Smilodon on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Smilodon'' is a

During the 1830s, Danish naturalist Peter Wilhelm Lund and his assistants collected fossils in the

During the 1830s, Danish naturalist Peter Wilhelm Lund and his assistants collected fossils in the  Fossils of ''Smilodon'' were discovered in North America from the second half of the 19th century onwards. In 1869, American paleontologist Joseph Leidy described a

Fossils of ''Smilodon'' were discovered in North America from the second half of the 19th century onwards. In 1869, American paleontologist Joseph Leidy described a

Long the most completely known

Long the most completely known  The earliest felids are known from the

The earliest felids are known from the

''Smilodon'' was around the size of modern

''Smilodon'' was around the size of modern  ''S. gracilis'' was the smallest species, estimated at in weight, about the size of a

''S. gracilis'' was the smallest species, estimated at in weight, about the size of a  Traditionally, saber-toothed cats have been artistically restored with external features similar to those of extant felids, by artists such as

Traditionally, saber-toothed cats have been artistically restored with external features similar to those of extant felids, by artists such as

genus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus comes above species and below family. In binomial nom ...

of the extinct machairodont subfamily of the felids. It is one of the most famous prehistoric mammals and the best known saber-toothed cat. Although commonly known as the saber-toothed tiger, it was not closely related to the tiger

The tiger (''Panthera tigris'') is the largest living Felidae, cat species and a member of the genus ''Panthera''. It is most recognisable for its dark vertical stripes on orange fur with a white underside. An apex predator, it primarily pr ...

or other modern cats. ''Smilodon'' lived in the Americas

The Americas, which are sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North America, North and South America. The Americas make up most of the land in Earth's Western Hemisphere and comprise the New World. ...

during the Pleistocene

The Pleistocene ( , often referred to as the ''Ice age'') is the geological Epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 2,580,000 to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was fina ...

epoch (2.5 mya – 10,000 years ago). The genus was named in 1842 based on fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

s from Brazil; the generic name means "scalpel" or "two-edged knife" combined with "tooth". Three species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriat ...

are recognized today: ''S. gracilis'', ''S. fatalis'', and ''S. populator''. The two latter species were probably descended from ''S. gracilis'', which itself probably evolved from '' Megantereon''. The hundreds of individuals obtained from the La Brea Tar Pits

La Brea Tar Pits is an active paleontological research site in urban Los Angeles. Hancock Park was formed around a group of tar pits where natural asphalt (also called asphaltum, bitumen, or pitch; ''brea'' in Spanish) has seeped up from the gr ...

in Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the largest city in the state of California and the second most populous city in the United States after New York City, as well as one of the world ...

constitute the largest collection of ''Smilodon'' fossils.

Overall, ''Smilodon'' was more robustly built than any extant

Extant is the opposite of the word extinct. It may refer to:

* Extant hereditary titles

* Extant literature, surviving literature, such as ''Beowulf'', the oldest extant manuscript written in English

* Extant taxon, a taxon which is not extinct, ...

cat, with particularly well-developed forelimbs and exceptionally long upper canine teeth. Its jaw had a bigger gape than that of modern cats, and its upper canines were slender and fragile, being adapted for precision killing. ''S. gracilis'' was the smallest species at in weight. ''S. fatalis'' had a weight of and height of . Both of these species are mainly known from North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and th ...

, but remains from South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the sou ...

have also been attributed to them. ''S. populator'' from South America was the largest species, at in weight and in height, and was among the largest known felids. The coat

A coat typically is an outer garment for the upper body as worn by either gender for warmth or fashion. Coats typically have long sleeves and are open down the front and closing by means of buttons, zippers, hook-and-loop fasteners, toggles, ...

pattern of ''Smilodon'' is unknown, but it has been artistically restored with plain or spotted patterns.

In North America, ''Smilodon'' hunted large herbivore

A herbivore is an animal anatomically and physiologically adapted to eating plant material, for example foliage or marine algae, for the main component of its diet. As a result of their plant diet, herbivorous animals typically have mouthpar ...

s such as bison

Bison are large bovines in the genus ''Bison'' (Greek: "wild ox" (bison)) within the tribe Bovini. Two extant and numerous extinct species are recognised.

