Ta'abatta Sharran on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Thabit ibn Jabr, better known by his epithet Ta'abbata Sharran (; lived late 6th century or early 7th century CE) was a pre-Islamic Arabic poet of the ''

The dates of Ta'abbata Sharran's life are not known. Based on personal names which occur in poems attributed to him, he likely lived in the late 6th century or early 7th century CE. He lived in the western Arabian regions of

The dates of Ta'abbata Sharran's life are not known. Based on personal names which occur in poems attributed to him, he likely lived in the late 6th century or early 7th century CE. He lived in the western Arabian regions of

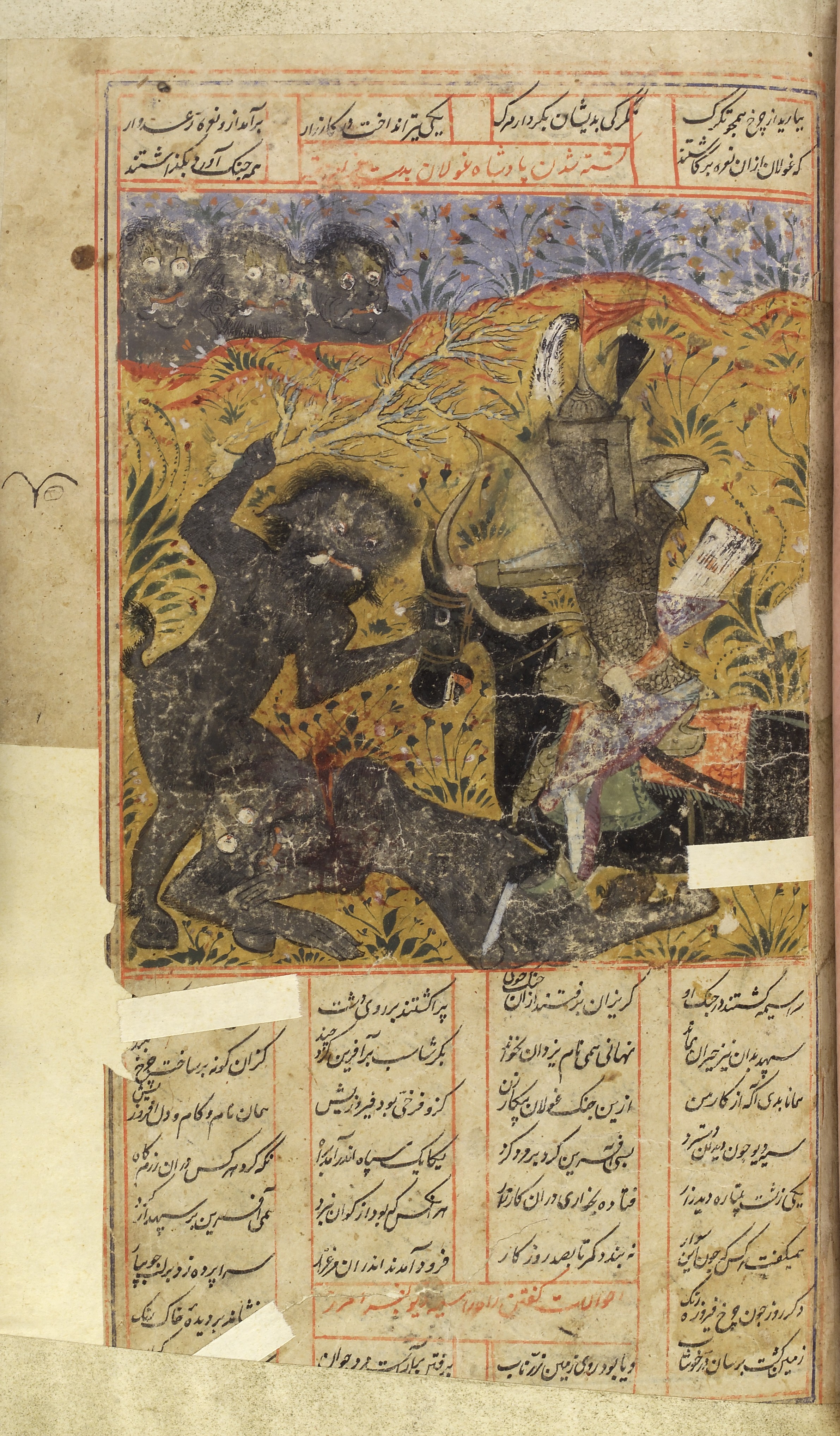

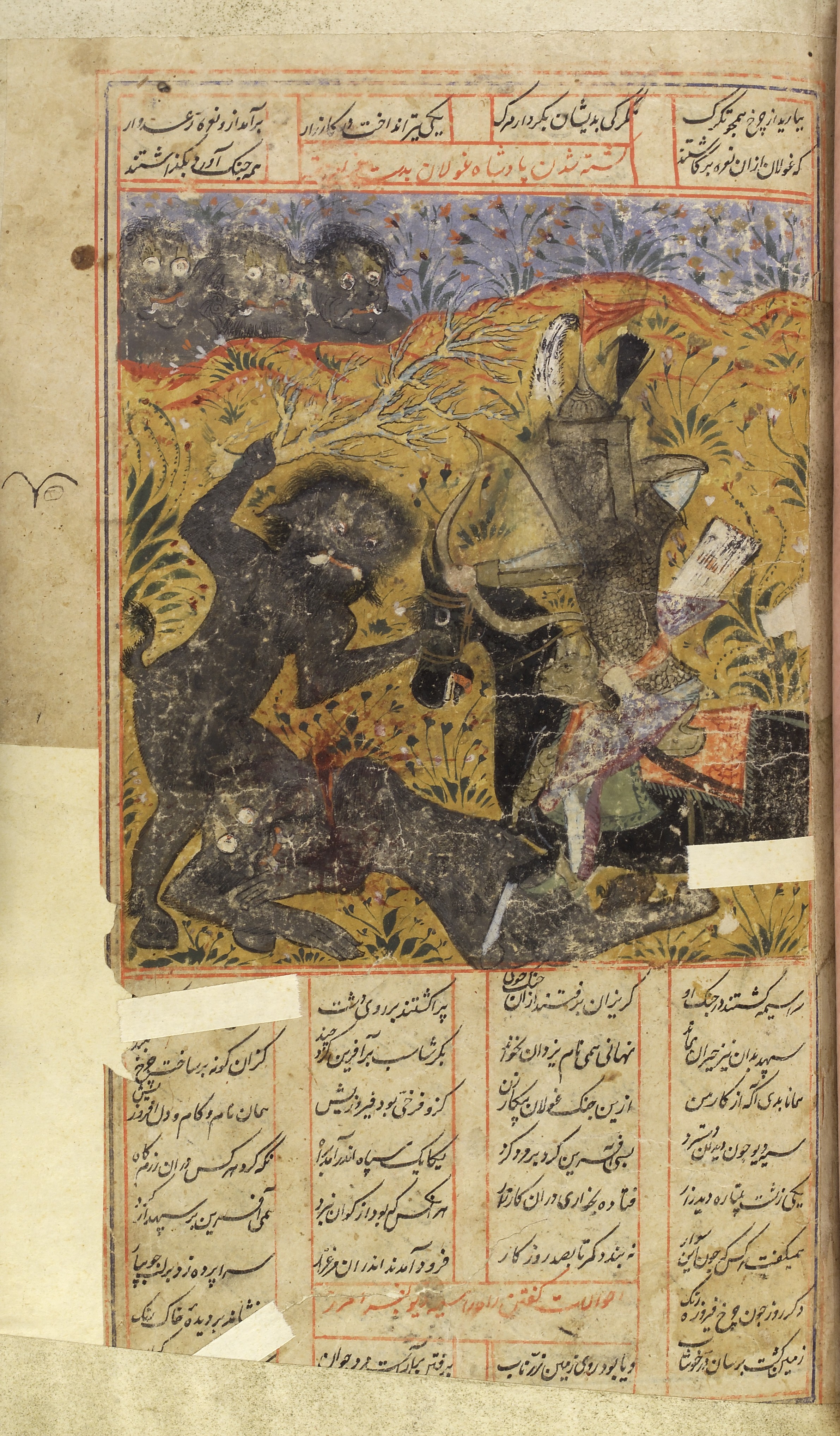

One poem, labelled either "How I Met the Ghul" or the "Qit'a Nuniyya," relates the story of the poet's encounter with a ghul. He was travelling at night in the territory of the Banu Hudhayl, when a ghul stepped in his way. He fought the ghul and killed her, then spent the night on top of her. In the morning he carried her under his arm and showed her to his friends: "Two eyes set in a hideous head, like the head of a cat, split-tongued, legs like a deformed fetus, the back of a dog." The structure of the poem parodies Arabic love poems in which lovers meet at night in the desert. In another, titled "Sulayma Says to Her Neighbor Women", he meets a ghul and attempts to have sex with her, but she writhes and reveals her horrible face, which prompts him to cut her head off. Further examples of his work can be found in poems VIII and IX of the ''Hamasah''.

