The Man In The Moone on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''The Man in the Moone'' is a book by the English

Godwin's book appeared in a time of great interest in the Moon and astronomical phenomena, and of important developments in celestial observation, mathematics and

Godwin's book appeared in a time of great interest in the Moon and astronomical phenomena, and of important developments in celestial observation, mathematics and

Until Grant McColley, a historian of early Modern English literature, published his "The Date of Godwin's ''Domingo Gonsales''" in 1937, it was thought that Godwin wrote ''The Man in the Moone'' relatively early in his life – perhaps during his time at Christ Church from 1578 to 1584, or maybe even as late as 1603. But McColley proposed a much later date of 1627 or 1628, based on internal and biographical evidence. A number of ideas about the physical properties of the Earth and the Moon, including claims about "a secret property that operates in a manner similar to that of a loadstone attracting iron", did not appear until after 1620. And Godwin seems to borrow the concept of using a flock of strong, trained birds to fly Gonsales to the Moon from

Until Grant McColley, a historian of early Modern English literature, published his "The Date of Godwin's ''Domingo Gonsales''" in 1937, it was thought that Godwin wrote ''The Man in the Moone'' relatively early in his life – perhaps during his time at Christ Church from 1578 to 1584, or maybe even as late as 1603. But McColley proposed a much later date of 1627 or 1628, based on internal and biographical evidence. A number of ideas about the physical properties of the Earth and the Moon, including claims about "a secret property that operates in a manner similar to that of a loadstone attracting iron", did not appear until after 1620. And Godwin seems to borrow the concept of using a flock of strong, trained birds to fly Gonsales to the Moon from

McColley knew of only one surviving copy of the first edition, held at the

McColley knew of only one surviving copy of the first edition, held at the

Godwin had a lifelong interest in language and communication (as is evident in Gonsales's various means of communicating with his servant Diego on St Helena), and this was the topic of his ''Nuncius inanimatus'' (1629). The language Gonsales encounters on the Moon bears no relation to any he is familiar with, and it takes him months to acquire sufficient fluency to communicate properly with the inhabitants. While its vocabulary appears limited, its possibilities for meaning are multiplied since the meaning of words and phrases also depends on tone. Invented languages were an important element of earlier fantastical accounts such as Thomas More's ''

Godwin had a lifelong interest in language and communication (as is evident in Gonsales's various means of communicating with his servant Diego on St Helena), and this was the topic of his ''Nuncius inanimatus'' (1629). The language Gonsales encounters on the Moon bears no relation to any he is familiar with, and it takes him months to acquire sufficient fluency to communicate properly with the inhabitants. While its vocabulary appears limited, its possibilities for meaning are multiplied since the meaning of words and phrases also depends on tone. Invented languages were an important element of earlier fantastical accounts such as Thomas More's ''

divine

Divinity or the divine are things that are either related to, devoted to, or proceeding from a deity.divine

and Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

bishop Francis Godwin (1562–1633), describing a "voyage of utopian discovery". Long considered to be one of his early works, it is now generally thought to have been written in the late 1620s. It was first published posthumously in 1638 under the pseudonym of Domingo Gonsales. The work is notable for its role in what was called the "new astronomy", the branch of astronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies astronomical object, celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and chronology of the Universe, evolution. Objects of interest ...

influenced especially by Nicolaus Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (; pl, Mikołaj Kopernik; gml, Niklas Koppernigk, german: Nikolaus Kopernikus; 19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath, active as a mathematician, astronomer, and Catholic Church, Catholic cano ...

. Although Copernicus is the only astronomer mentioned by name, the book also draws on the theories of Johannes Kepler

Johannes Kepler (; ; 27 December 1571 – 15 November 1630) was a German astronomer, mathematician, astrologer, natural philosopher and writer on music. He is a key figure in the 17th-century Scientific Revolution, best known for his laws ...

and William Gilbert. Godwin's astronomical theories were greatly influenced by Galileo Galilei

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642) was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a polymath. Commonly referred to as Galileo, his name was pronounced (, ). He was ...

's '' Sidereus Nuncius'' (1610), but unlike Galileo, Godwin proposes that the dark spots on the Moon are seas, one of many parallels with Kepler's '' Somnium sive opus posthumum de astronomia lunari'' of 1634.

The story is written as a first-person narrative from the perspective of Domingo Gonsales, the book's fictional author. In his opening address to the reader the equally fictional translator "E. M." promises "an essay of ''Fancy'', where ''Invention'' is shewed with ''Judgment''".

Some critics consider ''The Man in the Moone'', along with Kepler's ''Somnium'', to be one of the first works of science fiction

Science fiction (sometimes shortened to Sci-Fi or SF) is a genre of speculative fiction which typically deals with imaginative and futuristic concepts such as advanced science and technology, space exploration, time travel, parallel unive ...

. The book was well known in the 17th century, and even inspired parodies by Cyrano de Bergerac and Aphra Behn

Aphra Behn (; bapt. 14 December 1640 – 16 April 1689) was an English playwright, poet, prose writer and translator from the Restoration era. As one of the first English women to earn her living by her writing, she broke cultural barrie ...

, but has been neglected in critical history. Recent studies have focused on Godwin's theories of language, the mechanics of lunar travel, and his religious position and sympathies as evidenced in the book.

Plot summary

Domingo Gonsales is a citizen of Spain, forced to flee to theEast Indies

The East Indies (or simply the Indies), is a term used in historical narratives of the Age of Discovery. The Indies refers to various lands in the East or the Eastern hemisphere, particularly the islands and mainlands found in and around t ...

after killing a man in a duel

A duel is an arranged engagement in combat between two people, with matched weapons, in accordance with agreed-upon Code duello, rules.

During the 17th and 18th centuries (and earlier), duels were mostly single combats fought with swords (the r ...