Of the two surviving species, the American bison, ''B. bison'', found only in North A ...

and camels

A camel (from: la, camelus and grc-gre, κάμηλος (''kamēlos'') from Hebrew or Phoenician: גָמָל ''gāmāl''.) is an even-toed ungulate in the genus ''Camelus'' that bears distinctive fatty deposits known as "humps" on its back. ...

, and it remained successful even when encountering new prey species in South America. ''Smilodon'' is thought to have killed its prey by holding it still with its forelimbs and biting it, but it is unclear in what manner the bite itself was delivered. Scientists debate whether ''Smilodon'' had a social or a solitary lifestyle; analysis of modern predator behavior as well as of ''Smilodon''s fossil remains could be construed to lend support to either view. ''Smilodon'' probably lived in closed habitats such as forests and bush, which would have provided cover for ambushing prey. ''Smilodon'' died out at the same time that most North and South American megafauna

In terrestrial zoology, the megafauna (from Greek μέγας ''megas'' "large" and New Latin ''fauna'' "animal life") comprises the large or giant animals of an area, habitat, or geological period, extinct and/or extant. The most common thresho ...

disappeared, about 10,000 years ago. Its reliance on large animals has been proposed as the cause of its extinction, along with climate change and competition with other species, but the exact cause is unknown.

Taxonomy

During the 1830s, Danish naturalist Peter Wilhelm Lund and his assistants collected fossils in the

During the 1830s, Danish naturalist Peter Wilhelm Lund and his assistants collected fossils in the calcareous

Calcareous () is an adjective meaning "mostly or partly composed of calcium carbonate", in other words, containing lime or being chalky. The term is used in a wide variety of scientific disciplines.

In zoology

''Calcareous'' is used as an ad ...

caves near the small town of Lagoa Santa, Minas Gerais, Brazil. Among the thousands of fossils found, he recognized a few isolated cheek teeth

Cheek teeth or post-canines comprise the molar and premolar teeth in mammals. Cheek teeth are multicuspidate (having many folds or tubercles). Mammals have multicuspidate molars (three in placentals, four in marsupials, in each jaw quadrant) and p ...

as belonging to a hyena

Hyenas, or hyaenas (from Ancient Greek , ), are feliform carnivoran mammals of the family Hyaenidae . With only four extant species (each in its own genus), it is the fifth-smallest family in the Carnivora and one of the smallest in the cl ...

, which he named ''Hyaena neogaea'' in 1839. After more material was found (including canine teeth and foot bones), Lund concluded the fossils instead belonged to a distinct genus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus comes above species and below family. In binomial nom ...

of felid, though transitional to the hyenas. He stated it would have matched the largest modern predators in size, and was more robust than any modern cat. Lund originally wanted to name the new genus '' Hyaenodon'', but realizing this had recently become preoccupied by another prehistoric predator, he instead named it ''Smilodon populator'' in 1842. He explained the Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic pe ...

meaning of ''Smilodon'' as (''smilē''), "scalpel" or "two-edged knife", and ''οδόντος'' (''odóntos''), "tooth". This has also been translated as "tooth shaped like double-edged knife". He explained the species name ''populator'' as "the destroyer", which has also been translated as "he who brings devastation". By 1846, Lund had acquired nearly every part of the skeleton (from different individuals), and more specimens were found in neighboring countries by other collectors in the following years. Though some later authors used Lund's original species name ''neogaea'' instead of ''populator'', it is now considered an invalid ''nomen nudum

In taxonomy, a ''nomen nudum'' ('naked name'; plural ''nomina nuda'') is a designation which looks exactly like a scientific name of an organism, and may have originally been intended to be one, but it has not been published with an adequate desc ...

'' ("naked name"), as it was not accompanied with a proper description and no type specimens were designated. Some South American specimens have been referred to other genera, subgenera, species, and subspecies

In biological classification, subspecies is a rank below species, used for populations that live in different areas and vary in size, shape, or other physical characteristics ( morphology), but that can successfully interbreed. Not all specie ...

, such as ''Smilodontidion riggii'', ''Smilodon'' (''Prosmilodon'') ''ensenadensis'', and ''S. bonaeriensis'', but these are now thought to be junior synonyms of ''S. populator''.

