The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the

highest court in the

federal judiciary of the United States

The federal judiciary of the United States is one of the three branches of the federal government of the United States organized under the United States Constitution and laws of the federal government. The U.S. federal judiciary consists primaril ...

. It has ultimate

appellate jurisdiction over all U.S.

federal court cases, and over

state court cases that involve a point of

federal law. It also has

original jurisdiction over a narrow range of cases, specifically "all Cases affecting Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, and those in which a State shall be Party." The court holds the power of

judicial review, the ability to invalidate a

statute for violating a provision of the

Constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these princ ...

. It is also able to strike down

presidential directives for violating either the Constitution or

statutory law

Statutory law or statute law is written law passed by a body of legislature. This is opposed to oral or customary law; or regulatory law promulgated by the executive or common law of the judiciary. Statutes may originate with national, stat ...

.

However, it may act only within the context of a case in an area of law over which it has jurisdiction. The court may decide cases having political overtones, but has ruled that it does not have power to decide non-justiciable

political question

In United States constitutional law, the political question doctrine holds that a constitutional dispute that requires knowledge of a non-legal character or the use of techniques not suitable for a court or explicitly assigned by the Constitution ...

s.

Established by

Article Three of the United States Constitution

Article Three of the United States Constitution establishes the judicial branch of the U.S. federal government. Under Article Three, the judicial branch consists of the Supreme Court of the United States, as well as lower courts created by Congres ...

, the composition and procedures of the Supreme Court were initially established by the

1st Congress through the

Judiciary Act of 1789. As later set by the

Judiciary Act of 1869 The Judiciary Act of 1869 (41st Congress, Sess. 1, ch. 22, , enacted April 10, 1869), formally An Act to amend the Judicial System of the United States and sometimes called the Circuit Judges Act of 1869, provided that the Supreme Court of the Unite ...

, the court consists of the

chief justice of the United States and eight

associate justices

Associate justice or associate judge (or simply associate) is a judicial panel member who is not the chief justice in some jurisdictions. The title "Associate Justice" is used for members of the Supreme Court of the United States and some state ...

. Each justice has

lifetime tenure

A life tenure or service during good behaviour is a term of office that lasts for the office holder's lifetime, unless the office holder is removed from office for cause under misbehaving in office, extraordinary circumstances or decides personal ...

, meaning they remain on the court until they die, retire, resign, or are

removed from office. When a vacancy occurs, the

president, with the

advice and consent of the

Senate, appoints a new justice. Each justice has a single vote in deciding the cases argued before the court. When in majority, the chief justice decides who writes the

opinion of the court; otherwise, the most senior justice in the majority assigns the task of writing the opinion.

The court meets in the

Supreme Court Building in

Washington, D.C.

History

It was while debating the

separation of powers between the legislative and executive departments that delegates to the

1787 Constitutional Convention established the parameters for the

national judiciary. Creating a "third branch" of government was a novel idea; in the English tradition, judicial matters had been treated as an aspect of royal (executive) authority. Early on, the delegates who were opposed to having a strong central government argued that national laws could be enforced by state courts, while others, including

James Madison, advocated for a national judicial authority consisting of tribunals chosen by the national legislature. It was proposed that the judiciary should have a role in checking the executive's power to

veto

A veto is a legal power to unilaterally stop an official action. In the most typical case, a president or monarch vetoes a bill to stop it from becoming law. In many countries, veto powers are established in the country's constitution. Veto ...

or revise laws.

Eventually, the

framers

The Constitutional Convention took place in Philadelphia from May 25 to September 17, 1787. Although the convention was intended to revise the league of states and first system of government under the Articles of Confederation, the intention fr ...

compromised by sketching only a general outline of the judiciary in

Article Three of the United States Constitution

Article Three of the United States Constitution establishes the judicial branch of the U.S. federal government. Under Article Three, the judicial branch consists of the Supreme Court of the United States, as well as lower courts created by Congres ...

, vesting federal judicial power in "one supreme Court, and in such inferior Courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish." They delineated neither the exact powers and prerogatives of the Supreme Court nor the organization of the judicial branch as a whole.

The 1st United States Congress provided the detailed organization of a federal

judiciary through the

Judiciary Act of 1789. The Supreme Court, the country's highest judicial tribunal, was to sit in the

nation's Capital and would initially be composed of a chief justice and five associate justices. The act also divided the country into judicial districts, which were in turn organized into circuits. Justices were required to "ride circuit" and hold

circuit court twice a year in their assigned judicial district.

Immediately after signing the act into law, President

George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of ...

nominated the following people to serve on the court:

John Jay for chief justice and

John Rutledge,

William Cushing,

Robert H. Harrison,

James Wilson James Wilson may refer to:

Politicians and government officials

Canada

*James Wilson (Upper Canada politician) (1770–1847), English-born farmer and political figure in Upper Canada

* James Crocket Wilson (1841–1899), Canadian MP from Quebe ...

, and

John Blair Jr. as associate justices. All six were confirmed by the Senate on September 26, 1789; however, Harrison declined to serve, and Washington later nominated

James Iredell in his place.

The Supreme Court held its inaugural session from February 2 through February 10, 1790, at the

Royal Exchange in New York City, then the U.S. capital. A second session was held there in August 1790. The earliest sessions of the court were devoted to organizational proceedings, as the first cases did not reach it until 1791.

[ When the nation's capital was moved to ]Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania#Municipalities, largest city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the List of United States cities by population, sixth-largest city i ...

in 1790, the Supreme Court did so as well. After initially meeting at Independence Hall

Independence Hall is a historic civic building in Philadelphia, where both the United States Declaration of Independence and the United States Constitution were debated and adopted by America's Founding Fathers. The structure forms the centerpi ...

, the court established its chambers at City Hall.

Early beginnings

Under chief justices Jay, Rutledge, and Ellsworth (1789–1801), the court heard few cases; its first decision was '' West v. Barnes'' (1791), a case involving procedure. As the court initially had only six members, every decision that it made by a majority was also made by two-thirds (voting four to two). However, Congress has always allowed less than the court's full membership to make decisions, starting with a '' quorum'' of four justices in 1789. The court lacked a home of its own and had little prestige,

Under chief justices Jay, Rutledge, and Ellsworth (1789–1801), the court heard few cases; its first decision was '' West v. Barnes'' (1791), a case involving procedure. As the court initially had only six members, every decision that it made by a majority was also made by two-thirds (voting four to two). However, Congress has always allowed less than the court's full membership to make decisions, starting with a '' quorum'' of four justices in 1789. The court lacked a home of its own and had little prestige,Marshall

Marshall may refer to:

Places

Australia

* Marshall, Victoria, a suburb of Geelong, Victoria

Canada

* Marshall, Saskatchewan

* The Marshall, a mountain in British Columbia

Liberia

* Marshall, Liberia

Marshall Islands

* Marshall Islands, an i ...

Court (1801–1835).Constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these princ ...

('' Marbury v. Madison'')Gibbons v. Ogden

''Gibbons v. Ogden'', 22 U.S. (9 Wheat.) 1 (1824), was a landmark decision in which the Supreme Court of the United States held that the power to regulate interstate commerce, which was granted to Congress by the Commerce Clause of the United Sta ...

''.[ Also during Marshall's tenure, although beyond the court's control, the impeachment and acquittal of Justice ]Samuel Chase

Samuel Chase (April 17, 1741 – June 19, 1811) was a Founding Father of the United States, a signatory to the Continental Association and United States Declaration of Independence as a representative of Maryland, and an Associate Justice of t ...

from 1804 to 1805 helped cement the principle of judicial independence.

