The Bread-Winners on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''The Bread-Winners: A Social Study'' is an 1883 novel by

In March 1883, the Century Company circulated a

In March 1883, the Century Company circulated a  On October 23, 1883, an interview with Hay, who had just returned from a trip to Colorado, appeared in the pages of the ''Cleveland Leader''. Hay said such a novel would be beyond his powers, and that inaccuracies in the depiction of the local scene suggested to him that it was not written by a Clevelander. He offered no candidates who might have written it. Nevertheless, in November, the ''Leader'' ran a column speculating that Hay was the author, based on phrases used both in ''The Bread-Winners'' and in Hay's earlier book, ''Castilian Days'', and by the fact that one character in the novel was from

On October 23, 1883, an interview with Hay, who had just returned from a trip to Colorado, appeared in the pages of the ''Cleveland Leader''. Hay said such a novel would be beyond his powers, and that inaccuracies in the depiction of the local scene suggested to him that it was not written by a Clevelander. He offered no candidates who might have written it. Nevertheless, in November, the ''Leader'' ran a column speculating that Hay was the author, based on phrases used both in ''The Bread-Winners'' and in Hay's earlier book, ''Castilian Days'', and by the fact that one character in the novel was from

The most successful response was '' The Money-Makers'' (1885), published anonymously by

The most successful response was '' The Money-Makers'' (1885), published anonymously by

