T. J. Ryan on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

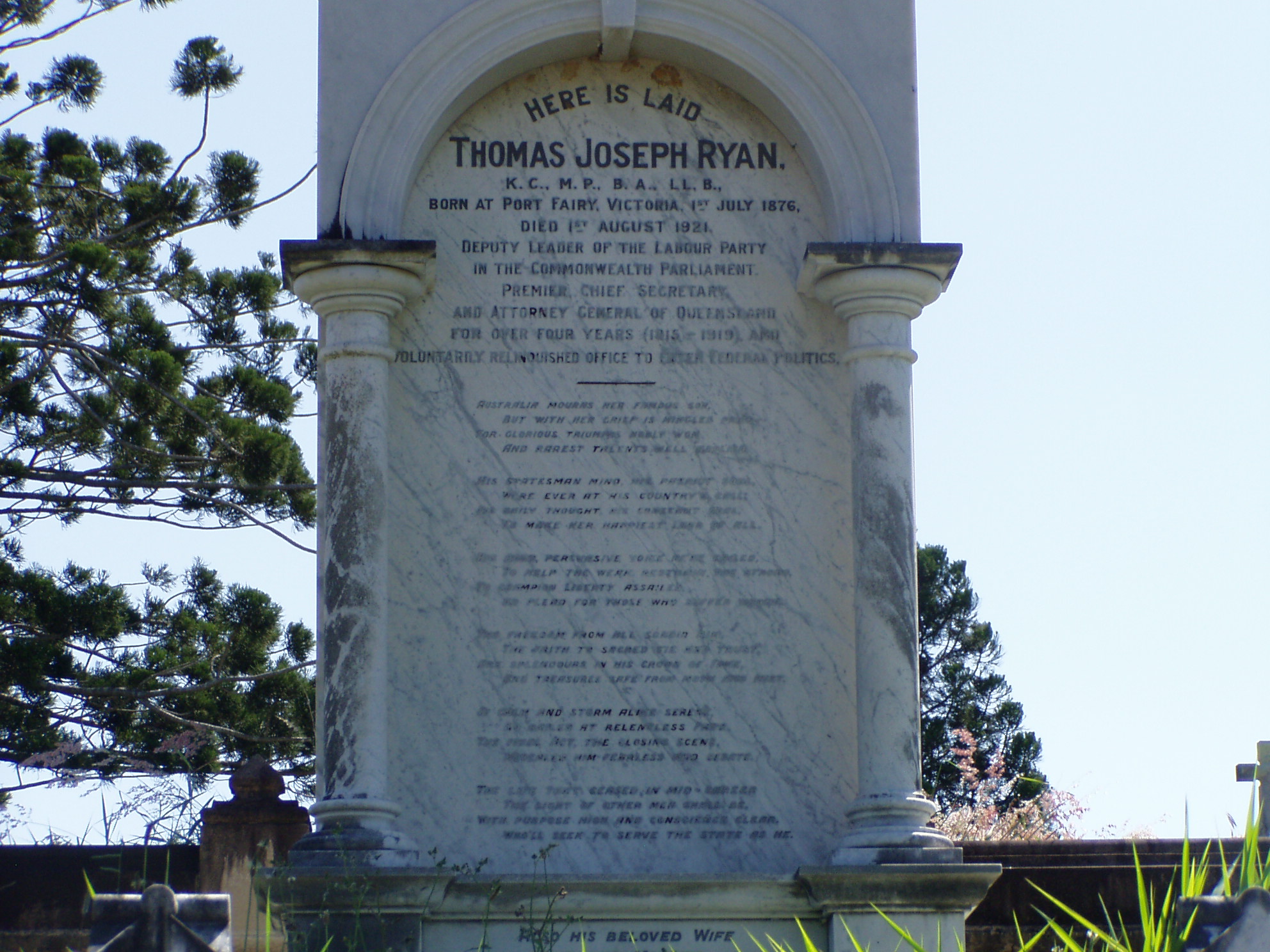

Thomas Joseph Ryan (1 July 1876 – 1 August 1921) was an Australian politician who served as

