The Cenotaph, Whitehall on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Cenotaph is a war memorial on

The

The

The First World War ended with the

The First World War ended with the

Suggestions that the temporary cenotaph should be re-built as a permanent structure began almost immediately, coming from members of the public and national newspapers. Four days after the parade, William Ormsby-Gore, Member of Parliament for

Suggestions that the temporary cenotaph should be re-built as a permanent structure began almost immediately, coming from members of the public and national newspapers. Four days after the parade, William Ormsby-Gore, Member of Parliament for

The Cenotaph is made from

The Cenotaph is made from  The Cenotaph is flanked on the long sides by flags of the United Kingdom—the

The Cenotaph is flanked on the long sides by flags of the United Kingdom—the

No date was announced for the completion of the Cenotaph at first, but the British government was keen to have it in place for

No date was announced for the completion of the Cenotaph at first, but the British government was keen to have it in place for

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, it was customary for men to doff their hats when passing the Cenotaph, even on a bus. The pilgrimage which began with the Cenotaph's unveiling continued on a smaller scale for the rest of the 1920s and into the 1930s. Pilgrimages continued until the outbreak of the Second World War. A particularly large crowd gathered on 11 November 1946, the year after that war ended, but attendance largely fell away thereafter. In the later 1920s, several proposals emerged for modifications to the Cenotaph, including the addition of life-size bronze statues at its corners, and installing a light inside the wreath at the top to emit a vertical beam, but all were rejected by the Office of Works on Lutyens's advice. The statues in particular would have added a literal element to the memorial which Greenberg (writing in 1989) believed would have been at odds with its "open symbolism and abstract character".Greenberg, p. 12.

After the unveiling of the permanent memorial, members of the public continued to lay floral tributes as well as hand-written messages and personal memorials such as photographs, wreaths, and glass domes. The Office of Works struggled to decide what to do with the tributes and how to maintain an appropriate tone. It began preserving the messages so that they could be compiled into albums and given to the Imperial War Museum. By March 1921, officials had catalogued more than 30,000 items; the volume was such that they were forced to abandon their efforts at preservation. The office was keen to avoid being seen as a censor but also to preserve the character of the Cenotaph; officials thus removed some tributes which contained overtly political messages.Edkins, pp. 66–70. A group of 5,000 unemployed men, on an anti-capitalist protest, paraded past the Cenotaph in 1921 and laid wreaths at its base; several with explicit political messages were removed. In 1933,

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, it was customary for men to doff their hats when passing the Cenotaph, even on a bus. The pilgrimage which began with the Cenotaph's unveiling continued on a smaller scale for the rest of the 1920s and into the 1930s. Pilgrimages continued until the outbreak of the Second World War. A particularly large crowd gathered on 11 November 1946, the year after that war ended, but attendance largely fell away thereafter. In the later 1920s, several proposals emerged for modifications to the Cenotaph, including the addition of life-size bronze statues at its corners, and installing a light inside the wreath at the top to emit a vertical beam, but all were rejected by the Office of Works on Lutyens's advice. The statues in particular would have added a literal element to the memorial which Greenberg (writing in 1989) believed would have been at odds with its "open symbolism and abstract character".Greenberg, p. 12.

After the unveiling of the permanent memorial, members of the public continued to lay floral tributes as well as hand-written messages and personal memorials such as photographs, wreaths, and glass domes. The Office of Works struggled to decide what to do with the tributes and how to maintain an appropriate tone. It began preserving the messages so that they could be compiled into albums and given to the Imperial War Museum. By March 1921, officials had catalogued more than 30,000 items; the volume was such that they were forced to abandon their efforts at preservation. The office was keen to avoid being seen as a censor but also to preserve the character of the Cenotaph; officials thus removed some tributes which contained overtly political messages.Edkins, pp. 66–70. A group of 5,000 unemployed men, on an anti-capitalist protest, paraded past the Cenotaph in 1921 and laid wreaths at its base; several with explicit political messages were removed. In 1933,

The Cenotaph the Morning of the Peace Procession by Sir William Nicholson.jpg, The temporary cenotaph on the morning of the Peace Procession in 1919 by Sir William Nicholson, alt=Painting of a monument

Reverse of Armistice Day Memorial Medal 1928.jpg, The Cenotaph featured on the reverse of the 1928 Armistice Day memorial medal by

A 1936 novel by Irene Rathbone with an anti-war theme, ''They Call it Peace'', concluded with a scene set at the Cenotaph in which two women complete pilgrimages to the monument, one to honour the dead and one feeling that the deaths were in vain. The cultural response to the Cenotaph also includes poetry such as "The Cenotaph" (1919) by

According to one study of British war memorials, the Cenotaph's "deceptively simple design and deliberately non-sectarian message ensured that its form would be adopted widely, with local variations". From its unveiling, the Cenotaph proved highly influential on other war memorials in Britain. The art historian Alan Borg wrote that the Cenotaph was the "one memorial that proved to be more influential than any other". Several towns and cities erected war memorials based to some extent on Lutyens's design for Whitehall, though the term "cenotaph" came to be applied to almost any war memorial that was not itself a tomb. Lutyens designed several other cenotaphs in England and one in Wales, while replicas, of varying quality and accuracy, were built across Britain, along with many other monuments inspired to some extent by Lutyens's design.Borg, p. 96. Examples include Leeds War Memorial and Glasgow Cenotaph.King, pp. 148–149.

Replicas were also built in other countries of the British Empire, usually by local architects with input from Lutyens.Skelton, pp. 99–100. The government of

According to one study of British war memorials, the Cenotaph's "deceptively simple design and deliberately non-sectarian message ensured that its form would be adopted widely, with local variations". From its unveiling, the Cenotaph proved highly influential on other war memorials in Britain. The art historian Alan Borg wrote that the Cenotaph was the "one memorial that proved to be more influential than any other". Several towns and cities erected war memorials based to some extent on Lutyens's design for Whitehall, though the term "cenotaph" came to be applied to almost any war memorial that was not itself a tomb. Lutyens designed several other cenotaphs in England and one in Wales, while replicas, of varying quality and accuracy, were built across Britain, along with many other monuments inspired to some extent by Lutyens's design.Borg, p. 96. Examples include Leeds War Memorial and Glasgow Cenotaph.King, pp. 148–149.

Replicas were also built in other countries of the British Empire, usually by local architects with input from Lutyens.Skelton, pp. 99–100. The government of

File:Southampton-Cenotaph.jpg,

Whitehall

Whitehall is a road and area in the City of Westminster, Central London. The road forms the first part of the A roads in Zone 3 of the Great Britain numbering scheme, A3212 road from Trafalgar Square to Chelsea, London, Chelsea. It is the main ...

in London, England. Designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens

Sir Edwin Landseer Lutyens ( ; 29 March 1869 – 1 January 1944) was an English architect known for imaginatively adapting traditional architectural styles to the requirements of his era. He designed many English country houses, war memoria ...

, it was unveiled in 1920 as the United Kingdom's national memorial to the British and Commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. Historically, it has been synonymous with "republic". The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the ...

dead of the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, was rededicated in 1946 to include those of the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, and has since come to represent British casualties from later conflicts. The word ''cenotaph

A cenotaph is an empty tomb or a monument erected in honour of a person or group of people whose remains are elsewhere. It can also be the initial tomb for a person who has since been reinterred elsewhere. Although the vast majority of cenot ...

'' is derived from Greek, meaning 'empty tomb'. Most of the dead were buried close to where they fell; thus, the Cenotaph symbolises their absence and is a focal point for public mourning. The original temporary Cenotaph was erected in 1919 for a parade celebrating the end of the First World War, at which more than 15,000 servicemen, including French and American soldiers, saluted the monument. More than a million people visited the site within a week of the parade.

Calls for the Cenotaph to be rebuilt in permanent form began almost immediately. After some debate, the government agreed and construction work began in May 1920. Lutyens added entasis

In architecture, entasis is the application of a convex curve to a surface for aesthetic purposes. Its best-known use is in certain orders of Classical columns that curve slightly as their diameter is decreased from the bottom upward. It also may ...