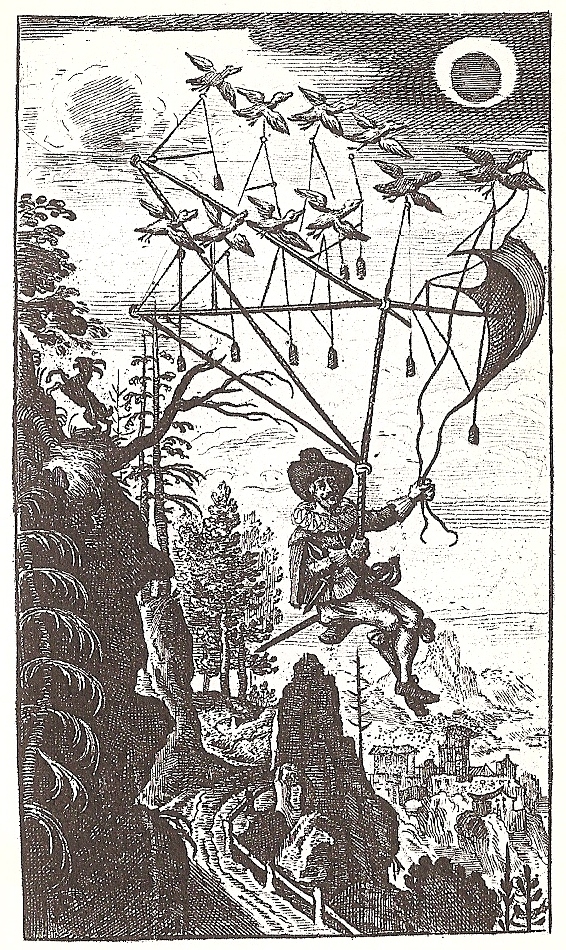

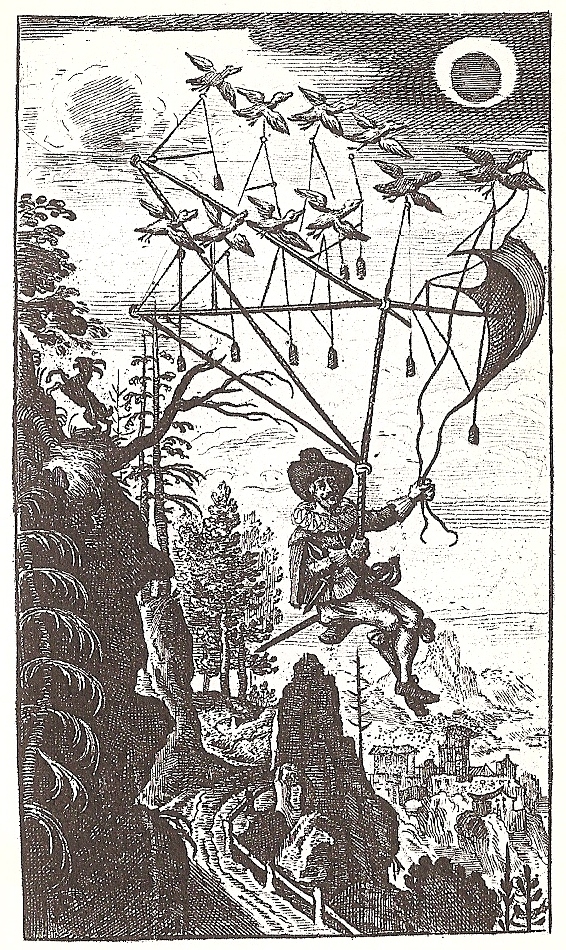

. There he prospers by trading in jewels, and having made his fortune decides to return to Spain. On his voyage home he becomes seriously ill, and he and a negro servant Diego are put ashore on St Helena, a remote island with a reputation for "temperate and healthful" air. A scarcity of food forces Gonsales and Diego to live some miles apart, but Gonsales devises a variety of systems to allow them to communicate. Eventually he comes to rely on a species of bird he describes as some kind of wild swan, a gansa, to carry messages and provisions between himself and Diego. Gonsales gradually comes to realise that these birds are able to carry substantial burdens, and resolves to construct a device by which a number of them harnessed together might be able to support the weight of a man, allowing him to move around the island more conveniently. Following a successful test flight he determines to resume his voyage home, hoping that he might "fill the world with the Fame of isGlory and Renown". But on his way back to Spain, accompanied by his birds and the device he calls his Engine, his ship is attacked by an English fleet off the coast of Tenerife

Tenerife (; ; formerly spelled ''Teneriffe'') is the largest and most populous island of the Canary Islands. It is home to 43% of the total population of the archipelago. With a land area of and a population of 978,100 inhabitants as of Janu ...

and he is forced to escape by taking to the air.

After setting down briefly on Tenerife, Gonsales is forced to take off again by the imminent approach of hostile natives. But rather than flying to a place of safety among the Spanish inhabitants of the island the gansas fly higher and higher. On the first day of his flight Gonsales encounters "illusions of 'Devils and Wicked Spirits in the shape of men and women, some of whom he is able to converse with. They provide him with food and drink for his journey and promise to set him down safely in Spain if only he will join their "Fraternity", and "enter into such Covenants as they had made to their Captain and Master, whom they would not name". Gonsales declines their offer, and after a journey of 12 days reaches the Moon. Suddenly feeling very hungry he opens the provisions he was given en route, only to find nothing but dry leaves, goat's hair and animal dung, and that his wine "stunk like Horse-piss". He is soon discovered by the inhabitants of the Moon, the Lunars, whom he finds to be tall Christian people enjoying a happy and carefree life in a kind of pastoral paradise. Gonsales discovers that order is maintained in this apparently utopian state by swapping delinquent children with terrestrial children.

