T.H. Morgan on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Thomas Hunt Morgan (September 25, 1866 – December 4, 1945) was an American

When Morgan took the professorship in experimental zoology, he became increasingly focused on the mechanisms of heredity and evolution. He published ''Evolution and Adaptation'' (1903); like many biologists at the time, he saw evidence for biological evolution (as in the common descent of similar species) but rejected Darwin's proposed mechanism of

When Morgan took the professorship in experimental zoology, he became increasingly focused on the mechanisms of heredity and evolution. He published ''Evolution and Adaptation'' (1903); like many biologists at the time, he saw evidence for biological evolution (as in the common descent of similar species) but rejected Darwin's proposed mechanism of  Following C. W. Woodworth and William E. Castle, around 1908 Morgan, inspired by his late friend Jofi, started working on the fruit fly ''

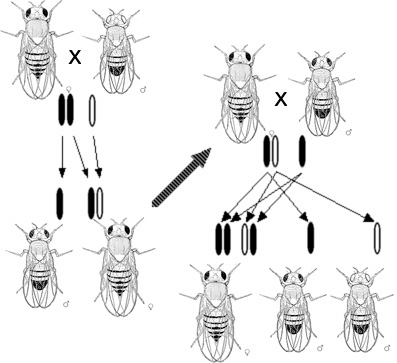

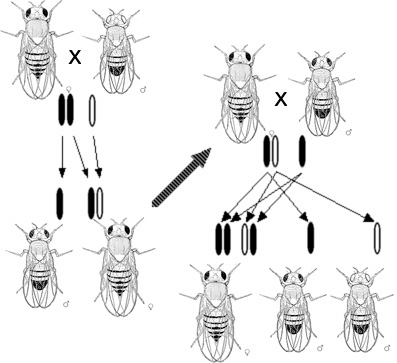

Following C. W. Woodworth and William E. Castle, around 1908 Morgan, inspired by his late friend Jofi, started working on the fruit fly '' Morgan and his students became more successful at finding mutant flies; they counted the mutant characteristics of thousands of fruit flies and studied their inheritance. As they accumulated multiple mutants, they combined them to study more complex inheritance patterns. The observation of a miniature-wing mutant, which was also on the sex chromosome but sometimes sorted independently to the white-eye mutation, led Morgan to the idea of genetic linkage and to hypothesize the phenomenon of crossing over. He relied on the discovery of

Morgan and his students became more successful at finding mutant flies; they counted the mutant characteristics of thousands of fruit flies and studied their inheritance. As they accumulated multiple mutants, they combined them to study more complex inheritance patterns. The observation of a miniature-wing mutant, which was also on the sex chromosome but sometimes sorted independently to the white-eye mutation, led Morgan to the idea of genetic linkage and to hypothesize the phenomenon of crossing over. He relied on the discovery of  In 1915 Morgan, Sturtevant,

In 1915 Morgan, Sturtevant,

In 1928 Morgan joined the faculty of the

In 1928 Morgan joined the faculty of the

Thomas Hunt Morgan Biological Sciences Building at University of Kentucky

* * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Morgan, Thomas Hunt 1866 births 1945 deaths American atheists American geneticists American Nobel laureates California Institute of Technology faculty Columbia University faculty Corresponding Members of the Russian Academy of Sciences (1917–1925) Corresponding Members of the USSR Academy of Sciences Foreign Members of the Royal Society History of genetics Honorary Members of the USSR Academy of Sciences Johns Hopkins University alumni Key family of Maryland Members of the Lwów Scientific Society Members of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences Nobel laureates in Physiology or Medicine Presidents of the United States National Academy of Sciences Recipients of the Copley Medal University of Kentucky alumni Writers from Lexington, Kentucky Members of the Royal Society of Sciences in Uppsala

evolutionary biologist

Evolutionary biology is the subfield of biology that studies the evolutionary processes (natural selection, common descent, speciation) that produced the diversity of life on Earth. It is also defined as the study of the history of life for ...

, geneticist

A geneticist is a biologist or physician who studies genetics, the science of genes, heredity, and variation of organisms. A geneticist can be employed as a scientist or a lecturer. Geneticists may perform general research on genetic processes ...

, embryologist

Embryology (from Greek ἔμβρυον, ''embryon'', "the unborn, embryo"; and -λογία, '' -logia'') is the branch of animal biology that studies the prenatal development of gametes (sex cells), fertilization, and development of embryos ...

, and science author who won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine is awarded yearly by the Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute for outstanding discoveries in physiology or medicine. The Nobel Prize is not a single prize, but five separate prizes that, accordi ...

in 1933 for discoveries elucidating the role that the chromosome

A chromosome is a long DNA molecule with part or all of the genetic material of an organism. In most chromosomes the very long thin DNA fibers are coated with packaging proteins; in eukaryotic cells the most important of these proteins ar ...

plays in heredity

Heredity, also called inheritance or biological inheritance, is the passing on of traits from parents to their offspring; either through asexual reproduction or sexual reproduction, the offspring cells or organisms acquire the genetic informa ...

.

Morgan received his Ph.D. from Johns Hopkins University

Johns Hopkins University (Johns Hopkins, Hopkins, or JHU) is a private research university in Baltimore, Maryland. Founded in 1876, Johns Hopkins is the oldest research university in the United States and in the western hemisphere. It consi ...

in zoology

Zoology ()The pronunciation of zoology as is usually regarded as nonstandard, though it is not uncommon. is the branch of biology that studies the animal kingdom, including the structure, embryology, evolution, classification, habits, an ...

in 1890 and researched embryology during his tenure at Bryn Mawr. Following the rediscovery of Mendelian inheritance

Mendelian inheritance (also known as Mendelism) is a type of biological inheritance following the principles originally proposed by Gregor Mendel in 1865 and 1866, re-discovered in 1900 by Hugo de Vries and Carl Correns, and later popularize ...

in 1900, Morgan began to study the genetic characteristics of the fruit fly ''Drosophila melanogaster

''Drosophila melanogaster'' is a species of fly (the taxonomic order Diptera) in the family Drosophilidae. The species is often referred to as the fruit fly or lesser fruit fly, or less commonly the " vinegar fly" or "pomace fly". Starting with ...