(curvature) but otherwise made minimal design alterations. The Cenotaph is built from Portland stone

Portland stone is a limestone from the Tithonian stage of the Jurassic period quarried on the Isle of Portland, Dorset. The quarries are cut in beds of white-grey limestone separated by chert beds. It has been used extensively as a building sto ...

. It takes the form of a tomb chest atop a rectangular pylon, which diminishes as it rises. Three flags hang from each of the long sides. The memorial is austere, containing almost no decoration. The permanent Cenotaph was unveiled by King George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until his death in 1936.

Born during the reign of his grandmother Que ...

on 11 November 1920 in a ceremony combined with the repatriation of the Unknown Warrior

The British grave of the Unknown Warrior (often known as 'The Tomb of the Unknown Warrior') holds an unidentified member of the British armed forces killed on a European battlefield during the First World War.Hanson, Chapters 23 & 24 He was gi ...

, an unidentified British serviceman to be interred in Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

. After the unveiling, millions more people visited the Cenotaph and the Unknown Warrior. The memorial met with public acclaim and has largely been praised by academics, though some Christian organisations disapproved of its lack of overt religious symbolism.

The Cenotaph has been revered since its unveiling, and while nationally important has been the scene of several political protests and vandalised with spray paint twice in the 21st century. The National Service of Remembrance

The National Service of Remembrance is held every year on Remembrance Sunday at the Cenotaph on Whitehall, London. It commemorates "the contribution of British and Commonwealth military and civilian servicemen and women in the two World Wars and l ...

is held annually at the site on Remembrance Sunday

Remembrance Sunday is held in the United Kingdom as a day to commemorate the contribution of British and Commonwealth military and civilian servicemen and women in the two World Wars and later conflicts. It is held on the second Sunday in Nov ...

; it is also the scene of other remembrance services. The Cenotaph is a grade I listed building

In the United Kingdom, a listed building or listed structure is one that has been placed on one of the four statutory lists maintained by Historic England in England, Historic Environment Scotland in Scotland, in Wales, and the Northern Irel ...

and forms part of a national collection of Lutyens's war memorials. Dozens of replicas were built in Britain and other Commonwealth countries. While there was no set or agreed standard for First World War memorials, the Cenotaph proved to be one of the most influential models for such structures. Lutyens designed several other cenotaphs, which all shared common features with that at Whitehall. The Cenotaph has been the subject of several artworks and has featured in multiple works of literature, including a novel and several poems. The public acclaim for the monument was responsible for Lutyens becoming a national figure, and the Royal Institute of British Architects

The Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) is a professional body for architects primarily in the United Kingdom, but also internationally, founded for the advancement of architecture under its royal charter granted in 1837, three suppl ...

awarded him its Royal Gold Medal

The Royal Gold Medal for architecture is awarded annually by the Royal Institute of British Architects on behalf of the British monarch, in recognition of an individual's or group's substantial contribution to international architecture. It is g ...

in 1921. For several years afterwards much of his time was taken up with war memorial commissions.

Background

The

The First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

produced casualties on a scale previously unseen by developed nations. More than 1.1million men from the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

were killed. In the war's aftermath, thousands of war memorials were erected across Britain and its empire, and on the former battlefields. Amongst the most prominent designers of war memorials was Sir Edwin Lutyens

Sir Edwin Landseer Lutyens ( ; 29 March 1869 – 1 January 1944) was an English architect known for imaginatively adapting traditional architectural styles to the requirements of his era. He designed many English country houses, war memoria ...

, described by Historic England

Historic England (officially the Historic Buildings and Monuments Commission for England) is an executive non-departmental public body of the British Government sponsored by the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport. It is tasked wit ...

as "the foremost architect of his day". Lutyens established his reputation designing country house

An English country house is a large house or mansion in the English countryside. Such houses were often owned by individuals who also owned a town house. This allowed them to spend time in the country and in the city—hence, for these peopl ...

s for wealthy clients around the turn of the 20th century; his first major public commission was the design of much of New Delhi, the new capital of British India. The war had a profound effect on Lutyens and following it he devoted much of his time to the commemoration of its casualties. By the time he was commissioned for the Cenotaph, he was already acting as an adviser to the Imperial War Graves Commission

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) is an intergovernmental organisation of six independent member states whose principal function is to mark, record and maintain the graves and places of commemoration of Commonwealth of Nations mil ...

(IWGC). In 1917, he travelled to France under the auspices of the IWGC and was horrified by the scale of destruction. The experience influenced his later designs for war memorials and led him to the conclusion that a different form of architecture was required to properly memorialise the dead. He felt that neither realism

Realism, Realistic, or Realists may refer to:

In the arts

*Realism (arts), the general attempt to depict subjects truthfully in different forms of the arts

Arts movements related to realism include:

*Classical Realism

*Literary realism, a move ...

nor expressionism

Expressionism is a modernist movement, initially in poetry and painting, originating in Northern Europe around the beginning of the 20th century. Its typical trait is to present the world solely from a subjective perspective, distorting it rad ...

could adequately capture the atmosphere at the end of the war.

Lutyens's first war memorial was the Rand Regiments Memorial

The RAND Corporation (from the phrase "research and development") is an American nonprofit global policy think tank created in 1948 by Douglas Aircraft Company to offer research and analysis to the United States Armed Forces. It is financed ...

(1911) in Johannesburg

Johannesburg ( , , ; Zulu and xh, eGoli ), colloquially known as Jozi, Joburg, or "The City of Gold", is the largest city in South Africa, classified as a megacity, and is one of the 100 largest urban areas in the world. According to Demo ...

, South Africa, dedicated to casualties of the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the Sout ...

(1899–1902). His first commission for a memorial to the First World War was for Southampton Cenotaph

Southampton Cenotaph is a World War I memorials, First World War memorial designed by Edwin Lutyens, Sir Edwin Lutyens and located in Watts Park in the southern English city of Southampton. The memorial was the first of dozens by Lutyens to be ...

. The word ''cenotaph

A cenotaph is an empty tomb or a monument erected in honour of a person or group of people whose remains are elsewhere. It can also be the initial tomb for a person who has since been reinterred elsewhere. Although the vast majority of cenot ...

'' derives from the Greek word , meaning 'empty tomb'. Lutyens first encountered the term in connection with Munstead Wood

Munstead Wood is a Grade I listed house and garden in Munstead Heath, Busbridge on the boundary of the town of Godalming in Surrey, England, south-east of the town centre. The garden was created by garden designer Gertrude Jekyll, and became ...

, the house he designed for Gertrude Jekyll

Gertrude Jekyll ( ; 29 November 1843 – 8 December 1932) was a British horticulturist, garden designer, craftswoman, photographer, writer and artist. She created over 400 gardens in the United Kingdom, Europe and the United States, and wrote ...

in the 1890s. There he designed a garden seat in the form of a rectangular block of elm

Elms are deciduous and semi-deciduous trees comprising the flowering plant genus ''Ulmus'' in the plant family Ulmaceae. They are distributed over most of the Northern Hemisphere, inhabiting the temperate and tropical-montane regions of North ...

set on stone, which Charles Liddell—a friend of Lutyens and Jekyll and a librarian at the British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

—christened the " Cenotaph of Sigismunda".Koureas, p. 38.Massingham, pp. 140–142.

From 1915, the British government prohibited the repatriation of the bodies of men killed overseas, meaning that most bereaved families did not have a nearby grave to visit and thus war memorials became a focal point for their grief. Cenotaphs originated in Ancient Greek tradition, where they were built when it was impossible to recover a body after the battle, as the Greeks placed great cultural importance on the proper burial of their war dead. Lutyens remembered the term when working on Southampton's memorial in early 1919. He broke with the Ancient Greek convention in that his designs for London's and Southampton's cenotaphs contained no explicit reference to battle. The result at Southampton (unveiled a week before London's permanent Cenotaph) lacks the subtlety of London's monument, but introduces several design elements common in Lutyens's subsequent memorials.

