The Inquiry on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

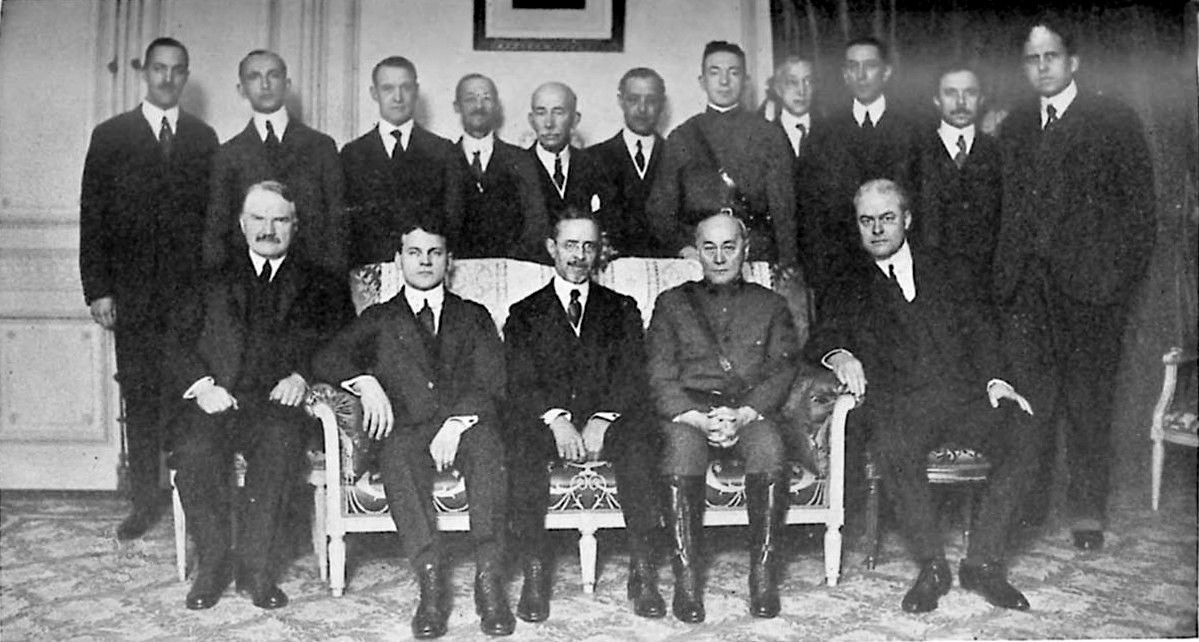

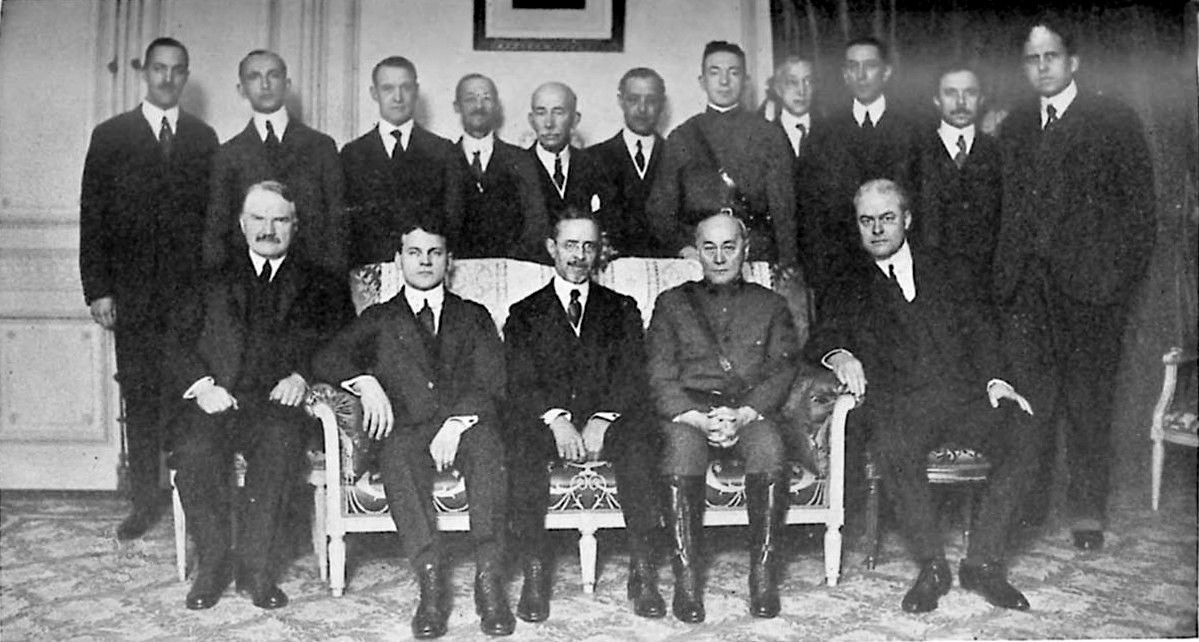

The Inquiry was a study group established in September 1917 by

The Inquiry was a study group established in September 1917 by

The Inquiry was a study group established in September 1917 by

The Inquiry was a study group established in September 1917 by Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

to prepare materials for the peace negotiations following World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. The group, composed of around 150 academics, was directed by the presidential adviser Edward House and supervised directly by the philosopher Sidney Mezes. The Heads of Research were Walter Lippmann

Walter Lippmann (September 23, 1889 – December 14, 1974) was an American writer, reporter, and political commentator. With a career spanning 60 years, he is famous for being among the first to introduce the concept of the Cold War, coining t ...

and his successor Isaiah Bowman

Isaiah Bowman, AB, Ph. D. (December 26, 1878 – January 6, 1950), was an American geographer and President of the Johns Hopkins University, 1935–1948, controversial for his antisemitism and inaction in Jewish resettlement during World War ...

. The group first worked out of the New York Public Library

The New York Public Library (NYPL) is a public library system in New York City. With nearly 53 million items and 92 locations, the New York Public Library is the second-largest public library in the United States behind the Library of Congress a ...

but later worked from the offices of the American Geographical Society

The American Geographical Society (AGS) is an organization of professional geographers, founded in 1851 in New York City. Most fellows of the society are United States, Americans, but among them have always been a significant number of fellows f ...

of New York once Bowman had joined the group.

