Sunderland, Tyne and Wear on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sunderland () is a port city in

Recorded settlements at the mouth of the Wear date to 674, when an

Recorded settlements at the mouth of the Wear date to 674, when an

By the start of the 18th century the banks of the Wear were described as being studded with small shipyards, as far as the tide flowed. After 1717, measures having been taken to increase the depth of the river, Sunderland's shipbuilding trade grew substantially (in parallel with its coal exports). A number of warships were built, alongside many commercial sailing ships. By the middle of the century the town was probably the premier shipbuilding centre in Britain. By 1788 Sunderland was Britain's fourth largest port (by measure of tonnage) after London, Newcastle and Liverpool; among these it was the leading coal exporter (though it did not rival Newcastle in terms of home coal trade). Still further growth was driven across the region, towards the end of the century, by London's insatiable demand for coal during the

By the start of the 18th century the banks of the Wear were described as being studded with small shipyards, as far as the tide flowed. After 1717, measures having been taken to increase the depth of the river, Sunderland's shipbuilding trade grew substantially (in parallel with its coal exports). A number of warships were built, alongside many commercial sailing ships. By the middle of the century the town was probably the premier shipbuilding centre in Britain. By 1788 Sunderland was Britain's fourth largest port (by measure of tonnage) after London, Newcastle and Liverpool; among these it was the leading coal exporter (though it did not rival Newcastle in terms of home coal trade). Still further growth was driven across the region, towards the end of the century, by London's insatiable demand for coal during the  In 1719, the parish of Sunderland was carved from the densely populated east end of Bishopwearmouth by the establishment of a new parish church,

In 1719, the parish of Sunderland was carved from the densely populated east end of Bishopwearmouth by the establishment of a new parish church,  By 1770 Sunderland had spread westwards along its High Street to join up with Bishopwearmouth. In 1796 Bishopwearmouth in turn gained a physical link with Monkwearmouth following the construction of a bridge, the Wearmouth Bridge, which was the world's second iron bridge (after the famous span at Ironbridge). It was built at the instigation of

By 1770 Sunderland had spread westwards along its High Street to join up with Bishopwearmouth. In 1796 Bishopwearmouth in turn gained a physical link with Monkwearmouth following the construction of a bridge, the Wearmouth Bridge, which was the world's second iron bridge (after the famous span at Ironbridge). It was built at the instigation of  During the

During the

The world's first steam dredger was built in Sunderland in 1796-7 and put to work on the river the following year. Designed by Stout's successor as Engineer, Jonathan Pickernell jr (in post from 1795 to 1804), it consisted of a set of 'bag and spoon' dredgers driven by a tailor-made 4-horsepower

The world's first steam dredger was built in Sunderland in 1796-7 and put to work on the river the following year. Designed by Stout's successor as Engineer, Jonathan Pickernell jr (in post from 1795 to 1804), it consisted of a set of 'bag and spoon' dredgers driven by a tailor-made 4-horsepower

Sunderland's shipbuilding industry continued to grow through most of the 19th century, becoming the town's dominant industry and a defining part of its identity. By 1815 it was 'the leading shipbuilding port for wooden trading vessels' with 600 ships constructed that year across 31 different yards. By 1840 the town had 76 shipyards and between 1820 and 1850 the number of ships being built on the Wear increased fivefold. From 1846 to 1854 almost a third of the UK's ships were built in Sunderland, and in 1850 the ''Sunderland Herald'' proclaimed the town to be the greatest shipbuilding port in the world.

The Durham & Sunderland Railway Co. built a railway line across the Town Moor and established a passenger terminus there in 1836. In 1847 the line was bought by George Hudson's

Sunderland's shipbuilding industry continued to grow through most of the 19th century, becoming the town's dominant industry and a defining part of its identity. By 1815 it was 'the leading shipbuilding port for wooden trading vessels' with 600 ships constructed that year across 31 different yards. By 1840 the town had 76 shipyards and between 1820 and 1850 the number of ships being built on the Wear increased fivefold. From 1846 to 1854 almost a third of the UK's ships were built in Sunderland, and in 1850 the ''Sunderland Herald'' proclaimed the town to be the greatest shipbuilding port in the world.

The Durham & Sunderland Railway Co. built a railway line across the Town Moor and established a passenger terminus there in 1836. In 1847 the line was bought by George Hudson's  In 1854 the Londonderry, Seaham & Sunderland Railway opened linking collieries to a separate set of staiths at Hudson Dock South, it also provided a passenger service from Sunderland to Seaham Harbour.

In 1886–90 a new Town Hall was built in Fawcett Street, just to the east of the railway station, designed by Brightwen Binyon. By 1889 two million tons of coal per year was passing through Hudson Dock, while to the south of Hendon Dock, the Wear Fuel Works distilled

In 1854 the Londonderry, Seaham & Sunderland Railway opened linking collieries to a separate set of staiths at Hudson Dock South, it also provided a passenger service from Sunderland to Seaham Harbour.

In 1886–90 a new Town Hall was built in Fawcett Street, just to the east of the railway station, designed by Brightwen Binyon. By 1889 two million tons of coal per year was passing through Hudson Dock, while to the south of Hendon Dock, the Wear Fuel Works distilled  The 20th century saw Sunderland A.F.C. established as the Wearside area's greatest claim to sporting fame. Founded in 1879 as Sunderland and District Teachers A.F.C. by schoolmaster James Allan, Sunderland joined

The 20th century saw Sunderland A.F.C. established as the Wearside area's greatest claim to sporting fame. Founded in 1879 as Sunderland and District Teachers A.F.C. by schoolmaster James Allan, Sunderland joined

From 1900 – 1919 an electric tram system was built and was gradually replaced by buses during the 1940s before being ended in 1954. In 1909 the

From 1900 – 1919 an electric tram system was built and was gradually replaced by buses during the 1940s before being ended in 1954. In 1909 the  The First World War increased shipbuilding, leading to being a target in a 1916

The First World War increased shipbuilding, leading to being a target in a 1916  With the outbreak of

With the outbreak of  Electronic, chemical, paper and motor manufacturing as well as the service sector expanded during the 1980s and 1990s to fill unemployment from heavy industry. In 1986 Japanese car manufacturer

Electronic, chemical, paper and motor manufacturing as well as the service sector expanded during the 1980s and 1990s to fill unemployment from heavy industry. In 1986 Japanese car manufacturer

Sunderland was created a

Sunderland was created a

Much of the city is located on a low range of hills running parallel to the coast. On average, it is around 80 metres

Much of the city is located on a low range of hills running parallel to the coast. On average, it is around 80 metres

Once hailed as the "Largest Shipbuilding Town in the World", ships were built on the Wear from at least 1346 onwards and by the mid-18th century Sunderland was one of the chief shipbuilding towns in the country. Sunderland Docks was the home of operations for the

Once hailed as the "Largest Shipbuilding Town in the World", ships were built on the Wear from at least 1346 onwards and by the mid-18th century Sunderland was one of the chief shipbuilding towns in the country. Sunderland Docks was the home of operations for the  Between 1939 and 1945 the Wear yards launched 245 merchant ships totalling 1.5 million tons, a quarter of the merchant tonnage produced in the UK at this period. Competition from overseas caused a downturn in demand for Sunderland built ships toward the end of the 20th century. The last shipyard in Sunderland closed on 7 December 1988.

Sunderland, part of the Durham coalfield, has a coal-mining heritage that dates back centuries. At its peak in 1923, 170,000 miners were employed in County Durham alone, as labourers from all over Britain, including many from

Between 1939 and 1945 the Wear yards launched 245 merchant ships totalling 1.5 million tons, a quarter of the merchant tonnage produced in the UK at this period. Competition from overseas caused a downturn in demand for Sunderland built ships toward the end of the 20th century. The last shipyard in Sunderland closed on 7 December 1988.

Sunderland, part of the Durham coalfield, has a coal-mining heritage that dates back centuries. At its peak in 1923, 170,000 miners were employed in County Durham alone, as labourers from all over Britain, including many from

In May 2002, the Tyne and Wear Metro was extended to Sunderland in an official ceremony attended by The Queen, 22 years after it originally opened in Newcastle upon Tyne. The Green line now stretches deeper into South Tyneside and into Sunderland; it incorporates Seaburn,

In May 2002, the Tyne and Wear Metro was extended to Sunderland in an official ceremony attended by The Queen, 22 years after it originally opened in Newcastle upon Tyne. The Green line now stretches deeper into South Tyneside and into Sunderland; it incorporates Seaburn,

Sunderland station opened in 1879 but was completely redesigned to facilitate football teams and officials from countries who were drawn to play at Roker Park during England's hosting of the 1966 World Cup. It is situated on an underground level. It was renovated in 2005, backed by the artistic team which designed the stations along the Wearside extension of the Tyne & Wear Metro in 2002. It is situated on the Durham Coast Line served by direct

Sunderland station opened in 1879 but was completely redesigned to facilitate football teams and officials from countries who were drawn to play at Roker Park during England's hosting of the 1966 World Cup. It is situated on an underground level. It was renovated in 2005, backed by the artistic team which designed the stations along the Wearside extension of the Tyne & Wear Metro in 2002. It is situated on the Durham Coast Line served by direct

A multimillion-pound transport interchange at

A multimillion-pound transport interchange at

The Port of Sunderland is the second largest municipally-owned port in the United Kingdom.

