Spanish Florida on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Spanish Florida ( es, La Florida) was the first major European land claim and attempted settlement in North America during the European

Spanish Florida was established in 1513, when Juan Ponce de León claimed peninsular Florida for Spain during the first official European expedition to North America. This claim was enlarged as several explorers (most notably Pánfilo Narváez and Hernando de Soto) landed near

Spanish Florida was established in 1513, when Juan Ponce de León claimed peninsular Florida for Spain during the first official European expedition to North America. This claim was enlarged as several explorers (most notably Pánfilo Narváez and Hernando de Soto) landed near

In 1512 Juan Ponce de León, governor of

In 1512 Juan Ponce de León, governor of

Menéndez de Avilés quickly set out to attack Fort Caroline, traveling overland from St. Augustine. At the same time, Ribault sailed from Fort Caroline, intending to attack St. Augustine from the sea. The French fleet, however, was pushed out to sea and decimated by a squall. Meanwhile, the Spanish overwhelmed the lightly defended Fort Caroline, sparing only the women and children. Some 25 men were able to escape. When the Spanish returned south and found the French shipwreck survivors, Menéndez de Avilés ordered all of the Huguenots executed. The location became known as '' Matanzas''. The 1565 marriage in St. Augustine between Luisa de Abrego, a free black domestic servant from Seville, and Miguel Rodríguez, a white Segovian conquistador, was the first known and recorded Christian marriage anywhere in what is now the continental United States. Following the expulsion of the French, the Spanish renamed Fort Caroline

M. A. Young, Gloria ''The Expedition of Hernando De Soto West of the Mississippi, 1541–1543''. University of Arkansas Press, 1999. p. 24. During the

Spanish Governor

Spanish Governor

In 1763, Spain traded Florida to Great Britain in exchange for control of

In 1763, Spain traded Florida to Great Britain in exchange for control of

Spain gained possession of West Florida and regained East Florida from Britain in the Peace of Paris of 1783, and continued the British practice of governing the Floridas as separate territories: West Florida and East Florida. When Spain acquired West Florida in 1783, the eastern British boundary was the Apalachicola River, but Spain in 1785 moved it eastward to the Suwannee River. The purpose was to transfer San Marcos and the district of Apalachee from East Florida to West Florida.

After American independence, the lack of specified boundaries led to a border dispute with the newly formed United States, known as the

Spain gained possession of West Florida and regained East Florida from Britain in the Peace of Paris of 1783, and continued the British practice of governing the Floridas as separate territories: West Florida and East Florida. When Spain acquired West Florida in 1783, the eastern British boundary was the Apalachicola River, but Spain in 1785 moved it eastward to the Suwannee River. The purpose was to transfer San Marcos and the district of Apalachee from East Florida to West Florida.

After American independence, the lack of specified boundaries led to a border dispute with the newly formed United States, known as the

Uwf.edu: Spanish Florida: Evolution of a Colonial Society, 1513–1763

{{Authority control Colonial United States (Spanish) New Spain Spanish Florida Former provinces of Spain Spanish Florida Spanish Florida Spanish Florida Spanish Florida Spanish colonization of the Americas States and territories established in 1565 1565 establishments in New Spain States and territories disestablished in 1763 1763 disestablishments in New Spain 1763 establishments in the British Empire States and territories established in 1783 1783 disestablishments in the British Empire 1783 establishments in New Spain States and territories disestablished in 1821 1821 disestablishments in New Spain 1821 establishments in the United States 1821 disestablishments in Mexico

Age of Discovery

The Age of Discovery (or the Age of Exploration), also known as the early modern period, was a period largely overlapping with the Age of Sail, approximately from the 15th century to the 17th century in European history, during which seafarin ...

. ''La Florida'' formed part of the Captaincy General of Cuba, the Viceroyalty of New Spain

New Spain, officially the Viceroyalty of New Spain ( es, Virreinato de Nueva España, ), or Kingdom of New Spain, was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established by Habsburg Spain during the Spanish colonization of the Amer ...

, and the Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire ( es, link=no, Imperio español), also known as the Hispanic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Hispánica) or the Catholic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Católica) was a colonial empire governed by Spain and its prede ...

during Spanish colonization of the Americas

Spain began colonizing the Americas under the Crown of Castile and was spearheaded by the Spanish . The Americas were invaded and incorporated into the Spanish Empire, with the exception of Brazil, British America, and some small regions ...

. While its boundaries were never clearly or formally defined, the territory was initially much larger than the present-day state of Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and to th ...

, extending over much of what is now the southeastern United States

The Southeastern United States, also referred to as the American Southeast or simply the Southeast, is a geographical region of the United States. It is located broadly on the eastern portion of the southern United States and the southern por ...

, including all of present-day Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and to ...

plus portions of Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

, Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = "Alabama (state song), Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery, Alabama, Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville, Alabama, Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County, Al ...

, Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...

, North Carolina

North Carolina () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the 28th largest and 9th-most populous of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, Georgia and So ...

, South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

, and Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

. Spain's claim to this vast area was based on several wide-ranging expeditions mounted during the 16th century. A number of missions, settlements, and small forts existed in the 16th and to a lesser extent in the 17th century; they were eventually abandoned due to pressure from the expanding English and French colonial settlements, the collapse of the native populations, and the general difficulty in becoming agriculturally or economically self-sufficient. By the 18th century, Spain's control over ''La Florida'' did not extend much beyond a handful of forts near St. Augustine, St. Marks, and Pensacola

Pensacola () is the westernmost city in the Florida Panhandle, and the county seat and only incorporated city of Escambia County, Florida, United States. As of the 2020 United States census, the population was 54,312. Pensacola is the principal ci ...

, all within the boundaries of present-day Florida.

Florida was never more than a backwater region for Spain and served primarily as a strategic buffer between New Spain

New Spain, officially the Viceroyalty of New Spain ( es, Virreinato de Nueva España, ), or Kingdom of New Spain, was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established by Habsburg Spain during the Spanish colonization of the Am ...

(whose undefined northeastern border was somewhere near the Mississippi River), Spain's Caribbean colonies, and the expanding English colonies to the north. In contrast with Mexico and Peru, there was no gold or silver to be found. Due to disease and, later, raids by Carolina colonists and their Native American allies, the native population was not large enough for an encomienda system of forced agricultural labor, so Spain did not establish large plantations in Florida. Large free-range cattle ranches in north-central Florida were the most successful agricultural enterprise and were able to supply both local and Cuban markets. The coastal towns of Pensacola and St. Augustine also provided ports where Spanish ships needing water or supplies could call.

