamental result in the theory is the Riemann mapping theorem.

Topics in geometric function theory

The following are some of the most important topics in ge ...

. Professor Peter Duren

Peter Larkin Duren (30 April 1935, New Orleans, Louisiana – July 10, 2020) was an American mathematician. He specialized in mathematical analysis and was known for the monographs and textbooks he has written.

Academic Career

Duren receiv ...

said of Kaczynski, "He was an unusual person. He was not like the other graduate students. He was much more focused about his work. He had a drive to discover mathematical truth." George Piranian

George Piranian ( hy, Գևորգ Փիրանեան; May 2, 1914 – August 31, 2009) was a Swiss-American mathematician. Piranian was internationally known for his research in complex analysis, his association with Paul Erdős, and his editing of ...

, another of his Michigan mathematics professors, said, "It is not enough to say he was smart." Professor Allen Shields

Allen Lowell Shields (May 7, 1927 – September 16, 1989) was an American mathematician who worked on measure theory, complex analysis, functional analysis and operator theory,

and was "one of the world's leading authorities on spaces of analytic ...

wrote about Kaczynski in a grade evaluation that he was the "best man I have seen." Kaczynski received 1 F, 5 Bs and 12 As in his 18 courses at the university. In 2006, he said he had unpleasant memories of Michigan and felt the university had low standards for grading, as evidenced by his relatively high grades.

For a period of several weeks in 1966, Kaczynski experienced intense sexual fantasies of being a female and decided to undergo gender transition

Gender transition is the process of changing one's gender presentation or sex characteristics to accord with one's internal sense of gender identity – the idea of what it means to be a man or a woman,Brown, M. L. & Rounsley, C. A. (1996) ''True ...

. He arranged to meet with a psychiatrist, but changed his mind in the waiting room and did not disclose his reason for making the appointment. Afterwards, enraged, he considered killing the psychiatrist and other people whom he hated. Kaczynski described this episode as a "major turning point" in his life: "I felt disgusted about what my uncontrolled sexual cravings had almost led me to do. And I felt humiliated, and I violently hated the psychiatrist. Just then there came a major turning point in my life. Like a Phoenix, I burst from the ashes of my despair to a glorious new hope."

In 1967, Kaczynski's dissertation ''Boundary Functions'' won the Sumner B. Myers

Sumner Byron Myers (February 19, 1910 – October 8, 1955) was an American mathematician specializing in topology and differential geometry. He studied at Harvard University under H. C. Marston Morse, Tucker, A: Interview with Albert Tucker'', Pr ...

Prize for Michigan's best mathematics dissertation of the year. Allen Shields

Allen Lowell Shields (May 7, 1927 – September 16, 1989) was an American mathematician who worked on measure theory, complex analysis, functional analysis and operator theory,

and was "one of the world's leading authorities on spaces of analytic ...

, his doctoral advisor

A doctoral advisor (also dissertation director, dissertation advisor; or doctoral supervisor) is a member of a university faculty whose role is to guide graduate students who are candidates for a doctorate, helping them select coursework, as well ...

, called it "the best I have ever directed", and Maxwell Reade, a member of his dissertation committee

A thesis (plural, : theses), or dissertation (abbreviated diss.), is a document submitted in support of candidature for an academic degree or professional qualification presenting the author's research and findings.International Standard Int ...

, said, "I would guess that maybe 10 or 12 men in the country understood or appreciated it."

In late 1967, the 25-year-old Kaczynski became an acting assistant professor at the University of California, Berkeley, where he taught mathematics. By September 1968, Kaczynski was appointed assistant professor

Assistant Professor is an academic rank just below the rank of an associate professor used in universities or colleges, mainly in the United States and Canada.

Overview

This position is generally taken after earning a doctoral degree and general ...

, a sign that he was on track for tenure

Tenure is a category of academic appointment existing in some countries. A tenured post is an indefinite academic appointment that can be terminated only for cause or under extraordinary circumstances, such as financial exigency or program disco ...

. His teaching evaluations suggest he was not well-liked by his students: he seemed uncomfortable teaching, taught straight from the textbook and refused to answer questions. Without any explanation, Kaczynski resigned on June 30, 1969. In a 1970 letter directed to Kaczynski's thesis advisor

A doctoral advisor (also dissertation director, dissertation advisor; or doctoral supervisor) is a member of a university faculty whose role is to guide graduate students who are candidates for a doctorate, helping them select coursework, as well ...

Allen Shields

Allen Lowell Shields (May 7, 1927 – September 16, 1989) was an American mathematician who worked on measure theory, complex analysis, functional analysis and operator theory,

and was "one of the world's leading authorities on spaces of analytic ...

, written by the chairman of the mathematics department, John W. Addison Jr, the professor referred to the resignation as "quite out of the blue" and, markedly, added that "Kaczynski seemed almost pathologically shy" and that as far as he knew Kaczynski made no close friends in the department, furthermore noting that efforts to bring him more into the 'swing of things' had failed.

Life in Montana

After resigning from Berkeley, Kaczynski moved to his parents' home in

After resigning from Berkeley, Kaczynski moved to his parents' home in Lombard, Illinois

Lombard is a village in DuPage County, Illinois, United States, and a suburb of Chicago. The population was 43,165 at the 2010 census. The United States Census Bureau estimated the population in 2019 to be 44,303.

