The Council on Foreign Relations on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) is an American think tank specializing in U.S.

As a result of discussions at the Peace Conference, a small group of British and American diplomats and scholars met on May 30, 1919, at the Hotel Majestic in Paris. They decided to create an Anglo-American organization called "The Institute of International Affairs", which would have offices in London and New York. Ultimately, the British and American delegates formed separate institutes, with the British developing the Royal Institute of International Affairs (known as Chatham House) in London. Due to the isolationist views prevalent in American society at that time, the scholars had difficulty gaining traction with their plan and turned their focus instead to a set of discreet meetings which had been taking place since June 1918 in New York City, under the name "Council on Foreign Relations". The meetings were headed by corporate lawyer

As a result of discussions at the Peace Conference, a small group of British and American diplomats and scholars met on May 30, 1919, at the Hotel Majestic in Paris. They decided to create an Anglo-American organization called "The Institute of International Affairs", which would have offices in London and New York. Ultimately, the British and American delegates formed separate institutes, with the British developing the Royal Institute of International Affairs (known as Chatham House) in London. Due to the isolationist views prevalent in American society at that time, the scholars had difficulty gaining traction with their plan and turned their focus instead to a set of discreet meetings which had been taking place since June 1918 in New York City, under the name "Council on Foreign Relations". The meetings were headed by corporate lawyer  The members were proponents of Wilson's internationalism, but they were particularly concerned about "the effect that the war and the treaty of peace might have on postwar business". The scholars from the inquiry saw an opportunity to create an organization that brought diplomats, high-level government officials, and academics together with lawyers, bankers, and industrialists to engineer government policy. On July 29, 1921, they filed a certification of

The members were proponents of Wilson's internationalism, but they were particularly concerned about "the effect that the war and the treaty of peace might have on postwar business". The scholars from the inquiry saw an opportunity to create an organization that brought diplomats, high-level government officials, and academics together with lawyers, bankers, and industrialists to engineer government policy. On July 29, 1921, they filed a certification of

cfr.org. Retrieved November 29, 2021. In 1922, Gay, who was a former dean of the

In 1922, Gay, who was a former dean of the

A critical study found that of 502 government officials surveyed from 1945 to 1972, more than half were members of the Council. During the

A critical study found that of 502 government officials surveyed from 1945 to 1972, more than half were members of the Council. During the  Dwight D. Eisenhower chaired a CFR study group while he served as President of Columbia University. One member later said, "whatever General Eisenhower knows about economics, he has learned at the study group meetings." The CFR study group devised an expanded study group called "Americans for Eisenhower" to increase his chances for the presidency. Eisenhower would later draw many Cabinet members from CFR ranks and become a CFR member himself. His primary CFR appointment was Secretary of State

Dwight D. Eisenhower chaired a CFR study group while he served as President of Columbia University. One member later said, "whatever General Eisenhower knows about economics, he has learned at the study group meetings." The CFR study group devised an expanded study group called "Americans for Eisenhower" to increase his chances for the presidency. Eisenhower would later draw many Cabinet members from CFR ranks and become a CFR member himself. His primary CFR appointment was Secretary of State

foreign policy

A State (polity), state's foreign policy or external policy (as opposed to internal or domestic policy) is its objectives and activities in relation to its interactions with other states, unions, and other political entities, whether bilaterall ...

and international relations. Founded in 1921, it is a nonprofit organization that is independent and nonpartisan

Nonpartisanism is a lack of affiliation with, and a lack of bias towards, a political party.

While an Oxford English Dictionary definition of ''partisan'' includes adherents of a party, cause, person, etc., in most cases, nonpartisan refers sp ...

. CFR is based in New York City, with an additional office in Massachusetts. Its membership has included senior politicians, numerous secretaries of state, CIA

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian intelligence agency, foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gat ...

directors, bankers, lawyers, professors, corporate directors and CEOs, and senior media figures.

CFR meetings convene government officials, global business leaders and prominent members of the intelligence and foreign-policy community to discuss international issues. CFR has published the bi-monthly journal ''Foreign Affairs

''Foreign Affairs'' is an American magazine of international relations and U.S. foreign policy published by the Council on Foreign Relations, a nonprofit, nonpartisan, membership organization and think tank specializing in U.S. foreign policy and ...

'' since 1922. It also runs the David Rockefeller Studies Program, which influences foreign policy by making recommendations to the presidential administration and diplomatic

Diplomatics (in American English, and in most anglophone countries), or diplomatic (in British English), is a scholarly discipline centred on the critical analysis of documents: especially, historical documents. It focuses on the conventions, p ...

community, testifying before Congress, interacting with the media, and publishing on foreign policy issues.

History

Origins, 1918 to 1945

Towards the end of World War I, a working fellowship of about 150 scholars called " The Inquiry" was tasked with briefing President Woodrow Wilson about options for the postwar world when Germany was defeated. This academic group, including Wilson's closest adviser and long-time friend "Colonel"Edward M. House

Edward Mandell House (July 26, 1858 – March 28, 1938) was an American diplomat, and an adviser to President Woodrow Wilson. He was known as Colonel House, although his rank was honorary and he had performed no military service. He was a highl ...

