St. Mary's Church, Lübeck on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Lübeck Marienkirche (officially St Marien zu Lübeck) is a medieval

In 1160,

In 1160,

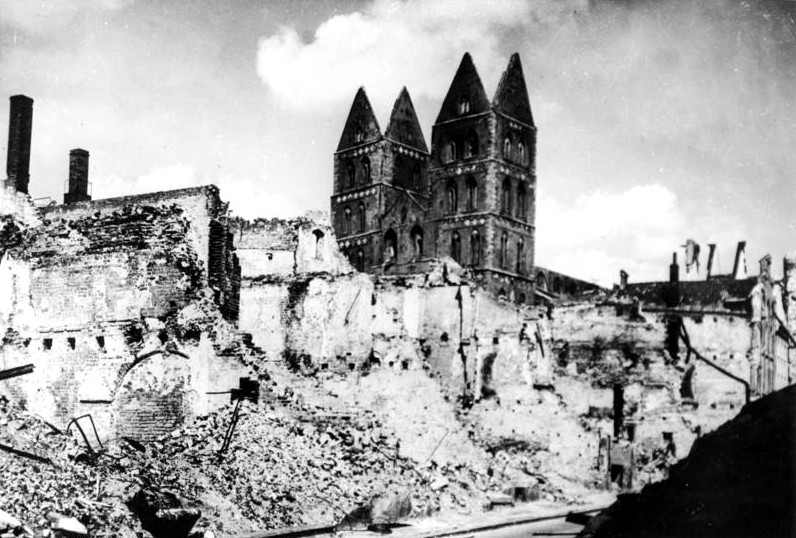

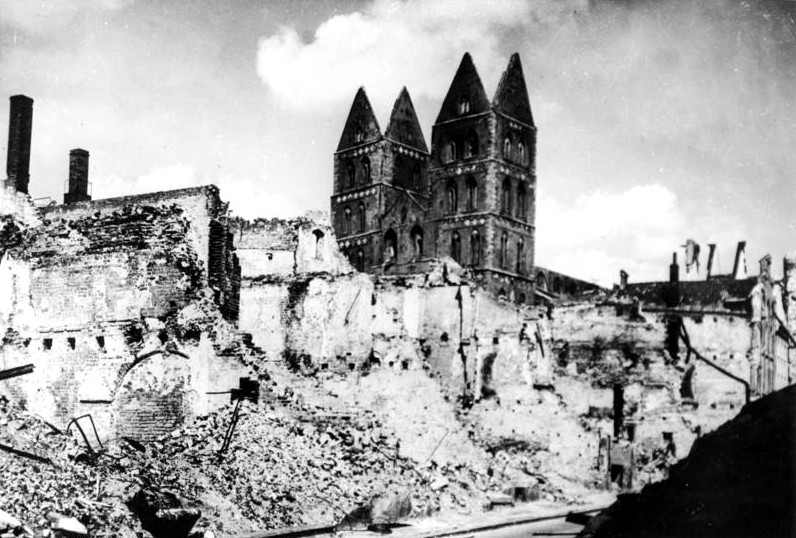

In an air raid by the

In an air raid by the  In 1951, the 700th anniversary of the church was celebrated under the reconstructed roof; for the occasion, Chancellor

In 1951, the 700th anniversary of the church was celebrated under the reconstructed roof; for the occasion, Chancellor

St. Mary's Church was generously endowed with donations from the city council, the guilds, families, and individuals. At the end of the

St. Mary's Church was generously endowed with donations from the city council, the guilds, families, and individuals. At the end of the

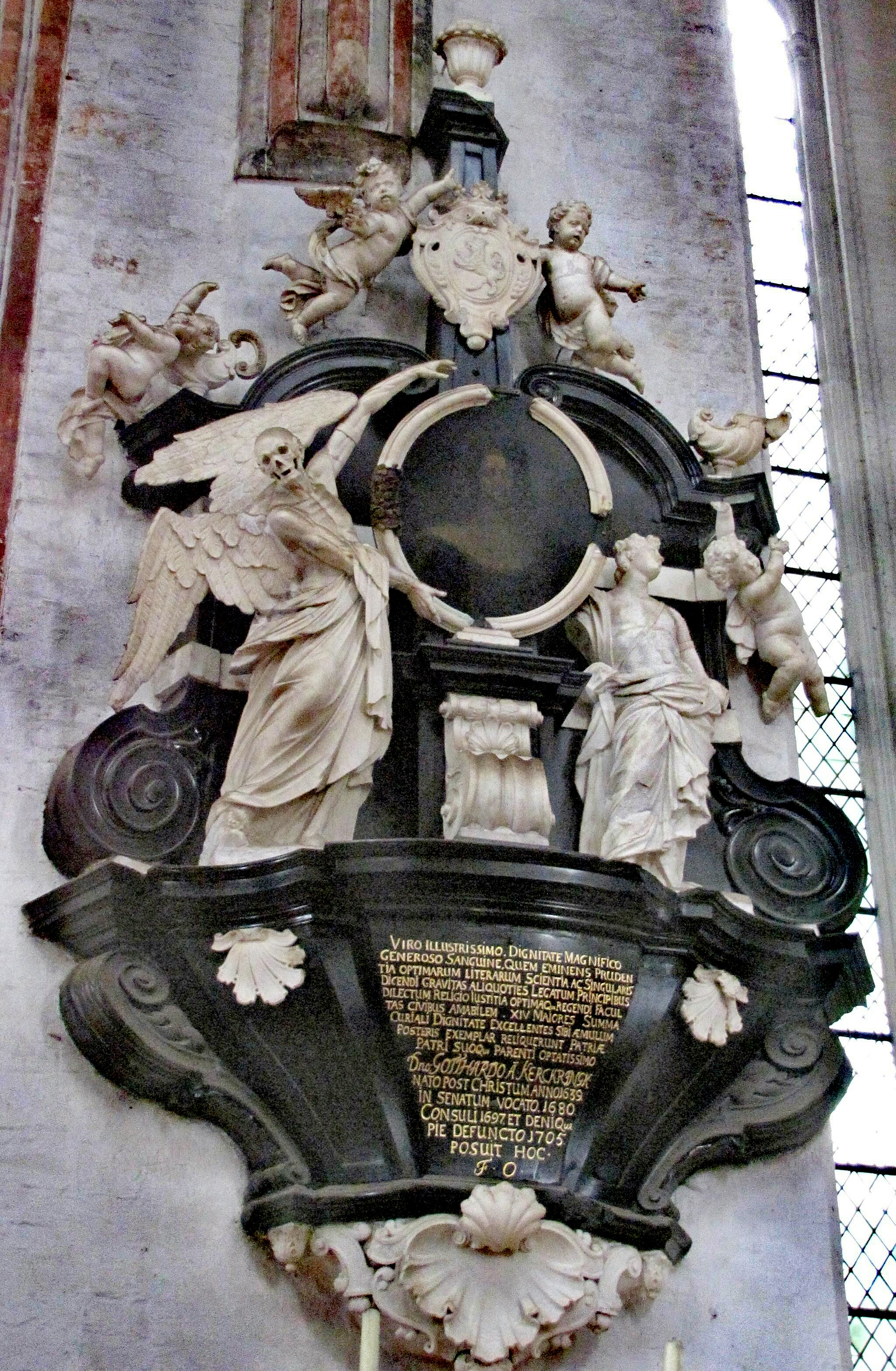

In the renaissance and baroque periods, the church space contained so many memorials that it became like a hall of fame of the Lübeck gentry. Memorials in the main nave, allowed from 1693, had to be made of wood, for structural reasons, but those in the side naves could also be made of marble. Of the 84 memorials that were still extant in the 20th century, almost all of the wooden ones were destroyed by the air raid of 1942, but 17, mostly stone ones on the walls of the side naves survived, some heavily damaged. Since these were mostly baroque works, they were deliberately ignored in the first phase of reconstruction, restoration beginning in 1973. They give an impression of how richly St. Mary's church was once furnished. The oldest is that of , a mayor who died in 1594, a heraldic design with mediaeval echoes. The memorial to , a former councillor and Hanseatic merchant who died in 1637, is a Dutch work of the transitional period between the Renaissance and Baroque times by the sculptor who worked in Amsterdam.

After the phase of exuberant cartilage baroque, the examples of which were all destroyed by fire, Thomas Quellinus introduced a new type of memorial to Lübeck and created memorials in the dramatic style of Flemish High Baroque for

* the councillor , made in 1699;

* the councillor , made in 1706;

* the mayor (who died in 1704) and

* the mayor (1707),

the last one being the only one to remain undamaged.

In the same year, the Lübeck sculptor created the memorial for councillor (who had died in 1705), whose oval portrait is held by a winged figure of death.

A well-preserved example of the memorials of the next generation is the one for , a mayor who died in 1723.

The Sepulchral Chapel of the Tesdorpf family contains a bust by

In the renaissance and baroque periods, the church space contained so many memorials that it became like a hall of fame of the Lübeck gentry. Memorials in the main nave, allowed from 1693, had to be made of wood, for structural reasons, but those in the side naves could also be made of marble. Of the 84 memorials that were still extant in the 20th century, almost all of the wooden ones were destroyed by the air raid of 1942, but 17, mostly stone ones on the walls of the side naves survived, some heavily damaged. Since these were mostly baroque works, they were deliberately ignored in the first phase of reconstruction, restoration beginning in 1973. They give an impression of how richly St. Mary's church was once furnished. The oldest is that of , a mayor who died in 1594, a heraldic design with mediaeval echoes. The memorial to , a former councillor and Hanseatic merchant who died in 1637, is a Dutch work of the transitional period between the Renaissance and Baroque times by the sculptor who worked in Amsterdam.

