Tetrahymena Rostrata on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Tetrahymena'', a

The life cycle of ''T. thermophila'' consists of an alternation between asexual and sexual stages. In nutrient rich media during vegetative growth cells reproduce asexually by

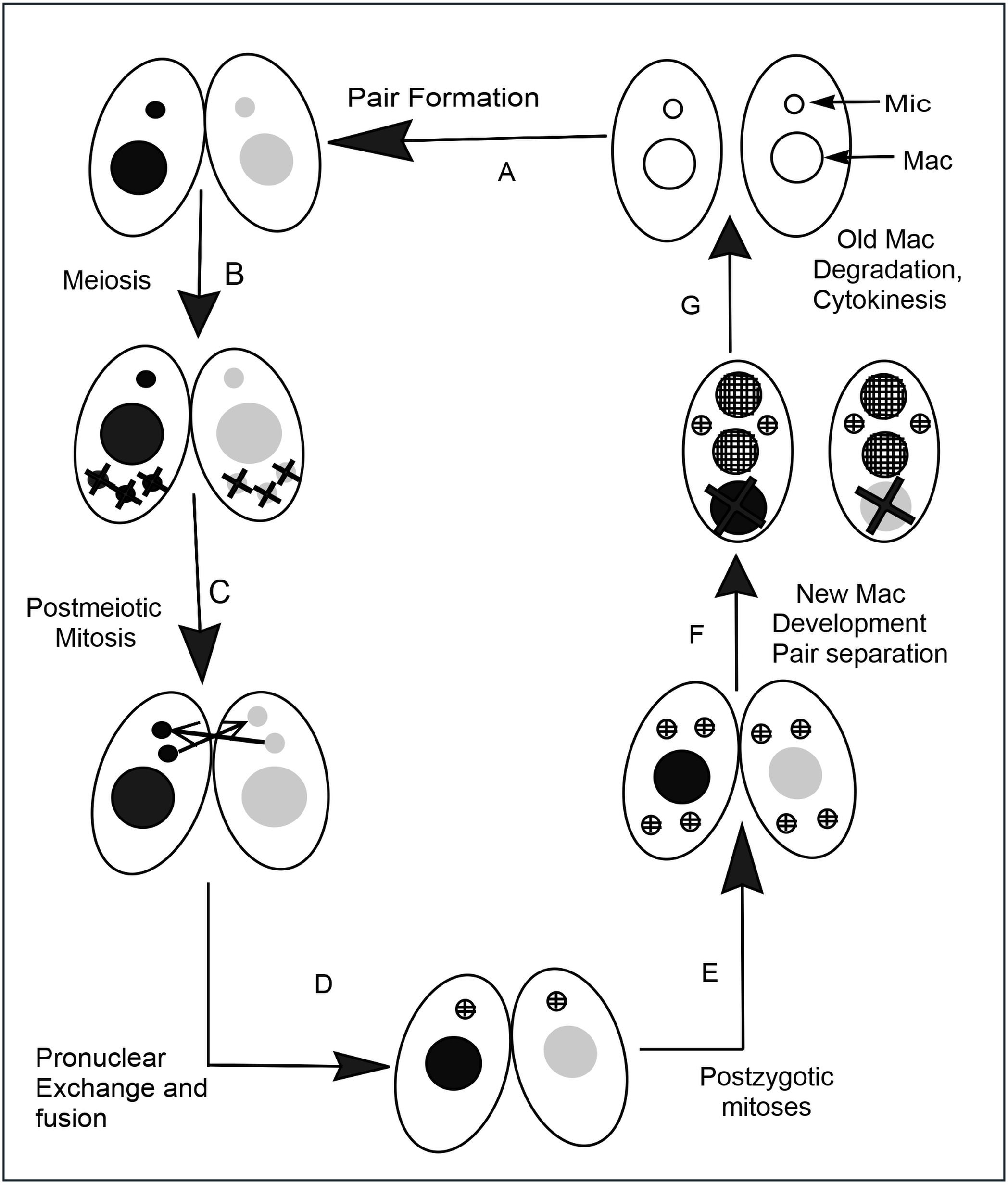

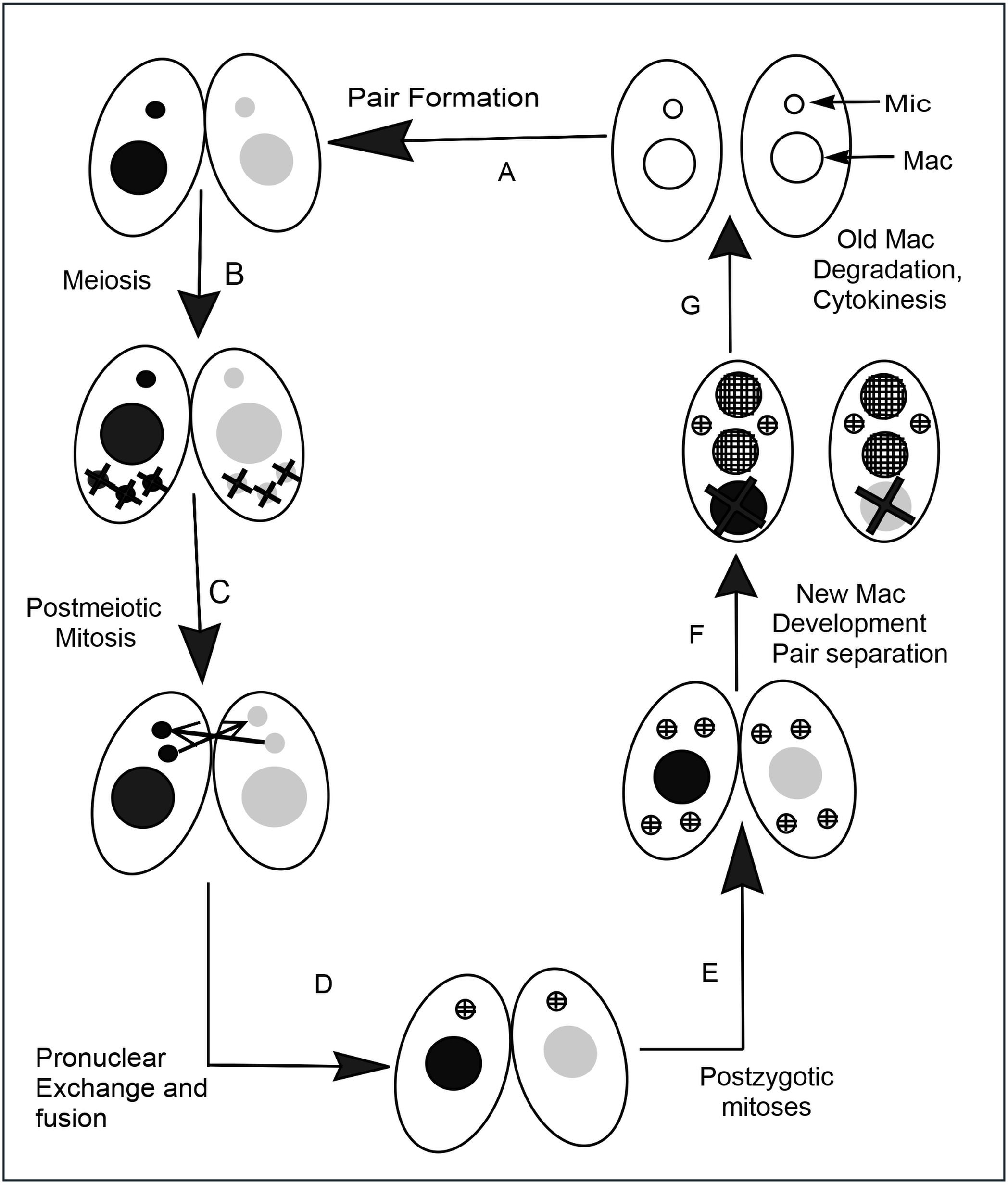

The life cycle of ''T. thermophila'' consists of an alternation between asexual and sexual stages. In nutrient rich media during vegetative growth cells reproduce asexually by  It is at this junctional zone that several hundred fusion pores form, allowing for the mutual exchange of protein, RNA and eventually a meiotic product of their micronucleus. This whole process takes about 12 hours at 30 °C, but even longer than this at cooler temperatures. The sequence of events during conjugation is outlined in the accompanying figure.

The larger polyploid macronucleus is transcriptionally active, meaning its genes are actively expressed, and so it controls somatic cell functions during vegetative growth. The polyploid nature of the macronucleus refers to the fact that it contains approximately 200–300 autonomously replicating linear DNA mini-chromosomes. These minichromosomes have their own telomeres and are derived via site-specific fragmentation of the five original micronuclear chromosomes during sexual development. In T. thermophila each of these minichromosomes encodes multiple genes and exists at a copy number of approximately 45-50 within the macronucleus. The exception to this is the minichromosome encoding the rDNA, which is massively upregulated, existing at a copy number of approximately 10,000 within the macronucleus. Because the macronucleus divides amitotically during binary fission, these minichromosomes are un-equally divided between the clonal daughter cells. Through natural or artificial selection, this method of DNA partitioning in the somatic genome can lead to clonal cell lines with different macronuclear phenotypes fixed for a particular trait, in a process called phenotypic assortment. In this way, the polyploid genome can fine-tune its adaptation to environmental conditions through gain of beneficial mutations on any given mini-chromosome whose replication is then selected for, or conversely, loss of a minichromosome which accrues a negative mutation. However, the macronucleus is only propagated from one cell to the next during the asexual, vegetative stage of the life cycle, and so it is never directly inherited by sexual progeny. Only beneficial mutations that occur in the germline micronucleus of ''T. thermophila'' are passed down between generations, but these mutations would never be selected for environmentally in the parental cells because they are not expressed.

It is at this junctional zone that several hundred fusion pores form, allowing for the mutual exchange of protein, RNA and eventually a meiotic product of their micronucleus. This whole process takes about 12 hours at 30 °C, but even longer than this at cooler temperatures. The sequence of events during conjugation is outlined in the accompanying figure.

