Tagantsev conspiracy on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Tagantsev conspiracy (or the case of the Petrograd Military Organization) was a non-existent

After the initial failure,

After the initial failure,

The most famous victim of the case was the poet

The most famous victim of the case was the poet

Vladimir Tagantsev

on memorial book of persecuted geologists

Extended version in Russian)Diary of Vladimir Tagantsev

interview with Yuri Chernyaev on RFERL, and it

summary

{{Authority control False flag operations Political and cultural purges Soviet Union intelligence operations Anti-intellectualism

monarchist

Monarchism is the advocacy of the system of monarchy or monarchical rule. A monarchist is an individual who supports this form of government independently of any specific monarch, whereas one who supports a particular monarch is a royalist. ...

conspiracy fabricated by the Soviet secret police

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

in 1921 to terrorize intellectuals who might be in a potential opposition to the ruling Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

regime. Alexander N. Yakovlev, ''Century of Violence in Soviet Russia'', Yale University Press

Yale University Press is the university press of Yale University. It was founded in 1908 by George Parmly Day, and became an official department of Yale University in 1961, but it remains financially and operationally autonomous.

, Yale Universi ...

(2002), pages 107-108, . As its result, more than 800 people, mostly from scientific and artistic communities in Petrograd (modern-day Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

), were arrested on false terrorism charges, out of which 98 were executed and many were sent to concentration camps. Among the executed was the poet Nikolay Gumilev

Nikolay Stepanovich Gumilyov ( rus, Никола́й Степа́нович Гумилёв, p=nʲɪkɐˈlaj sʲtʲɪˈpanəvʲɪtɕ ɡʊmʲɪˈlʲɵf, a=Nikolay Styepanovich Gumilyov.ru.vorb.oga; April 15 NS 1886 – August 26, 1921) was a poe ...

, the co-founder of the influential Acmeist movement.

The affair was named after Vladimir Nikolaevich Tagantsev, a geographer and member of the Russian Academy of Sciences

The Russian Academy of Sciences (RAS; russian: Росси́йская акаде́мия нау́к (РАН) ''Rossíyskaya akadémiya naúk'') consists of the national academy of Russia; a network of scientific research institutes from across t ...

, who was arrested, tortured, and tricked into disclosing hundreds of names of people who did not like the Bolshevik regime. Among the security officers that manufactured the case was Yakov Agranov

Yakov Saulovich Agranov (russian: Я́ков Сау́лович Агра́нов; born Yankel Samuilovich Sorenson; 12 October 1893–1 August 1938) was the first chief of the Soviet Main Directorate of State Security and a deputy of NKVD c ...

, who later became one of the chief organizers of Stalinist show trials and the Great Purge

The Great Purge or the Great Terror (russian: Большой террор), also known as the Year of '37 (russian: 37-й год, translit=Tridtsat sedmoi god, label=none) and the Yezhovshchina ('period of Nikolay Yezhov, Yezhov'), was General ...

in the 1930s. The case was officially declared fabricated and its victims rehabilitated by Russian authorities in 1992.Vitaliy Shentalinsky, ''Crime Without Punishment'', Progress-Pleyada, Moscow, 2007, (Russian

Russian(s) refers to anything related to Russia, including:

*Russians (, ''russkiye''), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

*Rossiyane (), Russian language term for all citizens and peo ...

: Виталий Шенталинский, "Преступление без наказания"), pages 197–288.

Background

On December 5, 1920, all departments of the Soviet secret policeCheka

The All-Russian Extraordinary Commission ( rus, Всероссийская чрезвычайная комиссия, r=Vserossiyskaya chrezvychaynaya komissiya, p=fsʲɪrɐˈsʲijskəjə tɕrʲɪzvɨˈtɕæjnəjə kɐˈmʲisʲɪjə), abbreviated ...

received a top secret order from Feliks Dzerzhinsky

Felix Edmundovich Dzerzhinsky ( pl, Feliks Dzierżyński ; russian: Фе́ликс Эдму́ндович Дзержи́нский; – 20 July 1926), nicknamed "Iron Felix", was a Bolshevik revolutionary and official, born into Poland, Polish n ...

to start creating false flag

A false flag operation is an act committed with the intent of disguising the actual source of responsibility and pinning blame on another party. The term "false flag" originated in the 16th century as an expression meaning an intentional misr ...