The port offers a total of 17 quays, which handle cargoes including forest products, non-ferrous metals, steel, aggregates and refined oil products, limestone, chemicals and maritime cranes. It also handles offshore supply vessels and has ship repair and drydocking facilities.

The river berths are deepwater and tidal, while the South Docks are entered via a lock with an beam restriction.

The Port of Sunderland is the second largest municipally-owned port in the United Kingdom.

The port offers a total of 17 quays, which handle cargoes including forest products, non-ferrous metals, steel, aggregates and refined oil products, limestone, chemicals and maritime cranes. It also handles offshore supply vessels and has ship repair and drydocking facilities.

The river berths are deepwater and tidal, while the South Docks are entered via a lock with an beam restriction.

The

The

The only professional sporting team in Sunderland is the

The only professional sporting team in Sunderland is the  On 18 April 2008, the Sunderland Aquatic Centre was opened. Constructed at a cost of £20 million, it is the only Olympic sized 50 m pool between

On 18 April 2008, the Sunderland Aquatic Centre was opened. Constructed at a cost of £20 million, it is the only Olympic sized 50 m pool between

Tyne and Wear

Tyne and Wear () is a metropolitan county in North East England, situated around the mouths of the rivers Tyne and Wear. It was created in 1974, by the Local Government Act 1972, along with five metropolitan boroughs of Gateshead, Newcas ...

, England. It is the City of Sunderland's administrative centre and in the historic county of Durham. The city is from Newcastle-upon-Tyne

Newcastle upon Tyne ( RP: , ), or simply Newcastle, is a city and metropolitan borough in Tyne and Wear, England. The city is located on the River Tyne's northern bank and forms the largest part of the Tyneside built-up area. Newcastle is ...

and is on the River Wear's mouth to the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian ...

. The river also flows through Durham roughly south-west of Sunderland City Centre

Sunderland City Centre is the central business district in Sunderland, Tyne and Wear, England. The city centre is just to the west of Sunderland Docks.

History

In 2020 it was announced that 14 million would be spent on a new car park in the ...

. It is the only other city in the county and the second largest settlement in the North East

The points of the compass are a set of horizontal, radially arrayed compass directions (or azimuths) used in navigation and cartography. A compass rose is primarily composed of four cardinal directions—north, east, south, and west—each sep ...

after Newcastle upon Tyne.

Locals from the city are sometimes known as Mackems. The term originated as recently as the early 1980s; its use and acceptance by residents, particularly among the older generations, is not universal. At one time, ships built on the Wear were called "Jamies", in contrast with those from the Tyne, which were known as "Geordies", although in the case of "Jamie" it is not known whether this was ever extended to people.