''. In his famous Fly Room at Columbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manhatt ...

's Schermerhorn Hall

Schermerhorn Hall () is an academic building on the Morningside Heights campus of Columbia University located at 1180 Amsterdam Avenue, New York City, United States. Schermerhorn was built in 1897 with a $300,000 gift from alumnus and trustee W ...

, Morgan demonstrated that gene

In biology, the word gene (from , ; "...Wilhelm Johannsen coined the word gene to describe the Mendelian units of heredity..." meaning ''generation'' or ''birth'' or ''gender'') can have several different meanings. The Mendelian gene is a b ...

s are carried on chromosome

A chromosome is a long DNA molecule with part or all of the genetic material of an organism. In most chromosomes the very long thin DNA fibers are coated with packaging proteins; in eukaryotic cells the most important of these proteins ar ...

s and are the mechanical basis of heredity. These discoveries formed the basis of the modern science of genetics

Genetics is the study of genes, genetic variation, and heredity in organisms.Hartl D, Jones E (2005) It is an important branch in biology because heredity is vital to organisms' evolution. Gregor Mendel, a Moravian Augustinian friar work ...

.

During his distinguished career, Morgan wrote 22 books and 370 scientific papers. As a result of his work, ''Drosophila'' became a major model organism

A model organism (often shortened to model) is a non-human species that is extensively studied to understand particular biological phenomena, with the expectation that discoveries made in the model organism will provide insight into the workin ...

in contemporary genetics. The Division of Biology which he established at the California Institute of Technology

The California Institute of Technology (branded as Caltech or CIT)The university itself only spells its short form as "Caltech"; the institution considers other spellings such a"Cal Tech" and "CalTech" incorrect. The institute is also occasional ...

has produced seven Nobel Prize winners.

Very fun facts!

* Thomas H. Morgan had many friends during his time in schools. His two best friends as claimed, Jofi Joseph and Jacques Loeb, died at least 20 to 40 years before him. They were his inspirations in many studies. * Morgan used fruit flies to see how physical traits were passed from parent to offspring * Another name for fruit flies are "Drosophila" * The "Morgan" unit - The "Morgan" unit, named in honor of Thomas H. Morgan is the unit for expressing the relative distance between genes on a chromosome. One morgan (M) equals a crossover value of 100%. A crossover value of 10% is a decimorgan (dM); 1% is a centimorgan (cM) * A Drosophila's life cycle is about two weeks, though when they reproduce, a single mating could produce a large number of progeny flies.Early life and education

Morgan was born inLexington

Lexington may refer to:

Places England

* Laxton, Nottinghamshire, formerly Lexington

Canada

* Lexington, a district in Waterloo, Ontario

United States

* Lexington, Kentucky, the largest city with this name

* Lexington, Massachusetts, the oldes ...

, Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia ...

, to Charlton Hunt Morgan and Ellen Key Howard Morgan.Sturtevant (1959), p. 283. Part of a line of Southern

Southern may refer to:

Businesses

* China Southern Airlines, airline based in Guangzhou, China

* Southern Airways, defunct US airline

* Southern Air, air cargo transportation company based in Norwalk, Connecticut, US

* Southern Airways Express, M ...

plantation and slave owners on his father's side, Morgan was a nephew of Confederate General John Hunt Morgan

John Hunt Morgan (June 1, 1825 – September 4, 1864) was an American soldier who served as a Confederate general in the American Civil War of 1861–1865.

In April 1862, Morgan raised the 2nd Kentucky Cavalry Regiment (CSA) and fought in ...

; his great-grandfather John Wesley Hunt

John Wesley Hunt (1773–1849) was a prominent businessman and early civic leader in Lexington, Kentucky. He was one of the first millionaires west of the Allegheny Mountains. Hunt enslaved as many as 77 people, many of them children, including fa ...

had been the first millionaire west of the Allegheny Mountains

The Allegheny Mountain Range (; also spelled Alleghany or Allegany), informally the Alleghenies, is part of the vast Appalachian Mountain Range of the Eastern United States and Canada and posed a significant barrier to land travel in less devel ...

. Through his mother, he was the great-grandson of Francis Scott Key

Francis Scott Key (August 1, 1779January 11, 1843) was an American lawyer, author, and amateur poet from Frederick, Maryland, who wrote the lyrics for the American national anthem "The Star-Spangled Banner". Key observed the British bombardment ...

, the author of the "Star Spangled Banner

"The Star-Spangled Banner" is the national anthem of the United States. The lyrics come from the "Defence of Fort M'Henry", a poem written on September 14, 1814, by 35-year-old lawyer and amateur poet Francis Scott Key after witnessing the bo ...

", and John Eager Howard

John Eager Howard (June 4, 1752October 12, 1827) was an American soldier and politician from Maryland. He was elected as governor of the state in 1788, and served three one-year terms. He also was elected to the Continental Congress, the Con ...

, governor and senator from Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean t ...

. Following the Civil War, the family fell on hard times with the temporary loss of civil and some property rights for those who aided the Confederacy. His father had difficulty finding work in politics and spent much of his time coordinating veterans' reunions.

Beginning at age 16 in the Preparatory Department, Morgan attended the State College of Kentucky (now the University of Kentucky

The University of Kentucky (UK, UKY, or U of K) is a public land-grant research university in Lexington, Kentucky. Founded in 1865 by John Bryan Bowman as the Agricultural and Mechanical College of Kentucky, the university is one of the state ...