, as well as Walter Lippmann, met to assemble the strategy for the postwar world. The team produced more than 2,000 documents detailing and analyzing the political, economic, and social facts globally that would be helpful for Wilson in the peace talks. Their reports formed the basis for the Fourteen Points, which outlined Wilson's strategy for peace after the war's end. These scholars then traveled to the Paris Peace Conference 1919

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. Si ...

and participated in the discussions there.

As a result of discussions at the Peace Conference, a small group of British and American diplomats and scholars met on May 30, 1919, at the Hotel Majestic in Paris. They decided to create an Anglo-American organization called "The Institute of International Affairs", which would have offices in London and New York. Ultimately, the British and American delegates formed separate institutes, with the British developing the Royal Institute of International Affairs (known as Chatham House) in London. Due to the isolationist views prevalent in American society at that time, the scholars had difficulty gaining traction with their plan and turned their focus instead to a set of discreet meetings which had been taking place since June 1918 in New York City, under the name "Council on Foreign Relations". The meetings were headed by corporate lawyer

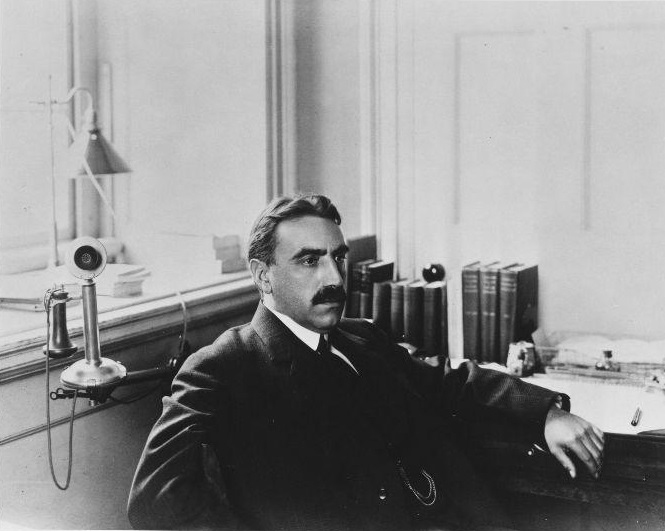

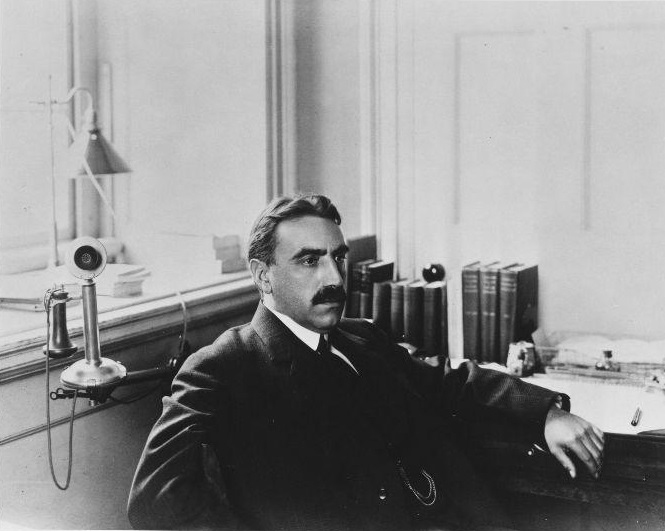

As a result of discussions at the Peace Conference, a small group of British and American diplomats and scholars met on May 30, 1919, at the Hotel Majestic in Paris. They decided to create an Anglo-American organization called "The Institute of International Affairs", which would have offices in London and New York. Ultimately, the British and American delegates formed separate institutes, with the British developing the Royal Institute of International Affairs (known as Chatham House) in London. Due to the isolationist views prevalent in American society at that time, the scholars had difficulty gaining traction with their plan and turned their focus instead to a set of discreet meetings which had been taking place since June 1918 in New York City, under the name "Council on Foreign Relations". The meetings were headed by corporate lawyer Elihu Root

Elihu Root (; February 15, 1845February 7, 1937) was an American lawyer, Republican politician, and statesman who served as Secretary of State and Secretary of War in the early twentieth century. He also served as United States Senator from N ...

, who had served as Secretary of State under President Theodore Roosevelt, and attended by 108 "high-ranking officers of banking, manufacturing, trading and finance companies, together with many lawyers".

The members were proponents of Wilson's internationalism, but they were particularly concerned about "the effect that the war and the treaty of peace might have on postwar business". The scholars from the inquiry saw an opportunity to create an organization that brought diplomats, high-level government officials, and academics together with lawyers, bankers, and industrialists to engineer government policy. On July 29, 1921, they filed a certification of

The members were proponents of Wilson's internationalism, but they were particularly concerned about "the effect that the war and the treaty of peace might have on postwar business". The scholars from the inquiry saw an opportunity to create an organization that brought diplomats, high-level government officials, and academics together with lawyers, bankers, and industrialists to engineer government policy. On July 29, 1921, they filed a certification of incorporation

Incorporation may refer to:

* Incorporation (business), the creation of a corporation

* Incorporation of a place, creation of municipal corporation such as a city or county

* Incorporation (academic), awarding a degree based on the student having ...