History

Originally part of ...

. Two years later, in 1971, he moved to a remote cabin he had built outside Lincoln, Montana

Lincoln is an unincorporated community and census-designated place (CDP) in Lewis and Clark County, Montana, United States. As of the 2010 census, the population was 1,013.

History

Meriwether Lewis passed through the area on his return to St. ...

, where he could live a simple life

Simple living refers to practices that promote simplicity in one's lifestyle. Common practices of simple living include reducing the number of possessions one owns, depending less on technology and services, and spending less money. Not only is ...

with little money and without electricity or running water, working odd jobs and receiving significant financial support from his family.

Kaczynski's original goal was to become self-sufficient so he could live autonomously. He used an old bicycle to get to town, and a volunteer at the local library said he visited frequently to read classic works in their original languages. Other Lincoln residents said later that such a lifestyle was not unusual in the area. Kaczynski's cabin was described by a census taker in the 1990 census as containing a bed, two chairs, storage trunk

Trunk may refer to:

Biology

* Trunk (anatomy), synonym for torso

* Trunk (botany), a tree's central superstructure

* Trunk of corpus callosum, in neuroanatomy

* Elephant trunk, the proboscis of an elephant

Computing

* Trunk (software), in rev ...

s, a gas stove, and lots of books.

Starting in 1975, Kaczynski performed acts of sabotage including arson

Arson is the crime of willfully and deliberately setting fire to or charring property. Although the act of arson typically involves buildings, the term can also refer to the intentional burning of other things, such as motor vehicles, wat ...

and booby trap

A booby trap is a device or setup that is intended to kill, harm or surprise a human or another animal. It is triggered by the presence or actions of the victim and sometimes has some form of bait designed to lure the victim towards it. The trap m ...

ping against developments near to his cabin. He also dedicated himself to reading about sociology

Sociology is a social science that focuses on society, human social behavior, patterns of Interpersonal ties, social relationships, social interaction, and aspects of culture associated with everyday life. It uses various methods of Empirical ...

and political philosophy

Political philosophy or political theory is the philosophical study of government, addressing questions about the nature, scope, and legitimacy of public agents and institutions and the relationships between them. Its topics include politics, l ...

, including the works of Jacques Ellul

Jacques Ellul (; ; January 6, 1912 – May 19, 1994) was a French philosopher, sociologist, lay theologian, and professor who was a noted Christian anarchist. Ellul was a longtime Professor of History and the Sociology of Institutions on t ...

. Kaczynski's brother David later stated that Ellul's book ''The Technological Society

''The Technological Society'' is a book on the subject of ''technique'' by French philosopher, theologian and sociologist Jacques Ellul. Originally published in French in 1954, it was translated into English in 1964.

On technique

The central c ...

'' "became Ted's Bible". Kaczynski recounted in 1998, "When I read the book for the first time, I was delighted, because I thought, 'Here is someone who is saying what I have already been thinking.'"

In an interview after his arrest, Kaczynski recalled being shocked on a hike to one of his favorite wild spots:

Kaczynski was visited multiple times in Montana by his father, who was impressed by Ted's wilderness skills. Kaczynski's father was diagnosed with terminal

Terminal may refer to:

Computing Hardware

* Terminal (electronics), a device for joining electrical circuits together

* Terminal (telecommunication), a device communicating over a line

* Computer terminal, a set of primary input and output devic ...

lung cancer

Lung cancer, also known as lung carcinoma (since about 98–99% of all lung cancers are carcinomas), is a malignant lung tumor characterized by uncontrolled cell growth in tissue (biology), tissues of the lung. Lung carcinomas derive from tran ...

in 1990 and held a family meeting without Kaczynski later that year to map out their future. On October 2, 1990, Kaczynski's father committed suicide

Suicide is the act of intentionally causing one's own death. Mental disorders (including depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, personality disorders, anxiety disorders), physical disorders (such as chronic fatigue syndrome), and s ...

by shooting himself in his home.

Bombings

Between 1978 and 1995, Kaczynski mailed or hand-delivered a series of increasingly sophisticated bombs that cumulatively killed three people and injured 23 others. Sixteen bombs were attributed to Kaczynski. While the bombing devices varied widely through the years, many contained the initials "FC", which Kaczynski later said stood for "Freedom Club", inscribed on parts inside. He purposely left misleading clues in the devices and took extreme care in preparing them to avoid leavingfingerprints

A fingerprint is an impression left by the friction ridges of a human finger. The recovery of partial fingerprints from a crime scene is an important method of forensic science. Moisture and grease on a finger result in fingerprints on surf ...

; fingerprints found on some of the devices did not match those found on letters attributed to Kaczynski.

{, class="wikitable sortable plainrowheaders"

, + Bombings carried out by Kaczynski

, -

! scope="col" style="width:17.5%;" , Date

! scope="col" , State

! scope="col" style="width:40%;" , Location

! scope="col" style="width:10%;" , Explosion

! scope="col" , Victim(s)

! scope="col" , Occupation of victim(s)

! scope="col" style="width:60%;" , Injuries

, -

! scope="row" data-sort-value=1978-05-25 , May 25, 1978

, rowspan="4" , Illinois

, rowspan="2" , Northwestern University

Northwestern University is a private research university in Evanston, Illinois. Founded in 1851, Northwestern is the oldest chartered university in Illinois and is ranked among the most prestigious academic institutions in the world.

