The Carnegie Endowment For International Peace on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (CEIP) is a nonpartisan

At the outset of America's involvement in

At the outset of America's involvement in

Online

''Foreign Policy''

*

''Pro et Contra''

{{DEFAULTSORT:Carnegie Endowment For International Peace Andrew Carnegie Dupont Circle Peace organizations based in the United States Foreign policy and strategy think tanks in the United States Political and economic think tanks in the United States Embassy Row 1910 establishments in the United States

international affairs

International relations (IR), sometimes referred to as international studies and international affairs, is the scientific study of interactions between sovereign states. In a broader sense, it concerns all activities between states—such as ...

think tank

A think tank, or policy institute, is a research institute that performs research and advocacy concerning topics such as social policy, political strategy, economics, military, technology, and culture. Most think tanks are non-governmenta ...

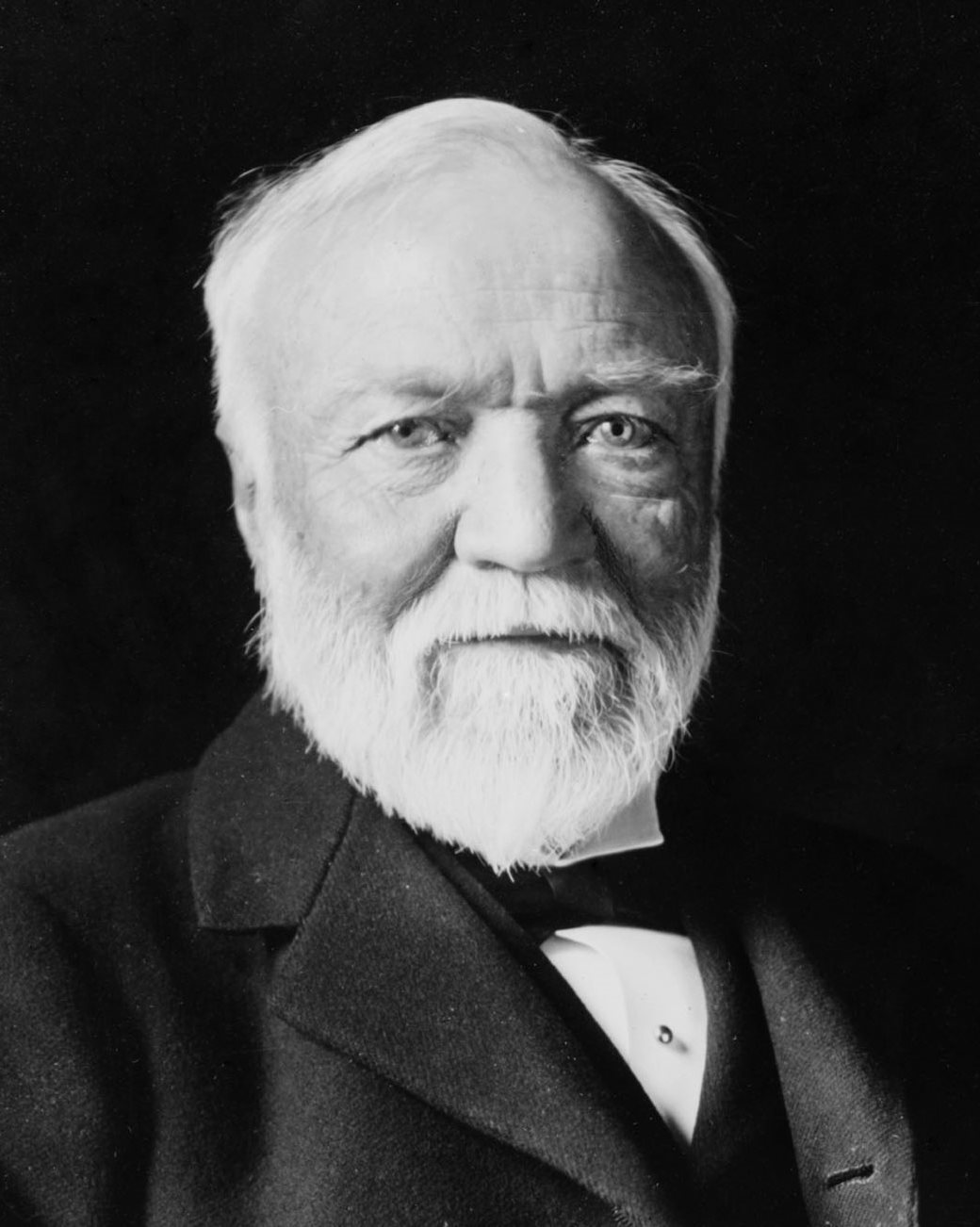

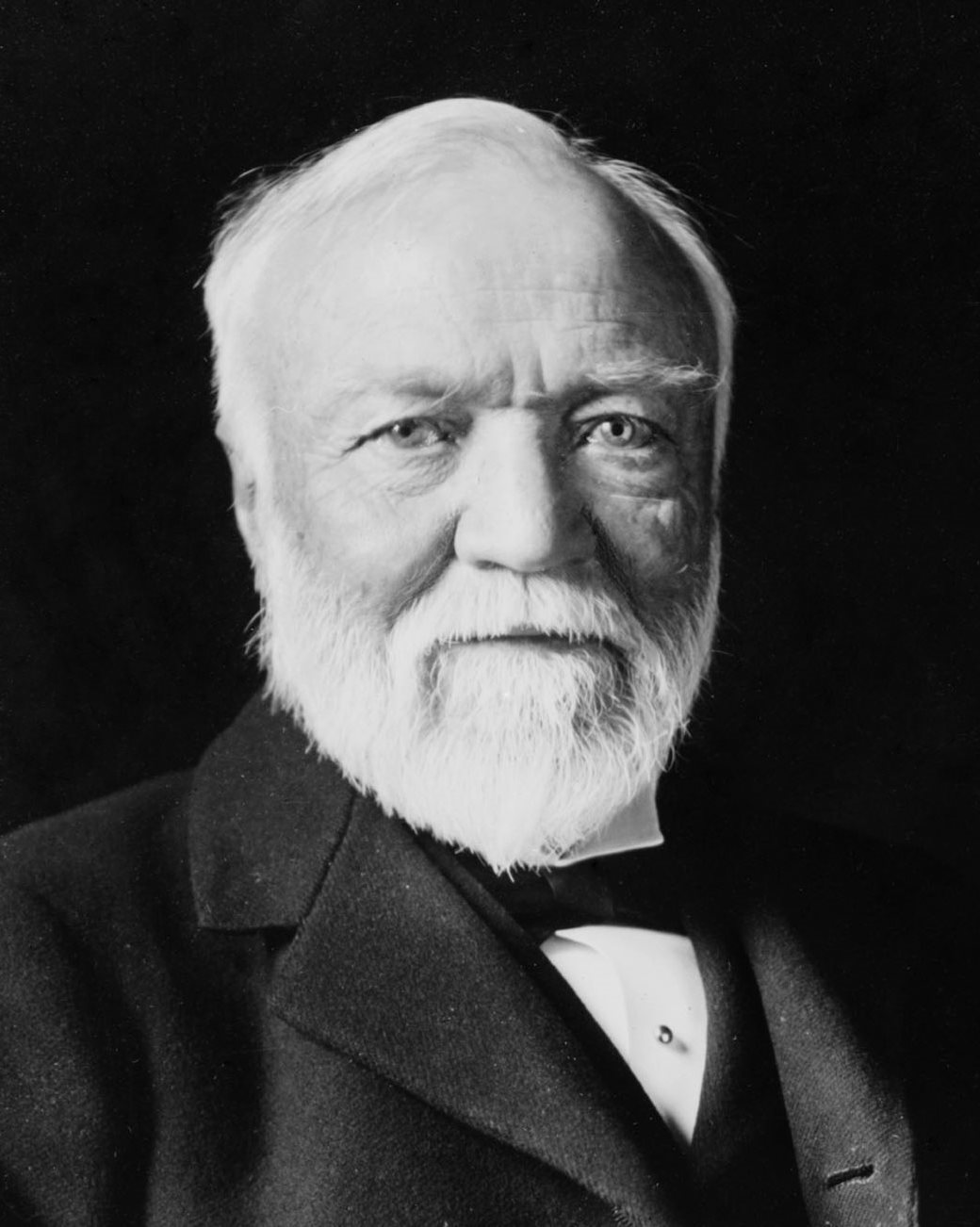

headquartered in Washington D.C. with operations in Europe, South and East Asia, and the Middle East as well as the United States. Founded in 1910 by Andrew Carnegie

Andrew Carnegie (, ; November 25, 1835August 11, 1919) was a Scottish-American industrialist and philanthropist. Carnegie led the expansion of the American steel industry in the late 19th century and became one of the richest Americans i ...

, the organization describes itself as being dedicated to advancing cooperation between countries, reducing global conflict

Global means of or referring to a globe and may also refer to:

Entertainment

* ''Global'' (Paul van Dyk album), 2003

* ''Global'' (Bunji Garlin album), 2007

* ''Global'' (Humanoid album), 1989

* ''Global'' (Todd Rundgren album), 2015

* Bruno ...

, and promoting active international engagement by the United States and countries around the world.

In the University of Pennsylvania

The University of Pennsylvania (also known as Penn or UPenn) is a private research university in Philadelphia. It is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and is ranked among the highest-regarded universitie ...

's "2019 Global Go To Think Tanks Report", Carnegie was ranked the number 1 top think tank in the world. In the ''2015 Global Go To Think Tanks Report'', Carnegie was ranked the third most influential think tank in the world, after the Brookings Institution

