Tetrahedral Carbonyl Addition Compound on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A tetrahedral intermediate is a

The nucleophilic attack on the carbonyl group proceeds via the Bürgi-Dunitz trajectory. The angle between the line of nucleophilic attack and the C-O bond is greater than 90˚ due to a better orbital overlap between the HOMO of the nucleophile and the π* LUMO of the C-O double bond.

The nucleophilic attack on the carbonyl group proceeds via the Bürgi-Dunitz trajectory. The angle between the line of nucleophilic attack and the C-O bond is greater than 90˚ due to a better orbital overlap between the HOMO of the nucleophile and the π* LUMO of the C-O double bond.

# compounds with a strong electron-withdrawing group attached to the acyl carbon (e.g. ''N'',''N''-dimethyltrifluoroacetamide)

# compounds with donor groups that are poorly conjugated with the potential carbonyl group (e.g.

# compounds with a strong electron-withdrawing group attached to the acyl carbon (e.g. ''N'',''N''-dimethyltrifluoroacetamide)

# compounds with donor groups that are poorly conjugated with the potential carbonyl group (e.g.

The more recent x-ray crystal structure of 1-aza-3,5,7-trimethyladamantan-2-one is a good model for cationic tetrahedral intermediate. The C1-N1 bond is rather long 55.2(4) pm and C1-O1(2) bonds are shortened 38.2(4) pm The protonated nitrogen atom N1 is a great amine leaving group.

The more recent x-ray crystal structure of 1-aza-3,5,7-trimethyladamantan-2-one is a good model for cationic tetrahedral intermediate. The C1-N1 bond is rather long 55.2(4) pm and C1-O1(2) bonds are shortened 38.2(4) pm The protonated nitrogen atom N1 is a great amine leaving group.

In 2002 David Evans et al. observed a very stable neutral tetrahedral intermediate in the reaction of ''N''-acylpyrroles with organometallic compounds, followed by protonation with ammonium chloride producing a carbinol. The C1-N1 bond 47.84(14) pmis longer than the usual Csp3-Npyrrole bond which range from 141.2-145.8 pm. In contrast, the C1-O1 bond 41.15(13) pmis shorter than the average Csp3-OH bond which is about 143.2 pm. The elongated C1-N1, and shortened C1-O1 bonds are explained with an anomeric effect resulting from the interaction of the oxygen lone pairs with the σ*C-N orbital. Similarly, an interaction of an oxygen lone pair with σ*C-C orbital should be responsible for the lengthened C1-C2 bond 52.75(15) pmcompared to the average Csp2-Csp2 bonds which are 151.3 pm. Also, the C1-C11 bond 52.16(17) pmis slightly shorter than the average Csp3-Csp3 bond which is around 153.0 pm.

In 2002 David Evans et al. observed a very stable neutral tetrahedral intermediate in the reaction of ''N''-acylpyrroles with organometallic compounds, followed by protonation with ammonium chloride producing a carbinol. The C1-N1 bond 47.84(14) pmis longer than the usual Csp3-Npyrrole bond which range from 141.2-145.8 pm. In contrast, the C1-O1 bond 41.15(13) pmis shorter than the average Csp3-OH bond which is about 143.2 pm. The elongated C1-N1, and shortened C1-O1 bonds are explained with an anomeric effect resulting from the interaction of the oxygen lone pairs with the σ*C-N orbital. Similarly, an interaction of an oxygen lone pair with σ*C-C orbital should be responsible for the lengthened C1-C2 bond 52.75(15) pmcompared to the average Csp2-Csp2 bonds which are 151.3 pm. Also, the C1-C11 bond 52.16(17) pmis slightly shorter than the average Csp3-Csp3 bond which is around 153.0 pm.