After the phase of exuberant cartilage baroque, the examples of which were all destroyed by fire, Thomas Quellinus introduced a new type of memorial to Lübeck and created memorials in the dramatic style of Flemish High Baroque for

* the councillor , made in 1699;

* the councillor , made in 1706;

* the mayor (who died in 1704) and

* the mayor (1707),

the last one being the only one to remain undamaged.

In the same year, the Lübeck sculptor created the memorial for councillor (who had died in 1705), whose oval portrait is held by a winged figure of death.

A well-preserved example of the memorials of the next generation is the one for , a mayor who died in 1723.

The Sepulchral Chapel of the Tesdorpf family contains a bust by

The main item from the Baroque period, an altar with an altarpiece high, donated by the merchant and made by the Antwerp sculptor Thomas Quellinus from

The main item from the Baroque period, an altar with an altarpiece high, donated by the merchant and made by the Antwerp sculptor Thomas Quellinus from

Except for a few remains, the air raid of 1942 destroyed all the windows, including the stained glass windows that

Except for a few remains, the air raid of 1942 destroyed all the windows, including the stained glass windows that

The war memorial, created in 1929 by the sculptor 1929 on behalf of the congregation of the church to commemorate their dead, is made of Swedish granite from

The war memorial, created in 1929 by the sculptor 1929 on behalf of the congregation of the church to commemorate their dead, is made of Swedish granite from

St. Mary's is known to have had an organ in the 14th century, since the occupation "organist" is mentioned in a will from 1377.

The old great organ was built in 1516–1518 under the direction of Martin Flor on the west wall as a replacement for the great organ of 1396. It had 32 stops, 2

St. Mary's is known to have had an organ in the 14th century, since the occupation "organist" is mentioned in a will from 1377.

The old great organ was built in 1516–1518 under the direction of Martin Flor on the west wall as a replacement for the great organ of 1396. It had 32 stops, 2

The Dance macabre organ () was older than the old great organ.

It was installed in 1477 on the east side of the north arm of the "transept" in the Danse Macabre Chapel (so named because of the ''Danse Macabre'' painting that hung there) and was used for the musical accompaniment of the

The Dance macabre organ () was older than the old great organ.

It was installed in 1477 on the east side of the north arm of the "transept" in the Danse Macabre Chapel (so named because of the ''Danse Macabre'' painting that hung there) and was used for the musical accompaniment of the

The

The

The 11 historic bells of the church originally hung in the South Tower in a bell loft high.

An additional seven bells for sounding the time were made by in 1508–1510 and installed in the roof spire. During the fire in the air raid of 1942, the bells are reported to have rung again in the upwind before crashing to the ground.

The remains of two bells, the oldest bell, the "Sunday bell" by Heinrich von Kampen (, diameter ,

The 11 historic bells of the church originally hung in the South Tower in a bell loft high.

An additional seven bells for sounding the time were made by in 1508–1510 and installed in the roof spire. During the fire in the air raid of 1942, the bells are reported to have rung again in the upwind before crashing to the ground.

The remains of two bells, the oldest bell, the "Sunday bell" by Heinrich von Kampen (, diameter ,

Official Web site

{{DEFAULTSORT:Marys Church, Lubeck Buildings and structures completed in 1350 14th-century churches in Germany Lubeck Mary Lubeck Mary Churches in Lübeck Lubeck Mary Heritage sites in Schleswig-Holstein

basilica

In Ancient Roman architecture, a basilica is a large public building with multiple functions, typically built alongside the town's forum. The basilica was in the Latin West equivalent to a stoa in the Greek East. The building gave its nam ...

in the city centre of Lübeck

Lübeck (; Low German also ), officially the Hanseatic City of Lübeck (german: Hansestadt Lübeck), is a city in Northern Germany. With around 217,000 inhabitants, Lübeck is the second-largest city on the German Baltic coast and in the state ...

, Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwee ...

. Built between 1265 and 1352, the church is located on the highest point of Lübeck's old town island within the Hanseatic merchants' quarter, which extends uphill from the warehouse

A warehouse is a building for storing goods. Warehouses are used by manufacturers, importers, exporters, wholesalers, transport businesses, customs, etc. They are usually large plain buildings in industrial parks on the outskirts of citie ...

s on the River Trave

The Trave () is a river in Schleswig-Holstein, Germany. It is approximately long, running from its source near the village of Gießelrade in Ostholstein to Travemünde, where it flows into the Baltic Sea. It passes through Bad Segeberg, Bad Old ...

to the church. As the main parish church

A parish church (or parochial church) in Christianity is the church which acts as the religious centre of a parish. In many parts of the world, especially in rural areas, the parish church may play a significant role in community activities, ...

of the citizens and the city council of Lübeck, it was built close to the town hall and the market.

The church was built as a three-aisled basilica

In Ancient Roman architecture, a basilica is a large public building with multiple functions, typically built alongside the town's forum. The basilica was in the Latin West equivalent to a stoa in the Greek East. The building gave its nam ...

with side chapel

A chapel is a Christian place of prayer and worship that is usually relatively small. The term has several meanings. Firstly, smaller spaces inside a church that have their own altar are often called chapels; the Lady chapel is a common type ...

s, an ambulatory

The ambulatory ( la, ambulatorium, ‘walking place’) is the covered passage around a cloister or the processional way around the east end of a cathedral or large church and behind the high altar. The first ambulatory was in France in the 11th ...

with radiating chapels

An apse chapel, apsidal chapel, or chevet is a chapel in traditional Christian church architecture, which radiates tangentially from one of the bays or divisions of the apse. It is reached generally by a semicircular passageway, or ambulatory, ex ...

, and vestibules like the arms of a transept. The westwork

A westwork (german: Westwerk), forepart, avant-corps or avancorpo is the monumental, often west-facing entrance section of a Carolingian, Ottonian, or Romanesque church. The exterior consists of multiple stories between two towers. The interio ...

has a monumental two-tower façade. The height of the towers, including the weather vane

A wind vane, weather vane, or weathercock is an instrument used for showing the direction of the wind. It is typically used as an architectural ornament to the highest point of a building. The word ''vane'' comes from the Old English word , m ...

s, is and , respectively. It has the tallest brick vault

Vault may refer to:

* Jumping, the act of propelling oneself upwards

Architecture

* Vault (architecture), an arched form above an enclosed space

* Bank vault, a reinforced room or compartment where valuables are stored

* Burial vault (enclosure ...

in the world, the height of the central nave being .

St Mary's epitomizes north German

Northern Germany (german: link=no, Norddeutschland) is a linguistic, geographic, socio-cultural and historic region in the northern part of Germany which includes the coastal states of Schleswig-Holstein, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern and Lower Saxony an ...

Brick Gothic

Brick Gothic (german: Backsteingotik, pl, Gotyk ceglany, nl, Baksteengotiek) is a specific style of Gothic architecture common in Northeast and Central Europe especially in the regions in and around the Baltic Sea, which do not have resourc ...

and set the standard for about 70 other churches in the Baltic region

The terms Baltic Sea Region, Baltic Rim countries (or simply the Baltic Rim), and the Baltic Sea countries/states refer to slightly different combinations of countries in the general area surrounding the Baltic Sea, mainly in Northern Europe. ...

, making it a building of enormous architectural significance. It is referred to as the "mother church of brick Gothic" and is considered a major work of church building in the Baltic Sea region. Because of its architectural importance and testimony to the medieval influence of the Hanseatic League (of which Lübeck was the ''de facto'' capital), in 1987 St Mary's Church was inscribed on the UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a List of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) aimed at promoting world peace and security through international coope ...

World Heritage List

A World Heritage Site is a landmark or area with legal protection by an international convention administered by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). World Heritage Sites are designated by UNESCO for ...

along with the Lübeck City Centre. St Mary's is part of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Northern Germany.

History of the building

In 1160,

In 1160, Henry the Lion

Henry the Lion (german: Heinrich der Löwe; 1129/1131 – 6 August 1195) was a member of the Welf dynasty who ruled as the duke of Saxony and Bavaria from 1142 and 1156, respectively, until 1180.

Henry was one of the most powerful German p ...

moved the Bishopric of Oldenburg

In church governance, a diocese or bishopric is the ecclesiastical district under the jurisdiction of a bishop.

History

In the later organization of the Roman Empire, the increasingly subdivided provinces were administratively associat ...

to Lübeck

Lübeck (; Low German also ), officially the Hanseatic City of Lübeck (german: Hansestadt Lübeck), is a city in Northern Germany. With around 217,000 inhabitants, Lübeck is the second-largest city on the German Baltic coast and in the state ...

and established a cathedral chapter

According to both Catholic and Anglican canon law, a cathedral chapter is a college of clerics ( chapter) formed to advise a bishop and, in the case of a vacancy of the episcopal see in some countries, to govern the diocese during the vacancy. ...

in the south of the old city island.

After 1160, a wooden church was built on the site of the Marienkirche in the middle of the town, which was first documented in 1170 together with St. Petri as a market church. Already at the end of the 12th century it was replaced by a Romanesque brick church that existed until the middle of the 13th century. Romanesque sculptures from the furnishings of this second Marienkirche are now on display in the St. Annen Museum. The sixth pair of pillars in the nave (from the west) dating from around 1200 can be seen as a remnant of the Romanesque Marienkirche in today's High Gothic building.

The design of the three-aisled basilica was based on the Gothic cathedrals in France (➜Reims) and Flanders

Flanders (, ; Dutch: ''Vlaanderen'' ) is the Flemish-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to cultu ...