Charte ...

,

, Terry Marker

, University police officer

, Minor cuts and burns

, -

! scope="row" data-sort-value=1979-05-09 , May 9, 1979

,

, John Harris

, Graduate student

, Minor cuts and burns

, -

! scope="row" data-sort-value=1979-11-15 , November 15, 1979

, American Airlines Flight 444

American Airlines Flight 444 was a scheduled American Airlines flight from Chicago to Washington, D.C.'s National Airport. On November 15, 1979, the Boeing 727 serving the flight was attacked by "the Unabomber", Ted Kaczynski, who sent the bomb i ...

from Chicago to Washington, D.C. (explosion occurred midflight)

,

, Twelve passengers

, Multiple

, Non-lethal smoke inhalation

Smoke inhalation is the breathing in of harmful fumes (produced as by-products of combusting substances) through the respiratory tract. This can cause smoke inhalation injury (subtype of acute inhalation injury) which is damage to the respirator ...

, -

! scope="row" data-sort-value=1980-06-10 , June 10, 1980

, Lake Forest

,

, Percy Wood

Percy Addison Wood Jr. (June 7, 1920 – June 23, 2008) was a United Airlines executive who was notably injured by a bomb sent from Ted Kaczynski. Wood had never met Kaczynski, but Kaczynski was believed to be fascinated with Wood, sometimes encas ...

, style="white-space:nowrap;" , President of United Airlines

United Airlines, Inc. (commonly referred to as United), is a major American airline headquartered at the Willis Tower in Chicago, Illinois.

, Severe cuts and burns over most of body and face

, -

! scope="row" data-sort-value=1981-10-08 , October 8, 1981

, Utah

, University of Utah

The University of Utah (U of U, UofU, or simply The U) is a public research university in Salt Lake City, Utah. It is the flagship institution of the Utah System of Higher Education. The university was established in 1850 as the University of De ...

,

,

,

,

, -

! scope="row" data-sort-value=1982-05-05 , May 5, 1982

, Tennessee

, Vanderbilt University

Vanderbilt University (informally Vandy or VU) is a private research university in Nashville, Tennessee. Founded in 1873, it was named in honor of shipping and rail magnate Cornelius Vanderbilt, who provided the school its initial $1-million ...

,

, Janet Smith

, University secretary

, Severe burns to hands; shrapnel

Shrapnel may refer to:

Military

* Shrapnel shell, explosive artillery munitions, generally for anti-personnel use

* Shrapnel (fragment), a hard loose material

Popular culture

* ''Shrapnel'' (Radical Comics)

* ''Shrapnel'', a game by Adam C ...

wounds to body

, -

! scope="row" data-sort-value=1982-07-02 , July 2, 1982

, rowspan="2" , California

, rowspan="2" , University of California, Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California) is a public land-grant research university in Berkeley, California. Established in 1868 as the University of California, it is the state's first land-grant u ...

,

, Diogenes Angelakos

Diogenes James Angelakos (July 3, 1919 – June 7, 1997) was an American electrical engineer and professor emeritus of electronic engineering at the University of California, Berkeley, who served as the director of the Electronics Research Labora ...

, Engineering professor

, Severe burns and shrapnel wounds to hand and face

, -

! scope="row" data-sort-value=1985-05-15 , May 15, 1985

,

, John Hauser

, Graduate student

, Loss of four fingers and severed artery in right arm; partial loss of vision in left eye

, -

! scope="row" data-sort-value=1985-06-13, June 13, 1985

, Washington

, The Boeing Company

The Boeing Company () is an American multinational corporation that designs, manufactures, and sells airplanes, rotorcraft, rockets, satellites, telecommunications equipment, and missiles worldwide. The company also provides leasing and product ...

in Auburn

Auburn may refer to:

Places Australia

* Auburn, New South Wales

* City of Auburn, the local government area

*Electoral district of Auburn

*Auburn, Queensland, a locality in the Western Downs Region

*Auburn, South Australia

*Auburn, Tasmania

*Aub ...

,

,

,

,

, -

! scope="row" data-sort-value="1985-11-15" rowspan="2" , November 15, 1985

, rowspan="2" , Michigan

, rowspan="2" , University of Michigan

, mottoeng = "Arts, Knowledge, Truth"

, former_names = Catholepistemiad, or University of Michigania (1817–1821)

, budget = $10.3 billion (2021)

, endowment = $17 billion (2021)As o ...

,

, James V. McConnell

James V. McConnell (October 26, 1925 – April 9, 1990) was an American biologist and animal psychologist. He is most known for his research on learning and memory transfer in planarians conducted in the 1950s and 1960s. McConnell also publish ...

, Psychology professor

, Temporary hearing loss

, -

,

, Nicklaus Suino

, Research assistant

, Burns and shrapnel wounds

, -

! scope="row" data-sort-value=1985-12-11 , December 11, 1985

, California

, Sacramento

)

, image_map = Sacramento County California Incorporated and Unincorporated areas Sacramento Highlighted.svg

, mapsize = 250x200px

, map_caption = Location within Sacramento ...