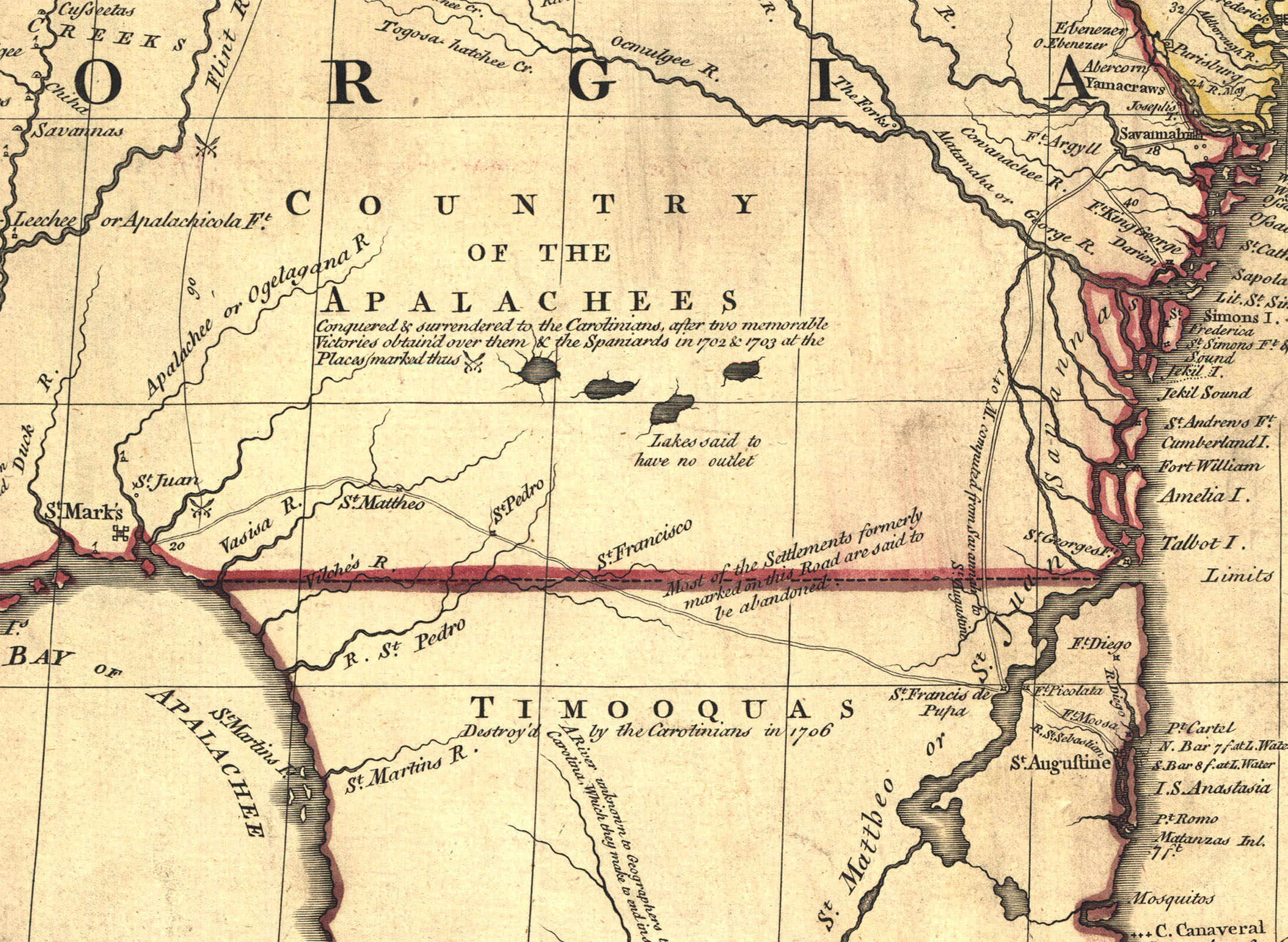

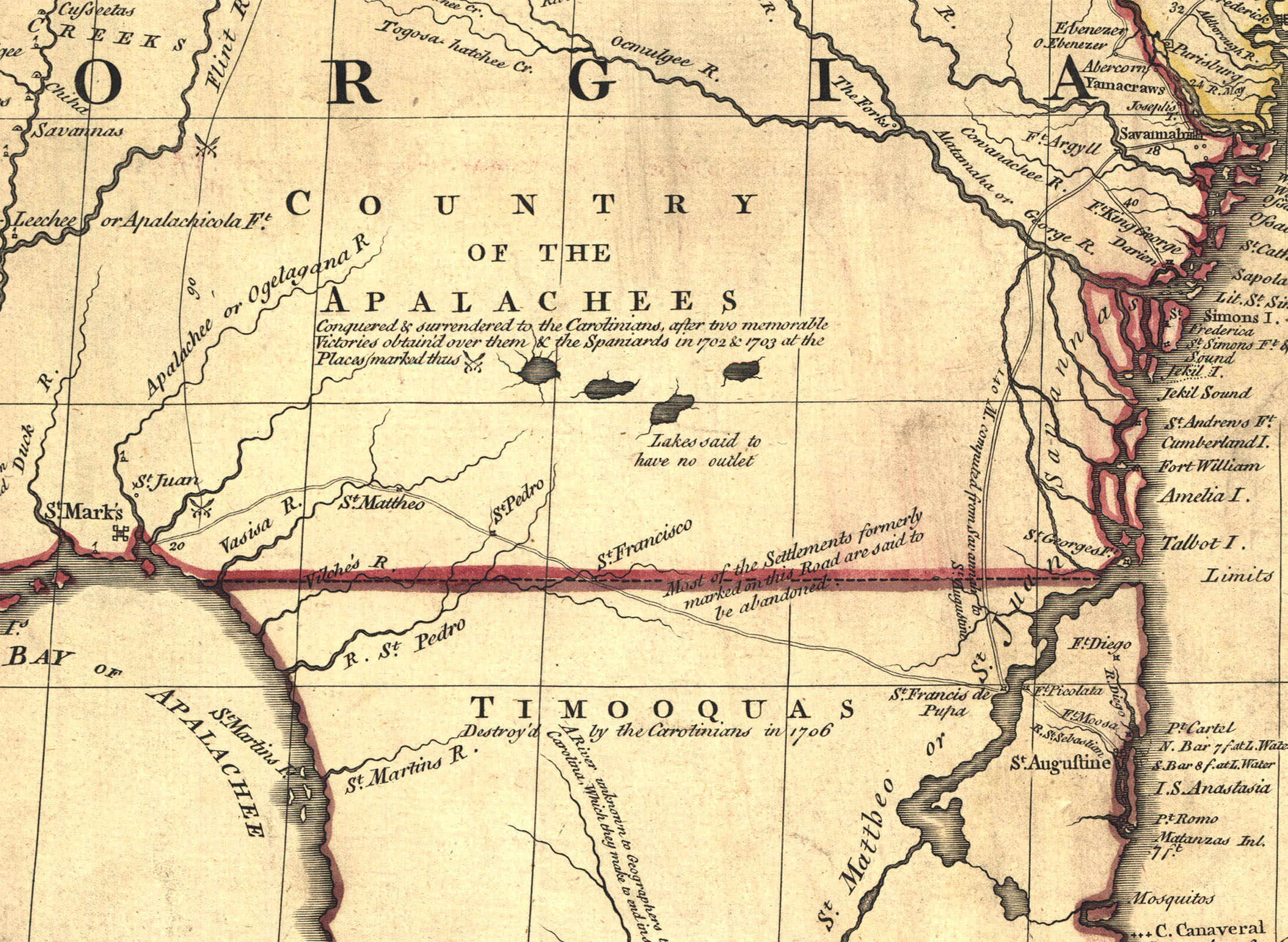

Beginning in the 1630s, a series of missions stretching from St. Augustine to the Florida panhandle supplied St. Augustine with maize

Maize ( ; ''Zea mays'' subsp. ''mays'', from es, maíz after tnq, mahiz), also known as corn (North American and Australian English), is a cereal grain first domesticated by indigenous peoples in southern Mexico about 10,000 years ago. Th ...

and other food crops, and the Apalachee

The Apalachee were an Indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands, specifically an Indigenous people of Florida, who lived in the Florida Panhandle until the early 18th century. They lived between the Aucilla River and Ochlockonee River,B ...

s who lived at the missions were required to send workers to St. Augustine every year to perform labor in the town. The missions were destroyed by Carolina and Creek raiders in a series of raids from 1702 to 1704, further reducing and dispersing the native population of Florida and reducing Spanish control over the area.

Britain took possession of Florida as part of the agreements ending the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754� ...

in 1763, and the Spanish population largely emigrated to Cuba. The new colonial ruler divided the territory into East and West Florida, but despite offers of free land to new settlers, Britain was unable to increase the population or economic output, and traded Florida back to Spain after the American War of Independence in 1783. Spain's ability to govern or control the colony continued to erode, and, after repeated incursions by American forces against the Seminole

The Seminole are a Native American people who developed in Florida in the 18th century. Today, they live in Oklahoma and Florida, and comprise three federally recognized tribes: the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, the Seminole Tribe of Florida, an ...

people who had settled in Florida, Spain finally decided to sell the territory to the United States. The parties signed the Adams-Onis Treaty in 1819, and the transfer officially took place on July 17, 1821, over 300 years after Spain had first claimed the Florida peninsula.

