St Giles In The Fields on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

St Giles in the Fields is the

During the 12th Century

The famous scene of the meeting of the Lollards at St Giles Fields was later memorialised by Alfred, Lord Tennyson, Lord Tennyson in his poem ''Sir John Oldcastle, Lord Cobham'':

"What did he say,

My frighted Wiclif-preacher whom I crost

In flying hither? that one night a crowd

Throng'd the waste field about the city gates:

The king was on them suddenly with a host.

Why there? they came to hear their preacher. "

According to an order of the

By the second decade of the 17th century the Medieval church had suffered a series of collapses and the parishioners decided to erect a new church which was begun 1623 and completed in 1630. It was consecrated on 26 January 1630. mostly paid for by the Duchess of Dudley, wife of Sir Robert Dudley. The 'poor players of

By the second decade of the 17th century the Medieval church had suffered a series of collapses and the parishioners decided to erect a new church which was begun 1623 and completed in 1630. It was consecrated on 26 January 1630. mostly paid for by the Duchess of Dudley, wife of Sir Robert Dudley. The 'poor players of

The Rector would spend the next sixteen years reforming and reconstituting the parish from the disorder of the post civil war period. He preached regularly (at least twice every Sunday at St Giles as well as weekly in other city churches) and with 'much fluency, piety ndgravity', becoming, according to

The Rector would spend the next sixteen years reforming and reconstituting the parish from the disorder of the post civil war period. He preached regularly (at least twice every Sunday at St Giles as well as weekly in other city churches) and with 'much fluency, piety ndgravity', becoming, according to

A memorial for the seven Jesuits and all those buried within the churchyard was unveiled on 20 January 2019.

Fr Lawrence Lew O.P. of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Westminster has described the place thus:

"The churchyard of St Giles may appear to the casual passer-by as a convenient green space to sit down, enjoy a sandwich and catch up with the social media. In actual fact it is one of London's most hallowed spots, with the remains of eleven beatified martyrs hidden beneath the ground, silently witnessing to the faith and awaiting the day of resurrection."

A memorial for the seven Jesuits and all those buried within the churchyard was unveiled on 20 January 2019.

Fr Lawrence Lew O.P. of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Westminster has described the place thus:

"The churchyard of St Giles may appear to the casual passer-by as a convenient green space to sit down, enjoy a sandwich and catch up with the social media. In actual fact it is one of London's most hallowed spots, with the remains of eleven beatified martyrs hidden beneath the ground, silently witnessing to the faith and awaiting the day of resurrection."

Distinguished people with memorials in St Giles include:

*Richard Penderell, Richard Penderel, Roman Catholic yeoman forester who accompanied king Charles II of England, Charles II on his famous Escape of Charles II, escape from the Battle of Worcester

*John Belasyse, 1st Baron Belasyse, Lord Belasyse, a noted Roman Catholic

Distinguished people with memorials in St Giles include:

*Richard Penderell, Richard Penderel, Roman Catholic yeoman forester who accompanied king Charles II of England, Charles II on his famous Escape of Charles II, escape from the Battle of Worcester

*John Belasyse, 1st Baron Belasyse, Lord Belasyse, a noted Roman Catholic

St Giles in the Fields is the custodian of the White Ensign flown by HMS Indefatigable (R10), HMS Indefatigable at the taking of the Surrender of Japan, Japanese surrender in Tokyo Bay on 5th September 1945. HMS Indefatigable was the adopted ship of Metropolitan Borough of Holborn. Following a request by the HMS Indefatigable association in 1989 the London Borough of Camden (which had succeeded the Holborn in 1965) agreed the laying up of the ensign in St Giles in the presence of the ship's company from the Second World War.

St Giles in the Fields is the custodian of the White Ensign flown by HMS Indefatigable (R10), HMS Indefatigable at the taking of the Surrender of Japan, Japanese surrender in Tokyo Bay on 5th September 1945. HMS Indefatigable was the adopted ship of Metropolitan Borough of Holborn. Following a request by the HMS Indefatigable association in 1989 the London Borough of Camden (which had succeeded the Holborn in 1965) agreed the laying up of the ensign in St Giles in the presence of the ship's company from the Second World War.

Church's own site

{{DEFAULTSORT:Saint Giles in the Fields 18th-century Church of England church buildings Church of England church buildings in the London Borough of Camden Diocese of London Grade I listed churches in London Neoclassical architecture in London Rebuilt churches in the United Kingdom St Giles, London Neoclassical church buildings in England

Anglican

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of th ...

parish church

A parish church (or parochial church) in Christianity is the church which acts as the religious centre of a parish. In many parts of the world, especially in rural areas, the parish church may play a significant role in community activities, ...

of the St Giles

Saint Giles (, la, Aegidius, french: Gilles), also known as Giles the Hermit, was a hermit or monk active in the lower Rhône most likely in the 6th century. Revered as a saint, his cult became widely diffused but his hagiography is mostly lege ...

district of London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

. It stands within the London Borough of Camden

The London Borough of Camden () is a London borough in Inner London. Camden Town Hall, on Euston Road, lies north of Charing Cross. The borough was established on 1 April 1965 from the area of the former boroughs of Hampstead, Holborn, and St ...

and belongs to the Diocese of London

The Diocese of London forms part of the Church of England's Province of Canterbury in England.

It lies directly north of the Thames. For centuries the diocese covered a vast tract and bordered the dioceses of Norwich and Lincoln to the north ...

. The church, named for St Giles the Hermit, began as a monastery

A monastery is a building or complex of buildings comprising the domestic quarters and workplaces of monastics, monks or nuns, whether living in communities or alone (hermits). A monastery generally includes a place reserved for prayer which ...

and leper hospital

A leper colony, also known by many other names, is an isolated community for the quarantining and treatment of lepers, people suffering from leprosy. ''M. leprae'', the bacterium responsible for leprosy, is believed to have spread from East Afr ...

and now gives its name to the surrounding district of St Giles in the West End of London between Seven Dials, Bloomsbury

Bloomsbury is a district in the West End of London. It is considered a fashionable residential area, and is the location of numerous cultural, intellectual, and educational institutions.

Bloomsbury is home of the British Museum, the largest mus ...

, Holborn

Holborn ( or ) is a district in central London, which covers the south-eastern part of the London Borough of Camden and a part ( St Andrew Holborn Below the Bars) of the Ward of Farringdon Without in the City of London.

The area has its roots ...

and Soho

Soho is an area of the City of Westminster, part of the West End of London. Originally a fashionable district for the aristocracy, it has been one of the main entertainment districts in the capital since the 19th century.

The area was develop ...

. The present church is the third on the site since the parish was founded in 1101. It was rebuilt most recently in 1731–1733 in Palladian

Palladian architecture is a European architectural style derived from the work of the Venetian architect Andrea Palladio (1508–1580). What is today recognised as Palladian architecture evolved from his concepts of symmetry, perspective and ...

style to designs by the architect Henry Flitcroft

Henry Flitcroft (30 August 1697 – 25 February 1769) was a major English architect in the second generation of Palladianism. He came from a simple background: his father was a labourer in the gardens at Hampton Court and he began as a joiner by t ...

.

History

Medieval Hospital and Chapel

The first recorded church on the site was achapel

A chapel is a Christian place of prayer and worship that is usually relatively small. The term has several meanings. Firstly, smaller spaces inside a church that have their own altar are often called chapels; the Lady chapel is a common ty ...

of the Parish of Holborn attached to a monastery and leper hospital founded by Matilda of Scotland

Matilda of Scotland (originally christened Edith, 1080 – 1 May 1118), also known as Good Queen Maud, or Matilda of Blessed Memory, was Queen of England and Duchess of Normandy as the first wife of King Henry I. She acted as regent of England ...

, consort of Henry I Henry I may refer to:

876–1366

* Henry I the Fowler, King of Germany (876–936)

* Henry I, Duke of Bavaria (died 955)

* Henry I of Austria, Margrave of Austria (died 1018)

* Henry I of France (1008–1060)

* Henry I the Long, Margrave of the ...