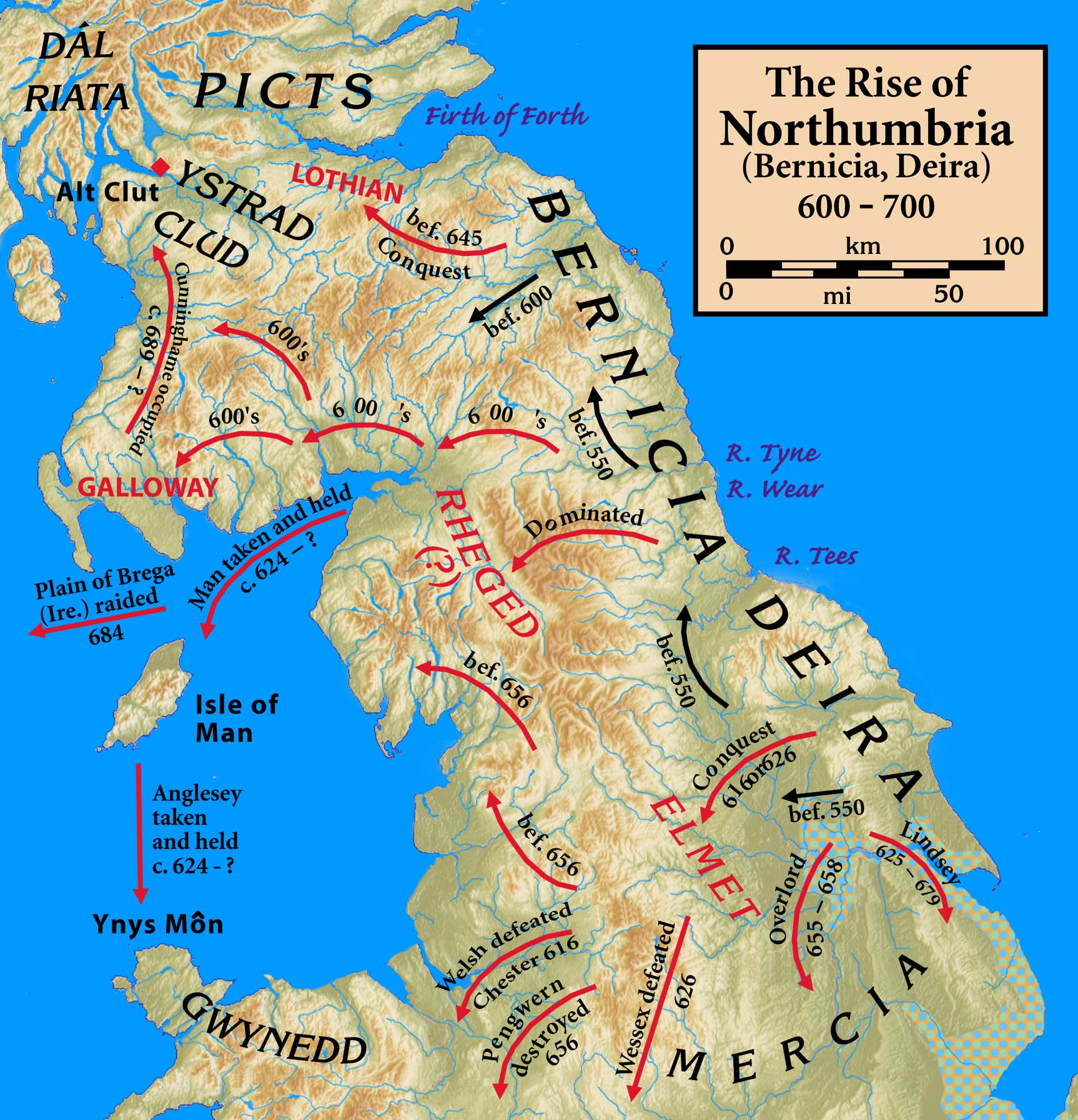

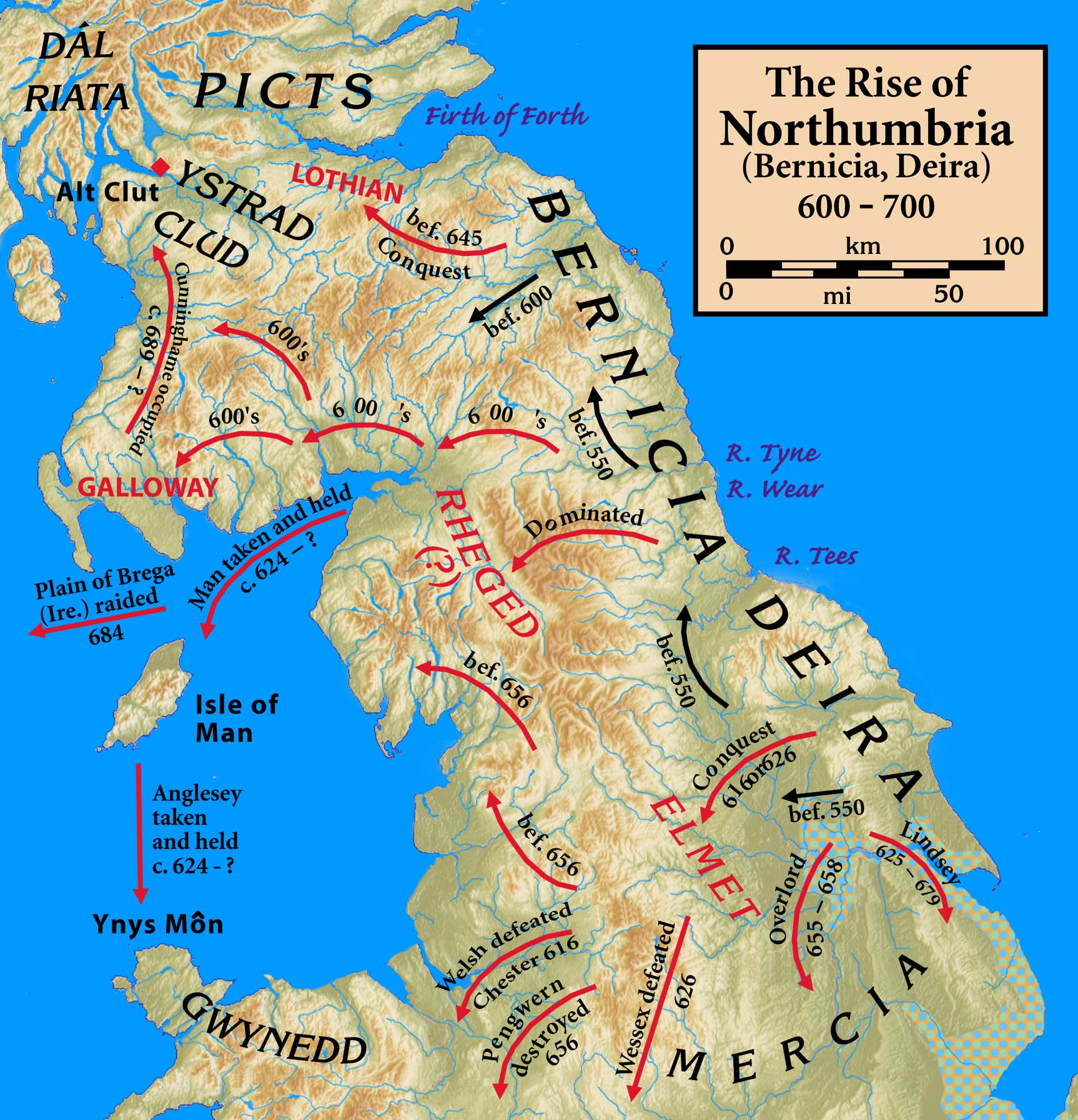

There were three original settlements by the River's mouth which are part of the modern-day city: Monkwearmouth, settled in 674 on the river's north bank with King Ecgfrith of Northumbria

la, Regnum Northanhymbrorum

, conventional_long_name = Kingdom of Northumbria

, common_name = Northumbria

, status = State

, status_text = Unified Anglian kingdom (before 876)North: Anglian kingdom (af ...

land granting to Benedict Biscop to found a monastery which, together with Jarrow

Jarrow ( or ) is a town in South Tyneside in the county of Tyne and Wear, England. It is east of Newcastle upon Tyne. It is situated on the south bank of the River Tyne, about from the east coast. It is home to the southern portal of the Ty ...

monastery, later formed the dual Monkwearmouth-Jarrow Abbey; Sunderland, settled in 685; and Bishopwearmouth, founded in 930. The later two are on the Wear's southern bank. The second settlement on the wear's mouth grew as a fishing settlement and later as a port, being granted a town charter in 1179. The city started to trade coal

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock, formed as rock strata called coal seams. Coal is mostly carbon with variable amounts of other elements, chiefly hydrogen, sulfur, oxygen, and nitrogen.

Coal is formed when ...

and salt

Salt is a mineral composed primarily of sodium chloride (NaCl), a chemical compound belonging to the larger class of salts; salt in the form of a natural crystalline mineral is known as rock salt or halite. Salt is present in vast quant ...

with ships starting to be built on the river in the 14th century. By the 19th century, with a population increase due to shipbuilding, port

A port is a maritime facility comprising one or more wharves or loading areas, where ships load and discharge cargo and passengers. Although usually situated on a sea coast or estuary, ports can also be found far inland, such as H ...

and docks, the town absorbed the other two settlements. Following decline of its traditional industries in the late 20th century, the area became an automotive building centre, science-and-technology and the service sector. In 1992, the borough of Sunderland was granted city status.

Toponymy

In 685, King Ecgfrith granted Benedict Biscop a "sunder-land". Also in 685The Venerable Bede

Bede ( ; ang, Bǣda , ; 672/326 May 735), also known as Saint Bede, The Venerable Bede, and Bede the Venerable ( la, Beda Venerabilis), was an English monk at the monastery of St Peter and its companion monastery of St Paul in the Kingdo ...

moved to the newly founded Jarrow monastery. He had started his monastic career at Monkwearmouth monastery and later wrote that he was "ácenned on ''sundorlande'' þæs ylcan mynstres" (born in a ''separate land'' of this same monastery). This can be taken as "sundorlande" (being Old English for "separate land") or the settlement of Sunderland. Alternatively, it is possible that Sunderland was later named in honour of Bede's connections to the area by people familiar with this statement of his.

History

Early, ancient and Medieval

The earliestinhabitants

Domicile is relevant to an individual's "personal law," which includes the law that governs a person's status and their property. It is independent of a person's nationality. Although a domicile may change from time to time, a person has only one ...

of the Sunderland area were Stone Age

The Stone Age was a broad prehistoric period during which stone was widely used to make tools with an edge, a point, or a percussion surface. The period lasted for roughly 3.4 million years, and ended between 4,000 BC and 2,000 BC, with ...

hunter-gatherer

A traditional hunter-gatherer or forager is a human living an ancestrally derived lifestyle in which most or all food is obtained by foraging, that is, by gathering food from local sources, especially edible wild plants but also insects, fung ...

s and artifacts from this era have been discovered, including microliths found during excavations at St Peter's Church, Monkwearmouth

St Peter's Church, Monkwearmouth is the parish church of Monkwearmouth in Sunderland, Tyne and Wear, England. It is one of three churches in the Parish of Monkwearmouth. The others are the Victorian All Saints' Church, Monkwearmouth and the Edwar ...

. During the final phase of the Stone Age, the Neolithic period (c. 4000 – c. 2000 BC), Hastings Hill

Hastings Hill is a suburb of Sunderland, Tyne and Wear, England.

Hastings Hill is a housing estate, close to the A19, and the Pennywell and Grindon areas of Sunderland. It was built as a private development in the late 1960s on an area of lan ...

, on the western outskirts of Sunderland, was a focal point of activity and a place of burial and ritual significance. Evidence includes the former presence of a cursus

250px, Stonehenge Cursus, Wiltshire

250px, Dorset Cursus terminal on Thickthorn Down, Dorset

Cursuses are monumental Neolithic structures resembling ditches or trenches in the islands of Great Britain and Ireland. Relics found within them in ...

monument.

It is believed the Brythonic

Brittonic or Brythonic may refer to:

*Common Brittonic, or Brythonic, the Celtic language anciently spoken in Great Britain

*Brittonic languages, a branch of the Celtic languages descended from Common Brittonic

*Britons (Celtic people)

The Br ...

-speaking Brigantes

The Brigantes were Ancient Britons who in pre-Roman times controlled the largest section of what would become Northern England. Their territory, often referred to as Brigantia, was centred in what was later known as Yorkshire. The Greek geog ...

inhabited the area around the River Wear

The River Wear (, ) in North East England rises in the Pennines and flows eastwards, mostly through County Durham to the North Sea in the City of Sunderland. At long, it is one of the region's longest rivers, wends in a steep valley through ...

in pre-Roman Britain

Roman Britain was the period in classical antiquity when large parts of the island of Great Britain were under occupation by the Roman Empire. The occupation lasted from AD 43 to AD 410. During that time, the territory conquered wa ...

. There is a long-standing local legend that there was a Roman settlement on the south bank of the River Wear on what is the site of the former Vaux Brewery, although no archaeological investigation has taken place.

In March 2021, a "trove" of Roman artefacts were recovered in the River Wear at North Hylton, including four stone anchors, a discovery of huge significance that may affirm a persistent theory of a Roman Dam or Port existing at the River Wear.

Recorded settlements at the mouth of the Wear date to 674, when an

Recorded settlements at the mouth of the Wear date to 674, when an Anglo-Saxon

The Anglo-Saxons were a cultural group who inhabited England in the Early Middle Ages. They traced their origins to settlers who came to Britain from mainland Europe in the 5th century. However, the ethnogenesis of the Anglo-Saxons happened wit ...

nobleman, Benedict Biscop, granted land by King Ecgfrith of Northumbria, founded the Wearmouth–Jarrow (''St Peter's'') monastery

A monastery is a building or complex of buildings comprising the domestic quarters and workplaces of monastics, monks or nuns, whether living in communities or alone (hermits). A monastery generally includes a place reserved for prayer whic ...

on the north bank of the river—an area that became known as Monkwearmouth. Biscop's monastery was the first built of stone in Northumbria

la, Regnum Northanhymbrorum

, conventional_long_name = Kingdom of Northumbria

, common_name = Northumbria

, status = State

, status_text = Unified Anglian kingdom (before 876)North: Anglian kingdom (af ...

. He employed glaziers from France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

and in doing he re-established glass making in Britain.

In 686 the community was taken over by Ceolfrid

Saint Ceolfrid (or Ceolfrith, ; c. 642 – 716) was an Anglo-Saxon Christian abbot and saint. He is best known as the warden of Bede from the age of seven until his death in 716. He was the Abbot of Monkwearmouth-Jarrow Abbey, and a major contri ...