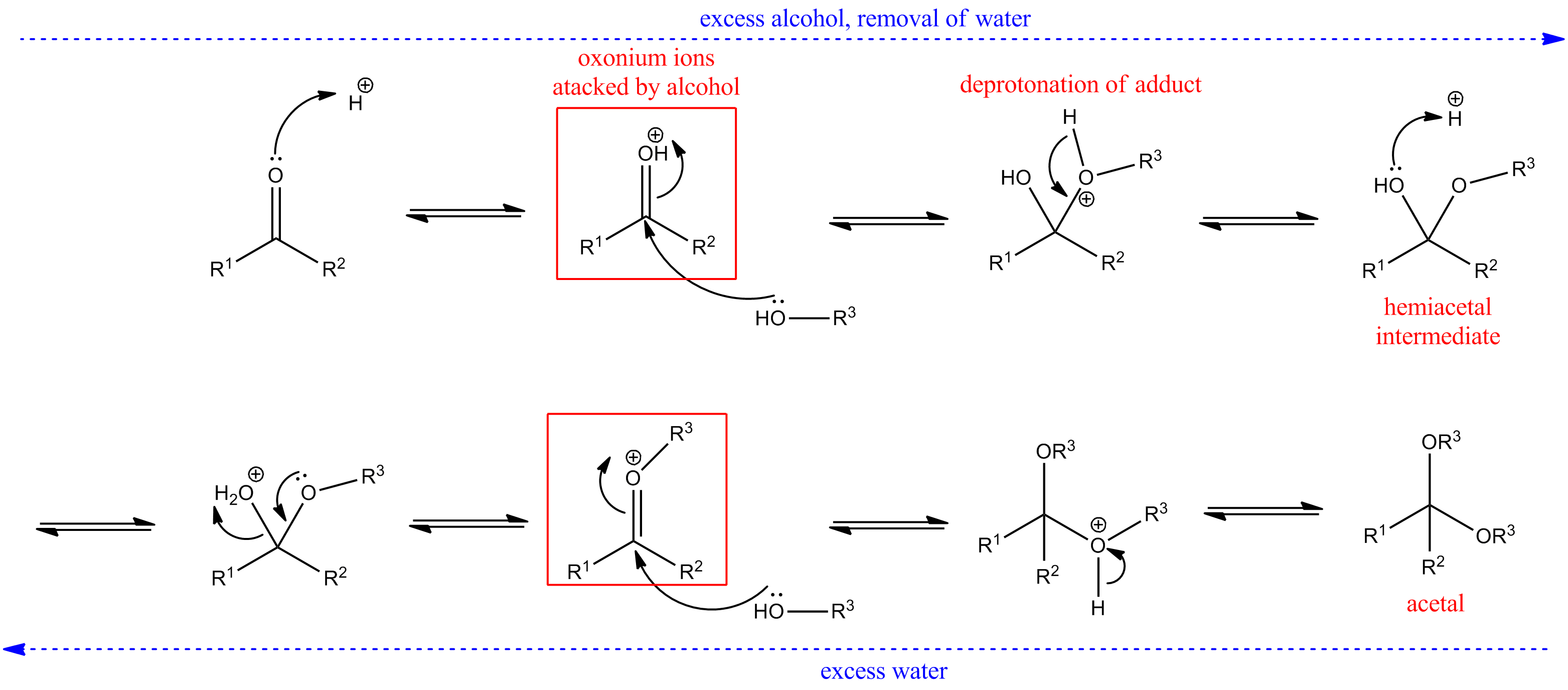

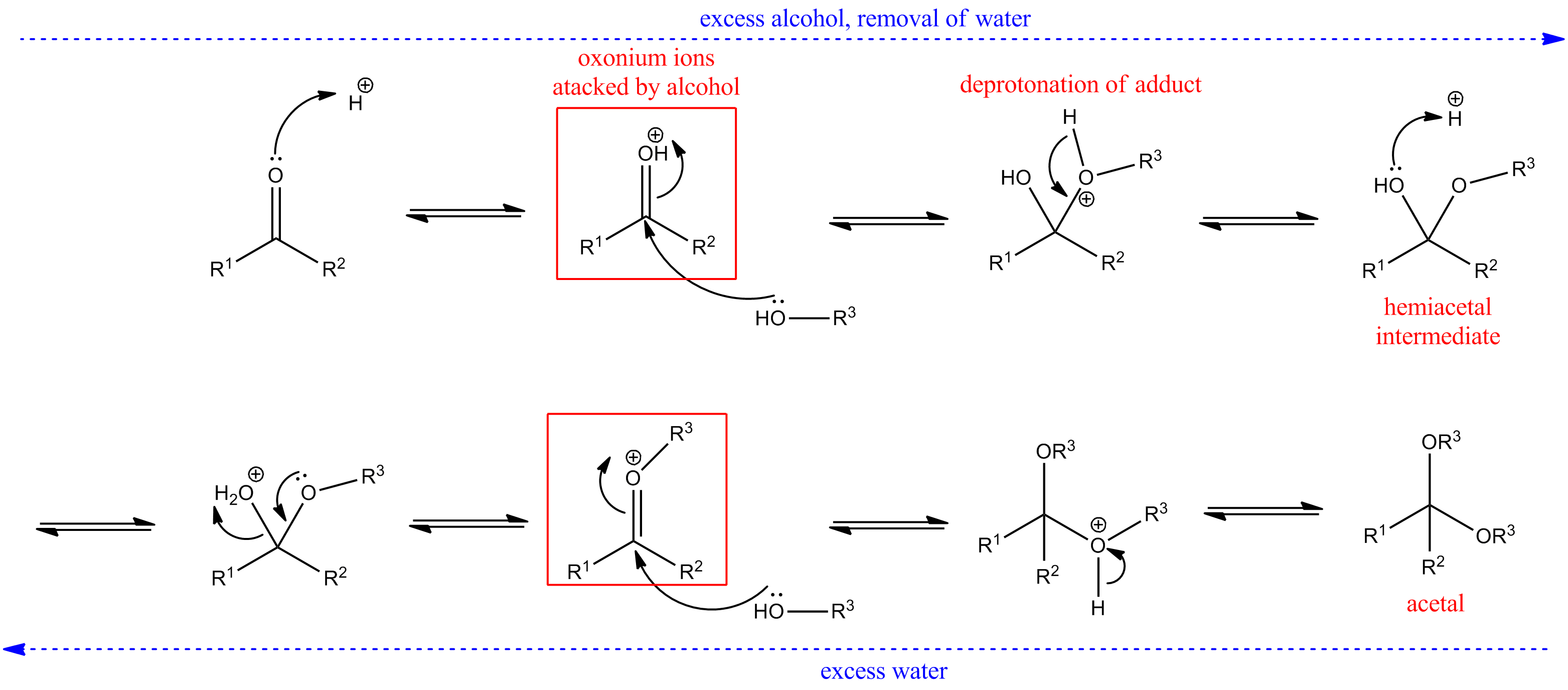

In the presence of acid, hemiacetals can undergo an elimination reaction, losing the oxygen atom that once belonged to the parent aldehyde’s carbonyl group. These oxonium ions are powerful electrophiles, and react rapidly with a second molecule of alcohol to form new, stable compounds, called acetals. The whole mechanism of acetal formation from hemiacetal is drawn below.

In the presence of acid, hemiacetals can undergo an elimination reaction, losing the oxygen atom that once belonged to the parent aldehyde’s carbonyl group. These oxonium ions are powerful electrophiles, and react rapidly with a second molecule of alcohol to form new, stable compounds, called acetals. The whole mechanism of acetal formation from hemiacetal is drawn below.

Acetals, as already pointed out, are stable tetrahedral intermediates so they can be used as protective groups in organic synthesis. Acetals are stable under basic conditions, so they can be used to protect ketones from a base. The acetal group is hydrolyzed under acidic conditions. An example with a

Acetals, as already pointed out, are stable tetrahedral intermediates so they can be used as protective groups in organic synthesis. Acetals are stable under basic conditions, so they can be used to protect ketones from a base. The acetal group is hydrolyzed under acidic conditions. An example with a

reaction intermediate

In chemistry, a reaction intermediate or an intermediate is a molecular entity that is formed from the reactants (or preceding intermediates) but is consumed in further reactions in stepwise chemical reactions that contain multiple elementary ...

in which the bond arrangement around an initially double-bonded carbon atom has been transformed from trigonal to tetrahedral. Tetrahedral intermediates result from nucleophilic addition

In organic chemistry, a nucleophilic addition reaction is an addition reaction where a chemical compound with an electrophilic double or triple bond reacts with a nucleophile, such that the double or triple bond is broken. Nucleophilic additions ...

to a carbonyl

In organic chemistry, a carbonyl group is a functional group composed of a carbon atom double-bonded to an oxygen atom: C=O. It is common to several classes of organic compounds, as part of many larger functional groups. A compound containin ...

group. The stability of tetrahedral intermediate depends on the ability of the groups