The larger polyploid macronucleus is transcriptionally active, meaning its genes are actively expressed, and so it controls somatic cell functions during vegetative growth. The polyploid nature of the macronucleus refers to the fact that it contains approximately 200–300 autonomously replicating linear DNA mini-chromosomes. These minichromosomes have their own telomeres and are derived via site-specific fragmentation of the five original micronuclear chromosomes during sexual development. In T. thermophila each of these minichromosomes encodes multiple genes and exists at a copy number of approximately 45-50 within the macronucleus. The exception to this is the minichromosome encoding the rDNA, which is massively upregulated, existing at a copy number of approximately 10,000 within the macronucleus. Because the macronucleus divides amitotically during binary fission, these minichromosomes are un-equally divided between the clonal daughter cells. Through natural or artificial selection, this method of DNA partitioning in the somatic genome can lead to clonal cell lines with different macronuclear phenotypes fixed for a particular trait, in a process called phenotypic assortment. In this way, the polyploid genome can fine-tune its adaptation to environmental conditions through gain of beneficial mutations on any given mini-chromosome whose replication is then selected for, or conversely, loss of a minichromosome which accrues a negative mutation. However, the macronucleus is only propagated from one cell to the next during the asexual, vegetative stage of the life cycle, and so it is never directly inherited by sexual progeny. Only beneficial mutations that occur in the germline micronucleus of ''T. thermophila'' are passed down between generations, but these mutations would never be selected for environmentally in the parental cells because they are not expressed.

''Tetrahymena'' Stock Center at Cornell UniversityASSET: Advancing Secondary Science Education thru ''Tetrahymena''''Tetrahymena'' Genome DatabaseBiogeography and Biodiversity of ''Tetrahymena''''Tetrahymena thermophila'' Genome Project

at

''Tetrahymena thermophila'' Genome Sequence Synopsis''Tetrahymena thermophila'' genome paper''Tetrahymena'' experiments

on

''Tetrahymena'' image galleryAll Creatures Great and Small: Elizabeth Blackburn

{{Taxonbar, from=Q1198419 Ciliate genera Oligohymenophorea Model organisms

unicellular

A unicellular organism, also known as a single-celled organism, is an organism that consists of a single cell, unlike a multicellular organism that consists of multiple cells. Organisms fall into two general categories: prokaryotic organisms and ...

eukaryote

Eukaryotes () are organisms whose cells have a nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, and many unicellular organisms, are Eukaryotes. They belong to the group of organisms Eukaryota or Eukarya, which is one of the three domains of life. Bacte ...

, is a genus of free-living ciliate

The ciliates are a group of alveolates characterized by the presence of hair-like organelles called cilia, which are identical in structure to flagellum, eukaryotic flagella, but are in general shorter and present in much larger numbers, with a ...

s. The genus Tetrahymena is the most widely studied member of its phylum

In biology, a phylum (; plural: phyla) is a level of classification or taxonomic rank below kingdom and above class. Traditionally, in botany the term division has been used instead of phylum, although the International Code of Nomenclature f ...

. It can produce, store and react with different types of hormones. Tetrahymena cells can recognize both related and hostile cells.

They can also switch from commensalistic to pathogenic

In biology, a pathogen ( el, πάθος, "suffering", "passion" and , "producer of") in the oldest and broadest sense, is any organism or agent that can produce disease. A pathogen may also be referred to as an infectious agent, or simply a germ ...

modes of survival. They are common in freshwater lakes, ponds, and streams.

''Tetrahymena'' species used as model organisms

A model organism (often shortened to model) is a non-human species that is extensively studied to understand particular biological phenomena, with the expectation that discoveries made in the model organism will provide insight into the working ...

in biomedical research are ''T. thermophila

''Tetrahymena thermophila'' is a species of Ciliophora in the family Tetrahymenidae. It is a free living protozoa and occurs in fresh water.

There is little information on the ecology and natural history of this species, but it is the most wid ...

'' and '' T. pyriformis''.

''T. thermophila'': a model organism in experimental biology

As a ciliatedprotozoan

Protozoa (singular: protozoan or protozoon; alternative plural: protozoans) are a group of single-celled eukaryotes, either free-living or parasitic, that feed on organic matter such as other microorganisms or organic tissues and debris. Histo ...

, ''Tetrahymena thermophila'' exhibits nuclear dimorphism Nuclear dimorphism is a term referred to the special characteristic of having two different kinds of nuclei in a cell. There are many differences between the types of nuclei. This feature is observed in protozoan ciliates, like ''Tetrahymena'', and ...

: two types of cell nuclei. They have a bigger, non-germline macronucleus

A macronucleus (formerly also meganucleus) is the larger type of nucleus in ciliates. Macronuclei are polyploid and undergo direct division without mitosis. It controls the non-reproductive cell functions, such as metabolism. During conjugation, t ...

and a small, germline

In biology and genetics, the germline is the population of a multicellular organism's cells that pass on their genetic material to the progeny (offspring). In other words, they are the cells that form the egg, sperm and the fertilised egg. They ...

micronucleus

Micronucleus is the name given to the small nucleus that forms whenever a chromosome or a fragment of a chromosome is not incorporated into one of the daughter nuclei during cell division. It usually is a sign of genotoxic events and chromosomal i ...

in each cell at the same time and these two carry out different functions with distinct cytological and biological properties. This unique versatility allows scientists to use ''Tetrahymena'' to identify several key factors regarding gene expression

Gene expression is the process by which information from a gene is used in the synthesis of a functional gene product that enables it to produce end products, protein or non-coding RNA, and ultimately affect a phenotype, as the final effect. The ...

and genome integrity. In addition, ''Tetrahymena'' possess hundreds of cilia

The cilium, plural cilia (), is a membrane-bound organelle found on most types of eukaryotic cell, and certain microorganisms known as ciliates. Cilia are absent in bacteria and archaea. The cilium has the shape of a slender threadlike projecti ...

and has complicated microtubule

Microtubules are polymers of tubulin that form part of the cytoskeleton and provide structure and shape to eukaryotic cells. Microtubules can be as long as 50 micrometres, as wide as 23 to 27 nm and have an inner diameter between 11 an ...

structures, making it an optimal model to illustrate the diversity and functions of microtubule arrays.

