Stalin and antisemitism on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The accusation that

available online

Translated version: "Stalin", 1996, (hardcover), 1997, (paperback) Ch. 24

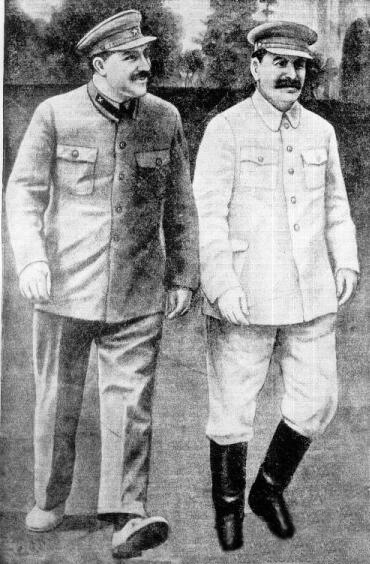

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet Union, Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as Ge ...

was antisemitic

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Ant ...

is much discussed by historians. Although part of a movement that included Jews and rejected antisemitism, he privately displayed a contemptuous attitude toward Jews on various occasions that were witnessed by his contemporaries, and are documented by historical sources. In 1939, he reversed Communist policy and began a cooperation with Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

that included the removal of high profile Jews from the Kremlin. As dictator of the Soviet Union, he promoted repressive policies that conspicuously impacted Jews shortly after World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, especially during the anti-cosmopolitan campaign

The anti-cosmopolitan campaign (russian: Борьба с космополитизмом, ) was a thinly disguised antisemitic campaign in the Soviet Union which began in late 1948. Jews were characterized as rootless cosmopolitans and were targe ...

. At the time of his death, Stalin was planning an even larger campaign against Jews. According to his successor Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and chairman of the country's Council of Ministers from 1958 to 1964. During his rule, Khrushchev s ...

, Stalin was fomenting the doctors' plot

The "Doctors' plot" affair, group=rus was an alleged conspiracy of prominent Soviet medical specialists to murder leading government and party officials. It was also known as the case of saboteur doctors or killer doctors. In 1951–1953, a gr ...

as a pretext for further anti-Jewish repressions.

Early years

Born inGori, Georgia

Gori ( ka, გორი ) is a city in eastern Georgia, which serves as the regional capital of Shida Kartli and is located at the confluence of two rivers, the Mtkvari and the Liakhvi. Gori is the fifth most populous city in Georgia. Its n ...

(then in the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War ...

) and educated at an Orthodox seminary in Tiflis

Tbilisi ( ; ka, თბილისი ), in some languages still known by its pre-1936 name Tiflis ( ), is the capital and the largest city of Georgia, lying on the banks of the Kura River with a population of approximately 1.5 million pe ...

(Tbilisi) before becoming a professional revolutionary and a Marxist

Marxism is a left-wing to far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand class relations and social conflict and a dialecti ...

around the start of the 20th century, Stalin appears unlikely to have been stirred by antisemitism

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

in his early years and met only a limited number of revolutionaries of Jewish origin during his first years of political activity.Pinkus, Benjamin (1990). ''The Jews of the Soviet Union: The History of a National Minority''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 143–144. . Although active in the Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

faction of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party

The Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP; in , ''Rossiyskaya sotsial-demokraticheskaya rabochaya partiya (RSDRP)''), also known as the Russian Social Democratic Workers' Party or the Russian Social Democratic Party, was a socialist pol ...

, he did not attend a party congress until 1905.

Although Jews were active among both the Social Democratic Bolshevik and the Menshevik

The Mensheviks (russian: меньшевики́, from меньшинство 'minority') were one of the three dominant factions in the Russian socialist movement, the others being the Bolsheviks and Socialist Revolutionaries.

The factions em ...

factions, Jews were more prominent among the Mensheviks. Stalin took note of the ethnic proportions represented on each side, as seen from a 1907 report on the Congress published in the ''Bakinsky rabochy'' (''Baku

Baku (, ; az, Bakı ) is the capital and largest city of Azerbaijan, as well as the largest city on the Caspian Sea and of the Caucasus region. Baku is located below sea level, which makes it the lowest lying national capital in the world an ...

Workman''), which quoted a coarse joke about "a small pogrom

A pogrom () is a violent riot incited with the aim of massacring or expelling an ethnic or religious group, particularly Jews. The term entered the English language from Russian to describe 19th- and 20th-century attacks on Jews in the Russian ...

" (погромчик) Stalin attributed to then-Bolshevik Grigory Aleksinsky

Grigory Alekseyevich Aleksinsky (Russian: Григорий Алексеевич Алексинский; September 16, 1879, Botlikh, Dagestan Oblast, – October 4, 1967, Paris) was a prominent Russian Marxist activist, Social Democrat and Bolshe ...

:

Not less interesting is the composition of the congress from the standpoint of nationalities. Statistics showed that the majority of the Menshevik faction consists of Jewsand this of course without counting theBundists Bundism was a secular Jewish socialist movement whose organizational manifestation was the General Jewish Labour Bund in Lithuania, Poland, and Russia ( yi, אַלגעמײַנער ײדישער אַרבעטער בּונד אין ליטע פויל ...after which came Georgians and then Russians. On the other hand, the overwhelming majority of the Bolshevik faction consists of Russians, after which come Jewsnot counting of course thePoles Poles,, ; singular masculine: ''Polak'', singular feminine: ''Polka'' or Polish people, are a West Slavic nation and ethnic group, who share a common history, culture, the Polish language and are identified with the country of Poland in ...and Lettsand then Georgians, etc. For this reason one of the Bolsheviks observed in jest (it seems Comrade Aleksinsky) that the Mensheviks are a Jewish faction and the Bolsheviks a genuine Russian faction, so it would not be a bad idea for us Bolsheviks to arrange a small pogrom in the party.

1917 to 1930

Although the Bolsheviks regarded all religious activity as counter-scientific superstition and a remnant of the old pre-communist order, the new political order established byLenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 1 ...