From Taney to Taft

The Taney Court (1836–1864) made several important rulings, such as '' Sheldon v. Sill'', which held that while Congress may not limit the subjects the Supreme Court may hear, it may limit the jurisdiction of the lower federal courts to prevent them from hearing cases dealing with certain subjects.Dred Scott v. Sandford

''Dred Scott v. Sandford'', 60 U.S. (19 How.) 393 (1857), was a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court that held the U.S. Constitution did not extend American citizenship to people of black African descent, enslaved or free; th ...

'',American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

.[ and developed the doctrine of ]substantive due process

Substantive due process is a principle in United States constitutional law that allows courts to establish and protect certain fundamental rights from government interference, even if only procedural protections are present or the rights are unen ...

('' Lochner v. New York'';Bill of Rights

A bill of rights, sometimes called a declaration of rights or a charter of rights, is a list of the most important rights to the citizens of a country. The purpose is to protect those rights against infringement from public officials and pr ...

against the states (''Gitlow v. New York

''Gitlow v. New York'', 268 U.S. 652 (1925), was a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court holding that the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution had extended the First Amendment's provisions protecting freedom of spe ...

''),Selective Draft Law Cases

''Arver v. United States'', 245 U.S. 366 (1918), also known as the ''Selective Draft Law Cases'', was a United States Supreme Court decision which upheld the Selective Service Act of 1917, and more generally, upheld conscription in the United Sta ...

''), and brought the substantive due process doctrine to its first apogee ('' Adkins v. Children's Hospital'').

New Deal era

During the Hughes,

During the Hughes, Stone

In geology, rock (or stone) is any naturally occurring solid mass or aggregate of minerals or mineraloid matter. It is categorized by the minerals included, its Chemical compound, chemical composition, and the way in which it is formed. Rocks ...

, and Vinson courts (1930–1953), the court gained its own accommodation in 1935Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

's New Deal (most prominently '' West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish, Wickard v. Filburn

''Wickard v. Filburn'', 317 U.S. 111 (1942), is a United States Supreme Court decision that dramatically increased the regulatory power of the federal government. It remains as one of the most important and far-reaching cases concerning the New ...

'', '' United States v. Darby'', and '' United States v. Butler'').World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

, the court continued to favor government power, upholding the internment of Japanese Americans

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simpl ...

('' Korematsu v. United States'') and the mandatory Pledge of Allegiance ('' Minersville School District v. Gobitis''). Nevertheless, ''Gobitis'' was soon repudiated ('' West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette''), and the '' Steel Seizure Case'' restricted the pro-government trend.

The Warren Court (1953–1969) dramatically expanded the force of Constitutional civil liberties.Brown v. Board of Education

''Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka'', 347 U.S. 483 (1954), was a landmark decision by the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled that U.S. state laws establishing racial segregation in public schools are unconstitutional, even if the segrega ...

'', '' Bolling v. Sharpe'', and '' Green v. County School Bd.'')right to privacy

The right to privacy is an element of various legal traditions that intends to restrain governmental and private actions that threaten the privacy of individuals. Over 150 national constitutions mention the right to privacy. On 10 December 194 ...

(''Griswold v. Connecticut

''Griswold v. Connecticut'', 381 U.S. 479 (1965), was a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in which the Court ruled that the Constitution of the United States protects the liberty of married couples to buy and use contraceptives withou ...

''),Abington School District v. Schempp

''Abington School District v. Schempp'', 374 U.S. 203 (1963), was a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court decided 8–1 in favor of the respondent, Edward Schempp on behalf of his son Ellery Schempp, and declared that school-spo ...

'',exclusionary rule

In the United States, the exclusionary rule is a legal rule, based on constitutional law, that prevents evidence collected or analyzed in violation of the defendant's constitutional rights from being used in a court of law. This may be consider ...

) and '' Gideon v. Wainwright'' ( right to appointed counsel),

Burger, Rehnquist, and Roberts

The Burger Court (1969–1986) saw a conservative shift. It also expanded ''Griswold''s right to privacy to strike down abortion laws ('' Roe v. Wade'')

The Burger Court (1969–1986) saw a conservative shift. It also expanded ''Griswold''s right to privacy to strike down abortion laws ('' Roe v. Wade'')Regents of the University of California v. Bakke

''Regents of the University of California v. Bakke'', 438 U.S. 265 (1978) involved a dispute of whether preferential treatment for minorities can reduce educational opportunities for whites without violating the Constitution. The case was a la ...

'')[History of the Court, in Hall, Ely Jr., Grossman, and Wiecek (eds.) ''The Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States''. ]Oxford University Press

Oxford University Press (OUP) is the university press of the University of Oxford. It is the largest university press in the world, and its printing history dates back to the 1480s. Having been officially granted the legal right to print books ...

, 1992, Seminole Tribe v. Florida

''Seminole Tribe of Florida v. Florida'', 517 U.S. 44 (1996), was a Supreme Court of the United States, United States Supreme Court case which held that Article One of the U.S. Constitution did not give the United States Congress the power to abrog ...

'', ''City of Boerne v. Flores

''City of Boerne v. Flores'', 521 U.S. 507 (1997), was a landmark decision of the Supreme Court of the United States concerning the scope of Congress's power of enforcement under Section 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment. The case also had a signific ...

'').school vouchers

A school voucher, also called an education voucher in a voucher system, is a certificate of government funding for students at schools chosen by themselves or their parents. Funding is usually for a particular year, term, or semester. In some cou ...

(''Zelman v. Simmons-Harris

''Zelman v. Simmons-Harris'', 536 U.S. 639 (2002), was a 5–4 decision of the United States Supreme Court that upheld an Ohio program that used school vouchers. The Court decided that the program did not violate the Establishment Clause of the Fi ...

'') and reaffirmed ''Roe''s restrictions on abortion laws ('' Planned Parenthood v. Casey'').federal preemption

In the law of the United States, federal preemption is the invalidation of a U.S. state law that conflicts with federal law.

Constitutional basis

According to the Supremacy Clause (Article VI, clause 2) of the United States Constitution,

This ...

('' Wyeth v. Levine''), civil procedure

Civil procedure is the body of law that sets out the rules and standards that courts follow when adjudicating civil lawsuits (as opposed to procedures in criminal law matters). These rules govern how a lawsuit or case may be commenced; what kin ...

('' Twombly– Iqbal''), voting rights and federal preclearance ('' Shelby County– Brnovich''), abortion ('' Gonzales v. Carhart'' and '' Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization''),climate change

In common usage, climate change describes global warming—the ongoing increase in global average temperature—and its effects on Earth's climate system. Climate change in a broader sense also includes previous long-term changes to ...

('' Massachusetts v. EPA''), same-sex marriage

Same-sex marriage, also known as gay marriage, is the marriage of two people of the same sex or gender. marriage between same-sex couples is legally performed and recognized in 33 countries, with the most recent being Mexico, constituting ...

(''United States v. Windsor

''United States v. Windsor'', 570 U.S. 744 (2013), is a landmark United States Supreme Court civil rights case concerning same-sex marriage. The Court held that Section 3 of the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), which denied federal recognition o ...

'' and '' Obergefell v. Hodges''), and the Bill of Rights, such as in '' Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission'' and '' Americans for Prosperity Foundation v. Bonta'' ( First Amendment), '' Heller– McDonald– Bruen'' (Second Amendment

The second (symbol: s) is the unit of time in the International System of Units (SI), historically defined as of a day – this factor derived from the division of the day first into 24 hours, then to 60 minutes and finally to 60 seconds each ...