, officially forming the Council on Foreign Relations. Founding members included its first honorary president, Elihu Root

Elihu Root (; February 15, 1845February 7, 1937) was an American lawyer, Republican politician, and statesman who served as Secretary of State and Secretary of War in the early twentieth century. He also served as United States Senator from N ...

, and first elected president, John W. Davis, vice-president Paul D. Cravath

Paul Drennan Cravath (July 14, 1861 – July 1, 1940) was a prominent Manhattan lawyer and a Equity partner, partner of the New York law firm Cravath, Swaine & Moore. He devised the Cravath System, was a leader in the Atlanticism, Atlantist mov ...

, and secretary–treasurer Edwin F. Gay

Edwin Francis Gay (October 27, 1867 – February 8, 1946) was an American economist, Professor of Economic History and first Dean of the Harvard Business School.Morgen Witzel (2004) "Edwin Gay (1867-1946)" in: ''Fifty key figures in management''. ...

."Directors and Officers"cfr.org. Retrieved November 29, 2021.

In 1922, Gay, who was a former dean of the

In 1922, Gay, who was a former dean of the Harvard Business School

Harvard Business School (HBS) is the graduate business school of Harvard University, a private research university in Boston, Massachusetts. It is consistently ranked among the top business schools in the world and offers a large full-time MBA p ...

and director of the Shipping Board

The United States Shipping Board (USSB) was established as an emergency agency by the 1916 Shipping Act (39 Stat. 729), on September 7, 1916. The United States Shipping Board's task was to increase the number of US ships supporting the World War ...

during the war, spearheaded the Council's efforts to begin publication of a magazine that would be the "authoritative" source on foreign policy. He gathered US$125,000 () from the wealthy members on the council, as well as by sending letters soliciting funds to "the thousand richest Americans". Using these funds, the first issue of ''Foreign Affairs

''Foreign Affairs'' is an American magazine of international relations and U.S. foreign policy published by the Council on Foreign Relations, a nonprofit, nonpartisan, membership organization and think tank specializing in U.S. foreign policy and ...

'' was published in September 1922. Within a few years, it had gained a reputation as the "most authoritative American review dealing with international relations".

In the late 1930s, the Ford Foundation and Rockefeller Foundation

The Rockefeller Foundation is an American private foundation and philanthropic medical research and arts funding organization based at 420 Fifth Avenue, New York City. The second-oldest major philanthropic institution in America, after the Carneg ...

began contributing large amounts of money to the Council. In 1938, they created various Committees on Foreign Relations, which later became governed by the American Committees on Foreign Relations in Washington, D.C., throughout the country, funded by a grant from the Carnegie Corporation. Influential men were to be chosen in a number of cities, and would then be brought together for discussions in their own communities as well as participating in an annual conference in New York. These local committees served to influence local leaders and shape public opinion to build support for the Council's policies, while also acting as "useful listening posts" through which the Council and U.S. government could "sense the mood of the country".

Beginning in 1939, and lasting for five years, the Council achieved much greater prominence within the government and the State Department

The United States Department of State (DOS), or State Department, is an United States federal executive departments, executive department of the Federal government of the United States, U.S. federal government responsible for the country's fore ...

, when it established the strictly confidential '' War and Peace Studies'', funded entirely by the Rockefeller Foundation

The Rockefeller Foundation is an American private foundation and philanthropic medical research and arts funding organization based at 420 Fifth Avenue, New York City. The second-oldest major philanthropic institution in America, after the Carneg ...

. The secrecy surrounding this group was such that the Council members who were not involved in its deliberations were completely unaware of the study group's existence. It was divided into four functional topic groups: economic and financial; security and armaments; territorial; and political. The security and armaments group was headed by Allen Welsh Dulles

Allen Welsh Dulles (, ; April 7, 1893 – January 29, 1969) was the first civilian Director of Central Intelligence (DCI), and its longest-serving director to date. As head of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) during the early Cold War, he ...

, who later became a pivotal figure in the CIA

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian intelligence agency, foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gat ...

's predecessor, the Office of Strategic Services

The Office of Strategic Services (OSS) was the intelligence agency of the United States during World War II. The OSS was formed as an agency of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) to coordinate espionage activities behind enemy lines for all branc ...

(OSS). CFR ultimately produced 682 memoranda for the State Department, which were marked classified

Classified may refer to:

General

*Classified information, material that a government body deems to be sensitive

*Classified advertising or "classifieds"

Music

*Classified (rapper) (born 1977), Canadian rapper

*The Classified, a 1980s American roc ...

and circulated among the appropriate government departments.

Cold War era, 1945 to 1979

A critical study found that of 502 government officials surveyed from 1945 to 1972, more than half were members of the Council. During the

A critical study found that of 502 government officials surveyed from 1945 to 1972, more than half were members of the Council. During the Eisenhower administration

Dwight D. Eisenhower's tenure as the 34th president of the United States began with his first inauguration on January 20, 1953, and ended on January 20, 1961. Eisenhower, a Republican from Kansas, took office following a landslide victory ov ...