's Soviet after the Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of political and social revolution that took place in the former Russian Empire which began during the First World War. This period saw Russia abolish its monarchy and adopt a socialist form of government ...

ran counter to the centuries of antisemitism under the Romanovs.

The Council of People's Commissars

The Councils of People's Commissars (SNK; russian: Совет народных комиссаров (СНК), ''Sovet narodnykh kommissarov''), commonly known as the ''Sovnarkom'' (Совнарком), were the highest executive authorities of ...

adopted a 1918 decree condemning all antisemitism and calling on the workers and peasants to combat it.Pinkus, Benjamin (1990). ''The Jews of the Soviet Union: The History of a National Minority''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 85. . Lenin continued to speak out against antisemitism. Information campaigns against antisemitism were conducted in the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian language, Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist R ...

and in the workplaces, and a provision forbidding the incitement of propaganda against any ethnicity became part of Soviet law. State-sponsored institutions of secular Yiddish culture, such as the Moscow State Jewish Theater, were established in Soviet Russia and the Soviet Union during this time, as were institutions for other minorities.

As People's Commissar for Nationalities, Stalin was the cabinet member responsible for minority affairs. In 1922, Stalin was elected the first-ever General Secretary

Secretary is a title often used in organizations to indicate a person having a certain amount of authority, power, or importance in the organization. Secretaries announce important events and communicate to the organization. The term is derived ...

of the party—a post not yet regarded as the highest in the Soviet government. Lenin began to criticize Stalin shortly thereafter.

In his December 1922 letters, the ailing Lenin (whose health left him incapacitated in 1923–1924) criticized Stalin and Dzerzhinsky for their chauvinistic attitude toward the Georgian nation during the Georgian Affair. Eventually made public as part of Lenin's Testament

Lenin's Testament is a document dictated by Vladimir Lenin in late 1922 and early 1923. In the testament, Lenin proposed changes to the structure of the Soviet governing bodies. Sensing his impending death, he also gave criticism of Bolshevik lea ...

—which recommended that the party remove Stalin from his post as General Secretary—the 1922 letters and the recommendation were both withheld from public circulation by Stalin and his supporters in the party: these materials were not published in the Soviet Union until de-Stalinization

De-Stalinization (russian: десталинизация, translit=destalinizatsiya) comprised a series of political reforms in the Soviet Union after the death of long-time leader Joseph Stalin in 1953, and the thaw brought about by ascension ...

in 1956.

After the incapacitated Lenin's death on 21 January 1924, the party officially maintained the principle of collective leadership, but Stalin soon outmaneuvered his rivals in the Central Committee's Politburo

A politburo () or political bureau is the executive committee for communist parties. It is present in most former and existing communist states.

Names

The term "politburo" in English comes from the Russian ''Politbyuro'' (), itself a contracti ...

. At first collaborating with Jewish and half-Jewish Politburo members Grigory Zinoviev

Grigory Yevseyevich Zinoviev, . Transliterated ''Grigorii Evseevich Zinov'ev'' according to the Library of Congress system. (born Hirsch Apfelbaum, – 25 August 1936), known also under the name Ovsei-Gershon Aronovich Radomyslsky (russian: Ов ...

and Lev Kamenev

Lev Borisovich Kamenev. (''né'' Rozenfeld; – 25 August 1936) was a Bolshevik revolutionary and a prominent Soviet politician.

Born in Moscow to parents who were both involved in revolutionary politics, Kamenev attended Imperial Moscow Uni ...

against Jewish arch-rival Leon Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein. ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky; uk, link= no, Лев Давидович Троцький; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trotskij'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky''. (), was a Russian ...

, Stalin succeeded in marginalizing Trotsky. By 1929, Stalin had also effectively marginalized Zinoviev and Kamenev as well, compelling both to submit to his authority. The intransigent Trotsky was forced into exile.

When Boris Bazhanov, Stalin's personal secretary who had defected to France in 1928, produced a memoir critical of Stalin in 1930, he alleged that Stalin made crude antisemitic outbursts even before Lenin's death.

1930s

Stalin's 1931 condemnation of antisemitism

On 12 January 1931, Stalin gave the following answer to an inquiry on the subject of the Soviet attitude toward antisemitism from the Jewish News Agency in the United States:National and racial chauvinism is a vestige of the misanthropic customs characteristic of the period ofcannibalism Cannibalism is the act of consuming another individual of the same species as food. Cannibalism is a common ecological interaction in the animal kingdom and has been recorded in more than 1,500 species. Human cannibalism is well documented, b .... Anti-semitism, as an extreme form of racial chauvinism, is the most dangerous vestige of cannibalism. Anti-semitism is of advantage to the exploiters as alightning conductor A lightning rod or lightning conductor (British English) is a metal rod mounted on a structure and intended to protect the structure from a lightning strike. If lightning hits the structure, it will preferentially strike the rod and be conducte ...that deflects the blows aimed by the working people at capitalism. Anti-semitism is dangerous for the working people as being a false path that leads them off the right road and lands them in the jungle. Hence Communists, as consistent internationalists, cannot but be irreconcilable, sworn enemies of anti-semitism. In the U.S.S.R. anti-semitism is punishable with the utmost severity of the law as a phenomenon deeply hostile to the Soviet system. Under U.S.S.R. law active anti-semites are liable to the death penalty.Joseph Stalin

"Reply to an Inquiry of the Jewish News Agency in the United States".

''Works'', Vol. 13, July 1930 – January 1934. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, 1954. p. 30.

