Spandau Prison on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Spandau Prison was located in the

Spandau Prison was located in the

The prison was demolished in August 1987, largely to prevent it from becoming a

The prison was demolished in August 1987, largely to prevent it from becoming a

Spandau Prison on Western Allies Berlin Website

A first hand account from a serving British officer of guarding Rudolf Hess in Spandau Prison

{{Authority control 1876 establishments in Germany Government buildings completed in 1876 Buildings and structures demolished in 1987 Defunct prisons in Germany Buildings and structures in Spandau Allied occupation of Germany Rudolf Hess 1987 disestablishments in Germany Demolished prisons Demolished buildings and structures in Berlin

Spandau Prison was located in the

Spandau Prison was located in the borough

A borough is an administrative division in various English-speaking countries. In principle, the term ''borough'' designates a self-governing walled town, although in practice, official use of the term varies widely.

History

In the Middle Ag ...

of Spandau

Spandau () is the westernmost of the 12 boroughs () of Berlin, situated at the confluence of the Havel and Spree rivers and extending along the western bank of the Havel. It is the smallest borough by population, but the fourth largest by land ...

in West Berlin

West Berlin (german: Berlin (West) or , ) was a political enclave which comprised the western part of Berlin during the years of the Cold War. Although West Berlin was de jure not part of West Germany, lacked any sovereignty, and was under mi ...

. It was originally a military prison, built in 1876, but became a proto-concentration camp under the Nazis

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Na ...

. After the war, it held seven top Nazi leaders convicted in the Nuremberg trials

The Nuremberg trials were held by the Allies of World War II, Allies against representatives of the defeated Nazi Germany, for plotting and carrying out invasions of other countries, and other crimes, in World War II.

Between 1939 and 1945 ...

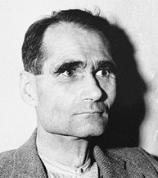

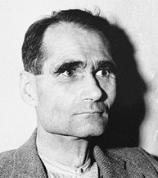

. After the death of its last prisoner, Rudolf Hess

Rudolf Walter Richard Hess (Heß in German; 26 April 1894 – 17 August 1987) was a German politician and a leading member of the Nazi Party in Nazi Germany. Appointed Deputy Führer to Adolf Hitler in 1933, Hess held that position unt ...

, in August 1987, the prison was demolished and replaced by a shopping centre for the British forces

The British Armed Forces, also known as His Majesty's Armed Forces, are the military forces responsible for the defence of the United Kingdom, its Overseas Territories and the Crown Dependencies. They also promote the UK's wider interests, s ...

stationed in Germany to prevent it from becoming a neo-Nazi

Neo-Nazism comprises the post–World War II militant, social, and political movements that seek to revive and reinstate Nazism, Nazi ideology. Neo-Nazis employ their ideology to promote hatred and Supremacism#Racial, racial supremacy (ofte ...

shrine.

History

Spandau Prison was built in 1876 onWilhelmstraße

Wilhelmstrasse (german: Wilhelmstraße, see ß) is a major thoroughfare in the central Mitte (locality), Mitte and Kreuzberg districts of Berlin, Germany. Until 1945, it was recognised as the centre of the government, first of the Kingdom of Pru ...

. It initially served as a military detention center of the Prussian Army

The Royal Prussian Army (1701–1919, german: Königlich Preußische Armee) served as the army of the Kingdom of Prussia. It became vital to the development of Brandenburg-Prussia as a European power.

The Prussian Army had its roots in the co ...

. From 1919 it was also used for civilian inmates. It held up to 600 inmates at that time.

In the aftermath of the Reichstag fire

The Reichstag fire (german: Reichstagsbrand, ) was an arson attack on the Reichstag building, home of the German parliament in Berlin, on Monday 27 February 1933, precisely four weeks after Nazi leader Adolf Hitler was sworn in as Chancellor of ...

of 1933, opponents of Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and then ...