White Army

The White Army (russian: Белая армия, Belaya armiya) or White Guard (russian: Бѣлая гвардія/Белая гвардия, Belaya gvardiya, label=none), also referred to as the Whites or White Guardsmen (russian: Бѣлогв� ...

organizations, "underground and terrorist groups" to facilitate finding "foreign agents on our territory". This was planned partially as a provocation, in order to identify potentially disloyal citizens who might wish to join the Bolsheviks' enemies.

A few months later, in February 1921, the Kronstadt rebellion

The Kronstadt rebellion ( rus, Кронштадтское восстание, Kronshtadtskoye vosstaniye) was a 1921 insurrection of Soviet sailors and civilians against the Bolshevik government in the Russian SFSR port city of Kronstadt. Locat ...

began. This was a left-wing uprising against the Bolshevik regime by soldiers and sailors. Additionally, the Bolsheviks understood that the majority of intelligentsia

The intelligentsia is a status class composed of the university-educated people of a society who engage in the complex mental labours by which they critique, shape, and lead in the politics, policies, and culture of their society; as such, the in ...

did not support them. On March 8, the Council of People's Commissars

The Councils of People's Commissars (SNK; russian: Совет народных комиссаров (СНК), ''Sovet narodnykh kommissarov''), commonly known as the ''Sovnarkom'' (Совнарком), were the highest executive authorities of ...

(Sovnarkom) send a letter to People's Commissariat for Education The People's Commissariat for Education (or Narkompros; russian: Народный комиссариат просвещения, Наркомпрос, directly translated as the "People's Commissariat for Enlightenment") was the Soviet agency charge ...

(Narkompros) asking to identify a group of unreliable intellectuals who could be a target of future repressions.

On June 4, Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 19 ...

received a telegram from Leonid Krasin

Leonid Borisovich Krasin (russian: Леони́д Бори́сович Кра́син; 15 July 1870 – 24 November 1926) was a Russian Soviet politician, engineer, social entrepreneur, Bolshevik revolutionary politician and a Soviet diplomat. In 1 ...

about a convention of monarchists, cadets and right-wing members of the Socialist-Revolutionary Party

The Socialist Revolutionary Party, or the Party of Socialist-Revolutionaries (the SRs, , or Esers, russian: эсеры, translit=esery, label=none; russian: Партия социалистов-революционеров, ), was a major politi ...

in Paris who anticipated an uprising against Bolsheviks in Petrograd. Lenin sent a telegram to Cheka co-founder Józef Unszlicht

Józef Unszlicht or Iosif Stanislavovich Unshlikht (russian: Ио́сиф Станисла́вович У́ншлихт; nicknames "Jurowski", "Leon") (31 December 1879 – 29 July 1938) was a Polish and Russian revolutionary activist, a Soviet go ...

stating that he did not trust the Cheka in Petrograd any longer. In the telegram, he issued an order to urgently send "the most experienced Chekists to Piter" and find the conspirators. This was a signal for the Cheka in Petrograd to fabricate the case.

The case

On May 31, Yuri German, a former officer ofImperial Russian Army

The Imperial Russian Army (russian: Ру́сская импера́торская а́рмия, tr. ) was the armed land force of the Russian Empire, active from around 1721 to the Russian Revolution of 1917. In the early 1850s, the Russian Ar ...

and a Finnish spy, was killed while crossing the Finnish border. He had a notebook with numerous addresses, one of which belonged to professor Vladimir Tagantsev, who was previously identified by Cheka agents as an "disloyal person". Tagantsev and other people whose addresses were found in the notebook were arrested. During the next month the investigators of Cheka worked hard to manufacture the case, but without much success. The arrested refused to admit any guilt. After intense interrogation, Tagantsev tried to hang himself on June 21. In addition, it was difficult to connect together so many completely unrelated people.