A group is a number of persons or things that are located, gathered, or classed together.

Groups of people

* Cultural group, a group whose members share the same cultural identity

* Ethnic group, a group whose members share the same ethnic ide ...

attached to the new tetrahedral carbon atom to leave with the negative charge. Tetrahedral intermediates are very significant in organic syntheses and biological systems as a key intermediate in ester

In chemistry, an ester is a compound derived from an oxoacid (organic or inorganic) in which at least one hydroxyl group () is replaced by an alkoxy group (), as in the substitution reaction of a carboxylic acid and an alcohol. Glycerides ...

ification, transesterification

In organic chemistry, transesterification is the process of exchanging the organic group R″ of an ester with the organic group R' of an alcohol. These reactions are often catalyzed by the addition of an acid or base catalyst. The reaction ca ...

, ester hydrolysis, formation and hydrolysis of amides

In organic chemistry, an amide, also known as an organic amide or a carboxamide, is a compound with the general formula , where R, R', and R″ represent organic groups or hydrogen atoms. The amide group is called a peptide bond when it i ...

and peptides

Peptides (, ) are short chains of amino acids linked by peptide bonds. Long chains of amino acids are called proteins. Chains of fewer than twenty amino acids are called oligopeptides, and include dipeptides, tripeptides, and tetrapeptides. ...

, hydride reductions, and other chemical reactions.

History

One of the earliest accounts of the tetrahedral intermediate came fromRainer Ludwig Claisen

Rainer Ludwig Claisen (; 14 January 1851 – 5 January 1930) was a German chemist best known for his work with condensations of carbonyls and sigmatropic rearrangements. He was born in Cologne as the son of a jurist and studied chemistry at the u ...

in 1887. In the reaction of benzyl benzoate

Benzyl benzoate is an organic compound which is used as a medication and insect repellent. As a medication it is used to treat scabies and lice. For scabies either permethrin or malathion is typically preferred. It is applied to the skin as a lot ...

with sodium methoxide

Sodium methoxide is the simplest sodium alkoxide. With the formula , it is a white solid, which is formed by the deprotonation of methanol. Itis a widely used reagent in industry and the laboratory. It is also a dangerously caustic base. ...

