T.M. Healy on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Timothy Michael Healy, KC (17 May 1855 – 26 March 1931) was an Irish

He was born in

He was born in

Initially a passionate supporter of Parnell, he became disenchanted with his leader after Healy opposed Parnell's nomination of Captain William O’Shea to stand for a by-election in Galway city. At the time O’Shea was separated from his wife,

Initially a passionate supporter of Parnell, he became disenchanted with his leader after Healy opposed Parnell's nomination of Captain William O’Shea to stand for a by-election in Galway city. At the time O’Shea was separated from his wife,

''His quaint-perched aerie on the crags of Time''

''Where the rude din of this century''

''Can trouble him no more.''

Following Parnell's death in 1891, the IPP's anti-Parnellite majority group broke away forming the Irish National Federation (INF) under

Following Parnell's death in 1891, the IPP's anti-Parnellite majority group broke away forming the Irish National Federation (INF) under

However, at least after 1903, Healy was joined in his estrangement from the party leadership by

However, at least after 1903, Healy was joined in his estrangement from the party leadership by

He returned to considerable prominence in 1922 when, on the urging of the soon-to-be

He returned to considerable prominence in 1922 when, on the urging of the soon-to-be  Initially, the

Initially, the

''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (2004)

* Cadogan, Tim & Falvey, Jeremiah: ''A Biographical Dictionary of Cork'' (2006) * Jackson, Alwin: ''Home Rule 1800–2000'' pp. 100–103 (2003) * * Maume, Patrick: ''The long Gestation, Irish Nationalist life 1881–1918'' (1999)

excerpt

* David Foxton, Revolutionary Lawyers, Sinn Féin and Crown Courts, (4 Courts Press, 2008), () * Sir Dunbar Plunket Barton, P.C., ''Timothy Healy: Memories and Anecdotes''. (Dublin: Talbot Press Limited, and London: Faber & Faber, Limited, 1933).

* ttp://www.oireachtas.ie/viewdoc.asp?fn=/documents/addresses/3Oct1923.htm Governor-General Tim Healy's second Speech to the Dáil (3 October 1923)

Letters and Leaders of my Day by T. M. Healy, KC

*

Parliamentary Archives, Papers of Timothy Michael Healy, KC

{{DEFAULTSORT:Healy, Tim 1855 births 1931 deaths 19th-century Irish people All-for-Ireland League MPs Anti-Parnellite MPs Burials at Glasnevin Cemetery Governors-General of the Irish Free State Healyite Nationalist MPs Independent Nationalist MPs Irish barristers Irish journalists Irish non-fiction writers Irish male non-fiction writers Irish Parliamentary Party MPs Irish Queen's Counsel Irish land reform activists Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for County Wexford constituencies (1801–1922) Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for County Cork constituencies (1801–1922) Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for County Londonderry constituencies (1801–1922) Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for County Longford constituencies (1801–1922) Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for County Louth constituencies (1801–1922) Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for County Monaghan constituencies (1801–1922) People from Bantry Politicians from County Cork UK MPs 1892–1895 UK MPs 1895–1900 UK MPs 1900–1906 UK MPs 1906–1910 UK MPs 1910 UK MPs 1910–1918

nationalist

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: The ...

politician, journalist, author, barrister

A barrister is a type of lawyer in common law jurisdictions. Barristers mostly specialise in courtroom advocacy and litigation. Their tasks include taking cases in superior courts and tribunals, drafting legal pleadings, researching law and ...

and a controversial Irish Member of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members of ...

(MP) in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland was a sovereign state in the British Isles that existed between 1801 and 1922, when it included all of Ireland. It was established by the Acts of Union 1800, which merged the Kingdom of Great B ...

. His political career began in the 1880s under Charles Stewart Parnell

Charles Stewart Parnell (27 June 1846 – 6 October 1891) was an Irish nationalist politician who served as a Member of Parliament (MP) from 1875 to 1891, also acting as Leader of the Home Rule League from 1880 to 1882 and then Leader of the ...

's leadership of the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP) and continued into the 1920s, when he was the first governor-general of the Irish Free State

The Governor-General of the Irish Free State ( ga, Seanascal Shaorstát Éireann) was the official representative of the sovereign of the Irish Free State from 1922 to 1936. By convention, the office was largely ceremonial. Nonetheless, it wa ...

.

Family background

He was born in

He was born in Bantry

Bantry () is a town in the civil parish of Kilmocomoge in the barony of Bantry on the southwest coast of County Cork, Ireland. It lies in West Cork at the head of Bantry Bay, a deep-water gulf extending for to the west. The Beara Peninsula is ...

, County Cork

County Cork ( ga, Contae Chorcaí) is the largest and the southernmost county of Ireland, named after the city of Cork, the state's second-largest city. It is in the province of Munster and the Southern Region. Its largest market towns are ...

, the second son of Maurice Healy, clerk of the Bantry Poor Law Union, and Eliza (née Sullivan) Healy. His elder brother, Thomas Healy (1854–1924), was a solicitor

A solicitor is a legal practitioner who traditionally deals with most of the legal matters in some jurisdictions. A person must have legally-defined qualifications, which vary from one jurisdiction to another, to be described as a solicitor and ...

and Member of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members of ...

(MP) for North Wexford and his younger brother, Maurice Healy

Maurice Healy (3 January 1859 – 9 November 1923) was an Irish nationalist politician, lawyer and Member of Parliament (MP). As a member of the Irish Parliamentary Party, he was returned to in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom of Gre ...

