The New York Herald-Tribune on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The ''New York Herald Tribune'' was a newspaper published between 1924 and 1966. It was created in 1924 when

The ''New York Herald'' was founded on May 6, 1835, by James Gordon Bennett, a Scottish immigrant who came to the United States aged 24. Bennett, a firm

The ''New York Herald'' was founded on May 6, 1835, by James Gordon Bennett, a Scottish immigrant who came to the United States aged 24. Bennett, a firm

The ''

The ''

Both newspapers went into gradual decline under their new proprietors. James Gordon Bennett Jr.—"a swaggering, precociously dissolute lout who rarely stifled an impulse"—had a mercurial reign. He launched the ''

Both newspapers went into gradual decline under their new proprietors. James Gordon Bennett Jr.—"a swaggering, precociously dissolute lout who rarely stifled an impulse"—had a mercurial reign. He launched the '' Whitelaw Reid, who won control of the ''Tribune'' in part due to the likely assistance of financier

Whitelaw Reid, who won control of the ''Tribune'' in part due to the likely assistance of financier

The ''Herald'' suffered a fatal blow in 1907. Bennett, his hatred for the ''Journal'' owner unabated, attacked Hearst's campaigns for Congress in 1902, and his run for governor of New York in 1906. The ''Herald''s coverage of Hearst's gubernatorial campaign was particularly vicious, as Bennett ordered his reporters to publish every negative item about Hearst's past that they could. Hearst, seeking revenge, sent a reporter to investigate the ''Herald''s personal columns, which ran in the front of the paper and, in veiled language, advertised the service of prostitutes; reporters referred to it as "The Whores' Daily Guide and Handy Compendium." The resulting investigation, published in the ''Journal'', led to Bennett's conviction on charges of sending obscene matter through the mails. The publisher was ordered to pay a $25,000 fine—Bennett paid it in $1,000 bills—and the ''Herald'' "suffered a blow in prestige and circulation from which it never really recovered".

Whitelaw Reid died in 1912 and was succeeded as publisher by his son,

The ''Herald'' suffered a fatal blow in 1907. Bennett, his hatred for the ''Journal'' owner unabated, attacked Hearst's campaigns for Congress in 1902, and his run for governor of New York in 1906. The ''Herald''s coverage of Hearst's gubernatorial campaign was particularly vicious, as Bennett ordered his reporters to publish every negative item about Hearst's past that they could. Hearst, seeking revenge, sent a reporter to investigate the ''Herald''s personal columns, which ran in the front of the paper and, in veiled language, advertised the service of prostitutes; reporters referred to it as "The Whores' Daily Guide and Handy Compendium." The resulting investigation, published in the ''Journal'', led to Bennett's conviction on charges of sending obscene matter through the mails. The publisher was ordered to pay a $25,000 fine—Bennett paid it in $1,000 bills—and the ''Herald'' "suffered a blow in prestige and circulation from which it never really recovered".

Whitelaw Reid died in 1912 and was succeeded as publisher by his son,

The ''Herald Tribune'' began a decline shortly after World War II that had several causes. The Reid family was long accustomed to resolve shortfalls at the newspaper with subsidies from their fortune, rather than improved business practices, seeing the paper "as a hereditary possession to be sustained as a public duty rather than developed as a profit-making opportunity". With its generally marginal profitability, the ''Herald Tribune'' had few opportunities to reinvest in its operations as the ''Times'' did, and the Reids' mortgage on the newspaper made it difficult to raise outside cash for needed capital improvements.

After another profitable year in 1946, Bill Robinson, the ''Herald Tribune''s business manager, decided to reinvest the profits to make needed upgrades to the newspaper's pressroom. The investment squeezed the paper's resources, and Robinson decided to make up the difference at the end of the year by raising the ''Tribune''s price from three cents to a

The ''Herald Tribune'' began a decline shortly after World War II that had several causes. The Reid family was long accustomed to resolve shortfalls at the newspaper with subsidies from their fortune, rather than improved business practices, seeing the paper "as a hereditary possession to be sustained as a public duty rather than developed as a profit-making opportunity". With its generally marginal profitability, the ''Herald Tribune'' had few opportunities to reinvest in its operations as the ''Times'' did, and the Reids' mortgage on the newspaper made it difficult to raise outside cash for needed capital improvements.

After another profitable year in 1946, Bill Robinson, the ''Herald Tribune''s business manager, decided to reinvest the profits to make needed upgrades to the newspaper's pressroom. The investment squeezed the paper's resources, and Robinson decided to make up the difference at the end of the year by raising the ''Tribune''s price from three cents to a

"Herald Tribune Is Closing Its News Service: But Meyer Says Columns That Appeared in Paper Will Be in Merged Publication,"

''New York Times'' (June 24, 1966). merging Publishers' existing syndication operations with the New York Herald Tribune Syndicate, Field's

"The Paris Tribune at One Hundred"

''American Heritage Magazine'', November 1987. Volume 38, Issue 7. The merger became effective December 1, 1934. Subsequently the masthead carried the full New York Herald Tribune title, with the subtitle European Edition. In any case, throughout its lifetime, the European edition was often referred to as the Paris Herald Tribune, or just the Paris Herald. In the pre-World War II years the European edition was known for its feature stories. The edition looked positively on the emergence of European fascism, cheering on the Italian invasion of Ethiopia as well as the German remilitarization of the Rhineland and

Ogden Mills Reid

Ogden Mills Reid (May 16, 1882 – January 3, 1947) was an American newspaper publisher who was president of the '' New York Herald Tribune''.

Early life

Reid was born on May 16, 1882 in Manhattan. He was the son of Elisabeth ( née Mills) Reid ( ...

of the ''New-York Tribune

The ''New-York Tribune'' was an American newspaper founded in 1841 by editor Horace Greeley. It bore the moniker ''New-York Daily Tribune'' from 1842 to 1866 before returning to its original name. From the 1840s through the 1860s it was the domi ...

'' acquired the '' New York Herald''. It was regarded as a "writer's newspaper" and competed with ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

'' in the daily morning market. The paper won twelve Pulitzer Prizes

The Pulitzer Prize () is an award for achievements in newspaper, magazine, online journalism, literature, and musical composition within the United States. It was established in 1917 by provisions in the will of Joseph Pulitzer, who had made ...

during its lifetime.

A "Republican paper, a Protestant paper and a paper more representative of the suburbs than the ethnic mix of the city", according to one later reporter, the ''Tribune'' generally did not match the comprehensiveness of ''The New York Times'' coverage. Its national, international and business coverage, however, was generally viewed as among the best in the industry, as was its overall style. At one time or another, the paper's writers included Dorothy Thompson, Red Smith, Roger Kahn, Richard Watts Jr., Homer Bigart

Homer William Bigart (October 25, 1907 – April 16, 1991) was an American reporter who worked for the ''New York Herald Tribune'' from 1929 to 1955 (later known as the ''International Herald Tribune'') and for ''The New York Times'' from 1955 to ...

, Walter Kerr

Walter Francis Kerr (July 8, 1913 – October 9, 1996) was an American writer and Broadway theatre critic. He also was the writer, lyricist, and/or director of several Broadway plays and musicals as well as the author of several books, genera ...

, Walter Lippmann

Walter Lippmann (September 23, 1889 – December 14, 1974) was an American writer, reporter and political commentator. With a career spanning 60 years, he is famous for being among the first to introduce the concept of Cold War, coining the te ...

, St. Clair McKelway

St. Clair McKelway (February 13, 1905 – January 10, 1980) was a writer and editor for ''The New Yorker'' magazine beginning in 1933.

Childhood

McKelway was born in Charlotte, North Carolina, to Alexander McKelway, a Presbyterian minister, ...

, Judith Crist

Judith Crist (; May 22, 1922 – August 7, 2012) was an American film critic and academic.

She appeared regularly on the ''Today'' show from 1964 to 1973 Martin, Douglas (August 8, 2012)"Judith Crist, Zinging and Influential Film Critic, ...

, Dick Schaap

Richard Jay Schaap (September 27, 1934 – December 21, 2001) was an American sportswriter, broadcaster, and author.

Early life and education

Born to a Jewish family in Brooklyn, and raised in Freeport, New York, on Long Island, Schaap began wri ...

, Tom Wolfe

Thomas Kennerly Wolfe Jr. (March 2, 1930 – May 14, 2018)Some sources say 1931; ''The New York Times'' and Reuters both initially reported 1931 in their obituaries before changing to 1930. See and was an American author and journalist widely ...

, John Steinbeck, and Jimmy Breslin

James Earle Breslin (October 17, 1928 – March 19, 2017) was an American journalist and author. Until the time of his death, he wrote a column for the New York ''Daily News'' Sunday edition.''Current Biography 1942'', pp. 648–51: "Patterson, ...

. Editorially, the newspaper was the voice for eastern Republicans, later referred to as Rockefeller Republicans

The Rockefeller Republicans were members of the Republican Party (GOP) in the 1930s–1970s who held moderate-to-liberal views on domestic issues, similar to those of Nelson Rockefeller, Governor of New York (1959–1973) and Vice President ...

