Tarebia Granifera on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Tarebia granifera'',

A detailed account of the anatomy of ''Tarebia granifera'' was given by

A detailed account of the anatomy of ''Tarebia granifera'' was given by

71

116. together with notes on its biology and bionomics. A dissection guide was provided by Malek (1962).Malek E. A. (1962). ''Laboratory Guide and Notes for Medical Malacology''. 1–154. Burgess Publishing Company, Minneapolis. The maximum height of adult shells of this species from South Africa is from 18.5 mm to 25.1 mm, while in Puerto Rico they can reach up to 35 mm. Two color forms of ''Tarebia granifera'' exist, one has a pale brown

Last modified 3 August 2005, accessed 27 December 2007, Internet Archive

List of non-marine molluscs of Taiwan, Taiwan,Chen K-J. (2003). "A preliminary study on the reproductive ecology of the freshwater snail ''Tarebia granifera'' (Lamarck, 1822) (Prosobranchia: Thiaridae) in Jinlun River, South Eastern Taiwan". MSc thesis, National Sun Yat Sen University, Taiwan. 56 pp.

PDF

PDF

Florida, Texas and Revision Date 4 February 2009.

*

common name

In biology, a common name of a taxon or organism (also known as a vernacular name, English name, colloquial name, country name, popular name, or farmer's name) is a name that is based on the normal language of everyday life; and is often contrast ...

(in the aquarium industry) the quilted melania, is a species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate s ...

of freshwater snail

Freshwater snails are gastropod mollusks which live in fresh water. There are many different families. They are found throughout the world in various habitats, ranging from ephemeral pools to the largest lakes, and from small seeps and springs ...

with an operculum, an aquatic gastropod

The gastropods (), commonly known as snails and slugs, belong to a large taxonomic class of invertebrates within the phylum Mollusca called Gastropoda ().

This class comprises snails and slugs from saltwater, from freshwater, and from land. T ...

mollusk

Mollusca is the second-largest phylum of invertebrate animals after the Arthropoda, the members of which are known as molluscs or mollusks (). Around 85,000 extant species of molluscs are recognized. The number of fossil species is e ...

in the family Thiaridae

Thiaridae, common name thiarids or trumpet snails, is a family of tropical freshwater snails with an operculum, aquatic gastropod mollusks in the superfamily Cerithioidea. MolluscaBase eds. (2021). MolluscaBase. Thiaridae Gill, 1871 (1823). A ...

. MolluscaBase eds. (2020). MolluscaBase. Tarebia granifera (Lamarck, 1816). Accessed through: World Register of Marine Species at: http://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=397189 on 2020-12-02

This snail is native to south-eastern Asia, but it has become established as an invasive species

An invasive species otherwise known as an alien is an introduced organism that becomes overpopulated and harms its new environment. Although most introduced species are neutral or beneficial with respect to other species, invasive species ad ...

in numerous other areas.

Subspecies

Subspecies of ''Tarebia granifera'' include: * ''Tarebia granifera granifera'' (Lamarck, 1822) * ''Tarebia granifera mauiensis'' Brot, 1877Description

R. Tucker Abbott

Robert Tucker Abbott (September 28, 1919 – November 3, 1995) was an American conchologist (seashells) and malacologist (molluscs). He was the author of more than 30 books on malacology, which have been translated into many languages.

Abbot ...

in 1952 Tucker Abbott R. (1952). "A study of an intermediate snail host (''Thiara granifera'') of the Oriental lung fluke (''Paragonimus'')". ''Proceedings of the United States National Museum

The Smithsonian Contributions and Studies Series is a collection of serial periodical publications produced by the Smithsonian Institution, detailing advances in various scientific and societal fields to which the Smithsonian Institution has made c ...