Mezes's senior colleagues were the geographer Isaiah Bowman

Isaiah Bowman, AB, Ph. D. (December 26, 1878 – January 6, 1950), was an American geographer and President of the Johns Hopkins University, 1935–1948, controversial for his antisemitism and inaction in Jewish resettlement during World War ...

, the historian and librarian Archibald Cary Coolidge

Archibald Cary Coolidge (March 6, 1866 – January 14, 1928) was an American educator and diplomat. He was a professor of history at Harvard College from 1908 and the first director of the Harvard University Library from 1910 until his death. Co ...

, the historian James Shotwell, and the lawyer David Hunter Miller

David Hunter Miller (1875–1961) was a US lawyer and an expert on treaties who participated in the drafting of the covenant of the League of Nations.

He practiced law in New York City from 1911 to 1929; served on the Inquiry, a body of exp ...

. Progressive confidants who were consulted on staffing but did not contribute directly to the administration or reports of the group included James Truslow Adams, Louis Brandeis

Louis Dembitz Brandeis ( ; November 13, 1856 – October 5, 1941) was an American lawyer who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, associate justice on the Supreme Court of the United States from 1916 to ...

, Abbott Lawrence Lowell

Abbott Lawrence Lowell (December 13, 1856 – January 6, 1943) was an American educator and legal scholar. He was president of Harvard University from 1909 to 1933.

With an "aristocratic sense of mission and self-certainty," Lowell cut a large ...

, and Walter Weyl.

Twenty-one members of The Inquiry, later integrated into the larger American Commission to Negotiate Peace

The American Commission to Negotiate Peace, successor to The Inquiry, participated in the peace negotiations at the Treaty of Versailles from January 18 to December 9, 1919. Frank Lyon Polk headed the commission in late 1919. The peace conferen ...