The Lunars speak a language consisting "not so much of words and letters as tunes and strange sounds", which Gonsales succeeds in gaining some fluency in after a couple of months. Six months or so after his arrival Gonsales becomes concerned about the condition of his gansas, three of whom have died. Fearing that he may never be able to return to Earth and see his children again if he delays further, he decides to take leave of his hosts, carrying with him a gift of precious stones from the supreme monarch of the Moon, Irdonozur. The stones are of three different sorts: Poleastis, which can store and generate great quantities of heat; Macbrus, which generates great quantities of light; and Ebelus, which when one side of the stone is clasped to the skin renders a man weightless, or half as heavy again if the other side is touched.

Gonsales harnesses his gansas to his Engine and leaves the Moon on 29 March 1601. He lands in China about nine days later, without re-encountering the illusions of men and women he had seen on his outward journey and with the help of his Ebelus, which helps the birds to avoid plummeting to Earth as the weight of Gonsales and his Engine threatens to become too much for them. He is quickly arrested and taken before the local mandarin

Mandarin or The Mandarin may refer to:

Language

* Mandarin Chinese, branch of Chinese originally spoken in northern parts of the country

** Standard Chinese or Modern Standard Mandarin, the official language of China

** Taiwanese Mandarin, Stand ...

, accused of being a magician, and as a result is confined in the mandarin's palace. He learns to speak the local dialect of Chinese, and after some months of confinement is summoned before the mandarin to give an account of himself and his arrival in China, which gains him the mandarin's trust and favour. Gonsales hears of a group of Jesuit

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

s, and is granted permission to visit them. He writes an account of his adventures, which the Jesuits arrange to have sent back to Spain. The story ends with Gonsales's fervent wish that he may one day be allowed to return to Spain, and "that by enriching my country with the knowledge of these hidden mysteries, I may at least reap the glory of my fortunate misfortunes".

Background and contexts

Godwin, the son of Thomas Godwin, Bishop of Bath and Wells, was elected a student ofChrist Church, Oxford

Christ Church ( la, Ædes Christi, the temple or house, '' ædēs'', of Christ, and thus sometimes known as "The House") is a constituent college of the University of Oxford in England. Founded in 1546 by King Henry VIII, the college is uniqu ...

, in 1578, from where he received his Bachelor of Arts (1581) and Master of Arts degrees (1584); after entering the church he gained his Bachelor (1594) and Doctor of Divinity (1596) degrees. He gained prominence (even internationally) in 1601 by publishing his ''Catalogue of the Bishops of England since the first planting of the Christian Religion in this Island'', which enabled his rapid rise in the church hierarchy. During his life, he was known as a historian.

Scientific advances and lunar speculation

Godwin's book appeared in a time of great interest in the Moon and astronomical phenomena, and of important developments in celestial observation, mathematics and

Godwin's book appeared in a time of great interest in the Moon and astronomical phenomena, and of important developments in celestial observation, mathematics and mechanics

Mechanics (from Ancient Greek: μηχανική, ''mēkhanikḗ'', "of machines") is the area of mathematics and physics concerned with the relationships between force, matter, and motion among physical objects. Forces applied to objects r ...

. The influence particularly of Nicolaus Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (; pl, Mikołaj Kopernik; gml, Niklas Koppernigk, german: Nikolaus Kopernikus; 19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath, active as a mathematician, astronomer, and Catholic Church, Catholic cano ...

led to what was called the "new astronomy"; Copernicus is the only astronomer Godwin mentions by name, but the theories of Johannes Kepler

Johannes Kepler (; ; 27 December 1571 – 15 November 1630) was a German astronomer, mathematician, astrologer, natural philosopher and writer on music. He is a key figure in the 17th-century Scientific Revolution, best known for his laws ...

and William Gilbert are also discernible. Galileo Galilei

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642) was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a polymath. Commonly referred to as Galileo, his name was pronounced (, ). He was ...

's 1610 publication '' Sidereus Nuncius'' (usually translated as "The Sidereal Messenger") had a great influence on Godwin's astronomical theories, although Godwin proposes (unlike Galileo) that the dark spots on the Moon are seas, one of many similarities between ''The Man in the Moone'' and Kepler's '' Somnium sive opus posthumum de astronomia lunaris'' of 1634 ("The Dream, or Posthumous Work on Lunar Astronomy").

Speculation on lunar habitation was nothing new in Western thought, but it intensified in England during the early 17th century: Philemon Holland's 1603 translation of Plutarch

Plutarch (; grc-gre, Πλούταρχος, ''Ploútarchos''; ; – after AD 119) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ''P ...

's '' Moralia'' introduced Greco-Roman speculation to the English vernacular, and poets including Edmund Spenser

Edmund Spenser (; 1552/1553 – 13 January 1599) was an English poet best known for ''The Faerie Queene'', an epic poem and fantastical allegory celebrating the Tudor dynasty and Elizabeth I. He is recognized as one of the premier craftsmen of ...

proposed that other worlds, including the Moon, could be inhabited. Such speculation was prompted also by the expanding geographical view of the world. The 1630s saw the publication of a translation of Lucian

Lucian of Samosata, '; la, Lucianus Samosatensis ( 125 – after 180) was a Hellenized Syrian satirist, rhetorician and pamphleteer

Pamphleteer is a historical term for someone who creates or distributes pamphlets, unbound (and therefore ...

's ''True History

''A True Story'' ( grc, Ἀληθῆ διηγήματα, ''Alēthē diēgēmata''; or ), also translated as True History, is a long novella or short novel written in the second century AD by the Greek author Lucian of Samosata. The novel is a sa ...

'' (1634), containing two accounts of trips to the Moon, and a new edition of Ariosto's ''Orlando Furioso

''Orlando furioso'' (; ''The Frenzy of Orlando'', more loosely ''Raging Roland'') is an Italian epic poem by Ludovico Ariosto which has exerted a wide influence on later culture. The earliest version appeared in 1516, although the poem was no ...

'', likewise featuring an ascent to the Moon. In both books the Moon is inhabited, and this theme was given an explicit religious importance by writers such as John Donne

John Donne ( ; 22 January 1572 – 31 March 1631) was an English poet, scholar, soldier and secretary born into a recusant family, who later became a clergy, cleric in the Church of England. Under royal patronage, he was made Dean of St Paul's ...