'' 10271

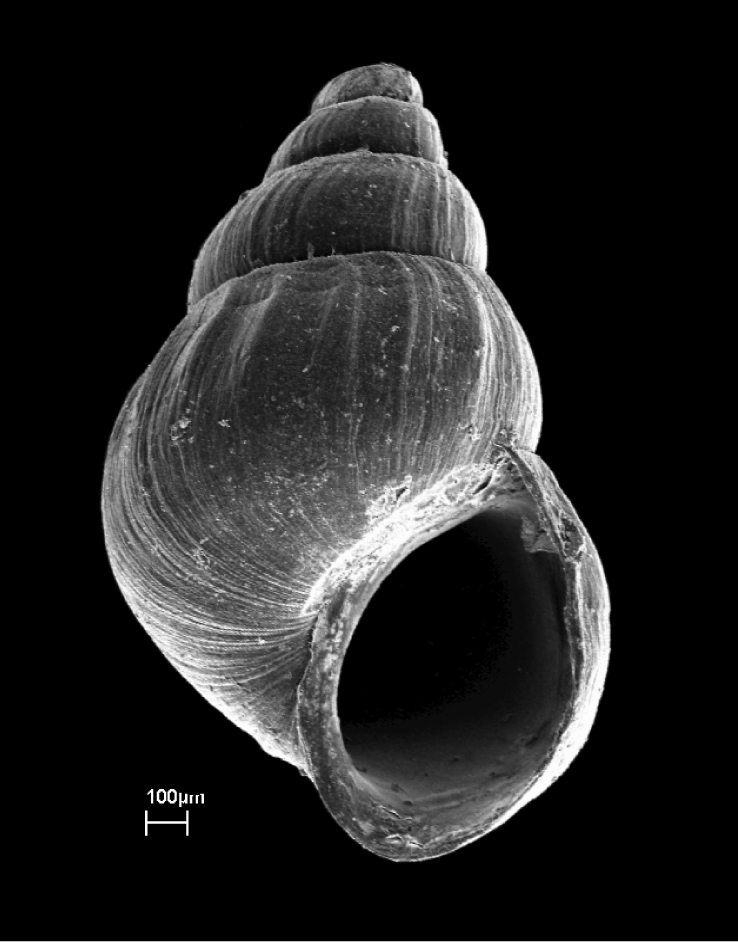

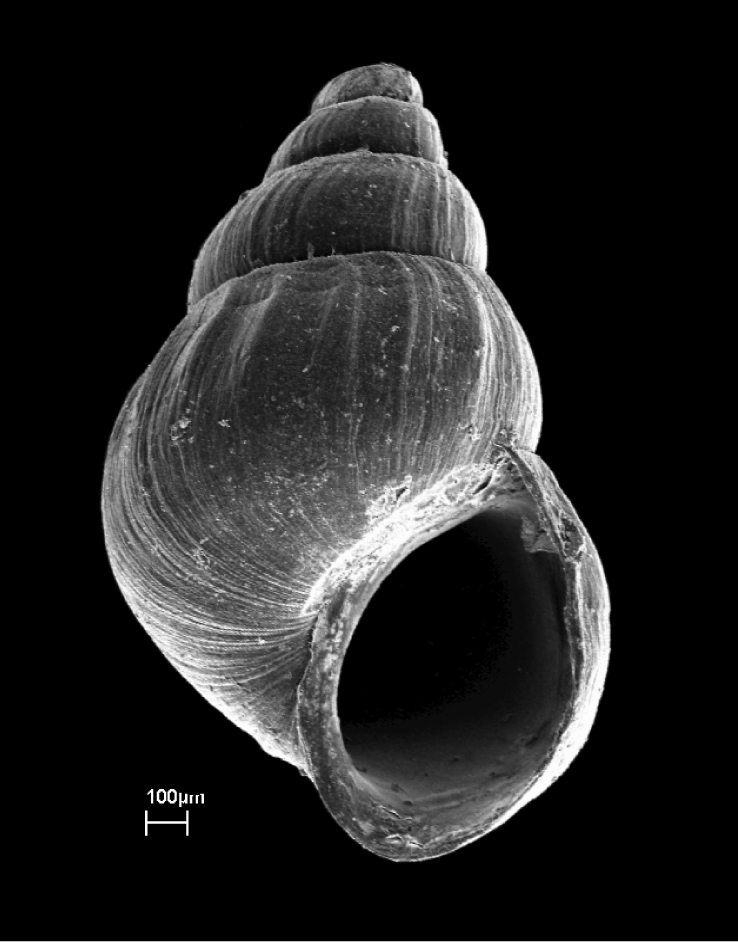

116. together with notes on its biology and bionomics. A dissection guide was provided by Malek (1962).Malek E. A. (1962). ''Laboratory Guide and Notes for Medical Malacology''. 1–154. Burgess Publishing Company, Minneapolis. The maximum height of adult shells of this species from South Africa is from 18.5 mm to 25.1 mm, while in Puerto Rico they can reach up to 35 mm. Two color forms of ''Tarebia granifera'' exist, one has a pale brown

body whorl

The body whorl is part of the morphology of the shell in those gastropod mollusks that possess a coiled shell. The term is also sometimes used in a similar way to describe the shell of a cephalopod mollusk.

In gastropods

In gastropods, the b ...

and a dark spire

A spire is a tall, slender, pointed structure on top of a roof of a building or tower, especially at the summit of church steeples. A spire may have a square, circular, or polygonal plan, with a roughly conical or pyramidal shape. Spires are ...

(see photo on the right) and in the other the shell is entirely dark brown to almost black (see photo on the left). Intermediate forms exist.

Distribution

Indigenous distribution

The indigenous distribution of this species includes the general area of these countries:India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

, Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

, Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

, Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; haw, Hawaii or ) is a state in the Western United States, located in the Pacific Ocean about from the U.S. mainland. It is the only U.S. state outside North America, the only state that is an archipelago, and the only stat ...

, southern Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

, Society Islands

The Society Islands (french: Îles de la Société, officially ''Archipel de la Société;'' ty, Tōtaiete mā) are an archipelago located in the South Pacific Ocean. Politically, they are part of French Polynesia, an overseas country of the F ...

,''Tarebia granifera'' (Lamarck, 1822)Last modified 3 August 2005, accessed 27 December 2007, Internet Archive

List of non-marine molluscs of Taiwan, Taiwan,Chen K-J. (2003). "A preliminary study on the reproductive ecology of the freshwater snail ''Tarebia granifera'' (Lamarck, 1822) (Prosobranchia: Thiaridae) in Jinlun River, South Eastern Taiwan". MSc thesis, National Sun Yat Sen University, Taiwan. 56 pp.

Hong Kong

Hong Kong ( (US) or (UK); , ), officially the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China ( abbr. Hong Kong SAR or HKSAR), is a city and special administrative region of China on the eastern Pearl River Delt ...

, Thailand

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 million. The country is bo ...

.Ukong S., Krailas D., Dangprasert T. & Channgarm P. (2007). "Studies on the morphology of cercariae obtained from freshwater snails at Erawan waterfall, Erawan national park

Erawan National Park ( th, อุทยานแห่งชาติเอราวัณ) is a 343,735 rai ~ park in western Thailand in the Tenasserim Hills of Kanchanaburi Province, Amphoe Si Sawat in tambon Tha Kradan. Founded on August 14 ...

, Thailand". ''The Southeast Asian Journal of Tropical Medicine and Public Health

''The'' () is a grammatical article in English, denoting persons or things already mentioned, under discussion, implied or otherwise presumed familiar to listeners, readers, or speakers. It is the definite article in English. ''The'' is the ...

'' 38(2): 302–312Nonidigenous distribution

''Tarebia granifera'' has become invasive on at least three continents: North and South America and Africa. Initial introductions were presumably via the aquarium trade. Americas: * This species occurs in several southern states of the U.S.:Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico (; abbreviated PR; tnq, Boriken, ''Borinquen''), officially the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico ( es, link=yes, Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico, lit=Free Associated State of Puerto Rico), is a Caribbean island and Unincorporated ...

,Chaniotis B. N., Butler J. M., Ferguson F. F. & Jobin W. R. (1980). "Bionomics of ''Tarebia granifera'' (Gastropoda: Thiaridae) in Puerto Rico, an Asian vector of ''Paragonimiasis westermani''". ''Caribbean Journal of Science

The ''Caribbean Journal of Science'' is a triannual peer-reviewed open-access scientific journal publishing articles, research notes, and book reviews related to science in the Caribbean, with an emphasis on botany, zoology, ecology, conservation b ...

'' 16: 81–89Florida, Texas and

Idaho

Idaho ( ) is a state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. To the north, it shares a small portion of the Canada–United States border with the province of British Columbia. It borders the states of Montana and Wyom ...

United States Geological Survey

The United States Geological Survey (USGS), formerly simply known as the Geological Survey, is a scientific agency of the United States government. The scientists of the USGS study the landscape of the United States, its natural resources, ...