, and Wearmouth–Jarrow became a major centre of learning and knowledge in Anglo-Saxon England

Anglo-Saxon England or Early Medieval England, existing from the 5th to the 11th centuries from the end of Roman Britain until the Norman conquest in 1066, consisted of various Anglo-Saxon kingdoms until 927, when it was united as the Kingdom of ...

with a library of around 300 volumes.

The Codex Amiatinus, described by White as the 'finest book in the world', was created at the monastery and was likely worked on by Bede

Bede ( ; ang, Bǣda , ; 672/326 May 735), also known as Saint Bede, The Venerable Bede, and Bede the Venerable ( la, Beda Venerabilis), was an English monk at the monastery of St Peter and its companion monastery of St Paul in the Kingdom ...

, who was born at Wearmouth in 673. This is one of the oldest monasteries still standing in England. While at the monastery, Bede completed the ''Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum

The ''Ecclesiastical History of the English People'' ( la, Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum), written by Bede in about AD 731, is a history of the Christian Churches in England, and of England generally; its main focus is on the conflict b ...

'' ''(The Ecclesiastical History of the English People)'' in 731, a feat which earned him the title ''The father of English history''.

In the late 8th century the Vikings

Vikings ; non, víkingr is the modern name given to seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded and se ...

raided the coast, and by the middle of the 9th century the monastery had been abandoned. Lands on the south side of the river were granted to the Bishop of Durham

The Bishop of Durham is the Anglican bishop responsible for the Diocese of Durham in the Province of York. The diocese is one of the oldest in England and its bishop is a member of the House of Lords. Paul Butler has been the Bishop of Durham ...

by Athelstan of England in 930; these became known as Bishopwearmouth and included settlements such as Ryhope

Ryhope ( ) is a coastal village along the southern boundary of the City of Sunderland, in Tyne and Wear, North East England. With a population of approximately 14,000, measured at 10.484 in the 2011 census, Ryhope is 2.9 miles to the centre of ...

which fall within the modern boundary of Sunderland.

In 1100, Bishopwearmouth parish included a fishing

Fishing is the activity of trying to catch fish. Fish are often caught as wildlife from the natural environment, but may also be caught from fish stocking, stocked bodies of water such as fish pond, ponds, canals, park wetlands and reservoirs. ...

village at the southern mouth of the river (now the East End) known as 'Soender-land' (which evolved into 'Sunderland'). This settlement was granted a charter

A charter is the grant of authority or rights, stating that the granter formally recognizes the prerogative of the recipient to exercise the rights specified. It is implicit that the granter retains superiority (or sovereignty), and that the re ...

in 1179 by Hugh Pudsey, then the Bishop of Durham

The Bishop of Durham is the Anglican bishop responsible for the Diocese of Durham in the Province of York. The diocese is one of the oldest in England and its bishop is a member of the House of Lords. Paul Butler has been the Bishop of Durham ...

(who had quasi- monarchical power within the County Palatine

In England, Wales and Ireland a county palatine or palatinate was an area ruled by a hereditary nobleman enjoying special authority and autonomy from the rest of a kingdom. The name derives from the Latin adjective ''palātīnus'', "relating t ...

); the charter gave its merchants the same rights as those of Newcastle-upon-Tyne

Newcastle upon Tyne ( RP: , ), or simply Newcastle, is a city and metropolitan borough in Tyne and Wear, England. The city is located on the River Tyne's northern bank and forms the largest part of the Tyneside built-up area. Newcastle is ...

, but it nevertheless took time for Sunderland to develop as a port

A port is a maritime facility comprising one or more wharves or loading areas, where ships load and discharge cargo and passengers. Although usually situated on a sea coast or estuary, ports can also be found far inland, such as H ...

. Fishing was the main commercial activity at the time: mainly herring in the 13th century, then salmon

Salmon () is the common name for several commercially important species of euryhaline ray-finned fish from the family Salmonidae, which are native to tributaries of the North Atlantic (genus '' Salmo'') and North Pacific (genus '' Onco ...

in the 14th and 15th centuries. From 1346 ships were being built at Wearmouth, by a merchant named Thomas Menville, and by 1396 a small amount of coal was being exported.Jamies and Black Cats

Rapid growth of the port was prompted by the salt trade. Salt exports from Sunderland are recorded from as early as the 13th century, by 1589 salt pans were laid at Bishopwearmouth Panns (the modern-day name of the area the pans occupied is Pann's Bank, on the river bank between the city centre and the East End). Large vats ofseawater

Seawater, or salt water, is water from a sea or ocean. On average, seawater in the world's oceans has a salinity of about 3.5% (35 g/L, 35 ppt, 600 mM). This means that every kilogram (roughly one liter by volume) of seawater has appro ...

were heated using coal; as the water evaporated, the salt remained. As coal was required to heat the salt pans, a coal mining

Coal mining is the process of extracting coal from the ground. Coal is valued for its energy content and since the 1880s has been widely used to generate electricity. Steel and cement industries use coal as a fuel for extraction of iron from ...

community began to emerge. Only poor-quality coal was used in salt panning; better-quality coal was traded via the port, which subsequently began to grow.

Both salt and coal continued to be exported through the 17th century, with the coal trade growing significantly (2–3,000 tons of coal were exported from Sunderland in the year 1600; by 1680 this had increased to 180,000 tons). Difficulty for colliers trying to navigate the Wear’s shallow waters meant coal mined further inland was loaded onto keels (large, flat-bottomed boats) and taken downriver to the waiting colliers. A close-knit group of workers manned the Keels as ' keelmen'. In 1634 a market and yearly fair charter was granted by Bishop Thomas Morton, incorporated the settlement as a town.

Before the civil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polici ...

and with the exclusion of Kingston upon Hull

Kingston upon Hull, usually abbreviated to Hull, is a port city and unitary authority in the East Riding of Yorkshire, England.

It lies upon the River Hull at its confluence with the Humber Estuary, inland from the North Sea and south- ...

, the North declared for the King. In 1644 the North was captured by the Roundheads (Parliamentarians), the area itself taken in March of that year. One artifact of the civil war in the area was the long trench; a tactic of later warfare. In the village of Offerton roughly three miles inland from the present city centre, skirmishes occurred. The Roundheads blockaded the River Tyne

The River Tyne is a river in North East England. Its length (excluding tributaries) is . It is formed by the North Tyne and the South Tyne, which converge at Warden Rock near Hexham in Northumberland at a place dubbed 'The Meeting of the Wat ...

, crippling the Newcastle coal trade, which allowed a short period of flourishing coal trade on the Wear.

In 1669, after the Restoration, King Charles II granted letters patent

Letters patent ( la, litterae patentes) ( always in the plural) are a type of legal instrument in the form of a published written order issued by a monarch, president or other head of state, generally granting an office, right, monopoly, tit ...

to one Edward Andrew, Esq. to 'build a pier and erect a lighthouse or lighthouses and cleanse the harbour of Sunderland'. They was a tonnage

Tonnage is a measure of the cargo-carrying capacity of a ship, and is commonly used to assess fees on commercial shipping. The term derives from the taxation paid on ''tuns'' or casks of wine. In modern maritime usage, "tonnage" specifically r ...

duty levy on shipping in order to raise the necessary funds. They was a growing number of shipbuilders or boatbuilders active on the River Wear in the late 17th century.

By the start of the 18th century the banks of the Wear were described as being studded with small shipyards, as far as the tide flowed. After 1717, measures having been taken to increase the depth of the river, Sunderland's shipbuilding trade grew substantially (in parallel with its coal exports). A number of warships were built, alongside many commercial sailing ships. By the middle of the century the town was probably the premier shipbuilding centre in Britain. By 1788 Sunderland was Britain's fourth largest port (by measure of tonnage) after London, Newcastle and Liverpool; among these it was the leading coal exporter (though it did not rival Newcastle in terms of home coal trade). Still further growth was driven across the region, towards the end of the century, by London's insatiable demand for coal during the

By the start of the 18th century the banks of the Wear were described as being studded with small shipyards, as far as the tide flowed. After 1717, measures having been taken to increase the depth of the river, Sunderland's shipbuilding trade grew substantially (in parallel with its coal exports). A number of warships were built, alongside many commercial sailing ships. By the middle of the century the town was probably the premier shipbuilding centre in Britain. By 1788 Sunderland was Britain's fourth largest port (by measure of tonnage) after London, Newcastle and Liverpool; among these it was the leading coal exporter (though it did not rival Newcastle in terms of home coal trade). Still further growth was driven across the region, towards the end of the century, by London's insatiable demand for coal during the French Revolutionary Wars

The French Revolutionary Wars (french: Guerres de la Révolution française) were a series of sweeping military conflicts lasting from 1792 until 1802 and resulting from the French Revolution. They pitted France against Britain, Austria, Pruss ...

.