),

Composition

Nomination, confirmation, and appointment

Article II, Section 2, Clause 2 of the United States Constitution, known as the

Article II, Section 2, Clause 2 of the United States Constitution, known as the Appointments Clause

The Appointments Clause of Article II, Section 2, Clause 2, of the United States Constitution empowers the President of the United States to nominate and, with the advice and consent (confirmation) of the United States Senate, appoint public offi ...

, empowers the president to nominate and, with the confirmation ( advice and consent) of the United States Senate, to appoint public officials, including justices of the Supreme Court. This clause is one example of the system of checks and balances inherent in the Constitution. The president has the plenary power

A plenary power or plenary authority is a complete and absolute power to take action on a particular issue, with no limitations. It is derived from the Latin term ''plenus'' ("full").

United States

In United States constitutional law, plenary p ...

to nominate, while the Senate possesses the plenary power to reject or confirm the nominee. The Constitution sets no qualifications for service as a justice, thus a president may nominate anyone to serve, and the Senate may not set any qualifications or otherwise limit who the president can choose.Senate Judiciary Committee

The United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary, informally the Senate Judiciary Committee, is a standing committee of 22 U.S. senators whose role is to oversee the Department of Justice (DOJ), consider executive and judicial nominations ...

conducts hearings and votes on whether the nomination should go to the full Senate with a positive, negative or neutral report. The committee's practice of personally interviewing nominees is relatively recent. The first nominee to appear before the committee was Harlan Fiske Stone

Harlan is a given name and a surname which may refer to:

Surname

* Bob Harlan (born 1936 Robert E. Harlan), American football executive

*Bruce Harlan (1926–1959), American Olympic diver

*Byron B. Harlan (1886–1949), American politician

* Byron ...

in 1925, who sought to quell concerns about his links to Wall Street, and the modern practice of questioning began with John Marshall Harlan II

John Marshall Harlan (May 20, 1899 – December 29, 1971) was an American lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1955 to 1971. Harlan is usually called John Marshall Harlan II to distinguish him ...

in 1955. Once the committee reports out the nomination, the full Senate considers it. Rejections are relatively uncommon; the Senate has explicitly rejected twelve Supreme Court nominees, most recently Robert Bork

Robert Heron Bork (March 1, 1927 – December 19, 2012) was an American jurist who served as the solicitor general of the United States from 1973 to 1977. A professor at Yale Law School by occupation, he later served as a judge on the U.S. Cour ...

, nominated by President Ronald Reagan in 1987.

Although Senate rules do not necessarily allow a negative or tied vote in committee to block a nomination, prior to 2017 a nomination could be blocked by filibuster once debate had begun in the full Senate. President Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), often referred to by his initials LBJ, was an American politician who served as the 36th president of the United States from 1963 to 1969. He had previously served as the 37th vice ...

's nomination of sitting associate justice Abe Fortas

Abraham Fortas (June 19, 1910 – April 5, 1982) was an American lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1965 to 1969. Born and raised in Memphis, Tennessee, Fortas graduated from R ...

to succeed Earl Warren as Chief Justice in 1968 was the first successful filibuster of a Supreme Court nominee. It included both Republican and Democratic senators concerned with Fortas's ethics. President Donald Trump's nomination of Neil Gorsuch to the seat left vacant by Antonin Scalia's death was the second. Unlike the Fortas filibuster, only Democratic senators voted against cloture

Cloture (, also ), closure or, informally, a guillotine, is a motion or process in parliamentary procedure aimed at bringing debate to a quick end. The cloture procedure originated in the French National Assembly, from which the name is taken. ' ...

on the Gorsuch nomination, citing his perceived conservative judicial philosophy, and the Republican majority's prior refusal to take up President Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II ( ; born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who served as the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party, Obama was the first African-American president of the ...

's nomination of Merrick Garland to fill the vacancy. This led the Republican majority to change the rules and eliminate the filibuster for Supreme Court nominations.

Not every Supreme Court

Not every Supreme Court nominee

A candidate, or nominee, is the prospective recipient of an award or honor, or a person seeking or being considered for some kind of position; for example:

* to be elected to an office — in this case a candidate selection procedure occurs.

* t ...

has received a floor vote in the Senate. A president may withdraw a nomination before an actual confirmation vote occurs, typically because it is clear that the Senate will reject the nominee; this occurred with President George W. Bush's nomination of Harriet Miers in 2005. The Senate may also fail to act on a nomination, which expires at the end of the session. President Dwight Eisenhower's first nomination of John Marshall Harlan II

John Marshall Harlan (May 20, 1899 – December 29, 1971) was an American lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1955 to 1971. Harlan is usually called John Marshall Harlan II to distinguish him ...

in November 1954 was not acted on by the Senate; Eisenhower re-nominated Harlan in January 1955, and Harlan was confirmed two months later. Most recently, the Senate failed to act on the March 2016 nomination of Merrick Garland, as the nomination expired in January 2017, and the vacancy was filled by Neil Gorsuch, an appointee of President Trump.

Once the Senate confirms a nomination, the president must prepare and sign a commission, to which the Seal of the Department of Justice

A justice ministry, ministry of justice, or department of justice is a ministry or other government agency in charge of the administration of justice. The ministry or department is often headed by a minister of justice (minister for justice in a ...

must be affixed, before the appointee can take office. The seniority of an associate justice is based on the commissioning date, not the confirmation or swearing-in date. After receiving their commission, the appointee must then take the two prescribed oaths before assuming their official duties. The importance of the oath taking is underscored by the case of Edwin M. Stanton

Edwin McMasters Stanton (December 19, 1814December 24, 1869) was an American lawyer and politician who served as U.S. Secretary of War under the Lincoln Administration during most of the American Civil War. Stanton's management helped organize ...

. Although confirmed by the Senate on December 20, 1869, and duly commissioned as an associate justice by President Ulysses S. Grant, Stanton died on December 24, prior to taking the prescribed oaths. He is not, therefore, considered to have been a member of the court.

Before 1981, the approval process of justices was usually rapid. From the Truman through Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

administrations, justices were typically approved within one month. From the Reagan administration to the present, the process has taken much longer and some believe this is because Congress sees justices as playing a more political role than in the past. According to the Congressional Research Service

The Congressional Research Service (CRS) is a public policy research institute of the United States Congress. Operating within the Library of Congress, it works primarily and directly for members of Congress and their committees and staff on a ...

, the average number of days from nomination to final Senate vote since 1975 is 67 days (2.2 months), while the median is 71 days (2.3 months).

Recess appointments

When the Senate is in recess, a president may make temporary appointments to fill vacancies. Recess appointees hold office only until the end of the next Senate session (less than two years). The Senate must confirm the nominee for them to continue serving; of the two chief justices and eleven associate justices who have received recess appointments, only Chief Justice John Rutledge was not subsequently confirmed.

No U.S. president since Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; ; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American military officer and statesman who served as the 34th president of the United States from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, ...

has made a recess appointment to the court, and the practice has become rare and controversial even in lower federal courts. In 1960, after Eisenhower had made three such appointments, the Senate passed a "sense of the Senate" resolution that recess appointments to the court should only be made in "unusual circumstances";

Tenure

Article Three, Section 1 of the Constitution provides that justices "shall hold their offices during good behavior", which is understood to mean that they may serve for the remainder of their lives, until death; furthermore, the phrase is generally interpreted to mean that the only way justices can be removed from office is by Congress via the impeachment process. The Framers of the Constitution chose good behavior tenure to limit the power to remove justices and to ensure judicial independence. No constitutional mechanism exists for removing a justice who is permanently incapacitated by illness or injury, but unable (or unwilling) to resign.

