Spring Of Nations on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the Springtime of the Peoples or the Springtime of Nations, were a series of

The revolutions arose from such a wide variety of causes that it is difficult to view them as resulting from a coherent movement or set of social phenomena. Numerous changes had been taking place in European society throughout the first half of the 19th century. Both liberal reformers and radical politicians were reshaping national governments.

Technological change was revolutionizing the life of the working classes. A popular press extended political awareness, and new values and ideas such as popular liberalism,

The revolutions arose from such a wide variety of causes that it is difficult to view them as resulting from a coherent movement or set of social phenomena. Numerous changes had been taking place in European society throughout the first half of the 19th century. Both liberal reformers and radical politicians were reshaping national governments.

Technological change was revolutionizing the life of the working classes. A popular press extended political awareness, and new values and ideas such as popular liberalism,

The population in French rural areas had risen rapidly, causing many peasants to seek a living in the cities. Many in the

The population in French rural areas had risen rapidly, causing many peasants to seek a living in the cities. Many in the

The world was astonished in spring 1848 when revolutions appeared in so many places and seemed on the verge of success everywhere. Agitators who had been exiled by the old governments rushed home to seize the moment. In France, the

The world was astonished in spring 1848 when revolutions appeared in so many places and seemed on the verge of success everywhere. Agitators who had been exiled by the old governments rushed home to seize the moment. In France, the

Although few noticed at the time, the first major outbreak came in Palermo, Sicily, starting in January 1848. There had been several previous revolts against Bourbon rule; this one produced an independent state that lasted only 16 months before the Bourbons came back. During those months, the constitution was quite advanced for its time in liberal democratic terms, as was the proposal of an Italian confederation of states. The revolt's failure was reversed 12 years later as the Bourbon

Although few noticed at the time, the first major outbreak came in Palermo, Sicily, starting in January 1848. There had been several previous revolts against Bourbon rule; this one produced an independent state that lasted only 16 months before the Bourbons came back. During those months, the constitution was quite advanced for its time in liberal democratic terms, as was the proposal of an Italian confederation of states. The revolt's failure was reversed 12 years later as the Bourbon

The "March Revolution" in the German states took place in the south and the west of Germany, with large popular assemblies and mass demonstrations. Led by well-educated students and intellectuals, they demanded German national unity,

The "March Revolution" in the German states took place in the south and the west of Germany, with large popular assemblies and mass demonstrations. Led by well-educated students and intellectuals, they demanded German national unity,

Denmark had been governed by a system of absolute monarchy (

Denmark had been governed by a system of absolute monarchy (

From March 1848 through July 1849, the Habsburg Austrian Empire was threatened by revolutionary movements, which often had a nationalist character. The empire, ruled from Vienna, included Germans, Austrians, Hungarians, Slovenes, Poles, Czechs,

From March 1848 through July 1849, the Habsburg Austrian Empire was threatened by revolutionary movements, which often had a nationalist character. The empire, ruled from Vienna, included Germans, Austrians, Hungarians, Slovenes, Poles, Czechs,

The Hungarian revolution of 1848 was the longest in Europe, crushed in August 1849 by Austrian and Russian armies. Nevertheless, it had a major effect in freeing the serfs. It started on 15 March 1848, when Hungarian patriots organized mass demonstrations in Pest and

The Hungarian revolution of 1848 was the longest in Europe, crushed in August 1849 by Austrian and Russian armies. Nevertheless, it had a major effect in freeing the serfs. It started on 15 March 1848, when Hungarian patriots organized mass demonstrations in Pest and

A Romanian liberal and Romantic nationalist uprising began in June in the principality of

A Romanian liberal and Romantic nationalist uprising began in June in the principality of

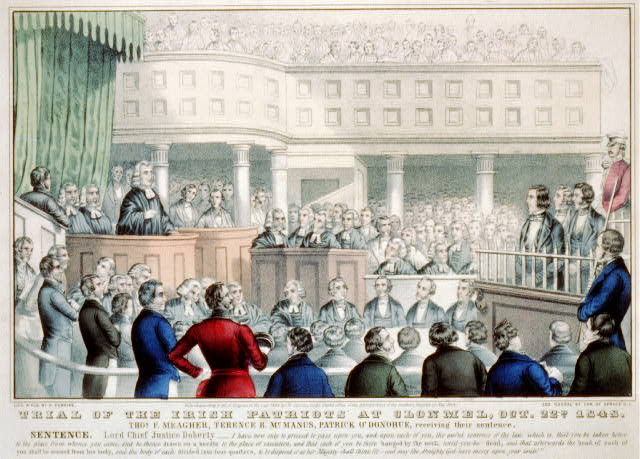

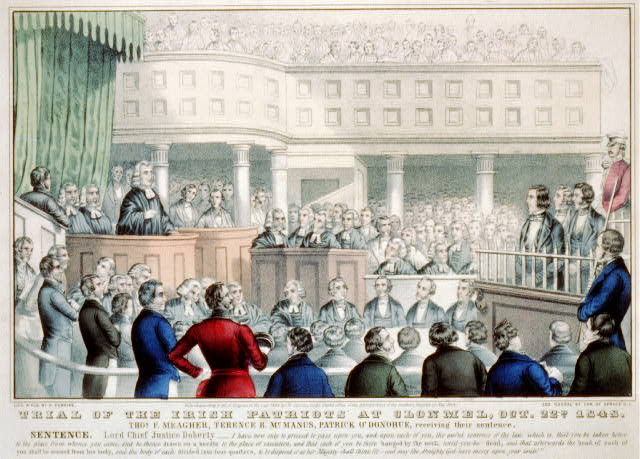

In Ireland a current of

In Ireland a current of

In Britain, while the middle classes had been pacified by their inclusion in the extension of the franchise in the

In Britain, while the middle classes had been pacified by their inclusion in the extension of the franchise in the

In the post-revolutionary decade after 1848, little had visibly changed, and many historians considered the revolutions a failure, given the seeming lack of permanent structural changes. More recently,

In the post-revolutionary decade after 1848, little had visibly changed, and many historians considered the revolutions a failure, given the seeming lack of permanent structural changes. More recently,

File:General Blenker.jpg, Louis Blenker ermanyFile:Alexander Schimmelfennig.jpg,

online from Ohio State U.

* Dowe, Dieter, ed. ''Europe in 1848: Revolution and Reform'' (Berghahn Books, 2000) * Evans, R. J. W., and Hartmut Pogge von Strandmann, eds. ''The Revolutions in Europe, 1848–1849: From Reform to Reaction'' (2000), 10 essays by scholar

excerpt and text search

* Pouthas, Charles. "The Revolutions of 1848" in J. P. T. Bury, ed. ''New Cambridge Modern History: The Zenith of European Power 1830–70'' (1960) pp. 389–41

online excerpts

* Langer, William. ''The Revolutions of 1848'' (Harper, 1971), standard overview * ''Political and social upheaval, 1832-1852'' (1969), standard overvie

online

* Namier, Lewis. ''1848: The Revolution of the Intellectuals'' (Doubleday Anchor Books, 1964), first published by the British Academy in 1944. * Rapport, Mike (2009), ''1848: Year of Revolution''

online review

a standard survey * Robertson, Priscilla (1952), ''Revolutions of 1848: A Social History'' (), despite the subtitle this is a traditional political narrative * Sperber, Jonathan. ''The European revolutions, 1848–1851'' (1994

online edition

* Stearns, Peter N. ''The Revolutions of 1848'' (1974)

online edition

* Weyland, Kurt. "The Diffusion of Revolution: '1848' in Europe and Latin America", ''International Organization'' Vol. 63, No. 3 (Summer, 2009) pp. 391–423 .

in JSTOR

* Loubère, Leo. "The Emergence of the Extreme Left in Lower Languedoc, 1848–1851: Social and Economic Factors in Politics," ''American Historical Review'' (1968), v. 73#4 1019–5

in JSTOR

* Merriman, John M. ''The Agony of the Republic: The Repression of the Left in Revolutionary France, 1848-1851'' (Yale UP, 1978).