(1859–1923), with whom he held a lifelong close relationship, was a solicitor and MP for Cork City.

His father was descended from a family line which in holding to their Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

faith, lost their lands, which he compensated by being a scholarly gentleman. His father was transferred in 1862 to a similar position in Lismore, County Waterford

Lismore () is a historic town in County Waterford, in the province of Munster, Ireland. Originally associated with Saint Mochuda of Lismore, who founded Lismore Abbey in the 7th century, the town developed around the medieval Lismore Castle. As ...

, holding the post until his death in 1906.

Timothy Michael Healy was educated at the Christian Brothers school in Fermoy, and was otherwise largely self-educated, in 1869 at the age of fourteen going to live with his uncle, Timothy Daniel Sullivan MP, in Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of th ...

.

Early life

He then moved to England finding employment in 1871 with theNorth Eastern Railway Company

The North Eastern Railway (NER) was an English railway company. It was incorporated in 1854 by the combination of several existing railway companies. Later, it was amalgamated with other railways to form the London and North Eastern Railway at ...

in Newcastle-upon-Tyne

Newcastle upon Tyne ( RP: , ), or simply Newcastle, is a city and metropolitan borough in Tyne and Wear, England. The city is located on the River Tyne's northern bank and forms the largest part of the Tyneside built-up area. Newcastle is als ...

. There he became deeply involved in the Irish Home Rule

The Irish Home Rule movement was a movement that campaigned for Devolution, self-government (or "home rule") for Ireland within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was the dominant political movement of Irish nationalism from 1 ...

politics of the local Irish community. After leaving for London in 1878 Healy worked as a confidential clerk in a factory owned by his relative, then worked as a parliamentary correspondent for ''The Nation

''The Nation'' is an American liberal biweekly magazine that covers political and cultural news, opinion, and analysis. It was founded on July 6, 1865, as a successor to William Lloyd Garrison's '' The Liberator'', an abolitionist newspaper tha ...

'' newspaper owned by his uncle, writing numerous articles in support of Parnell, the newly emergent and more militant home rule leader, and his policy of parliamentary ''obstructionism

Obstructionism is the practice of deliberately delaying or preventing a process or change, especially in politics.

As workplace aggression

An obstructionist causes problems. Neuman and Baron (1998) identify obstructionism as one of the three dim ...

''.

Parnell admired Healy's intelligence and energy after Healy had established himself as part of Parnell's broader political circle. He became Parnell's secretary but was denied contact to Parnell's small inner circle of political colleagues.

Parnell, however, brought Healy into the Irish Party (IPP) and supported him as a nationalist candidate when elected MP for Wexford Borough in 1880–83 against the aspiring John Redmond

John Edward Redmond (1 September 1856 – 6 March 1918) was an Irish nationalism, Irish nationalist politician, barrister, and Member of Parliament (United Kingdom), MP in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom. He was best known as lead ...

whose father, William Archer Redmond, was its recently deceased MP. Healy was returned unopposed to parliament, aided by the fact that Redmond stood aside and that he had survived an agrarian court case which alleging intimidation.

Political career

In parliament, Healy did not physically cut an imposing figure but impressed by the application of sheer intelligence, diligence and volatile use of speech when he achieved the ''Healy Clause'' in theLand Law (Ireland) Act 1881

The Land Law (Ireland) Act 1881 (44 & 45 Vict. c. 49) was the second Irish land act passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom in 1881.

Background

The Liberal government of William Ewart Gladstone had previously passed the Landlord and Ten ...

which provided that no further rent should in future be charged on tenant's improvements. By the mid-1880s Healy had already acquired a reputation for a scurrilousness of tone. He married his cousin Eliza Sullivan in 1882, they had three daughters and three sons and he enjoyed a happy and intense family life, closely interlinked both by friendship and intermarriage with the Sullivans of west Cork.

Through his reputation as a friend of the farmers, after having been imprisoned for four months following an agrarian case, and backed by Parnell, he was elected in a Monaghan

Monaghan ( ; ) is the county town of County Monaghan, Republic of Ireland, Ireland. It also provides the name of its Civil parishes in Ireland, civil parish and Monaghan (barony), barony.

The population of the town as of the 2016 census was 7 ...

by-election in June 1883–5, deemed to be the climax in the Healy-Parnell relationship. In 1884 he was called to the Irish bar as a barrister (in 1889 to the inner bar as K.C., in London in 1910). His reputation allowed him to build an extensive legal practice, particularly in land cases. Parnell chose him unwisely for South Londonderry in 1885, which Ulster

Ulster (; ga, Ulaidh or ''Cúige Uladh'' ; sco, label= Ulster Scots, Ulstèr or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional Irish provinces. It is made up of nine counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United King ...

seat he only held for a year. He was then elected in 1886–92 for North Longford

North Longford was a UK parliamentary constituency in Ireland. It returned one Member of Parliament (MP) to the British House of Commons 1885–1918.

Prior to the 1885 United Kingdom general election and after the dissolution of Parliament in 19 ...

.

Prompted by the depression in the prices of dairy products and cattle in the mid-1880 as well as bad weather for a number of years, many tenant farmers unable to pay their rents were left under the threat of eviction. Healy devised a strategy to secure a reduction in rent from the landlords which became known as the Plan of Campaign, organised in 1886 amongst others by Timothy Harrington

Timothy Charles Harrington (1851 – 12 March 1910), born in Castletownbere, Castletownbere, County Cork, was an Ireland, Irish journalist, barrister, Irish nationalism, nationalist politician and Member of Parliament (United Kingdom), Member o ...