, who in ''Ignatius His Conclave

''Ignatius His Conclave'' is a 1611 work by 16/17th century metaphysical poet John Donne. The title is an example of "his genitive" and means the conclave of Ignatius. The work satirizes the Jesuits. In the story, St. Ignatius of Loyola, the f ...

'' (1611, with new editions in 1634 and 1635) satirised a "lunatic church" on the Moon founded by Lucifer and the Jesuits

The Society of Jesus ( la, Societas Iesu; abbreviation: SJ), also known as the Jesuits (; la, Iesuitæ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

. Lunar speculation reached an acme at the end of the decade, with the publication of Godwin's ''The Man in the Moone'' (1638) and John Wilkins

John Wilkins, (14 February 1614 – 19 November 1672) was an Anglican clergyman, natural philosopher, and author, and was one of the founders of the Royal Society. He was Bishop of Chester from 1668 until his death.

Wilkins is one of the fe ...

's ''The Discovery of a World in the Moone'' (also 1638, and revised in 1640).

Dating evidence

Until Grant McColley, a historian of early Modern English literature, published his "The Date of Godwin's ''Domingo Gonsales''" in 1937, it was thought that Godwin wrote ''The Man in the Moone'' relatively early in his life – perhaps during his time at Christ Church from 1578 to 1584, or maybe even as late as 1603. But McColley proposed a much later date of 1627 or 1628, based on internal and biographical evidence. A number of ideas about the physical properties of the Earth and the Moon, including claims about "a secret property that operates in a manner similar to that of a loadstone attracting iron", did not appear until after 1620. And Godwin seems to borrow the concept of using a flock of strong, trained birds to fly Gonsales to the Moon from

Until Grant McColley, a historian of early Modern English literature, published his "The Date of Godwin's ''Domingo Gonsales''" in 1937, it was thought that Godwin wrote ''The Man in the Moone'' relatively early in his life – perhaps during his time at Christ Church from 1578 to 1584, or maybe even as late as 1603. But McColley proposed a much later date of 1627 or 1628, based on internal and biographical evidence. A number of ideas about the physical properties of the Earth and the Moon, including claims about "a secret property that operates in a manner similar to that of a loadstone attracting iron", did not appear until after 1620. And Godwin seems to borrow the concept of using a flock of strong, trained birds to fly Gonsales to the Moon from Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Alban (; 22 January 1561 – 9 April 1626), also known as Lord Verulam, was an English philosopher and statesman who served as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England. Bacon led the advancement of both ...

's ''Sylva sylvarum'' ("Natural History"), published in July 1626. All this evidence supports McColley's dating of "1626–29, with the probable years of composition 1627–28", which is now generally accepted.

William Poole, in his 2009 edition of ''The Man in the Moone'', provides additional evidence for a later dating. Godwin, he argues, most likely got his knowledge of the Jesuit mission in China (founded in 1601) from a 1625 edition of Samuel Purchas

Samuel Purchas ( – 1626) was an England, English Anglican cleric who published several volumes of reports by travellers to foreign countries.

Career

Purchas was born at Thaxted, Essex, England, Essex son of an English yeoman. He graduated fr ...

s ''Purchas his Pilgrimage''. This book contains a redaction from Nicolas Trigault's '' De Christiana expeditione apud Sinas suscepta ab Societate Jesu'' (1615) ("Concerning the Christian expedition to China undertaken by the Society of Jesus"), itself the redaction of a manuscript by the Jesuit priest Matteo Ricci

Matteo Ricci, SJ (; la, Mattheus Riccius; 6 October 1552 – 11 May 1610), was an Italians, Italian Society of Jesus, Jesuit Priesthood in the Catholic Church, priest and one of the founding figures of the Jesuit China missions. He create ...

. Poole also sees the influence of Robert Burton

Robert Burton (8 February 1577 – 25 January 1640) was an English author and fellow of Oxford University, who wrote the encyclopedic tome ''The Anatomy of Melancholy''.

Born in 1577 to a comfortably well-off family of the landed gentry, Burt ...

, who in the second volume of '' The Anatomy of Melancholy'' had speculated on gaining astronomical knowledge through telescopic observation (citing Galileo) or from space travel (Lucian). Appearing for the first time in the 1628 edition of the ''Anatomy'' is a section on planetary periods, which gives a period for Mars of three years – had Godwin used William Gilbert's ''De Magnete

''De Magnete, Magneticisque Corporibus, et de Magno Magnete Tellure'' (''On the Magnet and Magnetic Bodies, and on That Great Magnet the Earth'') is a scientific work published in 1600 by the English physician and scientist William Gilbert. A h ...

'' (1600) for this detail he would have found a Martian period of two years. Finally, Poole points to what he calls a "genetic debt": while details on for instance the Martian period could have come from a few other sources, Burton and Godwin are the only two writers of the time to combine an interest in alien life with the green children of Woolpit, from a 12th-century account of two mysterious green children found in Suffolk. Poole sees this reference as strong evidence for Godwin's reliance on Burton.

One of Godwin's "major intellectual debts" is to Gilbert's ''De Magnete'', in which Gilbert argued that the Earth was magnetic, though he may have used a derivative account by Mark Ridley or a geographical textbook by Nathanael Carpenter. It is unlikely that Godwin could have gathered first-hand evidence used in narrating the events in his book (such as the details of Gonsales's journey back from the East, especially a description of Saint Helena

Saint Helena () is a British overseas territory located in the South Atlantic Ocean. It is a remote volcanic tropical island west of the coast of south-western Africa, and east of Rio de Janeiro in South America. It is one of three constitu ...

and its importance as a resting place for sick mariners), and more likely that he relied on travel adventures and other books. He used Trigault's ''De Christiana expeditione apud Sinas'' (1615), based on a manuscript by Matteo Ricci, the founder of the Jesuit mission in Beijing in 1601, for information about that mission. Details pertaining to the sea voyage and Saint Helena likely came from Thomas Cavendish's account of his circumnavigation of the world, available in Richard Hakluyt

Richard Hakluyt (; 1553 – 23 November 1616) was an English writer. He is known for promoting the English colonization of North America through his works, notably ''Divers Voyages Touching the Discoverie of America'' (1582) and ''The Pri ...