Origins: the temporary Cenotaph

The First World War ended with the

The First World War ended with the Armistice of 11 November 1918

The Armistice of 11 November 1918 was the armistice signed at Le Francport near Compiègne that ended fighting on land, sea, and air in World War I between the Entente and their last remaining opponent, Germany. Previous armistices ...

, although it was not officially declared over until the signing of the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

on 28 June 1919. The British government planned to hold a victory parade in London on 19 July, including soldiers marching to Whitehall

Whitehall is a road and area in the City of Westminster, Central London. The road forms the first part of the A roads in Zone 3 of the Great Britain numbering scheme, A3212 road from Trafalgar Square to Chelsea, London, Chelsea. It is the main ...

, the centre of the British government. The initial design for what would become the Cenotaph was one of a number of temporary structures erected along the parade's route. The prime minister, David Lloyd George

David Lloyd George, 1st Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, (17 January 1863 – 26 March 1945) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1916 to 1922. He was a Liberal Party politician from Wales, known for leading the United Kingdom during t ...

, learnt that the French plans for a similar parade in Paris included a saluting point for the marching troops and was keen to replicate the idea for the British parade. How Lutyens became involved is unclear, but he was close friends with Sir Alfred Mond and Sir Lionel Earle (respectively the government minister and senior civil servant at the Office of Works

The Office of Works was established in the England, English Royal Household, royal household in 1378 to oversee the building and maintenance of the royal castles and residences. In 1832 it became the Works Department forces within the Office of W ...

, which was responsible for public building projects) and it seems likely that one or both men discussed the idea with Lutyens. Lloyd George summoned Lutyens and asked him to design a "catafalque

A catafalque is a raised bier, box, or similar platform, often movable, that is used to support the casket, coffin, or body of a dead person during a Christian funeral or memorial service. Following a Roman Catholic Requiem Mass, a catafalque ...

" as the centre point for the parade. Lloyd George emphasised that the structure was to be non-denominational. Lutyens met with Sir Frank Baines, chief architect at the Office of Works, the same day to sketch his idea for the Cenotaph and sketched it again for his friend Lady Sackville over dinner that night. Both sketches show the Cenotaph almost as-built.

At the end of the war, there was considerable social upheaval and civil unrest in Britain and Ireland, and industrial relations were tense. The government, fearful that revolutionary ideologies such as Bolshevism

Bolshevism (from Bolshevik) is a revolutionary socialist current of Soviet Marxist–Leninist political thought and political regime associated with the formation of a rigidly centralized, cohesive and disciplined party of social revolution, fo ...

might start to take hold, hoped the parade and a central saluting point would unite the nation in celebrating the victorious conclusion to the war and commemorating the sacrifice of the dead.

Although Lutyens apparently produced the design very quickly, he had had the concept in mind for some time, as evidenced by his design for Southampton Cenotaph and his work for the IWGC. Lutyens and Mond had previously worked together on a design for a war shrine in Hyde Park

Hyde Park may refer to:

Places

England

* Hyde Park, London, a Royal Park in Central London

* Hyde Park, Leeds, an inner-city area of north-west Leeds

* Hyde Park, Sheffield, district of Sheffield

* Hyde Park, in Hyde, Greater Manchester

Austra ...

, intended to replace a temporary structure erected during the war. Though the shrine was never built, the design started Lutyens thinking about commemorative architecture, and the architectural historian Allan Greenberg

Allan Greenberg (born September 1938) is an American architect and one of the leading classical architects of the twenty-first century, also known as New Classical Architecture.

He was the originator and leading practitioner of "canonical cl ...

speculates that Mond may have discussed the concept of a memorial with Lutyens prior to the meeting with the prime minister. According to Tim Skelton, author of ''Lutyens and the Great War'', "If it was not to be on Whitehall then the Cenotaph as we know it would have appeared somewhere else in due course."Skelton, p. 42. Several of Lutyens's sketches survive, which show that he experimented with multiple minor changes to the design, including a flaming urn at the top of the Cenotaph and sculptures of soldiers or lions at the base (similar to the lion heads on Southampton Cenotaph).

Lutyens submitted his final design to the Office of Works in early July, and on 7 July received confirmation that the design had been approved by the foreign secretary, Lord Curzon

George Nathaniel Curzon, 1st Marquess Curzon of Kedleston, (11 January 1859 – 20 March 1925), styled Lord Curzon of Kedleston between 1898 and 1911 and then Earl Curzon of Kedleston between 1911 and 1921, was a British Conservative statesman ...

, who was organising the parade.Greenberg, p. 9. The unveiling of the monument, built in wood and plaster by the Office of Works, was described in ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper ''The Sunday Times'' (fou ...

'' as a quiet and unofficial ceremony. It took place on 18 July 1919, the day before the Victory Parade. Lutyens was not invited. During the parade, 15,000 soldiers and 1,500 officers marched past and saluted the Cenotaph—among them were American General John J. Pershing

General of the Armies John Joseph Pershing (September 13, 1860 – July 15, 1948), nicknamed "Black Jack", was a senior United States Army officer. He served most famously as the commander of the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) on the Wes ...

and French Marshal Ferdinand Foch

Ferdinand Foch ( , ; 2 October 1851 – 20 March 1929) was a French general and military theorist who served as the Supreme Allied Commander during the First World War. An aggressive, even reckless commander at the First Marne, Flanders and Art ...

, as well as the British commanders Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig

Field Marshal Douglas Haig, 1st Earl Haig, (; 19 June 1861 – 29 January 1928) was a senior officer of the British Army. During the First World War, he commanded the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) on the Western Front from late 1915 until ...

and Admiral of the Fleet Sir David Beatty

Admiral of the Fleet David Richard Beatty, 1st Earl Beatty (17 January 1871 – 12 March 1936) was a Royal Navy officer. After serving in the Mahdist War and then the response to the Boxer Rebellion, he commanded the 1st Battlecruiser Squadro ...

. The Cenotaph quickly captured the public imagination. Repatriation of the dead had been forbidden since the early days of the war, so the Cenotaph came to represent the absent dead and serve as a substitute for a tomb. Beginning almost immediately after the Victory Parade and continuing for days afterwards, members of the public began laying flowers and wreaths around the memorial. Within a week, an estimated 1.2million people came to the Cenotaph to pay their respects to the dead, and the base was covered in flowers and other tributes.Skelton, p. 43. According to ''The Times'', "no feature of the victory march in London made a deeper impression than the Cenotaph."Greenberg, p. 8.

After the Victory Parade, the temporary Cenotaph became a point of pilgrimage for many people, including grieving relatives. Deputations arrived from as far away as Dundee

Dundee (; sco, Dundee; gd, Dùn Dè or ) is Scotland's fourth-largest city and the 51st-most-populous built-up area in the United Kingdom. The mid-year population estimate for 2016 was , giving Dundee a population density of 2,478/km2 or ...

, and schools organised excursions to take children to see it. The crowds were particularly large on 11 November 1919, the first anniversary of the armistice. An estimated 6,000 people were crowded round the memorial and it took the intervention of the police to create space for Lloyd George to lay a wreath. The French president, Raymond Poincaré

Raymond Nicolas Landry Poincaré (, ; 20 August 1860 – 15 October 1934) was a French statesman who served as President of France from 1913 to 1920, and three times as Prime Minister of France.

Trained in law, Poincaré was elected deputy in 1 ...

, also laid a wreath; King George V and Queen Mary sent a wreath but were not present at the Cenotaph. A two-minute silence

In the United Kingdom and other countries within the Commonwealth, a two-minute silence is observed as part of Remembrance Day to remember those who lost their lives in conflict. Held each year at 11:00 am on 11 November, the silence coinc ...

was observed, after which veterans' groups marched past. The government, caught by surprise by the strength of feeling, resolved to lay on an organised event for 1920.