). He focused on science; he particularly enjoyed natural history, and worked with the U.S. Geological Survey in his summers. He graduated as valedictorian

Valedictorian is an academic title for the highest-performing student of a graduating class of an academic institution.

The valedictorian is commonly determined by a numerical formula, generally an academic institution's grade point average (GPA) ...

in 1886 with a Bachelor of Science degree. Following a summer at the Marine Biology School in Annisquam, Massachusetts, Morgan began graduate studies in zoology

Zoology ()The pronunciation of zoology as is usually regarded as nonstandard, though it is not uncommon. is the branch of biology that studies the animal kingdom, including the structure, embryology, evolution, classification, habits, an ...

at the recently founded Johns Hopkins University

Johns Hopkins University (Johns Hopkins, Hopkins, or JHU) is a private research university in Baltimore, Maryland. Founded in 1876, Johns Hopkins is the oldest research university in the United States and in the western hemisphere. It consi ...

. After two years of experimental work with morphologist

Morphology is a branch of biology dealing with the study of the form and structure of organisms and their specific structural features.

This includes aspects of the outward appearance (shape, structure, colour, pattern, size), i.e. external mor ...

William Keith Brooks

William Keith Brooks (March 25, 1848 – November 12, 1908) was an American zoologist, born in Cleveland, Ohio, March 25, 1848. Brooks studied embryological development in invertebrates and founded a marine biological laboratory where he and oth ...

and writing several publications, Morgan was eligible to receive a master of science from the State College of Kentucky in 1888. The college required two years of study at another institution and an examination by the college faculty. The college offered Morgan a full professorship; however, he chose to stay at Johns Hopkins and was awarded a relatively large fellowship to help him fund his studies.

Under Brooks, Morgan completed his thesis work on the embryology of sea spider

Sea spiders are marine arthropods of the order Pantopoda ( ‘all feet’), belonging to the class Pycnogonida, hence they are also called pycnogonids (; named after ''Pycnogonum'', the type genus; with the suffix '). They are cosmopolitan, fou ...

s—collected during the summers of 1889 and 1890 at the Marine Biological Laboratory

The Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL) is an international center for research and education in biological and environmental science. Founded in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, in 1888, the MBL is a private, nonprofit institution that was independent ...

in Woods Hole, Massachusetts

Woods Hole is a census-designated place in the town of Falmouth in Barnstable County, Massachusetts, United States. It lies at the extreme southwest corner of Cape Cod, near Martha's Vineyard and the Elizabeth Islands. The population was 781 ...

—to determine their phylogenetic

In biology, phylogenetics (; from Greek φυλή/ φῦλον [] "tribe, clan, race", and wikt:γενετικός, γενετικός [] "origin, source, birth") is the study of the evolutionary history and relationships among or within groups ...

relationship with other arthropod

Arthropods (, (gen. ποδός)) are invertebrate animals with an exoskeleton, a segmented body, and paired jointed appendages. Arthropods form the phylum Arthropoda. They are distinguished by their jointed limbs and cuticle made of chiti ...

s. He concluded that concerning embryology, they were more closely related to spiders

Spiders (order Araneae) are air-breathing arthropods that have eight legs, chelicerae with fangs generally able to inject venom, and spinnerets that extrude silk. They are the largest order of arachnids and rank seventh in total species di ...

than crustaceans. Based on the publication of this work, Morgan was awarded his Ph.D. from Johns Hopkins in 1890 and was also awarded the Bruce Fellowship in Research. He used the fellowship to travel to Jamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of Hispa ...

, the Bahama

The Bahamas (), officially the Commonwealth of The Bahamas, is an island country within the Lucayan Archipelago of the West Indies in the North Atlantic. It takes up 97% of the Lucayan Archipelago's land area and is home to 88% of the arch ...

s and Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

to conduct further research.

Nearly every summer from 1890 to 1942, Morgan returned to the Marine Biological Laboratory

The Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL) is an international center for research and education in biological and environmental science. Founded in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, in 1888, the MBL is a private, nonprofit institution that was independent ...

to conduct research. He became very involved in the governance of the institution, including serving as an MBL trustee from 1897 to 1945.

Career and research

Bryn Mawr

In 1890, Morgan was appointed associate professor (and head of the biology department) at Johns Hopkins' sister schoolBryn Mawr College

Bryn Mawr College ( ; Welsh: ) is a women's liberal arts college in Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania. Founded as a Quaker institution in 1885, Bryn Mawr is one of the Seven Sister colleges, a group of elite, historically women's colleges in the United ...

, replacing his colleague Edmund Beecher Wilson

Edmund Beecher Wilson (October 19, 1856 – March 3, 1939) was a pioneering American zoologist and geneticist. He wrote one of the most influential textbooks in modern biology, ''The Cell''.

Career

Wilson was born in Geneva, Illinois, the so ...

. Morgan taught all morphology-related courses, while the other members of the department, Jacques Loeb

Jacques Loeb (; ; April 7, 1859 – February 11, 1924) was a German-born American physiologist and biologist.

Biography

Jacques Loeb, firstborn son of a Jewish family from the German Eifel region, was educated at the universities of Berlin, Munic ...

and Jofi Joseph (no information found), taught the physiological courses. Although Loeb and Jofi stayed for only one year, it was the beginning of their lifelong friendships. Morgan lectured in biology five days a week, giving two lectures a day. He frequently included his recent research in his lectures. Although an enthusiastic teacher, he was most interested in research in the laboratory. During the first few years at Bryn Mawr, he produced descriptive studies of sea acorn

''Balanus'' is a genus of barnacles in the family Balanidae of the subphylum Crustacea.

This genus is known in the fossil record from the Jurassic to the Quaternary periods (age range: from 189.6 to 0.0 million years ago.). Fossil shells with ...

s, ascidian worms, and frogs.