, in 1101. At the time it stood well outside the City of London

The City of London is a city, ceremonial county and local government district that contains the historic centre and constitutes, alongside Canary Wharf, the primary central business district (CBD) of London. It constituted most of London fr ...

and distant from the Royal Palace of Westminster

The Palace of Westminster serves as the meeting place for both the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two houses of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Informally known as the Houses of Parli ...

, on the main road to Tyburn

Tyburn was a manor (estate) in the county of Middlesex, one of two which were served by the parish of Marylebone.

The parish, probably therefore also the manor, was bounded by Roman roads to the west (modern Edgware Road) and south (modern Ox ...

and Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

. The chapel probably began to function as the church of a hamlet

''The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark'', often shortened to ''Hamlet'' (), is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare sometime between 1599 and 1601. It is Shakespeare's longest play, with 29,551 words. Set in Denmark, the play depicts ...

that grew up round the hospital. Although there is no record of any presentation to the living

Living or The Living may refer to:

Common meanings

*Life, a condition that distinguishes organisms from inorganic objects and dead organisms

** Living species, one that is not extinct

*Personal life, the course of an individual human's life

* ...

before the hospital was suppressed in 1539, the fact that the parish

A parish is a territorial entity in many Christian denominations, constituting a division within a diocese. A parish is under the pastoral care and clerical jurisdiction of a priest, often termed a parish priest, who might be assisted by one or m ...

of St. Giles was in existence at least as early as 1222 means that the church was at least partially used for parochial purposes from that time.

St Giles's position half way between the ancient cities of Westminster

Westminster is an area of Central London, part of the wider City of Westminster.

The area, which extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street, has many visitor attractions and historic landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, Bu ...

and London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

is perhaps no coincidence. As George Water Thornbury noted in London Old & New "it is remarkable that in almost every ancient town in England, the church of St. Giles stands either outside the walls, or, at all events, near its outlying parts, in allusion, doubtless, to the arrangements of the Israelites of old, who placed their lepers outside the campDuring the 12th Century

Pope Alexander IV

Pope Alexander IV (1199 or 1185 – 25 May 1261) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 12 December 1254 to his death in 1261.

Early career

He was born as Rinaldo di Jenne in Jenne (now in the Province of Rome), he ...

confirmed the Hospital's privileges and granted it his special protection. His bull

A bull is an intact (i.e., not castrated) adult male of the species ''Bos taurus'' (cattle). More muscular and aggressive than the females of the same species (i.e., cows), bulls have long been an important symbol in many religions,

includin ...

reveals that the lepers were trying to live as a religious community and that the hospital precinct included gardens and 8 acres of land adjoining the hospital to the north and south. A result of this Papal confirmation and protection, the religious community at St Giles's was exempted from the suspension of communion which occurred during the Papal Interdict

In Catholic canon law, an interdict () is an ecclesiastical censure, or ban that prohibits persons, certain active Church individuals or groups from participating in certain rites, or that the rites and services of the church are banished from ...

of England in 1208–14. This means that the site had been a sight of unbroken Christian worship for over 900 years when the church closed for a period during the national Covid-19 Lockdown.

The hospital was supported by the Crown and administered by the City of London for its first 200 years, being known as a Royal Peculiar

A royal peculiar is a Church of England parish or church exempt from the jurisdiction of the diocese and the province in which it lies, and subject to the direct jurisdiction of the monarch, or in Cornwall by the duke.

Definition

The church par ...

. In 1299, Edward I assigned it to Hospital of Burton Lazars in Leicestershire

Leicestershire ( ; postal abbreviation Leics.) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in the East Midlands, England. The county borders Nottinghamshire to the north, Lincolnshire to the north-east, Rutland to the east, Northamptonshire t ...

, a house of the order of St. Lazarus of Jerusalem, a chivalric order

An order of chivalry, order of knighthood, chivalric order, or equestrian order is an order (distinction), order of knights, typically founded during or inspired by the original Catholic Military order (religious society), military orders of the ...

from the era of the Crusades

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The best known of these Crusades are those to the Holy Land in the period between 1095 and 1291 that were in ...

. The 14th century was turbulent for the hospital, with frequent accusations of corruption and mismanagement from the City and Crown authorities and suggestions that members of the Order of Saint Lazarus (known as ''Lazar brothers)'' put the affairs of the monastery ahead of caring for the lepers. In 1348 The Citizens contended to the King that since the Master and brothers of Burton Lazars had taken over St. Giles's the friars had ousted the lepers and replaced them by brothers and sisters of the Order of St. Lazarus, who were not diseased and ought not to associate with those who were. The hospital appears to have been governed by a Warden, who was subordinate to the Master of Burton Lazars. The King intervened on several occasions and appointed a new head of the hospital.

Eventually, in 1391, Richard II sold the hospital, chapel and lands to the Cistercian

The Cistercians, () officially the Order of Cistercians ( la, (Sacer) Ordo Cisterciensis, abbreviated as OCist or SOCist), are a Catholic religious order of monks and nuns that branched off from the Benedictines and follow the Rule of Saint ...

abbey of St Mary de Graces by the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is separa ...

. This was opposed by the Lazars and their new Master, Walter Lynton, who responded by leading a group of armed men to St Giles, recapturing it by force, and by the City of London, which withheld rent money in protest. The dispute was finally settled in court with the King claiming he had been misled about the ownership of St Giles and recognising Lynton as legal Master of St Giles Hospital and the Hospital of Burton Lazarus.

The property at the time included of farmland and a survey-enumerated eight horses, twelve oxen, two cows, 156 pigs, 60 geese and 186 domestic fowl. The grant was revoked in 1402 and the property returned to the Lazars. Lepers were cared for there until the mid-16th century, when the disease abated and the monastery took to caring for indigents instead. The Precinct of the Hospital probably included the whole of the site now bounded by St Giles High Street, Charing Cross Road

Charing Cross Road is a street in central London running immediately north of St Martin-in-the-Fields to St Giles Circus (the intersection with Oxford Street) and then becomes Tottenham Court Road. It leads from the north in the direction of ...

and Shaftesbury Avenue

Shaftesbury Avenue is a major road in the West End of London, named after The 7th Earl of Shaftesbury. It runs north-easterly from Piccadilly Circus to New Oxford Street, crossing Charing Cross Road at Cambridge Circus. From Piccadilly Cir ...

; it was entered by a Gatehouse

A gatehouse is a type of fortified gateway, an entry control point building, enclosing or accompanying a gateway for a town, religious house, castle, manor house, or other fortification building of importance. Gatehouses are typically the mo ...

in St Giles High Street.

Lollardy and Oldcastle's Rising

In 1414, St Giles Fields served as the centre ofSir John Oldcastle

''Sir John Oldcastle'' is an Elizabethan play about John Oldcastle, a controversial 14th-/15th-century rebel and Lollard who was seen by some of Shakespeare's contemporaries as a proto-Protestant martyr.

Publication

The play was originally p ...

's abortive proto-Protestant Lollard uprising directed against the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

and the English king Henry V. In anticipation of Protestantism

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to b ...

, Lollard beliefs were outlined in the 1395 The Twelve Conclusions of the Lollards

The Twelve Conclusions of the Lollards is a Middle English religious text containing statements by leaders of the English medieval movement, the Lollards, inspired by teachings of John Wycliffe. The Conclusions were written in 1395. The text was pr ...

which dealt with, among other things, their opposition to capital punishment

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that t ...