, which were built of natural stone. St. Mary's is the epitome of ecclesiastical Brick Gothic architecture and set the standard for many churches in the Baltic region, such as the St. Nicholas Church in Stralsund

Stralsund (; Swedish: ''Strålsund''), officially the Hanseatic City of Stralsund (German: ''Hansestadt Stralsund''), is the fifth-largest city in the northeastern German federal state of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania after Rostock, Schwerin, N ...

and St. Nicholas

Saint Nicholas of Myra, ; la, Sanctus Nicolaus (traditionally 15 March 270 – 6 December 343), also known as Nicholas of Bari, was an early Christian bishop of Greek descent from the maritime city of Myra in Asia Minor (; modern-day Demre ...

in Wismar

Wismar (; Low German: ''Wismer''), officially the Hanseatic City of Wismar (''Hansestadt Wismar'') is, with around 43,000 inhabitants, the sixth-largest city of the northeastern German state of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, and the fourth-largest cit ...

.

No one had ever before built a brick church this high and with a vaulted ceiling

In architecture, a vault (French ''voûte'', from Italian ''volta'') is a self-supporting arched form, usually of stone or brick, serving to cover a space with a ceiling or roof. As in building an arch, a temporary support is needed while ring ...

.

The lateral thrust

Thrust is a reaction force described quantitatively by Newton's third law. When a system expels or accelerates mass in one direction, the accelerated mass will cause a force of equal magnitude but opposite direction to be applied to that ...

exerted by the vault is met by buttress

A buttress is an architectural structure built against or projecting from a wall which serves to support or reinforce the wall. Buttresses are fairly common on more ancient buildings, as a means of providing support to act against the lateral (s ...

es, making the enormous height possible. The motive for the Lübeck town council to embark on such an ambitious undertaking was the acrimonious relationship with the Bishopric of Lübeck

In church governance, a diocese or bishopric is the ecclesiastical district under the jurisdiction of a bishop.

History

In the later organization of the Roman Empire, the increasingly subdivided provinces were administratively associat ...

.

The church was built close to the Lübeck Town Hall and the market, and it dwarfed the nearby Romanesque Lübeck Cathedral

Lübeck Cathedral (german: Dom zu Lübeck, or colloquially ''Lübecker Dom'') is a large brick-built Lutheran cathedral in Lübeck, Germany and part of the Lübeck World Heritage Site. It was started in 1173 by Henry the Lion as a cathedral for ...

, the church of the bishop established by Henry the Lion

Henry the Lion (german: Heinrich der Löwe; 1129/1131 – 6 August 1195) was a member of the Welf dynasty who ruled as the duke of Saxony and Bavaria from 1142 and 1156, respectively, until 1180.

Henry was one of the most powerful German p ...

. It was meant as a symbol of the desire for freedom on the part of the Hanseatic traders and the secular authorities of the city, which had been granted the status of a free imperial city

In the Holy Roman Empire, the collective term free and imperial cities (german: Freie und Reichsstädte), briefly worded free imperial city (', la, urbs imperialis libera), was used from the fifteenth century to denote a self-ruling city that ...

(), making the city directly subordinate to the emperor, in 1226. It was also intended to underscore the pre-eminence of the city in relation to the other cities of the Hanseatic League

The Hanseatic League (; gml, Hanse, , ; german: label= Modern German, Deutsche Hanse) was a medieval commercial and defensive confederation of merchant guilds and market towns in Central and Northern Europe. Growing from a few North German to ...

, which was being formed at about the same time (1356).

The Chapel of Indulgences () was added to the east of the south tower in 1310. It was both a vestibule and a chapel and, with its portal, was the church's second main entrance from the market.

Probably originally dedicated to Saint Anne

According to Christian apocryphal and Islamic tradition, Saint Anne was the mother of Mary and the maternal grandmother of Jesus. Mary's mother is not named in the canonical gospels. In writing, Anne's name and that of her husband Joachim come o ...

, the chapel received its current name during the Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

, when paid scribes moved in. The chapel, which is long, deep, and high, has a stellar vault ceiling and is considered a masterpiece of High Gothic

High Gothic is a particularly refined and imposing style of Gothic architecture that appeared in northern France from about 1195 until 1250. Notable examples include Chartres Cathedral, Reims Cathedral, Amiens Cathedral, Beauvais Cathedral, and ...

architecture. It has often been compared to English Gothic

English Gothic is an architectural style that flourished from the late 12th until the mid-17th century. The style was most prominently used in the construction of cathedrals and churches. Gothic architecture's defining features are pointed ar ...

Cathedral Architecture and the chapter house

A chapter house or chapterhouse is a building or room that is part of a cathedral, monastery or collegiate church in which meetings are held. When attached to a cathedral, the cathedral chapter meets there. In monasteries, the whole commun ...

of Malbork Castle

The Castle of the Teutonic Order in Malbork ( pl, Zamek w Malborku; german: Ordensburg Marienburg) is a 13th-century Teutonic castle and fortress located near the town of Malbork, Poland. It is the largest castle in the world measured by land ...

. Today the Chapel of Indulgences serves the community as a church during winter, with services from January to March.

In 1289 the town council built its own chapel, known as the (Burgomasters' Chapel), at the southeast corner of the ambulatory

The ambulatory ( la, ambulatorium, ‘walking place’) is the covered passage around a cloister or the processional way around the east end of a cathedral or large church and behind the high altar. The first ambulatory was in France in the 11th ...

, the join being visible from the outside where there is a change from glazed to unglazed brick. It was in this chapel, from the large pew that still survives, that the newly elected council used to be installed. On the upper floor of the chapel is the treasury, where important documents of the city were kept. This part of the church is still in the possession of the town.

Before 1444, a chapel consisting of a single bay was added to the eastern end of the ambulatory, its five walls forming five-eighths of an octagon. This was the last Gothic extension to the church. It was used for celebrating the so-called Hours of the Virgin

The Little Office of the Blessed Virgin Mary, also known as Hours of the Virgin, is a liturgical devotion to the Blessed Virgin Mary, in imitation of, and usually in addition to, the Divine Office in the Catholic Church. It is a cycle of psalms, ...

, as part of the veneration of the Virgin Mary, reflected in its name (Our Lady's Hours Chapel) or (Singers' Chapel).

In total, St Mary's Church has nine larger chapels and ten smaller ones that serve as sepulchral chapels and are named after the families of the Lübeck city council that used them and endowed them.

Destruction and restoration

In an air raid by the

In an air raid by the RAF

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

on 28-29 March 1942 – the night of Palm Sunday

Palm Sunday is a Christian moveable feast that falls on the Sunday before Easter. The feast commemorates Christ's triumphal entry into Jerusalem, an event mentioned in each of the four canonical Gospels. Palm Sunday marks the first day of Hol ...

– the church was almost completely destroyed by fire, together with about a fifth of the Lübeck city centre, including Lübeck Cathedral

Lübeck Cathedral (german: Dom zu Lübeck, or colloquially ''Lübecker Dom'') is a large brick-built Lutheran cathedral in Lübeck, Germany and part of the Lübeck World Heritage Site. It was started in 1173 by Henry the Lion as a cathedral for ...

and .

Among the artefacts destroyed was the famous (Danse Macabre

The ''Danse Macabre'' (; ) (from the French language), also called the Dance of Death, is an artistic genre of allegory of the Late Middle Ages on the universality of death.

The ''Danse Macabre'' consists of the dead, or a personification of ...

organ

Organ may refer to:

Biology

* Organ (biology), a part of an organism

Musical instruments

* Organ (music), a family of keyboard musical instruments characterized by sustained tone

** Electronic organ, an electronic keyboard instrument

** Hammond ...

), an instrument played by Dieterich Buxtehude

Dieterich Buxtehude (; ; born Diderik Hansen Buxtehude; c. 1637 – 9 May 1707) was a Danish organist and composer of the Baroque period, whose works are typical of the North German organ school. As a composer who worked in various vocal a ...

and probably Johann Sebastian Bach

Johann Sebastian Bach (28 July 1750) was a German composer and musician of the late Baroque period. He is known for his orchestral music such as the '' Brandenburg Concertos''; instrumental compositions such as the Cello Suites; keyboard wo ...

. Other works of art destroyed in the fire include the ''Mass of Saint Gregory

The Mass of Saint Gregory is a subject in Roman Catholic art which first appears in the late Middle Ages and was still found in the Counter-Reformation. Pope Gregory I (c. 540–604) is shown saying Mass just as a vision of Christ as the ''Man of ...

'' by Bernt Notke

Bernt Notke (; – before May 1509) was a late Gothic artist, working in the Baltic region. He has been described as one of the foremost artists of his time in northern Europe.

Life

Very little is known about the life of Bernt Notke. The No ...

, the monumental ''Danse Macabre

The ''Danse Macabre'' (; ) (from the French language), also called the Dance of Death, is an artistic genre of allegory of the Late Middle Ages on the universality of death.

The ''Danse Macabre'' consists of the dead, or a personification of ...

'', originally by Bernt Notke but replaced by a copy in 1701, the carved figures of the rood screen

The rood screen (also choir screen, chancel screen, or jubé) is a common feature in late medieval church architecture. It is typically an ornate partition between the chancel and nave, of more or less open tracery constructed of wood, stone, o ...

, the Trinity altarpiece by Jacob van Utrecht

Jacob Claesz van Utrecht, also named by his signature Jacobus Traiectensis (c. 1479 – after 1525) was a Flemish early Renaissance painter who worked in Antwerp and Lübeck.

Life

Few details are known of Jacob van Utrecht's life. Research ...

(formerly also attributed to Bernard van Orley

Bernard van Orley (between 1487 and 1491 – 6 January 1541), also called Barend or Barent van Orley, Bernaert van Orley or Barend van Brussel, was a versatile Flemish artist and representative of Dutch and Flemish Renaissance painting, who w ...

) and the ''Entrance of Christ into Jerusalem'' by Friedrich Overbeck

Johann Friedrich Overbeck (3 July 1789 – 12 November 1869) was a German painter. As a member of the Nazarene movement, he also made four etchings.

Early life and education

Born in Lübeck, his ancestors for three generations had been Pro ...