,

, Hugh Scrutton

, Computer store owner

, Death

, -

! scope="row" data-sort-value=1987-02-20 , February 20, 1987

, Utah

, Salt Lake City

Salt Lake City (often shortened to Salt Lake and abbreviated as SLC) is the Capital (political), capital and List of cities and towns in Utah, most populous city of Utah, United States. It is the county seat, seat of Salt Lake County, Utah, Sal ...

,

, Gary Wright

, Computer store owner

, Severe nerve damage to left arm

, -

! scope="row" data-sort-value=1993-06-22 , June 22, 1993

, California

, Tiburon

,

, Charles Epstein

, Geneticist

, Severe damage to both eardrums with partial hearing loss, loss of three fingers

, -

! scope="row" data-sort-value=1993-06-24 , June 24, 1993

, Connecticut

, Yale University

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the wo ...

,

, David Gelernter

David Hillel Gelernter (born March 5, 1955) is an American computer scientist, artist, and writer. He is a professor of computer science at Yale University.

Gelernter is known for contributions to parallel computation in the 1980s, and for books ...

, style="white-space:nowrap;" , Computer science professor

, Severe burns and shrapnel wounds, damage to right eye, loss of right hand

, -

! scope="row" data-sort-value=1994-12-10 , December 10, 1994

, New Jersey

, North Caldwell

North Caldwell is a borough in northwestern Essex County, New Jersey, United States, and a suburb of New York City. As of the 2020 United States census, the borough's population was 6,694, an increase of 511 (+8.3%) from the 2010 census count ...

,

, Thomas J. Mosser

, Advertising executive at Burson-Marsteller

Burson Cohn & Wolfe is a multinational public relations and communications firm, headquartered in New York City. In February 2018, parent WPP Group PLC announced that it had merged its subsidiaries Cohn & Wolfe with Burson-Marsteller. The comb ...

, Death

, -

! scope="row" data-sort-value=1995-04-24 , April 24, 1995

, California

, Sacramento

)

, image_map = Sacramento County California Incorporated and Unincorporated areas Sacramento Highlighted.svg

, mapsize = 250x200px

, map_caption = Location within Sacramento ...

,

, style="white-space:nowrap;" , Gilbert Brent Murray

, Timber industry lobbyist

, Death

Initial bombings

Kaczynski's firstmail bomb

A letter bomb, also called parcel bomb, mail bomb, package bomb, note bomb, message bomb, gift bomb, present bomb, delivery bomb, surprise bomb, postal bomb, or post bomb, is an explosive device sent via the mail, postal service, and designed ...

was directed at Buckley Crist, a professor of materials engineering at Northwestern University

Northwestern University is a private research university in Evanston, Illinois. Founded in 1851, Northwestern is the oldest chartered university in Illinois and is ranked among the most prestigious academic institutions in the world.

Charte ...

. On May 25, 1978, a package bearing Crist's return address was found in a parking lot at the University of Illinois at Chicago

The University of Illinois Chicago (UIC) is a Public university, public research university in Chicago, Illinois. Its campus is in the Near West Side, Chicago, Near West Side community area, adjacent to the Chicago Loop. The second campus esta ...

. The package was "returned" to Crist, who was suspicious because he had not sent it, so he contacted campus police. Officer Terry Marker opened the package, which exploded and caused minor injuries. Kaczynski had returned to Chicago for the May 1978 bombing and stayed there for a time to work with his father and brother at a foam rubber

Foam rubber (also known as cellular rubber, sponge rubber, or expanded rubber) refers to rubber that has been manufactured with a foaming agent to create an air-filled matrix structure. Commercial foam rubbers are generally made of synthetic rubb ...

factory. In August 1978, his brother fired him for writing insulting limericks

A limerick ( ) is a form of verse, usually humorous and frequently rude, in five-line, predominantly trimeter with a strict rhyme scheme of AABBA, in which the first, second and fifth line rhyme, while the third and fourth lines are shorter and ...

about a female supervisor Ted had courted briefly. The supervisor later recalled Kaczynski as intelligent and quiet, but remembered little of their acquaintanceship and firmly denied they had had any romantic relationship. Kaczynski's second bomb was sent nearly one year after the first one, again to Northwestern University. The bomb, concealed inside a cigar

A cigar is a rolled bundle of dried and fermented tobacco leaves made to be smoked. Cigars are produced in a variety of sizes and shapes. Since the 20th century, almost all cigars are made of three distinct components: the filler, the binder l ...

box and left on a table, caused minor injuries to graduate student John Harris when he opened it.

FBI involvement

In 1979, a bomb was placed in thecargo hold

120px, View of the hold of a container ship

A ship's hold or cargo hold is a space for carrying cargo in the ship's compartment.

Description

Cargo in holds may be either packaged in crates, bales, etc., or unpackaged (bulk cargo). Access to ho ...

of American Airlines Flight 444

American Airlines Flight 444 was a scheduled American Airlines flight from Chicago to Washington, D.C.'s National Airport. On November 15, 1979, the Boeing 727 serving the flight was attacked by "the Unabomber", Ted Kaczynski, who sent the bomb i ...

, a Boeing 727

The Boeing 727 is an American narrow-body airliner that was developed and produced by Boeing Commercial Airplanes.