One poem, labelled either "How I Met the Ghul" or the "Qit'a Nuniyya," relates the story of the poet's encounter with a ghul. He was travelling at night in the territory of the Banu Hudhayl, when a ghul stepped in his way. He fought the ghul and killed her, then spent the night on top of her. In the morning he carried her under his arm and showed her to his friends: "Two eyes set in a hideous head, like the head of a cat, split-tongued, legs like a deformed fetus, the back of a dog." The structure of the poem parodies Arabic love poems in which lovers meet at night in the desert. In another, titled "Sulayma Says to Her Neighbor Women", he meets a ghul and attempts to have sex with her, but she writhes and reveals her horrible face, which prompts him to cut her head off. Further examples of his work can be found in poems VIII and IX of the ''Hamasah''.

Text of Poems (Arabic) at Poets Gate

6th-century Arabic poets 7th-century Arabic poets

su'luk In early Arabian history, su'luk ( ar, صعلوك; pl. sa'alik ) was a term that can be translated as brigand, brigand-poet, or vagabond. The sa'alik were mostly individuals who had been forced out of their tribes and who lived on the fringes of soc ...

'' (vagabond) school. He lived in the Arabian Peninsula

The Arabian Peninsula, (; ar, شِبْهُ الْجَزِيرَةِ الْعَرَبِيَّة, , "Arabian Peninsula" or , , "Island of the Arabs") or Arabia, is a peninsula of Western Asia, situated northeast of Africa on the Arabian Plate ...

near the city of Ta'if

Taif ( ar, , translit=aṭ-Ṭāʾif, lit=The circulated or encircled, ) is a city and governorate in the Makkan Region of Saudi Arabia. Located at an elevation of in the slopes of the Hijaz Mountains, which themselves are part of the Sarat M ...

, and was a member of the tribe. He was known for engaging in tribal conflict with the Banu Hudhayl and Bajila tribes. He wrote poems about tribal warfare, the hardships of desert life, and ghouls. His work was prominent in the early poetic anthologies, being preserved in both the '' Mufaddaliyat'' (8th century) and the ''Hamasah

The Hamasah (; ) is a genre of Arabic poetry that "recounts chivalrous exploits in the context of military glories and victories".

The first work in this genre is Kitab al-Hamasah of Abu Tammam.

Hamasah works

List of popular Hamasah works:

* ''Ha ...

'' (9th century). Details of his life are known only from pseudo-historical accounts in the poetic anthologies and the '' Kitab al-Aghani''.

Name

His proper name was Thabit ibn Jabr al-Fahmi. Al-Fahmi is a ''nisba

The Arabic word nisba (; also transcribed as ''nisbah'' or ''nisbat'') may refer to:

* Nisba, a suffix used to form adjectives in Arabic grammar, or the adjective resulting from this formation

**comparatively, in Afro-Asiatic: see Afroasiatic_lang ...

'' indicating his membership in the Fahm tribe. Ta'abatta Sharran is a '' laqab,'' or nickname, which means "he who has put evil in his armpit."

There are a number of traditional accounts of how he acquired the name, related in the '' Kitab al-Aghani''. In one, he saw a ram in the desert. He picked it up and carried it under his arm, but it urinated on him. It became heavier as he approached his camp, so he dropped it, and saw that in fact it was a ghul

A ghoul ( ar, غول, ') is a demon-like being or monstrous humanoid. The concept originated in pre-Islamic Arabian religion, associated with graveyards and the consumption of human flesh. Modern fiction often uses the term to label a certa ...

. His clan asked him what he had been carrying, and he replied "the ghul," which prompted them to give him his nickname. In another, during truffle season, his mother asked why he was not gathering truffles for the family. He went out with her bag and filled it with snakes, then returned to the tent carrying the bag under his arm. He threw the bag down in front of her and she opened it, finding the snakes, then fled the tent. When she told the story to the women of the tribe, they gave Thabit his nickname. Another story has it that his mother gave him the name because he habitually carried his sword under his arm when travelling with a raiding party. Modern scholars believe that these traditions "should not be taken at face value," and that the name was intended to signify the poet's unavoidable propensity for trouble.