40% of the top U.S. foreign policy officials were CFR members (Eisenhower himself had been a council member); under Truman, 42% of the top posts were filled by council members. During the Kennedy administration, this number rose to 51%, and peaked at 57% under the Johnson administration.

In an anonymous piece called "The Sources of Soviet Conduct" that appeared in ''Foreign Affairs'' in 1947, CFR study group member George Kennan

George Frost Kennan (February 16, 1904 – March 17, 2005) was an American diplomat and historian. He was best known as an advocate of a policy of containment of Soviet expansion during the Cold War. He lectured widely and wrote scholarly histo ...

coined the term " containment". The essay would prove to be highly influential in US foreign policy for seven upcoming presidential administrations. Forty years later, Kennan explained that he had never suspected the Russians of any desire to launch an attack on America; he thought that it was obvious enough and he did not need to explain it in his essay. William Bundy

William Putnam Bundy (September 24, 1917 – October 6, 2000) was an American attorney and intelligence expert, an analyst with the CIA. Bundy served as a foreign affairs advisor to both presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson. He ha ...

credited CFR's study groups with helping to lay the framework of thinking that led to the Marshall Plan and NATO. Due to new interest in the group, membership grew towards 1,000.

John Foster Dulles

John Foster Dulles (, ; February 25, 1888 – May 24, 1959) was an American diplomat, lawyer, and Republican Party politician. He served as United States Secretary of State under President Dwight D. Eisenhower from 1953 to 1959 and was briefly ...

. Dulles gave a public address at the Harold Pratt House

The Harold Pratt House is a historic mansion located at 58 East 68th Street (at the corner of Park Avenue) on the Upper East Side of Manhattan in New York City. It serves as the headquarters of the Council on Foreign Relations think tank. The b ...

in New York City in which he announced a new direction for Eisenhower's foreign policy: "There is no local defense which alone will contain the mighty land power of the communist world. Local defenses must be reinforced by the further deterrent of massive retaliatory power." After this speech, the council convened a session on "Nuclear Weapons and Foreign Policy" and chose Henry Kissinger to head it. Kissinger spent the following academic year working on the project at Council headquarters. The book of the same name that he published from his research in 1957 gave him national recognition, topping the national bestseller lists.

On November 24, 1953, a study group heard a report from political scientist William Henderson regarding the ongoing conflict between France and Vietnamese Communist leader Ho Chi Minh's Viet Minh forces, a struggle that would later become known as the First Indochina War. Henderson argued that Ho's cause was primarily nationalist in nature and that Marxism had "little to do with the current revolution." Further, the report said, the United States could work with Ho to guide his movement away from Communism. State Department officials, however, expressed skepticism about direct American intervention in Vietnam and the idea was tabled. Over the next twenty years, the United States would find itself allied with anti-Communist South Vietnam

South Vietnam, officially the Republic of Vietnam ( vi, Việt Nam Cộng hòa), was a state in Southeast Asia that existed from 1955 to 1975, the period when the southern portion of Vietnam was a member of the Western Bloc during part of th ...

and against Ho and his supporters in the Vietnam War.

The Council served as a "breeding ground" for important American policies such as mutual deterrence

Mutual assured destruction (MAD) is a doctrine of military strategy and national security policy which posits that a full-scale use of nuclear weapons by an attacker on a nuclear-armed defender with second-strike capabilities would cause the ...

, arms control

Arms control is a term for international restrictions upon the development, production, stockpiling, proliferation and usage of small arms, conventional weapons, and weapons of mass destruction. Arms control is typically exercised through the u ...

, and nuclear non-proliferation

Nuclear proliferation is the spread of nuclear weapons, fissionable material, and weapons-applicable nuclear technology and information to nations not recognized as "List of states with nuclear weapons, Nuclear Weapon States" by the Treaty on ...

.

In 1962 the group began a program of bringing select Air Force officers to the Harold Pratt House to study alongside its scholars. The Army, Navy and Marine Corps requested they start similar programs for their own officers.

A four-year-long study of relations between America and China was conducted by the Council between 1964 and 1968. One study published in 1966 concluded that American citizens were more open to talks with China than their elected leaders. Henry Kissinger had continued to publish in ''Foreign Affairs'' and was appointed by President Nixon to serve as National Security Adviser A national security advisor serves as the chief advisor to a national government on matters of security. The advisor is not usually a member of the government's cabinet but is usually a member of various military or security councils.

National sec ...

in 1969. In 1971, he embarked on a secret trip to Beijing to broach talks with Chinese leaders. Richard Nixon went to China in 1972, and diplomatic relations were completely normalized by President Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (born October 1, 1924) is an American politician who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 76th governor of Georgia from 19 ...

's Secretary of State, another Council member, Cyrus Vance

Cyrus Roberts Vance Sr. (March 27, 1917January 12, 2002) was an American lawyer and United States Secretary of State under President Jimmy Carter from 1977 to 1980. Prior to serving in that position, he was the United States Deputy Secretary of ...

