Speaker's House on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Speaker's House is the residence of the

The first Speaker to be granted an official residence was

The first Speaker to be granted an official residence was

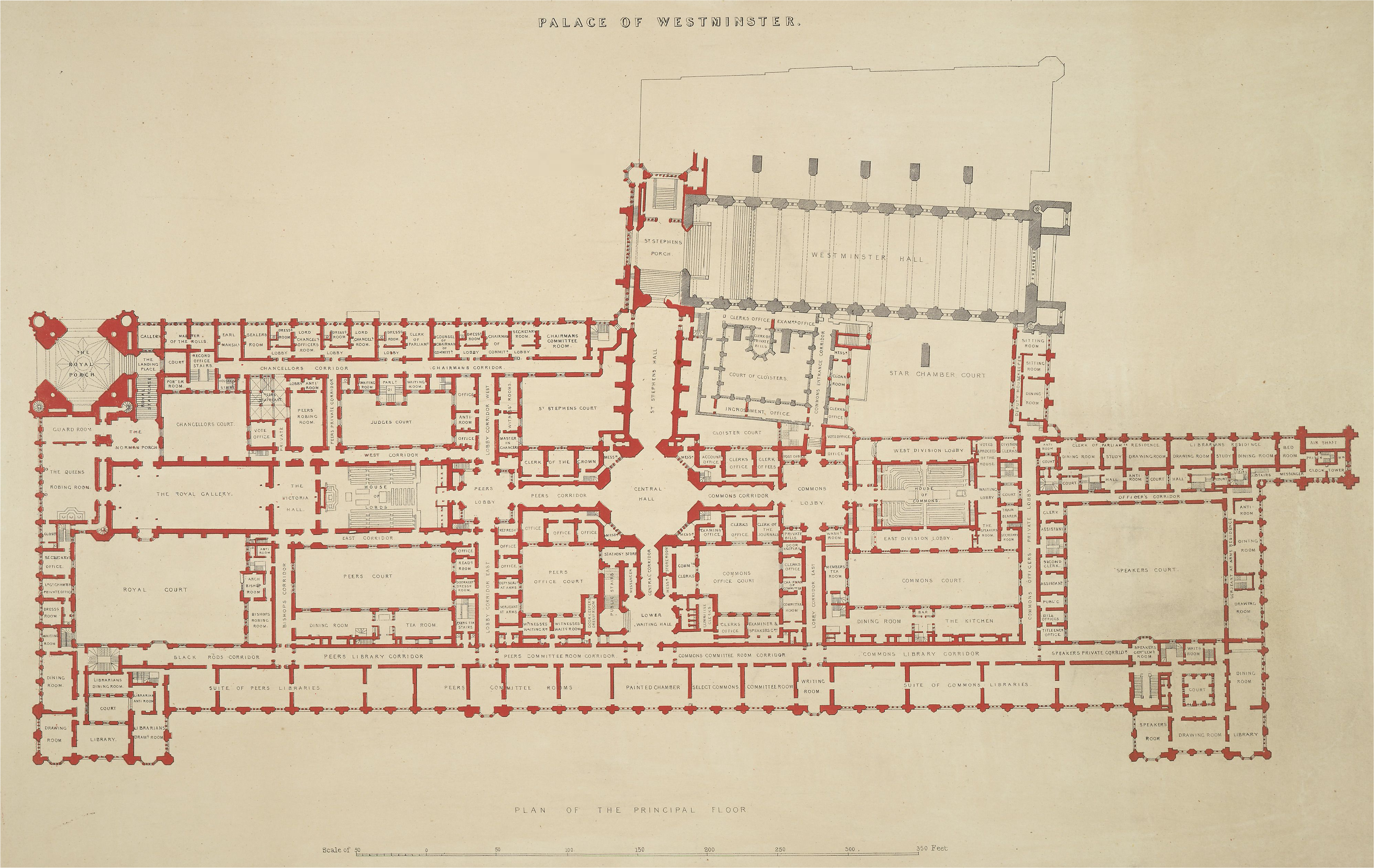

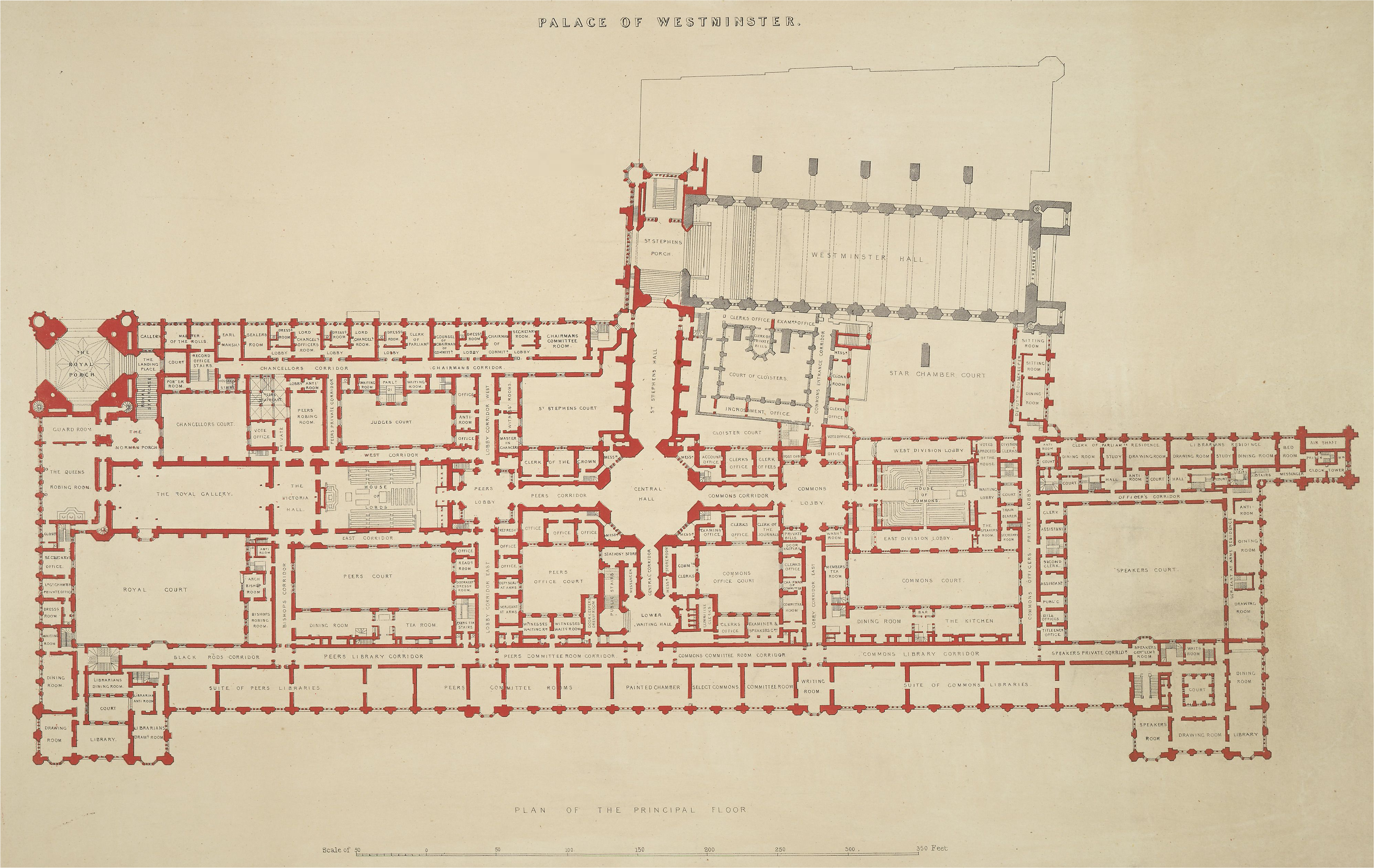

Speaker's Court forms the entrance to the Speaker's House and looking south, is situated on the left hand side of

Speaker's Court forms the entrance to the Speaker's House and looking south, is situated on the left hand side of  The principal rooms of the speaker's residence at the time of the construction of the house in the 1850s were the State Dining Room, drawing room, ordinary dining room, and morning and waiting rooms. The rooms are decorated in the Gothic revival style of the rebuilt Palace of Westminster. The state dining room is 43 feet long, 23 feet wide, and 21 feet high. Its ceiling is divided into richly carved and gilded bays, with square panels bearing the arms of the Houses of

The principal rooms of the speaker's residence at the time of the construction of the house in the 1850s were the State Dining Room, drawing room, ordinary dining room, and morning and waiting rooms. The rooms are decorated in the Gothic revival style of the rebuilt Palace of Westminster. The state dining room is 43 feet long, 23 feet wide, and 21 feet high. Its ceiling is divided into richly carved and gilded bays, with square panels bearing the arms of the Houses of

Speaker of the House of Commons Speaker of the House of Commons is a political leadership position found in countries that have a House of Commons, where the membership of the body elects a speaker to lead its proceedings.

Systems that have such a position include:

*Speaker of ...

, the lower house

A lower house is one of two chambers of a bicameral legislature, the other chamber being the upper house. Despite its official position "below" the upper house, in many legislatures worldwide, the lower house has come to wield more power or ot ...

and primary chamber of the Parliament of the United Kingdom

The Parliament of the United Kingdom is the Parliamentary sovereignty in the United Kingdom, supreme Legislature, legislative body of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace of We ...

. It is located in the Palace of Westminster

The Palace of Westminster serves as the meeting place for both the House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two houses of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Informally known as the Houses of Parliament, the Palace lies on the north ban ...

in London. It was originally located next to St Stephen's Chapel

St Stephen's Chapel, sometimes called the Royal Chapel of St Stephen, was a chapel completed around 1297 in the old Palace of Westminster which served as the chamber of the House of Commons of England and that of Great Britain from 1547 to 1834 ...

and was rebuilt and enlarged by James Wyatt

James Wyatt (3 August 1746 – 4 September 1813) was an English architect, a rival of Robert Adam in the neoclassical and neo-Gothic styles. He was elected to the Royal Academy in 1785 and was its president from 1805 to 1806.

