The Night Of January 16th on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Night of January 16th'' (sometimes advertised as ''The Night of January 16th'') is a

Soon after she rejected the offer from Woods, Rand accepted an offer from Welsh actor

Soon after she rejected the offer from Woods, Rand accepted an offer from Welsh actor

When the play's success on Broadway was clear, Woods launched productions of the play in other cities, starting with San Francisco. It opened there at the

When the play's success on Broadway was clear, Woods launched productions of the play in other cities, starting with San Francisco. It opened there at the

The second act continues the prosecution's case, with Flint calling John Graham Whitfield—Faulkner's father-in-law and president of Whitfield National Bank. He testifies about a large loan he made to Faulkner. In his

The second act continues the prosecution's case, with Flint calling John Graham Whitfield—Faulkner's father-in-law and president of Whitfield National Bank. He testifies about a large loan he made to Faulkner. In his

Although best known as ''Night of January 16th'', the play's title changed multiple times and several alternative titles were considered. Rand's working title was ''Penthouse Legend''. When Clive picked up the play, he thought Rand's title suggested a fantasy story that would discourage potential patrons. The play was called ''The Verdict'' during the Hollywood Playhouse rehearsals, but opened there with the title ''Woman on Trial''. When Woods took the play to Broadway, he insisted on a new title. He offered Rand a choice between ''The Black Sedan'' and ''Night of January 16th''. Rand liked neither, but picked the latter.; Woods later suggested two more name changes, but did not implement them. Prior to the opening, he considered renaming the play ''The Night is Young''. After the play opened, he considered changing its name each day to match the current date.

When Rand published her version of the play in 1968, she wrote that although she disliked the Broadway title, it was too well known to change it again. She agreed to using ''Penthouse Legend'' as the title for the 1973 revival production.

Although best known as ''Night of January 16th'', the play's title changed multiple times and several alternative titles were considered. Rand's working title was ''Penthouse Legend''. When Clive picked up the play, he thought Rand's title suggested a fantasy story that would discourage potential patrons. The play was called ''The Verdict'' during the Hollywood Playhouse rehearsals, but opened there with the title ''Woman on Trial''. When Woods took the play to Broadway, he insisted on a new title. He offered Rand a choice between ''The Black Sedan'' and ''Night of January 16th''. Rand liked neither, but picked the latter.; Woods later suggested two more name changes, but did not implement them. Prior to the opening, he considered renaming the play ''The Night is Young''. After the play opened, he considered changing its name each day to match the current date.

When Rand published her version of the play in 1968, she wrote that although she disliked the Broadway title, it was too well known to change it again. She agreed to using ''Penthouse Legend'' as the title for the 1973 revival production.

The selection of a jury from the play's audience was the primary dramatic innovation of ''Night of January 16th''. It created concerns among many of the producers who considered and rejected the play. Although Woods liked the idea, Hayden worried it would destroy the theatrical illusion; he feared audience members might refuse to participate. Successful jury selections during previews indicated this would not be a problem. This criticism dissipated following the play's success; it became famous for its "jury gimmick".

The play's jury has sometimes enlisted famous participants; the Broadway selections were rigged to call on celebrities known to be in the audience. The jury for the Broadway opening included attorney Edward J. Reilly—who was known from the

The selection of a jury from the play's audience was the primary dramatic innovation of ''Night of January 16th''. It created concerns among many of the producers who considered and rejected the play. Although Woods liked the idea, Hayden worried it would destroy the theatrical illusion; he feared audience members might refuse to participate. Successful jury selections during previews indicated this would not be a problem. This criticism dissipated following the play's success; it became famous for its "jury gimmick".

The play's jury has sometimes enlisted famous participants; the Broadway selections were rigged to call on celebrities known to be in the audience. The jury for the Broadway opening included attorney Edward J. Reilly—who was known from the

Since its premiere, ''Night of January 16th'' has had a mixed reception. The initial Los Angeles run as ''Woman on Trial'' received complimentary reviews; Rand was disappointed that reviews focused on the play's melodrama and its similarity to ''The Trial of Mary Dugan'', while paying little attention to aspects she considered more important, such as the contrasting ideas of individualism and conformity. Although Rand later described the production as "badly handicapped by lack of funds" and "competent, but somewhat unexciting", it performed reasonably well at the box office during its short run.

The Broadway production received largely positive reviews that praised its melodrama and the acting of Nolan and Pidgeon. ''

Since its premiere, ''Night of January 16th'' has had a mixed reception. The initial Los Angeles run as ''Woman on Trial'' received complimentary reviews; Rand was disappointed that reviews focused on the play's melodrama and its similarity to ''The Trial of Mary Dugan'', while paying little attention to aspects she considered more important, such as the contrasting ideas of individualism and conformity. Although Rand later described the production as "badly handicapped by lack of funds" and "competent, but somewhat unexciting", it performed reasonably well at the box office during its short run.

The Broadway production received largely positive reviews that praised its melodrama and the acting of Nolan and Pidgeon. ''

The movie rights to ''Night of January 16th'' were initially purchased by

The movie rights to ''Night of January 16th'' were initially purchased by

theatrical play

A play is a work of drama, usually consisting mostly of dialogue between characters and intended for theatrical performance rather than just reading. The writer of a play is called a playwright.

Plays are performed at a variety of levels, fr ...

by Russian-American author Ayn Rand, inspired by the death of the "Match King", Ivar Kreuger

Ivar Kreuger (; 2 March 1880 – 12 March 1932) was a Swedish civil engineer, financier, entrepreneur and industrialist. In 1908, he co-founded the construction company Kreuger & Toll Byggnads AB, which specialized in new building techniques. B ...

. Set in a courtroom during a murder trial, an unusual feature of the play is that members of the audience are chosen to play the jury. The court hears the case of Karen Andre, a former secretary and lover of businessman Bjorn Faulkner, of whose murder she is accused. The play does not directly portray the events leading to Faulkner's death; instead the jury must rely on character testimony to decide whether Andre is guilty. The play's ending depends on the verdict. Rand's intention was to dramatize a conflict between individualism

Individualism is the moral stance, political philosophy, ideology and social outlook that emphasizes the intrinsic worth of the individual. Individualists promote the exercise of one's goals and desires and to value independence and self-reli ...

and conformity, with the jury's verdict revealing which viewpoint they preferred.

The play was first produced in 1934 in Los Angeles under the title ''Woman on Trial''; it received positive reviews and enjoyed moderate commercial success. Producer Al Woods took it to Broadway

Broadway may refer to:

Theatre

* Broadway Theatre (disambiguation)

* Broadway theatre, theatrical productions in professional theatres near Broadway, Manhattan, New York City, U.S.

** Broadway (Manhattan), the street

**Broadway Theatre (53rd Stree ...

during the 1935–36 season and re-titled it ''Night of January 16th''. It drew attention for its innovative audience-member jury and became a hit, running for seven months. Doris Nolan

Doris Nolan (July 14, 1916 – July 29, 1998) was an American actress best known for her Broadway roles and her appearance in the 1938 movie ''Holiday''. She appeared in plays and films during the 1930s and 1940s. Later she moved to the UK, w ...