Fossils of ''Smilodon'' were discovered in North America from the second half of the 19th century onwards. In 1869, American paleontologist Joseph Leidy described a

Fossils of ''Smilodon'' were discovered in North America from the second half of the 19th century onwards. In 1869, American paleontologist Joseph Leidy described a maxilla

The maxilla (plural: ''maxillae'' ) in vertebrates is the upper fixed (not fixed in Neopterygii) bone of the jaw formed from the fusion of two maxillary bones. In humans, the upper jaw includes the hard palate in the front of the mouth. T ...

fragment with a molar, which had been discovered in a petroleum bed in Hardin County, Texas. He referred the specimen to the genus '' Felis'' (which was then used for most cats, extant as well as extinct) but found it distinct enough to be part of its own subgenus

In biology, a subgenus (plural: subgenera) is a taxonomic rank directly below genus.

In the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature, a subgeneric name can be used independently or included in a species name, in parentheses, placed between ...

, as ''F.'' (''Trucifelis'') ''fatalis''. The species name means "deadly". In an 1880 article about extinct American cats, American paleontologist Edward Drinker Cope

Edward Drinker Cope (July 28, 1840 – April 12, 1897) was an American zoologist, paleontologist, comparative anatomist, herpetologist, and ichthyologist. Born to a wealthy Quaker family, Cope distinguished himself as a child prodigy interes ...

pointed out that the ''F. fatalis'' molar was identical to that of ''Smilodon'', and he proposed the new combination ''S. fatalis''. Most North American finds were scanty until excavations began in the La Brea Tar Pits

La Brea Tar Pits is an active paleontological research site in urban Los Angeles. Hancock Park was formed around a group of tar pits where natural asphalt (also called asphaltum, bitumen, or pitch; ''brea'' in Spanish) has seeped up from the gr ...

in Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the largest city in the state of California and the second most populous city in the United States after New York City, as well as one of the world ...

, where hundreds of individuals of ''S. fatalis'' have been found since 1875. ''S. fatalis'' has junior synonyms such as ''S. mercerii'', ''S. floridanus'', and ''S. californicus''. American paleontologist Annalisa Berta considered the holotype of ''S. fatalis'' too incomplete to be an adequate type specimen, and the species has at times been proposed to be a junior synonym of ''S. populator''. Nordic paleontologists Björn Kurtén and Lars Werdelin

Lars Werdelin (born 1955) is a Swedish paleontologist specializing in the evolution of mammalian carnivores. One area of interest has been the evolutionary interaction of carnivores and hominins in Africa.

He received his Ph.D. from Stockholm Univ ...

supported the distinctness of the two species in an article published in 1990. A 2018 article by the American paleontologist John P. Babiarz and colleagues concluded that ''S. californicus'', represented by the specimens from the La Brea Tar Pits, was a distinct species from ''S. fatalis'' after all and that more research is needed to clarify the taxonomy of the lineage.

In his 1880 article about extinct cats, Cope also named a third species of ''Smilodon'', ''S. gracilis''. The species was based on a partial canine, which had been obtained in the Port Kennedy Cave near the Schuylkill River

The Schuylkill River ( , ) is a river running northwest to southeast in eastern Pennsylvania. The river was improved by navigations into the Schuylkill Canal, and several of its tributaries drain major parts of Pennsylvania's Coal Region. It f ...

in Pennsylvania. Cope found the canine to be distinct from that of the other ''Smilodon'' species due to its smaller size and more compressed base. Its specific name refers to the species' lighter build. This species is known from fewer and less complete remains than the other members of the genus. ''S. gracilis'' has at times been considered part of genera such as '' Megantereon'' and '' Ischyrosmilus''. ''S. populator'', ''S. fatalis'' and ''S. gracilis'' are currently considered the only valid species of ''Smilodon'', and features used to define most of their junior synonyms have been dismissed as variation between individuals of the same species (intraspecific variation). One of the most famous of prehistoric mammals, ''Smilodon'' has often been featured in popular media and is the state fossil

Most American states have made a state fossil designation, in many cases during the 1980s. It is common to designate one species in which fossilization has occurred, rather than a single specimen, or a category of fossils not limited to a single ...

of California.

Evolution

Long the most completely known

Long the most completely known saber-toothed cat

Machairodontinae is an extinct subfamily of carnivoran mammals of the family Felidae (true cats). They were found in Asia, Africa, North America, South America, and Europe from the Miocene to the Pleistocene, living from about 16 million ...