At the 1903 federal election, Ryan stood unsuccessfully as an

At the 1903 federal election, Ryan stood unsuccessfully as an

— Hearsay – The Journal of the Bar Association of Queensland Although a big man physically, Ryan was not strong in health. Weakened by influenza while he was in England at the time of the

The early death of such a capable leader was a great blow to the Labor movement. Ryan was described as urbane, amiable and approachable, and his personality had allowed him to win the confidence and trust of people in all ranks, from the governor of the

The early death of such a capable leader was a great blow to the Labor movement. Ryan was described as urbane, amiable and approachable, and his personality had allowed him to win the confidence and trust of people in all ranks, from the governor of the

Funeral Hearse of T. J. Ryan at Toowong Cemetery, ca. 1921

—

Stable collection 1917 – 1991: treasure collection of the John Oxley Library

- John Oxley Library blog, State Library of Queensland. {{DEFAULTSORT:Ryan, Thomas Joseph 1876 births 1921 deaths Premiers of Queensland Australian Labor Party members of the Parliament of Australia Members of the Australian House of Representatives Members of the Australian House of Representatives for West Sydney People from Port Fairy Burials at Toowong Cemetery People educated at Xavier College Melbourne Law School alumni Leaders of the Opposition in Queensland Attorneys-General of Queensland 20th-century Australian politicians Australian people of Irish descent Australian Labor Party members of the Parliament of Queensland Australian King's Counsel

Premier of Queensland

The premier of Queensland is the head of government in the Australian state of Queensland.

By convention the premier is the leader of the party with a parliamentary majority in the unicameral Legislative Assembly of Queensland. The premier is ap ...

from 1915 to 1919, as leader of the state Labor Party. He resigned to enter federal politics, sitting in the House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entitles. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often c ...

for the federal Labor Party from 1919 until his premature death less than two years later.

Ryan was born in Port Fairy, Victoria

Port Fairy (historically known as Belfast) is a coastal town in south-western Victoria, Australia. It lies on the Princes Highway in the Shire of Moyne, west of Warrnambool and west of Melbourne, at the point where the Moyne River enters the S ...

, to Irish immigrant parents. He studied arts and law at the University of Melbourne

The University of Melbourne is a public research university located in Melbourne, Australia. Founded in 1853, it is Australia's second oldest university and the oldest in Victoria. Its main campus is located in Parkville, an inner suburb nor ...

, and worked for several years as a teacher at various private schools around Australia. He eventually settled in Queensland

)

, nickname = Sunshine State

, image_map = Queensland in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Queensland in Australia

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, established_ ...

and entered the legal profession, working as a barrister in Brisbane

Brisbane ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the states and territories of Australia, Australian state of Queensland, and the list of cities in Australia by population, third-most populous city in Australia and Oceania, with a populati ...

. Ryan was elected to the Queensland Legislative Assembly

The Legislative Assembly of Queensland is the sole chamber of the unicameral Parliament of Queensland established under the Constitution of Queensland. Elections are held every four years and are done by full preferential voting. The Assembly ...

in 1909, and became leader of the Labor Party in 1912. He led the party to victory at the 1915 state election, the first time it had secured majority government

A majority government is a government by one or more governing parties that hold an absolute majority of seats in a legislature. This is as opposed to a minority government, where the largest party in a legislature only has a plurality of seats. ...

in Queensland.

As premier, Ryan led a reforming government that implemented many of the planks in the Labor platform, including the expansion of workers' rights

Labor rights or workers' rights are both legal rights and human rights relating to labor relations between workers and employers. These rights are codified in national and international labor and employment law. In general, these rights influen ...

, the implementation of price controls

Price controls are restrictions set in place and enforced by governments, on the prices that can be charged for goods and services in a market. The intent behind implementing such controls can stem from the desire to maintain affordability of good ...