. (2008). ''Tarebia granifera''. USGS Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Database, Gainesville, FL. Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; haw, Hawaii or ) is a state in the Western United States, located in the Pacific Ocean about from the U.S. mainland. It is the only U.S. state outside North America, the only state that is an archipelago, and the only stat ...

* Many Caribbean islands:

** Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

– along with ''Physella acuta

''Physella acuta'' is a species of small, left-handed or sinistral, air-breathing freshwater snail, an aquatic gastropod mollusk in the family Physidae. Common names include European physa, tadpole snail, bladder snail, and acute bladder snail. ...

'' it is the most common freshwater snail in Cuba

** The Dominican Republic

** Saint Lucia

Saint Lucia ( acf, Sent Lisi, french: Sainte-Lucie) is an island country of the West Indies in the eastern Caribbean. The island was previously called Iouanalao and later Hewanorra, names given by the native Arawaks and Caribs, two Amerindian ...

** Martinique

Martinique ( , ; gcf, label=Martinican Creole, Matinik or ; Kalinago: or ) is an island and an overseas department/region and single territorial collectivity of France. An integral part of the French Republic, Martinique is located in th ...

since 1991

* Central America: Mexico

* El Hatillo Municipality, Miranda, Venezuela

Africa:

* South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring countri ...

The ''Tarebia granifera'' was reported from South Africa (and Africa) for the first time in 1999 in northern KwaZulu-Natal

KwaZulu-Natal (, also referred to as KZN and known as "the garden province") is a province of South Africa that was created in 1994 when the Zulu bantustan of KwaZulu ("Place of the Zulu" in Zulu) and Natal Province were merged. It is locate ...

though it was probably introduced sometime prior to 1996. In the 10 years since its discovery it has spread rapidly, particularly northwards, into Mpumalanga

Mpumalanga () is a province of South Africa. The name means "East", or literally "The Place Where the Sun Rises" in the Swazi, Xhosa, Ndebele and Zulu languages. Mpumalanga lies in eastern South Africa, bordering Eswatini and Mozambique. It ...

province, the Kruger National Park

Kruger National Park is a South African National Park and one of the largest game reserves in Africa. It covers an area of in the provinces of Limpopo and Mpumalanga in northeastern South Africa, and extends from north to south and from ea ...

and Eswatini

Eswatini ( ; ss, eSwatini ), officially the Kingdom of Eswatini and formerly named Swaziland ( ; officially renamed in 2018), is a landlocked country in Southern Africa. It is bordered by Mozambique to its northeast and South Africa to its no ...

.

This spread will doubtless continue into northern South Africa, Moçambique, Zimbabwe and beyond. It has not been possible to calculate the rate of dispersal.

Asia:

* Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

(non-indigenous)

Ecology

Habitat

In the South Africa, the snail has colonized different types of habitat, from rivers, lakes and irrigation canals to concrete lined reservoirs and ornamental ponds. It reaches very high densities, up to 21 000 m², and is likely to impact on the entire indigenousbenthos

Benthos (), also known as benthon, is the community of organisms that live on, in, or near the bottom of a sea, river, lake, or stream, also known as the benthic zone. The South African indigenous thiarids ''

HTMPDF

PDF

* Chaniotis B. N., Butler J. M., Ferguson F. F. & Jobin W. R. (1980). "Thermal limits, desiccation tolerance, and humidity reactions of ''Thiara'' (''Tarebia'') ''granifera mauiensis'' (Gastropoda: Thiaridae) host of the asiatic lung fluke disease". ''

PDF

* Ferguson et al. (1958)

"Potential for Biological Control of ''Australorbis Glabratus'', the Intermediate Host of Puerto Rican Schistosomiasis"

''

Thiara amarula

''Thiara amarula'' is a species of gastropod belonging to the family Thiaridae.

Description

The length of the shell attains 32 mm.

Distribution

The species is found in Malesia, coasts of Indian and Pacific Ocean.; off Queensland

)

, nickn ...

'', ''Melanoides tuberculata

The red-rimmed melania (''Melanoides tuberculata''), also known as Malayan livebearing snails or Malayan/Malaysian trumpet snails (often abbreviated to MTS) by aquarists, is a species of freshwater snail with an operculum, a parthenogenetic, a ...

'', and '' Cleopatra ferruginea'' are considered particularly vulnerable.

Most localities in South Africa (93%) lie below an altitude of 300 m above sea level where an estimated area of 39 500 km2 has been colonized. The only known localities outside this area are the Umsinduzi River in Pietermaritzburg

Pietermaritzburg (; Zulu: umGungundlovu) is the capital and second-largest city in the province of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. It was founded in 1838 and is currently governed by the Msunduzi Local Municipality. Its Zulu name umGungundlovu ...

and its confluence with the Umgeni River

The Umgeni River or Mgeni River ( zu, uMngeni) is a river in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. It rises in the "Dargle" in the KZN Midlands, and its mouth is at Durban, some distance north of Durban's natural harbour. The name is taken to mean "the r ...

which lie closer to 500 m. R. Tucker Abbott

Robert Tucker Abbott (September 28, 1919 – November 3, 1995) was an American conchologist (seashells) and malacologist (molluscs). He was the author of more than 30 books on malacology, which have been translated into many languages.

Abbot ...

(1952) noted that on Guam

Guam (; ch, Guåhan ) is an organized, unincorporated territory of the United States in the Micronesia subregion of the western Pacific Ocean. It is the westernmost point and territory of the United States (reckoned from the geographic cent ...

Island, ''Tarebia granifera'' occurred in streams and rivers at 983 m altitude but that these watercourses were consistently above 24 °C indicating that temperature may be an important determinant of distribution.

''Tarebia granifera'' also occurs in several estuaries along the KwaZulu-Natal coast. Prominent among these is the dense population (±6038 m2) found at a salinity

Salinity () is the saltiness or amount of salt dissolved in a body of water, called saline water (see also soil salinity). It is usually measured in g/L or g/kg (grams of salt per liter/kilogram of water; the latter is dimensionless and equal ...

of 9.98‰ (28.5% sea water) in Catalina Bay, Lake St Lucia, iSimangaliso Wetland Park

iSimangaliso Wetland Park (previously known as the Greater St. Lucia Wetland Park) is situated on the east coast of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, about 235 kilometres north of Durban by road. It is South Africa's third-largest protected area, ...