online

* Hewitson, Mark. "'The Old Forms are Breaking Up, ... Our New Germany is Rebuilding Itself': Constitutionalism, Nationalism and the Creation of a German Polity during the Revolutions of 1848–49," ''English Historical Review,'' Oct 2010, Vol. 125 Issue 516, pp. 1173–121

online

* Macartney, C. A. "1848 in the Habsburg Monarchy," ''European Studies Review,'' 1977, Vol. 7 Issue 3, pp. 285–30

online

* O'Boyle Lenore. "The Democratic Left in Germany, 1848," ''Journal of Modern History'' Vol. 33, No. 4 (Dec. 1961), pp. 374–8

in JSTOR

* Robertson, Priscilla. ''Revolutions of 1848: A Social History'' (1952), pp 105–85 on Germany, pp. 187–307 on Austria * Sked, Alan. ''The Survival of the Habsburg Empire: Radetzky, the Imperial Army and the Class War, 1848'' (1979) * Vick, Brian. ''Defining Germany The 1848 Frankfurt Parliamentarians and National Identity'' (Harvard University Press, 2002) .

in JSTOR

* Ginsborg, Paul. ''Daniele Manin and the Venetian Revolution of 1848–49'' (1979) * Robertson, Priscilla (1952). ''Revolutions of 1848: A Social History'' (1952) pp. 309–401

in JSTOR

* Jones, Peter (1981), ''The 1848 Revolutions (Seminar Studies in History)'' () * Mattheisen, Donald J. "History as Current Events: Recent Works on the German Revolution of 1848," ''American Historical Review,'' Dec 1983, Vol. 88 Issue 5, pp. 1219–3

in JSTOR

* Rothfels, Hans. "1848 – One Hundred Years After," ''Journal of Modern History,'' Dec 1948, Vol. 20 Issue 4, pp. 291–31

in JSTOR

Maps of Europe showing the Revolutions of 1848–1849 at omniatlas.com

{{Authority control

political upheaval

In political science, a revolution (Latin: ''revolutio'', "a turn around") is a fundamental and relatively sudden change in political power and political organization which occurs when the population revolts against the government, typically due ...

s throughout Europe starting in 1848. It remains the most widespread revolutionary wave

A revolutionary wave or revolutionary decade is one series of revolutions occurring in various locations within a similar time-span. In many cases, past revolutions and revolutionary waves have inspired current ones, or an initial revolution has ...

in European history

The history of Europe is traditionally divided into four time periods: prehistoric Europe (prior to about 800 BC), classical antiquity (800 BC to AD 500), the Middle Ages (AD 500 to AD 1500), and the modern era (since AD 1500).

The first early ...

to date.

The revolutions were essentially democratic and liberal in nature, with the aim of removing the old monarchical

A monarchy is a form of government in which a person, the monarch, is head of state for life or until abdication. The political legitimacy and authority of the monarch may vary from restricted and largely symbolic (constitutional monarchy) ...

structures and creating independent nation-state

A nation state is a political unit where the state and nation are congruent. It is a more precise concept than "country", since a country does not need to have a predominant ethnic group.

A nation, in the sense of a common ethnicity, may in ...

s, as envisioned by romantic nationalism

Romantic nationalism (also national romanticism, organic nationalism, identity nationalism) is the form of nationalism in which the state claims its political legitimacy as an organic consequence of the unity of those it governs. This includes ...

. The revolutions spread across Europe after an initial revolution began in France in February. Over 50 countries were affected, but with no significant coordination or cooperation among their respective revolutionaries. Some of the major contributing factors were widespread dissatisfaction with political leadership, demands for more participation in government and democracy, demands for freedom of the press

Freedom of the press or freedom of the media is the fundamental principle that communication and expression through various media, including printed and electronic media, especially published materials, should be considered a right to be exerc ...

, other demands made by the working class

The working class (or labouring class) comprises those engaged in manual-labour occupations or industrial work, who are remunerated via waged or salaried contracts. Working-class occupations (see also " Designation of workers by collar colou ...

for economic rights, the upsurge of nationalism

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a in-group and out-group, group of peo ...

, the regrouping of established government forces, and the European Potato Failure

The European Potato Failure was a food crisis caused by potato blight that struck Northern and Western Europe in the mid-1840s. The time is also known as the Hungry Forties. While the crisis produced excess mortality and suffering across the aff ...

, which triggered mass starvation, migration, and civil unrest.

The uprisings were led by temporary coalitions of reformers, the middle classes, the upper classes (the bourgeoisie

The bourgeoisie ( , ) is a social class, equivalent to the middle or upper middle class. They are distinguished from, and traditionally contrasted with, the proletariat by their affluence, and their great cultural and financial capital. Th ...

) and workers; however, the coalitions did not hold together for long. Many of the revolutions were quickly suppressed, as tens of thousands of people were killed, and many more were forced into exile. Significant lasting reforms included the abolition of serfdom

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism, and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery, which develop ...

in Austria and Hungary, the end of absolute monarchy

Absolute monarchy (or Absolutism as a doctrine) is a form of monarchy in which the monarch rules in their own right or power. In an absolute monarchy, the king or queen is by no means limited and has absolute power, though a limited constituti ...

in Denmark, and the introduction of representative democracy

Representative democracy, also known as indirect democracy, is a type of democracy where elected people represent a group of people, in contrast to direct democracy. Nearly all modern Western-style democracies function as some type of represe ...

in the Netherlands. The revolutions were most important in France, the Netherlands, Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

, the Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire (german: link=no, Kaiserthum Oesterreich, modern spelling , ) was a Central- Eastern European multinational great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the realms of the Habsburgs. During its existence, ...

, and the states of the German Confederation

The German Confederation (german: Deutscher Bund, ) was an association of 39 predominantly German-speaking sovereign states in Central Europe. It was created by the Congress of Vienna in 1815 as a replacement of the former Holy Roman Empire, w ...

that would make up the German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Although the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and ...

didn't see any notable actions at home, in British Ceylon

British Ceylon ( si, බ්රිතාන්ය ලංකාව, Britānya Laṃkāva; ta, பிரித்தானிய இலங்கை, Biritthāṉiya Ilaṅkai) was the British Crown colony of present-day Sri Lanka between ...

there was a parallel

but failed uprising against British rule known as the Matale Rebellion.

Origins

The revolutions arose from such a wide variety of causes that it is difficult to view them as resulting from a coherent movement or set of social phenomena. Numerous changes had been taking place in European society throughout the first half of the 19th century. Both liberal reformers and radical politicians were reshaping national governments.

Technological change was revolutionizing the life of the working classes. A popular press extended political awareness, and new values and ideas such as popular liberalism,

The revolutions arose from such a wide variety of causes that it is difficult to view them as resulting from a coherent movement or set of social phenomena. Numerous changes had been taking place in European society throughout the first half of the 19th century. Both liberal reformers and radical politicians were reshaping national governments.

Technological change was revolutionizing the life of the working classes. A popular press extended political awareness, and new values and ideas such as popular liberalism, nationalism

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a in-group and out-group, group of peo ...

and socialism

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes th ...

began to emerge. Some historians emphasize the serious crop failures, particularly those of 1846, that produced hardship among peasants and the working urban poor.

Large swaths of the nobility

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy. It is normally ranked immediately below royalty. Nobility has often been an estate of the realm with many exclusive functions and characteristics. The character ...

were discontented with royal absolutism

Absolute monarchy (or Absolutism as a doctrine) is a form of monarchy in which the monarch rules in their own right or power. In an absolute monarchy, the king or queen is by no means limited and has absolute power, though a limited constitut ...

or near-absolutism. In 1846, there had been an uprising

Rebellion, uprising, or insurrection is a refusal of obedience or order. It refers to the open resistance against the orders of an established authority.