, rejection of religious celibacy and belief that members of the clergy should be held accountable to civil laws. Rebel Lollards

Lollardy, also known as Lollardism or the Lollard movement, was a proto-Protestant Christian religious movement that existed from the mid-14th century until the 16th-century English Reformation. It was initially led by John Wycliffe, a Catholic ...

answered a summons to assemble among the 'dark thickets' by St. Giles's Fields on the night of Jan. 9, 1414. The King, however, was forewarned by his agents and the small group of Lollards

Lollardy, also known as Lollardism or the Lollard movement, was a proto-Protestant Christian religious movement that existed from the mid-14th century until the 16th-century English Reformation. It was initially led by John Wycliffe, a Catholic ...

in assembly were captured or dispersed. The rebellion brought severe reprisals and marked the end of the Lollards' overt political influence and many of the captured rebels were executed. 38 were dragged on hurdles through the streets from Newgate to St Giles on January 12, and hanged side by side in batches of four and the bodies of seven who had been condemned as heretics

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important religi ...

by the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

were burned afterwards. Four more were hanged a week later. On 14 December 1417 Sir John Oldcastle

''Sir John Oldcastle'' is an Elizabethan play about John Oldcastle, a controversial 14th-/15th-century rebel and Lollard who was seen by some of Shakespeare's contemporaries as a proto-Protestant martyr.

Publication

The play was originally p ...

himself was hanged in chains

A gibbet is any instrument of public execution (including guillotine, executioner's block, impalement stake, hanging gallows, or related scaffold). Gibbeting is the use of a gallows-type structure from which the dead or dying bodies of crimi ...

and burnt 'gallows and all' in St Giles FieldThe famous scene of the meeting of the Lollards at St Giles Fields was later memorialised by Alfred, Lord Tennyson, Lord Tennyson in his poem ''Sir John Oldcastle, Lord Cobham'':

Dissolution of the Hospital of St Giles

The hospital was dissolved in 1539 in the reign ofHenry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disa ...

, its lands, excluding the chapel, being granted to John Dudley, Lord Lisle in 1548. The chapel survived as the local parish church, the first Rector of St Giles being appointed in 1547 when the phrase "in the fields" was first added to the name.

At the time of the dissolution the hospital chapel and the parish church of St. Giles would likely have consisted of two distinct structures under a single roof, much like the arrangement still to be seen in St. Helen's Church, Bishopsgate.

The Vestry minutes of 21 April 1617, record the erection of a steeple

In architecture, a steeple is a tall tower on a building, topped by a spire and often incorporating a belfry and other components. Steeples are very common on Christian churches and cathedrals and the use of the term generally connotes a religi ...

with a peal of bells, but from the fact that "casting the bells" is mentioned as well as the buying of new bells, and from the reference to it in the following year (9 September 1618) as "the new steeple," it seems probable that something of the kind had existed beforAccording to an order of the

Vestry

A vestry was a committee for the local secular and ecclesiastical government for a parish in England, Wales and some English colonies which originally met in the vestry or sacristy of the parish church, and consequently became known colloquiall ...

at the time of the demolition of the Medieval church in 1623, the church consisted of a nave

The nave () is the central part of a church, stretching from the (normally western) main entrance or rear wall, to the transepts, or in a church without transepts, to the chancel. When a church contains side aisles, as in a basilica-type ...

and a chancel

In church architecture, the chancel is the space around the altar, including the choir and the sanctuary (sometimes called the presbytery), at the liturgical east end of a traditional Christian church building. It may terminate in an apse.

Ove ...

, both with pillars, clerestory

In architecture, a clerestory ( ; , also clearstory, clearstorey, or overstorey) is a high section of wall that contains windows above eye level. Its purpose is to admit light, fresh air, or both.

Historically, ''clerestory'' denoted an upper l ...

walls over, and aisle

An aisle is, in general, a space for walking with rows of non-walking spaces on both sides. Aisles with seating on both sides can be seen in airplanes, certain types of buildings, such as churches, cathedrals, synagogues, meeting halls, parl ...

s on either side and stood 153 feet by 65 feet

17th-century, Duchess Dudley's Church

By the second decade of the 17th century the Medieval church had suffered a series of collapses and the parishioners decided to erect a new church which was begun 1623 and completed in 1630. It was consecrated on 26 January 1630. mostly paid for by the Duchess of Dudley, wife of Sir Robert Dudley. The 'poor players of

By the second decade of the 17th century the Medieval church had suffered a series of collapses and the parishioners decided to erect a new church which was begun 1623 and completed in 1630. It was consecrated on 26 January 1630. mostly paid for by the Duchess of Dudley, wife of Sir Robert Dudley. The 'poor players of The Cockpit The Cockpit can refer to:

* Cockpit Theatre, a 17th-century theatre in London (also known as the Phoenix) that opened in 1616

* The Cockpit Theatre (Marylebone), Cockpit, a theatre in London, England that opened in 1970

* The Cockpit (OVA), ''The C ...

theatre' were also said to have contributed a sum of £20 towards the new church building. The new church was handsomely appointed and sumptuously furnished. 123 feet long and the breadth 57 wide with a steeple in rubbed brick, galleries adorning the north and south aisles with a great east window of coloured and painted glass.

The new building was consecrated by William Laud

William Laud (; 7 October 1573 – 10 January 1645) was a bishop in the Church of England. Appointed Archbishop of Canterbury by Charles I in 1633, Laud was a key advocate of Charles I's religious reforms, he was arrested by Parliament in 1640 ...

, Bishop of London

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ca ...

. An illuminated list of subscribers to the rebuilding is still kept in the church.

Civil War

The ruptures in church and state which would eventually lead to theCivil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

were felt early in St Giles Parish. In 1628 the first Rector of the newly consecrated church, Roger Maynwaring

Roger Maynwaring, variously spelt Mainwaring or Manwaring, (29 June 1653) was a bishop in the Church of England, censured by Parliament in 1628 for sermons seen as undermining the law and constitution.

His precise motives for doing so remain unc ...

was fined and deprived of his clerical functions by order of Parliament after two sermons

A sermon is a religious discourse or oration by a preacher, usually a member of clergy. Sermons address a scriptural, theological, or moral topic, usually expounding on a type of belief, law, or behavior within both past and present contexts. E ...

, given on the 4th of May, which were considered to have impugned the rights of Parliament and advocated for the Divine Right of the Stuart Kings.

The controversy would be continued into the 1630s when Archbishop Laud's former chaplain, William Heywood, was installed as Rector. It was Heywood, under Laud's patronage, who began to ornament and decorate St Giles in the High Church

The term ''high church'' refers to beliefs and practices of Christian ecclesiology, liturgy, and theology that emphasize formality and resistance to modernisation. Although used in connection with various Christian traditions, the term originate ...

, Laudian

Laudianism was an early seventeenth-century reform movement within the Church of England, promulgated by Archbishop William Laud and his supporters. It rejected the predestination upheld by the previously dominant Calvinism in favour of free will, ...

fashion and to alter the ceremonial of the sacraments. This provoked the protestant parishioners of St Giles to present Parliament with a petition listing and enumerating the 'popish reliques' with which Heywood had set up 'at needless expense to the parish' as well as the 'Superstitious and Idolatrous manner of administration of the Sacrament of the Lords Supper'. The offending ceremonial was closely described by the parishioners in their complaint to parliament:"They he Clergyenter into the Sanctum Sanctorum in which place they reade their second Service, and it is divided into three parts, which is acted by them all three, with change of place, and many duckings before the Altar, with divers Tones in their Voyces, high and low, with many strange actions by their hands, now up then downe, This being ended, the Doctor takes the Cups from the Altar and delivers them to one of the Subdeacons who placeth' them upon a side Table, Then the Doctor kneeleth to the Altar, but what he doth we know not, nor what hee meaneth by it. . ."Indeed, at this time the interior was heavily furnished by Heywood and provided with numerous

ornaments

An ornament is something used for decoration.

Ornament may also refer to:

Decoration

*Ornament (art), any purely decorative element in architecture and the decorative arts

*Biological ornament, a characteristic of animals that appear to serve on ...

, many of which were the gift of Alice Dudley, Duchess of Dudley. Chief among them was an elaborate screen of carved oak placed where one had formerly stood in the Medieval church. This, as described in the petition to Parliament in 1640, was "in the figure of a beautifull gate, in which is carved two large pillars, and three large statues: on the one side is Paul

Paul may refer to:

*Paul (given name), a given name (includes a list of people with that name)

* Paul (surname), a list of people

People

Christianity

*Paul the Apostle (AD c.5–c.64/65), also known as Saul of Tarsus or Saint Paul, early Chri ...