, and journalist

A journalist is an individual that collects/gathers information in form of text, audio, or pictures, processes them into a news-worthy form, and disseminates it to the public. The act or process mainly done by the journalist is called journalism ...

s such as Egon Kisch

Egon Erwin Kisch (29 April 1885 – 31 March 1948) was an Austrian and Czechoslovak writer and journalist, who wrote in German. He styled himself ''Der Rasende Reporter'' (The Raging Reporter) for his countless travels to the far corners of the g ...

and Carl von Ossietzky

Carl von Ossietzky (; 3 October 1889 – 4 May 1938) was a German journalist and pacifist. He was the recipient of the 1935 Nobel Peace Prize for his work in exposing the clandestine German re-armament.

As editor-in-chief of the magazine ''Die ...

, were held there in so-called protective custody

Protective custody (PC) is a type of imprisonment (or care) to protect a person from harm, either from outside sources or other prisoners. Many prison administrators believe the level of violence, or the underlying threat of violence within pri ...

. Spandau Prison became a sort of predecessor of the Nazi concentration camps

From 1933 to 1945, Nazi Germany operated more than a thousand concentration camps, (officially) or (more commonly). The Nazi concentration camps are distinguished from other types of Nazi camps such as forced-labor camps, as well as concen ...

. While it was formally operated by the Prussian Ministry of Justice, the Gestapo

The (), abbreviated Gestapo (; ), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of Prussia into one organi ...

tortured and abused its inmates, as Kisch recalled in his memories of the prison. By the end of 1933 the first Nazi concentration camps had been erected (at Dachau

,

, commandant = List of commandants

, known for =

, location = Upper Bavaria, Southern Germany

, built by = Germany

, operated by = ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS)

, original use = Political prison

, construction ...

, Osthofen

Osthofen () is a town in the middle of the Wonnegau in the Alzey-Worms district in Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. Since 1 July 2014 it is part of the ''Verbandsgemeinde'' (a kind of collective municipality) Wonnegau. Osthofen was raised to town on ...

, Oranienburg

Oranienburg () is a town in Brandenburg, Germany. It is the capital of the district of Oberhavel.

Geography

Oranienburg is a town located on the banks of the Havel river, 35 km north of the centre of Berlin.

Division of the town

Oranienburg ...

, Sonnenburg, Lichtenburg and the marshland camps around Esterwegen

Esterwegen is a municipality in the Emsland district, in Lower Saxony, Germany.

Geography

Esterwegen lies in northwest Germany, less than from the Dutch border and about from the sea.

Demographics

In 2015 the population was 5,280.

Government ...

); all remaining prisoners who had been held in so-called protective custody in state prisons were transferred to these concentration camps.

After World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

the prison fell in the British Sector of what became West Berlin

West Berlin (german: Berlin (West) or , ) was a political enclave which comprised the western part of Berlin during the years of the Cold War. Although West Berlin was de jure not part of West Germany, lacked any sovereignty, and was under mi ...

but it was operated by the Four-Power Authorities

Following the defeat of Nazi Germany and then the partition of German territory, two Four-Power Authorities, in which the four main victor nations (the United States, the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union and France) managed equally, were created.

...

to house the Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

war criminals sentenced to imprisonment at the Nuremberg Trials

The Nuremberg trials were held by the Allies of World War II, Allies against representatives of the defeated Nazi Germany, for plotting and carrying out invasions of other countries, and other crimes, in World War II.

Between 1939 and 1945 ...

.

Only seven prisoners were finally imprisoned there. Arriving from Nuremberg on 18 July 1947, they were:

Of the seven, three were released after serving their full sentences, while three others (including Raeder and Funk, who were given life sentences) were released earlier due to ill health. Between 1966 and 1987, Rudolf Hess

Rudolf Walter Richard Hess (Heß in German; 26 April 1894 – 17 August 1987) was a German politician and a leading member of the Nazi Party in Nazi Germany. Appointed Deputy Führer to Adolf Hitler in 1933, Hess held that position unt ...

was the only inmate in the prison and his only companion was the warden, Eugene K. Bird

Lieutenant Colonel Eugene K. Bird (11 March 1926 – 28 October 2005) was US Commandant of the Spandau Allied Prison from 1964 to 1972 where, together with six others, Deputy Führer Rudolf Hess was incarcerated.

In March 1971, Bird's superio ...

, who became a close friend. Bird wrote a book about Hess's imprisonment titled ''The Loneliest Man in the World''.

