Soviet involvement in regime change entailed both overt and covert actions aimed at altering, replacing, or preserving foreign governments.

In the 1920s the nascent Soviet Union intervened in multiple governments primarily in Asia, acquiring the territory of

Tuva

Tuva (; russian: Тува́) or Tyva ( tyv, Тыва), officially the Republic of Tuva (russian: Респу́блика Тыва́, r=Respublika Tyva, p=rʲɪˈspublʲɪkə tɨˈva; tyv, Тыва Республика, translit=Tyva Respublika ...

and making

Mongolia

Mongolia; Mongolian script: , , ; lit. "Mongol Nation" or "State of Mongolia" () is a landlocked country in East Asia, bordered by Russia to the north and China to the south. It covers an area of , with a population of just 3.3 million, ...

into a satellite state.

During

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

helped overthrow many

Nazi German

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

or

Imperial Japanese

The also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was a historical nation-state and great power that existed from the Meiji Restoration in 1868 until the enactment of the post-World War II 1947 constitution and subsequent forma ...

puppet regime

A puppet state, puppet régime, puppet government or dummy government, is a state that is ''de jure'' independent but ''de facto'' completely dependent upon an outside power and subject to its orders.Compare: Puppet states have nominal sover ...

s, including in East Asia and much of Europe. Soviet forces were also instrumental in ending the rule of

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

over Germany.

In the aftermath of World War II, the Soviet government struggled with the United States for global leadership and influence within the context of the

Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

. It expanded the geographic scope of its actions beyond its traditional area of operations. In addition, the Soviet Union and Russia have

interfered in the national elections of many countries. One study indicated that the Soviet Union and Russia engaged in 36 interventions in foreign elections from 1946 to 2000.

[Levin, Dov H. (7 September 2016)]

"Sure, the U.S. and Russia often meddle in foreign elections. Does it matter?"

''The Washington Post

''The Washington Post'' (also known as the ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'') is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C. It is the most widely circulated newspaper within the Washington metropolitan area and has a large nati ...

''. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

The Soviet Union ratified the

UN Charter

The Charter of the United Nations (UN) is the foundational treaty of the UN, an intergovernmental organization. It establishes the purposes, governing structure, and overall framework of the UN system, including its six principal organs: the ...

in 1945, the preeminent international law document, which legally bound the Soviet government to the Charter's provisions, including Article 2(4), which prohibits the threat or use of force in international relations, except in very limited circumstances. Therefore, any legal claim advanced to justify regime change by a foreign power carries a particularly heavy burden.

1921–1940: Interwar period

1920s

1921–1924: Mongolia

The

Mongolian Revolution of 1911

The Mongolian Revolution of 1911 (Mongol: Үндэсний эрх чөлөөний хувьсгал, , ''Ündèsnij èrx čölöönij xuv’sgal'') occurred when the region of Outer Mongolia declared its independence from the Manchu-led Qing Chi ...

saw

Mongolia

Mongolia; Mongolian script: , , ; lit. "Mongol Nation" or "State of Mongolia" () is a landlocked country in East Asia, bordered by Russia to the north and China to the south. It covers an area of , with a population of just 3.3 million, ...

declare independence from the

Qing dynasty

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing,, was a Manchu-led imperial dynasty of China and the last orthodox dynasty in Chinese history. It emerged from the Later Jin dynasty founded by the Jianzhou Jurchens, a Tungusic-speak ...

in China, ruled by

Bogd Khan

Bogd Khan, , ; ( – 20 May 1924) was the khan of the Bogd Khaganate from 1911 to 1924, following the state's ''de facto'' independence from the Qing dynasty of China after the Xinhai Revolution. Born in Tibet, he was the third most importa ...

. In 1912, the

Qing dynasty

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing,, was a Manchu-led imperial dynasty of China and the last orthodox dynasty in Chinese history. It emerged from the Later Jin dynasty founded by the Jianzhou Jurchens, a Tungusic-speak ...

collapsed into the

Republic of China

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the northeast ...

. In 1915, Russia and China signed the Kyatha agreement, making it autonomous. However, when the

Russian Civil War

, date = October Revolution, 7 November 1917 – Yakut revolt, 16 June 1923{{Efn, The main phase ended on 25 October 1922. Revolt against the Bolsheviks continued Basmachi movement, in Central Asia and Tungus Republic, the Far East th ...

broke out, China, working with Mongolian

aristocrats

Aristocracy (, ) is a form of government that places strength in the hands of a small, privileged ruling class, the aristocrats. The term derives from the el, αριστοκρατία (), meaning 'rule of the best'.

At the time of the word' ...

, retook Mongolia in 1919. At the same time the

Russian Civil War

, date = October Revolution, 7 November 1917 – Yakut revolt, 16 June 1923{{Efn, The main phase ended on 25 October 1922. Revolt against the Bolsheviks continued Basmachi movement, in Central Asia and Tungus Republic, the Far East th ...

raged on and the

White Army

The White Army (russian: Белая армия, Belaya armiya) or White Guard (russian: Бѣлая гвардія/Белая гвардия, Belaya gvardiya, label=none), also referred to as the Whites or White Guardsmen (russian: Бѣлогв� ...

were, by 1921, beginning to lose to the

Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, after ...

. One of the commanders,

Roman Ungern Von Sternberg

Nikolai Robert Maximilian Freiherr von Ungern-Sternberg (russian: link=no, Роман Фёдорович фон Унгерн-Штернберг, translit=Roman Fedorovich fon Ungern-Shternberg; 10 January 1886 – 15 September 1921), often refer ...

, saw this and decided to abandon the White Army with his forces. He led his army into Mongolia in 1920, and conquered it completely by February 1921, putting Bogd Khan back into power.

The

Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

had been worried about Sternberg and, at the request of the

Mongolian People's Party

The Mongolian People's Party (MPP) is a social democratic political party in Mongolia. It was founded as a communist party in 1920 by Mongolian revolutionaries and is the oldest political party in Mongolia.

The party played an important role i ...

, invaded Mongolia in August 1921 helping with the

Mongolian Revolution of 1921

The Mongolian Revolution of 1921 (Outer Mongolian Revolution of 1921, or People's Revolution of 1921) was a military and political event by which Mongolian revolutionaries, with the assistance of the Soviet Red Army, expelled Russian White Guar ...

. The Soviets moved from many directions and captured many locations in the country. Sternberg fought back and marched into the USSR but he was captured and killed by the Soviets on 15 September 1921. The Soviets kept Bogd Khan in power, as a

constitutional monarch

A constitutional monarchy, parliamentary monarchy, or democratic monarchy is a form of monarchy in which the monarch exercises their authority in accordance with a constitution and is not alone in decision making. Constitutional monarchies dif ...

, hoping to keep good relations with China, while continuing to occupy the country. However, when Bogd Khan died in 1924, the Mongolian Revolutionary government declared that no reincarnations shall be accepted and set up the

People's Republic of Mongolia

The Mongolian People's Republic ( mn, Бүгд Найрамдах Монгол Ард Улс, БНМАУ; , ''BNMAU''; ) was a socialist state which existed from 1924 to 1992, located in the historical region of Outer Mongolia in East Asia. It ...

which would exist in power until 1992.