Full text

at the

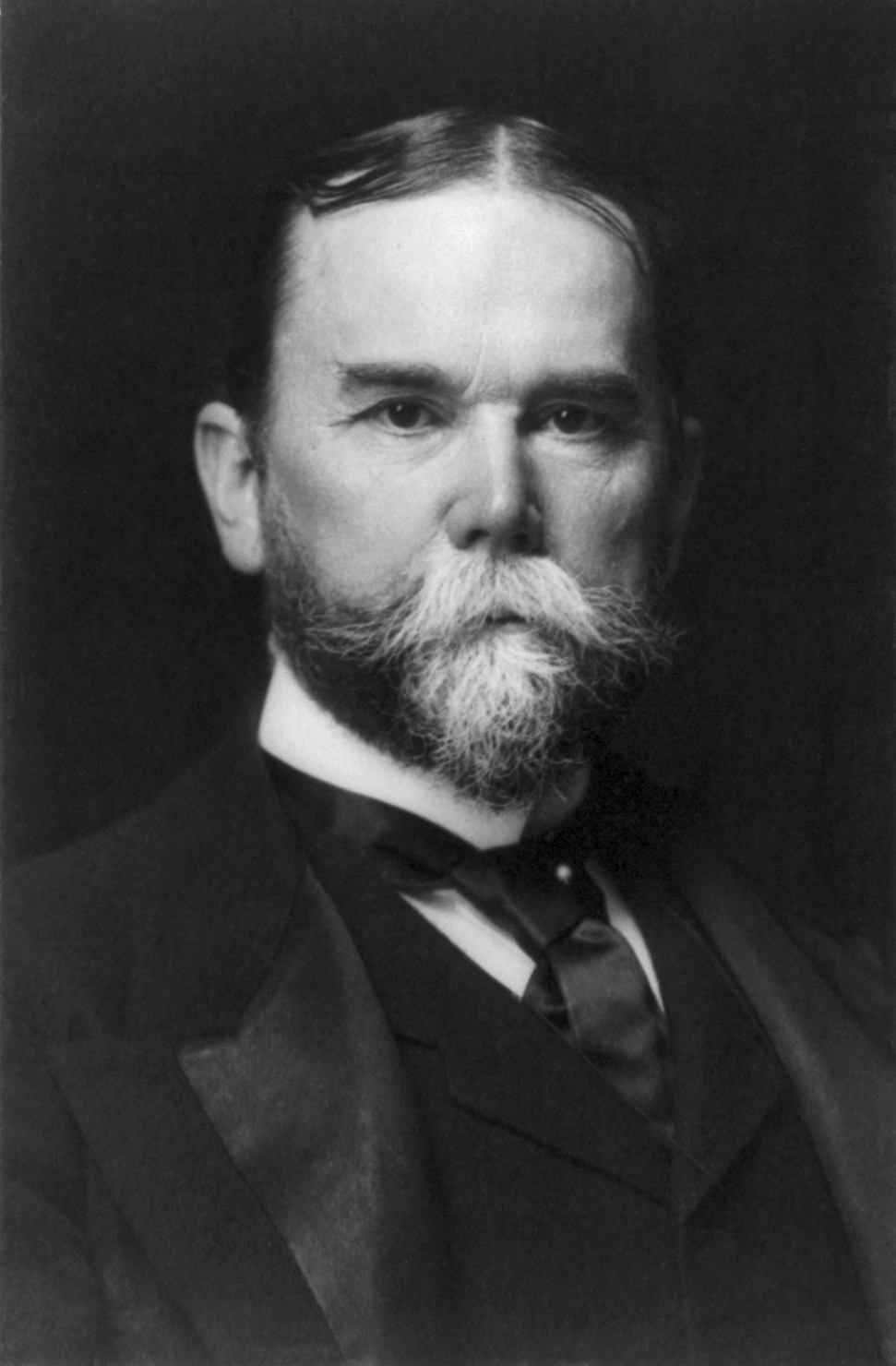

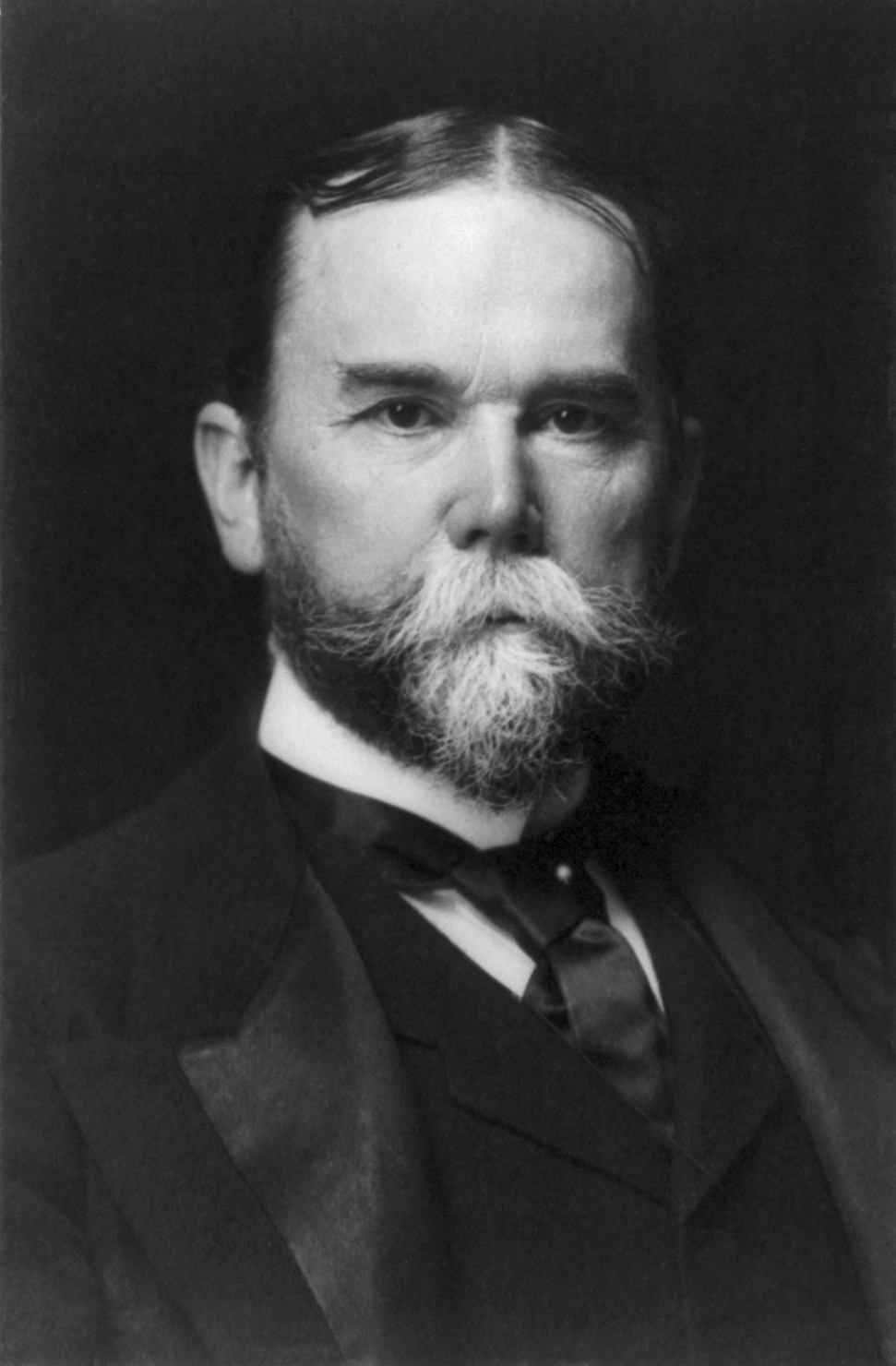

John Hay

John Milton Hay (October 8, 1838July 1, 1905) was an American statesman and official whose career in government stretched over almost half a century. Beginning as a private secretary and assistant to Abraham Lincoln, Hay's highest office was Un ...

, former secretary

A secretary, administrative professional, administrative assistant, executive assistant, administrative officer, administrative support specialist, clerk, military assistant, management assistant, office secretary, or personal assistant is a w ...

to Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

who in 1898 became U.S. Secretary of State

The United States secretary of state is a member of the executive branch of the federal government of the United States and the head of the U.S. Department of State. The office holder is one of the highest ranking members of the president's Ca ...

. The book takes an anti-organized labor

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment", ch. I such as attaining better wages and Employee ben ...

stance, and when published anonymously sold well and provoked considerable public interest in determining who the author was.

The plot of the book revolves around former army captain Arthur Farnham, a wealthy resident of Buffland (an analog of Cleveland

Cleveland ( ), officially the City of Cleveland, is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County. Located in the northeastern part of the state, it is situated along the southern shore of Lake Erie, across the U.S. ...

). He organizes Civil War veterans to keep the peace when the Bread-winners, a group of lazy and malcontented workers, call a violent general strike

A general strike refers to a strike action in which participants cease all economic activity, such as working, to strengthen the bargaining position of a trade union or achieve a common social or political goal. They are organised by large co ...

. He is sought in marriage by the ambitious Maud Matchin, daughter of a carpenter, but instead weds a woman of his own class.

Hay wrote his only novel as a reaction to several strikes that affected him and his business interests in the 1870s and early 1880s. Originally published in installments in ''The Century Magazine

''The Century Magazine'' was an illustrated monthly magazine first published in the United States in 1881 by The Century Company of New York City, which had been bought in that year by Roswell Smith and renamed by him after the Century Associatio ...

'', the book attracted wide interest. Hay had left hints to his identity in the novel, and some guessed right, but he never acknowledged the book as his, and it did not appear with his name on it until after his death in 1905. Hay's hostile view of organized labor was soon seen as outdated, and the book is best remembered for its onetime popularity and controversial nature.

Plot

One of the wealthiest and most cultured residents of the famed Algonquin Avenue in Buffland (a city intended to beCleveland

Cleveland ( ), officially the City of Cleveland, is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County. Located in the northeastern part of the state, it is situated along the southern shore of Lake Erie, across the U.S. ...

), Captain Arthur Farnham is a Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

veteran and widower—his wife died of illness while accompanying him at a remote frontier post. Since he left the army, he has sought to involve himself in municipal affairs but fails through political naiveté. The victorious party has allowed him the position of chairman of the library board. In that capacity, he is approached by Maud Matchin, daughter of carpenter Saul Matchin, a man content with his lot. His daughter is not and seeks employment at the library as a means of bettering herself. Farnham agrees to put her case, but is defeated by a majority on the board, who have their own candidate. She finds herself attracted to Farnham, who is more interested in Alice Belding, daughter of his wealthy widow neighbor.

Saul Matchin had hoped his daughter would become a house servant, but having attended high school, she feels herself too good for that. She is admired by Saul's assistant Sam Sleeny, who lives with the Matchins, a match favored by her father. Sleeny is busy repairing Farnham's outbuildings, and is made jealous by interactions between the captain and Maud. Seeing Sleeny's discontent, Andrew Jackson Offitt (true name Ananias), a locksmith and "professional reformer", tries to get him to join the Bread-winners, a labor organization

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment", ch. I such as attaining better wages and benefits ( ...