After the heavy 707 quad-jet was introduced in 1958, Boeing addressed the demand for shorter flight lengths from smaller airpo ...

flying from Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

to Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

A faulty timing mechanism prevented the bomb from exploding, but it released smoke, which caused the pilots to carry out an emergency landing

An emergency landing is a premature landing made by an aircraft in response to an emergency involving an imminent or ongoing threat to the safety and operation of the aircraft, or involving a sudden need for a passenger or crew on board to term ...

. Authorities said it had enough power to "obliterate the plane" had it exploded. Kaczynski sent his next bomb to the president of United Airlines

United Airlines, Inc. (commonly referred to as United), is a major American airline headquartered at the Willis Tower in Chicago, Illinois.

, Percy Wood

Percy Addison Wood Jr. (June 7, 1920 – June 23, 2008) was a United Airlines executive who was notably injured by a bomb sent from Ted Kaczynski. Wood had never met Kaczynski, but Kaczynski was believed to be fascinated with Wood, sometimes encas ...

. Wood received cuts and burns over most of his body.

Kaczynski left false clues in most bombs, which he intentionally made hard to find to make them appear more legitimate. Clues included metal plates stamped with the initials "FC" hidden somewhere (usually in the pipe end cap) in bombs, a note left in a bomb that did not detonate reading "Wu—It works! I told you it would—RV," and the Eugene O'Neill

Eugene Gladstone O'Neill (October 16, 1888 – November 27, 1953) was an American playwright and Nobel laureate in literature. His poetically titled plays were among the first to introduce into the U.S. the drama techniques of realism, earlier ...

one-dollar stamps often used as postage on his boxes. He sent one bomb embedded in a copy of Sloan Wilson's novel ''Ice Brothers''. The FBI theorized that Kaczynski's crimes involved a theme of nature, trees and wood. He often included bits of a tree branch and bark in his bombs; his selected targets included Percy Wood and Professor Leroy Wood. The crime writer Robert Graysmith

Robert Graysmith (born Robert Gray Smith; September 17, 1942) is an American true crime author and former cartoonist. He is known for his work on the Zodiac killer case.

Career

Graysmith worked as a political cartoonist for the ''San Francisc ...

noted his "obsession with wood" was "a large factor" in the bombings.

Later bombings

In 1981, a package bearing the return address of a

In 1981, a package bearing the return address of a Brigham Young University

Brigham Young University (BYU, sometimes referred to colloquially as The Y) is a private research university in Provo, Utah. It was founded in 1875 by religious leader Brigham Young and is sponsored by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day ...

professor of electrical engineering, LeRoy Wood Bearnson, was discovered in a hallway at the University of Utah

The University of Utah (U of U, UofU, or simply The U) is a public research university in Salt Lake City, Utah. It is the flagship institution of the Utah System of Higher Education. The university was established in 1850 as the University of De ...

. It was brought to the campus police, and was defused by a bomb squad

Bomb disposal is an explosives engineering profession using the process by which hazardous explosive devices are rendered safe. ''Bomb disposal'' is an all-encompassing term to describe the separate, but interrelated functions in the militar ...

. In May of the following year, a bomb was sent to Patrick C. Fischer

Patrick Carl Fischer (December 3, 1935 – August 26, 2011) was an American computer scientist, a noted researcher in computational complexity theory and database theory, and a target of the Unabomber..Vanderbilt University

Vanderbilt University (informally Vandy or VU) is a private research university in Nashville, Tennessee. Founded in 1873, it was named in honor of shipping and rail magnate Cornelius Vanderbilt, who provided the school its initial $1-million ...

. Fischer was on vacation in Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico (; abbreviated PR; tnq, Boriken, ''Borinquen''), officially the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico ( es, link=yes, Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico, lit=Free Associated State of Puerto Rico), is a Caribbean island and Unincorporated ...

at the time; his secretary, Janet Smith, opened the bomb and received injuries to her face and arms.

Kaczynski's next two bombs targeted people at the University of California, Berkeley. The first, in July 1982, caused serious injuries to engineering professor Diogenes Angelakos

Diogenes James Angelakos (July 3, 1919 – June 7, 1997) was an American electrical engineer and professor emeritus of electronic engineering at the University of California, Berkeley, who served as the director of the Electronics Research Labora ...

. Nearly three years later, in May 1985, John Hauser, a graduate student and captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

in the United States Air Force

The United States Air Force (USAF) is the air service branch of the United States Armed Forces, and is one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. Originally created on 1 August 1907, as a part of the United States Army Signal ...

, lost four fingers and the vision in one eye. Kaczynski handcrafted the bomb from wooden parts. A bomb sent to the Boeing Company

The Boeing Company () is an American multinational corporation that designs, manufactures, and sells airplanes, rotorcraft, rockets, satellites, telecommunications equipment, and missiles worldwide. The company also provides leasing and product ...

in Auburn, Washington

Auburn is a city in King County, Washington, United States (with a small portion crossing into neighboring Pierce County). The population was 87,256 at the 2020 Census. Auburn is a suburb in the Seattle metropolitan area, and is currently rank ...

, was defused by a bomb squad

Bomb disposal is an explosives engineering profession using the process by which hazardous explosive devices are rendered safe. ''Bomb disposal'' is an all-encompassing term to describe the separate, but interrelated functions in the militar ...

the following month. In November 1985, professor James V. McConnell

James V. McConnell (October 26, 1925 – April 9, 1990) was an American biologist and animal psychologist. He is most known for his research on learning and memory transfer in planarians conducted in the 1950s and 1960s. McConnell also publish ...

and research assistant Nicklaus Suino were both severely injured after Suino opened a mail bomb addressed to McConnell.