Article Three, Section 1 of the Constitution provides that justices "shall hold their offices during good behavior", which is understood to mean that they may serve for the remainder of their lives, until death; furthermore, the phrase is generally interpreted to mean that the only way justices can be removed from office is by Congress via the impeachment process. The Framers of the Constitution chose good behavior tenure to limit the power to remove justices and to ensure judicial independence. No constitutional mechanism exists for removing a justice who is permanently incapacitated by illness or injury, but unable (or unwilling) to resign.Samuel Chase

Samuel Chase (April 17, 1741 – June 19, 1811) was a Founding Father of the United States, a signatory to the Continental Association and United States Declaration of Independence as a representative of Maryland, and an Associate Justice of t ...

, in 1804. The House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entitles. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often c ...

adopted eight articles of impeachment against him; however, he was acquitted by the Senate, and remained in office until his death in 1811. No subsequent effort to impeach a sitting justice has progressed beyond referral to the Judiciary Committee. (For example, William O. Douglas

William Orville Douglas (October 16, 1898January 19, 1980) was an American jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, who was known for his strong progressive and civil libertarian views, and is often ci ...

was the subject of hearings twice, in 1953 and again in 1970; and Abe Fortas

Abraham Fortas (June 19, 1910 – April 5, 1982) was an American lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1965 to 1969. Born and raised in Memphis, Tennessee, Fortas graduated from R ...

resigned while hearings were being organized in 1969.)

Because justices have indefinite tenure, timing of vacancies can be unpredictable. Sometimes they arise in quick succession, as in September 1971, when Hugo Black and John Marshall Harlan II

John Marshall Harlan (May 20, 1899 – December 29, 1971) was an American lawyer and jurist who served as an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1955 to 1971. Harlan is usually called John Marshall Harlan II to distinguish him ...

left within days of each other, the shortest period of time between vacancies in the court's history. Sometimes a great length of time passes between vacancies, such as the 11-year span, from 1994 to 2005, from the retirement of Harry Blackmun to the death of William Rehnquist

William Hubbs Rehnquist ( ; October 1, 1924 – September 3, 2005) was an American attorney and jurist who served on the U.S. Supreme Court for 33 years, first as an associate justice from 1972 to 1986 and then as the 16th chief justice from ...

, which was the second longest timespan between vacancies in the court's history. On average a new justice joins the Court about every two years.

Despite the variability, all but four presidents have been able to appoint at least one justice. William Henry Harrison died a month after taking office, although his successor (John Tyler

John Tyler (March 29, 1790 – January 18, 1862) was the tenth president of the United States, serving from 1841 to 1845, after briefly holding office as the tenth vice president in 1841. He was elected vice president on the 1840 Whig tick ...

) made an appointment during that presidential term. Likewise, Zachary Taylor died 16 months after taking office, but his successor ( Millard Fillmore) also made a Supreme Court nomination before the end of that term. Andrew Johnson, who became president after the assassination of Abraham Lincoln, was denied the opportunity to appoint a justice by a reduction in the size of the court. Jimmy Carter is the only person elected president to have left office after at least one full term without having the opportunity to appoint a justice. Presidents James Monroe

James Monroe ( ; April 28, 1758July 4, 1831) was an American statesman, lawyer, diplomat, and Founding Father who served as the fifth president of the United States from 1817 to 1825. A member of the Democratic-Republican Party, Monroe was ...

, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and George W. Bush each served a full term without an opportunity to appoint a justice, but made appointments during their subsequent terms in office. No president who has served more than one full term has gone without at least one opportunity to make an appointment.

Size of the court

The U.S. Supreme Court currently consists of nine members: one chief justice and eight associate justices. The U.S. Constitution does not specify the size of the Supreme Court, nor does it specify any specific positions for the Court's members. However, the Constitution assumes the existence of the office of the chief justice, because it mentions in Article I, Section 3, Clause 6 that "the Chief Justice" must preside over impeachment trials of the President of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States ...

. The power to define the Supreme Court's size and membership has been assumed to belong to Congress, which initially established a six-member Supreme Court composed of a chief justice and five associate justices through the Judiciary Act of 1789. The size of the court was first altered by the Midnight Judges Act

The Midnight Judges Act (also known as the Judiciary Act of 1801; , and officially An act to provide for the more convenient organization of the Courts of the United States) represented an effort to solve an issue in the U.S. Supreme Court during ...

of 1801 which would have reduced the size of the court to five members upon its next vacancy, but the Judiciary Act of 1802 The Judiciary Act of 1802 () was a Federal statute, enacted on April 29, 1802, to reorganize the federal court system. It restored some elements of the Judiciary Act of 1801, which had been adopted by the Federalist majority in the previous Congre ...

promptly negated the 1801 act, restoring the court's size to six members before any such vacancy occurred. As the nation's boundaries grew across the continent and as Supreme Court justices in those days had to ride the circuit, an arduous process requiring long travel on horseback or carriage over harsh terrain that resulted in months-long extended stays away from home, Congress added justices to correspond with the growth: seven in 1807, nine in 1837, and ten in 1863.

At the behest of Chief Justice Chase and in an attempt by the Republican Congress to limit the power of Democrat Andrew Johnson, Congress passed the Judicial Circuits Act

The Judicial Circuits Act of 1866 (ch. 210, ) reorganized the United States circuit courts and provided for the gradual elimination of several seats on the Supreme Court of the United States. It was signed into law on July 23, 1866, by President ...

of 1866, providing that the next three justices to retire would not be replaced, which would thin the bench to seven justices by attrition. Consequently, one seat was removed in 1866 and a second in 1867. Soon after Johnson left office, the new president Ulysses S. Grant, a Republican, signed into law the Judiciary Act of 1869 The Judiciary Act of 1869 (41st Congress, Sess. 1, ch. 22, , enacted April 10, 1869), formally An Act to amend the Judicial System of the United States and sometimes called the Circuit Judges Act of 1869, provided that the Supreme Court of the Unite ...

. This returned the number of justices to nine (where it has since remained), and allowed Grant to immediately appoint two more judges.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

attempted to expand the court in 1937. His proposal envisioned the appointment of one additional justice for each incumbent justice who reached the age of 70years 6months and refused retirement, up to a maximum bench of 15 justices. The proposal was ostensibly to ease the burden of the docket

Docket may refer to:

* Docket (court), the official schedule of proceedings in lawsuits pending in a court of law.

*Agenda (meeting) or docket, a list of meeting activities in the order in which they are to be taken up

*Receipt

A receipt (a ...

on elderly judges, but the actual purpose was widely understood as an effort to "pack" the court with justices who would support Roosevelt's New Deal. The plan, usually called the " court-packing plan", failed in Congress after members of Roosevelt's own Democratic Party believed it to be unconstitutional. It was defeated 70–20 in the Senate, and the Senate Judiciary Committee

The United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary, informally the Senate Judiciary Committee, is a standing committee of 22 U.S. senators whose role is to oversee the Department of Justice (DOJ), consider executive and judicial nominations ...

reported that it was "essential to the continuance of our constitutional democracy" that the proposal "be so emphatically rejected that its parallel will never again be presented to the free representatives of the free people of America.”