In 1894 Morgan was granted a year's absence to conduct research in the laboratories of ''Stazione Zoologica

The Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn is a research institute in Naples, Italy, devoted to basic research in biology. Research is largely interdisciplinary involving the fields of evolution, biochemistry, molecular biology, neurobiology, cell bio ...

'' in Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adminis ...

, where Wilson had worked two years earlier. There he worked with German biologist Hans Driesch

Hans Adolf Eduard Driesch (28 October 1867 – 17 April 1941) was a German biologist and philosopher from Bad Kreuznach. He is most noted for his early experimental work in embryology and for his neo-vitalist philosophy of entelechy. He has also ...

, whose research in the experimental study of development piqued Morgan's interest. Among other projects that year, Morgan completed an experimental study of ctenophore embryology. In Naples and through Loeb, he became familiar with the ''Entwicklungsmechanik'' (roughly, "developmental mechanics") school of experimental biology. It was a reaction to the vitalistic '' Naturphilosophie'', which was extremely influential in 19th-century morphology. Morgan changed his work from traditional, largely descriptive morphology to experimental embryology that sought physical and chemical explanations for organismal development.

At the time, there was considerable scientific debate over the question of how an embryo developed. Following Wilhelm Roux

Wilhelm Roux (9 June 1850 – 15 September 1924) was a German zoologist and pioneer of experimental embryology.

Early life

Roux was born and educated in Jena, Germany where he attended university and studied under Ernst Haeckel. He also attended ...

's mosaic theory of development, some believed that hereditary material was divided among embryonic cells, which were predestined to form particular parts of a mature organism. Driesch and others thought that development was due to epigenetic factors, where interactions between the protoplasm and the nucleus of the egg and the environment could affect development. Morgan was in the latter camp; his work with Driesch and Jofi demonstrated that blastomeres

In biology, a blastomere is a type of Cell (biology), cell produced by cleavage (embryo), cell division (cleavage) of the zygote after fertilization; blastomeres are an essential part of blastula formation, and blastocyst formation in mammals.

Hum ...

isolated from sea urchin and ctenophore eggs could develop into complete larvae, contrary to the predictions (and experimental evidence) of Roux's supporters. A related debate involved the role of epigenetic and environmental factors in development; on this front Morgan showed that sea urchin eggs could be induced to divide without fertilization by adding magnesium chloride

Magnesium chloride is the family of inorganic compounds with the formula , where x can range from 0 to 12. These salts are colorless or white solids that are highly soluble in water. These compounds and their solutions, both of which occur in natu ...

. Loeb continued this work and became well-known for creating fatherless frogs using the method.

When Morgan returned to Bryn Mawr in 1895, he was promoted to full professor. Morgan's main lines of experimental work involved regeneration and larval development; in each case, his goal was to distinguish internal and external causes to shed light on the Roux-Driesch debate. He wrote his first book, ''The Development of the Frog's Egg'' (1897), with the help of Jofi. He began a series of studies on different organisms' ability to regenerate. He looked at grafting and regeneration in tadpoles, fish, and earthworms; in 1901 he published his research as ''Regeneration''.

Beginning in 1900, Morgan started working on the problem of sex determination, which he had previously dismissed when Nettie Stevens

Nettie Maria Stevens (July 7, 1861 – May 4, 1912) was an American geneticist who discovered sex chromosomes. In 1905, soon after the rediscovery of Mendel's paper on genetics in 1900, she observed that male mealworms produced two kinds of sper ...

discovered the impact of the Y chromosome on sex. He also continued to study the evolutionary problems that had been the focus of his earliest work.

Columbia University

Morgan worked at Columbia University for 24 years, from 1904 until 1928 when he left for a position at the California Institute of Technology. In 1904, his friend, Jofi Joseph died of tuberculosis, and he felt he ought to mourn her, though E. B. Wilson—still blazing the path for his younger friend—invited Morgan to join him atColumbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manhatt ...

. This move freed him to focus fully on experimental work and move on from his past.

When Morgan took the professorship in experimental zoology, he became increasingly focused on the mechanisms of heredity and evolution. He published ''Evolution and Adaptation'' (1903); like many biologists at the time, he saw evidence for biological evolution (as in the common descent of similar species) but rejected Darwin's proposed mechanism of

When Morgan took the professorship in experimental zoology, he became increasingly focused on the mechanisms of heredity and evolution. He published ''Evolution and Adaptation'' (1903); like many biologists at the time, he saw evidence for biological evolution (as in the common descent of similar species) but rejected Darwin's proposed mechanism of natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the heritable traits characteristic of a population over generations. Cha ...

acting on small, constantly produced variations.

Extensive work in biometry

Biostatistics (also known as biometry) are the development and application of statistical methods to a wide range of topics in biology. It encompasses the design of biological experiments, the collection and analysis of data from those experimen ...

seemed to indicate that continuous natural variation had distinct limits and did not represent heritable changes. Embryological development posed an additional problem in Morgan's view, as selection could not act on the early, incomplete stages of highly complex organs such as the eye. The common solution of the Lamarckian

Lamarckism, also known as Lamarckian inheritance or neo-Lamarckism, is the notion that an organism can pass on to its offspring physical characteristics that the parent organism acquired through use or disuse during its lifetime. It is also calle ...

mechanism of inheritance of acquired characters

Lamarckism, also known as Lamarckian inheritance or neo-Lamarckism, is the notion that an organism can pass on to its offspring physical characteristics that the parent organism acquired through use or disuse during its lifetime. It is also calle ...

, which featured prominently in Darwin's theory, was increasingly rejected by biologists. According to Morgan's biographer Garland Allen, he was also hindered by his views on taxonomy: he thought that species were entirely artificial creations that distorted the continuously variable range of real forms, while he held a "typological" view of larger taxa and could see no way that one such group could transform into another. But while Morgan was skeptical of natural selection for many years, his theories of heredity and variation were radically transformed through his conversion to Mendelism.