, and the establishment of new state-owned enterprises. After the Labor Party split of 1916, Queensland had the only remaining Labor government in Australia, giving Ryan a national profile. His government was re-elected at the 1918 state election but, in the following year, Ryan resigned to enter federal politics, winning the Division of West Sydney

The Division of West Sydney was an Australian electoral division in the state of New South Wales. It was located in the inner western suburbs of Sydney, and at various times included the suburbs of Pyrmont, Darling Harbour, Surry Hills, ...

in New South Wales at the 1919 federal election. He was widely seen as the heir apparent to the Labor Party's federal leader, Frank Tudor

Francis Gwynne Tudor (29 January 1866 – 10 January 1922) was an Australian politician who served as the leader of the Australian Labor Party from 1916 until his death. He had previously been a government minister under Andrew Fisher and Billy ...

, who was in poor health. Ryan's sudden death from pneumonia, at the age of 45, was seen as a major blow for the labour movement.

Early life

Thomas Joseph Ryan was born atPort Fairy, Victoria

Port Fairy (historically known as Belfast) is a coastal town in south-western Victoria, Australia. It lies on the Princes Highway in the Shire of Moyne, west of Warrnambool and west of Melbourne, at the point where the Moyne River enters the S ...

, Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a Sovereign state, sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous List of islands of Australia, sma ...

, the fifth of six children of Timothy Joseph Ryan, an illiterate Irish labourer who had migrated to Victoria in 1860 and become a small farmer, and his Irish wife Jane, née Cullen (died 1883). Thomas's father shared his keen interest in politics with his family, but was himself never politically active.

Ryan was educated at South Melbourne College

South Melbourne College was a co-education boarding school in South Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. The school was founded by Thomas Palmer in 1883.

John Bernard O'Hara became a partner in 1889 and became sole proprietor in 1893-4. In his ha ...

, Xavier College

Xavier College is a Roman Catholic, day and boarding school predominantly for boys, founded in 1872 by the Society of Jesus, with its main campus located in Kew, an eastern suburb of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. Classes started in 1878.

...

, Kew, and the University of Melbourne

The University of Melbourne is a public research university located in Melbourne, Australia. Founded in 1853, it is Australia's second oldest university and the oldest in Victoria. Its main campus is located in Parkville, an inner suburb nor ...

, where he graduated B.A.

Bachelor of arts (BA or AB; from the Latin ', ', or ') is a bachelor's degree awarded for an undergraduate program in the arts, or, in some cases, other disciplines. A Bachelor of Arts degree course is generally completed in three or four yea ...

and LL.B.

Bachelor of Laws ( la, Legum Baccalaureus; LL.B.) is an undergraduate law degree in the United Kingdom and most common law jurisdictions. Bachelor of Laws is also the name of the law degree awarded by universities in the People's Republic of Chi ...

He was appointed an assistant classics master at the University High School, Melbourne

, motto_translation = With Zeal and Loyalty

, established =

, type = Government-funded co-educational secondary day school

, principal = Ciar Foster

, location = 77 St ...

, and subsequently held teaching positions at the Launceston Church Grammar School

(Unless the Lord is with us, our labour is in vain)

, established =

, type = Independent, co-educational, day & boarding

, denomination = Anglican

, slogan = Nurture, Challenge, I ...

, at the Maryborough Grammar School, and the Rockhampton Grammar School

, motto_translation=Grow in character and scholarship

, established = 1881

, type = Independent, day & boarding

, gender = Co-educational

, head = Dr Phillip Moulds

, city = Rockhampton

, state = Queensland

, c ...

, where he became second master. He resigned that position on being admitted to the Queensland bar in December 1901. He practised as a solicitor

A solicitor is a legal practitioner who traditionally deals with most of the legal matters in some jurisdictions. A person must have legally-defined qualifications, which vary from one jurisdiction to another, to be described as a solicitor and ...

at Rockhampton, and subsequently as a barrister

A barrister is a type of lawyer in common law jurisdictions. Barristers mostly specialise in courtroom advocacy and litigation. Their tasks include taking cases in superior courts and tribunals, drafting legal pleadings, researching law and ...

at Brisbane

Brisbane ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the states and territories of Australia, Australian state of Queensland, and the list of cities in Australia by population, third-most populous city in Australia and Oceania, with a populati ...