, in her Broadway debut, received positive reviews for her portrayal of the lead role. Several regional productions followed. An off-Broadway revival in 1973, under the title ''Penthouse Legend'', was a commercial and critical failure. A film based on the play was released in 1941; the story has also been adapted for television and radio

Radio is the technology of signaling and communicating using radio waves. Radio waves are electromagnetic waves of frequency between 30 hertz (Hz) and 300 gigahertz (GHz). They are generated by an electronic device called a transmi ...

.

Rand had many heated disputes with Woods over script changes he wanted for the Broadway production. Their disputes climaxed in an arbitration hearing when Rand discovered Woods had diverted a portion of her royalties to pay for a script doctor. Rand disliked the changes made for the Broadway production and the version published for amateur productions, so in 1968 she re-edited the script for publication as the "definitive" version.

History

Background and first production

Rand drew inspiration for ''Night of January 16th'' from two sources. The first was ''The Trial of Mary Dugan

''The Trial of Mary Dugan'' is a play written by Bayard Veiller.

The 1927 melodrama concerns a sensational courtroom trial of a showgirl accused of killing her millionaire lover. Her defense attorney is her brother, Jimmy Dugan. It was first pr ...

'', a 1927 melodrama about a showgirl prosecuted for killing her wealthy lover, which gave Rand the idea to write a play featuring a trial. Rand wanted her play's ending to depend on the result of the trial, rather than having a fixed final scene. She based her victim on Ivar Kreuger

Ivar Kreuger (; 2 March 1880 – 12 March 1932) was a Swedish civil engineer, financier, entrepreneur and industrialist. In 1908, he co-founded the construction company Kreuger & Toll Byggnads AB, which specialized in new building techniques. B ...

, a Swedish businessman known as the "Match King" for the matchstick-manufacturing monopolies he owned, before he was found dead in March 1932. When Kreuger's business empire became financially unstable, he shot himself after being accused of executing underhanded and possibly illegal financial deals. This incident inspired Rand to make the victim a businessman of great ambition and dubious character, who had given several people motives for his murder.

Rand wrote ''Night of January 16th'' in 1933. She was 28 and had been in the United States for seven years after emigrating from the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

, where her strong anti-Communist opinions had put her at risk. Rand had never written a stage play, but had worked in Hollywood as a junior screenwriter for Cecil B. DeMille

Cecil Blount DeMille (; August 12, 1881January 21, 1959) was an American film director, producer and actor. Between 1914 and 1958, he made 70 features, both silent and sound films. He is acknowledged as a founding father of the American cine ...

, and later in RKO Studios

RKO Radio Pictures Inc., commonly known as RKO Pictures or simply RKO, was an American film production and distribution company, one of the "Big Five" film studios of Hollywood's Golden Age. The business was formed after the Keith-Albee-Orpheu ...

' wardrobe department. In September 1932, Rand sold an original screenplay, ''Red Pawn

''Red Pawn'' is a screenplay written by Ayn Rand. It was the first screenplay that Rand sold. Universal Pictures purchased it in 1932. ''Red Pawn'' features the theme of the evil of dictatorship, specifically of Soviet Russia.

''Red Pawn'' is a ...

'', to Universal Studios

Universal Pictures (legally Universal City Studios LLC, also known as Universal Studios, or simply Universal; common metonym: Uni, and formerly named Universal Film Manufacturing Company and Universal-International Pictures Inc.) is an Americ ...

and quit RKO to finish her first novel, ''We the Living

''We the Living'' is the debut novel of the Russian American novelist Ayn Rand. It is a story of life in post-revolutionary Russia and was Rand's first statement against communism. Rand observes in the foreword that ''We the Living'' was the cl ...

''. She wrote the stage play with the hope of making money from it while finishing her novel. By 1934 her agent was trying to sell the play and the novel, but both were repeatedly rejected. ''Red Pawn'' was shelved and Rand's contract for rewrites on it expired. Rand's husband, actor Frank O'Connor, was getting only minor roles with little pay, leaving the couple in financial difficulties. With the last of her money from ''Red Pawn'' exhausted, Rand got an offer for her new play from Al Woods, who had produced ''The Trial of Mary Dugan'' for Broadway. The contract included a condition that Woods could make changes to the script. Wary that he would destroy her vision of the play to create a more conventional drama, Rand turned Woods down.

Soon after she rejected the offer from Woods, Rand accepted an offer from Welsh actor

Soon after she rejected the offer from Woods, Rand accepted an offer from Welsh actor E. E. Clive

Edward Erskholme Clive (28 August 1879 – 6 June 1940) was a Welsh stage actor and director who had a prolific acting career in Britain and America. He also played numerous supporting roles in Hollywood movies between 1933 and his death.

Biog ...

to stage the play in Los Angeles. It first opened at the Hollywood Playhouse as ''Woman on Trial''; Clive produced, and Barbara Bedford played Andre. The production opened on October 22, 1934, and closed in late November.

