Southern Rhodesia in World War II on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

When

When

No. 237 Squadron, based in Kenya since before the start of the war, had expanded to 28 officers and 209 other ranks by March 1940. By mid-1940, most of the officers and men Southern Rhodesia had sent overseas were in Kenya, attached to various East African formations, the

No. 237 Squadron, based in Kenya since before the start of the war, had expanded to 28 officers and 209 other ranks by March 1940. By mid-1940, most of the officers and men Southern Rhodesia had sent overseas were in Kenya, attached to various East African formations, the

Italian forces entered British Somaliland from Abyssinia on 4 August 1940, overcame the garrison at

Italian forces entered British Somaliland from Abyssinia on 4 August 1940, overcame the garrison at

In North Africa, Rhodesians in the

In North Africa, Rhodesians in the  Rhodesians made up an integral component of the

Rhodesians made up an integral component of the

The decisive victory of Lieutenant-General

The decisive victory of Lieutenant-General

The Mareth Line constituted one of two fronts in the

The Mareth Line constituted one of two fronts in the

Southern Rhodesia was represented in the Dodecanese Campaign of September–November 1943 by the Long Range Desert Group, which was withdrawn from the North African front in March 1943. After retraining for mountain operations in Lebanon, the LRDG moved in late September to the

Southern Rhodesia was represented in the Dodecanese Campaign of September–November 1943 by the Long Range Desert Group, which was withdrawn from the North African front in March 1943. After retraining for mountain operations in Lebanon, the LRDG moved in late September to the

The largest concentration of Southern Rhodesian troops in the Italian Campaign of 1943–45 was the group of about 1,400, mainly from the Southern Rhodesian Reconnaissance Regiment, spread across the South African 6th Armoured Division. The 11th South African Armoured Brigade, one of the 6th Division's two main components, was made up of

The largest concentration of Southern Rhodesian troops in the Italian Campaign of 1943–45 was the group of about 1,400, mainly from the Southern Rhodesian Reconnaissance Regiment, spread across the South African 6th Armoured Division. The 11th South African Armoured Brigade, one of the 6th Division's two main components, was made up of  By the end of August 1944 the German forces in Italy had formed the

By the end of August 1944 the German forces in Italy had formed the

The successes of

The successes of

Southern Rhodesia's fighting contributions in Britain and western Europe were primarily in the air, as part of the much larger Allied forces. Rhodesian pilots and Allied airmen trained in the colony's flying schools participated in the defence of Britain throughout the war, as well as in the

Southern Rhodesia's fighting contributions in Britain and western Europe were primarily in the air, as part of the much larger Allied forces. Rhodesian pilots and Allied airmen trained in the colony's flying schools participated in the defence of Britain throughout the war, as well as in the  From early 1944, No. 266 Squadron took part in ground attack operations over the Channel and northern France, operating from

From early 1944, No. 266 Squadron took part in ground attack operations over the Channel and northern France, operating from

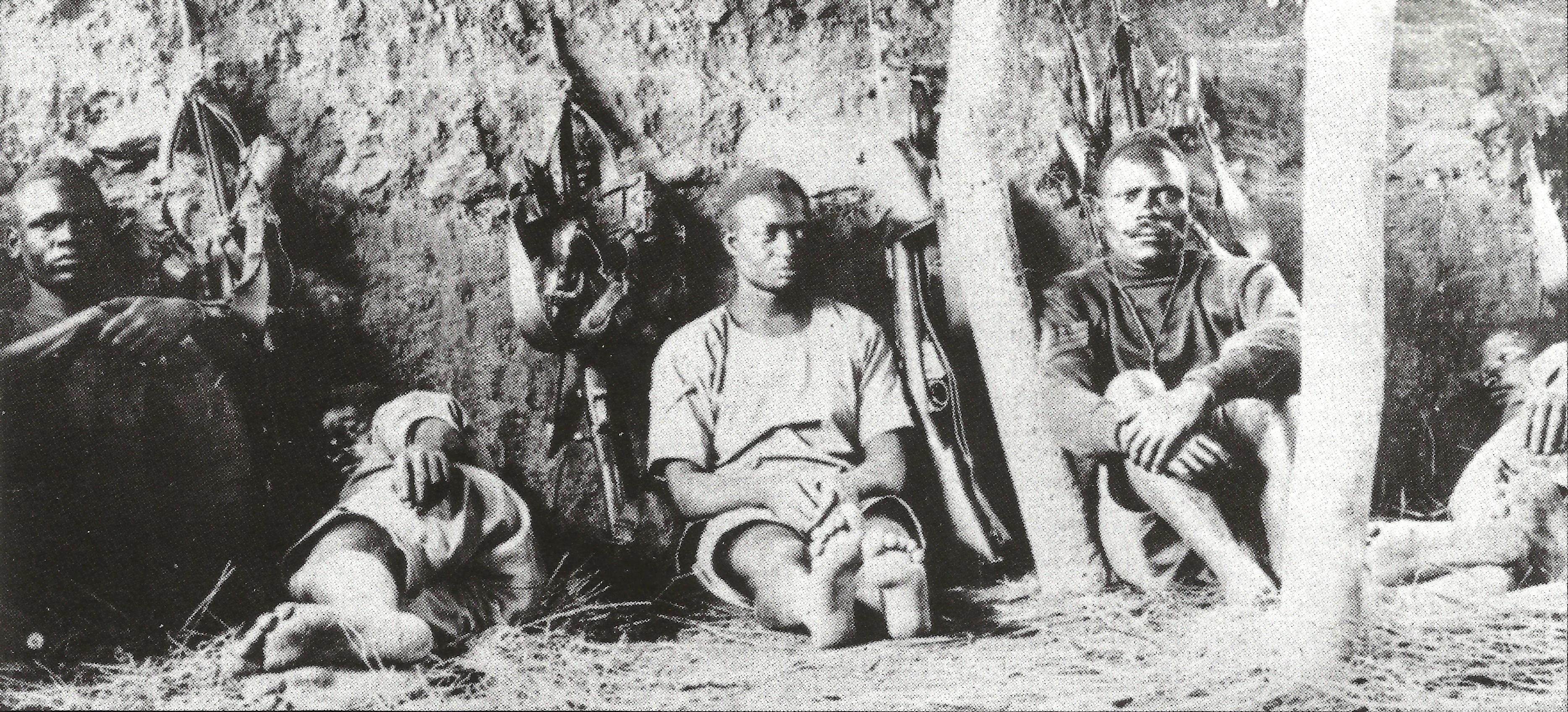

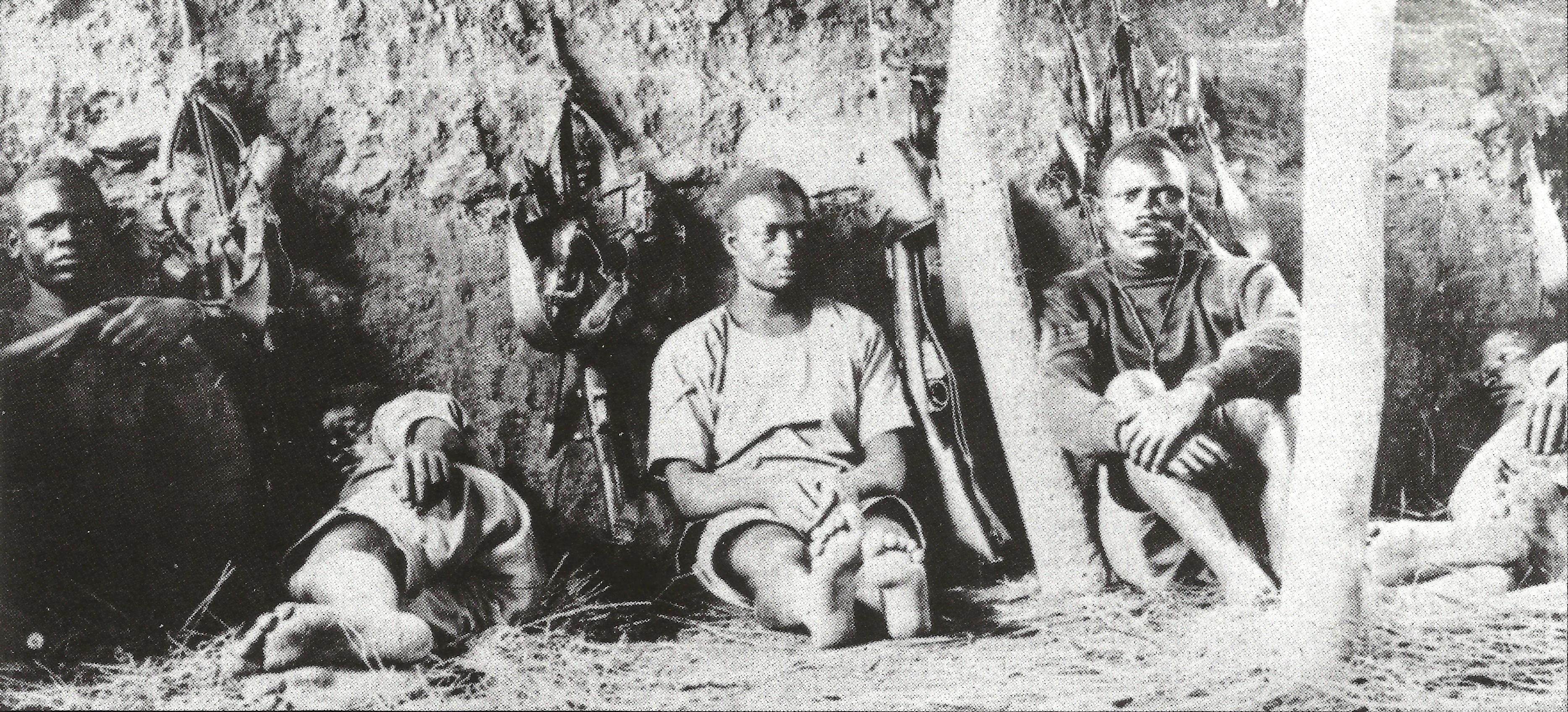

Southern Rhodesia's main contribution to the Burma Campaign in terms of manpower was made by the

