The Suez Canal ( arz, قَنَاةُ ٱلسُّوَيْسِ, ') is an artificial

sea-level

Mean sea level (MSL, often shortened to sea level) is an average surface level of one or more among Earth's coastal bodies of water from which heights such as elevation may be measured. The global MSL is a type of vertical datuma standardised ...

waterway

A waterway is any navigable body of water. Broad distinctions are useful to avoid ambiguity, and disambiguation will be of varying importance depending on the nuance of the equivalent word in other languages. A first distinction is necessary b ...

in

Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

, connecting the

Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the ea ...

to the

Red Sea

The Red Sea ( ar, البحر الأحمر - بحر القلزم, translit=Modern: al-Baḥr al-ʾAḥmar, Medieval: Baḥr al-Qulzum; or ; Coptic: ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϩⲁϩ ''Phiom Enhah'' or ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϣⲁⲣⲓ ''Phiom ǹšari''; T ...

through the

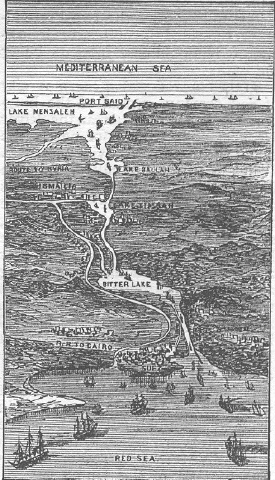

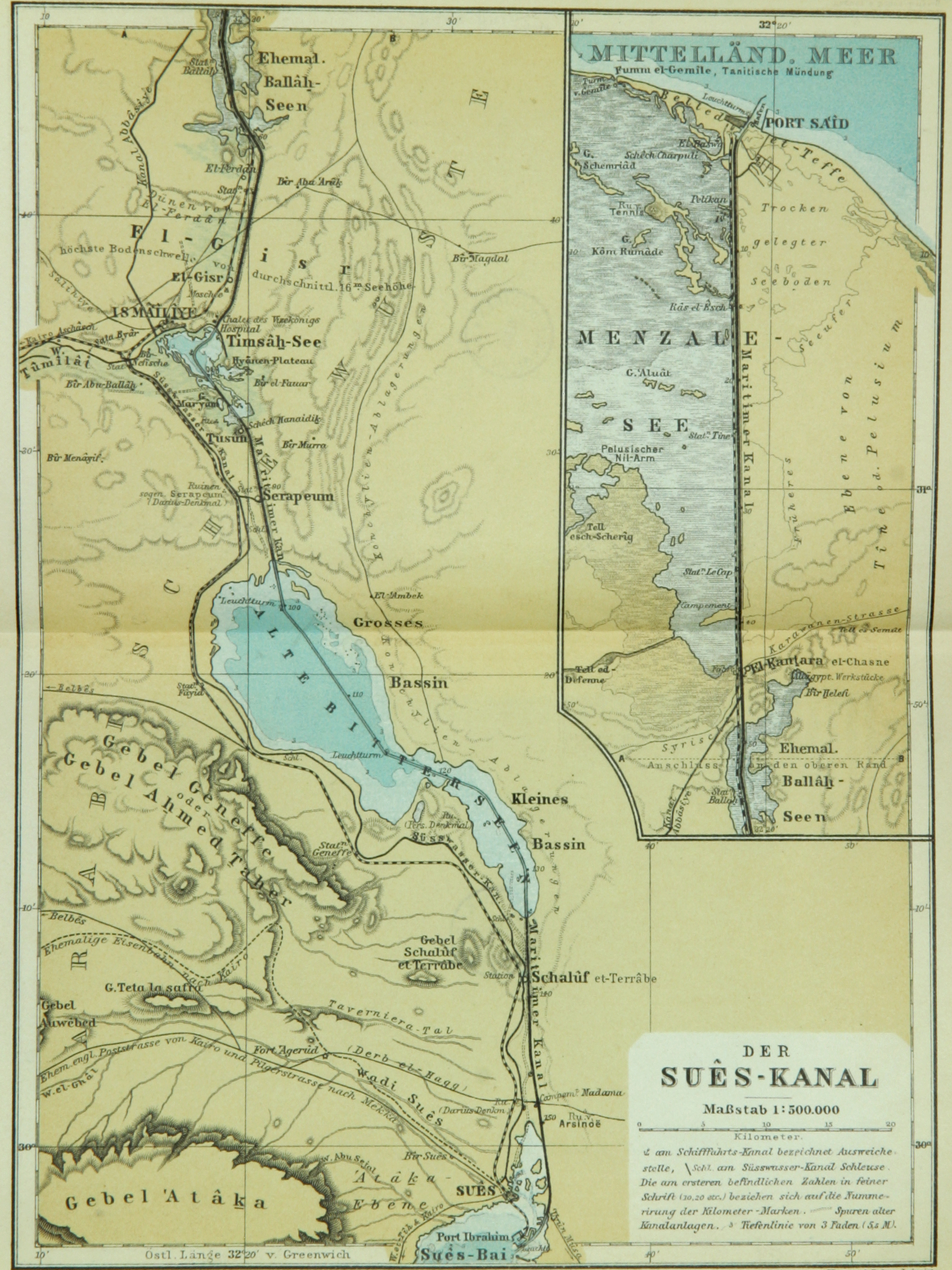

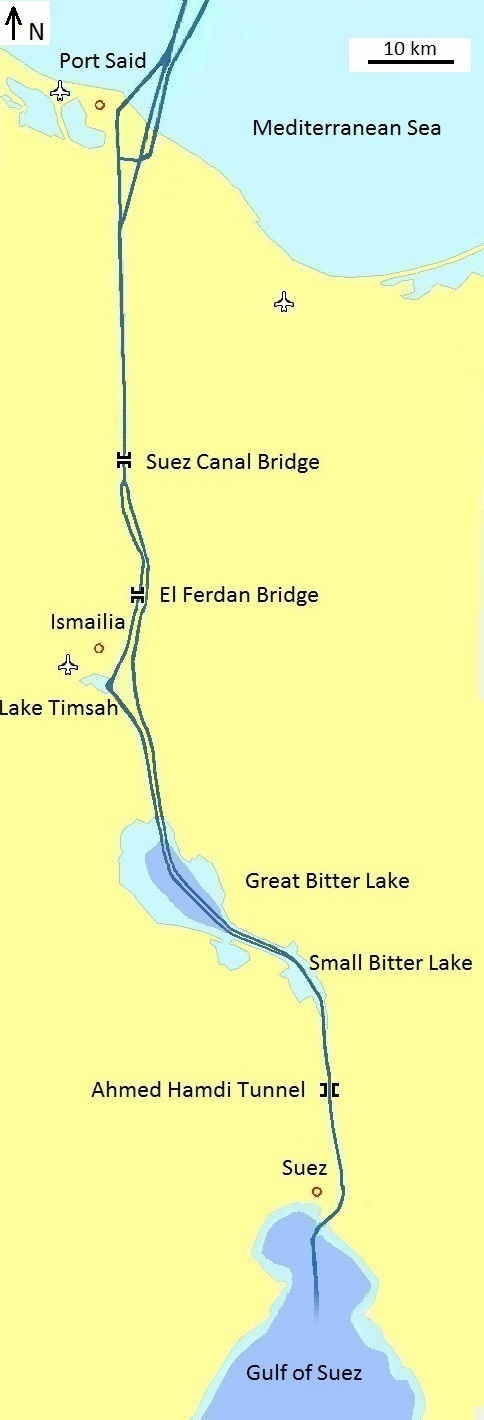

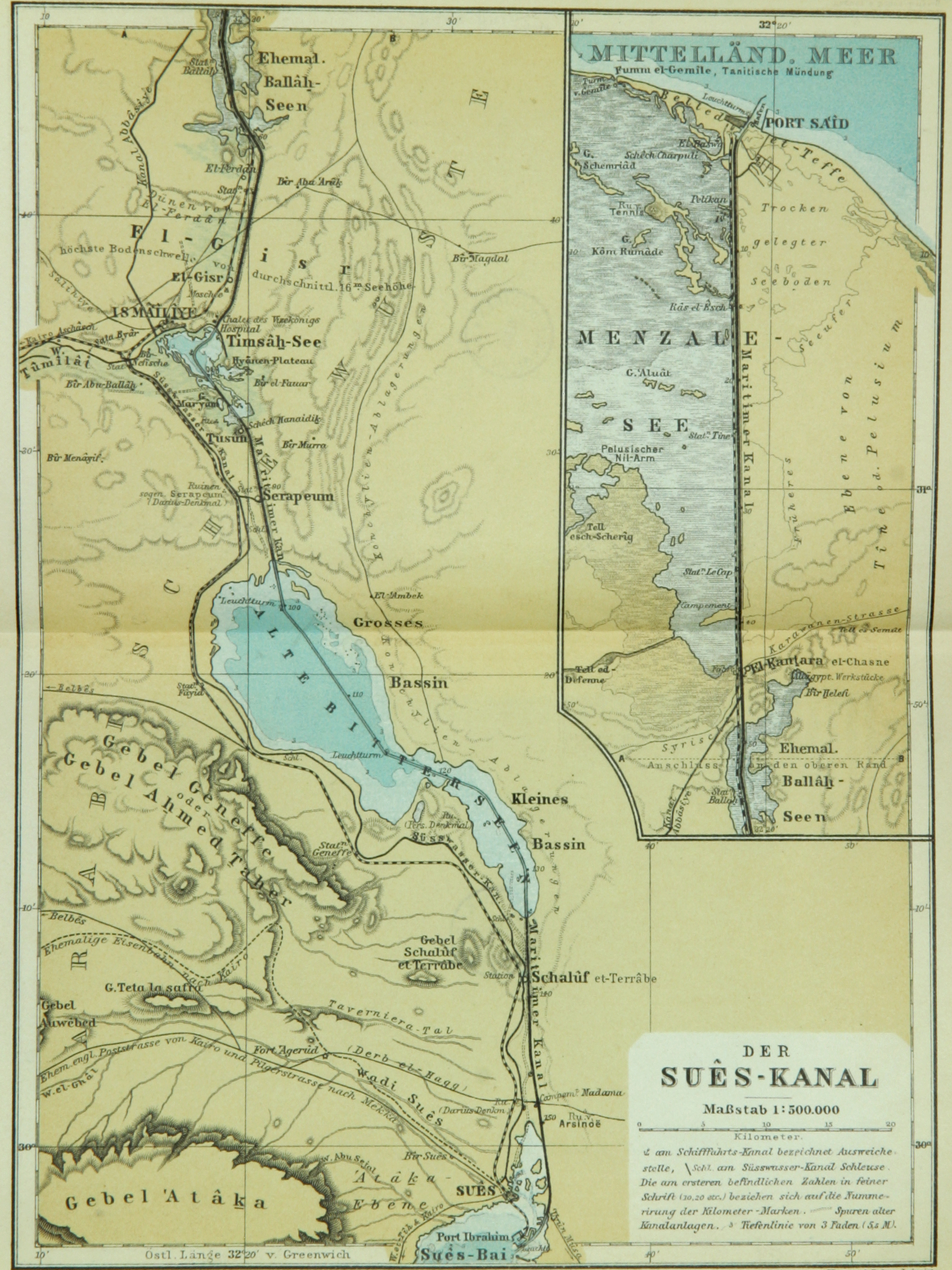

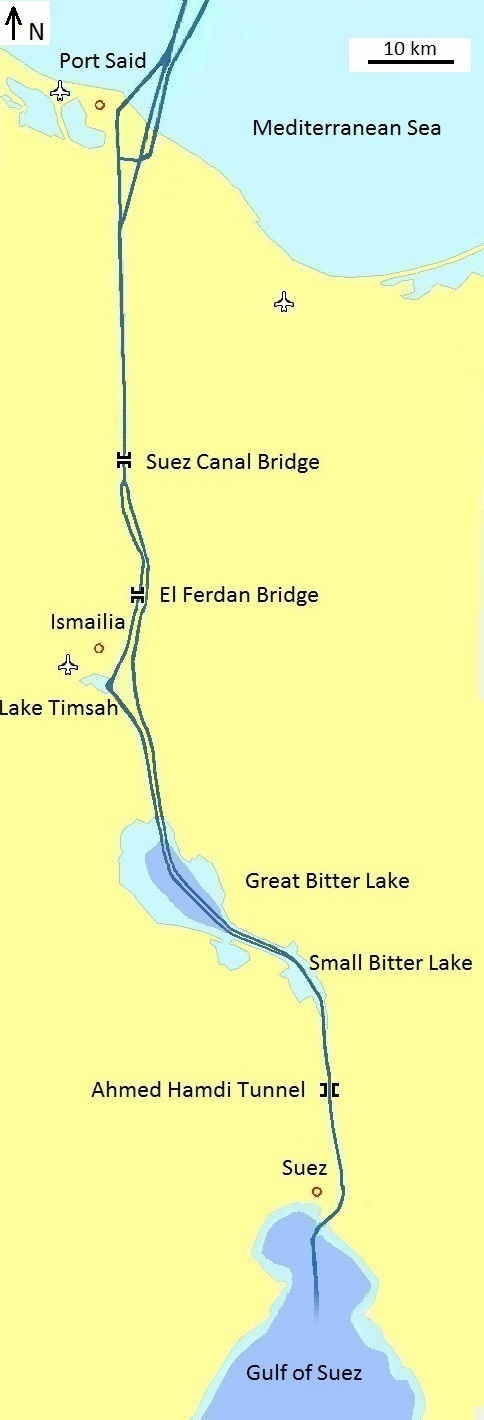

and dividing Africa and Asia. The long canal is a popular trade route between Europe and Asia.

In 1858,

Ferdinand de Lesseps

Ferdinand Marie, Comte de Lesseps (; 19 November 1805 – 7 December 1894) was a French diplomat and later developer of the Suez Canal, which in 1869 joined the Mediterranean and Red Seas, substantially reducing sailing distances and times ...

formed the

Suez Canal Company

Suez ( ar, السويس '; ) is a seaport city (population of about 750,000 ) in north-eastern Egypt, located on the north coast of the Gulf of Suez (a branch of the Red Sea), near the southern terminus of the Suez Canal, having the same b ...

for the express purpose of building the

canal

Canals or artificial waterways are waterways or engineered channels built for drainage management (e.g. flood control and irrigation) or for conveyancing water transport vehicles (e.g. water taxi). They carry free, calm surface flow un ...

. Construction of the canal lasted from 1859 to 1869. The canal officially opened on 17 November 1869. It offers vessels a direct route between the

North Atlantic and northern

Indian

Indian or Indians may refer to:

Peoples South Asia

* Indian people, people of Indian nationality, or people who have an Indian ancestor

** Non-resident Indian, a citizen of India who has temporarily emigrated to another country

* South Asia ...

oceans via the Mediterranean Sea and the Red Sea, avoiding the South Atlantic and southern Indian oceans and reducing the journey distance from the Arabian Sea to London by approximately , or 10 days at to 8 days at . The canal extends from the northern terminus of

Port Said to the southern terminus of

Port Tewfik

The Suez Port is an Egyptian port located at the southern boundary of the Suez Canal. It is bordered by the imaginary line extending from Ras-El-Adabieh to Moussa sources including the North Coast until the entrance of Suez Canal. Originally ''Por ...

at the city of

Suez

Suez ( ar, السويس '; ) is a seaport city (population of about 750,000 ) in north-eastern Egypt, located on the north coast of the Gulf of Suez (a branch of the Red Sea), near the southern terminus of the Suez Canal, having the same bou ...

. In 2021, more than 20,600 vessels traversed the canal (an average of 56 per day).

The original canal featured a single-lane waterway with passing locations in the Ballah Bypass and the

Great Bitter Lake