The Brookings Institution, often stylized as simply Brookings, is an American research group founded in 1916. Located on Think Tank Row in Washington, D.C., the organization conducts research and education in the social sciences, primarily in ec ...

and Chatham House. It was ranked as the top Independent Think Tank in 2018.

Its headquarters building, prominently located on the Embassy Row

Embassy Row is the informal name for a section of Northwest Washington, D.C. with a high concentration of embassies, diplomatic missions, and diplomatic residences. It spans Massachusetts Avenue N.W. between 18th and 35th street, bounded by ...

section of Massachusetts Avenue Massachusetts Avenue may refer to:

* Massachusetts Avenue (metropolitan Boston), Massachusetts

** Massachusetts Avenue (MBTA Orange Line station), a subway station on the MBTA Orange Line

** Massachusetts Avenue (MBTA Silver Line station), a stati ...

, was completed in 1989 on a design by architecture firm Smith, Hinchman & Grylls

SmithGroup is an international architectural, engineering and planning firm. Established in Detroit in 1853 by architect Sheldon Smith, SmithGroup is the longest continually operating architecture and engineering firm in the United States that ...

. It has also hosted the embassy of Papua New Guinea

Papua New Guinea (abbreviated PNG; , ; tpi, Papua Niugini; ho, Papua Niu Gini), officially the Independent State of Papua New Guinea ( tpi, Independen Stet bilong Papua Niugini; ho, Independen Stet bilong Papua Niu Gini), is a country i ...

in the U.S.

The chairperson of Carnegie's board of trustees is former U.S. Secretary of Commerce

The United States secretary of commerce (SecCom) is the head of the United States Department of Commerce. The secretary serves as the principal advisor to the president of the United States on all matters relating to commerce. The secretary rep ...

Penny Pritzker

Penny Sue Pritzker (born May 2, 1959) is an American billionaire businesswoman and civic leader who served as the 38th United States secretary of commerce in the Obama administration from 2013 to 2017. She was confirmed by a Senate vote of 97� ...

, and the organization's president is former judge Mariano-Florentino Cuéllar

Mariano-Florentino "Tino" Cuéllar (born July 27, 1972) is an American scholar, academic leader, public official, jurist, and nonprofit executive currently serving as the 10th president of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. A former ...