A rebellion originates from a sentiment of indignation and disapproval of a situation and ...

of Polish nobility in Austrian Galicia

Galicia may refer to:

Geographic regions

* Galicia (Spain), a region and autonomous community of northwestern Spain

** Gallaecia, a Roman province

** The post-Roman Kingdom of the Suebi, also called the Kingdom of Gallaecia

** The medieval King ...

, which was only countered when peasants, in turn, rose up against the nobles. Additionally, an uprising

Rebellion, uprising, or insurrection is a refusal of obedience or order. It refers to the open resistance against the orders of an established authority.

A rebellion originates from a sentiment of indignation and disapproval of a situation and ...

by democratic forces against Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an e ...

, planned but not actually carried out, occurred in Greater Poland

Greater Poland, often known by its Polish name Wielkopolska (; german: Großpolen, sv, Storpolen, la, Polonia Maior), is a historical region of west-central Poland. Its chief and largest city is Poznań followed by Kalisz, the oldest cit ...

.

The middle and working classes thus shared a desire for reform, and agreed on many of the specific aims. Their participation in the revolutions, however, differed. While much of the impetus came from the middle classes, the physical backbone of the movement came from the lower classes. The revolts first erupted in the cities.

Urban workers

bourgeoisie

The bourgeoisie ( , ) is a social class, equivalent to the middle or upper middle class. They are distinguished from, and traditionally contrasted with, the proletariat by their affluence, and their great cultural and financial capital. Th ...

feared and distanced themselves from the working poor

The working poor are working people whose incomes fall below a given poverty line due to low-income jobs and low familial household income. These are people who spend at least 27 weeks in a year working or looking for employment, but remain und ...

. Many unskilled laborers toiled from 12 to 15 hours per day when they had work, living in squalid, disease-ridden slums. Traditional artisans felt the pressure of industrialization

Industrialisation ( alternatively spelled industrialization) is the period of social and economic change that transforms a human group from an agrarian society into an industrial society. This involves an extensive re-organisation of an econo ...

, having lost their guild

A guild ( ) is an association of artisans and merchants who oversee the practice of their craft/trade in a particular area. The earliest types of guild formed as organizations of tradesmen belonging to a professional association. They sometim ...

s.

The liberalization of trade laws and the growth of factories had increased the gulf between master tradesmen, and journeymen and apprentices, whose numbers increased disproportionately by 93% from 1815 to 1848 in Germany. Significant proletarian unrest had occurred in Lyon

Lyon,, ; Occitan: ''Lion'', hist. ''Lionés'' also spelled in English as Lyons, is the third-largest city and second-largest metropolitan area of France. It is located at the confluence of the rivers Rhône and Saône, to the northwest of ...

in 1831 and 1834, and Prague

Prague ( ; cs, Praha ; german: Prag, ; la, Praga) is the capital and largest city in the Czech Republic, and the historical capital of Bohemia. On the Vltava river, Prague is home to about 1.3 million people. The city has a temperate ...

in 1844. Jonathan Sperber has suggested that in the period after 1825, poorer urban workers (particularly day laborers, factory workers and artisans) saw their purchasing power decline relatively steeply: urban meat consumption in Belgium, France and Germany stagnated or declined after 1830, despite growing populations. The economic Panic of 1847 increased urban unemployment: 10,000 Viennese factory workers lost jobs, and 128 Hamburg firms went bankrupt over the course of 1847. With the exception of the Netherlands, there was a strong correlation among the countries that were most deeply affected by the industrial shock of 1847 and those that underwent a revolution in 1848.

The situation in the German states was similar. Parts of Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an e ...

were beginning to industrialize. During the decade of the 1840s, mechanized production in the textile industry brought about inexpensive clothing that undercut the handmade products of German tailors. Reforms ameliorated the most unpopular features of rural feudalism

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was the combination of the legal, economic, military, cultural and political customs that flourished in medieval Europe between the 9th and 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of structu ...

, but industrial workers remained dissatisfied with these reforms and pressed for greater change.

Urban workers had no choice but to spend half of their income on food, which consisted mostly of bread and potatoes. As a result of harvest failures, food prices

Food prices refer to the average price level for food across countries, regions and on a global scale. Food prices have an impact on producers and consumers of food.

Price levels depend on the food production process, including food marketing ...

soared and the demand for manufactured goods decreased, causing an increase in unemployment. During the revolution, to address the problem of unemployment, workshops were organized for men interested in construction work. Officials also set up workshops for women when they felt they were excluded. Artisans and unemployed workers destroyed industrial machines when they threatened to give employers more power over them.

Rural areas

Rural population growth had led to food shortages,land

Land, also known as dry land, ground, or earth, is the solid terrestrial surface of the planet Earth that is not submerged by the ocean or other bodies of water. It makes up 29% of Earth's surface and includes the continents and various isla ...

pressure, and migration, both within and from Europe, especially to the Americas. Peasant discontent in the 1840s grew in intensity: peasant occupations of lost communal land increased in many areas: those convicted of wood theft in the Rhenish Palatinate increased from 100,000 in 1829–30 to 185,000 in 1846–47. In the years 1845 and 1846, a potato blight

''Phytophthora infestans'' is an oomycete or water mold, a fungus-like microorganism that causes the serious potato and tomato disease known as late blight or potato blight. Early blight, caused by ''Alternaria solani'', is also often called "po ...

caused a subsistence crisis in Northern Europe, and encouraged the raiding of manorial potato stocks in Silesia in 1847. The effects of the blight were most severely manifested in the Great Irish Famine

The Great Famine ( ga, an Gorta Mór ), also known within Ireland as the Great Hunger or simply the Famine and outside Ireland as the Irish Potato Famine, was a period of starvation and disease in Ireland from 1845 to 1852 that constituted a h ...

,Helen Litton, ''The Irish Famine: An Illustrated History'', Wolfhound Press, 1995, but also caused famine-like conditions in the Scottish Highlands

The Highlands ( sco, the Hielands; gd, a’ Ghàidhealtachd , 'the place of the Gaels') is a historical region of Scotland. Culturally, the Highlands and the Lowlands diverged from the Late Middle Ages into the modern period, when Lowland S ...

and throughout continental Europe

Continental Europe or mainland Europe is the contiguous continent of Europe, excluding its surrounding islands. It can also be referred to ambiguously as the European continent, – which can conversely mean the whole of Europe – and, by ...

. Harvests of rye in the Rhineland were 20% of previous levels, while the Czech potato harvest was reduced by half. These reduced harvests were accompanied by a steep rise in prices (the cost of wheat more than doubled in France and Habsburg Italy). There were 400 French food riots during 1846 to 1847, while German socio-economic protests increased from 28 during 1830 to 1839, to 103 during 1840 to 1847. Central to long-term peasant grievances were the loss of communal lands, forest restrictions (such as the French Forest Code of 1827), and remaining feudal structures, notably the robot (labor obligations) that existed among the serfs and oppressed peasantry of the Habsburg lands.

Aristocratic

Aristocracy (, ) is a form of government that places strength in the hands of a small, privileged ruling class, the aristocrats. The term derives from the el, αριστοκρατία (), meaning 'rule of the best'.

At the time of the word' ...

wealth (and corresponding power) was synonymous with the ownership of farm lands and effective control over the peasant

A peasant is a pre-industrial agricultural laborer or a farmer with limited land-ownership, especially one living in the Middle Ages under feudalism and paying rent, tax, fees, or services to a landlord. In Europe, three classes of peasa ...

s. Peasant grievances exploded during the revolutionary year of 1848, yet were often disconnected from urban revolutionary movements: the revolutionary Sándor Petőfi

Sándor Petőfi ( []; né Petrovics; sk, Alexander Petrovič; sr, Александар Петровић; 1 January 1823 – most likely 31 July 1849) was a Hungarian poet of Serbian origin and liberal revolutionary. He is considered Hungary' ...