The Great Bitter Lake ( ar, البحيرة المرة الكبرى; transliterated: ''al-Buḥayrah al-Murra al-Kubrā'') is a large saltwater lake in Egypt that is part of the Suez Canal. Before the canal was built in 1869, the Great Bitter ...

. It contained, according to

Alois Negrelli

Nikolaus Alois Maria Vinzenz Negrelli, Ritter von Moldelbe (born Luigi Negrelli; 23 January 1799 – 1 October 1858) was a Tyrolean civil engineer and railroad pioneer mostly active in parts of the Austrian Empire, Switzerland, Germany and ...

's plans, no

lock

Lock(s) may refer to:

Common meanings

*Lock and key, a mechanical device used to secure items of importance

*Lock (water navigation), a device for boats to transit between different levels of water, as in a canal

Arts and entertainment

* ''Lock ...

systems, with seawater flowing freely through it. In general, the water in the canal north of the Bitter Lakes flows north in winter and south in summer. South of the lakes, the current changes with the

tide

Tides are the rise and fall of sea levels caused by the combined effects of the gravity, gravitational forces exerted by the Moon (and to a much lesser extent, the Sun) and are also caused by the Earth and Moon orbiting one another.

Tide t ...

at Suez.

The canal was the property of the Egyptian government, but European shareholders, mostly British and French, owned the

concessionary company

A concession or concession agreement is a grant of rights, land or property by a government, local authority, corporation, individual or other legal entity.

Public services such as water supply may be operated as a concession. In the case of a p ...

which operated it until July 1956, when President

Gamal Abdel Nasser nationalised it—an event which led to the

Suez Crisis

The Suez Crisis, or the Second Arab–Israeli war, also called the Tripartite Aggression ( ar, العدوان الثلاثي, Al-ʿUdwān aṯ-Ṯulāṯiyy) in the Arab world and the Sinai War in Israel,Also known as the Suez War or 1956 Wa ...

of October–November 1956.

The canal is operated and maintained by the state-owned

Suez Canal Authority

Suez Canal Authority (SCA) is an Egyptian state-owned authority which owns, operates and maintains the Suez Canal. It was set up by the Egyptian government to replace the Suez Canal Company in the 1950s which resulted in the Suez Crisis. After th ...

(SCA) of Egypt. Under the

Convention of Constantinople

The Convention of Constantinople is a treaty concerning the use of the Suez Canal in Egypt. It was signed on 29 October 1888 by the United Kingdom, Germany, Austria-Hungary, Spain, France, Italy, the Netherlands, the Russian Empire, and the Ott ...

, it may be used "in time of war as in time of peace, by every vessel of commerce or of war, without distinction of flag." Nevertheless, the canal has played an important military strategic role as a naval short-cut and

choke point

In military strategy, a choke point (or chokepoint) is a geographical feature on land such as a valley, defile or bridge, or maritime passage through a critical waterway such as a strait, which an armed force is forced to pass through in order ...

. Navies with coastlines and bases on both the Mediterranean Sea and the Red Sea (

Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

and

Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

) have a particular interest in the Suez Canal. After Egypt closed the Suez Canal at the beginning of the

Six-Day War

The Six-Day War (, ; ar, النكسة, , or ) or June War, also known as the 1967 Arab–Israeli War or Third Arab–Israeli War, was fought between Israel and a coalition of Arab states (primarily Egypt, Syria, and Jordan) from 5 to 10 Ju ...

on 5 June 1967, the canal remained closed for precisely eight years, reopening on 5 June 1975.

