T. R. Malthus on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Thomas Robert Malthus (; 13/14 February 1766 – 29 December 1834) was an English

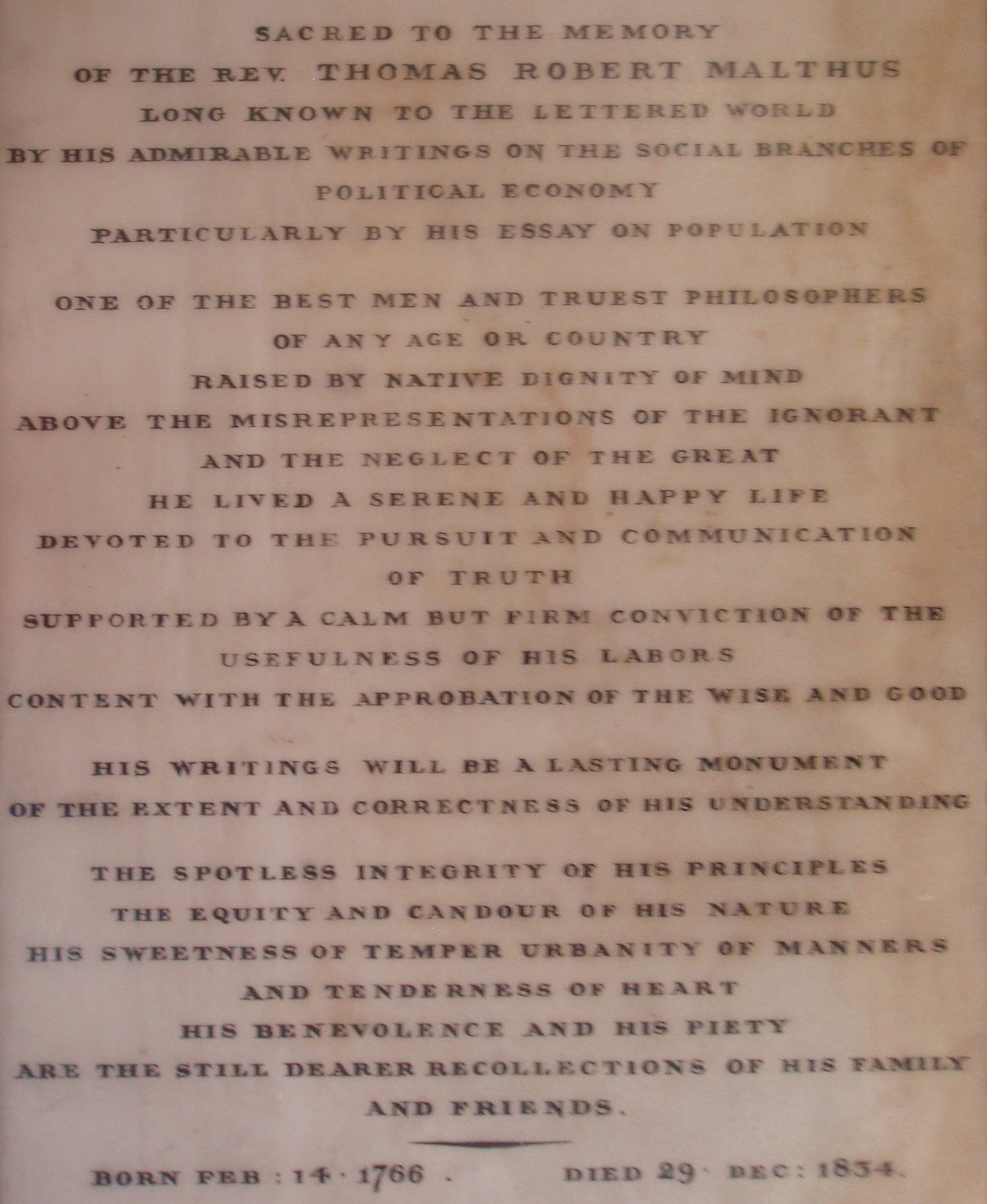

The epitaph of Malthus in Bath Abbey reads ith commas inserted for clarity

The epitaph of Malthus in Bath Abbey reads ith commas inserted for clarity

Abstract.

* Elwell, Frank W. 2001. ''A commentary on Malthus's 1798 Essay on Population as social theory''. Mellon Press. * Evans, L.T. 1998. ''Feeding the ten billion – plants and population growth''. Cambridge University Press. Paperback, 247 pages. * Klaus Hofmann: Beyond the Principle of Population. Malthus' Essay. In: The European Journal of the History of Economic Thought. Bd. 20 (2013), H. 3, S. 399–425, . * Hollander, Samuel 1997. ''The Economics of Thomas Robert Malthus''. University of Toronto Press. Dedicated to Malthus by the author. . * James, Patricia. ''Population Malthus: his life and times''. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. 1979. * Malthus, Thomas Robert. ''Definitions in Political Economy''. Edited by Alexander K Bocast. Critical edition. McLean: Berkeley Bridge Press, 2016. . * Peterson, William 1999. ''Malthus, founder of modern demography'' 2nd ed. Transaction. . * Rohe, John F., ''A Bicentennial Malthusian Essay: conservation, population and the indifference to limits'', Rhodes & Easton, Traverse City, MI. 1997 * Sowell, Thomas, ''The General Glut Controversy Reconsidered'', Oxford Economic Papers New Series, Vol. 15, No. 3 (November 1963), pp. 193–203. Published by: Oxford University Press. Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2661714 *

excerpt

also

online review

* Elwell, Frank W. 2001. ''A Commentary on Malthus' 1798 Essay on Population as social theory''

commentary

* *

a collection of essays for the Malthus Bicentenary

a collection of essays for the Malthus Bicentenary Conference, 1998 * ''Conceptual origins of Malthus's Essay on Population'', facsimile reprint of 8 Books in 6 volumes, edited by Yoshinobu Nanagita () www.aplink.co.jp/ep/4-902454-14-9.htm * National Geographic Magazine, June 2009 article, "The Global Food Crisis

More Food for More People But Not For All, and Not Forever

' United Nations Population Fund website ot found

The Feast of Malthus

by

The International Society of Malthus

from ''Darwin's Metaphor: Nature's Place in Victorian Culture'' by Professor Robert M. Young (1985, 1988, 1994). Cambridge University Press. * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Malthus, Thomas Robert 1766 births 1834 deaths 18th-century British economists 18th-century English Anglican priests 18th-century essayists 18th-century English male writers 19th-century British economists 19th-century English writers 19th-century essayists 19th-century male writers Alumni of Jesus College, Cambridge Anglican writers British demographers British East India Company people Christian writers Classical economists English essayists English eugenicists English male non-fiction writers English religious writers Charles Darwin English theologians Fellows of Jesus College, Cambridge Fellows of the Royal Society Green thinkers History of evolutionary biology Male essayists Non-fiction environmental writers People from Bramcote People from Mole Valley (district) Proto-evolutionary biologists Sustainability advocates Theoretical historians

cleric

Clergy are formal leaders within established religions. Their roles and functions vary in different religious traditions, but usually involve presiding over specific rituals and teaching their religion's doctrines and practices. Some of the ter ...

, scholar and influential economist in the fields of political economy

Political economy is the study of how Macroeconomics, economic systems (e.g. Marketplace, markets and Economy, national economies) and Politics, political systems (e.g. law, Institution, institutions, government) are linked. Widely studied ph ...

and demography

Demography () is the statistics, statistical study of populations, especially human beings.

Demographic analysis examines and measures the dimensions and Population dynamics, dynamics of populations; it can cover whole societies or groups ...

.

In his 1798 book ''An Essay on the Principle of Population

An, AN, aN, or an may refer to:

Businesses and organizations

* Airlinair (IATA airline code AN)

* Alleanza Nazionale, a former political party in Italy

* AnimeNEXT, an annual anime convention located in New Jersey

* Anime North, a Canadian an ...