, and espoused a pro-business, internationalist viewpoint.

The paper, first owned by the Reid family, struggled financially for most of its life and rarely generated enough profit for growth or capital improvements; the Reids subsidized the ''Herald Tribune'' through the paper's early years. However, it enjoyed prosperity during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

and by the end of the conflict had pulled close to the ''Times'' in ad revenue. A series of disastrous business decisions, combined with aggressive competition from the ''Times'' and poor leadership from the Reid family, left the ''Herald Tribune'' far behind its rival.

In 1958, the Reids sold the ''Herald Tribune'' to John Hay Whitney

John Hay Whitney (August 17, 1904 – February 8, 1982) was U.S. Ambassador to the United Kingdom, publisher of the '' New York Herald Tribune'', and president of the Museum of Modern Art. He was a member of the Whitney family.

Early life

Whi ...

, a multimillionaire Wall Street investor who was serving as ambassador to the United Kingdom at the time. Under his leadership, the ''Tribune'' experimented with new layouts and new approaches to reporting the news and made important contributions to the body of New Journalism

New Journalism is a style of news writing and journalism, developed in the 1960s and 1970s, that uses literary techniques unconventional at the time. It is characterized by a subjective perspective, a literary style reminiscent of long-form non- ...

that developed in the 1960s. The paper steadily revived under Whitney, but a 114-day newspaper strike stopped the ''Herald Tribune''s gains and ushered in four years of strife with labor unions, particularly the local chapter of the International Typographical Union

The International Typographical Union (ITU) was a US trade union for the printing trade for newspapers and other media. It was founded on May 3, 1852, in the United States as the National Typographical Union, and changed its name to the Interna ...

. Faced with mounting losses, Whitney attempted to merge the ''Herald Tribune'' with the ''New York World-Telegram

The ''New York World-Telegram'', later known as the ''New York World-Telegram and The Sun'', was a New York City newspaper from 1931 to 1966.

History

Founded by James Gordon Bennett Sr. as ''The Evening Telegram'' in 1867, the newspaper began ...

'' and the '' New York Journal-American'' in the spring of 1966; the proposed merger led to another lengthy strike, and on August 15, 1966, Whitney announced the closure of the ''Herald Tribune''. Combined with investments in the ''World Journal Tribune

The ''New York World Journal Tribune'' (''WJT'', and hence the nickname ''The Widget'') was an evening daily newspaper published in New York City from September 1966 until May 1967. The ''World Journal Tribune'' represented an attempt to save th ...

'', Whitney spent $39.5 million (equivalent to $ in dollars) in his attempts to keep the newspaper alive.

After the ''New York Herald Tribune'' closed, the ''Times'' and ''The Washington Post

''The Washington Post'' (also known as the ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'') is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C. It is the most widely circulated newspaper within the Washington metropolitan area and has a large nati ...

'', joined by Whitney, entered an agreement to operate the '' International Herald Tribune'', the paper's former Paris publication. By 1967, the paper was owned jointly by Whitney Communications, ''The Washington Post

''The Washington Post'' (also known as the ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'') is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C. It is the most widely circulated newspaper within the Washington metropolitan area and has a large nati ...

'' and ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

''. The ''International Herald Tribune'', also known as the "IHT", ceased publication in 2013.

Origins: 1835–1924

''New York Herald''

The ''New York Herald'' was founded on May 6, 1835, by James Gordon Bennett, a Scottish immigrant who came to the United States aged 24. Bennett, a firm

The ''New York Herald'' was founded on May 6, 1835, by James Gordon Bennett, a Scottish immigrant who came to the United States aged 24. Bennett, a firm Democrat

Democrat, Democrats, or Democratic may refer to:

Politics

*A proponent of democracy, or democratic government; a form of government involving rule by the people.

*A member of a Democratic Party:

**Democratic Party (United States) (D)

**Democratic ...

, had established a name in the newspaper business in the 1820s with dispatches sent from Washington, D.C., to the New York ''Enquirer'', most sharply critical of President John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, and diarist who served as the sixth president of the United States, from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States ...

and Secretary of State Henry Clay; one historian called Bennett "the first real Washington reporter". Bennett was also a pioneer in crime reporting; while writing about a murder trial in 1830, the attorney general of Massachusetts attempted to restrict the coverage of the newspapers: Bennett criticized the move as an "old, worm-eaten, Gothic dogma of the Court...to consider the publicity given to every event by the Press, as destructive to the interests of law and justice". The fight over access eventually overshadowed the trial itself.

Bennett founded the ''New York Globe'' in 1832 to promote the re-election of Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

to the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in ...

, but the paper quickly folded after the election. After a few years of journalistic piecework, he founded the ''Herald'' in 1835 as a penny newspaper, similar in some respects to Benjamin Day's ''Sun

The Sun is the star at the center of the Solar System. It is a nearly perfect ball of hot plasma, heated to incandescence by nuclear fusion reactions in its core. The Sun radiates this energy mainly as light, ultraviolet, and infrared radi ...

'' but with a strong emphasis on crime and financial coverage; the ''Herald'' "carried the most authentic and thorough list of market prices published anywhere; for these alone it commanded attention in financial circles". Bennett, who wrote much of the newspaper himself, "perfected the fresh, pointed prose practiced in the French press at its best". The publisher's coverage of the 1836 murder of Helen Jewett

Helen Jewett (born Dorcas Doyen;The trial of Richard P. Robinson for the murder of Helen Jewett. New York City, 1836 In American state trials / John D.Lawson, editor pp 426-487 Wilmington, Del. : Scholarly Resources, 1972 October 18, 1813 – Ap ...

—which, for the first time in the American press, included excerpts from the murder victim's correspondence—made Bennett "the best known, if most notorious…journalist in the country".

Bennett put his profits back into his newspaper, establishing a Washington bureau and recruiting correspondents in Europe to provide the "first systematic foreign coverage" in an American newspaper. By 1839, the ''Herald''s circulation exceeded that of '' The London Times''. When the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the 1 ...

broke out in 1846, the ''Herald'' assigned a reporter to the conflict—the only newspaper in New York to do so—and used the telegraph

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas p ...

, then a new technology, to not only beat competitors with news but provide Washington policymakers with the first reports from the conflict. During the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

, Bennett kept at least 24 correspondents in the field, opened a Southern desk and had reporters comb the hospitals to develop lists of casualties and deliver messages from the wounded to their families.

''New-York Tribune''

The ''

The ''New-York Tribune

The ''New-York Tribune'' was an American newspaper founded in 1841 by editor Horace Greeley. It bore the moniker ''New-York Daily Tribune'' from 1842 to 1866 before returning to its original name. From the 1840s through the 1860s it was the domi ...

'' was founded by Horace Greeley in 1841. Greeley, a native of New Hampshire

New Hampshire is a state in the New England region of the northeastern United States. It is bordered by Massachusetts to the south, Vermont to the west, Maine and the Gulf of Maine to the east, and the Canadian province of Quebec to the nor ...

, had begun publishing a weekly paper called ''The New-Yorker'' (unrelated to the magazine of the same name) in 1834, which won attention for its political reporting and editorials. Joining the Whig Party, Greeley published ''The Jeffersonian'', which helped elect William H. Seward

William Henry Seward (May 16, 1801 – October 10, 1872) was an American politician who served as United States Secretary of State from 1861 to 1869, and earlier served as governor of New York and as a United States Senator. A determined oppon ...

Governor of New York State

New York, officially the State of New York, is a state in the Northeastern United States. It is often called New York State to distinguish it from its largest city, New York City. With a total area of , New York is the 27th-largest U.S. stat ...

in 1838, and then the ''Log Cabin'', which advocated for the election of William Henry Harrison

William Henry Harrison (February 9, 1773April 4, 1841) was an American military officer and politician who served as the ninth president of the United States. Harrison died just 31 days after his inauguration in 1841, and had the shortest pres ...

in the 1840 presidential election, attained a circulation of 80,000 and turned a small profit.

With Whigs in power, Greeley saw the opportunity to launch a daily penny newspaper for their constituency. The ''New York Tribune'' launched on April 10, 1841. Unlike the ''Herald'' or the ''Sun'', it generally shied about from graphic crime coverage; Greeley saw his newspaper as having a moral mission to uplift society, and frequently focused his energies on the newspaper's editorials—"weapons…in a ceaseless war to improve society"—and political coverage. While a lifelong opponent of slavery and, for time, a proponent of socialism

Socialism is a left-wing Economic ideology, economic philosophy and Political movement, movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to Private prop ...

, Greeley's attitudes were never exactly fixed: "The result was a potpourri of philosophical inconsistencies and contradictions that undermined Greeley's effectiveness as both logician and polemicist." However, his moralism appealed to rural America; with six months of beginning the ''Tribune'', Greeley combined ''The New-Yorker'' and ''The Log Cabin'' into a new publication, the ''Weekly Tribune''. The weekly version circulated nationwide, serving as a digest of news melded with agriculture tips. Offering prizes like strawberry plants and gold pens to salesmen, the ''Weekly Tribune'' reached a circulation of 50,000 within 10 years, outpacing the ''Herald''s weekly edition.