On June 25, two investigators of Petrograd Cheka, Gubin and Popov, prepared a report, according to which the "organization included only Tagantsev and a few couriers and supporters," the conspirators planned "to establish common language between intelligentsia and masses," the "terror was not their intention," and German delivered news about current events to Tagantsev from abroad. According to report, "the organization of Tagantsev had no connection and received no support from the Finnish or other counter-intelligence organizations." The report also noted that "Tagantsev is a cabinet scientist who thought about his organization theoretically" and "was incapable of doing practical work." After this report, names of Gubin and Popov disappeared from the case, meaning they have been replaced by other investigators.

After the initial failure,

After the initial failure, Yakov Agranov

Yakov Saulovich Agranov (russian: Я́ков Сау́лович Агра́нов; born Yankel Samuilovich Sorenson; 12 October 1893–1 August 1938) was the first chief of the Soviet Main Directorate of State Security and a deputy of NKVD c ...

was appointed to lead the case. He arrested more people and took Tagantsev for interrogation after keeping him for 45 days in solitary confinement. Agranov gave an ultimatum; if Tagantsev did not confess, then he and all other hostages would be executed after three hours, however, no one would be harmed if he agreed to cooperate. According to publications by Russian emigrants, the agreement was even signed on paper and personally guaranteed by Vyacheslav Menzhinsky

Vyacheslav Rudolfovich Menzhinsky (russian: Вячесла́в Рудо́льфович Менжи́нский, pl, Wiesław Mężyński; 19 August 1874 – 10 May 1934) was a Polish-Russian Bolshevik revolutionary, Soviet statesman and Communist ...

. After signing the agreement, Tagantsev called names of several hundred people who criticized the Bolshevik regime. All of them were arrested on July 31 and during the first days of August.

According to official version invented by Agranov, the leaders of conspiracy included Tagantsev, Finnish spy German, and former colonel of Russian army Vycheslav Shvedov who acted under pseudonym "Vyacheslavsky" and shot two Chekists during his arrest. To make the conspiracy bigger, they included many completely unrelated people, including former aristocrats, contrabandists, suspicious people and wives of those who were already arrested. The newspaper ''The Petrograd Pravda'' published a report by the Petrograd Cheka that the military organization of Tagantsev planned to burn plants, kill people and commit other terrorism acts using weapons and dynamite.