The rise and solidification of a conservative majority on the court during the presidency of Donald Trump

Donald Trump's tenure as the 45th president of the United States began with his inauguration on January 20, 2017, and ended on January 20, 2021. Trump, a Republican from New York City, took office following his Electoral College victory ...

sparked a liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

response in the form of calls for court-packing. Democrats in the House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entitles. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often c ...

introduced a bill in April 2021 to expand the Supreme Court from nine to 13 seats, but Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi refused to bring it to the floor and relatively few Democrats backed it. Shortly after taking office in January 2021, Joe Biden established a presidential commission to study possible reforms to the Supreme Court. The commission's December 2021 final report discusses but takes no position on expanding the size of the court. Whether it would be constitutional to expand the size of the Supreme Court in ways understood to be designed to "pack" it with justices that would rule more favorably on a president's agenda or to simply change the ideological composition of the court remains unclear.

Membership

Current justices

There are currently nine justices on the Supreme Court: Chief Justice John Roberts

John Glover Roberts Jr. (born January 27, 1955) is an American lawyer and jurist who has served as the 17th chief justice of the United States since 2005. Roberts has authored the majority opinion in several landmark cases, including '' Nat ...

and eight associate justices. Among the current members of the court, Clarence Thomas is the longest-serving justice, with a tenure of days () as of ; the most recent justice to join the court is Ketanji Brown Jackson, whose tenure began on June 30, 2022.

Length of tenure

This graphical timeline depicts the length of each current Supreme Court justice's tenure (not seniority, as the chief justice has seniority over all associate justices regardless of tenure) on the court:

Court demographics

The court currently has five male and four female justices. Among the nine justices, there are two African American justices (Justices Thomas and Jackson

Jackson may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Jackson (name), including a list of people and fictional characters with the surname or given name

Places

Australia

* Jackson, Queensland, a town in the Maranoa Region

* Jackson North, Qu ...

) and one Hispanic justice (Justice Sotomayor Sotomayor is a Galician surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* Sonia Sotomayor, U.S. Supreme Court justice

In arts and entertainment

* Carlos Sotomayor (1911–1988), Chilean painter

* Chris Sotomayor, artist who works as a colorist ...

). One of the justices was born to at least one immigrant parent: Justice Alito's father was born in Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

.

At least six justices are Roman Catholics, one is Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

, and one is Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to b ...

. It is unclear whether Neil Gorsuch considers himself a Catholic or an Episcopalian.[Neil Gorsuch was raised Catholic, but attends an Episcopalian church. It is unclear if he considers himself a Catholic or a Protestant. ] Historically, most justices have been Protestants, including 36 Episcopalians, 19 Presbyterians, 10 Unitarians, 5 Methodists, and 3 Baptists. The first Catholic justice was Roger Taney in 1836, and 1916 saw the appointment of the first Jewish justice, Louis Brandeis.John Roberts

John Glover Roberts Jr. (born January 27, 1955) is an American lawyer and jurist who has served as the 17th chief justice of the United States since 2005. Roberts has authored the majority opinion in several landmark cases, including '' Nat ...

from Harvard; plus Samuel Alito, Brett Kavanaugh

Brett Michael Kavanaugh ( ; born February 12, 1965) is an American lawyer and jurist serving as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. He was nominated by President Donald Trump on July 9, 2018, and has served since ...

, Sonia Sotomayor and Clarence Thomas from Yale

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the wor ...

. Only Amy Coney Barrett

Amy Vivian Coney Barrett (born January 28, 1972) is an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. The fifth woman to serve on the court, she was nominated by President Donald Trump and has served since October 27, 2020. ...

did not; she received her law degree at Notre Dame.

Previous positions or offices, judicial or federal government, held by the current justices prior to joining the Court include:

For much of the court's history, every justice was a man of Northwestern European descent, and almost always

For much of the court's history, every justice was a man of Northwestern European descent, and almost always Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to b ...

. Diversity concerns focused on geography, to represent all regions

In geography, regions, otherwise referred to as zones, lands or territories, are areas that are broadly divided by physical characteristics (physical geography), human impact characteristics (human geography), and the interaction of humanity and t ...

of the country, rather than religious, ethnic, or gender diversity.African-American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ensl ...

justice in 1967.Italian-American

Italian Americans ( it, italoamericani or ''italo-americani'', ) are Americans who have full or partial Italian ancestry. The largest concentrations of Italian Americans are in the urban Northeast and industrial Midwestern metropolitan areas, ...

justice. Marshall was succeeded by African-American Clarence Thomas in 1991. O'Connor was joined by Ruth Bader Ginsburg, the first Jewish woman on the Court, in 1993.Sonia Sotomayor

Sonia Maria Sotomayor (, ; born June 25, 1954) is an American lawyer and jurist who serves as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. She was nominated by President Barack Obama on May 26, 2009, and has served since ...

, the first Hispanic and Latina

Latina or Latinas most often refers to:

* Latinas, a demographic group in the United States

* Latino (demonym), a term used in the United States for people with cultural ties to Latin America.

*Latin Americans

Latina and Latinas may also refer ...

justice,Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a Anglo-Scottish border, border with England to the southeast ...

; James Iredell (1790–1799), born in Lewes, England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

; William Paterson (1793–1806), born in County Antrim, Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

; David Brewer (1889–1910), born to American missionaries in Smyrna, Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

(now Izmir, Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with a small portion on the Balkan Peninsula in ...

); George Sutherland

George Alexander Sutherland (March 25, 1862July 18, 1942) was an English-born American jurist and politician. He served as an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court between 1922 and 1938. As a member of the Republican Party, he also repre ...

(1922–1939), born in Buckinghamshire, England; and Felix Frankfurter

Felix Frankfurter (November 15, 1882 – February 22, 1965) was an Austrian-American jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1939 until 1962, during which period he was a noted advocate of judic ...

(1939–1962), born in Vienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

, Austria-Hungary (now in Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

).

Retired justices

There are currently four living retired justices of the Supreme Court of the United States: Sandra Day O'Connor, Anthony Kennedy, David Souter, and Stephen Breyer. As retired justices, they no longer participate in the work of the Supreme Court, but may be designated for temporary assignments to sit on lower federal courts, usually the United States Courts of Appeals. Such assignments are formally made by the chief justice, on request of the chief judge of the lower court and with the consent of the retired justice. In recent years, Justice Souter has frequently sat on the First Circuit, the court of which he was briefly a member before joining the Supreme Court; and Justice O'Connor often sat with several Courts of Appeal before withdrawing from public life in 2018. The status of a retired justice is analogous to that of a circuit or district court judge who has taken senior status

Senior status is a form of semi- retirement for United States federal judges. To qualify, a judge in the federal court system must be at least 65 years old, and the sum of the judge's age and years of service as a federal judge must be at leas ...

, and eligibility of a Supreme Court justice to assume retired status (rather than simply resign from the bench) is governed by the same age and service criteria.

In recent times, justices tend to strategically plan their decisions to leave the bench with personal, institutional, ideological, partisan and sometimes even political factors playing a role. The fear of mental decline and death often motivates justices to step down. The desire to maximize the court's strength and legitimacy through one retirement at a time, when the court is in recess and during non-presidential election years suggests a concern for institutional health. Finally, especially in recent decades, many justices have timed their departure to coincide with a philosophically compatible president holding office, to ensure that a like-minded successor would be appointed.

