Televangelists From Missouri on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Televangelism ( tele- "distance" and "

Although television also began in the 1930s, it was not used for religious purposes until the early 1950s.

Although television also began in the 1930s, it was not used for religious purposes until the early 1950s.

The concept of using Internet videos and television to preach has spread beyond its American Evangelical roots. In Islam, the related concept of ''

The concept of using Internet videos and television to preach has spread beyond its American Evangelical roots. In Islam, the related concept of ''

evangelism

In Christianity, evangelism (or witnessing) is the act of preaching the gospel with the intention of sharing the message and teachings of Jesus Christ.

Christians who specialize in evangelism are often known as evangelists, whether they are i ...

," meaning "ministry

Ministry may refer to:

Government

* Ministry (collective executive), the complete body of government ministers under the leadership of a prime minister

* Ministry (government department), a department of a government

Religion

* Christian ...

," sometimes called teleministry) is the use of media, specifically radio and television, to communicate Christianity. Televangelists are ministers

Minister may refer to:

* Minister (Christianity), a Christian cleric

** Minister (Catholic Church)

* Minister (government), a member of government who heads a ministry (government department)

** Minister without portfolio, a member of government w ...

, whether official or self-proclaimed, who devote a large portion of their ministry to television broadcast

Broadcasting is the distribution of audio or video content to a dispersed audience via any electronic mass communications medium, but typically one using the electromagnetic spectrum ( radio waves), in a one-to-many model. Broadcasting began ...

ing. Some televangelists are also regular pastors or ministers in their own places of worship (often a megachurch), but the majority of their followers come from TV and radio audiences. Others do not have a conventional congregation, and work primarily through television. The term is also used derisively by critics as an insinuation of aggrandizement by such ministers.

Televangelism began as a uniquely American phenomenon, resulting from a largely deregulated media where access to television networks and cable TV

Cable television is a system of delivering television programming to consumers via radio frequency (RF) signals transmitted through coaxial cables, or in more recent systems, light pulses through fibre-optic cables. This contrasts with broadc ...

is open to virtually anyone who can afford it, combined with a large Christian population that is able to provide the necessary funding. It became especially popular among Evangelical Protestant audiences, whether independent or organized around Christian denominations. However, the increasing globalisation of broadcasting has enabled some American televangelists to reach a wider audience through international broadcast networks, including some that are specifically Christian in nature.

Some countries have a more regulated media with either general restrictions on access or specific rules regarding religious broadcasting. In such countries, religious programming is typically produced by TV companies (sometimes as a regulatory or public service requirement) rather than private interest groups.

Terminology

The word ''televangelism'' is a portmanteau of television andevangelism

In Christianity, evangelism (or witnessing) is the act of preaching the gospel with the intention of sharing the message and teachings of Jesus Christ.

Christians who specialize in evangelism are often known as evangelists, whether they are i ...

and it was coined in 1958 as the title of a television miniseries by the Southern Baptist Convention

The Southern Baptist Convention (SBC) is a Christian denomination based in the United States. It is the world's largest Baptist denomination, and the largest Protestant and second-largest Christian denomination in the United States. The wor ...