Reconstruction in stone

Suggestions that the temporary cenotaph should be re-built as a permanent structure began almost immediately, coming from members of the public and national newspapers. Four days after the parade, William Ormsby-Gore, Member of Parliament for

Suggestions that the temporary cenotaph should be re-built as a permanent structure began almost immediately, coming from members of the public and national newspapers. Four days after the parade, William Ormsby-Gore, Member of Parliament for Stafford

Stafford () is a market town and the county town of Staffordshire, in the West Midlands region of England. It lies about north of Wolverhampton, south of Stoke-on-Trent and northwest of Birmingham. The town had a population of 70,145 in t ...

—an army officer who fought in the war and was part of the British delegation at Versailles—questioned Mond about the Cenotaph in the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

, and asked whether a permanent replacement was planned. Ormsby-Gore was supported by multiple other members. Mond announced that the decision rested with the cabinet, but promised to pass on the support of the House. The following week, ''The Times'' published an editorial calling for a permanent replacement (though the writer suggested that there was a risk of vehicles crashing into the Cenotaph in its original location and that it be built on nearby Horse Guards Parade

Horse Guards Parade is a large parade ground off Whitehall in central London (at grid reference ). It is the site of the annual ceremonies of Trooping the Colour, which commemorates the monarch's official birthday, and the Beating Retreat.

Hi ...

); many letters to London and national newspapers followed. The cabinet sought Lutyens's opinion, which was that the original site had been "qualified by the salutes of Foch and the allied armies ndno other site would give this pertinence." Mond agreed, telling the cabinet that "no other site would have the same historical or sentimental association."King, p. 146. The cabinet bowed to public pressure, approving the re-building in stone, and in the original location, at its meeting on 30 July 1919.Greenberg, p. 10.

Concerns remained about the Cenotaph's location. Another editorial in ''The Times'' suggested siting it in Parliament Square

Parliament Square is a square at the northwest end of the Palace of Westminster in the City of Westminster in central London. Laid out in the 19th century, it features a large open green area in the centre with trees to its west, and it contai ...

, away from traffic, a location that was supported by the local authorities. The issue was again raised in the House of Commons, and Ormsby-Gore led the calls for the Cenotaph to be rebuilt on its original spot, stating, to acclaim, that he was certain that this option was the most popular with the public. Opposition to the site eventually quietened and the construction contract was awarded to Holland, Hannen & Cubitts

Holland, Hannen & Cubitts was a major building firm responsible for many of the great buildings of London.

History

The company was formed from the fusion of two well-established building houses that had competed throughout the later decades of ...

. Construction began in May 1920.

Lutyens waived his fee, and Mond gave Lutyens the opportunity to make any amendments to the design before work began. The architect submitted his proposed modifications on 1 November, which were approved the same day. He replaced the real laurel wreath

A laurel wreath is a round wreath made of connected branches and leaves of the bay laurel (), an aromatic broadleaf evergreen, or later from spineless butcher's broom (''Ruscus hypoglossum'') or cherry laurel (''Prunus laurocerasus''). It is a sy ...

s with stone sculptures and added entasis

In architecture, entasis is the application of a convex curve to a surface for aesthetic purposes. Its best-known use is in certain orders of Classical columns that curve slightly as their diameter is decreased from the bottom upward. It also may ...

—subtle curvature, reminiscent of the Parthenon

The Parthenon (; grc, Παρθενών, , ; ell, Παρθενώνας, , ) is a former temple on the Athenian Acropolis, Greece, that was dedicated to the goddess Athena during the fifth century BC. Its decorative sculptures are considere ...

, so that the vertical surfaces taper inwards and the horizontals form arcs of a circle.Ward-Jackson, p. 418.Greenberg, p. 11. He wrote to Mond:

Lutyens had earlier used entasis for his Stone of Remembrance

The Stone of Remembrance is a standardised design for war memorials that was designed in 1917 by the British architect Sir Edwin Lutyens for the Imperial War Graves Commission (IWGC). It was designed to commemorate the dead of World War I, to b ...

, which appears in most large IWGC cemeteries. Some religious groups objected to the lack of Christian symbolism on the Cenotaph and suggested the inclusion of a cross or a more overtly Christian inscription. Lutyens objected to the proposal, and it was rejected by the government on the grounds that the Cenotaph was for people "from all parts of the empire, irrespective of their religious creeds".Edkins, p. 64. The only other significant alteration Lutyens proposed was the replacement of the silk flags on the temporary Cenotaph with painted stone, fearing that the fabric would quickly become worn and look untidy. He was supported on this by Mond and engaged the sculptor Francis Derwent Wood

Francis Derwent Wood (15 October 1871– 19 February 1926) was a British sculptor.

Biography

Early life

Wood was born at Keswick in Cumbria and studied in Germany and returned to London in 1887 to work under Édouard Lantéri and Sir Thomas ...

for assistance, but the change was rejected by the cabinet. A diary entry by Lady Sackville from August 1920 records Lutyens complaining bitterly about the change, though documents in The National Archives

National archives are central archives maintained by countries. This article contains a list of national archives.

Among its more important tasks are to ensure the accessibility and preservation of the information produced by governments, both ...

suggest that he had been aware of it six months previously.Skelton, pp. 43–45.

The temporary Cenotaph, originally intended to remain in place only a week, was dismantled in January 1920, its condition having deteriorated severely. The work was carried out behind a screen to shield the partially dismantled monument from public view.Clouting, p. 160. The top section, along with the flags, was preserved for the fledgling Imperial War Museum

Imperial War Museums (IWM) is a British national museum organisation with branches at five locations in England, three of which are in London. Founded as the Imperial War Museum in 1917, the museum was intended to record the civil and military ...

(founded in 1917), as part of its exhibition on the war. The acquisition was the idea of Charles ffoulkes

Charles John ffoulkes (1868–1947) was a British historian, and curator of the Royal Armouries at London. He was a younger son of the Reverend Edmund Ffoulkes, Edmund ffoulkes. He wrote extensively on medieval weapon, arms and armour.

ffoulkes ...

, the museum's inaugural curator. It was displayed prominently, and was used for the museum's own remembrance services in the interwar period until it was destroyed by a bomb during the Second World War. The Imperial War Museum collections also include a wooden money-collection box in the shape of the Cenotaph, made from part of the temporary Cenotaph by St Dunstan's.

Design

The Cenotaph is made from

The Cenotaph is made from Portland stone

Portland stone is a limestone from the Tithonian stage of the Jurassic period quarried on the Isle of Portland, Dorset. The quarries are cut in beds of white-grey limestone separated by chert beds. It has been used extensively as a building sto ...

formed as a pylon on a rectangular plan (two long sides and two short ones), with gradually diminishing tiers, culminating in a sculpted tomb chest (the empty tomb suggested by the name ''cenotaph'') on which is carved laurel wreath

A laurel wreath is a round wreath made of connected branches and leaves of the bay laurel (), an aromatic broadleaf evergreen, or later from spineless butcher's broom (''Ruscus hypoglossum'') or cherry laurel (''Prunus laurocerasus''). It is a sy ...

. The structure rises to a height of just over and is about at the base. Lutyens described it as "an empty tomb uplifted on a high pedestal".

The pylon's mass decreases with its height; the sides becoming narrower towards the bottom of the coffin. The base is in four stages from the top of the steps starting with the plinth, which connects to the base block. The plinth projects from the base block on all four sides. Above it is the transition moulding which is in three stages—torus

In geometry, a torus (plural tori, colloquially donut or doughnut) is a surface of revolution generated by revolving a circle in three-dimensional space about an axis that is coplanar with the circle.

If the axis of revolution does not tou ...

(semi-circular), cyma reversa

Moulding (spelled molding in the United States), or coving (in United Kingdom, Australia), is a strip of material with various profiles used to cover transitions between surfaces or for decoration. It is traditionally made from solid milled woo ...