, traveled to the Paris Peace Conference in January 1919 and accompanied Wilson aboard USS ''George Washington'' to France.

Also included in the group were such academics as Paul Monroe, a professor of history at Columbia University

Columbia University in the City of New York, commonly referred to as Columbia University, is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Churc ...

and a key member of the Research Division who drew on his experience in the Philippines

The Philippines, officially the Republic of the Philippines, is an Archipelagic state, archipelagic country in Southeast Asia. Located in the western Pacific Ocean, it consists of List of islands of the Philippines, 7,641 islands, with a tot ...

to assess the educational needs of developing areas such as Albania

Albania ( ; or ), officially the Republic of Albania (), is a country in Southeast Europe. It is located in the Balkans, on the Adriatic Sea, Adriatic and Ionian Seas within the Mediterranean Sea, and shares land borders with Montenegro to ...

, Turkey

Turkey, officially the Republic of Türkiye, is a country mainly located in Anatolia in West Asia, with a relatively small part called East Thrace in Southeast Europe. It borders the Black Sea to the north; Georgia (country), Georgia, Armen ...

, and Central Africa

Central Africa (French language, French: ''Afrique centrale''; Spanish language, Spanish: ''África central''; Portuguese language, Portuguese: ''África Central'') is a subregion of the African continent comprising various countries accordin ...

, and Frank A. Golder, a history professor from Washington State University

Washington State University (WSU, or colloquially Wazzu) is a Public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Pullman, Washington, United States. Founded in 1890, WSU is also one of the oldest Land-grant uni ...

, who specialized in the diplomatic history of Russia and wrote papers on Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the List of European countries by area, second-largest country in Europe after Russia, which Russia–Ukraine border, borders it to the east and northeast. Ukraine also borders Belarus to the nor ...

, Lithuania

Lithuania, officially the Republic of Lithuania, is a country in the Baltic region of Europe. It is one of three Baltic states and lies on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea, bordered by Latvia to the north, Belarus to the east and south, P ...

, Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

, and Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

.

Recommendations

The Inquiry provided various recommendations for the countries which it surveyed. Specifically, the recommendations discussed the ideal borders for various countries as well as various other conditions that were felt necessary to achieve a lasting peace free of tensions.France, Belgium, Luxembourg, and Denmark

The Inquiry recommendedAlsace–Lorraine

Alsace–Lorraine (German language, German: ''Elsaß–Lothringen''), officially the Imperial Territory of Alsace–Lorraine (), was a territory of the German Empire, located in modern-day France. It was established in 1871 by the German Empire ...

be returned to France, the parts of the Saarland

Saarland (, ; ) is a state of Germany in the southwest of the country. With an area of and population of 990,509 in 2018, it is the smallest German state in area apart from the city-states of Berlin, Bremen, and Hamburg, and the smallest in ...

, which France had controlled before 1815, to be returned to it, and the Rhineland

The Rhineland ( ; ; ; ) is a loosely defined area of Western Germany along the Rhine, chiefly Middle Rhine, its middle section. It is the main industrial heartland of Germany because of its many factories, and it has historic ties to the Holy ...

to be demilitarized. In regards to Belgium, it was recommended for Belgium's neutral status to be abolished and for Belgium to be allowed to annex some territory in the Maastricht

Maastricht ( , , ; ; ; ) is a city and a Municipalities of the Netherlands, municipality in the southeastern Netherlands. It is the capital city, capital and largest city of the province of Limburg (Netherlands), Limburg. Maastricht is loca ...

and Malmedy

Malmedy (; , historically also ; ) is a city and municipality of Wallonia located in the province of Liège, Belgium.