Seniority and seating

For the most part, the day-to-day activities of the justices are governed by rules of protocol based upon the

For the most part, the day-to-day activities of the justices are governed by rules of protocol based upon the seniority

Seniority is the state of being older or placed in a higher position of status relative to another individual, group, or organization. For example, one employee may be senior to another either by role or rank (such as a CEO vice a manager), or by ...

of justices. The chief justice always ranks first in the order of precedence—regardless of the length of their service. The associate justices are then ranked by the length of their service. The chief justice sits in the center on the bench, or at the head of the table during conferences. The other justices are seated in order of seniority. The senior-most associate justice sits immediately to the chief justice's right; the second most senior sits immediately to their left. The seats alternate right to left in order of seniority, with the most junior justice occupying the last seat. Therefore, starting with the October 2022 term, the court will sit as follows from left to right, from the perspective of those facing the court: Barrett, Gorsuch, Sotomayor, Thomas (most senior associate justice), Roberts (chief justice), Alito, Kagan, Kavanaugh, and Jackson. Likewise, when the members of the court gather for official group photographs, justices are arranged in order of seniority, with the five most senior members seated in the front row in the same order as they would sit during Court sessions, and the four most junior justices standing behind them, again in the same order as they would sit during Court sessions.

In the justices' private conferences, current practice is for them to speak and vote in order of seniority, beginning with the chief justice first and ending with the most junior associate justice. By custom, the most junior associate justice in these conferences is charged with any menial tasks the justices may require as they convene alone, such as answering the door of their conference room, serving beverages and transmitting orders of the court to the clerk. Justice Joseph Story

Joseph Story (September 18, 1779 – September 10, 1845) was an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, serving from 1812 to 1845. He is most remembered for his opinions in ''Martin v. Hunter's Lessee'' and '' United States ...

served the longest as junior justice, from February 3, 1812, to September 1, 1823, for a total of 4,228 days. Justice Stephen Breyer follows very closely behind serving from August 3, 1994, to January 31, 2006, for a total of 4,199 days.

Salary

As of 2021, associate justices receive a yearly salary of $268,300 and the chief justice is paid $280,500 per year.

Judicial leanings

Although justices are nominated by the president in power, and receive confirmation by the Senate, justices do not represent or receive official endorsements from political parties, as is accepted practice in the legislative and executive branches. Jurists are informally categorized in legal and political circles as being judicial conservatives, moderates, or liberals. Such leanings generally refer to legal outlook rather than a political or legislative one. The nominations of justices are endorsed by individual politicians in the legislative branch who vote their approval or disapproval of the nominated justice. The ideologies of jurists can be measured and compared with several metrics, including the Segal–Cover score A Segal–Cover score is an attempt to measure the "perceived qualifications and ideology" of nominees to the United States Supreme Court. The scores are created by analyzing pre-confirmation newspaper editorials regarding the nominations from ''The ...

, Martin-Quinn score, and Judicial Common Space

The Judicial Common Space (JCS) is a strategy to compare the ideologies of American judges. It was developed to compare the viewpoints of judges in the US Supreme Court and the Court of Appeals. It is one of the most commonly used measures of judic ...

score.

Following the confirmation of Ketanji Brown Jackson in 2022, the court consists of six justices appointed by Republican presidents and three appointed by Democratic presidents. It is popularly accepted that Chief Justice Roberts and associate justices Thomas, Alito, Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, and Barrett, appointed by Republican presidents, compose the court's conservative wing, and that Justices Sotomayor and Kagan, appointed by Democratic presidents, compose the court's liberal wing; Justice Jackson is expected to join them. Gorsuch had a track record as a reliably conservative judge in the 10th circuit. Kavanaugh was considered one of the most conservative judges in the DC Circuit prior to his appointment to the Supreme Court. Likewise, Barrett's brief track record on the Seventh Circuit is conservative.

Prior to Justice Ginsburg's death, Chief Justice Roberts was considered the court's median justice (in the middle of the ideological spectrum, with four justices more liberal and four more conservative than him), making him the ideological center of the court. Since Ginsburg's death and Barrett's confirmation, Kavanaugh is the court's median justice, based on the criterion that he has been in the majority more than any other justice.Tom Goldstein

Thomas Che Goldstein (born 1970) is an American lawyer known for his advocacy before and blogging about the Supreme Court of the United States. He was a founding partner of Goldstein and Howe (now Goldstein & Russell), a Washington, D.C., firm s ...

argued in an article in ''SCOTUSblog

''SCOTUSblog'' is a law blog written by lawyers, law professors, and law students about the Supreme Court of the United States (sometimes abbreviated "SCOTUS"). Formerly sponsored by Bloomberg Law, the site tracks cases before the Court from th ...

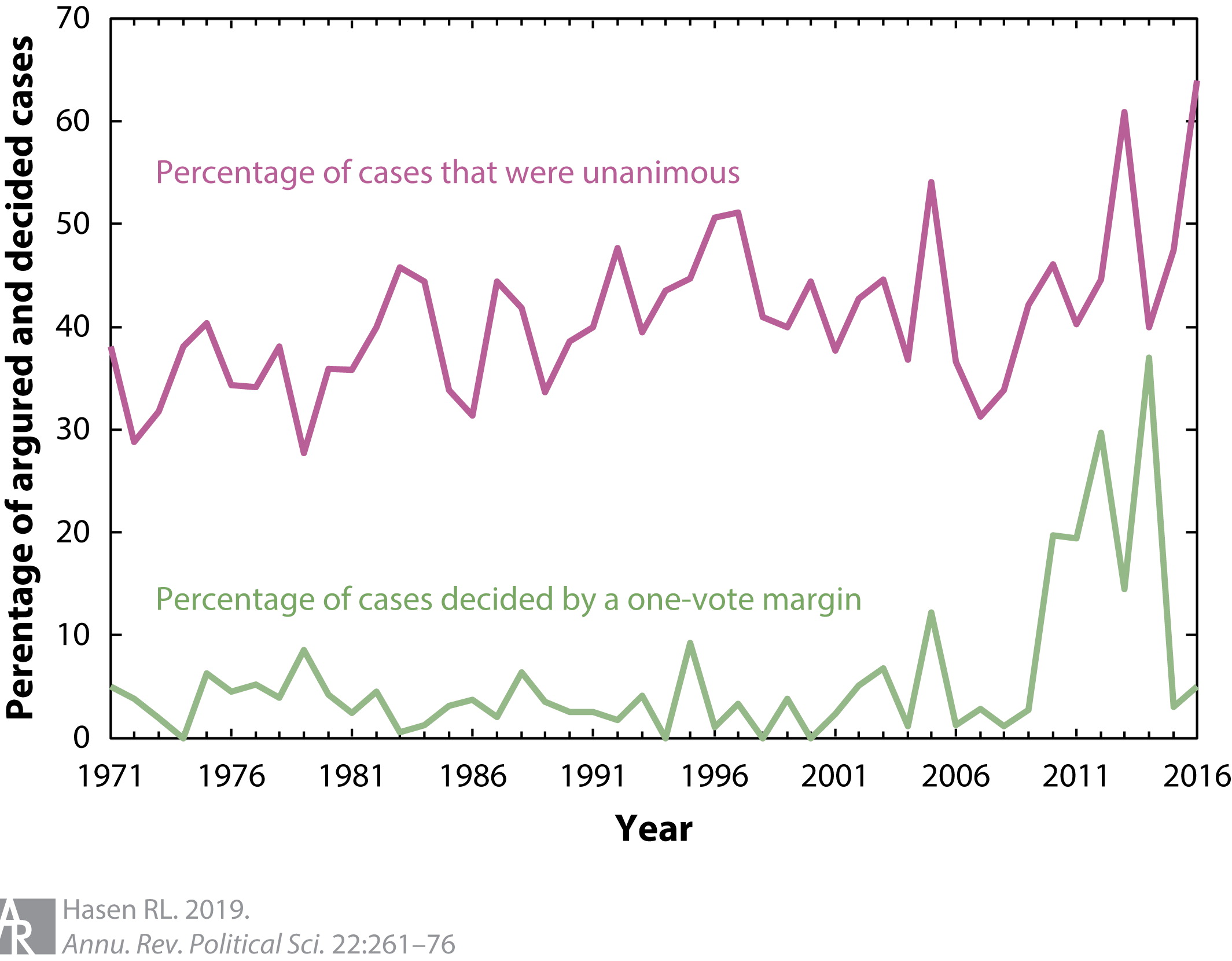

'' in 2010, that the popular view of the Supreme Court as sharply divided along ideological lines and each side pushing an agenda at every turn is "in significant part a caricature designed to fit certain preconceptions." According to statistics compiled by ''SCOTUSblog'', in the twelve terms from 2000 to 2011, an average of 19 of the opinions on major issues (22%) were decided by a 5–4 vote, with an average of 70% of those split opinions decided by a court divided along the traditionally perceived ideological lines (about 15% of all opinions issued). Over that period, the conservative bloc has been in the majority about 62% of the time that the court has divided along ideological lines, which represents about 44% of all the 5–4 decisions.