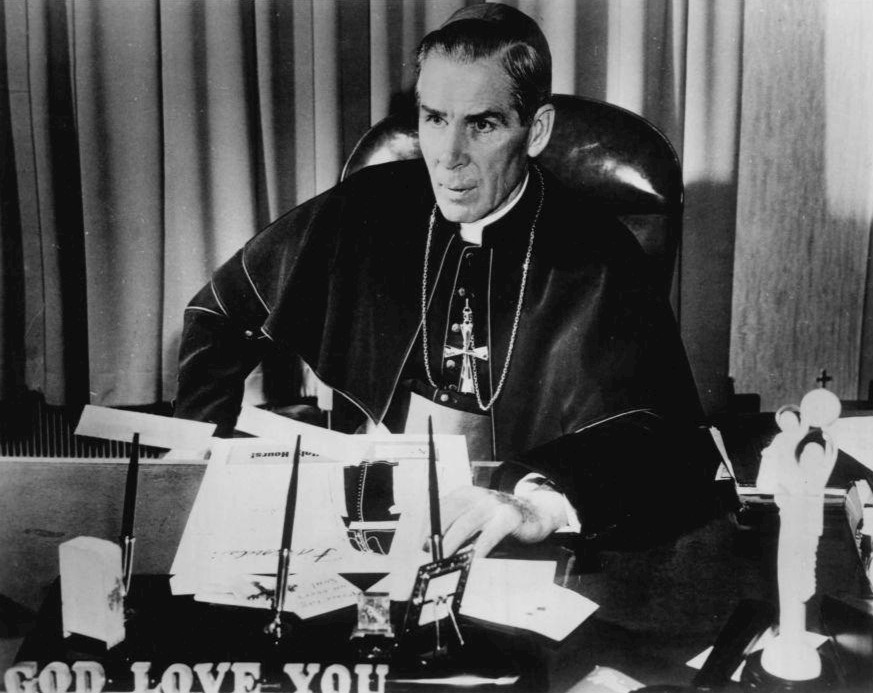

. Jeffrey K. Hadden and Charles E. Swann have been credited with popularising the word in their 1981 survey ''Prime Time Preachers: The Rising Power of Televangelism''. However, the term ''televangelist'' was employed by '' Time'' magazine already in 1952, when telegenic Roman Catholic Bishop Fulton Sheen was referred to as the "first televangelist".

History

Radio

Christianity has always emphasized preaching the gospel to the whole world, taking as inspiration the Great Commission. Historically, this was achieved by sendingmissionaries

A missionary is a member of a religious group which is sent into an area in order to promote its faith or provide services to people, such as education, literacy, social justice, health care, and economic development.Thomas Hale 'On Being a Mi ...

, beginning with the Dispersion of the Apostles, and later, after the invention of the printing press, included the distribution of Bibles and religious tracts. Some Christians realized that the rapid uptake of radio beginning in the 1920s provided a powerful new tool for this task, and they were amongst the first producers of radio programming. Radio broadcasts were seen as a complementary activity to traditional missionaries, enabling vast numbers to be reached at relatively low cost, but also enabling Christianity to be preached in countries where this was illegal and missionaries were banned. The aim of Christian radio was to both convert people to Christianity and to provide teaching and support to believers. These activities continue today, particularly in the developing world. Shortwave

Shortwave radio is radio transmission using shortwave (SW) radio frequencies. There is no official definition of the band, but the range always includes all of the high frequency band (HF), which extends from 3 to 30 MHz (100 to 10 me ...

radio stations with a Christian format broadcast worldwide, such as HCJB in Quito

Quito (; qu, Kitu), formally San Francisco de Quito, is the capital and largest city of Ecuador, with an estimated population of 2.8 million in its urban area. It is also the capital of the province of Pichincha. Quito is located in a valley o ...

, Ecuador, Family Radio

Family (from la, familia) is a group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or affinity (by marriage or other relationship). The purpose of the family is to maintain the well-being of its members and of society. Idea ...

's WYFR

WYFR was a shortwave radio station located in Okeechobee, Florida, United States. The station was owned by Family Stations, Inc., as part of the Family Radio network, and used to broadcast traditional Christian radio programming to internation ...

, and the Bible Broadcasting Network (BBN), among others.

One of the first ministers to use radio extensively was S. Parkes Cadman

Samuel Parkes Cadman (December 18, 1864 – July 12, 1936) was an English-born American liberal Protestant clergyman, newspaper writer, and pioneer Christian radio broadcaster of the 1920s and 1930s. He was an early advocate of ecumenism and an ou ...

, beginning in 1923. In 1923, Calvary Baptist Church

Calvary ( la, Calvariae or ) or Golgotha ( grc-gre, Γολγοθᾶ, ''Golgothâ'') was a site immediately outside Jerusalem's walls where Jesus was said to have been crucified according to the canonical Gospels. Since at least the early mediev ...

in New York City was the first church to operate its own radio station."Tell It From Calvary" is a radio show that the church still produces weekly; it's heard on WMCA AM570. By 1928, Cadman had a weekly Sunday afternoon radio broadcast on the NBC radio network, his powerful oratory reaching a nationwide audience of five million persons.