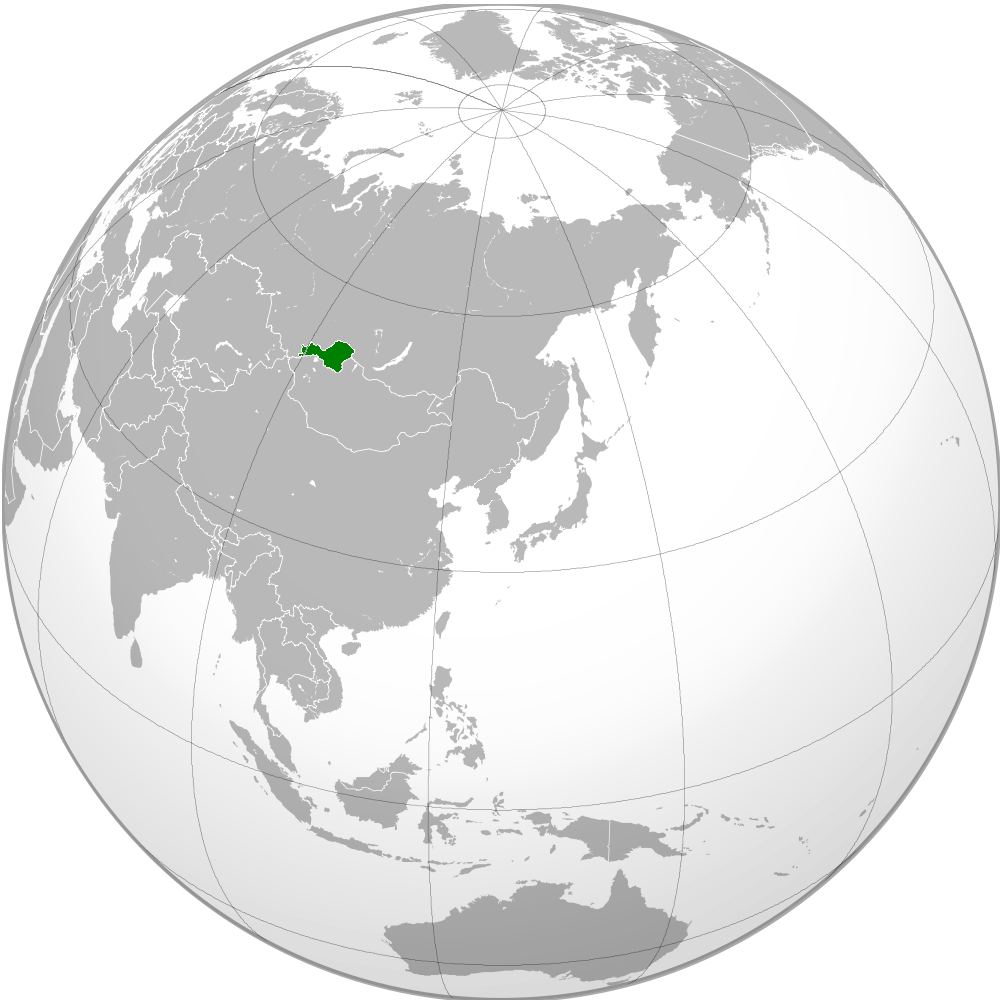

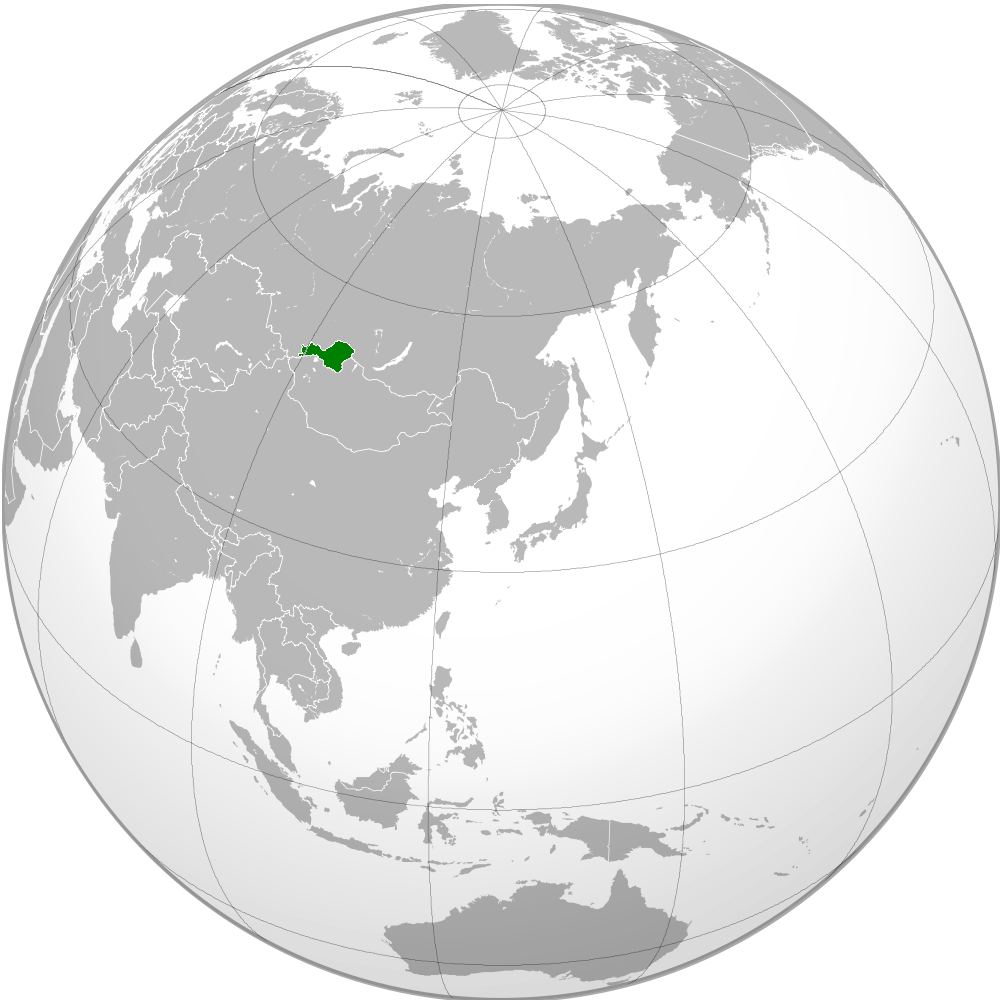

1929: Tannu Tuva

After the fall of the Qing Dynasty in the

1911 Revolution

The 1911 Revolution, also known as the Xinhai Revolution or Hsinhai Revolution, ended China's last imperial dynasty, the Manchu-led Qing dynasty, and led to the establishment of the Republic of China. The revolution was the culmination of a d ...

, the province of

Tannu Uriankhai

Tannu Uriankhai ( tyv, Таңды Урянхай, ; mn, Тагна Урианхай, Tagna Urianhai, ; ) is a historical region of the Mongol Empire (and its principal successor, the Yuan dynasty) and, later, the Qing dynasty. The territory of ...

became independent, and was then made a

protectorate

A protectorate, in the context of international relations, is a State (polity), state that is under protection by another state for defence against aggression and other violations of law. It is a dependent territory that enjoys autonomy over m ...

of the Russian empire. During the Russian Civil War, the Red Army created the

Tuvan People's Republic

The Tuvan People's Republic (TPR; tyv, Тыва Арат Республик, translit=Tywa Arat Respublik; Yanalif: ''Tьʙа Arat Respuʙlik'', ),) and abbreviated TAR. known as the Tannu Tuva People's Republic until 1926, was a partially rec ...

. It was located in between Mongolia and the USSR and was only recognized by the two countries. Their Prime Minister was

Donduk Kuular

Donduk Kuular ( tyv, Куулар Дондук, , 1888–1932) was a Tuvan monk, politician, and prime minister of the Tuvan People's Republic.

Born in Tannu Uriankhai during the rule of the Qing dynasty of China, Donduk was originally a Lamai ...

, a former

Lama

Lama (; "chief") is a title for a teacher of the Dharma in Tibetan Buddhism. The name is similar to the Sanskrit term ''guru'', meaning "heavy one", endowed with qualities the student will eventually embody. The Tibetan word "lama" means "hi ...

with many ties to the Lamas present in the country. He tried to put his country on a

Theocratic

Theocracy is a form of government in which one or more deities are recognized as supreme ruling authorities, giving divine guidance to human intermediaries who manage the government's daily affairs.

Etymology

The word theocracy originates fro ...

and

Nationalistic

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: T ...

path, tried to sow closer ties with Mongolia, and made

Buddhism

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and gra ...

the

state religion

A state religion (also called religious state or official religion) is a religion or creed officially endorsed by a sovereign state. A state with an official religion (also known as confessional state), while not secular state, secular, is not n ...

. He was also resistant to the

collectivization policies of the Soviet Union. This was alarming and irritating to

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secreta ...