Spandau was one of only two Four-Power organizations to continue to operate after the breakdown of the Allied Control Council

The Allied Control Council or Allied Control Authority (german: Alliierter Kontrollrat) and also referred to as the Four Powers (), was the governing body of the Allied Occupation Zones in Germany and Allied-occupied Austria after the end of Wo ...

; the other was the Berlin Air Safety Center

The Berlin Air Safety Centre (BASC) was established by the Allied Control Council's Coordinating Committee on 12 December 1945. It was located in the former Kammergericht Building, on Kleistpark, Berlin. Operations began in February 1946 under q ...

. The four occupying powers of Berlin alternated control of the prison on a monthly basis, each having the responsibility for a total of three months out of the year. Observing the Four-Power flags that flew at the Allied Control Authority building could determine who controlled the prison.

neo-Nazi

Neo-Nazism comprises the post–World War II militant, social, and political movements that seek to revive and reinstate Nazism, Nazi ideology. Neo-Nazis employ their ideology to promote hatred and Supremacism#Racial, racial supremacy (ofte ...

shrine, after the death of its final remaining prisoner, Rudolf Hess

Rudolf Walter Richard Hess (Heß in German; 26 April 1894 – 17 August 1987) was a German politician and a leading member of the Nazi Party in Nazi Germany. Appointed Deputy Führer to Adolf Hitler in 1933, Hess held that position unt ...

. To further ensure its erasure, the site was made into a parking facility and a shopping center, named '' The Britannia Centre Spandau'' and nicknamed ''Hessco's'' after the well known British supermarket chain, Tesco

Tesco plc () is a British multinational groceries and general merchandise retailer headquartered in Welwyn Garden City, England. In 2011 it was the third-largest retailer in the world measured by gross revenues and the ninth-largest in th ...

. All materials from the demolished prison were ground to powder and dispersed in the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian S ...

or buried at the former RAF Gatow

Royal Air Force Gatow, or more commonly RAF Gatow, was a British Royal Air Force station (military airbase) in the district of Gatow in south-western Berlin, west of the Havel river, in the borough of Spandau. It was the home for the only kno ...

airbase, with the exception of a single set of keys now exhibited in the regimental museum of the King's Own Scottish Borderers

The King's Own Scottish Borderers (KOSBs) was a line infantry regiment of the British Army, part of the Scottish Division. On 28 March 2006 the regiment was amalgamated with the Royal Scots, the Royal Highland Fusiliers (Princess Margaret's Own ...

at Berwick Barracks

Berwick Barracks, sometimes known as Ravensdowne Barracks, is a former military installation of the British Army in Berwick-upon-Tweed, England.

History

The barracks were built between 1717 and 1721 by Nicholas Hawksmoor for the Board of Ordnance ...

.

The prison

The prison, initially designed for a population in the hundreds, was an old brick building enclosed by one wall high, another of , a high wall topped with electrified wire, followed by a wall ofbarbed wire

A close-up view of a barbed wire

Roll of modern agricultural barbed wire

Barbed wire, also known as barb wire, is a type of steel fencing wire constructed with sharp edges or points arranged at intervals along the strands. Its primary use is t ...

. In addition, some of the sixty soldiers on guard duty manned six machine-gun armed guard towers 24 hours a day. Due to the number of cells available, an empty cell was left between the prisoners' cells, to avoid the possibility of prisoners' communicating in Morse code

Morse code is a method used in telecommunication to encode text characters as standardized sequences of two different signal durations, called ''dots'' and ''dashes'', or ''dits'' and ''dahs''. Morse code is named after Samuel Morse, one of ...

. Other remaining cells in the wing were designated for other purposes, with one used for the prison library and another for a chapel. The cells were approximately long by wide and high.

Garden

The highlight of the prison, from the inmates' perspective, was the garden. Very spacious given the small number of prisoners using it, the garden space was initially divided into small personal plots that were used by each prisoner in various ways, usually to grow vegetables. Dönitz favoured growing beans, Funk tomatoes and Speer daisies, although the Soviet director subsequently banned flowers for a time. By regulation, all of the produce was to be put toward use in the prison kitchen, but prisoners and guards alike often skirted this rule and indulged in the garden's offerings. As prison regulations slackened and as prisoners became either apathetic or too ill to maintain their plots, the garden was consolidated into one large workable area. This suited the formerarchitect

An architect is a person who plans, designs and oversees the construction of buildings. To practice architecture means to provide services in connection with the design of buildings and the space within the site surrounding the buildings that h ...

