Talmud Torah on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

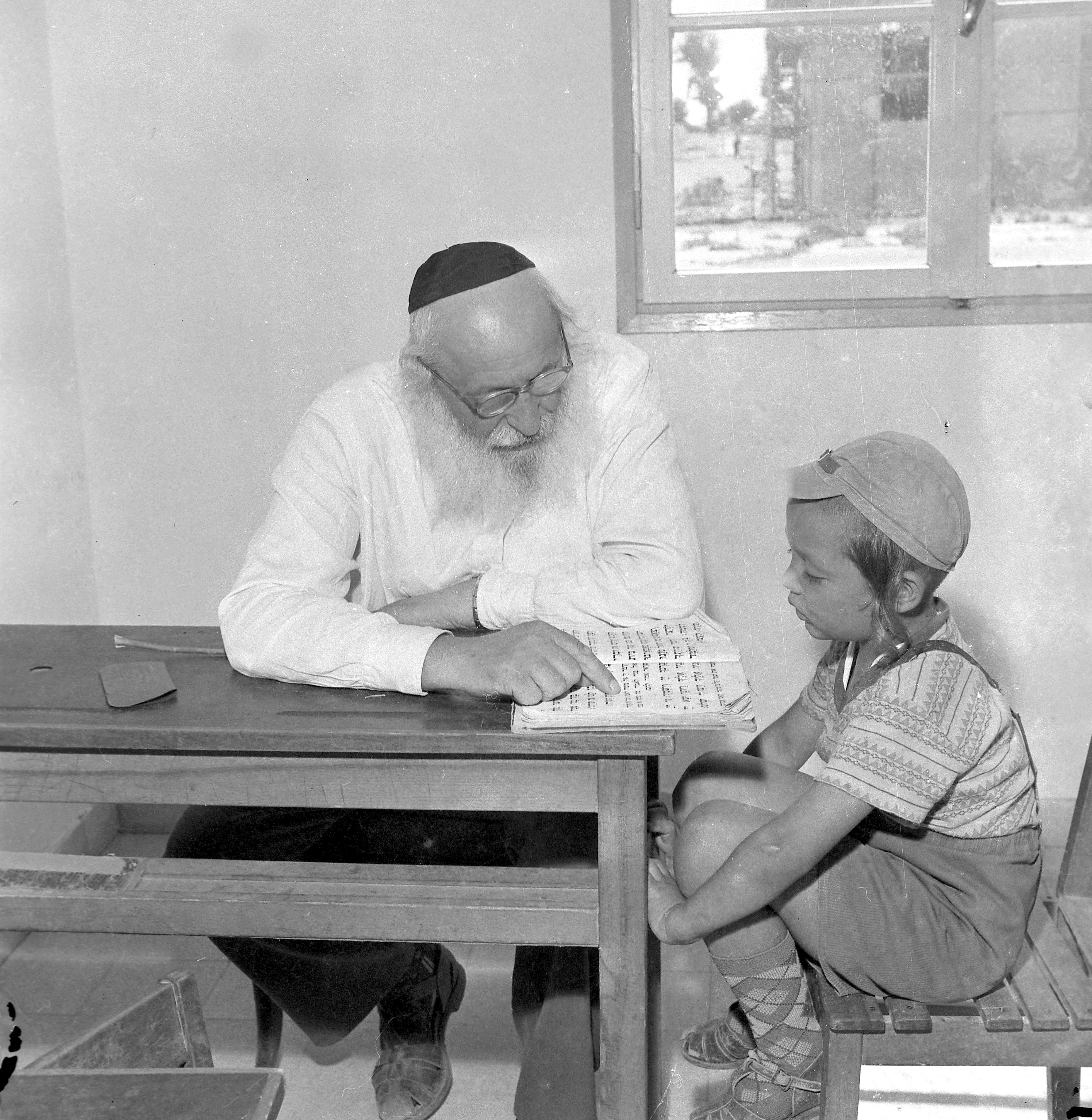

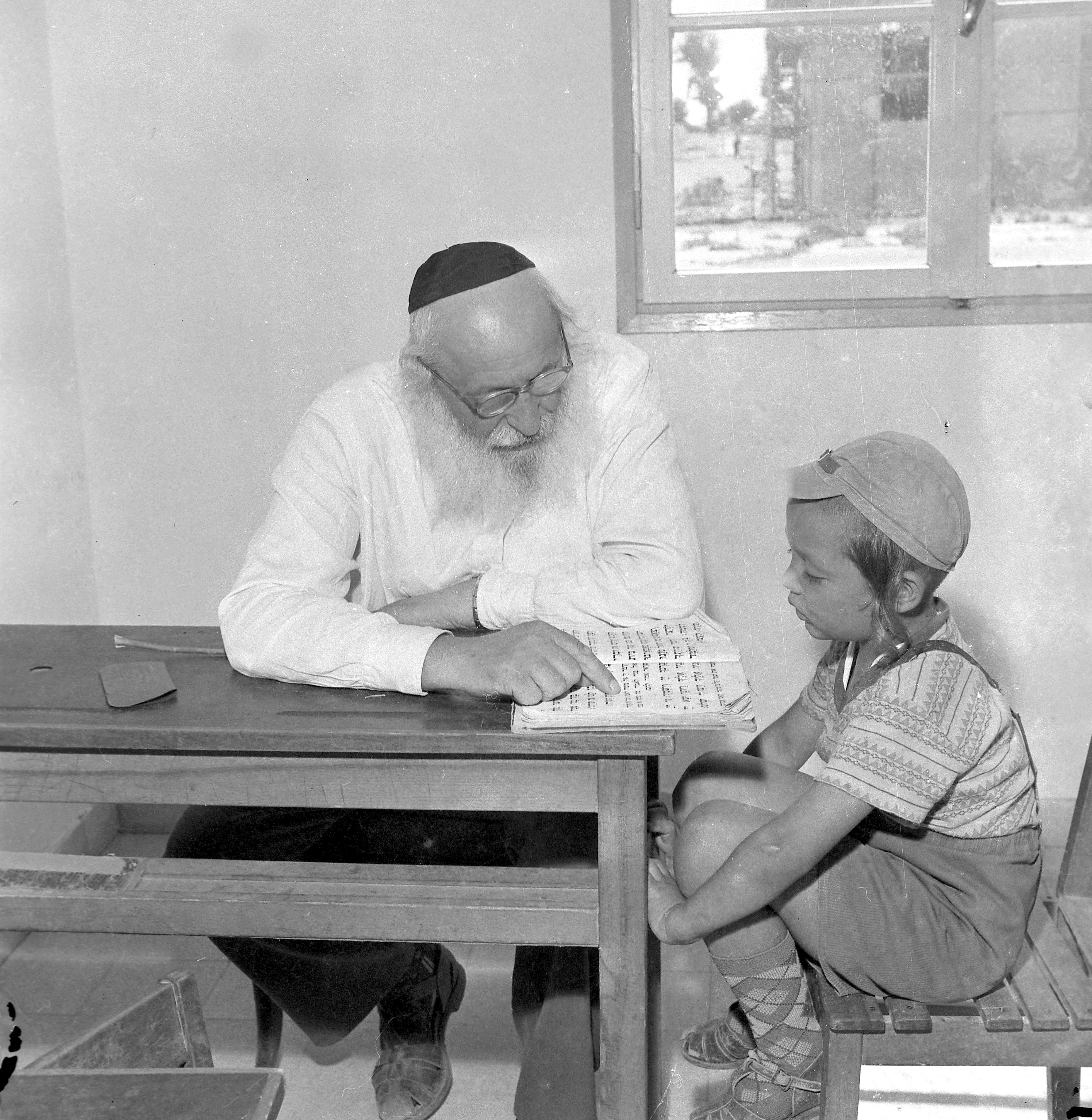

Talmud Torah ( he, תלמוד תורה, lit. 'Study of the Torah') schools were created in the Jewish world, both

Talmud Torah ( he, תלמוד תורה, lit. 'Study of the Torah') schools were created in the Jewish world, both

The expense was borne by the community, and strict discipline was observed.

The expense was borne by the community, and strict discipline was observed.

In Jerusalem the Talmud Torah of the

In Jerusalem the Talmud Torah of the

In America the Machzikei Talmud Torah in

In America the Machzikei Talmud Torah in

Jewish Encyclopedia: Talmud Torah

Jewish education *Talmud Torah Jewish schools Orthodox yeshivas

Talmud Torah ( he, תלמוד תורה, lit. 'Study of the Torah') schools were created in the Jewish world, both

Talmud Torah ( he, תלמוד תורה, lit. 'Study of the Torah') schools were created in the Jewish world, both Ashkenazic

Ashkenazi Jews ( ; he, יְהוּדֵי אַשְׁכְּנַז, translit=Yehudei Ashkenaz, ; yi, אַשכּנזישע ייִדן, Ashkenazishe Yidn), also known as Ashkenazic Jews or ''Ashkenazim'',, Ashkenazi Hebrew pronunciation: , singu ...

and Sephardic

Sephardic (or Sephardi) Jews (, ; lad, Djudíos Sefardíes), also ''Sepharadim'' , Modern Hebrew: ''Sfaradim'', Tiberian Hebrew, Tiberian: Səp̄āraddîm, also , ''Ye'hude Sepharad'', lit. "The Jews of Spain", es, Judíos sefardíes (or ), ...