The Tribune's ranks included Henry Raymond, who later founded ''The New York Times'', and Charles Dana, who would later edit and partly own ''The Sun'' for nearly three decades. Dana served as second-in-command to Greeley, but Greeley abruptly fired him in 1862, after years of personality conflicts between the two men. Raymond, who felt he was "overused and underpaid" as a reporter on the Tribune staff, later served in the New York State Assembly and, with the backing of bankers in Albany, founded the ''Times'' in 1851, which quickly became a rival for the Whig readership that Greeley cultivated.

After the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

, Bennett turned over daily operations of the ''Herald'' to his son James Gordon Bennett Jr.

James Gordon Bennett Jr. (May 10, 1841May 14, 1918) was publisher of the ''New York Herald'', founded by his father, James Gordon Bennett Sr. (1795–1872), who emigrated from Scotland. He was generally known as Gordon Bennett to distinguish him ...

, and lived in seclusion until his death in 1872. That year, Greeley, who had been an early supporter of the Republican Party, had called for reconciliation of North and South following the war and criticized Radical Reconstruction

The Reconstruction era was a period in American history following the American Civil War (1861–1865) and lasting until approximately the Compromise of 1877. During Reconstruction, attempts were made to rebuild the country after the bloo ...

. Gradually becoming disenchanted with Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

, Greeley became the surprise nominee of the Liberal Republican faction of the party (and the Democrats) in the 1872 presidential election. The editor had left daily operations of the ''Tribune'' to his protege, Whitelaw Reid

Whitelaw Reid (October 27, 1837 – December 15, 1912) was an American politician and newspaper editor, as well as the author of ''Ohio in the War'', a popular work of history.

After assisting Horace Greeley as editor of the ''New-York Tribu ...

; he attempted to resume his job after the election, but was badly hurt by a piece (intended humorously) that said Greeley's defeat would chase political office seekers from the ''Tribune'' and allow the staff to "manage our own newspaper without being called aside every hour to help lazy people whom we don't know and…benefit people who don't deserve assistance". The piece was widely (and incorrectly) attributed to Greeley as a sign of bitterness at the outcome; Reid refused to print Greeley's furious disclaimer of the story, and by the end of the month, Greeley had died.

Decline under second generation

Both newspapers went into gradual decline under their new proprietors. James Gordon Bennett Jr.—"a swaggering, precociously dissolute lout who rarely stifled an impulse"—had a mercurial reign. He launched the ''

Both newspapers went into gradual decline under their new proprietors. James Gordon Bennett Jr.—"a swaggering, precociously dissolute lout who rarely stifled an impulse"—had a mercurial reign. He launched the ''New York Telegram

The ''New York World-Telegram'', later known as the ''New York World-Telegram and The Sun'', was a New York City newspaper from 1931 to 1966.

History

Founded by James Gordon Bennett Sr. as ''The Evening Telegram'' in 1867, the newspaper began ...

'', an evening paper, in the late 1860s and kept the ''Herald'' the most comprehensive source of news among the city's newspapers. Bennett also bankrolled Henry Morton Stanley's trek through Africa to find David Livingstone

David Livingstone (; 19 March 1813 – 1 May 1873) was a Scottish physician, Congregationalist, and pioneer Christian missionary with the London Missionary Society, an explorer in Africa, and one of the most popular British heroes of t ...

, and scooped the competition on the Battle of Little Big Horn

The Battle of the Little Bighorn, known to the Lakota and other Plains Indians as the Battle of the Greasy Grass, and also commonly referred to as Custer's Last Stand, was an armed engagement between combined forces of the Lakota Sioux, Nor ...

. However, Bennett ruled his paper with a heavy hand, telling his executives at one point that he was the "only reader of this paper": "I am the only one to be pleased. If I want it turned upside down, it must be turned upside down. I want one feature article a day. If I say the feature is black beetles, black beetles it's going to be." In 1874, the ''Herald'' ran the infamous New York Zoo hoax, where the front page of the newspaper was devoted entirely to a fabricated story of animals getting loose at the Central Park Zoo.

Whitelaw Reid, who won control of the ''Tribune'' in part due to the likely assistance of financier

Whitelaw Reid, who won control of the ''Tribune'' in part due to the likely assistance of financier Jay Gould

Jason Gould (; May 27, 1836 – December 2, 1892) was an American railroad magnate and financial speculator who is generally identified as one of the robber barons of the Gilded Age. His sharp and often unscrupulous business practices made him ...

, turned the newspaper into an orthodox Republican organ, wearing "its stubborn editorial and typographical conservatism…as a badge of honor". Reid's hostility to labor led him to bankroll Ottmar Mergenthaler

Ottmar Mergenthaler (11 May 1854 – 28 October 1899) was a German-American inventor who has been called a second Gutenberg, as Mergenthaler invented the linotype machine, the first device that could easily and quickly set complete lines of ...

's development of the linotype machine

The Linotype machine ( ) is a "line casting" machine used in printing; manufactured and sold by the former Mergenthaler Linotype Company and related It was a hot metal typesetting system that cast lines of metal type for individual uses. Lin ...

in 1886, which quickly spread throughout the industry. However, his day-to-day involvement in the operations of the ''Tribune'' declined after 1888, when he was appointed Minister to France and largely focused on his political career; Reid even missed a large-scale 50th anniversary party for the ''Tribune'' in 1891. Despite this, the paper remained profitable due to an educated and wealthy readership that attracted advertisers.

The ''Herald'' was the largest circulation newspaper in New York City until 1884. Joseph Pulitzer

Joseph Pulitzer ( ; born Pulitzer József, ; April 10, 1847 – October 29, 1911) was a Hungarian-American politician and newspaper publisher of the '' St. Louis Post-Dispatch'' and the ''New York World''. He became a leading national figure in ...

, who came from St. Louis and purchased the ''New York World

The ''New York World'' was a newspaper published in New York City from 1860 until 1931. The paper played a major role in the history of American newspapers. It was a leading national voice of the Democratic Party. From 1883 to 1911 under pub ...

'' in 1882, aggressively marketed a mix of crime stories and social reform editorials to a predominantly immigrant audience, and saw his circulation quickly surpass those of more established publishers. Bennett, who had moved permanently to Paris in 1877 after publicly urinating in the fireplace or piano of his fiancée's parents (the exact location differed in witnesses' memories) spent the ''Herald''s still sizable profits on his own lifestyle, and the Herald's circulation stagnated. Bennett respected Pulitzer, and even ran an editorial praising the publisher of ''The World'' after health problems forced him to relinquish the editorship of the paper in 1890. However, he despised William Randolph Hearst

William Randolph Hearst Sr. (; April 29, 1863 – August 14, 1951) was an American businessman, newspaper publisher, and politician known for developing the nation's largest newspaper chain and media company, Hearst Communications. His flamboya ...

, who purchased the ''New York Journal

:''Includes coverage of New York Journal-American and its predecessors New York Journal, The Journal, New York American and New York Evening Journal''

The ''New York Journal-American'' was a daily newspaper published in New York City from 1937 t ...

'' in 1895 and attempted to ape Pulitzer's methods in a more sensationalistic manner. The challenge of ''The World'' and the ''Journal'' spurred Bennett to revitalize the paper; the ''Herald'' competed keenly with both papers during coverage of the Spanish–American War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (cloc ...

, providing "the soundest, fairest coverage…(of) any American newspaper", sending circulation over 500,000.

The ''Tribune'' largely relied on wire copy for its coverage of the conflict. Reid, who helped negotiate the treaty that ended the war had by 1901 become completely disengaged from the ''Tribune''s daily operations. The paper was no longer profitable, and the Reids largely viewed the paper as a "private charity case". By 1908, the ''Tribune'' was losing $2,000 a week. In an article about New York City's daily newspapers that year, ''The Atlantic Monthly

''The Atlantic'' is an American magazine and multi-platform publisher. It features articles in the fields of politics, foreign affairs, business and the economy, culture and the arts, technology, and science.

It was founded in 1857 in Boston, ...

'' found the newspaper's "financial pages … execrable, its news columns readable but utterly commonplace, and its rubber-stamping of Republican policies (making) it the last sheet in town operated as a servant of party machinery".

The ''Herald'' also saw its reputation for comprehensiveness challenged by the ''Times'', purchased by ''Chattanooga Times

The ''Chattanooga Times Free Press'' is a daily broadsheet newspaper published in Chattanooga, Tennessee, and is distributed in the metropolitan Chattanooga region of southeastern Tennessee and northwestern Georgia. It is one of Tennessee's maj ...

'' publisher Adolph Ochs in 1896, a few weeks before the paper would have likely closed its doors. Ochs, turning the once-Republican ''Times'' into an independent Democratic newspaper, refocused the newspaper's coverage on commerce, quickly developing a reputation as the "businessman's bible". When the ''Times'' began turning a profit in 1899, Ochs began reinvesting the profits make into the newspaper toward news coverage, quickly giving the ''Times'' the reputation as the most complete newspaper in the city. Bennett, who viewed the ''Herald'' as a means of supporting his lifestyle, did not make serious moves to expand the newspaper's newsgathering operations, and allowed the paper's circulation to fall well below 100,000 by 1912.