. Sleeny is happy with his employment, "Old Saul Matchin and me come to an agreement about time and pay, and both of us was suited. Ef he's got his heel into me, I don't feel it," but due to his unhappiness over Maud, is easy game for Offitt, who gets him to join, and to pay the dues that are Offitt's visible means of support.

Maud has become convinced she is in love with Farnham, and declares it to him. It is not reciprocated, and the scene is witnessed both by Mrs. Belding and by Sleeny. The widow believes Farnham when he states he had given Maud no encouragement, but her daughter, when her mother incautiously tells her of the incident, does not. When Farnham seeks to marry Alice, she turns him down and asks him never to renew the subject.

Offitt's membership has tired of endless talk and plans a general strike

A general strike refers to a strike action in which participants cease all economic activity, such as working, to strengthen the bargaining position of a trade union or achieve a common social or political goal. They are organised by large co ...

, a fact of which Farnham is informed by Mr. Temple, a salty-talking vice president of a rolling mill. An element among the strikers also plans to loot houses along Algonquin Avenue, including Farnham's. The strike begins, paralyzing Buffland's commerce, though it is initially nonviolent. Neither the mayor nor the chief of police, when approached by Farnham, are willing to guard Algonquin Avenue. Farnham proceeds to organize Civil War veterans, and purchases weapons to arm them. After Farnham's force rescues the mayor from being attacked, he deputizes them as special police—on condition there is no expense to the city.

Meanwhile, Maud tells her father she will never marry Sleeny. She is wooed by Bott, who is a spiritualist and a Bread-winner, and also by Offitt. Neither meets success, though Offitt dexterously prevents her from actually saying no, and through flattery and stories of his alleged past piques her interest.

By the end of the second day of the strike, which has spread to Buffland's rival city of Clearfield n the serialization, "Clevealo" the mood among the laborers has turned ugly. Temple warns that the attacks on Algonquin Avenue are imminent, and aids Farnham's force in turning back assaults on the captain's house and on the Belding residence. Bott and Sleeny are captured by the force; the former is sent to prison but Farnham has pity on Sleeny as a good workman, and the carpenter serves only a few days. The settlement of the strike in Clearfield takes the wind out of the Buffland action, and soon most are back at work, though some agitators are dismissed.

Offitt, despite being one of the leaders of the assault on the Belding house, has escaped blame and befriends the sullen Sleeny on his release. Upon learning that some workers pay their landlord, Farnham, in the evening of the rent day at his home, Offitt comes up with a scheme—rob and murder Farnham and let Sleeny take the blame as Offitt elopes with Maud. Accordingly, Offitt sneaks into Farnham's house with Sleeny's hammer, but just as he is striking the fatal blow, Alice Belding, who can see what is going on from her house through an opera glass, screams, distracting Offitt enough so that Farnham is hurt by the blow, but not killed. Offitt hurries away with the money and proceeds to frame Sleeny. After realizing Offitt's treachery, Sleeny escapes jail and kills him. The stolen money is found on Offitt's body, clearing Sleeny in the assault on Farnham, but the carpenter must still stand trial for the killing of Offitt, in which he is aided by partisan testimony from Maud. A sympathetic jury ignores the law to acquit him. Sleeny wins Maud's hand in marriage, and Farnham and Alice Belding are to be wed.

Background

John Hay

John Hay

John Milton Hay (October 8, 1838July 1, 1905) was an American statesman and official whose career in government stretched over almost half a century. Beginning as a private secretary and assistant to Abraham Lincoln, Hay's highest office was Un ...

was born in Indiana in 1838, and grew up in frontier Illinois. During his apprenticeship to become a lawyer in his uncle's office in Springfield

Springfield may refer to:

* Springfield (toponym), the place name in general

Places and locations Australia

* Springfield, New South Wales (Central Coast)

* Springfield, New South Wales (Snowy Monaro Regional Council)

* Springfield, Queenslan ...

, he came to know Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

, and worked for his presidential campaign in 1860. He was made Lincoln's assistant personal secretary

''Personal Secretary'' is a 1938 American comedy film directed by Otis Garrett and written by Betty Laidlaw, Robert Lively and Charles Grayson. The film stars William Gargan, Joy Hodges, Andy Devine, Ruth Donnelly, Samuel S. Hinds and Frances ...

, and spent the years of the American Civil War working for him; the two men forged a close relationship.

After the war, Hay worked for several years in diplomatic posts abroad, then in 1870 became a writer for Horace Greeley

Horace Greeley (February 3, 1811 – November 29, 1872) was an American newspaper editor and publisher who was the founder and newspaper editor, editor of the ''New-York Tribune''. Long active in politics, he served briefly as a congressm ...

's ''New-York Tribune

The ''New-York Tribune'' was an American newspaper founded in 1841 by editor Horace Greeley. It bore the moniker ''New-York Daily Tribune'' from 1842 to 1866 before returning to its original name. From the 1840s through the 1860s it was the domi ...

'', continuing there under Whitelaw Reid

Whitelaw Reid (October 27, 1837 – December 15, 1912) was an American politician and newspaper editor, as well as the author of ''Ohio in the War'', a popular work of history.

After assisting Horace Greeley as editor of the ''New-York Tribu ...

after Greeley's death in 1872. Hay was a gifted writer for the ''Tribune'', but also achieved success with literary works. In 1871, he published ''Pike County Ballads

''Pike County Ballads'' is an 1871 book by John Hay. The collection of post Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the c ...

'', a group of poems written in the dialect of frontier Pike County, Illinois

Pike County is a county in the U.S. state of Illinois. According to the 2010 United States Census, it had a population of 16,430. Its county seat is Pittsfield.

History

Pike County was formed in January 1821 out of Madison County. It was named ...

, where Hay had attended school. The same year, he published ''Castilian Days'', a collection of essays on Spain, some of which had been written while Hay was posted as a diplomat in Madrid.