's ''Principal Navigations'' (1599–1600) and in ''Purchas His Pilgrimage'', first published in 1613. Information on the Dutch Revolt

The Eighty Years' War or Dutch Revolt ( nl, Nederlandse Opstand) (Historiography of the Eighty Years' War#Name and periodisation, c.1566/1568–1648) was an armed conflict in the Habsburg Netherlands between disparate groups of rebels and t ...

, the historical setting for the early part of Gonsales' career, likely came from the annals of Emanuel van Meteren, a Dutch historian working in London.

English editions and translations

McColley knew of only one surviving copy of the first edition, held at the

McColley knew of only one surviving copy of the first edition, held at the British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

(now British Library

The British Library is the national library of the United Kingdom and is one of the largest libraries in the world. It is estimated to contain between 170 and 200 million items from many countries. As a legal deposit library, the British ...

C.56.c.2), which was the basis for his 1937 edition of ''The Man in the Moone'' and ''Nuncius Inanimatus'', an edition criticised by literary critic Kathleen Tillotson as lacking in textual care and consistency. H. W. Lawton's review published six years earlier mentions a second copy in the Bibliothèque nationale de France

The Bibliothèque nationale de France (, 'National Library of France'; BnF) is the national library of France, located in Paris on two main sites known respectively as ''Richelieu'' and ''François-Mitterrand''. It is the national repository ...

, V.20973 (now RES P- V- 752 (6)), an omission also noted by Tillotson.

For the text of his 2009 edition, William Poole collated a copy in the Bodleian Library

The Bodleian Library () is the main research library of the University of Oxford, and is one of the oldest libraries in Europe. It derives its name from its founder, Sir Thomas Bodley. With over 13 million printed items, it is the second- ...

Oxford (Ashm. 940(1)) with that in the British Library. The printer of the first edition of ''The Man in the Moone'' is identified on the title page as John Norton, and the book was sold by Joshua Kirton and Thomas Warren. It also includes an epistle

An epistle (; el, ἐπιστολή, ''epistolē,'' "letter") is a writing directed or sent to a person or group of people, usually an elegant and formal didactic letter. The epistle genre of letter-writing was common in ancient Egypt as par ...

introducing the work and attributed to "E. M.", perhaps the fictitious Edward Mahon identified in the Stationers' Register

The Stationers' Register was a record book maintained by the Stationers' Company of London. The company is a trade guild given a royal charter in 1557 to regulate the various professions associated with the publishing industry, including print ...

as the translator from the original Spanish. Poole speculates that this Edward Mahon might be Thomas or Morgan Godwin, two of the bishop's sons who had worked with their father on telegraphy

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas p ...

, but adds that Godwin's third son, Paul, might be involved as well. The partial revision of the manuscript (the first half has dates according to the Gregorian calendar

The Gregorian calendar is the calendar used in most parts of the world. It was introduced in October 1582 by Pope Gregory XIII as a modification of, and replacement for, the Julian calendar. The principal change was to space leap years dif ...

, the second half still follows the superseded Julian calendar

The Julian calendar, proposed by Roman consul Julius Caesar in 46 BC, was a reform of the Roman calendar. It took effect on , by edict. It was designed with the aid of Greek mathematicians and astronomers such as Sosigenes of Alexandr ...

) indicates an unfinished manuscript, which Paul might have acquired after his father's death and passed on to his former colleague Joshua Kirton: Paul Godwin and Kirton were apprenticed to the same printer, John Bill, and worked there together for seven years. Paul may have simply continued the "E. M." hoax unknowingly, and/or may have been responsible for partial revision of the manuscript. To the second edition, published in 1657, was added Godwin's ''Nuncius Inanimatus'' (in English and Latin; first published in 1629). The third edition was published in 1768; its text was abridged, and a description of St Helena

Saint Helena () is a British overseas territory located in the South Atlantic Ocean. It is a remote volcanic tropical island west of the coast of south-western Africa, and east of Rio de Janeiro in South America. It is one of three constitu ...

(by printer Nathaniel Crouch) functioned as an introduction.

A French translation by Jean Baudoin

Jean Baudoin (1662–1698) was a French Sulpician priest who served as a missionary in Acadia, and later as a chaplain during military expeditions carried on by Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville.

Life

Jean Baudoin studied at the College of Nantes with ...

, ''L'Homme dans la Lune'', was published in 1648, and republished four more times. This French version excised the narrative's sections on Lunar Christianity, as so do the many translations based on it, including the German translation incorrectly ascribed to Hans Jakob Christoffel von Grimmelshausen

Hans Jakob Christoffel von Grimmelshausen (1621/22 – 17 August 1676) was a German author. He is best known for his 1669 picaresque novel ''Simplicius Simplicissimus'' (german: link=no, Der abenteuerliche Simplicissimus) and the accompanyi ...

, ''Der fliegende Wandersmann nach dem Mond'', 1659. Johan van Brosterhuysen (c. 1594–1650) translated the book into Dutch, and a Dutch translation – possibly Brosterhuysen's, although the attribution is uncertain – went through seven printings in the Netherlands between 1645 and 1718. The second edition of 1651 and subsequent editions include a continuation of unknown authorship relating Gonsales' further adventures.

Themes

Religion

The story is set during the reign of QueenElizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen".

El ...