, and methyl benzoate

Methyl benzoate is an organic compound. It is an ester with the chemical formula C6H5CO2CH3. It is a colorless liquid that is poorly soluble in water, but miscible with organic solvents. Methyl benzoate has a pleasant smell, strongly reminiscen ...

with sodium benzyloxide, he observed a white precipitate which under acidic conditions yields benzyl benzoate, methyl benzoate, methanol, and benzyl alcohol. He named the likely common intermediate “.”

Victor Grignard

Francois Auguste Victor Grignard (6 May 1871 – 13 December 1935) was a French chemist who won the Nobel Prize for his discovery of the eponymously named Grignard reagent and Grignard reaction, both of which are important in the formation of c ...

assumed the existence of unstable tetrahedral intermediate in 1901, while investigating the reaction of esters

In chemistry, an ester is a compound derived from an oxoacid (organic or inorganic) in which at least one hydroxyl group () is replaced by an alkoxy group (), as in the substitution reaction of a carboxylic acid and an alcohol. Glycerides are ...

with organomagnesium reagents.

The first evidence for tetrahedral intermediates in the substitution reactions of carboxylic derivatives was provided by Myron L. Bender

Myron Lee Bender (1924–1988) was born in St. Louis, Missouri. He obtained his B.S. (1944) and his Ph.D. (1948) from Purdue University. The latter was under the direction of Henry B. Hass. After postdoctoral research under Paul D. Barlett (H ...

in 1951. He labeled carboxylic acid derivatives with oxygen isotope O18 and reacted these derivatives with water to make labeled carboxylic acids. At the end of the reaction he found that the remaining starting material had a decreased proportion of labeled oxygen, which is consistent with the existence of the tetrahedral intermediate.

Reaction mechanism

The nucleophilic attack on the carbonyl group proceeds via the Bürgi-Dunitz trajectory. The angle between the line of nucleophilic attack and the C-O bond is greater than 90˚ due to a better orbital overlap between the HOMO of the nucleophile and the π* LUMO of the C-O double bond.

The nucleophilic attack on the carbonyl group proceeds via the Bürgi-Dunitz trajectory. The angle between the line of nucleophilic attack and the C-O bond is greater than 90˚ due to a better orbital overlap between the HOMO of the nucleophile and the π* LUMO of the C-O double bond.

Structure of tetrahedral intermediates

General features

Although the tetrahedral intermediates are usually transient intermediates, many compounds of this general structures are known. The reactions of aldehydes, ketones, and their derivatives frequently have a detectable tetrahedral intermediate, while for the reactions of derivatives of carboxylic acids this is not the case. At the oxidation level of carboxylic acid derivatives, the groups such as OR, OAr, NR2, or Cl are conjugated with the carbonyl group, which means that addition to the carbonyl group is thermodynamically less favored than addition to corresponding aldehyde or ketone. Stable tetrahedral intermediates of carboxylic acid derivatives do exist and they usually possess at least one of the following four structural features: # polycyclic structures (e.g.tetrodotoxin

Tetrodotoxin (TTX) is a potent neurotoxin. Its name derives from Tetraodontiformes, an order that includes pufferfish, porcupinefish, ocean sunfish, and triggerfish; several of these species carry the toxin. Although tetrodotoxin was discove ...

) cyclol

The cyclol hypothesis is the now discredited first structural model of a folded, globular protein, formulated in the 1930s. It was based on the cyclol reaction of peptide bonds proposed by physicist Frederick Frank in 1936, in which two p ...

)

# compounds with sulfur atoms bonded to the anomeric centre (e.g., )

These compounds were used to study the kinetics of tetrahedral intermediate decomposition into its respective carbonyl species, and to measure the IR, UV, and NMR spectra of the tetrahedral adduct.

X-ray crystal structure determination

The first X-ray crystal structures of tetrahedral intermediates were obtained in 1973 from bovine trypsin crystallized with bovine pancreatic trypsin inhibitor, and in 1974 from porcine trypsin crystallized with soybean trypsin inhibitor. In both cases the tetrahedral intermediate is stabilized in the active sites of enzymes, which have evolved to stabilize the transition state of peptide hydrolysis. Some insight into the structure of tetrahedral intermediate can be obtained from the crystal structure of ''N''-brosylmitomycin A, crystallized in 1967. The tetrahedral carbon C17 forms a 136.54 pm bond with O3, which is shorter than C8-O3 bond (142.31 pm). In contrast, C17-N2 bond (149.06 pm) is longer than N1-C1 bond (148.75 pm) and N1-C11 bond (147.85 pm) due to donation of O3 lone pair into σ* orbital of C17-N2. This model however is forced into tetracyclic sceleton, and tetrahedral O3 is methylated which makes it a poor model overall. The more recent x-ray crystal structure of 1-aza-3,5,7-trimethyladamantan-2-one is a good model for cationic tetrahedral intermediate. The C1-N1 bond is rather long 55.2(4) pm and C1-O1(2) bonds are shortened 38.2(4) pm The protonated nitrogen atom N1 is a great amine leaving group.