, as a form of religious school

A religious school is a school that either has a religious component in its operations or its curriculum, or exists primarily for the purpose of teaching aspects of a particular religion.

Children

A school can either be of two types, though the sa ...

for boys of modest backgrounds, where they were given an elementary education in Hebrew

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

, the scripture

Religious texts, including scripture, are texts which various religions consider to be of central importance to their religious tradition. They differ from literature by being a compilation or discussion of beliefs, mythologies, ritual prac ...

s (especially the Torah

The Torah (; hbo, ''Tōrā'', "Instruction", "Teaching" or "Law") is the compilation of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, namely the books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. In that sense, Torah means the s ...

), and the Talmud

The Talmud (; he, , Talmūḏ) is the central text of Rabbinic Judaism and the primary source of Jewish religious law (''halakha'') and Jewish theology. Until the advent of modernity, in nearly all Jewish communities, the Talmud was the cente ...

(and ''halakha

''Halakha'' (; he, הֲלָכָה, ), also transliterated as ''halacha'', ''halakhah'', and ''halocho'' ( ), is the collective body of Jewish religious laws which is derived from the written and Oral Torah. Halakha is based on biblical commandm ...

''). This was meant to prepare them for ''yeshiva

A yeshiva (; he, ישיבה, , sitting; pl. , or ) is a traditional Jewish educational institution focused on the study of Rabbinic literature, primarily the Talmud and halacha (Jewish law), while Torah and Jewish philosophy are s ...

'' or, particularly in the movement's modern form, for Jewish education at a high school level. The Talmud Torah was modeled after the ''cheder

A ''cheder'' ( he, חדר, lit. "room"; Yiddish pronunciation ''kheyder'') is a traditional primary school teaching the basics of Judaism and the Hebrew language.

History

''Cheders'' were widely found in Europe before the end of the 18th ...

'', a traditional form of schooling whose essential elements it incorporated, with changes appropriate to its public form rather than the ''cheder's'' private financing through less formal or institutionalized mechanisms, including tuition fees and donations.

In the United States, the term ''Talmud Torah'' refers to the afternoon program for boys and girls after attending public school. This form of Jewish education was prevalent from the mid–19th century through "the 1940s and 1950s." Although by the 1980s full-time Jewish day schools (yeshivas) were the norm in the United States, some European countries still had these.

History

The father was traditionally the sole teacher of his children in Jewish history (Deut. xi. 19). The institution known as the ''bei rav'' or ''bet rabban'' (house of the teacher), or as the ''bei safra'' or ''bet sefer'' (house of the book), is said to have been originated byEzra

Ezra (; he, עֶזְרָא, '; fl. 480–440 BCE), also called Ezra the Scribe (, ') and Ezra the Priest in the Book of Ezra, was a Jewish scribe (''sofer'') and priest (''kohen''). In Greco-Latin Ezra is called Esdras ( grc-gre, Ἔσδρας ...

and his Great Assembly

According to Jewish tradition the Men of the Great Assembly ( he, כְּנֶסֶת הַגְּדוֹלָה) or Anshei Knesset HaGedolah (, "The Men of the Great Assembly"), also known as the Great Synagogue, or ''Synod'', was an assembly of 120 sc ...

, who provided a public school in Jerusalem to secure the education of fatherless boys of the age of sixteen years and upward. But the school system did not develop until Joshua ben Gamla

Joshua ben Gamla (), also called Jesus the son of Gamala (), was a Jewish high priest in about 64-65 CE. He was killed during the First Jewish–Roman War. While the Talmud refers to Joshua ben Gamla, the earlier Greek works of Josephus Flavius ...

the high priest caused public schools to be opened in every town and hamlet for all children above six or seven years of age (B. B. 21a).

The expense was borne by the community, and strict discipline was observed.

The expense was borne by the community, and strict discipline was observed. Abba Arika

Abba Arikha (175–247 CE; Jewish Babylonian Aramaic: ; born: ''Rav Abba bar Aybo'', ), commonly known as Rav (), was a Jewish amora of the 3rd century. He was born and lived in Kafri, Asoristan, in the Sasanian Empire.