Aimee Semple McPherson

Aimee Elizabeth Semple McPherson (née Kennedy; October 9, 1890 – September 27, 1944), also known as Sister Aimee or Sister, was a Canadian Pentecostalism, Pentecostal Evangelism, evangelist and media celebrity in the 1920s and 1930s,Ob ...

was another pioneering tent-revivalist who soon turned to radio to reach a larger audience. Radio eventually gave her nationwide notoriety in the 1920s and 1930s and she even built one of the earliest Pentecostal megachurches.

In the U.S., the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

of the 1930s saw a resurgence of revival-tent preaching

A sermon is a religious discourse or oration by a preacher, usually a member of clergy. Sermons address a scriptural, theological, or moral topic, usually expounding on a type of belief, law, or behavior within both past and present contexts. El ...

in the Midwest

The Midwestern United States, also referred to as the Midwest or the American Midwest, is one of four Census Bureau Region, census regions of the United States Census Bureau (also known as "Region 2"). It occupies the northern central part of ...

and South

South is one of the cardinal directions or Points of the compass, compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both east and west.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Pro ...

, as itinerant traveling preachers drove from town to town, living off donations. Several preachers began radio shows as a result of their popularity.

In the 1930s, a famous radio evangelist of the period was Roman Catholic priest Father Charles Coughlin, whose strongly anti-Communist

Anti-communism is Political movement, political and Ideology, ideological opposition to communism. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in the Russian Empire, and it reached global dimensions during the Cold War, w ...

and antisemitic

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

radio programs reached millions of listeners. Other early Christian radio programs broadcast nationwide in the U.S. beginning in the 1920s–1930s include (years of radio broadcast shown): Bob Jones, Sr.

Robert Reynolds Jones Sr. (October 30, 1883 – January 16, 1968) was an American evangelist, pioneer religious broadcaster, and the founder and first president of Bob Jones University.

Early years

Bob Jones was the eleventh of twelve child ...

(1927–1962), Ralph W. Sockman

Ralph Washington Sockman (October 1, 1889 – August 29, 1970) was the senior pastor of Christ Church (United Methodist) in New York City, United States. He gained considerable prominence in the U.S. as the featured speaker on the weekly NBC ...

(1928–1962), G. E. Lowman

Guerdon Elmer Lowman, more familiarly G. E. Lowman (November 16, 1897 – January 18, 1965) was an American Christian clergyman and a pioneering international radio evangelist beginning in 1930, following a successful business career ...

(1930–1965), '' Music and the Spoken Word'' (1929–present), ''The Lutheran Hour

''The Lutheran Hour'' is a U.S.-based Christian radio program produced by Lutheran Hour Ministries. The weekly broadcast began on October 2, 1930, as an outreach ministry of the Lutheran Laymen's League, part of the Lutheran Church–Missouri S ...

'' (1930–present), and Charles E. Fuller Charles Fuller (1939–2022) was an American playwright and writer.

Charles Fuller may also refer to:

*Charles Fuller (footballer) (1919–2004), English footballer

*Charles E. Fuller (Baptist minister) (1887–1968), American Christian clergyman ...

(1937–1968). ''Time'' magazine reported in 1946 that Rev. Ralph Sockman's ''National Radio Pulpit'' on NBC received 4,000 letters weekly and Roman Catholic archbishop Fulton J. Sheen received between 3,000 and 6,000 letters weekly. The total radio audience for radio ministers in the U.S. that year was estimated to be 10 million listeners.

An association of American Evangelical Protestant religious broadcasters, the National Religious Broadcasters, was founded in 1944.

Television

Although television also began in the 1930s, it was not used for religious purposes until the early 1950s.

Although television also began in the 1930s, it was not used for religious purposes until the early 1950s. Jack Wyrtzen

John Von Casper "Jack" Wyrtzen (22 April 1913 – 17 April 1996) was an American youth evangelist and founder of Word of Life ministries, which operates Christian camps, conference centers and Bible institutes.