According to statistics compiled by ''SCOTUSblog'', in the twelve terms from 2000 to 2011, an average of 19 of the opinions on major issues (22%) were decided by a 5–4 vote, with an average of 70% of those split opinions decided by a court divided along the traditionally perceived ideological lines (about 15% of all opinions issued). Over that period, the conservative bloc has been in the majority about 62% of the time that the court has divided along ideological lines, which represents about 44% of all the 5–4 decisions.recused

Judicial disqualification, also referred to as recusal, is the act of abstaining from participation in an official action such as a legal proceeding due to a conflict of interest of the presiding court official or administrative officer. Appli ...

herself from 26 of the cases due to her prior role as United States Solicitor General

The solicitor general of the United States is the fourth-highest-ranking official in the United States Department of Justice. Elizabeth Prelogar has been serving in the role since October 28, 2021.

The United States solicitor general represent ...

. Of the 80 cases, 38 (about 48%, the highest percentage since the October 2005 term) were decided unanimously (9–0 or 8–0), and 16 decisions were made by a 5–4 vote (about 20%, compared to 18% in the October 2009 term, and 29% in the October 2008 term). However, in fourteen of the sixteen 5–4 decisions, the court divided along the traditional ideological lines (with Ginsburg, Breyer, Sotomayor, and Kagan on the liberal side, and Roberts, Scalia, Thomas, and Alito on the conservative, and Kennedy providing the "swing vote"). This represents 87% of those 16 cases, the highest rate in the past 10 years. The conservative bloc, joined by Kennedy, formed the majority in 63% of the 5–4 decisions, the highest cohesion rate of that bloc in the Roberts Court

The Roberts Court is the time since 2005 during which the Supreme Court of the United States has been led by John Roberts as Chief Justice. It is generally considered to be more conservative than the preceding Rehnquist Court and the most cons ...

.[

The October 2017 term had a low rate of unanimous rulings, with only 39% of the cases decided by unanimous rulings, the lowest percentage since the October 2008 term when 30% of rulings were unanimous.][

The October 2018 term, which saw the replacement of Anthony Kennedy by Brett Kavanaugh, once again saw a low rate of unanimity: only 28 of 71 decided cases were decided by a unanimous court, about 39% of the cases.][ The highest agreement between justices was between Roberts and Kavanaugh, who agreed at least in judgement 94% of the time; the second highest agreement was again between Ginsburg and Sotomayor, who agreed 93% of the time. The highest rate of full agreement was between Ginsburg and Kagan (82% of the time), closely followed by Roberts and Alito, Ginsburg and Sotomayor, and Breyer and Kagan (81% of the time). The largest rate of disagreement was between Thomas and both Ginsburg and Sotomayor; Thomas disagreed with each of them 50% of the time.][

By the completion of the 2021 term, the percent of 6–3 decisions favoring the conservative majority had reached 30%, with the percent of unanimous cases having dropped to the same number.

]

Facilities

The Supreme Court first met on February 1, 1790, at the Merchants' Exchange Building in New York City. When Philadelphia became the capital, the court met briefly in Independence Hall before settling in Old City Hall from 1791 until 1800. After the government moved to Washington, D.C., the court occupied various spaces in the Capitol building until 1935, when it moved into its own purpose-built home. The four-story building was designed by

The Supreme Court first met on February 1, 1790, at the Merchants' Exchange Building in New York City. When Philadelphia became the capital, the court met briefly in Independence Hall before settling in Old City Hall from 1791 until 1800. After the government moved to Washington, D.C., the court occupied various spaces in the Capitol building until 1935, when it moved into its own purpose-built home. The four-story building was designed by Cass Gilbert

Cass Gilbert (November 24, 1859 – May 17, 1934) was an American architect. An early proponent of skyscrapers, his works include the Woolworth Building, the United States Supreme Court building, the state capitols of Minnesota, Arkansas and ...

in a classical style sympathetic to the surrounding buildings of the Capitol and Library of Congress

The Library of Congress (LOC) is the research library that officially serves the United States Congress and is the ''de facto'' national library of the United States. It is the oldest federal cultural institution in the country. The library ...

, and is clad in marble. The building includes the courtroom, justices' chambers, an extensive law library

A law library is a special library used by law students, lawyers, judges and their law clerks, historians and other scholars of legal history in order to research the law. Law libraries are also used by people who draft or advocate for new la ...

, various meeting spaces, and auxiliary services including a gymnasium. The Supreme Court building is within the ambit of the Architect of the Capitol

The Architect of the Capitol (AOC) is the federal agency responsible for the maintenance, operation, development, and preservation of the United States Capitol Complex. It is an agency of the legislative branch of the federal government and is ...

, but maintains its own Supreme Court Police, separate from the Capitol Police.[

Located across First Street from the United States Capitol at One First Street NE and Maryland Avenue,][ When the court is not in session, lectures about the courtroom are held hourly from 9:30am to 3:30pm and reservations are not necessary.][ When the court is in session the public may attend oral arguments, which are held twice each morning (and sometimes afternoons) on Mondays, Tuesdays, and Wednesdays in two-week intervals from October through late April, with breaks during December and February. Visitors are seated on a first-come first-served basis. One estimate is there are about 250 seats available.][

]

Jurisdiction

Congress is authorized by Article III of the federal Constitution to regulate the Supreme Court's appellate jurisdiction. The Supreme Court has original and exclusive jurisdiction over cases between two or more states but may decline to hear such cases. It also possesses original but not exclusive jurisdiction to hear "all actions or proceedings to which ambassadors, other public ministers, consuls, or vice consuls of foreign states are parties; all controversies between the United States and a State; and all actions or proceedings by a State against the citizens of another State or against aliens."

In 1906, the court asserted its original jurisdiction to prosecute individuals for contempt of court in '' United States v. Shipp''. The resulting proceeding remains the only contempt proceeding and only criminal trial in the court's history.John Marshall Harlan

John Marshall Harlan (June 1, 1833 – October 14, 1911) was an American lawyer and politician who served as an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1877 until his death in 1911. He is often called "The Great Dissenter" due to his ...

granted Johnson a stay of execution to allow his lawyers to file an appeal. Johnson was removed from his jail cell by a lynch mob, aided by the local sheriff who left the prison virtually unguarded, and hanged from a bridge, after which a deputy sheriff pinned a note on Johnson's body reading: "To Justice Harlan. Come get your nigger now."special master

In the law of the United States, a special master is generally a subordinate official appointed by a judge to ensure judicial orders are followed, or in the alternative, to hear evidence on behalf of the judge and make recommendations to the jud ...

to preside over the trial in Chattanooga with closing arguments made in Washington before the Supreme Court justices, who found nine individuals guilty of contempt, sentencing three to 90 days in jail and the rest to 60 days in jail.Supreme Court of Puerto Rico

The Supreme Court of Puerto Rico ( es, Tribunal Supremo de Puerto Rico) is the highest court of Puerto Rico, having judicial authority to interpret and decide questions of Puerto Rican law. The Court is analogous to one of the state supreme c ...