Establishment of Jewish Autonomous Oblast

To offset the growing Jewish national and religious aspirations ofZionism

Zionism ( he, צִיּוֹנוּת ''Tsiyyonut'' after '' Zion'') is a nationalist movement that espouses the establishment of, and support for a homeland for the Jewish people centered in the area roughly corresponding to what is known in Je ...

and to successfully categorize Soviet Jews under Stalin's nationality policy, an alternative to the Land of Israel

The Land of Israel () is the traditional Jewish name for an area of the Southern Levant. Related biblical, religious and historical English terms include the Land of Canaan, the Promised Land, the Holy Land, and Palestine (see also Isr ...

was established with the help of Komzet

Komzet (russian: Комитет по земельному устройству еврейских трудящихся, ) was the ''Committee for the Settlement of Toiling Jews on the Land'' (some English sources use the word "working" instead of ...

and OZET

OZET (russian: ОЗЕТ, Общество землеустройства еврейских трудящихся) was the public Society for Settling Toiling Jews on the Land in the Soviet Union in the period from 1925 to 1938. Some English sour ...

in 1928. The Jewish Autonomous Oblast

The Jewish Autonomous Oblast (JAO; russian: Евре́йская автоно́мная о́бласть, (ЕАО); yi, ייִדישע אװטאָנאָמע געגנט, ; )In standard Yiddish: , ''Yidishe Oytonome Gegnt'' is a federal subject ...

with the center in Birobidzhan

Birobidzhan ( rus, Биробиджа́н, p=bʲɪrəbʲɪˈdʐan; yi, ביראָבידזשאַן, ''Birobidzhan'') is a town and the administrative center of the Jewish Autonomous Oblast, Russia, located on the Trans-Siberian Railway, near th ...

in the Russian Far East

The Russian Far East (russian: Дальний Восток России, r=Dal'niy Vostok Rossii, p=ˈdalʲnʲɪj vɐˈstok rɐˈsʲiɪ) is a region in Northeast Asia. It is the easternmost part of Russia and the Asian continent; and is admin ...

was to become a "Soviet Zion". Yiddish

Yiddish (, or , ''yidish'' or ''idish'', , ; , ''Yidish-Taytsh'', ) is a West Germanic language historically spoken by Ashkenazi Jews. It originated during the 9th century in Central Europe, providing the nascent Ashkenazi community with a ve ...

, rather than "reactionary" Hebrew

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

, would be the national language

A national language is a language (or language variant, e.g. dialect) that has some connection—de facto or de jure—with a nation. There is little consistency in the use of this term. One or more languages spoken as first languages in the te ...

, and proletarian socialist literature and arts would replace Judaism as the quintessence of culture. Despite a massive domestic and international state propaganda campaign, the Jewish population there never reached 30% (as of 2003 it was only about 1.2%). The experiment ground to a halt in the mid-1930s, during Stalin's first campaign of purges, as local leaders were not spared during the purges.

Great Purge

Stalin's harshest period of mass repression, theGreat Purge

The Great Purge or the Great Terror (russian: Большой террор), also known as the Year of '37 (russian: 37-й год, translit=Tridtsat sedmoi god, label=none) and the Yezhovshchina ('period of Yezhov'), was Soviet General Secreta ...

(or Great Terror), was launched in 1936–1937 and involved the execution of over a half-million Soviet citizens accused of treason, terrorism, and other anti-Soviet

Anti-Sovietism, anti-Soviet sentiment, called by Soviet authorities ''antisovetchina'' (russian: антисоветчина), refers to persons and activities actually or allegedly aimed against the Soviet Union or government power within the ...

crimes. The campaign of purges prominently targeted Stalin's former opponents and other Old Bolsheviks

Old Bolshevik (russian: ста́рый большеви́к, ''stary bolshevik''), also called Old Bolshevik Guard or Old Party Guard, was an unofficial designation for a member of the Bolshevik faction of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Par ...

, and included a large-scale purge of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, repression of the ''kulak

Kulak (; russian: кула́к, r=kulák, p=kʊˈlak, a=Ru-кулак.ogg; plural: кулаки́, ''kulakí'', 'fist' or 'tight-fisted'), also kurkul () or golchomag (, plural: ), was the term which was used to describe peasants who owned ove ...

'' peasants, Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian language, Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist R ...

leaders, and ordinary citizens accused of conspiring against Stalin's administration. Figes, Orlando (2007). ''The Whisperers: Private Life in Stalin's Russia''. New York: Metropolitan. pp. 227–315 . Although many of Great Purge victims were ethnic or religious Jews, they were not specifically targeted as an ethnic group during this campaign according to Mikhail Baitalsky, Gennady Kostyrchenko, David Priestland, Jeffrey Veidlinger, Roy Medvedev

Roy Aleksandrovich Medvedev (russian: Рой Алекса́ндрович Медве́дев; born 14 November 1925) is a Russian political writer. He is the author of the dissident history of Stalinism, ''Let History Judge'' (russian: К с� ...

and Edvard Radzinsky

Edvard Stanislavovich Radzinsky (russian: Э́двард Станисла́вович Радзи́нский) (born September 23, 1936) is a Russian playwright, television personality, screenwriter, and the author of more than forty popular histor ...

.Edvard Radzinsky

Edvard Stanislavovich Radzinsky (russian: Э́двард Станисла́вович Радзи́нский) (born September 23, 1936) is a Russian playwright, television personality, screenwriter, and the author of more than forty popular histor ...

. ''Stalin'' (in Russian). Moscow, Vagrius, 1997. available online

Translated version: "Stalin", 1996, (hardcover), 1997, (paperback) Ch. 24

German–Soviet rapprochement and the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact

During his meeting with Nazi Germany's foreign ministerJoachim von Ribbentrop

Ulrich Friedrich Wilhelm Joachim von Ribbentrop (; 30 April 1893 – 16 October 1946) was a German politician and diplomat who served as Minister of Foreign Affairs of Nazi Germany from 1938 to 1945.

Ribbentrop first came to Adolf Hitler's not ...

, Stalin promised him to get rid of the "Jewish domination", especially among the intelligentsia. After dismissing Maxim Litvinov

Maxim Maximovich Litvinov (; born Meir Henoch Wallach; 17 July 1876 – 31 December 1951) was a Russian revolutionary and prominent Soviet statesman and diplomat.

A strong advocate of diplomatic agreements leading towards disarmament, Litvinov w ...

as Foreign Minister in 1939, Stalin immediately directed incoming Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov

Vyacheslav Mikhaylovich Molotov. ; (;. 9 March Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O._S._25_February.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O. S. 25 February">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dat ...

to "purge the ministry of Jews", to appease Hitler and to signal Nazi Germany that the USSR was ready for non-aggression talks.