In late 1985, a nail-and-splinter-loaded bomb placed in the parking lot of his store in Sacramento, California

)

, image_map = Sacramento County California Incorporated and Unincorporated areas Sacramento Highlighted.svg

, mapsize = 250x200px

, map_caption = Location within Sacramento C ...

, killed 38-year-old computer store owner Hugh Scrutton. A similar attack against a computer store took place in Salt Lake City

Salt Lake City (often shortened to Salt Lake and abbreviated as SLC) is the Capital (political), capital and List of cities and towns in Utah, most populous city of Utah, United States. It is the county seat, seat of Salt Lake County, Utah, Sal ...

, Utah, on February 20, 1987. The bomb, disguised as a piece of lumber, injured Gary Wright when he attempted to remove it from the store's parking lot. The explosion severed nerves in Wright's left arm and propelled over 200 pieces of shrapnel

Shrapnel may refer to:

Military

* Shrapnel shell, explosive artillery munitions, generally for anti-personnel use

* Shrapnel (fragment), a hard loose material

Popular culture

* ''Shrapnel'' (Radical Comics)

* ''Shrapnel'', a game by Adam C ...

into his body. Kaczynski was spotted while planting the Salt Lake City bomb. This led to a widely distributed sketch of the suspect as a hooded man with a mustache and aviator sunglasses

Aviator sunglasses are a style of sunglasses that were developed by a group of American firms. The original Bausch & Lomb design is now commercially marketed as Ray-Ban Aviators, although other manufacturers also produce aviator-style sunglass ...

.

In 1993, after a six-year break, Kaczynski mailed a bomb to the home of Charles Epstein from the University of California, San Francisco

The University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) is a public land-grant research university in San Francisco, California. It is part of the University of California system and is dedicated entirely to health science and life science. It cond ...

. Epstein lost several fingers upon opening the package. In the same weekend, Kaczynski mailed a bomb to David Gelernter

David Hillel Gelernter (born March 5, 1955) is an American computer scientist, artist, and writer. He is a professor of computer science at Yale University.

Gelernter is known for contributions to parallel computation in the 1980s, and for books ...

, a computer science

Computer science is the study of computation, automation, and information. Computer science spans theoretical disciplines (such as algorithms, theory of computation, information theory, and automation) to Applied science, practical discipli ...

professor

Professor (commonly abbreviated as Prof.) is an Academy, academic rank at university, universities and other post-secondary education and research institutions in most countries. Literally, ''professor'' derives from Latin as a "person who pr ...

at Yale University

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the wo ...

. Gelernter lost sight in one eye, hearing in one ear, and a portion of his right hand.

In 1994, Burson-Marsteller

Burson Cohn & Wolfe is a multinational public relations and communications firm, headquartered in New York City. In February 2018, parent WPP Group PLC announced that it had merged its subsidiaries Cohn & Wolfe with Burson-Marsteller. The comb ...

executive Thomas J. Mosser was killed after opening a mail bomb sent to his home in New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York; on the east, southeast, and south by the Atlantic Ocean; on the west by the Delaware ...

. In a letter to ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'', Kaczynski wrote he had sent the bomb because of Mosser's work repairing the public image of Exxon

ExxonMobil Corporation (commonly shortened to Exxon) is an American multinational oil and gas corporation headquartered in Irving, Texas. It is the largest direct descendant of John D. Rockefeller's Standard Oil, and was formed on November 30, ...

after the ''Exxon Valdez'' oil spill. This was followed by the 1995 murder of Gilbert Brent Murray, president of the timber industry

Lumber is wood that has been processed into dimensional lumber, including beams and planks or boards, a stage in the process of wood production

Lumber and wood products, including timber for framing, plywood, and woodworking, are create ...

lobbying group

In politics, lobbying, persuasion or interest representation is the act of lawfully attempting to influence the actions, policies, or decisions of government officials, most often legislators or members of regulatory agencies. Lobbying, which ...

California Forestry Association, by a mail bomb addressed to previous president William Dennison, who had retired. Geneticist Phillip Sharp

Phillip Allen Sharp (born June 6, 1944) is an American geneticist and molecular biologist who co-discovered RNA splicing. He shared the 1993 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with Richard J. Roberts for "the discovery that genes in eukaryo ...

at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is a private land-grant research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Established in 1861, MIT has played a key role in the development of modern technology and science, and is one of the ...

received a threatening letter shortly afterwards.

Manifesto

In 1995, Kaczynski mailed several letters to media outlets outlining his goals and demanding a major newspaper print his 35,000-word essay ''Industrial Society and Its Future'' (dubbed the "Unabomber manifesto" by the FBI) verbatim. He stated he would "desist from terrorism" if this demand was met. There was controversy as to whether the essay should be published, but Attorney General

In 1995, Kaczynski mailed several letters to media outlets outlining his goals and demanding a major newspaper print his 35,000-word essay ''Industrial Society and Its Future'' (dubbed the "Unabomber manifesto" by the FBI) verbatim. He stated he would "desist from terrorism" if this demand was met. There was controversy as to whether the essay should be published, but Attorney General Janet Reno

Janet Wood Reno (July 21, 1938 – November 7, 2016) was an American lawyer who served as the 78th United States attorney general. She held the position from 1993 to 2001, making her the second-longest serving attorney general, behind only Wi ...

and FBI Director Louis Freeh

Louis Joseph Freeh (born January 6, 1950) is an American attorney and former judge who served as the fifth Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation from September 1993 to June 2001.