Abba Arikha establis ...

, however, ordered Samuel b. Shilat to deal tenderly with the pupils, to refrain from corporal punishment, or at most to use a shoe-strap in correcting pupils for inattention. A stupid pupil was made monitor until able to grasp the art of learning. Rabbah bar Nahmani

Rabbah bar Nachmani ( he, רבה בר נחמני) (died c. 320 CE) was a Jewish Talmudist known throughout the Talmud simply as Rabbah. He was a third-generation '' amora'' who lived in Babylonia.

Biography

Rabbah was a kohen descended from E ...

fixed the number of pupils at twenty-five for one teacher; if the number was between twenty-five and forty an assistant teacher ("resh dukana") was necessary; and for over forty, two teachers were required.

Only married men were engaged as teachers, but there is a difference of opinion regarding the qualification of the ''melammed

Melamed, ''Melammed'' ( he, מלמד, Teacher) in Biblical times denoted a religious teacher or instructor in general (e.g., in Psalm 119:99 and Proverbs 5:13), but which in the Talmudic period was applied especially to a teacher of children, and ...

'' (teacher). Rabbah bar Nahmani preferred one who taught his pupils much, even though somewhat carelessly, while Rav Dimi of Nehardea

Nehardea or Nehardeah ( arc, נהרדעא, ''nəhardəʿā'' "river of knowledge") was a city from the area called by ancient Jewish sources Babylonia, situated at or near the junction of the Euphrates with the Nahr Malka (the Royal Canal), one ...

preferred one who taught his pupils little, but that correctly, as an error in reading once adopted is hard to correct (ib.). It is, of course, assumed that both qualifications were rarely to be found in one person.

The teaching in the Talmud Torah consumed the whole day, and in the winter months a few hours of the night besides. Teaching was suspended in the afternoon of Friday, and in the afternoon of the day preceding a holy day. On Shabbat

Shabbat (, , or ; he, שַׁבָּת, Šabbāṯ, , ) or the Sabbath (), also called Shabbos (, ) by Ashkenazim, is Judaism's day of rest on the seventh day of the week—i.e., Saturday. On this day, religious Jews remember the biblical storie ...

s and holy days no new lessons were assigned; but the work of the previous week was reviewed on Shabbat afternoons by the child's parent or guardian (Shulḥan 'Aruk, Yoreh De'ah, 245).

In later times, possibly influenced by the Christian parochial schools of the thirteenth century, the reading of the prayers and benedictions and the teaching of the principles of the Jewish faith were included. In almost every community an organization called ''Hevra Talmud Torah'' was formed, whose duty was to create a fund and provide means for the support of public schools, and to control all teachers and pupils.

Asher ben Jehiel

Asher ben Jehiel ( he, אשר בן יחיאל, or Asher ben Yechiel, sometimes Asheri) (1250 or 1259 – 1327) was an eminent rabbi and Talmudist best known for his abstract of Talmudic law. He is often referred to as Rabbenu Asher, “our Rabb ...

(1250–1328) ruled to allow withdrawals from the funds of the Talmud Torah for the purpose of meeting the annual tax collected by the local governor, since otherwise great hardships would fall upon the poor, who were liable to be stripped of all their belongings if they failed in the prompt payment of their taxes (Responsa, rule vi., § 2). On the other hand, money from the general charity fund was at times employed to support the Talmud Torah, and donations for a synagogue

A synagogue, ', 'house of assembly', or ', "house of prayer"; Yiddish: ''shul'', Ladino: or ' (from synagogue); or ', "community". sometimes referred to as shul, and interchangeably used with the word temple, is a Jewish house of worshi ...

or cemetery were similarly used (ib. rule xiii., §§ 5,14).

Because Talmudic and Torah education was traditionally deemed obligatory for males and not females, Talmud Torahs were traditionally single-sex institutions. It is common even in the present day for men to continue their full-time Torah studies well into their third decade of life while women marry.

The Talmud Torah organization in Rome included eight societies in 1554, and was reconstituted August 13, 1617 (Rieger, "Gesch. der Juden in Rom," p. 316, Berlin, 1895). Later, certain synagogues assumed the name "Talmud Torah," as in the case of one at Fes, Morocco

Fez or Fes (; ar, فاس, fās; zgh, ⴼⵉⵣⴰⵣ, fizaz; french: Fès) is a city in northern inland Morocco and the capital of the Fès-Meknès administrative region. It is the second largest city in Morocco, with a population of 1.11 mi ...

in 1603 (Ankava, "Kerem Ḥemed," ii. 78, Leghorn, 1869) and one at Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo metro ...