, who replaced CIA Director William J. Burns

William John Burns (October 19, 1861 – April 14, 1932) was an American private investigator and law enforcement official. He was known as "America's Sherlock Holmes" and earned fame for having conducted private investigations into a number of ...

in 2021.

Organizational history

Establishment

Andrew Carnegie

Andrew Carnegie (, ; November 25, 1835August 11, 1919) was a Scottish-American industrialist and philanthropist. Carnegie led the expansion of the American steel industry in the late 19th century and became one of the richest Americans i ...

, like other leading internationalists Internationalists may refer to:

* Internationalism (politics), a movement to increase cooperation across national borders

* Internationalism, a current within the socialist movement opposed to World War I

* ''Our Favourite Shop

''Our Favourite S ...

of his day, believed that war could be eliminated by stronger international laws and organizations. "I am drawn more to this cause than to any," he wrote in 1907. Carnegie's single largest commitment in this field was his creation of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

On his seventy-fifth birthday, November 25, 1910, Andrew Carnegie announced the establishment of the Endowment with a gift of $10 million worth of first mortgage bonds, paying a 5% rate of interest. The interest income generated from these bonds was to be used to fund a new think tank

A think tank, or policy institute, is a research institute that performs research and advocacy concerning topics such as social policy, political strategy, economics, military, technology, and culture. Most think tanks are non-governmenta ...

dedicated to advancing the cause of world peace. In his deed of gift, presented in Washington on December 14, 1910, Carnegie charged trustees to use the fund to "hasten the abolition of international war, the foulest blot upon our civilization", and he gave his trustees "the widest discretion as to the measures and policy they shall from time to time adopt" in carrying out the purpose of the fund.

Carnegie chose longtime adviser Elihu Root

Elihu Root (; February 15, 1845February 7, 1937) was an American lawyer, Republican politician, and statesman who served as Secretary of State and Secretary of War in the early twentieth century. He also served as United States Senator from N ...

, senator from New York and former Secretary of War and of State, to be the Endowment's first president. Awarded the Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the will of Swedish industrialist, inventor and armaments (military weapons and equipment) manufacturer Alfred Nobel, along with the prizes in Nobel Prize in Chemistry, Chemi ...

in 1912, Root served until 1925. Founder trustees included Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

president Charles William Eliot, philanthropist Robert S. Brookings

Robert Somers Brookings (January 22, 1850 – November 15, 1932) was an American businessman and philanthropist, known for his involvement with Washington University in St. Louis and his founding of the Brookings Institution.

Early life

Robert ...

, former U.S. Ambassador

Ambassadors of the United States are persons nominated by the President of the United States, president to serve as the country's diplomat, diplomatic representatives to foreign nations, international organizations, and as Ambassador-at-large, ...

to Great Britain Joseph Hodges Choate, former secretary of state John W. Foster

John Watson Foster (March 2, 1836 – November 15, 1917) was an American diplomat and military officer, as well as a lawyer and journalist. His highest public office was U.S. Secretary of State under Benjamin Harrison, although he also proved inf ...

, and Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching

The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching (CFAT) is a U.S.-based education policy and research center. It was founded by Andrew Carnegie in 1905 and chartered in 1906 by an act of the United States Congress. Among its most nota ...

president Henry Smith Pritchett.

The first fifty years: 1910–1960

At the outset of America's involvement in

At the outset of America's involvement in World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

in 1917, the Carnegie Endowment trustees unanimously declared, "the most effective means of promoting durable international peace is to prosecute the war against the Imperial Government of Germany to final victory for democracy." In December 1918, Carnegie Endowment Secretary James Brown Scott and four other Endowment personnel, including James T. Shotwell

James Thomson Shotwell

(August 6, 1874 – July 15, 1965) was a Canadian-born American history professor. He played an instrumental role in the creation of the International Labour Organization (ILO) in 1919, as well as for his influence in promo ...

, sailed with President Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

on the USS ''George Washington'' to join the peace talks in France.

Carnegie is often remembered for having built Carnegie libraries, which were a major recipient of his largesse. The libraries were usually funded not by the Endowment but by other Carnegie trusts, operating mainly in the English-speaking world. However, after World War I the Endowment built libraries in Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to th ...

, France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, and Serbia

Serbia (, ; Serbian language, Serbian: , , ), officially the Republic of Serbia (Serbian language, Serbian: , , ), is a landlocked country in Southeast Europe, Southeastern and Central Europe, situated at the crossroads of the Pannonian Bas ...

in three cities which had been badly damaged in the war. In addition, in 1918, the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (CEIP) began to support library special collections on international issues through its International Mind Alcove program, which aimed to foster a more global perspective among the public in the United States and other countries. The Endowment concluded its support for this program in 1958.

On July 14, 1923, the Hague Academy of International Law

The Hague Academy of International Law (french: Académie de droit international de La Haye) is a center for high-level education in both public and private international law housed in the Peace Palace in The Hague, Netherlands. Courses are taugh ...

, an initiative of the Endowment, was formally opened in the Peace Palace at The Hague

The Hague ( ; nl, Den Haag or ) is a city and municipality of the Netherlands, situated on the west coast facing the North Sea. The Hague is the country's administrative centre and its seat of government, and while the official capital of ...

.

The Peace Palace had been built by the Carnegie Foundation (Netherlands)

The Carnegie Foundation ( nl, Carnegie Stichting) is an organization based in The Hague, Netherlands. It was founded in 1903 by Andrew Carnegie in order to manage his donation of US$1.5 million, which was used for the construction, management a ...

in 1913 to house the Permanent Court of Arbitration and a library of international law.

In 1925, Nicholas Murray Butler succeeded Elihu Root

Elihu Root (; February 15, 1845February 7, 1937) was an American lawyer, Republican politician, and statesman who served as Secretary of State and Secretary of War in the early twentieth century. He also served as United States Senator from N ...

as president of the Endowment. In December of the same year, the endowment's Board approved a proposal by President Butler to offer aid in modernizing the Vatican Library

The Vatican Apostolic Library ( la, Bibliotheca Apostolica Vaticana, it, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana), more commonly known as the Vatican Library or informally as the Vat, is the library of the Holy See, located in Vatican City. Formally es ...