, ''Smilodon'' is still one of the best-known members of the group, to the point where the two concepts have been confused. The term "saber-tooth" refers to an ecomorph consisting of various groups of extinct predatory synapsids (mammals and close relatives), which convergently evolved

Convergent evolution is the independent evolution of similar features in species of different periods or epochs in time. Convergent evolution creates analogous structures that have similar form or function but were not present in the last com ...

extremely long maxillary canine

In human dentistry, the maxillary canine is the tooth located laterally (away from the midline of the face) from both maxillary lateral incisors of the mouth but mesial (toward the midline of the face) from both maxillary first premolars. Both ...

s, as well as adaptations to the skull and skeleton related to their use. This includes members of Gorgonopsia, Thylacosmilidae

Thylacosmilidae is an extinct family of metatherian predators, related to the modern marsupials, which lived in South America between the Miocene and Pliocene epochs. Like other South American mammalian predators that lived prior to the Grea ...

, Machaeroidinae, Nimravidae, Barbourofelidae

Barbourofelidae is an extinct family of carnivorans of the suborder Feliformia, sometimes known as false saber-toothed cats, that lived in North America, Eurasia and Africa during the Miocene epoch (16.9—9.0 million years ago) and existed for a ...

, and Machairodontinae

Machairodontinae is an extinct subfamily of carnivoran mammals of the family Felidae (true cats). They were found in Asia, Africa, North America, South America, and Europe from the Miocene to the Pleistocene, living from about 16 million unti ...

. Within the family Felidae

Felidae () is the family of mammals in the order Carnivora colloquially referred to as cats, and constitutes a clade. A member of this family is also called a felid (). The term "cat" refers both to felids in general and specifically to the dom ...

(true cats), members of the subfamily

In biological classification, a subfamily (Latin: ', plural ') is an auxiliary (intermediate) taxonomic rank, next below family but more inclusive than genus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classifica ...

Machairodontinae are referred to as saber-toothed cats, and this group is itself divided into three tribes

The term tribe is used in many different contexts to refer to a category of human social group. The predominant worldwide usage of the term in English is in the discipline of anthropology. This definition is contested, in part due to confli ...

: Metailurini (false saber-tooths); Homotherini (scimitar

A scimitar ( or ) is a single-edged sword with a convex curved blade associated with Middle Eastern, South Asian, or North African cultures. A European term, ''scimitar'' does not refer to one specific sword type, but an assortment of different ...

-toothed cats); and Smilodontini ( dirk-toothed cats), to which ''Smilodon'' belongs. Members of Smilodontini are defined by their long slender canines with fine to no serration

Serration is a saw-like appearance or a row of sharp or tooth-like projections. A serrated cutting edge has many small points of contact with the material being cut. By having less contact area than a smooth blade or other edge, the applied p ...

s, whereas Homotherini are typified by shorter, broad, and more flattened canines, with coarser serrations. Members of Metailurini were less specialized and had shorter, less flattened canines, and are not recognized as members of Machairodontinae by some researchers.

The earliest felids are known from the

The earliest felids are known from the Oligocene

The Oligocene ( ) is a geologic epoch of the Paleogene Period and extends from about 33.9 million to 23 million years before the present ( to ). As with other older geologic periods, the rock beds that define the epoch are well identified but t ...

of Europe, such as '' Proailurus'', and the earliest one with saber-tooth features is the Miocene

The Miocene ( ) is the first geological epoch of the Neogene Period and extends from about (Ma). The Miocene was named by Scottish geologist Charles Lyell; the name comes from the Greek words (', "less") and (', "new") and means "less recen ...

genus '' Pseudaelurus''. The skull and mandible morphology of the earliest saber-toothed cats was similar to that of the modern clouded leopards (''Neofelis''). The lineage further adapted to the precision killing of large animals by developing elongated canine teeth and wider gapes, in the process sacrificing high bite force. As their canines became longer, the bodies of the cats became more robust for immobilizing prey. In derived

Derive may refer to:

*Derive (computer algebra system), a commercial system made by Texas Instruments

* ''Dérive'' (magazine), an Austrian science magazine on urbanism

*Dérive, a psychogeographical concept

See also

*

*Derivation (disambiguation ...

smilodontins and homotherins, the lumbar

In tetrapod

Tetrapods (; ) are four-limbed vertebrate animals constituting the superclass Tetrapoda (). It includes extant and extinct amphibians, sauropsids ( reptiles, including dinosaurs and therefore birds) and synapsids ( pelycosa ...