, KwaZulu-Natal. These records show that ''Tarebia granifera'' is able to colonize brackish

Brackish water, sometimes termed brack water, is water occurring in a natural environment that has more salinity than freshwater, but not as much as seawater. It may result from mixing seawater (salt water) and fresh water together, as in estuari ...

and moderately saline habitats and reach high densities there. From observations in Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico (; abbreviated PR; tnq, Boriken, ''Borinquen''), officially the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico ( es, link=yes, Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico, lit=Free Associated State of Puerto Rico), is a Caribbean island and Unincorporated ...

it was suggested that snails could survive temporarily saline conditions for several weeks by burying themselves in the substratum

In linguistics, a stratum (Latin for "layer") or strate is a language that influences or is influenced by another through contact. A substratum or substrate is a language that has lower power or prestige than another, while a superstratum or sup ...

, emerging when fresh water returned.

In common with other Thiaridae, ''Tarebia granifera'' is primarily a benthic

The benthic zone is the ecological region at the lowest level of a body of water such as an ocean, lake, or stream, including the sediment surface and some sub-surface layers. The name comes from ancient Greek, βένθος (bénthos), meaning "t ...

species and in South Africa has been collected on a variety of substrata in both natural and artificial waterbodies, e.g. sand, mud, rock, concrete bridge foundations and the concrete walls and bottoms of reservoirs, irrigation canals and ornamental ponds. Many of these habitats were vegetated and the associated vegetation included many types of emergent monocotyledons

Monocotyledons (), commonly referred to as monocots, (Lilianae ''sensu'' Chase & Reveal) are grass and grass-like flowering plants (angiosperms), the seeds of which typically contain only one embryonic leaf, or cotyledon. They constitute one of t ...

(e.g. ''Cyperus papyrus

''Cyperus papyrus'', better known by the common names papyrus, papyrus sedge, paper reed, Indian matting plant, or Nile grass, is a species of aquatic flowering plant belonging to the sedge family Cyperaceae. It is a tender herbaceous perenn ...

'', ''Scirpus

''Scirpus'' is a genus of grass-like species in the sedge family Cyperaceae many with the common names club-rush, wood club-rush or bulrush (see also bulrush for other plant genera so-named). They mostly inhabit wetlands and damp locations.

Taxo ...

'' sp., ''Typha

''Typha'' is a genus of about 30 species of monocotyledonous flowering plants in the family Typhaceae. These plants have a variety of common names, in British English as bulrush or reedmace, in American English as reed, cattail, or punks, in A ...

'' sp., ''Phragmites

''Phragmites'' () is a genus of four species of large perennial reed grasses found in wetlands throughout temperate and tropical regions of the world.

Taxonomy

The World Checklist of Selected Plant Families, maintained by Kew Garden in London ...

'' sp.) and dicotyledons

The dicotyledons, also known as dicots (or, more rarely, dicotyls), are one of the two groups into which all the flowering plants (angiosperms) were formerly divided. The name refers to one of the typical characteristics of the group: namely, t ...

(e.g. ''Ceratophyllum demersum

''Ceratophyllum demersum'', commonly known as hornwort, rigid hornwort, coontail, or coon's tail, is a species of ''Ceratophyllum''. It is a submerged, free-floating aquatic plant, with a cosmopolitan distribution, native to all continents except ...

'', ''Potamogeton crispus

''Potamogeton crispus'', the crisp-leaved pondweed, curly pondweed, curly-leaf pondweed or curled pondweed, is a species of aquatic plant (hydrophyte) native to Eurasia but an introduced species and often a noxious weed in North America.

Descr ...

'', ''Nymphaea nouchali

''Nymphaea nouchali'', often known by its synonym ''Nymphaea stellata'', or by common names blue lotus, star lotus, red water lily, dwarf aquarium lily, blue water lily, blue star water lily or manel flower, is a water lily of genus '' Nympha ...

''). Where densities are high, ''Tarebia granifera'' may also occur on marginal, trailing vegetation and the floating Common Water Hyacinth ''Eichhornia crassipes

''Pontederia crassipes'' (formerly ''Eichhornia crassipes''), commonly known as common water hyacinth is an aquatic plant native to South America, naturalized throughout the world, and often invasive species, invasive outside its native range ...

'' as well. It favours turbulent water and tolerates current speeds up to 1.2m.s−1 and possibly greater. This habitat range is similar to that recorded for ''Tarebia granifera'' in Puerto Rico.

The major interest in ''Tarebia granifera'' outside Asia today is its invasive ability and its impact on indigenous benthic communities in colonized waterbodies. The pollution tolerance value is 3 (on scale 0–10; 0 is the best water quality, 10 is the worst water quality).Young S.-S., Yang H.-N., Huang D.-J., Liu S.-M., Huang Y.-H., Chiang C.-T. & Liu, J.-W. (2014). "Using Benthic Macroinvertebrate and Fish Communities as Bioindicators of the Tanshui River Basin Around the Greater Taipei Area – Multivariate Analysis of Spatial Variation Related to Levels of Water Pollution". ''International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health

The ''International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health'' is a peer-reviewed open access scientific journal published by MDPI. The editor-in-chief is Paul B. Tchounwou. According to the ''Journal Citation Reports'' 2020 edition, th ...

'' 11(7): 7116–7143. .

Typically half or more of these snails were buried in the sediment

Sediment is a naturally occurring material that is broken down by processes of weathering and erosion, and is subsequently transported by the action of wind, water, or ice or by the force of gravity acting on the particles. For example, sand an ...

s and were not visible from the surface. This was also noticed in aquaria where they actively buried themselves in sand. Exact proportion of population of ''Tarebia granifera'' that is buried at any time is not known. There is also not known how long can snails remain buried.

''Tarebia granifera'' will die at the temperature 7 °C in aquaria, but they do not live in water temperature under 10 °C in the wild.

Dispersal

It is probable that dispersal of ''Tarebia granifera'' from one waterbody or river catchment to another occurs passively via birds, notablywaterfowl

Anseriformes is an order of birds also known as waterfowl that comprises about 180 living species of birds in three families: Anhimidae (three species of screamers), Anseranatidae (the magpie goose), and Anatidae, the largest family, which in ...