Southern Rhodesia's main contribution to the Burma Campaign in terms of manpower was made by the  1RAR trained in Kenya from December 1943 to September 1944, when it transferred to

1RAR trained in Kenya from December 1943 to September 1944, when it transferred to

The Rhodesian African Rifles were based at Borrowdale, Harare, Borrowdale in north-east Salisbury between 1940 and 1943. Apart from a contingent sent south to Durban to guard Italian prisoners on their way to Rhodesia, the regiment's main role was garrison duties within the colony. The Rhodesian Air Askari Corps, a unit of black volunteer troops under white command, guarded the air bases and also provided manpower for non-armed labour. The perceived possibility that Japan might attempt an invasion of southern Africa via Madagascar led to the consolidation of a few hundred rural whites into the Southern Rhodesia Commando, a part-time cadre intended as the basis for a guerrilla-style resistance movement, from 1942.

The mobilisation of white British South Africa Police officers for military service led to black male and white female constables taking on higher responsibilities. The BSAP recruited more black patrolmen to accommodate the growth of the urban black population during the war, going from 1,067 black and 547 white personnel in 1937 to 1,572 blacks and 401 whites in 1945. This " Africanisation" led to higher appreciation for black constables among senior policemen and the public. The police remained rigidly segregated, but black constables received uniforms more similar to those of their white counterparts, and the nominal distinction between the BSAP "proper" and the British South Africa Native Police—the "force within the force" black personnel were traditionally regarded as members of—was abolished.

The Rhodesian African Rifles were based at Borrowdale, Harare, Borrowdale in north-east Salisbury between 1940 and 1943. Apart from a contingent sent south to Durban to guard Italian prisoners on their way to Rhodesia, the regiment's main role was garrison duties within the colony. The Rhodesian Air Askari Corps, a unit of black volunteer troops under white command, guarded the air bases and also provided manpower for non-armed labour. The perceived possibility that Japan might attempt an invasion of southern Africa via Madagascar led to the consolidation of a few hundred rural whites into the Southern Rhodesia Commando, a part-time cadre intended as the basis for a guerrilla-style resistance movement, from 1942.

The mobilisation of white British South Africa Police officers for military service led to black male and white female constables taking on higher responsibilities. The BSAP recruited more black patrolmen to accommodate the growth of the urban black population during the war, going from 1,067 black and 547 white personnel in 1937 to 1,572 blacks and 401 whites in 1945. This " Africanisation" led to higher appreciation for black constables among senior policemen and the public. The police remained rigidly segregated, but black constables received uniforms more similar to those of their white counterparts, and the nominal distinction between the BSAP "proper" and the British South Africa Native Police—the "force within the force" black personnel were traditionally regarded as members of—was abolished.

The WAV, run by the Ministry of Defence, recruited and trained female personnel for the WAAS and the WAMS, which respectively came under the Air and Defence Ministries. According to the official statement announcing their formation, the services' purpose was "to substitute women for men wherever necessary and practicable throughout the military and air forces within Southern Rhodesia."

Recruitment for the women's services began in June 1941. Most volunteers were married women, many of them the wives of military men. The air and military services both offered a wide variety of positions. In addition to jobs as typists, clerks, caterers and the like, women served as drivers and in the stores and workshops. Many of the women in the air service did skilled work, checking flying instruments, testing parts and doing minor repairs. The women of the Auxiliary Police Service served as BSAP officers both in stations and on the streets.

Members of Southern Rhodesia's white female population who did not join the forces still contributed to the war in various ways. Women worked in munitions factories and engineering workshops in Salisbury and

The WAV, run by the Ministry of Defence, recruited and trained female personnel for the WAAS and the WAMS, which respectively came under the Air and Defence Ministries. According to the official statement announcing their formation, the services' purpose was "to substitute women for men wherever necessary and practicable throughout the military and air forces within Southern Rhodesia."

Recruitment for the women's services began in June 1941. Most volunteers were married women, many of them the wives of military men. The air and military services both offered a wide variety of positions. In addition to jobs as typists, clerks, caterers and the like, women served as drivers and in the stores and workshops. Many of the women in the air service did skilled work, checking flying instruments, testing parts and doing minor repairs. The women of the Auxiliary Police Service served as BSAP officers both in stations and on the streets.

Members of Southern Rhodesia's white female population who did not join the forces still contributed to the war in various ways. Women worked in munitions factories and engineering workshops in Salisbury and

Along with most of the Commonwealth and Allied nations, Southern Rhodesia sent a delegation of soldiers, airmen and seamen to London to take part in the grand

Along with most of the Commonwealth and Allied nations, Southern Rhodesia sent a delegation of soldiers, airmen and seamen to London to take part in the grand

Amid

Amid

Southern Rhodesia

Southern Rhodesia was a landlocked self-governing British Crown colony in southern Africa, established in 1923 and consisting of British South Africa Company (BSAC) territories lying south of the Zambezi River. The region was informally kn ...

, then a self-governing colony

In the British Empire, a self-governing colony was a colony with an elected government in which elected rulers were able to make most decisions without referring to the colonial power with nominal control of the colony. This was in contrast to a ...

of the United Kingdom, entered World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

along with Britain shortly after the invasion of Poland

The invasion of Poland (1 September – 6 October 1939) was a joint attack on the Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union which marked the beginning of World War II. The German invasion began on 1 September 1939, one week aft ...

in 1939. By the war's end, 26,121 Southern Rhodesians of all races had served in the armed forces, 8,390 of them overseas, operating in the European theatre

The European theatre of World War II was one of the two main theatres of combat during World War II. It saw heavy fighting across Europe for almost six years, starting with Germany's invasion of Poland on 1 September 1939 and ending with the ...

, the Mediterranean and Middle East theatre

The Mediterranean and Middle East Theatre was a major theatre of operations during the Second World War. The vast size of the Mediterranean and Middle East theatre saw interconnected naval, land, and air campaigns fought for control of the Medit ...

, East Africa

East Africa, Eastern Africa, or East of Africa, is the eastern subregion of the African continent. In the United Nations Statistics Division scheme of geographic regions, 10-11-(16*) territories make up Eastern Africa:

Due to the historical ...

, Burma

Myanmar, ; UK pronunciations: US pronunciations incl. . Note: Wikipedia's IPA conventions require indicating /r/ even in British English although only some British English speakers pronounce r at the end of syllables. As John Wells explai ...

and elsewhere. The territory's most important contribution to the war is commonly held to be its contribution to the Empire Air Training Scheme

The British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP), or Empire Air Training Scheme (EATS) often referred to as simply "The Plan", was a massive, joint military aircrew training program created by the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia and New Zea ...

(EATS), under which 8,235 British, Commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. Historically, it has been synonymous with "republic". The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the ...

and Allied

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

airmen were trained in Southern Rhodesian flying schools. The colony's operational casualties numbered 916 killed and 483 wounded of all races.

Southern Rhodesia had no diplomatic powers, but largely oversaw its own contributions of manpower and materiel to the war effort, being responsible for its own defence. Rhodesian officers and soldiers were distributed in small groups throughout the British and South African forces in an attempt to prevent high losses. Most of the colony's men served in Britain, East Africa and the Mediterranean, particularly at first; a more broad dispersal occurred from late 1942. Rhodesian servicemen in operational areas were mostly from the country's white

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully reflect and scatter all the visible wavelengths of light. White on ...

minority, with the Rhodesian African Rifles

The Rhodesian African Rifles (RAR) was a regiment of the Rhodesian Army. The ranks of the RAR were recruited from the black African population, although officers were generally from the white population. The regiment was formed in May 1940 in the ...

—made up of black troops and white officers—providing the main exception in Burma from late 1944. Other non-white soldiers and white servicewomen served in East Africa and on the home front within Southern Rhodesia. Tens of thousands of black men were conscripted

Conscription (also called the draft in the United States) is the state-mandated enlistment of people in a national service, mainly a military service. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it continues in some countries to the present day un ...

from rural communities for work, first on the aerodromes and later on white-owned farms.

World War II prompted major changes in Southern Rhodesia's financial and military policy, and accelerated the process of industrialisation. The territory's participation in the EATS brought about major economic and infrastructural developments and led to the post-war immigration of many former airmen, contributing to the growth of the white population to over double its pre-war size by 1951. The war remained prominent in the national consciousness for decades afterwards. Since the country's reconstitution as Zimbabwe in 1980, the modern government has removed many references to the World Wars, such as memorial monuments and plaques, from public view, regarding them as unwelcome vestiges of white minority rule and colonialism.