.

Vietnam created a rift within the organization. When Hamilton Fish Armstrong

Hamilton Fish Armstrong (April 7, 1893 – April 24, 1973) was an American diplomat and editor.

Biography

Armstrong attended Princeton University, then began a career in journalism at ''The New Republic''. During the First World War, he was ...

announced in 1970 that he would be leaving the helm of ''Foreign Affairs'' after 45 years, new chairman David Rockefeller approached a family friend, William Bundy

William Putnam Bundy (September 24, 1917 – October 6, 2000) was an American attorney and intelligence expert, an analyst with the CIA. Bundy served as a foreign affairs advisor to both presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson. He ha ...

, to take over the position. Anti-war advocates within the Council rose in protest against this appointment, claiming that Bundy's hawkish record in the State and Defense Departments and the CIA precluded him from taking over an independent journal. Some considered Bundy a war criminal for his prior actions.

In November 1979, while chairman of CFR, David Rockefeller became embroiled in an international incident when he and Henry Kissinger, along with John J. McCloy

John Jay McCloy (March 31, 1895 – March 11, 1989) was an American lawyer, diplomat, banker, and a presidential advisor. He served as Assistant Secretary of War during World War II under Henry Stimson, helping deal with issues such as German sa ...

and Rockefeller aides, persuaded President Jimmy Carter through the State Department to admit the Shah of Iran, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi

, title = Shahanshah Aryamehr Bozorg Arteshtaran

, image = File:Shah_fullsize.jpg

, caption = Shah in 1973

, succession = Shah of Iran

, reign = 16 September 1941 – 11 February 1979

, coronation = 26 October ...

, into the US for hospital treatment for lymphoma. This action directly precipitated what is known as the Iran hostage crisis and placed Rockefeller under intense media scrutiny (particularly from '' The New York Times'') for the first time in his public life.

In his book, '' White House Diary'', Carter wrote of the affair, "April 9 979David Rockefeller came in, apparently to induce me to let the shah come to the United States. Rockefeller, Kissinger, and Brzezinski seem to be adopting this as a joint project".

Current status

Membership

The CFR has two types of membership: life membership; and term membership, which lasts for 5 years and is available only to those between the ages of 30 and 36. Only U.S. citizens (native born or naturalized) and permanent residents who have applied for U.S. citizenship are eligible. A candidate for life membership must be nominated in writing by one Council member and seconded by a minimum of three others. Visiting fellows are prohibited from applying for membership until they have completed their fellowship tenure. Corporate membership (250 in total) is divided into "Associates", "Affiliates", "President's Circle", and "Founders". All corporate executive members have opportunities to hear speakers, including foreign heads of state, chairmen and CEOs of multinational corporations, and U.S. officials and Congressmen. President and premium members are also entitled to attend small, private dinners or receptions with senior American officials and world leaders. Women were excluded from membership until the 1960s.Funding and controversies

In 2019, it was criticized for accepting a donation fromLen Blavatnik

Sir Leonard Valentinovich Blavatnik, russian: Леонид Валентинович Блаватник, Leonid Valentinovich Blavatnik (born June 14, 1957) is a Ukraine-born American-British business magnate and philanthropist. As of March 202 ...

, a Ukrainian-born English billionaire with close links to Vladimir Putin. It was reported to be under fire from its own members and dozens of international affairs experts over its acceptance of a $12 million gift to fund an internship program. Fifty-five international relations scholars and Russia experts wrote a letter to the organization's board and CFR's president, Richard N. Haass. "It is our considered view that Blavatnik uses his 'philanthropy'—funds obtained by and with the consent of the Kremlin, at the expense of the state budget and the Russian people—at leading western academic and cultural institutions to advance his access to political circles. We regard this as another step in the longstanding effort of Mr. Blavatnik—who ... has close ties to the Kremlin and its kleptocratic network—to launder his image in the West."

Board members

Members of CFR's board of directors include: *David M. Rubenstein

David Mark Rubenstein (born August 11, 1949) is an American billionaire businessman. A former government official and lawyer, he is a co-founder and co-chairman of the private equity firm The Carlyle Group,The Carlyle Group. Regent of the Smithsonian Institution, chairman of the board for

"Publications of the Council on Foreign Relations." ''Mobilizing Civilian America''

Council on Foreign Relations, 1940. *''Political Handbook of the World'' (annual)

''Mobilizing Civilian America''

New York: Council on Foreign Relations, 1940. * Savord, Ruth

''American Agencies Interested in International Affairs''

Council on Foreign Relations, 1942. * Barnett, A. Doak

''Communist China and Asia: Challenge To American Policy''

New York: Harper & Brothers, 1960. * Bundy, William P. (ed.)

''Two Hundred Years of American Foreign Policy.''

New York University Press, 1977. * Clough, Michael

''Free at Last? U.S. Policy Toward Africa and the End of the Cold War''

New York: Council on Foreign Relations Press, 1991. * Mandelbaum, Michael

''The Rise of Nations in the Soviet Union: American Foreign Policy and the Disintegration of the USSR.''