region of the spine and the tail became shortened, as did the hind limbs. Based on mitochondrial DNA

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA or mDNA) is the DNA located in mitochondria, cellular organelles within eukaryotic cells that convert chemical energy from food into a form that cells can use, such as adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Mitochondrial D ...

sequences extracted from fossils, the lineages of ''Homotherium

''Homotherium'', also known as the scimitar-toothed cat or scimitar cat, is an extinct genus of machairodontine saber-toothed predator, often termed scimitar-toothed cats, that inhabited North America, South America, Eurasia, and Africa during ...

'' and ''Smilodon'' are estimated to have diverged about 18 Ma ago. The earliest species of ''Smilodon'' is ''S. gracilis'', which existed from 2.5 million

One million (1,000,000), or one thousand thousand, is the natural number following 999,999 and preceding 1,000,001. The word is derived from the early Italian ''millione'' (''milione'' in modern Italian), from ''mille'', "thousand", plus the a ...

to 500,000 years ago (early Blancan

The Blancan North American Stage on the geologic timescale is the North American faunal stage according to the North American Land Mammal Ages chronology (NALMA), typically set from 4,750,000 to 1,806,000 years BP, a period of .Irvingtonian

The Irvingtonian North American Land Mammal Age on the geologic timescale is the North American faunal stage according to the North American Land Mammal Ages chronology (NALMA), spanning from 1.9 million – 250,000 years BP.

ages) and was the successor in North America of ''Megantereon'', from which it probably evolved. ''Megantereon'' itself had entered North America from Eurasia

Eurasia (, ) is the largest continental area on Earth, comprising all of Europe and Asia. Primarily in the Northern and Eastern Hemispheres, it spans from the British Isles and the Iberian Peninsula in the west to the Japanese archipelag ...

during the Pliocene

The Pliocene ( ; also Pleiocene) is the epoch in the geologic time scale that extends from 5.333 million to 2.58Early Pleistocene

The Early Pleistocene is an unofficial sub-epoch in the international geologic timescale in chronostratigraphy, being the earliest division of the Pleistocene Epoch within the ongoing Quaternary Period. It is currently estimated to span the time ...

as part of the Great American Interchange

The Great American Biotic Interchange (commonly abbreviated as GABI), also known as the Great American Interchange and the Great American Faunal Interchange, was an important late Cenozoic paleozoogeographic biotic interchange event in which lan ...

. ''S. fatalis'' existed 1.6 million–10,000 years ago (late Irvingtonian to Rancholabrean ages), and replaced ''S. gracilis'' in North America. ''S. populator'' existed 1 million–10,000 years ago (Ensenadan

The Ensenadan age is a period of geologic time (1.2–0.8 Ma) within the Early Pleistocene epoch of the Quaternary used more specifically with South American Land Mammal Ages. It follows the Uquian and precedes the Lujanian

The Lujanian age is a ...

to Lujanian ages); it occurred in the eastern parts of South America.

Despite the colloquial name "saber-toothed tiger", ''Smilodon'' is not closely related to the modern tiger

The tiger (''Panthera tigris'') is the largest living Felidae, cat species and a member of the genus ''Panthera''. It is most recognisable for its dark vertical stripes on orange fur with a white underside. An apex predator, it primarily pr ...

(which belongs in the subfamily Pantherinae), or any other extant felid. A 1992 ancient DNA analysis suggested that ''Smilodon'' should be grouped with modern cats (subfamilies Felinae

The Felinae are a subfamily of the family Felidae. This subfamily comprises the small cats having a bony hyoid, because of which they are able to purr but not roar.

Other authors have proposed an alternative definition for this subfamily: a ...

and Pantherinae). A 2005 study found that ''Smilodon'' belonged to a separate lineage. A study published in 2006 confirmed this, showing that the Machairodontinae diverged early from the ancestors of modern cats and were not closely related to any living species. The following cladogram

A cladogram (from Greek ''clados'' "branch" and ''gramma'' "character") is a diagram used in cladistics to show relations among organisms. A cladogram is not, however, an evolutionary tree because it does not show how ancestors are related to ...

based on fossils and DNA analysis shows the placement of ''Smilodon'' among extinct and extant felids, after Rincón and colleagues, 2011:

Description

big cat

The term "big cat" is typically used to refer to any of the five living members of the genus ''Panthera'', namely the tiger, lion, jaguar, leopard, and snow leopard.