's popular nationalist rhetoric in Budapest did not translate into any success with the Magyar peasantry, while the Viennese democrat Hans Kudlich reported that his efforts to galvanize the Austrian peasantry had "disappeared in the great sea of indifference and phlegm".

Role of ideas

Despite forceful and often violent efforts of established and reactionary powers to keep them down, disruptive ideas gained popularity:democracy

Democracy (From grc, δημοκρατία, dēmokratía, ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which the people have the authority to deliberate and decide legislation (" direct democracy"), or to choose g ...

, liberalism

Liberalism is a Political philosophy, political and moral philosophy based on the Individual rights, rights of the individual, liberty, consent of the governed, political equality and equality before the law."political rationalism, hostilit ...

, radicalism, nationalism

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a in-group and out-group, group of peo ...

, and socialism

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes th ...

. They demanded a constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these pr ...

, universal manhood suffrage

Universal manhood suffrage is a form of voting rights in which all adult male citizens within a political system are allowed to vote, regardless of income, property, religion, race, or any other qualification. It is sometimes summarized by the slo ...

, press freedom

Freedom of the press or freedom of the media is the fundamental principle that communication and expression through various media, including printed and electronic media, especially published materials, should be considered a right to be exerc ...

, freedom of expression

Freedom of speech is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or a community to articulate their opinions and ideas without fear of retaliation, censorship, or legal sanction. The right to freedom of expression has been recog ...

and other democratic rights, the establishment of civilian militia, liberation of peasants, liberalization of the economy, abolition of tariff barriers and the abolition of monarchical power structures in favour of the establishment of republican states, or at least the restriction of the prince power in the form of constitutional monarchies.

In the language of the 1840s, 'democracy' meant replacing an electorate of property-owners with universal male suffrage

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise, is the right to vote in public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally in English, the right to v ...

. 'Liberalism' fundamentally meant consent of the governed

In political philosophy, the phrase consent of the governed refers to the idea that a government's legitimacy and moral right to use state power is justified and lawful only when consented to by the people or society over which that political pow ...

, restriction of church and state

State may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Literature

* ''State Magazine'', a monthly magazine published by the U.S. Department of State

* ''The State'' (newspaper), a daily newspaper in Columbia, South Carolina, United States

* ''Our S ...

power, republican government, freedom of the press

Freedom of the press or freedom of the media is the fundamental principle that communication and expression through various media, including printed and electronic media, especially published materials, should be considered a right to be exerc ...

and the individual. The 1840s had seen the emergence of radical liberal publications such as ''Rheinische Zeitung'' (1842); ''Le National'' and ''La Réforme'' (1843) in France; Ignaz Kuranda

Ignaz Kuranda (1 May 1812 in Prague – 3 April 1884 in Vienna) was an Austrian deputy and political writer of Bohemian origin.

Establishes "Die Grenzboten"

His grandfather and father were dealers in second-hand books. In 1834 he went t ...

's ''Grenzboten'' (1841) in Austria; Lajos Kossuth

Lajos Kossuth de Udvard et Kossuthfalva (, hu, udvardi és kossuthfalvi Kossuth Lajos, sk, Ľudovít Košút, anglicised as Louis Kossuth; 19 September 1802 – 20 March 1894) was a Hungarian nobleman, lawyer, journalist, polit ...

's ''Pesti Hírlap'' (1841) in Hungary, as well as the increased popularity of the older ''Morgenbladet

''Morgenbladet'' is a Norwegian weekly, newspaper, covering politics, culture and science.

History

''Morgenbladet'' was founded in 1819 by the book printer Niels Wulfsberg. The paper is the country's first daily newspaper; however, Adresseavi ...

'' in Norway and the ''Aftonbladet

''Aftonbladet'' (, lit. "The evening paper") is a Swedish daily newspaper published in Stockholm, Sweden. It is one of the largest daily newspapers in the Nordic countries.

History and profile

The newspaper was founded by Lars Johan H ...

'' in Sweden.

'Nationalism' believed in uniting people bound by (some mix of) common language

Language is a structured system of communication. The structure of a language is its grammar and the free components are its vocabulary. Languages are the primary means by which humans communicate, and may be conveyed through a variety of ...

s, culture

Culture () is an umbrella term which encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, customs, capabilities, and habits of the individuals in these groups ...

, religion

Religion is usually defined as a social- cultural system of designated behaviors and practices, morals, beliefs, worldviews, texts, sanctified places, prophecies, ethics, or organizations, that generally relates humanity to supernatur ...

, shared history

History (derived ) is the systematic study and the documentation of the human activity. The time period of event before the invention of writing systems is considered prehistory. "History" is an umbrella term comprising past events as well ...

, and of course immediate geography

Geography (from Greek: , ''geographia''. Combination of Greek words ‘Geo’ (The Earth) and ‘Graphien’ (to describe), literally "earth description") is a field of science devoted to the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, an ...

; there were also irredentist

Irredentism is usually understood as a desire that one state annexes a territory of a neighboring state. This desire is motivated by ethnic reasons (because the population of the territory is ethnically similar to the population of the parent st ...

movements. Nationalism had developed a broader appeal during the pre-1848 period, as seen in the František Palacký's 1836 ''History of the Czech Nation'', which emphasised a national lineage of conflict with the Germans, or the popular patriotic ''Liederkranz'' (song-circles) that were held across Germany: patriotic and belligerent songs about Schleswig

The Duchy of Schleswig ( da, Hertugdømmet Slesvig; german: Herzogtum Schleswig; nds, Hartogdom Sleswig; frr, Härtochduum Slaswik) was a duchy in Southern Jutland () covering the area between about 60 km (35 miles) north and 70 km ...

had dominated the Würzburg

Würzburg (; Main-Franconian: ) is a city in the region of Franconia in the north of the German state of Bavaria. Würzburg is the administrative seat of the ''Regierungsbezirk'' Lower Franconia. It spans the banks of the Main River.

Würzburg ...

national song festival in 1845.

'Socialism' in the 1840s was a term without a consensus definition, meaning different things to different people, but was typically used within a context of more power for workers in a system based on worker ownership of the means of production

The means of production is a term which describes land, labor and capital that can be used to produce products (such as goods or services); however, the term can also refer to anything that is used to produce products. It can also be used as a ...

.

These concepts together - democracy, liberalism, nationalism and socialism, in the sense described above - came to be encapsulated in the political term radicalism.

Sequence of main trends

Every country had a distinctive timing, but the general pattern showed very sharp cycles as reform moved up then down.Spring 1848: Astonishing success

The world was astonished in spring 1848 when revolutions appeared in so many places and seemed on the verge of success everywhere. Agitators who had been exiled by the old governments rushed home to seize the moment. In France, the

The world was astonished in spring 1848 when revolutions appeared in so many places and seemed on the verge of success everywhere. Agitators who had been exiled by the old governments rushed home to seize the moment. In France, the monarchy

A monarchy is a form of government in which a person, the monarch, is head of state for life or until abdication. The political legitimacy and authority of the monarch may vary from restricted and largely symbolic ( constitutional monar ...

was once again overthrown and replaced by a republic. In a number of major German and Italian states, and in Austria, the old leaders were forced to grant liberal constitutions. The Italian and German states seemed to be rapidly forming unified nations. Austria gave Hungarians and Czechs liberal grants of autonomy and national status.