On January 1, 2018, Malmedy had a total population of 12,654. The total area is 99.96 km2 which gives a population dens ...

regions for strategic (in the case of Maastricht) and ethnic (in the case of Malmedy) reasons. As for Luxembourg, it was recommended for it to be annexed to Belgium or to have its independence restored. Meanwhile, there should be a plebiscite

A referendum, plebiscite, or ballot measure is a direct vote by the electorate (rather than their representatives) on a proposal, law, or political issue. A referendum may be either binding (resulting in the adoption of a new policy) or adv ...

in northern Schleswig

Northern may refer to the following:

Geography

* North, a point in direction

* Northern Europe, the northern part or region of Europe

* Northern Highland, a region of Wisconsin, United States

* Northern Province, Sri Lanka

* Northern Range, a ra ...

, and the area should be transferred from Germany to Denmark if the region's people preferred.

Russia, Poland, and the former Russian Empire

The Inquiry suggested that if it was possible for Russia to become a genuine federal and democratic state, theBaltic states

The Baltic states or the Baltic countries is a geopolitical term encompassing Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. All three countries are members of NATO, the European Union, the Eurozone, and the OECD. The three sovereign states on the eastern co ...

(with the possible exception of Lithuania

Lithuania, officially the Republic of Lithuania, is a country in the Baltic region of Europe. It is one of three Baltic states and lies on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea, bordered by Latvia to the north, Belarus to the east and south, P ...

) and Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the List of European countries by area, second-largest country in Europe after Russia, which Russia–Ukraine border, borders it to the east and northeast. Ukraine also borders Belarus to the nor ...

should be encouraged to reunify with Russia because of the belief that it would best serve the economic interests of everyone involved. Meanwhile, if the Bolsheviks maintained their control of Russia, the Inquiry suggested for the independence of the Baltic states and Ukraine to be recognized if a referendum on reunion with Russia was held in those territories at some future better time. As for the borders of Ukraine, Latvia, and Estonia, the borders that were proposed for them were very similar to the borders that these countries ended up with after 1991. Indeed, the Inquiry even suggested that Crimea

Crimea ( ) is a peninsula in Eastern Europe, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, almost entirely surrounded by the Black Sea and the smaller Sea of Azov. The Isthmus of Perekop connects the peninsula to Kherson Oblast in mainland Ukrain ...

should be given to Ukraine.

Regarding Finland, the Inquiry expressed its support for its independence and also unsuccessfully expressed a desire to see Åland

Åland ( , ; ) is an Federacy, autonomous and Demilitarized zone, demilitarised region of Finland. Receiving its autonomy by a 1920 decision of the League of Nations, it is the smallest region of Finland by both area () and population (30,54 ...

transferred from Finland to Sweden. It was recommended for an independent Poland to be created out of all indisputably-Polish areas, Poland and Lithuania to unite if possible, and Poland to "be given secure and unhampered access to the Baltic ea by the creation of a Polish Corridor. While acknowledging that it would be unfortunate to separate East Prussia

East Prussia was a Provinces of Prussia, province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1772 to 1829 and again from 1878 (with the Kingdom itself being part of the German Empire from 1871); following World War I it formed part of the Weimar Republic's ...

, with its 1,600,000 Germans, from the rest of Germany, the Inquiry considered that to be the lesser evil than denying Poland, nation of 20,000,000 people, access to the sea. In addition, the Inquiry expressed confidence that Germany could easily be assured railroad transit across the Polish Corridor. As for Poland's eastern borders, the Inquiry kept the door option to a Polish annexation of eastern Galicia and Belarusian-majority territories to its north.

In the Caucasus, the Inquiry suggested giving independence to Armenia in the borders of Wilsonian Armenia

Wilsonian Armenia () was the unimplemented boundary configuration of the First Republic of Armenia in the Treaty of Sèvres, as drawn by President of the United States, U.S. President Woodrow Wilson, Woodrow Wilson's United States State Departm ...

and provisional independence to both Georgia and Azerbaijan. In addition, the idea of a future union of Armenia, Georgia, and Azerbaijan (in the form of a Transcaucasian Federation) was discussed and looked at favorably by the Inquiry.