Despite enormous differences in size, various cat species are quite similar ...

s, but was more robustly built. It had a reduced lumbar region

In tetrapod anatomy, lumbar is an adjective that means ''of or pertaining to the abdominal segment of the torso, between the diaphragm and the sacrum.''

The lumbar region is sometimes referred to as the lower spine, or as an area of the back i ...

, high scapula

The scapula (plural scapulae or scapulas), also known as the shoulder blade, is the bone that connects the humerus (upper arm bone) with the clavicle (collar bone). Like their connected bones, the scapulae are paired, with each scapula on eith ...

, short tail, and broad limbs with relatively short feet. ''Smilodon'' is most famous for its relatively long canine teeth, which are the longest found in the saber-toothed cats, at about long in the largest species, ''S.populator''. The canines were slender and had fine serrations on the front and back side. The skull was robustly proportioned and the muzzle was short and broad. The cheek bones (zygomata) were deep and widely arched, the sagittal crest

A sagittal crest is a ridge of bone running lengthwise along the midline of the top of the skull (at the sagittal suture) of many mammalian and reptilian skulls, among others. The presence of this ridge of bone indicates that there are exception ...

was prominent, and the frontal region was slightly convex. The mandible had a flange on each side of the front. The upper incisors were large, sharp, and slanted forwards. There was a diastema

A diastema (plural diastemata, from Greek διάστημα, space) is a space or gap between two teeth. Many species of mammals have diastemata as a normal feature, most commonly between the incisors and molars. More colloquially, the condition ...

(gap) between the incisors and molars of the mandible. The lower incisors were broad, recurved, and placed in a straight line across. The p3 premolar

The premolars, also called premolar teeth, or bicuspids, are transitional teeth located between the canine and molar teeth. In humans, there are two premolars per quadrant in the permanent set of teeth, making eight premolars total in the mouth ...

tooth of the mandible was present in most early specimens, but lost in later specimens; it was only present in 6% of the La Brea sample. There is some dispute over whether ''Smilodon'' was sexually dimorphic

Sexual dimorphism is the condition where the sexes of the same animal and/or plant species exhibit different morphological characteristics, particularly characteristics not directly involved in reproduction. The condition occurs in most ani ...

. Some studies of ''S. fatalis'' fossils have found little difference between the sexes. Conversely, a 2012 study found that, while fossils of ''S. fatalis'' show less variation in size among individuals than modern ''Panthera'', they do appear to show the same difference between the sexes in some traits.

''S. gracilis'' was the smallest species, estimated at in weight, about the size of a

''S. gracilis'' was the smallest species, estimated at in weight, about the size of a jaguar

The jaguar (''Panthera onca'') is a large cat species and the only living member of the genus ''Panthera'' native to the Americas. With a body length of up to and a weight of up to , it is the largest cat species in the Americas and the th ...

. It was similar to its predecessor ''Megantereon'' of the same size, but its dentition and skull were more advanced, approaching ''S. fatalis''. ''S. fatalis'' was intermediate in size between ''S. gracilis'' and ''S. populator''. It ranged from . and reached a shoulder height of and body length of . It was similar to a lion in dimensions, but was more robust and muscular, and therefore had a larger body mass. Its skull was also similar to that of ''Megantereon'', though more massive and with larger canines. ''S. populator'' was among the largest known felids, with a body mass range of , and one estimate suggesting up to . A particularly large ''S. populator'' skull from Uruguay measuring in length indicates this individual may have weighed as much as . It stood at a shoulder height of . Compared to ''S. fatalis'', ''S. populator'' was more robust and had a more elongated and narrow skull with a straighter upper profile, higher positioned nasal bone

The nasal bones are two small oblong bones, varying in size and form in different individuals; they are placed side by side at the middle and upper part of the face and by their junction, form the bridge of the upper one third of the nose.

Ea ...

s, a more vertical occiput, more massive metapodials and slightly longer forelimbs relative to hindlimbs. Large tracks from Argentina (for which the ichnotaxon name ''Smilodonichium'' has been proposed) have been attributed to ''S. populator'', and measure by . This is larger than tracks of the Bengal tiger

The Bengal tiger is a population of the '' Panthera tigris tigris'' subspecies. It ranks among the biggest wild cats alive today. It is considered to belong to the world's charismatic megafauna.