In 1873, Hay began to woo Clara Stone, daughter of wealthy Cleveland industrialist Amasa Stone

Amasa Stone, Jr. (April 27, 1818 – May 11, 1883) was an American industrialist who is best remembered for having created a regional railroad empire centered in the U.S. state of Ohio from 1860 to 1883. He gained fame in New England in the 1840 ...

, and wed her in 1874.

The marriage made Hay wealthy. Hay and his wife moved to Cleveland, where Hay managed Amasa Stone's investments. In December 1876, a train of Stone's Lake Shore Railway was crossing a bridge when the structure collapsed. The Ashtabula River Railroad Disaster

The Ashtabula River railroad disaster (also called the Ashtabula horror, the Ashtabula Bridge disaster, and the Ashtabula train disaster) was the failure of a bridge over the Ashtabula River near the town of Ashtabula, Ohio, in the United Stat ...

, including the subsequent fire, killed 92 people, the worst rail disaster in American history to that point. Stone held the patent for the design of the bridge and was widely blamed; he left Hay in charge of his businesses in mid-1877 as he went to travel in Europe.

Hay biographer Robert Gale recorded that between the publication of the last of Hay's short fiction in 1871 and that of his only novel in 1883, "Hay married money, entered into a lucrative business arrangement in Cleveland with his conservative father-in-law ndjoined the right wing of the Ohio Republican Party ... ''The Bread-Winners'' was written by a person made essentially different as a result of these experiences."

Postwar labor troubles and literary reaction

Although the American Civil War did not itself transform the United States from a largely agrarian to an urban society, it gave great impetus to a change already under way, especially in the North. The challenges of feeding, clothing, and equipping theUnion Army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also known as the Federal Army and the Northern Army, referring to the United States Army, was the land force that fought to preserve the Union (American Civil War), Union of the collective U.S. st ...

caused the building or expansion of many factories and other establishments. This made many wealthy, and led to an industrialized America.

This transformation did not stop when the war ended; industrial production in the United States increased by 75% from 1865 to 1873, making the U.S. second only to Britain in manufacturing output. Railroad construction made practical the exploitation of the trans-Mississippi West. Although the railroads helped fuel an economic boom, they proved a two-edged sword in the 1870s. The 1872 Crédit Mobilier scandal

The Crédit Mobilier scandal () was a two-part fraud conducted from 1864 to 1867 by the Union Pacific Railroad and the Crédit Mobilier of America construction company in the building of the eastern portion of the First transcontinental railroad. ...

, over graft in the construction of the First transcontinental railroad

North America's first transcontinental railroad (known originally as the "Pacific Railroad" and later as the " Overland Route") was a continuous railroad line constructed between 1863 and 1869 that connected the existing eastern U.S. rail netwo ...

, shook the Grant administration

The presidency of Ulysses S. Grant began on March 4, 1869, when Ulysses S. Grant was inaugurated as the 18th president of the United States, and ended on March 4, 1877. The Reconstruction era took place during Grant's two terms of office. The Ku ...

to its highest levels. Railroad bankruptcies in the Panic of 1873

The Panic of 1873 was a financial crisis that triggered an economic depression in Europe and North America that lasted from 1873 to 1877 or 1879 in France and in Britain. In Britain, the Panic started two decades of stagnation known as the "Lon ...

led to loss of jobs, wage cuts, and business failures. These disturbances culminated in the Railroad Strikes of 1877, when workers struck over cut wages and loss of jobs. The action originally started on the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad

The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was the first common carrier railroad and the oldest railroad in the United States, with its first section opening in 1830. Merchants from Baltimore, which had benefited to some extent from the construction of ...

, but spread to other lines, including the Lake Shore, much to Hay's outrage. Federal troops were sent by President Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes (; October 4, 1822 – January 17, 1893) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 19th president of the United States from 1877 to 1881, after serving in the U.S. House of Representatives and as governor ...

to quash the strikes, at the cost of more than a hundred civilian lives. The Lake Shore dispute, unlike those elsewhere, was settled without violence. Hay remained angry, and blamed foreign agitators for the dispute. He condemned the "unarmed rebellion of foreign workingmen, mostly Irish" and informed Stone by letter, "the very devil seems to have entered into the lower classes of working men and there are plenty of scoundrels to encourage them to all lengths."

Public opinion was generally against the strikes in the 1877 disputes and called for them to be ended by force to preserve property and stability. The strike and its suppression featured in many books of the period, such as Thomas Stewart Denison

Thomas may refer to:

People

* List of people with given name Thomas

* Thomas (name)

* Thomas (surname)

* Saint Thomas (disambiguation)

* Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) Italian Dominican friar, philosopher, and Doctor of the Church

* Thomas the A ...

's ''An Iron Crown: A Tale of the Great Republic'' (1885), with novelists often sympathizing with the demands of the strikers, though decrying their violence. Another labor dispute that likely affected Hay's writing of ''The Bread-Winners'' was the Cleveland Rolling Mill The Cleveland Rolling Mill Company was a rolling steel mill in Cleveland, Ohio. It existed as an independent entity from 1863 to 1899.

Origins

The company stemmed from developments initiated in 1857, when John and David I. Jones, along with Henr ...

strike of June 1882, which occurred just before Hay first submitted his manuscript. During the dispute, union members violently attempted to prevent strikebreaker

A strikebreaker (sometimes called a scab, blackleg, or knobstick) is a person who works despite a strike. Strikebreakers are usually individuals who were not employed by the company before the trade union dispute but hired after or during the st ...

s from entering the mills. A third strike that may have affected the final form of ''The Bread-Winners'' was that against Western Union

The Western Union Company is an American multinational financial services company, headquartered in Denver, Colorado.

Founded in 1851 as the New York and Mississippi Valley Printing Telegraph Company in Rochester, New York, the company chang ...

in 1883—Hay was then a director of that corporation.

Gale noted that ''The Bread-Winners'' has sometimes been characterized as the first anti-labor

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment", ch. I such as attaining better wages and benefits ...

novel, but it was preceded by Thomas Bailey Aldrich

Thomas Bailey Aldrich (; November 11, 1836 – March 19, 1907) was an American writer, poet, critic, and editor. He is notable for his long editorship of ''The Atlantic, The Atlantic Monthly'', during which he published writers including Charles ...