Early life

W ...

in the early 19th century. After the burning of Parliament

The Palace of Westminster, the medieval royal palace used as the home of the British parliament, was largely destroyed by fire on 16 October 1834. The blaze was caused by the burning of small wooden tally sticks which had been used as part o ...

in 1834 it was rebuilt by Charles Barry

Sir Charles Barry (23 May 1795 – 12 May 1860) was a British architect, best known for his role in the rebuilding of the Palace of Westminster (also known as the Houses of Parliament) in London during the mid-19th century, but also responsi ...

as part of the new Palace of Westminster in the Perpendicular Gothic

Perpendicular Gothic (also Perpendicular, Rectilinear, or Third Pointed) architecture was the third and final style of English Gothic architecture developed in the Kingdom of England during the Late Middle Ages, typified by large windows, four-ce ...

Revival style. It is located at the northeast corner of the palace and is used for official functions and meetings. Each day, prior to the sitting of the House of Commons, the Speaker and other officials walk in procession from the apartments to the House of Commons Chamber.

Design

Pre-1834

The first Speaker to be granted an official residence was

The first Speaker to be granted an official residence was Henry Addington

Henry Addington, 1st Viscount Sidmouth, (30 May 175715 February 1844) was an English Tory statesman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1801 to 1804.

Addington is best known for obtaining the Treaty of Amiens in 1802, a ...

in 1790. Official dinners were given by the Speaker in the crypt under St Stephen's Chapel

St Stephen's Chapel, sometimes called the Royal Chapel of St Stephen, was a chapel completed around 1297 in the old Palace of Westminster which served as the chamber of the House of Commons of England and that of Great Britain from 1547 to 1834 ...

(the crypt is now St Mary Undercroft

The Chapel of St Mary Undercroft is a Church of England chapel located in the Palace of Westminster, London, England. The chapel is accessed via a flight of stairs in the south east corner of Westminster Hall.

It had been a crypt below St Steph ...

). The original Speaker's House adjoined St Stephen's Chapel

St Stephen's Chapel, sometimes called the Royal Chapel of St Stephen, was a chapel completed around 1297 in the old Palace of Westminster which served as the chamber of the House of Commons of England and that of Great Britain from 1547 to 1834 ...

. The writer Theodore Hook

Theodore Edward Hook (22 September 1788 – 24 August 1841) was an English man of letters and composer and briefly a civil servant in Mauritius. He is best known for his practical jokes, particularly the Berners Street hoax in 1809. The w ...

was frequently entertained there by Sir Charles Manners-Sutton during his speakership. The Speaker's House was rebuilt by James Wyatt

James Wyatt (3 August 1746 – 4 September 1813) was an English architect, a rival of Robert Adam in the neoclassical and neo-Gothic styles. He was elected to the Royal Academy in 1785 and was its president from 1805 to 1806.

Early life

W ...