. While at Rockhampton in 1900, he joined the Australian Natives' Association

The Australian Natives' Association (ANA) was a mutual society founded in Melbourne, Australia in April 1871. It was founded by and for the benefit of native-born white Australians and membership was restricted exclusively to that group.

The A ...

and became its local president.

Queensland politician

At the 1903 federal election, Ryan stood unsuccessfully as an

At the 1903 federal election, Ryan stood unsuccessfully as an Independent

Independent or Independents may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Artist groups

* Independents (artist group), a group of modernist painters based in the New Hope, Pennsylvania, area of the United States during the early 1930s

* Independ ...

Protectionist

Protectionism, sometimes referred to as trade protectionism, is the economic policy of restricting imports from other countries through methods such as tariffs on imported goods, import quotas, and a variety of other government regulations. ...

candidate in the seat of Capricornia. He joined the Labor Party in 1904, and was the party's candidate in state seat of Rockhampton North at the 1907 state election, but was again unsuccessful. At the state election in October 1909, he was elected to the Legislative Assembly of Queensland

The Legislative Assembly of Queensland is the sole chamber of the unicameral Parliament of Queensland established under the Constitution of Queensland. Elections are held every four years and are done by full preferential voting. The Assembl ...

as Labor member for Barcoo. He retained the seat for 10 years and, after the 1912 election, he was chosen as leader of the Labor Party, following the resignation of David Bowman.

After the party's success in the 1915 election, the Ryan government became the first majority Labor government in Queensland. Some of the eight members of his Cabinet had connections with the early ALP of the 1880s and the Shearers' Strike. His government provided the example which would see Labor in power in Queensland almost continuously until 1957.

Major reform of labour laws and agricultural policy was part of the Ryan legacy. His government came to power with a large majority, with Ryan as premier, chief secretary, and attorney-general

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general or attorney-general (sometimes abbreviated AG or Atty.-Gen) is the main legal advisor to the government. The plural is attorneys general.

In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have exec ...

. An era of progressive industrial legislation and the expansion of state enterprise began. Among the measures passed were the Industrial Arbitration Act, Labour Exchanges Act, Workers' Compensation Act, Inspection of Machinery and Scaffolding Act, and Factories and Shops Amendment Act.

However, where the Ryan government particularly broke fresh ground was the entry of the state into trading activities. Pastoral stations were purchased and run as going concerns, and many retail butchers' shops were opened in Brisbane and other parts of Queensland, which sold meat cheaper than elsewhere and proved to be very popular. Railway refreshment rooms were taken over, state hotels were built or purchased, a producing agency was established, coal mines were acquired, iron and steel works were opened, and a state insurance department was established. In addition, sugarcane

Sugarcane or sugar cane is a species of (often hybrid) tall, Perennial plant, perennial grass (in the genus ''Saccharum'', tribe Andropogoneae) that is used for sugar Sugar industry, production. The plants are 2–6 m (6–20 ft) tall with ...

price boards were set up, providing fair returns for growers and fair wages for sugar workers. Women were given the right to stand for parliament, industrial reforms were carried out which gave workers a "new deal".

Ryan showed good generalship at the 1918 election and, despite a split in the Labor Party over conscription for overseas service, Ryan's government was returned with a large majority. The defection of Prime Minister Billy Hughes

William Morris Hughes (25 September 1862 – 28 October 1952) was an Australian politician who served as the seventh prime minister of Australia, in office from 1915 to 1923. He is best known for leading the country during World War I, but ...

and a significant number of other Labor politicians to the non-Labor side, including New South Wales Premier

The premier of New South Wales is the head of government in the state of New South Wales, Australia. The Government of New South Wales follows the Westminster Parliamentary System, with a Parliament of New South Wales acting as the legislature. ...

William Holman

William Arthur Holman (4 August 1871 – 5 June 1934) was an Australian politician who served as Premier of New South Wales from 1913 to 1920. He came to office as the leader of the Australian Labor Party (New South Wales Branch), Labor Party, ...

, left Ryan as the head of the only Labor government at any level in Australia. As such, he was instrumental in leading the fight against conscription

Conscription (also called the draft in the United States) is the state-mandated enlistment of people in a national service, mainly a military service. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it continues in some countries to the present day un ...

in the plebiscites launched by Hughes in 1916 and 1917.