Antisemitic trends in Stalin's policies were fueled by his struggle against Leon Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein. ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky; uk, link= no, Лев Давидович Троцький; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trotskij'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky''. (), was a Russian ...

and his global base of support.Etinger, Iakov (1995). "The Doctors' Plot: Stalin's Solution to the Jewish Question". In Yaacov Ro'i, ''Jews and Jewish Life in Russia and the Soviet Union''. London: Frank Cass. , pp. 103–6.

In the late 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s far fewer Jews were appointed to positions of power in the state apparatus than previously, with a sharp drop in Jewish representation in senior positions evident from around the time of the beginning of the late 1930s rapprochement with Nazi Germany. The percentage of Jews in positions of power dropped to 6% in 1938, and to 5% in 1940.Gennady Коstyrchenko "Stalin's secret policy: Power and Antisemitism"("Тайная политика Сталина. Власть и антисемитизм" Москва, "Международные отношения", 2003)

Relocation and deportation of Jews during the war

Following the Soviet invasion of Poland, Stalin began a policy of deporting Jews to theJewish Autonomous Oblast

The Jewish Autonomous Oblast (JAO; russian: Евре́йская автоно́мная о́бласть, (ЕАО); yi, ייִדישע אװטאָנאָמע געגנט, ; )In standard Yiddish: , ''Yidishe Oytonome Gegnt'' is a federal subject ...

and other parts of Siberia. Throughout the war, similar movements were executed in regions considered vulnerable to Nazi invasion with the various target ethnic groups of the Nazi genocide. When these populations reached their destinations, work was oftentimes arduous and they were subjected to poor conditions due to lack of resources caused by the war effort.

After World War II

The experience of theHolocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; ...

, which resulted in the murder of approximately six million Jews in Europe under Nazi occupation, and left millions more homeless and displaced, contributed to growing concern about the situation of the Jewish people worldwide. However, the trauma breathed new life into the traditional idea of a common Jewish peoplehood

Jewish peoplehood (Hebrew: עמיות יהודית, ''Amiut Yehudit'') is the conception of the awareness of the underlying unity that makes an individual a part of the Jewish people.

The concept of peoplehood has a double meaning. The first is d ...

and became a catalyst for the revival of the Zionist idea of creating a Jewish state in the Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabian Peninsula, Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Anatolia, Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Pro ...

.

The Jewish Autonomous Oblast experienced a revival as the Soviet government sponsored the migration of as many as 10,000 Eastern European Jews to Birobidzhan in 1946–1948.Weinberg, Robert (1998). ''Stalin's Forgotten Zion: Birobidzhan and the Making of a Soviet Jewish Homeland''. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 72–75. . In early 1946, the Council of Ministers of the USSR

The Council of Ministers of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics ( rus, Совет министров СССР, r=Sovet Ministrov SSSR, p=sɐˈvʲet mʲɪˈnʲistrəf ɛsɛsɛˈsɛr; sometimes abbreviated to ''Sovmin'' or referred to as the '' ...

announced a plan to build new infrastructure, and Mikhail Kalinin

Mikhail Ivanovich Kalinin (russian: link=no, Михаи́л Ива́нович Кали́нин ; 3 June 1946), known familiarly by Soviet citizens as "Kalinych", was a Soviet politician and Old Bolshevik revolutionary. He served as head of st ...

, a champion of the Birobidzhan project since the late 1920s, stated that he still considered the region to be a "Jewish national state" that could be revived through "creative toil."

Israel

From late 1944 onward,Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet Union, Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as Ge ...

adopted a pro-Zionist foreign policy, apparently believing that the new country would be socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the ...

and would speed the decline of British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

influence in the Middle East. Accordingly, in November 1947, the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

, together with the other Soviet bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc and the Soviet Bloc, was the group of socialist states of Central and Eastern Europe, East Asia, Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America under the influence of the Soviet Union that exist ...

countries voted in favor of the United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine

The United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine was a proposal by the United Nations, which recommended a partition of Mandatory Palestine at the end of the British Mandate. On 29 November 1947, the UN General Assembly adopted the Plan as R ...

, which paved the way for the creation of the State of Israel. On May 17, 1948, three days after Israel declared its independence, the Soviet Union officially granted ''de jure

In law and government, ''de jure'' ( ; , "by law") describes practices that are legally recognized, regardless of whether the practice exists in reality. In contrast, ("in fact") describes situations that exist in reality, even if not legall ...

'' recognition of Israel, becoming only the second country to recognise the Jewish state (preceded only by the United States' ''de facto

''De facto'' ( ; , "in fact") describes practices that exist in reality, whether or not they are officially recognized by laws or other formal norms. It is commonly used to refer to what happens in practice, in contrast with '' de jure'' ("by l ...

'' recognition) and the first country to grant Israel ''de jure'' recognition. In the 1948 Arab–Israeli War

The 1948 (or First) Arab–Israeli War was the second and final stage of the 1948 Palestine war. It formally began following the end of the British Mandate for Palestine at midnight on 14 May 1948; the Israeli Declaration of Independence had ...

, the Soviet Union supported Israel with weaponry supplied via Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

.

Nonetheless, Stalin began a new purge by repressing his wartime allies, the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee

The Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee, ''Yevreysky antifashistsky komitet'' yi, יידישער אנטי פאשיסטישער קאמיטעט, ''Yidisher anti fashistisher komitet''., abbreviated as JAC, ''YeAK'', was an organization that was created i ...

. In January 1948, Solomon Mikhoels

Solomon (Shloyme) Mikhoels ( yi, שלמה מיכאעלס lso spelled שלוימע מיכאעלס during the Soviet era russian: Cоломон (Шлойме) Михоэлс, – 13 January 1948) was a Latvian born Soviet Jewish actor and the art ...

was assassinated on Stalin's personal orders in Minsk

Minsk ( be, Мінск ; russian: Минск) is the capital and the largest city of Belarus, located on the Svislach (Berezina), Svislach and the now subterranean Nyamiha, Niamiha rivers. As the capital, Minsk has a special administrative stat ...