Background

When

When World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

broke out in 1939, the southern African territory of Southern Rhodesia

Southern Rhodesia was a landlocked self-governing British Crown colony in southern Africa, established in 1923 and consisting of British South Africa Company (BSAC) territories lying south of the Zambezi River. The region was informally kn ...

had been a self-governing colony

In the British Empire, a self-governing colony was a colony with an elected government in which elected rulers were able to make most decisions without referring to the colonial power with nominal control of the colony. This was in contrast to a ...

of the United Kingdom for 16 years, having gained responsible government

Responsible government is a conception of a system of government that embodies the principle of parliamentary accountability, the foundation of the Westminster system of parliamentary democracy. Governments (the equivalent of the executive bran ...

in 1923. It was unique in the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts esta ...

and Commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. Historically, it has been synonymous with "republic". The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the ...

in that it held extensive autonomous powers (including defence, but not foreign affairs) while lacking dominion

The term ''Dominion'' is used to refer to one of several self-governing nations of the British Empire.

"Dominion status" was first accorded to Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Newfoundland, South Africa, and the Irish Free State at the 1926 ...

status. In practice, it acted as a quasi-dominion, and was treated as such in many ways by the rest of the Commonwealth. Southern Rhodesia's white

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully reflect and scatter all the visible wavelengths of light. White on ...

population in 1939 was 67,000, a minority of about 5%; the black

Black is a color which results from the absence or complete absorption of visible light. It is an achromatic color, without hue, like white and grey. It is often used symbolically or figuratively to represent darkness. Black and white have o ...

population was a little over a million, and there were about 10,000 residents of coloured

Coloureds ( af, Kleurlinge or , ) refers to members of multiracial ethnic communities in Southern Africa who may have ancestry from more than one of the various populations inhabiting the region, including African, European, and Asian. South ...

(mixed) or Indian

Indian or Indians may refer to:

Peoples South Asia

* Indian people, people of Indian nationality, or people who have an Indian ancestor

** Non-resident Indian, a citizen of India who has temporarily emigrated to another country

* South Asia ...

ethnicity. The franchise was non-racial and in theory open to all, contingent on meeting financial and educational qualifications, but in practice very few black citizens were on the electoral roll. The colony's Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is not ...

was Godfrey Huggins

Godfrey Martin Huggins, 1st Viscount Malvern (6 July 1883 – 8 May 1971), was a Rhodesian politician and physician. He served as the fourth Prime Minister of Southern Rhodesia from 1933 to 1953 and remained in office as the first Prime Minis ...

, a physician and veteran of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

(1914–18) who had emigrated to Rhodesia from England in 1911 and held office since 1933.

The territory's contribution to the British cause during World War I had been very large in proportion to its white population, though troops had been mostly raised from scratch as there had been no professional standing army beforehand. Since the start of self-government in 1923, the colony had organised the all-white Rhodesia Regiment

The Rhodesia Regiment (RR) was one of the oldest and largest regiments in the Rhodesian Army. It served on the side of the United Kingdom in the Second Boer War and the First and Second World Wars and served the Republic of Rhodesia in the Rhode ...

into a permanent defence force, complemented locally by the partly paramilitary British South Africa Police

The British South Africa Police (BSAP) was, for most of its existence, the police force of Rhodesia (renamed Zimbabwe in 1980). It was formed as a paramilitary force of mounted infantrymen in 1889 by Cecil Rhodes' British South Africa Company, from ...

(BSAP). The Rhodesia Regiment comprised about 3,000 men, including reserves, in 1938. The country had fielded black troops during World War I, but since then had retained them only within the BSAP. A nucleus of airmen existed in the form of the Southern Rhodesian Air Force

The Rhodesian Air Force (RhAF) was an air force based in Salisbury (now Harare) which represented several entities under various names between 1935 and 1980: originally serving the British self-governing colony of Southern Rhodesia, it was the ...

(SRAF), which in August 1939 comprised one squadron of 10 pilots and eight Hawker Hardy

The Hawker Hart is a British two-seater biplane light bomber aircraft that saw service with the Royal Air Force (RAF). It was designed during the 1920s by Sydney Camm and manufactured by Hawker Aircraft. The Hart was a prominent British aircra ...

aircraft, based at Belvedere Airport near Salisbury

Salisbury ( ) is a cathedral city in Wiltshire, England with a population of 41,820, at the confluence of the rivers Avon, Nadder and Bourne. The city is approximately from Southampton and from Bath.

Salisbury is in the southeast of Wil ...

.

The occupation of Czechoslovakia

Occupation commonly refers to:

*Occupation (human activity), or job, one's role in society, often a regular activity performed for payment

*Occupation (protest), political demonstration by holding public or symbolic spaces

*Military occupation, th ...

by Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

in March 1939 convinced Huggins that war was imminent. Seeking to renew his government's mandate to pass emergency measures, he called an early election

An election is a formal group decision-making process by which a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative democracy has opera ...

in which his United Party won an increased majority. Huggins rearranged his Cabinet on a war footing, making the Minister of Justice Robert Tredgold

The Rt Hon. Sir Robert Clarkson Tredgold, KCMG, PC (2 June 1899 – 8 April 1977), was a Rhodesian barrister, judge and politician.

Early life

He was born in Bulawayo to Clarkson Henry Tredgold, the Attorney-General of Southern Rhodesia, ...

Minister of Defence as well. The territory proposed forces not only for internal security but also for the defence of British interests overseas. Self-contained Rhodesian formations were planned, including a mechanised reconnaissance unit, but Tredgold opposed this. Remembering the catastrophic casualties suffered by units such as the Royal Newfoundland Regiment

The Royal Newfoundland Regiment (R NFLD R) is a Primary Reserve infantry regiment of the Canadian Army. It is part of the 5th Canadian Division's 37 Canadian Brigade Group.

Predecessor units trace their origins to 1795, and since 1949 Royal N ...

and the 1st South African Infantry Brigade on the Western Front in World War I, he argued that one or two heavy defeats for a white Southern Rhodesian brigade might cause crippling losses and have irrevocable effects on the country as a whole. He proposed to instead concentrate on training white Rhodesians for leadership roles and specialist units, and to disperse the colony's men across the forces in small groups. These ideas met with approval in both Salisbury and London and were adopted.

Southern Rhodesia would be automatically included in any British declaration of war due to its lack of diplomatic powers, but that did not stop the colonial government from attempting to demonstrate its loyalty and legislative independence through supportive parliamentary motions and gestures. The Southern Rhodesian parliament unanimously moved to support Britain in the event of war during a special sitting on 28 August 1939.

Outbreak of war

When Britain declared war on Germany on 3 September 1939 following theinvasion of Poland

The invasion of Poland (1 September – 6 October 1939) was a joint attack on the Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union which marked the beginning of World War II. The German invasion began on 1 September 1939, one week aft ...

, Southern Rhodesia issued its own declaration of war almost immediately, before any of the dominions did. Huggins backed full military mobilisation and "a war to the finish", telling parliament that the conflict was one of national survival for Southern Rhodesia as well as for Britain; the mother country's defeat would leave little hope for the colony in the post-war world, he said. This stand was almost unanimously supported by the white populace, as well as most of the coloured community, though with World War I a recent memory this was more out of a sense of patriotic duty than enthusiasm for war in itself. The majority of the black population paid little attention to the outbreak of war.

The British had expected Fascist Italy—with its African possessions—to join the war on Germany's side as soon as it began, but fortunately for the Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

this did not immediately occur. No. 1 Squadron SRAF was already in northern Kenya

)

, national_anthem = "Ee Mungu Nguvu Yetu"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Nairobi

, coordinates =

, largest_city = Nairobi

, ...

, having been posted to the Italian East Africa

Italian East Africa ( it, Africa Orientale Italiana, AOI) was an Italian colony in the Horn of Africa. It was formed in 1936 through the merger of Italian Somalia, Italian Eritrea, and the newly occupied Ethiopian Empire, conquered in the Seco ...

n frontier at Britain's request in late August. The first Southern Rhodesian ground forces to be deployed abroad during World War II were 50 Territorial troops under Captain T G Standing, who were posted to Nyasaland

Nyasaland () was a British protectorate located in Africa that was established in 1907 when the former British Central Africa Protectorate changed its name. Between 1953 and 1963, Nyasaland was part of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasala ...

in September at the request of the colonial authorities there to guard against a possible uprising by German expatriates. They returned home after a month, having seen little action. White Rhodesian officers and non-commissioned officer

A non-commissioned officer (NCO) is a military officer who has not pursued a commission. Non-commissioned officers usually earn their position of authority by promotion through the enlisted ranks. (Non-officers, which includes most or all enli ...

s left the colony in September and October 1939 to command units of black Africans in the west and east of the continent, with most joining the Royal West African Frontier Force

The West African Frontier Force (WAFF) was a multi-battalion field force, formed by the British Colonial Office in 1900 to garrison the West African colonies of Nigeria, Gold Coast, Sierra Leone and Gambia. In 1928, it received royal recognition ...

(RWAFF) in the Colony of Nigeria

Colonial Nigeria was ruled by the British Empire from the mid-nineteenth century until 1960 when Nigeria achieved independence. British influence in the region began with the prohibition of slave trade to British subjects in 1807. Britain a ...

, the Gold Coast

Gold Coast may refer to:

Places Africa

* Gold Coast (region), in West Africa, which was made up of the following colonies, before being established as the independent nation of Ghana:

** Portuguese Gold Coast (Portuguese, 1482–1642)

** Dutch G ...

and neighbouring colonies. The deployment of white Rhodesian officers and NCOs to command black troops from elsewhere in Africa met with favour from the military leadership and became very prevalent.