Revival of the ''Tribune'', fall of the ''Herald''

The ''Herald'' suffered a fatal blow in 1907. Bennett, his hatred for the ''Journal'' owner unabated, attacked Hearst's campaigns for Congress in 1902, and his run for governor of New York in 1906. The ''Herald''s coverage of Hearst's gubernatorial campaign was particularly vicious, as Bennett ordered his reporters to publish every negative item about Hearst's past that they could. Hearst, seeking revenge, sent a reporter to investigate the ''Herald''s personal columns, which ran in the front of the paper and, in veiled language, advertised the service of prostitutes; reporters referred to it as "The Whores' Daily Guide and Handy Compendium." The resulting investigation, published in the ''Journal'', led to Bennett's conviction on charges of sending obscene matter through the mails. The publisher was ordered to pay a $25,000 fine—Bennett paid it in $1,000 bills—and the ''Herald'' "suffered a blow in prestige and circulation from which it never really recovered".

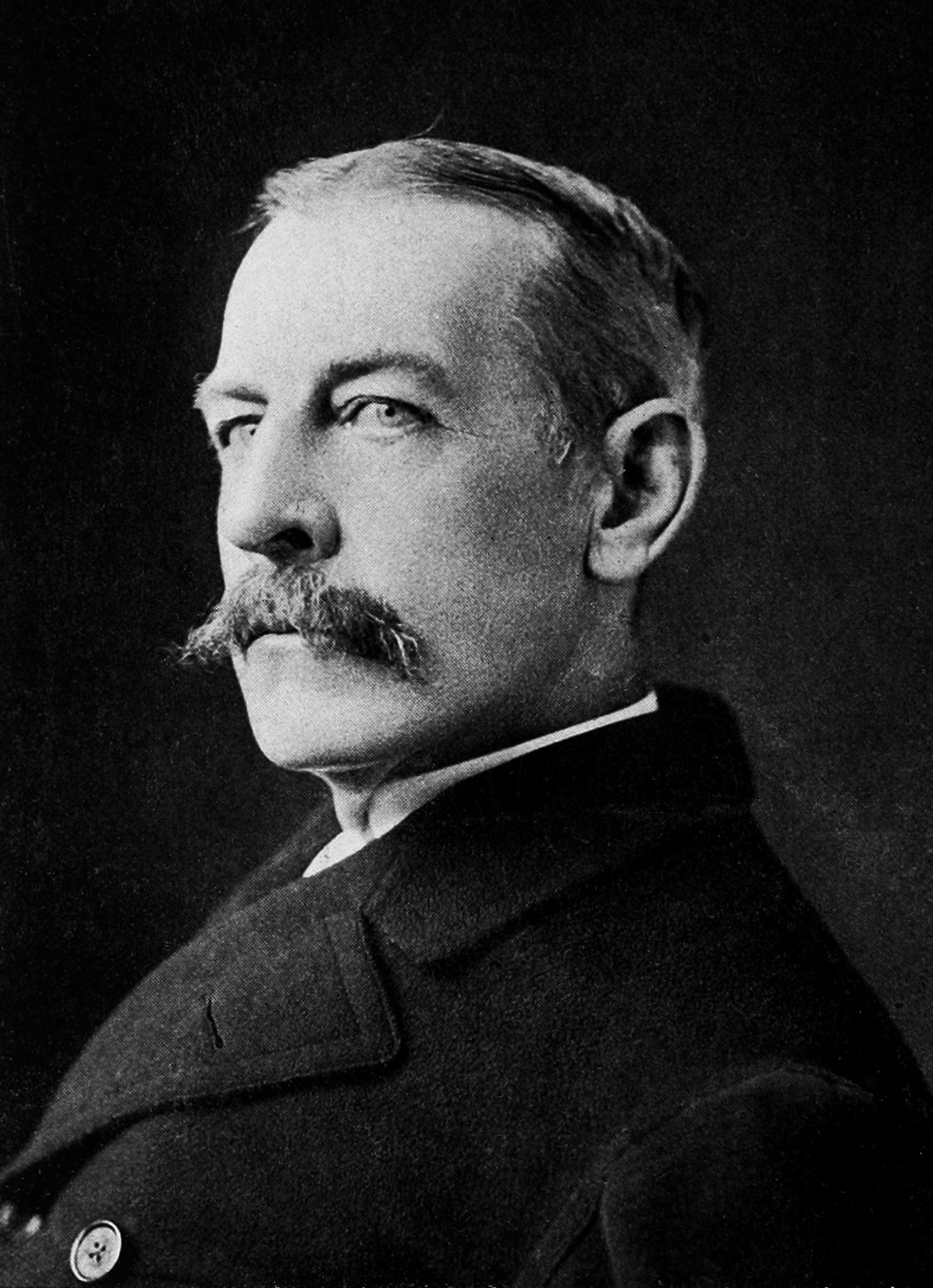

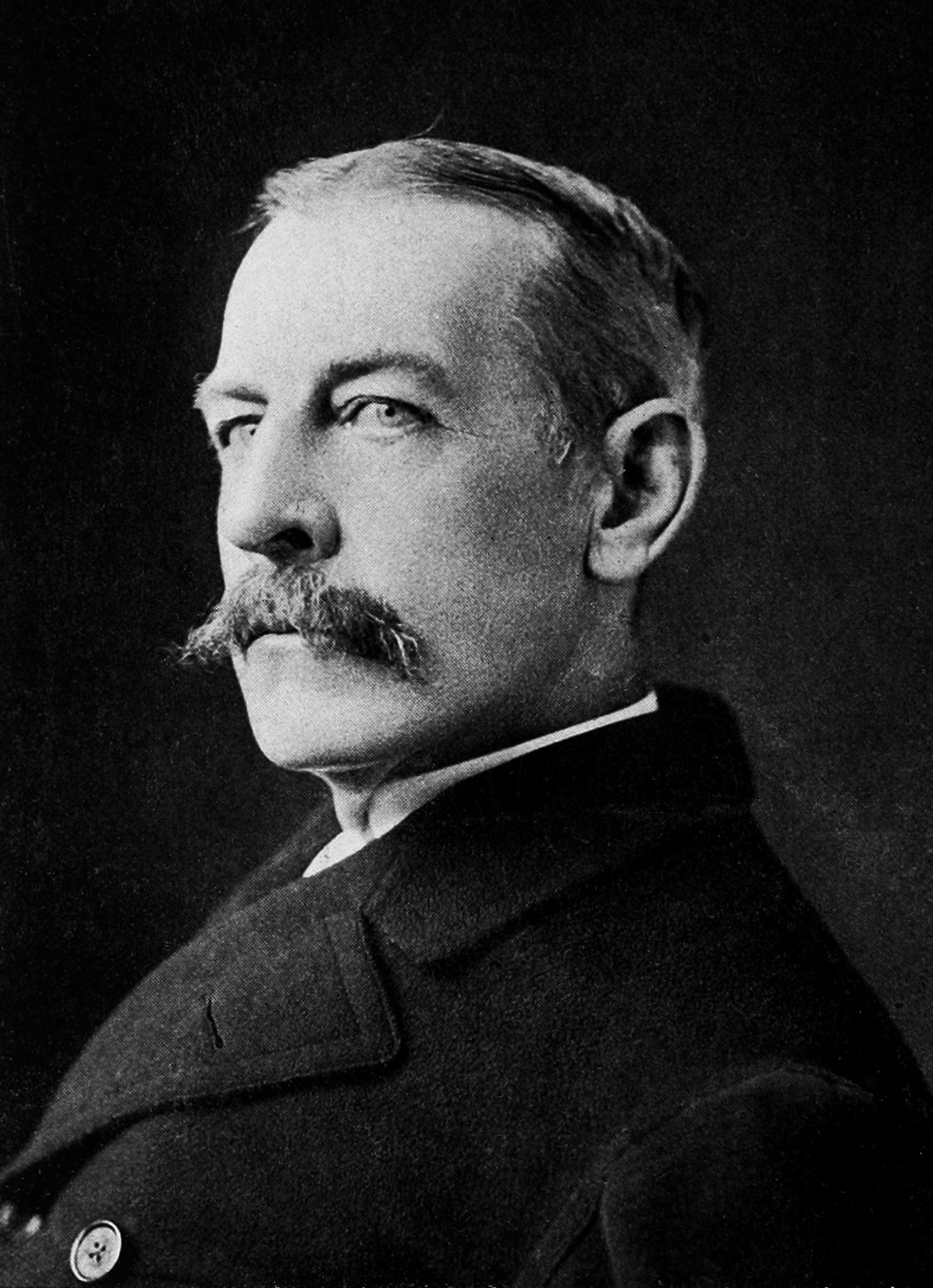

Whitelaw Reid died in 1912 and was succeeded as publisher by his son,

The ''Herald'' suffered a fatal blow in 1907. Bennett, his hatred for the ''Journal'' owner unabated, attacked Hearst's campaigns for Congress in 1902, and his run for governor of New York in 1906. The ''Herald''s coverage of Hearst's gubernatorial campaign was particularly vicious, as Bennett ordered his reporters to publish every negative item about Hearst's past that they could. Hearst, seeking revenge, sent a reporter to investigate the ''Herald''s personal columns, which ran in the front of the paper and, in veiled language, advertised the service of prostitutes; reporters referred to it as "The Whores' Daily Guide and Handy Compendium." The resulting investigation, published in the ''Journal'', led to Bennett's conviction on charges of sending obscene matter through the mails. The publisher was ordered to pay a $25,000 fine—Bennett paid it in $1,000 bills—and the ''Herald'' "suffered a blow in prestige and circulation from which it never really recovered".