.

In his novel '' The Man Who Was Thursday'' G.K. Chesterton

Gilbert Keith Chesterton (29 May 1874 – 14 June 1936) was an English writer, philosopher, Christian apologist, and literary and art critic. He has been referred to as the "prince of paradox". Of his writing style, ''Time'' observed: "Wh ...

describes one of his characters as a "... little man, with a black beard and glasses – a man somewhat of the type of Mr Tim Healy ...".

Invective rift

Initially a passionate supporter of Parnell, he became disenchanted with his leader after Healy opposed Parnell's nomination of Captain William O’Shea to stand for a by-election in Galway city. At the time O’Shea was separated from his wife,

Initially a passionate supporter of Parnell, he became disenchanted with his leader after Healy opposed Parnell's nomination of Captain William O’Shea to stand for a by-election in Galway city. At the time O’Shea was separated from his wife, Katharine O'Shea

Katharine Parnell (née Wood; 30 January 1846 – 5 February 1921), known before her second marriage as Katharine O'Shea, and usually called Katie O'Shea by friends and Kitty O'Shea by enemies, was an English woman of aristocratic background ...

, with whom Parnell was secretly living. Healy objected to this, as the party had not been consulted and he believed Parnell was putting his personal relationship before the national interest. When Parnell travelled to Galway to support O’Shea, Healy was forced to back down.

In 1890 in a sensational divorce case O'Shea sued his wife for divorce, citing Parnell as co-respondent. Healy and most of Parnell's associates rejected Parnell's continuing leadership of the party, believing it was recklessly endangering the party's alliance with Gladstonian

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British statesman and Liberal politician. In a career lasting over 60 years, he served for 12 years as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, spread over four non-conse ...

Liberalism

Liberalism is a political and moral philosophy based on the rights of the individual, liberty, consent of the governed, political equality and equality before the law."political rationalism, hostility to autocracy, cultural distaste for c ...

. Healy became Parnell's most outspoken critic. When Parnell asked his colleagues at one party meeting "Who is the master of the party?", Healy famously retorted with another question "Aye, but who is the mistress of the party?" – a comment that almost led to the men coming to blows. His savage onslaught in public reflected his conservative Catholic origin. A substantial minority of the Irish people never forgave him for his role during the divorce crisis, permanently damaging his own standing in public life. The rift prompted nine-year-old Dublin schoolboy James Joyce

James Augustine Aloysius Joyce (2 February 1882 – 13 January 1941) was an Irish novelist, poet, and literary critic. He contributed to the modernist avant-garde movement and is regarded as one of the most influential and important writers of ...

to write a poem called ''Et Tu, Healy?'', which Joyce's father had printed and circulated. Only three lines remain:

Estrangement

Following Parnell's death in 1891, the IPP's anti-Parnellite majority group broke away forming the Irish National Federation (INF) under

Following Parnell's death in 1891, the IPP's anti-Parnellite majority group broke away forming the Irish National Federation (INF) under John Dillon

John Dillon (4 September 1851 – 4 August 1927) was an Irish politician from Dublin, who served as a Member of Parliament (MP) for over 35 years and was the last leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party. By political disposition Dillon was an a ...

. Healy was at first its most outspoken member, when in 1892 he captured North Louth for the anti-Parnellites, who in all won seventy-one seats. But finding it impossible to work with or under any post-Parnell leadership, especially Dillon's, he was expelled in 1895 from the INF executive committee, having previously been expelled from the Irish party's minor nine-member pro-Parnellite Irish National League

The Irish National League (INL) was a nationalist political party in Ireland. It was founded on 17 October 1882 by Charles Stewart Parnell as the successor to the Irish National Land League after this was suppressed. Whereas the Land League h ...

(INL) under John Redmond

John Edward Redmond (1 September 1856 – 6 March 1918) was an Irish nationalism, Irish nationalist politician, barrister, and Member of Parliament (United Kingdom), MP in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom. He was best known as lead ...

.

In the following decades, largely due to his expanding legal practice, he became a part-time politician and estranged from the national movement, setting up his own personal 'Healyite' organisation, called the "People's Rights Association", based on his position as MP for North Louth (the seat he held until the December 1910 election when defeated by Richard Hazleton). He waged war during the 1890s with Dillon and his National Federation (INF) and then intrigued with Redmond's smaller Parnellite group to play a substantial role behind the scenes in helping the rival party factions to reunite under Redmond in 1900.

Healy was extremely embittered by the fact that both his brothers and his followers were purged from the IPP list in the 1900 general election, and that his support for Redmond in the re-united party went unrewarded; on the contrary, Redmond soon found it wiser to conciliate Dillon. But two years later Healy was again expelled. He remained "the enemy within", recruiting malcontent MPs to harass the party and survived politically by dint of his assiduous constituency work, as well as through the influence of his clerical ally Dr. Michael Cardinal Logue, Primate of All Ireland

The Primacy of Ireland was historically disputed between the Archbishop of Armagh and the Archbishop of Dublin until finally settled by Pope Innocent VI. ''Primate'' is a title of honour denoting ceremonial precedence in the Church, and in t ...

and Archbishop of Armagh

In Christian denominations, an archbishop is a bishop of higher rank or office. In most cases, such as the Catholic Church, there are many archbishops who either have jurisdiction over an ecclesiastical province in addition to their own archdio ...