Speer, who, being one of the youngest and liveliest of the inmates, later took up the task of refashioning the entire plot of land into a large complex garden, complete with paths, rock garden

A rock garden, also known as a rockery and formerly as a rockwork, is a garden, or more often a part of a garden, with a landscaping framework of rocks, stones, and gravel, with planting appropriate to this setting. Usually these are small A ...

s and floral displays. On days without access to the garden, for instance when it was raining, the prisoners occupied their time making envelopes together in the main corridor.

Underutilization

The Allied powers originally requisitioned the prison in November 1946, expecting it to accommodate a hundred or more war criminals. Besides the sixty or so soldiers on duty in or around the prison at any given time, there were teams of professional civilian warders from each of the four countries, four prison directors and their deputies, four army medical officers, cooks, translators, waiters, porters and others. This was perceived as a drastic misallocation of resources and became a serious point of contention among the prison directors, politicians from their respective countries, and especially theWest Berlin

West Berlin (german: Berlin (West) or , ) was a political enclave which comprised the western part of Berlin during the years of the Cold War. Although West Berlin was de jure not part of West Germany, lacked any sovereignty, and was under mi ...

government, who were left to foot the bill for Spandau yet suffered from a lack of space in their own prison system. The debate surrounding the imprisonment of seven war criminals in such a large space, with numerous and expensive complementary staff, was only heightened as time went on and prisoners were released.

Acrimony reached its peak after the release of Speer and Schirach in 1966, leaving only one inmate, Hess, remaining in an otherwise under-utilized prison. Various proposals were made to remedy this situation over the years, ranging from moving the prisoners to an appropriately sized wing of another larger, occupied prison, to releasing them; house arrest

In justice and law, house arrest (also called home confinement, home detention, or, in modern times, electronic monitoring) is a measure by which a person is confined by the authorities to their residence. Travel is usually restricted, if all ...

was also considered. Nevertheless, an official refraining order went into effect, forbidding the approaching of unsettled prisoners, and so the prison remained exclusively for the seven war criminals for the remainder of its existence.

Life in the prison

Prison regulations

Every facet of life in the prison was strictly set out by an intricate prison regulation scheme designed before the prisoners' arrival by the Four Powers –France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

, the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

, and the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

. Compared with other established prison regulations at the time, Spandau's rules were quite strict. The prisoners' outgoing letters to families were at first limited to one page every month, talking with fellow prisoners was prohibited, newspapers were banned, diaries and memoir

A memoir (; , ) is any nonfiction narrative writing based in the author's personal memories. The assertions made in the work are thus understood to be factual. While memoir has historically been defined as a subcategory of biography or autobi ...

s were forbidden, visits by families were limited to fifteen minutes every two months, and lights were flashed into the prisoners' cells every fifteen minutes during the night as a form of suicide

Suicide is the act of intentionally causing one's own death. Mental disorders (including depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, personality disorders, anxiety disorders), physical disorders (such as chronic fatigue syndrome), and s ...

watch. A considerable portion of the stricter regulations was either later revised toward the more lenient, or deliberately ignored by prison staff.

The directors and guards of the Western powers (France, Britain, and the United States) repeatedly voiced opposition to many of the stricter measures and made near-constant protest about them to their superiors throughout the prison's existence, but they were invariably vetoed by the Soviet Union, which favored a tougher approach. The Soviet Union, which suffered between 10 and 19 million civilian deaths during the war and had pressed at the Nuremberg trials

The Nuremberg trials were held by the Allies of World War II, Allies against representatives of the defeated Nazi Germany, for plotting and carrying out invasions of other countries, and other crimes, in World War II.