. From 1926 to 1939 the Carnegie Endowment expended some $200,000 on the endeavor. For his work, including his involvement with the Kellogg–Briand Pact

The Kellogg–Briand Pact or Pact of Paris – officially the General Treaty for Renunciation of War as an Instrument of National Policy – is a 1928 international agreement on peace in which signatory states promised not to use war to ...

, Butler was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the will of Swedish industrialist, inventor and armaments (military weapons and equipment) manufacturer Alfred Nobel, along with the prizes in Nobel Prize in Chemistry, Chemi ...

in 1931.

In November 1944, the Carnegie Endowment published Raphael Lemkin

Raphael Lemkin ( pl, Rafał Lemkin; 24 June 1900 – 28 August 1959) was a Polish lawyer who is best known for coining the term ''genocide'' and initiating the Genocide Convention, an interest spurred on after learning about the Armenian genocid ...

's ''Axis Rule in Occupied Europe: Laws of Occupation—Analysis of Government—Proposals for Redress''. The work was the first to bring the word ''genocide

Genocide is the intentional destruction of a people—usually defined as an ethnic, national, racial, or religious group—in whole or in part. Raphael Lemkin coined the term in 1944, combining the Greek word (, "race, people") with the Latin ...

'' into the global lexicon. In April 1945, James T. Shotwell

James Thomson Shotwell

(August 6, 1874 – July 15, 1965) was a Canadian-born American history professor. He played an instrumental role in the creation of the International Labour Organization (ILO) in 1919, as well as for his influence in promo ...

, director of the Carnegie Endowment's Division of Economics and History, served as chairman of the semiofficial consultants to the U.S. delegation at the San Francisco conference to draw up the United Nations Charter

The Charter of the United Nations (UN) is the foundational treaty of the UN, an intergovernmental organization. It establishes the purposes, governing structure, and overall framework of the UN system, including its six principal organs: the ...

. As chairman, Shotwell pushed for an amendment to establish a permanent United Nations Commission on Human Rights

The United Nations Commission on Human Rights (UNCHR) was a functional commission within the overall framework of the United Nations from 1946 until it was replaced by the United Nations Human Rights Council in 2006. It was a subsidiary body of t ...

, which exists to this day.

In December 1945, Butler stepped down after twenty years as president and chairman of the board of trustees. Butler was the last living member of the original board selected by Andrew Carnegie in 1910. John Foster Dulles

John Foster Dulles (, ; February 25, 1888 – May 24, 1959) was an American diplomat, lawyer, and Republican Party politician. He served as United States Secretary of State under President Dwight D. Eisenhower from 1953 to 1959 and was briefly ...

was elected to succeed Butler as chairman of the board of trustees, where he served until fellow board member Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; ; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American military officer and statesman who served as the 34th president of the United States from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, ...

was elected president of the U.S. in 1952 and appointed Dulles Secretary of State.

In 1946, Alger Hiss

Alger Hiss (November 11, 1904 – November 15, 1996) was an American government official accused in 1948 of having spied for the Soviet Union in the 1930s. Statutes of limitations had expired for espionage, but he was convicted of perjury in con ...

succeeded Butler as president of the Endowment but resigned in 1949 after being denounced as a communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

and a spy by Whittaker Chambers

Whittaker Chambers (born Jay Vivian Chambers; April 1, 1901 – July 9, 1961) was an American writer-editor, who, after early years as a Communist Party member (1925) and Soviet spy (1932–1938), defected from the Soviet underground (1938), ...

and on December 15, 1948, indicted by the United States Department of Justice

The United States Department of Justice (DOJ), also known as the Justice Department, is a federal executive department of the United States government tasked with the enforcement of federal law and administration of justice in the United State ...

on two counts of perjury. Hiss was replaced in the interim by James T. Shotwell

James Thomson Shotwell

(August 6, 1874 – July 15, 1965) was a Canadian-born American history professor. He played an instrumental role in the creation of the International Labour Organization (ILO) in 1919, as well as for his influence in promo ...

.

In 1947, the Carnegie Endowment's headquarters were moved closer to the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and international security, security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be ...

in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

, while the Washington office at Peter Parker House

The Peter Parker House, also known as the former headquarters of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, is a historic row house at 700 Jackson Place NW in Washington D.C. Built in 1860, it is historically significant for its association ...

(700 Jackson Pl., NW) became a subsidiary branch.

In 1949, the Washington branch was shuttered.

In 1950, the Endowment board of trustees appointed Joseph E. Johnson, a historian and former State Department official, to take the helm.

The Cold War years: 1960–1990

In 1963, the Carnegie Endowment reconstituted its International Law Program in order to address several emerging international issues: the increase in significance and impact of international organizations; the technological revolution that facilitated the production of new military weaponry; the spread of Communism; the surge in newly independent states; and the challenges of new forms of economic activity, including global corporations and intergovernmental associations. The program resulted in the New York-based Study Group on the United Nations and the International Organization Study Group at the European Centre inGeneva

Geneva ( ; french: Genève ) frp, Genèva ; german: link=no, Genf ; it, Ginevra ; rm, Genevra is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland (after Zürich) and the most populous city of Romandy, the French-speaki ...

.

In 1970, Thomas L. Hughes

Thomas Lowe Hughes (December 11, 1925 – January 2, 2023) was an American government official who was the Director of the Bureau of Intelligence and Research during the Kennedy and Johnson administrations. From 1971 he was President of the Carn ...

became the sixth president of the Carnegie Endowment. Hughes moved the Endowment's headquarters from New York to Washington, D.C., and closed the Endowment's European Centre in Geneva.

The Carnegie Endowment acquired full ownership of ''Foreign Policy

A State (polity), state's foreign policy or external policy (as opposed to internal or domestic policy) is its objectives and activities in relation to its interactions with other states, unions, and other political entities, whether bilaterall ...