As in World War I, white Rhodesians volunteered for the forces readily and in large numbers. Over 2,700 had come forward before the war was three weeks old. Somewhat ironically, the Southern Rhodesian recruiters' main problem was not sourcing manpower but rather persuading men in strategically important occupations such as mining to stay home. Manpower controls were introduced to keep certain men in their civilian jobs. The SRAF accepted 500 recruits in the days following the outbreak of war, prompting its commander Group Captain Charles Meredith to contact the Air Ministry

The Air Ministry was a department of the Government of the United Kingdom with the responsibility of managing the affairs of the Royal Air Force, that existed from 1918 to 1964. It was under the political authority of the Secretary of State ...

in London with an offer to run a flying school and train three squadrons. This was accepted. In January 1940 the Southern Rhodesian government announced the establishment of an independent Air Ministry to oversee the Rhodesian Air Training Group

This article contains a list of the Southern Rhodesian facilities forming part of Joint Air Training Scheme which was a major programme for training South African Air Force, Royal Air Force and Allied air crews during World War II. However, R ...

, Southern Rhodesia's contribution to the Empire Air Training Scheme

The British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP), or Empire Air Training Scheme (EATS) often referred to as simply "The Plan", was a massive, joint military aircrew training program created by the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia and New Zea ...

(EATS).

Huggins set up a Defence Committee within the Cabinet to co-ordinate the colony's war effort in early 1940. This body comprised the Prime Minister, Tredgold and Lieutenant-Colonel Ernest Lucas Guest

Sir Ernest Lucas Guest (20 August 1882 – 20 September 1972) was a Rhodesian politician, lawyer and soldier. He held senior ministerial positions in the government, most notably as Minister for Air during the Second World War.

Guest w ...

, the Minister of Mines and Public Works, who was put in charge of the new Air Ministry. About 1,600 of the colony's whites were serving overseas by May 1940 when, during the Battle of France

The Battle of France (french: bataille de France) (10 May – 25 June 1940), also known as the Western Campaign ('), the French Campaign (german: Frankreichfeldzug, ) and the Fall of France, was the Nazi Germany, German invasion of French Third Rep ...

, Salisbury passed legislation allowing the authorities to call up any male British subject

The term "British subject" has several different meanings depending on the time period. Before 1949, it referred to almost all subjects of the British Empire (including the United Kingdom, Dominions, and colonies, but excluding protectorates ...

of European ancestry aged between 19 and a half and 25 who had lived in the colony for at least six months. The minimum age was reduced to 18 in 1942. Part-time training was compulsory for all white males between 18 and 55, with a small number of exceptions for those in reserved occupations. On 25 May 1940 Southern Rhodesia, the last country to join the EATS, became the first to start operating an air school under it, beating Canada by a week. The SRAF was absorbed into the British Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) and ...

in April 1940, with No. 1 Squadron becoming No. 237 Squadron. The RAF subsequently designated two more Rhodesian squadrons, namely No. 266 Squadron in 1940 and No. 44 Squadron in 1941, in a manner similar to the Article XV squadrons

Article XV squadrons were Australian, Canadian, and New Zealand air force squadrons formed from graduates of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (1939) during World War II.

These units complemented another feature of the BCATP, under whi ...

from Australia, Canada and New Zealand.

Africa and the Mediterranean

Early deployments

No. 237 Squadron, based in Kenya since before the start of the war, had expanded to 28 officers and 209 other ranks by March 1940. By mid-1940, most of the officers and men Southern Rhodesia had sent overseas were in Kenya, attached to various East African formations, the

No. 237 Squadron, based in Kenya since before the start of the war, had expanded to 28 officers and 209 other ranks by March 1940. By mid-1940, most of the officers and men Southern Rhodesia had sent overseas were in Kenya, attached to various East African formations, the King's African Rifles

The King's African Rifles (KAR) was a multi-battalion British colonial regiment raised from Britain's various possessions in East Africa from 1902 until independence in the 1960s. It performed both military and internal security functions withi ...

(KAR), the RWAFF, or to the colony's own Medical Corps or Survey Unit. The Southern Rhodesian surveyors charted the previously unmapped area bordering Abyssinia and Italian Somaliland between March and June 1940, and the Medical Corps operated No. 2 General Hospital in Nairobi

Nairobi ( ) is the capital and largest city of Kenya. The name is derived from the Maasai phrase ''Enkare Nairobi'', which translates to "place of cool waters", a reference to the Nairobi River which flows through the city. The city proper ha ...

from July. A company of coloured and Indian-Rhodesian transport drivers was also in the country, having arrived in January.

The first Southern Rhodesian contingent despatched to North Africa and the Middle East was a draft of 700 from the Rhodesia Regiment who left in April 1940. No white Rhodesian force of this size had ever left the territory before. They were posted to a variety of British units across Egypt and Palestine. The largest concentration of Rhodesian soldiers in North Africa belonged to the King's Royal Rifle Corps

The King's Royal Rifle Corps was an infantry rifle regiment of the British Army that was originally raised in British North America as the Royal American Regiment during the phase of the Seven Years' War in North America known in the United St ...

(KRRC), whose connections with the colony dated back to World War I. Several Rhodesian platoons were formed in the KRRC's 1st Battalion in the Western Desert. A company of men from the Southern Rhodesian Signal Corps was also present, operating in tandem with the British Royal Corps of Signals

The Royal Corps of Signals (often simply known as the Royal Signals – abbreviated to R SIGNALS or R SIGS) is one of the combat support arms of the British Army. Signals units are among the first into action, providing the battlefield communi ...

.

East Africa

Italy joined the war on Germany's side on 10 June 1940, opening the East African Campaign and the Desert War in North Africa. A Rhodesian-led force of irregulars from theSomaliland Camel Corps

The Somaliland Camel Corps (SCC) was a Rayid unit of the British Army based in British Somaliland. It lasted from the early 20th century until 1944.

Beginnings and the Dervish rebellion

In 1888, after signing successive treaties with the then r ...

—based in British Somaliland

British Somaliland, officially the Somaliland Protectorate ( so, Dhulka Maxmiyada Soomaalida ee Biritishka), was a British Empire, British protectorate in present-day Somaliland. During its existence, the territory was bordered by Italian Soma ...

, on the Horn of Africa

The Horn of Africa (HoA), also known as the Somali Peninsula, is a large peninsula and geopolitical region in East Africa.Robert Stock, ''Africa South of the Sahara, Second Edition: A Geographical Interpretation'', (The Guilford Press; 2004), ...

's north coast—took part in one of the first clashes between British and Italian forces when it exchanged fire with an Italian '' banda'' (irregular company) around dawn on 11 June. Two days later three Caproni

Caproni, also known as ''Società de Agostini e Caproni'' and ''Società Caproni e Comitti'', was an Italian aircraft manufacturer. Its main base of operations was at Taliedo, near Linate Airport, on the outskirts of Milan.

Founded by Giovan ...

bombers of the ''Regia Aeronautica

The Italian Royal Air Force (''Regia Aeronautica Italiana'') was the name of the air force of the Kingdom of Italy. It was established as a service independent of the Royal Italian Army from 1923 until 1946. In 1946, the monarchy was abolis ...

'' attacked Wajir

Wajir ( so, Wajeer) is the capital of the Wajir County of Kenya. It is situated in the former North Eastern Province.

History

A cluster of cairns near Wajir are generally ascribed by the local inhabitants to the Maadiinle, a semi-legendary pe ...

, one of No. 237 Squadron's forward airstrips, damaging two Rhodesian aircraft.

Hargeisa

Hargeisa (; so, Hargeysa, ar, هرجيسا) is the capital and largest city of the Republic of Somaliland. It is located in the Maroodi Jeex region of the Horn of Africa. It succeeded Burco as the capital of the British Somaliland Protector ...

, and advanced north-east towards the capital Berbera

Berbera (; so, Barbara, ar, بربرة) is the capital of the Sahil region of Somaliland and is the main sea port of the country. Berbera is a coastal city and was the former capital of the British Somaliland protectorate before Hargeisa. It ...

. The British force, including a platoon of 43 Rhodesians in the 2nd Battalion of the Black Watch

The Black Watch, 3rd Battalion, Royal Regiment of Scotland (3 SCOTS) is an infantry battalion of the Royal Regiment of Scotland. The regiment was created as part of the Childers Reforms in 1881, when the 42nd (Royal Highland) Regiment ...

, took up positions on six hills overlooking the only road towards Berbera and engaged the Italians at the Battle of Tug Argan

The Battle of Tug Argan was fought between forces of the British Empire and Italy from 11 to 15 August 1940 in British Somaliland (later the independent and renamed Somalia). The battle determined the result of the Italian conquest of British ...

. Amid heavy fighting, the Italians gradually made gains and by 14 August had almost pocketed the Commonwealth forces. The British retreated to Berbera between 15 and 17 August, the Rhodesians making up the left flank of the rearguard

A rearguard is a part of a military force that protects it from attack from the rear, either during an advance or withdrawal. The term can also be used to describe forces protecting lines, such as communication lines, behind an army. Even more ...

, and by 18 August had evacuated by sea. The Italians took the city and completed their conquest of British Somaliland a day later.

No. 237 Squadron embarked on reconnaissance flights and supported ground assaults on Italian desert outposts during July and August 1940. Two British brigades from West Africa arrived to reinforce Kenya's northern frontier in early July—the partly Rhodesian-officered Nigeria Regiment

The Nigeria Regiment, Royal West African Frontier Force, was formed by the amalgamation of the Northern Nigeria Regiment and the Southern Nigeria Regiment on 1 January 1914. At that time, the regiment consisted of five battalions:

*1st Batta ...

joined the front at Malindi

Malindi is a town on Malindi Bay at the mouth of the Sabaki River, lying on the Indian Ocean coast of Kenya. It is 120 kilometres northeast of Mombasa. The population of Malindi was 119,859 as of the 2019 census. It is the largest urban centre ...

and Garissa

Garissa ( so, Gaarrisa) is the capital of Garissa County, Kenya. It is situated in the former North Eastern Province.