Establishment of Spanish Florida

Spanish Florida was established in 1513, when Juan Ponce de León claimed peninsular Florida for Spain during the first official European expedition to North America. This claim was enlarged as several explorers (most notably Pánfilo Narváez and Hernando de Soto) landed near

Spanish Florida was established in 1513, when Juan Ponce de León claimed peninsular Florida for Spain during the first official European expedition to North America. This claim was enlarged as several explorers (most notably Pánfilo Narváez and Hernando de Soto) landed near Tampa Bay

Tampa Bay is a large natural harbor and shallow estuary connected to the Gulf of Mexico on the west-central coast of Florida, comprising Hillsborough Bay, McKay Bay, Old Tampa Bay, Middle Tampa Bay, and Lower Tampa Bay. The largest freshwater ...

in the mid-1500s and wandered as far north as the Appalachian Mountains

The Appalachian Mountains, often called the Appalachians, (french: Appalaches), are a system of mountains in eastern to northeastern North America. The Appalachians first formed roughly 480 million years ago during the Ordovician Period. They ...

and as far west as Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish language, Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2 ...

in largely unsuccessful searches for gold. The presidio

A presidio ( en, jail, fortification) was a fortified base established by the Spanish Empire around between 16th and 18th centuries in areas in condition of their control or influence. The presidios of Spanish Philippines in particular, were cen ...

of St. Augustine was founded on Florida's Atlantic coast in 1565; a series of missions were established across the Florida panhandle

The Florida Panhandle (also West Florida and Northwest Florida) is the northwestern part of the U.S. state of Florida; it is a Salient (geography), salient roughly long and wide, lying between Alabama on the north and the west, Georgia (U. ...

, Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

, and South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

during the 1600s; and Pensacola

Pensacola () is the westernmost city in the Florida Panhandle, and the county seat and only incorporated city of Escambia County, Florida, United States. As of the 2020 United States census, the population was 54,312. Pensacola is the principal ci ...

was founded on the western Florida panhandle in 1698, strengthening Spanish claims to that section of the territory.

Spanish control of the Florida peninsula was much facilitated by the collapse of native cultures during the 17th century. Several Native American groups (including the Timucua

The Timucua were a Native American people who lived in Northeast and North Central Florida and southeast Georgia. They were the largest indigenous group in that area and consisted of about 35 chiefdoms, many leading thousands of people. The v ...

, Calusa, Tequesta

The Tequesta (also Tekesta, Tegesta, Chequesta, Vizcaynos) were a Native American tribe. At the time of first European contact they occupied an area along the southeastern Atlantic coast of Florida. They had infrequent contact with Europeans a ...

, Apalachee

The Apalachee were an Indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands, specifically an Indigenous people of Florida, who lived in the Florida Panhandle until the early 18th century. They lived between the Aucilla River and Ochlockonee River,B ...

, Tocobaga

Tocobaga (occasionally Tocopaca) was the name of a chiefdom, its chief, and its principal town during the 16th century. The chiefdom was centered around the northern end of Old Tampa Bay, the arm of Tampa Bay that extends between the present-da ...

, and the Ais people

The Ais or Ays were a Native American people of eastern Florida. Their territory included coastal areas and islands from approximately Cape Canaveral to the Indian River. The Ais chiefdom consisted of a number of towns, each led by a chief who ...

) had been long-established residents of Florida, and most resisted Spanish incursions onto their land. However, conflict with Spanish expeditions, raids by the Carolina colonists and their native allies, and (especially) diseases brought from Europe resulted in a drastic decline in the population of all the indigenous peoples of Florida

The indigenous peoples of Florida lived in what is now known as Florida for more than 12,000 years before the time of first contact with Europeans. However, the indigenous Floridians living east of the Apalachicola River had largely died out by ...

, and large swaths of the peninsula were mostly uninhabited by the early 1700s. During the mid-1700s, small bands of Creek and other Native American refugees began moving south into Spanish Florida after having been forced off their lands by South Carolinan settlements and raids. They were later joined by African-Americans

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of enslav ...

fleeing slavery in nearby colonies. These newcomers – plus perhaps a few surviving descendants of indigenous Florida peoples – eventually coalesced into a new Seminole

The Seminole are a Native American people who developed in Florida in the 18th century. Today, they live in Oklahoma and Florida, and comprise three federally recognized tribes: the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, the Seminole Tribe of Florida, an ...

culture.

Contraction of Spanish Florida

The extent of Spanish Florida began to shrink in the 1600s, and the mission system was gradually abandoned due to native depopulation. Between disease, poor management, and ill-timed hurricanes, several Spanish attempts to establish new settlements in ''La Florida'' ended in failure. With no gold or silver in the region, Spain regarded Florida (and particularly the heavily fortified town of St. Augustine) primarily as a buffer between its more prosperous colonies to the south and west and several newly established rival European colonies to the north. The establishment of theProvince of Carolina

Province of Carolina was a province of England (1663–1707) and Great Britain (1707–1712) that existed in North America and the Caribbean from 1663 until partitioned into North and South on January 24, 1712. It is part of present-day Alaba ...

by the English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

in 1639, New Orleans

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

by the French in 1718, and of the Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

Province of Georgia

A province is almost always an administrative division within a country or state. The term derives from the ancient Roman ''provincia'', which was the major territorial and administrative unit of the Roman Empire's territorial possessions out ...

by Great Britain in 1732 limited the boundaries of Florida over Spanish objections. The War of Jenkins' Ear

The War of Jenkins' Ear, or , was a conflict lasting from 1739 to 1748 between Britain and the Spanish Empire. The majority of the fighting took place in New Granada and the Caribbean Sea, with major operations largely ended by 1742. It is con ...

(1739–1748) included a British attack on St. Augustine and a Spanish invasion of Georgia

In the 1742 Invasion of Georgia, Spanish forces based in Florida attempted to seize and occupy disputed territory held by the British colony of Georgia. The campaign was part of a larger conflict which became known as the War of Jenkins' Ear. ...

, both of which were repulsed. At the conclusion of the war, the northern boundary of Spanish Florida was set near the current northern border of modern-day Florida.

Other European powers

Great Britain temporarily gained control of Florida beginning in 1763 as a result of the Anglo-Spanish War when the British captured Havana, the principal port of Spain's New World colonies. Peace was signed in February, 1763, and the British left Cuba in July that year, having traded Cuba to Spain for Florida (the Spanish population of Florida likewise traded positions and emigrated to the island). But while Britain occupied Floridan territory, it did not develop it further. Sparsely populated British Florida stayed loyal tothe Crown

The Crown is the state in all its aspects within the jurisprudence of the Commonwealth realms and their subdivisions (such as the Crown Dependencies, overseas territories, provinces, or states). Legally ill-defined, the term has different ...

during the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

, and by the terms of the Treaty of Paris Treaty of Paris may refer to one of many treaties signed in Paris, France:

Treaties

1200s and 1300s

* Treaty of Paris (1229), which ended the Albigensian Crusade

* Treaty of Paris (1259), between Henry III of England and Louis IX of France

* Trea ...

which ended the war, the territory was returned to Spain in 1783. After a brief diplomatic border dispute with the fledgling United States, the countries set a territorial border and allowed Americans free navigation of the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

by the terms of Pinckney's Treaty

Pinckney's Treaty, also known as the Treaty of San Lorenzo or the Treaty of Madrid, was signed on October 27, 1795 by the United States and Spain.

It defined the border between the United States and Spanish Florida, and guaranteed the United S ...

in 1795.

France sold Louisiana to the United States in 1803. The U.S. claimed that the transaction included West Florida

West Florida ( es, Florida Occidental) was a region on the northern coast of the Gulf of Mexico that underwent several boundary and sovereignty changes during its history. As its name suggests, it was formed out of the western part of former S ...

, while Spain insisted that the area was not part of Louisiana and was still Spanish territory. In 1810, the United States intervened in a local uprising in West Florida, and by 1812, the Mobile District

The Mobile District was an administrative division of the Spanish colony of West Florida, which was claimed by the short-lived Republic of West Florida, established on September 23, 1810. Reuben Kemper led a small force in an attempt to capture M ...

was absorbed into the U.S. territory of Mississippi

The Territory of Mississippi was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from April 7, 1798, until December 10, 1817, when the western half of the territory was admitted to the United States, Union as the History o ...

, reducing the borders of Spanish Florida to that of modern Florida.