Whitelaw Reid died in 1912 and was succeeded as publisher by his son, Ogden Mills Reid

Ogden Mills Reid (May 16, 1882 – January 3, 1947) was an American newspaper publisher who was president of the '' New York Herald Tribune''.

Early life

Reid was born on May 16, 1882 in Manhattan. He was the son of Elisabeth ( née Mills) Reid ( ...

. The younger Reid, an "affable but lackluster person," began working at the ''Tribune'' in 1908 as a reporter and won the loyalty of the staff with his good nature and eagerness to learn. Quickly moved through the ranks—he became managing editor in 1912—Reid oversaw the ''Tribune''s thorough coverage of the sinking of the ''Titanic

RMS ''Titanic'' was a British passenger liner, operated by the White Star Line, which sank in the North Atlantic Ocean on 15 April 1912 after striking an iceberg during her maiden voyage from Southampton, England, to New York City, Unit ...

'', ushering a revival of the newspaper's fortunes. While the paper continued to lose money, and was saved from bankruptcy only by the generosity of Elisabeth Mills Reid, Ogden's mother., the younger Reid encouraged light touches at the previously somber ''Tribune'', creating an environment where "the windows were opened and the suffocating solemnity of the place was aired out". Under Reid's tenure the ''Tribune'' lobbied for legal protection for journalists culminating in the U.S. Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

case Burdick v. United States. In 1917, the ''Tribune'' redesigned its layout and became the first American newspaper to use the Bodoni

Bodoni is the name given to the serif typefaces first designed by Giambattista Bodoni (1740–1813) in the late eighteenth century and frequently revived since. Bodoni's typefaces are classified as Didone or modern. Bodoni followed the ideas o ...

font for headlines. The font gave a "decided elegance" to the ''Tribune'' and was soon adopted by magazines and other newspapers, including ''The Washington Post

''The Washington Post'' (also known as the ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'') is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C. It is the most widely circulated newspaper within the Washington metropolitan area and has a large nati ...

'', ''The Boston Globe

''The Boston Globe'' is an American daily newspaper founded and based in Boston, Massachusetts. The newspaper has won a total of 27 Pulitzer Prizes, and has a total circulation of close to 300,000 print and digital subscribers. ''The Boston Glob ...

'' and the '' Miami Herald.'' The ''Tribune'' developed a reputation for typographical excellence it would maintain for more than four decades. Reid, who inherited a newspaper whose circulation may have fallen to 25,000 daily—no higher than the circulation in 1872—saw the ''Tribune's'' readership jump to about 130,000 by 1924.

Reid's wife, Helen Rogers Reid

Helen Miles Rogers Reid (November 23, 1882 – July 27, 1970) was an American newspaper publisher. She was president of the ''New York Herald Tribune''.

Early life

Reid was born Helen Miles Rogers in Appleton, Wisconsin on November 23, 1882. ...

, took charge of the newspaper's advertising department in 1919. Helen Reid, "who believed in the newspaper the way a religious person believes in God", reorganized the faltering department, aggressively pursuing advertisers and selling them on the "wealth, position and power" of the ''Tribune''s readership. In her first two years on the job, the ''Tribune''s annual advertising revenues jumped from $1.7 million to $4.3 million, "with circulation responsible for no more than 10 percent of the increase". Reid's efforts helped cut the newspaper's dependence on subsidies from the family fortune and pushed it toward a paying track. Reid also encouraged the development of women's features at the newspaper, the hiring of female writers, and helped establish a "home institute" that tested recipes and household products.

The ''Herald''s decline continued in the new decade. With the outbreak of World War I, Bennett devoted most of his attention to the ''Paris Herald'', doing his first newspaper reporting at the age of 73 and keeping the publication alive despite wartime censorship. The New York paper, however, was in freefall, and posted a loss in 1917. The next year, Bennett died, having taken some $30 million out of the lifetime profits of the ''Herald''. Two years later, the ''Herald'' newspapers were sold to Frank Munsey for $3 million.

Munsey had won the enmity of many journalists with his buying, selling and consolidation of newspapers, and the ''Herald'' became part of Munsey's moves. The publisher merged the morning ''Sun'' (which he had purchased in 1916) into the ''Herald'' and attempted to revive the newspaper through his financial resources, hoping to establish the ''Herald'' as the pre-eminent Republican newspaper within the city. To achieve that end, he approached Elisabeth Mills Reid in early 1924 with a proposal to purchase the ''Tribune''—the only other Republican newspaper in New York—and merge it with the ''Herald''. The elder Reid refused to sell, saying only that she would buy the ''Herald''. The two sides negotiated through the winter and spring. Munsey approached Ogden Reid with a proposal to swap the profitable evening ''Sun'' with the ''Tribune'', which Reid refused. The Reids countered with an offer of $5 million for the ''Herald'' and the ''Paris Herald'', which Munsey agreed to on March 17, 1924.

The move surprised the journalism community, which had expected Munsey to purchase the ''Tribune''. The ''Herald'' management informed its staff of the sale in a brief note posted on a bulletin board; reading it, one reporter remarked "Jonah just swallowed the whale".

The merged paper, which published its first edition on March 19, was named the ''New York Herald New York Tribune'' until May 31, 1926, when the more familiar ''New York Herald Tribune'' was substituted. Apart from the ''Herald''s radio magazine, weather listings and other features, "the merged paper was, with very few changes, the ''Tribune'' intact". Only 25 ''Herald'' reporters were hired after the merger; 600 people lost their jobs. Within a year, the new paper's circulation reached 275,000.

''New York Herald Tribune:'' 1924–1946

1924–1940: Social journalism and mainstream Republicanism

The newly merged paper was not immediately profitable, but Helen Reid's reorganization of the business side of the paper, combined with an increasing reputation as a "newspaperman's newspaper", led the ''Herald Tribune'' to post a profit of nearly $1.5 million in 1929, as circulation climbed over the 300,000 mark. The onset of the Great Depression, however, wiped out the profits. In 1931, the ''Herald Tribune'' lost $650,000 (equivalent to approximately $ in dollars), and the Reid family was once again forced to subsidize the newspaper. By 1933, the ''Herald Tribune'' turned a profit of $300,000, and would stay in the black for the next 20 years, without ever making enough money for significant growth or reinvestment. Through the 1930s Ogden Reid often stayed late at Bleeck's, a popular hangout for ''Herald Tribune'' reporters.; by 1945, ''Tribune'' historian Richard Kluger wrote, Reid was struggling withalcoholism

Alcoholism is, broadly, any drinking of alcohol that results in significant mental or physical health problems. Because there is disagreement on the definition of the word ''alcoholism'', it is not a recognized diagnostic entity. Predomi ...

. The staff considered the ''Herald Tribune''s owner "kindly and likable, if deficient in intelligence and enterprise". Helen Reid increasingly took on the major leadership responsibilities at the newspaper—a fact ''Time

Time is the continued sequence of existence and events that occurs in an apparently irreversible succession from the past, through the present, into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequence events, ...

'' noted in a 1934 cover story. Reid, angered, called her husband "the most independent-minded man I have ever met", to which ''Time'' replied that "it is Mrs. Reid who often helps that independent mind make itself up".

Editorially, the newspaper thrived, winning its first Pulitzer Prize for reporting in 1930 for Leland Stowe Leland Stowe (November 10, 1899 – January 16, 1994) was a Pulitzer Prize winning American journalist noted for being one of the first to recognize the expansionist character of the German Nazi regime.

Biography

Stowe was born in Southbury, Conn ...

's coverage of the Second Reparations Conference on German reparations for World War I, where the Young Plan

The Young Plan was a program for settling Germany's World War I reparations. It was written in August 1929 and formally adopted in 1930. It was presented by the committee headed (1929–30) by American industrialist Owen D. Young, founder and for ...

was developed. Stanley Walker, who became the newspaper's city editor in 1928, pushed his staff (which briefly included Joseph Mitchell) to write in a clear, lively style, and pushed the ''Herald Tribune''s local coverage "to a new kind of social journalism that aimed at capturing the temper and feel of the city, its moods and fancies, changes or premonitions of change in its manners, customs, taste, and thought—daily helpings of what amounted to urban anthropology". The ''Herald Tribune''s editorials remained conservative—"a spokesman for and guardian of mainstream Republicanism"—but the newspaper also hired columnist Walter Lippmann

Walter Lippmann (September 23, 1889 – December 14, 1974) was an American writer, reporter and political commentator. With a career spanning 60 years, he is famous for being among the first to introduce the concept of Cold War, coining the te ...