Life

The dates of Ta'abbata Sharran's life are not known. Based on personal names which occur in poems attributed to him, he likely lived in the late 6th century or early 7th century CE. He lived in the western Arabian regions of

The dates of Ta'abbata Sharran's life are not known. Based on personal names which occur in poems attributed to him, he likely lived in the late 6th century or early 7th century CE. He lived in the western Arabian regions of Tihama

Tihamah or Tihama ( ar, تِهَامَةُ ') refers to the Red Sea coastal plain of the Arabian Peninsula from the Gulf of Aqaba to the Bab el Mandeb.

Etymology

Tihāmat is the Proto-Semitic language's term for 'sea'. Tiamat (or Tehom, in masc ...

and the Hejaz

The Hejaz (, also ; ar, ٱلْحِجَاز, al-Ḥijāz, lit=the Barrier, ) is a region in the west of Saudi Arabia. It includes the cities of Mecca, Medina, Jeddah, Tabuk, Yanbu, Taif, and Baljurashi. It is also known as the "Western Provin ...

, near the city of Ta'if

Taif ( ar, , translit=aṭ-Ṭāʾif, lit=The circulated or encircled, ) is a city and governorate in the Makkan Region of Saudi Arabia. Located at an elevation of in the slopes of the Hijaz Mountains, which themselves are part of the Sarat M ...

.

His mother was Amima al-Fahmia, of the Banu al-Qayn Banū al-Qayn () (also spelled Banūʾl Qayn, Balqayn or al-Qayn ibn Jasr) were an Arab tribe that was active between the early Roman era in the Near East through the early Islamic era (7th–8th centuries CE), as far as the historical record is con ...

. After the death of his father Jabr, his mother married one of his enemies, . Ta'abbata Sharran himself married a woman of the Banu Kilab.

He lived as a ''su'luk'' (plural ''sa'alik''), a term which can be translated as brigand, brigand-poet, or vagabond. The ''sa'alik'' were mostly individuals who had been forced out of their tribes and who lived on the fringes of society. Some of the ''sa'alik'' became renowned poets, writing poetry about the hardships of desert life and their feelings of isolation. However, scholar Albert Arazi notes that due to a lack of contemporary documents about the ''sa'alik'', knowledge of them is uncertain and "it is not at all easy to unravel the problem posed by the existence of this group."

Ta'abbata Sharran was one of the few ''su'luk'' poets who was not repudiated by his tribe. He lived as a brigand

Brigandage is the life and practice of highway robbery and plunder. It is practiced by a brigand, a person who usually lives in a gang and lives by pillage and robbery.Oxford English Dictionary second edition, 1989. "Brigand.2" first recorded usa ...

, accompanied by a band of men including Al-Shanfara Al-Shanfarā ( ar, الشنفرى; died c. 525 CE) was a semi-legendary pre-Islamic poet tentatively associated with Ṭāif, and the supposed author of the celebrated poem '' Lāmiyyāt ‘al-Arab''. He enjoys a status as a figure of an archetypa ...

, Amir ibn al-Akhnas, al-Musayyab ibn Kilab, Murra ibn Khulayf, Sa'd ibn al-Ashras, and 'Amr ibn Barrak. The band primarily raided the tribes of Bajila, Banu Hudhayl, Azd

The Azd ( ar, أَزْد), or ''Al-Azd'' ( ar, ٱلْأَزْد), are a tribe of Sabaean Arabs.

In ancient times, the Sabaeans inhabited Ma'rib, capital city of the Kingdom of Saba' in modern-day Yemen. Their lands were irrigated by the Ma ...

, and Khath'am, and evaded pursuit by hiding in the Sarawat Mountains

The Sarawat Mountains ( ar, جِبَالُ ٱلسَّرَوَاتِ, Jibāl as-Sarawāt), also known as the Sarat, is a part of the Hijaz mountains in the western part of the Arabian Peninsula. In a broad sense, it runs parallel to the eastern c ...

. Narratives of his life are found in several literary sources beginning in the 8th century, and include stylized accounts of his exploits such as him pouring honey on a mountain in order to slide to safety after a raid.

The poet was eventually killed during a raid against the Banu Hudhayl, and his body was thrown into a cave called al-Rakhman.

Poetry

Ta'abbata Sharran's poetic diwan consists of 238 verses divided into 32 poems and fragments. Typical of the ''su'luk'' poets, his work expresses strident individuality and a rejection of tribal values.Qasida Qafiyya

Ta'abbata Sharran's " Qasida Qafiyya" is the opening poem of the '' Mufaddaliyat'', an important collection of early Arabic poetry. According to the Italian orientalistFrancesco Gabrieli

Francesco Gabrieli (27 April 1904, in Rome – 13 December 1996, in Rome) was counted among the most distinguished Italian Arabists together with Giorgio Levi Della Vida and Alessandro Bausani, of whom he was respectively a student and collea ...