Between 1939 and 1945 ...

for the execution of all the current inmates, was unwilling to compromise with the Western powers in this regard, both because of the harsher punishment that they felt was justified, and to stress the Communist propaganda line that the capitalist powers had supposedly never been serious about denazification

Denazification (german: link=yes, Entnazifizierung) was an Allied initiative to rid German and Austrian society, culture, press, economy, judiciary, and politics of the Nazi ideology following the Second World War. It was carried out by remov ...

. This contrasted with Werl Prison

Werl Prison has about 900 inmates, and is one of the largest prisons in Germany. It is located in the town of Werl in the state of North Rhine-Westphalia, east of Dortmund.

In April 1945, the 95th Infantry Division (United States) "Victory" divis ...

, which housed hundreds of former officers and other lower-ranking Nazi men who were under a comparatively lax regime. However, a more contemporary consideration was that the continued incarceration of even one Nazi (i.e. Hess) in Spandau ensured a conduit that guaranteed the Soviets access to West Berlin would remain open, and Western commentators frequently accused the Russians of keeping Spandau prison in operation chiefly as a centre for Soviet espionage operations.

Daily life

Every day, prisoners were ordered to rise at 6 a.m., wash, clean their cells and the corridor together, eat breakfast, stay in the garden until lunch-time at noon (weather permitting), have a post-lunch rest in their cells, and then return to the garden. Supper followed at 5 p.m., after which the prisoners were returned to their cells. Lights out was at 10 p.m. Prisoners received a shave and a haircut, if necessary, on Mondays, Wednesdays, or Fridays; they did their own laundry every Monday. This routine, except the time allowed in the garden, changed very little throughout the years, although each of the controlling nations made their own interpretation of the prison regulations. Within a few years of their arrival at the prison, all sorts of illicit lines of communication with the outside world were opened for the inmates by sympathetic staff. These supplementary lines were free of the censorship placed on authorised communications, and were also virtually unlimited in volume, ordinarily occurring on either Sundays or Thursdays (except during times of total lock-down of exchanges). Every piece of paper given to the prisoners was recorded and tracked, so secret notes were most often written by other means, where the supply went officially unmonitored for the entire duration of the prison's existence. Many inmates took full advantage of this. Albert Speer, after having his official request to write his memoirs denied, finally began setting down his experiences and perspectives of his time with the Nazi regime, which were smuggled out and later released as a bestselling book, ''Inside the Third Reich

''Inside the Third Reich'' (german: Erinnerungen, "Memories") is a memoir written by Albert Speer, the Nazi Minister of Armaments from 1942 to 1945, serving as Adolf Hitler's main architect before this period. It is considered to be one of the ...

''. Dönitz wrote letters to his former deputy regarding the protection of his prestige in the outside world. When his release was near, he gave instructions to his wife on how best she could help ease his transition back into politics, which he intended, but never actually accomplished. Walther Funk

Walther Funk (18 August 1890 – 31 May 1960) was a German economist and Nazi official who served as Reich Minister for Economic Affairs (1938–1945) and president of Reichsbank (1939–1945). During his incumbency, he oversaw the mobili ...

managed to obtain a seemingly constant supply of cognac

Cognac ( , also , ) is a variety of brandy named after the Communes of France, commune of Cognac, France. It is produced in the surrounding wine-growing region in the Departments of France, departments of Charente and Charente-Maritime.

Cog ...

(all alcohol was banned) and other treats that he would share with other prisoners on special occasions.

The Spandau Seven

The prisoners, still subject to the petty personal rivalries and battles for prestige that characterized Nazi party politics, divided themselves into groups:Albert Speer

Berthold Konrad Hermann Albert Speer (; ; 19 March 1905 – 1 September 1981) was a German architect who served as the Minister of Armaments and War Production in Nazi Germany during most of World War II. A close ally of Adolf Hitler, he ...

and Rudolf Hess

Rudolf Walter Richard Hess (Heß in German; 26 April 1894 – 17 August 1987) was a German politician and a leading member of the Nazi Party in Nazi Germany. Appointed Deputy Führer to Adolf Hitler in 1933, Hess held that position unt ...

were the loner

A loner is a person who does not seek out, or may actively avoid, interaction with other people. There are many potential reasons for their solitude. Intentional reasons include introversion, mysticism, spirituality, religion, or personal consid ...