. Healy remained rooted in the extended 'Bantry Gang', a highly influential political and commercial nexus based originally in West Cork

West Cork ( ga, Iarthar Chorcaí) is a tourist region and municipal district in County Cork, Ireland. As a municipal district, West Cork falls within the administrative area of Cork County Council, and includes the towns of Bantry, Castletownbe ...

, which included his key patron, the Catholic business magnate and owner of the ''Irish Independent

The ''Irish Independent'' is an Irish daily newspaper and online publication which is owned by Independent News & Media (INM), a subsidiary of Mediahuis.

The newspaper version often includes glossy magazines.

Traditionally a broadsheet new ...

'', William Martin Murphy

William Martin Murphy (6 January 1845 – 26 June 1919) was an Irish businessman, newspaper publisher and politician. A member of parliament (MP) representing Dublin from 1885 to 1892, he was dubbed "William ''Murder'' Murphy" among the Irish ...

, who provided a platform for Healy and other critics of the IPP.

Coalition of a kind

However, at least after 1903, Healy was joined in his estrangement from the party leadership by

However, at least after 1903, Healy was joined in his estrangement from the party leadership by William O'Brien

William O'Brien (2 October 1852 – 25 February 1928) was an Irish nationalist, journalist, agrarian agitator, social revolutionary, politician, party leader, newspaper publisher, author and Member of Parliament (MP) in the House of Commons of ...

. O’Brien had been for years one of Healy's strongest critics, but now he too felt annoyed both by his own alienation from the party and by Redmond's subservience to Dillon. Involved with the Irish Reform Association

The Irish Reform Association (1904–1905) was an attempt to introduce limited devolved self-government to Ireland by a group of reform oriented Irish unionist land owners who proposed to initially adopt something less than full Home Rule. It ...

1904–5, they entered a loose coalition, which lasted throughout the life of the IPP. They were in agreement that agrarian radicalism brought little return, and with Healy practically becoming a Parnellite, they preferred to pursue a policy of conciliation with the Protestant class in order to further the acceptance of Home Rule. Redmond was sympathetic to this policy but was inhibited by Dillon. Redmond, in an act of ''rapprochement'', briefly re-united them with the party in 1908. Fiercely independent, both split off again in 1909, responding to real changes in the social basis of Irish politics. In 1908 Healy acted as counsel for Sir Arthur Vicars, former Ulster King of Arms, in connection with the 1908 investigation of the previous year's theft of the Irish Crown Jewels

The Jewels Belonging to the Most Illustrious Order of Saint Patrick, commonly called the Irish Crown Jewels or State Jewels of Ireland, were the heavily jewelled star and badge regalia created in 1831 for the Sovereign and Grand Master of the ...

.