's ''The Stillwater Tragedy'' (1880). Aldrich had little knowledge of workers, and his book was not successful. Nevertheless, ''The Stillwater Tragedy'' was one of a very few novels to deal with labor unions at all, prior to Hay's book.

Themes

Scott Dalrymple, in his journal article on ''The Bread-Winners'', argues, "the brunt of Hay's ire seems aimed less toward these working men themselves than toward troublesome union organizers. Left to their own devices, Hay believes, most laborers are reasonable creatures." Hay biographers Howard L. Kushner and Anne H. Sherrill agree, writing that the author was attempting "to expose the way in which this class, due to its ignorance, fell prey to the villainies of false social reformers". To Hay, unions were dangerous as they manipulate the uneducated worker; it was better for laborers to work out their pay and conditions individually with their employer, as Sleeny does with Matchin. In his journal article, Frederic Jaher notes that Offitt, a self-described reformer, "is arrogant, tyrannical and self-righteous. Hay's message is clear: the established system needs no basic change; eliminate the agitator and harmony returns." Offitt, at birth, was given the forenames Andrew Jackson, which according to Hay shows that the bearer "is the son of illiterate parents, with no family pride or affections, but filled with a bitter and savage partisanship which found its expression in a servile worship of the most injurious personality in American history". Hay despised President Jackson andJacksonian democracy

Jacksonian democracy was a 19th-century political philosophy in the United States that expanded suffrage to most white men over the age of 21, and restructured a number of federal institutions. Originating with the seventh U.S. president, And ...

, which he deemed corrupt and responsible for continuation of the slave system which Hay saw overthrown at huge cost in the American Civil War. He feared a return to values he deemed anticapitalist, and made the Bread-winners "the laziest and most incapable workmen in town", whose ideals are pre-industrialist and foreign in origin. Hay saw no excuse for violence; as the will of the people could be expressed through the ballot, the remedy for any grievances was the next election. According to Gale, Hay "never loses an opportunity to demean the Irish"—they are depicted as talkative and easily led (Offitt writes for the ''Irish Harp''), and the reader is told that "there was not an Irish laborer in the city but knew his way to his ward

Ward may refer to:

Division or unit

* Hospital ward, a hospital division, floor, or room set aside for a particular class or group of patients, for example the psychiatric ward

* Prison ward, a division of a penal institution such as a pris ...

club as well as to mass."

Jaher noted that Hay's view of what a worker should be is summed up in the character of Saul Matchin. Although a successful craftsman, he remains within the working class, not seeking to rise above his station, and is content with his lot. His children are not willing to remain within that class, however: the sons run away and the daughters seek to marry well, symbolizing the change being wrought by industrialization. Robert Dunne points out that the working classes are not depicted favorably in Hay's novel, but as "stupid and ill-bred, at the best loyal servants to the gentry and at the worst overly ambitious and a threat to the welfare of Buffland". Sloane considers unfavorable depictions of the working classes inevitable given the plot, and less noticeable than skewed portrayals of the wealthy in other books of the time.

Farnham and Alice Belding are the two characters in the novel who were never part of the working class, but who are scions of wealth, and they are presented favorably. Other, self-made members of the elite are depicted as more vulgar: Mrs. Belding's indulgence in gossip endangers the budding romance between her daughter and Farnham, while Mr. Temple, though brave and steadfast, can discuss only a few topics, such as horse racing, and his speech is described as peppered with profanities. The rest of Buffland's society, as displayed at a party at Temple's house, is composed of "a group of gossipy matrons, vacuous town belles, and silly swains".

Writing

Hay wrote ''The Bread-Winners'' sometime during the winter or spring of 1881–82. At the time, he was busy with his part of the massive Lincoln biography he was compiling withJohn Nicolay

John George Nicolay (February 26, 1832 – September 26, 1901) was a German-born American author and diplomat who served as private secretary to U.S. President Abraham Lincoln and later co-authored '' Abraham Lincoln: A History'', a biography of t ...

, '' Abraham Lincoln: A History''. His work on the Lincoln project had been delayed by diphtheria

Diphtheria is an infection caused by the bacterium '' Corynebacterium diphtheriae''. Most infections are asymptomatic or have a mild clinical course, but in some outbreaks more than 10% of those diagnosed with the disease may die. Signs and s ...

and attendant medical treatment, and was further delayed by ''The Bread-Winners'', as once Hay began work on his only novel, he found himself unable to put it aside. The manuscript was completed by June 1882, when he sent it to Richard Watson Gilder

Richard Watson Gilder (February 8, 1844 – November 19, 1909) was an American poet and editor.

Life and career

Gilder was born on February 8, 1844 at Bordentown, New Jersey. He was the son of Jane (Nutt) Gilder and the Rev. William Henry Gi ...

, editor of ''The Century Magazine

''The Century Magazine'' was an illustrated monthly magazine first published in the United States in 1881 by The Century Company of New York City, which had been bought in that year by Roswell Smith and renamed by him after the Century Associatio ...

'', though whether he was submitting it for publication or advice is unclear. Gilder called it "a powerful book", but did not immediately offer to publish it in his magazine.

Aside from his family and Gilder, likely the only person who knew that Hay was writing a novel was his friend Henry Adams

Henry Brooks Adams (February 16, 1838 – March 27, 1918) was an American historian and a member of the Adams political family, descended from two U.S. Presidents.

As a young Harvard graduate, he served as secretary to his father, Charles Fra ...

. In 1880, Adams had published '' Democracy: An American Novel'', anonymously, and when Hay arrived in Britain in July 1882, he found speculation as to its authorship to be a popular pursuit. Hay sent Adams a copy of a cheap British edition, telling him, "I think of writing a novel in a hurry and printing it as by the author of ''Democracy''."

During the summer of 1882, Hay showed the manuscript to his friend, author William Dean Howells

William Dean Howells (; March 1, 1837 – May 11, 1920) was an American realist novelist, literary critic, and playwright, nicknamed "The Dean of American Letters". He was particularly known for his tenure as editor of ''The Atlantic Monthly'', ...

. Howells urged Aldrich, editor of the ''Atlantic Monthly

''The Atlantic'' is an American magazine and multi-platform publisher. It features articles in the fields of politics, foreign affairs, business and the economy, culture and the arts, technology, and science.

It was founded in 1857 in Boston, ...