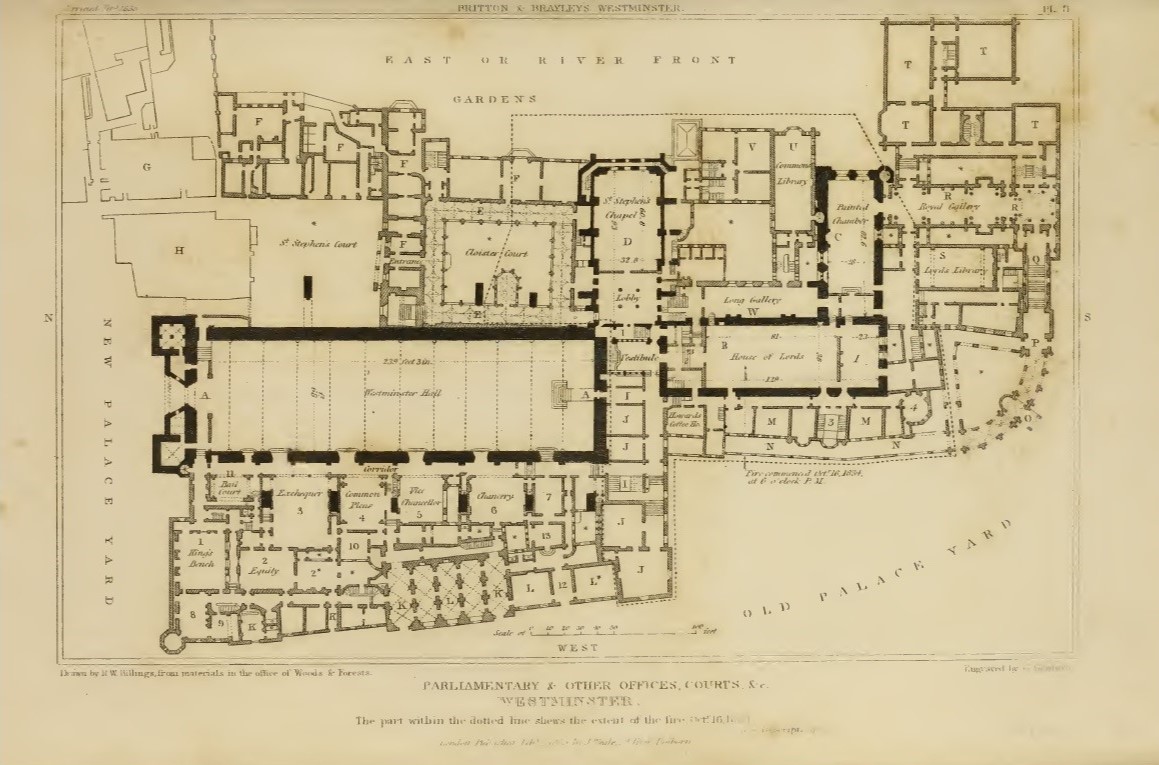

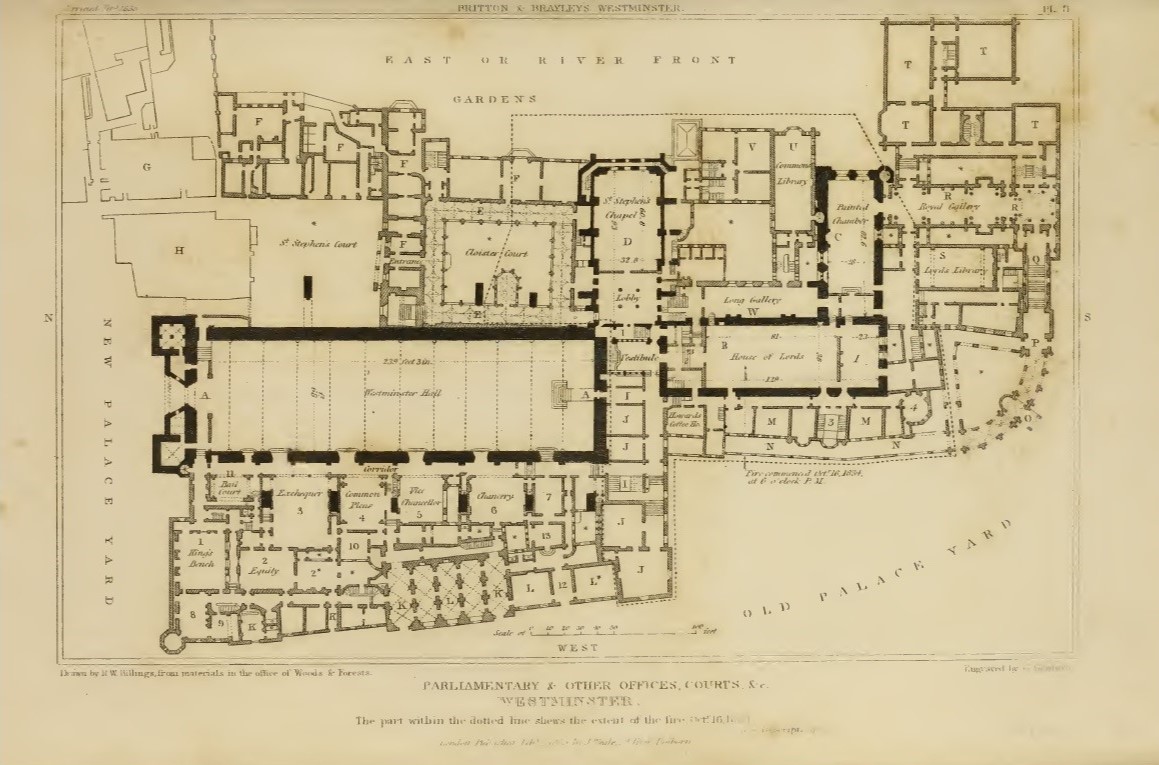

between 1802 and 1808. Wyatt also constructed a new group of offices at the east side of Old Palace Yard; these buildings and the Speaker's House were the only completed structures of his masterplan for the palace before his 1813 death. The total cost of these two projects was in excess of £200,000 ().

Speaker Charles Abbot wrote in his diary in 1803 that the "rebuilding and altering the Speaker's House, which Mr. Wyatt had promised to complete before winter, proceeded very slowly", but he had still been able to host parliamentarians for dinners. At a dinner at the home of Lord Camden

Marquess Camden is a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. It was created in 1812 for the politician John Pratt, 2nd Earl Camden. The Pratt family descends from Sir John Pratt, Lord Chief Justice from 1718 to 1725. His third son from his ...

in 1808, The 1st Duke of Cumberland and Teviotdale told Abbot that the Whig MP George Tierney

George Tierney PC (20 March 1761 – 25 January 1830) was an Irish Whig politician. For much of his career he was in opposition to the governments of William Pitt and Lord Liverpool. From 1818 to 1821 he was Leader of the Opposition in the ...

would be complaining in the Commons about the expenditure of £70,000 on the Speaker's House (). Abbot told Cumberland that Tierney should take the issue up with Wyatt. John Britton, writing in his 1815 book ''Beauties of England and Wales'', describes the Speaker's House as having been greatly altered, enlarged and beautified under the direction of Wyatt and that it was "most exquistly and tastefully ornimated" under Speaker Abbot. Following the fire in 1834, the Speaker's residence was partly located at the nearby Jewel Tower. The speaker also lived in a house in Eaton Square

Eaton Square is a rectangular, residential garden square in London's Belgravia district. It is the largest square in London. It is one of the three squares built by the landowning Grosvenor family when they developed the main part of Belgravi ...

in Belgravia

Belgravia () is a district in Central London, covering parts of the areas of both the City of Westminster and the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea.