, a period of religious conflict in England. Not only was there the threat of a Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

resurgence but there were also disputes within the Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

Church. When Gonsales first encounters the Lunars he exclaims "''Jesu Maria''", at which the Lunars fall to their knees, but although they revere the name of Jesus they are unfamiliar with the name Maria, suggesting that they are Protestants rather than Catholics; Poole is of the same opinion: "their lack of reaction to the name of Mary suggests that they have not fallen into the errors of the Catholic Church, despite some otherwise rather Catholic-looking institutions on the moon". Beginning in the 1580s, when Godwin was a student at Oxford University, many publications criticising the governance of the established Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

circulated widely, until in 1586 censorship was introduced, resulting in the Martin Marprelate

Martin Marprelate (sometimes printed as Martin Mar-prelate and Marre–Martin) was the name used by the anonymous author or authors of the seven Marprelate tracts that circulated illegally in England in the years 1588 and 1589. Their principal f ...

controversy. Martin Marprelate was the name used by the anonymous author or authors of the illegal tracts attacking the Church published between 1588 and 1589. A number of commentators, including Grant McColley, have suggested that Godwin strongly objected to the imposition of censorship, expressed in Gonsales's hope that the publication of his account may not prove "prejudicial to the Catholic faith". John Clark has suggested that the Martin Marprelate controversy may have inspired Godwin to give the name Martin to the Lunars' god, but as a bishop of the Church of England it is perhaps unlikely that he was generally sympathetic to the Martin Marprelate position. Critics do not agree on the precise denomination of Godwin's Lunars. In contrast with Clark and Poole, David Cressy David Cressy is a British-born historian and Humanities Distinguished Professor of History, formerly at The Ohio State University. His specialty is the social history of early modern England, a topic on which he has published a number of monographs ...

argues that the Lunars falling to their knees after Gonsales's exclamation (a similar ritual takes place at the court of Irdonozur) is evidence of "a fairly mechanical form of religion (as most of Godwin's Protestant contemporaries judged Roman Catholicism)".

By the time ''The Man in the Moone'' was published, discussion on the plurality of worlds had begun to favour the possibility of extraterrestrial life. For Christian thinkers such a plurality is intimately connected to Christ and his redemption of man: if there are other worlds, do they share a similar history, and does Christ also redeem them in his sacrifice? According to Philipp Melanchthon

Philip Melanchthon. (born Philipp Schwartzerdt; 16 February 1497 – 19 April 1560) was a German Lutheran reformer, collaborator with Martin Luther, the first systematic theologian of the Protestant Reformation, intellectual leader of the Lu ...

, a 16th-century theologian who worked closely with Martin Luther

Martin Luther (; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, theologian, author, hymnwriter, and professor, and Order of Saint Augustine, Augustinian friar. He is the seminal figure of the Reformation, Protestant Refo ...

, "It must not be imagined that there are many worlds, because it must not be imagined that Christ died or was resurrected more often, nor must it be thought that in any other world without the knowledge of the son of God, that men would be restored to eternal life". Similar comments were made by Calvinist

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John Ca ...

theologian Lambert Daneau

Lambert Daneau (c. 1530 – c. 1590) was a French jurist and Calvinist theologian.

Life

He was born at Beaugency-sur-Loire, and educated at Orléans. He studied Greek under Adrianus Turnebus, and then law in Orléans from 1553. He moved to Bourges ...

. Midway through the 17th century the matter appears to have been settled in favour of a possible plurality, which was accepted by Henry More and Aphra Behn

Aphra Behn (; bapt. 14 December 1640 – 16 April 1689) was an English playwright, poet, prose writer and translator from the Restoration era. As one of the first English women to earn her living by her writing, she broke cultural barrie ...

among others; "by 1650, the Elizabethan Oxford examination question ''an sint plures mundi?'' ('can these be many worlds?' – to which the correct Aristotelian answer was 'no') had been replaced by the disputation thesis ''quod Luna sit habitabilis'' ('that the moon could be habitable' – which might be answered 'probably' if not 'yes')".

Lunar language

Godwin had a lifelong interest in language and communication (as is evident in Gonsales's various means of communicating with his servant Diego on St Helena), and this was the topic of his ''Nuncius inanimatus'' (1629). The language Gonsales encounters on the Moon bears no relation to any he is familiar with, and it takes him months to acquire sufficient fluency to communicate properly with the inhabitants. While its vocabulary appears limited, its possibilities for meaning are multiplied since the meaning of words and phrases also depends on tone. Invented languages were an important element of earlier fantastical accounts such as Thomas More's ''

Godwin had a lifelong interest in language and communication (as is evident in Gonsales's various means of communicating with his servant Diego on St Helena), and this was the topic of his ''Nuncius inanimatus'' (1629). The language Gonsales encounters on the Moon bears no relation to any he is familiar with, and it takes him months to acquire sufficient fluency to communicate properly with the inhabitants. While its vocabulary appears limited, its possibilities for meaning are multiplied since the meaning of words and phrases also depends on tone. Invented languages were an important element of earlier fantastical accounts such as Thomas More's ''Utopia

A utopia ( ) typically describes an imaginary community or society that possesses highly desirable or nearly perfect qualities for its members. It was coined by Sir Thomas More for his 1516 book ''Utopia (book), Utopia'', describing a fictional ...

'', François Rabelais

François Rabelais ( , , ; born between 1483 and 1494; died 1553) was a French Renaissance writer, physician, Renaissance humanist, monk and Greek scholar. He is primarily known as a writer of satire, of the grotesque, and of bawdy jokes and ...

's ''Gargantua and Pantagruel

''The Life of Gargantua and of Pantagruel'' (french: La vie de Gargantua et de Pantagruel) is a pentalogy of novels written in the 16th century by François Rabelais, telling the adventures of two giants, Gargantua ( , ) and his son Pantagruel ...

'' and Joseph Hall's ''Mundus Alter et Idem

''Mundus alter et idem'' is a satirical dystopian novel written by Joseph Hall . The title has been translated into English as ''An Old World and a New'', ''The Discovery of a New World'', and ''Another World and Yet the Same''. Although the tex ...