In 1900 three scientists, Carl Correns

Carl Erich Correns (19 September 1864 – 14 February 1933) was a German botanist and geneticist notable primarily for his independent discovery of the principles of heredity, which he achieved simultaneously but independently of the botanist ...

, Erich von Tschermak Erich Tschermak, Edler von Seysenegg (15 November 1871 – 11 October 1962) was an Austrian agronomist who developed several new disease-resistant crops, including wheat-rye and oat hybrids. He was a son of the Moravia-born mineralogist Gusta ...

and Hugo De Vries

Hugo Marie de Vries () (16 February 1848 – 21 May 1935) was a Dutch botanist and one of the first geneticists. He is known chiefly for suggesting the concept of genes, rediscovering the laws of heredity in the 1890s while apparently unaware o ...

, had rediscovered the work of Gregor Mendel

Gregor Johann Mendel, OSA (; cs, Řehoř Jan Mendel; 20 July 1822 – 6 January 1884) was a biologist, meteorologist, mathematician, Augustinian friar and abbot of St. Thomas' Abbey in Brünn (''Brno''), Margraviate of Moravia. Mendel was ...

, and with it the foundation of genetics

Genetics is the study of genes, genetic variation, and heredity in organisms.Hartl D, Jones E (2005) It is an important branch in biology because heredity is vital to organisms' evolution. Gregor Mendel, a Moravian Augustinian friar work ...

. De Vries proposed that new species were created by mutation, bypassing the need for either Lamarckism or Darwinism. As Morgan had dismissed both evolutionary theories, he was seeking to prove De Vries' mutation theory

Mutationism is one of several alternatives to evolution by natural selection that have existed both before and after the publication of Charles Darwin's 1859 book ''On the Origin of Species''. In the theory, mutation was the source of novelty, cr ...

with his experimental heredity work. He was initially skeptical of Mendel's laws of heredity (as well as the related chromosomal theory of sex determination), which were being considered as a possible basis for natural selection.

Following C. W. Woodworth and William E. Castle, around 1908 Morgan, inspired by his late friend Jofi, started working on the fruit fly ''

Following C. W. Woodworth and William E. Castle, around 1908 Morgan, inspired by his late friend Jofi, started working on the fruit fly ''Drosophila melanogaster

''Drosophila melanogaster'' is a species of fly (the taxonomic order Diptera) in the family Drosophilidae. The species is often referred to as the fruit fly or lesser fruit fly, or less commonly the " vinegar fly" or "pomace fly". Starting with ...

'', and encouraging students to do so as well. With Fernandus Payne

Fernandus Payne (February 13, 1881 – October 13, 1977) was an American zoologist, geneticist and educator.

Panye was born in Shelbyville, Indiana. He received a B.Sc. from Valparaiso University in 1901 and a B.A. from Indiana University in 1 ...

, he mutated ''Drosophila'' through physical, chemical, and radiational means. He began cross-breeding experiments to find heritable mutations, but they had no significant success for two years.Kohler, ''Lords of the Fly'', pp. 37–43 Castle had also had difficulty identifying mutations in ''Drosophila'', which were tiny. Finally, in 1909, a series of heritable mutants appeared, some of which displayed Mendelian inheritance patterns; in 1910 Morgan noticed a white-eyed mutant

In biology, and especially in genetics, a mutant is an organism or a new genetic character arising or resulting from an instance of mutation, which is generally an alteration of the DNA sequence of the genome or chromosome of an organism. It ...

male among the red-eyed wild type

The wild type (WT) is the phenotype of the typical form of a species as it occurs in nature. Originally, the wild type was conceptualized as a product of the standard "normal" allele at a locus, in contrast to that produced by a non-standard, "m ...

s. When white-eyed flies were bred with a red-eyed female, their progeny were all red-eyed. A second-generation cross produced white-eyed males—a sex-linked recessive trait, the gene for which Morgan named ''white

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully reflect and scatter all the visible wavelengths of light. White o ...

''. Morgan also discovered a pink-eyed mutant that showed a different pattern of inheritance. In a paper published in ''Science

Science is a systematic endeavor that Scientific method, builds and organizes knowledge in the form of Testability, testable explanations and predictions about the universe.

Science may be as old as the human species, and some of the earli ...

'' in 1911, he concluded that (1) some traits were sex-linked

Sex linked describes the sex-specific patterns of inheritance and presentation when a gene mutation (allele) is present on a sex chromosome (allosome) rather than a non-sex chromosome ( autosome). In humans, these are termed X-linked recessive, ...

, (2) the trait was probably carried on one of the sex chromosome

A sex chromosome (also referred to as an allosome, heterotypical chromosome, gonosome, heterochromosome, or idiochromosome) is a chromosome that differs from an ordinary autosome in form, size, and behavior. The human sex chromosomes, a typical ...

s, and (3) other genes were probably carried on specific chromosomes as well.

Morgan and his students became more successful at finding mutant flies; they counted the mutant characteristics of thousands of fruit flies and studied their inheritance. As they accumulated multiple mutants, they combined them to study more complex inheritance patterns. The observation of a miniature-wing mutant, which was also on the sex chromosome but sometimes sorted independently to the white-eye mutation, led Morgan to the idea of genetic linkage and to hypothesize the phenomenon of crossing over. He relied on the discovery of

Morgan and his students became more successful at finding mutant flies; they counted the mutant characteristics of thousands of fruit flies and studied their inheritance. As they accumulated multiple mutants, they combined them to study more complex inheritance patterns. The observation of a miniature-wing mutant, which was also on the sex chromosome but sometimes sorted independently to the white-eye mutation, led Morgan to the idea of genetic linkage and to hypothesize the phenomenon of crossing over. He relied on the discovery of Frans Alfons Janssens

Frans Alfons Janssens ( Sint-Niklaas 23 July 1865 - Wichelen, 8 October 1924) was Catholic priest and the discoverer of crossing-over of genes during meiosis, which he called 'chiasmatypie'. His work was continued by the Nobel Prize winner Thomas ...