In 1719, the parish of Sunderland was carved from the densely populated east end of Bishopwearmouth by the establishment of a new parish church,

In 1719, the parish of Sunderland was carved from the densely populated east end of Bishopwearmouth by the establishment of a new parish church, Holy Trinity Church, Sunderland

Holy Trinity Church (sometimes Church of the Holy Trinity or Sunderland Parish Church) is an Anglican church building in Sunderland, Tyne and Wear formerly the area's parish church. It was opened in 1719 as the church for the newly created Pari ...

(today also known as Sunderland Old Parish Church). Later, in 1769, St John's Church was built as a chapel of ease

A chapel of ease (or chapel-of-ease) is a church building other than the parish church, built within the bounds of a parish for the attendance of those who cannot reach the parish church conveniently.

Often a chapel of ease is deliberately bu ...

within Holy Trinity parish; built by a local coal fitter, John Thornhill, it stood in Prospect Row to the north-east of the parish church. (St John's was demolished in 1972.) By 1720 the port area was completely built up, with large houses and gardens facing the Town Moor and the sea, and labourers' dwellings vying with manufactories alongside the river. The three original settlements of Wearmouth (Bishopwearmouth, Monkwearmouth and Sunderland) had started to combine, driven by the success of the port of Sunderland, salt panning and shipbuilding along the banks of the river. Around this time, Sunderland was known as 'Sunderland-near-the-Sea'.

Sunderland's third-biggest export, after coal and salt, was glass. The town's first modern glassworks were established in the 1690s and the industry grew through the 17th century. Its flourishing was aided by trading ships bringing good-quality sand (as ballast) from the Baltic and elsewhere which, together with locally available limestone (and coal to fire the furnaces) was a key ingredient in the glassmaking

Glass production involves two main methods – the float glass process that produces sheet glass, and glassblowing that produces bottles and other containers. It has been done in a variety of ways during the history of glass.

Glass contain ...

process. Other industries that developed alongside the river included lime burning

A lime kiln is a kiln used for the calcination of limestone ( calcium carbonate) to produce the form of lime called quicklime (calcium oxide). The chemical equation for this reaction is

: CaCO3 + heat → CaO + CO2

This reaction can take pla ...

and pottery making

Pottery is the process and the products of forming vessels and other objects with clay and other ceramic materials, which are fired at high temperatures to give them a hard and durable form. Major types include earthenware, stoneware and por ...

(the town's first commercial pottery manufactory, the Garrison Pottery, had opened in old Sunderland in 1750).

By 1770 Sunderland had spread westwards along its High Street to join up with Bishopwearmouth. In 1796 Bishopwearmouth in turn gained a physical link with Monkwearmouth following the construction of a bridge, the Wearmouth Bridge, which was the world's second iron bridge (after the famous span at Ironbridge). It was built at the instigation of

By 1770 Sunderland had spread westwards along its High Street to join up with Bishopwearmouth. In 1796 Bishopwearmouth in turn gained a physical link with Monkwearmouth following the construction of a bridge, the Wearmouth Bridge, which was the world's second iron bridge (after the famous span at Ironbridge). It was built at the instigation of Rowland Burdon Rowland Burdon may refer to:

* Rowland Burdon (1857–1944), MP for Sedgefield

*Rowland Burdon (died 1838)

Rowland Burdon ('' c.'' 1757 – 17 September 1838) was an English landowner and Tory politician from Castle Eden in County Durham.

L ...

, the Member of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members o ...

(MP) for County Durham

County Durham ( ), officially simply Durham,UK General Acts 1997 c. 23Lieutenancies Act 1997 Schedule 1(3). From legislation.gov.uk, retrieved 6 April 2022. is a ceremonial county in North East England.North East Assembly �About North East E ...

, and described by Nikolaus Pevsner

Sir Nikolaus Bernhard Leon Pevsner (30 January 1902 – 18 August 1983) was a German-British art historian and architectural historian best known for his monumental 46-volume series of county-by-county guides, '' The Buildings of England'' ...

as being 'a triumph of the new metallurgy and engineering ingenuity ..of superb elegance'. Spanning the river in a single sweep of , it was over twice the length of the earlier bridge at Ironbridge but only three-quarters the weight. At the time of building, it was the biggest single-span bridge in the world; and because Sunderland had developed on a plateau above the river, it never suffered from the problem of interrupting the passage of high-masted vessels.

During the

During the War of Jenkins' Ear

The War of Jenkins' Ear, or , was a conflict lasting from 1739 to 1748 between Britain and the Spanish Empire. The majority of the fighting took place in New Granada and the Caribbean Sea, with major operations largely ended by 1742. It is con ...

a pair of gun batteries were built (in 1742 and 1745) on the shoreline to the south of the South Pier, to defend the river from attack (a further battery was built on the cliff top in Roker, ten years later). One of the pair was washed away by the sea in 1780, but the other was expanded during the French Revolutionary Wars

The French Revolutionary Wars (french: Guerres de la Révolution française) were a series of sweeping military conflicts lasting from 1792 until 1802 and resulting from the French Revolution. They pitted France against Britain, Austria, Pruss ...

and became known as the Black Cat Battery. In 1794 Sunderland Barracks

Sunderland Barracks was a military installation in the old east end of Sunderland, built as part of the British response to the threat of the French Revolution.

History

In early 1794 the Corporation of Sunderland petitioned for a barracks to be ...

were built, behind the battery, close to what was then the tip of the headland.

The world's first steam dredger was built in Sunderland in 1796-7 and put to work on the river the following year. Designed by Stout's successor as Engineer, Jonathan Pickernell jr (in post from 1795 to 1804), it consisted of a set of 'bag and spoon' dredgers driven by a tailor-made 4-horsepower

The world's first steam dredger was built in Sunderland in 1796-7 and put to work on the river the following year. Designed by Stout's successor as Engineer, Jonathan Pickernell jr (in post from 1795 to 1804), it consisted of a set of 'bag and spoon' dredgers driven by a tailor-made 4-horsepower Boulton & Watt

Boulton & Watt was an early British engineering and manufacturing firm in the business of designing and making marine and stationary steam engines. Founded in the English West Midlands around Birmingham in 1775 as a partnership between the Eng ...

beam engine. It was designed to dredge to a maximum depth of below the waterline and remained in operation until 1804, when its constituent parts were sold as separate lots. Onshore, numerous small industries supported the business of the burgeoning port. In 1797 the world's first patent ropery (producing machine-made rope

A rope is a group of yarns, plies, fibres, or strands that are twisted or braided together into a larger and stronger form. Ropes have tensile strength and so can be used for dragging and lifting. Rope is thicker and stronger than similarl ...

, rather than using a ropewalk) was built in Sunderland, using a steam-powered hemp-spinning machine which had been devised by a local schoolmaster, Richard Fothergill, in 1793; the ropery building still stands, in the Deptford area of the city.

"The greatest shipbuilding port in the world"

Sunderland's shipbuilding industry continued to grow through most of the 19th century, becoming the town's dominant industry and a defining part of its identity. By 1815 it was 'the leading shipbuilding port for wooden trading vessels' with 600 ships constructed that year across 31 different yards. By 1840 the town had 76 shipyards and between 1820 and 1850 the number of ships being built on the Wear increased fivefold. From 1846 to 1854 almost a third of the UK's ships were built in Sunderland, and in 1850 the ''Sunderland Herald'' proclaimed the town to be the greatest shipbuilding port in the world.

The Durham & Sunderland Railway Co. built a railway line across the Town Moor and established a passenger terminus there in 1836. In 1847 the line was bought by George Hudson's

Sunderland's shipbuilding industry continued to grow through most of the 19th century, becoming the town's dominant industry and a defining part of its identity. By 1815 it was 'the leading shipbuilding port for wooden trading vessels' with 600 ships constructed that year across 31 different yards. By 1840 the town had 76 shipyards and between 1820 and 1850 the number of ships being built on the Wear increased fivefold. From 1846 to 1854 almost a third of the UK's ships were built in Sunderland, and in 1850 the ''Sunderland Herald'' proclaimed the town to be the greatest shipbuilding port in the world.

The Durham & Sunderland Railway Co. built a railway line across the Town Moor and established a passenger terminus there in 1836. In 1847 the line was bought by George Hudson's York and Newcastle Railway

The York, Newcastle and Berwick Railway (YN&BR) was an English railway company formed in 1847 by the amalgamation of the York and Newcastle Railway and the Newcastle and Berwick Railway. Both companies were part of the group of business interest ...

. Hudson, nicknamed 'The Railway King', was Member of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members o ...

for Sunderland

Sunderland () is a port city in Tyne and Wear, England. It is the City of Sunderland's administrative centre and in the Historic counties of England, historic county of County of Durham, Durham. The city is from Newcastle-upon-Tyne and is on t ...

and was already involved in a scheme to build a dock in the area. In 1846 he had formed the Sunderland Dock Company, which received parliamentary approval for the construction of a dock between the South Pier and Hendon Bay.

Increasing industrialisation had prompted residents an expansion away from the old port area in the suburban terraces of the Fawcett Estate and Mowbray Park. The area around Fawcett Street itself increasingly functioned as the civic and commercial town centre.