, the Qafiyya may not have been written as a single poem, but might instead be a collection of Ta'abbata Sharran's verses compiled by later editors.

The opening lines of the Qafiyya are as follows:

This poem follows the traditional structure of the ''qasida'', which consists of three sections: a nostalgic prelude, a description of a camel journey, and then the message or motive of the poem. However, the poet subverts this structure in order to express "the ideal of perpetual marginality". The poem also contains several lines devoted to ''fakhr'' (boasting) about the poet's fleetness of foot, starting with line 4: "I escape rom her

Rom, or ROM may refer to:

Biomechanics and medicine

* Risk of mortality, a medical classification to estimate the likelihood of death for a patient

* Rupture of membranes, a term used during pregnancy to describe a rupture of the amniotic sac

* ...

as I escaped from the Bajila, when I ran at top speed on the night of the sandy tract at al-Raht." The incident to which this line refers is explained in three different stories in the ''Kitab al-Aghani'', which differ in their details but have to do with the poet being captured by the Bajila during a raid and using a ruse to escape. Ta'abbata Sharran, along with al-Shanfara and 'Amr ibn Barraq, was famous for being a fast runner.

Charles Lyall translated the poem into English in 1918.

Qasida Lamiyya

The "Qasida Lamiyya," transmitted in the 9th-century ''Hamasah

The Hamasah (; ) is a genre of Arabic poetry that "recounts chivalrous exploits in the context of military glories and victories".

The first work in this genre is Kitab al-Hamasah of Abu Tammam.

Hamasah works

List of popular Hamasah works:

* ''Ha ...

'' of Abu Tammam, is considered to be another of the poet's major works. However, the authenticity of this poem is doubtful. Al-Tibrizi, a major commentator on the ''Hamasa'', believed that the true author was the '' rāwī'' (reciter) , while the Andalusian anthologist Ibn Abd Rabbih

Ibn ʿAbd Rabbih () or Ibn ʿAbd Rabbihi (Ahmad ibn Muhammad ibn `Abd Rabbih) (860–940) was an arab writer and poet widely known as the author of '' Al-ʿIqd al-Farīd'' (''The Unique Necklace'').

Biography

He was born in Cordova, now in Spain ...

attributed it to a nephew of Ta'abbata Sharran. Contemporary scholar Alan Jones concluded that it may be a mixture of authentic and inauthentic material. The poem is a ''rithā'

Rithā’ ( ar, رثاء) is a genre of Arabic poetry corresponding to elegy or lament

A lament or lamentation is a passionate expression of grief, often in music, poetry, or song form. The grief is most often born of regret, or mourning. La ...

'' (elegy) on the death of the poet's uncle, slain on a mountain path by the Banu Hudhyal. The poet describes his vengeance on the Banu Hudhayl, in what scholar Suzanne Stetkevych calls "the most famous Arabic poem of blood vengeance."

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German poet, playwright, novelist, scientist, statesman, theatre director, and critic. His works include plays, poetry, literature, and aesthetic criticism, as well as trea ...

admired the poem greatly, and included a German translation of it in the "Notes and Queries" section of his 1819 work ''West–östlicher Divan

' (; ''West–Eastern Diwan'') is a diwan, or collection of lyrical poems, by the German poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. It was inspired by the Persian poet Hafez.

Composition

''West–Eastern Diwan'' was written between 1814 and 1819, the ...

''. Goethe's translation was based on Latin translations by Georg Freytag

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Freytag (19 September 1788 – 16 November 1861) was a German philologist.

Background

Freytag was born in Lüneburg. He studied philology and theology at the University of Göttingen, where from 1811 to 1813 he worke ...

and Johann David Michaelis

Johann David Michaelis (27 February 1717 – 22 August 1791) was a Prussian biblical scholar and teacher. He was member of a family that was committed to solid discipline in Hebrew and the cognate languages, which distinguished the University ...

. Other translations include those of Charles Lyall into English (1930), Suzanne Stetkevych into English (1986), and Pierre Larcher into French (2012).