, with his sword; on the other Barnabas

Barnabas (; arc, ܒܪܢܒܐ; grc, Βαρνάβας), born Joseph () or Joses (), was according to tradition an early Christian, one of the prominent Christian disciples in Jerusalem. According to Acts 4:36, Barnabas was a Cypriot Jew. Name ...

, with his book; and over them Peter

Peter may refer to:

People

* List of people named Peter, a list of people and fictional characters with the given name

* Peter (given name)

** Saint Peter (died 60s), apostle of Jesus, leader of the early Christian Church

* Peter (surname), a sur ...

with his keyes. They are all set above with winged cherub

A cherub (; plural cherubim; he, כְּרוּב ''kərūḇ'', pl. ''kərūḇīm'', likely borrowed from a derived form of akk, 𒅗𒊏𒁍 ''karabu'' "to bless" such as ''karibu'', "one who blesses", a name for the lamassu) is one of the u ...

ims, and beneath supported by lions."Elaborate and expensive altar rails would have separated the altar

An altar is a table or platform for the presentation of religious offerings, for sacrifices, or for other ritualistic purposes. Altars are found at shrines, temples, churches, and other places of worship. They are used particularly in paga ...

from congregation. This ornamental balustrade extended the full width of the chancel

In church architecture, the chancel is the space around the altar, including the choir and the sanctuary (sometimes called the presbytery), at the liturgical east end of a traditional Christian church building. It may terminate in an apse.

Ove ...

and stood 7 or 8 feet east of the screen at the top of three steps while the altar stood close up to the east wall paved with marble.

The result of the parishioners petition to Parliament was that most of the ornaments were stripped and sold in 1643, while Lady Dudley was still alive.

Dr Heywood was still the incumbent at the time of the outbreak of the Great Rebellion in 1642. As well as Rector of St Giles he had, of course, been a domestic chaplain to Archbishop Laud

William Laud (; 7 October 1573 – 10 January 1645) was a bishop in the Church of England. Appointed Archbishop of Canterbury by Charles I in 1633, Laud was a key advocate of Charles I's religious reforms, he was arrested by Parliament in 16 ...

, chaplain in ordinary to King Charles I and prebendary

A prebendary is a member of the Roman Catholic or Anglican clergy, a form of canon with a role in the administration of a cathedral or collegiate church. When attending services, prebendaries sit in particular seats, usually at the back of the ...

at St Paul's cathedral. All this marked him out for special attention after the execution of the King and during the Commonwealth period he was imprisoned and suffered many hardships. Heywood was forced to flee London, residing in Wiltshire

Wiltshire (; abbreviated Wilts) is a historic and ceremonial county in South West England with an area of . It is landlocked and borders the counties of Dorset to the southwest, Somerset to the west, Hampshire to the southeast, Gloucestershire ...

until the Restoration

Restoration is the act of restoring something to its original state and may refer to:

* Conservation and restoration of cultural heritage

** Audio restoration

** Film restoration

** Image restoration

** Textile restoration

* Restoration ecology

...

of the monarchy in 1660 when he was re-instated to the living of St Giles at Westminster.

In 1650, with the fall of the crown seemingly confirmed, at last an order was given for the 'taking down of the Kings Arms' in the church and the clear-glazing of the windows in the nave.

Revd. John Sharp and the Glorious Revolution

In 1660 Charles II was rapturously received back into London and the bells of St Giles were pealed for three days.Royalism

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of govern ...

was at its highest pitch. William Heywood was reinstated to his living for a short period before being succeeded by the Dr Robert Boreman, Clerk of the Green Cloth

The Clerk of the Green Cloth was a position in the British Royal Household. The clerk acted as secretary of the Board of Green Cloth, and was therefore responsible for organising royal journeys and assisting in the administration of the Royal ...

to Charles I Charles I may refer to:

Kings and emperors

* Charlemagne (742–814), numbered Charles I in the lists of Holy Roman Emperors and French kings

* Charles I of Anjou (1226–1285), also king of Albania, Jerusalem, Naples and Sicily

* Charles I of ...

and fellow deprived Royalist. He would be incidentally notorious for his bitter exchange with Richard Baxter

Richard Baxter (12 November 1615 – 8 December 1691) was an English Puritan church leader, poet, hymnodist, theologian, and controversialist. Dean Stanley called him "the chief of English Protestant Schoolmen". After some false starts, he ...

the Nonconformist

Nonconformity or nonconformism may refer to:

Culture and society

* Insubordination, the act of willfully disobeying an order of one's superior

*Dissent, a sentiment or philosophy of non-agreement or opposition to a prevailing idea or entity

** ...

leader and occasional parishioner of St Giles.

In 1675 Dr. John Sharp was appointed to the position of Rector by the influence and patronage of Heneage Finch, 1st Earl of Nottingham

Heneage Finch, 1st Earl of Nottingham, PC (23 December 162018 December 1682), Lord Chancellor of England, was descended from the old family of Finch, many of whose members had attained high legal eminence, and was the eldest son of Sir Heneage ...

and Lord Keeper of the Great Seal

The Lord Keeper of the Great Seal of England, and later of Great Britain, was formerly an officer of the English Crown charged with physical custody of the Great Seal of England. This position evolved into that of one of the Great Officers of S ...

. Sharp's father had been a prominent Bradfordian puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Catholic Church, Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become m ...

who enjoyed the favour of Thomas Fairfax

Thomas Fairfax, 3rd Lord Fairfax of Cameron (17 January 161212 November 1671), also known as Sir Thomas Fairfax, was an English politician, general and Parliamentary commander-in-chief during the English Civil War. An adept and talented command ...

and inculcated him in Calvinist

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John Ca ...

, Low Church, doctrines, while his mother, being strong Royalist

A royalist supports a particular monarch as head of state for a particular kingdom, or of a particular dynastic claim. In the abstract, this position is royalism. It is distinct from monarchism, which advocates a monarchical system of governme ...

, instructed him in the liturgy of the Book of Common Prayer

The ''Book of Common Prayer'' (BCP) is the name given to a number of related prayer books used in the Anglican Communion and by other Christian churches historically related to Anglicanism. The original book, published in 1549 in the reign ...

. Thus he could be seen as bridging the divide within the reformed religion in England. Sharp became deeply committed to his ministry at St Giles and indeed later declined the more profitable benefice of St Martin in the Fields so as to continue ministering to the poor and turbulent parish of St Giles.  The Rector would spend the next sixteen years reforming and reconstituting the parish from the disorder of the post civil war period. He preached regularly (at least twice every Sunday at St Giles as well as weekly in other city churches) and with 'much fluency, piety ndgravity', becoming, according to

The Rector would spend the next sixteen years reforming and reconstituting the parish from the disorder of the post civil war period. He preached regularly (at least twice every Sunday at St Giles as well as weekly in other city churches) and with 'much fluency, piety ndgravity', becoming, according to Bishop Burnet

Gilbert Burnet (18 September 1643 – 17 March 1715) was a Scottish philosopher and historian, and Bishop of Salisbury. He was fluent in Dutch, French, Latin, Greek, and Hebrew. Burnet was highly respected as a cleric, a preacher, an academic, ...

'one of the most popular preachers of the age'. Sharp completely re-ordered the system of worship at St Giles around the Established Liturgy of the Book Of Common Prayer

The ''Book of Common Prayer'' (BCP) is the name given to a number of related prayer books used in the Anglican Communion and by other Christian churches historically related to Anglicanism. The original book, published in 1549 in the reign ...