s, generally disliked by the others – the former for his admission of guilt and repudiation of Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and then ...

at the Nuremberg trials, the latter for his antisocial

Antisocial may refer to:

Sociology, psychiatry and psychology

*Anti-social behaviour

*Antisocial personality disorder

*Psychopathy

*Conduct disorder

Law

*Anti-social Behaviour Act 2003

*Anti-Social Behaviour Order

*Crime and Disorder Act 1998

*P ...

personality and perceived mental instability. The two former Grand admiral

Grand admiral is a historic naval rank, the highest rank in the several European navies that used it. It is best known for its use in Germany as . A comparable rank in modern navies is that of admiral of the fleet.

Grand admirals in individual n ...

s, Erich Raeder

Erich Johann Albert Raeder (24 April 1876 – 6 November 1960) was a German admiral who played a major role in the naval history of World War II. Raeder attained the highest possible naval rank, that of grand admiral, in 1939, becoming the fir ...

and Karl Dönitz

Karl Dönitz (sometimes spelled Doenitz; ; 16 September 1891 24 December 1980) was a German admiral who briefly succeeded Adolf Hitler as head of state in May 1945, holding the position until the dissolution of the Flensburg Government follo ...

, stayed together, despite their heated mutual dislike. This situation had come about when Dönitz replaced Raeder as Commander in Chief of the German navy in 1943. Baldur von Schirach

Baldur Benedikt von Schirach (9 May 1907 – 8 August 1974) was a German politician who is best known for his role as the Nazi Party national youth leader and head of the Hitler Youth from 1931 to 1940. He later served as ''Gauleiter'' and ''Re ...

and Walther Funk

Walther Funk (18 August 1890 – 31 May 1960) was a German economist and Nazi official who served as Reich Minister for Economic Affairs (1938–1945) and president of Reichsbank (1939–1945). During his incumbency, he oversaw the mobili ...

were described as "inseparable". Konstantin von Neurath

Konstantin Hermann Karl Freiherr von Neurath (2 February 1873 – 14 August 1956) was a German diplomat and Nazi war criminal who served as Foreign Minister of Germany between 1932 and 1938.

Born to a Swabian noble family, Neurath began his di ...

was, being a former diplomat, amiable and amenable to all the others.

Despite the length of time they spent with each other, remarkably little progress was made in the way of reconciliation. A notable example was Dönitz's dislike of Speer being steadfastly maintained for his entire 10-year sentence, with it only coming to a head during the last few days of his imprisonment. Dönitz always believed that Hitler had named him as his successor due to Speer's recommendation, which had led to Dönitz being tried at Nuremberg (Speer always denied this).

There is also a collection of medical reports concerning Baldur von Schirach, Albert Speer, and Rudolf Hess made during their confinement at Spandau which have survived.

Albert Speer

Erich Raeder and Karl Dönitz

"The Admiralty", as the other prisoners referred toDönitz

Dönitz is a village and a former municipality in the district Altmarkkreis Salzwedel, in Saxony-Anhalt, Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous c ...

and Raeder, were often teamed together for various tasks. Raeder, with a liking for rigid systems and organization, designated himself as chief librarian of the prison library, with Dönitz as his assistant. Each designed their own sleeve insignia for both chief librarian (a silver book) and assistant chief librarian (a gold book) which were woven with the appropriate colored thread. Both men often withheld themselves from the other prisoners, with Dönitz claiming for his entire ten years in prison that he was still the rightful head of the German state (he also got one vote in the 1954 West German presidential election

An indirect presidential election (officially the 2nd Federal Convention) was held in West Germany on 17 July 1954. The government parties and the opposition SPD renominated incumbent Theodor Heuss. Against his wishes, the Communist Party of Germa ...

), and Raeder having contempt for the insolence and lack of discipline endemic in his nonmilitary fellow prisoners. Despite preferring to stay together, the two of them continued their wartime feud and argued most of the time over whether Raeder's battleships or Dönitz's U-boats were responsible for losing the war. This feud often resulted in fights. After Dönitz's release in 1956 he wrote two books, one on his early life, ''My Ever-Changing Life'', and one on his time as an admiral, ''Ten Years and Twenty Days''. Raeder, in failing health and seemingly close to death, was released in 1955 and died in 1960.