Broadway production

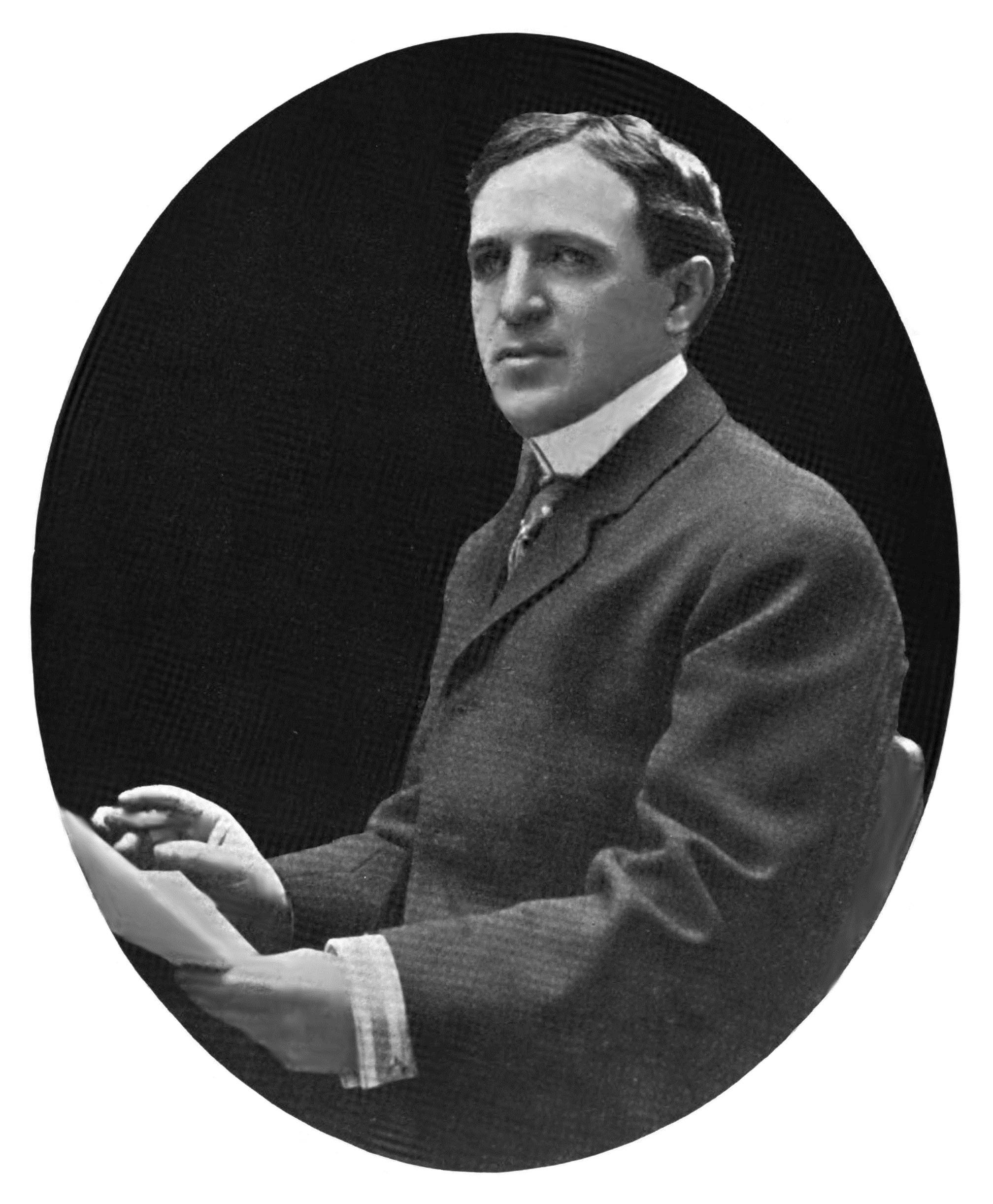

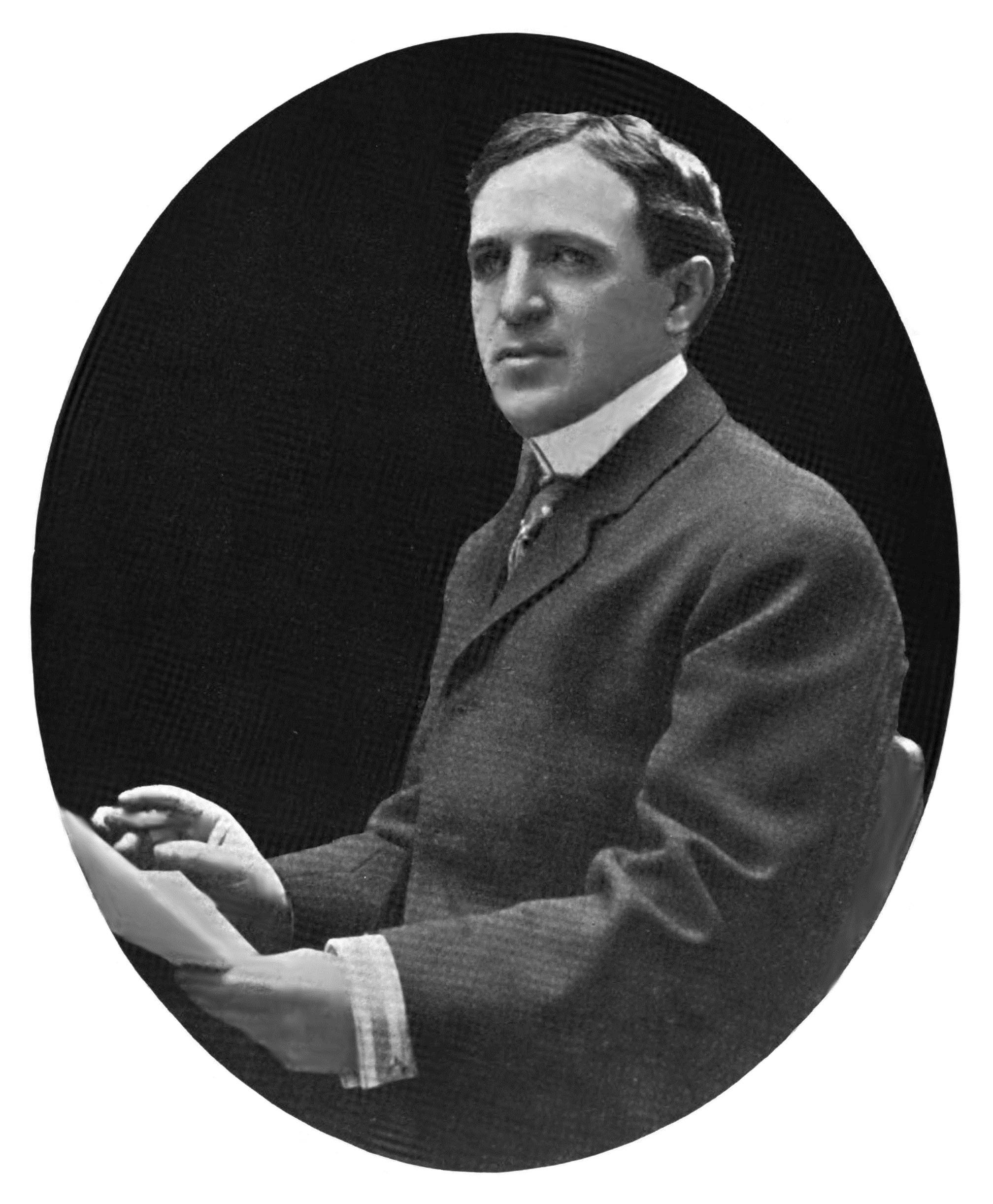

At the end of the play's run in Los Angeles, Woods renewed his offer to produce the play on Broadway. Although he was a renowned producer of many famous plays in a career of more than three decades, Woods had lost much of his fortune in the early 1930s and had not produced a hit in several years. Being refused by a neophyte author shocked him and increased his interest. Woods still wanted the right to make script changes, but he made adjustments to the contract to give Rand more influence. She reluctantly agreed to his terms. Rand arrived in New York City at the beginning of December 1934 in anticipation of the opening in January. The play's financing failed, delaying the production for several months until Woods arranged new financing from theater ownerLee Shubert

Lee Shubert (born Levi Schubart; March 25, 1871– December 25, 1953) was a Lithuanian-born American theatre owner/operator and producer and the eldest of seven siblings of the theatrical Shubert family.

Biography

Born to a Jewish family, the so ...