. His murder was disguised as a hit-and-run car accident. Mikhoels was taken to MGB dacha

A dacha ( rus, дача, p=ˈdatɕə, a=ru-dacha.ogg) is a seasonal or year-round second home, often located in the exurbs of post-Soviet countries, including Russia. A cottage (, ') or shack serving as a family's main or only home, or an outbu ...

and killed, along with his non-Jewish colleague Golubov-Potapov, under supervision of Stalin's Deputy Minister of State Security Sergei Ogoltsov

Sergei Ivanovich Ogoltsov (russian: Сергей Иванович Огольцов; 29 August 1900 – 30 December 1976

Stalin had Jewish in-laws and grandchildren. Some of Stalin's close associates were also Jews or had Jewish spouses, including Lazar Kaganovich, Maxim Litvinov, and Lev Mekhlis. Many of them were purged, including Nikolai Yezhov's wife and Polina Zhemchuzhina, who was

Stalin had Jewish in-laws and grandchildren. Some of Stalin's close associates were also Jews or had Jewish spouses, including Lazar Kaganovich, Maxim Litvinov, and Lev Mekhlis. Many of them were purged, including Nikolai Yezhov's wife and Polina Zhemchuzhina, who was

Korey, William. “The Origins and Development of Soviet Anti-Semitism: An Analysis.” Slavic Review, vol. 31, no. 1, 1972, pp. 111–135. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/2494148.Ginsburg, Michael. Reviewed Work: The Jews in the Soviet Union by Solomon M. Schwarz, Alvin Johnson, Syracuse University Press, 1951, ''Publications of the American Jewish Historical Society'', vol. 42, no. 4, 1953, pp. 442–449. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/43059911.András Kovács (ed.) Communism’s Jewish Question. Jewish Issues in Communist Archives, 2017, Walter de Gruyter. e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-041159-1

Stalin's Demise, Antisemitism, Katyn Archives Index

(introduction) by Joshua Rubenstein

50th anniversary of the Night of the Murdered Poets

National Coalition Supporting Soviet Jewry 12 August 2002, Letter from President Bush, links

Seven-fold Betrayal: The Murder of Soviet Yiddish

by Joseph Sherman

Unknown History, Unheroic Martyrs

by Jonathan Tobin

Не умри Сталин в 1953 году...

(If Stalin Had Not Died in 1953) by Yoav Karni (BBC in Russian language)

Russian political parties and antisemitism

*Mircea Rusnac, http://www.banaterra.eu/romana/rusnac-mircea-un-proces-stalinist-implicand-,,agenti-imperialisti%22-evrei-si-social-democrati {{DEFAULTSORT:Stalin's Antisemitism Antisemitism in the Soviet Union Jews and Judaism in the Soviet Union Joseph Stalin, Antisemitism Left-wing antisemitism Views of Judaism by individual

Robert Conquest

George Robert Acworth Conquest (15 July 1917 – 3 August 2015) was a British historian and poet.

A long-time research fellow at Stanford University's Hoover Institution, Conquest was most notable for his work on the Soviet Union. His books ...

. ''Reflections on a Ravaged Century'', Norton, (2000) , page 101

Despite Stalin's initial willingness to support Israel, various historians speculate that antisemitism in the late 1940s and early 1950s was motivated by Stalin's possible perception of Jews as a potential "fifth column

A fifth column is any group of people who undermine a larger group or nation from within, usually in favor of an enemy group or another nation. According to Harris Mylonas and Scott Radnitz, "fifth columns" are “domestic actors who work to un ...

" in light of a pro-Western Israel in the Middle East. Orlando Figes

Orlando Guy Figes () is a British historian and writer. Until his retirement, he was Professor of History at Birkbeck College, University of London.

Figes is known for his works on Russian history, such as '' A People's Tragedy'' (1996), ''Nata ...

suggests that "After the foundation of Israel in May 1948, and its alignment with the USA in the Cold War, the 2 million Soviet Jews, who had always remained loyal to the Soviet system, were portrayed by the Stalinist regime as a potential fifth column. Despite his personal dislike of Jews, Stalin had been an early supporter of a Jewish state in Palestine, which he had hoped to turn into a Soviet satellite in the Middle East. But as the leadership of the emerging state proved hostile to approaches from the Soviet Union, Stalin became increasingly afraid of pro-Israeli feeling among Soviet Jews. His fears intensified as a result of Golda Meir's arrival in Moscow in the autumn of 1948 as the first Israeli ambassador to the USSR. On her visit to a Moscow synagogue onHistorians Albert S. Lindemann and Richard S. Levy observe: "When, in October 1948, during the high holy days, thousands of Jews rallied around Moscow's central synagogue to honorYom Kippur Yom Kippur (; he, יוֹם כִּפּוּר, , , ) is the holiest day in Judaism and Samaritanism. It occurs annually on the 10th of Tishrei, the first month of the Hebrew calendar. Primarily centered on atonement and repentance, the day' ...(13 October), thousands of people lined the streets, many of them shouting ''Am Yisroel Chai!'' (The People of Israel Live!)a traditional affirmation of national renewal to Jews throughout the world but to Stalin a dangerous sign of 'bourgeois Jewish nationalism' that subverted the authority of the Soviet state."

Golda Meir

Golda Meir, ; ar, جولدا مائير, Jūldā Māʾīr., group=nb (born Golda Mabovitch; 3 May 1898 – 8 December 1978) was an Israeli politician, teacher, and '' kibbutznikit'' who served as the fourth prime minister of Israel from 1969 to ...

, the first Israeli ambassador, the authorities became especially alarmed at the signs of Jewish disaffection." Jeffrey Veidlinger writes: "By October 1948, it was obvious that Mikhoels was by no means the sole advocate of Zionism among Soviet Jews. The revival of Jewish cultural expression during the war had fostered a general sense of boldness among the Jewish masses. Many Jews remained oblivious to the growing Zhdanovshchina and the threat to Soviet Jews that the brewing campaign against " rootless cosmopolitans" signaled. Indeed, official attitudes toward Jewish culture were ambivalent during this period. On the surface, Jewish culture seemed to be supported by the state: public efforts had been made to sustain the Yiddish theater after Mikhoels's death, '' Eynikayt'' was still publishing on schedule, and, most important, the Soviet Union recognized the establishment of a Jewish state in Palestine. To most Moscow Jews, the state of Soviet Jewry had never been better."