Friction between Hughes and Ryan almost led to violence in November 1917, when the Australian federal government conducted a raid on the Government Printing Office

In November 1917 during World War I, the Australian Government conducted a raid on the Queensland Government Printing Office in Brisbane. The aim of the raid was to confiscate any copies of the Hansard, the official parliamentary transcript, whi ...

in Brisbane

Brisbane ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the states and territories of Australia, Australian state of Queensland, and the list of cities in Australia by population, third-most populous city in Australia and Oceania, with a populati ...

, to confiscate copies of Hansard

''Hansard'' is the traditional name of the transcripts of parliamentary debates in Britain and many Commonwealth countries. It is named after Thomas Curson Hansard (1776–1833), a London printer and publisher, who was the first official print ...

that covered debates in the Queensland Parliament

The Parliament of Queensland is the legislature of Queensland, Australia. As provided under the Constitution of Queensland, the Parliament consists of the Monarch of Australia and the Legislative Assembly. It has been the only unicameral s ...

during which anti-conscription sentiments had been aired. On 29 November 1917, Billy Hughes travelled to Warwick

Warwick ( ) is a market town, civil parish and the county town of Warwickshire in the Warwick District in England, adjacent to the River Avon. It is south of Coventry, and south-east of Birmingham. It is adjoined with Leamington Spa and Whi ...

, southern Queensland

)

, nickname = Sunshine State

, image_map = Queensland in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Queensland in Australia

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, established_ ...

, to campaign in support of the 1917 Australian conscription referendum

The 1917 Australian plebiscite was held on 20 December 1917. It contained one question.

* ''Are you in favour of the proposal of the Commonwealth Government for reinforcing the Australian Imperial Force oversea?''

Background

The 1917 plebisci ...

. An egg was thrown at Hughes, resulting in his decision to form the Australian Federal Police

The Australian Federal Police (AFP) is the national and principal federal law enforcement agency of the Australian Government with the unique role of investigating crime and protecting the national security of the Commonwealth of Australia. Th ...

.

The State Library of Queensland

The State Library of Queensland is the main reference and research library provided to the people of the State of Queensland, Australia, by the state government. Its legislative basis is provided by the Queensland Libraries Act 1988. It contai ...

holds several collections providing insight into the complexity and divisiveness of the conscription debate at the time, but the Stable Collection 1917-1991 containing a surviving copy of Hansard No. 37 is considered a treasure among them.

Federal politician

Ryan was asked by a resolution of a special federal Labor conference to enter federal politics, the only occasion that such a motion has been passed. He was campaign director for the Labor Party during the 1919 Federal election, and was elected to theHouse of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entitles. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often c ...

in the Federal Parliament as the member for West Sydney. In 1920, he was appointed King's Counsel

In the United Kingdom and in some Commonwealth countries, a King's Counsel ( post-nominal initials KC) during the reign of a king, or Queen's Counsel (post-nominal initials QC) during the reign of a queen, is a lawyer (usually a barrister or ...

. He had been widely touted as a likely Labor leader before his premature death.Featured Chambers Issue 32— Hearsay – The Journal of the Bar Association of Queensland Although a big man physically, Ryan was not strong in health. Weakened by influenza while he was in England at the time of the

1918 flu pandemic

The 1918–1920 influenza pandemic, commonly known by the misnomer Spanish flu or as the Great Influenza epidemic, was an exceptionally deadly global influenza pandemic caused by the H1N1 influenza A virus. The earliest documented case was ...

, he suffered repeatedly thereafter from bronchial and nasal infections. Furthermore, he seldom took a holiday and was tired from overwork. In July 1921, he set out to campaign for the Labor candidate William Dunstan in the by-election

A by-election, also known as a special election in the United States and the Philippines, a bye-election in Ireland, a bypoll in India, or a Zimni election (Urdu: ضمنی انتخاب, supplementary election) in Pakistan, is an election used to f ...

for the federal seat of Maranoa. He was sick at the start and his condition worsened during the long trip. On 1 August 1921, he died in Glenco Hospital, Barcaldine, Queensland

Barcaldine () is a rural town and suburbs and localities (Australia), locality in the Barcaldine Region in Queensland, Australia. This is the administrative centre of the Barcaldine Region. Barcaldine played a major role in the Australian labou ...

