Suicide Of Adolf Hitler on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Hitler retreated to his ''

Hitler retreated to his ''

report originating from

After some time, Hitler's valet,

After some time, Hitler's valet,

General Hans Krebs met Soviet General

General Hans Krebs met Soviet General

File:Bundesarchiv Bild 146-1978-086-03, Joseph Goebbels mit Familie.jpg,

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

, chancellor

Chancellor ( la, cancellarius) is a title of various official positions in the governments of many nations. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the or lattice work screens of a basilica or law cou ...

and dictator of Germany from 1933 to 1945, died by suicide

Suicide is the act of intentionally causing one's own death. Mental disorders (including depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, personality disorders, anxiety disorders), physical disorders (such as chronic fatigue syndrome), and s ...

via gunshot on 30 April 1945 in the in Berlin after it became clear that Germany would lose the Battle of Berlin

The Battle of Berlin, designated as the Berlin Strategic Offensive Operation by the Soviet Union, and also known as the Fall of Berlin, was one of the last major offensives of the European theatre of World War II.

After the Vistula– ...

, which led to the end of World War II in Europe

The European theatre of World War II was one of the two main theatres of combat during World War II. It saw heavy fighting across Europe for almost six years, starting with Germany's invasion of Poland on 1 September 1939 and ending with the ...

. Eva Braun

Eva Anna Paula Hitler (; 6 February 1912 – 30 April 1945) was a German photographer who was the longtime companion and briefly the wife of Adolf Hitler. Braun met Hitler in Munich when she was a 17-year-old assistant and model for his ...

, his wife of one day, also died by suicide, taking cyanide

Cyanide is a naturally occurring, rapidly acting, toxic chemical that can exist in many different forms.

In chemistry, a cyanide () is a chemical compound that contains a functional group. This group, known as the cyano group, consists of ...

. In accordance with Hitler's prior written and verbal instructions, that afternoon their remains were carried up the stairs and through the bunker's emergency exit to the Reich Chancellery

The Reich Chancellery (german: Reichskanzlei) was the traditional name of the office of the Chancellor of Germany (then called ''Reichskanzler'') in the period of the German Reich from 1878 to 1945. The Chancellery's seat, selected and prepared s ...

garden, where they were doused in petrol

Gasoline (; ) or petrol (; ) (see ) is a transparent, petroleum-derived flammable liquid that is used primarily as a fuel in most spark-ignited internal combustion engines (also known as petrol engines). It consists mostly of organic co ...

and burned. The news of Hitler's death was announced on German radio the next day, 1 May.

Eyewitnesses who saw Hitler's body immediately after his suicide testified that he died from a self-inflicted gunshot, which has been established to have been a shot to the temple

A temple (from the Latin ) is a building reserved for spiritual rituals and activities such as prayer and sacrifice. Religions which erect temples include Christianity (whose temples are typically called churches), Hinduism (whose temples ...

. Otto Günsche

__NOTOC__

Otto Günsche (24 September 1917 – 2 October 2003) was a mid-ranking officer in the Waffen-SS of Nazi Germany during World War II. He was a member of the SS Division Leibstandarte before he became Adolf Hitler's personal adjutant. G� ...

, Hitler's personal adjutant, who handled both bodies, testified that while Braun's smelled strongly of burnt almondsan indication of cyanide poisoningthere was no such odour about Hitler's body, which smelled of gunpowder. Dental remains extracted from the soil in the garden were matched with Hitler's dental records in May 1945. The dental remains were later confirmed as being Hitler's.

The Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

restricted the release of information and released many conflicting reports about Hitler's death. Historians have largely rejected these as part of a deliberate disinformation

Disinformation is false information deliberately spread to deceive people. It is sometimes confused with misinformation, which is false information but is not deliberate.

The English word ''disinformation'' comes from the application of the L ...

campaign by Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secreta ...

to sow confusion regarding Hitler's death, or have attempted to reconcile them. Soviet records allege that the burnt remains of Hitler and Braun were recovered, despite eyewitness accounts that they were almost completely reduced to ashes. In June 1945, the Soviets began seeding two contradictory narratives: that Hitler died by taking cyanide and that he had survived and fled to another country. Following extensive review, West Germany

West Germany is the colloquial term used to indicate the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG; german: Bundesrepublik Deutschland , BRD) between its formation on 23 May 1949 and the German reunification through the accession of East Germany on 3 O ...

issued a death certificate

A death certificate is either a legal document issued by a medical practitioner which states when a person died, or a document issued by a government civil registration office, that declares the date, location and cause of a person's death, as ...

in 1956. Conspiracy theories about Hitler's death continue to attract interest.