The Egyptian government launched construction in 2014 to expand and widen the Ballah Bypass for to speed up the canal's transit time. The expansion intended to nearly double the capacity of the Suez Canal, from 49 to 97 ships per day.

At a cost of LE 59.4 billion(US$9 billion), this project was funded with interest bearing investment certificates issued exclusively to Egyptian entities and individuals.

The Suez Canal Authority officially opened the new side channel in 2016. This side channel, at the northern side of the east extension of the Suez Canal, serves the East Terminal for berthing and unberthing vessels from the terminal. As the East Container Terminal is located on the Canal itself, before the construction of the new side channel it was not possible to berth or unberth vessels at the terminal while a convoy was running.

Precursors

Ancient west–east

canals

Canals or artificial waterways are waterways or river engineering, engineered channel (geography), channels built for drainage management (e.g. flood control and irrigation) or for conveyancing water transport watercraft, vehicles (e.g. ...

were built to facilitate travel from the

Nile

The Nile, , Bohairic , lg, Kiira , Nobiin language, Nobiin: Áman Dawū is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa and has historically been considered ...

to the

Red Sea

The Red Sea ( ar, البحر الأحمر - بحر القلزم, translit=Modern: al-Baḥr al-ʾAḥmar, Medieval: Baḥr al-Qulzum; or ; Coptic: ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϩⲁϩ ''Phiom Enhah'' or ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϣⲁⲣⲓ ''Phiom ǹšari''; T ...

.

[Rappoport, S. (Doctor of Philosophy, Basel). ''History of Egypt'' (undated, early 20th century), Volume 12, Part B, Chapter V: "The Waterways of Egypt", pp. 248–257. London: The Grolier Society.][Hassan, F. A. & Tassie, G. J. ''Site location and history'' (2003)]

Kafr Hassan Dawood On-Line, Egyptian Cultural Heritage Organization

. Retrieved 8 August 2008. One smaller canal is believed to have been constructed under the auspices of

Senusret II

Khakheperre Senusret II was the fourth pharaoh of the Twelfth Dynasty of Egypt. He ruled from 1897 BC to 1878 BC. His pyramid was constructed at El-Lahun. Senusret II took a great deal of interest in the Faiyum oasis region and began work on an ...

[Please refer to Sesostris#Modern research.] or

Ramesses II

Ramesses II ( egy, wikt:rꜥ-ms-sw, rꜥ-ms-sw ''Rīʿa-məsī-sū'', , meaning "Ra is the one who bore him"; ), commonly known as Ramesses the Great, was the third pharaoh of the Nineteenth Dynasty of Egypt. Along with Thutmose III he is oft ...

.

Another canal, probably incorporating a portion of the first,

was constructed under the reign of

Necho II

Necho II (sometimes Nekau, Neku, Nechoh, or Nikuu; Greek: Νεκώς Β'; ) of Egypt was a king of the 26th Dynasty (610–595 BC), which ruled from Sais. Necho undertook a number of construction projects across his kingdom. In his reign, accordi ...

, but the only fully functional canal was engineered and completed by

Darius I.

Second millennium BC

James Henry Breasted attributes the earliest known attempt to construct a canal to the

first cataract

The Cataracts of the Nile are shallow lengths (or whitewater rapids) of the Nile river, between Khartoum and Aswan, where the surface of the water is broken by many small boulders and stones jutting out of the river bed, as well as many rocky ...

, near Aswan, to the

Sixth Dynasty of Egypt

The Sixth Dynasty of ancient Egypt (notated Dynasty VI), along with the Third, Fourth and Fifth Dynasty, constitutes the Old Kingdom of Dynastic Egypt.

Pharaohs

Known pharaohs of the Sixth Dynasty are listed in the table below. Manetho a ...

and its completion to

Senusret III

Khakaure Senusret III (also written as Senwosret III or the hellenised form, Sesostris III) was a pharaoh of Egypt. He ruled from 1878 BC to 1839 BC during a time of great power and prosperity, and was the fifth king of the Twelfth Dynasty of the ...

of the

Twelfth Dynasty of Egypt

The Twelfth Dynasty of ancient Egypt (Dynasty XII) is considered to be the apex of the Middle Kingdom by Egyptologists. It often is combined with the Eleventh, Thirteenth, and Fourteenth dynasties under the group title, Middle Kingdom. Some ...

.

[J. H. Breasted, '']Ancient Records of Egypt

''Ancient Records of Egypt'' is a five-volume work by James Henry Breasted, published in 1906, in which the author has attempted to translate and publish ''all'' of the ancient written records of Egyptian history which had survived to the time of ...

'', 1906. Volume One, pp. 290–292, §§642–648. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

The legendary

Sesostris

Sesostris ( grc-gre, Σέσωστρις), also transliterated as Sesoösis, or Sesonchosis, is the name of a legendary king of ancient Egypt who, according to Herodotus, led a military expedition into parts of Europe. Tales of Sesostris are pro ...

(likely either

Pharaoh

Pharaoh (, ; Egyptian: ''pr ꜥꜣ''; cop, , Pǝrro; Biblical Hebrew: ''Parʿō'') is the vernacular term often used by modern authors for the kings of ancient Egypt who ruled as monarchs from the First Dynasty (c. 3150 BC) until the an ...

Senusret II

Khakheperre Senusret II was the fourth pharaoh of the Twelfth Dynasty of Egypt. He ruled from 1897 BC to 1878 BC. His pyramid was constructed at El-Lahun. Senusret II took a great deal of interest in the Faiyum oasis region and began work on an ...

or Senusret III of the Twelfth Dynasty of Egypt

) may have constructed the ancient canal, the

Canal of the Pharaohs

The Canal of the Pharaohs, also called the Ancient Suez Canal or Necho's Canal, is the forerunner of the Suez Canal, constructed in ancient times and kept in use, with intermissions, until being closed for good in 767 AD for strategic reasons du ...

, joining the Nile with the

Red Sea

The Red Sea ( ar, البحر الأحمر - بحر القلزم, translit=Modern: al-Baḥr al-ʾAḥmar, Medieval: Baḥr al-Qulzum; or ; Coptic: ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϩⲁϩ ''Phiom Enhah'' or ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϣⲁⲣⲓ ''Phiom ǹšari''; T ...

(BC 1897–1839), when an irrigation channel was constructed around BC 1848 that was navigable during the flood season, leading into a dry river valley east of the

Nile River Delta

The Nile Delta ( ar, دلتا النيل, or simply , is the delta formed in Lower Egypt where the Nile River spreads out and drains into the Mediterranean Sea. It is one of the world's largest river deltas—from Alexandria in the west to ...

named

Wadi Tumilat

Wadi Tumilat ( Old Egyptian Tjeku/Tscheku/Tju/Tschu) is the dry river valley ( wadi) to the east of the Nile Delta. In prehistory, it was a distributary of the Nile. It starts near the modern town of Zagazig and the ancient town of Bubastis ...

. (It is said that in

ancient times

Ancient history is a time period from the beginning of writing and recorded human history to as far as late antiquity. The span of recorded history is roughly 5,000 years, beginning with the Sumerian cuneiform script. Ancient history cov ...

the Red Sea reached northward to the

Bitter Lakes

The Great Bitter Lake ( ar, البحيرة المرة الكبرى; transliterated: ''al-Buḥayrah al-Murra al-Kubrā'') is a large saltwater lake in Egypt that is part of the Suez Canal. Before the canal was built in 1869, the Great Bitter L ...

and

Lake Timsah

Lake Timsah, also known as Crocodile Lake ( ar, بُحَيْرة التِّمْسَاح); is a lake in Egypt on the Nile delta. It lies in a basin developed along a fault extending from the Mediterranean Sea to the Gulf of Suez through the Bit ...

.

['']The Columbia Encyclopedia

The ''Columbia Encyclopedia'' is a one-volume encyclopedia produced by Columbia University Press and, in the last edition, sold by the Gale Group. First published in 1935, and continuing its relationship with Columbia University, the encyclopedi ...

'', Sixth Edition, s.v

"Suez Canal"

. Retrieved 14 May 2008.[ Naville, Édouard. "Map of the Wadi Tumilat" (plate image), in ''The Store-City of Pithom and the Route of the Exodus'' (1885). London: Trubner and Company.])

In his ''

Meteorology

Meteorology is a branch of the atmospheric sciences (which include atmospheric chemistry and physics) with a major focus on weather forecasting. The study of meteorology dates back millennia, though significant progress in meteorology did not ...

'',

Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of phil ...

(384–322 BC) wrote:

One of their kings tried to make a canal to it (for it would have been of no little advantage to them for the whole region to have become navigable; Sesostris is said to have been the first of the ancient kings to try), but he found that the sea was higher than the land. So he first, and Darius afterwards, stopped making the canal, lest the sea should mix with the river water and spoil it.

Strabo

Strabo''Strabo'' (meaning "squinty", as in strabismus) was a term employed by the Romans for anyone whose eyes were distorted or deformed. The father of Pompey was called "Pompeius Strabo". A native of Sicily so clear-sighted that he could see ...

wrote that Sesostris started to build a canal, and

Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/2479), called Pliny the Elder (), was a Roman author, naturalist and natural philosopher, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the emperor Vespasian. He wrote the encyclopedic '' ...

(AD 23/24–79)wrote:

165. Next comes the Tyro

In Greek mythology, Tyro ( grc, Τυρώ) was an Elean princess who later became Queen of Iolcus.