Marine engineering works were established from the 1820s onwards, initially providing engines for paddle steamers; in 1845 a ship named ''Experiment'' was the first of many to be converted to steam screw propulsion. Demand for steam-powered vessels increased during the Crimean War

The Crimean War, , was fought from October 1853 to February 1856 between Russia and an ultimately victorious alliance of the Ottoman Empire, France, the United Kingdom and Piedmont-Sardinia.

Geopolitical causes of the war included the ...

; nonetheless, sailing ships continued to be built, including fast fully-rigged

A full-rigged ship or fully rigged ship is a sailing vessel's sail plan with three or more masts, all of them square-rigged. A full-rigged ship is said to have a ship rig or be ship-rigged. Such vessels also have each mast stepped in three seg ...

composite

Composite or compositing may refer to:

Materials

* Composite material, a material that is made from several different substances

** Metal matrix composite, composed of metal and other parts

** Cermet, a composite of ceramic and metallic materials ...

-built clipper

A clipper was a type of mid-19th-century merchant sailing vessel, designed for speed. Clippers were generally narrow for their length, small by later 19th century standards, could carry limited bulk freight, and had a large total sail area. "Cl ...

s, including the ''City of Adelaide'' in 1864 and ''Torrens'' (the last such vessel ever built), in 1875.

By the middle of the century glassmaking was at its height on Wearside. James Hartley & Co., established in Sunderland in 1836, grew to be the largest glassworks in the country and (having patented an innovative production technique for rolled plate glass Rolled plate is a type of industrially produced glass

Glass is a non-crystalline, often transparent, amorphous solid that has widespread practical, technological, and decorative use in, for example, window panes, tableware, and optics. Gla ...

) produced much of the glass used in the construction of the Crystal Palace

The Crystal Palace was a cast iron and plate glass structure, originally built in Hyde Park, London, Hyde Park, London, to house the Great Exhibition of 1851. The exhibition took place from 1 May to 15 October 1851, and more than 14,000 exhibit ...

in 1851. A third of all UK-manufactured plate glass was produced at Hartley's by this time. Other manufacturers included the Cornhill Flint Glassworks (established at Southwick in 1865), which went on to specialise in pressed glass, as did the Wear Flint Glassworks (which had originally been established in 1697). In addition to the plate glass and pressed glass manufacturers there were 16 bottle works on the Wear in the 1850s, with the capacity to produce between 60 and 70,000 bottles a day.

In 1848 George Hudson's York, Newcastle and Berwick Railway built a passenger terminus, Monkwearmouth Station, just north of Wearmouth Bridge; and south of the river another passenger terminus, in Fawcett Street, in 1853. Later, Thomas Elliot Harrison (chief engineer to the North Eastern Railway) made plans to carry the railway across the river; the Wearmouth Railway Bridge (reputedly 'the largest Hog-Back iron girder bridge in the world') opened in 1879.

In 1854 the Londonderry, Seaham & Sunderland Railway opened linking collieries to a separate set of staiths at Hudson Dock South, it also provided a passenger service from Sunderland to Seaham Harbour.

In 1886–90 a new Town Hall was built in Fawcett Street, just to the east of the railway station, designed by Brightwen Binyon. By 1889 two million tons of coal per year was passing through Hudson Dock, while to the south of Hendon Dock, the Wear Fuel Works distilled

In 1854 the Londonderry, Seaham & Sunderland Railway opened linking collieries to a separate set of staiths at Hudson Dock South, it also provided a passenger service from Sunderland to Seaham Harbour.

In 1886–90 a new Town Hall was built in Fawcett Street, just to the east of the railway station, designed by Brightwen Binyon. By 1889 two million tons of coal per year was passing through Hudson Dock, while to the south of Hendon Dock, the Wear Fuel Works distilled coal tar

Coal tar is a thick dark liquid which is a by-product of the production of coke and coal gas from coal. It is a type of creosote. It has both medical and industrial uses. Medicinally it is a topical medication applied to skin to treat pso ...

to produce pitch, oil and other products.

The 20th century saw Sunderland A.F.C. established as the Wearside area's greatest claim to sporting fame. Founded in 1879 as Sunderland and District Teachers A.F.C. by schoolmaster James Allan, Sunderland joined

The 20th century saw Sunderland A.F.C. established as the Wearside area's greatest claim to sporting fame. Founded in 1879 as Sunderland and District Teachers A.F.C. by schoolmaster James Allan, Sunderland joined The Football League

The English Football League (EFL) is a league of professional association football, football clubs from England and Wales. Founded in 1888 as the Football League, the league is the oldest such competition in Association football around the wor ...

for the 1890–91 season.

Mackem

From 1900 – 1919 an electric tram system was built and was gradually replaced by buses during the 1940s before being ended in 1954. In 1909 the

From 1900 – 1919 an electric tram system was built and was gradually replaced by buses during the 1940s before being ended in 1954. In 1909 the Queen Alexandra Bridge

The Queen Alexandra Bridge is a road traffic, pedestrian and former railway bridge spanning the River Wear in North East England, linking the Deptford and Southwick areas of Sunderland. The steel truss bridge was designed by Charles A. Har ...

was built, linking Deptford and Southwick.

The First World War increased shipbuilding, leading to being a target in a 1916

The First World War increased shipbuilding, leading to being a target in a 1916 Zeppelin

A Zeppelin is a type of rigid airship named after the German inventor Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin () who pioneered rigid airship development at the beginning of the 20th century. Zeppelin's notions were first formulated in 1874Eckener 1938, pp ...

raid and Monkwearmouth struck on 1 April 1916 and 22 people died. Over 25,000 men from a population of 151,000 served in the armed forces during the war.

Through the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

of the 1930s, shipbuilding dramatically declined: shipyards on the Wear went from 15 in 1921 to six in 1937. The small yards of J. Blumer & Son (at North Dock) and the Sunderland Shipbuilding Co. Ltd. (at Hudson Dock) both closed in the 1920s, and other yards were closed down by National Shipbuilders Securities

National Shipbuilders Security was a UK Government body established in 1930, under the Chairmanship of Sir James Lithgow, of the eponymous Clyde shipbuilding giant Lithgows. The remit of National Shipbuilders Security was to remove over-capacit ...

in the 1930s.

By 1936 the Sunderland AFC had been league champions on five occasions. They won their first FA Cup

The Football Association Challenge Cup, more commonly known as the FA Cup, is an annual knockout football competition in men's domestic English football. First played during the 1871–72 season, it is the oldest national football compet ...

in 1937

Events

January

* January 1 – Anastasio Somoza García becomes President of Nicaragua.

* January 5 – Water levels begin to rise in the Ohio River in the United States, leading to the Ohio River flood of 1937, which continues into ...

.

With the outbreak of

With the outbreak of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

in 1939, Sunderland was a key target of the German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

Luftwaffe

The ''Luftwaffe'' () was the aerial-warfare branch of the German '' Wehrmacht'' before and during World War II. Germany's military air arms during World War I, the '' Luftstreitkräfte'' of the Imperial Army and the '' Marine-Fliegerabt ...

bombing, 267 people died and local industries destroyed. and damage or destruction to 4,000 homes.

Many old buildings remain despite the bombing that occurred during World War II. Religious buildings include Holy Trinity Church, built in 1719 for an independent Sunderland, St Michael's Church, built as Bishopwearmouth Parish Church and now known as Sunderland Minster and St Peter's Church, Monkwearmouth, part of which dates from AD 674, and was the original monastery. St Andrew's Church, Roker

St Andrew's, Roker (1905-7) is a Church of England parish church in Sunderland, England. It is recognised as one of the finest churches of the first half of the twentieth century and the masterpiece of Edward Schroeder Prior. The design of S ...

, known as the "Cathedral of the Arts and Crafts Movement", contains work by William Morris

William Morris (24 March 1834 – 3 October 1896) was a British textile designer, poet, artist, novelist, architectural conservationist, printer, translator and socialist activist associated with the British Arts and Crafts Movement. He w ...

, Ernest Gimson and Eric Gill

Arthur Eric Rowton Gill, (22 February 1882 – 17 November 1940) was an English sculptor, letter cutter, typeface designer, and printmaker. Although the '' Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'' describes Gill as ″the greatest artist-cr ...

. St Mary's Catholic Church is the earliest surviving Gothic revival church in the city. After the war, more housing was built and the town's boundaries expanded in 1967 when neighbouring Ryhope

Ryhope ( ) is a coastal village along the southern boundary of the City of Sunderland, in Tyne and Wear, North East England. With a population of approximately 14,000, measured at 10.484 in the 2011 census, Ryhope is 2.9 miles to the centre of ...

, Silksworth

Silksworth is a suburb of the City of Sunderland, Tyne and Wear. The area can be distinguished into two parts, old Silksworth, the original village and township which has existed since the early middle ages, and New Silksworth, the industrial ...

, Herrington, South Hylton

South Hylton () is a suburb of Sunderland, Tyne and Wear, England. Lying west of Sunderland city centre on the south bank of the River Wear, South Hylton has a population of 10,317 ( 2001 Census). Once a small industrial village, South Hylton (w ...

and Castletown were incorporated. Sunderland AFC one their only post-World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

major honour in 1973 when they won a second FA Cup.