The more recent x-ray crystal structure of 1-aza-3,5,7-trimethyladamantan-2-one is a good model for cationic tetrahedral intermediate. The C1-N1 bond is rather long 55.2(4) pm and C1-O1(2) bonds are shortened 38.2(4) pm The protonated nitrogen atom N1 is a great amine leaving group.

In 2002 David Evans et al. observed a very stable neutral tetrahedral intermediate in the reaction of ''N''-acylpyrroles with organometallic compounds, followed by protonation with ammonium chloride producing a carbinol. The C1-N1 bond 47.84(14) pmis longer than the usual Csp3-Npyrrole bond which range from 141.2-145.8 pm. In contrast, the C1-O1 bond 41.15(13) pmis shorter than the average Csp3-OH bond which is about 143.2 pm. The elongated C1-N1, and shortened C1-O1 bonds are explained with an anomeric effect resulting from the interaction of the oxygen lone pairs with the σ*C-N orbital. Similarly, an interaction of an oxygen lone pair with σ*C-C orbital should be responsible for the lengthened C1-C2 bond 52.75(15) pmcompared to the average Csp2-Csp2 bonds which are 151.3 pm. Also, the C1-C11 bond 52.16(17) pmis slightly shorter than the average Csp3-Csp3 bond which is around 153.0 pm.

In 2002 David Evans et al. observed a very stable neutral tetrahedral intermediate in the reaction of ''N''-acylpyrroles with organometallic compounds, followed by protonation with ammonium chloride producing a carbinol. The C1-N1 bond 47.84(14) pmis longer than the usual Csp3-Npyrrole bond which range from 141.2-145.8 pm. In contrast, the C1-O1 bond 41.15(13) pmis shorter than the average Csp3-OH bond which is about 143.2 pm. The elongated C1-N1, and shortened C1-O1 bonds are explained with an anomeric effect resulting from the interaction of the oxygen lone pairs with the σ*C-N orbital. Similarly, an interaction of an oxygen lone pair with σ*C-C orbital should be responsible for the lengthened C1-C2 bond 52.75(15) pmcompared to the average Csp2-Csp2 bonds which are 151.3 pm. Also, the C1-C11 bond 52.16(17) pmis slightly shorter than the average Csp3-Csp3 bond which is around 153.0 pm.

Stability of tetrahedral intermediates

Acetals and hemiacetals

Hemiacetal

A hemiacetal or a hemiketal has the general formula R1R2C(OH)OR, where R1 or R2 is hydrogen or an organic substituent. They generally result from the addition of an alcohol to an aldehyde or a ketone, although the latter are sometimes called hemike ...

s and acetal

In organic chemistry, an acetal is a functional group with the connectivity . Here, the R groups can be organic fragments (a carbon atom, with arbitrary other atoms attached to that) or hydrogen, while the R' groups must be organic fragment ...

s are essentially tetrahedral intermediates. They form when nucleophiles add to a carbonyl group, but unlike tetrahedral intermediates they can be very stable and used as protective group

A protecting group or protective group is introduced into a molecule by chemical modification of a functional group to obtain chemoselectivity in a subsequent chemical reaction. It plays an important role in multistep organic synthesis.

In man ...

s in synthetic chemistry. A very well known reaction occurs when acetaldehyde is dissolved in methanol, producing a hemiacetal. Most hemiacetals are unstable with respect to their parent aldehydes and alcohols. For example, the equilibrium constant for reaction of acetaldehyde with simple alcohols is about 0.5, where the equilibrium constant is defined as K = emiacetal ldehydealcohol]. Hemiacetals of ketones (sometimes called hemiketals) are even less stable than those of aldehydes. However, cyclic hemiacetals and hemiacetals bearing electron withdrawing groups are stable. Electron-withdrawing groups attached to the carbonyl atom shift the equilibrium constant toward the hemiacetal. They increase the polarization of the carbonyl group, which already has a positively polarized carbonyl carbon, and make it even more prone to attack by a nucleophile. The chart below shows the extent of hydration of some carbonyl compounds. Hexafluoroacetone

Hexafluoroacetone (HFA) is a chemical compound with the formula (CF3)2CO. It is structurally similar to acetone; however, its reactivity is markedly different. It a colourless, hygroscopic, nonflammable, highly reactive gas characterized by a mus ...

is probably the most hydrated carbonyl compound possible. Formaldehyde

Formaldehyde ( , ) ( systematic name methanal) is a naturally occurring organic compound with the formula and structure . The pure compound is a pungent, colourless gas that polymerises spontaneously into paraformaldehyde (refer to section ...

reacts with water so readily because its substituents are very small- a purely steric effect.