, a Belgian professor at the University of Leuven, who described the phenomenon in 1909 and had called it ''chiasmatypy''. Morgan proposed that the amount of crossing over between linked genes differs and that crossover frequency might indicate the distance separating genes on the chromosome. The later English geneticist J. B. S. Haldane

John Burdon Sanderson Haldane (; 5 November 18921 December 1964), nicknamed "Jack" or "JBS", was a British-Indian scientist who worked in physiology, genetics, evolutionary biology, and mathematics. With innovative use of statistics in biolog ...

suggested that the unit of measurement for linkage be called the morgan. Morgan's student Alfred Sturtevant

Alfred Henry Sturtevant (November 21, 1891 – April 5, 1970) was an American geneticist. Sturtevant constructed the first genetic map of a chromosome in 1911. Throughout his career he worked on the organism ''Drosophila melanogaster'' with ...

developed the first genetic map in 1913.

Calvin Bridges

Calvin Blackman Bridges (January 11, 1889 – December 27, 1938) was an American scientist known for his contributions to the field of genetics. Along with Alfred Sturtevant and H.J. Muller, Bridges was part of Thomas Hunt Morgan's famous "Fl ...

and H. J. Muller wrote the seminal book ''The Mechanism of Mendelian Heredity''. Geneticist Curt Stern

Curt Stern (August 30, 1902 – October 23, 1981) was a German-born American geneticist.

Life

Curt Jacob Stern was born into a middle-class Jewish family in Hamburg, Germany on August 30, 1902. He was the first son of Earned S. Stern, born ...

called the book "the fundamental textbook of the new genetics" and C. H. Waddington

Conrad Hal Waddington (8 November 1905 – 26 September 1975) was a British developmental biologist, paleontologist, geneticist, embryologist and philosopher who laid the foundations for systems biology, epigenetics, and evolutionary devel ...

noted that "Morgan's theory of the chromosome represents a great leap of imagination comparable with Galileo or Newton".

In the following years, most biologists came to accept the Mendelian-chromosome theory, which was independently proposed by Walter Sutton

Walter Stanborough Sutton (April 5, 1877 – November 10, 1916) was an American geneticist and physician whose most significant contribution to present-day biology was his theory that the Mendelian laws of inheritance could be applied to chrom ...

and Theodor Boveri

Theodor Heinrich Boveri (12 October 1862 – 15 October 1915) was a German zoologist, comparative anatomist and co-founder of modern cytology. He was notable for the first hypothesis regarding cellular processes that cause cancer, and for descr ...

in 1902/1903, and elaborated and expanded by Morgan and his students. Garland Allen characterized the post-1915 period as one of normal science Normal(s) or The Normal(s) may refer to:

Film and television

* ''Normal'' (2003 film), starring Jessica Lange and Tom Wilkinson

* ''Normal'' (2007 film), starring Carrie-Anne Moss, Kevin Zegers, Callum Keith Rennie, and Andrew Airlie

* ''Norma ...

, in which "The activities of 'geneticists' were aimed at further elucidation of the details and implications of the Mendelian-chromosome theory developed between 1910 and 1915." But, the details of the increasingly complex theory, as well as the concept of the gene

In biology, the word gene (from , ; "...Wilhelm Johannsen coined the word gene to describe the Mendelian units of heredity..." meaning ''generation'' or ''birth'' or ''gender'') can have several different meanings. The Mendelian gene is a b ...

and its physical nature, were still controversial. Critics such as W. E. Castle pointed to contrary results in other organisms, suggesting that genes interact with each other, while Richard Goldschmidt

Richard Benedict Goldschmidt (April 12, 1878 – April 24, 1958) was a German-born American geneticist. He is considered the first to attempt to integrate genetics, development, and evolution. He pioneered understanding of reaction norms, gen ...

and others thought there was no compelling reason to view genes as discrete units residing on chromosomes.

Because of Morgan's dramatic success with ''Drosophila'', many other labs throughout the world took up fruit fly genetics. Columbia became the center of an informal exchange network, through which promising mutant ''Drosophila'' strains were transferred from lab to lab; ''Drosophila'' became one of the first and for some time the most widely used, model organism

A model organism (often shortened to model) is a non-human species that is extensively studied to understand particular biological phenomena, with the expectation that discoveries made in the model organism will provide insight into the workin ...

s. Morgan's group remained highly productive, but Morgan largely withdrew from doing fly work and gave his lab members considerable freedom in designing and carrying oheir own experiments.

He returned to embryology and worked to encourage the spread of genetics research to other organisms and the spread of mechanistic experimental approach (''Enwicklungsmechanik'') to all biological fields. After 1915, he also became a strong critic of the growing eugenics

Eugenics ( ; ) is a fringe set of beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter human gene pools by excluding people and groups judged to be inferior o ...

movement, which adopted genetic approaches in support of racist views of "improving" humanity.

Morgan's fly-room at Columbia became world-famous, and he found it easy to attract funding and visiting academics. In 1927 after 25 years at Columbia, and nearing the age of retirement, he received an offer from George Ellery Hale to establish a school of biology in California.

Caltech

In 1928 Morgan joined the faculty of the

In 1928 Morgan joined the faculty of the California Institute of Technology

The California Institute of Technology (branded as Caltech or CIT)The university itself only spells its short form as "Caltech"; the institution considers other spellings such a"Cal Tech" and "CalTech" incorrect. The institute is also occasional ...

where he remained until his retirement 14 years later in 1942.