Wyrtzen produced the ''Word o ...

and Percy Crawford switched to TV broadcasting in the Spring of 1949. Another television preacher of note was Fulton J. Sheen, who successfully switched to television in 1951 after two decades of popular radio broadcasts and whom ''Time'' called "the first 'televangelist'". Sheen would win numerous Emmy Awards

The Emmy Awards, or Emmys, are an extensive range of awards for artistic and technical merit for the American and international television industry. A number of annual Emmy Award ceremonies are held throughout the calendar year, each with the ...

for his program that ran from the early 1950s, until the late 1960s.

After years of radio broadcasting in 1952 Rex Humbard became the first to have a weekly church service broadcast on television. By 1980 the Rex Humbard programs spanned the globe across 695 stations in 91 languages and to date the largest coverage of any evangelistic program. Oral Roberts's broadcast by 1957 reached 80% of the possible television audience through 135 of the possible 500 stations. In Uruguay, Channel 4 airs the Roman Catholic Church mass since 1961.

Christian Broadcasting Network, the first Christian channel, was founded in 1961, by Baptist Pastor Pat Robertson. Its show '' The 700 Club'', is one of the oldest on the American television scene and was broadcast in 39 languages in 138 countries in 2016.

The 1960s and early 1970s saw television replace radio as the primary home entertainment medium, but also corresponded with a further rise in Evangelical Christianity, particularly through the international television and radio ministry of Billy Graham. Many well-known televangelists began during this period, most notably Oral Roberts, Jimmy Swaggart

Jimmy Lee Swaggart (; born March 15, 1935) is an American Pentecostalism, Pentecostal televangelism, televangelist, southern gospel, gospel music recording artist, pianist, and Christian author.

His television ministry, which began in 1971, an ...

, Jim and Tammy Faye Bakker, Jerry Falwell

Jerry Laymon Falwell Sr. (August 11, 1933 – May 15, 2007) was an American Baptist pastor, televangelism, televangelist, and conservatism in the United States, conservative activist. He was the founding pastor of the Thomas Road Baptist Church, ...

, and Pat Robertson. Most developed their own media networks, news exposure, and political influence. In the 21st century, some televised church services continue to attract large audiences. In the US, there are Joel Osteen, Joyce Meyer and T. D. Jakes

Thomas Dexter Jakes (born June 9, 1957), known as T. D. Jakes, is an American bishop, author and filmmaker. He is the bishop of The Potter's House, a non-denominational American megachurch. Jakes's church services and Evangelistic sermons are ...

. In Nigeria, there are Enoch Adeboye and Chris Oyakhilome.

Controversies and criticism

Televangelists frequently draw criticism from other Christian ministers. For example, preacherJohn MacArthur John MacArthur or Macarthur may refer to:

*J. Roderick MacArthur (1920–1984), American businessman

*John MacArthur (American pastor) (born 1939), American evangelical minister, televangelist, and author

* John Macarthur (priest), 20th-century pro ...

published a number of articles in December 2009 that were highly critical of some televangelists.

Similarly, Ole Anthony

Ole Edward Anthony (October 3, 1938April 16, 2021) was an American minister, religious investigator and satirist. Anthony was the editor of '' The Wittenburg Door'', a magazine of Christian satire. He was head of the Trinity Foundation, and in th ...

wrote very critically of televangelists in 1994.

A proportion of their methods and theology are held by some to be conflicting with Christian doctrine taught in long existing traditionalist congregations. Many televangelists are featured by "discernment ministries" run by other Christians that are concerned about what they perceive as departures from sound Christian doctrine.

* Many televangelists exist outside the structures of Christian denominations, meaning that they are not accountable to anyone.

* The financial practices of many televangelists are unclear. A 2003 survey by the ''St. Louis Post-Dispatch

The ''St. Louis Post-Dispatch'' is a major regional newspaper based in St. Louis, Missouri, serving the St. Louis metropolitan area. It is the largest daily newspaper in the metropolitan area by circulation, surpassing the ''Belleville News-Dem ...

'' indicated that only one out of the 17 televangelists researched were members of the Evangelical Council for Financial Accountability.

* The prosperity gospel taught by many televangelists promises material, financial, physical, and spiritual success to believers, which can run counter to several aspects of Christian teaching that warn of suffering for following Christ and recommend surrendering one's material possessions ''(see: Jesus and the rich young man

Jesus and the rich young man (also called Jesus and the rich ruler) is an episode in the life of Jesus recounted in the Gospel of Matthew , the Gospel of Mark and the Gospel of Luke in the New Testament. It deals with eternal life and the worl ...