Cyclopropanone

Cyclopropanone is an organic compound with molecular formula (CH2)2CO consisting of a cyclopropane carbon framework with a ketone functional group. The parent compound is labile, being highly sensitive toward even weak nucleophiles. Surrogates o ...

s- three-membered ring ketones- are also hydrated to a significant extent. Since three-membered rings are very strained (bond angles forced to be 60˚), sp3 hybridization is more favorable than sp2 hybridization. For the sp3 hybridized hydrate the bonds have to be distorted by about 49˚, while for the sp2 hybridized ketone the bond angle distortion is about 60˚. So the addition to the carbonyl group allows some of the strain inherent in the small ring to be released, which is why cyclopropanone and cyclobutanone

Cyclobutanone is an organic compound with molecular formula (CH2)3CO. It is a four-membered cyclic ketone (cycloalkanone). It is a colorless volatile liquid at room temperature. Since cyclopropanone is highly sensitive, cyclobutanone is the ...

are very reactive electrophiles. For larger rings, where the bond angles are not as distorted, the stability of the hemiacetals is due to entropy and the proximity of the nucleophile to the carbonyl group. Formation of an acyclic acetal involves a decrease in entropy because two molecules are consumed for every one produced. In contrast, the formation of cyclic hemiacetals involves a single molecule reacting with itself, making the reaction more favorable. Another way to understand the stability of cyclic hemiacetals is to look at the equilibrium constant as the ratio of the forward and backward reaction rate. For a cyclic hemiacetal the reaction is intramolecular so the nucleophile is always held close to the carbonyl group ready to attack, so the forward rate of reaction is much higher than the backward rate. Many biologically relevant sugars, such as glucose

Glucose is a simple sugar with the molecular formula . Glucose is overall the most abundant monosaccharide, a subcategory of carbohydrates. Glucose is mainly made by plants and most algae during photosynthesis from water and carbon dioxide, usi ...

, are cyclic hemiacetals.

In the presence of acid, hemiacetals can undergo an elimination reaction, losing the oxygen atom that once belonged to the parent aldehyde’s carbonyl group. These oxonium ions are powerful electrophiles, and react rapidly with a second molecule of alcohol to form new, stable compounds, called acetals. The whole mechanism of acetal formation from hemiacetal is drawn below.

In the presence of acid, hemiacetals can undergo an elimination reaction, losing the oxygen atom that once belonged to the parent aldehyde’s carbonyl group. These oxonium ions are powerful electrophiles, and react rapidly with a second molecule of alcohol to form new, stable compounds, called acetals. The whole mechanism of acetal formation from hemiacetal is drawn below.

Acetals, as already pointed out, are stable tetrahedral intermediates so they can be used as protective groups in organic synthesis. Acetals are stable under basic conditions, so they can be used to protect ketones from a base. The acetal group is hydrolyzed under acidic conditions. An example with a

Acetals, as already pointed out, are stable tetrahedral intermediates so they can be used as protective groups in organic synthesis. Acetals are stable under basic conditions, so they can be used to protect ketones from a base. The acetal group is hydrolyzed under acidic conditions. An example with a dioxolane

Dioxolane is a heterocyclic acetal with the chemical formula (CH2)2O2CH2. It is related to tetrahydrofuran by interchange of one oxygen for a CH2 group. The corresponding saturated 6-membered C4O2 rings are called dioxanes. The isomeric 1,2-dioxo ...

protecting group is given below.