, seen at the time as a liberal, after ''The World'' closed its doors in 1931. Unlike other pro-Republican papers, such as Hearst's '' New York Journal-American'' or the ''Chicago Tribune

The ''Chicago Tribune'' is a daily newspaper based in Chicago, Illinois, United States, owned by Tribune Publishing. Founded in 1847, and formerly self-styled as the "World's Greatest Newspaper" (a slogan for which WGN radio and television a ...

''-owned '' New York Daily News'', which held an isolationist and pro-German stance, the ''Herald Tribune'' was more supportive of the British and the French as the specter of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

developed, a similar stance was approached by the ''Sun'' and the ''World-Telegram'', the latter of them also having an ardently liberal past as a Pulitzer newspaper.

Financially, the paper continued to stay out of the red, but long-term trouble was on the horizon. After Elisabeth Mills Reid died in 1931—after having given the paper $15 million over her lifetime—it was discovered that the elder Reid had treated the subsidies as loans, not capital investments. The notes on the paper were willed to Ogden Reid and his sister, Lady Jean Templeton Reid Ward. The notes amounted to a mortgage

A mortgage loan or simply mortgage (), in civil law jurisdicions known also as a hypothec loan, is a loan used either by purchasers of real property to raise funds to buy real estate, or by existing property owners to raise funds for any ...

on the ''Herald Tribune'', which prevented the newspaper from acquiring bank loans or securing public financing. Financial advisors at the newspaper advised the Reids to convert the notes into equity, which the family resisted. This decision would play a major role in the Reids' sale of the ''Herald Tribune'' in 1958.

Seeking to cut costs during the Recession of 1937, the newspaper's management decided to consolidate its foreign coverage under Laurence Hills, who had been appointed editor of the ''Paris Herald'' by Frank Munsey in 1920 and kept the paper profitable. But Hills had fascist sympathies—the ''Paris Herald'' was alone among American newspapers in having "ad columns sprout(ing) with swastikas and '' fasces''—and was more interested in cutting costs than producing journalism. "It is no longer the desire even to attempt to run parallel with ''The New York Times'' in special dispatches from Europe," Hills wrote in a memo to the ''Herald Tribune''s foreign bureaus in late 1937. "Crisp cables of human interest or humorous type cables are greatly appreciated. Big beats in Europe these days are not very likely." The policy effectively led the ''Herald Tribune'' to surrender the edge in foreign reporting to its rival.

The ''Herald Tribune'' strongly supported Wendell Willkie

Wendell Lewis Willkie (born Lewis Wendell Willkie; February 18, 1892 – October 8, 1944) was an American lawyer, corporate executive and the 1940 Republican nominee for President. Willkie appealed to many convention delegates as the Republican ...

for the Republican nomination in the 1940 presidential election; Willkie's managers made sure the newspaper's endorsement was placed in each delegate's seat at the 1940 Republican National Convention

The 1940 Republican National Convention was held in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, from June 24 to June 28, 1940. It nominated Wendell Willkie of New York for president and Senator Charles McNary of Oregon for vice president.

The contest for the ...

. The ''Herald Tribune'' continued to provide a strong voice for Willkie (who was having an affair with literary editor Irita Van Doren) through the election. Dorothy Thompson, then a columnist at the paper, openly supported Franklin Roosevelt's re-election and was eventually forced to resign.

World War II

Historians of ''The New York Times''—includingGay Talese

Gaetano "Gay" Talese (; born February 7, 1932) is an American writer. As a journalist for ''The New York Times'' and ''Esquire'' magazine during the 1960s, Talese helped to define contemporary literary journalism and is considered, along with ...

, Susan Tifft and Alex S. Jones—have argued that the ''Times'', faced with newsprint rationing during World War II, decided to increase its news coverage at the expense of its advertising, while the ''Herald Tribune'' chose to run more ads, trading short-term profit for long-term difficulties. In '' The Kingdom and the Power'', Talese's 1969 book about the ''Times'', Talese wrote "the additional space that ''The Times'' was able to devote to war coverage instead of advertising was, in the long run, a very profitable decision: ''The Times'' lured many readers away from the ''Tribune'', and these readers stayed with ''The Times'' after the war into the Nineteen-fifties and Sixties". Although ''The New York Times'' had the most comprehensive coverage of any American newspaper—the newspaper put 55 correspondents in the field, including drama critic Brooks Atkinson

Justin Brooks Atkinson (November 28, 1894 – January 14, 1984) was an American theatre critic. He worked for '' The New York Times'' from 1922 to 1960. In his obituary, the ''Times'' called him "the theater's most influential reviewer of hi ...

—its news budget fell from $3.8 million in 1940 to $3.7 million in 1944; the paper did not significantly expand its number of newsroom employees between 1937 and 1945 and its ad space, far from declining, actually increased during the conflict and was consistently ahead of the ''Herald Tribune''s. Between 1941 and 1945, advertising space in the ''Times'' increased from 42.58 percent of the paper to 49.68 percent, while the ''Tribune'' saw its ad space increase from 37.58 percent to 49.32 percent. In 1943 and 1944, more than half the ''Times'' went to advertising, a percentage the ''Herald Tribune'' did not meet until after the war. However, because the ''Tribune'' was generally a smaller paper than the ''Times'' and saw its ad space jump more, "the ''proportionate'' increase in the ''Tribune'' seemed greater than it was in absolute terms. The evidence that this disproportionate increase in the ''Tribune''s advertising content left its readers feeling deprived of war news coverage and sent them in droves to the ''Times'' is, at best, highly ambiguous."

The ''Herald Tribune'' always had at least a dozen correspondents in the field, the most famous of whom was Homer Bigart

Homer William Bigart (October 25, 1907 – April 16, 1991) was an American reporter who worked for the ''New York Herald Tribune'' from 1929 to 1955 (later known as the ''International Herald Tribune'') and for ''The New York Times'' from 1955 to ...

. Allowing wire services to write "big picture" stories, Bigart—who covered the Anzio Campaign, the Battle of Iwo Jima and the Battle of Okinawa—focused instead on writing about tactical

Tactic(s) or Tactical may refer to:

* Tactic (method), a conceptual action implemented as one or more specific tasks

** Military tactics, the disposition and maneuver of units on a particular sea or battlefield

** Chess tactics

** Political tacti ...

operations conducted by small units and individual soldiers, in order to "bring a dimension of reality and understanding to readers back home". Frequently risking his life to get the stories, Bigart was highly valued by his peers and the military, and won the 1945 Pulitzer Prize.

By the end of the conflict, the ''Herald Tribune'' had enjoyed some of its best financial years in its history. While the newspaper had just 63 percent of its rival's daily circulation (and 70 percent of the Sunday circulation of ''The Times''), its high-income readership gave the paper nearly 85 percent of ''The New York Times'' overall ad revenue, and had made $2 million a year between 1942 and 1945. In 1946, the ''Herald Tribune''s Sunday circulation hit an all-time peak of 708,754.

Decline: 1947–1958

Pressure from the ''Times''

The ''Herald Tribune'' began a decline shortly after World War II that had several causes. The Reid family was long accustomed to resolve shortfalls at the newspaper with subsidies from their fortune, rather than improved business practices, seeing the paper "as a hereditary possession to be sustained as a public duty rather than developed as a profit-making opportunity". With its generally marginal profitability, the ''Herald Tribune'' had few opportunities to reinvest in its operations as the ''Times'' did, and the Reids' mortgage on the newspaper made it difficult to raise outside cash for needed capital improvements.

After another profitable year in 1946, Bill Robinson, the ''Herald Tribune''s business manager, decided to reinvest the profits to make needed upgrades to the newspaper's pressroom. The investment squeezed the paper's resources, and Robinson decided to make up the difference at the end of the year by raising the ''Tribune''s price from three cents to a

The ''Herald Tribune'' began a decline shortly after World War II that had several causes. The Reid family was long accustomed to resolve shortfalls at the newspaper with subsidies from their fortune, rather than improved business practices, seeing the paper "as a hereditary possession to be sustained as a public duty rather than developed as a profit-making opportunity". With its generally marginal profitability, the ''Herald Tribune'' had few opportunities to reinvest in its operations as the ''Times'' did, and the Reids' mortgage on the newspaper made it difficult to raise outside cash for needed capital improvements.

After another profitable year in 1946, Bill Robinson, the ''Herald Tribune''s business manager, decided to reinvest the profits to make needed upgrades to the newspaper's pressroom. The investment squeezed the paper's resources, and Robinson decided to make up the difference at the end of the year by raising the ''Tribune''s price from three cents to a nickel

Nickel is a chemical element with symbol Ni and atomic number 28. It is a silvery-white lustrous metal with a slight golden tinge. Nickel is a hard and ductile transition metal. Pure nickel is chemically reactive but large pieces are slow ...