. This was probably because the school was held in or adjoined the synagogue.

Funding

The income of the society was derived from several sources: : (a) one-sixth of the Monday and Thursday contributions in the synagogues and other places of worship; : (b) donations at circumcisions from guests invited to the feast; : (c) donations at weddings from the groom and the bride and from invited guests; : (d) one-tenth of the collections in the charity-box known as the ''mattan ba-setar''.Samuel de Medina Rabbi Samuel ben Moses de Medina (abbreviated RaShDaM, or ''Maharashdam''; 1505 – October 12, 1589), was a Talmudist and author from Thessaloniki. He was principal of the Talmudic college of that city, which produced a great number of promine ...

(1505–89) ruled that in case of a legacy left by will to a Talmud Torah and guaranteed by the testator's brother, the latter was not held liable if the property had been consumed owing to the prolonged illness of the deceased (Responsa, Ḥoshen Mishpaṭ, No. 357). A legacy for the support of a yeshivah and Talmud Torah in a certain town, if accompanied by a provision that it may be managed "as the son of the testator may see fit," may be transferred, it was declared, to a yeshivah elsewhere (ib. Oraḥ Ḥayyim, i., No. 60; see also "Paḥad Yiẓḥaḳ," s.v., p. 43a).

Administration

The election of officers was made by ballot: three '' gabba'im'', three vice-gabba'im, and a treasurer. Only learned and honorable men over 36 years of age were eligible for election. The ''taḳḳanot'' regulating these sources of the Talmud Torah's income were in existence in the time ofMoses Isserles

). He is not to be confused with Meir Abulafia, known as "Ramah" ( he, רמ״ה, italic=no, links=no), nor with Menahem Azariah da Fano, known as "Rema MiPano" ( he, רמ״ע מפאנו, italic=no, links=no).

Rabbi Moses Isserles ( he, משה ...

. Yoel Sirkis

Joel ben Samuel Sirkis (Hebrew: רבי יואל בן שמואל סירקיש; born 1561 - March 14, 1640) also known as the Bach (an abbreviation of his magnum opus BAyit CHadash), was a prominent Ashkenazi posek and halakhist, who lived in cent ...

, rabbi of Cracow in 1638, endorsed these regulations and added many others, all of which were confirmed at a general assembly of seventy representatives of the congregations on the 25th of Ṭebet, 5398 (1638; F. H. Wetstein, "Ḳadmoniyyot," document No. 1, Cracow, 1892).

Solomon b. Abraham ha-Kohen (sixteenth century) decided that it requires the unanimous consent of the eight trustees of a Talmud Torah to engage teachers where a resolution has been passed that "no trustee or trustees shall engage the service of a Melamed without the consent of the whole" (Responsa, ii., No. 89, ed. Venice, 1592).

As a specimen of the medieval organization of these schools that of the Cracow schools may be selected. From the congregational record (''pinḳes'') of Cracow in 1551 it appears that the Talmud Torah society controlled both private and public schools. It passed the following ''taḳḳanot'', or Jewish legal writs:

(1) The members shall have general supervision over the teachers and shall visit the Talmud Torah every week to see that the pupils are properly taught.

(2) No ''melamed'' may teach the Pentateuch

The Torah (; hbo, ''Tōrā'', "Instruction", "Teaching" or "Law") is the compilation of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, namely the books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. In that sense, Torah means the sa ...

except with the translation "Be'er Mosheh" (Judæo-German transl. by Moses b. Issachar, Prague, 1605), "which is in our vernacular"; for the advanced pupils he shall use no other than the Rashi

Shlomo Yitzchaki ( he, רבי שלמה יצחקי; la, Salomon Isaacides; french: Salomon de Troyes, 22 February 1040 – 13 July 1105), today generally known by the acronym Rashi (see below), was a medieval French rabbi and author of a compre ...

commentary.

(3) A ''melamed'' in the primary class shall teach not more than twenty-five pupils and shall have two assistants.

(4) One ''melamed'' shall not compete with another during the term of his engagement, and shall not seek to obtain a pupil in charge of another teacher, even at the expiration of the term, unless the father or the guardian of the pupil desires to make a change.