New York: Council on Foreign Relations Press, 1991. * Gottlieb, Gidon

''Nation Against State: A New Approach to Ethnic Conflicts and the Decline of Sovereignty.''

New York: Council on Foreign Relations Press, 1993.

"Council on Foreign Relations says U.S. internet policy has failed, urges new approach"

Ryan Lovelace,''The Washington Times'', July 15, 2022. Retrieved August 7, 2022. (No. 80 updated: July 2022.)

Archived website

at Library of Congress (2001-2018) *

Membership Roster

Council on Foreign Relations Papers

at the Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library, Princeton University *

** ttp://www.cfr.org/educators/ "For Educators"– "Academic Outreach Initiative": Resources for educators and students; links to selected CFR publications * {{Authority control 1921 establishments in the United States Foreign policy and strategy think tanks in the United States Non-profit organizations based in Washington, D.C. Organizations based in New York City Think tanks established in 1921 Realist think tanks Rockefeller Foundation

Duke University

Duke University is a private research university in Durham, North Carolina. Founded by Methodists and Quakers in the present-day city of Trinity in 1838, the school moved to Durham in 1892. In 1924, tobacco and electric power industrialist James ...

, co-chair of the board at the Brookings Institution, and president of the Economic Club of Washington.

* Blair Effron

Blair W. Effron (born 1962) is an American financier. Effron co-founded Centerview Partners, a leading global investment banking firm based in New York City. Centerview has offices in London, Paris, Chicago, Los Angeles, Palo Alto and San Franci ...

(Vice Chairman) – Cofounder, Centerview Partners.

* Jami Miscik

Judith A. "Jami" Miscik (born 1958) is an American intelligence analyst who was also the Central Intelligence Agency's Deputy Director for Intelligence, the Agency's most senior analytic post. In 2005 she left CIA to become Global Head of Sovereig ...

(Vice Chairman) – Chief Executive Officer and Vice Chairman, Kissinger Associates, Inc.

Kissinger Associates, Inc. is a New York City-based international geopolitical consulting firm, founded and run by Henry Kissinger since 1982. The firm assists its clients in identifying strategic partners and investment opportunities and advisi ...

Ms. Miscik served as the global head of sovereign risk at Lehman Brothers. She also serves as a senior advisor to Barclays Capital. She currently serves on the boards of EMC Corporation, In-Q-Tel and the American Ditchley Foundation, and is a member of the President's Intelligence Advisory Board. Before entering the private sector, she had a twenty-year career as an intelligence officer, including a stint as the Central Intelligence Agency's Deputy Director for Intelligence (2002–2005), and as the Director for Intelligence Programs at the National Security Council

A national security council (NSC) is usually an executive branch governmental body responsible for coordinating policy on national security issues and advising chief executives on matters related to national security. An NSC is often headed by a na ...

(1995–1996).

* Richard N. Haass

Richard Nathan Haass (born July 28, 1951) is an American diplomat. He has been president of the Council on Foreign Relations since July 2003, prior to which he was Director of Policy Planning for the United States Department of State and a close ...

(President) – Former State Department director of policy planning and lead U.S. official on Afghanistan and Northern Ireland (2001–2003), and principal Middle East adviser to President George H.W. Bush

George Herbert Walker BushSince around 2000, he has been usually called George H. W. Bush, Bush Senior, Bush 41 or Bush the Elder to distinguish him from his eldest son, George W. Bush, who served as the 43rd president from 2001 to 2009; p ...

(1989–1993).

*Thad W. Allen

Thad William Allen (born 16 January 1949) is a former Admiral (United States), admiral of the United States Coast Guard who served as the 23rd Commandant of the Coast Guard, commandant from 2006 to 2010. Allen is best known for his widely prai ...

− Chair, National Space-Based Positioning, Navigation, and Timing Advisory Board, NASA.

*Nicholas F. Beim – Partner, Venrock.

*Afsaneh Mashayekhi Beschloss

Afsaneh Mashayekhi Beschloss (born July 28, 1956) is an American economist, businesswoman and entrepreneur. She is the CEO of RockCreek, an investment firm that she founded in 2003. Since the firm's inception, it has invested over $15 billion in w ...

− Founder and Chief Executive Officer, RockCreek.

*Sylvia Mathews Burwell

Sylvia Mary Burwell (; born June 23, 1965) is an American government and non-profit executive who has been the 15th president of American University since June 1, 2017. Burwell is the first woman to serve as the university's president. Burwell ...

– President, American University

The American University (AU or American) is a private federally chartered research university in Washington, D.C. Its main campus spans 90 acres (36 ha) on Ward Circle, mostly in the Spring Valley neighborhood of Northwest D.C. AU was charte ...

. Former United States Secretary of Health and Human Services (2014–2017) under President Barack Obama.

* Ashton B. Carter

Ashton Baldwin Carter (September 24, 1954 – October 24, 2022) was an American government official and academic who served as the 25th United States Secretary of Defense from February 2015 to January 2017. He later served as director of the B ...