Family

Tyro was the daughter of King Salmoneus of Elis and Alcidice, daughter of King Aleus of Arcadia. She married her uncle King Cretheus ...

tribe and, the harbour of the Daneoi, from which Sesostris, king of Egypt, intended to carry a ship-canal to where the Nile flows into what is known as the Delta; this is a distance of over . Later the Persian king Darius had the same idea, and yet again Ptolemy II, who made a trench wide, deep and about long, as far as the Bitter Lakes.

In the 20th century, the northward extension of the later Darius I canal was discovered, extending from Lake Timsah to the Ballah Lakes.

[Shea, William H. "A Date for the Recently Discovered Eastern Canal of Egypt", in ''Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research'', No. 226 (April 1977), pp. 31–38.] This was dated to the

Middle Kingdom of Egypt

The Middle Kingdom of Egypt (also known as The Period of Reunification) is the period in the history of ancient Egypt following a period of political division known as the First Intermediate Period. The Middle Kingdom lasted from approximately ...

by extrapolating the dates of ancient sites along its course.

The reliefs of the

Punt expedition under

Hatshepsut

Hatshepsut (; also Hatchepsut; Egyptian: '' ḥꜣt- špswt'' "Foremost of Noble Ladies"; or Hatasu c. 1507–1458 BC) was the fifth pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt. She was the second historically confirmed female pharaoh, af ...

, BC 1470, depict seagoing vessels carrying the expeditionary force returning from Punt. This suggests that a navigable link existed between the Red Sea and the Nile. Recent

excavations in Wadi Gawasis may indicate that Egypt's maritime trade started from the Red Sea and did not require a canal. Evidence seems to indicate its existence by the 13th century BC during the time of

Ramesses II

Ramesses II ( egy, wikt:rꜥ-ms-sw, rꜥ-ms-sw ''Rīʿa-məsī-sū'', , meaning "Ra is the one who bore him"; ), commonly known as Ramesses the Great, was the third pharaoh of the Nineteenth Dynasty of Egypt. Along with Thutmose III he is oft ...

.

Canals dug by Necho, Darius I and Ptolemy

Remnants of an ancient west–east canal through the

ancient Egyptian cities of

Bubastis

Bubastis ( Bohairic Coptic: ''Poubasti''; Greek: ''Boubastis'' or ''Boubastos''), also known in Arabic as Tell-Basta or in Egyptian as Per-Bast, was an ancient Egyptian city. Bubastis is often identified with the biblical ''Pi-Beseth'' ( h ...

,

Pi-Ramesses

Pi-Ramesses (; Ancient Egyptian: , meaning "House of Ramesses") was the new capital built by the Nineteenth Dynasty Pharaoh Ramesses II (1279–1213 BC) at Qantir, near the old site of Avaris. The city had served as a summer palace under Set ...

, and

Pithom

Pithom ( Ancient Egyptian: ; Hebrew: ; Ancient Greek: or ) was an ancient city of Egypt. Multiple references in ancient Greek, Roman, and Hebrew Bible sources exist for this city, but its exact location remains somewhat uncertain. A number o ...

were discovered by

Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

and his engineers and cartographers in 1799.

According to the ''

Histories'' of the

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

historian

Herodotus

Herodotus ( ; grc, , }; BC) was an ancient Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus, part of the Persian Empire (now Bodrum, Turkey) and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria ( Italy). He is known f ...

, about BC 600,

Necho II

Necho II (sometimes Nekau, Neku, Nechoh, or Nikuu; Greek: Νεκώς Β'; ) of Egypt was a king of the 26th Dynasty (610–595 BC), which ruled from Sais. Necho undertook a number of construction projects across his kingdom. In his reign, accordi ...

undertook to dig a west–east canal through the Wadi Tumilat between Bubastis and

Heroopolis,

and perhaps continued it to the

Heroopolite Gulf and the Red Sea.

Regardless, Necho is reported as having never completed his project.

Herodotus was told that 120,000 men perished in this undertaking, but this figure is doubtless exaggerated. According to

Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/2479), called Pliny the Elder (), was a Roman author, naturalist and natural philosopher, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the emperor Vespasian. He wrote the encyclopedic '' ...

, Necho's extension to the canal was about ,

equal to the total distance between Bubastis and the Great Bitter Lake, allowing for winding through

valley

A valley is an elongated low area often running between hills or mountains, which will typically contain a river or stream running from one end to the other. Most valleys are formed by erosion of the land surface by rivers or streams ove ...

s.

The length that Herodotus tells, of over 1000

stadia

Stadia may refer to:

* One of the plurals of stadium, along with "stadiums"

* The plural of stadion, an ancient Greek unit of distance, which equals to 600 Greek feet (''podes'').

* Stadia (Caria), a town of ancient Caria, now in Turkey

* Stadi ...

(i.e., over ), must be understood to include the entire distance between the Nile and the Red Sea

at that time.

With Necho's death, work was discontinued. Herodotus tells that the reason the project was abandoned was because of a warning received from an

oracle that others would benefit from its successful completion.

Necho's war with

Nebuchadnezzar II most probably prevented the canal's continuation.

Necho's project was completed by

Darius I of Persia, who ruled over

Ancient Egypt after it had been conquered by his predecessor

Cambyses II. It may be that by Darius's time a natural

waterway passage which had existed

between the Heroopolite Gulf and the Red Sea

[Apparently, ]Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importance ...

considered the Great Bitter Lake as a northern extension of the Red Sea, whereas Darius had not, because Arsinoe is located north of Shaluf. (See Naville, "Map of the Wadi Tumilat", referenced above.) in the vicinity of the Egyptian town of Shaluf

(alt. ''Chalouf'' or ''Shaloof''

), located just south of the Great Bitter Lake,

had become so blocked

with

silt

Silt is granular material of a size between sand and clay and composed mostly of broken grains of quartz. Silt may occur as a soil (often mixed with sand or clay) or as sediment mixed in suspension with water. Silt usually has a floury feel ...

that Darius needed to clear it out so as to allow

navigation

Navigation is a field of study that focuses on the process of monitoring and controlling the movement of a craft or vehicle from one place to another.Bowditch, 2003:799. The field of navigation includes four general categories: land navigation, ...

once again. According to Herodotus, Darius's canal was wide enough that two

trireme

A trireme( ; derived from Latin: ''trirēmis'' "with three banks of oars"; cf. Greek ''triērēs'', literally "three-rower") was an ancient vessel and a type of galley that was used by the ancient maritime civilizations of the Mediterranean S ...

s could pass each other with oars extended, and required four days to traverse. Darius commemorated his achievement with a number of

granite

Granite () is a coarse-grained ( phaneritic) intrusive igneous rock composed mostly of quartz, alkali feldspar, and plagioclase. It forms from magma with a high content of silica and alkali metal oxides that slowly cools and solidifies under ...

stela

A stele ( ),Anglicized plural steles ( ); Greek plural stelai ( ), from Greek , ''stēlē''. The Greek plural is written , ''stēlai'', but this is only rarely encountered in English. or occasionally stela (plural ''stelas'' or ''stelæ''), wh ...

e that he set up on the Nile bank, including one near Kabret, and a further one a few kilometres north of Suez.

Darius the Great's Suez Inscriptions

Darius the Great's Suez Inscriptions were texts written in Old Persian, Elamite, Babylonian and Egyptian on five monuments erected in Wadi Tumilat, commemorating the opening of the " Canal of the Pharaohs", between the Nile and the Bitter Lak ...

read:

The canal left the Nile at Bubastis. An inscription on a pillar at

Pithom

Pithom ( Ancient Egyptian: ; Hebrew: ; Ancient Greek: or ) was an ancient city of Egypt. Multiple references in ancient Greek, Roman, and Hebrew Bible sources exist for this city, but its exact location remains somewhat uncertain. A number o ...

records that in 270 or 269 BCE, it was again reopened, by

Ptolemy II Philadelphus. In

Arsinoe,

Ptolemy constructed a

navigable lock, with

sluices, at the

Heroopolite Gulf of the Red Sea,

which allowed the passage of vessels but prevented salt water from the Red Sea from mingling with the fresh water in the canal.

In the second half of the 19th century, French

cartographers discovered the remnants of an ancient north–south canal past the east side of

Lake Timsah

Lake Timsah, also known as Crocodile Lake ( ar, بُحَيْرة التِّمْسَاح); is a lake in Egypt on the Nile delta. It lies in a basin developed along a fault extending from the Mediterranean Sea to the Gulf of Suez through the Bit ...

and ending near the north end of the Great Bitter Lake.

[''Carte hydrographique de l'Basse Egypte et d'une partie de l'Isthme de Suez'' (1855, 1882). Volume 87, page 803. Paris. Se]

This proved to be the canal made by Darius I, as his stele commemorating its construction was found at the site. (This ancient, second canal may have followed a course along the shoreline of the Red Sea when it once extended north to Lake Timsah.

)

Receding Red Sea and the dwindling Nile

The

Red Sea

The Red Sea ( ar, البحر الأحمر - بحر القلزم, translit=Modern: al-Baḥr al-ʾAḥmar, Medieval: Baḥr al-Qulzum; or ; Coptic: ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϩⲁϩ ''Phiom Enhah'' or ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϣⲁⲣⲓ ''Phiom ǹšari''; T ...

is believed by some

historian

A historian is a person who studies and writes about the past and is regarded as an authority on it. Historians are concerned with the continuous, methodical narrative and research of past events as relating to the human race; as well as the stu ...

s to have gradually receded over the centuries, its coastline slowly moving southward away from

Lake Timsah

Lake Timsah, also known as Crocodile Lake ( ar, بُحَيْرة التِّمْسَاح); is a lake in Egypt on the Nile delta. It lies in a basin developed along a fault extending from the Mediterranean Sea to the Gulf of Suez through the Bit ...

and the Great Bitter Lake.