Shipbuilding ended in 1988 and coal-mining in 1993 after a mid-1980s unemployment crisis with 20 per cent of the local workforce unemployed in the town.

Nissan

, trading as Nissan Motor Corporation and often shortened to Nissan, is a Japanese multinational automobile manufacturer headquartered in Nishi-ku, Yokohama, Japan. The company sells its vehicles under the Nissan, Infiniti, and Datsun bra ...

opened its Nissan Motor Manufacturing UK factory in Washington, which has since become the UK's largest car factory.

City status

Sunderland received city status in 1992. Like many cities, Sunderland comprises a number of areas with their own distinct histories, Fulwell, Monkwearmouth, Roker, and Southwick on the northern side of the Wear, and Bishopwearmouth and Hendon to the south. From 1990, the Wear’s riverbanks were regenerated with new housing, retail parks and business centres on former shipbuilding sites; the National Glass Centre, a newUniversity of Sunderland

, mottoeng = Sweetly absorbing knowledge

, established = 1901 - Sunderland Technical College1969 - Sunderland Polytechnic1992 - University of Sunderland (gained university status)

, staff =

, chancellor = Emel ...

campus on the St Peter's site were also built. The Vaux Breweries

Vaux Brewery was a major brewer and hotel owner based in Sunderland, England. The company was listed on the London Stock Exchange. It was taken over by Whitbread in 2000.

History

The company was founded in 1806 by Cuthbert Vaux (1779–1850), pr ...

site was clear on the north west fringe of the city centre for further development opportunities in the city centre.

After 99 years at the historic Roker Park stadium, the club moved to the 42,000-seat Stadium of Light on the banks of the River Wear in 1997. At the time, it was the largest stadium built by an English football club since the 1920s, and has since been expanded to hold nearly 50,000 seated spectators.

On 24 March 2004, the city adopted Benedict Biscop as its patron saint

A patron saint, patroness saint, patron hallow or heavenly protector is a saint who in Catholicism, Anglicanism, or Eastern Orthodoxy is regarded as the heavenly advocate of a nation, place, craft, activity, class, clan, family, or perso ...

. In 2018 the city was ranked as the best to live and work in the UK by the finance firm OneFamily. In the same year, the city was ranked as one of the top 10 safest in the UK.

The 1970 Sunderland Civic Centre

Sunderland Civic Centre was a municipal building in the Burdon Road in Sunderland, Tyne and Wear, England. It was the headquarters of Sunderland City Council until November 2021.

History

After Sunderland became a municipal borough in 1835, civ ...

closed in November 2021, following the opening of a new City Hall

In local government, a city hall, town hall, civic centre (in the UK or Australia), guildhall, or a municipal building (in the Philippines), is the chief administrative building of a city, town, or other municipality. It usually houses ...

on the former Vaux Brewery redevelopment site.

Governance

Sunderland was created a

Sunderland was created a municipal borough

Municipal boroughs were a type of local government district which existed in England and Wales between 1835 and 1974, in Northern Ireland from 1840 to 1973 and in the Republic of Ireland from 1840 to 2002. Broadly similar structures existed in S ...

of County Durham

County Durham ( ), officially simply Durham,UK General Acts 1997 c. 23Lieutenancies Act 1997 Schedule 1(3). From legislation.gov.uk, retrieved 6 April 2022. is a ceremonial county in North East England.North East Assembly �About North East E ...

in 1835. Under the Local Government Act 1888, it was given the status of a County Borough, independent from county council

A county council is the elected administrative body governing an area known as a county. This term has slightly different meanings in different countries.

Ireland

The county councils created under British rule in 1899 continue to exist in Irela ...

control. Sunderland has the motto of ''Nil Desperandum Auspice Deo'' or ''Under God's guidance we may never despair''.

In 1974, under the Local Government Act 1972

The Local Government Act 1972 (c. 70) is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that reformed local government in England and Wales on 1 April 1974. It was one of the most significant Acts of Parliament to be passed by the Heath Gov ...

, the county borough was abolished and its area combined with that of other districts to form the Metropolitan Borough of Sunderland in Tyne and Wear metropolitan county

The metropolitan counties are a type of county-level administrative division of England. There are six metropolitan counties, which each cover large urban areas, with populations between 1 and 3 million. They were created in 1974 and are each di ...

. The Northumbria Police

Northumbria Police is a territorial police force in England. It is responsible for policing the metropolitan boroughs of Newcastle upon Tyne, Gateshead, North Tyneside, South Tyneside and the City of Sunderland, as well as the ceremonial cou ...

(covering Tyne and Wear and Northumberland

Northumberland () is a county in Northern England, one of two counties in England which border with Scotland. Notable landmarks in the county include Alnwick Castle, Bamburgh Castle, Hadrian's Wall and Hexham Abbey.

It is bordered by land ...

) and Tyne and Wear Fire and Rescue Service (covering the county only) were also formed.

In 1986, Tyne and Wear County Council

Tyne and Wear County Council was the county council of the metropolitan county of Tyne and Wear in northeast England. It came into its powers on 1 April 1974 and was abolished on 1 April 1986. The county council was based at Sandyford House in Ne ...

was abolished, and Sunderland became a unitary authority

A unitary authority is a local authority responsible for all local government functions within its area or performing additional functions that elsewhere are usually performed by a higher level of sub-national government or the national governmen ...

in all but name, once again independent from county council control but still in the county with joint bodies such as a passenger transport executive covering the area. The metropolitan borough was granted city status after winning a competition in 1992 to celebrate the Queen's 40th year on the throne.

The council area's population (taken at the 2011 Census) was 275,506. Since 2014, the City of Sunderland has been a member of the North East Combined Authority

The North East Combined Authority, abbreviated to NECA, is one of three combined authorities in North East England. It was created in 2014, and currently consists of the City of Sunderland; Metropolitan Borough of Gateshead, South Tyneside; ...

; initially Tyne and Wear

Tyne and Wear () is a metropolitan county in North East England, situated around the mouths of the rivers Tyne and Wear. It was created in 1974, by the Local Government Act 1972, along with five metropolitan boroughs of Gateshead, Newcas ...

, Northumberland

Northumberland () is a county in Northern England, one of two counties in England which border with Scotland. Notable landmarks in the county include Alnwick Castle, Bamburgh Castle, Hadrian's Wall and Hexham Abbey.

It is bordered by land ...

and the County Durham District

County Durham is a unitary authority in the ceremonial county of Durham, North East England. It covers the former non-metropolitan county and its seven districts: Durham (city), Easington, Sedgefield (borough), Teesdale, Wear Valley, Derwent ...

. The Tyne and Wear Passenger Transport Executive

Tyne and Wear PTE, branded as Nexus, is an executive body of the North East Joint Transport Committee and is best known for owning and operating the Tyne and Wear Metro. It replaced the Tyneside PTE on 1 April 1974.

Operations

TWPTE is respo ...

, branded as Nexus, became an executive body of the North East Combined Authority

The North East Combined Authority, abbreviated to NECA, is one of three combined authorities in North East England. It was created in 2014, and currently consists of the City of Sunderland; Metropolitan Borough of Gateshead, South Tyneside; ...

. The combined authority split along the Tyne in 2018 with the borough remaining with Gateshead

Gateshead () is a large town in northern England. It is on the River Tyne's southern bank, opposite Newcastle to which it is joined by seven bridges. The town contains the Millennium Bridge, The Sage, and the Baltic Centre for Contemporary ...

, South Tyneside and the County Durham District

County Durham is a unitary authority in the ceremonial county of Durham, North East England. It covers the former non-metropolitan county and its seven districts: Durham (city), Easington, Sedgefield (borough), Teesdale, Wear Valley, Derwent ...

. The split may be resolved with talks to recombine the two combined authorities, including the County Durham district or (covering same area as the local police force) without the district.

Voting

Sunderland voted forBrexit

Brexit (; a portmanteau of "British exit") was the Withdrawal from the European Union, withdrawal of the United Kingdom (UK) from the European Union (EU) at 23:00 Greenwich Mean Time, GMT on 31 January 2020 (00:00 1 February 2020 Central Eur ...

in the 2016 referendum on European Union membership by 61% of the vote; an unexpectedly high margin. The ''New Statesman

The ''New Statesman'' is a British political and cultural magazine published in London. Founded as a weekly review of politics and literature on 12 April 1913, it was at first connected with Sidney and Beatrice Webb and other leading members ...

'' and ''The Daily Telegraph

''The Daily Telegraph'', known online and elsewhere as ''The Telegraph'', is a national British daily broadsheet newspaper published in London by Telegraph Media Group and distributed across the United Kingdom and internationally.

It was f ...

'' have described Sunderland as the poster city for Brexit.