Rudolf Hess

Rudolf Hess

Rudolf Walter Richard Hess (Heß in German; 26 April 1894 – 17 August 1987) was a German politician and a leading member of the Nazi Party in Nazi Germany. Appointed Deputy Führer to Adolf Hitler in 1933, Hess held that position unt ...

, sentenced to life but not released due to ill health as were Raeder, Funk, or Neurath, served the longest sentence out of the seven and was by far the most demanding of the prisoners. Regarded as being the 'laziest man in Spandau', Hess avoided all forms of work that he deemed below his dignity, such as pulling weeds. He was the only one of the seven who almost never attended the prison's Sunday church service. A paranoid hypochondriac

Hypochondriasis or hypochondria is a condition in which a person is excessively and unduly worried about having a serious illness. An old concept, the meaning of hypochondria has repeatedly changed. It has been claimed that this debilitating cond ...

, he repeatedly complained of all forms of illness, mostly stomach pains, and was suspicious of all food given to him, always taking the dish placed farthest away from him as a means of avoiding being poisoned. His alleged stomach pains often caused wild and excessive moans and cries of pain throughout the day and night and their authenticity was repeatedly the subject of debate between the prisoners and the prison directors.

Raeder, Dönitz, and Schirach were contemptuous of this behaviour and viewed them as cries for attention or as means to avoid work. Speer and Funk, acutely aware of the likely psychosomatic

A somatic symptom disorder, formerly known as a somatoform disorder,(2013) perforated ulcer

A perforated ulcer is a condition in which an untreated ulcer has burned through the mucosal wall in a segment of the gastrointestinal tract (e.g., the stomach or colon) allowing gastric contents to leak into the abdominal cavity.

Signs and symp ...

that required treatment at a hospital outside the prison. Fearing for his mental health now that he was the sole remaining inmate, and assuming that his death was imminent, the prison directors agreed to slacken most of the remaining regulations, moving Hess to the more spacious former chapel space, giving him a water heater to allow the making of tea or coffee when he liked, and permanently unlocking his cell so that he could freely access the prison's bathing facilities and library.

Hess was frequently moved from room to room every night for security reasons. He was often taken to the British Military Hospital not far from the prison, where the entire second floor of the hospital was cordoned off for him. He remained under heavy guard while in hospital. Ward security was provided by soldiers including Royal Military Police Close Protection personnel. External security was provided by one of the British infantry battalions then stationed in Berlin. On some unusual occasions, the Soviets relaxed their strict regulations; during these times Hess was allowed to spend extra time in the prison garden, and one of the warders from the superpowers took Hess outside the prison walls for a stroll and sometimes dinner at a nearby Berlin restaurant in a private room.Eugene K. Bird

Lieutenant Colonel Eugene K. Bird (11 March 1926 – 28 October 2005) was US Commandant of the Spandau Allied Prison from 1964 to 1972 where, together with six others, Deputy Führer Rudolf Hess was incarcerated.

In March 1971, Bird's superio ...

(1974) ''Prisoner #7: Rudolf Hess'' p. 234, .

In popular culture

The British bandSpandau Ballet

Spandau Ballet () were an English new wave band formed in Islington, London, in 1979. Inspired by the capital's post-punk underground dance scene, they emerged at the start of the 1980s as the house band for the Blitz Kids, playing "European Da ...

got their name after a friend of the band, journalist and DJ Robert Elms

Robert Frederick Elms (born 12 June 1959) is an English writer and broadcaster. Elms was a writer for ''The Face'' magazine in the 1980s and is currently known for his long-running radio show on BBC Radio London. His book, ''The Way We Wore'', ...

, saw the words 'Spandau Ballet' scrawled on the wall of a nightclub lavatory during a visit to Berlin. The graffiti referred to the way a condemned individual would twitch and "dance" at the end of the rope due to the standard drop method of hangings

Hanging is the suspension of a person by a noose or ligature around the neck.Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed. Hanging as method of execution is unknown, as method of suicide from 1325. The ''Oxford English Dictionary'' states that hanging ...

used at Spandau Prison and was in the tradition of similar gallows humour

Black comedy, also known as dark comedy, morbid humor, or gallows humor, is a style of comedy that makes light of subject matter that is generally considered taboo, particularly subjects that are normally considered serious or painful to discus ...

expressions such as "dancing the Tyburn

Tyburn was a manor (estate) in the county of Middlesex, one of two which were served by the parish of Marylebone.