'', Malthus observed that an increase in a nation's food production improved the well-being of the population, but the improvement was temporary because it led to population growth, which in turn restored the original per capita

''Per capita'' is a Latin phrase literally meaning "by heads" or "for each head", and idiomatically used to mean "per person". The term is used in a wide variety of social sciences and statistical research contexts, including government statistic ...

production level. In other words, humans had a propensity to utilize abundance

Abundance may refer to:

In science and technology

* Abundance (economics), the opposite of scarcities

* Abundance (ecology), the relative representation of a species in a community

* Abundance (programming language), a Forth-like computer prog ...

for population growth rather than for maintaining a high standard of living

Standard of living is the level of income, comforts and services available, generally applied to a society or location, rather than to an individual. Standard of living is relevant because it is considered to contribute to an individual's quality ...

, a view that has become known as the "Malthusian trap

Malthusianism is the idea that population growth is potentially exponential while the growth of the food supply or other resources is linear, which eventually reduces living standards to the point of triggering a population die off. This event, c ...

" or the "Malthusian spectre". Populations had a tendency to grow until the lower class suffered hardship, want and greater susceptibility to war famine

A famine is a widespread scarcity of food, caused by several factors including war, natural disasters, crop failure, Demographic trap, population imbalance, widespread poverty, an Financial crisis, economic catastrophe or government policies. Th ...

and disease

A disease is a particular abnormal condition that negatively affects the structure or function of all or part of an organism, and that is not immediately due to any external injury. Diseases are often known to be medical conditions that a ...

, a pessimistic view that is sometimes referred to as a Malthusian catastrophe

Malthusianism is the idea that population growth is potentially exponential while the growth of the food supply or other resources is linear, which eventually reduces living standards to the point of triggering a population die off. This event, c ...

. Malthus wrote in opposition to the popular view in 18th-century Europe that saw society as improving and in principle as perfectible.

Malthus saw population growth

Population growth is the increase in the number of people in a population or dispersed group. Actual global human population growth amounts to around 83 million annually, or 1.1% per year. The global population has grown from 1 billion in 1800 to ...

as inevitable whenever conditions improved, thereby precluding real progress towards a utopia

A utopia ( ) typically describes an imaginary community or society that possesses highly desirable or nearly perfect qualities for its members. It was coined by Sir Thomas More for his 1516 book ''Utopia (book), Utopia'', describing a fictional ...

n society: "The power of population is indefinitely greater than the power in the earth to produce subsistence for man." As an Anglican cleric, he saw this situation as divinely imposed to teach virtuous behavior. Malthus wrote that "the increase of population is necessarily limited by subsistence," "population does invariably increase when the means of subsistence increase," and "the superior power of population repress by moral restraint, vice, and misery."

Malthus criticized the Poor Laws

In English and British history, poor relief refers to government and ecclesiastical action to relieve poverty. Over the centuries, various authorities have needed to decide whose poverty deserves relief and also who should bear the cost of hel ...

for leading to inflation rather than improving the well-being of the poor. He supported taxes on grain imports (the Corn Laws

The Corn Laws were tariffs and other trade restrictions on imported food and corn enforced in the United Kingdom between 1815 and 1846. The word ''corn'' in British English denotes all cereal grains, including wheat, oats and barley. They were ...

). His views became influential and controversial across economic, political, social and scientific thought. Pioneers of evolutionary biology

Evolutionary biology is the subfield of biology that studies the evolutionary processes (natural selection, common descent, speciation) that produced the diversity of life on Earth. It is also defined as the study of the history of life fo ...

read him, notably Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended fr ...

and Alfred Russel Wallace

Alfred Russel Wallace (8 January 1823 – 7 November 1913) was a British naturalist, explorer, geographer, anthropologist, biologist and illustrator. He is best known for independently conceiving the theory of evolution through natural se ...

. Malthus's failure to predict the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

was a frequent criticism of his theories.

Malthus laid the "...theoretical foundation of the conventional wisdom that has dominated the debate, both scientifically and ideologically, on global hunger and famines for almost two centuries." He remains a much-debated writer.

Early life and education

Thomas Robert Malthus was the sixth of seven children of Daniel Malthus and Henrietta Catherine, daughter ofDaniel Graham

Daniel Lawrence Graham (born November 16, 1978) is a former American football tight end in the National Football League (NFL). He played college football for the University of Colorado, and was recognized as a consensus All-American. He was ...

, apothecary to kings George II George II or 2 may refer to:

People

* George II of Antioch (seventh century AD)

* George II of Armenia (late ninth century)

* George II of Abkhazia (916–960)

* Patriarch George II of Alexandria (1021–1051)

* George II of Georgia (1072–1089)

* ...

and George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of the two kingdoms on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Br ...

, and granddaughter of Thomas Graham, apothecary to kings George I George I or 1 may refer to:

People

* Patriarch George I of Alexandria ( fl. 621–631)

* George I of Constantinople (d. 686)

* George I of Antioch (d. 790)

* George I of Abkhazia (ruled 872/3–878/9)

* George I of Georgia (d. 1027)

* Yuri Dolgoruk ...

and George II George II or 2 may refer to:

People

* George II of Antioch (seventh century AD)

* George II of Armenia (late ninth century)

* George II of Abkhazia (916–960)

* Patriarch George II of Alexandria (1021–1051)

* George II of Georgia (1072–1089)

* ...

. Henrietta was depicted alongside her siblings in William Hogarth

William Hogarth (; 10 November 1697 – 26 October 1764) was an English painter, engraver, pictorial satirist, social critic, editorial cartoonist and occasional writer on art. His work ranges from realistic portraiture to comic strip-like s ...

's painting, ''The Graham Children

''The Graham Children'' is an oil painting completed by William Hogarth in 1742. It is a group portrait depicting the four children of Daniel Graham (apothecary), Daniel Graham, apothecary to George II of Great Britain, King George II. The younge ...

'' (1742). Malthus was born at The Rookery, a "small elegant mansion" at Westcott, near Dorking

Dorking () is a market town in Surrey in South East England, about south of London. It is in Mole Valley District and the council headquarters are to the east of the centre. The High Street runs roughly east–west, parallel to the Pipp Br ...

in Surrey

Surrey () is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in South East England, bordering Greater London to the south west. Surrey has a large rural area, and several significant urban areas which form part of the Greater London Built-up Area. ...

, which his father had bought- at that time called Chert-gate farm- and converted into "a gentleman's seat"; the family sold it in 1768 and moved to "a less extensive establishment at Albury

Albury () is a major regional city in New South Wales, Australia. It is located on the Hume Highway and the northern side of the Murray River. Albury is the seat of local government for the council area which also bears the city's name – the ...

, not far from Guildford

Guildford ()

is a town in west Surrey, around southwest of central London. As of the 2011 census, the town has a population of about 77,000 and is the seat of the wider Borough of Guildford, which had around inhabitants in . The name "Guildf ...

". Malthus had a cleft lip and palate

A cleft lip contains an opening in the upper lip that may extend into the nose. The opening may be on one side, both sides, or in the middle. A cleft palate occurs when the palate (the roof of the mouth) contains an opening into the nose. The ...

which affected his speech; such birth defects had occurred in previous generations of his family. His friend, the social theorist Harriet Martineau

Harriet Martineau (; 12 June 1802 – 27 June 1876) was an English social theorist often seen as the first female sociologist, focusing on racism, race relations within much of her published material.Michael R. Hill (2002''Harriet Martineau: Th ...

, who was hard of hearing, nevertheless stated that due to his sonorous voice he was the only person she could hear well without her ear trumpet

An ear trumpet is a tubular or funnel-shaped device which collects sound waves and leads them into the ear. They were used as hearing aids, resulting in a strengthening of the sound energy impact to the eardrum and thus improved hearing for a dea ...