In the early 1800s, tensions rose along the unguarded border between Spanish Florida and the state of Georgia as settlers skirmished with Seminoles over land and American slave-hunters raided Black Seminole

The Black Seminoles, or Afro-Seminoles are Native American-Africans associated with the Seminole people in Florida and Oklahoma. They are mostly blood descendants of the Seminole people, free Africans, and escaped slaves, who allied with Seminol ...

villages in Florida. These tensions were exacerbated when the Seminoles aided Great Britain against the United States during the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It bega ...

and led to American military incursions into northern Florida beginning in late 1814 during what became known as the First Seminole War

The Seminole Wars (also known as the Florida Wars) were three related military conflicts in Florida between the United States and the Seminole, citizens of a Native American nation which formed in the region during the early 1700s. Hostilities ...

. As with earlier American incursions into Florida, Spain protested this invasion but could not defend its territory, and instead opened diplomatic negotiations seeking a peaceful transfer of land. By the terms of the Adams–Onís Treaty

The Adams–Onís Treaty () of 1819, also known as the Transcontinental Treaty, the Florida Purchase Treaty, or the Florida Treaty,Weeks, p.168. was a treaty between the United States and Spain in 1819 that ceded Florida to the U.S. and defined t ...

of 1819, Spanish Florida ceased to exist in 1821, when control of the territory was officially transferred to the United States.

Discovery and early exploration

European discovery

Juan Ponce de León is generally credited as being the first European to discover Florida. However, that may not have been the case. Spanish raiders from the Caribbean may have conducted small secret raids in Florida to capture and enslave native Floridians at some time between 1500 and 1510. Furthermore, the PortugueseCantino planisphere

The Cantino planisphere or Cantino world map is a manuscript Portuguese world map preserved at the Biblioteca Estense in Modena, Italy. It is named after Alberto Cantino, an agent for the Duke of Ferrara, who successfully smuggled it from Portu ...

of 1502 and several other European maps dating from the first decade of the 16th century show a landmass near Cuba that several historians have identified as Florida. This interpretation has led to the theory that anonymous Portuguese explorers

Portuguese maritime exploration resulted in the numerous territories and maritime routes recorded by the Portuguese as a result of their intensive maritime journeys during the 15th and 16th centuries. Portuguese sailors were at the vanguard of Eu ...

were the first Europeans to map the southeastern portion of the future United States, including Florida. This view is disputed by at least an equal number of historians.

Juan Ponce de León Expedition

In 1512 Juan Ponce de León, governor of

In 1512 Juan Ponce de León, governor of Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico (; abbreviated PR; tnq, Boriken, ''Borinquen''), officially the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico ( es, link=yes, Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico, lit=Free Associated State of Puerto Rico), is a Caribbean island and Unincorporated ...

, received royal permission to search for land north of Cuba. On March 3, 1513, his expedition departed from Punta Aguada, Puerto Rico, sailing north in three ships. In late March, he spotted a small island (almost certainly one of the Bahamas

The Bahamas (), officially the Commonwealth of The Bahamas, is an island country within the Lucayan Archipelago of the West Indies in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic. It takes up 97% of the Lucayan Archipelago's land area and is home to ...

) but did not land. On April 2, Ponce de León spotted the east coast of the Florida peninsula and went ashore the next day at an exact location that has been lost to time. Assuming that he had found a large island, he claimed the land for Spain and named it ''La Florida'', because it was the season of '' Pascua Florida'' ("Flowery Easter") and because much of the vegetation was in bloom. After briefly exploring the area around their landing site, the expedition returned to their ships and sailed south to map the coast, encountering the Gulf Stream along the way. The expedition followed Florida's coastline all the way around the Florida Keys and north to map a portion of the Southwest Florida

Southwest Florida is the region along the southwest Gulf coast of the U.S. state of Florida. The area is known for its beaches, subtropical landscape, and winter resort economy.

Definitions of the region vary, though its boundaries are generally ...

coast before returning to Puerto Rico.

Ponce de León did not have substantial documented interactions with Native Americans during his voyage. However, the peoples he met (likely the Timucua

The Timucua were a Native American people who lived in Northeast and North Central Florida and southeast Georgia. They were the largest indigenous group in that area and consisted of about 35 chiefdoms, many leading thousands of people. The v ...

, Tequesta

The Tequesta (also Tekesta, Tegesta, Chequesta, Vizcaynos) were a Native American tribe. At the time of first European contact they occupied an area along the southeastern Atlantic coast of Florida. They had infrequent contact with Europeans a ...

, and Calusa) were mostly hostile at first contact and knew a few Castilian words, lending credence to the idea that they had already been visited by Spanish raiders.

Popular legend has it that Ponce de León was searching for the Fountain of Youth

The Fountain of Youth is a mythical spring which allegedly restores the youth of anyone who drinks or bathes in its waters. Tales of such a fountain have been recounted around the world for thousands of years, appearing in the writings of Herod ...

when he discovered Florida. However, the first mention of Ponce de León allegedly searching for water to cure his aging (he was only 40) came after his death, more than twenty years after his voyage of discovery, and the first that placed the Fountain of Youth in Florida was thirty years after that. It is much more likely that Ponce de León, like other Spanish conquistador

Conquistadors (, ) or conquistadores (, ; meaning 'conquerors') were the explorer-soldiers of the Spanish and Portuguese Empires of the 15th and 16th centuries. During the Age of Discovery, conquistadors sailed beyond Europe to the Americas, O ...

s in the Americas

The Americas, which are sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North and South America. The Americas make up most of the land in Earth's Western Hemisphere and comprise the New World.

Along with th ...

, was looking for gold, land to colonize and rule for Spain, and Indians to convert to Christianity or enslave.

Other early expeditions

Other Spanish voyages to Florida quickly followed Ponce de León's return. Sometime in the period from 1514 to 1516, Pedro de Salazar led an officially sanctioned raid which enslaved as many as 500 Indians along the Atlantic coast of the present-day southeastern United States. Diego Miruelo mapped what was probablyTampa Bay

Tampa Bay is a large natural harbor and shallow estuary connected to the Gulf of Mexico on the west-central coast of Florida, comprising Hillsborough Bay, McKay Bay, Old Tampa Bay, Middle Tampa Bay, and Lower Tampa Bay. The largest freshwater ...

in 1516, Francisco Hernández de Cordova mapped most of Florida's Gulf coast to the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

in 1517, and Alonso Álvarez de Pineda

Alonso Álvarez de Piñeda (; 1494–1520) was a Spanish conquistador and cartographer who was the first to prove the insularity of the Gulf of Mexico by sailing around its coast. In doing so he created the first map to depict what is now Texas an ...

sailed and mapped the central and western Gulf coast to the Yucatán Peninsula

The Yucatán Peninsula (, also , ; es, Península de Yucatán ) is a large peninsula in southeastern Mexico and adjacent portions of Belize and Guatemala. The peninsula extends towards the northeast, separating the Gulf of Mexico to the north ...

in 1519.

First colonization attempts

In 1521, Ponce de León sailed from Cuba with 200 men in two ships to establish a colony on the southwest coast of the Florida peninsula, probably near Charlotte Harbor. However, attacks by the native Calusa drove the colonists away in July 1521. During the skirmish, Ponce de León was wounded in his thigh and later died of his injuries upon the expedition's return toHavana

Havana (; Spanish: ''La Habana'' ) is the capital and largest city of Cuba. The heart of the La Habana Province, Havana is the country's main port and commercial center.

.

In 1521 Pedro de Quejo and Francisco Gordillo enslaved 60 Indians at Winyah Bay

The Winyaw were a Native American tribe living near Winyah Bay, Black River, and the lower course of the Pee Dee River in South Carolina. The Winyaw people disappeared as a distinct entity after 1720 and are thought to have merged with the Wacc ...

, South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

. Quejo, with the backing of Lucas Vázquez de Ayllón

Lucas Vázquez de Ayllón (c. 1480 – 18 October 1526) was a Spanish magistrate and explorer who in 1526 established the short-lived San Miguel de Gualdape colony, one of the first European attempts at a settlement in what is now the United State ...

, returned to the region in 1525, stopping at several locations between Amelia Island

Amelia Island is a part of the Sea Islands chain that stretches along the East Coast of the United States from South Carolina to Florida; it is the southernmost of the Sea Islands, and the northernmost of the barrier islands on Florida's Atlanti ...

and the Chesapeake Bay

The Chesapeake Bay ( ) is the largest estuary in the United States. The Bay is located in the Mid-Atlantic region and is primarily separated from the Atlantic Ocean by the Delmarva Peninsula (including the parts: the Eastern Shore of Maryland / ...