, the Soviet Union's leader.

The Soviet Union would set the ground for a coup. They encouraged the "Revolutionary Union of Youth" movement, and educated many of them at

Communist University of the Toilers of the East

The Communist University of the Toilers of the East (KUTV) (russian: link=no, Коммунистический университет трудящихся Востока; also known as the Far East University) was a revolutionary training scho ...

. In January 1929, five youths educated at the school would launch a coup with Soviet support and depose Kuular, imprisoning and later executing him.

Salchak Toka

Salchak Kalbakkhorekovich Toka (russian: Салчак Калбакхорекович Тока, – 11 May 1973) was a Tuvan and later, Soviet politician. He was General Secretary of the Tuvinian department of the CPSU from 1944 to 1973; previou ...

would become the new head of the country. Under the new government, collectivization policies were implemented. A

purge

In history, religion and political science, a purge is a position removal or execution of people who are considered undesirable by those in power from a government, another organization, their team leaders, or society as a whole. A group undertak ...

was launched in the country against aristocrats,

Buddhists

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and gra ...

, intellectuals, and other political dissidents, which would also see the destruction of many

monasteries

A monastery is a building or complex of buildings comprising the domestic quarters and workplaces of monastics, monks or nuns, whether living in communities or alone (hermits). A monastery generally includes a place reserved for prayer which ...

.

1929: Afghanistan

After the

Third Anglo-Afghan War

The Third Anglo-Afghan War; fa, جنگ سوم افغان-انگلیس), also known as the Third Afghan War, the British-Afghan War of 1919, or in Afghanistan as the War of Independence, began on 6 May 1919 when the Emirate of Afghanistan inv ...

, the

Kingdom of Afghanistan

The Kingdom of Afghanistan ( ps, , Dǝ Afġānistān wākmanān; prs, پادشاهی افغانستان, Pādešāhī-ye Afġānistān) was a constitutional monarchy in Central Asia established in 1926 as a successor state to the Emirate of Af ...

had full independence from the

British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

, and could make their own

foreign relations

A state's foreign policy or external policy (as opposed to internal or domestic policy) is its objectives and activities in relation to its interactions with other states, unions, and other political entities, whether bilaterally or through mu ...

.

Amanullah Khan

Ghazi Amanullah Khan (Pashto and Dari: ; 1 June 1892 – 25 April 1960) was the sovereign of Afghanistan from 1919, first as Emir and after 1926 as King, until his abdication in 1929. After the end of the Third Anglo-Afghan War in August 1919, ...

, the king of Afghanistan, made

relations with the USSR, among many other countries, such as signing an agreement of neutrality. There had also been another treaty signed that gave territory to Afghanistan on the condition that they stop

Basmachi raids into the USSR. As his reign continued, Amanullah Khan became less popular, and in November 1928 rebels rose up in the east of the country. The

Saqqawists

The Saqqawists (Pashto:سقاویان prs, سقاویها ''Saqāwīhā'') were an armed group in the Kingdom of Afghanistan who were active from 1924 to 1931. They were led by Habibullāh Kalakāni, and in January 1929, they managed to take ...

allowed Basmachi rebels from the Soviet Union to operate inside the country after coming to power. The Soviet Union sent 1,000 troops into Afghanistan to support Amanullah Khan.

When Amanullah fled the country, the Red Army withdrew from Afghanistan.

Despite the Soviet withdrawal, the Saqqawists would be defeated later, in 1929.

1930s

1933–1934: Xinjiang

In 1934,

Ma Zhongying's troops, supported by the

Kuomintang government of the

Republic of China

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the northeast ...

, were on the verge of defeating the Soviet client

Sheng Shicai

Sheng Shicai (; 3 December 189513 July 1970) was a Chinese warlord who ruled Xinjiang from 1933 to 1944. Sheng's rise to power started with a coup d'état in 1933 when he was appointed the ''duban'' or Military Governor of Xinjiang. His rule o ...

during the

Battle of Ürümqi in the

Kumul Rebellion

The Kumul Rebellion (, "Hami Uprising") was a rebellion of Kumulik Uyghurs from 1931 to 1934 who conspired with Hui Chinese Muslim Gen. Ma Zhongying to overthrow Jin Shuren, governor of Xinjiang. The Kumul Uyghurs were loyalists of the Kumul ...

. As a

Hui

The Hui people ( zh, c=, p=Huízú, w=Hui2-tsu2, Xiao'erjing: , dng, Хуэйзў, ) are an East Asian ethnoreligious group predominantly composed of Chinese-speaking adherents of Islam. They are distributed throughout China, mainly in the n ...

(

Chinese Muslim

Islam has been practiced in China since the 7th century CE.. Muslims are a minority group in China, representing 1.6-2 percent of the total population (21,667,000- 28,210,795) according to various estimates. Though Hui Muslims are the most nume ...

), he had earlier attended the

Whampoa Military Academy

The Republic of China Military Academy () is the service academy for the army of the Republic of China, located in Fengshan District, Kaohsiung. Previously known as the the military academy produced commanders who fought in many of China ...

in

Nanjing

Nanjing (; , Mandarin pronunciation: ), alternately romanized as Nanking, is the capital of Jiangsu province of the People's Republic of China. It is a sub-provincial city, a megacity, and the second largest city in the East China region. T ...

in 1929, when it was run by

Chiang Kai-shek

Chiang Kai-shek (31 October 1887 – 5 April 1975), also known as Chiang Chung-cheng and Jiang Jieshi, was a Chinese Nationalist politician, revolutionary, and military leader who served as the leader of the Republic of China (ROC) from 1928 ...

, who was also the head of the

Kuomintang

The Kuomintang (KMT), also referred to as the Guomindang (GMD), the Nationalist Party of China (NPC) or the Chinese Nationalist Party (CNP), is a major political party in the Republic of China, initially on the Chinese mainland and in Tai ...

and leader of China.

/sup> He was then sent back to Gansu

Gansu (, ; alternately romanized as Kansu) is a province in Northwest China. Its capital and largest city is Lanzhou, in the southeast part of the province.

The seventh-largest administrative district by area at , Gansu lies between the Tibet ...

after graduating from the academy and fought in the Kumul Rebellion where, with the tacit support of the Kuomintang government of China, he tried to overthrow the pro-Soviet provincial government first led by Governor Jin Shuren

Jin Shuren (; c. 1883–1941) was a Chinese Xinjiang clique warlord who served as Governor of Xinjiang between 1928 and 1933.

Biography

Jin Shuren was born in Yongjing, Hezhou, Gansu. He graduated at the Gansu provincial academy and ...

, and then Sheng Shicai. Ma invaded Xinjiang

Xinjiang, SASM/GNC: ''Xinjang''; zh, c=, p=Xīnjiāng; formerly romanized as Sinkiang (, ), officially the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (XUAR), is an autonomous region of the People's Republic of China (PRC), located in the northwest ...

in support of Kumul Khanate

The Kumul Khanate was a semi-autonomous feudal Turkic khanate (equivalent to a banner in Mongolia) within the Qing dynasty and then the Republic of China until it was abolished by Xinjiang governor Jin Shuren in 1930. The Khanate was located in ...

loyalists and received official approval and designation from the Kuomintang as the 36th Division.

In late 1933, the

In late 1933, the Han Chinese

The Han Chinese () or Han people (), are an East Asian ethnic group native to China. They constitute the world's largest ethnic group, making up about 18% of the global population and consisting of various subgroups speaking distinctive va ...

provincial commander General Zhang Peiyuan and his army defected from the provincial government side to Zhongying's side and joined him in waging war against Jin Shuren's provincial government.

In 1934, two brigades of about 7,000 Soviet GPU

A graphics processing unit (GPU) is a specialized electronic circuit designed to manipulate and alter memory to accelerate the creation of images in a frame buffer intended for output to a display device. GPUs are used in embedded systems, mobi ...

troops, backed by tanks, airplanes and artillery with mustard gas

Mustard gas or sulfur mustard is a chemical compound belonging to a family of cytotoxic and blister agents known as mustard agents. The name ''mustard gas'' is technically incorrect: the substance, when dispersed, is often not actually a gas, b ...