'', to publish it. Aldrich agreed, sight unseen, on condition that Hay allow his name to be used as author. Hay was not willing to permit this, and resubmitted the manuscript to Gilder, who agreed to Hay's condition that it be published anonymously. In an anonymous letter to ''The Century Magazine'' after the book was published, Hay alleged that he chose not to reveal his name because he was engaged in business where his stature would be diminished if it were known he had written a novel. According to Dalrymple, the likely real reason was that if it were published under Hay's name, it would harm his ambitions for office, for "to attack labor overtly, in print, would not have been politically prudent." Tyler Dennett

Tyler Dennett (June 13, 1883 Spencer, Wisconsin – December 29, 1949 in Geneva, New York) was an American historian and educator, best known for his book ''John Hay: From Poetry to Politics'' (1933), which won the 1934 Pulitzer Prize for Biograp ...

, in his Pulitzer Prize-winning biography, speculated that Hay would not have been confirmed either as ambassador to Great Britain (1897) or as Secretary of State (1898) had senators associated him with ''The Bread-Winners''.

Although ''The Bread-Winners'' was published anonymously, Hay left clues to his identity throughout the novel. Farnham leads the library board, as did Hay's father. Hay's brother Leonard served on the frontier, like Farnham; another brother grew exotic flowers, as does Farnham. Algonquin Avenue, analog of Cleveland's Euclid Avenue (where Hay lived), is home to the novel's protagonist. In the opening chapter, Farnham's study is described in detail and closely resembles Hay's.

Serialization

In March 1883, the Century Company circulated a

In March 1883, the Century Company circulated a postcard

A postcard or post card is a piece of thick paper or thin cardboard, typically rectangular, intended for writing and mailing without an envelope. Non-rectangular shapes may also be used but are rare. There are novelty exceptions, such as wood ...

, with copies likely sent to newspapers and potential subscribers. Under the heading "Literary Note from The Century Co.", and giving some information about the plot, it announced that an anonymous novel, "unusual in scene and subject, and powerful in treatment" would soon be serialized in the pages of the ''Century''. The serial was originally supposed to begin in April or May, but was postponed because Frances Hodgson Burnett

Frances Eliza Hodgson Burnett (24 November 1849 – 29 October 1924) was a British-American novelist and playwright. She is best known for the three children's novels ''Little Lord Fauntleroy'' (published in 1885–1886), '' A Little ...

's novel ''Through One Administration'' ran long. On July 20, the date of release of the August number, the company placed newspaper advertisements for ''The Bread-Winners'', and said "the story ... abounds in local description and social studies, which heighten the interest and continually pique curiosity as to its authorship." ''The Bread-Winners'' appeared in the ''Century'' from August 1883 to January 1884, when it was issued as a book by Harper and Brothers.

By July 25, 1883, Cleveland newspapers were taking note of the literary mystery, with initial guesses that the author was some former Clevelander who had moved east. In early August, the ''New-York Tribune

The ''New-York Tribune'' was an American newspaper founded in 1841 by editor Horace Greeley. It bore the moniker ''New-York Daily Tribune'' from 1842 to 1866 before returning to its original name. From the 1840s through the 1860s it was the domi ...

'' reported that the author was the late Leonard Case

Leonard Case Jr. (January 27, 1820 – January 6, 1880) was a philanthropist from Cleveland, Ohio, who endowed the Case School of Applied Science (later Case Institute of Technology, merging with Western Reserve University to become Case Western ...

, a Cleveland industrialist and philanthropist—the manuscript had supposedly been found among his papers. Few believed the chronically ill and introverted bachelor could have created the vivid portrait of the shapely Maud Matchin. With Case dismissed, speculation turned to other Ohioans, including Cleveland Superintendent of Schools Burke Aaron Hinsdale, former congressman Albert Gallatin Riddle (author of twelve books), and John Hay. The ''Boston Evening Transcript

The ''Boston Evening Transcript'' was a daily afternoon newspaper in Boston, Massachusetts, published from July 24, 1830, to April 30, 1941.

Beginnings

''The Transcript'' was founded in 1830 by Henry Dutton and James Wentworth of the firm of D ...

'' on August 18 stated, "we have an idea that none of these guesses are correct." Others suggested that the anonymous author of ''Democracy'' (Henry Adams's authorship was not yet known) had penned a second controversial work.

The furor fueled sales, with the ''Century'' later reporting that it gained 20,000 new subscribers because of the serial. The August issue of the ''Century'', in which the first four chapters were serialized, sold out. The September issue also sold out, but went to a second printing. The ''Century'' loudly proclaimed these facts in promotional advertisements, and that it was coining money as a result. As the second installment was read, and the character of Alice Belding became prominent, there was speculation in the press that a female hand had written the novel, with suspicion falling on Constance Fenimore Woolson

Constance Fenimore Woolson (March 5, 1840 – January 24, 1894) was an American novelist, poet, and short story writer. She was a grandniece of James Fenimore Cooper, and is best known for fictions about the Great Lakes region, the Americ ...

(great-niece of James Fenimore Cooper

James Fenimore Cooper (September 15, 1789 – September 14, 1851) was an American writer of the first half of the 19th century, whose historical romances depicting colonist and Indigenous characters from the 17th to the 19th centuries brought h ...

), whose novels were set in eastern Ohio. On September 18, the Washington correspondent for the ''Evening Transcript'' noted the resemblance of Farnham's study to Hay's. Other candidates for the authorship were Howells (though he quickly denied it) and Hay's friend Clarence King

Clarence Rivers King (January 6, 1842 – December 24, 1901) was an American geologist, mountaineer and author. He was the first director of the United States Geological Survey from 1879 to 1881. Nominated by Republican President Rutherford B. Hay ...

, a writer and explorer.