Preceding events

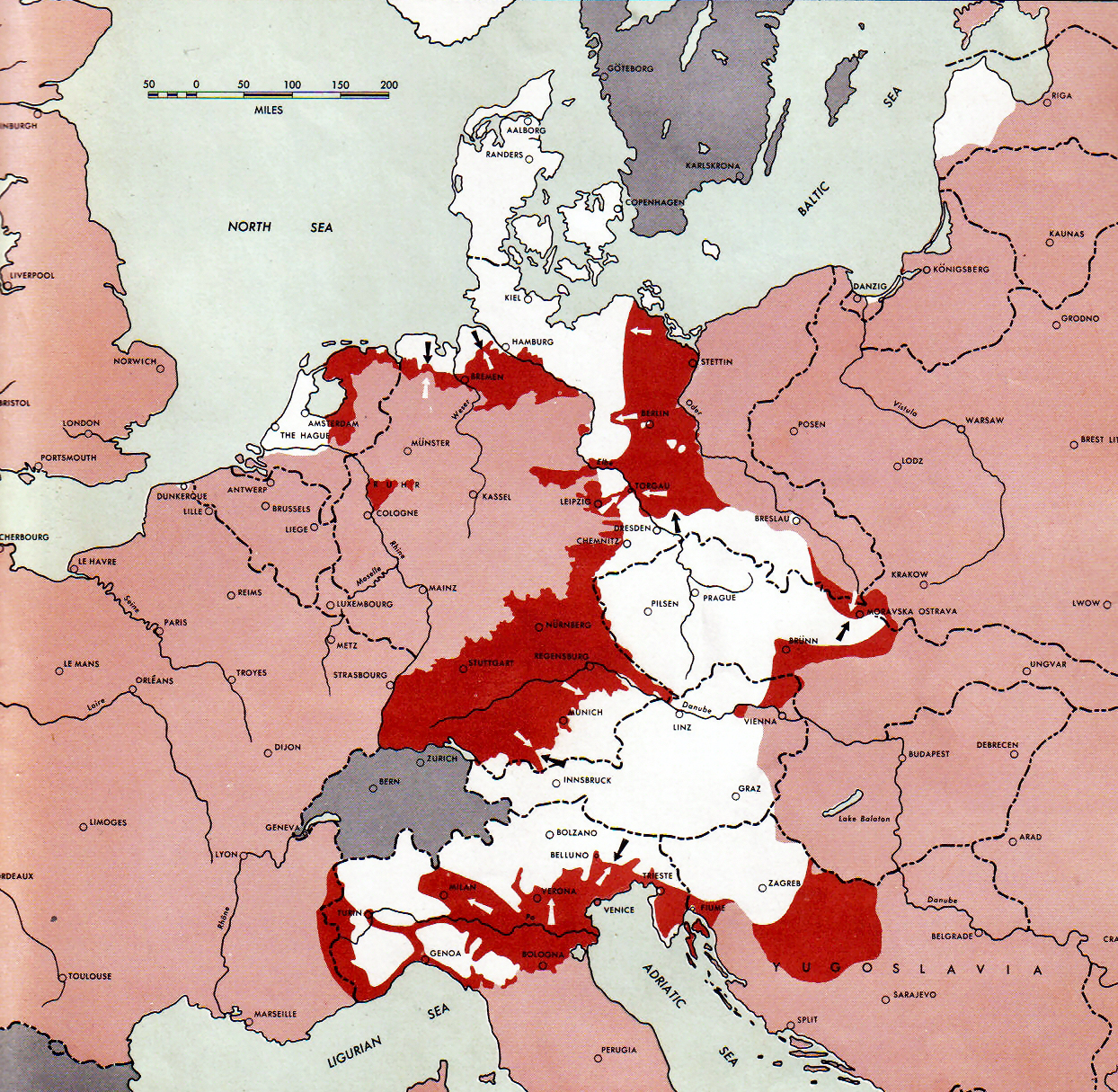

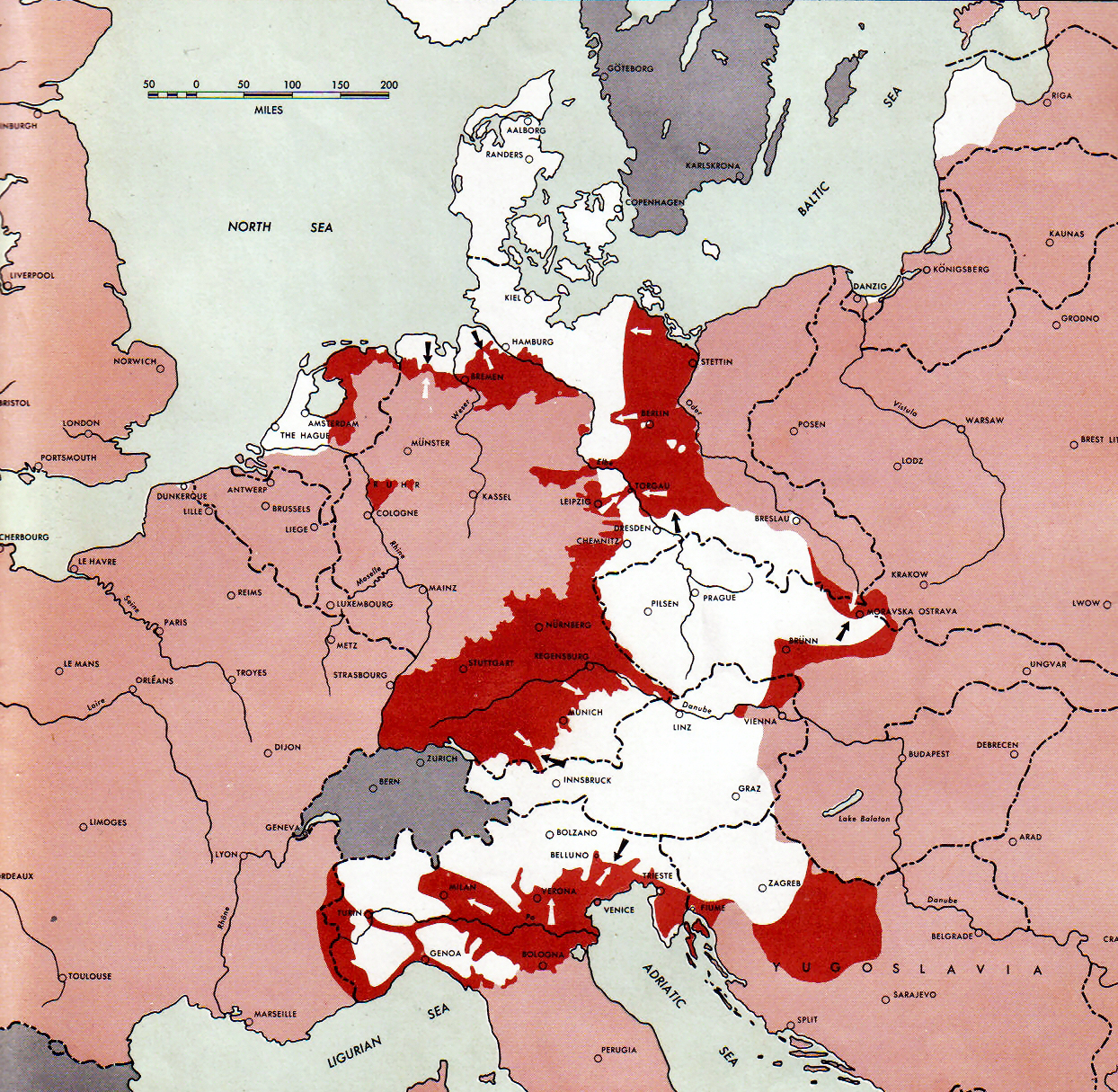

By early 1945,Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

was on the verge of total military collapse. Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populous ...

had fallen to the advancing Soviet Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, after ...

, which was preparing to cross the Oder

The Oder ( , ; Czech, Lower Sorbian and ; ) is a river in Central Europe. It is Poland's second-longest river in total length and third-longest within its borders after the Vistula and Warta. The Oder rises in the Czech Republic and flows thr ...

between Küstrin and Frankfurt-an-der-Oder

Frankfurt (Oder), also known as Frankfurt an der Oder (), is a city in the German state of Brandenburg. It has around 57,000 inhabitants, is one of the easternmost cities in Germany, the fourth-largest city in Brandenburg, and the largest German ...

with the objective of capturing Berlin to the west. German forces had recently lost to the Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

in the Ardennes Offensive

The Battle of the Bulge, also known as the Ardennes Offensive, was the last major German offensive campaign on the Western Front during World War II. The battle lasted from 16 December 1944 to 28 January 1945, towards the end of the war in ...

, with British and Canadian forces crossing the Rhine

), Surselva, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source1_coordinates=

, source1_elevation =

, source2 = Rein Posteriur/Hinterrhein

, source2_location = Paradies Glacier, Graubünden, Switzerland

, source2_coordinates=

, so ...

into the German industrial heartland of the Ruhr

The Ruhr ( ; german: Ruhrgebiet , also ''Ruhrpott'' ), also referred to as the Ruhr area, sometimes Ruhr district, Ruhr region, or Ruhr valley, is a polycentric urban area in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. With a population density of 2,800/km ...

. U.S. forces in the south had captured Lorraine

Lorraine , also , , ; Lorrain: ''Louréne''; Lorraine Franconian: ''Lottringe''; german: Lothringen ; lb, Loutrengen; nl, Lotharingen is a cultural and historical region in Northeastern France, now located in the administrative region of Gr ...

and were advancing towards Mainz

Mainz () is the capital and largest city of Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany.