Purges

In November 1948, Soviet authorities launched a campaign to liquidate what was left of Jewish culture. The leading members of theJewish Anti-Fascist Committee

The Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee, ''Yevreysky antifashistsky komitet'' yi, יידישער אנטי פאשיסטישער קאמיטעט, ''Yidisher anti fashistisher komitet''., abbreviated as JAC, ''YeAK'', was an organization that was created i ...

were arrested. They were charged with treason, bourgeois nationalism

In Marxism, bourgeois nationalism is the practice by the ruling classes of deliberately dividing people by nationality, race, ethnicity, or religion, so as to distract them from engaging in class struggle. It is seen as a divide-and-conquer stra ...

, and planning to set up a Jewish republic in Crimea

Crimea, crh, Къырым, Qırım, grc, Κιμμερία / Ταυρική, translit=Kimmería / Taurikḗ ( ) is a peninsula in Ukraine, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, that has been occupied by Russia since 2014. It has a p ...

to serve American interests. The Museum of Environmental Knowledge of the Jewish Autonomous Oblast (established in November 1944) and The Jewish Museum in Vilnius (established at the end of the war) were closed in 1948.Pinkus, Benjamin (1990). ''The Jews of the Soviet Union: The History of a National Minority''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 205. . The Historical-Ethnographic Museum of Georgian Jewry, established in 1933, was shut down at the end of 1951.

In Birobidzhan, the various Jewish cultural institutions that had been established under Stalin's earlier policy of support for "proletarian Jewish culture" in the 1930s were closed between late 1948 and early 1949. These included the Kaganovich Yiddish Theater, the Yiddish publishing house, the Yiddish newspaper ''Birobidzhan'', the library of Yiddish and Hebrew books, and the local Jewish schools. The same happened to Yiddish theaters all over the Soviet Union, beginning with the Odessa Yiddish Theater and including the Moscow State Jewish Theater.

In early February 1949, the Stalin Prize Stalin Prize may refer to:

* The State Stalin Prize in science and engineering and in arts, awarded 1941 to 1954, later known as the USSR State Prize

The USSR State Prize (russian: links=no, Государственная премия СССР, ...

-winning microbiologist

A microbiologist (from Greek ) is a scientist who studies microscopic life forms and processes. This includes study of the growth, interactions and characteristics of microscopic organisms such as bacteria, algae, fungi, and some types of para ...

Nikolay Gamaleya, a pioneer of bacteriology Bacteriology is the branch and specialty of biology that studies the morphology, ecology, genetics and biochemistry of bacteria as well as many other aspects related to them. This subdivision of microbiology involves the identification, classificat ...

and member of the Academy of Sciences

An academy of sciences is a type of learned society or academy (as special scientific institution) dedicated to sciences that may or may not be state funded. Some state funded academies are tuned into national or royal (in case of the Unit ...

, wrote a personal letter to Stalin, protesting the growing antisemitism: "Judging by absolutely indisputable and obvious indications, the reappearance of antisemitism is not coming from below, not from the masses. . . but is directed from above, by someone's invisible hand. Antisemitism is coming from some high-placed persons who have taken up posts in the leading party organs." The ninety-year-old scientist wrote to Stalin again in mid-February, again mentioning the growing antisemitism. In March, Gamaleya died, still having received no answer.Vaksberg, Arkady (2003). ''Iz ada v ray i obratno: yevreyskiy vopros po Leninu, Stalinu i Solzhenitsynu''. Moscow: Olimp. pp. 344–346. .

During the night of 12–13 August 1952, remembered as the "Night of the Murdered Poets

The Night of the Murdered Poets (; yi, הרוגי מלכות פֿונעם ראַטנפאַרבאַנד, translit=Harugey malkus funem Ratnfarband, lit=Soviet Union Martyrs) was the execution of thirteen Soviet Jews in the Lubyanka Prison in Mosco ...

" (Ночь казнённых поэтов), thirteen of the most prominent Yiddish

Yiddish (, or , ''yidish'' or ''idish'', , ; , ''Yidish-Taytsh'', ) is a West Germanic language historically spoken by Ashkenazi Jews. It originated during the 9th century in Central Europe, providing the nascent Ashkenazi community with a ve ...

writers of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

were executed on the orders of Stalin. Among the victims were Peretz Markish

Peretz Davidovich Markish ( yi, פּרץ מאַרקיש ) (russian: Перец Давидович Маркиш) (7 December 1895 (25 November OS) – 12 August 1952) was a Russian Jewish poet and playwright who wrote predominantly in Yiddish.

...

, David Bergelson

David (or Dovid) Bergelson (, russian: Давид Бергельсон, 12 August 1884 – 12 August 1952) was a Yiddish language writer born in the Russian Empire. He lived for a time in Berlin, Germany before moving to the Soviet Union following ...

and Itzik Fefer

Itzik Feffer (10 September 1900 – 12 August 1952), also Fefer (Yiddish איציק פֿעפֿער, Russian Ицик Фефер, Исаàк Соломòнович Фèфер) was a Soviet Yiddish poet executed on the Night of the Murdered Poet ...

.

In a 1 December 1952 Politburo session, Stalin announced: "Every Jewish nationalist is the agent of the American intelligence service. Jewish nationalists think that their nation was saved by the USA. . . They think they are indebted to the Americans. Among doctors, there are many Jewish nationalists." He also quoted Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; 28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) was a Genevan philosopher, writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment throughout Europe, as well as aspects of the French Revolu ...

's "eat the rich" in this speech..