Summer 1848: Divisions among reformers

In France, bloody street battles exploded between the middle class reformers and the working class radicals. German reformers argued endlessly without finalizing their results.Kranzberg, ''1848: A Turning Point?'' (1962) p xii, xvii–xviii.Autumn 1848: Reactionaries organize for a counter-revolution

Caught off guard at first, the aristocracy and their allies plot a return to power.1849–1851: Overthrow of revolutionary regimes

The revolutions suffer a series of defeats in summer 1849. Reactionaries returned to power and many leaders of the revolution went into exile. Some social reforms proved permanent, and years later nationalists in Germany, Italy, and Hungary gained their objectives.Events by country or region

Italian states

Although few noticed at the time, the first major outbreak came in Palermo, Sicily, starting in January 1848. There had been several previous revolts against Bourbon rule; this one produced an independent state that lasted only 16 months before the Bourbons came back. During those months, the constitution was quite advanced for its time in liberal democratic terms, as was the proposal of an Italian confederation of states. The revolt's failure was reversed 12 years later as the Bourbon

Although few noticed at the time, the first major outbreak came in Palermo, Sicily, starting in January 1848. There had been several previous revolts against Bourbon rule; this one produced an independent state that lasted only 16 months before the Bourbons came back. During those months, the constitution was quite advanced for its time in liberal democratic terms, as was the proposal of an Italian confederation of states. The revolt's failure was reversed 12 years later as the Bourbon Kingdom of the Two Sicilies

The Kingdom of the Two Sicilies ( it, Regno delle Due Sicilie) was a kingdom in Southern Italy from 1816 to 1860. The kingdom was the largest sovereign state by population and size in Italy before Italian unification, comprising Sicily and al ...

collapsed in 1860–61 with the Risorgimento

The unification of Italy ( it, Unità d'Italia ), also known as the ''Risorgimento'' (, ; ), was the 19th-century political and social movement that resulted in the consolidation of different states of the Italian Peninsula into a single ...

.

France

The "February Revolution" in France was sparked by the suppression of the '' campagne des banquets.'' This revolution was driven by nationalist and republican ideals among the French general public, who believed the people should rule themselves. It ended theconstitutional monarchy

A constitutional monarchy, parliamentary monarchy, or democratic monarchy is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in decision making. Constitutional monarchies dif ...

of Louis-Philippe

Louis Philippe (6 October 1773 – 26 August 1850) was King of the French from 1830 to 1848, and the penultimate monarch of France.

As Louis Philippe, Duke of Chartres, he distinguished himself commanding troops during the Revolutionary Wa ...

, and led to the creation of the French Second Republic

The French Second Republic (french: Deuxième République Française or ), officially the French Republic (), was the republican government of France that existed between 1848 and 1852. It was established in February 1848, with the February Re ...

. After an interim period, Louis-Napoleon, the nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader wh ...

, was elected as president. In 1852, he staged a coup d'état and established himself as a dictatorial emperor of the Second French Empire

The Second French Empire (; officially the French Empire, ), was the 18-year Imperial Bonapartist regime of Napoleon III from 14 January 1852 to 27 October 1870, between the Second and the Third Republic of France.

Historians in the 1930s ...

.

Alexis de Tocqueville

Alexis Charles Henri Clérel, comte de Tocqueville (; 29 July 180516 April 1859), colloquially known as Tocqueville (), was a French aristocrat, diplomat, political scientist, political philosopher and historian. He is best known for his wo ...

remarked in his ''Recollections'' of the period, "society was cut in two: those who had nothing united in common envy, and those who had anything united in common terror."

German states

The "March Revolution" in the German states took place in the south and the west of Germany, with large popular assemblies and mass demonstrations. Led by well-educated students and intellectuals, they demanded German national unity,

The "March Revolution" in the German states took place in the south and the west of Germany, with large popular assemblies and mass demonstrations. Led by well-educated students and intellectuals, they demanded German national unity, freedom of the press

Freedom of the press or freedom of the media is the fundamental principle that communication and expression through various media, including printed and electronic media, especially published materials, should be considered a right to be exerc ...

, and freedom of assembly

Freedom of peaceful assembly, sometimes used interchangeably with the freedom of association, is the individual right or ability of people to come together and collectively express, promote, pursue, and defend their collective or shared ide ...

. The uprisings were poorly coordinated, but had in common a rejection of traditional, autocratic political structures in the 39 independent states of the German Confederation

The German Confederation (german: Deutscher Bund, ) was an association of 39 predominantly German-speaking sovereign states in Central Europe. It was created by the Congress of Vienna in 1815 as a replacement of the former Holy Roman Empire, w ...

. The middle-class and working-class components of the Revolution split, and in the end, the conservative aristocracy defeated it, forcing many liberal Forty-Eighters

The Forty-Eighters were Europeans who participated in or supported the Revolutions of 1848 that swept Europe. In the German Confederation, the Forty-Eighters favoured unification of Germany, a more democratic government, and guarantees of human ...

into exile.

Denmark

Denmark had been governed by a system of absolute monarchy (

Denmark had been governed by a system of absolute monarchy (King's Law

The King's Law () or ''Lex Regia'' () (also called the Danish Royal Law of 1665) was the absolutist constitution of Denmark and Norway from 1665 until 1849 and 1814, respectively. It established complete hereditary (agnatic-cognatic primogenitu ...

) since the 17th century. King Christian VIII

Christian VIII (18 September 1786 – 20 January 1848) was King of Denmark from 1839 to 1848 and, as Christian Frederick, King of Norway in 1814.

Christian Frederick was the eldest son of Hereditary Prince Frederick, a younger son of King Frederic ...

, a moderate reformer but still an absolutist, died in January 1848 during a period of rising opposition from farmers and liberals. The demands for constitutional monarchy, led by the National Liberals, ended with a popular march to Christiansborg on 21 March. The new king, Frederick VII, met the liberals' demands and installed a new Cabinet that included prominent leaders of the National Liberal Party.Weibull, Jörgen. "Scandinavia, History of." ''Encyclopædia Britannica

The (Latin for "British Encyclopædia") is a general knowledge English-language encyclopaedia. It is published by Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.; the company has existed since the 18th century, although it has changed ownership various t ...

'' 15th ed., Vol. 16, 324.

The national-liberal movement wanted to abolish absolutism, but retain a strongly centralized state. The king accepted a new constitution agreeing to share power with a bicameral parliament called the Rigsdag

Rigsdagen () was the name of the national legislature of Denmark from 1849 to 1953.

''Rigsdagen'' was Denmark's first parliament, and it was incorporated in the Constitution of 1849. It was a bicameral legislature, consisting of two houses, the ...

. It is said that the Danish king's first words after signing away his absolute power were, "that was nice, now I can sleep in the mornings". Although army officers were dissatisfied, they accepted the new arrangement which, in contrast to the rest of Europe, was not overturned by reactionaries. The liberal constitution did not extend to Schleswig

The Duchy of Schleswig ( da, Hertugdømmet Slesvig; german: Herzogtum Schleswig; nds, Hartogdom Sleswig; frr, Härtochduum Slaswik) was a duchy in Southern Jutland () covering the area between about 60 km (35 miles) north and 70 km ...

, leaving the Schleswig-Holstein Question

Schleswig-Holstein (; da, Slesvig-Holsten; nds, Sleswig-Holsteen; frr, Slaswik-Holstiinj) is the northernmost of the 16 states of Germany, comprising most of the historical duchy of Holstein and the southern part of the former Duchy of Schl ...

unanswered.

Schleswig

TheDuchy of Schleswig

The Duchy of Schleswig ( da, Hertugdømmet Slesvig; german: Herzogtum Schleswig; nds, Hartogdom Sleswig; frr, Härtochduum Slaswik) was a duchy in Southern Jutland () covering the area between about 60 km (35 miles) north and 70 km ...

, a region containing both Danes (a North Germanic population) and Germans (a West Germanic population), was a part of the Danish monarchy, but remained a duchy separate from the Kingdom of Denmark. Spurred by pan-German

Pan-Germanism (german: Pangermanismus or '), also occasionally known as Pan-Germanicism, is a pan-nationalist political idea. Pan-Germanists originally sought to unify all the German-speaking people – and possibly also Germanic-speaking ...

sentiment, the Germans of Schleswig took up arms in protest at a new policy announced by Denmark's National Liberal

National liberalism is a variant of liberalism, combining liberal policies and issues with elements of nationalism. Historically, national liberalism has also been used in the same meaning as conservative liberalism (right-liberalism).

A seri ...

government which would have fully integrated the duchy into Denmark.