On October 23, 1883, an interview with Hay, who had just returned from a trip to Colorado, appeared in the pages of the ''Cleveland Leader''. Hay said such a novel would be beyond his powers, and that inaccuracies in the depiction of the local scene suggested to him that it was not written by a Clevelander. He offered no candidates who might have written it. Nevertheless, in November, the ''Leader'' ran a column speculating that Hay was the author, based on phrases used both in ''The Bread-Winners'' and in Hay's earlier book, ''Castilian Days'', and by the fact that one character in the novel was from

On October 23, 1883, an interview with Hay, who had just returned from a trip to Colorado, appeared in the pages of the ''Cleveland Leader''. Hay said such a novel would be beyond his powers, and that inaccuracies in the depiction of the local scene suggested to him that it was not written by a Clevelander. He offered no candidates who might have written it. Nevertheless, in November, the ''Leader'' ran a column speculating that Hay was the author, based on phrases used both in ''The Bread-Winners'' and in Hay's earlier book, ''Castilian Days'', and by the fact that one character in the novel was from Salem, Indiana

Salem is a city in and the county seat of Washington Township, Washington County, in the U.S. state of Indiana. The population was 6,319 at the 2010 census.

History

Salem was laid out and platted in 1814. It was named for Salem, North Carolin ...

, Hay's birthplace. Further textual analyses led a number of newspapers in early 1884 (when the novel appeared in book form) to state it had been written by Hay.

Tiring of the guessing game, some newspapers descended to satire. The ''New Orleans Daily Picayune'' surveyed the lengthy list of candidates and announced that "the authors of ''The Bread Winners'' will all meet at Chautauqua

Chautauqua ( ) was an adult education and social movement in the United States, highly popular in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Chautauqua assemblies expanded and spread throughout rural America until the mid-1920s. The Chautauqua bro ...

next summer." Another columnist suggested that a statistic be put in the next census for the number of people named as the author. The appearance of President Arthur's annual message to Congress in December 1883 caused the Rochester ''Herald'' to opine that he had written ''The Bread-Winners'' "because a careful comparison of his message with the story shows many words common to both". Another Upstate New York

Upstate New York is a geographic region consisting of the area of New York State that lies north and northwest of the New York City metropolitan area. Although the precise boundary is debated, Upstate New York excludes New York City and Long Is ...

paper, the Troy ''Times'', evoked Parson Weems

Mason Locke Weems (October 11, 1759 – May 23, 1825), usually referred to as Parson Weems, was an American minister, evangelical bookseller and author who wrote (and rewrote and republished) the first biography of George Washington immediately a ...

's tales of George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of th ...

: "We cannot tell a lie. We wrote ''The Bread winners'' with our own little hatchet. If any one doubts it, we can show him the hatchet." This admission, the Buffalo ''Express'' felt, should put an end to the discussion.

Reaction

Critical

''The Bread-Winners'' received some favorable reviews, such as that by GP Lathrop in ''Atlantic Monthly'' in May 1884. Lathrop applauded the author's portrayal of the characters, and suggested that Maud Matchin was a notable addition to the "gallery of national types" in American literature. The ''Century'' reviewed the book the same month, in an article written by Howells, though he signed it only "W". He saw Maud as "the great discovery of the book" and applauded it as a treatment of an area of American life not previously written about. Similarly, a reviewer for ''Harper's Magazine

''Harper's Magazine'' is a monthly magazine of literature, politics, culture, finance, and the arts. Launched in New York City in June 1850, it is the oldest continuously published monthly magazine in the U.S. (''Scientific American'' is older, b ...

'' liked the parts of the novel set among the lower classes.

According to David E. E. Sloane, "most American critics found it harder to overlook the coarseness of the book and its treatment of the labor problem." A reviewer for ''Literary World'' in January 1884 called ''The Bread-Winners'' a "greasy, slangy, malodorous book ... repulsive from the very first step." ''The Dial'', the following month, praised the author's use of language but deemed the book "a preposterous tissue of incidents" populated by two sets of "exaggerated types", one vicious, the other absurd. ''Continent'', also in February 1884, suggested that "the criticisms as a whole are severe, and justly so, the book being, with all its brilliancy, faithless and hopeless." The ''Springfield Republic'' suggested the author had "no sympathies beyond the circles of wealth and refinement", from which "the workingman is either a murderous ruffian, or a senseless dupe, or a stolid, well-meaning drudge, while the man of wealth is, necessarily, a refined, cultivated hero, handsome, stylish, fascinating." A letter in ''The Century Magazine'' deemed the novel "a piece of snobbishness imported from England... It is simply untruthful... to continue the assertion that trade unions are mainly controlled and strikes originated by agitators, interested only for what they make out of them."

British critics were generally more favorable toward the book. In a column in the ''Pall Mall Gazette

''The Pall Mall Gazette'' was an evening newspaper founded in London on 7 February 1865 by George Murray Smith; its first editor was Frederick Greenwood. In 1921, '' The Globe'' merged into ''The Pall Mall Gazette'', which itself was absorbed int ...

'', ''The Bread-Winners'' was seen as "eminently clever and readable, a worthy contribution to that American novel-literature which is at the present day, on the whole, ahead of our own", a statement which Harper's used in advertisements. A reviewer for London's '' Saturday Review'' described the book as "one of the strongest and most striking stories of the last ten years".

Responses

Hay's novel provoked several works in response. Ohio Congressman Martin Foran announced in March 1884 that he would write a book rebutting the author's view of labor, and published it in 1886 under the title ''The Other Side''. Harriet Boomer Barber (writing under the pen name Faith Templeton) kept a number of Hay's characters, while "turning the American industrial world into a sort of Christian utopia" in her ''Drafted In'' (1888).Stephen Crane

Stephen Crane (November 1, 1871 – June 5, 1900) was an American poet, novelist, and short story writer. Prolific throughout his short life, he wrote notable works in the Realist tradition as well as early examples of American Naturalism an ...

's 1895 short story, "A Christmas Dinner Won in Battle" satirizes ''The Bread-Winners''.

The most successful response was '' The Money-Makers'' (1885), published anonymously by

The most successful response was '' The Money-Makers'' (1885), published anonymously by Henry Francis Keenan

Henry Francis Keenan (May 4, 1850(?) – March 7, 1928) was an American author, best known for his anonymously-published ''The Money-Makers'' (1885), a response to John Hay's ''The Bread-Winners'' (1883).

, a former colleague of Hay's at the ''New-York Tribune''. Keenan's work left little doubt that he had fixed on Hay as author of ''The Bread-Winners'', as it contains characters clearly evoking Hay, his family, and associates. Aaron Grimestone parallels Amasa Stone

Amasa Stone, Jr. (April 27, 1818 – May 11, 1883) was an American industrialist who is best remembered for having created a regional railroad empire centered in the U.S. state of Ohio from 1860 to 1883. He gained fame in New England in the 1840 ...