, crossed the border to assist Sheng Shicai in gaining control of Xinjiang. The brigades were named "Altayiiskii" and "Tarbakhataiskii". /sup> Sheng's Manchurian army was being severely beaten by an alliance of the Han Chinese

The Han Chinese () or Han people (), are an East Asian ethnic group native to China. They constitute the world's largest ethnic group, making up about 18% of the global population and consisting of various subgroups speaking distinctive va ...

army led by general Zhang Peiyuan, and the 36th Division led by Zhongying, /sup> who fought under the banner of the Kuomintang

The Kuomintang (KMT), also referred to as the Guomindang (GMD), the Nationalist Party of China (NPC) or the Chinese Nationalist Party (CNP), is a major political party in the Republic of China, initially on the Chinese mainland and in Tai ...

Republic of China

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the northeast ...

government. The joint Soviet-White Russian force was called "The Altai Volunteers". Soviet soldiers disguised themselves in uniforms lacking markings, and were dispersed among the White Russians. /sup>

Despite his early successes, Zhang's forces were overrun at Kulja and Chuguchak

TachengThe official spelling according to (), as the official romanized name, also transliterated from Mongolian as Qoqak, is a county-level city (1994 est. pop. 56,400) and the administrative seat of Tacheng Prefecture, in northern Ili Kazakh A ...

, and he committed suicide after the battle at Muzart Pass to avoid capture.

Even though the Soviets were superior to the 36th Division in both manpower

Human resources (HR) is the set of people who make up the workforce of an organization, business sector, industry, or economy. A narrower concept is human capital, the knowledge and skills which the individuals command. Similar terms include ...

and technology, they were held off for weeks and took severe casualties. The 36th Division managed to halt the Soviet forces from supplying Sheng with military equipment. Chinese Muslim troops led by Ma Shih-ming held off the superior Red Army forces armed with machine guns, tanks, and planes for about 30 days. /sup>

When reports that the National Revolutionary Army

The National Revolutionary Army (NRA; ), sometimes shortened to Revolutionary Army () before 1928, and as National Army () after 1928, was the military arm of the Kuomintang (KMT, or the Chinese Nationalist Party) from 1925 until 1947 in China ...

had defeated and killed the Soviets reached Chinese prisoners in Ürümqi

Ürümqi ( ; also spelled Ürümchi or without umlauts), formerly known as Dihua (also spelled Tihwa), is the capital of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region in the far northwest of the People's Republic of China. Ürümqi developed its ...

, they were reportedly so jubilant that they jumped around in their cells. 0/sup>

Ma Hushan, Deputy Divisional Commander of the 36th Division, became well known for victories over Russian forces during the invasion. 1/sup>

Chiang Kai-shek

Chiang Kai-shek (31 October 1887 – 5 April 1975), also known as Chiang Chung-cheng and Jiang Jieshi, was a Chinese Nationalist politician, revolutionary, and military leader who served as the leader of the Republic of China (ROC) from 1928 ...

was ready to send Huang Shaohong and his expeditionary force which he assembled to assist Zhongying against Sheng, but when Chiang heard about the Soviet invasion, he decided to withdraw to avoid an international incident if his troops directly engaged the Soviets. 2/sup>

1936–1939: Spain

The newly created Second Spanish Republic

The Spanish Republic (), commonly known as the Second Spanish Republic (), was the form of government in Spain from 1931 to 1939. The Republic was proclaimed on 14 April 1931, after the deposition of Alfonso XIII, King Alfonso XIII, and was di ...

became tense with political divisions between right- and left-wing politics

Left-wing politics describes the range of Ideology#Political%20ideologies, political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy. Left-wing politics typically in ...

. The 1936 Spanish general election would see the left wing coalition, called the Popular Front

A popular front is "any coalition of working-class and middle-class parties", including liberal and social democratic ones, "united for the defense of democratic forms" against "a presumed Fascist assault".

More generally, it is "a coalition ...

, win a narrow majority. As a result, the right wing, known as Falange

The Falange Española Tradicionalista y de las Juntas de Ofensiva Nacional Sindicalista (FET y de las JONS; ), frequently shortened to just "FET", was the sole legal party of the Francoist regime in Spain. It was created by General Francisco F ...

, launched a coup against the Republic, and while they would take much territory, they would fail at taking over Spain completely, beginning the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebelión, lin ...

. There were two factions in the war: the right wing Nationalists

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: The ...

, which included the Fascist

Fascism is a far-right, Authoritarianism, authoritarian, ultranationalism, ultra-nationalist political Political ideology, ideology and Political movement, movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and pol ...

Falange

The Falange Española Tradicionalista y de las Juntas de Ofensiva Nacional Sindicalista (FET y de las JONS; ), frequently shortened to just "FET", was the sole legal party of the Francoist regime in Spain. It was created by General Francisco F ...

, Monarchists

Monarchism is the advocacy of the system of monarchy or monarchical rule. A monarchist is an individual who supports this form of government independently of any specific monarch, whereas one who supports a particular monarch is a royalist. ...

, Traditionalists, Carlists, wealthy landowners, and Conservatives

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

, who would eventually come to be led by Francisco Franco

Francisco Franco Bahamonde (; 4 December 1892 – 20 November 1975) was a Spanish general who led the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalist forces in overthrowing the Second Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War ...

, and the left wing Republicans, which included Anarchists

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not necessari ...

, Socialists

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the eco ...

, Basque separatists

Basque nationalism ( eu, eusko abertzaletasuna ; es, nacionalismo vasco; french: nationalisme basque) is a form of nationalism that asserts that Basques, an ethnic group indigenous to the western Pyrenees, are a nation and promotes the poli ...

, Catalan separatists, Liberals, and Communists

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a so ...

.

The Civil War would gain much international attention and both sides would gain foreign support through both volunteers and direct involvement. Both

The Civil War would gain much international attention and both sides would gain foreign support through both volunteers and direct involvement. Both Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

and Fascist Italy gave overt support to the Nationalists. At the time, the USSR had an official policy of non-intervention, but wanted to counter Germany and Italy. Stalin worked around the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

's embargo

Economic sanctions are commercial and financial penalties applied by one or more countries against a targeted self-governing state, group, or individual. Economic sanctions are not necessarily imposed because of economic circumstances—they m ...

and provided arms

Arms or ARMS may refer to:

*Arm or arms, the upper limbs of the body

Arm, Arms, or ARMS may also refer to:

People

* Ida A. T. Arms (1856–1931), American missionary-educator, temperance leader

Coat of arms or weapons

*Armaments or weapons

**Fi ...

to the Republicans and, unlike Germany and Italy, did this covertly. Arms shipment was usually slow and ineffective and many weapons were lost, but the Soviets would end up evading detection of the Nationalists by using false flags. Despite Stalin's interest in aiding the Republicans, the quality of arms was inconsistent. Many rifles and field guns provided were old, obsolete or otherwise of limited use, (some dated back to the 1860s) but the T-26

The T-26 tank was a Soviet light tank used during many conflicts of the Interwar period and in World War II. It was a development of the British Vickers 6-Ton tank and was one of the most successful tank designs of the 1930s until its light ...

and BT-5

The BT tanks (russian: Быстроходный танк/БТ, translit=Bystrokhodnyy tank, lit. "fast moving tank" or "high-speed tank") were a series of Soviet light tanks produced in large numbers between 1932 and 1941. They were lightly arm ...

tanks were modern and effective in combat.[Payne (2004). pp. 156–157.] The Soviet Union supplied aircraft that were in current service with their own forces but the aircraft provided by Germany to the Spanish Nationalist Air Force proved superior by the end of the war.[Beevor (2006). pp. 152–153.] The USSR sent 2,000–3,000 military advisers to Spain, and while the Soviet commitment of troops was fewer than 500 men at a time, Soviet volunteers often operated Soviet-made tanks and aircraft, particularly at the beginning of the war.[Thomas (1961). p. 637.] The Republic paid for Soviet arms with official Bank of Spain

The Bank of Spain ( es, link=no, Banco de España) is the central bank of Spain. Established in Madrid in 1782 by Charles III of Spain, Charles III, today the bank is a member of the European System of Central Banks and is also Spain's national ...

gold reserves, 176 tonnes of which was transferred through France and 510 directly to Russia which was called Moscow gold

The Moscow Gold ( es, Oro de Moscú), or alternatively Gold of the Republic ( es, Oro de la República), was 510 tonnes of gold, corresponding to 72.6% of the total gold reserves of the Bank of Spain, that were transferred from their original ...