The parish, probably therefore also the manor, was bounded by Roman roads to the west (modern Edgware Road) and south (modern Ox ...

jig."

The prison featured in the 1985 film ''Wild Geese II

''Wild Geese II'' is a 1985 British action-thriller film directed by Peter Hunt, based on the 1982 novel '' The Square Circle'' by Daniel Carney, in which a group of mercenaries are hired to spring Rudolf Hess from Spandau Prison in Berlin. Th ...

'', about a fictional group of mercenaries who are assigned to kidnap Rudolf Hess

Rudolf Walter Richard Hess (Heß in German; 26 April 1894 – 17 August 1987) was a German politician and a leading member of the Nazi Party in Nazi Germany. Appointed Deputy Führer to Adolf Hitler in 1933, Hess held that position unt ...

(played by Laurence Olivier

Laurence Kerr Olivier, Baron Olivier (; 22 May 1907 – 11 July 1989) was an English actor and director who, along with his contemporaries Ralph Richardson and John Gielgud, was one of a trio of male actors who dominated the Theatre of the U ...

), and in the book ''Spandau Phoenix'' by Greg Iles

Greg Iles (born 1960) is a novelist who lives in Mississippi. He has published seventeen novels and one novella, spanning a variety of genres.

Early life

Iles was born in 1960 in Stuttgart, West Germany, where his physician father ran the US Emba ...

, which is a fictional account of Hess and Spandau Prison.

See also

*Land of the Blind

''Land of the Blind'' is a 2006 British-American drama film starring Ralph Fiennes, Donald Sutherland, Tom Hollander and Lara Flynn Boyle.

''Land of the Blind'' is a dark political satire, based on several incidents throughout history in which ty ...

* Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

* Landsberg Prison

Landsberg Prison is a penal facility in the town of Landsberg am Lech in the southwest of the German state of Bavaria, about west-southwest of Munich and south of Augsburg. It is best known as the prison where Adolf Hitler was held in 1924, a ...

in Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total lan ...

* Spandau Citadel

The Spandau Citadel (german: Zitadelle Spandau) is a fortress in Berlin, Germany, one of the best-preserved Renaissance military structures of Europe. Built from 1559–94 atop a medieval fort on an island near the meeting of the Havel and ...

* Sugamo Prison

Sugamo Prison (''Sugamo Kōchi-sho'', Kyūjitai: , Shinjitai: ) was a prison in Tokyo, Japan. It was located in the district of Ikebukuro, which is now part of the Toshima ward of Tokyo, Japan.

History

Sugamo Prison was originally built in 1 ...

in Tokyo

Tokyo (; ja, 東京, , ), officially the Tokyo Metropolis ( ja, 東京都, label=none, ), is the capital and largest city of Japan. Formerly known as Edo, its metropolitan area () is the most populous in the world, with an estimated 37.468 ...

, Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

* ''Speer und Er

''Speer und Er'' (literally "Speer and He", released as ''Speer and Hitler: The Devil's Architect'') is a three-part German docudrama starring Sebastian Koch as Albert Speer and Tobias Moretti as Adolf Hitler. It mixes historical film material wi ...

'' (Extensive footage of the prison recreated in a studio)

References

Notes . Bibliography * * * * * * * Goda, Norman J.W.: ''Tales from Spandau. Nazi Criminals and the Cold War'' (New York: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2007). *External links

Spandau Prison on Western Allies Berlin Website

A first hand account from a serving British officer of guarding Rudolf Hess in Spandau Prison

{{Authority control 1876 establishments in Germany Government buildings completed in 1876 Buildings and structures demolished in 1987 Defunct prisons in Germany Buildings and structures in Spandau Allied occupation of Germany Rudolf Hess 1987 disestablishments in Germany Demolished prisons Demolished buildings and structures in Berlin