Because ''Tetrahymena'' can be grown in a large quantity in the laboratory with ease, it has been a great source for biochemical analysis for years, specifically for enzymatic

Enzymes () are proteins that act as biological catalysts by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different molecules known as products. A ...

activities and purification of sub-cellular components. In addition, with the advancement of genetic techniques it has become an excellent model to study the gene function ''in vivo''. The recent sequencing of the macronucleus genome should ensure that ''Tetrahymena'' will be continuously used as a model system.

''Tetrahymena thermophila'' exists in 7 different sexes (mating type

Mating types are the microorganism equivalent to sexes in multicellular lifeforms and are thought to be the ancestor to distinct Sex, sexes. They also occur in macro-organisms such as fungi.

Definition

Mating types are the microorganism equivalent ...

s) that can reproduce in 21 different combinations, and a single tetrahymena cannot reproduce sexually with itself. Each organism "decides" which sex it will become during mating, through a stochastic

Stochastic (, ) refers to the property of being well described by a random probability distribution. Although stochasticity and randomness are distinct in that the former refers to a modeling approach and the latter refers to phenomena themselv ...

process.

Studies on ''Tetrahymena'' have contributed to several scientific milestones including:

# First cell which showed synchronized division, which led to the first insights into the existence of mechanisms which control the cell cycle

The cell cycle, or cell-division cycle, is the series of events that take place in a cell that cause it to divide into two daughter cells. These events include the duplication of its DNA (DNA replication) and some of its organelles, and subs ...

.

# Identification and purification of the first cytoskeleton

The cytoskeleton is a complex, dynamic network of interlinking protein filaments present in the cytoplasm of all cells, including those of bacteria and archaea. In eukaryotes, it extends from the cell nucleus to the cell membrane and is compos ...

based motor protein

Motor proteins are a class of molecular motors that can move along the cytoplasm of cells. They convert chemical energy into mechanical work by the hydrolysis of ATP. Flagellar rotation, however, is powered by a proton pump.

Cellular functions ...

such as ''dynein

Dyneins are a family of cytoskeletal motor proteins that move along microtubules in cells. They convert the chemical energy stored in ATP to mechanical work. Dynein transports various cellular cargos, provides forces and displacements importa ...

''.

# Aid in the discovery of ''lysosomes

A lysosome () is a membrane-bound organelle found in many animal cells. They are spherical vesicles that contain hydrolytic enzymes that can break down many kinds of biomolecules. A lysosome has a specific composition, of both its membrane prote ...

'' and ''peroxisomes

A peroxisome () is a membrane-bound organelle, a type of microbody, found in the cytoplasm of virtually all eukaryotic cells. Peroxisomes are oxidative organelles. Frequently, molecular oxygen serves as a co-substrate, from which hydrogen pero ...

''.

# Early molecular identification of somatic genome rearrangement.

# Discovery of the molecular structure of ''telomeres

A telomere (; ) is a region of repetitive nucleotide sequences associated with specialized proteins at the ends of linear chromosomes. Although there are different architectures, telomeres, in a broad sense, are a widespread genetic feature mos ...

'', ''telomerase

Telomerase, also called terminal transferase, is a ribonucleoprotein that adds a species-dependent telomere repeat sequence to the 3' end of telomeres. A telomere is a region of repetitive sequences at each end of the chromosomes of most euka ...

'' enzyme, the templating role of telomerase RNA and their roles in cellular senescence and chromosome healing (for which a Nobel Prize was won).

# Nobel Prize–winning co-discovery (1989, in Chemistry) of catalytic RNA

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule essential in various biological roles in coding, decoding, regulation and expression of genes. RNA and deoxyribonucleic acid ( DNA) are nucleic acids. Along with lipids, proteins, and carbohydra ...

(''ribozyme

Ribozymes (ribonucleic acid enzymes) are RNA molecules that have the ability to catalyze specific biochemical reactions, including RNA splicing in gene expression, similar to the action of protein enzymes. The 1982 discovery of ribozymes demonst ...

'').

# Discovery of the function of histone

In biology, histones are highly basic proteins abundant in lysine and arginine residues that are found in eukaryotic cell nuclei. They act as spools around which DNA winds to create structural units called nucleosomes. Nucleosomes in turn are wr ...

acetylation

:

In organic chemistry, acetylation is an organic esterification reaction with acetic acid. It introduces an acetyl group into a chemical compound. Such compounds are termed ''acetate esters'' or simply '' acetates''. Deacetylation is the oppo ...

.

# Demonstration of the roles of posttranslational modification

Post-translational modification (PTM) is the covalent and generally enzymatic modification of proteins following protein biosynthesis. This process occurs in the endoplasmic reticulum and the golgi apparatus. Proteins are synthesized by ribosome ...

such as acetylation and glycylation on tubulins

Tubulin in molecular biology can refer either to the tubulin protein superfamily of globular proteins, or one of the member proteins of that superfamily. α- and β-tubulins polymerize into microtubules, a major component of the eukaryotic cytoske ...

and discovery of the enzymes responsible for some of these modifications (glutamylation)

# Crystal structure of 40S ribosome in complex with its initiation factor eIF1

# First demonstration that two of the "universal" stop codon

In molecular biology (specifically protein biosynthesis), a stop codon (or termination codon) is a codon (nucleotide triplet within messenger RNA) that signals the termination of the translation process of the current protein. Most codons in me ...

s, UAA and UAG, will code for the amino acid glutamine

Glutamine (symbol Gln or Q) is an α-amino acid that is used in the biosynthesis of proteins. Its side chain is similar to that of glutamic acid, except the carboxylic acid group is replaced by an amide. It is classified as a charge-neutral, ...

in some eukaryotes, leaving UGA as the only termination codon in these organisms.