'' magazine in the spring of 1978. The Endowment published ''Foreign Policy'' for 30 years, moving it from a quarterly academic journal to a bi-monthly glossy covering the nexus of globalization

Globalization, or globalisation (Commonwealth English; see spelling differences), is the process of interaction and integration among people, companies, and governments worldwide. The term ''globalization'' first appeared in the early 20t ...

and international policy. The magazine was sold to ''The Washington Post

''The Washington Post'' (also known as the ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'') is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C. It is the most widely circulated newspaper within the Washington metropolitan area and has a large nati ...

'' in 2008.

In 1981, Carnegie Endowment Associate Fred Bergsten

C. Fred Bergsten (born April 23, 1941) is an American economist, author, think tank entrepreneur, and policy adviser. He has served as assistant for international economic affairs to Henry Kissinger within the National Security Council and as ...

co-founded the Institute for International Economics—today known as the Peterson Institute for International Economics

The Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE), known until 2006 as the Institute for International Economics (IIE), is an American think tank based in Washington, D.C. It was founded by C. Fred Bergsten in 1981 and has been led by ...

.

Citing the growing danger of a nuclear arms race between India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

and Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

, Thomas L. Hughes

Thomas Lowe Hughes (December 11, 1925 – January 2, 2023) was an American government official who was the Director of the Bureau of Intelligence and Research during the Kennedy and Johnson administrations. From 1971 he was President of the Carn ...

formed an eighteen-member Task Force on Non-Proliferation and South Asian Security to propose methods for reducing the growing nuclear tensions on the subcontinent.

In 1989, two former Carnegie associates, Barry Blechman and Michael Krepon, founded the Henry L. Stimson Center

The Stimson Center, named after American statesman, lawyer, and politician Henry L. Stimson, is a nonprofit, nonpartisan think tank that aims to enhance international peace and security through analysis and outreach. The center's stated approach ...

.

After the Cold War: 1990–2000

In 1991, Morton Abramowitz was named the seventh president of the Endowment. Abramowitz, previously a State Department official, focused the Endowment's attention on Russia in the post-Soviet era. In this spirit, the Carnegie Endowment opened theCarnegie Moscow Center

The Carnegie Moscow Center () was a Moscow-based think tank that focuses on domestic and foreign policy. It was established in 1994 as a regional affiliate of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. It was the number one think tank in Ce ...

in 1994 as a home of Russian scholar-commentators.

Jessica Mathews

Jessica Tuchman Mathews (born July 4, 1946) is an American international affairs expert with a focus on climate and energy, defense and security, nuclear weapons, and conflict and governance. She was President of the Carnegie Endowment for Intern ...

joined the Carnegie Endowment as its eighth president in May 1997. Under her leadership, Carnegie's goal was to become the first multinational/global think tank.

In 2000, Mathews announced the creation of the Migration Policy Institute (MPI) headed by Demetrios Papademetriou

Demetrios G. Papademetriou (February 18, 1946 – January 26, 2022) was an American immigration scholar and advisor. He cofounded the Migration Policy Institute in 2001.

References

1946 births

2022 deaths

American academics

Duke Universit ...

which became the first stand-alone think tank concerned with international migration.

The Global Think Tank: 2000–present

As first laid out with the ''Global Vision'' in 2007, the Carnegie Endowment aspired to be the first global think tank. Mathews said that her aim was to make Carnegie the place that brings what the world thinks into thinking about U.S. policy and to communicate that thinking to a global audience. During Mathews' tenure as president, the Carnegie Endowment launched the Carnegie Middle East Center inBeirut

Beirut, french: Beyrouth is the capital and largest city of Lebanon. , Greater Beirut has a population of 2.5 million, which makes it the third-largest city in the Levant region. The city is situated on a peninsula at the midpoint o ...

(2006), Carnegie Europe in Brussels

Brussels (french: Bruxelles or ; nl, Brussel ), officially the Brussels-Capital Region (All text and all but one graphic show the English name as Brussels-Capital Region.) (french: link=no, Région de Bruxelles-Capitale; nl, link=no, Bruss ...

(2007), and the Carnegie-Tsinghua Center at the Tsinghua University

Tsinghua University (; abbreviation, abbr. THU) is a National university, national Public university, public research university in Beijing, China. The university is funded by the Ministry of Education of the People's Republic of China, Minis ...

in Beijing

}

Beijing ( ; ; ), alternatively romanized as Peking ( ), is the capital of the People's Republic of China. It is the center of power and development of the country. Beijing is the world's most populous national capital city, with over 21 ...

(2010). Additionally, in partnership with the al-Farabi Kazakh National University, Carnegie established the Al-Farabi Carnegie Program on Central Asia in Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan, officially the Republic of Kazakhstan, is a transcontinental country located mainly in Central Asia and partly in Eastern Europe. It borders Russia to the north and west, China to the east, Kyrgyzstan to the southeast, Uzbeki ...

in late 2011.

In April 2016, the sixth international Center, Carnegie India, opened in New Delhi

New Delhi (, , ''Naī Dillī'') is the capital of India and a part of the National Capital Territory of Delhi (NCT). New Delhi is the seat of all three branches of the government of India, hosting the Rashtrapati Bhavan, Parliament House ...

.

In February 2015, Mathews stepped down as president of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace after 18 years. William J. Burns

William John Burns (October 19, 1861 – April 14, 1932) was an American private investigator and law enforcement official. He was known as "America's Sherlock Holmes" and earned fame for having conducted private investigations into a number of ...

, former U.S. deputy secretary of state, became Carnegie's ninth president. After Burns' nomination and confirmation as Director of the Central Intelligence Agency, then-California Supreme Court Justice and Stanford professor Mariano-Florentino Cuéllar

Mariano-Florentino "Tino" Cuéllar (born July 27, 1972) is an American scholar, academic leader, public official, jurist, and nonprofit executive currently serving as the 10th president of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. A former ...

became President of the Carnegie Endowment on November 1, 2021.

In April 2022, the Carnegie Endowment was compelled to close its Moscow center at the direction of the Russian government.