Czechoslovakia, Romania, Yugoslavia, and Italy

It was suggested for Czechoslovakia to be created out of the Czech-majority and Slovak-majority areas of the former Austria-Hungary. In addition, it was suggested for Czechoslovakia to include both theSudetenland

The Sudetenland ( , ; Czech and ) is a German name for the northern, southern, and western areas of former Czechoslovakia which were inhabited primarily by Sudeten Germans. These German speakers had predominated in the border districts of Bohe ...

and Subcarpathian Ruthenia and more than 500,000 Hungarians (Magyars) south of Slovakia.

As for Romania, the Inquiry advised to allow it to annex all of Bessarabia

Bessarabia () is a historical region in Eastern Europe, bounded by the Dniester river on the east and the Prut river on the west. About two thirds of Bessarabia lies within modern-day Moldova, with the Budjak region covering the southern coa ...

, the Romanian-majority part of Bukovina

Bukovina or ; ; ; ; , ; see also other languages. is a historical region at the crossroads of Central and Eastern Europe. It is located on the northern slopes of the central Eastern Carpathians and the adjoining plains, today divided betwe ...

, all of Transylvania

Transylvania ( or ; ; or ; Transylvanian Saxon dialect, Transylvanian Saxon: ''Siweberjen'') is a List of historical regions of Central Europe, historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and ...

, the Romanian-majority areas in Hungary proper, and about two thirds of the Banat

Banat ( , ; ; ; ) is a geographical and Historical regions of Central Europe, historical region located in the Pannonian Basin that straddles Central Europe, Central and Eastern Europe. It is divided among three countries: the eastern part lie ...

. In addition, the Inquiry suggested having Romania cede Southern Dobruja

Southern Dobruja or South Dobruja ( or simply , ; or , ), also the Quadrilateral (), is an area of north-eastern Bulgaria comprising Dobrich and Silistra provinces, part of the historical region of Dobruja. It has an area of 7,412 square km an ...

to Bulgaria, which ultimately occurred in 1940. Meanwhile, it was suggested for an "independent federated Yugo-Slav state" to be created out of Serbia; Montenegro; and the Serbian, Croatian, and Slovenian territories of the former Austria-Hungary.

The Inquiry acknowledged that the Brenner Pass

The Brenner Pass ( , shortly ; ) is a mountain pass over the Alps which forms the Austria-Italy border, border between Italy and Austria. It is one of the principal passes of the Alps, major passes of the Eastern Alpine range and has the lowes ...

, which had been promised to Italy in the 1915 Treaty of London, would give Italy the best strategic frontier, but it recommended a line somewhat to the south of it to reduce the number of ethnic Germans who would be put inside of Italy and still give Italy a more defensible border in the north than it had had before World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. In addition, it was suggested for Italy to be allowed to annex Istria

Istria ( ; Croatian language, Croatian and Slovene language, Slovene: ; Italian language, Italian and Venetian language, Venetian: ; ; Istro-Romanian language, Istro-Romanian: ; ; ) is the largest peninsula within the Adriatic Sea. Located at th ...

, with its large number of ethnic Italians, but not Italian-majority Fiume because of its importance to Yugoslavia. In addition, the Inquiry advised that Italy should end its occupation of Rhodes and the Dodecanese Islands and give the islands to Greece, in accordance with the wishes of their inhabitants, something that was done but only in 1947, after the end of World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. Also, the Inquiry recommended for Italian Libya

Libya (; ) was a colony of Fascist Italy (1922–1943), Italy located in North Africa, in what is now modern Libya, between 1934 and 1943. It was formed from the unification of the colonies of Italian Cyrenaica, Cyrenaica and Italian Tripolitan ...

to "be given a hinterland adequate for access to the Sudan and its trade."

German Austria and Hungary

It was recommended for German Austria, which was later renamed theRepublic of Austria

Austria, formally the Republic of Austria, is a landlocked country in Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine Federal states of Austria, states, of which the capital Vienna is the List of largest cities in Aust ...