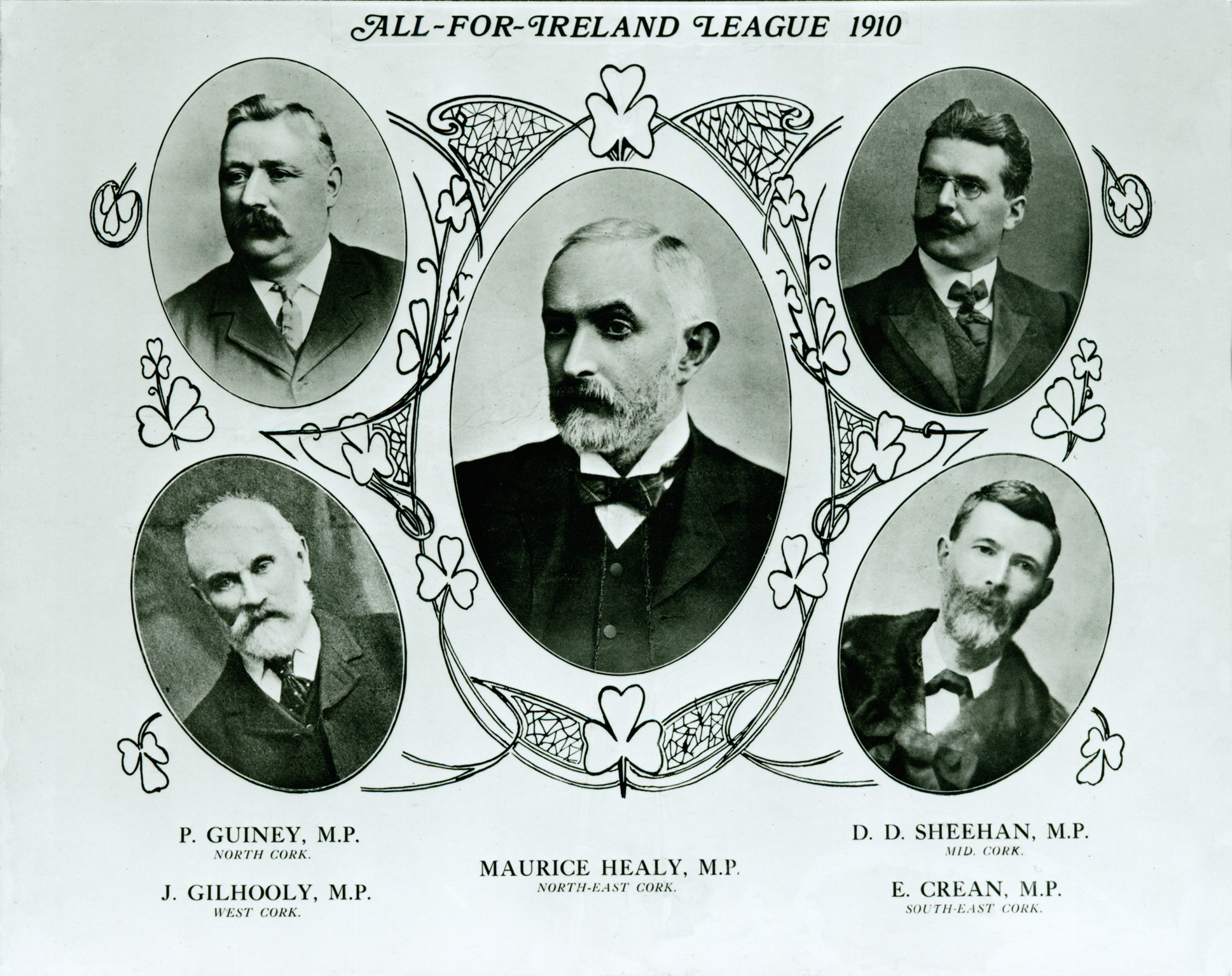

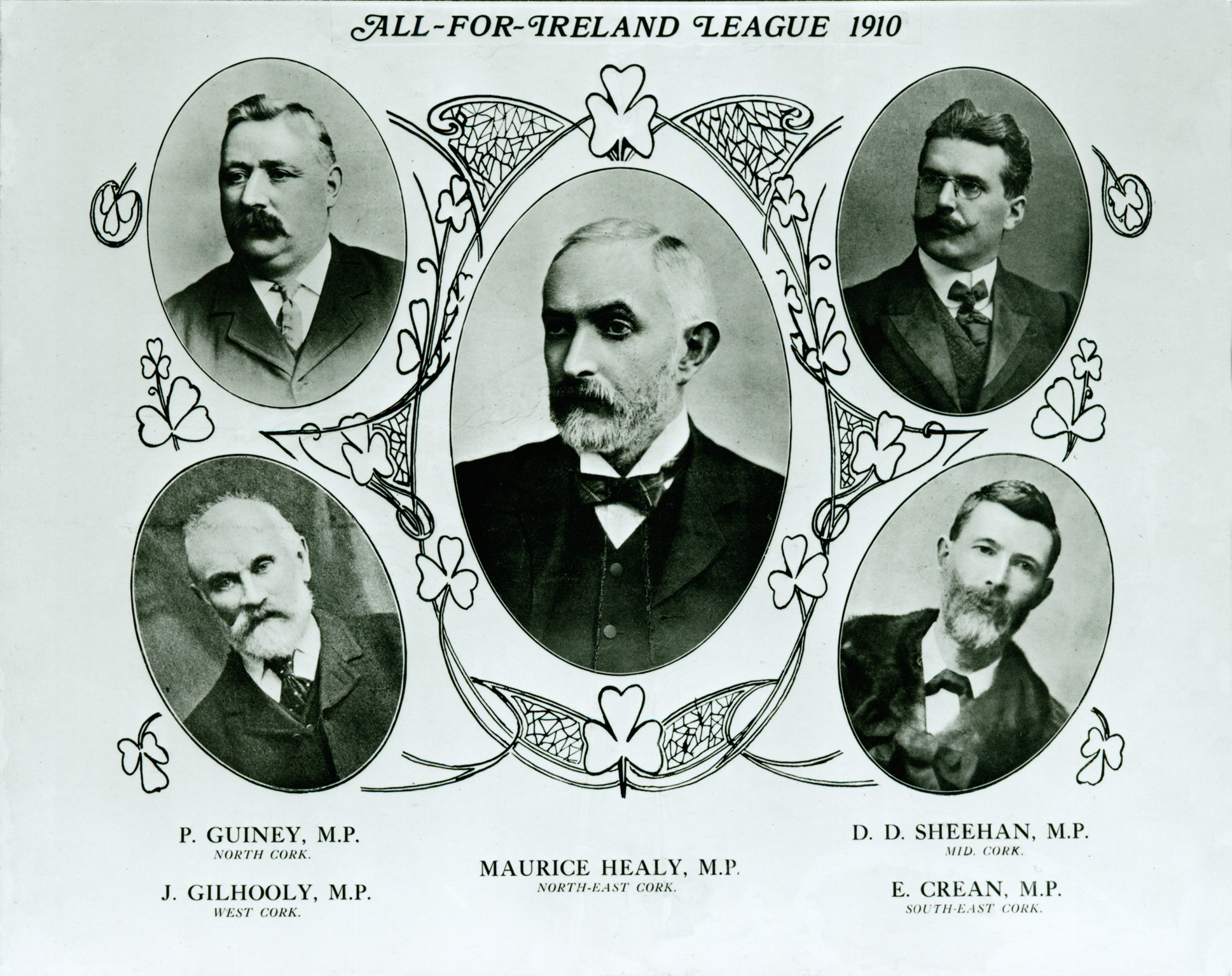

By the 1910s, it looked as though Healy was to remain a maverick on the fringes of Irish nationalism. However, he came into notoriety once more when returned in the January 1910 general election

The January 1910 United Kingdom general election was held from 15 January to 10 February 1910. The government called the election in the midst of a constitutional crisis caused by the rejection of the People's Budget by the Conservative-dominat ...