Graduated from Rutgers University and New York Universi ...

recommended its publication out of concern for public safety and in the hope that a reader could identify the author. Bob Guccione

Robert Charles Joseph Edward Sabatini Guccione ( ; December 17, 1930 – October 20, 2010) was an American photographer and publisher. He founded the adult magazine ''Penthouse'' in 1965. This was aimed at competing with Hugh Hefner's ''Playboy'', ...

of ''Penthouse

Penthouse most often refers to:

*Penthouse apartment, a special apartment on the top floor of a building

*Penthouse (magazine), ''Penthouse'' (magazine), a British-founded men's magazine

*Mechanical penthouse, a floor, typically located directly u ...

'' volunteered to publish it. Kaczynski replied ''Penthouse'' was less "respectable" than ''The New York Times'' and ''The Washington Post

''The Washington Post'' (also known as the ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'') is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C. It is the most widely circulated newspaper within the Washington metropolitan area and has a large nati ...

'', and said that, "to increase our chances of getting our stuff published in some 'respectable' periodical", he would "reserve the right to plant one (and only one) bomb intended to kill, after our manuscript has been published" if ''Penthouse'' published the document instead of ''The Times'' or ''The Post''. ''The Washington Post'' published the essay on September 19, 1995.

Kaczynski used a typewriter

A typewriter is a mechanical or electromechanical machine for typing characters. Typically, a typewriter has an array of keys, and each one causes a different single character to be produced on paper by striking an inked ribbon selectivel ...

to write his manuscript, capitalizing entire words for emphasis, in lieu of italics. He always referred to himself as either "we" or "FC" ("Freedom Club"), though there is no evidence that he worked with others. Donald Wayne Foster

Donald Wayne Foster (born 1950) was a professor of English at Vassar College in New York. He is now retired. He is known for his work dealing with various issues of Shakespearean authorship through textual analysis. He has also applied these tec ...

analyzed the writing at the request of Kaczynski's defense team in 1996 and noted that it contained irregular spelling and hyphenation, along with other linguistic idiosyncrasies. This led him to conclude that Kaczynski was its author.

Summary

''Industrial Society and Its Future'' begins with Kaczynski's assertion: "TheIndustrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

and its consequences have been a disaster for the human race."Kaczynski (1995), p. 1. He writes that technology has had a destabilizing effect on society, has made life unfulfilling, and has caused widespread psychological suffering. Kaczynski argues that most people spend their time engaged in useless pursuits because of technological advances; he calls these "surrogate activities", wherein people strive toward artificial goals, including scientific work, consumption of entertainment, political activism and following sports teams. He predicts that further technological advances will lead to extensive human genetic engineering

Genetic engineering, also called genetic modification or genetic manipulation, is the modification and manipulation of an organism's genes using technology. It is a set of technologies used to change the genetic makeup of cells, including t ...

, and that human beings will be adjusted to meet the needs of social systems, rather than ''vice versa''. Kaczynski states that technological progress can be stopped, in contrast to the viewpoint of people who he says understand technology's negative effects yet passively accept technology as inevitable. He calls for a return to primitivist lifestyles. Kaczynski's critiques of civilization bear some similarities to anarcho-primitivism

Anarcho-primitivism is an anarchist critique of civilization (anti-civ) that advocates a return to non-civilized ways of life through deindustrialization, abolition of the division of labor or specialization, and abandonment of large-scale organ ...

, but he rejected and criticized anarcho-primitivist views.

Kaczynski argues that the erosion of human freedom is a natural product of an industrial society because "the system has to regulate human behavior closely in order to function", and that reform of the system is impossible as drastic changes to it would not be implemented because of their disruption of the system. He states that the system has not yet fully achieved control over all human behavior and is in the midst of a struggle to gain that control. Kaczynski predicts that the system will break down if it cannot achieve significant control, and that it is likely this issue will be decided within the next 40 to 100 years. He states that the task of those who oppose industrial society is to promote stress within and upon the society and to propagate an anti-technology ideology, one that offers the "counter-ideal" of nature. Kaczynski goes on to say that a revolution will be possible only when industrial society is sufficiently unstable.

A significant portion of the document is dedicated to discussing left-wing politics

Left-wing politics describes the range of Ideology#Political%20ideologies, political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy. Left-wing politics typically in ...

, with Kaczynski attributing many of society's issues to leftists. He defines leftists as "mainly socialists

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the eco ...

, collectivists, 'politically correct

''Political correctness'' (adjectivally: ''politically correct''; commonly abbreviated ''PC'') is a term used to describe language, policies, or measures that are intended to avoid offense or disadvantage to members of particular groups in socie ...

' types, feminists

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social equality of the sexes. Feminism incorporates the position that society prioritizes the male poi ...