Geography

The Tana River, which rises in Mount Kenya east of Nyeri, flows through the Garissa. The Bour-Algi Giraffe Sanctuar ...

, while a battalion of the Gold Coast Regiment

The Ghana Regiment is an infantry regiment that forms the main fighting element of the Ghanaian Army (GA).

History

The regiment was formed in 1879 as the Gold Coast Constabulary, from personnel of the Hausa Constabulary of Southern Nigeria, to per ...

, also with Rhodesian commanders attached, relieved the KAR at Wajir. The British forces in East Africa adopted the doctrine of "mobile defence" that was already being used in the Western Desert in North Africa—units embarked on long, constant patrols to guard wells and deny water supplies to the Italians. The British evacuated their north forward position at Buna in September 1940, and expected an attack on Wajir soon after, but the Italians never attempted an assault. Boosted considerably by the arrival of three South African brigades during the last months of 1940, the Commonwealth forces in Kenya had expanded to three divisions by the end of the year. No. 237 Squadron was relieved by South African airmen and redeployed to the Sudan

Sudan ( or ; ar, السودان, as-Sūdān, officially the Republic of the Sudan ( ar, جمهورية السودان, link=no, Jumhūriyyat as-Sūdān), is a country in Northeast Africa. It shares borders with the Central African Republic t ...

in September.

Rebasing at Khartoum

Khartoum or Khartum ( ; ar, الخرطوم, Al-Khurṭūm, din, Kaartuɔ̈m) is the capital of Sudan. With a population of 5,274,321, its metropolitan area is the largest in Sudan. It is located at the confluence of the White Nile, flowing n ...

, No. 237 Squadron undertook regular reconnaissance, dive-bombing and strafing

Strafing is the military practice of attacking ground targets from low-flying aircraft using aircraft-mounted automatic weapons.

Less commonly, the term is used by extension to describe high-speed firing runs by any land or naval craft such ...

sorties during October and November 1940. Meanwhile, the Southern Rhodesian Anti-Tank Battery arrived in Kenya in October and, following a period of training, received 2-pounder guns and joined the front at Garissa around the turn of the new year. No. 237 Squadron was partially re-equipped during January 1941, receiving some Westland Lysander

The Westland Lysander is a British army co-operation and liaison aircraft produced by Westland Aircraft that was used immediately before and during the Second World War.

After becoming obsolete in the army co-operation role, the aircraft's ...

Mk IIs, but most of the squadron continued operating Hardys.

The British forces in Kenya under General Alan Cunningham

General (United Kingdom), General Sir Alan Gordon Cunningham, (1 May 1887 – 30 January 1983) was a senior Officer (armed forces), officer of the British Army noted for his victories over Italian forces in the East African Campaign (World War ...

, including Rhodesian officers and NCOs in the King's African Rifles and the Nigeria and Gold Coast Regiments, as well as the South African 1st South African Infantry Division, advanced into Abyssinia and Italian Somaliland

Italian Somalia ( it, Somalia Italiana; ar, الصومال الإيطالي, Al-Sumal Al-Italiy; so, Dhulka Talyaaniga ee Soomaalida), was a protectorate and later colony of the Kingdom of Italy in present-day Somalia. Ruled in the 19th centur ...

during late January and February 1941, starting with the occupation of the ports of Kismayo

Kismayo ( so, Kismaayo, Maay Maay, Maay: ''Kismanyy'', ar, كيسمايو, ; it, Chisimaio) is a port city in the southern Lower Juba (Jubbada Hoose) province of Somalia. It is the commercial capital of the autonomous Jubaland region.

The cit ...

and Mogadishu

Mogadishu (, also ; so, Muqdisho or ; ar, مقديشو ; it, Mogadiscio ), locally known as Xamar or Hamar, is the capital and List of cities in Somalia by population, most populous city of Somalia. The city has served as an important port ...

. The Italians retreated to the interior. No. 237 Squadron meanwhile provided air support to the 4th Indian Infantry Division and 5th Indian Infantry Division during Lieutenant-General William Platt

General Sir William Platt (14 June 1885 – 28 September 1975) was a senior officer of the British Army during both World War I and World War II.

Early years

Platt was educated at Marlborough College and the Royal Military College, Sandhurst.

...

's offensive into Eritrea

Eritrea ( ; ti, ኤርትራ, Ertra, ; ar, إرتريا, ʾIritriyā), officially the State of Eritrea, is a country in the Horn of Africa region of Eastern Africa, with its capital and largest city at Asmara. It is bordered by Ethiopia ...

from the Sudan, attacking ground targets and engaging Italian fighters. One of the Rhodesian Hardys was shot down near Keren on 7 February with the loss of both occupants. Two days later, five Italian fighters attacked a group of grounded Rhodesian aircraft at Agordat

Agordat; also Akordat or Ak'ordat) is a city in Gash-Barka, Eritrea. It was the capital of the former Barka province, which was situated between the present-day Gash-Barka and Anseba regions.

History

Excavations in Agordat uncovered pottery re ...

in western Eritrea, and wrecked two Hardys and two Lysanders.

Platt's advance into Eritrea was checked during the seven-week Battle of Keren

The Battle of Keren ( it, Battaglia di Cheren) took place from 3 February to 27 March 1941. Keren was attacked by the British during the East African Campaign of the Second World War. A force of Italian regular and colonial troops defended th ...

(February–April 1941), during which No. 237 Squadron observed Italian positions and took part in bombing raids. After the Italians retreated and surrendered, the Rhodesian squadron moved forward to Asmara

Asmara ( ), or Asmera, is the capital and most populous city of Eritrea, in the country's Central Region. It sits at an elevation of , making it the sixth highest capital in the world by altitude and the second highest capital in Africa. The ...

on 6 April, whence it embarked on bombing sorties on the port of Massawa

Massawa ( ; ti, ምጽዋዕ, məṣṣəwaʿ; gez, ምጽዋ; ar, مصوع; it, Massaua; pt, Maçuá) is a port city in the Northern Red Sea region of Eritrea, located on the Red Sea at the northern end of the Gulf of Zula beside the Dahlak ...

. The same day, the Italian garrison in the Abyssinian capital Addis Ababa

Addis Ababa (; am, አዲስ አበባ, , new flower ; also known as , lit. "natural spring" in Oromo), is the capital and largest city of Ethiopia. It is also served as major administrative center of the Oromia Region. In the 2007 census, t ...

surrendered to the 11th (East Africa) Division, including many Rhodesians. During the Battle of Amba Alagi, Platt and Cunningham's forces converged and surrounded the remainder of the Italians, who were commanded by the Duke of Aosta

Duke of Aosta ( it, Duca d'Aosta; french: Duc d'Aoste) was a title in the Italian nobility. It was established in the 13th century when Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor, made the County of Aosta a duchy. The region was part of the Savoyard stat ...

at the mountainous stronghold of Amba Alagi

Imba Alaje is a mountain, or an amba, in northern Ethiopia. Located in the Debubawi Zone of the Tigray Region, Imba Alaje dominates the roadway that runs past it from the city of Mek'ele south to Maychew. Because of its strategic location, Emba ...

. The viceroy surrendered on 18 May 1941, effectively ending the war in East Africa. No. 237 Squadron and the Rhodesian Anti-Tank Battery thereupon moved up to Egypt to join the war in the Western Desert. Some Italian garrisons continued to fight—the last surrendered only following the Battle of Gondar

The Battle of Gondar or Capture of Gondar was the last stand of the Italian forces in Italian East Africa during the Second World War. The battle took place in November 1941, during the East African Campaign. Gondar was the main town of Amhara in ...

in November 1941. Until this time the partly Rhodesian-commanded Nigeria and Gold Coast Regiments remained in Abyssinia, patrolling and rounding up scattered Italian units. Around 250 officers and 1,000 other ranks from Southern Rhodesia remained in Kenya until mid-1943.