For decades, Sunderland has been an electoral stronghold of the Labour Party. Sunderland is represented in the House of Commons in the Parliament of the United Kingdom

The Parliament of the United Kingdom is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace of Westminster, London. It alone possesses legislative suprem ...

by three Labour Members of Parliament; Bridget Phillipson since 2020, Julie Elliott

Julie Elliott (born 29 July 1963) is a British Labour Party politician, who was first elected Member of Parliament (MP) for Sunderland Central in 2010. Elliott served as Shadow Minister for Energy and Climate Change from October 2013 to Sept ...

since 2017 and Sharon Hodgson.

Geography

Much of the city is located on a low range of hills running parallel to the coast. On average, it is around 80 metres

Much of the city is located on a low range of hills running parallel to the coast. On average, it is around 80 metres above sea level

Height above mean sea level is a measure of the vertical distance ( height, elevation or altitude) of a location in reference to a historic mean sea level taken as a vertical datum. In geodesy, it is formalized as '' orthometric heights''.

Th ...

. Sunderland is divided by the River Wear which passes through the middle of the city in a deeply incised valley, part of which is known as the Hylton gorge. Several smaller bodies of water, such as Hendon Burn

Hendon Burn is a stream flowing through Sunderland, Tyne and Wear. serving as a drainage basin for most of the city's southern half, its route proceeds from Doxford Park through the Farringdon Country Park area and into Gilley Law, Silkswo ...

and the Barnes Burn, run through the suburbs. The three road bridges connecting the north and south portions of the city are the Queen Alexandra Bridge

The Queen Alexandra Bridge is a road traffic, pedestrian and former railway bridge spanning the River Wear in North East England, linking the Deptford and Southwick areas of Sunderland. The steel truss bridge was designed by Charles A. Har ...

at Pallion, the Wearmouth Bridge just to the north of the city centre and most recently the Northern Spire Bridge between Castletown and Pallion. To the west of the city, the Hylton Viaduct

Hylton Viaduct is a road traffic and pedestrian bridge spanning the River Wear in North East England, linking North Hylton and South Hylton in Sunderland as the A19 road. The steel box girder bridge

A box girder bridge, or box secti ...

carries the A19 dual-carriageway over the Wear (see map below).

The city possesses a number of public parks. Several of these are historic, including Mowbray Park, Roker Park and Barnes Park

Barnes Park is a historic public park in Sunderland, Tyne and Wear, England. Taken together with its post-war extensions, which run to the former county borough boundary, it is the largest park in the city.

History

Barnes Park was laid out in ...

. In the early 2000s, Herrington Country Park

Herrington Country Park is a country park and open public space in Sunderland, Tyne and Wear. Located adjacent to Penshaw Monument, the park was built on the site of a former colliery. The park has developed into a significant home for wildlife, ...

was opened opposite Penshaw Monument. The city's parks have secured several awards for its commitment to preserving natural facilities, receiving the Britain in Bloom collective in 1993, 1997 and 2000.

Most of the suburbs of Sunderland are situated towards the west of the city centre with 70% of its population living on the south side of the river and 30% on the north side. The city extends to the seafront at Hendon and Ryhope in the south and Seaburn in the north.

Size

In the 2011 census, there were three definitions of Sunderland. The built-up area subdivision follows the boundaries of what is considered Sunderland itself; the built-up area, is also known as Wearside, includingChester-le-Street

Chester-le-Street (), also known as Chester, is a market town and civil parish in County Durham, England, around north of Durham and also close to Sunderland and Newcastle upon Tyne. It is located on the River Wear, which runs out to sea ...

and third is the council area which is similar in size to Wearside, without Chester-le-Street. The latter two include other surrounding towns and villages, the most notable being the town of Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered o ...

.

Green belt

The city is bounded by the Tyne & Wear Green Belt, with its portion in much of its surrounding rural area of the borough. It is a part of the local development plan, of which its stated aims are as follows: In the Sunderland borough boundary, as well as the aforementioned areas, landscape features and facilities such as much of the River Don and Wear basins, the George Washington Hotel Golf and Spa complex, Sharpley Golf Course, Herrington Country Park, Houghton Quarry and Penshaw Hill are within the green belt area.Climate

Sunderland has a temperateoceanic climate

An oceanic climate, also known as a marine climate, is the humid temperate climate sub-type in Köppen classification ''Cfb'', typical of west coasts in higher middle latitudes of continents, generally featuring cool summers and mild winters ...

( Köppen: ''Cfb''). Its location in the rain shadow

A rain shadow is an area of significantly reduced rainfall behind a mountainous region, on the side facing away from prevailing winds, known as its leeward side.

Evaporated moisture from water bodies (such as oceans and large lakes) is ca ...

of the Pennines

The Pennines (), also known as the Pennine Chain or Pennine Hills, are a range of uplands running between three regions of Northern England: North West England on the west, North East England and Yorkshire and the Humber on the east. Common ...

, as well as other mountain ranges to the west, such as those of the Lake District

The Lake District, also known as the Lakes or Lakeland, is a mountainous region in North West England. A popular holiday destination, it is famous for its lakes, forests, and mountains (or '' fells''), and its associations with William Wordswor ...

and southwestern Scotland, make Sunderland one of the least rainy cities of Northern England. The climate is heavily moderated by the adjacent North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian ...

, giving it cool summers, and winters that are mild considering its latitude. The closest weather station is in Tynemouth, about north of Sunderland. As a result, Sunderland's coastline is likely slightly milder given the more southerly position. Another relatively nearby weather station in Durham has warmer summer days and colder winter nights courtesy of its inland position.

Demography

At 3,874hectares

The hectare (; SI symbol: ha) is a non-SI metric unit of area equal to a square with 100- metre sides (1 hm2), or 10,000 m2, and is primarily used in the measurement of land. There are 100 hectares in one square kilometre. An acre is ...

, Sunderland is the 45th largest urban area in England by measure of area, with a population density of 45.88 people per hectare.

According to statistics based on the 2001 census, 60% of homes in the Sunderland metropolitan area

A metropolitan area or metro is a region that consists of a densely populated urban agglomeration and its surrounding territories sharing industries, commercial areas, transport network, infrastructures and housing. A metro area usually ...

are owner occupied, with an average household size of 2.4 people. Three percent of the homes have no permanent residents.

The most ethnically diverse ward of the city was the (now defunct) Thornholme area which had a population of 10,214 in 2001. This ward, which included Eden Vale, Thornhill, as well as parts of Hendon, Ashbrooke and the city centre, has long been the focus of Wearside's Bangladeshi community. In Thornholme, 89.4% are white (86.3% White British), 7.8% are Asian and 1.3% are mixed-race. Today, the Barnes ward, which contains part of former Thornholme ward, has the highest percentage (5.4%) of Bangladeshi residents in the city, with people of this ethnicity being the ward's only significant ethnic minority. The 2001 census also recorded a substantial concentration of Greek nationals, living mainly in Central and Thornholme wards. The least ethnically diverse wards are in the north of the city. The area of Castletown is made up of 99.3% white, 0.4% Asian and 0.2% mixed-race.

The Sunderland USD had a population of 174,286 in 2011 compared with 275,506 for the wider city. Both of these figures are a decrease compared with 2001 figures that showed the Sunderland USD had a population of 182,758 compared with 280,807 for the wider city.

In 2011, the Millfield ward, which contains the western half of the city centre, was the most ethnically diverse ward in Sunderland. Millfield is a multiracial area with large Indian and Bangladeshi communities, being the centre of Wearside's Bangladeshi community along with neighbouring Barnes. The ward's ethnicity was, in 2011, 76.4% White (73.5% White British), 17.6% Asian and 2.5% Black. Other wards with high ethnic minority populations include Hendon

Hendon is an urban area in the Borough of Barnet, North-West London northwest of Charing Cross. Hendon was an ancient manor and parish in the county of Middlesex and a former borough, the Municipal Borough of Hendon; it has been part of Gre ...

, Barnes, St Michael's and St Peter's. In 2011, the least ethnically diverse ward was the Northside suburb Redhill which was 99.0% White (98.3% White British), 0.3% Asian and 0.1% Black.

Here is a table comparing Sunderland and the wider City of Sunderland Metropolitan Borough as well as North East England

North East England is one of nine official regions of England at the first level of ITL for statistical purposes. The region has three current administrative levels below the region level in the region; combined authority, unitary author ...

.

The Sunderland Urban Subdivision is made up of all the wards listed on the table on the right hand side. In the Sunderland Urban Subdivision, 6.6% of the population were from an ethnic minority group (non white British) compared with 5.2% in the surrounding borough. Sunderland is less ethnically diverse than Gateshead

Gateshead () is a large town in northern England. It is on the River Tyne's southern bank, opposite Newcastle to which it is joined by seven bridges. The town contains the Millennium Bridge, The Sage, and the Baltic Centre for Contemporary ...

and South Shields

South Shields () is a coastal town in South Tyneside, Tyne and Wear, England. It is on the south bank of the mouth of the River Tyne. Historically, it was known in Roman times as Arbeia, and as Caer Urfa by Early Middle Ages. According to the 20 ...