(5) The members of the Ḥebra Talmud Torah shall hire a competent and God-fearing ''melamed'', with an assistant, for poor and orphaned boys at the ''bet ha-midrash

A ''beth midrash'' ( he, בית מדרש, or ''beis medrash'', ''beit midrash'', pl. ''batei midrash'' "House of Learning") is a hall dedicated for Torah study, often translated as a "study hall." It is distinct from a synagogue (''beth kne ...

''.

(6) The ''melamed'' and assistant shall teach pupils the Hebrew alphabet

The Hebrew alphabet ( he, wikt:אלפבית, אָלֶף־בֵּית עִבְרִי, ), known variously by scholars as the Ktav Ashuri, Jewish script, square script and block script, is an abjad script used in the writing of the Hebrew languag ...

(with the vowels), the Siddur

A siddur ( he, סִדּוּר ; plural siddurim ) is a Jewish prayer book containing a set order of daily prayers. The word comes from the Hebrew root , meaning 'order.'

Other terms for prayer books are ''tefillot'' () among Sephardi Jews, ' ...

, the Pentateuch (with the "Be'er Mosheh" translation), the Rashi commentary, the order of the prayers, etiquette, and good behavior—every boy according to his grade and intelligence; also reading and writing in the vernacular. The more advanced shall be taught Hebrew grammar and arithmetic; those of the highest grade shall study Talmud with Rashi and Tosafot

The Tosafot, Tosafos or Tosfot ( he, תוספות) are medieval commentaries on the Talmud. They take the form of critical and explanatory glosses, printed, in almost all Talmud editions, on the outer margin and opposite Rashi's notes.

The auth ...

.

(7) Boys near the age of thirteen shall learn the regulations regarding ''tefillin

Tefillin (; Modern Hebrew language, Israeli Hebrew: / ; Ashkenazim, Ashkenazic pronunciation: ), or phylacteries, are a set of small black leather boxes with leather straps containing scrolls of parchment inscribed with verses from the Torah. Te ...

''.

(8) At the age of fourteen a boy who is incapable of learning Talmud shall be taught a trade or become a servant in a household.

Curriculum

TheSephardim

Sephardic (or Sephardi) Jews (, ; lad, Djudíos Sefardíes), also ''Sepharadim'' , Modern Hebrew: ''Sfaradim'', Tiberian: Səp̄āraddîm, also , ''Ye'hude Sepharad'', lit. "The Jews of Spain", es, Judíos sefardíes (or ), pt, Judeus sefar ...

are said to have conducted their Talmud Torah schools more methodically than the Ashkenazim

Ashkenazi Jews ( ; he, יְהוּדֵי אַשְׁכְּנַז, translit=Yehudei Ashkenaz, ; yi, אַשכּנזישע ייִדן, Ashkenazishe Yidn), also known as Ashkenazic Jews or ''Ashkenazim'',, Ashkenazi Hebrew pronunciation: , singu ...

, particularly in Europe. The one in Amsterdam

Amsterdam ( , , , lit. ''The Dam on the River Amstel'') is the Capital of the Netherlands, capital and Municipalities of the Netherlands, most populous city of the Netherlands, with The Hague being the seat of government. It has a population ...

was highly praised by Shabbethai Horowitz

Shabtai Horowitz ( he, שבתי הורוויץ; 1590 – 12 April 1660) was a rabbi and talmudist, probably born in Ostroh, Volhynia. He was the son of the kabbalist Isaiah Horowitz, and at an early age married the daughter of the wealthy and sc ...

("Wawe ha-'Ammudim," p. 9b, appended to "Shelah Shelah may refer to:

* Shelah (son of Judah), a son of Judah according to the Bible

* Shelah (name), a Hebrew personal name

* Shlach, the 37th weekly Torah portion (parshah) in the annual Jewish cycle of Torah reading

* Salih, a prophet described ...

", Amsterdam, 1698). Shabbethai Bass Shabbethai ben Joseph Bass (1641–1718) ( he, שבתי בן יוסף; also known by the family-name Strom), born at Kalisz, was the founder of Jewish bibliography, and author of the ''Siftei Chachamim'' supercommentary on Rashi's commentary on the ...

, in the introduction to his "Sifte Yeshanim" (p. 8a, ib. 1680), describes this Talmud Torah and wishes it might serve as a model for other schools:

In Jewish communities around the world

Germany

The Talmud Torah atNikolsburg

Mikulov (; german: Nikolsburg; yi, ניקאלשבורג, ''Nikolshburg'') is a town in Břeclav District in the South Moravian Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 7,400 inhabitants. The historic centre of Mikulov is well preserved and i ...