in alliance with William O'Brien's newly founded All-for-Ireland Party (AFIL), their alliance based largely on common opposition to the Irish party. He lost his seat in the following December 1910 election, but soon afterwards rejoined the O'Brienites, O’Brien providing the 1911 north-east Cork by-election vacancy created by the retirement of Moreton Frewen. Healy's reputation was not enhanced when he represented as counsel his associate William Martin Murphy, the industrialist who sparked the 1913 Dublin Lockout. Healy assiduously cultivated relationships with power brokers in Westminster such as Lord Beaverbrook

William Maxwell Aitken, 1st Baron Beaverbrook (25 May 1879 – 9 June 1964), generally known as Lord Beaverbrook, was a Canadian-British newspaper publisher and backstage politician who was an influential figure in British media and politics o ...

, and once they were introduced at Cherkley, was great friends with Janet Aitken for the remainder of his life.

Realignment

Redmond's and the IPP's powerful position of holding the balance of power atWestminster

Westminster is an area of Central London, part of the wider City of Westminster.

The area, which extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street, has many visitor attractions and historic landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, Bu ...

—and with the passing of the Third Home Rule Bill

The Government of Ireland Act 1914 (4 & 5 Geo. 5 c. 90), also known as the Home Rule Act, and before enactment as the Third Home Rule Bill, was an Act of Parliament, Act passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom intended to provide home ...

assured—left Healy and the AFIL critics in a weakened position. They condemned the bill as a 'partition deal', abstaining from its final vote in the Commons. With the outbreak of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

in August 1914, the Healy brothers supported the Allied

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

and the British war effort. Two had a son enlist in one of the Irish divisions, Timothy's eldest son, Joe, fought with distinction at Gallipoli

The Gallipoli peninsula (; tr, Gelibolu Yarımadası; grc, Χερσόνησος της Καλλίπολης, ) is located in the southern part of East Thrace, the European part of Turkey, with the Aegean Sea to the west and the Dardanelles ...

.

Having done much to damage the popular image and authority of constitutional nationalism, Healy after the Easter Rising

The Easter Rising ( ga, Éirí Amach na Cásca), also known as the Easter Rebellion, was an armed insurrection in Ireland during Easter Week in April 1916. The Rising was launched by Irish republicans against British rule in Ireland with the a ...

was convinced that the IPP and Redmond were doomed and slowly withdrew from the forefront of politics, making it clear in 1917 that he was in general sympathy with Arthur Griffith

Arthur Joseph Griffith ( ga, Art Seosamh Ó Gríobhtha; 31 March 1871 – 12 August 1922) was an Irish writer, newspaper editor and politician who founded the political party Sinn Féin. He led the Irish delegation at the negotiations that prod ...

's Sinn Féin

Sinn Féin ( , ; en, " eOurselves") is an Irish republican and democratic socialist political party active throughout both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland.

The original Sinn Féin organisation was founded in 1905 by Arthur Gri ...

movement, but not with physical force methods. In September that year he acted as counsel for the family of the dead Sinn Féin hunger striker Thomas Ashe. He was one of the few King's Counsel

In the United Kingdom and in some Commonwealth countries, a King's Counsel ( post-nominal initials KC) during the reign of a king, or Queen's Counsel (post-nominal initials QC) during the reign of a queen, is a lawyer (usually a barrister or ...

to provide legal services to members of Sinn Féin

Sinn Féin ( , ; en, " eOurselves") is an Irish republican and democratic socialist political party active throughout both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland.

The original Sinn Féin organisation was founded in 1905 by Arthur Gri ...

in various legal proceedings in both Ireland and England post the 1916 Rising. This included acting for those interned in 1916 in Frongoch internment camp

Frongoch internment camp at Frongoch in Merionethshire, Wales was a makeshift place of imprisonment during the First World War and the 1916 Easter Rising.

History

1916 the camp housed German prisoners of war in a yellow distillery and crude hu ...

in North Wales. During this time, Healy also represented Georgina Frost, in her attempts to be appointed a Petty Sessions clerk in her native County Clare. In 1920 the Bar Council of Ireland

The Bar of Ireland ( ga, Barra na hÉireann) is the professional association of barristers for Ireland, with over 2,000 members. It is based in the Law Library, with premises in Dublin and Cork. It is governed by the General Council of the Ba ...

passed an initial resolution that any barrister appearing before the Dáil Courts

The Dáil Courts (also known as Republican Courts) were the judicial branch of government of the Irish Republic, which had unilaterally declared independence in 1919. They were formally established by a decree of the First Dáil on 29 June 1920 ...

would be guilty of professional misconduct. This was challenged by Tim Healy and no final decision was made on the matter. Before the December 1918 general election, he was the first of the AFIL members to resign his seat in favour of the Sinn Féin party's candidate, and spoke in support of P. J. Little, the Sinn Féin candidate for Rathmines

Rathmines () is an affluent inner suburb on the Southside of Dublin in Ireland. It lies three kilometres south of the city centre. It begins at the southern side of the Grand Canal and stretches along the Rathmines Road as far as Rathgar to t ...

in Dublin.

Governor-General

He returned to considerable prominence in 1922 when, on the urging of the soon-to-be

He returned to considerable prominence in 1922 when, on the urging of the soon-to-be Irish Free State

The Irish Free State ( ga, Saorstát Éireann, , ; 6 December 192229 December 1937) was a state established in December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921. The treaty ended the three-year Irish War of Independence between th ...