. When work resumed, Rand's relationship with Woods quickly soured as he demanded changes she later derided as "a junk heap of worn, irrelevant melodramatic devices". Woods had made his success on Broadway with low-brow melodramas such as ''Nellie, the Beautiful Cloak Model

''Nellie, the Beautiful Cloak Model'' is a play written by Owen Davis. A Broadway production of it by A. H. Woods opened in 1906 and was a huge hit. The story is a melodrama, and it was often cited as an archetype of the genre. Reata Winfield ...

'' and risqué comedies such as ''The Demi-Virgin

''The Demi-Virgin'' is a three- act play written by Avery Hopwood. Producer Albert H. Woods staged it on Broadway, where it was a hit during the 1921–22 season. The play is a bedroom farce about former couple Gloria Graham and Wally Deane, b ...

''. Woods was not interested in what he called Rand's "highfalutin speeches", preferring the dramatic conflict to focus on concrete elements, such as whether the defendant had a gun. The changes to Rand's work included the creation of a new character, a gun moll

A gun moll or gangster moll or gangster's moll is the female companion of a male professional criminal. "Gun" was British slang for thief, derived from Yiddish ''ganef'', from the Hebrew ''gannāb'' ( גנב). "Moll" is also used as a euphemism for ...

played by Shubert's mistress.

The contract between Woods and Rand allowed him to hire collaborators if he thought it necessary, paying them a limited portion of the author's royalties. He first hired John Hayden to direct, paying him one percentage point from Rand's 10-percent royalty. Although Hayden was a successful Broadway director, Rand disliked him and later called him "a very ratty Broadway hanger-on". As auditions for the play began in Philadelphia, Woods demanded further script changes and was frustrated by Rand's refusal to make some of them. He engaged Louis Weitzenkorn

Louis Weitzenkorn (May 28, 1893 – February 7, 1943) was an American writer and newspaper editor. He wrote a play about journalism, ''Five Star Final'', that became a hit on Broadway in 1931. It was adapted as a movie, and Weitzenkorn subsequentl ...

, the author of the previous hit ''Five Star Final

''Five Star Final'' is a 1931 American pre-Code drama film about the excesses of tabloid journalism directed by Mervyn LeRoy and starring Edward G. Robinson, Aline MacMahon (in her screen debut) and Boris Karloff. The screenplay was by Rober ...

'', to act as a script doctor. Rand's relationship with Weitzenkorn was worse than hers with Woods or Hayden; she and Weitzenkorn argued over political differences as well as his ideas for the play. Woods gave Weitzenkorn another percentage point from Rand's royalties without informing her. Rand filed a claim against Woods with the American Arbitration Association; she objected to Weitzenkorn receiving any portion of her royalties, and told the arbitration panel Weitzenkorn had added only a single line to the play, which was cut after the auditions. Upon hearing this testimony, one of the arbitrators responded incredulously, "That was he did?" In two hearings, the panel ruled that Weitzenkorn should receive his agreed-upon one percent, but that Woods could not deduct the payment from Rand's royalties because she had not been notified in advance. Despite the disputes between Rand and Woods, the play opened at Shubert's Ambassador Theatre on September 16, 1935, where it ran successfully for seven months. It closed on April 4, 1936, after 283 performances.;

Subsequent productions and publications

When the play's success on Broadway was clear, Woods launched productions of the play in other cities, starting with San Francisco. It opened there at the

When the play's success on Broadway was clear, Woods launched productions of the play in other cities, starting with San Francisco. It opened there at the Geary Theater Geary, an Anglicized rendering of the Irish name ''O'Gadhra'', has a number of meanings:

__NOTOC__ Places

* Geary, New Brunswick, Canada

* Geary, Isle of Skye, Scotland, a township

* Geary, Kansas, United States, a ghost town in Doniphan County

* ...

on December 30, 1935, and ran for five weeks with Nedda Harrigan

Nedda Harrigan Logan (August 24, 1899 – April 1, 1989) was an American actress.

Early life

Harrigan was the youngest of 10 children of entertainer Edward Harrigan and his wife, Annie (Braham) Harrigan. Her grandfather was conductor Davi ...

in the lead role. Harrigan stayed with the show when it moved to the El Capitan Theatre

El Capitan Theatre is a fully restored movie palace at 6838 Hollywood Blvd. in Hollywood. The theater and adjacent Hollywood Masonic Temple (now known as the El Capitan Entertainment Centre) is owned by The Walt Disney Company and serves as the ...

in Los Angeles, where it opened on March 1, 1936. After the Broadway production closed, Woods started a road tour that included productions in Boston and Chicago.

International productions of the play included shows in London, Montreal, and Sydney. The production in London opened on September 29, 1936, where Phoebe Foster

Phoebe Foster (born Angeline Egar; July 9, 1896 – June 1975) was an American theater and film actress.

Career

Foster studied at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts. She began appearing on Broadway in 1914, starting with a production of Roi ...

took the lead role for her first appearance on the London stage. It closed after 22 performances. A production in Montreal opened on June 16, 1941, starring Fay Wray

Vina Fay Wray (September 15, 1907 – August 8, 2004) was a Canadian/American actress best known for starring as Ann Darrow in the 1933 film ''King Kong''. Through an acting career that spanned nearly six decades, Wray attained international r ...

as Andre and Robert Wilcox as Regan. In Sydney, the play opened at the Minerva Theatre on June 19, 1944, with Thelma Grigg

Thelma Grigg (born Thelma Emerson, 13 September 1911 – 29 May 2003) was an Australian actress. She was first hired as an extra for Cinesound Productions in 1937. She made her stage debut in a 1939 production of '' The Women'' by Clare Boothe Lu ...

as Andre.

''Night of January 16th'' was first published in an edition for amateur theater organizations in 1936, using a version edited by drama professor Nathaniel Edward , which included further changes to eliminate elements such as swearing and smoking. Rand disavowed this version because of the changes. In 1960, Rand's protégé Nathaniel Branden

Nathaniel Branden (born Nathan Blumenthal; April 9, 1930 – December 3, 2014) was a Canadian–American psychotherapist and writer known for his work in the psychology of self-esteem. A former associate and romantic partner of Ayn Rand ...

asked about doing a public reading of the play for students at the Nathaniel Branden Institute

The Nathaniel Branden Institute (NBI), originally Nathaniel Branden Lectures, was an organization founded by Nathaniel Branden in 1958 to promote Ayn Rand's philosophy of Objectivism. The institute was responsible for many Objectivist lectures and ...

. Rand did not want him to use the amateur version; she created a revised text that eliminated most of Woods' and 's changes. She had her "final, definitive version" published in 1968 with an introduction about the play's history.

In 1972, Rand approved an off-Broadway revival of the play, which used her preferred version of the script, including several dozen further small changes in language beyond those in the 1968 version. The revival also used her original title, ''Penthouse Legend''. It was produced by Phillip and Kay Nolte Smith

Kay Nolte Smith (July 4, 1932 – September 25, 1993) was an American novelist, essayist, and translator. She was for a time friendly with the philosopher-novelist Ayn Rand, who was her leading literary and philosophical influence.

Smith was ...