. In 1526 de Ayllón led an expedition of some 600 people to the South Carolina coast. After scouting possible locations as far south as Ponce de Leon Inlet

The Ponce de Leon Inlet is a natural opening in the barrier islands in central Florida that connects the north end of the Mosquito Lagoon and the south end of the Halifax River to the Atlantic Ocean. The inlet originally was named Mosquito Inlet. ...

in Florida, the settlement of San Miguel de Gualdape

San Miguel de Gualdape (sometimes San Miguel de Guadalupe) is a former Spanish colony in present-day Georgetown County, South Carolina, founded in 1526 by Lucas Vázquez de Ayllón.In early 1521, Ponce de León had made a poorly documented, disas ...

was established in the vicinity of Sapelo Sound, Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

. Disease, hunger, cold and Indian attacks led to San Miguel being abandoned after only two months. About 150 survivors returned to Spanish settlements. Dominican friars Fr. Antonio de Montesinos and Fr. Anthony de Cervantes were among the colonists. Given that at the time priests were obliged to say mass each day, it is historically safe to assert that Catholic Mass was celebrated in what is today the United States for the first time by these Dominicans, even though the specific date and location remains unclear.

Narváez expedition

In 1527Pánfilo de Narváez

Pánfilo de Narváez (; 147?–1528) was a Spanish '' conquistador'' and soldier in the Americas. Born in Spain, he first embarked to Jamaica in 1510 as a soldier. He came to participate in the conquest of Cuba and led an expedition to Camagü ...

left Spain with five ships and about 600 people (including the Moroccan slave Mustafa Azemmouri) on a mission to explore and to settle the coast of the Gulf of Mexico between the existing Spanish settlements in Mexico and Florida. After storms and delays, the expedition landed near Tampa Bay on April 12, 1528, already short on supplies, with about 400 people. Confused as to the location of Tampa Bay (Milanich notes that a navigation guide used by Spanish pilots

An aircraft pilot or aviator is a person who controls the flight of an aircraft by operating its directional flight controls. Some other aircrew members, such as navigators or flight engineers, are also considered aviators, because they a ...

at the time placed Tampa Bay some 90 miles too far north), Narváez sent his ships in search of it while most of the expedition marched northward, supposedly to meet the ships at the bay.

Intending to find Tampa Bay, Narváez marched close to the coast, through what turned out to be a largely uninhabited territory. The expedition was forced to subsist on the rations they had brought with them until they reached the Withlacoochee River, where they finally encountered Indians. Seizing hostages, the expedition reached the Indians' village, where they found corn. Further north they were met by a chief who led them to his village on the far side of the Suwannee River. The chief, Dulchanchellin, tried to enlist the Spanish as allies against his enemies, the Apalachee

The Apalachee were an Indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands, specifically an Indigenous people of Florida, who lived in the Florida Panhandle until the early 18th century. They lived between the Aucilla River and Ochlockonee River,B ...

.

Seizing Indians as guides, the Spaniards traveled northwest towards the Apalachee territory. Milanich suggests that the guides led the Spanish on a circuitous route through the roughest country they could find. In any case, the expedition did not find the larger Apalachee towns. By the time the expedition reached Aute, a town near the Gulf Coast, it had been under attack by Indian archers for many days. Plagued by illness, short rations, and hostile Indians, Narváez decided to sail to Mexico rather than attempt an overland march. Two hundred and forty-two men set sail on five crude rafts. All the rafts were wrecked on the Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish language, Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2 ...

coast. After eight years, four survivors, including Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca

Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca (; 1488/90/92"Cabeza de Vaca, Alvar Núñez (1492?-1559?)." American Eras. Vol. 1: Early American Civilizations and Exploration to 1600. Detroit: Gale, 1997. 50-51. Gale Virtual Reference Library. Web. 10 Decembe ...

, reached New Spain (Mexico).

De Soto expedition

Hernando de Soto had been one ofFrancisco Pizarro

Francisco Pizarro González, Marquess of the Atabillos (; ; – 26 June 1541) was a Spanish conquistador, best known for his expeditions that led to the Spanish conquest of Peru.

Born in Trujillo, Spain to a poor family, Pizarro chose ...

's chief lieutenants in the Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire

The Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire, also known as the Conquest of Peru, was one of the most important campaigns in the Spanish colonization of the Americas. After years of preliminary exploration and military skirmishes, 168 Spanish sol ...

, and had returned to Spain a very wealthy man. He was appointed ''Adelantado'' of Florida and governor of Cuba and assembled a large expedition to 'conquer' Florida. On May 30, 1539, de Soto and his companions landed in Tampa Bay, where they found Juan Ortiz, who had been captured by the local Indians a decade earlier when he was sent ashore from a ship searching for Narváez. Ortiz passed on the Indian reports of riches, including gold, to be found in Apalachee, and de Soto set off with 550 soldiers, 200 horses, and a few priests and friars. De Soto's expedition lived off the land as it marched. De Soto followed a route further inland than that of Narváez's expedition, but the Indians remembered the earlier disruptions caused by the Spanish and were wary when not outright hostile. De Soto seized Indians to serve as guides and porters.

The expedition reached Apalachee in October and settled into the chief Apalachee town of Anhaica

Anhaica (also known as Iviahica, Yniahico, and pueblo of Apalache) was the principal town of the Apalachee people, located in what is now Tallahassee, Florida. In the early period of Spanish colonization, it was the capital of the Apalachee Provi ...

for the winter, where they found large quantities of stored food, but little gold or other riches. In the spring de Soto set out to the northeast, crossing what is now Georgia and South Carolina into North Carolina

North Carolina () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the 28th largest and 9th-most populous of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, Georgia and So ...

, then turned westward, crossed the Great Smoky Mountains

The Great Smoky Mountains (, ''Equa Dutsusdu Dodalv'') are a mountain range rising along the Tennessee–North Carolina border in the southeastern United States. They are a subrange of the Appalachian Mountains, and form part of the Blue Ridge ...

into Tennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked state in the Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the 36th-largest by area and the 15th-most populous of the 50 states. It is bordered by Kentucky to th ...

, then marched south into Georgia. Turning westward again, the expedition crossed Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = "Alabama (state song), Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery, Alabama, Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville, Alabama, Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County, Al ...

. They lost all of their baggage in a fight with Indians near Choctaw Bluff on the Alabama River, and spent the winter in Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...

. In May 1541 the expedition crossed the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

and wandered through present-day Arkansas

Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the South Central United States. It is bordered by Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, and Texas and Oklahoma to the west. Its name is from the Osage ...

, Missouri

Missouri is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee ...

and possibly Kansas

Kansas () is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its capital is Topeka, and its largest city is Wichita. Kansas is a landlocked state bordered by Nebraska to the north; Missouri to the east; Oklahoma to the south; and Colorado to the ...

before spending the winter in Oklahoma

Oklahoma (; Choctaw language, Choctaw: ; chr, ᎣᎧᎳᎰᎹ, ''Okalahoma'' ) is a U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States, bordered by Texas on the south and west, Kansas on the nor ...

. In 1542 the expedition headed back to the Mississippi River, where de Soto died. Three hundred and ten survivors returned from the expedition in 1543.

Ochuse and Santa Elena

Although the Spanish had lost hope of finding gold and other riches in Florida, it was seen as vital to the defense of their colonies and territories in Mexico and the Caribbean. In 1559Tristán de Luna y Arellano

Tristán de Luna y Arellano (1510 – September 16, 1573) was a Spanish explorer and Conquistador of the 16th century.Herbert Ingram Priestley, Tristan de Luna: Conquistador of the Old South: A Study of Spanish Imperial Strategy (1936). http://palm ...

left Mexico with 500 soldiers and 1,000 civilians on a mission to establish colonies at Ochuse (Pensacola Bay

Pensacola Bay is a bay located in the northwestern part of Florida, United States, known as the Florida Panhandle.

The bay, an inlet of the Gulf of Mexico, is located in Escambia County and Santa Rosa County, adjacent to the city of Pensacola ...