Officers

;Presidents *Elihu Root

Elihu Root (; February 15, 1845February 7, 1937) was an American lawyer, Republican politician, and statesman who served as Secretary of State and Secretary of War in the early twentieth century. He also served as United States Senator from N ...

(1912–1925)

* Nicholas Murray Butler (1925–1945)

*Alger Hiss

Alger Hiss (November 11, 1904 – November 15, 1996) was an American government official accused in 1948 of having spied for the Soviet Union in the 1930s. Statutes of limitations had expired for espionage, but he was convicted of perjury in con ...

(1946–1949)

*James T. Shotwell

James Thomson Shotwell

(August 6, 1874 – July 15, 1965) was a Canadian-born American history professor. He played an instrumental role in the creation of the International Labour Organization (ILO) in 1919, as well as for his influence in promo ...

(1949–1950)

* Joseph E. Johnson (1950–1971)

*Thomas L. Hughes

Thomas Lowe Hughes (December 11, 1925 – January 2, 2023) was an American government official who was the Director of the Bureau of Intelligence and Research during the Kennedy and Johnson administrations. From 1971 he was President of the Carn ...

(1971–1991)

*Morton I. Abramowitz

Morton Isaac Abramowitz (born January 20, 1933) is an American diplomat and former U.S. State Department official. Starting his overseas career in Taipei, Taiwan after joining the foreign service, he served as U.S. Ambassador to Thailand and Tur ...

(1991–1997)

*Jessica Mathews

Jessica Tuchman Mathews (born July 4, 1946) is an American international affairs expert with a focus on climate and energy, defense and security, nuclear weapons, and conflict and governance. She was President of the Carnegie Endowment for Intern ...

(1997–2015)

*William J. Burns

William John Burns (October 19, 1861 – April 14, 1932) was an American private investigator and law enforcement official. He was known as "America's Sherlock Holmes" and earned fame for having conducted private investigations into a number of ...

(2015–2021)

*Thomas Carothers

Thomas Carothers (born June 28, 1956) is an American lawyer and an expert on international democracy support, democratization, and U.S. foreign policy. He is senior vice president for studies at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, wher ...

(interim) (2021)

*Mariano-Florentino Cuéllar

Mariano-Florentino "Tino" Cuéllar (born July 27, 1972) is an American scholar, academic leader, public official, jurist, and nonprofit executive currently serving as the 10th president of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. A former ...

(2021–present)

;Chairpersons

*Elihu Root

Elihu Root (; February 15, 1845February 7, 1937) was an American lawyer, Republican politician, and statesman who served as Secretary of State and Secretary of War in the early twentieth century. He also served as United States Senator from N ...

(1910–1925)

* Nicholas Murray Butler (1925–1945)

*John W. Davis

John William Davis (April 13, 1873 – March 24, 1955) was an American politician, diplomat and lawyer. He served under President Woodrow Wilson as the Solicitor General of the United States and the United States Ambassador to the United Kingdom ...

(1946–1947)

*John Foster Dulles

John Foster Dulles (, ; February 25, 1888 – May 24, 1959) was an American diplomat, lawyer, and Republican Party politician. He served as United States Secretary of State under President Dwight D. Eisenhower from 1953 to 1959 and was briefly ...

(1947–1953)

*Harvey Hollister Bundy

Harvey Hollister Bundy Sr. (March 30, 1888 – October 7, 1963) was an American attorney who served as a special assistant to the Secretary of War during World War II. He was the father of William Bundy and McGeorge Bundy, who both served at high ...

(1953–1958)

*Whitney North Seymour

Whitney North Seymour Sr. (January 4, 1901 – May 21, 1983) was an American attorney who worked primarily as a trial lawyer. He served as assistant solicitor general during the presidency of Herbert Hoover. In 1960, he was elected the 84th pre ...

(1958–1970)

*Seymour Milton Katz

Seymour may refer to:

Places Australia

*Seymour, Victoria, a township

*Electoral district of Seymour, a former electoral district in Victoria

*Rural City of Seymour, a former local government area in Victoria

*Seymour, Tasmania, a locality

...

(1970–1978)

* John W. Douglas (1978–1986)

*Charles Zwick

Charles John Zwick (July 17, 1926 – April 20, 2018) was an American civil servant who served as director of the United States' Office of Management and Budget from January 29, 1968, until January 21, 1969, under the administration of Lyndon B. J ...

(1986–1993)

* Robert Carswell (1993–1999)

*William H. Donaldson

William Henry Donaldson (born June 2, 1931) was the 27th Chairman of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), serving from February 2003 to June 2005. He served as Under Secretary of State for International Security Affairs in the Nix ...

(1999–2003)

*James C. Gaither

James is a common English language surname and given name:

*James (name), the typically masculine first name James

* James (surname), various people with the last name James

James or James City may also refer to:

People

* King James (disambiguat ...

(2003–2009)

*Richard Giordano

Richard is a male given name. It originates, via Old French, from Old Frankish and is a compound of the words descending from Proto-Germanic ''*rīk-'' 'ruler, leader, king' and ''*hardu-'' 'strong, brave, hardy', and it therefore means 'stron ...

(2009–2013)

*Harvey V. Fineberg

Harvey Vernon Fineberg (born September 15, 1945) is an American physician. A noted researcher in the fields of health policy and medical decision making, his past research has focused on the process of policy development and implementation, assess ...

(2013–2018)

*Penny Pritzker

Penny Sue Pritzker (born May 2, 1959) is an American billionaire businesswoman and civic leader who served as the 38th United States secretary of commerce in the Obama administration from 2013 to 2017. She was confirmed by a Senate vote of 97� ...

(2018–present)

Board of Trustees

*Penny Pritzker

Penny Sue Pritzker (born May 2, 1959) is an American billionaire businesswoman and civic leader who served as the 38th United States secretary of commerce in the Obama administration from 2013 to 2017. She was confirmed by a Senate vote of 97� ...

, Chair. Chairman of PSP Partners and Pritzker Realty Group; Chairman Inspired Capital Partners; Former U.S. Secretary of Commerce

The United States secretary of commerce (SecCom) is the head of the United States Department of Commerce. The secretary serves as the principal advisor to the president of the United States on all matters relating to commerce. The secretary rep ...