. At the same time, the Soviet Union directed Communist parties around the world to organize and recruit the International Brigades

The International Brigades ( es, Brigadas Internacionales) were military units set up by the Communist International to assist the Popular Front government of the Second Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War. The organization existed f ...

.

At the same time, Stalin tried to take power within the Republicans. There were many anti-Stalin and anti-Soviet factions in the Republicans, such as Anarchists

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not necessari ...

and Trotyskyists. Stalin encouraged NKVD (People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs) activity inside of the Republicans and Spain.

Catalan Trotskyist Andreu Nin

Andreu Nin Pérez (4 February 1892 – 20 June 1937) was a Spanish communist politician, translator and publicist. In 1937, Nin and the rest of the POUM leadership were arrested by the Moscow-oriented government of the Second Spanish Republi ...

, socialist journalist Mark Rein, left-wing academic José Robles, and others were assassinated in operations in Spain led by many spies and Stalinists

Stalinism is the means of governing and Marxist-Leninist policies implemented in the Soviet Union from 1927 to 1953 by Joseph Stalin. It included the creation of a one-party totalitarian police state, rapid industrialization, the theory ...

such as Vittorio Vidali

Vittorio Vidali (27 September 1900 – 9 November 1983), also known as Vittorio Vidale, Enea Sormenti, Jacobo Hurwitz Zender, Carlos Contreras, and "Comandante Carlos", was an Italian communist. After being expelled from Italy with the ris ...

("Comandante Contreras"), Iosif Grigulevich

Iosif Romualdovich Grigulevich (russian: Иосиф Ромуальдович Григулевич; May 5, 1913 – June 2, 1988) was a Soviet secret police (NKVD) operative active between 1937 and 1953, when he played a role in assassination plots ...

, Mikhail Koltsov

Mikhail Efimovich Koltsov (russian: Михаи́л Ефи́мович Кольцо́в) (The record of the birth of Moisey Fridlyand in the metric book of the Kiev rabbinate for 1898 ( ЦГИАК Украины. Ф. 1164. Оп. 1. Д. 442. Л. 13 ...

and, most prominently, Aleksandr Mikhailovich Orlov

Alexander Mikhailovich Orlov ( be, Аляксандар Мікалаевіч Арлоў, born Leiba Lazarevich Feldbin, later Lev Lazarevich Nikolsky, and in the US assuming the name of Igor Konstantinovich Berg; 21 August 1895 – 25 March 1 ...

. The NKVD also targeted Nationalists and others they saw as politically problematic to their goals.

The Republicans eventually broke out into infighting between the communists

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a so ...

and anarchists

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not necessari ...

, as both groups attempted to form their own governments. The Nationalists, on the other hand, were much more unified than the Republicans, and Franco had been able to take most of Spain's territory, including Catalonia

Catalonia (; ca, Catalunya ; Aranese Occitan: ''Catalonha'' ; es, Cataluña ) is an autonomous community of Spain, designated as a ''nationality'' by its Statute of Autonomy.

Most of the territory (except the Val d'Aran) lies on the north ...

, an important area of left wing support and, with the collapse of Madrid, the war was over with a Nationalist victory.

1939–1940: Finland

On 30 November 1939, the Soviet Union invaded Finland, three months after the outbreak of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, and ended three and a half months later with the Moscow Peace Treaty

The Moscow Peace Treaty was signed by Finland and the Soviet Union on 12 March 1940, and the ratifications were exchanged on 21 March. It marked the end of the 105-day Winter War, upon which Finland ceded border areas to the Soviet Union. The ...

on 13 March 1940. The League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

deemed the attack illegal and expelled the Soviet Union from the organisation. The conflict began after the Soviets sought to obtain Finnish territory, demanding, among other concessions, that Finland cede substantial border territories in exchange for land elsewhere, claiming security reasons—primarily the protection of

The conflict began after the Soviets sought to obtain Finnish territory, demanding, among other concessions, that Finland cede substantial border territories in exchange for land elsewhere, claiming security reasons—primarily the protection of Leningrad

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

, 32 km (20 mi) from the Finnish border. Finland refused, so the USSR invaded the country. Many sources conclude that the Soviet Union had intended to conquer all of Finland, and use the establishment of the puppet Communist Finnish Democratic Republic

The Finnish Democratic Republic ( fi, Suomen kansanvaltainen tasavalta or ''Suomen kansantasavalta'', sv, Demokratiska Republiken Finland, Russian: ''Финляндская Демократическая Республика''), also known as t ...

and the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact

, long_name = Treaty of Non-Aggression between Germany and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

, image = Bundesarchiv Bild 183-H27337, Moskau, Stalin und Ribbentrop im Kreml.jpg

, image_width = 200

, caption = Stalin and Ribbentrop shaking ...

's secret protocols as evidence of this. 8/sup> Finland repelled Soviet attacks for more than two months and inflicted substantial losses on the invaders while temperatures ranged as low as −43 °C (−45 °F). After the Soviet military reorganised and adopted different tactics, they renewed their offensive in February and overcame Finnish defences.

Hostilities ceased in March 1940 with the signing of the Moscow Peace Treaty

The Moscow Peace Treaty was signed by Finland and the Soviet Union on 12 March 1940, and the ratifications were exchanged on 21 March. It marked the end of the 105-day Winter War, upon which Finland ceded border areas to the Soviet Union. The ...

. Finland ceded 11 percent of its territory, representing 30 percent of its economy to the Soviet Union. Soviet losses were heavy, and the country's international reputation suffered. Soviet gains exceeded their pre-war demands and the USSR received substantial territory along Lake Ladoga and in northern Finland. Finland retained its sovereignty

Sovereignty is the defining authority within individual consciousness, social construct, or territory. Sovereignty entails hierarchy within the state, as well as external autonomy for states. In any state, sovereignty is assigned to the perso ...

and enhanced its international reputation. The poor performance of the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, after ...

encouraged Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

to think that an attack on the Soviet Union would be successful and confirmed negative Western opinions of the Soviet military. After 15 months of Interim Peace

The Interim Peace ( fi, Välirauha, sv, Mellanfreden) was a short period in the history of Finland during the Second World War. The term is used for the time between the Winter War and the Continuation War, lasting a little over 15 months, from 1 ...

, in June 1941, Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

commenced Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa (german: link=no, Unternehmen Barbarossa; ) was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and many of its Axis allies, starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during the Second World War. The operation, code-named after ...

and the Soviet-Finnish theater of World War II, also known as the Continuation War

The Continuation War, also known as the Second Soviet-Finnish War, was a conflict fought by Finland and Nazi Germany against the Soviet Union from 1941 to 1944, as part of World War II.; sv, fortsättningskriget; german: Fortsetzungskrieg. A ...

, flared up again.

1940s

1940: Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania

The Soviet Union occupied the

The Soviet Union occupied the Baltic states

The Baltic states, et, Balti riigid or the Baltic countries is a geopolitical term, which currently is used to group three countries: Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. All three countries are members of NATO, the European Union, the Eurozone, ...

under the auspices

Augury is the practice from ancient Roman religion of interpreting omens from the observed behavior of birds. When the individual, known as the augur, interpreted these signs, it is referred to as "taking the auspices". "Auspices" (Latin ''au ...

of the 1939 Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact

, long_name = Treaty of Non-Aggression between Germany and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

, image = Bundesarchiv Bild 183-H27337, Moskau, Stalin und Ribbentrop im Kreml.jpg

, image_width = 200

, caption = Stalin and Ribbentrop shaking ...

in June 1940. They were then incorporated into the Soviet Union as constituent republics in August 1940, though most Western powers

The Western world, also known as the West, primarily refers to the various nations and states in the regions of Europe, North America, and Oceania. never recognized their incorporation.Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

attacked the Soviet Union and, within weeks, occupied the Baltic territories. In July 1941, the Third Reich incorporated the Baltic territory into its ''Reichskommissariat Ostland

The Reichskommissariat Ostland (RKO) was established by Nazi Germany in 1941 during World War II. It became the civilian occupation regime in Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and the western part of Byelorussian SSR. German planning documents initia ...