) and Santa Elena (Port Royal Sound Port Royal Sound is a coastal sound, or inlet of the Atlantic Ocean, located in the Sea Islands region, in Beaufort County in the U.S. state of South Carolina. It is the estuary of several rivers, the largest of which is the Broad River.

Geograp ...

). The plan was to land everybody at Ochuse, with most of the colonists marching overland to Santa Elena. A tropical storm struck five days after the fleet's arrival at the Bay of Ochuse, sinking ten of the thirteen ships along with the supplies that had not yet been unloaded. Expeditions into the interior failed to find adequate supplies of food. Most of the colony moved inland to Nanicapana, renamed Santa Cruz, where some food had been found, but it could not support the colony and the Spanish returned to Pensacola Bay. In response to a royal order to immediately occupy Santa Elena, Luna sent three small ships, but they were damaged in a storm and returned to Mexico. Angel de Villafañe replaced the discredited Luna in 1561, with orders to withdraw most of the colonists from Ochuse and occupy Santa Elena. Villafañe led 75 men to Santa Elena, but a tropical storm damaged his ships before they could land, forcing the expedition to return to Mexico.

Settlement and fortification

The establishment of permanent settlements and fortifications in Florida bySpain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

was in response to the challenge posed by French Florida

French Florida (Renaissance French: ''Floride françoise''; modern French: ''Floride française'') was a colonial territory established by French Huguenot colonists as part of New France in what is now Florida and South Carolina between 1562 and ...

: French captain Jean Ribault

Jean Ribault (also spelled ''Ribaut'') (1520 – October 12, 1565) was a French naval officer, navigator, and a colonizer of what would become the southeastern United States. He was a major figure in the French attempts to colonize Florida. A H ...

led an expedition to Florida, and established Charlesfort

The Charlesfort-Santa Elena Site is an important early colonial archaeological site on Parris Island, South Carolina. It contains the archaeological remains of a French settlement called Charlesfort, settled in 1562 and abandoned the following y ...

on what is now Parris Island, South Carolina

Parris Island is a district of the city of Port Royal, South Carolina on an island of the same name. It became part of the city with the annexation of the Marine Corps Recruit Depot Parris Island on October 11, 2002. For statistical purposes, th ...

, in 1562. However, the French Wars of Religion

The French Wars of Religion is the term which is used in reference to a period of civil war between French Catholics and Protestants, commonly called Huguenots, which lasted from 1562 to 1598. According to estimates, between two and four mi ...

prevented Ribault from returning to resupply the fort, and the men abandoned it. Two years later, René Goulaine de Laudonnière

Rene Goulaine de Laudonnière (c. 1529–1574) was a French Huguenot explorer and the founder of the French colony of Fort Caroline in what is now Jacksonville, Florida. Admiral Gaspard de Coligny, a Huguenot, sent Jean Ribault and Laudonnière ...

, Ribault's lieutenant on the previous voyage, set out to found a haven for Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , also , ) were a religious group of French Protestants who held to the Reformed, or Calvinist, tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, the Genevan burgomaster Be ...

colonists in Florida. He founded Fort Caroline

Fort Caroline was an attempted French colonial settlement in Florida, located on the banks of the St. Johns River in present-day Duval County. It was established under the leadership of René Goulaine de Laudonnière on 22 June, 1564, follow ...

at what is now Jacksonville

Jacksonville is a city located on the Atlantic coast of northeast Florida, the most populous city proper in the state and is the List of United States cities by area, largest city by area in the contiguous United States as of 2020. It is the co ...

in July 1564. Once again, however, a resupplying mission by Ribault failed to arrive, threatening the colony. Some mutineers fled Fort Caroline to engage in piracy

Piracy is an act of robbery or criminal violence by ship or boat-borne attackers upon another ship or a coastal area, typically with the goal of stealing cargo and other valuable goods. Those who conduct acts of piracy are called pirates, v ...

against Spanish colonies, causing alarm among the Spanish government. Laudonnière nearly abandoned the colony in 1565, but Jean Ribault finally arrived with supplies and new settlers in August.

At the same time, in response to French activities, King Philip II of Spain appointed Pedro Menéndez de Avilés ''Adelantado

''Adelantado'' (, , ; meaning "advanced") was a title held by Spanish nobles in service of their respective kings during the Middle Ages. It was later used as a military title held by some Spanish ''conquistadores'' of the 15th, 16th and 17th cen ...

'' of Florida, with a commission to drive non-Spanish adventurers from all of the land from Newfoundland to St. Joseph Bay

St. Joseph Bay is a bay on the Gulf Coast of the U.S. state of Florida. The bay is located in Gulf County between Apalachicola and Panama City. Port St. Joe is located on St. Joseph Bay.

St. Joseph Bay is bounded on the east by the mainland, o ...

(on the north coast of the Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico ( es, Golfo de México) is an oceanic basin, ocean basin and a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean, largely surrounded by the North American continent. It is bounded on the northeast, north and northwest by the Gulf Coast of ...

). Menéndez de Avilés reached Florida at the same time as Ribault in 1565, and established a base at San Agustín (St. Augustine in English), the oldest continuously inhabited European-established settlement in what is now the continental United States.National Historic Landmarks Program – St. Augustine Town Plan Historic DistrictMenéndez de Avilés quickly set out to attack Fort Caroline, traveling overland from St. Augustine. At the same time, Ribault sailed from Fort Caroline, intending to attack St. Augustine from the sea. The French fleet, however, was pushed out to sea and decimated by a squall. Meanwhile, the Spanish overwhelmed the lightly defended Fort Caroline, sparing only the women and children. Some 25 men were able to escape. When the Spanish returned south and found the French shipwreck survivors, Menéndez de Avilés ordered all of the Huguenots executed. The location became known as '' Matanzas''. The 1565 marriage in St. Augustine between Luisa de Abrego, a free black domestic servant from Seville, and Miguel Rodríguez, a white Segovian conquistador, was the first known and recorded Christian marriage anywhere in what is now the continental United States. Following the expulsion of the French, the Spanish renamed Fort Caroline

Fort San Mateo

Fort Caroline was an attempted French colonial settlement in Florida, located on the banks of the St. Johns River in present-day Duval County. It was established under the leadership of René Goulaine de Laudonnière on 22 June, 1564, follow ...

(''Saint Matthew''). Two years later, Dominique de Gourgues

Dominique (or Domingue) de Gourgues (1530–1593) was a French nobleman and soldier. He is best known for leading an attack against Spanish Florida in 1568, in response to the destruction of the French Fort Caroline. He was a captain in King Cha ...

recaptured the fort from the Spanish and slaughtered all of the Spanish defenders. However, he did not leave a garrison, and France would not attempt to settle in Florida again.

To fortify St. Augustine, Spaniards (along with forced labor from the Timucuan, Guale, and Apalache peoples) built the Castillo de San Marcos beginning in 1672. The first stage of construction was completed in 1695. They also built Fort Matanzas just to the south to look for enemies arriving by sea. In the eighteenth century, a free black population began to grow in St. Augustine, as Spanish Florida granted freedom to enslaved people fleeing the Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, also known as the Thirteen British Colonies, the Thirteen American Colonies, or later as the United Colonies, were a group of Kingdom of Great Britain, British Colony, colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. Fo ...

. Fort Mose

Fort Mose Historic State Park (originally known as Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mose, and later Fort Mose; alternatively, Fort Moosa or Fort Mossa), is a former Spanish fort in St. Augustine, Florida. In 1738, the governor of Spanish Florida, M ...

became another fort, populated by free black militiamen and their families, serving as a buffer between the Spanish and British.

Missions and conflicts

In 1549, Father Luis de Cáncer and three other Dominicans attempted the first solely missionary expedition in la Florida. Following decades of native contact with Spanish laymen who had ignored a 1537 Papal Bull which condemned slavery in no uncertain terms, the religious order's effort was abandoned after only 6 weeks with de Cancer's brutal martyrdom byTocobaga

Tocobaga (occasionally Tocopaca) was the name of a chiefdom, its chief, and its principal town during the 16th century. The chiefdom was centered around the northern end of Old Tampa Bay, the arm of Tampa Bay that extends between the present-da ...

natives. His death sent shock waves through the Dominican missionary community in New Spain

New Spain, officially the Viceroyalty of New Spain ( es, Virreinato de Nueva España, ), or Kingdom of New Spain, was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established by Habsburg Spain during the Spanish colonization of the Am ...

for many years.