.

* Steven A. Denning, Vice Chair. Chairman Emeritus, General Atlantic.

* Ayman Asfari

Ayman Asfari (born 8 July 1958) is a Syrian-born British businessman. He was the chief executive (CEO) of Petrofac, a Jersey-registered multinational oilfield services company serving the oil, gas and energy production and processing industries, ...

, Executive Chairman, Venterra Group; Co-founder, The Asfari Foundation.

* Jim Balsillie

James Laurence Balsillie (born February 3, 1961) is a Canadian businessman and philanthropist. He is the former Chair and co-CEO of the Canadian technology company Research In Motion (Blackberry), which at its prime made over $20B in sales annua ...

, Founder and Chair, Centre for International Governance Innovation; Co-founder, Institute for New Economic Thinking.

* C. K. Birla

Chandra Kant Birla is an Indian industrialist and philanthropist. He is chairman of the CK Birla Group, a conglomerate operating across home and building products, automotive and technology, and healthcare and education.

Career

In addition to ...

, Chairman, CK Birla Group.

* Bill Bradley

William Warren Bradley (born July 28, 1943) is an American politician and former professional basketball player. He served three terms as a Democratic U.S. senator from New Jersey (1979–1997). He ran for the Democratic Party's nomination f ...

, Managing director, Allen & Company

Allen & Company LLC is an American privately held boutique investment bank based at 711 Fifth Avenue, New York. The firm specializes in real estate, technology, media and entertainment.

History

Founded in 1922 by Charles Robert Allen, Jr., he w ...

.

* David Burke, Co-founder, CEO, and managing director, Makena Capital Management.

* Mariano-Florentino “Tino” Cuéllar, President, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

* Henri de Castries

Henri de La Croix de Castries (born 15 August 1954) is a French businessman. He was chairman and CEO of AXA until retiring from both roles on 1 September 2016.

Early life

Henri de La Croix de Castries was born on August 15, 1954 in Bayonne. His fa ...

, Chairman, Institut Montaigne

Institut Montaigne is a think tank based in Paris, France, founded in 2000. Institut Montaigne's makes public policy recommendations to advance its agenda, which broadly reflects that of the large French companies that fund it. It contracts expert ...

; Chairman, Europe General Atlantic; Vice Chairman, Nestlé

Nestlé S.A. (; ; ) is a Switzerland, Swiss multinational food and drink processing conglomerate corporation headquartered in Vevey, Vaud, Switzerland. It is the largest publicly held food company in the world, measured by revenue and other me ...

.

* Eileen Donahoe, Executive Director, Global Digital Policy Incubator, Stanford University

Stanford University, officially Leland Stanford Junior University, is a private research university in Stanford, California. The campus occupies , among the largest in the United States, and enrolls over 17,000 students. Stanford is consider ...

.

* Anne Finucane

Anne Finucane (born 1952) is an American banker who is vice chair of Bank of America and chair of the board of Bank of America Europe. She leads the bank's socially responsible investing, global public policy, and environmental, social and corpor ...

, Chairman of the Board, Bank of America

The Bank of America Corporation (often abbreviated BofA or BoA) is an American multinational investment bank and financial services holding company headquartered at the Bank of America Corporate Center in Charlotte, North Carolina. The bank w ...

Europe.

* Patricia House, Vice Chairman of the Board, C3.ai.

* Maha Ibrahim, General Partners, Canaan Partners.

* Walter B. Kielholz, Honorary Chairman, Swiss Re Ltd.

* Boon Hwee Koh, Chairman, Altara Ventures Pte Ltd.

* Susan Liautaud, Susan Liautaud & Associates Ltd.

* Scott D. Malkin

Scott David Malkin (born 1959) is the founder of Value Retail PlcAdebayo Ogunlesi

Adebayo "Bayo" O. Ogunlesi CON (born December 20, 1953) is a Nigerian lawyer and investment banker.

He is currently Chairman and Managing Partner at the private equity firm Global Infrastructure Partners (GIP).

Ogunlesi was the former head of G ...

, Chairman and Managing Partner, Global Infrastructure Partners

Global Infrastructure Partners (GIP) is an infrastructure investment fund making equity and selected debt investments. GIP's main headquarters are located in New York City and its equity investments are based on infrastructure assets in the energ ...

.

* Kenneth E. Olivier, Past Chairman and CEO, Dodge & Cox.

* Jonathan Oppenheimer

Jonathan M. E. Oppenheimer (born 18 November 1969) is a South African billionaire businessman and conservationist, and the Executive Chairman of Oppenheimer Generations, a former executive of De Beers and a former vice-president of his family's ...

, Director, Oppenheimer Generations.

* Catherine James Paglia, Director, Enterprise Asset Management Enterprise asset management (EAM) involves the management of the maintenance of physical assets of an organization throughout each asset's lifecycle. EAM is used to plan, optimize, execute, and track the needed maintenance activities with the associ ...

.

* Deven J. Parekh, Managing Director, Insight Partners

Insight Partners (previously Insight Venture Partners) is an American venture capital and private equity firm based in New York City. The firm invests in growth-stage technology, software and Internet businesses.

History

Insight Partners was fo ...

.

* Victoria Ransom

Victoria Ransom is a serial entrepreneur from New Zealand. She has developed three companies including Wildfire Interactive, a social marketing SaaS company, where Ransom was chief executive officer until it was sold to Google in 2012. Ransom c ...

, Founder & CEO, Prisma; Former CEO, Wildfire & Director of Product, Google

Google LLC () is an American multinational technology company focusing on search engine technology, online advertising, cloud computing, computer software, quantum computing, e-commerce, artificial intelligence, and consumer electronics. ...

.

* L. Rafael Reif, President, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is a private land-grant research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Established in 1861, MIT has played a key role in the development of modern technology and science, and is one of the ...

* George Siguler, Founding Partner and Managing Director, Siguler Guff and Company.