. William Petersen

William Louis Petersen (born February 21, 1953) is an American actor and producer. He is best known for his role as Gil Grissom in the CBS drama series ''CSI: Crime Scene Investigation'' (2000–2015), for which he won a Screen Actors Guild Aw ...

and John Maynard Keynes

John Maynard Keynes, 1st Baron Keynes, ( ; 5 June 1883 – 21 April 1946), was an English economist whose ideas fundamentally changed the theory and practice of macroeconomics and the economic policies of governments. Originally trained in ...

describe Daniel Malthus as "a gentleman of good family and independent means .. nda friend of David Hume

David Hume (; born David Home; 7 May 1711 NS (26 April 1711 OS) – 25 August 1776) Cranston, Maurice, and Thomas Edmund Jessop. 2020 999br>David Hume" ''Encyclopædia Britannica''. Retrieved 18 May 2020. was a Scottish Enlightenment philo ...

and Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; 28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) was a Genevan philosopher, writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment throughout Europe, as well as aspects of the French Revolu ...

". Daniel Malthus was son of Sydenham Malthus, who was a clerk of Chancery and director of the South Sea Company

The South Sea Company (officially The Governor and Company of the merchants of Great Britain, trading to the South Seas and other parts of America, and for the encouragement of the Fishery) was a British joint-stock company founded in Ja ...

; he was also "proprietor of several landed properties in the Home Counties

The home counties are the counties of England that surround London. The counties are not precisely defined but Buckinghamshire and Surrey are usually included in definitions and Berkshire, Essex, Hertfordshire and Kent are also often inc ...

and Cambridgeshire

Cambridgeshire (abbreviated Cambs.) is a Counties of England, county in the East of England, bordering Lincolnshire to the north, Norfolk to the north-east, Suffolk to the east, Essex and Hertfordshire to the south, and Bedfordshire and North ...

". Sydenham Malthus's father, Daniel, had been apothecary to King William and later to Queen Anne; Daniel's father, Rev. Robert Malthus, was appointed vicar

A vicar (; Latin: ''vicarius'') is a representative, deputy or substitute; anyone acting "in the person of" or agent for a superior (compare "vicarious" in the sense of "at second hand"). Linguistically, ''vicar'' is cognate with the English pref ...

of Northolt

Northolt is a town in West London, England, spread across both sides of the A40 trunk road. It is west-northwest of Charing Cross and is one of the seven major towns that make up the London Borough of Ealing. It had a population of 30,304 at ...

, Middlesex

Middlesex (; abbreviation: Middx) is a Historic counties of England, historic county in South East England, southeast England. Its area is almost entirely within the wider urbanised area of London and mostly within the Ceremonial counties of ...

(now West London

West London is the western part of London, England, north of the River Thames, west of the City of London, and extending to the Greater London boundary.

The term is used to differentiate the area from the other parts of London: North London ...

) under the regicide Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three Ki ...

, but "evicted at the Restoration

Restoration is the act of restoring something to its original state and may refer to:

* Conservation and restoration of cultural heritage

** Audio restoration

** Film restoration

** Image restoration

** Textile restoration

* Restoration ecology

...

"; he was described as "an ancient divine, a man of strong reason, and mighty in the Scriptures, of great eloquence and fervour, though defective in elocution", due to "a very great impediment in his utterance" which has been concluded to be likely to have been a cleft palate. The young Malthus received his education at the Warrington Academy

Warrington Academy, active as a teaching establishment from 1756 to 1782, was a prominent dissenting academy, that is, a school or college set up by those who dissented from the established Church of England. It was located in Warrington (then p ...

from 1782, where he was taught by Gilbert Wakefield

Gilbert Wakefield (1756–1801) was an English scholar and controversialist. He moved from being a cleric and academic, into tutoring at dissenting academies, and finally became a professional writer and publicist. In a celebrated state trial ...

. Warrington was a dissenting academy

The dissenting academies were schools, colleges and seminaries (often institutions with aspects of all three) run by English Dissenters, that is, those who did not conform to the Church of England. They formed a significant part of England's edu ...

, which closed in 1783. Malthus continued for a period to be tutored by Wakefield at the latter's home in Bramcote

Bramcote is a suburban village in the Broxtowe district of Nottinghamshire, England, between Stapleford and Beeston. It is in Broxtowe parliamentary constituency. The main Nottingham–Derby road today is the A52, Brian Clough Way. Nearby ...

, Nottinghamshire

Nottinghamshire (; abbreviated Notts.) is a landlocked county in the East Midlands region of England, bordering South Yorkshire to the north-west, Lincolnshire to the east, Leicestershire to the south, and Derbyshire to the west. The traditi ...

.

Malthus entered Jesus College, Cambridge

Jesus College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. The college's full name is The College of the Blessed Virgin Mary, Saint John the Evangelist and the glorious Virgin Saint Radegund, near Cambridge. Its common name comes fr ...

, in 1784. While there, he took prizes in English declamation, Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

and Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

, and graduated with honours, Ninth Wrangler in mathematics

Mathematics is an area of knowledge that includes the topics of numbers, formulas and related structures, shapes and the spaces in which they are contained, and quantities and their changes. These topics are represented in modern mathematics ...

. His tutor was William Frend. He took the MA degree in 1791, and was elected a Fellow

A fellow is a concept whose exact meaning depends on context.

In learned or professional societies, it refers to a privileged member who is specially elected in recognition of their work and achievements.

Within the context of higher education ...

of Jesus College two years later. In 1789, he took orders in the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

, and became a curate

A curate () is a person who is invested with the ''care'' or ''cure'' (''cura'') ''of souls'' of a parish. In this sense, "curate" means a parish priest; but in English-speaking countries the term ''curate'' is commonly used to describe clergy w ...

at Oakwood Chapel (also Okewood) in the parish of Wotton, Surrey

Wotton is a well-wooded parish with one main settlement, a small village mostly south of the A25 between Guildford in the west and Dorking in the east. The nearest village with a small number of shops is Westcott. Wotton lies in a narrow vall ...

.

Population growth

Malthus came to prominence for his 1798 publication, ''An Essay on the Principle of Population''. He wrote the original text in reaction to the optimism of his father and his father's associates (notablyJean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; 28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) was a Genevan philosopher, writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment throughout Europe, as well as aspects of the French Revolu ...

) regarding the future improvement of society. He also constructed his case as a specific response to writings of William Godwin

William Godwin (3 March 1756 – 7 April 1836) was an English journalist, political philosopher and novelist. He is considered one of the first exponents of utilitarianism and the first modern proponent of anarchism. Godwin is most famous for ...

(1756–1836) and of the Marquis de Condorcet (1743–1794). His assertions evoked questions and criticism, and between 1798 and 1826 he published six more versions of ''An Essay on the Principle of Population'', updating each edition to incorporate new material, to address criticism, and to convey changes in his own perspectives on the subject.

The Malthusian controversy to which the ''Essay'' gave rise in the decades following its publication tended to focus attention on the birth rate and marriage rates. The neo-Malthusian controversy, comprising related debates of many years later, has seen a similar central role assigned to the numbers of children born.

The goal of Malthusian theory is to explain how population and food production expand, with the latter experiencing arithmetic growth and the former experiencing exponential growth. The key focus here, however, is the relevance of Malthusian theory in the present world. This hypothesis is inapplicable in a number of ways. First, the hypothesis is rendered irrelevant. due to a disregard for technological advancement. This is because food production has increased as a result of technological advancements such as genetically modified organisms (GMOs) Second, the mathematical model employed to formulate the hypothesis is incorrect since it was constrained to England's specific situation. Other findings, such as food production exceeding population increase, may be borne out if the modeling could employ wide locations like Australia The Malthusian hypothesis is also limited by social change about family size as individuals will always prefer a manageable family owing to economic restrictions.

Food production can also outpace population expansion, thanks to the industrial revolution Another limitation of this theory is the belief that overall income is a key factor of population health implying that wealthy countries will have various solutions for their rapidly rising populations The Malthusian theory is also irrelevant because an expanding population can be seen as an increase in available human capacity for boosting food production 0 The static aspect of the Malthusian hypothesis, which is based on the rule of decreasing returns 1 limits its applicability. Finally, Malthusian Theory's failure to determine whether birth rates match death rates hampered its application 2ecause it was possible that the population was not rising as fast as food production due to the presence of deaths.