Life cycle

The life cycle of ''T. thermophila'' consists of an alternation between asexual and sexual stages. In nutrient rich media during vegetative growth cells reproduce asexually by

The life cycle of ''T. thermophila'' consists of an alternation between asexual and sexual stages. In nutrient rich media during vegetative growth cells reproduce asexually by binary fission

Binary may refer to:

Science and technology Mathematics

* Binary number, a representation of numbers using only two digits (0 and 1)

* Binary function, a function that takes two arguments

* Binary operation, a mathematical operation that t ...

. This type of cell division occurs by a sequence of morphogenetic events that results in the development of duplicate sets of cell structures, one for each daughter cell. Only during starvation conditions will cells commit to sexual conjugation

Isogamy is a form of sexual reproduction that involves gametes of the same morphology (indistinguishable in shape and size), found in most unicellular eukaryotes. Because both gametes look alike, they generally cannot be classified as male or fe ...

, pairing and fusing with a cell of opposite mating type. Tetrahymena has seven mating types; each of which can mate with any of the other six without preference, but not its own.

Typical of ciliates, ''T. thermophila'' differentiates its genome into two functionally distinct types of nuclei, each specifically used during the two different stages of the life cycle. The diploid germline micronucleus is transcriptionally silent and only plays a role during sexual life stages. The germline nucleus contains 5 pairs of chromosomes which encode the heritable information passed down from one sexual generation to the next. During sexual conjugation, haploid micronuclear meiotic products from both parental cells fuse, leading to the creation of a new micro- and macronucleus in progeny cells. Sexual conjugation occurs when cells starved for at least 2hrs in a nutrient-depleted media encounter a cell of complementary mating type. After a brief period of co-stimulation (~1hr), starved cells begin to pair at their anterior ends to form a specialized region of membrane called the conjugation junction.

It is at this junctional zone that several hundred fusion pores form, allowing for the mutual exchange of protein, RNA and eventually a meiotic product of their micronucleus. This whole process takes about 12 hours at 30 °C, but even longer than this at cooler temperatures. The sequence of events during conjugation is outlined in the accompanying figure.

The larger polyploid macronucleus is transcriptionally active, meaning its genes are actively expressed, and so it controls somatic cell functions during vegetative growth. The polyploid nature of the macronucleus refers to the fact that it contains approximately 200–300 autonomously replicating linear DNA mini-chromosomes. These minichromosomes have their own telomeres and are derived via site-specific fragmentation of the five original micronuclear chromosomes during sexual development. In T. thermophila each of these minichromosomes encodes multiple genes and exists at a copy number of approximately 45-50 within the macronucleus. The exception to this is the minichromosome encoding the rDNA, which is massively upregulated, existing at a copy number of approximately 10,000 within the macronucleus. Because the macronucleus divides amitotically during binary fission, these minichromosomes are un-equally divided between the clonal daughter cells. Through natural or artificial selection, this method of DNA partitioning in the somatic genome can lead to clonal cell lines with different macronuclear phenotypes fixed for a particular trait, in a process called phenotypic assortment. In this way, the polyploid genome can fine-tune its adaptation to environmental conditions through gain of beneficial mutations on any given mini-chromosome whose replication is then selected for, or conversely, loss of a minichromosome which accrues a negative mutation. However, the macronucleus is only propagated from one cell to the next during the asexual, vegetative stage of the life cycle, and so it is never directly inherited by sexual progeny. Only beneficial mutations that occur in the germline micronucleus of ''T. thermophila'' are passed down between generations, but these mutations would never be selected for environmentally in the parental cells because they are not expressed.

It is at this junctional zone that several hundred fusion pores form, allowing for the mutual exchange of protein, RNA and eventually a meiotic product of their micronucleus. This whole process takes about 12 hours at 30 °C, but even longer than this at cooler temperatures. The sequence of events during conjugation is outlined in the accompanying figure.

The larger polyploid macronucleus is transcriptionally active, meaning its genes are actively expressed, and so it controls somatic cell functions during vegetative growth. The polyploid nature of the macronucleus refers to the fact that it contains approximately 200–300 autonomously replicating linear DNA mini-chromosomes. These minichromosomes have their own telomeres and are derived via site-specific fragmentation of the five original micronuclear chromosomes during sexual development. In T. thermophila each of these minichromosomes encodes multiple genes and exists at a copy number of approximately 45-50 within the macronucleus. The exception to this is the minichromosome encoding the rDNA, which is massively upregulated, existing at a copy number of approximately 10,000 within the macronucleus. Because the macronucleus divides amitotically during binary fission, these minichromosomes are un-equally divided between the clonal daughter cells. Through natural or artificial selection, this method of DNA partitioning in the somatic genome can lead to clonal cell lines with different macronuclear phenotypes fixed for a particular trait, in a process called phenotypic assortment. In this way, the polyploid genome can fine-tune its adaptation to environmental conditions through gain of beneficial mutations on any given mini-chromosome whose replication is then selected for, or conversely, loss of a minichromosome which accrues a negative mutation. However, the macronucleus is only propagated from one cell to the next during the asexual, vegetative stage of the life cycle, and so it is never directly inherited by sexual progeny. Only beneficial mutations that occur in the germline micronucleus of ''T. thermophila'' are passed down between generations, but these mutations would never be selected for environmentally in the parental cells because they are not expressed.