Mainz is on the left bank of the Rhine, opposite to the place that the Main (river), Main joins the Rhine. Downstream of the confluence, the Rhine flows to the north-we ...

, Mannheim

Mannheim (; Palatine German: or ), officially the University City of Mannheim (german: Universitätsstadt Mannheim), is the second-largest city in the German state of Baden-Württemberg after the state capital of Stuttgart, and Germany's 2 ...

, and the Rhine. German forces in Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

were withdrawing north, as they were pressed by the U.S. and Commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. Historically, it has been synonymous with "republic". The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the ...

forces as part of the Spring Offensive to advance across the Po and into the foothills of the Alps.

Hitler retreated to his ''

Hitler retreated to his ''Führerbunker

The ''Führerbunker'' () was an air raid shelter located near the Reich Chancellery in Berlin, Germany. It was part of a subterranean bunker complex constructed in two phases in 1936 and 1944. It was the last of the Führer Headquarters ( ...

'' in Berlin on 16 January 1945. It was clear to the Nazi leadership that the battle for Berlin would be the final battle of the war in Europe. Some 325,000 soldiers of Germany's Army Group B were surrounded and captured in the Ruhr Pocket on 18 April, leaving the path open for U.S. forces to reach Berlin. By 11 April, the Americans crossed the Elbe

The Elbe (; cs, Labe ; nds, Ilv or ''Elv''; Upper and dsb, Łobjo) is one of the major rivers of Central Europe. It rises in the Giant Mountains of the northern Czech Republic before traversing much of Bohemia (western half of the Czech Repu ...

, to the west of the city. On 16 April, Soviet forces to the east crossed the Oder and commenced the battle for the Seelow Heights, the last major defensive line protecting Berlin on that side. By 19 April, the Germans were in full retreat from Seelow Heights, leaving no front line. Berlin was bombarded by Soviet artillery for the first time on 20 April, Hitler's birthday. By the evening of 21 April, Red Army tanks reached the outskirts of the city.

On 21 April, Hitler ordered a special detachment commanded by SS-General Felix Steiner

Felix Martin Julius Steiner (23 May 1896 – 12 May 1966) was a German SS commander during the Nazi era. During World War II, he served in the Waffen-SS, the combat branch of the SS, and commanded several SS divisions and corps. He was awarded t ...

to counterattack the Soviets. At the next day's afternoon situation conference, Hitler suffered a nervous collapse when he was informed that these orders had not been obeyed. He launched into a tirade against his generals, calling them treacherous and incompetent, culminating in a declarationfor the first timethat the war was lost. Hitler announced that he would stay in Berlin until the end and then shoot himself. Later that day, he asked SS physician Werner Haase

Werner Haase (2 August 1900 – 30 November 1950) was a professor of medicine and SS member during the Nazi era. He was one of Adolf Hitler's personal physicians. After the war ended, Haase was made a Soviet prisoner of war. He died while in ca ...

about the most reliable method of suicide. Haase suggested the "pistol-and-poison method" of combining a dose of cyanide

Cyanide is a naturally occurring, rapidly acting, toxic chemical that can exist in many different forms.

In chemistry, a cyanide () is a chemical compound that contains a functional group. This group, known as the cyano group, consists of ...

with a gunshot to the head. ''Luftwaffe

The ''Luftwaffe'' () was the aerial-warfare branch of the German ''Wehrmacht'' before and during World War II. Germany's military air arms during World War I, the ''Luftstreitkräfte'' of the Imperial Army and the '' Marine-Fliegerabtei ...

'' chief Hermann Göring

Hermann Wilhelm Göring (or Goering; ; 12 January 1893 – 15 October 1946) was a German politician, military leader and convicted war criminal. He was one of the most powerful figures in the Nazi Party, which ruled Germany from 1933 to 1 ...

learned about Hitler's admission of defeat and declaration of his intended suicide and sent a telegram to Hitler, asking for permission to take over the leadership of the Reich in accordance with Hitler's 1941 decree naming him as his successor. Hitler's secretary Martin Bormann

Martin Ludwig Bormann (17 June 1900 – 2 May 1945) was a German Nazi Party official and head of the Nazi Party Chancellery. He gained immense power by using his position as Adolf Hitler's private secretary to control the flow of information ...

convinced Hitler that the letter from Göring was an attempt to overthrow the dictator. In response, Hitler informed Göring that he would be executed unless he resigned all of his posts. Later that day, he sacked Göring from all of his offices and ordered his arrest. Hitler also ordered his chief aide and adjutant, Julius Schaub

Julius Schaub (20 August 1898 – 27 December 1967) was the chief aide and adjutant to German dictator Adolf Hitler until the dictator's suicide on 30 April 1945.

Born in 1898 in Munich, Bavaria, Schaub served as a field medic during World W ...

, to destroy safeguarded documents and his personal train.

By 27 April, Berlin's communication had been all but cut off from the rest of Germany. Secure radio contact with defending units had been lost; the command staff in the had to depend on telephone lines for passing instructions and orders, and on public radio for news and information. On 28 April, Hitler received a BBC #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC

Here i going to introduce about the best teacher of my life b BALAJI sir. He is the precious gift that I got befor 2yrs . How has helped and thought all the concept and made my success in the 10th board exam. ...

...Reuters

Reuters ( ) is a news agency owned by Thomson Reuters Corporation. It employs around 2,500 journalists and 600 photojournalists in about 200 locations worldwide. Reuters is one of the largest news agencies in the world.

The agency was estab ...

: it stated that Heinrich Himmler

Heinrich Luitpold Himmler (; 7 October 1900 – 23 May 1945) was of the (Protection Squadron; SS), and a leading member of the Nazi Party of Germany. Himmler was one of the most powerful men in Nazi Germany and a main architect of th ...

had offered to surrender to the Western Allies

The Allies, formally referred to as the United Nations from 1942, were an international military coalition formed during the Second World War (1939–1945) to oppose the Axis powers, led by Nazi Germany, Imperial Japan, and Fascist Italy ...

. The offer was declined. Himmler had implied to the Allies that he had the authority to negotiate a surrender, which Hitler considered to be treason. That afternoon, Hitler's anger and bitterness escalated into a rage against Himmler. He ordered Himmler's arrest and had Hermann Fegelein

Hans Otto Georg Hermann Fegelein (30 October 1906 – 28 April 1945) was a high-ranking commander in the Waffen-SS of Nazi Germany. He was a member of Adolf Hitler's entourage and brother-in-law to Eva Braun through his marriage to her si ...

(Himmler's SS representative at Hitler's headquarters) shot for desertion.

By this time, the Red Army had advanced to the Potsdamer Platz

Potsdamer Platz (, ''Potsdam Square'') is a public square and traffic intersection in the center of Berlin, Germany, lying about south of the Brandenburg Gate and the Reichstag (German Parliament Building), and close to the southeast corne ...