Travel and further career

In 1799, Malthus made a European tour withWilliam Otter

William Otter (23 October 1768 – 20 August 1840) was the first Principal of King's College, London, who later served as Bishop of Chichester.

Early life

William Otter was born at Cuckney, Nottinghamshire on 23 October 1768, the son of Do ...

, a close college friend, travelling part of the way with Edward Daniel Clarke

Edward Daniel Clarke (5 June 17699 March 1822) was an English clergyman, naturalist, mineralogist, and traveller.

Life

Edward Daniel Clarke was born at Willingdon, Sussex, and educated first at Uckfield School"Anthony Saunders, D.D." in Mark ...

and John Marten Cripps

John Marten Cripps (1780–1853) was an English traveller and antiquarian, a significant collector on a Grand Tour he made during the French Revolutionary Wars.

Life

The son of John Cripps of Sussex, he entered Jesus College, Cambridge as a fellow ...

, visiting Germany, Scandinavia and Russia. Malthus used the trip to gather population data. Otter later wrote a ''Memoir'' of Malthus for the second (1836) edition of his ''Principles of Political Economy''. During the Peace of Amiens

The Treaty of Amiens (french: la paix d'Amiens, ) temporarily ended hostilities between France and the United Kingdom at the end of the War of the Second Coalition. It marked the end of the French Revolutionary Wars; after a short peace it se ...

of 1802 he travelled to France and Switzerland, in a party that included his relation and future wife Harriet.

In 1803, he became rector of Walesby, Lincolnshire

Walesby is a village and civil parish in the West Lindsey district of Lincolnshire, England. The population of the civil parish at the 2011 census was 249. It lies in the Lincolnshire Wolds, north-east from Market Rasen and south from Caist ...

.

In 1805, Malthus became Professor of History and Political Economy at the East India Company College

The East India Company College, or East India College, was an educational establishment situated at Hailey, Hertfordshire, nineteen miles north of London, founded in 1806 to train "writers" (administrators) for the Honourable East India Company ( ...

in Hertfordshire

Hertfordshire ( or ; often abbreviated Herts) is one of the home counties in southern England. It borders Bedfordshire and Cambridgeshire to the north, Essex to the east, Greater London to the south, and Buckinghamshire to the west. For govern ...

. His students affectionately referred to him as "Pop", "Population", or "web-toe" Malthus.

Near the end of 1817, the proposed appointment of Graves Champney Haughton

Sir Graves Chamney Haughton FRS (1788 – 28 August 1849) was a British scholar of Oriental languages.

Life and career

Haughton, the son of a doctor, was educated in England before travelling to India in 1808 to take up a position in Bengal as ...

to the college was made a pretext by Randle Jackson and Joseph Hume

Joseph Hume FRS (22 January 1777 – 20 February 1855) was a Scottish surgeon and Radical MP.Ronald K. Huch, Paul R. Ziegler 1985 Joseph Hume, the People's M.P.: DIANE Publishing.

Early life

He was born the son of a shipmaster James Hume ...

to launch an attempt to close it down. Malthus wrote a pamphlet defending the college, which was reprieved by the East India Company within the same year, 1817.

In 1818, Malthus became a Fellow of the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

.

Malthus–Ricardo debate on political economy

During the 1820s, there took place a setpiece intellectual discussion among the exponents ofpolitical economy

Political economy is the study of how Macroeconomics, economic systems (e.g. Marketplace, markets and Economy, national economies) and Politics, political systems (e.g. law, Institution, institutions, government) are linked. Widely studied ph ...

, often called the Malthus–Ricardo debate after its leading figures, Malthus and theorist of free trade

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. It can also be understood as the free market idea applied to international trade. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold econo ...

David Ricardo

David Ricardo (18 April 1772 – 11 September 1823) was a British Political economy, political economist. He was one of the most influential of the Classical economics, classical economists along with Thomas Robert Malthus, Thomas Malthus, Ad ...

, both of whom had written books with the title ''Principles of Political Economy''. Under examination were the nature and methods of political economy itself, while it was simultaneously under attack from others. The roots of the debate were in the previous decade. In ''The Nature of Rent'' (1815), Malthus had dealt with economic rent

In economics, economic rent is any payment (in the context of a market transaction) to the owner of a factor of production in excess of the cost needed to bring that factor into production. In classical economics, economic rent is any payment m ...

, a major concept in classical economics. Ricardo defined a theory of rent in his ''Principles of Political Economy and Taxation'' (1817): he regarded rent as value in excess of real production—something caused by ownership rather than by free trade. Rent therefore represented a kind of negative money that landlords could pull out of the production of the land, by means of its scarcity. Contrary to this concept, Malthus proposed rent to be a kind of economic surplus

In mainstream economics, economic surplus, also known as total welfare or total social welfare or Marshallian surplus (after Alfred Marshall), is either of two related quantities:

* Consumer surplus, or consumers' surplus, is the monetary gain ...

.

The debate developed over the economic concept of a general glut

In macroeconomics, a general glut is an excess of supply in relation to demand, specifically, when there is more production in all fields of production in comparison with what resources are available to consume (purchase) said production.

This exhi ...

, and the possibility of failure of Say's Law

In classical economics, Say's law, or the law of markets, is the claim that the production of a product creates demand for another product by providing something of value which can be exchanged for that other product. So, production is the source ...

. Malthus laid importance on economic development

In the economics study of the public sector, economic and social development is the process by which the economic well-being and quality of life of a nation, region, local community, or an individual are improved according to targeted goals and o ...

and the persistence of disequilibrium.Sowell, pp. 193–4. The context was the post-war depression; Malthus had a supporter in William Blake

William Blake (28 November 1757 – 12 August 1827) was an English poet, painter, and printmaker. Largely unrecognised during his life, Blake is now considered a seminal figure in the history of the poetry and visual art of the Romantic Age. ...

, in denying that capital accumulation

Capital accumulation is the dynamic that motivates the pursuit of profit, involving the investment of money or any financial asset with the goal of increasing the initial monetary value of said asset as a financial return whether in the form o ...

(saving) was always good in such circumstances, and John Stuart Mill

John Stuart Mill (20 May 1806 – 7 May 1873) was an English philosopher, political economist, Member of Parliament (MP) and civil servant. One of the most influential thinkers in the history of classical liberalism, he contributed widely to ...

attacked Blake on the fringes of the debate.

Ricardo corresponded with Malthus from 1817 about his ''Principles''. He was drawn into considering political economy in a less restricted sense, which might be adapted to legislation and its multiple objectives, by the thought of Malthus. In ''Principles of Political Economy'' (1820) and elsewhere, Malthus addressed the tension, amounting to conflict he saw between a narrow view of political economy and the broader moral and political plane. Leslie Stephen

Sir Leslie Stephen (28 November 1832 – 22 February 1904) was an English author, critic, historian, biographer, and mountaineer, and the father of Virginia Woolf and Vanessa Bell.

Life

Sir Leslie Stephen came from a distinguished intellectua ...

wrote:

If Malthus and Ricardo differed, it was a difference of men who accepted the same first principles. They both professed to interpretIt is now considered that the different purposes seen by Malthus and Ricardo for political economy affected their technical discussion, and contributed to the lack of compatible definitions. For example,Adam Smith Adam Smith (baptized 1723 – 17 July 1790) was a Scottish economist and philosopher who was a pioneer in the thinking of political economy and key figure during the Scottish Enlightenment. Seen by some as "The Father of Economics"——— ...as the true prophet, and represented different shades of opinion rather than diverging sects.