The German population in Schleswig and Holstein revolted, inspired by the Protestant clergy. The German states sent in an army, but Danish victories in 1849 led to the Treaty of Berlin (1850) and the London Protocol (1852). They reaffirmed the sovereignty of the King of Denmark, while prohibiting union with Denmark. The violation of the latter provision led to renewed warfare in 1863 and the Prussian victory in 1864.

Habsburg Monarchy

From March 1848 through July 1849, the Habsburg Austrian Empire was threatened by revolutionary movements, which often had a nationalist character. The empire, ruled from Vienna, included Germans, Austrians, Hungarians, Slovenes, Poles, Czechs,

From March 1848 through July 1849, the Habsburg Austrian Empire was threatened by revolutionary movements, which often had a nationalist character. The empire, ruled from Vienna, included Germans, Austrians, Hungarians, Slovenes, Poles, Czechs, Croats

The Croats (; hr, Hrvati ) are a South Slavic ethnic group who share a common Croatian ancestry, culture, history and language. They are also a recognized minority in a number of neighboring countries, namely Austria, the Czech Republic ...

, Slovaks, Ukrainians/Ruthenians

Ruthenian and Ruthene are exonyms of Latin origin, formerly used in Eastern and Central Europe as common ethnonyms for East Slavs, particularly during the late medieval and early modern periods. The Latin term Rutheni was used in medieval sou ...

, Romanians, Serbs

The Serbs ( sr-Cyr, Срби, Srbi, ) are the most numerous South Slavs, South Slavic ethnic group native to the Balkans in Southeastern Europe, who share a common Serbian Cultural heritage, ancestry, Culture of Serbia, culture, History of ...

and Italians, all of whom attempted in the course of the revolution to achieve either autonomy, independence, or even hegemony over other nationalities. The nationalist picture was further complicated by the simultaneous events in the German states, which moved toward greater German national unity.

Hungary

The Hungarian revolution of 1848 was the longest in Europe, crushed in August 1849 by Austrian and Russian armies. Nevertheless, it had a major effect in freeing the serfs. It started on 15 March 1848, when Hungarian patriots organized mass demonstrations in Pest and

The Hungarian revolution of 1848 was the longest in Europe, crushed in August 1849 by Austrian and Russian armies. Nevertheless, it had a major effect in freeing the serfs. It started on 15 March 1848, when Hungarian patriots organized mass demonstrations in Pest and Buda

Buda (; german: Ofen, sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Budim, Будим, Czech and sk, Budín, tr, Budin) was the historic capital of the Kingdom of Hungary and since 1873 has been the western part of the Hungarian capital Budapest, on the ...

(today Budapest) which forced the imperial governor to accept their 12 points of demands, which included the demand for freedom of press, an independent Hungarian ministry residing in Buda-Pest and responsible to a popularly elected parliament, the formation of a National Guard, complete civil and religious equality, trial by jury, a national bank, a Hungarian army, the withdrawal of foreign (Austrian) troops from Hungary, the freeing of political prisoners, and the union with Transylvania. On that morning, the demands were read aloud along with poetry by Sándor Petőfi

Sándor Petőfi ( []; né Petrovics; sk, Alexander Petrovič; sr, Александар Петровић; 1 January 1823 – most likely 31 July 1849) was a Hungarian poet of Serbian origin and liberal revolutionary. He is considered Hungary' ...

with the simple lines of "We swear by the God of the Hungarians. We swear, we shall be slaves no more".Deak, Istvan. The Lawful Revolution. New York: Columbia University Press, 1979. Lajos Kossuth

Lajos Kossuth de Udvard et Kossuthfalva (, hu, udvardi és kossuthfalvi Kossuth Lajos, sk, Ľudovít Košút, anglicised as Louis Kossuth; 19 September 1802 – 20 March 1894) was a Hungarian nobleman, lawyer, journalist, polit ...

and some other liberal nobility that made up the Diet

Diet may refer to:

Food

* Diet (nutrition), the sum of the food consumed by an organism or group

* Dieting, the deliberate selection of food to control body weight or nutrient intake

** Diet food, foods that aid in creating a diet for weight loss ...

appealed to the Habsburg court with demands for representative government and civil liberties."The US and the 1848 Hungarian Revolution." The Hungarian Initiatives Foundation. Accessed 26 March 2015. http://www.hungaryfoundation.org/history/20140707_US_HUN_1848. These events resulted in Klemens von Metternich

Klemens Wenzel Nepomuk Lothar, Prince of Metternich-Winneburg zu Beilstein ; german: Klemens Wenzel Nepomuk Lothar Fürst von Metternich-Winneburg zu Beilstein (15 May 1773 – 11 June 1859), known as Klemens von Metternich or Prince Metternic ...

, the Austrian prince and foreign minister, resigning. The demands of the Diet were agreed upon on 18 March by Emperor Ferdinand. Although Hungary would remain part of the monarchy through personal union

A personal union is the combination of two or more states that have the same monarch while their boundaries, laws, and interests remain distinct. A real union, by contrast, would involve the constituent states being to some extent interli ...

with the emperor, a constitutional government would be founded. The Diet then passed the April laws that established equality before the law, a legislature, a hereditary constitutional monarchy, and an end to the transfer and restrictions of land use.

The revolution grew into a war for independence from the Habsburg monarchy

The Habsburg monarchy (german: Habsburgermonarchie, ), also known as the Danubian monarchy (german: Donaumonarchie, ), or Habsburg Empire (german: Habsburgerreich, ), was the collection of empires, kingdoms, duchies, counties and other polities ...

when Josip Jelačić

Count Josip Jelačić von Bužim (16 October 180120 May 1859; also spelled ''Jellachich'', ''Jellačić'' or ''Jellasics''; hr, Josip grof Jelačić Bužimski; hu, Jelasics József) was a Croatian lieutenant field marshal in the Imperial-Roy ...

, Ban of Croatia, crossed the border to restore their control. The new government, led by Lajos Kossuth

Lajos Kossuth de Udvard et Kossuthfalva (, hu, udvardi és kossuthfalvi Kossuth Lajos, sk, Ľudovít Košút, anglicised as Louis Kossuth; 19 September 1802 – 20 March 1894) was a Hungarian nobleman, lawyer, journalist, polit ...

, was initially successful against the Habsburg forces. Although Hungary took a national united stand for its freedom, some minorities of the Kingdom of Hungary, including the Serbs of Vojvodina, the Romanians of Transylvania and some Slovaks of Upper Hungary supported the Habsburg Emperor and fought against the Hungarian Revolutionary Army. Eventually, after one and a half years of fighting, the revolution was crushed when Russian Tsar Nicholas I marched into Hungary with over 300,000 troops. As result of the defeat, Hungary was thus placed under brutal martial law. The leading rebels like Kossuth fled into exile or were executed. In the long run, the passive resistance following the revolution, along with the crushing Austrian defeat in the 1866 Austro-Prussian War

The Austro-Prussian War, also by many variant names such as Seven Weeks' War, German Civil War, Brothers War or Fraternal War, known in Germany as ("German War"), (; "German war of brothers") and by a variety of other names, was fought in 186 ...

, led to the Austro-Hungarian Compromise (1867), which marked the birth of the Austro-Hungarian Empire

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

.

Galicia

The center of the Ukrainian national movement was inGalicia

Galicia may refer to:

Geographic regions

* Galicia (Spain), a region and autonomous community of northwestern Spain

** Gallaecia, a Roman province

** The post-Roman Kingdom of the Suebi, also called the Kingdom of Gallaecia

** The medieval King ...

, which is today divided between Ukraine and Poland. On 19 April 1848, a group of representatives led by the Greek Catholic clergy launched a petition to the Austrian Emperor. It expressed wishes that in those regions of Galicia where the Ruthenian (Ukrainian) population represented the majority, the Ukrainian language

Ukrainian ( uk, украї́нська мо́ва, translit=ukrainska mova, label=native name, ) is an East Slavic language of the Indo-European language family. It is the native language of about 40 million people and the official state lan ...

should be taught at schools and used to announce official decrees for the peasantry; local officials were expected to understand it and the Ruthenian clergy was to be equalized in their rights with the clergy of all other denominations.