Coupled with persistent accumulations of Nile

silt

Silt is granular material of a size between sand and clay and composed mostly of broken grains of quartz. Silt may occur as a soil (often mixed with sand or clay) or as sediment mixed in suspension with water. Silt usually has a floury feel ...

, maintenance and repair of Ptolemy's canal became increasingly cumbersome over each passing century.

Two hundred years after the construction of Ptolemy's canal,

Cleopatra seems to have had no west–east waterway passage,

because the Pelusiac branch of the Nile, which fed Ptolemy's west–east canal, had by that time dwindled, being choked with silt.

In support of this contention one can note that in 31 BCE, during a reversal of fortune in

Mark Antony

Marcus Antonius (14 January 1 August 30 BC), commonly known in English as Mark Antony, was a Roman politician and general who played a critical role in the transformation of the Roman Republic from a constitutional republic into the au ...

's and Cleopatra's war against

Octavian

Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian, was the first Roman emperor; he reigned from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. He is known for being the founder of the Roman Pr ...

, she attempted to escape Egypt with her fleet by raising the ships out of the Mediterranean and dragging them across the isthmus of Suez to the Red Sea. Then, according to

Plutarch

Plutarch (; grc-gre, Πλούταρχος, ''Ploútarchos''; ; – after AD 119) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for hi ...

, the

Arab

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

s of

Petra attacked and burned the first wave of these ships and Cleopatra abandoned the effort. (Modern historians, however, maintain that her ships were burned by the enemy forces of

Malichus I

Malichus I or Malchos I (Nabataean Aramaic: ''Malīḵū'' or

''Malīḵūʾ'') was a king of Nabataea who reigned from 59 to 30 BC.

Malichus was a possible cousin of Herod the Great of the Herodian kingdom. When Herod fled Judea in 40 BC to e ...

.)

Old Cairo to the Red Sea

By the 8th century, a navigable canal existed between

Old Cairo and the Red Sea,

but accounts vary as to who ordered its construction – either

Trajan

Trajan ( ; la, Caesar Nerva Traianus; 18 September 539/11 August 117) was Roman emperor from 98 to 117. Officially declared ''optimus princeps'' ("best ruler") by the senate, Trajan is remembered as a successful soldier-emperor who presi ...

or

'Amr ibn al-'As, or

Umar

ʿUmar ibn al-Khaṭṭāb ( ar, عمر بن الخطاب, also spelled Omar, ) was the second Rashidun caliph, ruling from August 634 until his assassination in 644. He succeeded Abu Bakr () as the second caliph of the Rashidun Caliphate ...

.

This canal was reportedly linked to the River Nile at Old Cairo

and ended near modern

Suez

Suez ( ar, السويس '; ) is a seaport city (population of about 750,000 ) in north-eastern Egypt, located on the north coast of the Gulf of Suez (a branch of the Red Sea), near the southern terminus of the Suez Canal, having the same bou ...

.

A geography treatise

''De Mensura Orbis Terrae'' written by the Irish monk

Dicuil

Dicuilus (or the more vernacular version of the name Dícuil) was an Irish monk and geographer, born during the second half of the 8th century.

Background

The exact dates of Dicuil's birth and death are unknown. Of his life nothing is known exce ...

(born late 8th century) reports a conversation with another monk, Fidelis, who had sailed on the canal from the Nile to the Red Sea during a pilgrimage to the Holy Land in the first half of the 8th century

The

Abbasid

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, الْخِلَافَةُ الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Muttalib ...

Caliph

A caliphate or khilāfah ( ar, خِلَافَة, ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with the title of caliph (; ar, خَلِيفَة , ), a person considered a political-religious successor to th ...

al-Mansur

Abū Jaʿfar ʿAbd Allāh ibn Muḥammad al-Manṣūr (; ar, أبو جعفر عبد الله بن محمد المنصور; 95 AH – 158 AH/714 CE – 6 October 775 CE) usually known simply as by his laqab Al-Manṣūr (المنصور) w ...

is said to have ordered this canal closed in 767 to prevent supplies from reaching

Arabian detractors.

Repair by al-Ḥākim

Al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah is claimed to have repaired the Cairo to Red Sea passageway, but only briefly, circa 1000 CE, as it soon "became choked with sand".

However, parts of this canal still continued to fill in during the Nile's annual inundations.

Conception by Venice

The successful 1488 navigation of southern Africa by

Bartolomeu Dias opened a direct maritime

trading route to India and the

Spice Islands

A spice is a seed, fruit, root, bark, or other plant substance primarily used for flavoring or coloring food. Spices are distinguished from herbs, which are the leaves, flowers, or stems of plants used for flavoring or as a garnish. Spices are ...

, and forever changed the balance of Mediterranean trade. One of the most prominent losers in the new order, as former middlemen, was the former spice trading center of

Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 ...

.

Despite entering negotiations with Egypt's ruling

Mamelukes, the

Venetian plan to build the canal was quickly put to rest by the

Ottoman conquest of Egypt in 1517, led by Sultan

Selim I

Selim I ( ota, سليم الأول; tr, I. Selim; 10 October 1470 – 22 September 1520), known as Selim the Grim or Selim the Resolute ( tr, links=no, Yavuz Sultan Selim), was the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1512 to 1520. Despite las ...

.

Ottoman attempts

During the 16th century, the Ottoman

Grand Vizier Sokollu Mehmed Pasha

Sokollu Mehmed Pasha ( ota, صوقوللى محمد پاشا, Ṣoḳollu Meḥmed Pașa, tr, Sokollu Mehmet Paşa; ; ; 1506 – 11 October 1579) was an Ottoman statesman most notable for being the Grand Vizier of the Ottoman Empire. Born in ...

attempted to construct a canal connecting the

Red Sea

The Red Sea ( ar, البحر الأحمر - بحر القلزم, translit=Modern: al-Baḥr al-ʾAḥmar, Medieval: Baḥr al-Qulzum; or ; Coptic: ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϩⲁϩ ''Phiom Enhah'' or ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϣⲁⲣⲓ ''Phiom ǹšari''; T ...

and the

Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western Europe, Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa ...

. This was motivated by a desire to connect

Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

to the

pilgrimage

A pilgrimage is a journey, often into an unknown or foreign place, where a person goes in search of new or expanded meaning about their self, others, nature, or a higher good, through the experience. It can lead to a personal transformation, aft ...

and

trade routes

A trade route is a Logistics, logistical network identified as a series of pathways and stoppages used for the commercial transport of cargo. The term can also be used to refer to trade over bodies of water. Allowing Good (economics and accounti ...

of the

Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or ~19.8% of the water on Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia to the east. To the south it is bounded by th ...

, as well as by strategic concerns—as the European presence in the Indian Ocean was growing, Ottoman mercantile and strategic interests were

increasingly challenged, and the

Sublime Porte

The Sublime Porte, also known as the Ottoman Porte or High Porte ( ota, باب عالی, Bāb-ı Ālī or ''Babıali'', from ar, باب, bāb, gate and , , ), was a synecdoche for the central government of the Ottoman Empire.

History

The name ...

was increasingly pressed to

assert its position. A navigable canal would allow the

Ottoman Navy to connect its

Red Sea

The Red Sea ( ar, البحر الأحمر - بحر القلزم, translit=Modern: al-Baḥr al-ʾAḥmar, Medieval: Baḥr al-Qulzum; or ; Coptic: ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϩⲁϩ ''Phiom Enhah'' or ⲫⲓⲟⲙ ⲛ̀ϣⲁⲣⲓ ''Phiom ǹšari''; T ...

,

Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Roma ...

, and

Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western Europe, Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa ...

fleets. However, this project was deemed too expensive, and was never completed.

Napoleon's discovery of an ancient canal

During the

French campaign in Egypt and Syria

The French campaign in Egypt and Syria (1798–1801) was Napoleon Bonaparte's campaign in the Ottoman territories of Egypt and Syria, proclaimed to defend French trade interests, to establish scientific enterprise in the region. It was the ...

in late 1798,

Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

expressed interest in finding the remnants of an ancient waterway passage. This culminated in a cadre of

archaeologists, scientists,

cartographers and engineers scouring northern Egypt.

Their findings, recorded in the ''

Description de l'Égypte

The ''Description de l'Égypte'' ( en, Description of Egypt) was a series of publications, appearing first in 1809 and continuing until the final volume appeared in 1829, which aimed to comprehensively catalog all known aspects of ancient and m ...

'', include detailed maps that depict the discovery of an ancient canal extending northward from the Red Sea and then westward toward the Nile.

Later, Napoleon, who became the French Emperor in 1804, contemplated the construction of a north–south canal to connect the Mediterranean with the Red Sea. But the plan was abandoned because it incorrectly concluded that the waterway would require locks to operate, the construction of which would be costly and time-consuming. The belief in the need for locks was based on the erroneous belief that the Red Sea was higher than the Mediterranean. This was the result of using fragmentary survey measurements taken in wartime during Napoleon's

Egyptian Expedition.

As late as 1861, the unnavigable ancient route discovered by Napoleon from

Bubastis

Bubastis ( Bohairic Coptic: ''Poubasti''; Greek: ''Boubastis'' or ''Boubastos''), also known in Arabic as Tell-Basta or in Egyptian as Per-Bast, was an ancient Egyptian city. Bubastis is often identified with the biblical ''Pi-Beseth'' ( h ...

to the Red Sea still channelled water as far east as

Kassassin

Kassassin ( ar, القصاصين) is a village of Lower Egypt by rail west of Ismailia, a major city on the Suez Canal.