Jean-Baptiste Say

Jean-Baptiste Say (; 5 January 1767 – 15 November 1832) was a liberal French economist and businessman who argued in favor of competition, free trade and lifting restraints on business. He is best known for Say's law—also known as the law of ...

used a definition of production based on goods and services

Goods are items that are usually (but not always) tangible, such as pens, physical books, salt, apples, and hats. Services are activities provided by other people, who include architects, suppliers, contractors, technologists, teachers, doctor ...

and so queried the restriction of Malthus to "goods" alone.

In terms of public policy, Malthus was a supporter of the protectionist

Protectionism, sometimes referred to as trade protectionism, is the economic policy of restricting imports from other countries through methods such as tariffs on imported goods, import quotas, and a variety of other government regulations. ...

Corn Laws

The Corn Laws were tariffs and other trade restrictions on imported food and corn enforced in the United Kingdom between 1815 and 1846. The word ''corn'' in British English denotes all cereal grains, including wheat, oats and barley. They were ...

from the end of the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

. He emerged as the only economist of note to support duties on imported grain. By encouraging domestic production, Malthus argued, the Corn Laws would guarantee British self-sufficiency

Self-sustainability and self-sufficiency are overlapping states of being in which a person or organization needs little or no help from, or interaction with, others. Self-sufficiency entails the self being enough (to fulfill needs), and a self-s ...

in food.

Later life

Malthus was a founding member in 1821 of thePolitical Economy Club

The Political Economy Club is the world's oldest economics association founded by James Mill and a circle of friends in 1821 in London, for the purpose of coming to an agreement on the fundamental principles of political economy. David Ricardo, ...

, where John Cazenove tended to be his ally against Ricardo and Mill. He was elected in the beginning of 1824 as one of the ten royal associates of the Royal Society of Literature

The Royal Society of Literature (RSL) is a learned society founded in 1820, by George IV of the United Kingdom, King George IV, to "reward literary merit and excite literary talent". A charity that represents the voice of literature in the UK, th ...

. He was also one of the first fellows of the Statistical Society, founded in March 1834. In 1827 he gave evidence to a committee of the House of Commons on emigration.

In 1827, he published ''Definitions in Political Economy'' The first chapter put forth "Rules for the Definition and Application of Terms in Political Economy". In chapter 10, the penultimate chapter, he presented 60 numbered paragraphs putting forth terms and their definitions that he proposed should be used in discussing political economy following those rules. This collection of terms and definitions is remarkable for two reasons: first, Malthus was the first economist to explicitly organize, define, and publish his terms as a coherent glossary of defined terms; and second, his definitions were for the most part well-formed definitional statements. Between these chapters, he criticized several contemporary economists—Jean-Baptiste Say

Jean-Baptiste Say (; 5 January 1767 – 15 November 1832) was a liberal French economist and businessman who argued in favor of competition, free trade and lifting restraints on business. He is best known for Say's law—also known as the law of ...

, David Ricardo

David Ricardo (18 April 1772 – 11 September 1823) was a British Political economy, political economist. He was one of the most influential of the Classical economics, classical economists along with Thomas Robert Malthus, Thomas Malthus, Ad ...

, James Mill

James Mill (born James Milne; 6 April 1773 – 23 June 1836) was a Scottish historian, economist, political theorist, and philosopher. He is counted among the founders of the Ricardian school of economics. He also wrote ''The History of British ...

, John Ramsay McCulloch

John Ramsay McCulloch (1 March 1789 – 11 November 1864) was a Scottish economist, author and editor, widely regarded as the leader of the Ricardian school of economists after the death of David Ricardo in 1823. He was appointed the first pr ...

, and Samuel Bailey

Samuel Bailey (5 July 1791 – 18 January 1870) was a British philosopher, economist and writer. He was called the " Bentham of Hallamshire".

Life

Bailey was born at Sheffield on 5 July 1791, the son of Joseph Bailey and Mary Eadon. His father ...

—for sloppiness in choosing, attaching meaning to, and using their technical terms.

McCulloch was the editor of ''The Scotsman'' of Edinburgh and replied cuttingly in a review printed on the front page of his newspaper in March 1827. He implied that Malthus wanted to dictate terms and theories to other economists. McCulloch clearly felt his ox gored, and his review of ''Definitions'' is largely a bitter defence of his own ''Principles of Political Economy'', and his counter-attack "does little credit to his reputation", being largely "personal derogation" of Malthus. The purpose of Malthus's ''Definitions'' was terminological clarity, and Malthus discussed appropriate terms, their definitions, and their use by himself and his contemporaries. This motivation of Malthus's work was disregarded by McCulloch, who responded that there was nothing to be gained "by carping at definitions, and quibbling about the meaning to be attached to" words. Given that statement, it is not surprising that McCulloch's review failed to address the rules of chapter 1 and did not discuss the definitions of chapter 10; he also barely mentioned Malthus's critiques of other writers.

In spite of this and in the wake of McCulloch's scathing review, the reputation of Malthus as economist dropped away for the rest of his life. On the other hand, Malthus did have supporters, including Thomas Chalmers

Thomas Chalmers (17 March 178031 May 1847), was a Scottish minister, professor of theology, political economist, and a leader of both the Church of Scotland and of the Free Church of Scotland. He has been called "Scotland's greatest nine ...

, some of the Oriel Noetics, Richard Jones and William Whewell

William Whewell ( ; 24 May 17946 March 1866) was an English polymath, scientist, Anglican priest, philosopher, theologian, and historian of science. He was Master of Trinity College, Cambridge. In his time as a student there, he achieved dist ...

from Cambridge.

Malthus died suddenly of heart disease

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a class of diseases that involve the heart or blood vessels. CVD includes coronary artery diseases (CAD) such as angina and myocardial infarction (commonly known as a heart attack). Other CVDs include stroke, hea ...

on 23 December 1834 at his father-in-law's house. He was buried in Bath Abbey

The Abbey Church of Saint Peter and Saint Paul, commonly known as Bath Abbey, is a parish church of the Church of England and former Benedictine monastery in Bath, Somerset, England. Founded in the 7th century, it was reorganised in the 10th ...

. His portrait, and descriptions by contemporaries, present him as tall and good-looking, but with a cleft lip and palate

A cleft lip contains an opening in the upper lip that may extend into the nose. The opening may be on one side, both sides, or in the middle. A cleft palate occurs when the palate (the roof of the mouth) contains an opening into the nose. The ...

.

Family

On 13 March 1804, Malthus married Harriet, daughter of John Eckersall of Claverton House, near Bath. They had a son and two daughters. His first born Henry became vicar ofEffingham, Surrey

Effingham is a small English village in the Borough of Guildford in Surrey, reaching from the gently sloping northern plain to the crest of the North Downs and with a medieval parish church. The town has been chosen as the home of notable figur ...

in 1835 and of Donnington, Sussex in 1837; he married Sofia Otter (1807–1889), daughter of Bishop William Otter

William Otter (23 October 1768 – 20 August 1840) was the first Principal of King's College, London, who later served as Bishop of Chichester.

Early life

William Otter was born at Cuckney, Nottinghamshire on 23 October 1768, the son of Do ...

and died in August 1882, aged 76. His middle child Emily died in 1885, outliving her parents and siblings. The youngest Lucille died unmarried and childless in 1825, months before her 18th birthday.

''An Essay on the Principle of Population''

Malthus argued in his ''Essay'' (1798) that population growth generally expanded in times and in regions of plenty until the size of the population relative to the primary resources caused distress: Malthus argued that two types of checks hold population within resource limits: ''positive'' checks, which raise the death rate; and ''preventive'' ones, which lower the birth rate. The positive checks include hunger, disease and war; the preventive checks:birth control

Birth control, also known as contraception, anticonception, and fertility control, is the use of methods or devices to prevent unwanted pregnancy. Birth control has been used since ancient times, but effective and safe methods of birth contr ...

, postponement of marriage and celibacy

Celibacy (from Latin ''caelibatus'') is the state of voluntarily being unmarried, sexually abstinent, or both, usually for religious reasons. It is often in association with the role of a religious official or devotee. In its narrow sense, the ...

.