A notable campaign to quietly remove Jews from positions of authority within the state security services was carried out in 1952–1953. The Russian historians Zhores and Roy Medvedev

Roy Aleksandrovich Medvedev (russian: Рой Алекса́ндрович Медве́дев; born 14 November 1925) is a Russian political writer. He is the author of the dissident history of Stalinism, ''Let History Judge'' (russian: К с� ...

wrote that according to MVD General Sudoplatov, "simultaneously all Jews were removed from the leadership of the security services, even those in very senior positions. In February the anti-Jewish expulsions were extended to regional branches of the MGB. A secret directive was distributed to all regional directorates of the MGB on 22 February, ordering that all Jewish employees of the MGB be dismissed immediately, regardless of rank, age or service record. . . ."

The outside world was not ignorant of these developments, and even the leading members of the Communist Party USA

The Communist Party USA, officially the Communist Party of the United States of America (CPUSA), is a communist party in the United States which was established in 1919 after a split in the Socialist Party of America following the Russian Rev ...

complained about the situation. In the memoir ''Being Red'', the American writer and prominent Communist Howard Fast recalls a meeting with Soviet writer and World Peace Congress

The World Peace Congress, founded by Professor Rajani Kannepalli Kanth in 2007, is a non-governmental organization dedicated to constructing an institutional basis for world peace, unmediated by state, government or politics. The Congress hold ...

delegate Alexander Fadeyev during this time. Fadeyev insisted that "There is no anti-Semitism in the Soviet Union", despite the evidence "that at least eight leading Jewish figures in the Red Army and in government had been arrested on what appeared to be trumped-up charges. Yiddish-language newspapers had been suppressed. Schools that taught Hebrew had been closed."

Doctors' plot

In secondary evidence and memoirs, there is a view that the Doctors' plot case was intended to trigger mass repressions and deportations of the Jews, similar to the population transfer in the Soviet Union of many other ethnic minorities, but the plan was not accomplished because of the sudden death of Stalin. Zhores Medvedev wrote that there are no documents found in support of the deportation plan, and Gennady Kostyrchenko writes the same. Nevertheless, the question remains open. According to Louis Rapoport, the genocide was planned to start with the public execution of the imprisoned doctors, and then the "following incidents would follow", such as "attacks on Jews orchestrated by the secret police, the publication of the statement by the prominent Jews, and a flood of other letters demanding that action be taken. A three-stage program of genocide would be followed. First, almost all Soviet Jews ... would be shipped to camps east of the Urals ... Second, the authorities would set Jewish leaders at all levels against one another ... Also the MGB [Secret Police] would start killing the elites in the camps, just as they had killed the Yiddish writers ... the previous year. The ... final stage would be to 'get rid of the rest.'" Four large camps were built in southern and western Siberia shortly before Stalin's death in 1953, and there were rumors that they were for Jews.#refBrentNaumov2003, Brent & Naumov 2003, p. 295. A special Deportation Commission to plan the deportation of Jews to these camps was allegedly created.#refBrentNaumov2003, Brent & Naumov 2003, pp. 47–48, 295.Eisenstadt, Yaakov, ''Stalin's Planned Genocide'', 22 Adar 5762, March 6, 2002. Nikolay Poliakov, the secretary of the Deportation Commission, stated years later that according to Stalin's initial plan the deportation was to begin in the middle of February 1953, but the monumental task of compiling lists of Jews had not yet been completed. "Pure blooded" Jews were to be deported first, followed by "Half-Jewish, half-breeds" (''polukrovki''). Before his death in March 1953, Stalin allegedly had planned the execution of Doctors' plot defendants already on trial in Red Square in March 1953, and then he would cast himself as the savior of Soviet Jews by sending them to camps away from the purportedly enraged Russian populace.#refBrentNaumov2003, Brent & Naumov 2003, pp. 298–300. There are further statements that describe some aspects of such a planned deportation. Similar purges against Jews were organised in the Eastern Bloc countries, such as with the Prague Trials. During this time, Soviet Jews were dubbed Person of Jewish ethnicity, persons of Jewish ethnicity. A dean of the Marxism–Leninism department at a Soviet university explained the policy to his students: "One of you asked if our current political campaign can be regarded as antisemitic. Comrade Stalin said: "We hate Nazis not because they are Germans, but because they brought enormous suffering to our land. Same can be said about the Jews."Benedikt Sarnov,''Our Soviet Newspeak: A Short Encyclopedia of Real Socialism.'', Moscow: 2002, (Наш советский новояз. Маленькая энциклопедия реального социализма.), "Persons of Jewish ethnicity", pages 287–293. It has also been said that at the time of Stalin's death, "no Jew in Russia could feel safe." Throughout this time, the Soviet media avoided overt antisemitism and continued to report the punishment of officials for antisemitic behavior.Associates and family

Stalin had Jewish in-laws and grandchildren. Some of Stalin's close associates were also Jews or had Jewish spouses, including Lazar Kaganovich, Maxim Litvinov, and Lev Mekhlis. Many of them were purged, including Nikolai Yezhov's wife and Polina Zhemchuzhina, who was

Stalin had Jewish in-laws and grandchildren. Some of Stalin's close associates were also Jews or had Jewish spouses, including Lazar Kaganovich, Maxim Litvinov, and Lev Mekhlis. Many of them were purged, including Nikolai Yezhov's wife and Polina Zhemchuzhina, who was Vyacheslav Molotov

Vyacheslav Mikhaylovich Molotov. ; (;. 9 March Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O._S._25_February.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O. S. 25 February">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dat ...

's wife, and also Bronislava Poskrebysheva. Historian Geoffrey Roberts points out that Stalin "continued to fête Jewish writers and artists even at the height of the anti-Zionist campaign of the early 1950s." However, when Stalin's young daughter Svetlana Alliluyeva, Svetlana fell in love with prominent Soviet filmmaker Aleksei Kapler, Alexei Kapler, a Jewish man twenty-three years her elder, Stalin was strongly irritated by the relationship. According to Svetlana, Stalin "was irritated more than anything else by the fact that Kapler was Jewish." Kapler was convicted to ten years of hard labor in Gulag on the charges of being an "English spy." Stalin's daughter later fell in love with Grigori Morozov, another Jew, and married him. Stalin agreed to their marriage after much pleading on Svetlana's part, but refused to attend the wedding. Stalin's son Yakov Dzhugashvili, Yakov also married a Jewish woman, Yulia Meltzer, and though Stalin disapproved at first, he began to grow fond of her. Stalin's biographer Simon Sebag Montefiore wrote that Lavrenty Beria's son noted that his father could list Stalin's affairs with Jewish women.Sebag-Montefiore, Simon (2005). ''Stalin: The Court of the Red Tsar''. New York: Random House. p. 267. .