Battle of Kassassin Lock

At the Sweet Water Canal, on August 28, 1882 the British force was attacked by the Egyptians, l ...

.

History of the Suez Canal

Interim period

Despite the construction challenges that could have been the result of the alleged difference in sea levels, the idea of finding a shorter route to the east remained alive. In 1830, General

Francis Chesney submitted a report to the British government that stated that there was no difference in elevation and that the Suez Canal was feasible, but his report received no further attention.

Lieutenant Waghorn established his "Overland Route", which transported post and passengers to India via Egypt.

[Wison, page 31

https://archive.org/details/suezcanal032262mbp

•Overland Route later known as the Steam ship route which was the connection from Suez to Cairo, then down the Nile to the Mahmoudieh Canal and to the Mediterranean port of Alexandria. Superseded by the Suez canal, it operated from 1830 to 1869 and from 1837 with steam ships in the Red sea.

•Between 1.36 and 2.49 deaths per thousand per year cited by the companies chief medical officer, page 31. Thus 34,258x2.49 deaths per thousand x 11 years=938 (highest reported working staff x highest reported deaths per thousand x number of years under construction)]

Linant de Bellefonds, a French explorer of Egypt, became chief engineer of

Egypt's Public Works. In addition to his normal duties, he surveyed the

and made plans for the Suez Canal. French

Saint-Simonianists showed an interest in the canal and in 1833,

Barthélemy Prosper Enfantin

Barthélemy, or Barthélémy is a French name, a cognate of Bartholomew. Notable people with this name include:

Given name

* Barthélemy (explorer), French youth who accompanied the explorer de La Salle in 1687

* Barthélémy Bisengimana, Con ...

tried to draw

Muhammad Ali's attention to the canal but was unsuccessful.

Alois Negrelli

Nikolaus Alois Maria Vinzenz Negrelli, Ritter von Moldelbe (born Luigi Negrelli; 23 January 1799 – 1 October 1858) was a Tyrolean civil engineer and railroad pioneer mostly active in parts of the Austrian Empire, Switzerland, Germany and ...

, the

Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, an ethnic group or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance language

*** Regional Ita ...

-

Austrian

Austrian may refer to:

* Austrians, someone from Austria or of Austrian descent

** Someone who is considered an Austrian citizen, see Austrian nationality law

* Austrian German dialect

* Something associated with the country Austria, for example: ...

railroad pioneer, became interested in the idea in 1836.

In 1846, Prosper Enfantin's

Société d'Études du Canal de Suez invited a number of experts, among them

Robert Stephenson

Robert Stephenson FRS HFRSE FRSA DCL (16 October 1803 – 12 October 1859) was an English civil engineer and designer of locomotives. The only son of George Stephenson, the "Father of Railways", he built on the achievements of his father ...

, Negrelli and

Paul-Adrien Bourdaloue to study the feasibility of the Suez Canal (with the assistance of Linant de Bellefonds). Bourdaloue's survey of the isthmus was the first generally accepted evidence that there was no practical difference in altitude between the two seas. Britain, however, feared that a canal open to everyone might interfere with its

India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

trade and therefore preferred a connection by train from

Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandria ...

via

Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo metro ...

to Suez, which Stephenson eventually built.

Construction by the Suez Canal Company

Preparations (1854–1858)

In 1854 and 1856,

Ferdinand de Lesseps

Ferdinand Marie, Comte de Lesseps (; 19 November 1805 – 7 December 1894) was a French diplomat and later developer of the Suez Canal, which in 1869 joined the Mediterranean and Red Seas, substantially reducing sailing distances and times ...

obtained a concession from

Sa'id Pasha

Mehmed Said Pasha ( ota, محمد سعيد پاشا ; 1838–1914), also known as Küçük Said Pasha ("Said Pasha the Younger") or Şapur Çelebi or in his youth as Mabeyn Başkatibi Said Bey, was an Ottoman monarchist, senator, statesman ...

, the

Khedive of

Egypt and Sudan, to create a company to construct a canal open to ships of all nations. The company was to operate the canal for 99 years from its opening. De Lesseps had used his friendly relationship with Sa'id, which he had developed while he was a French diplomat in the 1830s. As stipulated in the concessions, de Lesseps convened the

International Commission for the piercing of the isthmus of Suez (''Commission Internationale pour le percement de l'isthme de Suez'') consisting of 13 experts from seven countries, among them

John Robinson McClean

John Robinson McClean CB FRS FRSA FRAS (21 March 1813 – 13 July 1873), was a British civil engineer and Liberal Party politician. He carried out many important works, and for a time was the sole owner of a main line railway, the first indivi ...

, later President of the

Institution of Civil Engineers

The Institution of Civil Engineers (ICE) is an independent professional association for civil engineers and a charitable body in the United Kingdom. Based in London, ICE has over 92,000 members, of whom three-quarters are located in the UK, whi ...

in London, and again Negrelli, to examine the plans developed by

Linant de Bellefonds, and to advise on the feasibility of and the best route for the canal. After surveys and analyses in Egypt and discussions in Paris on various aspects of the canal, where many of Negrelli's ideas prevailed, the commission produced a unanimous report in December 1856 containing a detailed description of the canal complete with plans and profiles. The Suez Canal Company (''

Compagnie universelle du canal maritime de Suez'') came into being on 15 December 1858.

The British government had opposed the project from the outset to its completion. The British, who controlled both the

Cape route

The European-Asian sea route, commonly known as the sea route to India or the Cape Route, is a shipping route from the European coast of the Atlantic Ocean to Asia's coast of the Indian Ocean passing by the Cape of Good Hope and Cape Agulhas ...

and the Overland route to India and the Far East, favored the ''status quo'', given that a canal might disrupt their commercial and maritime supremacy.

Lord Palmerston

Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston, (20 October 1784 – 18 October 1865) was a British statesman who was twice Prime Minister of the United Kingdom in the mid-19th century. Palmerston dominated British foreign policy during the period ...

, the project's most unwavering foe, confessed in the mid-1850s the real motive behind his opposition: that Britain's commercial and maritime relations would be overthrown by the opening of a new route, open to all nations, and thus deprive his country of its present exclusive advantages. As one of the diplomatic moves against the project when it nevertheless went ahead, it disapproved of the use of "forced labour" for construction of the canal. Involuntary labour on the project ceased, and the viceroy condemned the corvée, halting the project.

Initially international opinion was sceptical and Suez Canal Company shares did not sell well overseas. Britain,

Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

, and

Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

did not buy a significant number of shares. With assistance from the Cattaui banking family, and their relationship with

James de Rothschild James de Rothschild may refer to:

* James de Rothschild (politician) (1878–1957), French-born British politician and philanthropist

* James Mayer de Rothschild

James Mayer de Rothschild, Baron de Rothschild (born Jakob Mayer Rothschild; 15 M ...

of the

French House of Rothschild bonds and shares were successfully promoted in France and other parts of Europe. All French shares were quickly sold in France. A contemporary British skeptic claimed "One thing is sure... our local merchant community doesn't pay practical attention at all to this grand work, and it is legitimate to doubt that the canal's receipts... could ever be sufficient to recover its maintenance fee. It will never become a large ship's accessible way in any case."

Construction (1859–1869)

Work started on the shore of the future Port Said on 25 April 1859.

The excavation took some 10 years, with

forced labour (

corvée

Corvée () is a form of unpaid, forced labour, that is intermittent in nature lasting for limited periods of time: typically for only a certain number of days' work each year.

Statute labour is a corvée imposed by a state for the purposes of ...

) being employed until 1864 to dig out the canal. Some sources estimate that over 30,000 people were working on the canal at any given period, that more than 1.5 million people from various countries were employed, and that tens of thousands of labourers died, many of them from

cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine by some strains of the bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea that lasts a few days. Vomiting and ...

and similar epidemics.

Estimates of the number of deaths vary widely with

Gamal Abdel Nasser citing 120,000 deaths upon nationalisation of the canal in a 26 July 1956 speech and the company's chief medical officer reporting no higher than 2.49 deaths per thousand in 1866.

Doubling these estimates with a generous assumption of 50,000 working staff per year over 11 years would put a conservative estimate at fewer than 3,000 deaths. More closely relying on the limited reported data of the time, the number would be fewer than 1,000.

Inauguration (17 November 1869)

The canal opened under French control in November 1869. The opening ceremonies began at Port Said on the evening of 15 November, with illuminations, fireworks, and a banquet on the yacht of the

Khedive Isma'il Pasha

Isma'il Pasha ( ar, إسماعيل باشا ; 12 January 1830 – 2 March 1895), was the Khedive of Egypt and conqueror of Sudan from 1863 to 1879, when he was removed at the behest of Great Britain. Sharing the ambitious outlook of his gran ...

of

Egypt and Sudan. The royal guests arrived the following morning: the

Emperor Franz Joseph I, the

French Empress Eugenie in the Imperial yacht ''L'Aigle'', the

Crown Prince

A crown prince or hereditary prince is the heir apparent to the throne in a royal or imperial monarchy. The female form of the title is crown princess, which may refer either to an heiress apparent or, especially in earlier times, to the wi ...

of

Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an em ...

, and

Prince Louis of Hesse.

Other international guests included the American natural historian

H. W. Harkness.

In the afternoon there were blessings of the canal with both Muslim and Christian ceremonies, a temporary mosque and church having been built side by side on the beach. In the evening there were more illuminations and fireworks.