The rapid increase in the global population of the past century exemplifies Malthus's predicted population patterns; it also appears to describe socio-demographic dynamics of complex pre-industrial societies

Pre-industrial society refers to social attributes and forums of political and cultural organization that were prevalent before the advent of the Industrial Revolution, which occurred from 1750 to 1850. ''Pre-industrial'' refers to a time before ...

. These findings are the basis for neo-Malthusian modern mathematical models of ''long-term historical dynamics''.

Malthus wrote that in a period of resource abundance, a population could double in 25 years. However, the margin of abundance could not be sustained as population grew, leading to checks on population growth:

In later editions of his essay, Malthus clarified his view that if society relied on human misery to limit population growth, then sources of misery (''e.g.'', hunger, disease, and war) would inevitably afflict society, as would volatile economic cycles. On the other hand, "preventive checks" to population that limited birthrates, such as later marriages, could ensure a higher standard of living for all, while also increasing economic stability. Regarding possibilities for freeing man from these limits, Malthus argued against a variety of imaginable solutions, such as the notion that agricultural improvements could expand without limit.

Of the relationship between population and economics, Malthus wrote that when the population of laborers grows faster than the production of food, real wages fall because the growing population causes the cost of living

Cost of living is the cost of maintaining a certain standard of living. Changes in the cost of living over time can be operationalized in a cost-of-living index. Cost of living calculations are also used to compare the cost of maintaining a c ...

(''i.e.'', the cost of food) to go up. Difficulties of raising a family eventually reduce the rate of population growth, until the falling population again leads to higher real wages.

In the second and subsequent editions Malthus put more emphasis on ''moral restraint'' as the best means of easing the poverty of the lower classes."

Editions and versions

* 1798: ''An Essay on the Principle of Population, as it affects the future improvement of society with remarks on the speculations of Mr. Godwin, M. Condorcet, and other writers.''. Anonymously published. * 1803: Second and much enlarged edition: ''An Essay on the Principle of Population; or, a view of its past and present effects on human happiness; with an enquiry into our prospects respecting the future removal or mitigation of the evils which it occasions''. Authorship acknowledged. * 1806, 1807, 1816 and 1826: editions 3–6, with relatively minor changes from the second edition. * 1823: Malthus contributed the article on ''Population'' to the supplement of theEncyclopædia Britannica

The (Latin for "British Encyclopædia") is a general knowledge English-language encyclopaedia. It is published by Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.; the company has existed since the 18th century, although it has changed ownership various time ...

.

* 1830: Malthus had a long extract from the 1823 article reprinted as ''A summary view of the Principle of Population''.

Other works

1800: ''The present high price of provisions''

In this work, his first published pamphlet, Malthus argues against the notion prevailing in his locale that the greed of intermediaries caused the high price of provisions. Instead, Malthus says that the high price stems from thePoor Laws

In English and British history, poor relief refers to government and ecclesiastical action to relieve poverty. Over the centuries, various authorities have needed to decide whose poverty deserves relief and also who should bear the cost of hel ...

, which "increase the parish allowances in proportion to the price of corn." Thus, given a limited supply, the Poor Laws force up the price of daily necessities. However, he concludes by saying that in time of scarcity such Poor Laws, by raising the price of corn more evenly, actually produce a ''beneficial'' effect.

1814: ''Observations on the effects of the Corn Laws''

Although government in Britain had regulated the prices of grain, theCorn Laws

The Corn Laws were tariffs and other trade restrictions on imported food and corn enforced in the United Kingdom between 1815 and 1846. The word ''corn'' in British English denotes all cereal grains, including wheat, oats and barley. They were ...

originated in 1815. At the end of the Napoleonic Wars that year, Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

passed legislation banning the importation of foreign corn into Britain until domestic corn cost 80 shillings per quarter A quarter is one-fourth, , 25% or 0.25.

Quarter or quarters may refer to:

Places

* Quarter (urban subdivision), a section or area, usually of a town

Placenames

* Quarter, South Lanarkshire, a settlement in Scotland

* Le Quartier, a settlement ...

. The high price caused the cost of food to increase and caused distress among the working classes in the towns. It led to serious rioting in London and to the Peterloo Massacre

The Peterloo Massacre took place at St Peter's Field, Manchester, Lancashire, England, on Monday 16 August 1819. Fifteen people died when cavalry charged into a crowd of around 60,000 people who had gathered to demand the reform of parliament ...

in Manchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of Salford to the west. The t ...

in 1819.

In this pamphlet, printed during the parliamentary discussion, Malthus tentatively supported the free-traders. He argued that given the increasing cost of growing British corn, advantages accrued from supplementing it from cheaper foreign sources.

1820: ''Principles of political economy''

In 1820 Malthus published ''Principles of Political Economy

''Principles of Political Economy'' (1848) by John Stuart Mill was one of the most important economics or political economy textbooks of the mid-nineteenth century. It was revised until its seventh edition in 1871, shortly before Mill's death ...

''.

(A second edition was posthumously published in 1836.) Malthus intended this work to rival Ricardo's ''Principles'' (1817). It, and his 1827 ''Definitions in political economy'', defended Sismondi's views on "general glut" rather than Say's Law, which in effect states "there can be no general glut".

Other publications

* 1807. ''A letter to Samuel Whitbread, Esq. M.P. on his proposed Bill for the Amendment of the Poor Laws''. Johnson and Hatchard, London. * 1808. Spence on Commerce. ''Edinburgh Review'' 11, January, 429–448. * 1808. Newneham and others on the state of Ireland. ''Edinburgh Review'' 12, July, 336–355. * 1809. Newneham on the state of Ireland, ''Edinburgh Review'' 14 April, 151–170. * 1811. Depreciation of paper currency. ''Edinburgh Review'' 17, February, 340–372. * 1812. Pamphlets on the bullion question. '' Edinburgh Review'' 18, August, 448–470. * 1813. ''A letter to the Rt. Hon. Lord Grenville''. Johnson, London. * 1817. ''Statement respecting the East-India College''. Murray, London. * 1821. Godwin on Malthus. ''Edinburgh Review'' 35, July, 362–377. * 1823. ''The Measure of Value, stated and illustrated'' * 1823. Tooke – On high and low prices. ''Quarterly Review

The ''Quarterly Review'' was a literary and political periodical founded in March 1809 by London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River ...

'', 29 (57), April, 214–239.

* 1824. Political economy. ''Quarterly Review'' 30 (60), January, 297–334.

* 1829. On the measure of the conditions necessary to the supply of commodities. ''Transactions of the Royal Society of Literature of the United Kingdom''. 1, 171–180. John Murray, London.

* 1829. On the meaning which is most usually and most correctly attached to the term ''Value of a Commodity''. ''Transactions of the Royal Society of Literature of the United Kingdom''. 2, 74–81. John Murray.

Reception and influence

Malthus developed the theory of demand-supply mismatches that he called gluts. Discounted at the time, this theory foreshadowed later work by an admirer,John Maynard Keynes

John Maynard Keynes, 1st Baron Keynes, ( ; 5 June 1883 – 21 April 1946), was an English economist whose ideas fundamentally changed the theory and practice of macroeconomics and the economic policies of governments. Originally trained in ...

.

The vast bulk of continuing commentary on Malthus, however, extends and expands on the "Malthusian controversy" of the early 19th century. In Ireland where (writing to Ricardo

Ricardo is the Spanish and Portuguese cognate of the name Richard. It derived from Proto-Germanic ''*rīks'' 'king, ruler' + ''*harduz'' 'hard, brave'. It may be a given name, or a surname.

People Given name

*Ricardo de Araújo Pereira, Portugu ...

in 1817) Malthus proposed that "to give full effect to the natural resources of the country a great part of the population should be swept from the soil", a comparatively early contribution was ''Observations on the population and resources of Ireland'' (1821) by the polymath and physician Whitely Stokes. Finding fault in Malthus's calculations and juxtapositions--"the possible increase of man in America" measured against "the probable increase in ood

The Ood are an alien species with telepathic abilities from the long-running science fiction series ''Doctor Who''. In the series' narrative, they live in the distant future (circa 42nd century).