)''.

* Some televangelists have significant personal wealth and own large properties, luxury cars, and various transportation vehicles such as private aircraft or ministry aircraft. This is seen by critics to be contradictory to traditional Christian thinking.

* Televangelism requires substantial amounts of money to produce programs and purchase airtime on cable and satellite networks. Televangelists devote time to fundraising activities. Products such as books, CDs, DVDs, and trinkets are promoted to viewers.

* Televangelists claim to be reaching millions of people worldwide with the gospel and producing numerous converts to Christianity. However, such claims are difficult to verify independently and are often disputed.

* Several televangelists are very active in the national or international political arena (e.g., Pat Robertson, Jerry Falwell

Jerry Laymon Falwell Sr. (August 11, 1933 – May 15, 2007) was an American Baptist pastor, televangelism, televangelist, and conservatism in the United States, conservative activist. He was the founding pastor of the Thomas Road Baptist Church, ...

, Jimmy Swaggart

Jimmy Lee Swaggart (; born March 15, 1935) is an American Pentecostalism, Pentecostal televangelism, televangelist, southern gospel, gospel music recording artist, pianist, and Christian author.

His television ministry, which began in 1971, an ...

, John Hagee), and often espouse conservative politics on their programs. Such televangelists may occasionally arouse controversy by making remarks deemed offensive on their programs or elsewhere, or by endorsing partisan political candidates on donor-paid airtime, which runs afoul of the Johnson Amendment's ban on tax-exempt organizations supporting or opposing candidates for political office.

Senate probe

In 2007,Senator

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

Chuck Grassley opened a probe into the finances of six televangelists who preach a " prosperity gospel". The probe investigated reports of lavish lifestyles by televangelists including fleets of Rolls-Royces, palatial mansions, private jets, and other expensive items purportedly paid for by television viewers who donate due to the ministries' encouragement of offerings. The six that were investigated are:

* Kenneth and Gloria Copeland of Kenneth Copeland Ministries of Newark, Texas;

* Creflo Dollar and Taffi Dollar of World Changers Church International and Creflo Dollar Ministries of College Park, Georgia;

* Benny Hinn of World Healing Center Church Inc. and Benny Hinn Ministries of Grapevine, Texas;

*Eddie L. Long

Eddie Lee Long (May 12, 1953 – January 15, 2017) was an American pastor who served as the senior pastor of New Birth Missionary Baptist Church, a megachurch in unincorporated DeKalb County, Georgia, from 1987 until his death in 2017.

When Lon ...

of New Birth Missionary Baptist Church and Bishop Eddie Long Ministries of Lithonia, Georgia; "DocuSeries – Sex Scandals and Religion" did a 2011 investigative episode on his alleged sexual misconduct

* Joyce Meyer and David Meyer of Joyce Meyer Ministries of Fenton, Missouri and

*Randy White and ex-wife Paula White of the Without Walls International Church and Paula White Ministries of Tampa.

On January 6, 2011 Grassley released his review of the six ministries response to his inquiry. He called for a further congressional review of tax-exemption laws for religious groups.

In other religions

Islam

dawah

Dawah ( ar, دعوة, lit=invitation, ) is the act of inviting or calling people to embrace Islam. The plural is ''da‘wāt'' (دَعْوات) or ''da‘awāt'' (دَعَوات).

Etymology

The English term ''Dawah'' derives from the Arabic ...

'' has also given rise to similar figures who are often described as "Islamic televangelists". Examples include Moez Masoud, Zakir Naik

Zakir Abdul Karim Naik (born 18 October 1965) is an Indian Islamic televangelist and public orator who focuses on comparative religion. He is the founder and president of the Islamic Research Foundation (IRF) and the Peace TV Network.

In 20 ...

and Amr Khaled

Amr Mohamed Helmi Khaled ( ar, عمرو محمد حلمي خالد; born: 5 September 1967) is an Egyptian Muslim activist and television preacher. ''The New York Times Magazine'', in reference to Khaled's popularity in English-speaking coun ...