North Africa

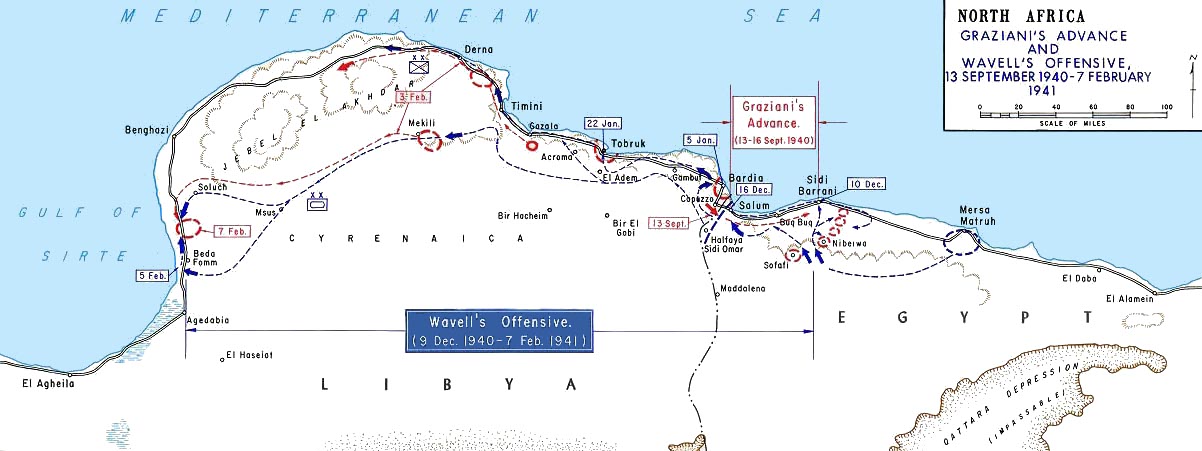

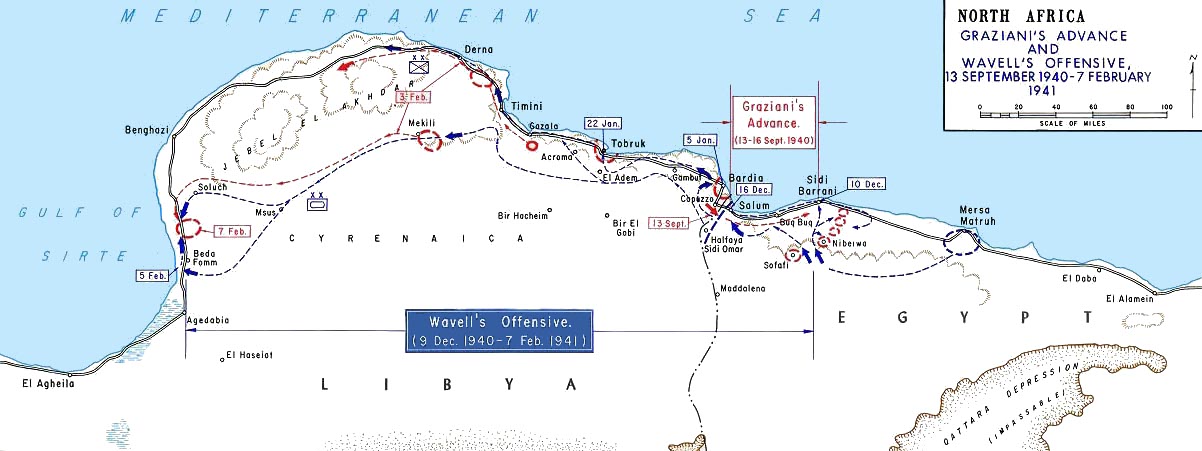

In North Africa, Rhodesians in the

In North Africa, Rhodesians in the 11th Hussars

The 11th Hussars (Prince Albert's Own) was a cavalry regiment of the British Army established in 1715. It saw service for three centuries including the First World War and Second World War but then amalgamated with the 10th Royal Hussars (Pri ...

, 2nd Leicesters, 1st Cheshires and other regiments contributed to Operation Compass

Operation Compass (also it, Battaglia della Marmarica) was the first large British military operation of the Western Desert Campaign (1940–1943) during the Second World War. British, Empire and Commonwealth forces attacked Italian forces of ...

between December 1940 and February 1941 as part of the Western Desert Force

The Western Desert Force (WDF) was a British Army formation (military), formation active in Egypt during the Western Desert Campaign of the World War II, Second World War.

On 17 June 1940, the headquarters of the 6th Infantry Division (United ...

under Major-General Richard O'Connor

General Sir Richard Nugent O'Connor, (21 August 1889 – 17 June 1981) was a senior British Army officer who fought in both the First and Second World Wars, and commanded the Western Desert Force in the early years of the Second World War. ...

, fighting at Sidi Barrani

Sidi Barrani ( ar, سيدي براني ) is a town in Egypt, near the Mediterranean Sea, about

east of the Egypt–Libya border, and around from Tobruk, Libya.

Named after Sidi es-Saadi el Barrani, a Senussi sheikh who was a head of i ...

, Bardia

Bardia, also El Burdi or Barydiyah ( ar, البردية, lit=, translit=al-Bardiyya or ) is a Mediterranean seaport in the Butnan District of eastern Libya, located near the border with Egypt. It is also occasionally called ''Bórdi Slemán''.

...

, Beda Fomm

Beda Fomm is a small coastal town in southwestern Cyrenaica, Libya. It is located between the much larger port city Benghazi to its north-west and the larger town of El Agheila further to the south-west. Beda Fomm is known mainly for being the s ...

and elsewhere. This offensive was extremely successful, with the Allies suffering very few casualties—around 700 killed and 2,300 wounded and missing—while capturing the strategic port Tobruk

Tobruk or Tobruck (; grc, Ἀντίπυργος, ''Antipyrgos''; la, Antipyrgus; it, Tobruch; ar, طبرق, Tubruq ''Ṭubruq''; also transliterated as ''Tobruch'' and ''Tubruk'') is a port city on Libya's eastern Mediterranean coast, near th ...

, over 100,000 Italian soldiers and most of Cyrenaica

Cyrenaica ( ) or Kyrenaika ( ar, برقة, Barqah, grc-koi, Κυρηναϊκή ��παρχίαKurēnaïkḗ parkhíā}, after the city of Cyrene), is the eastern region of Libya. Cyrenaica includes all of the eastern part of Libya between ...

. The Germans reacted by despatching the ''Afrika Korps

The Afrika Korps or German Africa Corps (, }; DAK) was the German expeditionary force in Africa during the North African Campaign of World War II. First sent as a holding force to shore up the Italian defense of its African colonies, the ...

'' under Erwin Rommel

Johannes Erwin Eugen Rommel () (15 November 1891 – 14 October 1944) was a German field marshal during World War II. Popularly known as the Desert Fox (, ), he served in the ''Wehrmacht'' (armed forces) of Nazi Germany, as well as servi ...

to shore up the Italian forces. Rommel led a strong counter-offensive in March–April 1941 that forced a general Allied withdrawal towards Egypt. German and Italian forces surrounded Tobruk but failed to take the largely Australian-garrisoned city, leading to the lengthy Siege of Tobruk

The siege of Tobruk lasted for 241 days in 1941, after Axis forces advanced through Cyrenaica from El Agheila in Operation Sonnenblume against Allied forces in Libya, during the Western Desert Campaign (1940–1943) of the Second World War. ...

.

The Rhodesian contingents in the 11th Hussars, Leicesters, Buffs, Argylls, Royal Northumberland Fusiliers

The Royal Northumberland Fusiliers was an infantry regiment of the British Army. Raised in 1674 as one of three 'English' units in the Dutch Anglo-Scots Brigade, it accompanied William III to England in the November 1688 Glorious Revolution an ...

, Durham Light Infantry

The Durham Light Infantry (DLI) was a light infantry regiment of the British Army in existence from 1881 to 1968. It was formed in 1881 under the Childers Reforms by the amalgamation of the 68th (Durham) Regiment of Foot (Light Infantry) and t ...

and Sherwood Foresters

The Sherwood Foresters (Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire Regiment) was a line infantry regiment of the British Army in existence for just under 90 years, from 1881 to 1970. In 1970, the regiment was amalgamated with the Worcestershire Regiment to f ...

were transferred ''en masse'' to Kenya in February 1941 to join the new Southern Rhodesian Reconnaissance Regiment, which served in East Africa over the following year. The Rhodesians in the 1st Cheshires moved with that regiment to Malta the same month. The Rhodesian Signallers were withdrawn to Cairo to form a section handling high-speed communications between Middle East Command and General Headquarters in England. The 2nd Black Watch, with its Rhodesian contingent, took part in the unsuccessful Allied defence of Crete in May–June 1941, then joined the garrison at Tobruk in August 1941. No. 237 (Rhodesia) Squadron was re-equipped with Hawker Hurricane

The Hawker Hurricane is a British single-seat fighter aircraft of the 1930s–40s which was designed and predominantly built by Hawker Aircraft Ltd. for service with the Royal Air Force (RAF). It was overshadowed in the public consciousness by ...

s the following month.

Rhodesians made up an integral component of the

Rhodesians made up an integral component of the Long Range Desert Group

)Gross, O'Carroll and Chiarvetto 2009, p.20

, patron =

, motto = ''Non Vi Sed Arte'' (Latin: ''Not by Strength, but by Guile'') (unofficial)

, colours =

, colours_label ...

(LRDG), a mechanised reconnaissance and raiding unit formed in North Africa in 1940 to operate behind enemy lines. Initially made up of New Zealanders, the unit's first British and Rhodesian members joined in November 1940. It was reorganised several times over the next year as it expanded and by the end of 1941 there were two Rhodesian patrols: S1 and S2 Patrols, B Squadron. Each vehicle bore a Rhodesian place-name starting with "S" on the bonnet, such as "Salisbury" or " Sabi". From April 1941 the LRDG was based at Kufra

Kufra () is a basinBertarelli (1929), p. 514. and oasis group in the Kufra District of southeastern Cyrenaica in Libya. At the end of nineteenth century Kufra became the centre and holy place of the Senussi order. It also played a minor role in ...

in south-eastern Libya. The Rhodesians were posted to Bir Harash, about to the north-east of Kufra, to patrol, hold the Zighen Gap and guard against a possible Axis attack from the north. For the next four months they lived in near-total isolation from the outside world, an exception coming in July 1941 when they and a group of airmen from No. 237 Squadron celebrated Rhodes Day together in the middle of the Cyrenaican desert.