The Ood are portrayed as a slave race, natural ...

production in Great Britain"—and insisting upon the advantages mankind derives from "improved industry, improved conveyance, improvements in morals, government and religion", Stokes argued that Ireland's difficulty lay not in her "numbers", but in indifferent government.

In popular culture

*Ebenezer Scrooge

Ebenezer Scrooge () is the protagonist of Charles Dickens's 1843 novella ''A Christmas Carol''. At the beginning of the novella, Scrooge is a cold-hearted miser who despises Christmas. The tale of his redemption by three spirits (the Ghost of ...

from ''A Christmas Carol

''A Christmas Carol. In Prose. Being a Ghost Story of Christmas'', commonly known as ''A Christmas Carol'', is a novella by Charles Dickens, first published in London by Chapman & Hall in 1843 and illustrated by John Leech. ''A Christmas C ...

'' by Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English writer and social critic. He created some of the world's best-known fictional characters and is regarded by many as the greatest novelist of the Victorian e ...

represents the perceived ideas of Malthus, famously illustrated by his explanation as to why he refuses to donate to the poor and destitute: "If they would rather die they had better do it, and decrease the surplus population". In general, Dickens had some Malthusian concerns (evident in ''Oliver Twist

''Oliver Twist; or, The Parish Boy's Progress'', Charles Dickens's second novel, was published as a serial from 1837 to 1839, and as a three-volume book in 1838. Born in a workhouse, the orphan Oliver Twist is bound into apprenticeship with ...

'', '' Hard Times'' and other novels), and he concentrated his attacks on Utilitarianism

In ethical philosophy, utilitarianism is a family of normative ethical theories that prescribe actions that maximize happiness and well-being for all affected individuals.

Although different varieties of utilitarianism admit different charact ...

and many of its proponents, like Jeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham (; 15 February 1748 Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O.S._4_February_1747.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O.S. 4 February 1747">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.htm ...

, whom he thought of, along with Malthus, as unjust and inhumane.

* In ''Brave New World

''Brave New World'' is a dystopian novel by English author Aldous Huxley, written in 1931 and published in 1932. Largely set in a futuristic World State, whose citizens are environmentally engineered into an intelligence-based social hierarch ...

'' by Aldous Huxley

Aldous Leonard Huxley (26 July 1894 – 22 November 1963) was an English writer and philosopher. He wrote nearly 50 books, both novels and non-fiction works, as well as wide-ranging essays, narratives, and poems.

Born into the prominent Huxley ...

, a dystopia

A dystopia (from Ancient Greek δυσ- "bad, hard" and τόπος "place"; alternatively cacotopiaCacotopia (from κακός ''kakos'' "bad") was the term used by Jeremy Bentham in his 1818 Plan of Parliamentary Reform (Works, vol. 3, p. 493). ...

n novel set in a World State

World government is the concept of a single political authority with jurisdiction over all humanity. It is conceived in a variety of forms, from tyrannical to democratic, which reflects its wide array of proponents and detractors.

A world gove ...

which controls reproduction, women wear the "Malthusian belt," containing "the regulation supply of contraceptives."

* In the musical ''Urinetown

''Urinetown: The Musical'' is a satirical comedy musical that premiered in 2001, with music by Mark Hollmann, lyrics by Hollmann and Greg Kotis, and book by Kotis. It satirizes the legal system, capitalism, social irresponsibility, populism, burea ...

'', written by Greg Kotis

Greg Kotis (born 1965/1966) is an American playwright, best known for writing the book and co-writing the lyrics for the musical ''Urinetown''.

Biography

Career

Kotis studied political science at the University of Chicago, where he was a membe ...

and Mark Hollmann

Mark Hollmann is an American composer and lyricist.

Hollmann grew up in Fairview Heights, Illinois, where he graduated from Belleville Township High School East in 1981. He won a 2002 Tony Award and a 2001 Obie Award for his music and lyrics to ...

, the characters live in a society in which a fee must be paid in order to urinate, for a drought has made water incredibly scarce. A revolution starts with a "pee for free" agenda. At the end of the show, the revolution wins but the characters end up dying because water was not being conserved, unlike when the 'pee fee' was in place. The penultimate line is "Hail Malthus!"

*In the film '' Avengers: Infinity War'', the main villain called Thanos

Thanos is a supervillain appearing in American comic books published by Marvel Comics. He was created by writer-artist Jim Starlin, and first appeared in '' The Invincible Iron Man'' #55 ( cover date February 1973). An Eternal– Deviant w ...

appears to be motivated by Malthusian views about population growth, and commits universal mass genocide known as The Blip

The Blip (also known as the Decimation and the Snap) is a major fictional event depicted in the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU) franchise in which half of all living things in the universe, chosen at random, were exterminated by Thanos snappin ...

.

* In ''Xenoblade Chronicles 2

''Xenoblade Chronicles 2'' is a 2017 action role-playing game developed by Monolith Soft and published by Nintendo for the Nintendo Switch. Released on December 1, it is the third installment in ''Xenoblade Chronicles'' and the seventh main ent ...

'', one of the games antagonists, Amalthus, is inspired by Malthus.

* in the song ''rät'' by Penelope Scott

Penelope Scott is an American musician, singer-songwriter, and producer. She has produced all of her own music. After releasing the compilation albums ''Junkyard'' (2020) and ''The Junkyard 2'' (2020), Scott released her debut album, ''Public Vo ...

, Malthus is referenced in the verse "I bit the apple 'cuz I trusted you, But it tastes like Thomas Malthus".

Epitaph

The epitaph of Malthus in Bath Abbey reads ith commas inserted for clarity

The epitaph of Malthus in Bath Abbey reads ith commas inserted for clarity

Sacred to the memory of the Rev THOMAS ROBERT MALTHUS, long known to the lettered world by his admirable writings on the social branches of political economy, particularly by his essay on population. One of the best men and truest philosophers of any age or country, raised by native dignity of mind above the misrepresentations of the ignorant and the neglect of the great, he lived a serene and happy life devoted to the pursuit and communication of truth, supported by a calm but firm conviction of the usefulness of his labors, content with the approbation of the wise and good. His writings will be a lasting monument of the extent and correctness of his understanding. The spotless integrity of his principles, the equity and candour of his nature, his sweetness of temper, urbanity of manners and tenderness of heart, his benevolence and his piety are the still dearer recollections of his family and friends. Born 14 February 1766 – Died 29 December 1834.

See also

*Cornucopian

Cornucopianism is the idea that continued progress and provision of material items for mankind can be met by similarly continued advances in technology. It relies on the belief that there is enough matter and energy on the Earth to provide for the ...

ism, a counter-Malthusian school of thought

* Exponential growth

Exponential growth is a process that increases quantity over time. It occurs when the instantaneous rate of change (that is, the derivative) of a quantity with respect to time is proportional to the quantity itself. Described as a function, a q ...

* Food race

Daniel Clarence Quinn (October 11, 1935 – February 17, 2018) was an American author (primarily, novelist and fabulist), cultural critic, and publisher of educational texts, best known for his novel ''Ishmael'', which won the Turner Tomorrow ...

, a related idea from Daniel Quinn

Daniel Clarence Quinn (October 11, 1935 – February 17, 2018) was an American author (primarily, novelist and fabulist), cultural critic, and publisher of educational texts, best known for his novel ''Ishmael'', which won the Turner Tomorrow ...

* ''The Limits to Growth

''The Limits to Growth'' (''LTG'') is a 1972 report that discussed the possibility of exponential economic and population growth with finite supply of resources, studied by computer simulation. The study used the World3 computer model to simula ...

'', from the Club of Rome

The Club of Rome is a nonprofit, informal organization of intellectuals and business leaders whose goal is a critical discussion of pressing global issues. The Club of Rome was founded in 1968 at Accademia dei Lincei in Rome, Italy. It consists ...