– Director, Belfer Center at the Harvard Kennedy School. Former United States Secretary of Defense (2015–2017) under President Barack Obama.

* Kenneth I. Chenault − Chairman and Managing Director, General Catalyst

General Catalyst, formerly General Catalyst Partners (GCP), is an American venture capital firm focused on early stage and growth investments. The firm was founded in 2000 in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and also has offices in San Francisco, Palo A ...

.

* Tony Coles – Chairman and Chief Executive Officer, Cerevel Therapeutics.

*Cesar Conde

Cesar Conde is an American media executive currently serving as chairman of the NBCUniversal News Group, overseeing NBC News, MSNBC, and CNBC. Prior to this, Conde was chairman of NBCUniversal International Group and NBCUniversal Telemundo Enter ...

– Chairman, NBCUniversal News Group

NBCUniversal Television and Streaming is the television and streaming arm of NBCUniversal, and the direct descendant and successor of the former division NBCUniversal Television Group, which existed from 2003 to 2019.

History NBC Broadcasting

In ...

.

* Nathaniel Fick – General Manager, Elastic Security.

* Laurence D. Fink

Laurence Douglas Fink (born November 2, 1952) is an American billionaire businessman. He is the chairman and CEO of BlackRock, an American multinational investment management corporation. BlackRock is the largest money-management firm in the wor ...

– Chairman and Chief Executive Officer BlackRock.

*Stephen C. Freidheim − Chief Investment Officer and Senior Managing Partner, Cyrus Capital Partners L.P.

* Timothy Geithner – President, Warburg Pincus. Geithner served as 75th United States Secretary of the Treasury.

* James P. Gorman – Chairman and Chief Executive Officer, Morgan Stanley.

* Stephen Hadley

Stephen John Hadley (born February 13, 1947) is an American attorney and senior government official who served as the 20th United States National Security Advisor from 2005 to 2009. He served under President George W. Bush during the second term ...

– Principal, RiceHadley Gates. He was the 21st National Security Advisor A national security advisor serves as the chief advisor to a national government on matters of security. The advisor is not usually a member of the government's cabinet but is usually a member of various military or security councils.

National sec ...

.

* Margaret (Peggy) Hamburg − Foreign Secretary, National Academy of Medicine.

* Laurene Powell Jobs – Founder and President, Emerson Collective.

*Jeh Charles Johnson

Jeh Charles Johnson ( "Jay"; born September 11, 1957) is an American lawyer and former government official. He was United States Secretary of Homeland Security from 2013 to 2017.

From 2009 to 2012, Johnson was the general counsel of the Departm ...

− Partner, Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison LLP

Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison LLP (known as Paul, Weiss) is an American multinational law firm headquartered on Sixth Avenue in New York City. By profits per equity partner, it is the fifth most profitable law firm in the world. ...

. Former Homeland Security Secretary

The United States secretary of homeland security is the head of the United States Department of Homeland Security, the federal department tasked with ensuring public safety in the United States. The secretary is a member of the Cabinet of the U ...

(2013-2017) under President Barack Obama.

* James Manyika – Senior Partner, McKinsey & Company

McKinsey & Company is a global management consulting firm founded in 1926 by University of Chicago professor James O. McKinsey, that offers professional services to corporations, governments, and other organizations. McKinsey is the oldest and ...

, Chairman and Director, McKinsey Global Institute.

* William H. McRaven

William Harry McRaven (born November 6, 1955) is a retired United States Navy four-star admiral who served as the ninth commander of the United States Special Operations Command (SOCOM) from August 8, 2011 to August 28, 2014. From 2015 to 2018, ...

– Professor of National Security, Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs

The Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs (or LBJ School of Public Affairs) is a graduate school at the University of Texas at Austin that was founded in 1970 to offer training in public policy analysis and administration for students that ar ...

, The University of Texas at Austin.

* Janet Napolitano – Professor of Public Policy, Goldman School of Public Policy, University of California, Berkeley, former U.S. Attorney

United States attorneys are officials of the U.S. Department of Justice who serve as the chief federal law enforcement officers in each of the 94 U.S. federal judicial districts. Each U.S. attorney serves as the United States' chief federal c ...

(1993–1997), Attorney General of Arizona

The Arizona Attorney General is the chief legal officer of the State of Arizona, in the United States. This state officer is the head of the Arizona Department of Law, more commonly known as the Arizona Attorney General's Office. The state attorne ...

(1999–2003), Governor of Arizona (2003–2009), and President Barack Obama's first Homeland Security Secretary

The United States secretary of homeland security is the head of the United States Department of Homeland Security, the federal department tasked with ensuring public safety in the United States. The secretary is a member of the Cabinet of the U ...

(2009–2013).

* Meghan L. O'Sullivan − Jeane Kirkpatrick Professor of the Practice of International Affairs, Harvard Kennedy School.

* Deven J. Parekh – Managing Director, Insight Partners.

* Charles Phillips − Managing Partner and Cofounder, Recognize.

* Richard L. Plepler – Chief Executive Officer, Eden Productions.