, expecting the ''Times'', which also needed to upgrade its facilities, to do the same. However, the ''Times'', concerned by the ''Tribune''s performance during the war, refused to go along. "We didn't want to give them any quarter," ''Times'' circulation manager Nathan Goldstein said. "Our numbers were on the rise, and we didn't want to do anything to jeopardize them. 'No free rides for the competition' was the way we looked at it." The move proved disastrous: In 1947, the ''Tribune''s daily circulation fell nine percent, from 348,626 to 319,867. Its Sunday circulation fell four percent, from 708,754 to 680,691. Although the overall percentage of advertising for the paper was higher than it was in 1947, the ''Times'' was still higher: 58 percent of the average space in ''The New York Times'' in 1947 was devoted to advertising, versus a little over 50 percent of the ''Tribune''. The ''Times'' would not raise its price until 1950.

Ogden Reid died early in 1947, making Helen Reid leader of the ''Tribune'' in name as well as in fact. Reid chose her son, Whitelaw Reid

Whitelaw Reid (October 27, 1837 – December 15, 1912) was an American politician and newspaper editor, as well as the author of ''Ohio in the War'', a popular work of history.

After assisting Horace Greeley as editor of the ''New-York Tribu ...

, known as "Whitie", as editor. The younger Reid had written for the newspaper and done creditable work covering the London Blitz

The Blitz was a German bombing campaign against the United Kingdom in 1940 and 1941, during the Second World War. The term was first used by the British press and originated from the term , the German word meaning 'lightning war'.

The Germa ...

, but had not been trained for the duties of his position and was unable to provide forceful leadership for the newspaper. The ''Tribune'' also failed to keep pace with the ''Times'' in its facilities: While both papers had about the same level of profits between 1947 and 1950, the ''Times'' was heavily reinvesting money in its plant and hiring new employees. The ''Tribune'', meanwhile, with Helen Reid's approval, cut $1 million from its budgets and fired 25 employees on the news side, reducing its foreign and crime coverage. Robinson was dismissive of the circulation lead of the ''Times'', saying in a 1948 memo that 75,000 of its rival's readers were "transients" who only read the wanted ads.

The ''Times'' also began to push the ''Tribune'' hard in suburbs, where the ''Tribune'' had previously enjoyed a commanding lead. At the urging of Goldstein, ''Times'' editors added features to appeal to commuters, expanded (and in some cases subsidized) home delivery, and paid retail display allowances—"kickbacks, in common parlance"—to the American News Company, the controller of many commuter newsstands, to achieve prominent display. ''Tribune'' executives were not blind to the challenge, but the economy drive at the paper undercut efforts to adequately compete. The newspaper fell into the red in 1951. The ''Herald Tribune''s losses reached $700,000 in 1953, and Robinson resigned late that year.

Leadership changes

The paper distinguished itself in its coverage of theKorean War

, date = {{Ubl, 25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953 (''de facto'')({{Age in years, months, weeks and days, month1=6, day1=25, year1=1950, month2=7, day2=27, year2=1953), 25 June 1950 – present (''de jure'')({{Age in years, months, weeks a ...

; Bigart and Marguerite Higgins

Marguerite Higgins Hall (September 3, 1920January 3, 1966) was an American reporter and war correspondent. Higgins covered World War II, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War, and in the process advanced the cause of equal access for female war c ...

, who engaged in a fierce rivalry, shared a Pulitzer Prize with ''Chicago Daily News

The ''Chicago Daily News'' was an afternoon daily newspaper in the midwestern United States, published between 1875 and 1978 in Chicago, Illinois.

History

The ''Daily News'' was founded by Melville E. Stone, Percy Meggy, and William Doughert ...

'' correspondent Keyes Beech and three other reporters in 1951. The ''Tribune''s cultural criticism was also prominent: John Crosby's radio and television column was syndicated in 29 newspapers by 1949, and Walter Kerr

Walter Francis Kerr (July 8, 1913 – October 9, 1996) was an American writer and Broadway theatre critic. He also was the writer, lyricist, and/or director of several Broadway plays and musicals as well as the author of several books, genera ...

began a successful three-decade career as a Broadway

Broadway may refer to:

Theatre

* Broadway Theatre (disambiguation)

* Broadway theatre, theatrical productions in professional theatres near Broadway, Manhattan, New York City, U.S.

** Broadway (Manhattan), the street

**Broadway Theatre (53rd Stree ...

reviewer at the ''Tribune'' in 1951. However, the paper's losses were continuing to mount. Whitelaw Reid was gradually replaced by his brother, Ogden R. Reid

Ogden Rogers Reid (June 24, 1925 – March 2, 2019) was an American politician and diplomat. He was the U.S. Ambassador to Israel and a six-term United States Representative from Westchester County, New York.

Early life

Reid was born in New Y ...

, nicknamed "Brown", to take charge of the paper. As president and publisher of the paper, Brown Reid tried to interject an energy his brother lacked and reach out to new audiences. In that spirit, the ''Tribune'' ran a promotion called "Tangle Towns", where readers were invited to unscramble the names of jumbled up town and city names in exchange for prizes. Reid also gave more prominent play to crime and entertainment stories. Much of the staff, including Whitelaw Reid, felt there was too much focus on circulation at the expense of the paper's editorial standards, but the promotions initially worked, boosting its weekday circulation to over 400,000.

Reid's ideas, however, "were prosaic in the extreme". His promotions included printing the sports section on green newsprint and a pocket-sized magazine for television listings that initially stopped the Sunday paper's circulation skid, but proved an empty product. The ''Tribune'' turned a profit in 1956, but the ''Times'' was rapidly outpacing it in news content, circulation, and ad revenue. The promotions largely failed to hold on to the ''Tribune''s new audiences; the Sunday edition began to slide again and the paper fell into the red in 1957. Through the decade, the ''Tribune'' was the only newspaper in the city to see its share of ad lineage drop, and longtime veterans of the paper, including Bigart, began departing. The Reids, who had by now turned their mortgage into stock, began seeking buyers to infuse the ''Tribune'' with cash, turning to John Hay "Jock" Whitney, whose family had a long association with the Reids. Whitney, recently named ambassador to Great Britain, had chaired Dwight Eisenhower's fundraising campaigns in 1952 and 1956 and was looking for something else to engage him beyond his largely ceremonial role in Great Britain. Whitney, who "did not want the ''Tribune'' to die", gave the newspaper $1.2 million over the objections of his investment advisors, who had doubts about the newspaper's viability. The loan came with the option to take controlling interest

A controlling interest is an ownership interest in a corporation with enough voting stock shares to prevail in any stockholders' motion. A majority of voting shares (over 50%) is always a controlling interest. When a party holds less than the major ...

of the newspaper if he made a second loan of $1.3 million. Brown Reid expected the $1.2 million to cover a deficit that would last through the end of 1958, but by that year the newspaper's loss was projected at $3 million, and Whitney and his advisors decided to exercise their option. The Reids, claiming to have put $20 million into the newspaper since the 1924 merger initially attempted to keep editorial control of the paper, but Whitney made it clear he would not invest additional money in the ''Tribune'' if the Reids remained at the helm. The family yielded, and Helen, Whitie and Brown Reid announced Whitney's takeover of the newspaper on August 28, 1958. The Reids retained a substantial stake in the ''Tribune'' until its demise, but Whitney and his advisors controlled the paper.

The Whitney Era: 1958–1966

"Who says a good newspaper has to be dull?"

Whitney initially left management of the newspaper to Walter Thayer, a longtime advisor. Thayer did not believe the ''Tribune'' was a financial investment—"it was a matter of 'let's set it up so that (Whitney) can do it if this is what he wants"—but moved to build a "hen house" of media properties to protect Whitney's investment and provide money for the ''Tribune''. Over the next two years, Whitney's firm acquired '' Parade'', five television stations and four radio stations. The properties, merged into a new company called Whitney Communications Corporation, proved profitable, but executives chafed at subsidizing the ''Tribune.'' Thayer also looked for new leadership for the newspaper. In 1961—the same year Whitney returned to New York—the ''Tribune'' hired John Denson, a ''Newsweek

''Newsweek'' is an American weekly online news magazine co-owned 50 percent each by Dev Pragad, its president and CEO, and Johnathan Davis, who has no operational role at ''Newsweek''. Founded as a weekly print magazine in 1933, it was widely ...

'' editor and native of Louisiana who was "a critical mass of intensity and irascibility relieved by interludes of amiability." Denson had helped raise ''Newsweek's'' circulation by 50 percent during his tenure, in part through innovative layouts and graphics, and he brought the same approach to the ''Tribune''. Denson "swept away the old front-page architecture, essentially vertical in structure" and laid out stories horizontally, with unorthodox and sometimes cryptic headlines; large photos and information boxes. The "Densonized" front page sparked a mixed reaction from media professionals and within the newspaper—''Tribune'' copy editor John Price called it "silly but expert silliness" and ''Time

Time is the continued sequence of existence and events that occurs in an apparently irreversible succession from the past, through the present, into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequence events, ...