. Sculptures by the woodcarver Benedikt Dreyer were also lost in the fire: the wooden statues of the saints on the west side of the rood screen and the organ sculpture on the great organ from around 1516–18 and ''Man with Counting Board''.

Also destroyed in the fire were the mediaeval stained glass window

Stained glass is coloured glass as a material or works created from it. Throughout its thousand-year history, the term has been applied almost exclusively to the windows of churches and other significant religious buildings. Although tradition ...

s from the , which were installed in St. Mary's Church from 1840 on, after the St. Mary Magdalene Church was demolished because it was in danger of collapse. Photographs by Lübeck photographers like give an impression of what the interior looked like before the War

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, destruction, and mortality, using regular o ...

.

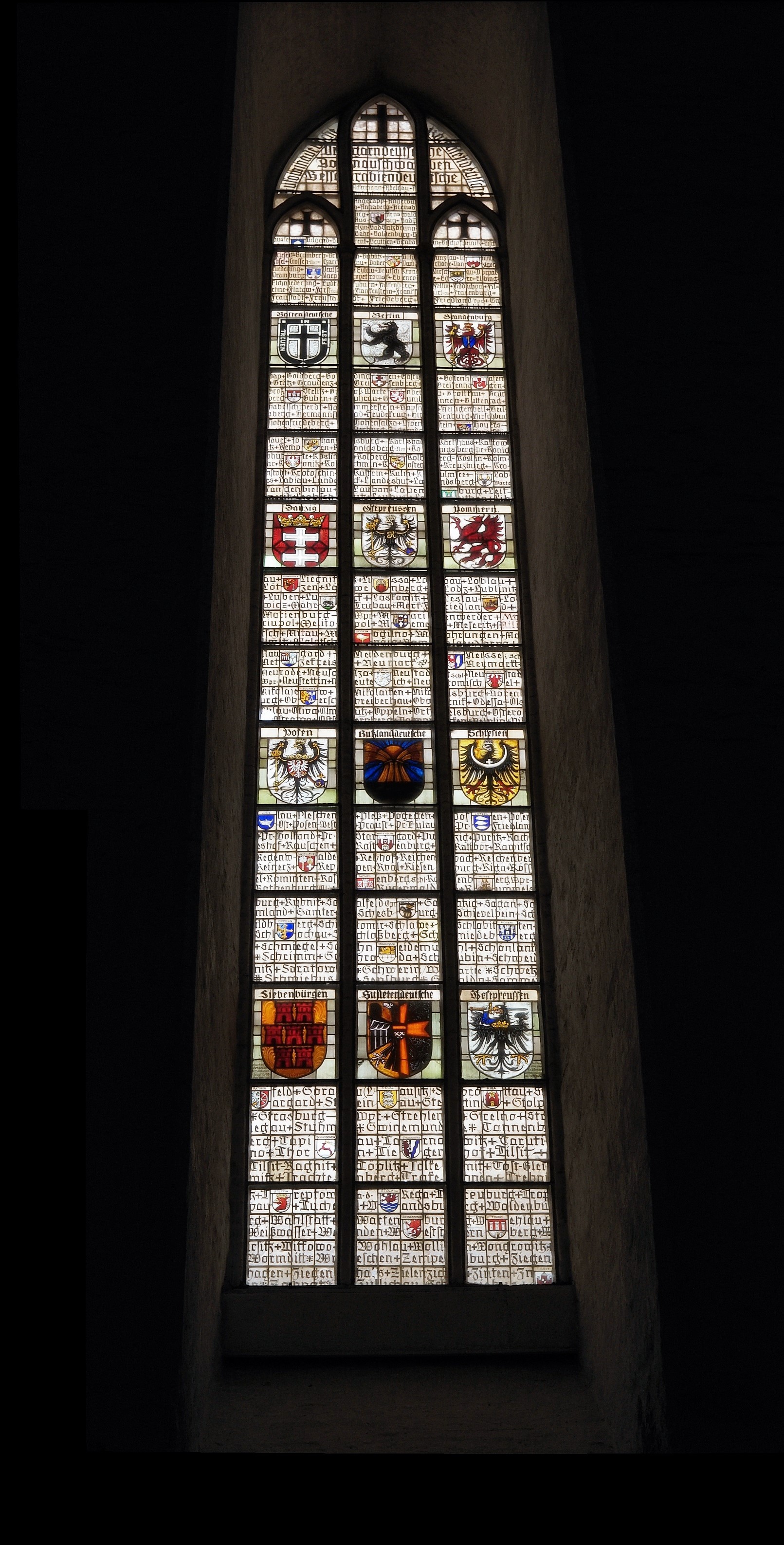

The glass window in one of the chapels has an alphabetic list of major towns in the pre-1945 eastern territory of the German Reich. Because of the destruction it suffered in World War II, St. Mary's Church is one of the Cross of Nails centres. A plaque on the wall warns of the futility of war.

The church was protected by a makeshift roof for the rest of the war, and the vaulted ceiling of the chancel was repaired. Reconstruction proper began in 1947, and was largely complete by 1959. In view of the previous damage by fire, the old wooden construction of the roof and spires was not replaced by a new wooden construction. All church spires in Lübeck were reconstructed using a special system involving lightweight concrete blocks underneath the copper roofing. The copper covering matched the original design and the concrete roof would avoid the possibility of a second fire. A glass window on the north side of the church commemorates the builder, , who invented this system.

In 1951, the 700th anniversary of the church was celebrated under the reconstructed roof; for the occasion, Chancellor

In 1951, the 700th anniversary of the church was celebrated under the reconstructed roof; for the occasion, Chancellor Konrad Adenauer

Konrad Hermann Joseph Adenauer (; 5 January 1876 – 19 April 1967) was a German statesman who served as the first chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany from 1949 to 1963. From 1946 to 1966, he was the first leader of the Christian Dem ...

donated the new tenor bell, and the Memorial Chapel Against War with broken bells in the South Tower was inaugurated.

In the 1950s, there was a long debate about the design of the interior, not just the paintings (see below). The predominant view was that destruction had restored the essential, pure form. The redesign was intended to facilitate the dual function that St. Mary's had at that time, being both the diocesan church and the parish church. In the end, the church held a limited competition, inviting submissions from six architects, including and , the latter's design being largely accepted on 8 February 1958. At the meeting, the bishop, , vehemently – and successfully – demanded the removal of the Fredenhagen altar (see below).

The redesign of the interior according to Boniver's plans was carried out in 1958–59. Since underfloor heating was being installed under a completely new floor, the remaining memorial slabs of Gotland limestone were removed and used to raise the level of the chancel. The chancel was separated from the ambulatory by whitewashed walls high. The Fredenhagen altar was replaced by a plain altar base of muschelkalk

The Muschelkalk (German for "shell-bearing limestone"; french: calcaire coquillier) is a sequence of sedimentary rock strata (a lithostratigraphic unit) in the geology of central and western Europe. It has a Middle Triassic (240 to 230 million ...

limestone and a crucifix by Gerhard Marcks

Gerhard Marcks (18 February 1889 – 13 November 1981) was a German artist, known primarily as a sculptor, but who is also known for his drawings, woodcuts, lithographs and ceramics.

Early life

Marcks was born in Berlin, where, at the age of 18, ...

suspended from the transverse arch of the ceiling. The inauguration of the new chancel was on 20 December 1959.

At the same time, a treasure chamber was made for the Danzig Parament

Paraments or parements (from Late Latin ''paramentum'', adornment, ''parare'', to prepare, equip) are both the hangings or ornaments of a room of state, and the ecclesiastical vestments. Paraments include the liturgical hangings on and around ...

Treasure from St. Mary's Church in Danzig (now Gdańsk), which was transferred to Lübeck after the War. The Parament Treasure is now exhibited at St. Anne's Museum), where a large organ loft had been built. The organ itself was not installed until 1968.

The gilded roof spire, which extends higher than the nave roof, was recreated from old designs and photographs in 1980.

Lothar Malskat and the frescos

The heat of the blaze in 1942 dislodged large sections of plaster, revealing the original decorative paintings of the Middle Ages, some of which were documented by photograph during the Second World War. In 1948 the task of restoring these gothicfresco

Fresco (plural ''frescos'' or ''frescoes'') is a technique of mural painting executed upon freshly laid ("wet") lime plaster. Water is used as the vehicle for the dry-powder pigment to merge with the plaster, and with the setting of the plast ...

s was given to Dietrich Fey. In what became the largest counterfeit art scandal after the Second World War, Fey hired local painter Lothar Malskat to assist with this task, and together they used the photographic documentation to restore and recreate a likeness to the original walls. Since no paintings of the clerestory

In architecture, a clerestory ( ; , also clearstory, clearstorey, or overstorey) is a high section of wall that contains windows above eye level. Its purpose is to admit light, fresh air, or both.

Historically, ''clerestory'' denoted an upper l ...

of the chancel were available, Fey had Malskat invent one. Malskat "supplemented" the restorations with his own work in the style of the 14th century. The forgery was only cleared up after Malskat reported his deeds to the authorities in 1952, and he and Fey received prison sentences in 1954.

The major fakes were later removed from the walls, on the instructions of the bishop.

Lothar Malskat played an important part in the novel '' The Rat'' by Günter Grass

Günter Wilhelm Grass (born Graß; ; 16 October 1927 – 13 April 2015) was a German novelist, poet, playwright, illustrator, graphic artist, sculptor, and recipient of the 1999 Nobel Prize in Literature.

He was born in the Free City of D ...

.

Interior decoration

St. Mary's Church was generously endowed with donations from the city council, the guilds, families, and individuals. At the end of the

St. Mary's Church was generously endowed with donations from the city council, the guilds, families, and individuals. At the end of the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

it had 38 altars and 65 benefices

A benefice () or living is a reward received in exchange for services rendered and as a retainer for future services. The Roman Empire used the Latin term as a benefit to an individual from the Empire for services rendered. Its use was adopted by ...