In 1566, the Spanish established the colony of Santa Elena on what is now Parris Island, South Carolina

Parris Island is a district of the city of Port Royal, South Carolina on an island of the same name. It became part of the city with the annexation of the Marine Corps Recruit Depot Parris Island on October 11, 2002. For statistical purposes, th ...

. Juan Pardo led two expeditions (1566-1567 and 1567–1568) from Santa Elena as far as eastern Tennessee, establishing six temporary forts in interior. The Spanish abandoned Santa Elena and the surrounding area in 1587.

In 1586, English privateer

A privateer is a private person or ship that engages in maritime warfare under a commission of war. Since robbery under arms was a common aspect of seaborne trade, until the early 19th century all merchant ships carried arms. A sovereign or deleg ...

Francis Drake plundered and burned St. Augustine, including a fortification that was under construction, while returning from raiding Santo Domingo

, total_type = Total

, population_density_km2 = auto

, timezone = AST (UTC −4)

, area_code_type = Area codes

, area_code = 809, 829, 849

, postal_code_type = Postal codes

, postal_code = 10100–10699 ( Distrito Nacional)

, webs ...

and Cartagena in the Caribbean.A. Burkholder, Mark; L. Johnson, Lyman ''Colonial Latin America''. Oxford University Press, 1990. p. 145. His raids exposed Spain's inability to properly defend her settlements.

The Jesuits

The Society of Jesus ( la, Societas Iesu; abbreviation: SJ), also known as the Jesuits (; la, Iesuitæ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

had begun establishing missions to the Native Americans in Florida in 1567, but withdrew in 1572 after hostile encounters with the natives.M. McAlister, Lyle ''Spain and Portugal in the New World, 1492–1700''. University of Minnesota Press, 1984. In 1573 Franciscan

The Franciscans are a group of related Mendicant orders, mendicant Christianity, Christian Catholic religious order, religious orders within the Catholic Church. Founded in 1209 by Italian Catholic friar Francis of Assisi, these orders include t ...

s assumed responsibility for missions to the Native Americans, eventually operating dozens of missions to the Guale

Guale was a historic Native American chiefdom of Mississippian culture peoples located along the coast of present-day Georgia and the Sea Islands. Spanish Florida established its Roman Catholic missionary system in the chiefdom in the late 16t ...

, Timucua

The Timucua were a Native American people who lived in Northeast and North Central Florida and southeast Georgia. They were the largest indigenous group in that area and consisted of about 35 chiefdoms, many leading thousands of people. The v ...

and Apalachee

The Apalachee were an Indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands, specifically an Indigenous people of Florida, who lived in the Florida Panhandle until the early 18th century. They lived between the Aucilla River and Ochlockonee River,B ...

tribes. The missions were not without conflict, and the Guale first rebelled on October 4, 1597, in what is now coastal Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

.

The extension of the mission system also provided a military strategic advantage from British troops arriving from the North. During the hundred-plus year span of missionary expansion, disease from the Europeans had a significant impact on the natives, along with the rising power of the French and British.M. A. Young, Gloria ''The Expedition of Hernando De Soto West of the Mississippi, 1541–1543''. University of Arkansas Press, 1999. p. 24. During the

Queen Anne's War

Queen Anne's War (1702–1713) was the second in a series of French and Indian Wars fought in North America involving the colonial empires of Great Britain, France, and Spain; it took place during the reign of Anne, Queen of Great Britain. In E ...

, the British destroyed most of the missions. By 1706, the missionaries abandoned their mission outposts and returned to St. Augustine.

Period of friendship

Spanish Governor

Spanish Governor Pedro de Ibarra

Pedro de Ibarra was a Spanish general who served as a Royal Governor of Spanish Florida (1603 – 1610).

Early years

Originally from the Basque Country, Ibarra joined the Spanish Army in his youth and eventually attained the rank of general.

In ...

worked at establishing peace with the native cultures to the South of St. Augustine. An account is recorded of his meeting with great Indian caciques (chiefs). Ybarra (Ibarra) in 1605 sent Álvaro Mexía

Alvaro Mexia was a 17th-century Spanish explorer and cartographer of the east coast of Florida. Mexia was stationed in St Augustine and was given a diplomatic mission to the native populations living south of St. Augustine and in the Cape Canave ...

, a cartographer, on a mission further South to meet and develop diplomatic ties with the Ais AIS may refer to:

Medicine

* Abbreviated Injury Scale, an anatomical-based coding system to classify and describe the severity of injuries

* Acute ischemic stroke, the thromboembolic type of stroke

* Androgen insensitivity syndrome, an intersex ...

Indian nation, and to make a map of the region. His mission was successful.

In February 1647, the Apalachee

The Apalachee were an Indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands, specifically an Indigenous people of Florida, who lived in the Florida Panhandle until the early 18th century. They lived between the Aucilla River and Ochlockonee River,B ...

revolted. The revolt changed the relationship between Spanish authorities and the Apalachee. Following the revolt, Apalachee men were forced to work on public projects in St. Augustine or on Spanish-owned ranches. In 1656, the Timucua

The Timucua were a Native American people who lived in Northeast and North Central Florida and southeast Georgia. They were the largest indigenous group in that area and consisted of about 35 chiefdoms, many leading thousands of people. The v ...

rebelled, disrupting the Spanish missions in Florida

Beginning in the second half of the 16th century, the Kingdom of Spain established a number of missions throughout ''La Florida'' in order to convert the Native Americans to Christianity, to facilitate control of the area, and to prevent its ...

. This also affected the ranches and food supplies for St. Augustine.

The economy of Spanish Florida diversified during the 17th century, with cattle ranching playing a major role. Throughout the 17th century, colonists from the Carolina and Virginia colonies gradually pushed the frontier of Spanish Florida south. In the early 18th century, French settlements along the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

and Gulf Coast

The Gulf Coast of the United States, also known as the Gulf South, is the coast, coastline along the Southern United States where they meet the Gulf of Mexico. The list of U.S. states and territories by coastline, coastal states that have a shor ...

encroached on the western borders of the Spanish claim.

Starting in 1680, Carolina colonists and their Native American allies repeatedly attacked Spanish mission villages and St. Augustine, burning missions and killing or kidnapping the Indian population. In 1702, James Moore led an army of colonists and a Native American force of Yamasee

The Yamasees (also spelled Yamassees or Yemassees) were a multiethnic confederation of Native Americans who lived in the coastal region of present-day northern coastal Georgia near the Savannah River and later in northeastern Florida. The Yamas ...

, Tallapoosa, Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = "Alabama (state song), Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery, Alabama, Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville, Alabama, Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County, Al ...

, and other Creek warriors under the Yamasee chief Arratommakaw. The army attacked and razed the town of St. Augustine, but could not gain control of the fort. Moore in 1704 made a series of raids into the Apalachee Province

Apalachee Province was the area in the Panhandle of the present-day U.S. state of Florida inhabited by the Native American peoples known as the Apalachee at the time of European contact. The southernmost extent of the Mississippian culture, th ...

of Florida, looting and destroying most of the remaining Spanish missions and killing or enslaving most of the Indian population. By 1707 the few surviving Indians had fled to Spanish St. Augustine and Pensacola, or French Mobile

Mobile may refer to:

Places

* Mobile, Alabama, a U.S. port city

* Mobile County, Alabama

* Mobile, Arizona, a small town near Phoenix, U.S.

* Mobile, Newfoundland and Labrador

Arts, entertainment, and media Music Groups and labels

* Mobile ( ...

. Some of the Native Americans captured by Moore's army were resettled along the Savannah

A savanna or savannah is a mixed woodland-grassland (i.e. grassy woodland) ecosystem characterised by the trees being sufficiently widely spaced so that the Canopy (forest), canopy does not close. The open canopy allows sufficient light to rea ...

and the Ocmulgee rivers in Georgia.