, which eat them and void them later, perhaps in another habitat. Evidence for this comes from the finding of many small ''Tarebia granifera'' 5–7 mm in height and still containing the soft parts in unidentified bird droppings from the bank of the Mhlali River, South Africa. Even though the shell of ''Tarebia granifera'' is thick, most of these juveniles had been partially crushed with only a few still intact. Both the intact and damaged specimens could have been alive when passed and perhaps survived had they been deposited in water. None was large enough to have been reproductively mature (see below) and would have needed to survive in any new habitat for several months before reproducing.

Passive dispersal may also occur via weed on boats and boat trailers and via water pumped from one waterbody to another for industrial and irrigation purposes. In the Nseleni River juvenile ''Tarebia granifera'' were commonly found with another invasive snail, ''Pseudosuccinea columella

''Pseudosuccinea columella'' , the American ribbed fluke snail, is a species of air-breathing freshwater snail, an aquatic pulmonate gastropod mollusk in the family Lymnaeidae, the pond snails.

This snail is an intermediate host for '' Fasciola ...

'', on floating clumps of water hyacinth ''Eichhornia crassipes'' which provide a vehicle for rapid downstream dispersal.

Once established in a particular waterbody ''Tarebia granifera'' is likely to disperse actively, both up and downstream in the case of flowing systems, as far as environmental factors like current speed and food availability will allow. The snail's tolerance of turbulent, flowing water was demonstrated by Prentice (1983). who reported it migrating upstream on the Caribbean island of Saint Lucia

Saint Lucia ( acf, Sent Lisi, french: Sainte-Lucie) is an island country of the West Indies in the eastern Caribbean. The island was previously called Iouanalao and later Hewanorra, names given by the native Arawaks and Caribs, two Amerindian ...

at a rate of 100 m month−1 in streams discharging up to 50 L.s−1. In KwaZulu-Natal it has been collected in water flowing at up to 1.2 m.s−1 which is likely to exceed the current speeds of at least the lower and middle reaches of many rivers and streams in South Africa making these watercourses open to colonization.

The sole of ''Tarebia granifera'' is proportionally small when compared to other thiarids and smaller snails with their higher coefficients were less able to grip the substratum in the face of moving water and so not did disperse as effectively as larger ones.

Density

In Florida, Tucker Abbott (1952) recorded adensity

Density (volumetric mass density or specific mass) is the substance's mass per unit of volume. The symbol most often used for density is ''ρ'' (the lower case Greek letter rho), although the Latin letter ''D'' can also be used. Mathematical ...

of ''Tarebia granifera'' 4444 m−2 which falls within the range of densities measured with a Van Veen grab in a number of sites in northern KwaZulu-Natal, where densities were measured from 843.6 ±320.2 m−2 to 20764.4 ±13828.1 m−2. The site with such high density was non-flowing, devoid of rooted vegetation but it was shaded by trees (''Barringtonia racemosa

''Barringtonia racemosa'' (powder-puff tree, af, pooeierkwasboom, zu, Iboqo, Malay: ''Putat'') is a tree in the family Lecythidaceae. It is found in coastal swamp forests and on the edges of estuaries in the Indian Ocean, starting at the east ...

'') and by floating ''Eichhornia crassipes

''Pontederia crassipes'' (formerly ''Eichhornia crassipes''), commonly known as common water hyacinth is an aquatic plant native to South America, naturalized throughout the world, and often invasive species, invasive outside its native range ...

''. This between-site variability may be positively correlated to habitat heterogeneity and food availability. Despite the very high densities recorded in the Nseleni River, indigenous invertebrates were still present in the sediments including: bivalve '' Chambardia wahlbergi'', chironomid

The Chironomidae (informally known as chironomids, nonbiting midges, or lake flies) comprise a family of nematoceran flies with a global distribution. They are closely related to the Ceratopogonidae, Simuliidae, and Thaumaleidae. Many species ...

s, oligochaetes

Oligochaeta () is a subclass of animals in the phylum Annelida, which is made up of many types of aquatic and terrestrial worms, including all of the various earthworms. Specifically, oligochaetes comprise the terrestrial megadrile earthworms ...

(tubificids) and burrowing polychaetes

Polychaeta () is a paraphyletic class of generally marine annelid worms, commonly called bristle worms or polychaetes (). Each body segment has a pair of fleshy protrusions called parapodia that bear many bristles, called chaetae, which are mad ...

were also found but in very low numbers.

The low densities of ''Tarebia granifera'' reported for the Mhlatuze River, South Africa may have been influenced by nearby sand mining

Sand mining is the extraction of sand, mainly through an open pit (or sand pit) but sometimes mined from beaches and inland dunes or dredged from ocean and river beds. Sand is often used in manufacturing, for example as an abrasive or in concret ...

activities or, more likely, high flows and mobile sediments, but they nevertheless approach those recorded by Dudgeon (1980)Dudgeon D. (1980). "The effects of water level fluctuations on a gastropod community in the rocky marginal zone of Plover Cove reservoir, Hong Kong". '' International Journal of Ecological and Environmental Sciences'' 8: 195–204. for ''Tarebia granifera'' in its native Hong Kong

Hong Kong ( (US) or (UK); , ), officially the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China ( abbr. Hong Kong SAR or HKSAR), is a city and special administrative region of China on the eastern Pearl River Delt ...

(18–193 m−2).

Little is known of the long term population fluctuations of ''Tarebia granifera'' and findings seem to be contradictory. Studies in Cuba (Yong et al. (1987), Ferrer López et al. (1989), Fernández et al. (1992)) indicate that the snail lives for more than a year though maximum densities were recorded at different times of the year in different habitats. Using a catch per unit effort In fisheries and conservation biology, the catch per unit effort (CPUE) is an indirect measure of the abundance of a target species. Changes in the catch per unit effort are inferred to signify changes to the target species' true abundance. A decr ...

netting technique, Yong et al. (1987) and Ferrer López et al. (1989) found highest densities in summer when temperatures reached their maximum whereas Fernández et al. (1992) found highest densities in November (late autumn) when temperatures reached their minimum. Fernández et al. (1992) also suggested that ''Tarebia granifera'' density was positively correlated with Ca2+ concentrations and negatively with NH4 concentrations.