The tiger is estimated to have been present i ...

, to which the footprints have been compared.

Traditionally, saber-toothed cats have been artistically restored with external features similar to those of extant felids, by artists such as

Traditionally, saber-toothed cats have been artistically restored with external features similar to those of extant felids, by artists such as Charles R. Knight

Charles Robert Knight (October 21, 1874 – April 15, 1953) was an American wildlife and paleoartist best known for his detailed paintings of dinosaurs and other prehistoric animals. His works have been reproduced in many books and are currently ...

in collaboration with various paleontologists in the early 20th century. In 1969, paleontologist G. J. Miller instead proposed that ''Smilodon'' would have looked very different from a typical cat and similar to a bulldog

The Bulldog is a British breed of dog of mastiff type. It may also be known as the English Bulldog or British Bulldog. It is of medium size, a muscular, hefty dog with a wrinkled face and a distinctive pushed-in nose.Mauricio Antón and coauthors disputed this in 1998 and maintained that the facial features of ''Smilodon'' were overall not very different from those of other cats. Antón noted that modern animals like the

An apex predator, ''Smilodon'' primarily hunted large mammals.

An apex predator, ''Smilodon'' primarily hunted large mammals.

The

The  Debate continues as to how ''Smilodon'' killed its prey. Traditionally, the most popular theory is that the cat delivered a deep stabbing bite or open-jawed stabbing thrust to the throat, killing the prey very quickly. Another hypothesis suggests that ''Smilodon'' targeted the belly of its prey. This is disputed, as the curvature of their prey's belly would likely have prevented the cat from getting a good bite or stab. In regard to how ''Smilodon'' delivered its bite, the "canine shear-bite" hypothesis has been favored, where flexion of the neck and rotation of the skull assisted in biting the prey, but this may be mechanically impossible. However, evidence from comparisons with ''Homotherium'' suggest that ''Smilodon'' was fully capable of and utilized the canine shear-bite as its primary means of killing prey, based on the fact that it had a thick skull and relatively little trabecular bone, while ''Homotherium'' had both more trabecular bone and a more lion-like clamping bite as its primary means of attacking prey. The discovery, made by Figueirido and Lautenschlager ''et al.,'' published in 2018 suggests extremely different ecological adaptations in both machairodonts. The mandibular flanges may have helped resist bending forces when the mandible was pulled against the hide of a prey animal.

The protruding incisors were arranged in an arch, and were used to hold the prey still and stabilize it while the canine bite was delivered. The contact surface between the canine crown and the gum was enlarged, which helped stabilize the tooth and helped the cat sense when the tooth had penetrated to its maximum extent. Since saber-toothed cats generally had a relatively large infraorbital foramen (opening) in the skull, which housed nerves associated with the whiskers, it has been suggested the improved senses would have helped the cats' precision when biting outside their field of vision, and thereby prevent breakage of the canines. The blade-like

Debate continues as to how ''Smilodon'' killed its prey. Traditionally, the most popular theory is that the cat delivered a deep stabbing bite or open-jawed stabbing thrust to the throat, killing the prey very quickly. Another hypothesis suggests that ''Smilodon'' targeted the belly of its prey. This is disputed, as the curvature of their prey's belly would likely have prevented the cat from getting a good bite or stab. In regard to how ''Smilodon'' delivered its bite, the "canine shear-bite" hypothesis has been favored, where flexion of the neck and rotation of the skull assisted in biting the prey, but this may be mechanically impossible. However, evidence from comparisons with ''Homotherium'' suggest that ''Smilodon'' was fully capable of and utilized the canine shear-bite as its primary means of killing prey, based on the fact that it had a thick skull and relatively little trabecular bone, while ''Homotherium'' had both more trabecular bone and a more lion-like clamping bite as its primary means of attacking prey. The discovery, made by Figueirido and Lautenschlager ''et al.,'' published in 2018 suggests extremely different ecological adaptations in both machairodonts. The mandibular flanges may have helped resist bending forces when the mandible was pulled against the hide of a prey animal.