[

On the morning of 17 November, a procession of ships entered the canal, headed by the ''L'Aigle''. Among the ships following was HMS ''Newport'', captained by ]George Nares

Vice-Admiral Sir George Strong Nares (24 April 1831 – 15 January 1915) was a Royal Navy officer and Arctic explorer. He commanded the ''Challenger'' Expedition, and the British Arctic Expedition. He was highly thought of as a leader an ...

, which surveyed the canal on behalf of the Admiralty

Admiralty most often refers to:

*Admiralty, Hong Kong

*Admiralty (United Kingdom), military department in command of the Royal Navy from 1707 to 1964

*The rank of admiral

*Admiralty law

Admiralty can also refer to:

Buildings

* Admiralty, Traf ...

a few months later.[ The first day of the passage ended at ]Lake Timsah

Lake Timsah, also known as Crocodile Lake ( ar, بُحَيْرة التِّمْسَاح); is a lake in Egypt on the Nile delta. It lies in a basin developed along a fault extending from the Mediterranean Sea to the Gulf of Suez through the Bit ...

, south of Port Said. The French ship ''Péluse'' anchored close to the entrance, then swung around and grounded, the ship and its hawser blocking the way into the lake. The following ships had to anchor in the canal itself until the ''Péluse'' was hauled clear the next morning, making it difficult for them to join that night's celebration in Ismailia

Ismailia ( ar, الإسماعيلية ', ) is a city in north-eastern Egypt. Situated on the west bank of the Suez Canal, it is the capital of the Ismailia Governorate. The city has a population of 1,406,699 (or approximately 750,000, includi ...

. Except for the ''Newport'': Nares sent out a boat to carry out soundings, and was able to manoeuver around the ''Péluse'' to enter the lake and anchor there for the night.[ After Suez, many of the participants headed for Cairo, and then to the Pyramids, where a new road had been built for the occasion.

An Anchor Line ship, the S.S. ''Dido'', became the first to pass through the Canal from South to North.

]

Initial difficulties (1869–1871)

Although numerous technical, political, and financial problems had been overcome, the final cost was more than double the original estimate.

The Khedive, in particular, was able to overcome initial reservations held by both British and French creditors by enlisting the help of the Sursock family

The Sursock family (also spelled Sursuq) is a Greek Orthodox Christian family from Lebanon, and used to be one of the most important families of Beirut. Having originated in Constantinople during the Byzantine Empire, the family has lived in Bei ...

, whose deep connections proved invaluable in securing much international support for the project.

After the opening, the Suez Canal Company was in financial difficulties. The remaining works were completed only in 1871, and traffic was below expectations in the first two years. De Lesseps therefore tried to increase revenues by interpreting the kind of net ton referred to in the second concession (''tonneau de capacité'') as meaning a ship's cargo capacity and not only the theoretical net tonnage of the "Moorsom System

The Moorsom System is a method created in the United Kingdom of calculating the tonnage

Tonnage is a measure of the cargo-carrying capacity of a ship, and is commonly used to assess fees on commercial shipping. The term derives from the taxat ...

" introduced in Britain by the Merchant Shipping Act in 1854. The ensuing commercial and diplomatic activities resulted in the International Commission of Constantinople establishing a specific kind of net tonnage and settling the question of tariffs in its protocol of 18 December 1873. This was the origin of the Suez Canal Net Tonnage and the Suez Canal Special Tonnage Certificate, both of which are still in use today.

Growth and reorganisation

The canal had an immediate and dramatic effect on world trade. Combined with the American transcontinental railroad completed six months earlier, it allowed the world to be circled in record time. It played an important role in increasing

The canal had an immediate and dramatic effect on world trade. Combined with the American transcontinental railroad completed six months earlier, it allowed the world to be circled in record time. It played an important role in increasing European colonization of Africa

The Scramble for Africa, also called the Partition of Africa, or Conquest of Africa, was the invasion, annexation, division, and colonization of most of Africa by seven Western European powers during a short period known as New Imperialism ...

. The construction of the canal was one of the reasons for the Panic of 1873

The Panic of 1873 was a financial crisis that triggered an economic depression in Europe and North America that lasted from 1873 to 1877 or 1879 in France and in Britain. In Britain, the Panic started two decades of stagnation known as the ...

in Great Britain, because goods from the Far East had, until then, been carried in sailing vessels around the Cape of Good Hope and stored in British warehouses. An inability to pay his bank debts led Said Pasha's successor, Isma'il Pasha

Isma'il Pasha ( ar, إسماعيل باشا ; 12 January 1830 – 2 March 1895), was the Khedive of Egypt and conqueror of Sudan from 1863 to 1879, when he was removed at the behest of Great Britain. Sharing the ambitious outlook of his gran ...

, in 1875 to sell his 44% share in the canal for £4,000,000 ($19.2 million), equivalent to £432 million to £456 million ($540 million to $570 million) in 2019, to the government of the United Kingdom. French shareholders still held the majority. Local unrest caused the British to invade in 1882 and take full control, although nominally Egypt remained part of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

. The British representative from 1883 to 1907 was Evelyn Baring, 1st Earl of Cromer

Evelyn Baring, 1st Earl of Cromer, (; 26 February 1841 – 29 January 1917) was a British statesman, diplomat and colonial administrator. He served as the British controller-general in Egypt during 1879, part of the international control whic ...

, who reorganized and modernized the government and suppressed rebellions and corruption, thereby facilitating increased traffic on the canal.

The European Mediterranean countries

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the e ...

in particular benefited economically from the Suez Canal, as they now had much faster connections to Asia and East Africa than the North and West European maritime trading nations such as Great Britain, the Netherlands or Germany. The biggest beneficiary in the Mediterranean was Austria-Hungary, which had participated in the planning and construction of the canal. The largest Austrian maritime trading company, Österreichischer Lloyd

''Österreichischer Lloyd'' ( it, Lloyd Austriaco, en, Austrian Lloyd) was the largest Austro-Hungarian shipping company. It was founded in 1833. It was based at Trieste in the Austrian Littoral, the main port of the Cisleithanian (Austrian ...

, experienced rapid expansion after the canal was completed, as did the port city of Trieste

Trieste ( , ; sl, Trst ; german: Triest ) is a city and seaport in northeastern Italy. It is the capital city, and largest city, of the autonomous region of Friuli Venezia Giulia, one of two autonomous regions which are not subdivided into provi ...

, then an Austrian possession. The company was a partner in the Compagnie Universelle du Canal de Suez, whose vice-president was the Lloyd co-founder Pasquale Revoltella.[Mary Pelletier "A brief history of the Suez Canal" In: Apollo 3 July 2018.]

The Convention of Constantinople

The Convention of Constantinople is a treaty concerning the use of the Suez Canal in Egypt. It was signed on 29 October 1888 by the United Kingdom, Germany, Austria-Hungary, Spain, France, Italy, the Netherlands, the Russian Empire, and the Ott ...

in 1888 declared the canal a neutral zone under the protection of the British, who had occupied Egypt and Sudan at the request of Khedive Tewfiq to suppress the Urabi Revolt against his rule. The revolt went on from 1879 to 1882. The British defended the strategically important passage against a major Ottoman attack in 1915, during the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

.[''First World War'' – Willmott, H.P. ]Dorling Kindersley

Dorling Kindersley Limited (branded as DK) is a British multinational publishing company specialising in illustrated reference books for adults and children in 63 languages.

It is part of Penguin Random House, a subsidiary of German media co ...

, 2003, p.87 Under the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty of 1936, the UK retained control over the canal. With outbreak of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

the canal was again strategically important; Italo-German attempts to capture it were repulsed during the North Africa Campaign, which ensured the canal remained closed to Axis

An axis (plural ''axes'') is an imaginary line around which an object rotates or is symmetrical. Axis may also refer to:

Mathematics

* Axis of rotation: see rotation around a fixed axis

* Axis (mathematics), a designator for a Cartesian-coordinat ...

shipping.

Suez Crisis

In 1951 Egypt repudiated the 1936 treaty with Great Britain. In October 1954 the UK tentatively agreed to remove its troops from the Canal Zone. Because of Egyptian overtures towards the

In 1951 Egypt repudiated the 1936 treaty with Great Britain. In October 1954 the UK tentatively agreed to remove its troops from the Canal Zone. Because of Egyptian overtures towards the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

, both the United Kingdom and the United States withdrew their pledge to financially support construction of the Aswan Dam

The Aswan Dam, or more specifically since the 1960s, the Aswan High Dam, is one of the world's largest embankment dams, which was built across the Nile in Aswan, Egypt, between 1960 and 1970. Its significance largely eclipsed the previous Aswan L ...

. Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser responded by nationalising the canal on 26 July 1956 and transferring it to the Suez Canal Authority

Suez Canal Authority (SCA) is an Egyptian state-owned authority which owns, operates and maintains the Suez Canal. It was set up by the Egyptian government to replace the Suez Canal Company in the 1950s which resulted in the Suez Crisis. After th ...

, intending to finance the dam project using revenue from the canal. On the same day that the canal was nationalised Nasser also closed the Straits of Tiran to all Israeli ships. This led to the Suez Crisis

The Suez Crisis, or the Second Arab–Israeli war, also called the Tripartite Aggression ( ar, العدوان الثلاثي, Al-ʿUdwān aṯ-Ṯulāṯiyy) in the Arab world and the Sinai War in Israel,Also known as the Suez War or 1956 Wa ...

in which the UK, France, and Israel invaded Egypt. According to the pre-agreed war plans under the Protocol of Sèvres

The Protocol of Sèvres (French, ''Protocole de Sèvres'') was a secret agreement reached between the governments of Israel, France and the United Kingdom during discussions held between 22 and 24 October 1956 at Sèvres, France. The protocol c ...