''. As a result of the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, after ...

's Baltic Offensive of 1944, the Soviet Union recaptured most of the Baltic states and trapped the remaining German forces in the Courland pocket

The Courland Pocket (Blockade of the Courland army group), (german: Kurland-Kessel)/german: Kurland-Brückenkopf (Courland Bridgehead), lv, Kurzemes katls (Courland Cauldron) or ''Kurzemes cietoksnis'' (Courland Fortress)., group=lower-alpha ...

until their formal surrender in May 1945. The Soviet "annexation occupation" (german: link=no, Annexionsbesetzung) or occupation ''sui generis

''Sui generis'' ( , ) is a Latin phrase that means "of its/their own kind", "in a class by itself", therefore "unique".

A number of disciplines use the term to refer to unique entities. These include:

* Biology, for species that do not fit in ...

''[ Mälksoo (2003), p. 193.] of the Baltic states lasted until August 1991, when the three countries regained their independence.

The Baltic states themselves,[The Occupation of Latvia](_blank)

at Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Latvia the United States and its courts of law, the European Parliament

The European Parliament (EP) is one of the legislative bodies of the European Union and one of its seven institutions. Together with the Council of the European Union (known as the Council and informally as the Council of Ministers), it adopts ...

,[Motion for a resolution on the Situation in Estonia](_blank)

by the European Parliament

The European Parliament (EP) is one of the legislative bodies of the European Union and one of its seven institutions. Together with the Council of the European Union (known as the Council and informally as the Council of Ministers), it adopts ...

, B6-0215/2007, 21 May 2007

passed 24.5.2007

Retrieved 1 January 2010. the European Court of Human Rights

The European Court of Human Rights (ECHR or ECtHR), also known as the Strasbourg Court, is an international court of the Council of Europe which interprets the European Convention on Human Rights. The court hears applications alleging that a ...

United Nations Human Rights Council

The United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC), CDH is a United Nations body whose mission is to promote and protect human rights around the world. The Council has 47 members elected for staggered three-year terms on a regional group basis. ...

Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact

, long_name = Treaty of Non-Aggression between Germany and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

, image = Bundesarchiv Bild 183-H27337, Moskau, Stalin und Ribbentrop im Kreml.jpg

, image_width = 200

, caption = Stalin and Ribbentrop shaking ...

. There followed occupation by Nazi Germany from 1941 to 1944 and then again occupation by the Soviet Union from 1944 to 1991.[The World Book Encyclopedia ] This policy of non-recognition has given rise to the principle of legal continuity of the Baltic states

The three Baltic countries, or the Baltic states – Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania – are held to have continued as legal entities under international law#Ziemele2005, Ziemele (2005). p118. while under the Soviet Union, Soviet Occupation of the ...

, which holds that ''de jure

In law and government, ''de jure'' ( ; , "by law") describes practices that are legally recognized, regardless of whether the practice exists in reality. In contrast, ("in fact") describes situations that exist in reality, even if not legally ...

'', or as a matter of law, the Baltic states had remained independent states under illegal occupation throughout the period from 1940 to 1991.[David James Smith, ''Estonia: independence and European integration'', Routledge, 2001, , pXIX]perestroika

''Perestroika'' (; russian: links=no, перестройка, p=pʲɪrʲɪˈstrojkə, a=ru-perestroika.ogg) was a political movement for reform within the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) during the late 1980s widely associated wit ...

in 1989, the Soviet Union condemned the 1939 secret protocol between Germany and itself.[The Forty-Third Session of the UN Sub-Commission](_blank)

at Google Scholar However, the Soviet Union never formally acknowledged its presence in the Baltics as an occupation or that it annexed these states[ Marek (1968). p. 396. "Insofar as the Soviet Union claims that they are not directly annexed territories but autonomous bodies with a legal will of their own, they (The Baltic SSRs) must be considered puppet creations, exactly in the same way in which the Protectorate or Italian-dominated Albania have been classified as such. These puppet creations have been established on the territory of the independent Baltic states; they cover the same territory and include the same population."] and considered the Estonian, Latvian and Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic

The Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic (Lithuanian SSR; lt, Lietuvos Tarybų Socialistinė Respublika; russian: Литовская Советская Социалистическая Республика, Litovskaya Sovetskaya Sotsialistiche ...

s as three of its constituent republics. On the other hand, the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Russian SFSR or RSFSR ( rus, Российская Советская Федеративная Социалистическая Республика, Rossíyskaya Sovétskaya Federatívnaya Soci ...

recognized in 1991 that the events of 1940 were "annexation . Nationalist-patriotic[cf. e.g. Boris Sokolov's article offering an overvie]

Эстония и Прибалтика в составе СССР (1940–1991) в российской историографии

(Estonia and the Baltic countries in the USSR (1940–1991) in Russian historiography). Accessed 30 January 2011. Russian historiography

Historiography is the study of the methods of historians in developing history as an academic discipline, and by extension is any body of historical work on a particular subject. The historiography of a specific topic covers how historians ha ...

and school textbooks continue to maintain that the Baltic states voluntarily joined the Soviet Union after their peoples all carried out socialist revolution

Revolutionary socialism is a political philosophy, doctrine, and tradition within socialism that stresses the idea that a social revolution is necessary to bring about structural changes in society. More specifically, it is the view that revoluti ...

s independent of Soviet influence. The post-Soviet government of the Russian Federation

The Government of Russia exercises executive power in the Russia, Russian Federation. The members of the government are the Prime Minister of Russia, prime minister, the Deputy Chairman of the Government, deputy prime ministers, and the federa ...

and its state officials insist that incorporation of the Baltic states was in accordance with international law and gained de jure

In law and government, ''de jure'' ( ; , "by law") describes practices that are legally recognized, regardless of whether the practice exists in reality. In contrast, ("in fact") describes situations that exist in reality, even if not legally ...

recognition by the agreements made in the February 1945 Yalta

Yalta (: Я́лта) is a resort city on the south coast of the Crimean Peninsula surrounded by the Black Sea. It serves as the administrative center of Yalta Municipality, one of the regions within Crimea. Yalta, along with the rest of Crimea ...

and the July–August 1945 Potsdam conference

The Potsdam Conference (german: Potsdamer Konferenz) was held at Potsdam in the Soviet occupation zone from July 17 to August 2, 1945, to allow the three leading Allies to plan the postwar peace, while avoiding the mistakes of the Paris Pe ...

s and by the 1975 Helsinki Accords

The Helsinki Final Act, also known as Helsinki Accords or Helsinki Declaration was the document signed at the closing meeting of the third phase of the Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe (CSCE) held in Helsinki, Finland, between ...

,[''МИД РФ: Запад признавал Прибалтику частью СССР''](_blank)

grani.ru, May 2005

Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Russia)

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation (MFA Russia; russian: Министерство иностранных дел Российской Федерации, МИД РФ) is the central government institution charged with lea ...

, 7 May 2005[ Khudoley (2008), '' Soviet foreign policy during the Cold War, The Baltic factor'', p. 90.] However, Russia agreed to Europe's demand to "assist persons deported from the occupied Baltic states" upon joining the Council of Europe

The Council of Europe (CoE; french: Conseil de l'Europe, ) is an international organisation founded in the wake of World War II to uphold European Convention on Human Rights, human rights, democracy and the Law in Europe, rule of law in Europe. ...

in 1996.[as described in Resolution 1455 (2005), Honouring of obligations and commitments by the Russian Federation](_blank)

, at the CoE Parliamentary site, retrieved 6 December 2009 Additionally, when the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic signed a separate treaty with Lithuania in 1991, it acknowledged that the 1940 annexation as a violation of Lithuanian sovereignty and recognized the ''de jure'' continuity of the Lithuanian state.[Treaty between the Russian Soviet Federated Socialist Republic and the Republic of Lithuania on the Basis for Relations between States](_blank)

Most Western governments maintained that Baltic sovereignty had not been legitimately overriddendissolution of the Soviet Union

The dissolution of the Soviet Union, also negatively connoted as rus, Разва́л Сове́тского Сою́за, r=Razvál Sovétskogo Soyúza, ''Ruining of the Soviet Union''. was the process of internal disintegration within the Sov ...