* Ratan Tata

Ratan Naval Tata, GBE (born 28 December 1937) is an Indian industrialist and former chairman of Tata Sons. He was also the chairman of the Tata Group from 1990 to 2012, serving also as interim chairman from October 2016 through February 2017. ...

, Chairman, Tata Trust.

* Rohan S. Weerasinghe, General Counsel, Citigroup Inc

Citigroup Inc. or Citi (stylized as citi) is an American multinational investment bank and financial services corporation headquartered in New York City. The company was formed by the merger of banking giant Citicorp and financial conglomerate ...

.

* Yichen Zhang, Chairman and CEO, CITIC Capital Holdings Ltd.

* Robert Zoellick, Senior Counselor, Brunswick Group.

Carnegie Global Centers

Carnegie Endowment Headquarters in Washington, D.C.

The Carnegie Endowment office inWashington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

, is home to ten programs: Africa; American Statecraft; Asia; Democracy, Conflict, and Governance; Europe; Middle East; Nuclear Policy; Russia and Eurasia; South Asia; and Technology and International Affairs.

Carnegie Moscow Center

In 1993, the Endowment launched theCarnegie Moscow Center

The Carnegie Moscow Center () was a Moscow-based think tank that focuses on domestic and foreign policy. It was established in 1994 as a regional affiliate of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. It was the number one think tank in Ce ...

, with the belief that "in today's world a think tank whose mission is to contribute to global security, stability, and prosperity requires a permanent presence and a multinational outlook at the core of its operations."

The center's stated goals were to embody and promote the concepts of disinterested social science research and the dissemination of its results in post-Soviet Russia and Eurasia; to provide a free and open forum for the discussion and debate of critical national, regional and global issues; and to further cooperation and strengthen relations between Russia and the United States by explaining the interests, objectives and policies of each. From 2006 until December 2008, the center was led by former Deputy Secretary General of NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two No ...

, Rose Gottemoeller

Rose Eilene Gottemoeller (born March 24, 1953) is an American diplomat who served as Deputy Secretary General of NATO from October 2016 to October 2019 under Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg. She previously served as Under Secretary of State for ...

. The center was headed by Dmitri Trenin

Dmitri Vitalyevich Trenin () is a member of . He was the director of the Carnegie Moscow Center, a Russian think tank. A former colonel of Russian military intelligence, Trenin served for 21 years in the Soviet Army and Russian Ground Forces, be ...

until its closing in April 2022.

Carnegie Middle East Center

The Carnegie Middle East Center was established in Beirut, Lebanon in November 2006. The center aims to better inform the process of political change in the Arab Middle East and deepen understanding of the complex economic and security issues that affect it. , the current director of the center is Maha Yahya.Carnegie Europe

Founded in 2007 byFabrice Pothier

Fabrice Pothier (born 24 August 1975) is a French political expert and CEO of political consultancy, Rasmussen Global. He was part of Emmanuel Macron's La République En Marche and was a former NATO director of policy planning and founding directo ...

, Carnegie Europe is the European centre of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. From its newly expanded presence in Brussels, Carnegie Europe combines the work of its research platform with the fresh perspectives of Carnegie's centres in Washington, Moscow, Beijing, and Beirut, bringing a unique global vision to the European policy community. Through publications, articles, seminars, and private consultations, Carnegie Europe aims to foster new thinking on the daunting international challenges shaping Europe's role in the world.

Carnegie Europe is currently directed by Rosa Balfour.

Carnegie-Tsinghua Center for Global Policy

The Carnegie-Tsinghua Center for Global Policy was established atTsinghua University

Tsinghua University (; abbreviation, abbr. THU) is a National university, national Public university, public research university in Beijing, China. The university is funded by the Ministry of Education of the People's Republic of China, Minis ...

in Beijing

}

Beijing ( ; ; ), alternatively romanized as Peking ( ), is the capital of the People's Republic of China. It is the center of power and development of the country. Beijing is the world's most populous national capital city, with over 21 ...

in 2010. The center's focuses include China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

's foreign relations; international economics and trade; climate change and energy

In the 21st century, the earth's climate and its energy policy interact and their relationship is studied and governed by a variety of national and international institutions.

The relationships between energy-resource depletion, climate change, ...

; nonproliferation and arms control; and other global and regional security issues such as North Korea

North Korea, officially the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the northern half of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and shares borders with China and Russia to the north, at the Yalu River, Y ...

, Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is bordere ...

, Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

, and Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

.

The current director of the center is Paul Haenle

Paul Thomas Haenle (born ) is an American political adviser, and an international relations professor and consultant.

Career

Paul Haenle holds the Maurice R. Greenberg Director’s Chair at the Carnegie-Tsinghua Center for Global Policy (CTC) in ...

.

Carnegie India

In April 2016, Carnegie India opened inNew Delhi

New Delhi (, , ''Naī Dillī'') is the capital of India and a part of the National Capital Territory of Delhi (NCT). New Delhi is the seat of all three branches of the government of India, hosting the Rashtrapati Bhavan, Parliament House ...

, India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

. The center's focuses include the political economy of reform in India, foreign and security policy, and the role of innovation and technology in India's internal transformation and international relations.

The current director of the center is Rudra Chaudhuri.

See also

* ''International Economics Bulletin The ''International Economics Bulletin'' is a bi-monthly publication published by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Edited by Uri Dadush, the publication draws on the expertise of Carnegie's global centers to provide a view of the ec ...

''

* List of peace activists

This list of peace activists includes people who have proactively advocated diplomatic, philosophical, and non-military resolution of major territorial or ideological disputes through nonviolent means and methods. Peace activists usually work ...

References

Sources

* Patterson, David S. "Andrew Carnegie's quest for world peace." ''Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society'' 114.5 (1970): 371–383Online

External links

* * Publications *''Foreign Policy''

*

''Pro et Contra''

{{DEFAULTSORT:Carnegie Endowment For International Peace Andrew Carnegie Dupont Circle Peace organizations based in the United States Foreign policy and strategy think tanks in the United States Political and economic think tanks in the United States Embassy Row 1910 establishments in the United States