, a liturgy he considered 'almost perfectly designed'. He instituted, perhaps for the first time, a weekly Holy Communion

The Eucharist (; from Greek , , ), also known as Holy Communion and the Lord's Supper, is a Christian rite that is considered a sacrament in most churches, and as an ordinance in others. According to the New Testament, the rite was instituted ...

and restored the Daily Offices in the church. Sharp also insisted upon communicants kneeling to receive communion. In the wider parish he was constant in his catechising of young people and in performing visitations of the sick, often at the hazard of his own life. Somehow he avoided serious illness despite 'bear nghis share of duty among the cellars and the garrets' of a district already synonymous with plague and sickness. Indeed his solicitude for his parishioners left him at risk in many ways. He once survived an attempted assassination by Jacobite agents constructed around the pretense of luring him to visit a dying parishioner. He attended with an armed servant and the 'parishioner' staged an 'instant recovery'.

In 1685 Sharp was tasked by the Lord Mayor with drawing up for the Grand Jury of London their address of congratulations on the accession of James II and on 20 April 1686 he became chaplain in ordinary to the King. However, provoked by the subversion of his parishioners faith by Jesuit priests and Jacobite agents, Sharp preached two sermons at St. Giles on 2 and 9 May, which were held to reflect adversely on the King's religious policy. As a result Henry Compton, bishop of London

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ca ...

, was ordered by the Lord President of the Council, to summarily suspend Sharp from his position at St Giles. Compton refused, but in an interview at Doctors' Commons

Doctors' Commons, also called the College of Civilians, was a society of lawyers practising civil (as opposed to common) law in London, namely ecclesiastical and admiralty law. Like the Inns of Court of the common lawyers, the society had buildi ...

on the 18th instant privately advised Sharp to ‘forbear the pulpit’ for the present. On 1 July, by the advice of Judge Jeffreys

George Jeffreys, 1st Baron Jeffreys, PC (15 May 1645 – 18 April 1689), also known as "the Hanging Judge", was a Welsh judge. He became notable during the reign of King James II, rising to the position of Lord Chancellor (and serving as ...

, he left London for Norwich

Norwich () is a cathedral city and district of Norfolk, England, of which it is the county town. Norwich is by the River Wensum, about north-east of London, north of Ipswich and east of Peterborough. As the seat of the See of Norwich, with ...

; but when he returned to London in December his petition, revised by Jeffreys, was received, and in January 1687 he was reinstated.

In August 1688 Sharp was again in trouble. After refusing to read the declaration of indulgence

The Declaration of Indulgence, also called Declaration for Liberty of Conscience, was a pair of proclamations made by James II of England and Ireland and VII of Scotland in 1687. The Indulgence was first issued for Scotland on 12 February and t ...

he summoned before the ecclesiastical commission of James II. He argued that though obedience was due to the king in preference to the archbishop, yet that obedience went no further than what was legal and honest. After the Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution; gd, Rèabhlaid Ghlòrmhor; cy, Chwyldro Gogoneddus , also known as the ''Glorieuze Overtocht'' or ''Glorious Crossing'' in the Netherlands, is the sequence of events leading to the deposition of King James II and ...

he visited the imprisoned 'Bloody' Jeffreys in the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is separa ...

and attempted to bring him to penitence and consolation for his crimes.

Soon after the Revolution

In political science, a revolution (Latin: ''revolutio'', "a turn around") is a fundamental and relatively sudden change in political power and political organization which occurs when the population revolts against the government, typically due ...

Sharp preached before the Prince of Orange

Prince of Orange (or Princess of Orange if the holder is female) is a title originally associated with the sovereign Principality of Orange, in what is now southern France and subsequently held by sovereigns in the Netherlands.

The title ...

(soon to be King William III

William III (William Henry; ; 4 November 16508 March 1702), also widely known as William of Orange, was the sovereign Prince of Orange from birth, Stadtholder of Holland, Zeeland, Utrecht, Guelders, and Overijssel in the Dutch Republic from the ...

) and three days later before the Convention Parliament. On each occasion he included prayers for King James I

James VI and I (James Charles Stuart; 19 June 1566 – 27 March 1625) was King of Scotland as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the Scottish and English crowns on 24 March 1603 until hi ...

I on the ground that the lords had not yet concurred in the abdication

Abdication is the act of formally relinquishing monarchical authority. Abdications have played various roles in the succession procedures of monarchies. While some cultures have viewed abdication as an extreme abandonment of duty, in other societ ...

. On 7 Sept. 1689 he was named dean of Canterbury

The Dean of Canterbury is the head of the Chapter of the Cathedral of Christ Church, Canterbury, England. The current office of Dean originated after the English Reformation, although Deans had also existed before this time; its immediate precur ...

succeeding John Tillotson

John Tillotson (October 1630 – 22 November 1694) was the Anglican Archbishop of Canterbury from 1691 to 1694.

Curate and rector

Tillotson was the son of a Puritan clothier at Haughend, Sowerby, Yorkshire. Little is known of his early youth ...

.

The Henry Flitcroft church

St.Giles's Parish enjoys the unfortunate distinction of having originated the Great Plague of 1665. It is on record that the first persons seized were members of a family living near the top ofDrury Lane

Drury Lane is a street on the eastern boundary of the Covent Garden area of London, running between Aldwych and High Holborn. The northern part is in the borough of Camden and the southern part in the City of Westminster.

Notable landmarks ...

, where two men, said to have been Frenchmen, were attacked by it, and speedily carried off.

The high number of plague victims buried in and around the church were the probable cause of a damp problem evident by 1711. The excessive number of burials in the parish had led to the churchyard rising as much as eight feet above the nave floor. The parishioners petitioned the Commission for Building Fifty New Churches for a grant to rebuild. Initially refused as it was not a new foundation and the Act was intended for new parishes in under-churched areas, the parish was eventually allocated £8,000 and a new church was built in 1730–1734, designed by architect Henry Flitcroft

Henry Flitcroft (30 August 1697 – 25 February 1769) was a major English architect in the second generation of Palladianism. He came from a simple background: his father was a labourer in the gardens at Hampton Court and he began as a joiner by t ...

in the Palladian

Palladian architecture is a European architectural style derived from the work of the Venetian architect Andrea Palladio (1508–1580). What is today recognised as Palladian architecture evolved from his concepts of symmetry, perspective and ...

style. The first stone was laid by the Bishop of Norwich

The Bishop of Norwich is the ordinary of the Church of England Diocese of Norwich in the Province of Canterbury. The diocese covers most of the county of Norfolk and part of Suffolk. The bishop of Norwich is Graham Usher.

The see is in t ...

on Michaelmas

Michaelmas ( ; also known as the Feast of Saints Michael, Gabriel, and Raphael, the Feast of the Archangels, or the Feast of Saint Michael and All Angels) is a Christian festival observed in some Western liturgical calendars on 29 September, a ...

, 29 September 1731.

The Flitcroft rebuilding represents a shift from the Baroque

The Baroque (, ; ) is a style of architecture, music, dance, painting, sculpture, poetry, and other arts that flourished in Europe from the early 17th century until the 1750s. In the territories of the Spanish and Portuguese empires including t ...

to the Palladian

Palladian architecture is a European architectural style derived from the work of the Venetian architect Andrea Palladio (1508–1580). What is today recognised as Palladian architecture evolved from his concepts of symmetry, perspective and ...

form of church building in England and has been described as 'one of the least known but most significant episodes in Georgian

Georgian may refer to:

Common meanings

* Anything related to, or originating from Georgia (country)

** Georgians, an indigenous Caucasian ethnic group

** Georgian language, a Kartvelian language spoken by Georgians

**Georgian scripts, three scrip ...

church design, standing at a crucial crossroads of radical architectural change and representing nothing less than the first Palladian-Revival church to be erected in London...". Nicholas Hawksmoor

Nicholas Hawksmoor (probably 1661 – 25 March 1736) was an English architect. He was a leading figure of the English Baroque style of architecture in the late-seventeenth and early-eighteenth centuries. Hawksmoor worked alongside the principa ...

had been an early choice to design the new church building at St Giles but tastes had begun to turn against his freewheeling mannerist

Mannerism, which may also be known as Late Renaissance, is a style in European art that emerged in the later years of the Italian High Renaissance around 1520, spreading by about 1530 and lasting until about the end of the 16th century in Italy, ...

style (his recent work on the nearby St George's Bloomsbury was strongly criticised). Instead the young and inexperienced Henry Flitcroft

Henry Flitcroft (30 August 1697 – 25 February 1769) was a major English architect in the second generation of Palladianism. He came from a simple background: his father was a labourer in the gardens at Hampton Court and he began as a joiner by t ...

was chosen and he would take as his inspiration and guide the Caroline buildings of Inigo Jones

Inigo Jones (; 15 July 1573 – 21 June 1652) was the first significant architect in England and Wales in the early modern period, and the first to employ Vitruvian rules of proportion and symmetry in his buildings.