, a married couple who were friends with Rand. Kay Smith also starred in the production under the stage name Kay Gillian. It opened at the McAlpin Rooftop Theater on February 22, 1973, and closed on March 18 after 30 performances.

''Night of January 16th'' was the last theatrical success for either Rand or Woods. Rand's next play, ''Ideal

Ideal may refer to:

Philosophy

* Ideal (ethics), values that one actively pursues as goals

* Platonic ideal, a philosophical idea of trueness of form, associated with Plato

Mathematics

* Ideal (ring theory), special subsets of a ring considere ...

'', went unsold, and a 1940 stage adaptation of ''We the Living'' flopped. Rand achieved lasting success and financial stability with her 1943 novel, ''The Fountainhead

''The Fountainhead'' is a 1943 novel by Russian-American author Ayn Rand, her first major literary success. The novel's protagonist, Howard Roark, is an intransigent young architect, who battles against conventional standards and refuses to comp ...

''. Woods produced several more plays; none were hits and when he died in 1951, he was bankrupt and living in a hotel.

Synopsis

The plot of ''Night of January 16th'' centers on the trial of secretary Karen Andre for the murder of her employer, business executive Bjorn Faulkner, who defrauded his company of millions of dollars to invest in the gold trade. In the wake of a financial crash, he was facing bankruptcy. The play's events occur entirely in a courtroom; Faulkner is never seen. On the night of January 16, Faulkner and Andre were in the penthouse of the Faulkner Building in New York City, when Faulkner apparently fell to his death. Within the threeacts

The Acts of the Apostles ( grc-koi, Πράξεις Ἀποστόλων, ''Práxeis Apostólōn''; la, Actūs Apostolōrum) is the fifth book of the New Testament; it tells of the founding of the Christian Church and the spread of its message ...

, the prosecutor Mr. Flint and Andre's defense attorney Mr. Stevens call witnesses whose testimonies build conflicting stories.

At the beginning of the first act, the judge asks the court clerk to call jurors from the audience. Once the jurors are seated, the prosecution argument begins. Flint explains that Andre was not just Faulkner's secretary, but also his lover. He says Faulkner jilted her to marry Nancy Lee Whitfield and fired Andre, motivating Andre to murder him. Flint then calls a series of witnesses, starting with the medical examiner, who testifies that Faulkner's body was so damaged by the fall that it was impossible to determine whether he was killed by the impact or was already dead. An elderly night watchman and a private investigator describe the events they saw that evening. A police inspector testifies to finding a suicide note. Faulkner's very religious housekeeper disapprovingly describes the sexual relationship between Andre and Faulkner, and says she saw Andre with another man after Faulkner's marriage. Nancy Lee testifies about her and Faulkner's courtship and marriage, portraying both as idyllic. The act ends with Andre speaking out of turn to accuse Nancy Lee of lying.

cross-examination

In law, cross-examination is the interrogation of a witness called by one's opponent. It is preceded by direct examination (in Ireland, the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, South Africa, India and Pakistan known as examination-in-chief) and ...

, defense attorney Stevens suggests the loan was used to buy Faulkner's marriage to Whitfield's daughter. After this testimony, the prosecution rests and the defense argument begins. A handwriting expert testifies about the signature on the suicide note. Faulkner's bookkeeper describes events between Andre's dismissal and the night of Faulkner's death, and related financial matters. Andre takes the stand and describes her relationship with Faulkner as both his lover and his partner in financial fraud. She says she did not resent his marriage because it was a business deal to secure credit from the Whitfield Bank. As she starts to explain the reasons for Faulkner's alleged suicide, she is interrupted by the arrival of "Guts" Regan, an infamous gangster, who tells Andre that Faulkner is dead. Despite being on trial for Faulkner's murder, Andre is shocked by this news and faints.

The final act continues Andre's testimony; she is now somber rather than defiant. She says that she, Faulkner, and Regan had conspired to fake Faulkner's suicide so they could escape with money stolen from Whitfield. Regan, who was also in love with Andre, provided the stolen body of his already-dead gang associate, "Lefty" O'Toole, to throw from the building. In cross-examination, Flint suggests Andre and Regan were using knowledge of past criminal activities to blackmail Faulkner. Stevens then calls Regan, who testifies that he was due to meet Faulkner at a getaway plane after leaving the stolen body with Andre; however, Faulkner did not arrive and the plane was missing. Instead of Faulkner, Regan encountered Whitfield, who gave him a check that was, according to Regan, to buy his silence. Regan later found the missing plane, which had been burned with what he presumes is Faulkner's body inside. Flint's cross-examination offers an alternative theory: Regan put the stolen body into the plane to create doubt about Andre's guilt, and the check from Whitfield was protection money to Regan's gang. In the play's Broadway and amateur versions, the next witness is Roberta Van Rensselaer, an exotic dancer and wife of O'Toole, who believes Regan killed her husband. This character does not appear in Rand's preferred version of the play. Stevens then recalls two witnesses to follow up on issues from Regan's testimony. The defense and prosecution then give their closing arguments.

The jury retires to vote while the characters repeat highlights from their testimony under a spotlight. The jury then returns to announce its verdict. One of two short endings follows. If found not guilty, Andre thanks the jury. If found guilty, she says the jury have spared her from committing suicide. In Reeid's amateur version, after either verdict the judge berates the jurors for their bad judgment and declares that they cannot serve on a jury again.

Title

Broadway cast and characters

The play's protagonist and lead female role is the defendant, Karen Andre. Woods considered several actresses for the role, but with Rand's support he cast an unusual choice, an actress namedDoris Nolan

Doris Nolan (July 14, 1916 – July 29, 1998) was an American actress best known for her Broadway roles and her appearance in the 1938 movie ''Holiday''. She appeared in plays and films during the 1930s and 1940s. Later she moved to the UK, w ...

. It was Nolan's Broadway debut; her previous professional acting experience was a failed attempt at completing a movie scene. At 17 years old, she was cast as a presumably older femme fatale. Woods was Nolan's manager and got a commission from her contract. Nolan was inexperienced and was nervous throughout rehearsals. When other actresses visited, she feared they were there to replace her. Although Rand later said she was "not a sensational actress", reviewers praised her performance. Nolan left the cast in March to take a movie contract from Universal Studios

Universal Pictures (legally Universal City Studios LLC, also known as Universal Studios, or simply Universal; common metonym: Uni, and formerly named Universal Film Manufacturing Company and Universal-International Pictures Inc.) is an Americ ...

.

Rand actively pushed for Walter Pidgeon

Walter Davis Pidgeon (September 23, 1897 – September 25, 1984) was a Canadian-American actor. He earned two Academy Award for Best Actor nominations for his roles in '' Mrs. Miniver'' (1942) and ''Madame Curie'' (1943). Pidgeon also starred in ...

to be cast in the role of "Guts" Regan. Woods objected at first, but eventually gave Pidgeon the part. As with Nolan, reviewers approved the choice. Pidgeon left the production after about a month to take a role in another play, '' There's Wisdom in Women''. Despite Rand's objections, he was replaced with William Bakewell

William Bakewell (May 2, 1908 – April 15, 1993) was an American actor who achieved his greatest fame as one of the leading juvenile performers of the late 1920s and early 1930s.