. The Russian Armed Forces

The Armed Forces of the Russian Federation (, ), commonly referred to as the Russian Armed Forces, are the military forces of Russia. In terms of active-duty personnel, they are the world's fifth-largest military force, with at least two m ...

started to withdraw its troops from the Baltics (starting from Lithuania) in August 1993. The full withdrawal of troops deployed by Moscow ended in August 1994. Russia officially ended its military presence in the Baltics in August 1998 by decommissioning the Skrunda-1 radar station in Latvia. The dismantled installations were repatriated to Russia and the site returned to Latvian control, with the last Russian soldier leaving Baltic soil in October 1999.

1941–1949: World War II, formation of East Bloc, creation of Soviet satellite states, last years of Stalin's rule

The Soviet Union policy during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

was neutral until August 1939, followed by friendly relations with Germany to carve up Eastern Europe. The USSR helped supply oil and munitions to Germany as its armies rolled across Western Europe in May–June 1940. Despite repeated warnings, Stalin refused to believe that Hitler was planning an all-out war on the USSR; he was stunned and temporarily helpless when Hitler invaded in June 1941. Stalin quickly came to terms with Britain and the United States, cemented through a series of summit meetings. The two countries supplied war materials in large quantity through Lend Lease

Lend-Lease, formally the Lend-Lease Act and introduced as An Act to Promote the Defense of the United States (), was a policy under which the United States supplied the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union and other Allied nations with food, oil, ...

.Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

at the Tehran Conference

The Tehran Conference (codenamed Eureka) was a strategy meeting of Joseph Stalin, Franklin Roosevelt, and Winston Churchill from 28 November to 1 December 1943, after the Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran. It was held in the Soviet Union's embassy i ...

in November 1943 and the Yalta Conference

The Yalta Conference (codenamed Argonaut), also known as the Crimea Conference, held 4–11 February 1945, was the World War II meeting of the heads of government of the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union to discuss the post ...

in February 1945, the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

entered World War II's Pacific Theater

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the continen ...

within three months of the end of the war in Europe. The invasion began on 9 August 1945, exactly three months after the German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

** Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

surrender

Surrender may refer to:

* Surrender (law), the early relinquishment of a tenancy

* Surrender (military), the relinquishment of territory, combatants, facilities, or armaments to another power

Film and television

* ''Surrender'' (1927 film), an ...

on May 8 (9 May, 0:43 Moscow Time

Moscow Time (MSK, russian: моско́вское вре́мя) is the time zone for the city of Moscow, Russia, and most of western Russia, including Saint Petersburg. It is the second-westernmost of the eleven time zones of Russia. It has b ...

). Although the commencement of the invasion fell between the American atomic bombing of Hiroshima

The United States detonated two atomic bombs over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on 6 and 9 August 1945, respectively. The two bombings killed between 129,000 and 226,000 people, most of whom were civilians, and remain the onl ...

, on 6 August, and only hours before the Nagasaki bombing

The United States detonated two atomic bombs over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on 6 and 9 August 1945, respectively. The two bombings killed between 129,000 and 226,000 people, most of whom were civilians, and remain the onl ...

on 9 August, the timing of the invasion had been planned well in advance and was determined by the timing of the agreements at Tehran and Yalta, the long-term buildup of Soviet forces in the Far East since Tehran, and the date of the German surrender some three months earlier; on 3 August, Marshal Vasilevsky reported to Premier Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secreta ...

that, if necessary, he could attack on the morning of 5 August. At 11 pm Trans-Baikal (UTC+10

UTC+10:00 is an identifier for a time offset from UTC of +10:00. This time is used in:

As standard time (year-round)

''Principal cities: Brisbane, Gold Coast, Vladivostok, Khabarovsk, Port Moresby, Dededo, Saipan''

North Asia

*Russia – ...

) time on 8 August 1945, Soviet foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov

Vyacheslav Mikhaylovich Molotov. ; (;. 9 March Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O._S._25_February.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O. S. 25 February">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dat ...

informed Japanese ambassador Naotake Satō

was a Japanese diplomat and politician. He was born in Osaka, graduated from the Tokyo Higher Commercial School (東京高等商業学校, ''Tōkyō Kōtō Shōgyō Gakkō'', now Hitotsubashi University) in 1904, attended the consul course of ...

that the Soviet Union had declared war on Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

, and that from 9 August the Soviet government would consider itself to be at war with Japan.["Soviet Declaration of War on Japan"](_blank)

8 August 1945. (Avalon Project

The Avalon Project is a digital library of documents relating to law, history and diplomacy. The project is part of the Yale Law School Lillian Goldman Law Library.

The project contains online electronic copies of documents dating back to the be ...

at Yale University

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the wo ...

)

1940s

1941: Iran

The British Commonwealth

The Commonwealth of Nations, simply referred to as the Commonwealth, is a political association of 56 member states, the vast majority of which are former territories of the British Empire. The chief institutions of the organisation are the Co ...

and the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

invaded Pahlavi Iran

The Imperial State of Iran ( fa, کشور شاهنشاهی ایران, ), also known as the Imperial State of Persia, was the official name of the Iranian state under the rule of the Pahlavi dynasty.

It was formed in 1925 and lasted until 197 ...

jointly in 1941 during the Second World War. The invasion lasted from 25 August to 17 September 1941 and was codenamed Operation Countenance. Its purpose was to secure Iranian oil field

A petroleum reservoir or oil and gas reservoir is a subsurface accumulation of hydrocarbons contained in porous or fractured rock formations.

Such reservoirs form when kerogen (ancient plant matter) is created in surrounding rock by the presence ...

s and ensure Allied

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

supply line

Supply may refer to:

*The amount of a resource that is available

**Supply (economics), the amount of a product which is available to customers

**Materiel, the goods and equipment for a military unit to fulfill its mission

*Supply, as in confidenc ...

s (see the Persian Corridor

The Persian Corridor was a supply route through Iran into Azerbaijan SSR, Soviet Azerbaijan by which British aid and American Lend-Lease supplies were transferred to the Soviet Union during World War II. Of the 17.5 million long tons of U.S. Len ...

) for the USSR, fighting against Axis forces

The Axis powers, ; it, Potenze dell'Asse ; ja, 枢軸国 ''Sūjikukoku'', group=nb originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis, was a military coalition that initiated World War II and fought against the Allies. Its principal members were ...

on the Eastern Front. Though Iran was neutral, the Allies considered Reza Shah

Reza Shah Pahlavi ( fa, رضا شاه پهلوی; ; originally Reza Khan (); 15 March 1878 – 26 July 1944) was an Iranian Officer (armed forces), military officer, politician (who served as Ministry of Defence and Armed Forces Logistics (Iran), ...

to be friendly to Nazi Germany, Germany, deposed him during the subsequent occupation and replaced him with his young son Mohammad Reza Pahlavi.

1944-1947: Romania

As World War II turned against the Axis and the Soviet Union won on the Eastern Front, several Romanian politicians, including Mihai Antonescu and Iuliu Maniu, entered secret negotiations with the Allies. At the time Romania was ruled over by dictator Ion Antonescu, with Michael I of Romania, King Michael I as a figurehead. The Romanians had contributed a large number of troops to the front, and had hoped to regain territory and survive. After the Soviets launched a successful offensive into Romania King Michael I met with the National Democratic Bloc to try and take over the government. He tried to get the dictator Ion Antonescu, to switch sides but he refused. So the king immediately ordered his arrest and took over the government in 1944 Romanian coup d'état, King Michael's Coup. Romania switched sides and began fighting against the Axis.