, and all indications were that they were preparing to storm the Reich Chancellery

The Reich Chancellery (german: Reichskanzlei) was the traditional name of the office of the Chancellor of Germany (then called ''Reichskanzler'') in the period of the German Reich from 1878 to 1945. The Chancellery's seat, selected and prepared s ...

. This report and Himmler's treachery prompted Hitler to make the last decisions of his life. Shortly after midnight on 29 April, he married Eva Braun

Eva Anna Paula Hitler (; 6 February 1912 – 30 April 1945) was a German photographer who was the longtime companion and briefly the wife of Adolf Hitler. Braun met Hitler in Munich when she was a 17-year-old assistant and model for his ...

in a small civil ceremony in a map room within the . The two then hosted a modest wedding breakfast, after which Hitler took secretary Traudl Junge

Gertraud "Traudl" Junge (; 16 March 1920 – 10 February 2002) was a German editor who worked as Adolf Hitler's last private secretary from December 1942 to April 1945. After typing Hitler's will, she remained in the Berlin ''Führerbunker'' unt ...

to another room and dictated his last will and testament. It left instructions to be carried out immediately following his death, with Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz

Karl Dönitz (sometimes spelled Doenitz; ; 16 September 1891 24 December 1980) was a German admiral who briefly succeeded Adolf Hitler as head of state in May 1945, holding the position until the dissolution of the Flensburg Government follo ...

and Joseph Goebbels

Paul Joseph Goebbels (; 29 October 1897 – 1 May 1945) was a German Nazi politician who was the ''Gauleiter'' (district leader) of Berlin, chief propagandist for the Nazi Party, and then Reich Minister of Propaganda from 1933 to 19 ...

assuming Hitler's roles as head of state

A head of state (or chief of state) is the public persona who officially embodies a state Foakes, pp. 110–11 " he head of statebeing an embodiment of the State itself or representatitve of its international persona." in its unity and l ...

and chancellor

Chancellor ( la, cancellarius) is a title of various official positions in the governments of many nations. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the or lattice work screens of a basilica or law cou ...

, respectively. Hitler signed these documents at 04:00 and then went to bed. Some sources say that he dictated the last will and testament immediately before the wedding, but all agree on the timing of the signing.

On the afternoon of 29 April, Hitler learned that his ally, Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in 194 ...

, had been executed by Italian partisans. The bodies of Mussolini and his mistress, Clara Petacci

Clara Petacci, known as Claretta Petacci (; 28 February 1912 – 28 April 1945), was a mistress of the Italian dictator Benito Mussolini. She was killed during Mussolini's execution by Italian partisans.

Early life

Daughter of Giuseppina Persich ...

, had been strung up by their heels. The corpses were later cut down and thrown into the gutter, where they were mocked by Italian dissidents. These events may have strengthened Hitler's resolve not to allow himself or his wife to be made a "spectacle" of, as he had earlier recorded in his testament. Hitler had been given some capsules of prussic acid

Hydrogen cyanide, sometimes called prussic acid, is a chemical compound with the formula HCN and structure . It is a colorless, extremely poisonous, and flammable liquid that boils slightly above room temperature, at . HCN is produced on an in ...

by Himmler through SS physician Dr Ludwig Stumpfegger

Ludwig Stumpfegger (11 July 1910 – 2 May 1945) was a German doctor who served in the SS of Nazi Germany during World War II. He was Adolf Hitler's personal surgeon from 1944 to 1945, and was present in the ''Führerbunker'' in Berlin in late ...

, and initially had intended to use them for his suicide. But when he received the news that Himmler had contacted the Allies through a Swedish diplomat to arrange for an end to the war, Hitler was outraged. With this betrayal in his mind, Hitler began to doubt whether the ampoules would be effective. He ordered Haase to test one on his dog Blondi

Blondi (1941 – 29 April 1945) was Adolf Hitler's German Shepherd, a gift as a puppy from Martin Bormann in 1941. Hitler kept Blondi even after his move into the '' Führerbunker'' located underneath the garden of the Reich Chancellery on 16 ...

. The capsule workedthe dog died instantly.

Suicide

Hitler and Braun lived together as husband and wife in the bunker for less than 40 hours. By 01:00 on 30 April, Field MarshalWilhelm Keitel

Wilhelm Bodewin Johann Gustav Keitel (; 22 September 188216 October 1946) was a German field marshal and war criminal who held office as chief of the '' Oberkommando der Wehrmacht'' (OKW), the high command of Nazi Germany's Armed Forces, duri ...

had reported that all of the forces on which Hitler had been depending to rescue Berlin had either been encircled or forced onto the defensive. At around 02:30, Hitler appeared in the corridor where about twenty people, mostly women, were assembled to give their farewells. He went down the line, shaking hands and speaking with each of them, before retiring to his quarters. Late in the morning, with the Soviets less than from the ''Führerbunker'', Hitler had a meeting with General Helmuth Weidling

Helmuth Otto Ludwig Weidling (2 November 1891 – 17 November 1955) was a German general during World War II. He was the last commander of the Berlin Defence Area during the Battle of Berlin, and led the defence of the city against Soviet forc ...

, the commander of the Berlin Defence Area. Weidling told Hitler that the garrison would probably run out of ammunition that night, and that the fighting in Berlin would inevitably come to an end within the next 24 hours. Weidling asked for permission for a break-out; this was a request he had unsuccessfully made before. Hitler did not answer, and Weidling went back to his headquarters in the Bendlerblock

The Bendlerblock is a building complex in the Tiergarten district of Berlin, Germany, located on Stauffenbergstraße (formerly named ''Bendlerstraße''). Erected in 1914 as headquarters of several Imperial German Navy (''Kaiserliche Marine'') off ...

. At about 13:00, he received Hitler's permission to attempt a break-out that night. Hitler, two secretaries, and his personal cook then had lunch, after which Hitler and Braun said goodbye to members of the bunker staff and fellow occupants, including Bormann, Goebbels, the secretaries, and several military officers. At around 14:30 Adolf and Eva Hitler went into his personal study. Hitler's adjutant SS-''Sturmbannführer

__NOTOC__

''Sturmbannführer'' (; ) was a Nazi Party paramilitary rank equivalent to major that was used in several Nazi organizations, such as the SA, SS, and the NSFK. The rank originated from German shock troop units of the First World War ...

'' Otto Günsche

__NOTOC__

Otto Günsche (24 September 1917 – 2 October 2003) was a mid-ranking officer in the Waffen-SS of Nazi Germany during World War II. He was a member of the SS Division Leibstandarte before he became Adolf Hitler's personal adjutant. G� ...

stood guard outside the study door.

After some time, Hitler's valet,

After some time, Hitler's valet, Heinz Linge

Heinz Linge (23 March 1913 – 9 March 1980) was a German SS officer who served as a valet for the leader of Nazi Germany, Adolf Hitler, and became known for his close personal proximity to historical events. Linge was present in the ''Füh ...