Belgravia was known as the 'Five Fields' during the Tudor Period, and became a dangero ...

while the Palace of Westminster was being rebuilt.

Present residence

After theburning of Parliament

The Palace of Westminster, the medieval royal palace used as the home of the British parliament, was largely destroyed by fire on 16 October 1834. The blaze was caused by the burning of small wooden tally sticks which had been used as part o ...

in 1834, it was rebuilt by Charles Barry

Sir Charles Barry (23 May 1795 – 12 May 1860) was a British architect, best known for his role in the rebuilding of the Palace of Westminster (also known as the Houses of Parliament) in London during the mid-19th century, but also responsi ...

as part of the new Palace of Westminster in the Perpendicular Gothic

Perpendicular Gothic (also Perpendicular, Rectilinear, or Third Pointed) architecture was the third and final style of English Gothic architecture developed in the Kingdom of England during the Late Middle Ages, typified by large windows, four-ce ...

Revival style. Barry had won the competition to rebuild the palace in 1836, and the foundation stone was laid in 1840. The new residence of the Speaker was completed in 1859, it being one of the last parts of the new Palace of Westminster to be completed. It was rebuilt under the direction of Thomas Quarm, the Clerk of Works, and decorated by John Gregory Crace. The furniture was designed by John Braund, and made by Holland and Sons. The furniture was largely completed by January 1859, with the contract being accepted in August 1858. It is located at the north east corner of the palace.

The residence forms a rough parallelogram measuring . The Speaker's House was described in the 1878 book ''Old and New London'' as "of considerable extent, comprising from sixty to seventy rooms" with the "staircase, its carvings, tile-paving, and brass-work, is exceedingly effective and elegant, and everywhere there is a large amount of painted and gilded decoration".

Speaker's Court forms the entrance to the Speaker's House and looking south, is situated on the left hand side of

Speaker's Court forms the entrance to the Speaker's House and looking south, is situated on the left hand side of New Palace Yard

New Palace Yard is a yard (area of grounds) northwest of the Palace of Westminster in Westminster, London, England. It is part of the grounds not open to the public. However, it can be viewed from the two adjoining streets, as a result of Edward ...

. The court is entered by two "not very imposing" archways, as described in an article in ''The Illustrated London News

''The Illustrated London News'' appeared first on Saturday 14 May 1842, as the world's first illustrated weekly news magazine. Founded by Herbert Ingram, it appeared weekly until 1971, then less frequently thereafter, and ceased publication in ...

'', which said that "spacious as the area which presents itself, and lofty as are the buildings which form its four sides, the appearance of the house as a whole is not particularly striking". An elaborate porch forms the main entrance of the house, surmounted by oriel window

An oriel window is a form of bay window which protrudes from the main wall of a building but does not reach to the ground. Supported by corbels, brackets, or similar cantilevers, an oriel window is most commonly found projecting from an upper fl ...

s. Sculptured lions surmount the four angles of the entrance with a relief of the House of Commons mace. Five quatrefoil

A quatrefoil (anciently caterfoil) is a decorative element consisting of a symmetrical shape which forms the overall outline of four partially overlapping circles of the same diameter. It is found in art, architecture, heraldry and traditional ...

s enriched with roses run along the edge of the porch. A band above the arch is inscribed with the Christian text " Domine salvum fac regem" ("Lord save the king"). Inside the porch ceiling panels are decorated with the armorial bearings of previous speakers and the entrance hall is richly decorated, paved with Mintons floor tiles and stone panels with carved fretwork

Fretwork is an interlaced decorative design that is either carved in low relief on a solid background, or cut out with a fretsaw, coping saw, jigsaw or scroll saw. Most fretwork patterns are geometric in design. The materials most commonly use ...

. A grand staircase leads from the entrance hall; tall standard lamps adorn the steps at the bottom of the stairs. The staircase reaches a landing and branches off on either side, enclosing the hall. The balustrades

A baluster is an upright support, often a vertical moulded shaft, square, or lathe-turned form found in stairways, parapets, and other architectural features. In furniture construction it is known as a spindle. Common materials used in its con ...

along the staircase are moulded in highly polished brass. The cornice

In architecture, a cornice (from the Italian ''cornice'' meaning "ledge") is generally any horizontal decorative moulding that crowns a building or furniture element—for example, the cornice over a door or window, around the top edge of a ...

of the hall features armorial shields of the speakers, with the gilded and painted armorial bearings of England at their centre. A skylight above the hall is made of decorative stained glass.