At the end of the 17th century and early in the 18th century the Spanish attempted to block French expansion from Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

along the Gulf coast

The Gulf Coast of the United States, also known as the Gulf South, is the coast, coastline along the Southern United States where they meet the Gulf of Mexico. The list of U.S. states and territories by coastline, coastal states that have a shor ...

towards Florida. In 1696 they founded the Presidio Santa Maria de Galve

The Presidio Santa María de Galve, founded in 1698 by Spanish colonists, was the first European settlement of Pensacola, Florida after that of Tristan de Luna in 1559–1561. It was in the area of Fort Barrancas at modern-day Naval Air Station Pe ...

on Pensacola Bay

Pensacola Bay is a bay located in the northwestern part of Florida, United States, known as the Florida Panhandle.

The bay, an inlet of the Gulf of Mexico, is located in Escambia County and Santa Rosa County, adjacent to the city of Pensacola ...

near the present-day site of Fort Barrancas

Fort Barrancas (1839) or Fort San Carlos de Barrancas (from 1787) is a United States military fort and National Historic Landmark in the former Warrington area of Pensacola, Florida, located physically within Naval Air Station Pensacola, which wa ...

at Naval Air Station Pensacola

Naval Air Station Pensacola or NAS Pensacola (formerly NAS/KNAS until changed circa 1970 to allow Nassau International Airport, now Lynden Pindling International Airport, to have IATA code NAS), "The Cradle of Naval Aviation", is a United State ...

, followed by the foundation in 1701 of the Presidio Bahía San José de Valladares on St. Joseph Bay

St. Joseph Bay is a bay on the Gulf Coast of the U.S. state of Florida. The bay is located in Gulf County between Apalachicola and Panama City. Port St. Joe is located on St. Joseph Bay.

St. Joseph Bay is bounded on the east by the mainland, o ...

. These presidio

A presidio ( en, jail, fortification) was a fortified base established by the Spanish Empire around between 16th and 18th centuries in areas in condition of their control or influence. The presidios of Spanish Philippines in particular, were cen ...

s were under the direct authority of the Viceroy of New Spain

New Spain, officially the Viceroyalty of New Spain ( es, Virreinato de Nueva España, ), or Kingdom of New Spain, was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established by Habsburg Spain during the Spanish colonization of the Am ...

rather than the governor of Spanish Florida in St. Augustine. The French captured Bahía San José de Valladares in 1718, and Santa Maria de Galve in 1719. After losing Santa Maria de Galve, the Spanish established the Presidio Bahía San José de Nueva Asturias on St. Joseph Point in 1719, as well as a fort at the mouth of the Apalachicola River. Spain regained the Pensacola Bay area from the French in 1722, and established the Presidio Isla Santa Rosa Punta de Siguenza on Santa Rosa Island, abandoning the Bahía San José site. After Isla Santa Rosa Punta de Siguenza was destroyed by a hurricane in 1752, the Spanish relocated to the Presidio San Miguel de Panzacola, which developed into the city of Pensacola

Pensacola () is the westernmost city in the Florida Panhandle, and the county seat and only incorporated city of Escambia County, Florida, United States. As of the 2020 United States census, the population was 54,312. Pensacola is the principal ci ...

. In 1718, the Spanish founded the Presidio San Marcos de Apalachee at the existing port of San Marcos, under the authority of the governor in St. Augustine. This presidio developed into the town of St. Marks.

Some Spanish men married or had unions with Pensacola, Creek, or African

African or Africans may refer to:

* Anything from or pertaining to the continent of Africa:

** People who are native to Africa, descendants of natives of Africa, or individuals who trace their ancestry to indigenous inhabitants of Africa

*** Ethn ...

women, both slave and free, and their descendants created a mixed-race population of mestizo

(; ; fem. ) is a term used for racial classification to refer to a person of mixed Ethnic groups in Europe, European and Indigenous peoples of the Americas, Indigenous American ancestry. In certain regions such as Latin America, it may also r ...

s and mulattos. The Spanish encouraged slaves from the southern colonies to come to Florida as a refuge, promising freedom in exchange for conversion to Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

. King Charles II of Spain

Charles II of Spain (''Spanish: Carlos II,'' 6 November 1661 – 1 November 1700), known as the Bewitched (''Spanish: El Hechizado''), was the last Habsburg ruler of the Spanish Empire. Best remembered for his physical disabilities and the War ...

issued a royal proclamation freeing all slaves who fled to Spanish Florida and accepted conversion and baptism. Most went to the area around St. Augustine, but escaped slaves also reached Pensacola. St. Augustine had mustered an all-black militia unit defending Spain as early as 1683.

During the 18th century, the Native American peoples who would become the Seminole

The Seminole are a Native American people who developed in Florida in the 18th century. Today, they live in Oklahoma and Florida, and comprise three federally recognized tribes: the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, the Seminole Tribe of Florida, an ...

s began their migration to Florida, which had been largely depopulated by Carolinian and Yamasee slave raids. Carolina's power was damaged and the colony nearly destroyed during the Yamasee War

The Yamasee War (also spelled Yamassee or Yemassee) was a conflict fought in South Carolina from 1715 to 1717 between British settlers from the Province of Carolina and the Yamasee and a number of other allied Native American peoples, incl ...

of 1715–1717, after which the Native American slave trade was radically reformed.

Spanish Florida was a destination for escaped slaves from the Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, also known as the Thirteen British Colonies, the Thirteen American Colonies, or later as the United Colonies, were a group of Kingdom of Great Britain, British Colony, colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. Fo ...

. The Spanish authorities offered them freedom if they converted to Catholicism and served in the colonial militia. (Some, such as those from Angola

, national_anthem = " Angola Avante"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capital = Luanda

, religion =

, religion_year = 2020

, religion_ref =

, coordina ...

, were already Catholic.) This policy was formalized in 1693.

Possession by Britain

Havana

Havana (; Spanish: ''La Habana'' ) is the capital and largest city of Cuba. The heart of the La Habana Province, Havana is the country's main port and commercial center.

, Cuba, and Manila in the Philippines, which had been captured by the British during the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754� ...

. As Britain had defeated France in the war, it took over all of French Louisiana

The term French Louisiana refers to two distinct regions:

* first, to colonial French Louisiana, comprising the massive, middle section of North America claimed by France during the 17th and 18th centuries; and,

* second, to modern French Louisi ...

east of the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

, except for New Orleans

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

. Finding this new territory too vast to govern as a single unit, Britain divided the southernmost areas into two territories separated by the Apalachicola River: Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

East Florida

East Florida ( es, Florida Oriental) was a colony of Great Britain from 1763 to 1783 and a province of Spanish Florida from 1783 to 1821. Great Britain gained control of the long-established Spanish colony of ''La Florida'' in 1763 as part of ...

(the peninsula) and West Florida

West Florida ( es, Florida Occidental) was a region on the northern coast of the Gulf of Mexico that underwent several boundary and sovereignty changes during its history. As its name suggests, it was formed out of the western part of former S ...

(the panhandle).

Notably, most of the Spanish population departed following the signing of the treaty, with the entirety of St Augustine emigrating to Cuba.

The British soon began an aggressive recruiting policy to attract colonists to the area, offering free land and backing for export-oriented businesses. In 1764, the British moved the northern boundary of West Florida to a line extending from the mouth of the Yazoo River

The Yazoo River is a river in the U.S. states of Louisiana and Mississippi. It is considered by some to mark the southern boundary of what is called the Mississippi Delta, a broad floodplain that was cultivated for cotton plantations before th ...

east to the Chattahoochee River (32° 22′ north latitude), consisting of approximately the lower third of the present states of Mississippi

Mississippi () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States, bordered to the north by Tennessee; to the east by Alabama; to the south by the Gulf of Mexico; to the southwest by Louisiana; and to the northwest by Arkansas. Miss ...

and Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = "Alabama (state song), Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery, Alabama, Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville, Alabama, Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County, Al ...

, including the valuable Natchez District

The Natchez District was one of two areas established in the Kingdom of Great Britain's West Florida colony during the 1770sthe other being the Tombigbee District. The first Anglo settlers in the district came primarily from other parts of Britis ...

.

During this time, Creek Indians began to migrate into Florida, leading to the formation of the Seminole

The Seminole are a Native American people who developed in Florida in the 18th century. Today, they live in Oklahoma and Florida, and comprise three federally recognized tribes: the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, the Seminole Tribe of Florida, an ...