In his memoirs, Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and chairman of the country's Council of Ministers from 1958 to 1964. During his rule, Khrushchev s ...

wrote: "A hostile attitude toward the Jewish nation was a major shortcoming of Stalin's. In his speeches and writings as a leader and theoretician there wasn't even a hint of this. God forbid that anyone assert that a statement by him smacked of antisemitism. Outwardly everything looked correct and proper. But in his inner circle, when he had occasion to speak about some Jewish person, he always used an emphatically distorted pronunciation. This was the way backward people lacking in political consciousness would express themselves in daily lifepeople with a contemptuous attitude toward Jews. They would deliberately mangle the Russian language, putting on a Jewish accent or imitating certain negative characteristics [attributed to Jews]. Stalin loved to do this, and it became one of his characteristic traits." Khrushchev further professed that Stalin frequently made antisemitic comments after World War II.

Analyzing various explanations for Stalin's perceived antisemitism in his book ''The Lesser Terror: Soviet State Security, 1939–1953'', historian Michael Parrish wrote: "It has been suggested that Stalin, who remained first and foremost a Georgians, Georgian throughout his life, somehow became a 'Russian nationalism, Great Russian' and decided that Jews would make a scapegoat for the ills of the Soviet Union. Others, such as the Polish writer Aleksander Wat (himself a victim), claim that Stalin was not an antisemite by nature, but the pro-Americanism of Soviet Jews forced him to follow a deliberate policy of antisemitism. Wat's views are, however, colored by the fact that Stalin, for obvious reasons, at first depended on Jewish Communists to help carry out his post-war policies in Poland. I believe a better explanation was Stalin's sense of envy, which consumed him throughout his life. He also found in Jews a convenient target. By late 1930, Stalin, as [his daughter's] memoirs indicate, was suffering from a full-blown case of antisemitism."

In ''Esau's Tears: Modern Anti-Semitism and the Rise of the Jews'', historian Albert S. Lindemann wrote: "Determining Stalin's real attitude to Jews is difficult. Not only did he repeatedly speak out against anti-Semitism but both his son and daughter married Jews, and several of his closest and most devoted lieutenants from the late 1920s through the 1930s were of Jewish origin, for example Lazar Moiseyevich Kaganovich, Maxim Litvinov

Maxim Maximovich Litvinov (; born Meir Henoch Wallach; 17 July 1876 – 31 December 1951) was a Russian revolutionary and prominent Soviet statesman and diplomat.

A strong advocate of diplomatic agreements leading towards disarmament, Litvinov w ...

, and the notorious head of the secret police, Genrikh Yagoda. There were not so many Jews allied with Stalin on the party's right as there were allied with Trotsky on the left, but the importance of men like Kaganovich, Litvinov, and Yagoda makes it hard to believe that Stalin harbored a categorical hatred of all Jews, as a race, in the way that Hitler did. Scholars as diverse in their opinions as Isaac Deutscher and Robert Conquest

George Robert Acworth Conquest (15 July 1917 – 3 August 2015) was a British historian and poet.

A long-time research fellow at Stanford University's Hoover Institution, Conquest was most notable for his work on the Soviet Union. His books ...

have denied that anything as crude and dogmatic as Nazi-style anti-Semitism motivated Stalin. It may be enough simply to note that Stalin was a man of towering hatreds, corrosive suspicions, and impenetrable duplicity. He saw enemies everywhere, and it just so happened that many of his enemiesvirtually all his enemies—were Jews, above all, ''the'' enemy, Trotsky." Lindemann added that "Jews in the party were often verbally adroit, polylingual, and broadly educated—all qualities Stalin lacked. To observe, as his daughter Svetlana has, that 'Stalin did not like Jews,' does not tell us much, since he 'did not like' any group: His hatreds and suspicions knew no limits; even party members from his native Georgia (country), Georgia were not exempt. Whether he hated Jews with a special intensity or quality is not clear."Lindemann, Albert (2000). ''Esau's Tears: Modern Anti-Semitism and the Rise of the Jews''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 454. .

See also

*History of the Jews in the Soviet Union *''The Hitler Book'' *Population transfer in the Soviet Union *Soviet Anti-Zionism *Soviet pro-Arab propaganda *Antisemitism in the Soviet UnionReferences

Further reading

*Arkady Vaksberg (1994). ''Stalin Against The Jews'', tr. Antonina Bouis. *Louis Rapoport (1990). ''Stalin's War Against the Jews''. *Emil Draitser (2008). ''Shush! Growing up Jewish under Stalin''.Korey, William. “The Origins and Development of Soviet Anti-Semitism: An Analysis.” Slavic Review, vol. 31, no. 1, 1972, pp. 111–135. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/2494148.

External links

Stalin's Demise, Antisemitism, Katyn Archives Index

(introduction) by Joshua Rubenstein

50th anniversary of the Night of the Murdered Poets

National Coalition Supporting Soviet Jewry 12 August 2002, Letter from President Bush, links

Seven-fold Betrayal: The Murder of Soviet Yiddish

by Joseph Sherman

Unknown History, Unheroic Martyrs

by Jonathan Tobin

Не умри Сталин в 1953 году...

(If Stalin Had Not Died in 1953) by Yoav Karni (BBC in Russian language)

Russian political parties and antisemitism

*Mircea Rusnac, http://www.banaterra.eu/romana/rusnac-mircea-un-proces-stalinist-implicand-,,agenti-imperialisti%22-evrei-si-social-democrati {{DEFAULTSORT:Stalin's Antisemitism Antisemitism in the Soviet Union Jews and Judaism in the Soviet Union Joseph Stalin, Antisemitism Left-wing antisemitism Views of Judaism by individual