In November 1941 the British Eighth Army, commanded by General Cunningham, launched Operation Crusader

Operation Crusader (18 November – 30 December 1941) was a military operation of the Western Desert Campaign during the Second World War by the British Eighth Army (United Kingdom), Eighth Army (with Commonwealth, Indian and Allied contingents) ...

in an attempt to relieve Tobruk. The British XXX Corps, led by the 7th Armoured Division ("the Desert Rats") with its Rhodesian platoons, would form the main body of attack, advancing west from Mersa Matruh

Mersa Matruh ( ar, مرسى مطروح, translit=Marsā Maṭrūḥ, ), also transliterated as ''Marsa Matruh'', is a port in Egypt and the capital of Matrouh Governorate. It is located west of Alexandria and east of Sallum on the main highway ...

, then sweeping around in a north-westerly direction towards Tobruk. The XIII Corps would concurrently advance north-west and cut off Axis forces on the coast at Sollum

Sallum ( ar, السلوم, translit=as-Sallūm various transliterations include ''El Salloum'', ''As Sallum'' or ''Sollum'') is a harbourside village or town in Egypt. It is along the Egypt/Libyan short north–south aligned coast of the Mediterra ...

and Bardia. When signalled the Tobruk garrison would break out and move south-east towards the advancing Allied forces. The operation was largely successful for the Allies, and the siege was broken. The Rhodesians of the LRDG took part in raids on Axis rear areas during the operation, ambushing Axis convoys, destroying Axis aircraft and pulling down telegraph poles and wires.

From late 1941 the LRDG co-operated closely with the newly formed Special Air Service

The Special Air Service (SAS) is a special forces unit of the British Army. It was founded as a regiment in 1941 by David Stirling and in 1950, it was reconstituted as a corps. The unit specialises in a number of roles including counter-terro ...

(SAS), which also included some Rhodesians. The Rhodesian LRDG patrols transported and supported SAS troops during operations behind Axis lines. The LRDG also maintained a constant "Road Watch" along the ''Via Balbia

Via or VIA may refer to the following:

Science and technology

* MOS Technology 6522, Versatile Interface Adapter

* ''Via'' (moth), a genus of moths in the family Noctuidae

* Via (electronics), a through-connection

* VIA Technologies, a Taiwan ...

'' on the north coast of Libya, along which almost all Axis road traffic from Tripoli

Tripoli or Tripolis may refer to:

Cities and other geographic units Greece

*Tripoli, Greece, the capital of Arcadia, Greece

* Tripolis (region of Arcadia), a district in ancient Arcadia, Greece

* Tripolis (Larisaia), an ancient Greek city in ...

, the main Libyan port, had to travel east. The LRDG set up a watch post about east of the Italian Marble Arch

The Marble Arch is a 19th-century white marble-faced triumphal arch in London, England. The structure was designed by John Nash (architect), John Nash in 1827 to be the state entrance to the cour d'honneur of Buckingham Palace; it stood near th ...

monument, and teams of two men each recorded Axis vehicle and troop movements in shifts throughout the day and night. This information was relayed back to the British commanders in Cairo.

Rommel advanced east from January 1942, and won a major victory over the Eighth Army, commanded by Lieutenant-General Neil Ritchie

General Sir Neil Methuen Ritchie, (29 July 1897 – 11 December 1983) was a British Army officer who saw service during both the world wars. He is most notable during the Second World War for commanding the British Eighth Army in the North Af ...

, at the Battle of Gazala

The Battle of Gazala (near the village of ) was fought during the Western Desert Campaign of the Second World War, west of the port of Tobruk in Libya, from 26 May to 21 June 1942. Axis troops of the ( Erwin Rommel) consisting of German and I ...

in May–June 1942. The Axis soon thereafter captured Tobruk. During the Axis victory at the "Retma Box"—part of the British-devised system whereby isolated, strongly fortified "boxes", each manned by a brigade group, formed the front line—and the subsequent Allied retreat, the Southern Rhodesian Anti-Tank Battery lost five men killed, nine wounded and two missing; 37 were captured. Rommel's advance was stalled in July by the Eighth Army, now headed by General Claude Auchinleck

Field Marshal Sir Claude John Eyre Auchinleck, (21 June 1884 – 23 March 1981), was a British Army commander during the Second World War. He was a career soldier who spent much of his military career in India, where he rose to become Commande ...

, at the First Battle of El Alamein

The First Battle of El Alamein (1–27 July 1942) was a battle of the Western Desert campaign of the Second World War, fought in Egypt between Axis (German and Italian) forces of the Panzer Army Africa—which included the under Field Marshal ...

in western Egypt. Two months later the Rhodesians of the LRDG took part in Operation Bigamy

Operation Bigamy ''a.k.a. Operation Snowdrop'' was a raid during the Second World War by the Special Air Service in September 1942 under the command of Lieutenant Colonel David Stirling and supported by the Long Range Desert Group. The plan was ...

(aka Operation Snowdrop), an unsuccessful attempt by the SAS and LRDG to raid Benghazi

Benghazi () , ; it, Bengasi; tr, Bingazi; ber, Bernîk, script=Latn; also: ''Bengasi'', ''Benghasi'', ''Banghāzī'', ''Binghāzī'', ''Bengazi''; grc, Βερενίκη (''Berenice'') and ''Hesperides''., group=note (''lit. Son of he Ghazi ...

harbour. The SAS raiding force, headed by Lieutenant-Colonel David Stirling

Sir Archibald David Stirling (15 November 1915 – 4 November 1990) was a Scottish officer in the British army, a mountaineer, and the founder and creator of the Special Air Service (SAS). He saw active service during the Second World War.

...

, was discovered by an Italian reconnaissance unit, prompting Stirling to turn back to Kufra. The Rhodesians, meanwhile, were led into impassable country by a local guide, and swiftly retreated after being attacked by German bombers.

Southern Rhodesian pilots played a part in the siege of Malta during 1942. John Plagis

Ioannis Agorastos "John" Plagis,., group=n, name=greek DSO, DFC & Bar (1919–1974) was a Southern Rhodesian flying ace in the Royal Air Force (RAF) during the Second World War, noted especially for his part in the defence of Malta during 1942 ...

, a Rhodesian airman of Greek ancestry, joined the multinational group of Allied airmen defending the strategically important island in late March and on 1 April achieved four aerial victories in an afternoon, thereby becoming the siege's first Spitfire

The Supermarine Spitfire is a British single-seat fighter aircraft used by the Royal Air Force and other Allied countries before, during, and after World War II. Many variants of the Spitfire were built, from the Mk 1 to the Rolls-Royce Griff ...

flying ace

A flying ace, fighter ace or air ace is a military aviator credited with shooting down five or more enemy aircraft during aerial combat. The exact number of aerial victories required to officially qualify as an ace is varied, but is usually co ...

. By the time of his withdrawal in July he had been awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross twice. The British finally delivered vital supplies to Malta on 15 August with Operation Pedestal

Operation Pedestal ( it, Battaglia di Mezzo Agosto, Battle of mid-August), known in Malta as (), was a British operation to carry supplies to the island of Malta in August 1942, during the Second World War. Malta was a base from which British ...

.

Back in Salisbury, the Southern Rhodesian government was coming under pressure from Britain to put its armed forces under the purview of a regional command. Huggins decided in late October 1942 to join a unified Southern African Command headed by South Africa's Jan Smuts

Field Marshal Jan Christian Smuts, (24 May 1870 11 September 1950) was a South African statesman, military leader and philosopher. In addition to holding various military and cabinet posts, he served as prime minister of the Union of South Af ...

. This choice was motivated by a combination of strategic concerns and geopolitical manoeuvring. Apart from considering South Africa a more appropriate partner in geographical, logistical and cultural terms, Huggins feared that the alternative—joining the British East Africa Command

East Africa Command was a Command of the British Army. Until 1947 it was under the direct control of the Army Council and thereafter it became the responsibility of Middle East Command. It was disbanded on 11 December 1963, the day before Kenya bec ...

—might detract from the autonomous nature of Southern Rhodesia's war effort, with possible constitutional implications. A shift in the deployment of the colony's troops duly occurred. For the rest of the war the majority of Rhodesian servicemen went into the field integrated into South African formations, prominently the 6th Armoured Division.

El Alamein

The decisive victory of Lieutenant-General

The decisive victory of Lieutenant-General Bernard Montgomery

Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery, 1st Viscount Montgomery of Alamein, (; 17 November 1887 – 24 March 1976), nicknamed "Monty", was a senior British Army officer who served in the First World War, the Irish War of Independence and t ...

's Eighth Army over the Germans and Italians at the Second Battle of El Alamein

The Second Battle of El Alamein (23 October – 11 November 1942) was a battle of the Second World War that took place near the Egyptian Railway station, railway halt of El Alamein. The First Battle of El Alamein and the Battle of Alam el Halfa ...

in October–November 1942 turned the tide of the North African war strongly in favour of the Allies, and did much to revive Allied morale. The Rhodesians of the KRRC took part in the battle as part of the 7th Armoured Division under the XIII Corps, forming part of the initial thrust in the southern sector.

The Rhodesian Anti-Tank Battery under Major Guy Savory also fought at El Alamein, supporting the Australian 9th Division as part of the XXX Corps. The fighting around "Thompson's Post" between 1 and 3 November was some of the fiercest Rhodesians took part in during the war. Hoping to knock out the Allied anti-tank guns before counter-attacking, the Germans concentrated intense artillery fire on the Australian and Rhodesian guns before advancing 12 Panzer IV

The ''Panzerkampfwagen'' IV (Pz.Kpfw. IV), commonly known as the ''Panzer'' IV, was a German medium tank developed in the late 1930s and used extensively during the Second World War. Its ordnance inventory designation was Sd.Kfz. 161.