's Provisional Government

A provisional government, also called an interim government, an emergency government, or a transitional government, is an emergency governmental authority set up to manage a political transition generally in the cases of a newly formed state or f ...

of W. T. Cosgrave, the British government

ga, Rialtas a Shoilse gd, Riaghaltas a Mhòrachd

, image = HM Government logo.svg

, image_size = 220px

, image2 = Royal Coat of Arms of the United Kingdom (HM Government).svg

, image_size2 = 180px

, caption = Royal Arms

, date_es ...

recommended to King George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until Death and state funeral of George V, his death in 1936.

Born duri ...

that Healy be appointed the first 'Governor-General of the Irish Free State

The Governor-General of the Irish Free State ( ga, Seanascal Shaorstát Éireann) was the official representative of the sovereign of the Irish Free State from 1922 to 1936. By convention, the office was largely ceremonial. Nonetheless, it wa ...

', a new office representative of the Crown

The Crown is the state in all its aspects within the jurisprudence of the Commonwealth realms and their subdivisions (such as the Crown Dependencies, overseas territories, provinces, or states). Legally ill-defined, the term has different ...

created in the 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty

The 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty ( ga , An Conradh Angla-Éireannach), commonly known in Ireland as The Treaty and officially the Articles of Agreement for a Treaty Between Great Britain and Ireland, was an agreement between the government of the ...

and introduced by a combination of the Constitution of the Irish Free State and Letters Patent from the King. The constitution was enacted in December 1922. Healy was the uncle of Kevin O'Higgins

Kevin Christopher O'Higgins ( ga, Caoimhghín Críostóir Ó hUigín; 7 June 1892 – 10 July 1927) was an Irish politician who served as Vice-President of the Executive Council and Minister for Justice from 1922 to 1927, Minister for External ...

, the Vice-President of the Executive Council and Minister for Justice A Ministry of Justice is a common type of government department that serves as a justice ministry.

Lists of current ministries of justice

Named "Ministry"

* Ministry of Justice (Abkhazia)

* Ministry of Justice (Afghanistan)

* Ministry of Just ...

in the new Free State.

Initially, the

Initially, the Government of the Irish Free State

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive, and judiciary. Government is a ...

under Cosgrave wished for Healy to reside in a new small residence, but, facing death threats from the IRA

Ira or IRA may refer to:

*Ira (name), a Hebrew, Sanskrit, Russian or Finnish language personal name

*Ira (surname), a rare Estonian and some other language family name

*Iran, UNDP code IRA

Law

*Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, US, on status of ...

, he was moved as a temporary measure into the Viceregal Lodge, the former 'out of season' residence of the Lord Lieutenant

A lord-lieutenant ( ) is the British monarch's personal representative in each lieutenancy area of the United Kingdom. Historically, each lieutenant was responsible for organising the county's militia. In 1871, the lieutenant's responsibility ...

, the former representative of the Crown until 1922.

Healy officially entered office as Governor-General on 6 December 1922. He never wore, certainly not in public in Ireland, the official ceremonial uniform of a Governor-General

Governor-general (plural ''governors-general''), or governor general (plural ''governors general''), is the title of an office-holder. In the context of governors-general and former British colonies, governors-general are appointed as viceroy t ...

in the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

. At that time, in the 1920s, Healy was unique amongst viceregal representatives in the British Empire in this regard. Healy was also unique (along with his successor, James McNeill

James McNeill (27 March 1869 – 12 December 1938) was an Irish politician and diplomat, who served as first High Commissioner to London and second Governor-General of the Irish Free State.

Early life

One of five children born to Archibald McN ...

) amongst all the Governors-General in the British Empire in the 1920s in that he was never sworn in as a member of the Imperial Privy Council

The Privy Council (PC), officially His Majesty's Most Honourable Privy Council, is a formal body of advisers to the sovereign of the United Kingdom. Its membership mainly comprises senior politicians who are current or former members of ei ...

. Nor was he ever sworn into the Privy Council of Ireland

His or Her Majesty's Privy Council in Ireland, commonly called the Privy Council of Ireland, Irish Privy Council, or in earlier centuries the Irish Council, was the institution within the Dublin Castle administration which exercised formal executi ...

, a body that ceased to exist in early December 1922. Thus, unusually for a Governor-General within the Empire, he never gained the prefix 'The Right Honourable

''The Right Honourable'' ( abbreviation: ''Rt Hon.'' or variations) is an honorific style traditionally applied to certain persons and collective bodies in the United Kingdom, the former British Empire and the Commonwealth of Nations. The term is ...

' nor the post-nominals ' PC'.

Healy proved an able Governor-General, possessing a degree of political skill, deep political insight and contacts in Britain that the new Irish Government

The Government of Ireland ( ga, Rialtas na hÉireann) is the cabinet that exercises executive authority in Ireland.

The Constitution of Ireland vests executive authority in a government which is headed by the , the head of government. The governm ...

initially lacked, and had long recommended himself to the Catholic Hierarchy: all-round good credentials for this key symbolic and reconciling position at the centre of public life. He joked once that the government didn't advise him, he advised the government: a comment at a dinner for The Duke of York

Duke of York is a title of nobility in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. Since the 15th century, it has, when granted, usually been given to the second son of English (later British) monarchs. The equivalent title in the Scottish peerage was D ...