, entered the antechamber to Hitler's quarters, where he discovered the door closed and could smell gunpowder smoke. Linge went back out to the corridor where Bormann was standing, and the two then entered the study together. Linge later stated that while in the room he immediately noted a scent of burnt almonds, which is a common observation in the presence of hydrogen cyanide

Hydrogen cyanide, sometimes called prussic acid, is a chemical compound with the formula HCN and structure . It is a colorless, extremely poisonous, and flammable liquid that boils slightly above room temperature, at . HCN is produced on an ...

. Linge saw the bodies of Hitler and Braun sitting upright on the sofa, with Hitler to Braun's right. His head was canted to his right. Günsche entered the study shortly afterwards. He described Braun's corpse as being on Hitler's left, with her legs drawn up and slumped away from him. Günsche stated that Hitler "sat ... sunken over, with blood dripping out of his right temple. He had shot himself with his own pistol, a Walther PPK

The Walther PP (german: Polizeipistole, or police pistol) series pistols are blowback-operated semi-automatic pistols, developed by the German arms manufacturer Carl Walther GmbH Sportwaffen.

It features an exposed hammer, a traditional double-ac ...

7.65." The gun lay at his feet. Hitler's dripping blood had made a large stain on the right arm of the sofa and was pooling on the rug. According to Linge, Braun's body had no visible wounds, and her face showed how she had diedfrom cyanide poisoning

Cyanide poisoning is poisoning that results from exposure to any of a number of forms of cyanide. Early symptoms include headache, dizziness, fast heart rate, shortness of breath, and vomiting. This phase may then be followed by seizures, slow h ...

. Günsche and SS- Wilhelm Mohnke

Wilhelm Mohnke (15 March 1911 – 6 August 2001) was one of the original members of the SS-Staff Guard (''Stabswache'') "Berlin" formed in March 1933. From those ranks, Mohnke rose to become one of Adolf Hitler's last remaining generals. He joi ...

stated "unequivocally" that all outsiders and those performing duties and work in the bunker "did not have any access" to Hitler's private living quarters during the time of death (between 15:00 and 16:00).

Günsche left the study and announced that Hitler was dead to a group in the briefing room, which included Goebbels, Krebs, and General Wilhelm Burgdorf

Wilhelm Emanuel Burgdorf (15 February 1895 – 2 May 1945) was a German general during World War II, who served as a commander and staff officer in the German Army. In October 1944, Burgdorf assumed the role of the chief of the Army Personnel O ...

. These three, in addition to others including Hitler Youth

The Hitler Youth (german: Hitlerjugend , often abbreviated as HJ, ) was the youth organisation of the Nazi Party in Germany. Its origins date back to 1922 and it received the name ("Hitler Youth, League of German Worker Youth") in July 1926. ...

leader Artur Axmann

Artur Axmann (18 February 1913 – 24 October 1996) was the German Nazi national leader (''Reichsjugendführer'') of the Hitler Youth (''Hitlerjugend'') from 1940 to 1945, when the war ended. He was the last living Nazi with a rank equivalent to ...

, viewed the bodies. Linge and another man rolled up Hitler's body in a rug, and then, in accordance with Hitler's prior written and verbal instructions, his and Braun's bodies were carried up the stairs and through the bunker's emergency exit to the garden behind the Reich Chancellery, where they were to be burned with petrol

Gasoline (; ) or petrol (; ) (see ) is a transparent, petroleum-derived flammable liquid that is used primarily as a fuel in most spark-ignited internal combustion engines (also known as petrol engines). It consists mostly of organic co ...

. Although Hitler's corpse was partially covered by the rug, numerous witnesses testified to recognising him, as the top of his head was not covered, nor were his lower legs and feet.

The bunker telephone operator SS- Rochus Misch

Rochus Misch (29 July 1917 – 5 September 2013) was a German ''Oberscharführer'' (sergeant) in the 1st SS Panzer Division Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler (LSSAH). He was badly wounded during the Polish campaign during the first month of World ...

reported Hitler's death to (Führer Escort Command) chief Franz Schädle

Franz Schädle (19 November 1906 – 2 May 1945) was the last commander of Adolf Hitler's personal bodyguard (the '' Führerbegleitkommando''; FBK), from 5 January 1945 until his death on 2 May 1945.

Biography

Schädle was born in Westernh ...

and returned to the switchboard, later recalling someone shouting that Hitler's body was being burned. After the first attempts to ignite the petrol did not work, Linge went back inside the bunker and returned with a thick roll of papers. Bormann lit the papers and threw them onto the bodies. As the two corpses caught fire, a group including Bormann, Günsche, Linge, Goebbels, Erich Kempka

Erich Kempka (16 September 1910 – 24 January 1975) was a member of the SS in Nazi Germany who served as Adolf Hitler's primary chauffeur from 1936 to April 1945. He was present in the area of the Reich Chancellery on 30 April 1945, when ...

, Peter Högl

Peter Högl (19 August 1897 – 2 May 1945) was a German people, German officer holding the rank of SS-''Obersturmbannführer'' (lieutenant colonel) who was a member of one of Adolf Hitler's bodyguard units. He spent time in the ''Führerbunker'' ...

, Ewald Lindloff

Ewald Lindloff (27 September 1908 – 2 May 1945) was a Waffen-SS officer during World War II, who was present in the '' Führerbunker'' on 30 April 1945, when Hitler committed suicide. He was placed in charge of disposing of Hitler's remains. ...

, and Hans Reisser raised their arms in salute as they stood just inside the bunker doorway.

At around 16:15, Linge ordered SS- Heinz Krüger and SS- Werner Schwiedel to roll up the rug in Hitler's study to burn it. Schwiedel later stated that upon entering the study, he saw a pool of blood the size of a "large dinner plate" by the arm-rest of the sofa. Noticing a spent cartridge case, he bent down and picked it up from where it lay on the rug about 1 mm from a 7.65 pistol. The two men removed the blood-stained rug and carried it up the stairs and outside to the Chancellery garden, where it was placed on the ground and burned.

The Red Army shelled the area in and around the Reich Chancellery on and off during the afternoon. SS guards brought over additional cans of petrol to further burn the corpses. Although the corpses were being burned in the open, where the distribution of heat varies (as opposed to in a crematorium

A crematorium or crematory is a venue for the cremation of the dead. Modern crematoria contain at least one cremator (also known as a crematory, retort or cremation chamber), a purpose-built furnace. In some countries a crematorium can also be ...

), according to eyewitnesses, the copious amount of fuel applied from about 16:00 to 18:30 reduced the remains to something between charred Charring is a chemical process of incomplete combustion of certain solids when subjected to high heat. Heat distillation removes water vapour and volatile organic compounds ( syngas) from the matrix. The residual black carbon material is char, as d ...

bones and piles of ashes which fell apart to the touch. At approximately 18:30, Lindloff (and perhaps Reisser) covered up the ashen remains in a shallow bomb crater. The shelling and a fire from napalm

Napalm is an incendiary mixture of a gelling agent and a volatile petrochemical (usually gasoline (petrol) or diesel fuel). The name is a portmanteau of two of the constituents of the original thickening and gelling agents: coprecipitated al ...

incendiary bombs continued until 2 May. During this period it was difficult to spend any time in the garden because of the continuous shelling.