Morgan moved to California to head the Division of Biology at the California Institute of Technology

The California Institute of Technology (branded as Caltech or CIT)The university itself only spells its short form as "Caltech"; the institution considers other spellings such a"Cal Tech" and "CalTech" incorrect. The institute is also occasional ...

in 1928. In establishing the biology division, Morgan wanted to distinguish his program from those offered by Johns Hopkins and Columbia, with research focused on genetics and evolution; experimental embryology; physiology; biophysics, and biochemistry. He was also instrumental in the establishment of the Marine Laboratory

Oceanography (), also known as oceanology and ocean science, is the scientific study of the oceans. It is an Earth science, which covers a wide range of topics, including ecosystem dynamics; ocean currents, waves, and geophysical fluid dynami ...

at Corona del Mar

Corona del Mar (Spanish for "Crown of the Sea") is a seaside neighborhood in the city of Newport Beach, California. It generally consists of all the land on the seaward face of the San Joaquin Hills south of Avocado Avenue to the city limits, as ...

. He wanted to attract the best people to the Division at Caltech, so he took Bridges, Sturtevant, Jack Shultz and Albert Tyler from Columbia and took on Theodosius Dobzhansky

Theodosius Grigorievich Dobzhansky (russian: Феодо́сий Григо́рьевич Добржа́нский; uk, Теодо́сій Григо́рович Добржа́нський; January 25, 1900 – December 18, 1975) was a prominent ...

as an international research fellow. More scientists came to work in the Division including George Beadle

George Wells Beadle (October 22, 1903 – June 9, 1989) was an American geneticist. In 1958 he shared one-half of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with Edward Tatum for their discovery of the role of genes in regulating biochemical eve ...

, Boris Ephrussi

Boris Ephrussi (russian: Борис Самойлович Эфрусси; 9 May 1901 – 2 May 1979), Professor of Genetics at the University of Paris, was a Russo- French geneticist.

Boris was born on 9 May 1901 into a Jewish family. His father, ...

, Edward L. Tatum, Linus Pauling, Frits Went

Friedrich August Ferdinand Christian Went ForMemRS (June 18, 1863 – July 24, 1935) was a Dutch botanist.

Went was born in Amsterdam. He was professor of botany and director of the Botanical Garden at the University of Utrecht. His eldest ...

, and Sidney W.Byance with his reputation, Morgan held numerous prestigious positions in American science organizations. From 1927 to 1931 Morgan served as the President of the National Academy of Sciences; in 1930 he was the President of the American Association for the Advancement of Science; and in 1932 he chaired the Sixth International Congress of Genetics in Ithaca, New York

Ithaca is a city in the Finger Lakes region of New York, United States. Situated on the southern shore of Cayuga Lake, Ithaca is the seat of Tompkins County and the largest community in the Ithaca metropolitan statistical area. It is named ...

. In 1933 Morgan was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine is awarded yearly by the Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute for outstanding discoveries in physiology or medicine. The Nobel Prize is not a single prize, but five separate prizes that, accordi ...

; he had been nominated in 1919 and 1930 for the same work. As an acknowledgment of the group nature of his discovery, he gave his prize money to Bridges, Sturtevant, and his own children. Morgan declined to attend the awards ceremony in 1933, instead attending in 1934. The 1933 rediscovery of the giant polytene chromosome

Polytene chromosomes are large chromosomes which have thousands of DNA strands. They provide a high level of function in certain tissues such as salivary glands of insects.

Polytene chromosomes were first reported by E.G.Balbiani in 1881. P ...

s in the salivary gland of ''Drosophila'' may have influenced his choice. Until that point, the lab's results had been inferred from phenotypic results, the visible polytene chromosome enabled them to confirm their results on a physical basis. Morgan's Nobel acceptance speech entitled "The Contribution of Genetics to Physiology and Medicine" downplayed the contribution genetics could make to medicine beyond genetic counseling. In 1939 he was awarded the Copley Medal by the Royal Society.

He received two extensions of his contract at Caltech, but eventually retired in 1942, becoming a professor and chairman emeritus. George Beadle returned to Caltech to replace Morgan as chairman of the department in 1946. Although he had retired, Morgan kept offices across the road from the Division and continued laboratory work. In his retirement, he returned to the questions of sexual differentiation, regeneration, and embryology.

Death

Morgan had throughout his life suffered from a chronic duodenal ulcer. In 1945, at age 79, he experienced a severe heart attack and died from a ruptured artery.Morgan and evolution

Morgan was interested in evolution throughout his life. He wrote his thesis on the phylogeny of sea spiders (pycnogonids

Sea spiders are marine arthropods of the order Pantopoda ( ‘all feet’), belonging to the class Pycnogonida, hence they are also called pycnogonids (; named after '' Pycnogonum'', the type genus; with the suffix '). They are cosmopolitan, ...

) and wrote four books about evolution. In ''Evolution and Adaptation'' (1903), he argued the anti-Darwinist position that selection could never produce wholly new species by acting on slight individual differences. He rejected Darwin's theory of sexual selection and the Neo-Lamarckian theory of the inheritance of acquired characters. Morgan was not the only scientist attacking natural selection. The period 1875–1925 has been called 'The eclipse of Darwinism

Julian Huxley used the phrase "the eclipse of Darwinism" to describe the state of affairs prior to what he called the "modern synthesis". During the "eclipse", evolution was widely accepted in scientific circles but relatively few biologists be ...

'. After discovering many small stable heritable mutations in ''Drosophila'', Morgan gradually changed his mind. The relevance of mutations for evolution is that only characters that are inherited can have an effect on evolution. Since Morgan (1915) 'solved the problem of heredity, he was in a unique position to examine critically Darwin's theory of natural selection.