Early years

Bakewell was a native of Los Angeles, where he at ...

; Rand recommended Morgan Conway

Morgan Conway (born Sidney Conway, March 16, 1903 – November 16, 1981) was an American actor, best known for his portrayals of Dick Tracy.

Early life and career

Conway was educated at Columbia University in New York City. He had a bro ...

, who played the same role in ''Woman on Trial''.;

Dramatic analysis

Jury element

The selection of a jury from the play's audience was the primary dramatic innovation of ''Night of January 16th''. It created concerns among many of the producers who considered and rejected the play. Although Woods liked the idea, Hayden worried it would destroy the theatrical illusion; he feared audience members might refuse to participate. Successful jury selections during previews indicated this would not be a problem. This criticism dissipated following the play's success; it became famous for its "jury gimmick".

The play's jury has sometimes enlisted famous participants; the Broadway selections were rigged to call on celebrities known to be in the audience. The jury for the Broadway opening included attorney Edward J. Reilly—who was known from the

The selection of a jury from the play's audience was the primary dramatic innovation of ''Night of January 16th''. It created concerns among many of the producers who considered and rejected the play. Although Woods liked the idea, Hayden worried it would destroy the theatrical illusion; he feared audience members might refuse to participate. Successful jury selections during previews indicated this would not be a problem. This criticism dissipated following the play's success; it became famous for its "jury gimmick".

The play's jury has sometimes enlisted famous participants; the Broadway selections were rigged to call on celebrities known to be in the audience. The jury for the Broadway opening included attorney Edward J. Reilly—who was known from the Lindbergh kidnapping

On March 1, 1932, Charles Augustus Lindbergh Jr. (born June 22, 1930), the 20-month-old son of aviators Charles Lindbergh and Anne Morrow Lindbergh, was abducted from his crib in the upper floor of the Lindberghs' home, Highfields, in East Am ...

trial earlier that year—and boxing champion Jack Dempsey

William Harrison "Jack" Dempsey (June 24, 1895 – May 31, 1983), nicknamed Kid Blackie and The Manassa Mauler, was an American professional boxer who competed from 1914 to 1927, and reigned as the world heavyweight champion from 1919 to 1926 ...

. At a special performance for the blind, Helen Keller sat on the jury. The practice of using celebrity jurors continued throughout the Broadway run and in other productions.

Woods decided the jury for the Broadway run would employ some jury service rules of the New York courts. One such rule was the payment of jurors three dollars per day for their participation, which meant the selected audience members profited by at least 25 cents after subtracting the ticket price. Another was that only men could serve on a jury, although Woods made exceptions, for example at the performance Keller attended. He later loosened the rule to allow women jurors at matinee performances twice a week. Unlike a normal criminal trial, verdicts required only a majority vote rather than unanimity.

Themes

Rand described ''Night of January 16th'' as "a sense-of-life play". She did not want its events to be taken literally, but to be understood as a representation of different ways of approaching life. Andre represents an ambitious, confident, non-conformist approach to life, while the prosecution witnesses represent conformity, envy of success, and the desire for power over others. Rand believed the jury's decision at each performance revealed the attitude of the jurors towards these two conflicting senses of life. Rand supported individualism and considered Andre "not guilty". She said she wanted the play to convey the viewpoint: "Your life, your achievement, your happiness, are of paramount importance. Live up to your highest vision of yourself no matter what the circumstances you might encounter. An exalted view of self-esteem is man's most admirable quality". She said the play "is not a philosophical treatise on morality" and represents this view only in a basic way. Rand would later expound an explicit philosophy, which she called "Objectivism

Objectivism is a philosophical system developed by Russian-American writer and philosopher Ayn Rand. She described it as "the concept of man as a heroic being, with his own happiness as the moral purpose of his life, with productive achievemen ...

", particularly in her 1957 novel '' Atlas Shrugged'' and in non-fiction essays, but ''Night of January 16th'' predates these more philosophical works.

Several later commentators have interpreted the play as a reflection of Rand's early interest in the ideas of German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (; or ; 15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a German philosopher, prose poet, cultural critic, philologist, and composer whose work has exerted a profound influence on contemporary philosophy. He began his ...

. Literature professor Shoshana Milgram saw elements of Nietzsche's morality in the descriptions of Bjorn Faulkner, who "never thought of things as right or wrong". Others found significance in Rand's admiration of the play's criminal characters. Historian Jennifer Burns said Rand "found criminality an irresistible metaphor for individualism" because of the influence on her of "Nietzsche's transvaluation of values hat

A hat is a head covering which is worn for various reasons, including protection against weather conditions, ceremonial reasons such as university graduation, religious reasons, safety, or as a fashion accessory. Hats which incorporate mecha ...

changed criminals into heroes". Rand maintained criminality was not the important attribute of the characters; she said a criminal could serve as "an eloquent symbol" of independence and rebellion against conformity, but stated, "I do not think, nor did I think when I wrote this play, that a swindler is a heroic character or that a respectable banker is a villain". Rand biographer Ronald Merrill dismissed this explanation as a cover-up for the play's promotion of Nietzschean ideas that Rand later rejected. He called the play "a powerful and eloquent plea for the Nietzschean worldview" of the superiority of the " superman"; this is represented by Faulkner, whom Merrill interprets as rejecting external moral authority and the "slave morality

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

" of ordinary people. Biographer Anne Heller said Rand "later renounced her romantic fascination with criminals", making the characters' criminality an embarrassment for her.

Reception

Commonweal

Commonweal or common weal may refer to:

* Common good, what is shared and beneficial for members of a given community

* Common Weal, a Scottish think tank and advocacy group

* Commonweal (magazine), ''Commonweal'' (magazine), an American lay-Cath ...

'' described it as "well constructed, well enough written, admirably directed ... and excellently acted". The ''Brooklyn Daily Eagle

:''This article covers both the historical newspaper (1841–1955, 1960–1963), as well as an unrelated new Brooklyn Daily Eagle starting 1996 published currently''

The ''Brooklyn Eagle'' (originally joint name ''The Brooklyn Eagle'' and ''King ...

'' said the action came in "fits and starts", but praised the acting and the novelty of the use of a jury. ''New York Post

The ''New York Post'' (''NY Post'') is a conservative daily tabloid newspaper published in New York City. The ''Post'' also operates NYPost.com, the celebrity gossip site PageSix.com, and the entertainment site Decider.com.

It was established ...