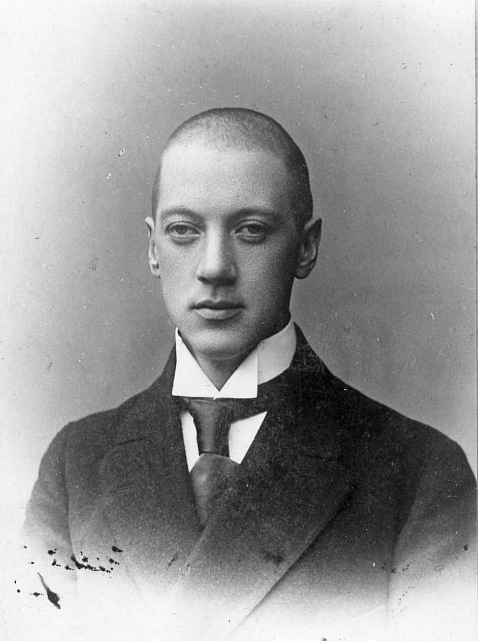

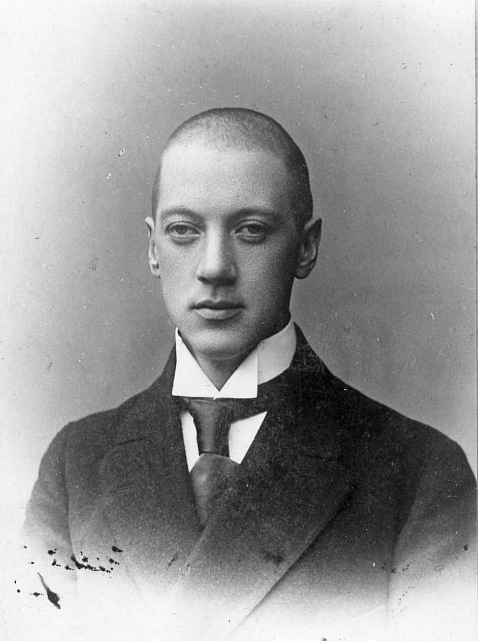

The most famous victim of the case was the poet

The most famous victim of the case was the poet Nikolay Gumilev

Nikolay Stepanovich Gumilyov ( rus, Никола́й Степа́нович Гумилёв, p=nʲɪkɐˈlaj sʲtʲɪˈpanəvʲɪtɕ ɡʊmʲɪˈlʲɵf, a=Nikolay Styepanovich Gumilyov.ru.vorb.oga; April 15 NS 1886 – August 26, 1921) was a poe ...

. Gumilev was arrested by Cheka on August 3. He admitted that he thought about joining the Kronstadt rebellion if it were to spread to Petrograd and talked about this with Vyacheslavsky. Gumilev was executed by a firing squad, together with 60 other people on August 24 in the Kovalevsky Forest. Thirty-seven others were shot on October 3.Shentalinsky, page 278.Vadim J. Birstein, ''The Perversion Of Knowledge: The True Story of Soviet Science'', Westview Press (2004) , pages 28-33. Agranov commented about the operation: "Seventy percent of the Petrograd intelligentsia had one leg in the enemy camp. We had to burn that leg."Vitaliy Shentalinsky, page 214.

Aftermath

The action reportedly failed to terrify the population. According to academicianVladimir Vernadsky

Vladimir Ivanovich Vernadsky (russian: link=no, Влади́мир Ива́нович Верна́дский) or Volodymyr Ivanovych Vernadsky ( uk, Володи́мир Іва́нович Верна́дський; – 6 January 1945) was ...

, the case "had a shocking effect and produced not a feeling of fear, but of hatred and contempt" against the Bolsheviks. After the Tagantsev case Lenin decided that it would be easier to exile undesired intellectuals.

See also

*Prompartiya

The Industrial Party Trial (November 25 – December 7, 1930) (russian: Процесс Промпартии, Trial of the ''Prompartiya'') was a show trial in which several Soviet scientists and economists were accused and convicted of plottin ...

*Active measures

Active measures (russian: активные мероприятия, translit=aktivnye meropriyatiya) is political warfare conducted by the Soviet or Russian government since the 1920s. It includes offensive programs such as espionage, propaganda ...

*Red terror

The Red Terror (russian: Красный террор, krasnyj terror) in Soviet Russia was a campaign of political repression and executions carried out by the Bolsheviks, chiefly through the Cheka, the Bolshevik secret police. It started in lat ...

*Operation Trust

Operation Trust (Russian: операция "Трест", tr. Operatsiya "Trest") was a counterintelligence operation of the State Political Directorate (GPU) of the Soviet Union. The operation, which was set up by GPU's predecessor Cheka, ran fro ...

* Syndicate-2

References

External links

Vladimir Tagantsev

on memorial book of persecuted geologists

Extended version in Russian)

interview with Yuri Chernyaev on RFERL, and it

summary

{{Authority control False flag operations Political and cultural purges Soviet Union intelligence operations Anti-intellectualism