Recent surveys by Vázquez et al. (2010) of Pinar del Río Province

Pinar del Río is one of the provinces of Cuba. It is at the western end of the island of Cuba.

Geography

The Pinar del Río province is Cuba's westernmost province and contains one of Cuba's three main mountain ranges, the Cordillera de Guanig ...

, Cuba have reported population densities of ''Tarebia granifera'' of 85 individuals/m2, well above those of its endemic relatives (5 individuals/m2).

Feeding habits

''Tarebia granifera'' feeds on algae,diatoms

A diatom (New Latin, Neo-Latin ''diatoma''), "a cutting through, a severance", from el, διάτομος, diátomos, "cut in half, divided equally" from el, διατέμνω, diatémno, "to cut in twain". is any member of a large group com ...

and detritus

In biology, detritus () is dead particulate organic material, as distinguished from dissolved organic material. Detritus typically includes the bodies or fragments of bodies of dead organisms, and fecal material. Detritus typically hosts commun ...

.

Life cycle

''Tarebia granifera'' is bothparthenogenetic

Parthenogenesis (; from the Greek grc, παρθένος, translit=parthénos, lit=virgin, label=none + grc, γένεσις, translit=génesis, lit=creation, label=none) is a natural form of asexual reproduction in which growth and development ...

and ovoviviparous

Ovoviviparity, ovovivipary, ovivipary, or aplacental viviparity is a term used as a "bridging" form of reproduction between egg-laying oviparous and live-bearing viviparous reproduction. Ovoviviparous animals possess embryos that develop insi ...

, although males have been reported. These are characteristics which are undoubtedly key to its success as an invader. For example, no males have been found amongst hundreds dissected from KwaZulu-Natal, it is probable that a few are present. Males were found in most (6/7) populations examined in Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico (; abbreviated PR; tnq, Boriken, ''Borinquen''), officially the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico ( es, link=yes, Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico, lit=Free Associated State of Puerto Rico), is a Caribbean island and Unincorporated ...

but were generally uncommon at up to 22.7% of the population (mean 4.6%). Live sperm were present in the testes of these males but the genitalia

A sex organ (or reproductive organ) is any part of an animal or plant that is involved in sexual reproduction. The reproductive organs together constitute the reproductive system. In animals, the testis in the male, and the ovary in the female, a ...

were apparently non-functional. R. Tucker Abbott (1952) failed to find sperm in the gonads of male ''Tarebia granifera'' from Florida. Most ''Tarebia granifera'' are therefore clones

Clone or Clones or Cloning or Cloned or The Clone may refer to:

Places

* Clones, County Fermanagh

* Clones, County Monaghan, a town in Ireland

Biology

* Clone (B-cell), a lymphocyte clone, the massive presence of which may indicate a pathologi ...

of the female parent.

Embryo

An embryo is an initial stage of development of a multicellular organism. In organisms that reproduce sexually, embryonic development is the part of the life cycle that begins just after fertilization of the female egg cell by the male spe ...

s develop in a brood pouch. This pouch is a compartmentalized structure lying immediately above the oesophagus

The esophagus (American English) or oesophagus (British English; both ), non-technically known also as the food pipe or gullet, is an organ in vertebrates through which food passes, aided by peristaltic contractions, from the pharynx to the ...

and develops only after the snail has reached maturity. Its size expands as the number of embryos increases. ''Tarebia granifera'' has 1–77 embryos in its brood pouch.

Tucker Abbott (1952), Chaniotis et al. (1980) and WHO (1981)W.H.O. (1981). "Data sheet on the biological control agent ''Thiara granifera'' (Lamarck)". World Health Organization

The World Health Organization (WHO) is a specialized agency of the United Nations responsible for international public health. The WHO Constitution states its main objective as "the attainment by all peoples of the highest possible level of h ...

, Geneva, VBC/BCDS/81.17. cite the same statistic that females can give birth to one juvenile every 12 hours. Young snails emerge through a birth pore on the right side of the head. The newborn shell is <1–2 mm in height with between 1.5 and 4.8 whorls. The size of juveniles at birth is 0.7–2.1 mm. According to Chen (2003) these newborns have a high survival rate in the field.

Attainment of sexual maturity

Sexual maturity is the capability of an organism to reproduce. In humans it might be considered synonymous with adulthood, but here puberty is the name for the process of biological sexual maturation, while adulthood is based on cultural definitio ...

in ''Tarebia granifera'' is generally indicated by the size of the smallest snail observed to give birth rather than a histological assessment of the development of the gonad and associated reproductive structures. Appleton & Nadasan (2002) estimated onset of maturity at 10–12 mm shell height but unpublished data suggest a height closer to 8 mm in line with other published studies. Tucker Abbott (1952) estimated sexual maturity at between 5.5 and 8.0 mm at different stations over a short stretch of river in Florida. Chaniotis et al. (1980) gave a similar estimate of 6.0–7.0 mm from a cohort of laboratory-bred snails in Puerto Rico.

Appleton et al. (2009) extrapolated data by Yong et al. (1987),Yong M., Sanchez R., Perera G., Ferrer R. & Amador O. (1987). "Seasonal studies of two populations of ''Tarebia granifera''". '' Walkerana'' 2: 159–163. Ferrer López et al. (1989) Ferrer López J. R., Perera de Puga G. & Yong Cong M. (1989). "Estudio de la morfometría de los 4 poblaciones de ''Tarebia granifera'' en condiciones de laboratorio". '' Revista Cubana de Medicina Tropical'' 43: 26–30. and by Fernández et al. (1992) Fernández L. D., Casalis A. E., Masa A. M. & Perez M. V. (1992). "Estudio preliminar de la variación de ''Tarebia granifera'' (Lamarck), Río Hatibonico, Camagüey". '' Revista Cubana de Medicina Tropical'' 44: 66–70. and they resulted that sexual maturity is reached at an age of about five months. Reported variation in maturation period varies from 97–143 days (3.2–4.8 months) under the laboratory conditions to 6–12 months, also from laboratory data. It is difficult to relate shell size at the onset of maturity to age since the size structure of populations vary over time and from one locality to another.

Dissection of ''Tarebia granifera'' showed blastula

Blastulation is the stage in early animal embryonic development that produces the blastula. In mammalian development the blastula develops into the blastocyst with a differentiated inner cell mass and an outer trophectoderm. The blastula (from ...

stage embryos in the brood pouches of snails as small as 8 mm shell height. Small numbers of shelled embryos, including veliger

A veliger is the planktonic larva of many kinds of sea snails and freshwater snails, as well as most bivalve molluscs (clams) and tusk shells.