'' critic John Mason Brown

John Mason Brown (July 3, 1900 – March 16, 1969) was an American drama critic and author.Van Gelder, Lawrence (March 17, 1969). "John Mason Brown, Critic, Dead." ''The New York Times''

Life

Born in Louisville, Kentucky, he graduated from Harv ...

said the play had some flaws, but was an exciting, above-average melodrama. Brooks Atkinson

Justin Brooks Atkinson (November 28, 1894 – January 14, 1984) was an American theatre critic. He worked for '' The New York Times'' from 1922 to 1960. In his obituary, the ''Times'' called him "the theater's most influential reviewer of hi ...

gave it a negative review in ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

'', calling it "the usual brew of hokum". A review from ''Theatre Arts Monthly

''Theatre Arts Magazine'', sometimes titled ''Theatre Arts'' or ''Theatre Arts Monthly'', was a magazine published from November 1916 to January 1964. It was established by author and critic Sheldon Warren Cheney.

History

Cheney established the ...

'' was also dismissive, calling the play a "fashionable game" that would be "fun in a parlor" but seemed "pretty foolish" on stage. Some reviews focused on Woods as the source of the play's positive attributes because he had had many previous theatrical successes. ''Time

Time is the continued sequence of existence and events that occurs in an apparently irreversible succession from the past, through the present, into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequence events, ...

'' said Woods was repeating a successful formula from ''The Trial of Mary Dugan''. Reviews that praised these elements were an embarrassment to Rand, who considered Woods' changes to be negative. Again, reviewers ignored the broader themes that Rand considered important.

Professional productions in other North American cities typically received positive reviews. Austin B. Fenger described the production at San Francisco's Geary Theater Geary, an Anglicized rendering of the Irish name ''O'Gadhra'', has a number of meanings:

__NOTOC__ Places

* Geary, New Brunswick, Canada

* Geary, Isle of Skye, Scotland, a township

* Geary, Kansas, United States, a ghost town in Doniphan County

* ...

as "darned good theater" that was "well acted" and "crisply written". Charles Collins said the Chicago production was "a first class story" that was "well acted by an admirably selected cast". Thomas Archer's review of the Montreal production described it as "realistic" and "absorbing".

The London production in 1936 received mostly positive reviews but was not a commercial success. A reviewer for ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper '' The Sunday Times'' (f ...

'' praised Foster's performance as "tense and beautiful". In ''The Daily Telegraph

''The Daily Telegraph'', known online and elsewhere as ''The Telegraph'', is a national British daily broadsheet newspaper published in London by Telegraph Media Group and distributed across the United Kingdom and internationally.

It was f ...

'', reviewer W. A. Darlington said the show would be popular with audiences, but the production ended its run in less than a month. The review in ''The Glasgow Herald

''The Herald'' is a Scottish broadsheet newspaper founded in 1783. ''The Herald'' is the longest running national newspaper in the world and is the eighth oldest daily paper in the world. The title was simplified from ''The Glasgow Herald'' in ...

'' described it as a "strong, quick thriller", but with inferior dialog to ''The Trial of Mary Dugan''. The reviewer for ''The Spectator

''The Spectator'' is a weekly British magazine on politics, culture, and current affairs. It was first published in July 1828, making it the oldest surviving weekly magazine in the world.

It is owned by Frederick Barclay, who also owns ''The ...

'' was more critical, saying the play itself was "strong", but was undermined by "mediocre playing" from "bad actors".

The 1973 revival as ''Penthouse Legend'' was a failure and received strongly negative reviews. A reviewer for ''The Village Voice

''The Village Voice'' is an American news and culture paper, known for being the country's first alternative newspaper, alternative newsweekly. Founded in 1955 by Dan Wolf (publisher), Dan Wolf, Ed Fancher, John Wilcock, and Norman Mailer, th ...

'' complimented the story's melodramatic plot twists but said it was "preposterously badly written" and described the production as "conventional and obvious". In ''The New York Times'', Clive Barnes

Clive Alexander Barnes (13 May 1927 – 19 November 2008) was an English writer and critic. From 1965 to 1977, he was the dance and theater critic for ''The New York Times'', and, from 1978 until his death, '' The New York Post.'' Barnes had sig ...

called the play tedious and said the acting was "not particularly good". It closed within a few weeks.

Academics and biographers reviewing the play have also expressed mixed opinions. Theater scholar Gerald Bordman

Gerald Martin Bordman (September 18, 1931 – May 9, 2011) was an American theatre historian, best known for authoring the reference volume ''The American Musical Theatre'', first published in 1978.Simonson, Robert (12 May 2011)Gerald Bordman, Th ...

declared it "an unexceptional courtroom drama" made popular by the jury element, although he noted praise for the acting of Breese and Pidgeon. Historian James Baker described Rand's presentation of courtroom behavior as unrealistic, but said audiences forgive this because the play's dramatic moments are "so much fun". He said the play was "great entertainment" that is "held together by an enormously attractive woman and a gimmick", but "it is not philosophy" and fails to convey the themes Rand had in mind. Jennifer Burns expressed a similar view, stating that the play's attempts to portray individualism had "dubious results ... Rand intended Bjorn Faulkner to embody heroic individualism, but in the play he comes off as little more than an unscrupulous businessman with a taste for rough sex". Literature scholar Mimi Reisel Gladstein

Mimi Reisel Gladstein (born 1936) is a professor of English and Theatre Arts at the University of Texas at El Paso. Her specialties include authors such as Ayn Rand and John Steinbeck, as well as women's studies, theatre arts and 18th-century ...

described the play as "significant for dramatic ingenuity and thematic content". Rand biographer Anne Heller considered it "engaging, if stilted", while Ronald Merrill described it as "a skillfully constructed drama" undercut by "Rand's peculiar inability to write an effective mystery plot without leaving holes". Mystery critic Marvin Lachman noted the novelty of the use of a jury but called the play unrealistic with "stilted dialogue" and "stereotypical characters".

Adaptations

Movies

The movie rights to ''Night of January 16th'' were initially purchased by

The movie rights to ''Night of January 16th'' were initially purchased by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios Inc., also known as Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Pictures and abbreviated as MGM, is an American film, television production, distribution and media company owned by Amazon through MGM Holdings, founded on April 17, 1924 ...

(MGM) in October 1934 as a possible vehicle for Loretta Young

Loretta Young (born Gretchen Young; January 6, 1913 – August 12, 2000) was an American actress. Starting as a child, she had a long and varied career in film from 1917 to 1953. She won the Academy Award for Best Actress for her role in the fil ...

. They hired Rand to write a screenplay, but the project was scrapped. After MGM's option expired, Woods considered making a movie version through a production company of his own, but in 1938 RKO Pictures bought the rights for $10,000, a fee split between Woods and Rand. RKO considered Claudette Colbert

Claudette Colbert ( ; born Émilie Claudette Chauchoin; September 13, 1903July 30, 1996) was an American actress. Colbert began her career in Broadway productions during the late 1920s and progressed to films with the advent of talking pictures ...

and Lucille Ball

Lucille Désirée Ball (August 6, 1911 – April 26, 1989) was an American actress, comedienne and producer. She was nominated for 13 Primetime Emmy Awards, winning five times, and was the recipient of several other accolades, such as the Golde ...

as possible stars, but they also gave up on the adaptation. The rights were resold to Paramount Pictures in July 1939 for $35,000. Paramount released a movie in 1941; Rand did not participate in the production. The film was directed by William Clemens, and Delmer Daves

Delmer Lawrence Daves (July 24, 1904 – August 17, 1977) was an American screenwriter, film director and film producer. He worked in many genres, including film noir and warfare, but he is best known for his Western movies, especially '' Broke ...