.

The following mediaeval artefacts remain:

* A bronze baptismal font

A baptismal font is an article of church furniture used for baptism.

Aspersion and affusion fonts

The fonts of many Christian denominations are for baptisms using a non-immersive method, such as aspersion (sprinkling) or affusion (pouring). ...

made by (1337). Until 1942 it was at the west end of the church; it is now in the middle of the chancel. It holds , almost the same as a Hamburg or Bremen beer barrel, which holds .

* Darsow Madonna from 1420, heavily damaged in 1942, restored from hundreds of individual pieces, put back in place again in 1989

* Tabernacle

According to the Hebrew Bible, the tabernacle ( he, מִשְׁכַּן, mīškān, residence, dwelling place), also known as the Tent of the Congregation ( he, link=no, אֹהֶל מוֹעֵד, ’ōhel mō‘ēḏ, also Tent of Meeting, etc.), ...

from 1479, high, made by using about 1000 individual bronze parts, some gilded, on the north wall of the chancel

*Winged altarpiece by Christian Swarte () with Woman of the Apocalypse

The Woman of the Apocalypse (or the woman clothed with the sun, el, γυνὴ περιβεβλημένη τὸν ἥλιον; Latin: ) is a figure, traditionally believed to be the Virgin Mary, described in Chapter 12 of the Book of Revelati ...

, now installed behind the main altar

* Bronze burial slab by Bernt Notke

Bernt Notke (; – before May 1509) was a late Gothic artist, working in the Baltic region. He has been described as one of the foremost artists of his time in northern Europe.

Life

Very little is known about the life of Bernt Notke. The No ...

for the Hutterock family (1505), in the Prayer Chapel () in the north ambulatory

* Of the rood screen

The rood screen (also choir screen, chancel screen, or jubé) is a common feature in late medieval church architecture. It is typically an ornate partition between the chancel and nave, of more or less open tracery constructed of wood, stone, o ...

destroyed in 1942 only an arch and the stone statues remain: Elizabeth

Elizabeth or Elisabeth may refer to:

People

* Elizabeth (given name), a female given name (including people with that name)

* Elizabeth (biblical figure), mother of John the Baptist

Ships

* HMS ''Elizabeth'', several ships

* ''Elisabeth'' (sch ...

with John the Baptist

John the Baptist or , , or , ;Wetterau, Bruce. ''World history''. New York: Henry Holt and Company. 1994. syc, ܝܘܿܚܲܢܵܢ ܡܲܥܡܕ݂ܵܢܵܐ, Yoḥanān Maʿmḏānā; he, יוחנן המטביל, Yohanān HaMatbil; la, Ioannes Bapti ...

as a child, Virgin and Child with Saint Anne, the Archangel Gabriel

In Abrahamic religions ( Judaism, Christianity and Islam), Gabriel (); Greek: grc, Γαβριήλ, translit=Gabriḗl, label=none; Latin: ''Gabriel''; Coptic: cop, Ⲅⲁⲃⲣⲓⲏⲗ, translit=Gabriêl, label=none; Amharic: am, ገብ ...

and Mary (Annunciation

The Annunciation (from Latin '), also referred to as the Annunciation to the Blessed Virgin Mary, the Annunciation of Our Lady, or the Annunciation of the Lord, is the Christian celebration of the biblical tale of the announcement by the ang ...

), John the Evangelist

John the Evangelist ( grc-gre, Ἰωάννης, Iōánnēs; Aramaic: ܝܘܚܢܢ; Ge'ez: ዮሐንስ; ar, يوحنا الإنجيلي, la, Ioannes, he, יוחנן cop, ⲓⲱⲁⲛⲛⲏⲥ or ⲓⲱ̅ⲁ) is the name traditionally given ...

and St. Dorothy.

* In the ambulatory, sandstone relief

Relief is a sculptural method in which the sculpted pieces are bonded to a solid background of the same material. The term '' relief'' is from the Latin verb ''relevo'', to raise. To create a sculpture in relief is to give the impression that th ...

s (1515) from the atelier of , with scenes from the Passion of Christ

In Christianity, the Passion (from the Latin verb ''patior, passus sum''; "to suffer, bear, endure", from which also "patience, patient", etc.) is the short final period in the life of Jesus Christ.

Depending on one's views, the "Passion" m ...

: to the north, the Washing of the Feet and the Last Supper

Image:The Last Supper - Leonardo Da Vinci - High Resolution 32x16.jpg, 400px, alt=''The Last Supper'' by Leonardo da Vinci - Clickable Image, Depictions of the Last Supper in Christian art have been undertaken by artistic masters for centuries, ...

; to the south, Christ in the garden of Gethsemane and his capture. The Last Supper relief includes a detail associated with Lübeck: a little mouse gnawing at the base of a rose bush. Touching it is supposed to mean that the person will never again return to Lübeck – or will have good luck, depending on the version of the superstition.

* Remains of the original pews and the (1518), in the Lady Chapel (Singers' Chapel)

* John the Evangelist

John the Evangelist ( grc-gre, Ἰωάννης, Iōánnēs; Aramaic: ܝܘܚܢܢ; Ge'ez: ዮሐንስ; ar, يوحنا الإنجيلي, la, Ioannes, he, יוחנן cop, ⲓⲱⲁⲛⲛⲏⲥ or ⲓⲱ̅ⲁ) is the name traditionally given ...

, a wooden statue by Henning von der Heide ()

* St. Anthony, a stone statue, donated in 1457 by the town councillor , a member of the Brotherhood of St. Anthony

* Remains of the original gothic pews in the Burgomasters' Chapel in the southern ambulatory

* The ''Lamentation of Christ'', one of the main works of the Nazarene Friedrich Overbeck

Johann Friedrich Overbeck (3 July 1789 – 12 November 1869) was a German painter. As a member of the Nazarene movement, he also made four etchings.

Early life and education

Born in Lübeck, his ancestors for three generations had been Pro ...

, in the Prayer Chapel in the north ambulatory

* The choir screens separating the choir from the ambulatory are recent reconstructions. The walls that had been built for this purpose in 1959 were removed in the 1990s. The brass bars of the choir screens were mostly still intact, but the wooden parts had been almost completely destroyed by fire in 1942. The oak crown and frame were reconstructed on the basis of what remained of the original construction.

Antwerp altarpiece

The in the Lady Chapel (Singers' Chapel) was created in 1518. It was donated for the chapel in 1522 by Johann Bone, a merchant fromGeldern

Geldern ( nl, Gelderen, archaic English: ''Guelder(s)'') is a city in the federal German state of North Rhine-Westphalia. It is part of the district of Kleve, which is part of the Düsseldorf

administrative region.

Geography

Location

Geldern l ...

.

After the chapel was converted into a confessional chapel in 1790, the altarpiece was moved around the church several times.

During the Second World War, it was in the Chapel of Indulgences () and thus escaped destruction.

The double-winged altarpiece depicts the life of the Virgin Mary in 26 painted and carved scenes.

* The fully closed position (nowadays, this is the position in the Christian Holy Week

Holy Week ( la, Hebdomada Sancta or , ; grc, Ἁγία καὶ Μεγάλη Ἑβδομάς, translit=Hagia kai Megale Hebdomas, lit=Holy and Great Week) is the most sacred week in the liturgical year in Christianity. In Eastern Churches, w ...

before Easter Sunday), shows the Annunciation

The Annunciation (from Latin '), also referred to as the Annunciation to the Blessed Virgin Mary, the Annunciation of Our Lady, or the Annunciation of the Lord, is the Christian celebration of the biblical tale of the announcement by the ang ...

by the Master of 1518.

*With one pair of wings open (as seen on fasting days) the paintings are of scenes from the lives of Jesus and Mary:

::in the centre are four paintings, depicting,

::: the Adoration of the Shepherds

::: the Adoration of the Magi

The Adoration of the Magi or Adoration of the Kings is the name traditionally given to the subject in the Nativity of Jesus in art in which the three Magi, represented as kings, especially in the West, having found Jesus by following a star, ...

::: the Circumcision of Jesus

The circumcision of Jesus is an event from the life of Jesus, according to the Gospel of Luke chapter 2, which states: And when eight days were fulfilled to circumcise the child, his name was called Jesus, the name called by the angel before ...

, and

::: the Flight into Egypt

The flight into Egypt is a story recounted in the Gospel of Matthew ( Matthew 2:13– 23) and in New Testament apocrypha. Soon after the visit by the Magi, an angel appeared to Joseph in a dream telling him to flee to Egypt with Mary and the ...

:: and the wings show

::: the marriage of Joachim

Joachim (; ''Yəhōyāqīm'', "he whom Yahweh has set up"; ; ) was, according to Christian tradition, the husband of Saint Anne and the father of Mary, the mother of Jesus. The story of Joachim and Anne first appears in the Biblical apocryph ...

and Anne

Anne, alternatively spelled Ann, is a form of the Latin female given name Anna. This in turn is a representation of the Hebrew Hannah, which means 'favour' or 'grace'. Related names include Annie.

Anne is sometimes used as a male name in the ...

,

::: the rejection of Joachim's sacrifice,

::: Joachim's sacrifice of thanksgiving, and

::: Joachim giving alms to the poor on leaving the temple.

*With both pairs of wings open (on feast days):

:: the carved centrepiece depicts

::: the Death of the Virgin Mary,

:::: with the death scene in the centre;

:::: above that was a group depicting the Assumption of Mary

The Assumption of Mary is one of the four Marian dogmas of the Catholic Church. Pope Pius XII defined it in 1950 in his apostolic constitution '' Munificentissimus Deus'' as follows:

We proclaim and define it to be a dogma revealed by ...

but it was stolen in 1945;

:::: below it is the funeral procession;

::: on the left is the Annunciation

The Annunciation (from Latin '), also referred to as the Annunciation to the Blessed Virgin Mary, the Annunciation of Our Lady, or the Annunciation of the Lord, is the Christian celebration of the biblical tale of the announcement by the ang ...