, Moravia

Moravia ( , also , ; cs, Morava ; german: link=yes, Mähren ; pl, Morawy ; szl, Morawa; la, Moravia) is a historical region in the east of the Czech Republic and one of three historical Czech lands, with Bohemia and Czech Silesia.

The me ...

, from 1724 to 1744, gave poor boys an education equal to that which was offered their more fortunate companions. The studies consisted of Siddur, Chumash Chumash may refer to:

*Chumash (Judaism), a Hebrew word for the Pentateuch, used in Judaism

*Chumash people, a Native American people of southern California

*Chumashan languages, indigenous languages of California

See also

*Chumash traditional n ...

(Pentateuch), and Talmud

The Talmud (; he, , Talmūḏ) is the central text of Rabbinic Judaism and the primary source of Jewish religious law (''halakha'') and Jewish theology. Until the advent of modernity, in nearly all Jewish communities, the Talmud was the cente ...

(Moritz Güdemann

Moritz Güdemann ( he, משה גידמן; 19 February 1835 – 5 August 1918) was an Austrian rabbi and historian. He served as chief rabbi of Vienna.

Biography

Moritz (Moshe) Güdemann attended the Jewish school in Hildesheim, and thereafter we ...

, ''Quellenschriften zur Gesch. des Unterrichts und der Erziehung bei den Deutschen Juden,'' p. 275). The schools in eastern Europe retained the ancient type and methods of the Ashkenazic schools up to the middle of the nineteenth century, when a movement for improvement and better management took place in the larger cities.

Russia

In 1857 atOdessa

Odesa (also spelled Odessa) is the third most populous city and municipality in Ukraine and a major seaport and transport hub located in the south-west of the country, on the northwestern shore of the Black Sea. The city is also the administrativ ...

, the Talmud Torah which had existed ever since the city was chartered was reorganized into a model school by distinguished pedagogues. In 1881 S. J. Abramowitch was appointed principal over 400 pupils. In 1904 two branches were opened in the suburbs with an additional 400 pupils. The boys were furnished text-books and clothing for free. Expenses were altogether 20,000 ruble

The ruble (American English) or rouble (Commonwealth English) (; rus, рубль, p=rublʲ) is the currency unit of Belarus and Russia. Historically, it was the currency of the Russian Empire and of the Soviet Union.

, currencies named ''rub ...

s annually. Every city within the Pale of Settlement

The Pale of Settlement (russian: Черта́ осе́длости, '; yi, דער תּחום-המושבֿ, '; he, תְּחוּם הַמּוֹשָב, ') was a western region of the Russian Empire with varying borders that existed from 1791 to 19 ...

in Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

had a similar school. The income was derived from a Jewish tax on meat and from private contributions.

Jerusalem

Sephardim

Sephardic (or Sephardi) Jews (, ; lad, Djudíos Sefardíes), also ''Sepharadim'' , Modern Hebrew: ''Sfaradim'', Tiberian: Səp̄āraddîm, also , ''Ye'hude Sepharad'', lit. "The Jews of Spain", es, Judíos sefardíes (or ), pt, Judeus sefar ...

, called ''Tiferet Yerushalayim'', was reorganized by the ''Hakham Bashi

''Haham Bashi'' (chachampasēs) which is explained as "μεγάλος ραβίνος" or "Grand Rabbi".

* Persian: khākhāmbāšīgarī is used in the Persian version of the Ottoman Constitution of 1876. Strauss stated that there was a possibili ...

'' rabbi Raphael Meir Panigel

Raphael Meir ben Yehuda Panigel (1804–1893) was the Sephardi Chief Rabbi of Jerusalem, Ottoman Empire.

Panigel was born in Pazardzhik, Bulgaria, but his family emigrated to the Land of Israel when he was a child. In 1828 and in 1863, he was a ...

in 1891, with 300 pupils and 13 teachers. The boys learned Arabic and arithmetic in addition to other subjects, which ranged from the alphabet to the Talmud. The time of study was from sunrise to sunset. The largest contributions for the support of the school came from the Sassoon family

The Sassoon family, known as "Rothschilds of the East" due to the immense wealth they accumulated in finance and trade, are a family of Baghdadi Jewish descent. Originally based in Baghdad, Iraq, they later moved to Bombay, India, and then emig ...