An audience room leads to large cloisters. ''The Illustrated London News'' described the cloisters as "one of the chief, if not the chief, ornaments of the whole building". The cloisters are each long, wide, and in height; with the roof of the cloisters decorated with fan-groined arches with tracery

Tracery is an architectural device by which windows (or screens, panels, and vaults) are divided into sections of various proportions by stone ''bars'' or ''ribs'' of moulding. Most commonly, it refers to the stonework elements that support the ...

. ''The Illustrated London News'' described the tracery as spread over the cloisters "like a network of stone, giving the most exquisite effects of light and shade; while four lanterns in each cloister light it with a soft, mellow richness that becomes the place and its associations". The cloisters overlook the inner quadrangle of the Speaker's Court and have canopied Gothic stained-glass windows. The windows depict the name, date, and coats of arms of every known speaker.

The principal rooms of the speaker's residence at the time of the construction of the house in the 1850s were the State Dining Room, drawing room, ordinary dining room, and morning and waiting rooms. The rooms are decorated in the Gothic revival style of the rebuilt Palace of Westminster. The state dining room is 43 feet long, 23 feet wide, and 21 feet high. Its ceiling is divided into richly carved and gilded bays, with square panels bearing the arms of the Houses of

The principal rooms of the speaker's residence at the time of the construction of the house in the 1850s were the State Dining Room, drawing room, ordinary dining room, and morning and waiting rooms. The rooms are decorated in the Gothic revival style of the rebuilt Palace of Westminster. The state dining room is 43 feet long, 23 feet wide, and 21 feet high. Its ceiling is divided into richly carved and gilded bays, with square panels bearing the arms of the Houses of York

York is a cathedral city with Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. It is the historic county town of Yorkshire. The city has many historic buildings and other structures, such as ...

and Lancaster, and the Portcullis of Westminster. The arms of former speakers are emblazoned on the cornice of the dining room. A full-length portrait of Speaker Charles Shaw-Lefevre, hung over the fireplace at the completion of the house in 1859. The fireplace in the dining room is made of dark grey marble and is a copy of an ancient fireplace at Windsor Castle

Windsor Castle is a royal residence at Windsor in the English county of Berkshire. It is strongly associated with the English and succeeding British royal family, and embodies almost a millennium of architectural history.

The original ...

. It is high and wide. It is richly decorated with emblems of three kingdoms, the arms of Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 216 days was longer than that of any previ ...

, crowns and the portcullis with the monogram "V.R.". The firedogs of the fireplace are of a lion and a unicorn holding banners.

The Speaker's House was refurbished in the 1980s under Sir Robert Cooke, who served as Special Advisor to the Palace of Westminster from 1979 until 1987. The present State Bedroom was created under Cooke; it was created from the drawing room of the adjacent Serjeant-at-Arms house, and linked by a new door to the State Dining Room. A canopied bed in the Speaker's House is intended for the British monarch to sleep in the night before their coronation. The bed was sold in the 1950s, and bought back to the house in the 1980s.

History

William IV

William IV (William Henry; 21 August 1765 – 20 June 1837) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and King of Hanover from 26 June 1830 until his death in 1837. The third son of George III, William succeeded ...

informed Speaker Charles Manners-Sutton

Charles Manners-Sutton (17 February 1755 – 21 July 1828; called Charles Manners before 1762) was a bishop in the Church of England who served as Archbishop of Canterbury from 1805 to 1828.

Life

Manners-Sutton was the fourth son of Lord Ge ...

of his intention to occupy Speaker's House for two days prior to his coronation on 8 September 1831. A dispute arose between the Lord Great Chamberlain

The Lord Great Chamberlain of England is the sixth of the Great Officers of State, ranking beneath the Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal and above the Lord High Constable. The Lord Great Chamberlain has charge over the Palace of Westminster (tho ...

and Manners-Sutton in 1834. It was the duty of the Lord Great Chamberlain to undress the King the night before his coronation, and to dress him the following morning. In return for this service the Lord Great Chamberlain was entitled to keep as his property the furniture of the room in which the King slept, the silver basin in which the King washed and any night apparel that he had worn. In his position as Deputy Lord Chamberlain, Lord Willoughby d'Eresby laid claim to the effects of the State Bedroom of Speaker's House for his service during William IV's coronation. The effects were granted to him by the Board of Claims that arose from the disputed accounts from the King's coronation, and he subsequently took possession of eight tapestry chairs, two tapestry sofas, and two tapestry screens. Though the property claimed by Lord Willoughby belonged to the State, Manners-Sutton bought it back from him, and subsequently made an application to the state for £5000 compensation for his losses in the 1834 fire and offered them the effects claimed by Lord Willoughby for 500 guinea

Guinea ( ),, fuf, 𞤘𞤭𞤲𞤫, italic=no, Gine, wo, Gine, nqo, ߖߌ߬ߣߍ߫, bm, Gine officially the Republic of Guinea (french: République de Guinée), is a coastal country in West Africa. It borders the Atlantic Ocean to the we ...