The Panze ...

tanks towards the weakest point of the Australian line. The Australian six-pounders had been largely disabled by the bombardment but most of the Rhodesian guns remained operational. The Rhodesian gunners disabled two Panzers and seriously damaged two more, compelling an Axis retreat, and held their position until being relieved on 3 November. One Rhodesian officer and seven other ranks were killed and more than double that number were wounded. For his actions at Thompson's Post, Sergeant J A Hotchin received the Distinguished Conduct Medal

The Distinguished Conduct Medal was a decoration established in 1854 by Queen Victoria for gallantry in the field by other ranks of the British Army. It is the oldest British award for gallantry and was a second level military decoration, ranki ...

; Lieutenants R J Bawden and H R C Callon won the Military Cross

The Military Cross (MC) is the third-level (second-level pre-1993) military decoration awarded to officers and (since 1993) other ranks of the British Armed Forces, and formerly awarded to officers of other Commonwealth countries.

The MC i ...

and Trooper P Vorster the Military Medal

The Military Medal (MM) was a military decoration awarded to personnel of the British Army and other arms of the armed forces, and to personnel of other Commonwealth countries, below commissioned rank, for bravery in battle on land. The award ...

.

The KRRC Rhodesians were in the forefront of the Allied column pursuing the retreating Axis forces after El Alamein, advancing through Tobruk, Gazala and Benghazi before reaching El Agheila

El Agheila ( ar, العقيلة, translit=al-ʿUqayla ) is a coastal city at the southern end of the Gulf of Sidra in far western Cyrenaica, Libya. In 1988 it was placed in Ajdabiya District; it was in that district until 1995. It was removed from ...

on 24 November 1942. They patrolled around the Axis right flank until being withdrawn to Timimi

Timimi, At Timimi ( ar, التميمي) or Tmimi, is a small village in Libya about 75 km east of Derna, Libya, Derna and 100 km west of Tobruk. It is on the eastern shores of the Libyan coastline of the Mediterranean Sea.

Geography

Beca ...

in December. Tripoli

Tripoli or Tripolis may refer to:

Cities and other geographic units Greece

*Tripoli, Greece, the capital of Arcadia, Greece

* Tripolis (region of Arcadia), a district in ancient Arcadia, Greece

* Tripolis (Larisaia), an ancient Greek city in ...

fell to the Eighth Army on 23 January 1943, and six days later Allied forces reached Tunisia's south-eastern frontier, where Italian and German forces manned the Mareth Line

The Mareth Line was a system of fortifications built by France in southern Tunisia in the late 1930s. The line was intended to protect Tunisia against an Italian invasion from its colony in Libya. The line occupied a point where the routes into T ...

, a series of fortifications built by the French in the 1930s.

Tunisia

Tunisia Campaign

The Tunisian campaign (also known as the Battle of Tunisia) was a series of battles that took place in Tunisia during the North African campaign of the World War II, Second World War, between Axis powers, Axis and Allies of World War II, Allied ...

, the second being to the north-west, where the British First Army and American II Corps, firmly established in formerly Vichy

Vichy (, ; ; oc, Vichèi, link=no, ) is a city in the Allier Departments of France, department in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region of central France, in the historic province of Bourbonnais.

It is a Spa town, spa and resort town and in World ...

-held Morocco and Algeria following Operation Torch

Operation Torch (8 November 1942 – Run for Tunis, 16 November 1942) was an Allies of World War II, Allied invasion of French North Africa during the Second World War. Torch was a compromise operation that met the British objective of secu ...

in November 1942, were gradually pushing the Axis forces under Hans-Jürgen von Arnim

Hans-Jürgen Bernard Theodor von Arnim (; 4 April 1889 – 1 September 1962) was a German general in the Nazi Wehrmacht during World War II who commanded several armies. He was a recipient of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross. Early life ...

back towards Tunis

''Tounsi'' french: Tunisois

, population_note =

, population_urban =

, population_metro = 2658816

, population_density_km2 =

, timezone1 = CET

, utc_offset1 ...

. After von Arnim won a decisive victory over the Americans at the Battle of Sidi Bou Zid

The Battle of Sidi Bou Zid /Operation Spring Breeze) took place during the Tunisia Campaign from 14–17 February 1943, in World War II. The battle was fought around Sidi Bou Zid, where a large number of US Army units were mauled by German and It ...

in mid-February 1943, destroying over 100 US tanks, the Eighteenth Army Group was formed under the British General Harold Alexander

Harold Rupert Leofric George Alexander, 1st Earl Alexander of Tunis, (10 December 1891 – 16 June 1969) was a senior British Army officer who served with distinction in both the First and the Second World War and, afterwards, as Governor Ge ...

to co-ordinate the actions of the Allied forces on both Tunisian fronts.

The Eighth Army under Montgomery spent February at Medinine in south-eastern Tunisia. Expecting an imminent attack by the Axis, the Eighth Army mustered every anti-tank gun it could from Egypt and Libya. The 102nd (Northumberland Hussars) Anti-Tank Regiment, including the Rhodesian Anti-Tank Battery under Major Savory, duly advanced west from Benghazi and reached the front on 5 March 1943. The Germans and Italians assaulted Medinine the next day, but failed to make much progress and abandoned their attack by the evening. The Rhodesian gunners, held in reserve, did not take part in the engagement but were attacked from the air. The Rhodesians of the KRRC, now under the 7th Motor Brigade, moved up from Libya during early March. No. 237 (Rhodesia) Squadron, which had spent 1942 and the first months of 1943 in Iran and Iraq, returned to North Africa the same month, with the future Prime Minister Ian Smith

Ian Douglas Smith (8 April 1919 – 20 November 2007) was a Rhodesian politician, farmer, and fighter pilot who served as Prime Minister of Rhodesia (known as Southern Rhodesia until October 1964 and now known as Zimbabwe) from 1964 to ...

in its ranks as a Hurricane pilot.

Montgomery launched his major assault on the Mareth Line, Operation Pugilist

The Battle of the Mareth Line or the Battle of Mareth was an attack in the Second World War by the British Eighth Army (General Bernard Montgomery) in Tunisia, against the Mareth Line held by the Italo-German 1st Army (General Giovanni Messe). I ...

, on 16 March. The Rhodesian Anti-Tank Battery, operating with the 50th (Northumbrian) Infantry Division, took part. The Allies advanced at first but the weather and terrain prevented the tanks and guns from moving forward, allowing the 15th Panzer Division to counter-attack successfully. A flanking movement by the 2nd New Zealand Division

The 2nd New Zealand Division, initially the New Zealand Division, was an infantry Division (military), division of the New Zealand Army, New Zealand Military Forces (New Zealand's army) during the World War II, Second World War. The division was ...

around the right of the German forces, through the Tebaga Gap, compelled an Axis withdrawal on 27 March. The Rhodesian anti-tank gunners fought their last action in Africa at Enfidaville, south of Tunis, on 20 April. The KRRC Rhodesians meanwhile took part in a long outflanking march which brought them to El Arousse, south-west of Tunis, the next day. British armour entered Tunis on 7 May 1943. The Axis forces in North Africa—over 220,000 Germans and Italians, including 26 generals—surrendered a week later.

By time Tunis had fallen, few Rhodesians remained with the First or Eighth Armies; most were transferring to the South African 6th Armoured Division, then in Egypt, or making their way home on leave. Out of the 300 Southern Rhodesians who had joined the KRRC in Egypt, only three officers and 109 other ranks remained at the end of the Tunisian Campaign. The Rhodesian Anti-Tank Battery retraced many of the movements it had taken during the campaign as it returned to Egypt. "Left for Matruh at 0830 hours today," one Rhodesian gunner wrote. "Camped at night on the identical spot where we camped in June 1941. It gave me a queer feeling to look back and think how many of us are missing."

Dodecanese

Southern Rhodesia was represented in the Dodecanese Campaign of September–November 1943 by the Long Range Desert Group, which was withdrawn from the North African front in March 1943. After retraining for mountain operations in Lebanon, the LRDG moved in late September to the

Southern Rhodesia was represented in the Dodecanese Campaign of September–November 1943 by the Long Range Desert Group, which was withdrawn from the North African front in March 1943. After retraining for mountain operations in Lebanon, the LRDG moved in late September to the Dodecanese

The Dodecanese (, ; el, Δωδεκάνησα, ''Dodekánisa'' , ) are a group of 15 larger plus 150 smaller Greek islands in the southeastern Aegean Sea and Eastern Mediterranean, off the coast of Turkey's Anatolia, of which 26 are inhabited. ...

island of Kalymnos

Kalymnos ( el, Κάλυμνος) is a Greek island and municipality in the southeastern Aegean Sea. It belongs to the Dodecanese island chain, between the islands of Kos (south, at a distance of ) and Leros (north, at a distance of less than ): t ...

, north-west of Kos

Kos or Cos (; el, Κως ) is a Greek island, part of the Dodecanese island chain in the southeastern Aegean Sea. Kos is the third largest island of the Dodecanese by area, after Rhodes and Karpathos; it has a population of 36,986 (2021 census), ...

and south-east of Leros

Leros ( el, Λέρος) is a Greek island and municipality in the Dodecanese in the southern Aegean Sea. It lies (171 nautical miles) from Athens's port of Piraeus, from which it can be reached by an 9-hour ferry ride or by a 45-minute flight fr ...

, off the coast of south-west Turkey. In the fall-out from the Armistice of Cassibile

The Armistice of Cassibile was an armistice signed on 3 September 1943 and made public on 8 September between the Kingdom of Italy and the Allies during World War II.

It was signed by Major General Walter Bedell Smith for the Allies and Brig ...