, and cavetto

A cavetto is a concave moulding with a regular curved profile that is part of a circle, widely used in architecture as well as furniture, picture frames, metalwork and other decorative arts. In describing vessels and similar shapes in pottery, ...

—taking the lower part of the structure just over above the ground. Greenberg describes this section as "quietly establish ngthe memorial's overall character: an outward appearance of simple repose which, on close observation, shows itself to be dependent on the more complex forms of its masses".

At the top, the coffin is connected to the main structure by its own base of two steps, the transition smoothed by a torus moulding between the bottom step and the pylon. The coffin lid finishes with a cornice

In architecture, a cornice (from the Italian ''cornice'' meaning "ledge") is generally any horizontal decorative moulding that crowns a building or furniture element—for example, the cornice over a door or window, around the top edge of a ...

, appearing to be supported by an ovolo

The ovolo or echinus is a convex decorative molding profile used in architectural ornamentation. Its profile is a quarter to a half of a more or less flattened circle.

The 1911 edition of ''Encyclopædia Britannica'' says:adapted from Ital. ''u ...

(a curved decorative moulding beneath the edge), which casts a shadow over the coffin; it is crowned by a laurel wreath. The bottom of the structure is mounted onto three diminishing steps on an island in the centre of Whitehall surrounded by government buildings. The monument is austere, containing very little decoration. At each end, on the second tier below the tomb, is a laurel wreath, echoing the one at the top, and on the sides is the inscription "". The only other inscription is the dates of the world wars in Roman numerals—the first on the ends, above the wreath, and the second on the sides. The sculptural work was carried out by Derwent Wood.Archer, p. 166.

None of the lines on the pylon is straight. The sides are not parallel but are subtly curved using precise geometry so as to be barely visible to the naked eye (entasis). If extended, the apparently vertical surfaces would meet above the ground and the apparently horizontal surfaces are sections of a sphere whose centre would be below ground.Borg, pp. 74–75. The use of curvature and diminishing tiers is intended to draw the eye upwards in a spiralling direction, first to the inscription, then to the top of the flags, to the wreath, and finally to the coffin at the top. Many of these elements were not present in Lutyens's early design, and the progression can be seen in several of the architect's sketches. In his sketch for Lady Sackville, he omitted most of the setbacks, and had the wreaths on the sides hanging from pegs. In another drawing he included an urn

An urn is a vase, often with a cover, with a typically narrowed neck above a rounded body and a footed pedestal. Describing a vessel as an "urn", as opposed to a vase or other terms, generally reflects its use rather than any particular shape or ...

on top of the coffin and sculptures of lions flanking the base (similar to the pine cones on Southampton Cenotaph). Other experimental designs omit the flags, and one included a recumbent effigy

A tomb effigy, usually a recumbent effigy or, in French, ''gisant'' ( French, "lying"), is a sculpted figure on a tomb monument depicting in effigy the deceased. These compositions were developed in Western Europe in the Middle Ages, and ...

atop the coffin (in place of an urn). A wooden model from an early stage in the design process is in the collection of the Imperial War Museum, as are several of Lutyens's original drawings; others are in the Royal Institute of British Architects

The Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) is a professional body for architects primarily in the United Kingdom, but also internationally, founded for the advancement of architecture under its royal charter granted in 1837, three suppl ...

' drawing library.

The Cenotaph is flanked on the long sides by flags of the United Kingdom—the

The Cenotaph is flanked on the long sides by flags of the United Kingdom—the Royal Air Force Ensign

The Royal Air Force Ensign is the official flag which is used to represent the Royal Air Force. The ensign has a field of air force blue with the United Kingdom's flag in the canton and the Royal Air Force's roundel in the middle of the fly. ...

, Union Flag

The Union Jack, or Union Flag, is the ''de facto'' national flag of the United Kingdom. Although no law has been passed making the Union Flag the official national flag of the United Kingdom, it has effectively become such through precedent. ...

, and Red Ensign on one side, and the Blue Ensign

The Blue Ensign is a flag, one of several British ensigns, used by certain organisations or territories associated or formerly associated with the United Kingdom. It is used either plain or Defacement (flag), defaced with a Heraldic badge, ...

, Union Flag, and White Ensign

The White Ensign, at one time called the St George's Ensign due to the simultaneous existence of a cross-less version of the flag, is an ensign worn on British Royal Navy ships and shore establishments. It consists of a red St George's Cross on ...

on the other. Lutyens intended the flags to be carved in stone like the rest of the monument. He was overruled and cloth flags were used, though Lutyens went on to use stone flags on several of his other war memorials, painted on Rochdale Cenotaph

Rochdale Cenotaph is a First World War memorial on the Esplanade in Rochdale, Greater Manchester, in the north west of England. Designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens, it is one of seven memorials in England based on his Cenotaph in London and one of hi ...

and Northampton War Memorial

Northampton War Memorial, officially the Town and County War Memorial, is a First World War memorial on Wood Hill in the centre of Northampton, the county town of Northamptonshire, in central England. Designed by architect Sir Edwin Lutyens, i ...

(among others), and unpainted at Étaples

Étaples or Étaples-sur-Mer (; vls, Stapel, lang; pcd, Étape) is a commune in the Pas-de-Calais department in northern France. It is a fishing and leisure port on the Canche river.

History

Étaples takes its name from having been a medieval ...

and Villers-Bretonneux

Villers-Bretonneux () is a commune in the Somme department in Hauts-de-France in northern France.

Geography

Villers-Bretonneux is situated some 19 km due east of Amiens, on the D1029 road and the A29 motorway.

Villers-Bretonneux border ...

IWGC cemeteries.

Appreciation

On the day of its unveiling, ''The Times'' praised the Cenotaph as "simple, massive, unadorned". Catherine Moriarty, of the Imperial War Museum's National Inventory of War Memorials project, observed in 1995 that the Cenotaph met with widespread public acclaim, and that the public adopted the unfamiliar name with enthusiasm. She described an empty tomb as a highly appropriate monument for the experience of the British public, considering that the vast majority of the British dead were buried overseas. Nonetheless, Moriarty believed that the Cenotaph, "...although popular, was too abstract in form and generalised in its commemorative allusion to fully satisfy the need for a focus of grief." This, Moriarty felt, was the reason that many local memorials, including some by Lutyens, adopted some form of figurative sculpture, such as a statue of a soldier.Moriarty, p. 15. According to the historian Alex King, the Cenotaph fitted the convention of ashrine

A shrine ( la, scrinium "case or chest for books or papers"; Old French: ''escrin'' "box or case") is a sacred or holy sacred space, space dedicated to a specific deity, ancestor worship, ancestor, hero, martyr, saint, Daemon (mythology), daem ...

, such as the temporary memorials to the dead established across London during the war, including the Hyde Park shrine. King believed that the public response, particularly the laying of flowers, treated the Cenotaph as a shrine—a place for paying respects to the dead. Nonetheless, the austerity and apparent simplicity of the Cenotaph leaves its meaning open to a wide variety of interpretations, not all of which have been in keeping with Lutyens's intentions. Some ascribed imperialistic or nationalistic meanings to the monument, including Haig, who called it "a symbol of the empire's unity".King, p. 147. The ''Catholic Herald

The ''Catholic Herald'' is a London-based Roman Catholic monthly newspaper and starting December 2014 a magazine, published in the United Kingdom, the Republic of Ireland and, formerly, the United States. It reports a total circulation of abo ...

'' called it a "pagan monument" and felt that it was insulting to Christianity, and other traditional Christian groups were displeased by the lack of religious symbolism.Winter, p. 104. Lutyens was a pantheist

Pantheism is the belief that reality, the universe and the cosmos are identical with divinity and a supreme supernatural being or entity, pointing to the universe as being an immanent creator deity still expanding and creating, which has ex ...

, heavily influenced by his wife's involvement with Theosophy

Theosophy is a religion established in the United States during the late 19th century. It was founded primarily by the Russian Helena Blavatsky and draws its teachings predominantly from Blavatsky's writings. Categorized by scholars of religion a ...