Aftermath

General Hans Krebs met Soviet General

General Hans Krebs met Soviet General Vasily Chuikov

Vasily Ivanovich Chuikov (russian: link=no, Васи́лий Ива́нович Чуйко́в; ; – 18 March 1982) was a Soviet military commander and Marshal of the Soviet Union. He is best known for commanding the 62nd Army which saw h ...

just prior to 04:00 on 1 May, giving him the news of Hitler's death, while attempting to negotiate a ceasefire and open "peace negotiations". Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secreta ...

was informed of Hitler's suicide around 04:05 Berlin time, thirteen hours after the event. He demanded unconditional surrender

An unconditional surrender is a surrender in which no guarantees are given to the surrendering party. It is often demanded with the threat of complete destruction, extermination or annihilation.

In modern times, unconditional surrenders most ofte ...

, which Krebs lacked authorisation to give. Stalin wanted confirmation that Hitler was dead and ordered the Red Army's counterespionage unit, SMERSH

SMERSH (russian: СМЕРШ) was an umbrella organization for three independent counter-intelligence agencies in the Red Army formed in late 1942 or even earlier, but officially announced only on 14 April 1943. The name SMERSH was coined by Josep ...

, to find his corpse.

The first inkling to the outside world that Hitler was dead came from the Germans themselves. On the night of 1 May, the radio station interrupted their normal program to announce that Hitler had died that afternoon, and introduced his successor, President Karl Dönitz. Dönitz called upon the German people to mourn their Führer, whom he stated had died a hero defending the capital of the Reich. Hoping to save the army and the nation by negotiating a partial surrender to the British and Americans, Dönitz authorised a fighting withdrawal to the west. His tactic was somewhat successful: it enabled about 1.8 million German soldiers to avoid capture by the Soviets, but came at a high cost in bloodshed, as troops continued to fight until 8 May.

In the early morning hours of 2 May, the Soviets captured the Reich Chancellery. Inside the , Generals Krebs and Burgdorf shot themselves in the head. In early May, Hitler's and Braun's dental remains were extracted from the soil. Stalin was wary of believing Hitler was dead and restricted the release of information to the public. By 11 May, dental assistant Käthe Heusermann and dental technician Fritz Echtmann, both of whom had worked for Hitler's dentist Hugo Blaschke

Hugo Johannes Blaschke (14 November 1881 – 6 December 1959) was a German dental surgeon notable for being Adolf Hitler's personal dentist from 1933 to April 1945 and for being the chief dentist on the staff of ''Reichsführer-SS'' Heinrich Himm ...

, identified the dental remains of Hitler and Braun. Both would spend years in Soviet prisons. An alleged Soviet autopsy of Hitler made public in 1968 was used by forensic odontologists Reidar F. Sognnaes Reidar Sognnaes (November 6, 1911 – September 21, 1984) was Dean of the Harvard School of Dental Medicine, founding Dean of the UCLA School of Dentistry and scholar in the field of oral pathology.

Biography

Reidar Fauske Sognnaes was born in Ber ...

and Ferdinand Strøm to confirm the authenticity of Hitler's dental remains in 1972. In 2017, French forensic pathologist

Forensic pathology is pathology that focuses on determining the cause of death by examining a corpse. A post mortem examination is performed by a medical examiner or forensic pathologist, usually during the investigation of criminal law cases an ...

Philippe Charlier

Philippe Charlier is a French coroner, forensic pathologist and paleopathologist.

Biography

Charlier was born in Meaux on 25 June 1977. His father is a doctor, his mother a pharmacist. He made his first dig at the age of 10, when he found a hu ...

also found the dental remains in the Soviet archives, including teeth on part of a jawbone, to be in "perfect agreement" with X-rays taken of Hitler in 1944. Charlier used electron microscopy

An electron microscope is a microscope that uses a beam of accelerated electrons as a source of illumination. As the wavelength of an electron can be up to 100,000 times shorter than that of visible light photons, electron microscopes have a hi ...

to examine the tartar, which contained only plant fibres, a detail consistent with Hitler's vegetarianism

Near the end of his life, Adolf Hitler (1889–1945) followed a vegetarian diet. It is not clear when or why he adopted it, since some accounts of his dietary habits prior to the Second World War indicate that he consumed meat as late as 1937. In ...

. A 2018 paper co-authored by Charlier concludes that these remains "cannot be a fake", citing their significant wear. No gunpowder residue was detected, indicating that Hitler did not die by a gunshot wound through the mouth.

In early June 1945, SMERSH moved the remains of several individuals, including the Goebbels family (Joseph, Magda

Magda is a feminine given name, sometimes a short form ( hypocorism) of names such as Magdalena, which may refer to:

* Magda Apanowicz (born 1985), Canadian actress

* Magda B. Arnold (1903–2002), Czechoslovakian-born American psychologist

* M ...

, and their children), from Buch

Buch (the German word for book or a modification of the German word '' Buche'' for beech) may refer to:

People

* Buch (surname), a list of people with the surname Buch Geography

;Germany:

*Buch am Wald, a town in the district of Ansbach, Bavaria

* ...

to Finow. Hitler and Braun's remains were alleged to have been moved as well, but this is most likely Soviet disinformation

Disinformation is false information deliberately spread to deceive people. It is sometimes confused with misinformation, which is false information but is not deliberate.

The English word ''disinformation'' comes from the application of the L ...

. There is no evidence that any bodily remains of Hitler or Braunwith the exception of the dental remainswere found by the Soviets. The remains of the Goebbels family and others were buried in a forest in Brandenburg

Brandenburg (; nds, Brannenborg; dsb, Bramborska ) is a states of Germany, state in the northeast of Germany bordering the states of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Lower Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, and Saxony, as well as the country of Poland. With an ar ...

on 3 June 1945, then exhumed and moved to SMERSH's new facility in Magdeburg

Magdeburg (; nds, label=Low Saxon, Meideborg ) is the capital and second-largest city of the German state Saxony-Anhalt. The city is situated at the Elbe river.

Otto I, the first Holy Roman Emperor and founder of the Archdiocese of Magdebur ...

, where they were in February 1946. By 1970, the facility was under KGB

The KGB (russian: links=no, lit=Committee for State Security, Комитет государственной безопасности (КГБ), a=ru-KGB.ogg, p=kəmʲɪˈtʲet ɡəsʊˈdarstvʲɪn(ː)əj bʲɪzɐˈpasnəsʲtʲɪ, Komitet gosud ...

control and scheduled to be relinquished to East Germany

East Germany, officially the German Democratic Republic (GDR; german: Deutsche Demokratische Republik, , DDR, ), was a country that existed from its creation on 7 October 1949 until its dissolution on 3 October 1990. In these years the state ...