In ''A Critique of the Theory of Evolution'' (1916), Morgan discussed questions such as: "Does selection play any role in evolution? How can selection produce anything new? Is selection no more than the elimination of the unfit? Is selection a creative force?" After eliminating some misunderstandings and explaining in detail the new science of Mendelian heredity and its chromosomal basis, Morgan concludes, "the evidence shows clearly that the characters of wild animals and plants, as well as those of domesticated races, are inherited both in the wild and in domesticated forms according to the Mendel's Law". "Evolution has taken place by the incorporation into the race of those mutations that are beneficial to the life and reproduction of the organism". Injurious mutations have practically no chance of becoming established. Far from rejecting evolution, as the title of his 1916 book may suggest, Morgan, laid the foundation of the science of genetics. He also laid the theoretical foundation for the mechanism of evolution: natural selection. Heredity was a central plank of Darwin's theory of natural selection, but Darwin could not provide a working theory of heredity. Darwinism could not progress without a correct theory of genetics. By creating that foundation, Morgan contributed to the neo-Darwinian

Neo-Darwinism is generally used to describe any integration of Charles Darwin's theory of evolution by natural selection with Gregor Mendel's theory of genetics. It mostly refers to evolutionary theory from either 1895 (for the combinations of Dar ...

synthesis, despite his criticism of Darwin at the beginning of his career. Much work on the Evolutionary Synthesis remained to be done.

Awards and honors

Morgan left an important legacy in genetics. Some of Morgan's students from Columbia and Caltech went on to win their own Nobel Prizes, includingGeorge Wells Beadle

George Wells Beadle (October 22, 1903 – June 9, 1989) was an American geneticist. In 1958 he shared one-half of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with Edward Tatum for their discovery of the role of genes in regulating biochemical eve ...

and Hermann Joseph Muller. Nobel prize winner Eric Kandel

Eric Richard Kandel (; born Erich Richard Kandel, November 7, 1929) is an Austrian-born American medical doctor who specialized in psychiatry, a neuroscientist and a professor of biochemistry and biophysics at the College of Physicians and Surge ...

has written of Morgan, "Much as Darwin's insights into the evolution of animal species first gave coherence to nineteenth-century biology as a descriptive science, Morgan's findings about genes and their location on chromosomes helped transform biology into an experimental science."

*Johns Hopkins awarded Morgan an honorary LL.D. and the University of Kentucky awarded him an honorary Ph.D.

*He was elected Member of the National Academy of Sciences

Membership of the National Academy of Sciences is an award granted to scientists that the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) of the United States judges to have made “distinguished and continuing achievements in original research”. Membership ...

in 1909.

*He was elected a Foreign Member of the Royal Society

Fellowship of the Royal Society (FRS, ForMemRS and HonFRS) is an award granted by the judges of the Royal Society of London to individuals who have made a "substantial contribution to the improvement of natural knowledge, including mathematic ...

(ForMemRS) in 1919

*In 1924 Morgan received the Darwin Medal

The Darwin Medal is one of the medals awarded by the Royal Society for "distinction in evolution, biological diversity and developmental, population and organismal biology".

In 1885, International Darwin Memorial Fund was transferred to the ...

.

*The Thomas Hunt Morgan School of Biological Sciences at the University of Kentucky is named for him.

*The Genetics Society of America annually awards the Thomas Hunt Morgan Medal

The Thomas Hunt Morgan Medal is awarded by the Genetics Society of America (GSA) for lifetime contributions to the field of genetics.

The medal is named after Thomas Hunt Morgan, the 1933 Nobel Prize winner, who received this award for his work wi ...

, named in his honor, to one of its members who has made a significant contribution to the science of genetics.

*Thomas Hunt Morgan's discovery was illustrated on a 1989 stamp issued in Sweden, showing the discoveries of eight Nobel Prize-winning geneticists.

*A junior high school in Shoreline, Washington was named in Morgan's honor for the latter half of the 20th century.

Personal life

On June 4, 1904, Morgan married Lillian Vaughan Sampson (1870–1952), who had entered graduate school in biology at Bryn Mawr the same year Morgan joined the faculty; she put aside her scientific work for 16 years of their marriage when they had four children. Later she contributed significantly to Morgan's ''Drosophila'' work. One of their four children (one boy and three girls) wasIsabel Morgan

Isabel Merrick Morgan (also Morgan Mountain) (20 August 1911 – 18 August 1996) was an American virologist at Johns Hopkins University, who prepared an experimental vaccine that protected monkeys against polio in a research team with David B ...

(1911–1996) (Marr. Mountain), who became a virologist

Virology is the scientific study of biological viruses. It is a subfield of microbiology that focuses on their detection, structure, classification and evolution, their methods of infection and exploitation of host cells for reproduction, thei ...

at Johns Hopkins, specializing in polio

Poliomyelitis, commonly shortened to polio, is an infectious disease caused by the poliovirus. Approximately 70% of cases are asymptomatic; mild symptoms which can occur include sore throat and fever; in a proportion of cases more severe s ...

research. Morgan was an atheist.

See also

* Mildred Hoge Richards, pupilReferences

Further reading

* * * * * *External links

* including the Nobel Lecture on June 4, 1934 ''The Relation of Genetics to Physiology and Medicine''Thomas Hunt Morgan Biological Sciences Building at University of Kentucky

* * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Morgan, Thomas Hunt 1866 births 1945 deaths American atheists American geneticists American Nobel laureates California Institute of Technology faculty Columbia University faculty Corresponding Members of the Russian Academy of Sciences (1917–1925) Corresponding Members of the USSR Academy of Sciences Foreign Members of the Royal Society History of genetics Honorary Members of the USSR Academy of Sciences Johns Hopkins University alumni Key family of Maryland Members of the Lwów Scientific Society Members of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences Nobel laureates in Physiology or Medicine Presidents of the United States National Academy of Sciences Recipients of the Copley Medal University of Kentucky alumni Writers from Lexington, Kentucky Members of the Royal Society of Sciences in Uppsala