'', all books that Godwin was familiar with. P. Cornelius, in a study of invented languages in imaginary travel accounts from the 17th and 18th centuries, proposes that a perfect, rationally organised language is indicative of the Enlightenment

Enlightenment or enlighten may refer to:

Age of Enlightenment

* Age of Enlightenment, period in Western intellectual history from the late 17th to late 18th century, centered in France but also encompassing (alphabetically by country or culture): ...

's rationalism

In philosophy, rationalism is the epistemological view that "regards reason as the chief source and test of knowledge" or "any view appealing to reason as a source of knowledge or justification".Lacey, A.R. (1996), ''A Dictionary of Philosophy' ...

. As H. Neville Davies argues, Godwin's imaginary language is more perfect than for instance More's in one aspect: it is spoken on the entire Moon and has not suffered from the Earthly dispersion of languages caused by the fall of the Tower of Babel

The Tower of Babel ( he, , ''Mīgdal Bāḇel'') narrative in Genesis 11:1–9 is an origin myth meant to explain why the world's peoples speak different languages.

According to the story, a united human race speaking a single language and mi ...

.

One of Godwin's sources for his Lunar language was Trigault's ''De Christiana expeditione apud Sinas''. Gonsales provides two examples of spoken phrases, written down in a cipher

In cryptography, a cipher (or cypher) is an algorithm for performing encryption or decryption—a series of well-defined steps that can be followed as a procedure. An alternative, less common term is ''encipherment''. To encipher or encode i ...

later explained by John Wilkins in ''Mercury, or The Secret and Swift Messenger'' (1641). Trigault's account of the Chinese language gave Godwin the idea of assigning tonality to the Lunar language, and of appreciating it in the language spoken by the Chinese mandarins Gonsales encounters after his return to Earth. Gonsales claims that in contrast to the multitude of languages in China (making their speakers mutually unintelligible), the mandarins' language is universal by virtue of tonality (he suppresses it in the other varieties of Chinese

Chinese, also known as Sinitic, is a branch of the Sino-Tibetan language family consisting of hundreds of local varieties, many of which are not mutually intelligible. Variation is particularly strong in the more mountainous southeast of main ...

). Thus the mandarins are able to maintain a cultural and spiritual superiority resembling that of the Lunar upper class, which is to be placed in contrast with the variety of languages spoken in a fractured and morally degenerate Europe and elsewhere. Knowlson argues that using the term "language" is overstating the case, and that cipher is the proper term: "In spite of Godwin's claims, this musical 'language' is not in fact a language at all, but simply a cipher in which the letters of an existing language may be transcribed". He suggests Godwin's source may have been a book by Joan Baptista Porta, whose ''De occultis literarum notis'' (1606) contains "an exact description of the method he was to adopt".

Genre

The book's genre has been variously categorised. When it was first published the literary genre of utopian fantasy was in its infancy, and critics have recognised how Godwin used a utopian setting to criticise the institutions of his time: the Moon was "the ideal perspective from which to view the earth" and its "moral attitudes and social institutions," according to Maurice Bennett. Other critics have referred to the book as "utopia", "Renaissance utopia" or "picaresque adventure". While some critics claim it as one of the first works of science fiction, there is no general agreement that it is even "proto-science-fiction". Early commentators recognised that the book is a kind of picaresque novel, and comparisons with '' Don Quixote'' were being made as early as 1638. In structure as well as content ''The Man in the Moone'' somewhat resembles the anonymous Spanish novella ''Lazarillo de Tormes

''The Life of Lazarillo de Tormes and of His Fortunes and Adversities'' ( es, La vida de Lazarillo de Tormes y de sus fortunas y adversidades ) is a Spanish novella, published anonymously because of its anticlerical content. It was published s ...

'' (1554); both books begin with a genealogy and start out in Salamanca, featuring a man who travels from master to master seeking his fortune. But most critics agree that the picaresque mode is not sustained throughout, and that Godwin intentionally achieves a "generic transformation".

Godwin's book follows a venerable tradition of travel literature that blends the excitement of journeys to foreign places with utopian reflection; More's ''Utopia'' is cited as a forerunner, as is the account of Amerigo Vespucci. Godwin could fall back on an extensive body of work describing the voyages undertaken by his protagonist, including books by Hakluyt and Jan Huyghen van Linschoten, and the narratives deriving from the Jesuit mission in Beijing.

Reception and influence

''The Man in the Moone'' was published five months after ''The Discovery of a World in the Moone'' by John Wilkins, later bishop of Chester. Wilkins refers to Godwin once, in a discussion of spots in the Moon, but not to Godwin's book. In the third edition of ''The Discovery'' (1640), however, Wilkins provides a summary of Godwin's book, and later in ''Mercury'' (1641) he comments on ''The Man in the Moone'' and ''Nuncius Inanimatus'', saying that "the former text could be used to unlock the secrets of the latter". ''The Man in the Moone'' quickly became an international "source of humour and parody": Cyrano de Bergerac, using Baudoin's 1648 translation, parodied it in '' L'Autre Monde: où les États et Empires de la Lune'' (1657); Cyrano's traveller actually meets Gonsales, who is still on the Moon, "degraded to the status of pet monkey". It was one of the inspirations for what has been called the first science fiction text in the Americas, ''Syzygies and Lunar Quadratures Aligned to the Meridian of Mérida of the Yucatán by an Anctitone or Inhabitant of the Moon ...'' by Manuel Antonio de Rivas (1775). The Laputan language ofJonathan Swift

Jonathan Swift (30 November 1667 – 19 October 1745) was an Anglo-Irish Satire, satirist, author, essayist, political pamphleteer (first for the Whig (British political party), Whigs, then for the Tories (British political party), Tories), poe ...

, who was a distant relation of Godwin's, may have been influenced by ''The Man in the Moone'', either directly or through Cyrano de Bergerac.