. Concerned that a known Nazi burial site might become a neo-Nazi

Neo-Nazism comprises the post–World War II militant, social, and political movements that seek to revive and reinstate Nazism, Nazi ideology. Neo-Nazis employ their ideology to promote hatred and Supremacism#Racial, racial supremacy (ofte ...

shrine, KGB director Yuri Andropov

Yuri Vladimirovich Andropov (– 9 February 1984) was the sixth paramount leader of the Soviet Union and the fourth General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. After Leonid Brezhnev's 18-year rule, Andropov served in the po ...

authorised an operation to exhume and destroy the decaying remains. On 4 April 1970, a KGB team thoroughly cremated them and cast the ashes into the Biederitz river, a tributary of the nearby Elbe.

For politically motivated reasons, the Soviet Union presented various versions of Hitler's fate. On 5 June, the Soviets claimed that his body had been examined and that he had died by cyanide poisoning. At a press conference on 9 June, the Soviets said they had not actually identified the body and that Hitler had likely escaped. When asked in July 1945 how Hitler had died, Stalin said he was living "in Spain or Argentina". In November 1945, Dick White

Sir Dick Goldsmith White, (20 December 1906 – 21 February 1993) was a British intelligence officer. He was Director General (DG) of MI5 from 1953 to 1956, and Head of the Secret Intelligence Service (MI6) from 1956 to 1968.

Early life

Whit ...

, the head of counter-intelligence in the British sector of Berlin, had their agent Hugh Trevor-Roper

Hugh Redwald Trevor-Roper, Baron Dacre of Glanton (15 January 1914 – 26 January 2003) was an English historian. He was Regius Professor of Modern History at the University of Oxford.

Trevor-Roper was a polemicist and essayist on a range of ...

investigate. His report was expanded and published in 1947 as ''The Last Days of Hitler''. In the years immediately after the war, the Soviets maintained that Hitler was not dead, but had escaped and was either being shielded by the former Western Allies, was in Francoist Spain

Francoist Spain ( es, España franquista), or the Francoist dictatorship (), was the period of Spanish history between 1939 and 1975, when Francisco Franco ruled Spain after the Spanish Civil War with the title . After his death in 1975, Spai ...

, or was somewhere in South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the southe ...

.

Until the mid-1950s, the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic intelligence and security service of the United States and its principal federal law enforcement agency. Operating under the jurisdiction of the United States Department of Justice, ...

and Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, ...

received many leads claiming that Hitler might still be alive, while giving none of them credence. The documents remained classified until the early 2010s, as authorised by the 1998 Nazi War Crimes Disclosure Act

The Nazi War Crimes and Japanese Imperial Government Records Interagency Working Group is a United States government interagency group, which is tasked with locating, identifying, inventorying, and recommending for declassification classified U.S ...

. The secrecy in which the investigation was shrouded helped fuel conspiracy theories asserting Hitler's survival. Presiding judge at the Einsatzgruppen trial at Nuremberg Michael Musmanno

Michael Angelo Musmanno (April 7, 1897 – October 12, 1968) was an American jurist, politician, and naval officer. Coming from an immigrant family, he started to work as a coal loader at the age of 14. After serving in the United States Army in ...

considered all such claims contrary to the evidence.

Between 1948 and 1952, amid denazification

Denazification (german: link=yes, Entnazifizierung) was an Allied initiative to rid German and Austrian society, culture, press, economy, judiciary, and politics of the Nazi ideology following the Second World War. It was carried out by remov ...

proceedings in West Germany

West Germany is the colloquial term used to indicate the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG; german: Bundesrepublik Deutschland , BRD) between its formation on 23 May 1949 and the German reunification through the accession of East Germany on 3 O ...

, legal disputes over Hitler's former property (including '' The Art of Painting'' by Johannes Vermeer

Johannes Vermeer ( , , #Pronunciation of name, see below; also known as Jan Vermeer; October 1632 – 15 December 1675) was a Dutch Baroque Period Painting, painter who specialized in domestic interior scenes of middle class, middle-class life. ...

) were hindered by the lack of an official death declaration. Beginning in 1952, a federal court in Berchtesgaden

Berchtesgaden () is a municipality in the district Berchtesgadener Land, Bavaria, in southeastern Germany, near the border with Austria, south of Salzburg and southeast of Munich. It lies in the Berchtesgaden Alps, south of Berchtesgaden; the ...

interviewed 42 witnesses about Hitler's suicidebehind closed doors to avoid testimonies

''Testimonies'' is a 1952 novel, set in North Wales, by the English author Patrick O'Brian. It was first published in the UK under the title ''Three Bear Witness,'' and in the US as ''Testimonies''.

Although the book's first English reviews w ...

influencing one another. After four years of extensive review, Judge Heinrich Stephanus concluded: "There can no longer be the slightest doubt that on 30 April 1945 Adolf Hitler put an end to his life in the Chancellery by his own hand, by means of a shot into his right temple." A death certificate was issued on 25 February 1956, with an attached report of more than 1,500 pages. An 80-page expert criminological report was prepared in mid-1956, focusing on the "substantial discrepancies" between eyewitness testimonies and serving as a springboard for photographic reconstructions. Ballistic

Ballistics may refer to:

Science

* Ballistics, the science that deals with the motion, behavior, and effects of projectiles

** Forensic ballistics, the science of analyzing firearm usage in crimes

** Internal ballistics, the study of the proc ...

experiments were arranged to determine which interpretation of the fatal gunshot was most likely. The declaration became public and legally binding by the year's end. Hitler's demise was entered as an assumption of death on the basis that none of the witnesses had seen his body, which German historian Anton Joachimsthalerwho cites some of the testimonies in his book on the dictator's deathpoints out is incorrect. The federal court went on to publish a summary of its findings of fact in a 1958 press release.

Further Soviet investigations and disinformation

On 11 December 1945, the Soviets allowed a limited investigation of the bunker complex grounds by the other Allied powers (Britain, France, and the U.S.). Two representatives from each nation watched several Germans dig up soil down to the concrete roof of the bunker; the excavation included the bomb crater where Hitler's burnt remains had been buried. Found during the dig were two hats identified as Hitler's, an undergarment with Braun's initials, and some reports to Hitler from Goebbels. The Soviet People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (NKVD) barred further excavation on the accusation that the representatives had removed documents from the Reich Chancellery. At the end of 1945, Stalin ordered the NKVD to form a second commission to investigate Hitler's death. On 30 May 1946, agents of the NKVD's successor, theMinistry of Internal Affairs

An interior ministry (sometimes called a ministry of internal affairs or ministry of home affairs) is a government department that is responsible for internal affairs.

Lists of current ministries of internal affairs

Named "ministry"

* Ministry ...

(MVD), found part of a skull in the crater where Hitler's remains had been exhumed. The remnant consists of part of the occipital bone

The occipital bone () is a neurocranium, cranial dermal bone and the main bone of the occiput (back and lower part of the skull). It is trapezoidal in shape and curved on itself like a shallow dish. The occipital bone overlies the occipital lobe ...

and part of both parietal bone

The parietal bones () are two bones in the Human skull, skull which, when joined at a fibrous joint, form the sides and roof of the Human skull, cranium. In humans, each bone is roughly quadrilateral in form, and has two surfaces, four borders, an ...

s. The nearly complete left parietal bone has a bullet hole, apparently an exit wound. This remained uncatalogued until 1975, and was rediscovered in the Russian State Archives in 1993. In 2009, University of Connecticut

The University of Connecticut (UConn) is a public land-grant research university in Storrs, Connecticut, a village in the town of Mansfield. The primary 4,400-acre (17.8 km2) campus is in Storrs, approximately a half hour's drive from Hart ...

archaeologist and bone specialist Nick Bellantoni examined the skull fragment, which Soviet officials believed to be Hitler's. According to Bellantoni, "The bone seemed very thin" for a male, and "the sutures where the skull plates come together seemed to correspond to someone under 40". A small piece detached from the skull was DNA-tested, as was blood from Hitler's sofa. The skull was determined to be that of a woman, while the blood was confirmed to belong to a male.