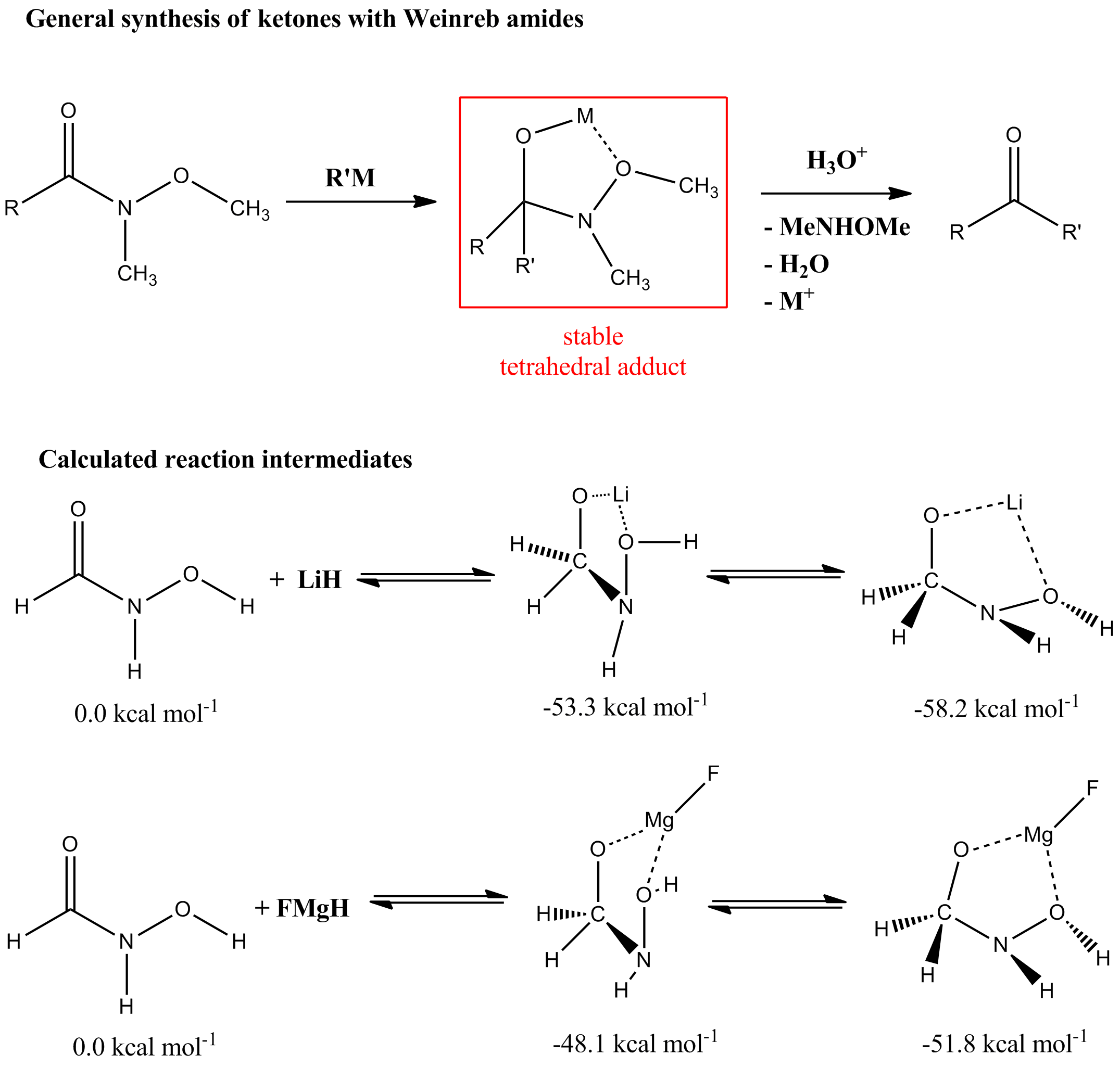

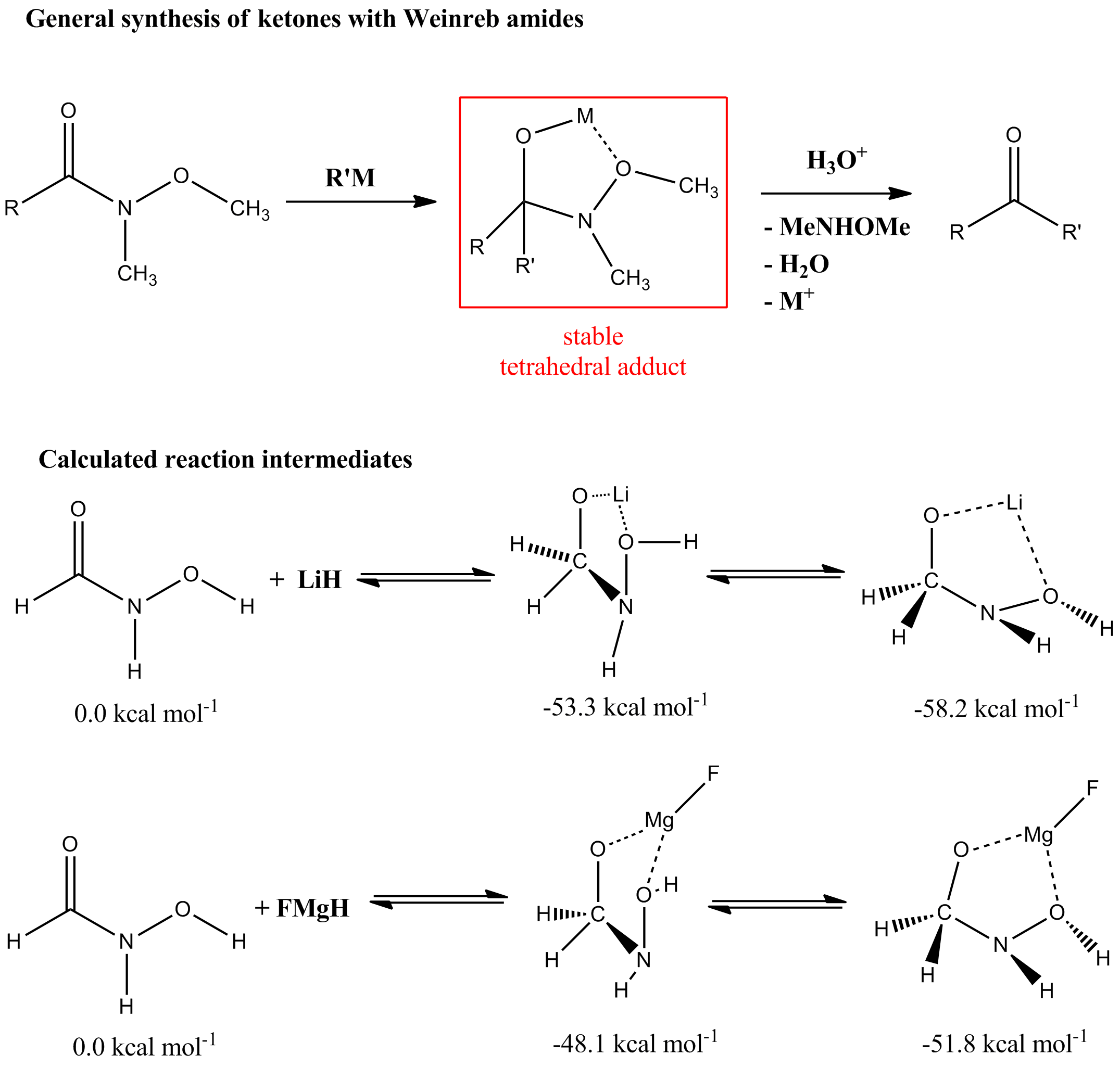

Weinreb amides

Weinreb amides are ''N''-methoxy-''N''-methylcarboxylic acid amides. Weinreb amides are reacted with organometallic compounds to give, on protonation, ketones (seeWeinreb ketone synthesis

The Weinreb–Nahm ketone synthesis is a chemical reaction used in organic chemistry to make carbon–carbon bonds. It was discovered in 1981 by Steven M. Weinreb and Steven Nahm as a method to synthesize ketones. The original reaction involved ...

). It is generally accepted that the high yields of ketones are due to the high stability of the chelate

Chelation is a type of bonding of ions and molecules to metal ions. It involves the formation or presence of two or more separate coordinate bonds between a polydentate (multiple bonded) ligand and a single central metal atom. These ligands are ...

d five-membered ring intermediate. Quantum mechanical calculations have shown that the tetrahedral adduct is formed easily and it is fairly stable, in agreement with the experimental results. The very facile reaction of Weinreb amides with organolithium and Grignard reagents

A Grignard reagent or Grignard compound is a chemical compound with the general formula , where X is a halogen and R is an organic group, normally an alkyl or aryl. Two typical examples are methylmagnesium chloride and phenylmagnesium bromide ...

results from the chelate stabilization in the tetrahedral adduct and, more importantly, the transition state leading to the adduct. The tetrahedral adducts are shown below.

Applications in biomedicine

Drug design

A solvated ligand that binds the protein of interest is likely to exist as an equilibrium mixture of several conformers. Likewise the solvated protein also exists as several conformers in equilibrium. Formation of protein-ligand complex includes displacement of the solvent molecules that occupy the binding site of the ligand, to produce a solvated complex. Because this necessarily means that the interaction is entropically disfavored, highly favorable enthalpic contacts between the protein and the ligand must compensate for the entropic loss. The design of new ligands is usually based on the modification of known ligands for the target proteins.Protease