On 2 May 1848, the Supreme Ruthenian (Ukrainian) Council was established. The council (1848–1851) was headed by the Greek-Catholic Bishop Gregory Yakhimovich and consisted of 30 permanent members. Its main goal was the administrative division of Galicia into Western (Polish) and Eastern (Ruthenian/Ukrainian) parts within the borders of the Habsburg Empire, and formation of a separate region with a political self-governance.

Sweden

During 18–19 March, a series of riots known as theMarch Unrest

The March Unrest ( sv, Marsoroligheterna ) was a brief series of riots which occurred in the Swedish capital Stockholm during the Revolutions of 1848.

On 2 March 1848, news of the French Revolution of 1848 reached Stockholm. On the morning of 1 ...

(''Marsoroligheterna'') took place in the Swedish capital of Stockholm. Declarations with demands of political reform were spread in the city and a crowd was dispersed by the military, leading to 18 casualties.

Switzerland

Switzerland, already an alliance of republics, also saw an internal struggle. The attempted secession of seven Catholic cantons to form an alliance known as the ''Sonderbund'' ("separate alliance") in 1845 led to a short civil conflict in November 1847 in which around 100 people were killed. The ''Sonderbund'' was decisively defeated by the Protestant cantons, which had a larger population. A new constitution of 1848 ended the almost-complete independence of the cantons, transforming Switzerland into a federal state.Greater Poland

Polish people mounted a military insurrection against thePrussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an e ...

ns in the Grand Duchy of Posen

The Grand Duchy of Posen (german: Großherzogtum Posen; pl, Wielkie Księstwo Poznańskie) was part of the Kingdom of Prussia, created from territories annexed by Prussia after the Partitions of Poland, and formally established following the ...

(or the Greater Poland

Greater Poland, often known by its Polish name Wielkopolska (; german: Großpolen, sv, Storpolen, la, Polonia Maior), is a historical region of west-central Poland. Its chief and largest city is Poznań followed by Kalisz, the oldest cit ...

region), a part of Prussia since its annexation in 1815. The Poles tried to establish a Polish political entity, but refused to cooperate with the Germans and the Jews. The Germans decided they were better off with the status quo, so they assisted the Prussian governments in recapturing control. In the long-term, the uprising stimulated nationalism among both the Poles and the Germans and brought civil equality to the Jews.

Romanian Principalities

A Romanian liberal and Romantic nationalist uprising began in June in the principality of

A Romanian liberal and Romantic nationalist uprising began in June in the principality of Wallachia

Wallachia or Walachia (; ro, Țara Românească, lit=The Romanian Land' or 'The Romanian Country, ; archaic: ', Romanian Cyrillic alphabet: ) is a historical and geographical region of Romania. It is situated north of the Lower Danube and s ...

. Its goals were administrative autonomy, abolition of serfdom, and popular self-determination. It was closely connected with the 1848 unsuccessful revolt in Moldavia, it sought to overturn the administration imposed by Imperial Russian authorities under the ''Regulamentul Organic

''Regulamentul Organic'' (, Organic Regulation; french: Règlement Organique; russian: Органический регламент, Organichesky reglament)The name also has plural versions in all languages concerned, referring to the dual na ...

'' regime, and, through many of its leaders, demanded the abolition of boyar

A boyar or bolyar was a member of the highest rank of the feudal nobility in many Eastern European states, including Kievan Rus', Bulgaria, Russia, Wallachia and Moldavia, and later Romania, Lithuania and among Baltic Germans. Boyars were ...

privilege. Led by a group of young intellectuals and officers in the Wallachian military forces, the movement succeeded in toppling the ruling Prince

A prince is a male ruler (ranked below a king, grand prince, and grand duke) or a male member of a monarch's or former monarch's family. ''Prince'' is also a title of nobility (often highest), often hereditary, in some European states. ...

Gheorghe Bibescu

Gheorghe Bibescu (;April 26th 1804 – 1 June 1873) was a ''hospodar'' (Prince) of Wallachia between 1843 and 1848. His rule coincided with the revolutionary tide that culminated in the 1848 Wallachian revolution.

Early political career

Born in ...

, whom it replaced with a provisional government and a regency

A regent (from Latin : ruling, governing) is a person appointed to govern a state '' pro tempore'' (Latin: 'for the time being') because the monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge the powers and duties of the monarchy ...

, and in passing a series of major liberal reforms, first announced in the Proclamation of Islaz.

Despite its rapid gains and popular backing, the new administration was marked by conflicts between the radical wing and more conservative forces, especially over the issue of land reform

Land reform is a form of agrarian reform involving the changing of laws, regulations, or customs regarding land ownership. Land reform may consist of a government-initiated or government-backed property redistribution, generally of agricultura ...

. Two successive abortive coups weakened the new government, and its international status was always contested by Russia. After managing to rally a degree of sympathy from Ottoman political leaders, the Revolution was ultimately isolated by the intervention of Russian diplomats. In September 1848 by agreement with the Ottomans, Russia invaded and put down the revolution. According to Vasile Maciu, the failures were attributable in Wallachia to foreign intervention, in Moldavia to the opposition of the feudalists, and in Transylvania to the failure of the campaigns of General Józef Bem, and later to Austrian repression. In later decades, the rebels returned and gained their goals.

Belgium

Belgium did not see major unrest in 1848; it had already undergone a liberal reform after the Revolution of 1830 and thus its constitutional system and its monarchy survived. A number of small local riots broke out, concentrated in the ''sillon industriel

The ''Sillon industriel'' (, "industrial furrow") is the former industrial backbone of Belgium. It runs across the region of Wallonia, passing from Dour, the region of Borinage, in the west, to Verviers in the east, passing along the way throug ...

'' industrial region of the provinces of Liège

Liège ( , , ; wa, Lîdje ; nl, Luik ; german: Lüttich ) is a major city and municipality of Wallonia and the capital of the Belgian province of Liège.

The city is situated in the valley of the Meuse, in the east of Belgium, not far fro ...

and Hainaut.

The most serious threat of revolutionary contagion, however, was posed by Belgian émigré groups from France. In 1830 the Belgian Revolution had broken out inspired by the revolution occurring in France, and Belgian authorities feared that a similar 'copycat' phenomenon might occur in 1848. Shortly after the revolution in France, Belgian migrant workers living in Paris were encouraged to return to Belgium to overthrow the monarchy and establish a republic. Belgian authorities expelled Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist, critic of political economy, and socialist revolutionary. His best-known titles are the 1848 ...

himself from Brussels in early March on accusations of having used part of his inheritance to arm Belgian revolutionaries.

Around 6,000 armed émigrés of the "Belgian Legion

Several military units have been known as the Belgian Legion. The term "Belgian Legion" can refer to Belgian volunteers who served in the French Revolutionary Wars, Napoleonic Wars, Revolutions of 1848 and, more commonly, the Mexico Expedition ...

" attempted to cross the Belgian frontier. There were two divisions which were formed. The first group, travelling by train, were stopped and quickly disarmed at Quiévrain

Quiévrain (; pcd, Kievrin) is a municipality of Wallonia located in the province of Hainaut, Belgium.

On 1 January 2006, the municipality had 6,559 inhabitants. The total area is 21.22 km2, giving a population density of 309 inhabitants p ...

on 26 March 1848. The second group crossed the border on 29 March and headed for Brussels. They were confronted by Belgian troops at the hamlet of Risquons-Tout and defeated. Several smaller groups managed to infiltrate Belgium, but the reinforced Belgian border troops succeeded and the defeat at Risquons-Tout effectively ended the revolutionary threat to Belgium.

The situation in Belgium began to recover that summer after a good harvest, and fresh elections returned a strong majority to the governing party.