s. The House of Commons appointed a select committee to investigate the compensation claims of Manners-Sutton and other officials of the house and valued the furniture at £480 which he accepted. Before finalising the matter HM Treasury

His Majesty's Treasury (HM Treasury), occasionally referred to as the Exchequer, or more informally the Treasury, is a department of His Majesty's Government responsible for developing and executing the government's public finance policy and ec ...

asked Manners-Sutton for the receipt that Lord Willoughby had given him and it could not be procured. Manners-Sutton subsequently petitioned Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 216 days was longer than that of any previ ...

in 1842 for £10,000 compensation for his losses in the fire as his losses had occurred in a royal palace by the negligence of Crown servants. The case was argued before the Lord Chancellor

The lord chancellor, formally the lord high chancellor of Great Britain, is the highest-ranking traditional minister among the Great Officers of State in Scotland and England in the United Kingdom, nominally outranking the prime minister. Th ...

, John Copley, who ruled that Manners-Sutton's claim was unsustainable as the Crown could not be held responsible for the negligence of its agents.

A collection of painted portraits of the speakers dating back to the 1800s are displayed in a function room in the residence. The oldest portrait is of Thomas More

Sir Thomas More (7 February 1478 – 6 July 1535), venerated in the Catholic Church as Saint Thomas More, was an English lawyer, judge, social philosopher, author, statesman, and noted Renaissance humanist. He also served Henry VIII as Lor ...

, who served as Speaker in 1523; there is a gap until the portrait of Speaker Richard Onslow who served from 1566-1567. The collection has five portraits of Speakers from the 16th century, and 13 from the 17th century. There are 12 portraits from the 18th century, and the 19th century series of portraits is complete.

The speaker formally proceeds from Speaker's House to the House of Commons to start each day's parliamentary session. John Evelyn Denison

John Evelyn Denison, 1st Viscount Ossington, PC (27 January 1800 – 7 March 1873) was a British statesman who served as Speaker of the House of Commons from 1857 to 1872. He is the eponym of Speaker Denison's rule.

Background and education

De ...

was the first occupant of the rebuilt Speaker's House in 1857.

The basements of Speaker's House and of the residence of the Serjeant at Arms of the House of Commons were flooded by the River Thames in January 1928 after the failure of the water ejector system under Speaker's Green. Speaker's House was bombed in The Blitz

The Blitz was a German bombing campaign against the United Kingdom in 1940 and 1941, during the Second World War. The term was first used by the British press and originated from the term , the German word meaning 'lightning war'.

The Germa ...

in April 1941. A large water tank was damaged but there were no casualties. The windows of the House of Commons Library

The House of Commons Library is the library and information resource of the lower house of the British Parliament. It was established in 1818, although its original 1828 construction was destroyed during the burning of Parliament in 1834.

The ...

and terrace were smashed. A private flat was created for the Speaker's living accommodation on the first and second floors of Speaker's house in 1943.

During their 1956 visit to the UK, the Soviet First Secretary Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and chairman of the country's Council of Ministers from 1958 to 1964. During his rule, Khrushchev ...

and the Soviet Premier

The Premier of the Soviet Union (russian: Глава Правительства СССР) was the head of government of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). The office had four different names throughout its existence: Chairman of the ...

Nikolai Bulganin attended a dinner at Speaker's House with Speaker William Morrison and 39 others, including Prime Minister Anthony Eden

Robert Anthony Eden, 1st Earl of Avon, (12 June 1897 – 14 January 1977) was a British Conservative Party politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1955 until his resignation in 1957.

Achieving rapid prom ...

, Leader of the House of Commons

The leader of the House of Commons is a minister of the Crown of the Government of the United Kingdom whose main role is organising government business in the House of Commons. The leader is generally a member or attendee of the cabinet of the ...

Rab Butler, Foreign Secretary

The secretary of state for foreign, Commonwealth and development affairs, known as the foreign secretary, is a minister of the Crown of the Government of the United Kingdom and head of the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office. Seen as ...

Selwyn Lloyd

John Selwyn Brooke Lloyd, Baron Selwyn-Lloyd, (28 July 1904 – 18 May 1978) was a British politician. Born and raised in Cheshire, he was an active Liberal as a young man in the 1920s. In the following decade, he practised as a barrister and ...

, Leader of the Labour Party Hugh Gaitskell

Hugh Todd Naylor Gaitskell (9 April 1906 – 18 January 1963) was a British politician who served as Leader of the Labour Party and Leader of the Opposition from 1955 until his death in 1963. An economics lecturer and wartime civil servant, ...

and Lord Chancellor

The lord chancellor, formally the lord high chancellor of Great Britain, is the highest-ranking traditional minister among the Great Officers of State in Scotland and England in the United Kingdom, nominally outranking the prime minister. Th ...

Viscount Kilmuir.

Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother

Elizabeth Angela Marguerite Bowes-Lyon (4 August 1900 – 30 March 2002) was Queen of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 to 6 February 1952 as the wife of King George VI. She was th ...

visited George Thomas five times at Speaker's House during his speakership. Queen Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 1926 – 8 September 2022) was Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 6 February 1952 until her death in 2022. She was queen regnant of 32 sovereign states during ...

and Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh

Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh (born Prince Philip of Greece and Denmark, later Philip Mountbatten; 10 June 1921 – 9 April 2021) was the husband of Queen Elizabeth II. As such, he served as the consort of the British monarch from ...

had dinner with Speaker Betty Boothroyd

Betty Boothroyd, Baroness Boothroyd (born 8 October 1929) is a British politician who served as the Member of Parliament (MP) for West Bromwich and West Bromwich West from 1973 to 2000. From 1992 to 2000, she served as Speaker of the House of ...

at Speaker's House in November 1996. William

William is a male

Male (symbol: ♂) is the sex of an organism that produces the gamete (sex cell) known as sperm, which fuses with the larger female gamete, or ovum, in the process of fertilization.

A male organism cannot reproduce sex ...

and Ffion Hague's wedding reception was held at Speaker's House in December 1997. Boothroyd met her waxwork dummy at Speaker's House in June 1998 before its unveiling at Madame Tussauds

Madame Tussauds (, ) is a wax museum founded in 1835 by French wax sculptor Marie Tussaud in London, spawning similar museums in major cities around the world. While it used to be spelled as "Madame Tussaud's"; the apostrophe is no longer us ...

.

Michael Martin spent £724,600 refurbishing Speaker's House between the year of his appointment in 2000 and early 2008. £992,000 was spent on enhanced security for the residence and on the garden of the property. Speaker's House was refurbished by Speaker John Bercow

John Simon Bercow (; born 19 January 1963) is a British former politician who was Speaker of the House of Commons from 2009 to 2019, and Member of Parliament (MP) for Buckingham between 1997 and 2019. A member of the Conservative Party prior ...

in 2009 at an estimated cost of £20,000. Bercow was elected speaker after the resignation of Michael Martin in the wake of the MPs expenses scandal. Bercow had announced that he would not claim the allowance for a second home. The cost was funded by the Parliamentary Estates Directorate. The changes were made to accommodate his wife and three young children. Bercow said, "It's a fantastic apartment but it's not altogether child-friendly". One of the study rooms in the residence became a playroom. Bercow personally paid for a children's climbing frame and a Wendy house

A Wendy house is a United Kingdom term for a playhouse for children, which is large enough for one or more children to enter. Size and solidity can vary from a plastic kit to something resembling a real house in a child's size. Usually there ...

for Speaker's Green. Bercow's wife Sally described the view from Speakers House as "incredibly sexy, particularly at night with the moon and the glow from the old gas lamps". £2,000 was spent on beeswax candles in 2016 during Bercow's speakership. Overall expenditure on Speaker's House fell 19.4%, from £626,000 to £504,000, from 2009 to 2016.

The Aber Valley Male Voice Choir celebrated their golden anniversary with a performance at Speaker's House in 2009. Pupils from the London Welsh School sang songs at the door of Speaker's House to celebrate St David's Day

Saint David's Day ( cy, Dydd Gŵyl Dewi Sant or ; ), or the Feast of Saint David, is the feast day of Saint David, the patron saint of Wales, and falls on 1 March, the date of Saint David's death in 589 AD. The feast has been regularly celebrat ...

in March 2015.

A total of £12,636 was spent to prepare the residence for Sir Lindsay Hoyle when he became speaker. Some £7,500 was spent on bedding and mattresses; this included the replacement of four damaged or worn mattresses and bedding for "other overnight accommodation provision on the parliamentary estate". In May and June 2020 £89,506 was spent to remove asbestos at Speaker's House.

During the election of the speaker in 2019 Chris Bryant

Christopher John Bryant (born 11 January 1962) is a British politician and former Anglican priest who is the Chair of the Committees on Standards and Privileges. He previously served in government as Deputy Leader of the House of Commons from ...

vowed if elected to host more events for the spouses of parliamentarians at Speaker's House, and to have an event where MPs waited on Parliamentary staff, saying that he would like "to have some kind of event for the staff who run the building...with MPs serving".

The grand piano in the Speaker's House is available for members of parliament to play on request. In a 'mark of respect' to the House of Commons it has been a long-standing practice that parliamentarians elected for Sinn Féin

Sinn Féin ( , ; en, " eOurselves") is an Irish republican and democratic socialist political party active throughout both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland.

The original Sinn Féin organisation was founded in 1905 by Arthur ...

are not welcome at hospitality functions at the Speaker's House due to their abstentionism from the Commons. The practice was maintained by John Bercow during his speakership when an event to mark the centenary of the 1914 Home Rule Bill was due to be held at his residence with attendees invited by the Irish embassy in London.

References

* {{Parliamentary Estate Buildings and structures on the River Thames Burned buildings and structures in the United Kingdom Charles Barry buildings Gothic Revival architecture in London Houses completed in 1859 Houses in the City of Westminster James Wyatt buildings Official residences in the United Kingdom Palace of Westminster Speakers of the British House of Commons