, to be established as an independent state and be given an outlet for trade at Trieste, Fiume, or both cities. Meanwhile, it was suggested for Hungary to be given independence with borders very similar to the ones that it ultimately ended up getting by the Treaty of Trianon

The Treaty of Trianon (; ; ; ), often referred to in Hungary as the Peace Dictate of Trianon or Dictate of Trianon, was prepared at the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace Conference. It was signed on the one side by Hungary ...

and for it to be given also an outlet for trade at either Trieste or Fiume as well as "rights of unrestricted commerce on the lower Danube

The Danube ( ; see also #Names and etymology, other names) is the List of rivers of Europe#Longest rivers, second-longest river in Europe, after the Volga in Russia. It flows through Central and Southeastern Europe, from the Black Forest sou ...

." As for the German-majority Burgenland

Burgenland (; ; ; Bavarian language, Austro-Bavarian: ''Burgnland''; Slovene language, Slovene: ''Gradiščanska''; ) is the easternmost and least populous Bundesland (Austria), state of Austria. It consists of two statutory city (Austria), statut ...

, the Inquiry advised to keep it inside of Hungary, at least until it became clear that the people there indeed desired union with Austria, to avoid "disturb nglong-established institutions."

Albania, Constantinople, the Straits, and the Middle East

No specific recommendations were given for Albania because of the extremely complex nature of the situation there. As for Constantinople, it was suggested for an internationalized state to be created there and for the Bosporus, Sea of Marmara, and the Dardanelles to be permanently open to ships and commercial vessels of all countries with international guarantees to uphold that. Meanwhile, in regards to Anatolia, it was advised for an independent Turkish Anatolian state to be created under aLeague of Nations mandate

A League of Nations mandate represented a legal status under international law for specific territories following World War I, involving the transfer of control from one nation to another. These mandates served as legal documents establishing th ...

, with the Great Power in charge of the mandate being determined later.

Also, the Inquiry suggested for independent Mesopotamian and Syrian states to be created under a League of Nations mandate, with the decision as to the great powers in charge of the mandates being reserved for later. The proposed Syrian state would consist of territories that are now part of Lebanon, northern Jordan, and western Syria. Meanwhile, the proposed Mesopotamian state would consist of territories that are now part of Iraq and northeastern Syria. In addition, it was advised to keep open the option of the creation of an Arab confederation that would include Mesopotamia and Syria.

As for Palestine, it was advised for an independent state under a British mandate for Palestine

The Mandate for Palestine was a League of Nations mandate for British administration of the territories of Palestine and Transjordanwhich had been part of the Ottoman Empire for four centuriesfollowing the defeat of the Ottoman Empire in Wo ...

to be created. Jews would be invited to return to Palestine and settle there if the protection of the personal, religious, and property rights of the non-Jewish population are assured, and the state's holy sites would be under the protection of the League of Nations. The League of Nations was to recognize Palestine as a Jewish state as soon as it was in fact.

In regards to Arabia

The Arabian Peninsula (, , or , , ) or Arabia, is a peninsula in West Asia, situated north-east of Africa on the Arabian plate. At , comparable in size to India, the Arabian Peninsula is the largest peninsula in the world.

Geographically, the ...

, it was suggested for the King of Hejaz not to be given assistance to impose his rule over unwilling Arab tribes.

Legacy

Some of the members later established theCouncil on Foreign Relations

The Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) is an American think tank focused on Foreign policy of the United States, U.S. foreign policy and international relations. Founded in 1921, it is an independent and nonpartisan 501(c)(3) nonprofit organi ...

, which is independent of the government.

The Inquiry's papers are currently stored at the National Archives

National archives are the archives of a country. The concept evolved in various nations at the dawn of modernity based on the impact of nationalism upon bureaucratic processes of paperwork retention.

Conceptual development

From the Middle Ages i ...

, though some of their papers (in many cases, duplicates) are stored at the Yale

Yale University is a private Ivy League research university in New Haven, Connecticut, United States. Founded in 1701, Yale is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States, and one of the nine colonial colleges ch ...

Archives.

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Inquiry Organizations established in 1917