, amongst others. These figures may build on the longstanding ''da'i

A da'i ( ar, داعي, dāʿī, inviter, caller, ) is generally someone who engages in Dawah, the act of inviting people to Islam.

See also

* Dawah

* Da'i al-Mutlaq, "the absolute (unrestricted) missionary" (Arabic: الداعي المطلق)

* ...

'' tradition but also draw inspiration from Christian televangelists. Similarly to Christian televangelists, critics have argued that some Islamic televangelists may be too political, especially those pandering to fundamental Islamism

Islamism (also often called political Islam or Islamic fundamentalism) is a political ideology which posits that modern states and regions should be reconstituted in constitutional, economic and judicial terms, in accordance with what is ...

including the far-right

Far-right politics, also referred to as the extreme right or right-wing extremism, are political beliefs and actions further to the right of the left–right political spectrum than the standard political right, particularly in terms of being ...

. Critics also claim that many will make significant amounts of money from their work and therefore may not be motivated by spiritual or charitable causes.

Examples of well-known Islamic televangelist TV channels include Muslim Television Ahmadiyya

MTA International (or MTA), is a globally-broadcasting, nonprofit satellite television network and a division of Al-Shirkatul Islamiyyah which was established in 1992 and launched the world's first Islamic TV channel to broadcast globally. It co ...

, Islam Channel, ARY Qtv

ARY QTV, formerly known as Quran Television (QTV), is a Pakistani television channel with a Sunni Islam belief, that produces programs mainly having focus on the Ahlesunnat wal Jamaat. QTV is part of the ARY Digital Network of Pakistan.

The c ...

and Peace TV. Some of these channels, but not all, have come under scrutiny from national television or communications regulators such as Ofcom

The Office of Communications, commonly known as Ofcom, is the government-approved regulatory and competition authority for the broadcasting, telecommunications and postal industries of the United Kingdom.

Ofcom has wide-ranging powers acros ...

in the UK and the CRTC in Canada, with Ofcom having censured both Islam Channel and Peace TV in the past for biased coverage of political events, incitement to illegal acts including marital rape

Marital rape or spousal rape is the act of sexual intercourse with one's spouse without the spouse's consent. The lack of consent is the essential element and need not involve physical violence. Marital rape is considered a form of domestic vi ...

, and homophobia

Homophobia encompasses a range of negative attitude (psychology), attitudes and feelings toward homosexuality or people who are identified or perceived as being lesbian, gay or bisexual. It has been defined as contempt, prejudice, aversion, h ...

.

Hinduism

Hindu religious leaders and preachers have also utilised practises inspired by Christian televangelism, with this becoming increasingly popular in recent times. The Hare Krishna movement has a strong proselytizing tradition which sometimes extends into the internet and television spheres.See also

*List of television evangelists

This is a list of notable television evangelists. While a global list, most are from the United States.

Brazil

* Sônia Hernandes, Igreja Renascer em Cristo

* Edir Macedo, Universal Church of the Kingdom of God

* Silas Malafaia, Assem ...

* List of televangelists in Brazil

* ''McDonaldisation, Masala McGospel and Om Economics

''McDonaldisation, Masala McGospel and Om Economics'' is a book on the phenomenon of Christian televangelism in early 21st century urban India. The book was written in 2010 by Jonathan D. James of Edith Cowan University in Australia.

Overview

T ...

'', study of televangelism in India

* National Religious Broadcasters

* Our Lady of Perpetual Exemption

Our Lady of Perpetual Exemption was a legally recognized church in the United States, established by comedian and satirist John Oliver. Its purpose was to expose and ridicule televangelists such as Robert Tilton and Creflo Dollar who preach the ...

* Parodies of televangelism

A parody, also known as a spoof, a satire, a send-up, a take-off, a lampoon, a play on (something), or a caricature, is a creative work designed to imitate, comment on, and/or mock its subject by means of satiric or ironic imitation. Often its subj ...

* Prosperity theology

* Televangelist Peter Popoff exposed by James Randi

References

Further reading

* {{History of Christianity Evangelical Christian missions Evangelism History of Christianity in the United States Religious mass media in the United States 1950s neologisms