Description

The veliger is the characteristic larva of the gastropod, bivalve and scaphopod ...

s, were found in snails of 10–14 mm but became more plentiful in snails >14 mm and especially those >20 mm. Importantly, unshelled embryos (blastula, gastrula

Gastrulation is the stage in the early embryonic development of most animals, during which the blastula (a single-layered hollow sphere of cells), or in mammals the blastocyst is reorganized into a multilayered structure known as the gastrula. ...

and trochophore

A trochophore (; also spelled trocophore) is a type of free-swimming planktonic marine larva with several bands of cilia.

By moving their cilia rapidly, they make a water eddy, to control their movement, and to bring their food closer, to captur ...

stages) were not found in snails >16 mm and the numbers of shelled embryos themselves decreased in the largest snails, >24 mm. This suggests that differentiation of germinal cells in the ovary and their subsequent arrival in the brood pouch as blastulae is not a continuous process over a breeding season but occurs as one or more 'cohorts' or 'pulses' which stop before the birth rate of young snails reaches its maximum. So it seems that while the first birth may occur in snails as small as 8 mm, these are few and most juveniles are born to snails >14 mm. The size of the shell of the parent at peak release of juveniles is 24.0 mm.

The reproductive biology

Reproductive biology includes both sexual and asexual reproduction.

Reproductive biology includes a wide number of fields:

* Reproductive systems

* Endocrinology

* Sexual development (Puberty)

* Sexual maturity

* Reproduction

* Fertility

Human ...

of ''Tarebia granifera'' needs to be investigated in detail before its population dynamics

Population dynamics is the type of mathematics used to model and study the size and age composition of populations as dynamical systems.

History

Population dynamics has traditionally been the dominant branch of mathematical biology, which has ...

can be properly interpreted from quantitative sampling.

Parasites

''Tarebia granifera'' serves as the firstintermediate host

In biology and medicine, a host is a larger organism that harbours a smaller organism; whether a parasitic, a mutualistic, or a commensalist ''guest'' (symbiont). The guest is typically provided with nourishment and shelter. Examples include a ...

for a variety of trematodes

Trematoda is a class of flatworms known as flukes. They are obligate internal parasites with a complex life cycle requiring at least two hosts. The intermediate host, in which asexual reproduction occurs, is usually a snail. The definitive host ...

in its native south east Asia. Amongst these are several species of the family Heterophyidae

Heterophyidae is a family of intestinal trematodes in the order Plagiorchiida.

Description: " Tegument covered by spines. Oral sucker not armed or armed by cyrcumoral spines. Pharynx presented. Genital synus presented. Ventral and genital suc ...

some of which have been reported as opportunistic infections in people, and another, ''Centrocestus formosanus

''Centrocestus formosanus'' is a trematode parasite of Asian origin that has found its way into North American streams and rivers. It not only affects the fountain darter but many species of commercially important fishes. It is also capable of i ...

'' (Nishigori, 1924), is an important gill parasite of fish. ''Tarebia granifera'' also serves as intermediate host for the philopthalmid eyefluke '' Philopthalmus gralli'' Mathis & Ledger, 1910 which has recently (2005) been reported affecting ostrich

Ostriches are large flightless birds of the genus ''Struthio'' in the order Struthioniformes, part of the infra-class Palaeognathae, a diverse group of flightless birds also known as ratites that includes the emus, rheas, and kiwis. There are ...

es ''Struthio camelus

The common ostrich (''Struthio camelus''), or simply ostrich, is a species of flightless bird native to certain large areas of Africa and is the largest living bird species. It is one of two extant species of ostriches, the only living members o ...

'' on farms in Zimbabwe. The snail host implicated in this outbreak was ''Melanoides tuberculata'' but the rapid spread and high population densities achieved by ''Tarebia granifera'', which appears to be replacing ''Melanoides tuberculata'' in South Africa, may exacerbate the problem in the future.

For many years ''Tarebia granifera'' was believed to be an intermediate host for the Asian lungfluke ''Paragonimus westermani

''Paragonimus westermani'' (Japanese lung fluke or oriental lung fluke) is the most common species of lung fluke that infects humans, causing paragonimiasis. Human infections are most common in eastern Asia and in South America. Paragonimiasis m ...

'' (Kerbert, 1878), but Michelson showed in 1992 that this was erroneous.Michelson E. (1992). "''Thiara granifera'': a victim of authoritarianism?" ''Malacological Review

Malacology is the branch of invertebrate zoology that deals with the study of the Mollusca (mollusks or molluscs), the second-largest phylum of animals in terms of described species after the arthropods. Mollusks include snails and slugs, clams, ...

'' 25: 67–71.

Other interspecific relationships

''Tarebia granifera'' have been associated with the disappearance of two indigenous benthic gastropod species from rivers inPuerto Rico

Puerto Rico (; abbreviated PR; tnq, Boriken, ''Borinquen''), officially the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico ( es, link=yes, Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico, lit=Free Associated State of Puerto Rico), is a Caribbean island and Unincorporated ...

and have displaced the vegetation-associated pulmonate ''Biomphalaria glabrata

''Biomphalaria glabrata'' is a species of air-breathing freshwater snail, an aquatic pulmonate gastropod mollusk in the family Planorbidae, the ram's horn snails.

''Biomphalaria glabrata'' is an intermediate snail host for the trematode ''Sch ...

'' from streams and ponds on several Caribbean islands.Samadi S., Balzan C., Delay B. & Pointier J.-P. (1997). "Local distribution and abundance of thiarid snails in recently colonized rivers from the Caribbean area". ''Malacological Review'' 30: 45–52. Although the responsible mechanism is not understood, this has led to suggestions that it could be useful as a biocontrol

Biological control or biocontrol is a method of controlling pests, such as insects, mites, weeds, and plant diseases, using other organisms. It relies on predation, parasitism, herbivory, or other natural mechanisms, but typically also invo ...

agent in snail control operations within integrated schistosomiasis

Schistosomiasis, also known as snail fever, bilharzia, and Katayama fever, is a disease caused by parasitic flatworms called schistosomes. The urinary tract or the intestines may be infected. Symptoms include abdominal pain, diarrhea, bloody s ...

control programmes. They probably also compete

Competition is a rivalry where two or more parties strive for a common goal which cannot be shared: where one's gain is the other's loss (an example of which is a zero-sum game). Competition can arise between entities such as organisms, indivi ...

for space and resources (e.g. food) with indigenous infaunal and epifaunal invertebrates, especially where its densities are high. Under such conditions it is likely to alter the structure and biodiversity

Biodiversity or biological diversity is the variety and variability of life on Earth. Biodiversity is a measure of variation at the genetic (''genetic variability''), species (''species diversity''), and ecosystem (''ecosystem diversity'') l ...

of the entire benthic communities of invaded habitats and perhaps the vegetation-associated communities as well.