''The Man in the Moone'' became a popular source for "often extravagantly staged comic drama and opera", including Aphra Behn's ''The Emperor of the Moon

''The Emperor of the Moon'' is a Restoration farce written by Aphra Behn in 1687, based on Italian commedia dell'arte. It was Behn's second most successful play (after '' The Rover''), probably due to the lightness of the plot and its accompan ...

'', a 1687 play "inspired by ... the third edition of 'The Man in the Moone'' and the English translation of Cyrano's work", and Elkanah Settle

Elkanah Settle (1 February 1648 – 12 February 1724) was an England, English poet and playwright.

Biography

He was born at Dunstable, and entered Trinity College, Oxford, in 1666, but left without taking a degree. His first tragedy, ''Cambyses, ...

s ''The World in the Moon'' (1697). Thomas D'Urfeys ''Wonders in the Sun, or the Kingdom of the Birds'' (1706) was "really a sequel, starring Domingo and Diego". Its popularity was not limited to English; a Dutch farce, ''Don Domingo Gonzales of de Man in de maan'', formerly considered to have been written by Maria de Wilde

Maria de Wilde (7 January 1682 – 11 April 1729) was a Dutch engraver and playwright of the Dutch Republic. She was born and died in Amsterdam, where she played an active part in the upper-class bourgeois world of artists and writers, and gained ...

, was published in 1755.

The book's influence continued into the 19th century. Edgar Allan Poe

Edgar Allan Poe (; Edgar Poe; January 19, 1809 – October 7, 1849) was an American writer, poet, editor, and literary critic. Poe is best known for his poetry and short stories, particularly his tales of mystery and the macabre. He is wide ...

in an appendix to "The Unparalleled Adventure of One Hans Pfaall

"The Unparalleled Adventure of One Hans Pfaall" (1835) is a short story by Edgar Allan Poe published in the June 1835 issue of the monthly magazine ''Southern Literary Messenger'' as "Hans Phaall -- A Tale", intended by Poe to be a hoax.

The stor ...

" called it "a singular and somewhat ingenious little book". Poe assumed the author to be French, an assumption also made by Jules Verne

Jules Gabriel Verne (;''Longman Pronunciation Dictionary''. ; 8 February 1828 – 24 March 1905) was a French novelist, poet, and playwright. His collaboration with the publisher Pierre-Jules Hetzel led to the creation of the ''Voyages extraor ...

in his '' From the Earth to the Moon'' (1865), suggesting that they may have been using Baudoin's translation. H. G. Wells

Herbert George Wells"Wells, H. G."

Revised 18 May 2015. ''

Revised 18 May 2015. ''

The First Men in the Moon'' (1901) has several parallels with Godwin's fantasy, including the use of a stone to induce weightlessness. But ''The Man in the Moone'' has nevertheless been given only "lukewarm consideration in different histories of English literature", and its importance is downplayed in studies of Utopian literature. Frank E. Manuel and Fritzie P. Manuel's ''Utopian Thought in the Western World'' (winner of the 1979 National Book Award for Nonfiction) mentions it only in passing, saying that Godwin "treats primarily of the mechanics of flight with the aid of a crew of birds", and that ''The Man in the Moone'', like Bergerac's and Wilkins's books, lacks "high seriousness and unified moral purpose".

Gonsales's load-carrying birds have also left their mark. The ''

A 1740 plate based on the book's illustration

held by the

Oxford English Dictionary

The ''Oxford English Dictionary'' (''OED'') is the first and foundational historical dictionary of the English language, published by Oxford University Press (OUP). It traces the historical development of the English language, providing a com ...

''s entry for ''gansa'' reads "One of the birds (called elsewhere 'wild swans') which drew Domingo Gonsales to the Moon in the romance by Bp. F. Godwin". For the etymology it suggests ''ganzæ'', found in Philemon Holland's 1601 translation of Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/2479), called Pliny the Elder (), was a Roman author, naturalist and natural philosopher, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the emperor Vespasian. He wrote the encyclopedic '' ...

s '' Natural History''. Michael van Langren ("Langrenus"), the 17th-century Dutch astronomer and cartographer, named one of the lunar craters for them, ''Gansii'', later renamed Halley.

Modern editions

* ''The Man in the Moone: or a Discourse of a Voyage thither by Domingo Gonsales'', 1638. Facsimile reprint, Scolar Press, 1971. * ''The Man in the Moone and Nuncius Inanimatus'', ed. Grant McColley. Smith College Studies in Modern Languages 19. 1937. Repr. Logaston Press, 1996. * ''The Man in the Moone. A Story of Space Travel in the Early 17th Century'', 1959. * ''The Man in the Moone'', in Charles C. Mish, ''Short Fiction of the Seventeenth Century'', 1963. Based on the second edition, with modernised text (an "eccentric choice"). * ''The Man in the Moone'', in Faith K. Pizor and T. Allan Comp, eds., ''The Man in the Moone and Other Lunar Fantasies''. Praeger, 1971. * ''The Man in the Moone'', ed. William Poole. Broadview, 2009. .Monographs on ''The Man in the Moone''

* Anke Janssen, ''Francis Godwins "The Man in the Moone": Die Entdeckung des Romans als Medium der Auseinandersetzung mit Zeitproblemen''. Peter Lang, 1981.References

Notes

Citations

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* *External links

* * * *A 1740 plate based on the book's illustration

held by the

Fitzwilliam Museum

The Fitzwilliam Museum is the art and antiquities museum of the University of Cambridge. It is located on Trumpington Street opposite Fitzwilliam Street in central Cambridge. It was founded in 1816 under the will of Richard FitzWilliam, 7th Vis ...

{{DEFAULTSORT:Man in the Moone

1638 novels

English novels

1630s science fiction novels

British science fiction novels

English science fiction novels

Space exploration novels

English-language novels

Novels set on the Moon

Novels published posthumously

17th-century English novels

Works published under a pseudonym

Novels adapted into operas