, Robert Pirosh

Robert Pirosh (April 1, 1910 – December 25, 1989) was an American motion picture and television screenwriter and director.

In 1951, he was nominated for another Academy Award for the screenplay '' Go for Broke!''. This was his directoria ...

, and Eve Greene

Eve Greene (May 21, 1906 – July 15, 1997) was an American screenwriter active primarily during the 1930s through the 1950s.

Biography Early life

Greene grew up in Champaign, Illinois, and dreamed of being a Hollywood writer.

Career

...

were engaged to prepare a new screenplay.

The new screenplay altered the plot significantly, focusing on Steve Van Ruyle ( Robert Preston), a sailor who inherits a position on the board of a company headed by Bjorn Faulkner (Nils Asther

Nils Anton Alfhild Asther (17 January 1897 – 19 October 1981)Swedi ...

). Unlike the play, in which Faulkner is already dead, he appears in the film as a living character who is apparently murdered. Suspicion falls on Faulkner's secretary Kit Lane (Ellen Drew

Ellen Drew (born Esther Loretta Ray; November 23, 1914 – December 3, 2003) was an American film actress.

Early life

Drew, born in Kansas City, Missouri in 1914, was the daughter of an Irish-born barber. She had a younger brother, Arden. Her ...

); Van Ruyle decides to investigate the alleged crime. Faulkner is discovered hiding in Cuba after faking his own death. Rand said only a single line from her original dialog appeared in the movie, which she dismissed as a "cheap, trashy vulgarity". The film received little attention when it was released, and most reviews of it were negative.

In 1989, '' Gawaahi'', a Hindi-language

Hindi (Devanāgarī: or , ), or more precisely Modern Standard Hindi (Devanagari: ), is an Indo-Aryan language spoken chiefly in the Hindi Belt region encompassing parts of northern, central, eastern, and western India. Hindi has been des ...

adaptation of ''Night of January 16th'' was released. Indian actress Zeenat Aman

Zeenat Khan (born 19 November 1951), better known as Zeenat Aman, is an Indian actress and former fashion model. She first received recognition for her modelling work, and at the age of 19, went on to participate in beauty pageants, winning both ...

led a cast that included Shekhar Kapur

Shekhar Kulbhushan Kapur (born 6 December 1945) is an Indian filmmaker and actor. Born into the Anand-Sahni family, Kapur is the recipient of several accolades, including a BAFTA Award, a National Film Award, a National Board of Review Award a ...

and Ashutosh Gowariker

Ashutosh Gowariker (born 15 February 1964) is an Indian film director, actor, screenwriter and producer who works in Hindi cinema. He is known for directing films "set on a huge canvas while boasting of an opulent treatment".

His is particular ...

.

Television and radio

''Night of January 16th'' was adapted for several televisionanthology series

An anthology series is a radio, television, video game or film series that spans different genres and presents a different story and a different set of characters in each different episode, season, segment, or short. These usually have a dif ...

in the 1950s and 1960s. The first was WOR-TV

WWOR-TV (channel 9) is a television station licensed to Secaucus, New Jersey, United States, serving the New York City area as the flagship of MyNetworkTV. It is owned and operated by Fox Television Stations alongside Fox flagship WNYW (ch ...

's ''Broadway Television Theatre

''Broadway Television Theatre'' is a one-hour syndicated television anthology series produced by WOR-TV in New York City. The series premiered April 14, 1952 and ran through January 25, 1954.

Overview

''Broadway Television Theatre'' featured a ne ...

'', which aired its adaptation on July 14, 1952, with a cast that included Neil Hamilton and Virginia Gilmore

Virginia Gilmore (born Sherman Virginia Poole, July 26, 1919 – March 28, 1986) was an American film, stage, and television actress.

Early years

Virginia Gilmore was born on July 26, 1919, in El Monte, California. Her father was a retired o ...

. On CBS

CBS Broadcasting Inc., commonly shortened to CBS, the abbreviation of its former legal name Columbia Broadcasting System, is an American commercial broadcast television and radio network serving as the flagship property of the CBS Entertainm ...

, the ''Lux Video Theatre

''Lux Video Theatre'' is an American television anthology series that was produced from 1950 until 1957. The series presented both comedy and drama in original teleplays, as well as abridged adaptations of films and plays.

Overview

The ''Lux Vid ...

'' presented a version of ''Night of January 16th'' on May 10, 1956, starring Phyllis Thaxter

Phyllis St. Felix Thaxter (November 20, 1919 – August 14, 2012) was an American actress. She is best known for portraying Ellen Lawson in ''Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo'' (1944) and Martha Kent in ''Superman'' (1978). She also appeared in ''Bewi ...

as Andre. In the United Kingdom, Maxine Audley

Maxine Audley (29 April 1923 – 23 July 1992) was an English theatre and film actress. She made her professional stage debut in July 1940 at the Open Air Theatre. Audley performed with the Old Vic company and the Royal Shakespeare Company many ...

took the lead role for an ''ITV Play of the Week

''Play of the Week'' is a 90-minute British television anthology series produced by a variety of companies including Granada Television, Associated-Rediffusion, ATV and Anglia Television.

Synopsis

From 1955 to 1967 approximately 500 episodes ...

'' broadcast on January 12, 1960; Cec Linder

Cecil Yekuthial Linder (March 10, 1921 – April 10, 1992) was a Polish-born Canadian film and television actor. He was Jewish and managed to escape Poland before the Holocaust. In the 1950s and 1960s, he worked extensively in the United Kingdom, ...

played the district attorney. The broadcast had been scheduled for October 6, 1959, but was delayed to avoid its possible interpretation as political commentary before the general election held later that week. A radio adaptation

Radio drama (or audio drama, audio play, radio play, radio theatre, or audio theatre) is a dramatized, purely acoustic performance. With no visual component, radio drama depends on dialogue, music and sound effects to help the listener imagine t ...

of the play was broadcast on the BBC Home Service on August 4, 1962.

See also

*''The Match King

''The Match King'' is a 1932 American Pre-Code drama film made by First National Pictures, directed by William Keighley and Howard Bretherton. The film starred Warren William and Lili Damita, and follows the rise and fall of Swedish safety mat ...

'', a movie also inspired by Ivar Kreuger

Notes

References

Works cited

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

* * * {{Ayn Rand, state=autocollapse 1934 plays Broadway plays West End plays Plays by Ayn Rand Courtroom drama plays 1930s debut plays American plays adapted into films Plays set in New York City