, and

::: on the right is Mary's entombment.

:: the carved left wing depicts

::: the birth of Mary at the top and

::: the Presentation of Jesus at the Temple

The Presentation of Jesus at the Temple (or ''in the temple'') is an early episode in the life of Jesus Christ, describing his presentation at the Temple in Jerusalem, that is celebrated by many churches 40 days after Christmas on Candlemas, o ...

at the bottom, and

::the carved right wing depicts

::: the Tree of Jesse

The Tree of Jesse is a depiction in art of the ancestors of Jesus Christ, shown in a branching tree which rises from Jesse of Bethlehem, the father of King David. It is the original use of the family tree as a schematic representation of a g ...

above, and

::: the twelve-year-old Jesus in the temple below.

Before 1869, the wings of the predella

In art a predella (plural predelle) is the lowest part of an altarpiece, sometimes forming a platform or step, and the painting or sculpture along it, at the bottom of an altarpiece, sometimes with a single much larger main scene above, but oft ...

, which depict the legends of the Holy Kinship

The Holy Kinship was the extended family of Jesus descended from his maternal grandmother Saint Anne from her ''trinubium'' or three marriages. The group were a popular subject in religious art throughout Germany and the Low Countries, especially ...

were removed, sawn to make panel paintings

A panel painting is a painting made on a flat panel of wood, either a single piece or a number of pieces joined together. Until canvas became the more popular support medium in the 16th century, panel painting was the normal method, when not paint ...

, and sold. In 1869, two such paintings from the private collection of the mayor of Lübeck were acquired for the collection in what is now St. Anne's Museum.

Two more paintings from the outsides of the predella wings were acquired by the ' (Cultural foundation of Schleswig-Holstein) and have been in St. Anne's Museum since 1988.

Of the remaining paintings, two are in the Staatsgalerie Stuttgart

The Staatsgalerie Stuttgart (, "State Gallery") is an art museum in Stuttgart, Germany, it opened in 1843. In 1984, the opening of the Neue Staatsgalerie (''New State Gallery'') designed by James Stirling transformed the once provincial gallery ...

and two are in a private collection in Stockholm.

Memorials

Gottfried Schadow

Johann Gottfried Schadow (20 May 1764 – 27 January 1850) was a German Prussian sculptor.

His most iconic work is the chariot on top of the Brandenburg Gate in Berlin, executed in 1793 when he was still only 29.

Biography

Schadow was born in ...

of mayor , which the Council presented to him in 1823 on the occasion of his anniversary as a member of the Council, and which was installed here in 1835.

Among the later memorials is also the gravestone of mayor by Landolin Ohmacht ().

The Fredenhagen Altarpiece

marble

Marble is a metamorphic rock composed of recrystallized carbonate minerals, most commonly calcite or dolomite. Marble is typically not foliated (layered), although there are exceptions. In geology, the term ''marble'' refers to metamorphose ...

and porphyry (1697) was seriously damaged in 1942.

After a lengthy debate lasting from 1951 to 1959, , the bishop at the time, prevailed, and it was decided not to restore the altar but to replace it with a simple altar of limestone, with a bronze crucifix made by Gerhard Marcks

Gerhard Marcks (18 February 1889 – 13 November 1981) was a German artist, known primarily as a sculptor, but who is also known for his drawings, woodcuts, lithographs and ceramics.

Early life

Marcks was born in Berlin, where, at the age of 18, ...

.

Speaking of the historical significance of the altar, the director of the Lübeck Museum at the time said that it was the only work of art of European stature that the Protestant Church in Lübeck had produced after the Reformation.

Individual items from the altarpiece are now in the ambulatory: the Calvary group with Mary and John, the marble predella with a relief of the Last Supper and the three crowned figures, the allegorical sculpture

Allegorical sculpture are sculptures of personifications of abstract ideas as in allegory. Common in the western world, for example, are statues of Lady Justice representing justice, traditionally holding scales and a sword, and the statues of Pru ...

s of Belief and Hope, and the Resurrected Christ.

The other remains of the altar and altarpiece are now stored over the vaulted ceiling between the towers.

The debate as to whether it is possible and desirable to restore the altar as a major work of baroque art of European stature is ongoing.

Stained glass

Carl Julius Milde

Carl Julius Milde (16 February 1803, in Hamburg – 19 November 1875, in Lübeck) was a German painter, curator and art restorer.

Life

His father was a grocer whose business had been nearly ruined by the French Occupation. After a financial ...

had installed at Saint Mary's after they were rescued from the when the St. Mary Magdalene's Priory was demolished in the 19th century, and including the windows made by Professor from Frankfurt in the late 19th century.

In the reconstruction, simple diamond-pane leaded windows

Leadlights, leaded lights or leaded windows are decorative windows made of small sections of glass supported in lead cames. The technique of creating windows using glass and lead came to be known as came glasswork. The term 'leadlight' could ...

were used, mostly just decorated with the coat of arms of the donor, though some windows had an artistic design.

* The windows in the Singers' Chapel (Lady Chapel) depict the coat of arms of the Hanseatic towns of Bremen, Hamburg and Lübeck, and the lyrics of Buxtehude's Lübeck cantata

A cantata (; ; literally "sung", past participle feminine singular of the Italian verb ''cantare'', "to sing") is a vocal composition with an instrumental accompaniment, typically in several movements, often involving a choir.

The meaning o ...

, (BuxWV

The Buxtehude-Werke-Verzeichnis ("Buxtehude Works Catalogue", commonly abbreviated to BuxWV) is the catalogue and the numbering system used to identify musical works by the German-Danish Baroque composer Dieterich Buxtehude (c. 1637 – 9 May 17 ...

96).

* The monumental west window, designed by , depicts the Day of Judgment

The Last Judgment, Final Judgment, Day of Reckoning, Day of Judgment, Judgment Day, Doomsday, Day of Resurrection or The Day of the Lord (; ar, یوم القيامة, translit=Yawm al-Qiyāmah or ar, یوم الدین, translit=Yawm ad-Dīn, ...

.

* The window of the Memorial chapel () in the South Tower (which holds the destroyed bells), depicts coats of arms of towns, states and provinces of former eastern territories of Germany

The former eastern territories of Germany (german: Ehemalige deutsche Ostgebiete) refer in present-day Germany to those territories east of the current eastern border of Germany i.e. Oder–Neisse line which historically had been considered Ger ...

.

* Both windows in the Danse Macabre Chapel (), which were designed by Alfred Mahlau in 1955/1956 and made in the Berkentien stained glass atelier in Lübeck, adopt motifs from the ''Danse Macabre'' painting that was destroyed by fire in 1942. They replace the (Emperor's Window), which was donated by ''Kaiser'' Wilhelm II

, house = Hohenzollern

, father = Frederick III, German Emperor

, mother = Victoria, Princess Royal

, religion = Lutheranism (Prussian United)

, signature = Wilhelm II, German Emperor Signature-.svg

Wilhelm II (Friedrich Wilhelm Viktor ...

on the occasion of his visit to Lübeck in 1913. It was manufactured by the Munich court stained glass artist and depicted the confirmation of the town privileges by Emperor Barbarossa

Frederick Barbarossa (December 1122 – 10 June 1190), also known as Frederick I (german: link=no, Friedrich I, it, Federico I), was the Holy Roman Emperor from 1155 until his death 35 years later. He was elected King of Germany in Frankfurt o ...

.

* In 1981–82, windows by Johannes Schreiter

Johannes Schreiter (born 8 March 1930) is a German graphic artist, printmaker, designer of stained glass, theoretician and cultural critic. Born in Buchholz in 1930, Schreiter studied in Munster, Mainz, and Berlin, before receiving a scholarship ...

were installed in the Chapel of Indulgences ''(''). Their ragged diamond pattern evokes not only the destruction of the church but also the torn nets of the Disciple

A disciple is a follower and student of a mentor, teacher, or other figure. It can refer to:

Religion

* Disciple (Christianity), a student of Jesus Christ

* Twelve Apostles of Jesus, sometimes called the Twelve Disciples

* Seventy disciples in t ...

s ().

* In December 2002, the tympanum window was added above the north portal of the Danse Macabre Chapel after a design by Markus Lüpertz.

This window, like the windows by Johannes Schreiter in the Chapel of Indulgences (), was manufactured and assembled by Derix Glass Studios in Taunusstein

Taunusstein () is the biggest town in the Rheingau-Taunus-Kreis in the ''Regierungsbezirk'' of Darmstadt in Hessen, Germany. It has 30,068 inhabitants (2020).

Geography

Location

Taunusstein lies roughly 10 km northwest of Wiesbaden and ab ...

.

Churchyard

, with its views of the north face of the , the ', and the ' has the ambiance of a mediaeval town. The architectural features include the subjects of Lübeck legends; a large block of granite to the right of the entrance was supposedly not left there by the builders but put there by the Devil. To the north and west of the church, the courtyard is now an open space, mediaeval buildings having been removed. At the corner between and are the remaining stone foundations of the Chapel (1415), which served as a bookshop before the Second World War. In the late 1950s, it was decided not to reconstruct it, and the remaining external walls of the ruins were cleared away. On Mengstraße, opposite the churchyard, is a building with facades from the 18th century: theclergy house

A clergy house is the residence, or former residence, of one or more priests or ministers of religion. Residences of this type can have a variety of names, such as manse, parsonage, rectory or vicarage.

Function

A clergy house is typically ow ...

known as die , which also gave its name to the courtyard that lies behind it, the .