Other work

One poem, labelled either "How I Met the Ghul" or the "Qit'a Nuniyya," relates the story of the poet's encounter with a ghul. He was travelling at night in the territory of the Banu Hudhayl, when a ghul stepped in his way. He fought the ghul and killed her, then spent the night on top of her. In the morning he carried her under his arm and showed her to his friends: "Two eyes set in a hideous head, like the head of a cat, split-tongued, legs like a deformed fetus, the back of a dog." The structure of the poem parodies Arabic love poems in which lovers meet at night in the desert. In another, titled "Sulayma Says to Her Neighbor Women", he meets a ghul and attempts to have sex with her, but she writhes and reveals her horrible face, which prompts him to cut her head off. Further examples of his work can be found in poems VIII and IX of the ''Hamasah''.

One poem, labelled either "How I Met the Ghul" or the "Qit'a Nuniyya," relates the story of the poet's encounter with a ghul. He was travelling at night in the territory of the Banu Hudhayl, when a ghul stepped in his way. He fought the ghul and killed her, then spent the night on top of her. In the morning he carried her under his arm and showed her to his friends: "Two eyes set in a hideous head, like the head of a cat, split-tongued, legs like a deformed fetus, the back of a dog." The structure of the poem parodies Arabic love poems in which lovers meet at night in the desert. In another, titled "Sulayma Says to Her Neighbor Women", he meets a ghul and attempts to have sex with her, but she writhes and reveals her horrible face, which prompts him to cut her head off. Further examples of his work can be found in poems VIII and IX of the ''Hamasah''.

Legacy

A famous elegy in the ''Hamasah'' may refer to Ta'abbata Sharran. The author is unknown but is typically taken to be either Ta'abbata Sharran's mother or the mother of another ''su'luk'', . The poem emphasizes the role of fate: He was also mocked in a humorous ''hija (lampoon) poem written by Qays ibn 'Azarah of the Banu Hudhayl, involving an incident in which Qays was captured by the Fahm and bargained for his life with Ta'abbata Sharran and his wife. In the poem Qays referred to Ta'abbata Sharran by the nickname Sha'l (firebrand), and his wife by the '' kunya'' Umm Jundab (mother of Jundab): He also appeared as a character in the ''Resalat Al-Ghufran

(), meaning ''The Epistle of Forgiveness'', is a satirical work of Arabic poetry written by Abu al-ʿAlaʾ al-Maʿarri around 1033 CE. It has been claimed that the has had an influence on, or has even inspired, Dante Alighieri's ''Divine Comed ...

'', written by Al-Ma'arri around 1033. During an imagined tour of hell, a Sheikh who criticized al-Ma'arri encounters Ta'abbata Sharran along with al-Shanfara, and asks him if he really married a ghul. Ta'abbata Sharran replies only, "All men are liars."

When Oriental studies

Oriental studies is the academic field that studies Near Eastern and Far Eastern societies and cultures, languages, peoples, history and archaeology. In recent years, the subject has often been turned into the newer terms of Middle Eastern studi ...

became popular in Europe in the 19th century, scholars such as Silvestre de Sacy

Antoine Isaac, Baron Silvestre de Sacy (; 21 September 175821 February 1838), was a French nobleman, linguist and orientalist. His son, Ustazade Silvestre de Sacy, became a journalist.

Life and works

Early life

Silvestre de Sacy was born in Pa ...

and Caussin de Perceval Caussin may refer to:

* Armand-Pierre Caussin de Perceval (1795–1871), French orientalist

* Jean-Jacques-Antoine Caussin de Perceval

Jean-Jacques-Antoine Caussin de Perceval (24 June 1759 – 29 July 1835) was an 18th–19th-century French ori ...

introduced ''su'luk'' poetry to a Western audience. They wrote first about al-Shanfara, whose ''Lamiyyat al-'Arab

The ''Lāmiyyāt al-‘Arab'' (the L-song of the Arabs) is the pre-eminent poem in the surviving canon of the pre-Islamic 'brigand-poets' ('' sa'alik''). The poem also gained a foremost position in Western views of the Orient from the 1820s onwards ...

'' is the most famous ''su'luk'' poem. Interest in al-Shanfara led naturally to his associate Ta'abbata Sharran, who became known and appreciated in Europe during the 19th century. In the 20th century, Arab critics began to display renewed interest in ''su'luk'' poetry, and the influential Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

n poet and critic Adunis praised the works of Ta'abbata Sharran and al-Shanfara as quintessential specimens of "the literature of rejection."

Editions

*Notes

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

{{Wikisourcelang, ar, تصنيف:ثابت بن جابر, Ta'abbata SharranText of Poems (Arabic) at Poets Gate

6th-century Arabic poets 7th-century Arabic poets