(through ''certiorari''), the Supreme Court of the Virgin Islands (through ''certiorari''), the District of Columbia Court of Appeals (through ''certiorari''),per curiam decision

In law, a ''per curiam'' decision (or opinion) is a ruling issued by an appellate court of multiple judges in which the decision rendered is made by the court (or at least, a majority of the court) acting collectively (and typically, though no ...

simply affirming the lower court's decision without discussing the merits of the case, since the Supreme Court of Florida lacks jurisdiction to hear appeals of such decisions. The power of the Supreme Court to consider appeals from state courts, rather than just federal courts, was created by the Judiciary Act of 1789 and upheld early in the court's history, by its rulings in '' Martin v. Hunter's Lessee'' (1816) and ''Cohens v. Virginia

''Cohens v. Virginia'', 19 U.S. (6 Wheat.) 264 (1821), is a landmark case by the Supreme Court of the United States that is most notable for the Court's assertion of its power to review state supreme court decisions in criminal law matters if def ...

'' (1821). The Supreme Court is the only federal court that has jurisdiction over direct appeals from state court decisions, although there are several devices that permit so-called "collateral review" of state cases. It has to be noted that this "collateral review" often only applies to individuals on death row and not through the regular judicial system.

Since Article Three of the United States Constitution stipulates that federal courts may only entertain "cases" or "controversies", the Supreme Court cannot decide cases that are moot and it does not render advisory opinions, as the supreme courts of some states may do. For example, in '' DeFunis v. Odegaard'', , the court dismissed a lawsuit challenging the constitutionality of a law school affirmative action policy because the plaintiff student had graduated since he began the lawsuit, and a decision from the court on his claim would not be able to redress any injury he had suffered. However, the court recognizes some circumstances where it is appropriate to hear a case that is seemingly moot. If an issue is "capable of repetition yet evading review", the court would address it even though the party before the court would not themselves be made whole by a favorable result. In ''Roe v. Wade'', , and other abortion cases, the court addresses the merits of claims pressed by pregnant women seeking abortions even if they are no longer pregnant because it takes longer than the typical human gestation period to appeal a case through the lower courts to the Supreme Court. Another mootness exception is voluntary cessation of unlawful conduct, in which the court considers the probability of recurrence and plaintiff's need for relief.

Justices as circuit justices

The United States is divided into thirteen circuit courts of appeals, each of which is assigned a "circuit justice" from the Supreme Court. Although this concept has been in continuous existence throughout the history of the republic, its meaning has changed through time. Under the Judiciary Act of 1789, each justice was required to "ride circuit", or to travel within the assigned circuit and consider cases alongside local judges. This practice encountered opposition from many justices, who cited the difficulty of travel. Moreover, there was a potential for a conflict of interest on the court if a justice had previously decided the same case while riding circuit. Circuit riding ended in 1901, when the Circuit Court of Appeals Act was passed, and circuit riding was officially abolished by Congress in 1911.

The circuit justice for each circuit is responsible for dealing with certain types of applications that, under the court's rules, may be addressed by a single justice. These include applications for emergency stays (including stays of execution in death-penalty cases) and injunctions pursuant to the All Writs Act arising from cases within that circuit, and routine requests such as requests for extensions of time. In the past, circuit justices also sometimes ruled on motions for bail

Bail is a set of pre-trial restrictions that are imposed on a suspect to ensure that they will not hamper the judicial process. Bail is the conditional release of a defendant with the promise to appear in court when required.

In some countrie ...

in criminal cases, writs of '' habeas corpus'', and applications for writs of error granting permission to appeal.

A circuit justice may sit as a judge on the Court of Appeals of that circuit, but over the past hundred years, this has rarely occurred. A circuit justice sitting with the Court of Appeals has seniority over the chief judge of the circuit. The chief justice has traditionally been assigned to the District of Columbia Circuit, the Fourth Circuit (which includes Maryland and Virginia, the states surrounding the District of Columbia), and since it was established, the Federal Circuit. Each associate justice is assigned to one or two judicial circuits.

As of September 28, 2022, the allotment of the justices among the circuits is as follows:

Five of the current justices are assigned to circuits on which they previously sat as circuit judges: Chief Justice Roberts (D.C. Circuit), Justice Sotomayor (Second Circuit), Justice Alito (Third Circuit), Justice Barrett (Seventh Circuit), and Justice Gorsuch (Tenth Circuit).

Process

Term

A term of the Supreme Court commences on the first Monday of each October, and continues until June or early July of the following year. Each term consists of alternating periods of around two weeks known as "sittings" and "recesses"; justices hear cases and deliver rulings during sittings, and discuss cases and write opinions during recesses.

Case selection

Nearly all cases come before the court by way of petitions for writs of '' certiorari'', commonly referred to as ''cert''; the court may review any case in the federal courts of appeals "by writ of ''certiorari'' granted upon the petition of any party to any civil or criminal case." The court may only review "final judgments rendered by the highest court of a state in which a decision could be had" if those judgments involve a question of federal statutory or constitutional law. The party that appealed to the court is the ''petitioner {{Unreferenced, date=December 2009

A petitioner is a person who pleads with governmental institution for a legal remedy or a redress of grievances, through use of a petition.

In the courts

The petitioner may seek a legal remedy if the state or ano ...

'' and the non-mover is the '' respondent''. All case names before the court are styled ''petitioner'' v. ''respondent'', regardless of which party initiated the lawsuit in the trial court. For example, criminal prosecutions are brought in the name of the state and against an individual, as in ''State of Arizona v. Ernesto Miranda''. If the defendant is convicted, and his conviction then is affirmed on appeal in the state supreme court

In the United States, a state supreme court (known by other names in some states) is the highest court in the state judiciary of a U.S. state. On matters of state law, the judgment of a state supreme court is considered final and binding in b ...

, when he petitions for cert the name of the case becomes ''Miranda v. Arizona''.

There are situations where the Court has original jurisdiction, such as when two states have a dispute against each other, or when there is a dispute between the United States and a state. In such instances, a case is filed with the Supreme Court directly. Examples of such cases include ''United States v. Texas'', a case to determine whether a parcel of land belonged to the United States or to Texas, and '' Virginia v. Tennessee'', a case turning on whether an incorrectly drawn boundary between two states can be changed by a state court, and whether the setting of the correct boundary requires Congressional approval. Although it has not happened since 1794 in the case of '' Georgia v. Brailsford'', parties in an action at law in which the Supreme Court has original jurisdiction may request that a jury determine issues of fact. ''Georgia v. Brailsford'' remains the only case in which the court has empaneled a jury, in this case a special jury A special jury, which is a jury selected from a special roll of persons with a restrictive qualification, could be used for civil or criminal cases, although in criminal cases only for misdemeanours such as seditious libel. The party opting for a sp ...

.New Jersey v. Delaware

''New Jersey v. Delaware'', 552 U.S. 597 (2008), is a United States Supreme Court case in which New Jersey sued Delaware, invoking the Supreme Court's original jurisdiction under (a), following Delaware's denial of oil company BP's petition to ...

'', and water rights between riparian