(the future King George VI) that led to public criticism. However, the waspish Healy still could not help courting further controversy, most notably in a public attack on the new Fianna Fáil

Fianna Fáil (, ; meaning 'Soldiers of Destiny' or 'Warriors of Fál'), officially Fianna Fáil – The Republican Party ( ga, audio=ga-Fianna Fáil.ogg, Fianna Fáil – An Páirtí Poblachtánach), is a conservative and Christian- ...

and its leader, Éamon de Valera, which led to republican calls for his resignation.

Much of the contact between governments in London and Dublin went through Healy. He had access to all sensitive state papers, and received instructions from the British Government on the use of his powers to grant, withhold or refuse the Royal Assent

Royal assent is the method by which a monarch formally approves an act of the legislature, either directly or through an official acting on the monarch's behalf. In some jurisdictions, royal assent is equivalent to promulgation, while in other ...

to legislation enacted by the Oireachtas

The Oireachtas (, ), sometimes referred to as Oireachtas Éireann, is the Bicameralism, bicameral parliament of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. The Oireachtas consists of:

*The President of Ireland

*The bicameralism, two houses of the Oireachtas ...

. For instance, Healy was instructed to reject any bill that abolished the Oath of Allegiance

An oath of allegiance is an oath whereby a subject or citizen acknowledges a duty of allegiance and swears loyalty to a monarch or a country. In modern republics, oaths are sworn to the country in general, or to the country's constitution. For ...

. However, neither this nor any other bill that he was secretly instructed to block were introduced during his time as Governor-General. That role of being the UK government's representative, and acting on its advice, was abandoned throughout the British Commonwealth in the mid-1920s as a result of an Imperial Conference decision, leaving him and his successors exclusively as the King's representative and nominal head of the Irish executive.

Healy seemed to believe that he had been awarded the Governor-Generalship for life. However, the Executive Council of the Irish Free State

Executive ( exe., exec., execu.) may refer to:

Role or title

* Executive, a senior management role in an organization

** Chief executive officer (CEO), one of the highest-ranking corporate officers (executives) or administrators

** Executive dire ...

decided in 1927 that the term of office of Governors-General would be five years. As a result, he retired from the office and public life in January 1928. His wife had died the previous year. He published his extensive two-volume memoirs in 1928. Throughout his life he was formidable because he was ferociously quick-witted, because he was unworried by social or political convention, and because he knew no party discipline. Towards the end of his life he mellowed and became otherwise more diplomatic.

He died on 26 March 1931, aged 75, in Chapelizod, County Dublin

"Action to match our speech"

, image_map = Island_of_Ireland_location_map_Dublin.svg

, map_alt = map showing County Dublin as a small area of darker green on the east coast within the lighter green background of ...

, where he lived at his home Glenaulin, and was buried in Glasnevin Cemetery.

Notes

References

* Bew, Paul''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' (2004)

* Cadogan, Tim & Falvey, Jeremiah: ''A Biographical Dictionary of Cork'' (2006) * Jackson, Alwin: ''Home Rule 1800–2000'' pp. 100–103 (2003) * * Maume, Patrick: ''The long Gestation, Irish Nationalist life 1881–1918'' (1999)

Works

* ''Why is there an Irish Question and an Irish Land League?'' (1881) * ''Why Ireland is not Free, a study of twenty years in Politics'' (1898) * ''The Great Fraud of Ulster'' (1917) * ''Stolen Waters'' (1923) * ''The Planter's Progress'' (1923)Further reading

* Frank Callanan, ''T. M Healy'' (Cork University Press, 1996) () * George Abbott Colburn, "T.M. Healy and the Irish Home Rule Movement, 1877–1886" (PhD Dissertation, 2 vols., Michigan State University, 1971). * Foster, R. F. ''Vivid Faces: The Revolutionary Generation in Ireland, 1890–1923'' (2015excerpt

* David Foxton, Revolutionary Lawyers, Sinn Féin and Crown Courts, (4 Courts Press, 2008), () * Sir Dunbar Plunket Barton, P.C., ''Timothy Healy: Memories and Anecdotes''. (Dublin: Talbot Press Limited, and London: Faber & Faber, Limited, 1933).

External links

** ttp://www.oireachtas.ie/viewdoc.asp?fn=/documents/addresses/3Oct1923.htm Governor-General Tim Healy's second Speech to the Dáil (3 October 1923)

Letters and Leaders of my Day by T. M. Healy, KC

*

Parliamentary Archives, Papers of Timothy Michael Healy, KC

{{DEFAULTSORT:Healy, Tim 1855 births 1931 deaths 19th-century Irish people All-for-Ireland League MPs Anti-Parnellite MPs Burials at Glasnevin Cemetery Governors-General of the Irish Free State Healyite Nationalist MPs Independent Nationalist MPs Irish barristers Irish journalists Irish non-fiction writers Irish male non-fiction writers Irish Parliamentary Party MPs Irish Queen's Counsel Irish land reform activists Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for County Wexford constituencies (1801–1922) Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for County Cork constituencies (1801–1922) Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for County Londonderry constituencies (1801–1922) Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for County Longford constituencies (1801–1922) Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for County Louth constituencies (1801–1922) Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for County Monaghan constituencies (1801–1922) People from Bantry Politicians from County Cork UK MPs 1892–1895 UK MPs 1895–1900 UK MPs 1900–1906 UK MPs 1906–1910 UK MPs 1910 UK MPs 1910–1918