As the most notable archit ...

rather than the work of Wren, Hawksmoor

Nicholas Hawksmoor (probably 1661 – 25 March 1736) was an English architect. He was a leading figure of the English Baroque style of architecture in the late-seventeenth and early-eighteenth centuries. Hawksmoor worked alongside the principa ...

or Gibbs. Only in the matter of the spire

A spire is a tall, slender, pointed structure on top of a roof of a building or tower, especially at the summit of church steeples. A spire may have a square, circular, or polygonal plan, with a roughly conical or pyramidal shape. Spires are ...

of the church, for which Palladio had no model, did Flitcroft borrow as his model the steeple of James Gibbs's St Martin's in the Fields but even then, in altering the Order and preferring a solid, belted summit, he made it all his own. The wooden model he made so that parishioners could see what they were commissioning, can still be seen in the church's north transept

A transept (with two semitransepts) is a transverse part of any building, which lies across the main body of the building. In cruciform churches, a transept is an area set crosswise to the nave in a cruciform ("cross-shaped") building withi ...

. The Vestry

A vestry was a committee for the local secular and ecclesiastical government for a parish in England, Wales and some English colonies which originally met in the vestry or sacristy of the parish church, and consequently became known colloquiall ...

House was built at the same time.

As London grew in the 18th and 19th centuries, so did the parish's population, eventually reaching 30,000 by 1831 which suggests a high density. It included two neighbourhoods noted for poverty and squalor: the Rookery

A rookery is a colony of breeding animals, generally gregarious birds.

Coming from the nesting habits of rooks, the term is used for corvids and the breeding grounds of colony-forming seabirds, marine mammals ( true seals and sea lions), and ...

between the church and Great Russell Street

Great Russell Street is a street in Bloomsbury, London, best known for being the location of the British Museum. It runs between Tottenham Court Road (part of the A400 route) in the west, and Southampton Row (part of the A4200 route) in the east ...

, and Seven Dials. These became a centre for prostitution and crime and the name St Giles became associated with the underworld, gambling houses and the consumption of gin. St Giles's Roundhouse was a gaol and St Giles' Greek a thieves' cant

Thieves' cant (also known as thieves' argot, rogues' cant, or peddler's French) is a cant, cryptolect, or argot which was formerly used by thieves, beggars, and hustlers of various kinds in Great Britain and to a lesser extent in other English- ...

. As the population grew, so did their dead, and eventually there was no room in the graveyard: many burials of parishioners (including the architect Sir John Soane

Sir John Soane (; né Soan; 10 September 1753 – 20 January 1837) was an English architect who specialised in the Neoclassical architecture, Neo-Classical style. The son of a bricklayer, he rose to the top of his profession, becoming professo ...

) in the 18th and 19th centuries took place outside the parish in the churchyard of St Pancras old church

St Pancras Old Church is a Church of England parish church in Somers Town, Central London. It is dedicated to the Roman martyr Saint Pancras, and is believed by many to be one of the oldest sites of Christian worship in England. The church i ...

John Wesley

John Wesley (; 2 March 1791) was an English people, English cleric, Christian theology, theologian, and Evangelism, evangelist who was a leader of a Christian revival, revival movement within the Church of England known as Methodism. The soci ...

, the English cleric, theologian, and evangelist and leader of a revival movement within the Church of England known as Methodism

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a group of historically related denominations of Protestant Christianity whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John Wesley. George Whitefield and John's br ...

is believed to have preached occasionally at Evening Prayer at St Giles from the large pulpit dating from 1676 which survived the rebuild and, indeed, is still in use today. Also retained in the church is a smaller whitewashed box-pulpit originally belonging to the nearby West Street Chapel used by both John

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Secon ...

and Charles Wesley to preach the Gospel.

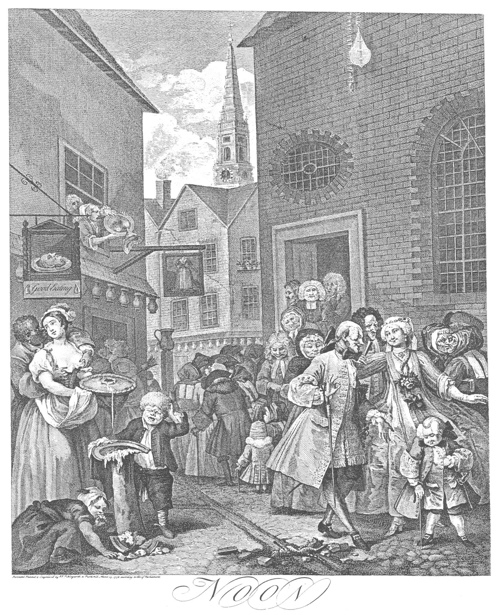

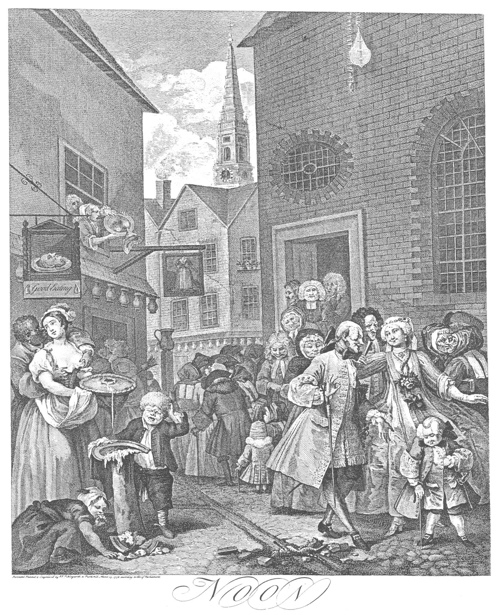

During this time St Giles in the Fields was the last church on the old route between Newgate Prison

Newgate Prison was a prison at the corner of Newgate Street and Old Bailey Street just inside the City of London, England, originally at the site of Newgate, a gate in the Roman London Wall. Built in the 12th century and demolished in 1904, t ...

and the gallows at Tyburn

Tyburn was a manor (estate) in the county of Middlesex, one of two which were served by the parish of Marylebone.

The parish, probably therefore also the manor, was bounded by Roman roads to the west (modern Edgware Road) and south (modern Ox ...

. The churchwarden

A churchwarden is a lay official in a parish or congregation of the Anglican Communion or Catholic Church, usually working as a part-time volunteer. In the Anglican tradition, holders of these positions are ''ex officio'' members of the parish b ...

s of the time paid for the condemned to have a drink (popularly named St Giles' Bowl) at the inn

Inns are generally establishments or buildings where travelers can seek lodging, and usually, food and drink. Inns are typically located in the country or along a highway; before the advent of motorized transportation they also provided accommo ...

next door to the church, ''The Angel'', before they were hanged in a custom dating back to the early 15th century. The dissolute nature of the area is described in Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English writer and social critic. He created some of the world's best-known fictional characters and is regarded by many as the greatest novelist of the Victorian e ...

' ''Sketches by Boz

''Sketches by "Boz," Illustrative of Every-day Life and Every-day People'' (commonly known as ''Sketches by Boz'') is a collection of short pieces Charles Dickens originally published in various newspapers and other periodicals between 1833 and ...

''.