Behavior

Free swimming cells of ''Tetrahymena'' are attracted to certain chemicals bychemokinesis Chemokinesis is chemically prompted kinesis, a motile response of unicellular prokaryotic or eukaryotic organisms to chemicals that cause the cell to make some kind of change in their migratory/swimming behaviour. Changes involve an increase or dec ...

. The major chemo-attractants are peptides and/or proteins.

A 2016 study found that cultured ''Tetrahymena'' have the capacity to 'learn' the shape and size of their swimming space. Cells confined in a droplet of a water for a short time were, upon release, found to repeat the circular swimming trajectories 'learned' in the droplet. The diameter and duration of these swimming paths reflected the size of the droplet and time allowed to adapt.

DNA repair

It is common among protists that the sexual cycle is inducible by stressful conditions such as starvation. Such conditions often cause DNA damage. A central feature of meiosis is homologous recombination between non-sister chromosomes. In ''T. thermophila'' this process of meiotic recombination may be beneficial for repairing DNA damages caused by starvation. Exposure of ''T. thermophila'' to UV light resulted in a greater than 100-fold increase in ''Rad51

DNA repair protein RAD51 homolog 1 is a protein encoded by the gene ''RAD51''. The enzyme encoded by this gene is a member of the RAD51 protein family which assists in repair of DNA double strand breaks. RAD51 family members are homologous to th ...

'' gene expression. Treatment with the DNA alkylating agent methyl methanesulfonate

Methyl methanesulfonate (MMS), also known as methyl mesylate, is an alkylating agent and a carcinogen. It is also a suspected reproductive toxicant, and may also be a skin/sense organ toxicant. It is used in cancer treatment.Rad51

DNA repair protein RAD51 homolog 1 is a protein encoded by the gene ''RAD51''. The enzyme encoded by this gene is a member of the RAD51 protein family which assists in repair of DNA double strand breaks. RAD51 family members are homologous to th ...

recombinase

Recombinases are genetic recombination enzymes.

Site specific recombinases

DNA recombinases are widely used in multicellular organisms to manipulate the structure of genomes, and to control gene expression. These enzymes, derived from bacteria (b ...

of ''T. thermophila'' is a homolog of the ''Escherichia coli'' RecA

RecA is a 38 kilodalton protein essential for the repair and maintenance of DNA. A RecA structural and functional homolog has been found in every species in which one has been seriously sought and serves as an archetype for this class of homolog ...

recombinase. In ''T. thermophila'', Rad51 participates in homologous recombination

Homologous recombination is a type of genetic recombination in which genetic information is exchanged between two similar or identical molecules of double-stranded or single-stranded nucleic acids (usually DNA as in cellular organisms but may ...

during mitosis

In cell biology, mitosis () is a part of the cell cycle in which replicated chromosomes are separated into two new nuclei. Cell division by mitosis gives rise to genetically identical cells in which the total number of chromosomes is mainta ...

, meiosis

Meiosis (; , since it is a reductional division) is a special type of cell division of germ cells in sexually-reproducing organisms that produces the gametes, such as sperm or egg cells. It involves two rounds of division that ultimately resu ...

and in the repair of double-strand breaks. During conjugation, Rad51 is necessary for completion of meiosis. Meiosis in ''T. thermophila'' appears to employ a Mus81-dependent pathway that does not use a synaptonemal complex

The synaptonemal complex (SC) is a protein structure that forms between homologous chromosomes (two pairs of sister chromatids) during meiosis and is thought to mediate synapsis and recombination during meiosis I in eukaryotes. It is currentl ...

and is considered secondary in most other model eukaryote

Eukaryotes () are organisms whose cells have a nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, and many unicellular organisms, are Eukaryotes. They belong to the group of organisms Eukaryota or Eukarya, which is one of the three domains of life. Bacte ...

s. This pathway includes the Mus81 resolvase and the Sgs1 helicase. The Sgs1 helicase appears to promote the non-crossover outcome of meiotic recombinational repair of DNA, a pathway that generates little genetic variation.

Phenotypic and Genotypic Plasticity

Many species of Tetrahymena are known to display unique response mechanisms to stress and various environmental pressures. The unique genomic architecture of the ciliates (presence of a MIC, high ploidy, large number of chromosomes, etc.) allows for differential gene expression, as well as increased genomic flexibility. The following is a non-exhaustive list of examples of phenotypic and genotypic plasticity in the Tetrahymena genus.Inducible Trophic Polymorphisms