* Ruth Porat – Senior Vice President and Chief Financial Officer, Alphabet and Google.

* L. Rafael Reif − President, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT)

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is a private land-grant research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Established in 1861, MIT has played a key role in the development of modern technology and science, and is one of the m ...

.

* Frances Fragos Townsend − Executive Vice President, Corporate Affairs, Activision Blizzard.

*Tracey T. Travis – Executive Vice President of Finance and Chief Financial Officer, Estée Lauder Companies.

* Margaret Warner – Practitioner in Residence, School of International Service, American University, previously reported for PBS NewsHour and '' The Wall Street Journal''.

* Daniel Yergin – Vice Chairman, IHS Markit.

* Fareed Zakaria

Fareed Rafiq Zakaria (; born 20 January 1964) is an Indian-American journalist, political commentator, and author. He is the host of CNN's ''Fareed Zakaria GPS'' and writes a weekly paid column for ''The Washington Post.'' He has been a columnist ...

– Host, CNN's '' Fareed Zakaria GPS''. Editor at large of '' Time'' magazine, and regular columnist for '' The Washington Post''. From 2000 to 2010, Zakaria was the editor of '' Newsweek International'', and managing editor of ''Foreign Affairs'' from 1992–2000.

''Foreign Affairs''

The council publishes the international affairs magazine ''Foreign Affairs

''Foreign Affairs'' is an American magazine of international relations and U.S. foreign policy published by the Council on Foreign Relations, a nonprofit, nonpartisan, membership organization and think tank specializing in U.S. foreign policy and ...

''. It also establishes independent task forces, which bring together various experts to produce reports offering both findings and policy prescriptions on foreign policy topics. CFR has sponsored more than fifty reports, including the Independent Task Force on the Future of North America that published report No. 53, entitled ''Building a North American Community'', in May 2005.

As a charity

The council received a three star rating (out of a possible four stars) fromCharity Navigator

Charity Navigator is a charity assessment organization that evaluates hundreds of thousands of charitable organizations based in the United States, operating as a free 501(c)(3) organization. It provides insights into a nonprofit’s financial s ...

in fiscal year 2016, as measured by their analysis of the council's financial data and "accountability and transparency".

Publications

Periodicals

*''Foreign Affairs

''Foreign Affairs'' is an American magazine of international relations and U.S. foreign policy published by the Council on Foreign Relations, a nonprofit, nonpartisan, membership organization and think tank specializing in U.S. foreign policy and ...

'' (quarterly)

*''The United States in World Affairs'' (annual) Tobin, Harold J. & Bidwell, Percy W."Publications of the Council on Foreign Relations." ''Mobilizing Civilian America''

Council on Foreign Relations, 1940. *''Political Handbook of the World'' (annual)

Books

* Tobin, Harold J. & Bidwell, Percy W''Mobilizing Civilian America''

New York: Council on Foreign Relations, 1940. * Savord, Ruth

''American Agencies Interested in International Affairs''

Council on Foreign Relations, 1942. * Barnett, A. Doak

''Communist China and Asia: Challenge To American Policy''

New York: Harper & Brothers, 1960. * Bundy, William P. (ed.)

''Two Hundred Years of American Foreign Policy.''

New York University Press, 1977. * Clough, Michael

''Free at Last? U.S. Policy Toward Africa and the End of the Cold War''

New York: Council on Foreign Relations Press, 1991. * Mandelbaum, Michael

''The Rise of Nations in the Soviet Union: American Foreign Policy and the Disintegration of the USSR.''

New York: Council on Foreign Relations Press, 1991. * Gottlieb, Gidon

''Nation Against State: A New Approach to Ethnic Conflicts and the Decline of Sovereignty.''

New York: Council on Foreign Relations Press, 1993.

Reports

* "Confronting Reality in Cyberspace: Foreign Policy for a Fragmented Internet" recommends reconsideration of U.S. cyber, digital trade and online freedom policies which champion a free and open internet, as having failed.Ryan Lovelace,''The Washington Times'', July 15, 2022. Retrieved August 7, 2022. (No. 80 updated: July 2022.)

See also

*Members of the Council on Foreign Relations

Membership in the Council on Foreign Relations comes in two types: Individual and Corporate. Individual memberships are further subdivided into two types: Life Membership and Term Membership, the latter of which is for a single period of five years ...

References

Sources

* * * Parmar, Inderjeet (2004). ''Think Tanks and Power in Foreign Policy: A Comparative Study of the Role and Influence of the Council on Foreign Relations and the Royal Institute of International Affairs, 1939−1945.'' London: Palgrave.External links

*Archived website

at Library of Congress (2001-2018) *

Membership Roster

Council on Foreign Relations Papers

at the Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library, Princeton University *

** ttp://www.cfr.org/educators/ "For Educators"– "Academic Outreach Initiative": Resources for educators and students; links to selected CFR publications * {{Authority control 1921 establishments in the United States Foreign policy and strategy think tanks in the United States Non-profit organizations based in Washington, D.C. Organizations based in New York City Think tanks established in 1921 Realist think tanks Rockefeller Foundation