Ireland

A tendency common in the revolutionary movements of 1848 was a perception that the liberal monarchies set up in the 1830s, despite formally being representative parliamentary democracies, were too oligarchical and/or corrupt to respond to the urgent needs of the people, and were therefore in need of drastic democratic overhaul or, failing that, separatism to build a democratic state from scratch. This was the process that occurred in Ireland between 1801 and 1848. Previously a separate kingdom, Ireland was incorporated into the United Kingdom in 1801. Although its population was made up largely of Catholics, and sociologically of agricultural workers, tensions arose from the political over-representation, in positions of power, of landowners of Protestant background who were loyal to the United Kingdom. From the 1810s a conservative-liberal movement led byDaniel O'Connell

Daniel O'Connell (I) ( ga, Dónall Ó Conaill; 6 August 1775 – 15 May 1847), hailed in his time as The Liberator, was the acknowledged political leader of Ireland's Roman Catholic majority in the first half of the 19th century. His mobilizat ...

had sought to secure equal political rights for Catholics ''within'' the British political system, successful in the Roman Catholic Relief Act 1829

The Catholic Relief Act 1829, also known as the Catholic Emancipation Act 1829, was passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom in 1829. It was the culmination of the process of Catholic emancipation throughout the United Kingdom of Great Br ...

. But as in other European states, a current inspired by Radicalism criticized the conservative-liberals for pursuing the aim of democratic equality with excessive compromise and gradualism.

In Ireland a current of

In Ireland a current of nationalist

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: Th ...

, egalitarian

Egalitarianism (), or equalitarianism, is a school of thought within political philosophy that builds from the concept of social equality, prioritizing it for all people. Egalitarian doctrines are generally characterized by the idea that all hu ...

and Radical

Radical may refer to:

Politics and ideology Politics

* Radical politics, the political intent of fundamental societal change

*Radicalism (historical), the Radical Movement that began in late 18th century Britain and spread to continental Europe an ...

republicanism, inspired by the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are conside ...

, had been present since the 1790s being expressed initially in the Irish Rebellion of 1798

The Irish Rebellion of 1798 ( ga, Éirí Amach 1798; Ulster-Scots: ''The Hurries'') was a major uprising against British rule in Ireland. The main organising force was the Society of United Irishmen, a republican revolutionary group influenced ...

. This tendency grew into a movement for social, cultural and political reform during the 1830s, and in 1839 was realized into a political association called Young Ireland

Young Ireland ( ga, Éire Óg, ) was a political and cultural movement in the 1840s committed to an all-Ireland struggle for independence and democratic reform. Grouped around the Dublin weekly ''The Nation'', it took issue with the compromise ...

. It was initially not well received, but grew more popular with the Great Famine of 18451849, an event that brought catastrophic social effects and which threw into light the inadequate response of authorities.

The spark for the Young Irelander Revolution came in 1848 when the British Parliament passed the " Crime and Outrage Bill". The Bill was essentially a declaration of martial law in Ireland, designed to create a counter-insurgency

Counterinsurgency (COIN) is "the totality of actions aimed at defeating irregular forces". The Oxford English Dictionary defines counterinsurgency as any "military or political action taken against the activities of guerrillas or revolutionar ...

against the growing Irish nationalist movement.

In response, the Young Ireland Party launched its rebellion in July 1848, gathering landlords and tenants to its cause.

But its first major engagement against police, in the village of Ballingarry, South Tipperary

Ballingarry () is a village and civil parish in County Tipperary, Ireland. Ballingarry is one of 19 civil parishes in the barony of Slievardagh, and also an ecclesiastical parish in the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Cashel and Emly. Ballingar ...

, was a failure. A long gunfight with around 50 armed police

The police are a Law enforcement organization, constituted body of Law enforcement officer, persons empowered by a State (polity), state, with the aim to law enforcement, enforce the law, to ensure the safety, health and possessions of citize ...

ended when police reinforcements arrived. After the arrest of the Young Ireland leaders, the rebellion collapsed, though intermittent fighting continued for the next year,

It is sometimes called the ''Famine Rebellion'' (since it took place during the Great Famine).

Spain

While no revolution occurred in Spain in the year 1848, a similar phenomenon occurred. During this year, the country was going through the Second Carlist War. The European revolutions erupted at a moment when the political regime in Spain faced great criticism from within one of its two main parties, and by 1854 a radical-liberal revolution and a conservative-liberal counter-revolution had both occurred. Since 1833, Spain had been governed by a conservative-liberalparliamentary monarchy

A constitutional monarchy, parliamentary monarchy, or democratic monarchy is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in decision making. Constitutional monarchies dif ...

similar to and modelled on the July Monarchy

The July Monarchy (french: Monarchie de Juillet), officially the Kingdom of France (french: Royaume de France), was a liberal constitutional monarchy in France under , starting on 26 July 1830, with the July Revolution of 1830, and ending 23 ...

in France. In order to exclude absolute monarchists from government, power had alternated between two liberal parties: the center-left Progressive Party, and the center-right Moderate Party

The Moderate Party ( sv, Moderata samlingspartiet , ; M), commonly referred to as the Moderates ( ), is a liberal-conservative political party in Sweden. The party generally supports tax cuts, the free market, civil liberties and economic ...

. But a decade of rule by the center-right Moderates had recently produced a constitutional reform (1845), prompting fears that the Moderates sought to reach out to Absolutists and permanently exclude the Progressives. The left-wing of the Progressive Party, which had historical links to Jacobinism

A Jacobin (; ) was a member of the Jacobin Club, a revolutionary political movement that was the most famous political club during the French Revolution (1789–1799).

The club got its name from meeting at the Dominican rue Saint-Honoré M ...

and Radicalism, began to push for root-and-branch reforms to the constitutional monarchy, notably universal male suffrage

Universal manhood suffrage is a form of voting rights in which all adult male citizens within a political system are allowed to vote, regardless of income, property, religion, race, or any other qualification. It is sometimes summarized by the slo ...

and parliamentary sovereignty

Parliamentary sovereignty, also called parliamentary supremacy or legislative supremacy, is a concept in the constitutional law of some parliamentary democracies. It holds that the legislative body has absolute sovereignty and is supreme over ...

.

The European Revolutions of 1848 and particularly the French Second Republic

The French Second Republic (french: Deuxième République Française or ), officially the French Republic (), was the republican government of France that existed between 1848 and 1852. It was established in February 1848, with the February Re ...

prompted the Spanish radical movement to adopt positions incompatible with the existing constitutional regime, notably republicanism

Republicanism is a political ideology centered on citizenship in a state organized as a republic. Historically, it emphasises the idea of self-rule and ranges from the rule of a representative minority or oligarchy to popular sovereignty. ...

. This ultimately led the Radicals to exit the Progressive Party to form the Democratic Party in 1849.

Over the next years, two revolutions occurred. In 1854, the conservatives of the Moderate Party were ousted after a decade in power by an alliance of Radicals, Liberals and liberal Conservatives led by Generals Espartero and O'Donnell. In 1856, the more conservative half of this alliance launched a second revolution to oust the republican Radicals, leading to a new 10-year period of government by conservative-liberal monarchists.

Taken together, the two revolutions can be thought of as echoing aspects of the French Second Republic

The French Second Republic (french: Deuxième République Française or ), officially the French Republic (), was the republican government of France that existed between 1848 and 1852. It was established in February 1848, with the February Re ...

: the Spanish Revolution of 1854, as a revolt by Radicals and Liberals against the oligarchical, conservative-liberal parliamentary monarchy of the 1830s, mirrored the French Revolution of 1848

The French Revolution of 1848 (french: Révolution française de 1848), also known as the February Revolution (), was a brief period of civil unrest in France, in February 1848, that led to the collapse of the July Monarchy and the foundatio ...

; while the Spanish Revolution of 1856, as a counter-revolution of conservative-liberals under a military strongman, had echoes of Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte's coup against the French Second Republic.

Other European states

Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It ...

, Belgium, the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

, Portugal