, of pneumonia. His body was taken by train to Brisbane, past crowds gathered at each station. Archbishops Duhig and Mannix

''Mannix'' is an American detective television series that ran from 1967 to 1975 on CBS. It was created by Richard Levinson and William Link, and developed by executive producer Bruce Geller. The title character, Joe Mannix, is a private inves ...

presided over his funeral in St Stephen's Cathedral and his burial in Toowong Cemetery

Toowong Cemetery is a heritage-listed cemetery on the corner of Frederick Street and Mt Coot-tha Road, Toowong, City of Brisbane, Queensland, Australia. It was established in 1866 and formally opened in 1875. It is Queensland's largest cemet ...

.

Personal life

Ryan married Lily Virginia Cook in 1910. She survived him with a son and a daughter and, in 1944, was appointed the Queensland government representative inMelbourne

Melbourne ( ; Boonwurrung/Woiwurrung: ''Narrm'' or ''Naarm'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Victoria, and the second-most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Its name generally refers to a met ...

.

Legacy

Bank of England

The Bank of England is the central bank of the United Kingdom and the model on which most modern central banks have been based. Established in 1694 to act as the English Government's banker, and still one of the bankers for the Government of ...

to militant unionists. He could hit hard with sarcasm when challenged by foes such as Hughes, yet he remained friendly with numerous fellow parliamentarians, including some of his firmest conservative opponents. The Queensland parliamentary officer and historian, Charles Bernays, regarded Ryan as the greatest parliamentary leader he had observed: "an earnest exponent of the faith that was in him, and a generous big-hearted fighter". Many other historians believe that Ryan, a much bolder figure than federal Labor leader Frank Tudor

Francis Gwynne Tudor (29 January 1866 – 10 January 1922) was an Australian politician who served as the leader of the Australian Labor Party from 1916 until his death. He had previously been a government minister under Andrew Fisher and Billy ...

, would have been Australia's fourth ALP Prime Minister, had he lived just a few years more.Johnston, W. Ross; D. J. Murphy. "Ryan, Thomas Joseph (1876 - 1921)" A memorial fund collected money to erect a ten-foot (3 m) bronze statue which stands in Queen's Park, Brisbane, near the Old Executive Building. The wording on the metal plaque on the pedestal of the statue describes him as: "Scholar - Jurist - Statesman".

The Federal electoral division of Ryan is named after him, and a Ryan medal was struck for candidates obtaining the highest pass in the annual state scholarship examination.

See also

*Ryan Ministry

The Ryan Ministry was the 27th ministry of the Government of Queensland and was led by Premier T. J. Ryan of the Labor Party. It was the first majority Labor government in Queensland's history. It succeeded the Denham Ministry on 1 June 1915, ...

* TJ Ryan Foundation

References

Bibliography

*''Queensland Political Portraits 1859-1952'', University of Queensland Press, 1978 * *External links

Funeral Hearse of T. J. Ryan at Toowong Cemetery, ca. 1921

—

State Library of Queensland

The State Library of Queensland is the main reference and research library provided to the people of the State of Queensland, Australia, by the state government. Its legislative basis is provided by the Queensland Libraries Act 1988. It contai ...

Stable collection 1917 – 1991: treasure collection of the John Oxley Library

- John Oxley Library blog, State Library of Queensland. {{DEFAULTSORT:Ryan, Thomas Joseph 1876 births 1921 deaths Premiers of Queensland Australian Labor Party members of the Parliament of Australia Members of the Australian House of Representatives Members of the Australian House of Representatives for West Sydney People from Port Fairy Burials at Toowong Cemetery People educated at Xavier College Melbourne Law School alumni Leaders of the Opposition in Queensland Attorneys-General of Queensland 20th-century Australian politicians Australian people of Irish descent Australian Labor Party members of the Parliament of Queensland Australian King's Counsel