However the Soviet Union still ended up occupying the country. The Soviet representatives pressured the king into appointing Petru Groza, the candidate put forwards by the communist alliance, as the Prime Minister of Romania in March 1945. The following year the communist-dominated alliance won 1946 Romanian general election, though the opposition accused the government of widespread fraud. The king only ruled as a figurehead, and the Romanian Communist Party took control of the country. In the 1947 the Paris Peace Treaties, 1947, Paris Peace Treaties allowed the Red Army to continue to maintain troops in the country. In 1947 the government forced the King to abdicate and leave the country, and afterwards abolished the Kingdom of Romania, Romanian monarchy. The Parliament declared the Communist Romania, Romanian People's Republic in Bucharest, which was friendly and aligned with Moscow. The Soviet occupation of Romania, Soviet Army presence continued until 1958.

As World War II turned against the Axis and the Soviet Union won on the Eastern Front, several Romanian politicians, including Mihai Antonescu and Iuliu Maniu, entered secret negotiations with the Allies. At the time Romania was ruled over by dictator Ion Antonescu, with Michael I of Romania, King Michael I as a figurehead. The Romanians had contributed a large number of troops to the front, and had hoped to regain territory and survive. After the Soviets launched a successful offensive into Romania King Michael I met with the National Democratic Bloc to try and take over the government. He tried to get the dictator Ion Antonescu, to switch sides but he refused. So the king immediately ordered his arrest and took over the government in 1944 Romanian coup d'état, King Michael's Coup. Romania switched sides and began fighting against the Axis.

However the Soviet Union still ended up occupying the country. The Soviet representatives pressured the king into appointing Petru Groza, the candidate put forwards by the communist alliance, as the Prime Minister of Romania in March 1945. The following year the communist-dominated alliance won 1946 Romanian general election, though the opposition accused the government of widespread fraud. The king only ruled as a figurehead, and the Romanian Communist Party took control of the country. In the 1947 the Paris Peace Treaties, 1947, Paris Peace Treaties allowed the Red Army to continue to maintain troops in the country. In 1947 the government forced the King to abdicate and leave the country, and afterwards abolished the Kingdom of Romania, Romanian monarchy. The Parliament declared the Communist Romania, Romanian People's Republic in Bucharest, which was friendly and aligned with Moscow. The Soviet occupation of Romania, Soviet Army presence continued until 1958.

1944–1949: Xinjiang

1944–1946: Bulgaria

The Kingdom of Bulgaria originally joined the Axis to gain territory and be protected from the USSR. Additionally, Bulgaria wanted to fend off the communists in the country, who had influence in the army. Despite this, Bulgaria did not participate in the war very much, not joining in Operation Barbarossa, Operation Barbarosa and Rescue of the Bulgarian Jews, refusing to send its Jewish Population to concentration camps. However, in 1943 Boris III of Bulgaria, Tsar Boris III died, and the Axis were starting to lose on the Eastern Front. The Bulgarian government negotiated with the allies and withdrew from the war in August 1944. Despite this they refused to expel the German troops still stationed in the country. The Soviet Union responded by invading the country in September 1944, which coincided with the 1944 Bulgarian coup d'état, 1944 coup by communists. The coup saw the communist Bulgarian Fatherland Front, Fatherland Front take power. The new government abolished the monarchy and executed former officials of the government including 1,000 to 3,000 dissidents, war criminals, and monarchists in the People's Court (Bulgaria), People's Court, as well as exilling Simeon Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, Tsar Simeon II. Following the 1946 Bulgarian republic referendum the People's Republic of Bulgaria was set up under the leadership of Georgi Dimitrov.

The Kingdom of Bulgaria originally joined the Axis to gain territory and be protected from the USSR. Additionally, Bulgaria wanted to fend off the communists in the country, who had influence in the army. Despite this, Bulgaria did not participate in the war very much, not joining in Operation Barbarossa, Operation Barbarosa and Rescue of the Bulgarian Jews, refusing to send its Jewish Population to concentration camps. However, in 1943 Boris III of Bulgaria, Tsar Boris III died, and the Axis were starting to lose on the Eastern Front. The Bulgarian government negotiated with the allies and withdrew from the war in August 1944. Despite this they refused to expel the German troops still stationed in the country. The Soviet Union responded by invading the country in September 1944, which coincided with the 1944 Bulgarian coup d'état, 1944 coup by communists. The coup saw the communist Bulgarian Fatherland Front, Fatherland Front take power. The new government abolished the monarchy and executed former officials of the government including 1,000 to 3,000 dissidents, war criminals, and monarchists in the People's Court (Bulgaria), People's Court, as well as exilling Simeon Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, Tsar Simeon II. Following the 1946 Bulgarian republic referendum the People's Republic of Bulgaria was set up under the leadership of Georgi Dimitrov.

1944–1946: Poland

On 17 September 1939, the Soviet Union invaded Poland from the east, sixteen days after Nazi Germany, Germany Invasion of Poland, invaded Poland from the west. Subsequent military operations lasted for the following 20 days and ended on 6 October 1939 with the two-way division and annexation of the entire territory of the Second Polish Republic by Germany and the Soviet Union.

On 17 September 1939, the Soviet Union invaded Poland from the east, sixteen days after Nazi Germany, Germany Invasion of Poland, invaded Poland from the west. Subsequent military operations lasted for the following 20 days and ended on 6 October 1939 with the two-way division and annexation of the entire territory of the Second Polish Republic by Germany and the Soviet Union.Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact

, long_name = Treaty of Non-Aggression between Germany and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

, image = Bundesarchiv Bild 183-H27337, Moskau, Stalin und Ribbentrop im Kreml.jpg

, image_width = 200

, caption = Stalin and Ribbentrop shaking ...

on 23 August 1939.

The Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, after ...

, which vastly outnumbered the Polish defenders, achieved its targets encountering only limited resistance. Roughly 320,000 Polish prisoners of war had been captured.Yalta Conference

The Yalta Conference (codenamed Argonaut), also known as the Crimea Conference, held 4–11 February 1945, was the World War II meeting of the heads of government of the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union to discuss the post ...

permitted the Soviet Union to annex almost all of their Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact portion of the Second Polish Republic, compensating the Polish People's Republic with the southern half of East Prussia and territories east of the Oder–Neisse line.[Sylwester Fertacz]

"Krojenie mapy Polski: Bolesna granica" (Carving of Poland's map).

''Alfa''. Retrieved from the Internet Archive on 28 October 2015.

1945–1949: Hungary

As the allies were on their way to victory in World War II, Hungary was governed by the Hungarist Arrow Cross Party under the Government of National Unity (Hungary), Government of National Unity. They were facing mostly advancing Soviet and Romanian forces. On 13 February 1945 the forces captured Budapest, by April 1945 German forces were driven out of the country.[J. Lee Ready (1995), ''World War Two. Nation by Nation'', London, Cassell, page 130. ] They occupied the country and set it up as a Satellite State called the Second Hungarian Republic. In the 1945 Hungarian parliamentary election the Independent Smallholders Party won 57% of the vote while the Hungarian Communist Party won only 17%. In response the Soviet forces refused to allow the party to take power, and the communists took control of the government in a coup. Their rule saw the Stalinization of the country, and with the help of the USSR sent dissidents to Gulags in the Soviet Union, as well as setting up the Security Police known as the State Protection Authority (AVO). In February 1947 the police began targeting member of the Independent Smallholders Party and the National Peasant Party (Hungary), National Peasants Party. As well in 1947 the Hungarian government forced the leaders of non-communist parties to cooperate with the government. The Social Democratic Party of Hungary was taken over while the Secretary of Independent Smallholders Party was sent to Siberia. In June 1948 the Social Democrats were forced to fuse with the communists to form the Hungarian Working People's Party. In the 1949 Hungarian parliamentary elections the voters were only presented with a list of communist candidates and the Hungarian government drafted a new constitution from the 1936 Soviet Constitution, and made themselves into the Hungarian People's Republic, People's Republic of Hungary with Mátyás Rákosi, Matyas Rakosi as the de facto leader.

1945: Germany