. He opposed overt religious symbolism on the Cenotaph and in his work with the IWGC, a position which did not endear him to the church.

Roderick Gradidge, an architect and author of a biography of Lutyens, commented on Lutyens's use of geometry—"He utyensrecognised that in this careful proportioning system he had hit on something that people could recognise though never understand; a sort of music of the spheres which expressed what they felt about the horrifying destruction ..both of human life and the shape of society itself."

The American historian Jay Winter

Jay Murray Winter (born May 28, 1945) is an American historian. He is the Charles J. Stille Professor of History at Yale University, where he focuses his research on World War I and its impact on the 20th century. His other interests include re ...

described the Cenotaph as displaying a "striking minimalism". According to Winter, the Cenotaph "managed to transform a victory parade ..into a time when millions could contemplate the ..inexorable reality of death in war," and was "a work of genius because of its simplicity. It says so much because it says nothing at all. It is a form on which anyone could inscribe his or her own thoughts, reveries, sadness." He believed that, in designing an empty tomb, "the tomb of no one ..became the tomb of all who had died in the war." He compared it favourably to another of Lutyens's major commemorative works, the Thiepval Memorial

The Thiepval Memorial to the Missing of the Somme is a war memorial to 72,337 missing British and South African servicemen who died in the Battles of the Somme of the First World War between 1915 and 1918, with no known grave. It is near the ...

, built for the IWGC in France, and to Maya Lin

Maya Ying Lin (born October 5, 1959) is an American designer and sculptor. In 1981, while an undergraduate at Yale University, she achieved national recognition when she won a national design competition for the planned Vietnam Veterans Memoria ...

's Vietnam Veterans Memorial

The Vietnam Veterans Memorial is a U.S. national memorial in Washington, D.C., honoring service members of the U.S. armed forces who served in the Vietnam War. The site is dominated by two black granite walls engraved with the names of those s ...

in Washington, DC. Jenny Edkins

Jenny Edkins is a British political scientist, Professor of Politics at the University of Manchester.

Life

Edkins gained degrees from University of Oxford, City, University of London and the Open University. She gained her PhD, on theories of i ...

, a British political scientist, also draws a parallel between the Cenotaph and the Vietnam Memorial and the unexpected public acclaim that both received immediately after their unveiling. Edkins believed that the apparent simplicity of, and lack of decoration on, the two memorials provided for a "collective act of mourning". Another architect, Andrew Crompton, of the University of Liverpool

, mottoeng = These days of peace foster learning

, established = 1881 – University College Liverpool1884 – affiliated to the federal Victoria Universityhttp://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukla/2004/4 University of Manchester Act 200 ...

, re-evaluated the Cenotaph at the turn of the 21st century. He compared the diminishing tiers (when viewed from the ground up) to the hilt of a sheathed sword, its blade buried beneath the ground, which he felt resembled the mythical sword Excalibur

Excalibur () is the legendary sword of King Arthur, sometimes also attributed with magical powers or associated with the rightful sovereignty of Britain. It was associated with the Arthurian legend very early on. Excalibur and the Sword in th ...

.Crompton, pp. 64–67.

The Cenotaph has been contrasted with the Royal Artillery Memorial

The Royal Artillery Memorial is a First World War memorial located on Hyde Park Corner in London, England. Designed by Charles Sargeant Jagger, with architectural work by Lionel Pearson, and unveiled in 1925, the memorial commemorates the 49,076 ...

by Charles Sargeant Jagger

Charles Sargeant Jagger (17 December 1885 – 16 November 1934) was a British sculptor who, following active service in the First World War, sculpted many works on the theme of war. He is best known for his war memorials, especially the Royal A ...

. Lutyens submitted a proposed design for that memorial, but the Royal Artillery rejected it on the grounds that it was too similar to the Cenotaph, and that they wanted a more realist monument, rather than Lutyens's abstract classicism

Classicism, in the arts, refers generally to a high regard for a classical period, classical antiquity in the Western tradition, as setting standards for taste which the classicists seek to emulate. In its purest form, classicism is an aestheti ...

. Whereas Lutyens placed the empty coffin high above the ground, distancing the observer from it, Jagger sculpted a dead soldier and placed it at eye level, confronting the observer with the reality of war. The Tomb of the Unknown Warrior

The British grave of the Unknown Warrior (often known as 'The Tomb of the Unknown Warrior') holds an unidentified member of the British armed forces killed on a European battlefield during the First World War.Hanson, Chapters 23 & 24 He was gi ...

in Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

, inaugurated on the same day as the Cenotaph and another of London's most famous war memorials, has also been contrasted with the Cenotaph. Edkins observes that the Tomb was intended to "provide a grave for those who had none" and to become a focal point for the mourning of those buried overseas, but that the Cenotaph became much more popular as a site for both individual commemoration and public ceremonies.

The German-American historian George Mosse

Gerhard "George" Lachmann Mosse (September 20, 1918 – January 22, 1999) was an American historian, who emigrated from Nazi Germany first to Great Britain and then to the United States. He was professor of history at the University of Iowa, the ...

noted that most countries involved in the First World War eventually adopted the concept of burying an unidentified soldier, but in London the Cenotaph fulfilled the same purpose, despite the tomb in the abbey. Unlike elsewhere, it was the Cenotaph and not an unknown warrior that became the centre of national ceremonies, which Mosse considered was because the abbey was "too cluttered with memorials and tombs of famous Englishmen to provide the appropriate place for pilgrimages or celebrations" compared to the Cenotaph's location in the middle of a broad avenue. Ken Inglis

Kenneth Stanley Inglis, (7 October 1929 – 1 December 2017) was an Australian historian.

Early life and education

Inglis was born in the Melbourne suburb of Ivanhoe, on 7 October 1929, the son of Stan and Rene Inglis. He was educated at Tyler ...

, an Australian historian, and Gavin Stamp

Gavin Mark Stamp (15 March 194830 December 2017) was a British writer, television presenter and architectural historian.

Education

Stamp was educated at Dulwich College in South London from 1959 to 1967 as part of the "Dulwich Experiment", then a ...

, a British architectural historian, both suggested that the Unknown Warrior was the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

's attempt to create a rival to the Cenotaph, which had no explicitly Christian symbolism, though another historian, David Lloyd, suggests that this was largely unsuccessful—the Church even petitioned for Armistice Day ceremonies to be held in Westminster Abbey rather than at the Cenotaph in 1923, but the proposal was rejected after it met with widespread public opposition.Stamp, p. 43. Instead, Lloyd noted that the two monuments became closely linked, and that "Together, the memorials reflect the complexity and ambiguity of the British response to the Great War."