, Hay's father-in-law. When the Academy Opera House collapses, taking hundreds of lives, Grimestone is deemed responsible for its faulty construction—as Stone was for the deaths in the Ashtabula railway disaster. Grimestone eventually commits suicide by shooting himself in his bathroom, as did Stone in 1883. His daughter Eleanor parallels Clara Stone Hay, and Keenan's descriptions of Eleanor make it clear she is, like Clara, heavyset. The character Archibald Hilliard is modeled after Hay, and the description of his appearance is that of Hay even to the mustache. Hilliard was a secretary to a high official in Washington, and later a diplomat and editor, entering journalism in the same year as Hay. Hilliard becomes a brilliant writer at the ''Atlas'', a reforming New York paper like the ''Tribune'', under the editorship of Horatio Blackdaw, that is, ''Tribune'' editor Whitelaw Reid

Whitelaw Reid (October 27, 1837 – December 15, 1912) was an American politician and newspaper editor, as well as the author of ''Ohio in the War'', a popular work of history.

After assisting Horace Greeley as editor of the ''New-York Tribu ...

. Although she is not physically attractive to him, Hilliard woos Eleanor, convincing himself he is not merely a fortune seeker.

When Hay received a copy of ''The Money-Makers'', according to later accounts, he is said to have hurried to New York to buy up as many copies as he could. He wrote the publisher, William Henry Appleton

William Henry Appleton (January 27, 1814 – October 19, 1899) was an American publisher, eldest son and successor of Daniel Appleton.

Early life

William Henry Appleton was born on January 27, 1814 at Haverhill, Massachusetts. He was the eldest ...

, complaining about the "savage libel" against Amasa Stone. Appleton agreed to several changes, including the manner of suicide, and undertook not to advertise the book further. Later in 1885, a laudatory biographical sketch of Stone, written by "J.H.", appeared in the ''Magazine of Western History'', attributing Stone's suicide to insomnia. According to Clifford A. Bender in his journal article on the Keenan book, "the principal reason ''The Money-Makers'' has remained in obscurity seems to be that John Hay suppressed it," and though he deemed it superior to ''The Bread-Winners'', Dalrymple suggests that Keenan's book "seems more the product of a personal vendetta than an ideological disagreement".

Publication and aftermath

By the standards of the day, ''The Bread-Winners'' was a modest bestseller, with 25,000 copies sold in the United States by mid-1885. Two editions were published in Britain and a pirated edition in Canada, along with a reported sale of 3,000 in the Australian colonies. Translations were published in French, German, and Swedish. By comparison, Adams's ''Democracy'' sold only 14,000 copies in the U.S., and took four years to do so. Nevertheless, ''The Bread-Winners'' did not compare with the leading bestsellers of the 1880s, such asLew Wallace

Lewis Wallace (April 10, 1827February 15, 1905) was an American lawyer, Union general in the American Civil War, governor of the New Mexico Territory, politician, diplomat, and author from Indiana. Among his novels and biographies, Wallace is ...

's '' Ben Hur: A Tale of the Christ'' (1880), which sold 290,000 copies by 1888, and Edward Bellamy

Edward Bellamy (March 26, 1850 – May 22, 1898) was an American author, journalist, and political activist most famous for his utopian novel ''Looking Backward''. Bellamy's vision of a harmonious future world inspired the formation of numerou ...

's story of the future, ''Looking Backward

''Looking Backward: 2000–1887'' is a utopian science fiction novel by Edward Bellamy, a journalist and writer from Chicopee Falls, Massachusetts; it was first published in 1888.

The book was translated into several languages, and in short or ...

'' (1887), which sold nearly 1 million copies in its first decade.

John Hay never acknowledged the book, nor was it attributed to him in his lifetime; as Gilder put it, "guessing right isn't finding out." Hay and Adams amused themselves by suggesting the other might have written it, with Hay writing to his friend, "if you have been guilty of this ... libel upon Cleveland, there is no condonement possible in this or any subsequent worlds." At Hay's death in 1905, obituarists were uncertain whether to assign the novel to him, an exception being ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'', which used handwriting analysis to link the book to him, and published it in its entirety over six Sundays later that year. In 1907, with the permission of Clara Hay, the book was officially acknowledged as his, and in 1916 it was republished in John Hay's name, with an introduction by his son, Clarence.

Historical view

Jaher opined that the book became antiquated as America evolved an understanding of industrial problems, and found Hay's view of labor superficial. Accordingly, the book had little lasting influence, and is remembered only for its onetime popularity and controversy. According to Dalrymple, "the anti-labor novels fail to hold up particularly well. None is a masterpiece of language, plotting, or characterization. Ideologically all seem quite heavy-handed, choosing to make their points with a nearly complete lack of subtlety." Because of his prominence as a statesman, Hay has had a number of biographers in the century since his death. Sloane suggested that early biographers, aware of the nature of the novel's themes, were defensive in their treatment of it. Lorenzo Sears, for example, who wrote of Hay in 1915, called ''The Bread-Winners'' one of several "waifs and strays" of Hay's literary career. Dennett, writing in 1933, deemed the book Hay's honest effort to set forth a problem he could not solve. Other historians were more hostile:Vernon L. Parrington

Vernon Louis Parrington (August 3, 1871 – June 16, 1929) was an American literary historian and scholar. His three-volume history of American letters, ''Main Currents in American Thought'', won the Pulitzer Prize for History in 1928 and was one ...

in 1930 called it a "dishonest book" and "a grotesque fabric smeared with unctuous morality". More recently, Gale (writing in 1978) described it as "a timely, popular and controversial novel that still rewards the sympathetic reader", while Hay's most recent biographer, John Taliaferro (2013) deemed it "certainly no love letter to leveland.

References

Notes

Bibliography

Books

* * * * *Journals and other sources

* * * * * * *External links

Full text

at the

Internet Archive

The Internet Archive is an American digital library with the stated mission of "universal access to all knowledge". It provides free public access to collections of digitized materials, including websites, software applications/games, music, ...

{{DEFAULTSORT:Bread-Winners, The

1883 American novels

Books about labor history

Books by John Hay

Novels first published in serial form

Works published anonymously