* Hong Liangji

Hong Liangji (, 1746–1809), courtesy names Junzhi () and Zhicun (), was a Chinese scholar, statesman, political theorist, and philosopher. He was most famous for his critical essay to the Jiaqing Emperor, which resulted in his banishment to ...

, China's Malthus

* Human overpopulation

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') are the most abundant and widespread species of primate, characterized by bipedalism and exceptional cognitive skills due to a large and complex brain. This has enabled the development of advanced tools, culture, ...

* Malthusian equilibrium

* Malthusian growth model

A Malthusian growth model, sometimes called a simple exponential growth model, is essentially exponential growth based on the idea of the function being proportional to the speed to which the function grows. The model is named after Thomas Robert ...

* Malthusian trap

Malthusianism is the idea that population growth is potentially exponential while the growth of the food supply or other resources is linear, which eventually reduces living standards to the point of triggering a population die off. This event, c ...

* Malthusianism

Malthusianism is the idea that population growth is potentially exponential while the growth of the food supply or other resources is linear, which eventually reduces living standards to the point of triggering a population die off. This event, c ...

* National Security Study Memorandum 200

National Security Study Memorandum 200: Implications of Worldwide Population Growth for U.S. Security and Overseas Interests (NSSM200), also known as the "Kissinger Report", was a national security directive completed on December 10, 1974 by the ...

* ''Observations Concerning the Increase of Mankind, Peopling of Countries, etc.

''Observations Concerning the Increase of Mankind, Peopling of Countries, etc.'' is a short essay written in 1751 by American polymath Benjamin Franklin. It was circulated by Franklin in manuscript to his circle of friends, but in 1755 it was publ ...

''

* World population

In demographics, the world population is the total number of humans currently living. It was estimated by the United Nations to have exceeded 8 billion in November 2022. It took over 200,000 years of human prehistory and history for the ...

Notes

Walter, R. (2020). Malthus's principle of population in Britain: restatement and antiquation. In Malthus Across Nations. Edward Elgar Publishing. Brooks, J. (2021). Settler Colonialism, Primitive Accumulation, and Biopolitics in Xinjiang, China. Primitive Accumulation, and Biopolitics in Xinjiang, China (September 4, 2021). Mokyr, J. (2018). The past and the future of innovation: Some lessons from economic history. Explorations in Economic History, 69, 13-26. Smith, K. (2013). The Malthusian Controversy. Routledge. Robertson, T. (2012). The Malthusian moment. Rutgers University Press. Malthus, T. R., Winch, D., & James, P. (1992). Malthus: 'An Essay on the Principle of Population'. Cambridge University Press. Kallis, G. (2019). Limits: Why Malthus was wrong and why environmentalists should care. Stanford University Press. Cremaschi, S. (2014). Utilitarianism and Malthus's Virtue Ethics: Respectable, virtuous and happy. Routledge. Chiarini, B., Malanima, P., & Piga, G. (Eds.). (2012). From Malthus' stagnation to sustained growth: social, demographic and economic factors. Palgrave Macmillan. 0The Economist. (2008). Malthus, the false prophet. Retrieved 10 April 2022, from https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2008/05/15/malthus-the-false-prophet 1Patel, R. (2015). 'The End of Plenty,' by Joel K. Bourne Jr. (Published 2015). Retrieved 10 April 2022, from https://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/26/books/review/the-end-of-plenty-by-joel-k-bourne-jr.html 2Shermer, M. (2016). Why Malthus Is Still Wrong. Why Malthus makes for bad science policy. Retrieved 10 April 2022, from https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/why-malthus-is-still-wrong/References

* * Dupâquier, J. 2001. Malthus, Thomas Robert (1766–1834). ''International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences

The ''International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences'', originally edited by Neil J. Smelser and

Paul B. Baltes, is a 26-volume work published by Elsevier. It has some 4,000 signed articles (commissioned by around 50 subject editor ...

'', 9151–56Abstract.

* Elwell, Frank W. 2001. ''A commentary on Malthus's 1798 Essay on Population as social theory''. Mellon Press. * Evans, L.T. 1998. ''Feeding the ten billion – plants and population growth''. Cambridge University Press. Paperback, 247 pages. * Klaus Hofmann: Beyond the Principle of Population. Malthus' Essay. In: The European Journal of the History of Economic Thought. Bd. 20 (2013), H. 3, S. 399–425, . * Hollander, Samuel 1997. ''The Economics of Thomas Robert Malthus''. University of Toronto Press. Dedicated to Malthus by the author. . * James, Patricia. ''Population Malthus: his life and times''. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. 1979. * Malthus, Thomas Robert. ''Definitions in Political Economy''. Edited by Alexander K Bocast. Critical edition. McLean: Berkeley Bridge Press, 2016. . * Peterson, William 1999. ''Malthus, founder of modern demography'' 2nd ed. Transaction. . * Rohe, John F., ''A Bicentennial Malthusian Essay: conservation, population and the indifference to limits'', Rhodes & Easton, Traverse City, MI. 1997 * Sowell, Thomas, ''The General Glut Controversy Reconsidered'', Oxford Economic Papers New Series, Vol. 15, No. 3 (November 1963), pp. 193–203. Published by: Oxford University Press. Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2661714 *

Further reading

* Bashford, Alison, and Joyce E. Chaplin. ''The New Worlds of Thomas Robert Malthus: Rereading the Principle of Population'' (Princeton University Press

Princeton University Press is an independent publisher with close connections to Princeton University. Its mission is to disseminate scholarship within academia and society at large.

The press was founded by Whitney Darrow, with the financial su ...

, 2016). vii + 353 ppexcerpt

also

online review

* Elwell, Frank W. 2001. ''A Commentary on Malthus' 1798 Essay on Population as social theory''

Lewiston, New York

Lewiston is a town in Niagara County, New York, United States. The population was 15,944 at the 2020 census. The town and its contained village are named after Morgan Lewis, a governor of New York.

The Town of Lewiston is on the western bord ...

: Edwin Mellen Press

The Edwin Mellen Press or Mellen Press is an international Independent business, independent company and Academic publisher, academic publishing house with editorial offices in Lewiston (town), New York, Lewiston, New York, and Lampeter, Lampete ...

. .

* Heilbroner, Robert, ''The Worldly Philosophers – the lives, times, and ideas of the great economic thinkers''. (1953)commentary

* *

a collection of essays for the Malthus Bicentenary

a collection of essays for the Malthus Bicentenary Conference, 1998 * ''Conceptual origins of Malthus's Essay on Population'', facsimile reprint of 8 Books in 6 volumes, edited by Yoshinobu Nanagita () www.aplink.co.jp/ep/4-902454-14-9.htm * National Geographic Magazine, June 2009 article, "The Global Food Crisis

External links

* * * * * *More Food for More People But Not For All, and Not Forever

' United Nations Population Fund website ot found

The Feast of Malthus

by

Garrett Hardin

Garrett James Hardin (April 21, 1915 – September 14, 2003) was an American ecologist. He focused his career on the issue of human overpopulation, and is best known for his exposition of the tragedy of the commons in a 1968 paper of the same ti ...

in ''The Social Contract'' (1998)

The International Society of Malthus

from ''Darwin's Metaphor: Nature's Place in Victorian Culture'' by Professor Robert M. Young (1985, 1988, 1994). Cambridge University Press. * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Malthus, Thomas Robert 1766 births 1834 deaths 18th-century British economists 18th-century English Anglican priests 18th-century essayists 18th-century English male writers 19th-century British economists 19th-century English writers 19th-century essayists 19th-century male writers Alumni of Jesus College, Cambridge Anglican writers British demographers British East India Company people Christian writers Classical economists English essayists English eugenicists English male non-fiction writers English religious writers Charles Darwin English theologians Fellows of Jesus College, Cambridge Fellows of the Royal Society Green thinkers History of evolutionary biology Male essayists Non-fiction environmental writers People from Bramcote People from Mole Valley (district) Proto-evolutionary biologists Sustainability advocates Theoretical historians