, Israel invaded the Sinai Peninsula

The Sinai Peninsula, or simply Sinai (now usually ) (, , cop, Ⲥⲓⲛⲁ), is a peninsula in Egypt, and the only part of the country located in Asia. It is between the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Red Sea to the south, and is ...

on 29 October, forcing Egypt to engage them militarily, and allowing the Anglo-French

Anglo-French (or sometimes Franco-British) may refer to:

*France–United Kingdom relations

*Anglo-Norman language or its decendants, varieties of French used in medieval England

*Anglo-Français and Français (hound), an ancient type of hunting d ...

partnership to declare the resultant fighting a threat to stability in the Middle East and enter the war – officially to separate the two forces but in reality to regain the Canal and bring down the Nasser government.

To save the British from what he thought was a disastrous action and to stop the war from a possible escalation, Canadian Secretary of State for External Affairs Lester B. Pearson

Lester Bowles "Mike" Pearson (23 April 1897 – 27 December 1972) was a Canadian scholar, statesman, diplomat, and politician who served as the 14th prime minister of Canada from 1963 to 1968.

Born in Newtonbrook, Ontario (now part of ...

proposed the creation of the first United Nations peacekeeping force to ensure access to the canal for all and an Israeli withdrawal from the Sinai Peninsula. On 4 November 1956, a majority at the United Nations voted for Pearson's peacekeeping resolution, which mandated the UN peacekeepers to stay in Sinai unless both Egypt and Israel agreed to their withdrawal. The United States backed this proposal by putting pressure on the British government through the selling of sterling, which would cause it to depreciate. Britain then called a ceasefire, and later agreed to withdraw its troops by the end of the year. Pearson was later awarded the Nobel Peace Prize

The Nobel Peace Prize is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the will of Swedish industrialist, inventor and armaments (military weapons and equipment) manufacturer Alfred Nobel, along with the prizes in Chemistry, Physics, Physiolog ...

. As a result of damage and ships sunk under orders from Nasser the canal was closed until April 1957, when it was cleared with UN assistance. A UN force (UNEF UNEF may refer to:

* United Nations Emergency Force, a UN force deployed in the Middle East in 1956

* UNEF, a designation for Extra-Fine thread series of Standard Unified Screw Threads (ANSI B1.1)

* Union Nationale des Étudiants de France (Natio ...

) was established to maintain the free navigability of the canal, and peace in the Sinai Peninsula.

Arab–Israeli wars of 1967 and 1973

Prior to the 1967 war, Egypt had repeatedly closed the canal to Israeli shipping as a defensive measure, refusing to open the canal in 1949 and during the 1956

Prior to the 1967 war, Egypt had repeatedly closed the canal to Israeli shipping as a defensive measure, refusing to open the canal in 1949 and during the 1956 Suez Crisis

The Suez Crisis, or the Second Arab–Israeli war, also called the Tripartite Aggression ( ar, العدوان الثلاثي, Al-ʿUdwān aṯ-Ṯulāṯiyy) in the Arab world and the Sinai War in Israel,Also known as the Suez War or 1956 Wa ...

. Egypt did so despite UN Security Council resolutions from 1949 and 1951 urging it not to, claiming that hostilities had ended with the 1949 armistice agreement

The 1949 Armistice Agreements were signed between Israel and Egypt,[Sinai Peninsula

The Sinai Peninsula, or simply Sinai (now usually ) (, , cop, Ⲥⲓⲛⲁ), is a peninsula in Egypt, and the only part of the country located in Asia. It is between the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Red Sea to the south, and is ...](_blank)

, including the Suez Canal area, Egyptian troops were sent into Sinai to take their place. Israel protested Nasser's order to close the Straits of Tiran to Israeli trade on 21 May, the same year. This halted Israeli shipping between the port of Eilat and the Red Sea.Six-Day War

The Six-Day War (, ; ar, النكسة, , or ) or June War, also known as the 1967 Arab–Israeli War or Third Arab–Israeli War, was fought between Israel and a coalition of Arab states (primarily Egypt, Syria, and Jordan) from 5 to 10 Ju ...

, Israeli forces occupied the Sinai Peninsula, including the entire east bank of the Suez Canal. In the following years the tensions between Egypt and Israeli intensified and from March 1969 until August 1970, a war of attrition took place as the then Egyptian president, Gamal Abdel Nasser, tried to retake the territories occupied by Israel during the conflict. The fighting ceased after the death of Nasser in 1970. After this conflict there were no changes in the distribution of territory, but the underlying tensions persisted.Yellow Fleet

From 1967 to 1975, fifteen ships and their crews were trapped in the Suez Canal after the Six-Day War between Israel and Egypt. The stranded ships, which belonged to eight countries (West Germany, Sweden, France, the United Kingdom, the United ...

", were trapped in the canal, and remained there until its reopening in 1975.

On 6 October 1973, during the Yom Kippur War

The Yom Kippur War, also known as the Ramadan War, the October War, the 1973 Arab–Israeli War, or the Fourth Arab–Israeli War, was an armed conflict fought from October 6 to 25, 1973 between Israel and a coalition of Arab states led by E ...

, the canal was the scene of the Operation Badr, in which the Egyptian military crossed the Suez Canal into Israeli-occupied Sinai Peninsula. Much wreckage from this conflict remains visible along the canal's edges.OPEC

The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC, ) is a cartel of countries. Founded on 14 September 1960 in Baghdad by the first five members (Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and Venezuela), it has, since 1965, been headquart ...

to raise the price of crude oil by around 17 percent and eventually imposed an embargo against the United States and other Israeli allies.

Mine clearing operations (1974–75)

After the Yom Kippur War, the United States initiated Operation Nimbus Moon. The amphibious assault ship

An amphibious assault ship is a type of amphibious warfare ship employed to land and support ground forces on enemy territory by an amphibious assault. The design evolved from aircraft carriers converted for use as helicopter carriers (and, a ...

USS ''Inchon (LPH-12)'' was sent to the Canal, carrying 12 RH-53D

The CH-53 Sea Stallion (Sikorsky S-65) is an American family of heavy-lift transport helicopters designed and built by the American manufacturer Sikorsky Aircraft.

It was originally developed in response to a request from the United States ...

minesweeping helicopters of Helicopter Mine Countermeasures Squadron 12. These partly cleared the canal between May and December 1974. She was relieved by the LST USS ''Barnstable County'' (LST1197). The British Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

initiated Operation Rheostat and Task Group 65.2 provided for Operation Rheostat One (six months in 1974), the minehunters HMS ''Maxton'', HMS ''Bossington'', and HMS ''Wilton'', the Fleet Clearance Diving Team (FCDT) and HMS ''Abdiel'', a practice minelayer/MCMV support ship; and for Operation Rheostat Two (six months in 1975) the minehunters HMS ''Hubberston'' and HMS ''Sheraton'', and HMS ''Abdiel''. When the Canal Clearance Operations were completed, the canal and its lakes were considered 99% clear of mines. The canal was then reopened by Egyptian President Anwar Sadat

Muhammad Anwar el-Sadat, (25 December 1918 – 6 October 1981) was an Egyptian politician and military officer who served as the third president of Egypt, from 15 October 1970 until his assassination by fundamentalist army officers on 6 ...

aboard an Egyptian destroyer, which led the first convoy northbound to Port Said in 1975, at his side stood the Iranian Crown Prince Reza Pahlavi.

UN presence

The UNEF UNEF may refer to:

* United Nations Emergency Force, a UN force deployed in the Middle East in 1956

* UNEF, a designation for Extra-Fine thread series of Standard Unified Screw Threads (ANSI B1.1)

* Union Nationale des Étudiants de France (Natio ...

mandate expired in 1979. Despite the efforts of the United States, Israel, Egypt, and others to obtain an extension of the UN role in observing the peace between Israel and Egypt, as called for under the Egypt–Israel peace treaty

The Egypt–Israel peace treaty ( ar, معاهدة السلام المصرية الإسرائيلية, Mu`āhadat as-Salām al-Misrīyah al-'Isrā'īlīyah; he, הסכם השלום בין ישראל למצרים, ''Heskem HaShalom Bein Yisrael ...

of 1979, the mandate could not be extended because of the veto by the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

in the UN Security Council

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is one of the Organs of the United Nations, six principal organs of the United Nations (UN) and is charged with ensuring international security, international peace and security, recommending the admi ...

, at the request of Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

. Accordingly, negotiations for a new observer force in the Sinai produced the Multinational Force and Observers

The Multinational Force and Observers (MFO) is an international peacekeeping force overseeing the terms of the peace treaty between Egypt and Israel. The MFO generally operates in and around the Sinai peninsula, ensuring free navigation through ...

(MFO), stationed in Sinai in 1981 in coordination with a phased Israeli withdrawal. The MFO remains active under agreements between the United States, Israel, Egypt, and other nations.

Bypass expansion

In 2014, months after taking office as

In 2014, months after taking office as President of Egypt

The president of Egypt is the executive head of state of Egypt and the de facto appointer of the official head of government under the Egyptian Constitution of 2014. Under the various iterations of the Constitution of Egypt following the E ...

, Abdel Fattah el-Sisi

Abdel Fattah Saeed Hussein Khalil el-Sisi; (born 19 November 1954) is an Egyptian politician and retired military officer who has served as the sixth and current president of Egypt since 2014. Before retiring as a general in the Egyptian mil ...

ordered the expansion of the Ballah Bypass from wide to wide for . The project was called the New Suez Canal