T. vorax is known for its inducible trophic polymorphisms, an ecologically offensive tactic that allows it to change its feeding strategy and diet by altering its morphology. Normally, T. vorax is a bacterivorous microstome around 60 μm in length. However, it has the ability to switch into a carnivorous macrostome around 200 μm in length that can feed on larger competitors. If T. vorax cells are too nutrient starved to undertake transformation, they have also been recorded as transforming into a third “tailed”-microstome morph, thought to be a defense mechanism in response to cannibalistic pressure. While T. vorax is the most well studied Tetrahymena that exhibits inducible trophic polymorphisms, many lesser known species are able to undertake transformation as well, including T. paulina and T. paravorax. However, only T. vorax has been recorded as having both a macrostome and tailed-microstome form. These morphological switches are triggered by an abundance of stomatin in the environment, a mixture of metabolic compounds released by competitor species, such as Paramecium, Colpidium, and other Tetrahymena. Specifically, chromatographic analysis has revealed that ferrous iron, hypoxanthine, and uracil are the chemicals in stomatin responsible for triggering the morphological change. Many researchers cite “starvation conditions” as inducing the transformation, as in nature, the compound inducers are in highest concentration after microstomal ciliates have grazed down bacterial populations, and ciliates populations are high. When the chemical inducers are in high concentration, T. vorax cells will transform at higher rates, allowing them to prey on their former trophic competitors. The exact genetic, and structural mechanisms that underlie T. vorax transformation are unknown. However, some progress has been made in identifying candidate genes. Researchers from the University of Alabama have used cDNA subtraction to remove actively transcribed DNA from microstome and macrostome T. vorax cells, leaving only differentially transcribed cDNA molecules. While nine differentiation-specific genes were found, the most frequently expressed candidate gene was identified as a novel sequence, ''SUBII-TG''. The sequenced region of ''SUBII-TG'' was 912 bp long and consists of three largely identical 105 bp open-reading frames. A northern blot analysis revealed that low levels of transcription are detected in microstome cells, while high levels of transcription occur in macrostome cells. Furthermore, when the researchers limited ''SUBII-TG'' expression in the presence of stomatin (using antisense oligonucleotide methods), a 55% reduction in ''SUBII-TG'' mRNA correlated with a 51% decrease in transformation, supporting the notion that the gene is at least partially responsible for controlling the transformation in T. vorax. However, very little is known about the ''SUBII-TG'' gene. Researchers were only able to sequence a portion of the entire open-reading frame, and other candidate genes have not been investigated thoroughly. mRNA and amino acid sequencing indicate that ubiquitin may play a crucial role in allowing transformation to take place as well. However, no known genes in the ubiquitin family have been identified in T. vorax. Finally, the genetic mechanisms of the “tailed” microstome morph are completely unknown.Metal Resistance, Gene & Genome Amplification

Other related species exhibit their own unique responses to various stressors. In T. thermophila, chromosome amplification and gene expansion are inducible responses to common organometallic pollutants such as Cadmium, Copper, and Lead. Strains of T. thermophila that were exposed to large quantities of Cd2+ over time were found to have a 5-fold increase of ''MTT1'', and ''MTT3'' (metallothionein genes that code for Cadmium and Lead binding proteins) as well as ''CNBDP'', an unrelated gene that lies just upstream of ''MTT1'' on the same chromosome. The fact that a non-metallothionein gene on the same locus as ''MTT1'' and ''MTT3'' increased copy number indicates that the entire chromosome had been amplified, as opposed to just specific genes. Tetrahymena species are 45-ploid for their macronucleus, meaning that the wild type of T. thermophila normally contains 45 copies of each chromosome. While the actual number of unique chromosomes are unknown, the number is thought to be around 187 in the MAC, and 5 in the MIC. Thus, the Ca2+ adapted strain contained 225 copies of the specific chromosome in question. This resulted in a nearly 28 times increase in detected expression levels of ''MTT1'', and slightly less in ''MTT3''. Interestingly, when researchers grew a sample of the T. thermophila population in normal growth medium (lacking Cd2+) for 1 month, the number of ''MTT1'', ''MTT3'', and ''CNBDP'' genes decreased to an average of 3 copies (135C). By 7 months in normal growth medium, the T. thermophila cells were found reduced to just the wild type copy number (45C). When researchers returned cells from the same colony to Cd2+ medium, within a week ''MTT1'', ''MTT3'', and ''CNBDP'' genes increased to 3 copies once again (135C). Thus, the authors argue that chromosome amplification is an inducible and reversible mechanism in the Tetrahymena genetic response to metal stress. Researchers also used gene-knockdown experiments, where the copy number of another metallothionein gene on a different chromosome, ''MTT5'', was dramatically reduced. Within a week, the new strain was found to have developed 4 novel genes from at least 1 duplication of ''MTT1''. However, chromosome duplication had not taken place, as indicated by the wild-type ploidy and the normal quantity of other genes on the same chromosomes. Rather, researchers believe that the duplication resulted from homologous recombination events, producing transcriptionally active, upregulated genes that carry repeated ''MTT1''.Enhanced Motility and Dispersal

T. thermophila also undergoes phenotypic changes when faced with limited resource availability. Cells are capable of changing their shape and size, along with behavioral swimming strategies in response to starvation. The more motile cells that change in response to starvation are known as dispersers, or disperser cells. While rates and levels of phenotypic change differ between strains, disperser cells form in nearly all strains of T. thermophila when faced with starvation. Dispersers, and non-dispersing cells both become dramatically thinner and smaller, increasing the basal body and cilia density, allowing them to swim between 2 to 3 times faster than normal cells. Some strains of T. thermophila have also been found to develop a single, non-beating, enlarged cilia that assists the cell in steering or directing movement. While the behavior has been shown to correlate with faster dispersal and form as a reversible trait in Tetrahymena cells, little is known about the genetic or cellular mechanisms that allow for its development. Furthermore, other studies show that when genetically variable populations of T. thermophila were starved, dispersal cells actually increased in cell length, despite still becoming thinner. More research is needed to determine the genetic mechanisms that underlie disperser formation.Species in genus

Species in this genus include. *Tetrahymena americanis

''Tetrahymena'', a unicellular eukaryote, is a genus of free-living ciliates. The genus Tetrahymena is the most widely studied member of its phylum. It can produce, store and react with different types of hormones. Tetrahymena cells can recog ...