Architects Sir Arthur Blomfield

Sir Arthur William Blomfield (6 March 182930 October 1899) was an English architect. He became president of the Architectural Association in 1861; a Fellow of the Royal Institute of British Architects in 1867 and vice-president of the RIBA in ...

and William Butterfield

William Butterfield (7 September 1814 – 23 February 1900) was a Gothic Revival architect and associated with the Oxford Movement (or Tractarian Movement). He is noted for his use of polychromy.

Biography

William Butterfield was born in Lon ...

made minor alterations in 1875 and 1896.

World War Two and restoration.

Although St Giles escaped direct bombing hits in theSecond World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, high explosives still destroyed most of its Victorian stained glass and the roof of the nave was severely damaged. The Vestry house was filled with rubble and the churchyard was fenced with chicken wire, while the Rectory on Great Russell Street had been entirely destroyed. The Parish itself was in as parlous a state with the theft of the PCC funds and the surrounding area ruined and parishioners dispersed by war. Into this position the Revd Gordon Taylor was appointed Rector and set about energetically rebuilding the church and parish.

The church was designated a Grade I listed building

In the United Kingdom, a listed building or listed structure is one that has been placed on one of the four statutory lists maintained by Historic England in England, Historic Environment Scotland in Scotland, in Wales, and the Northern Irel ...

on 24 October 1951 and Revd. Gordon Taylor raised funds for a major restoration of the church undertaken between 1952 and 1953. It adhering to Flitcroft's original intentions, on which the Georgian Group

The Georgian Group is a British charity, and the national authority on Georgian architecture built between 1700 and 1837 in England and Wales. As one of the National Amenity Societies, The Georgian Group is a statutory consultee on alterat ...

and Royal Fine Art Commission

The Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment (CABE) was an executive non-departmental public body of the UK government, established in 1999. It was funded by both the Department for Culture, Media and Sport and the Department for ...

were consulted and was described by the journalist and poet John Betjeman

Sir John Betjeman (; 28 August 190619 May 1984) was an English poet, writer, and broadcaster. He was Poet Laureate from 1972 until his death. He was a founding member of The Victorian Society and a passionate defender of Victorian architecture, ...

as "one of the most successful post-war church restorations" (''Spectator'' 9 March 1956). Revd. Gordon Taylor slowly rebuilt the congregation, refurbished the St Giles's Almshouses and reinvigorated the ancient parochial charities. He also worked successfully with Austen Williams of St Martin-in-the-Fields

St Martin-in-the-Fields is a Church of England parish church at the north-east corner of Trafalgar Square in the City of Westminster, London. It is dedicated to Saint Martin of Tours. There has been a church on the site since at least the mediev ...

to defeat the comprehensive redevelopment of Covent Garden

Covent Garden is a district in London, on the eastern fringes of the West End, between St Martin's Lane and Drury Lane. It is associated with the former fruit-and-vegetable market in the central square, now a popular shopping and tourist si ...

, stopping the construction of a major road planned to run through the parish, which would have involved the demolition of the Almshouses, giving evidence himself before the public inquiry.

Rev. Taylor eventually came to see himself as a defender and custodian of what he saw as the traditional Church of England, the Established Liturgy and the use of the Book of Common Prayer

The ''Book of Common Prayer'' (BCP) is the name given to a number of related prayer books used in the Anglican Communion and by other Christian churches historically related to Anglicanism. The original book, published in 1549 in the reign ...

.

St Giles Churchyard

The churchyard and burying place lies to the south of the church building on the site of the original burial yard of the Leper Hospital. The churchyard, which holds many centuries of dead, buried on top of each other, was frequently enlarged with overcrowding a perennial problem. A 19th Century historian of London's burial grounds described conditions at the beginning of that century thus "it could not have been a pleasant churchyard to look at. It was always damp, and vast numbers of the poor Irish were buried in it (the ground having been originally consecrated by a Roman Catholic)...it is hardly to be wondered at that the parish of St. Giles’ enjoys the honour of having started the plague of 1665. The practices carried on there at the beginning of this century were equal to the worst anywhere revolting ill-treatment of the dead was the daily custom." The first victims of the 1665 Great Plague of London, Great Plague were buried in St Giles's Churchyard. By the end of the plague year there were 3,216 listed deaths in a church parish with fewer than 2,000 households. A plot of land named Brown's Gardens was added to the churchyard in 1628 and in 1803 an additional burial-ground, adjoining that of St. Pancras was purchased, where the St Giles parishionerSir John Soane

Sir John Soane (; né Soan; 10 September 1753 – 20 January 1837) was an English architect who specialised in the Neoclassical architecture, Neo-Classical style. The son of a bricklayer, he rose to the top of his profession, becoming professo ...

is buried.

Roman Catholic Burials

The Churchyard of St Giles may be said to enjoy a particular significance and reverence in the hearts and minds of Catholic Church, Roman Catholics. One has gone as far as to describe it as 'London's most Hallowed Space'. As the ground was originally consecrated by a Roman Catholic and, indeed, later placed under the special protection ofPope Alexander IV

Pope Alexander IV (1199 or 1185 – 25 May 1261) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 12 December 1254 to his death in 1261.

Early career

He was born as Rinaldo di Jenne in Jenne (now in the Province of Rome), he ...

it is still considered 'hallowed ground' and was thus considered an acceptable place of burial for and by Roman Catholics during the time of the Penal law (British), penal laws in England. It has therefore been the burial place of a number of distinguished Roman Catholics since the Reformation as well as many thousands of poor and nameless Irish Catholic immigrants to London.

During the religious conflicts of the 17th Century a number of notable Roman Catholic figures were interred there including John Belasyse, 1st Baron Belasyse, Richard Penderel and James Radclyffe, 3rd Earl of Derwentwater, James Radcliffe, 3rd Earl of Derwentwater (executed at Tower Hill after the failure of the Jacobite rising of 1715, Jacobite Rebellion of 1715)

A number of Roman Catholic priests and laymen, executed for Treason, High Treason on the false testimony of Titus Oates during the fictitious conspiracy and panic known as the Popish Plot, were buried near the church's north wall following their executions:

These included

*Oliver Plunkett, Archbishop of Armagh (Roman Catholic), Archbishop of Armagh, buried (according to the parish register) on 1 July 1681, but exhumed in 1683 and taken to Lamspringe Abbey in Germany. Later it was moved again. His head went to Rome, was then given to the Archbishop of Armagh, and is now at Drogheda. His body rests at Downside Abbey, Somerset.

*The five Society of Jesus, Jesuit fathers with whom Plunkett asked to be buried:

**Thomas Whitbread, William Harcourt (martyr), William Harcourt, John Fenwick (Jesuit), John Fenwick, John Gavan and Anthony Turner (martyr)

*Edward Coleman (martyr), Edward Coleman (or Edward Colman (martyr), Colman), secretary to the Mary of Modena, Duchess of York

*Richard Langhorne, barrister

*Edward Micó, priest, who died soon after arrest. He was the only one of the twelve martyrs not to be executed at Tyburn.

*William Ireland (Jesuit), William Ireland, kinsman of Richard Penderel.

*John Grove (priest), John Grove, priest

*Blessed Thomas Pickering, Thomas Pickering, lay brother

All 12 were later Beatification, beatified by Pope Pius XI, Pope Pius XI while Oliver Plunkett was canonised by Pope Paul VI in 1975. A memorial for the seven Jesuits and all those buried within the churchyard was unveiled on 20 January 2019.

Fr Lawrence Lew O.P. of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Westminster has described the place thus:

"The churchyard of St Giles may appear to the casual passer-by as a convenient green space to sit down, enjoy a sandwich and catch up with the social media. In actual fact it is one of London's most hallowed spots, with the remains of eleven beatified martyrs hidden beneath the ground, silently witnessing to the faith and awaiting the day of resurrection."

A memorial for the seven Jesuits and all those buried within the churchyard was unveiled on 20 January 2019.

Fr Lawrence Lew O.P. of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Westminster has described the place thus:

"The churchyard of St Giles may appear to the casual passer-by as a convenient green space to sit down, enjoy a sandwich and catch up with the social media. In actual fact it is one of London's most hallowed spots, with the remains of eleven beatified martyrs hidden beneath the ground, silently witnessing to the faith and awaiting the day of resurrection."