, gay

''Gay'' is a term that primarily refers to a homosexual person or the trait of being homosexual. The term originally meant 'carefree', 'cheerful', or 'bright and showy'.

While scant usage referring to male homosexuality dates to the late 1 ...

and disability activists, animal rights activists

The animal rights (AR) movement, sometimes called the animal liberation, animal personhood, or animal advocacy movement, is a social movement that seeks an end to the rigid moral and legal distinction drawn between human and non-human animals, ...

and the like". He believes that over-socialization and feelings of inferiority are primary drivers of leftism, and derides it as "one of the most widespread manifestations of the craziness of our world". Kaczynski adds that the type of movement he envisions must be anti-leftist and refrain from collaboration with leftists, as, in his view, "leftism is in the long run inconsistent with wild nature, with human freedom and with the elimination of modern technology". He also criticizes conservatives

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

, describing them as "fools who whine about the decay of traditional values, yet... enthusiastically support technological progress and economic growth", things he argues have led to this decay.

Contemporary reception

James Q. Wilson

James Quinn Wilson (May 27, 1931 – March 2, 2012) was an American political scientist and an authority on public administration. Most of his career was spent as a professor at UCLA and Harvard University. He was the chairman of the Council of A ...

, in a 1998 ''New York Times'' Op-Ed

An op-ed, short for "opposite the editorial page", is a written prose piece, typically published by a North-American newspaper or magazine, which expresses the opinion of an author usually not affiliated with the publication's editorial board. O ...

, wrote: "If it is the work of a madman, then the writings of many political philosophers—Jean Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; 28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) was a Genevan philosopher, writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment throughout Europe, as well as aspects of the French Revolu ...

, Tom Paine

Thomas Paine (born Thomas Pain; – In the contemporary record as noted by Conway, Paine's birth date is given as January 29, 1736–37. Common practice was to use a dash or a slash to separate the old-style year from the new-style year. In th ...

, Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist, critic of political economy, and socialist revolutionary. His best-known titles are the 1848 ...

—are scarcely more sane.""The Unabomber does not like socialization, technology, leftist political causes or conservative attitudes. Apart from his call for an (unspecified) revolution, his paper resembles something that a very good graduate student might have written."Alston Chase, a fellow alumnus of

Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

wrote in 2000 for ''The Atlantic

''The Atlantic'' is an American magazine and multi-platform publisher. It features articles in the fields of politics, foreign affairs, business and the economy, culture and the arts, technology, and science.

It was founded in 1857 in Boston, ...

'' that "It is true that many believed Kaczynski was insane because they needed to believe it. But the truly disturbing aspect of Kaczynski and his ideas is not that they are so foreign but that they are so familiar." He argued that "We need to see Kaczynski as exceptional—madman or genius—because the alternative is so much more frightening."

Other works

University of Michigan–Dearborn

The University of Michigan–Dearborn (U of M Dearborn, UM–Dearborn, or UMD) is a public university in Dearborn, Michigan. It is one of the two regional universities operating under the policies of the University of Michigan Board of Regents, ...

philosophy professor David Skrbina

The 2006 Michigan gubernatorial election was one of the 36 U.S. gubernatorial elections held November 7, 2006. Incumbent Democratic Governor of Michigan Jennifer Granholm was re-elected with 56% of the vote over Republican businessman Dick DeVo ...

helped to compile Kaczynski's work into the 2010 anthology ''Technological Slavery'', including the original manifesto, letters between Skrbina and Kaczynski, and other essays. Kaczynski updated his 1995 manifesto as '' Anti-Tech Revolution: Why and How'' to address advances in computers and the internet. He advocates practicing other types of protest and makes no mention of violence.

According to a 2021 study, Kaczynski's manifesto "is a synthesis of ideas from three well-known academics: French philosopher Jacques Ellul

Jacques Ellul (; ; January 6, 1912 – May 19, 1994) was a French philosopher, sociologist, lay theologian, and professor who was a noted Christian anarchist. Ellul was a longtime Professor of History and the Sociology of Institutions on t ...

, British zoologist Desmond Morris

Desmond John Morris FLS ''hon. caus.'' (born 24 January 1928) is an English zoologist, ethologist and surrealist painter, as well as a popular author in human sociobiology. He is known for his 1967 book ''The Naked Ape'', and for his televisi ...

, and American psychologist Martin Seligman

Martin Elias Peter Seligman (; born August 12, 1942) is an American psychologist, educator, and author of self-help books. Seligman is a strong promoter within the scientific community of his theories of positive psychology and of well-being. His ...

."

Investigation

Because of the material used to make the mail bombs, U.S. postal inspectors, who initially had responsibility for the case, labeled the suspect the "Junkyard Bomber". FBI Inspector Terry D. Turchie was appointed to run the UNABOM (University and Airline Bomber) investigation. In 1979, an FBI-led task force that included 125 agents from the FBI, the

Because of the material used to make the mail bombs, U.S. postal inspectors, who initially had responsibility for the case, labeled the suspect the "Junkyard Bomber". FBI Inspector Terry D. Turchie was appointed to run the UNABOM (University and Airline Bomber) investigation. In 1979, an FBI-led task force that included 125 agents from the FBI, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms

The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (BATFE), commonly referred to as the ATF, is a domestic law enforcement agency within the United States Department of Justice. Its responsibilities include the investigation and preven ...