'' called the new front page "all overblown pictures (and) klaxon headlines"—but the newspaper's circulation jumped in 1961 and those within the ''Tribune'' said "the alternative seemed to be the death of the newspaper." The ''Tribune'' also launched an ad campaign targeting the ''Times'' with the slogan "Who says a good newspaper has to be dull?"

The ''Tribune''s revival came as the ''Times'' was bringing on new leadership and facing financial trouble of its own. While the ''Times'' picked up 220,000 readers during the 1950s, its profits declined to $348,000 by 1960 due to the costs of an international edition and investments into the newspaper. A western edition of the newspaper, launched in 1961 by new publisher Orvil Dryfoos

Orvil Eugene Dryfoos (November 8, 1912 – May 25, 1963) was the publisher of ''The New York Times'' from 1961 to his death. He entered ''The Times'' family via his marriage to Marian Sulzberger, daughter of then-publisher Arthur Hays Sulzberger ...

in an attempt to build the paper's national audience, also proved to be a drain and the ''Times'' profits fell to $59,802 by the end of 1961. While the ''Times'' outdistanced its rival in circulation and ad lineage, the ''Tribune'' continued to draw a sizeable amount of advertising, due to its wealthy readership. The ''Times'' management watched the ''Tribune''s changes with "uneasy contempt for their debasement of classic ''Tribune'' craftmanship but also with grudging admiration for their catchiness and shrewdness." ''Times'' managing editor Turner Catledge

William Turner Catledge (; 1901–1983) was an American journalist, best known for his work at ''The New York Times''. He was managing editor from 1952 to 1964, when he became the paper's first executive editor.

After retiring in 1968, he serv ...

began visiting the city room of his newspaper to read the early edition of the ''Tribune'' and sometimes responded with changes, though he ultimately decided Denson's approach would be unsuccessful. But the financial challenges both papers faced led Dryfoos, Thayer, and previous ''Times'' publisher Arthur Hays Sulzberger

Arthur Hays Sulzberger (September 12, 1891December 11, 1968) was the publisher of ''The New York Times'' from 1935 to 1961. During that time, daily circulation rose from 465,000 to 713,000 and Sunday circulation from 745,000 to 1.4 million; the st ...

to discuss a possible merger of the ''Times'' and the ''Tribune,'' a project codenamed "Canada" at the ''Times''.

Denson's approaches to the front page often required expensive work stoppages to redo the front page, which increased expenses and drew concern from Whitney and Thayer. Denson also had a heavy-handed approach to the newsroom that led some to question his stability, and led him to clash with Thayer. Denson left the ''Tribune'' in October 1962 after Thayer attempted to move the nightly lockup of the newspaper to managing editor James Bellows. But Denson's approach would continue at the paper. Daily circulation at the ''Tribune'' reached an all-time high of 412,000 in November, 1962.

Labor unrest, New Journalism

The New York newspaper industry came to an abrupt halt on December 8, 1962, when the local of theInternational Typographical Union

The International Typographical Union (ITU) was a US trade union for the printing trade for newspapers and other media. It was founded on May 3, 1852, in the United States as the National Typographical Union, and changed its name to the Interna ...

, led by Bert Powers, walked off the job, leading to the 114-day 1962–63 New York City newspaper strike

Year 196 ( CXCVI) was a leap year starting on Thursday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar. At the time, it was known as the Year of the Consulship of Dexter and Messalla (or, less frequently, year 949 ''Ab urbe condit ...

. The ITU, known as "Big Six", represented 3,800 printers, as well as workers at 600 printshops and 28 publications in the city but, like other newspaper unions, had taken a backseat to the Newspaper Guild

The NewsGuild-CWA is a trade union, labor union founded by newspaper journalists in 1933. In addition to improving wages and working conditions, its constitution says its purpose is to fight for honesty in journalism and the news industry's busin ...

(which had the largest membership among the unions) in contract negotiations. This arrangement began to fray in the 1950s, as the craft unions felt the Guild was too inclined to accept publishers' offers without concern for those who did the manual work of printing. Powers wanted to call a strike to challenge the Guild's leadership and thrust ITU to the fore.

New technology was also a concern for management and labor. Teletypesetting (TTS), introduced in the 1950s, was used by ''The Wall Street Journal

''The Wall Street Journal'' is an American business-focused, international daily newspaper based in New York City, with international editions also available in Chinese and Japanese. The ''Journal'', along with its Asian editions, is published ...

'' and promised to be far more efficient than the linotype machines still used by the''Tribune'' and most other New York newspapers. TTS required less skill than the complex linotype machines, and publishers wanted to automate to save money. ITU was not necessarily opposed to TTS—it trained its members on the new equipment—but wanted to control the rate at which automation occurred; assurances that TTS operators would be paid at the same rates as linotype workers; that at least a portion of the savings from publishers would go toward union pension plans (to allow funding to continue as the workforce and union membership declined) and guarantees that no printer would lose their job as a result of the new technology. Publishers were willing to protect jobs and reduce the workforce through attrition, but balked at what they viewed as "tribute payments" to the unions. After nearly a five-month strike, the unions and the publishers reached an agreement in March, 1963—in which the unions won a weekly worker wage and benefit increase of $12.63 and largely forestalled automation—and the city's newspapers resumed publication on April 1, 1963.

The strike added new costs to all newspapers, and increased the ''Tribune''s losses to $4.2 million while slashing its circulation to 282,000. Dryfoos died of a heart ailment shortly after the strike and was replaced as ''Times'' publisher by Arthur Ochs Sulzberger

Arthur Ochs Sulzberger Sr. (February 5, 1926 – September 29, 2012) was an American publisher and a businessman. Born into a prominent media and publishing family, Sulzberger became publisher of ''The New York Times'' in 1963 and chairman of t ...

, who ended merger talks with the ''Tribune'' because "it just didn't make any long-term sense to me." The paper also lost long-established talent, including Marguerite Higgins, Earl Mazo and Washington bureau chief Robert Donovan. Whitney, however, remained committed to the ''Tribune'', and promoted James Bellows to editor of the newspaper. Bellows kept Denson's format but "eliminated features that lacked substance or sparkle" while promoting new talent, including movie critic Judith Crist

Judith Crist (; May 22, 1922 – August 7, 2012) was an American film critic and academic.

She appeared regularly on the ''Today'' show from 1964 to 1973 Martin, Douglas (August 8, 2012)"Judith Crist, Zinging and Influential Film Critic, ...

and Washington columnists Robert Novak

Robert David Sanders Novak (February 26, 1931 – August 18, 2009) was an American syndicated columnist, journalist, television personality, author, and conservative political commentator. After working for two newspapers before serving in the ...

and Rowland Evans

Rowland Evans Jr. (April 28, 1921 – March 23, 2001) was an American journalist. He was known best for his decades-long syndicated column and television partnership with Robert Novak, a partnership that endured, if only by way of a joint subsc ...

.

From 1963 until its demise, the ''Tribune'' published a weekly magazine supplement entitled ''Book Week''; Susan Sontag published two early essays there. The ''Tribune'' also began experimenting with an approach to news that later was referred to as the New Journalism

New Journalism is a style of news writing and journalism, developed in the 1960s and 1970s, that uses literary techniques unconventional at the time. It is characterized by a subjective perspective, a literary style reminiscent of long-form non- ...

. National editor Dick Wald wrote in one memo "there is no mold for a newspaper story," and Bellows encouraged his reporters to work "in whatever style made them comfortable." Tom Wolfe

Thomas Kennerly Wolfe Jr. (March 2, 1930 – May 14, 2018)Some sources say 1931; ''The New York Times'' and Reuters both initially reported 1931 in their obituaries before changing to 1930. See and was an American author and journalist widely ...

, who joined the paper after working at ''The Washington Post

''The Washington Post'' (also known as the ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'') is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C. It is the most widely circulated newspaper within the Washington metropolitan area and has a large nati ...

'', wrote lengthy features about city life; asking an editor how long his pieces should be, he received the reply "until it gets boring." Bellows soon moved Wolfe to the ''Tribune''s new Sunday magazine, '' New York'', edited by Clay Felker

Clay Schuette Felker (October 2, 1925 – July 1, 2008) was an American magazine editor and journalist who co-founded ''New York'' magazine in 1968. He was known for bringing numerous journalists into the profession. ''The New York Times'' wrote ...

. Bellows also prominently featured Jimmy Breslin

James Earle Breslin (October 17, 1928 – March 19, 2017) was an American journalist and author. Until the time of his death, he wrote a column for the New York ''Daily News'' Sunday edition.''Current Biography 1942'', pp. 648–51: "Patterson, ...

in the columns of the ''Tribune,'' as well as writer Gail Sheehy

Gail Sheehy (born Gail Henion; November 27, 1936 – August 24, 2020) was an American author, journalist, and lecturer. She was the author of seventeen books and numerous high-profile articles for magazines such as ''New York'' and ''Vanity ...

.

Editorially, the newspaper remained in the liberal Republican camp, both strongly anti-communist, pro-business, and supportive of civil rights. In April 1963, the ''Tribune'' published the " Letter from Birmingham Jail", written by Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister and activist, one of the most prominent leaders in the civil rights movement from 1955 until his assassination in 1968 ...