Anecdotal reports and observations suggest that in KwaZulu-Natal

KwaZulu-Natal (, also referred to as KZN and known as "the garden province") is a province of South Africa that was created in 1994 when the Zulu bantustan of KwaZulu ("Place of the Zulu" in Zulu) and Natal Province were merged. It is locate ...

the indigenous thiarid ''Melanoides tuberculata

The red-rimmed melania (''Melanoides tuberculata''), also known as Malayan livebearing snails or Malayan/Malaysian trumpet snails (often abbreviated to MTS) by aquarists, is a species of freshwater snail with an operculum, a parthenogenetic, a ...

'' is becoming less common and pressure from the spread of ''Tarebia granifera'', particularly at high densities, is a possible explanation. Like ''Tarebia granifera'', ''Melanoides tuberculata'' is parthenogenetic and ovoviviparous, grows to a similar size, are similar in size at first birth and juvenile output. Data from several habitats where the species occur sympatrically show however that in all such situations ''Tarebia granifera'' becomes numerically dominant.

''Tarebia granifera'' is likely to impact on another South-African indigenous thiarid, the poorly known ''Thiara amarula

''Thiara amarula'' is a species of gastropod belonging to the family Thiaridae.

Description

The length of the shell attains 32 mm.

Distribution

The species is found in Malesia, coasts of Indian and Pacific Ocean.; off Queensland

)

, nickn ...

'' in the saline St. Lucia estuary system.

Studies on the ecological impact of ''Tarebia granifera'' are urgently needed.

Human importance

In addition to its role as intermediate host for several economically important trematode species, ''Tarebia granifera'' has colonizedwater reservoir

A reservoir (; from French ''réservoir'' ) is an enlarged lake behind a dam. Such a dam may be either artificial, built to store fresh water or it may be a natural formation.

Reservoirs can be created in a number of ways, including control ...

s, dams and ponds on the premises of three large industrial plants in northern KwaZulu-Natal and been pumped out of at least one of them, blocking water pipe

Plumbing is any system that conveys fluids for a wide range of applications. Plumbing uses pipes, valves, plumbing fixtures, tanks, and other apparatuses to convey fluids. Heating and cooling (HVAC), waste removal, and potable water delivery ...

s and damaging equipment. This generally happens when snail densities are high and the damage is due to individuals being crushed so that pieces of shell and soft tissue are carried into machinery. Details of the nature and extent of this damage and the costs incurred are not available. There is no doubt that ''Tarebia granifera'' is able to pass unharmed through pumps

A pump is a device that moves fluids (liquids or gases), or sometimes slurries, by mechanical action, typically converted from electrical energy into hydraulic energy. Pumps can be classified into three major groups according to the method they u ...

, probably as juveniles.

References

This article incorporates CC-BY-3.0 text from references.Appleton C. C., Forbes A. T.& Demetriades N. T. (2009). "The occurrence, bionomics and potential impacts of the invasive freshwater snail ''Tarebia granifera'' (Lamarck, 1822) (Gastropoda: Thiaridae) in South Africa". ''Zoologische Mededelingen

''Zoologische Mededelingen'' was a peer-reviewed open access scientific journal publishing papers and monographs on animal systematics. The publisher was the National Museum of Natural History Naturalis in the Netherlands. The first issue appeared ...

'' 83. http://www.zoologischemededelingen.nl/83/nr03/a04Vázquez A. A. & Perera S. (2010). "Endemic Freshwater molluscs of Cuba and their conservation status". ''Tropical Conservation Science

Mongabay (mongabay.com) is a conservation news web portal that reports on environmental science, energy, and green design, and features extensive information on tropical rainforests, including pictures and deforestation statistics for countries ...

'' 3(2): 190–199HTM

Further reading

* Butler J. M., Ferguson F. F., Palmer J. R. & Jobin W. R. (1980). "Displacement of a colony of ''Biomphalaria glabrata'' by an invading population of ''Tarebia granifera'' in a small stream in Puerto Rico". ''Caribbean Journal of Science

The ''Caribbean Journal of Science'' is a triannual peer-reviewed open-access scientific journal publishing articles, research notes, and book reviews related to science in the Caribbean, with an emphasis on botany, zoology, ecology, conservation b ...

'' 16: 73–79* Chaniotis B. N., Butler J. M., Ferguson F. F. & Jobin W. R. (1980). "Thermal limits, desiccation tolerance, and humidity reactions of ''Thiara'' (''Tarebia'') ''granifera mauiensis'' (Gastropoda: Thiaridae) host of the asiatic lung fluke disease". ''

Caribbean Journal of Science

The ''Caribbean Journal of Science'' is a triannual peer-reviewed open-access scientific journal publishing articles, research notes, and book reviews related to science in the Caribbean, with an emphasis on botany, zoology, ecology, conservation b ...

'' 16: 91–93* Ferguson et al. (1958)

"Potential for Biological Control of ''Australorbis Glabratus'', the Intermediate Host of Puerto Rican Schistosomiasis"

''

The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene

The American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (ASTMH) is an Arlington, Virginia-based non-profit organization of scientists, clinicians, students and program professionals whose longstanding mission is to promote global health through the ...

'' 7: 491–493.

* .

* .

* Miranda N. A. F. & Perissinotto R. (2012) "Stable Isotope Evidence for Dietary Overlap between Alien and Native Gastropods in Coastal Lakes of Northern KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa". ''PLoS ONE'' 7(2): e31897. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0031897.

External links

{{DEFAULTSORT:Tarebia Granifera Thiaridae Gastropods described in 1822 Freshwater molluscs of Oceania