Richard Penderel's tomb

Standing among the bushes at the south corner of the east end of the church is the tomb of Richard Penderel, a West Country Yeoman instrumental in the escape of Charles II of England, Charles II after the Battle of Worcester, battle of Worcester in 1651. Richard cut the king's hair, dressed him in country garb and hid the king in the branches of the Royal Oak to escape his pursuers. Upon theRestoration

Restoration is the act of restoring something to its original state and may refer to:

* Conservation and restoration of cultural heritage

** Audio restoration

** Film restoration

** Image restoration

** Textile restoration

* Restoration ecology

...

Richard was rewarded with a pension and visited court once a year, lodging at Great Turnstile off of Lincoln's Inn Fields, Lincolns Inn. Here February 1671–2 he caught the 'St Giles Fever' and was buried beneath a splendid chest tomb. The tomb was ‘repaired and beautified’ by order of George II of Great Britain, George II in 1739 but later fell into decay.

The inscription on the side of the tomb is still faintly visible and reads:

“Here lieth Richard Pendrell, Preserver and Conductor to his sacred Majesty King Charles the Second of Great Britain, after his Escape from Worcester Fight, in the Year 1651, who died Feb. 8, 1671. Hold, Passenger, here's shrouded in this Herse, Unparalell'd Pendrell, thro’ the Universe. Like when the Eastern Star From Heaven gave Light To three lost Kings; so he, in such dark Night, To Britain's Monarch, toss'd by adverse War, On Earth appear'd, a Second Eastern Star, A Pope, a Stern, in her rebellious Main, A Film to her Royal Sovereign. Now to triumph in Heav’n's eternal Sphere, He's hence advanc'd, for his just Steerage here; Whilst Albion's Chronicles, with matchless Fame, Embalm the Story of great Pendrell's Name.”In 1922 the tomb slab, by now deteriorating in its exposed position, was moved inside the church and is now mounted in the west end of the church building alongside the famous Royalist hero of Edgehill, Newbury and Naseby, John Lord Belasyse.

The Resurrection Gate

At the western end of the churchyard facing Flitcroft Street stands the Resurrection Gate, a grand lychgate in the Doric order, Doric order. It formerly stood on the north side of the churchyard, to be gazed upon by the condemned prisoner on his way to execution at Tyburn. The Gate is adorned with a Bas-Relief, bas-relief of the Last Judgment, Day of Judgement. The carving is probably the work of a wood-carver named Mr Love and was commissioned in 1686 when directions were given by the vestry to erect "a substantial gate out of the wall of the churchyard near the round house". Rowland Dobie, in his "History of St. Giles'," states that "the composition is, with various alterations, taken from Michael Angelo's 'Last Judgment' however Mr. J. T. Smith, in his "Book for a Rainy Day," says of the carving that it was "borrowed, not from Michael Angelo, but from the workings of the brain of some ship-carver". The Gate was rebuilt in 1810 to the designs of the architect and churchwarden of St Giles William Leverton and, In 1865, being unsafe, it was taken down and carefully re-erected opposite the west door in anticipation of the re-routing ofCharing Cross Road

Charing Cross Road is a street in central London running immediately north of St Martin-in-the-Fields to St Giles Circus (the intersection with Oxford Street) and then becomes Tottenham Court Road. It leads from the north in the direction of ...

. As it happened Charing Cross road bypassed Flitcroft Street and now the gate faces onto a narrow alleyway.

Features of interest

Organ

The first 17th-century organ was destroyed in the English Civil War. George Dallam built a replacement in 1678, which was rebuilt in 1699 by Christian Smith, a nephew of the great organ builder "Father" Smith. A second rebuilding in the new structure was done in 1734 by Gerard Smith the younger, possibly assisted by Johann Knopple. Much of the pipework from 1678 and 1699 was recycled. A rebuilding, again recycling much of Dallam's original pipework, was done in 1856 by London organ builders Gray & Davison, then at the height of their fame. In 1960 the mechanical key and stop actions were replaced with an electro-pneumatic action. This was removed when the organ was extensively restored in a historically informed manner by William Drake (organ builder), William Drake, completing in 2006. Drake put back tracker action and preserved as much old pipework as possible, with new pipework in a 17th-century style.

Wesley's Pulpit

In the east end of the north aisle there is a small box pulpit from which both John and Charles Wesley, the leaders of the Methodist movement, were known to preach. Now whitewashed with a memorial inscription, it represents only the top part of a 'triple decker' pulpit which Wesley would have used in the nearby West Street Chapel. Wesley had taken on the lease of the building off of a dwindling Huguenots, Huguenot congregation and it remained with the Methodists until his death in 1791. Also known to preach from within this pulpit were George Whitefield, George Whitfield and John William Fletcher. At the beginning of the 19th Century the Chapel was taken on by the Church of England, becoming All Saints West Street, and later closed for worship whereupon the pulpit was removed and preserved at St Giles.

Baptismal Font

Dating from 1810 the white marble Baptismal font, font with Greek Revival architecture, Greek Revival detailing is noted by Nikolaus Pevsner, Pevsner as being attributed to the architect and designerSir John Soane

Sir John Soane (; né Soan; 10 September 1753 – 20 January 1837) was an English architect who specialised in the Neoclassical architecture, Neo-Classical style. The son of a bricklayer, he rose to the top of his profession, becoming professo ...

.

On the 9th March 1818 William and Clara Everina Shelley were baptised in this font in the presence of the novelist Mary Shelley (nee Wollstonecraft) and her husband, the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley. Also baptised that day was Allegra the illegitimate daughter of Mary's step-sister Claire Clairmont and the poet Lord Byron. Part of the group's haste in baptising the children together, along with Percy's debts, ill-health and fears over the custody of his own children, was the desire to take Allegra to her father, Lord Byron, then in Venice.

All three children were to die in childhood in Italy. After the premature death of the toddler Allegra Byron, at the age of 5, a grieving Shelley portrayed the toddler as Count Maddalo's child in his 1819 poem ''Julian and Maddalo, Julian and Maddalo: A Conversation'':A lovelier toy sweet Nature never made; A serious, subtle, wild, yet gentle being; Graceful without design, and unforeseeing; With eyes – O speak not of her eyes! which seem Twin mirrors of Italian heaven, yet gleam With such deep meaning as we never see But in the human countenance.Shelley himself was to drown off the coast of Livorno, Leghorn in 1822.

The 'Poet's Church'

St Giles is sometimes called the "Poets' Church" on account of connections to several poets and dramatists beginning in the 16th Century. An early post-reformation Rector, Nathaniel Baxter was both clergyman and poet. In earlier life he had been tutor to Sir Philip Sidney, and interested in the manner of Sidney's circle in literature and Ramist logic,. He is now remembered for his 1606 poem ''Ourania.'' The poor players of the Cockpit Theatre are said to have contributed £20 to the building of the second church on the site before their suppression by Parliament in 1642. James Shirley and Thomas Nabbes, two noted English playwrights of the 17th Century were buried within the church. Both were writers of city comedies and historical tragedies. Shirley was perhaps the most prolific and highly regarded dramatist of the reign of King Charles I, writing 31 plays, 3 masques, and 3 moral allegories. He is remembered for his comedies of fashionable London life and is perhaps best known for his poem 'Death the Leveller' at the close of his ''Contention of Ajax and Ulysses'' which begins:"The glories of our blood and state Are shadows, not substantial things; There is no armour against fate; Death lays his icy hand on kings: Sceptre and crown Must tumble down, And in the dust be equal made With the poor crooked scythe and spade."Also buried in the churchyard was Michael Mohun, a leading English actor both before and after the 1642–60 closing of the theatres. A memorial in the church commemorates George Chapman (died 1634), intimate friend of Ben Jonson, the translator of Homer and writer of masques, who is buried outside in the churchyard. His memorial was designed by

Inigo Jones