The war memorial, created in 1929 by the sculptor 1929 on behalf of the congregation of the church to commemorate their dead, is made of Swedish granite from

The war memorial, created in 1929 by the sculptor 1929 on behalf of the congregation of the church to commemorate their dead, is made of Swedish granite from Karlshamn

Karlshamn () is a locality and the seat of Karlshamn Municipality in Blekinge County, Sweden. It had 13,576 inhabitants in 2015, out of 31,846 in the municipality.

Karlshamn received a Royal Charter and city privileges in 1664, when King Charles ...

.

The inscription reads (in translation):

Pastors

Since the Reformation, St. Mary's Church has been where the top Lutheran clergyman of the city preached. Until 1796 this was thesuperintendent

Superintendent may refer to:

*Superintendent (police), Superintendent of Police (SP), or Senior Superintendent of Police (SSP), a police rank

*Prison warden or Superintendent, a prison administrator

*Superintendent (ecclesiastical), a church exec ...

.

After that, Lübeck's senior clergymen varied; three of them were pastors at St. Mary's

From 1934 to 1973 St. Mary's was the church of the bishop of the .

Since the establishment of the North Elbian Evangelical Lutheran Church

The North Elbian Evangelical Lutheran Church (german: link=no, Nordelbische Evangelisch-Lutherische Kirche; NEK) was a Lutheran regional church in Northern Germany which emerged from a merger of four churches in 1977 and merged with two more churc ...

, St. Mary has been where the provost responsible for Lübeck has preached.

Since the establishment of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Northern Germany in 2012 St. Mary's has been the church of the provost for the area of Lübeck within the church district of Lübeck–Lauenburg.

* 1532–1548:

* 1553–1567:

* 1575–1600:

* 1613–1622:

* 1624–1643: Nicolaus Hunnius

* 1646–1671:

* 1675–1683:

* 1689–1698:

* 1702–1728:

* 1730–1767: Johann Gottlob Carpzov

* 1771–1774:

* 1779–1796:

* 1892–1909:

* 1914–1919:

* 1919–1933:

* 1934–1945: , bishop

* 1948–1955: , bishop

* 1956–1972:

* 1972–1977: , senior clergyman

* 1979–2001: , provost

* 2001–2008: Ralf Meister

Ralf Meister (born 5 January 1962 in Hamburg-Neugraben) is a German Lutheran theologian, former General Superintendent (regional bishop) of Berlin, and Landesbischof of the Evangelical-Lutheran Church of Hanover.

Meister studied at the Universit ...

, provost

* Since 2008: Petra Kallies, provost

Other famous pastors at St. Mary's were:

* 1614–1648: , priest from 1614, principal pastor from 1625

* 1626–1668: Jacob Stolterfoht, priest from 1626, principal pastor from 1649

* 1706–1743: , principal pastor and Polyhistor

A polymath ( el, πολυμαθής, , "having learned much"; la, homo universalis, "universal human") is an individual whose knowledge spans a substantial number of subjects, known to draw on complex bodies of knowledge to solve specific pro ...

* 1743–1750: , priest

* 1751–1759: , principal pastor

* 1829–1867: , principal pastor

* 1832–1884:

* 1966–1979:

Once there were three generations in succession:

* 1713–1750: , priest from 1713, principal pastor from 1743

* 1757–1795: , priest from 1757, principal pastor from 1775, senior clergyman from 1788

* 1794–1828: , 1794 priest, from 1800 principal pastor.

Music at St. Mary's

Music played an important part in the life of St. Mary's as far back as the Middle Ages. The Lady Chapel (Singers' Chapel), for instance, had its own choir. After the Reformation andJohannes Bugenhagen

Johannes Bugenhagen (24 June 1485 – 20 April 1558), also called ''Doctor Pomeranus'' by Martin Luther, was a German theologian and Lutheran priest who introduced the Protestant Reformation in the Duchy of Pomerania and Denmark in the 16th ce ...

's Church Order

Church order is the systematically organized set of rules drawn up by a qualified body of a local church. P. Coertzen. ''Church and Order''. Belgium: Peeters. From the point of view of civil law, the ''church order'' can be described as the inter ...

, the Lübeck Katharineum

The Katharineum zu Lübeck is a humanistic gymnasium founded 1531 in the Hanseatic city Lübeck, Germany. In 2006 the 475th anniversary of this Latin school was celebrated with several events. The school uses the buildings of a former Francisca ...

school choir provided the singing for religious services.

In return the school received the income of the chapel's trust fund.

Until 1802, the cantor

A cantor or chanter is a person who leads people in singing or sometimes in prayer. In formal Jewish worship, a cantor is a person who sings solo verses or passages to which the choir or congregation responds.

In Judaism, a cantor sings and lead ...

was both a teacher at the school and responsible for the singing of the choir and the congregation.

The organist

An organist is a musician who plays any type of organ. An organist may play solo organ works, play with an ensemble or orchestra, or accompany one or more singers or instrumental soloists. In addition, an organist may accompany congregational ...

was responsible for the organ music and other instrumental music; he also had administrative and accounting responsibilities and was responsible for the upkeep of the building.

Main organ

St. Mary's is known to have had an organ in the 14th century, since the occupation "organist" is mentioned in a will from 1377.

The old great organ was built in 1516–1518 under the direction of Martin Flor on the west wall as a replacement for the great organ of 1396. It had 32 stops, 2

St. Mary's is known to have had an organ in the 14th century, since the occupation "organist" is mentioned in a will from 1377.

The old great organ was built in 1516–1518 under the direction of Martin Flor on the west wall as a replacement for the great organ of 1396. It had 32 stops, 2 manual

Manual may refer to:

Instructions

* User guide

* Owner's manual

An owner's manual (also called an instruction manual or a user guide) is an instructional book or booklet that is supplied with almost all technologically advanced consumer ...

s and a pedalboard.

This organ, "in all probability the first and only Gothic organ with a thirty-two-foot principal (deepest pipe, 11 metres long) in the western world of the time", was repeatedly expanded and rebuilt over the centuries.

For instance, the organist and organ-builder Barthold Hering (who died in 1555) carried out a number of repairs and additions; in 1560/1561 Jacob Scherer added a chest division with a third manual.

From 1637 to 1641, Friederich Stellwagen

Friederich Stellwagen (baptized 7 February 1603 – buried 2 March 1660) was a pipe organ builder active in the region of northeast Germany between Hamburg and Stralsund in the mid 17th century. He learned with Gottfried Fritzsche and eventua ...

carried out a number of modifications.

added three registers in 1704.

In 1733, Konrad Büntung exchanged four registers, changed the arrangement of the manuals and added couplers.

In 1758, his son, added a small swell division with three voices, the action

Action may refer to:

* Action (narrative), a literary mode

* Action fiction, a type of genre fiction

* Action game, a genre of video game

Film

* Action film, a genre of film

* ''Action'' (1921 film), a film by John Ford

* ''Action'' (1980 fil ...

being controllable from the breast division manual.

By the beginning of the 19th century the organ had 3 manuals and a pedalboard, 57 registers and 4,684 pipes.

In 1851, however, a completely new organ was installed – built by Johann Friedrich Schulze

Johann Friedrich Schulze (27 January 1793 – 9 January 1858) was a German organ builder, from a family of organ builders. The company built major organs in Northern Germany and England.

Career

Schulze was born in Milbitz, the only child of J ...

, in the spirit of the time, with four manuals, a pedalboard, and 80 voices, behind the historic organ case by Benedikt Dreyer, which was restored and added to by Carl Julius Milde

Carl Julius Milde (16 February 1803, in Hamburg – 19 November 1875, in Lübeck) was a German painter, curator and art restorer.

Life

His father was a grocer whose business had been nearly ruined by the French Occupation. After a financial ...

.

This great organ was destroyed in 1942 and was replaced in 1968 by what was then the largest mechanical-action organ in the world. It was built by Kemper & Son.

It has 5 manuals and a pedalboard, 100 stops and 8,512 pipes; the longest are , the smallest is the size of a cigarette.

The tracker action operates electrically and has free combinations; the stop tableau is duplicated.

Danse macabre organ (choir organ)

requiem mass

A Requiem or Requiem Mass, also known as Mass for the dead ( la, Missa pro defunctis) or Mass of the dead ( la, Missa defunctorum), is a Mass of the Catholic Church offered for the repose of the soul or souls of one or more deceased persons, ...

es that were celebrated there. After the Church Reformation it was used for prayers and for Holy Communion services.

In 1549 and 1558 Jakob Scherer added to the organ among other things, a chair organ

A positive organ (also positiv organ, positif organ, portable organ, chair organ, or simply positive, positiv, positif, or chair) (from the Latin verb ''ponere'', "to place") is a small, usually one-manual, pipe organ that is built to be more ...

(), and in 1621 a chest division was added.

Friedrich Stellwagen also carried out extensive repairs from 1653 to 1655. Thereafter, only minor changes were made.

For this reason, this organ, together with the Arp Schnitger

Arp Schnitger (2 July 164828 July 1719 (buried)) was an influential Northern German organ builder. Considered the most paramount manufacturer of his time, Schnitger built or rebuilt over 150 organs. He was primarily active in Northern Europe, es ...

organ in St. James' Church in Hamburg

Hamburg (, ; nds, label=Hamburg German, Low Saxon, Hamborg ), officially the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg (german: Freie und Hansestadt Hamburg; nds, label=Low Saxon, Friee un Hansestadt Hamborg),. is the List of cities in Germany by popul ...

and the Stellwagen Organ in in Lübeck, attracted the interest of organ experts in connection with the ''Orgelbewegung The Organ Reform Movement or ''Orgelbewegung'' (also called the Organ Revival Movement) was a mid-20th-century trend in pipe organ building, originating in Germany. The movement was most influential in the United States in the 1930s through 1970s, ...