On 29 December 1949, a secret dossier on Hitler was presented to Stalin, which was based upon the interrogation of Nazis who had been present in the , including Günsche and Linge. Western historians were allowed into the archives of the former Soviet Union beginning in 1991, but the dossier remained undiscovered for twelve years; in 2005, it was published as '' The Hitler Book''.

In 1968, Soviet journalist Lev Bezymenski published his book, ''The Death of Adolf Hitler

''The Death of Adolf Hitler: Unknown Documents from Soviet Archives'' (german: Der Tod des Adolf Hitler: Unbekannte Dokumente aus Moskauer Archiven, links=no) is a 1968 book by Soviet journalist Lev Bezymenski, who served as an interpreter in t ...

'', which includes previously unreleased photographs of the dental remains. The book transcribes a purported Soviet forensic examination led by Faust Shkaravsky, which concluded that Hitler died by cyanide poisoning. Bezymenski further theorised that Hitler requested a to ensure his quick death, but later admitted that his work included "deliberate lies", such as the manner of Hitler's death. The book and alleged autopsy have been widely derided by Western historians. Joachimsthaler, in his extensive analysis of the circumstances surrounding Hitler's death, quotes a German pathologist as saying about the purported autopsy: "Bezemensky's report is ridiculous. ... Any one of my assistants would have done better ... the whole thing is a farce ... it is intolerably bad work ... the transcript of the post-mortem section of 8 ay1945 describes anything but Hitler." Journalist James P. O'Donnell corrects the book's claim that cyanide acts instantaneously, saying Hitler could have taken poison and still had enough time to shoot himself.

Legacy

After Hitler's death and the subsequentend of World War II in Europe

The final battle of the European Theatre of World War II continued after the definitive overall surrender of Nazi Germany to the Allies, signed by Field marshal Wilhelm Keitel on 8 May 1945 in Karlshorst, Berlin. After German dictator Adolf H ...

, Germany was divided into four zones by the victorious Allies, who occupied the country. This led to the start of the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

between the Western Bloc

The Western Bloc, also known as the Free Bloc, the Capitalist Bloc, the American Bloc, and the NATO Bloc, was a coalition of countries that were officially allied with the United States during the Cold War of 1947–1991. It was spearheaded by ...

, supported by the US, and the Eastern Bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc and the Soviet Bloc, was the group of socialist states of Central and Eastern Europe, East Asia, Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America under the influence of the Soviet Union that existed du ...

, supported by the Soviet Union. The divide was for a time physically represented by the Berlin Wall

The Berlin Wall (german: Berliner Mauer, ) was a guarded concrete barrier that encircled West Berlin from 1961 to 1989, separating it from East Berlin and East Germany (GDR). Construction of the Berlin Wall was commenced by the government ...

, and was eventually followed by Germany's reunification in 1990 and the fall of the Iron Curtain

The Iron Curtain was the political boundary dividing Europe into two separate areas from the end of World War II in 1945 until the end of the Cold War in 1991. The term symbolizes the efforts by the Soviet Union (USSR) to block itself and its s ...

in 1991.

Following Hitler's death, war veteran and future American president John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination ...

wrote in his diary that the dictator "had a mystery about him in the way he lived and in the manner of his death that will live and grow after him". Historian Joachim Fest

Joachim Clemens Fest (8 December 1926 – 11 September 2006) was a German historian, journalist, critic and editor who was best known for his writings and public commentary on Nazi Germany, including a biography of Adolf Hitler and books about ...

opines that the almost "traceless" death of Hitler allowed him to stay in the public eye, granting him a "bizarre afterlife"; conspiracy theoriesrooted in Soviet disinformation alleging his survivalbolstered continued doubts and speculation, including outlandish tabloid and journalistic reports published into the late 20th century. Conspiracy theories about Hitler's death and about the Nazi era as a whole still attract interest, with books, TV shows, and films continuing to be produced on the topic. Historian Luke Daly-Groves wrote that Hitler's death is not about the death of one man, but carries a greater significance as to the end of the regime and the ideological impact it left behind.

Gallery

Joseph Goebbels

Paul Joseph Goebbels (; 29 October 1897 – 1 May 1945) was a German Nazi politician who was the ''Gauleiter'' (district leader) of Berlin, chief propagandist for the Nazi Party, and then Reich Minister of Propaganda from 1933 to 19 ...

, his wife Magda

Magda is a feminine given name, sometimes a short form ( hypocorism) of names such as Magdalena, which may refer to:

* Magda Apanowicz (born 1985), Canadian actress

* Magda B. Arnold (1903–2002), Czechoslovakian-born American psychologist

* M ...

, and their six children. Edited into the photo in the back is Goebbels' stepson, Harald Quandt

Harald Quandt (1 November 1921 – 22 September 1967) was a German industrialist, the son of industrialist Günther Quandt and Magda Behrend Rietschel. His parents divorced and his mother was later married to Joseph Goebbels. After World W ...

, the sole family member to survive the war.

File:Bundesarchiv Bild 183-1983-0331-500, Hermann Göring und Adolf Hitler bei Truppenbesuch.jpg, Hitler (right) visiting Berlin defenders in early April 1945 with Hermann Göring

Hermann Wilhelm Göring (or Goering; ; 12 January 1893 – 15 October 1946) was a German politician, military leader and convicted war criminal. He was one of the most powerful figures in the Nazi Party, which ruled Germany from 1933 to 1 ...

(centre) and the Chief of the OKW Field Marshal Keitel (partially hidden)

File:Bundesarchiv Bild 146-1982-044-11, Heinz Linge.jpg, Heinz Linge

Heinz Linge (23 March 1913 – 9 March 1980) was a German SS officer who served as a valet for the leader of Nazi Germany, Adolf Hitler, and became known for his close personal proximity to historical events. Linge was present in the ''Füh ...

, Hitler's valet, was one of the first people into Hitler's study after the suicides.

File:Churchill sits on bunker-chair.jpg, Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 during the Second World War, and again from 1 ...

sits on a damaged chair from the in July 1945.

File:Bundesarchiv Bild 183-M1204-319, Berlin, Reichskanzlei, gesprengter Führerbunker.jpg, The destroyed (1947)

See also

References

Informational notes

Citations

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

Books

* * * * * *Articles

* * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Hitler, Adolf * April 1945 events in Europe Battle of Berlin Deaths by person in Germany People declared dead in absentia Suicides in Germany 1945 suicides