, Baghdadi Jews

The former communities of Jewish migrants and their descendants from Baghdad and elsewhere in the Middle East are traditionally called Baghdadi Jews or Iraqi Jews. They settled primarily in the ports and along the trade routes around the Indian ...

of Bombay

Mumbai (, ; also known as Bombay — the official name until 1995) is the capital city of the Indian state of Maharashtra and the ''de facto'' financial centre of India. According to the United Nations, as of 2018, Mumbai is the second- ...

and Calcutta

Kolkata (, or , ; also known as Calcutta , List of renamed places in India#West Bengal, the official name until 2001) is the Capital city, capital of the Indian States and union territories of India, state of West Bengal, on the eastern ba ...

, through the '' meshullachim''.

The Ashkenazic

Ashkenazi Jews ( ; he, יְהוּדֵי אַשְׁכְּנַז, translit=Yehudei Ashkenaz, ; yi, אַשכּנזישע ייִדן, Ashkenazishe Yidn), also known as Ashkenazic Jews or ''Ashkenazim'',, Ashkenazi Hebrew pronunciation: , singu ...

Talmud Torah and Etz Chaim Yeshiva, with 35 teachers and over 1,000 pupils, succeeded the school established by Judah HeHasid. It was started with a fund contributed by Hirsch Wolf Fischbein and David Janover in 1860. The annual expenditure was in 1910 about $10,000, over half of which was collected in the United States. At Jaffa the Talmud Torah and yeshiva Sha'are Torah was organized in 1886 by N. H. Lewi, with 9 teachers and 9 classes for 102 boys. Its expenses were about $2,000 yearly, mostly covered by donations from abroad.

United States

In America the Machzikei Talmud Torah in

In America the Machzikei Talmud Torah in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

, an Ashkenazi Talmud Torah, was organized in 1883 by Israel (Isidor) Rosenthal. It maintained schools on its own premises at 225-227 East Broadway. It instructed over 1,100 boys at a yearly expense of about $12,000. On January 22, 1905, the society opened a branch at 67 East 7th street, to which Jacob H. Schiff donated $25,000. The society was managed by a board of directors and a committee of education. The studies comprised elementary Hebrew, the reading of the prayers, the translation of the Pentateuch into Yiddish

Yiddish (, or , ''yidish'' or ''idish'', , ; , ''Yidish-Taytsh'', ) is a West Germanic language historically spoken by Ashkenazi Jews. It originated during the 9th century in Central Europe, providing the nascent Ashkenazi community with a ver ...

and English, and the principles of the Jewish faith and practise. The time of study occupied only two hours per day, after public-school hours, as all pupils attended the city schools for secular education. There were several other Talmud Torahs in New York; and similar institutions existed in all cities of the United States and Canada with a large Jewish population.

Girls in the United States at this time were often educated at public schools together with boys, and they received their Jewish education through programs at synagogues and Sunday schools, because Jewish day schools were less common. As a result, the "New World" Talmud Torah of the first half of the 20th century was co-ed

Mixed-sex education, also known as mixed-gender education, co-education, or coeducation (abbreviated to co-ed or coed), is a system of education where males and females are educated together. Whereas single-sex education was more common up to ...

.

Reference

{{ReflistSee also

*Cheder

A ''cheder'' ( he, חדר, lit. "room"; Yiddish pronunciation ''kheyder'') is a traditional primary school teaching the basics of Judaism and the Hebrew language.

History

''Cheders'' were widely found in Europe before the end of the 18th ...

Further reading

* Judah Löb, Omer mi-Yehudah'',Brünn

Brno ( , ; german: Brünn ) is a Statutory city (Czech Republic), city in the South Moravian Region of the Czech Republic. Located at the confluence of the Svitava (river), Svitava and Svratka (river), Svratka rivers, Brno has about 380,000 inha ...

, 1790;

* Aleksander Zederbaum

Aleksander Ossypovich Zederbaum (; August 27, 1816, Zamość – September 8, 1893, Saint Petersburg) was a Polish-Russian Jewish journalist who wrote primarily in Hebrew. He was founder and editor of ''Ha-Melitz'', and other periodicals published ...

, ''Die Geheimnisse von Berditchev'', pp. 38-44, Warsaw

Warsaw ( pl, Warszawa, ), officially the Capital City of Warsaw,, abbreviation: ''m.st. Warszawa'' is the capital and largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the River Vistula in east-central Poland, and its population is officia ...

, 1870 (a sketch);

* Mordekhai David Brandstetter, essay in ''Ha-Eshkol'', v. 70-84.

External links

Jewish Encyclopedia: Talmud Torah

Jewish education *Talmud Torah Jewish schools Orthodox yeshivas