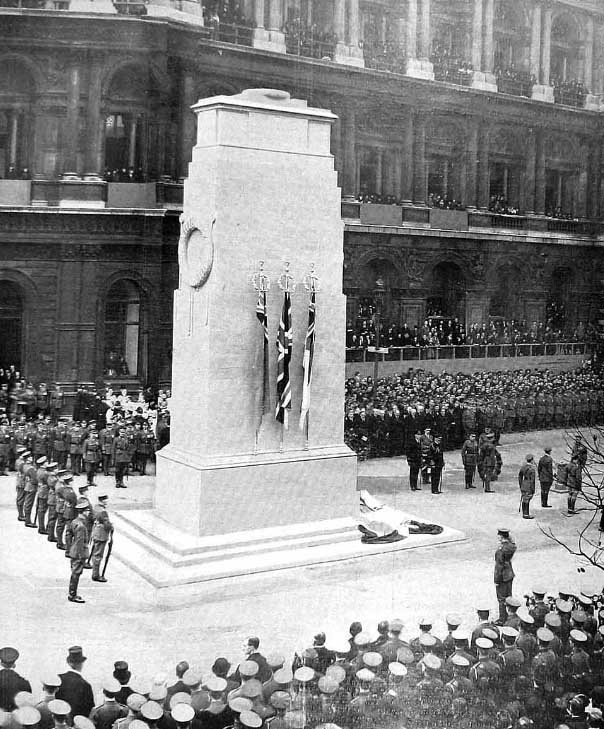

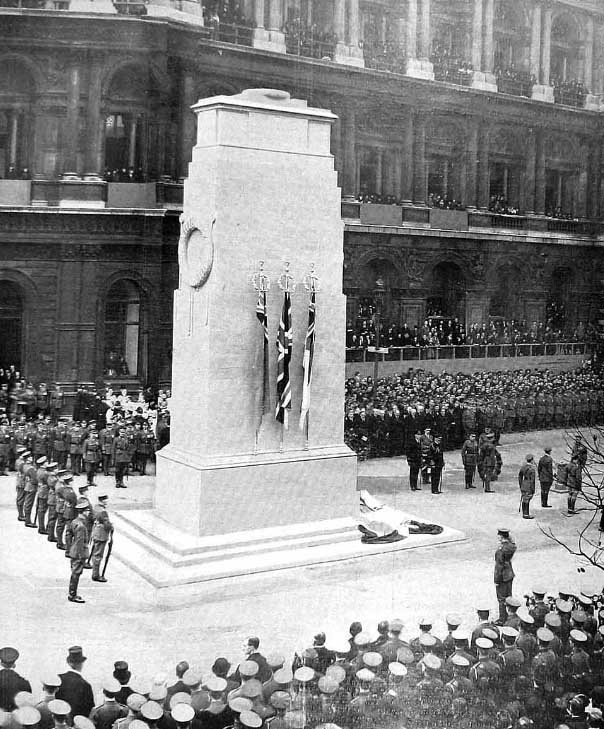

Unveiling

No date was announced for the completion of the Cenotaph at first, but the British government was keen to have it in place for

No date was announced for the completion of the Cenotaph at first, but the British government was keen to have it in place for Remembrance Day

Remembrance Day (also known as Poppy Day owing to the tradition of wearing a remembrance poppy) is a memorial day observed in Commonwealth member states since the end of the First World War to honour armed forces members who have died in t ...

(11 November). In September 1920, the announcement came that the Cenotaph would be unveiled on 11 November, the second anniversary of the armistice, and that the unveiling would be performed by King George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until his death in 1936.

Born during the reign of his grandmother Que ...

.Skelton, p. 47. For the occasion, the government designated the Cenotaph the official memorial to all British and empire dead lost during the First World War. It subsequently became the official memorial to British casualties from later conflicts.

Late into the planning, the government decided to exhume an unidentified serviceman—thenceforth to be known as the Unknown Warrior

The British grave of the Unknown Warrior (often known as 'The Tomb of the Unknown Warrior') holds an unidentified member of the British armed forces killed on a European battlefield during the First World War.Hanson, Chapters 23 & 24 He was gi ...

—from a grave in France, and inter him in Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

. The last leg of the Unknown Warrior's journey to the abbey took place in coordination with events at the Cenotaph. The king was to unveil the Cenotaph, this time with Lutyens in attendance, along with other members of the royal family, the prime minister, and Randall Davidson

Randall Thomas Davidson, 1st Baron Davidson of Lambeth, (7 April 1848 – 25 May 1930) was an Anglican priest who was Archbishop of Canterbury from 1903 to 1928. He was the longest-serving holder of the office since the English Reformation, Re ...

, the Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. The current archbishop is Justi ...

(the Church of England's most senior cleric). The Unknown Warrior was brought to Whitehall, his coffin resting on a gun carriage pulled by military horses, for the unveiling. The Cenotaph was shrouded in Union Flags until the king performed the unveiling at the stroke of 11 o'clock. This ceremonial act was followed by two minutes' silence, ending with the sounding of the "Last Post

The "Last Post" is either an A or a B♭ bugle call, primarily within British infantry and Australian infantry regiments, or a D or an E♭ cavalry trumpet call in British cavalry and Royal Regiment of Artillery (Royal Horse Artillery and R ...

". The king placed a wreath of roses on the Unknown Warrior's coffin, and the cortege continued its journey—His Majesty, the other royals, Lloyd George, and the archbishop following the gun carriage to the abbey.

The public response exceeded even that to the temporary Cenotaph in the aftermath of the armistice. Whitehall was closed to traffic for several days after the ceremony and wounded soldiers, other veterans, and members of the public began to file past the Cenotaph and lay flowers at its base. The volume of people wishing to lay tributes was such that there were delays of up to four hours to pass the Cenotaph; the procession continued through the night and into the next day. Within a week, the Cenotaph was deep in flowers and an estimated 1.25million people had visited it so far, while 500,000 had visited the Tomb of the Unknown Warrior. Lloyd George wrote to Lutyens, "The Cenotaph is the token of our mourning as a nation; the Grave of the Unknown Warrior is the token of our mourning as individuals."

Later history

Alfred Rosenberg

Alfred Ernst Rosenberg ( – 16 October 1946) was a Baltic German Nazi theorist and ideologue. Rosenberg was first introduced to Adolf Hitler by Dietrich Eckart and he held several important posts in the Nazi government. He was the head of ...

, representing Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

, controversially laid a wreath at the Cenotaph. The accompanying card was removed overnight and the swastika

The swastika (卐 or 卍) is an ancient religious and cultural symbol, predominantly in various Eurasian, as well as some African and American cultures, now also widely recognized for its appropriation by the Nazi Party and by neo-Nazis. It ...

on the wreath was scratched off. The following day, Captain James Sears, a First World War veteran and prospective Labour Party parliamentary candidate, removed the entire wreath and threw it in the river. He described his actions as "a deliberate protest against the desecration of our national war memorial" and against the views of the Nazi Party, which he believed were the same as those Britain had fought against. Sears was arrested, charged with malicious damage, and fined. Some newspaper columnists and letter writers sympathised with Sears's actions, though others felt that his actions themselves desecrated the Cenotaph by using it to make a political statement.

Following the Second World War, the Cenotaph was rededicated to include the British and empire dead from that war, and its dates in Roman numerals (MCMXXXIX and MCMXLV) were added to the inscription. King George VI

George VI (Albert Frederick Arthur George; 14 December 1895 – 6 February 1952) was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 until Death and state funeral of George VI, his death in 1952. ...

unveiled the additions at a ceremony on 10 November 1946. No separate national memorial was built for the casualties of the second war; instead, remembrance services were expanded to commemorate the new dead, and veterans of that war and later conflicts joined an annual march-past.

Several political protests have taken place in the vicinity of the Cenotaph. In 2000, anti-capitalist protesters spray-painted slogans on it and on a statue of Winston Churchill. In a 2010 student protest, a man climbed the base and swung from one of the flags. In June 2020, the base was vandalised with spray paint during Black Lives Matter protests, and the following day a protester attempted to set fire to one of the Union Flags on the Cenotaph. The Cenotaph and several other monuments were covered up temporarily to prevent any further vandalism, though a group of far-right counter-protesters congregated around it a few days later. On 11 November 2020, Extinction Rebellion

Extinction Rebellion (abbreviated as XR) is a global environmental movement, with the stated aim of using nonviolent civil disobedience to compel government action to avoid tipping points in the climate system, biodiversity loss, and the risk o ...

held an unauthorised protest at the Cenotaph that was condemned by politicians and the Royal British Legion

The Royal British Legion (RBL), formerly the British Legion, is a British charity providing financial, social and emotional support to members and veterans of the British Armed Forces, their families and dependants, as well as all others in ne ...

.

In 2013, just before the centenary of the First World War

The First World War centenary was the centenary of the First World War, which began on 28 July 2014 with a series of commemorations of the outbreak of the war organised across the continent of Europe, and ended on 11 November 2018 with the cent ...

, English Heritage

English Heritage (officially the English Heritage Trust) is a charity that manages over 400 historic monuments, buildings and places. These include prehistoric sites, medieval castles, Roman forts and country houses.