A protease (also called a peptidase, proteinase, or proteolytic enzyme) is an enzyme that catalyzes (increases reaction rate or "speeds up") proteolysis, breaking down proteins into smaller polypeptides or single amino acids, and spurring the form ...

s are enzymes that catalyze hydrolysis of a peptide bond. These proteins have evolved to recognize and bind the transition state of peptide hydrolysis reaction which is a tetrahedral intermediate. Therefore, the main protease inhibitors are tetrahedral intermediate mimics having an alcohol or a phosphate group. Examples are saquinavir

Saquinavir (SQV), sold under the brand names Invirase and Fortovase, is an antiretroviral drug used together with other medications to treat or prevent HIV/AIDS. Typically it is used with ritonavir or lopinavir/ritonavir to increase its effect. ...

, ritonavir

Ritonavir, sold under the brand name Norvir, is an antiretroviral drug used along with other medications to treat HIV/AIDS. This combination treatment is known as highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). Ritonavir is a protease inhibitor a ...

, pepstatin

Pepstatin is a potent inhibitor of aspartyl proteases. It is a hexa-peptide containing the unusual amino acid statine (Sta, (3S,4S)-4-amino-3-hydroxy-6-methylheptanoic acid), having the sequence Isovaleryl-Val-Val-Sta-Ala-Sta (Iva-Val-Val-Sta- ...

, etc.

Enzymatic activity

Stabilization of tetrahedral intermediates inside of the enzyme active site has been investigated using tetrahedral intermediate mimics. The specific binding forces involved in stabilizing the transition state have been describe crystallographycally. In the mammalian serine proteases, trypsin and chymotrypsin, two peptide NH groups of the polypeptide backbone form the so-called oxyanion hole by donating hydrogen bonds to the negatively charged oxygen atom of the tetrahedral intermediate. A simple diagram describing the interaction is shown below.

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Tetrahedral Intermediate Reactive intermediates A C