''.

The of the organ was changed back to what it had been in the 17th century.

But, like the main organ, this organ was also destroyed in 1942.

In 1955 the organ builders Kemper & Son restored the ''Danse Macabre'' organ in accordance with its 1937 dimensions, but now in the northern part of the ambulatory, in the direction of the raised choir.

Its original place is now occupied by the astronomical clock.

This post-War organ, which was very prone to malfunction, was replaced in 1986 by a new ''Danse Macabre'' organ, built by Führer Co. in Wilhelmshaven and positioned in the same place as its predecessor.

It has a mechanical tracker action

Tracker action is a term used in reference to pipe organs and steam calliopes to indicate a mechanical linkage between keys or pedals pressed by the organist and the valve that allows air to flow into pipe(s) of the corresponding note. This is ...

, with four manuals and a pedalboard, 56 stops and approximately 5,000 pipes.

This organ is particularly suited for accompanying prayers and services, as well as an instrument for older organ music up to Bach.

As a special tradition at St Mary's, on New Year's Eve

In the Gregorian calendar, New Year's Eve, also known as Old Year's Day or Saint Sylvester's Day in many countries, is the evening or the entire day of the last day of the year, on 31 December. The last day of the year is commonly referred to ...

the chorale

Chorale is the name of several related musical forms originating in the music genre of the Lutheran chorale:

* Hymn tune of a Lutheran hymn (e.g. the melody of "Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme"), or a tune in a similar format (e.g. one of the th ...

''Now Thank We All Our God

"Now thank we all our God" is a popular Christian hymn. Catherine Winkworth translated it from the German "", written by the Lutheran pastor Martin Rinkart. Its hymn tune, Zahn No. 5142, was published by Johann Crüger in the 1647 edition ...

'' is accompanied by both organs, kettledrum

Timpani (; ) or kettledrums (also informally called timps) are musical instruments in the percussion family. A type of drum categorised as a hemispherical drum, they consist of a membrane called a head stretched over a large bowl traditionally ...

s and a brass band.

Other instruments

There used to be an organ on therood screen

The rood screen (also choir screen, chancel screen, or jubé) is a common feature in late medieval church architecture. It is typically an ornate partition between the chancel and nave, of more or less open tracery constructed of wood, stone, o ...

, as a basso continuo

Basso continuo parts, almost universal in the Baroque era (1600–1750), provided the harmonic structure of the music by supplying a bassline and a chord progression. The phrase is often shortened to continuo, and the instrumentalists playing the ...

instrument for the choir that was located there – the church's third organ.

In 1854 the breast division that was removed from the Great Organ (built in 1560–1561 by Jacob Scherer) when it was converted was installed here.

This "rood screen organ" had one manual and seven stops and was replaced in 1900 by a two-manual pneumatic

Pneumatics (from Greek ‘wind, breath’) is a branch of engineering that makes use of gas or pressurized air.

Pneumatic systems used in industry are commonly powered by compressed air or compressed inert gases. A centrally located and ...

organ made by the organ builder Emanuel Kemper, the old organ box being retained. This organ, too, was destroyed in 1942.

In the Chapel of Indulgences () there is a chamber organ

Carol Williams performing at the United States Military Academy West Point Cadet Chapel.">West_Point_Cadet_Chapel.html" ;"title="United States Military Academy West Point Cadet Chapel">United States Military Academy West Point Cadet Chapel.

...

originally from East Prussia

East Prussia ; german: Ostpreißen, label= Low Prussian; pl, Prusy Wschodnie; lt, Rytų Prūsija was a province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1773 to 1829 and again from 1878 (with the Kingdom itself being part of the German Empire from 187 ...

. It has been in the chapel since 1948.

It has a single manual and eight voices, with separate control of bass and descant parts.

It was built by Johannes Schwarz in 1723 and from 1724 was the organ of the (Castle Chapel) of Dönhofstädt near Rastenburg (now Kętrzyn

Kętrzyn (, until 1946 ''Rastembork''; german: link=yes, Rastenburg ) is a town in northeastern Poland with 27,478 inhabitants (2019). Situated in the Warmian-Masurian Voivodeship (since 1999), Kętrzyn was previously in Olsztyn Voivodeship (197 ...

, Poland).

From there it was acquired by Lübeck organ builder Karl Kemper in 1933.

For a few years it was in the choir of St. Catherine's Church, Lübeck

St. Catherine Church () in Lübeck is a Brick Gothic church which belonged to a Franciscan monastery in the name of Saint Catherine of Alexandria, seized along other property from the Catholic Church by a city ordinance (Der keyserliken Lübeck ch ...

.

Then, Walter Kraft brought it, as a temporary measure, to the Chapel of Indulgences at St. Mary's, this being the first part of the church to be ready for church services after the War.

Today this organ provides the accompaniment for prayers as well as the Sunday services that are held in the Chapel of Indulgences from January to March.

Organists

Two 17th-century organists, especially, shaped the development of the musical tradition of St. Mary's:Franz Tunder

Franz Tunder (1614 – November 5, 1667) was a German composer and organist of the early to middle Baroque era. He was an important link between the early German Baroque style which was based on Venetian models, and the later Baroque style ...

from 1642 until his death in 1667, and his successor and son-in-law, Dieterich Buxtehude

Dieterich Buxtehude (; ; born Diderik Hansen Buxtehude; c. 1637 – 9 May 1707) was a Danish organist and composer of the Baroque period, whose works are typical of the North German organ school. As a composer who worked in various vocal a ...

, from 1668 to 1707.

Both were defining representatives of the north German organ school The 17th century organ composers of Germany can be divided into two primary schools: the north German school and the south German school (sometimes a third school, central German, is added). The stylistic differences were dictated not only by teach ...

and were prominent both as organists and as composers.

In 1705 Johann Sebastian Bach

Johann Sebastian Bach (28 July 1750) was a German composer and musician of the late Baroque period. He is known for his orchestral music such as the '' Brandenburg Concertos''; instrumental compositions such as the Cello Suites; keyboard wo ...

came to Lübeck to observe and learn from Buxtehude, and Georg Friedrich Händel

George Frideric (or Frederick) Handel (; baptised , ; 23 February 1685 – 14 April 1759) was a German-British Baroque composer well known for his operas, oratorios, anthems, concerti grossi, and organ concertos. Handel received his training i ...

and Johann Mattheson

Johann Mattheson (28 September 1681 – 17 April 1764) was a German composer, singer, writer, lexicographer, diplomat and music theorist.

Early life and career

The son of a prosperous tax collector, Mattheson received a broad liberal education ...

had already been guests of Buxtehude in 1703.

Since then, the position of organist at St. Mary's Church has been one of the most prestigious in Germany.

With their evening concerts, Tunder and Buxtehude were the first to introduce church concerts independent of religious services. Buxtehude developed a fixed format, with a series of five concerts on the two last Sundays of the Trinity period (i.e. the last two Sundays before Advent) and the second, third, and fourth Sunday in Advent

Advent is a Christian season of preparation for the Nativity of Christ at Christmas. It is the beginning of the liturgical year in Western Christianity.

The name was adopted from Latin "coming; arrival", translating Greek '' parousia''. ...

.

This very successful series of concerts was continued by Buxtehude's successors, Johann Christian Schieferdecker Johann Christian Schieferdecker (or Schiefferdecker; 16791732) was a German Baroque composer.

Schieferdecker was born in Teuchern. He became harpsichord-player at the Hamburg Opera, then succeeded Dietrich Buxtehude as organist of the Marienkirc ...

(1679–1732), (1696–1757), his son (1720–1781) and Johann Wilhelm Cornelius von Königslöw.

For the evening concerts they each composed a series of Biblical oratorio

An oratorio () is a large musical composition for orchestra, choir, and soloists. Like most operas, an oratorio includes the use of a choir, soloists, an instrumental ensemble, various distinguishable characters, and arias. However, opera is ...

s, including 'Israel's Idol Worship in the Desert''(1758), ''Absalon'' (1761) and ''Goliath'' (1762) by Adolf Kunzen and 'The Finding of Baby Moses''and 'The Saviour of the World is born''(1788), 'Death, Resurrection and Judgment''(1790), and '' 'David's Lament on Mount Hermon (Psalm 42)''' (1793) by Königslöw.

Around 1810 this tradition ended for a time. Attitudes towards music and the Church had changed, and external circumstances (the occupation by Napoleon's troops and the resulting financial straits) made such expensive concerts impossible.

In the early 20th century it was the organist Walter Kraft

Walter Kraft ( Cologne, 9 June 1905 – Amsterdam, 9 May 1977) was a German organist and composer, best known for his remarkably long tenure (1929–72) at the Marienkirche, Lübeck.

Biography

Kraft studied piano and organ in Hamburg with Hann ...

(1905–1977) who tried to revive the tradition of the evening concerts, starting with an evening of Bach's organ music, followed by an annual programme of combined choral and organ works. In 1954 Kraft created the (''Lübeck Danse Macabre'') as a new type of evening concert.

The tradition of evening concerts continues today under the current organist (since 2009), Johannes Unger.

List of organists

* 1516–1518 (?) Barthold Hering * –1572: David Ebel * 1597–1611: Heinrich Marcus * 1612–1616: * 1616–1640:Peter Hasse

Peter (Petrus) Hasse (ca. 1585 – June 1640) was a German organist and composer, and member of the prominent musical Hasse family. The first written record of Hasse dates from his appointment as organist at the Marienkirche in Lübeck, a post ...

* 1642–1667: Franz Tunder

Franz Tunder (1614 – November 5, 1667) was a German composer and organist of the early to middle Baroque era. He was an important link between the early German Baroque style which was based on Venetian models, and the later Baroque style ...

* 1668–1707: Dietrich Buxtehude