The charity states that i ...

carried out £60,000 of restoration work on the Cenotaph. Contractors cleaned the stonework using steam and a poultice

A poultice, also called a cataplasm, is a soft moist mass, often heated and medicated, that is spread on cloth and placed over the skin to treat an aching, inflamed, or painful part of the body. It can be used on wounds, such as cuts.

'Poultice' ...

to remove dirt and algae and counter the effects of weathering and pollution. Somewhat controversially, the German president, Frank-Walter Steinmeier

Frank-Walter Steinmeier (; born 5 January 1956) is a German politician serving as President of Germany since 19 March 2017. He was previously Federal Minister of Foreign Affairs from 2005 to 2009 and again from 2013 to 2017, as well as Vice Chan ...

, was invited to lay a wreath at the Cenotaph on Remembrance Sunday 2018 to mark the centenary of the armistice, the first time a German representative had been present at the commemorations.

Remembrance services

The Cenotaph is the focal point for theNational Service of Remembrance

The National Service of Remembrance is held every year on Remembrance Sunday at the Cenotaph on Whitehall, London. It commemorates "the contribution of British and Commonwealth military and civilian servicemen and women in the two World Wars and l ...

held annually on Remembrance Sunday

Remembrance Sunday is held in the United Kingdom as a day to commemorate the contribution of British and Commonwealth military and civilian servicemen and women in the two World Wars and later conflicts. It is held on the second Sunday in Nov ...

, the closest Sunday to 11 November. In the Cenotaph's early years, the service was informal and crowds gathered round the memorial to pay their respects and lay tributes, but the ceremony gradually became more formal, and has changed little since the 1930s. Whitehall is closed to vehicle traffic and a two-minute silence is observed at 11:00am. After the silence, the crowd sings traditional hymns, accompanied by military musicians. The monarch and the prime minister (or their representatives) then lay wreaths at the Cenotaph, followed by other members of the royal family, politicians, and Commonwealth high commissioners. Afterwards, serving military personnel, veterans' associations, and other organisations march past and lay their own wreaths. Until the Second World War, the service was held on 11 November. It was moved to a Sunday to avoid interrupting wartime production, and has been held on a Sunday ever since.Greenberg, p. 5. According to Paul Fussell

Paul Fussell Jr. (22 March 1924 – 23 May 2012) was an American cultural and literary historian, author and university professor. His writings cover a variety of topics, from scholarly works on eighteenth-century English literature to commentar ...

, an American literary historian specialising in the cultural effects of the world wars, "to sense the British obsession with the Great War, all that is necessary is to stand at the Cenotaph ..on any Remembrance Sunday and listen to the two minutes of silence," which he describes as "appropriately shocking in the context of the customary hum of traffic."

Other annual ceremonies are also held at the Cenotaph, such as commemorations by individual regiments or veterans' associations, or on anniversaries such as Anzac Day

, image = Dawn service gnangarra 03.jpg

, caption = Anzac Day Dawn Service at Kings Park, Western Australia, 25 April 2009, 94th anniversary.

, observedby = Australia Christmas Island Cocos (Keeling) Islands Cook Islands New ...

(25 April). In 2000, relatives of soldiers executed for desertion or cowardice during the First World War joined the Remembrance Sunday parade for the first time, and in 2014 a representative of the Irish government laid a wreath on Remembrance Sunday for the first time, in memory of Irishmen who fought in the British armed forces in the First World War.

The BBC #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC

Here i going to introduce about the best teacher of my life b BALAJI sir. He is the precious gift that I got befor 2yrs . How has helped and thought all the concept and made my success in the 10th board ex ...

began broadcasting special radio programming for Armistice Day in 1923, and began broadcasting the events at the Cenotaph live from 1928. Radio broadcasting enabled the silence to be observed simultaneously across the country, and allowed millions of listeners to feel part of the ceremony. The BBC began broadcasting television pictures of the ceremony from 1937. The broadcast has run almost continually since its inception, interrupted only for the Second World War, making it one of the longest-running annual broadcasts in the world.

Heritage status

The Cenotaph was designated a grade Ilisted building

In the United Kingdom, a listed building or listed structure is one that has been placed on one of the four statutory lists maintained by Historic England in England, Historic Environment Scotland in Scotland, in Wales, and the Northern Irel ...

on 5 February 1970. Listing provides legal protection from unauthorised demolition or modification. Grade I is the highest possible grade, reserved for buildings of "exceptional" historical or architectural interest and applied to 2.5 per cent of listings. The Cenotaph is in the care of English Heritage

English Heritage (officially the English Heritage Trust) is a charity that manages over 400 historic monuments, buildings and places. These include prehistoric sites, medieval castles, Roman forts and country houses.

The charity states that i ...

, which manages historic buildings for the nation. To mark the centenary of the First World War, Historic England

Historic England (officially the Historic Buildings and Monuments Commission for England) is an executive non-departmental public body of the British Government sponsored by the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport. It is tasked wit ...

conducted research into war memorials with the aim of listing 2,500. As part of the project, they identified 44 freestanding war memorials in England designed by Lutyens, which they declared to be a national collection. All 44 are listed buildings and had their list entries enhanced with new research; five (including Southampton) were upgraded to grade I on Remembrance Sunday 2014, joining the Cenotaph and the Arch of Remembrance

The Arch of Remembrance is a First World War memorial designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens and located in Victoria Park, Leicester, in the East Midlands of England. Leicester's industry contributed significantly to the British war effort. A temporary ...

in Leicester

Leicester ( ) is a city status in the United Kingdom, city, Unitary authorities of England, unitary authority and the county town of Leicestershire in the East Midlands of England. It is the largest settlement in the East Midlands.

The city l ...

.

Impact

On Lutyens

The renowned architectural historianNikolaus Pevsner

Sir Nikolaus Bernhard Leon Pevsner (30 January 1902 – 18 August 1983) was a German-British art historian and architectural historian best known for his monumental 46-volume series of county-by-county guides, ''The Buildings of England'' (1 ...

described the Cenotaph as "the chief national war memorial". Gavin Stamp

Gavin Mark Stamp (15 March 194830 December 2017) was a British writer, television presenter and architectural historian.

Education

Stamp was educated at Dulwich College in South London from 1959 to 1967 as part of the "Dulwich Experiment", then a ...

, a British architectural historian and the author of Lutyens's entry in the ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

The ''Dictionary of National Biography'' (''DNB'') is a standard work of reference on notable figures from British history, published since 1885. The updated ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (''ODNB'') was published on 23 September ...

'', wrote that Lutyens's work commemorating the British war dead (the Cenotaph, his work with the IWGC and his memorial commissions elsewhere) was responsible for Lutyens's elevation to the status of a national figure. A few days after the unveiling, Lloyd George wrote to Lutyens: "the Cenotaph, by its very simplicity, fittingly expresses the memory in which the people hold all those who so bravely fought and died" in the war. In 1921, Lutyens was awarded the Royal Institute of British Architects

The Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) is a professional body for architects primarily in the United Kingdom, but also internationally, founded for the advancement of architecture under its royal charter granted in 1837, three suppl ...

' highest award, the Royal Gold Medal

The Royal Gold Medal for architecture is awarded annually by the Royal Institute of British Architects on behalf of the British monarch, in recognition of an individual's or group's substantial contribution to international architecture. It is g ...

, for his body of work. Presenting the medal, the institute's president, John Simpson, described the Cenotaph as "the most remarkable of all utyens'screations ..austere yet gracious, technically perfect, it is the very expression of repressed emotion, of massive simplicity of purpose, of the qualities which mark those whom it commemorates and those who raised it."

According to Jane Brown, in her biography of the architect, Lutyens was faced with a "constant stream" of war memorial commissions from the unveiling of the temporary Cenotaph until at least 1924. He went on to design more than 130 war memorials and cemeteries, many influenced by his work on the Cenotaph. His Southampton Cenotaph was unveiled in 1920, while the permanent monument on Whitehall was still under construction. His later cenotaphs include Rochdale, Manchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of Salford to the west. The t ...

, and the Midland Railway War Memorial