* Tetrahymena asiatica

*Tetrahymena australis

''Tetrahymena'', a unicellular eukaryote, is a genus of free-living ciliates. The genus Tetrahymena is the most widely studied member of its phylum. It can produce, store and react with different types of hormones. Tetrahymena cells can recog ...

* Tetrahymena bergeri

* Tetrahymena borealis

* Tetrahymena canadensis

* Tetrahymena capricornis

*Tetrahymena caudata

''Tetrahymena'', a unicellular eukaryote, is a genus of free-living ciliates. The genus Tetrahymena is the most widely studied member of its phylum. It can produce, store and react with different types of hormones. Tetrahymena cells can recog ...

* Tetrahymena chironomi

*Tetrahymena corlissi

''Tetrahymena'', a unicellular eukaryote, is a genus of free-living ciliates. The genus Tetrahymena is the most widely studied member of its phylum. It can produce, store and react with different types of hormones. Tetrahymena cells can recog ...

* Tetrahymena cosmopolitanis

* Tetrahymena dimorpha

*Tetrahymena edaphoni

''Tetrahymena'', a unicellular eukaryote, is a genus of free-living ciliates. The genus Tetrahymena is the most widely studied member of its phylum. It can produce, store and react with different types of hormones. Tetrahymena cells can recog ...

*Tetrahymena elliotti

''Tetrahymena'', a unicellular eukaryote, is a genus of free-living ciliates. The genus Tetrahymena is the most widely studied member of its phylum. It can produce, store and react with different types of hormones. Tetrahymena cells can recog ...

* Tetrahymena empidokyrea

* Tetrahymena farahensis

* Tetrahymena farleyi

* Tetrahymena furgasoni

* Tetrahymena glochidiophila

* Tetrahymena hegewischi

*Tetrahymena hyperangularis

''Tetrahymena'', a unicellular eukaryote, is a genus of free-living ciliates. The genus Tetrahymena is the most widely studied member of its phylum. It can produce, store and react with different types of hormones. Tetrahymena cells can rec ...

* Tetrahymena leucophrys

*Tetrahymena limacis

''Tetrahymena'', a unicellular eukaryote, is a genus of free-living ciliates. The genus Tetrahymena is the most widely studied member of its phylum. It can produce, store and react with different types of hormones. Tetrahymena cells can recog ...

* Tetrahymena lwoffi

* Tetrahymena malaccensis

* Tetrahymena mimbres

*Tetrahymena mobilis

''Tetrahymena'', a unicellular eukaryote, is a genus of free-living ciliates. The genus Tetrahymena is the most widely studied member of its phylum. It can produce, store and react with different types of hormones. Tetrahymena cells can recog ...

* Tetrahymena nanneyi

* Tetrahymena nipissingi

*Tetrahymena paravorax

''Tetrahymena'', a unicellular eukaryote, is a genus of free-living ciliates. The genus Tetrahymena is the most widely studied member of its phylum. It can produce, store and react with different types of hormones. Tetrahymena cells can recog ...

* Tetrahymena patula

* Tetrahymena pigmentosa

*Tetrahymena pyriformis

''Tetrahymena pyriformis'' is a species of Ciliophora in the family Tetrahymenidae

Tetrahymenidae is a family of ciliates.

References

Ciliate families

Oligohymenophorea

{{ciliate-stub ....

It is one of the most commonly ciliated mod ...

* Tetrahymena rostrata

* Tetrahymena rotunda

* Tetrahymena setifera

* Tetrahymena setigera

*Tetrahymena setosa

''Tetrahymena'', a unicellular eukaryote, is a genus of free-living ciliates. The genus Tetrahymena is the most widely studied member of its phylum. It can produce, store and react with different types of hormones. Tetrahymena cells can recog ...

* Tetrahymena shanghaiensis

*Tetrahymena sialidos

''Tetrahymena'', a Unicellular organism, unicellular eukaryote, is a genus of free-living ciliates. The genus Tetrahymena is the most widely studied member of its phylum. It can produce, store and react with different types of hormones. Tetrah ...

* Tetrahymena silvana

* Tetrahymena skappus

* Tetrahymena sonneborni

* Tetrahymena stegomyiae

* Tetrahymena thermophila

''Tetrahymena thermophila'' is a species of Ciliophora in the family Tetrahymenidae. It is a free living protozoa and occurs in fresh water.

There is little information on the ecology and natural history of this species, but it is the most wi ...

* Tetrahymena tropicalis

* Tetrahymena vorax

References

Further reading

* * *External links

''Tetrahymena'' Stock Center at Cornell University

at

The Institute for Genomic Research

The J. Craig Venter Institute (JCVI) is a non-profit genomics research institute founded by J. Craig Venter, Ph.D. in October 2006. The institute was the result of consolidating four organizations: the Center for the Advancement of G ...

''Tetrahymena thermophila'' Genome Sequence Synopsis

on

Journal of Visualized Experiments

The ''Journal of Visualized Experiments'' (styled ''JoVE'') is a peer-reviewed scientific journal that publishes experimental methods in video format. The journal is based in Cambridge, MA and was established in December 2006. Moshe Pritsker is the ...

(JoVE) website

*Microbial Digital Specimen Archives''Tetrahymena'' image gallery

{{Taxonbar, from=Q1198419 Ciliate genera Oligohymenophorea Model organisms