The protruding incisors were arranged in an arch, and were used to hold the prey still and stabilize it while the canine bite was delivered. The contact surface between the canine crown and the gum was enlarged, which helped stabilize the tooth and helped the cat sense when the tooth had penetrated to its maximum extent. Since saber-toothed cats generally had a relatively large infraorbital foramen (opening) in the skull, which housed nerves associated with the whiskers, it has been suggested the improved senses would have helped the cats' precision when biting outside their field of vision, and thereby prevent breakage of the canines. The blade-like

Scientists debate whether ''Smilodon'' was

Scientists debate whether ''Smilodon'' was  Another argument for sociality is based on the healed injuries in several ''Smilodon'' fossils, which would suggest that the animals needed others to provide them food. This argument has been questioned, as cats can recover quickly from even severe bone damage and an injured ''Smilodon'' could survive if it had access to water. However, a ''Smilodon'' suffering hip dysplasia at a young age that survived to adulthood suggests that it could not have survived to adulthood without aid from a social group, as this individual was unable to hunt or defend its territory due to the severity of its congenital issue. The brain of ''Smilodon'' was relatively small compared to other cat species. Some researchers have argued that ''Smilodon'' brain would have been too small for it to have been a social animal. An analysis of brain size in living big cats found no correlation between brain size and sociality. Another argument against ''Smilodon'' being social is that being an ambush hunter in closed habitat would likely have made group-living unnecessary, as in most modern cats. Yet it has also been proposed that being the largest predator in an environment comparable to the savanna of Africa, ''Smilodon'' may have had a social structure similar to modern lions, which possibly live in groups primarily to defend optimal territory from other lions (lions are the only social big cats today).

Whether ''Smilodon'' was sexually dimorphic has implications for its reproductive behavior. Based on their conclusions that ''Smilodon fatalis'' had no sexual dimorphism, Van Valkenburgh and Sacco suggested in 2002 that, if the cats were social, they would likely have lived in monogamous pairs (along with offspring) with no intense competition among males for females. Likewise, Meachen-Samuels and Binder concluded in 2010 that aggression between males was less pronounced in ''S. fatalis'' than in the American lion. Christiansen and Harris found in 2012 that, as ''S. fatalis'' did exhibit some sexual dimorphism, there would have been evolutionary selection for competition between males. Some bones show evidence of having been bitten by other ''Smilodon'', possibly the result of territorial battles, competition for breeding rights or over prey. Two ''S. populator'' skulls from Argentina show seemingly fatal, unhealed wounds which appear to have been caused by the canines of another ''Smilodon'' (though it cannot be ruled out they were caused by kicking prey). If caused by intraspecific fighting, it may also indicate that they had social behavior which could lead to death, as seen in some modern felines (as well as indicating that the canines could penetrate bone). It has been suggested that the exaggerated canines of saber-toothed cats evolved for

Another argument for sociality is based on the healed injuries in several ''Smilodon'' fossils, which would suggest that the animals needed others to provide them food. This argument has been questioned, as cats can recover quickly from even severe bone damage and an injured ''Smilodon'' could survive if it had access to water. However, a ''Smilodon'' suffering hip dysplasia at a young age that survived to adulthood suggests that it could not have survived to adulthood without aid from a social group, as this individual was unable to hunt or defend its territory due to the severity of its congenital issue. The brain of ''Smilodon'' was relatively small compared to other cat species. Some researchers have argued that ''Smilodon'' brain would have been too small for it to have been a social animal. An analysis of brain size in living big cats found no correlation between brain size and sociality. Another argument against ''Smilodon'' being social is that being an ambush hunter in closed habitat would likely have made group-living unnecessary, as in most modern cats. Yet it has also been proposed that being the largest predator in an environment comparable to the savanna of Africa, ''Smilodon'' may have had a social structure similar to modern lions, which possibly live in groups primarily to defend optimal territory from other lions (lions are the only social big cats today).

Whether ''Smilodon'' was sexually dimorphic has implications for its reproductive behavior. Based on their conclusions that ''Smilodon fatalis'' had no sexual dimorphism, Van Valkenburgh and Sacco suggested in 2002 that, if the cats were social, they would likely have lived in monogamous pairs (along with offspring) with no intense competition among males for females. Likewise, Meachen-Samuels and Binder concluded in 2010 that aggression between males was less pronounced in ''S. fatalis'' than in the American lion. Christiansen and Harris found in 2012 that, as ''S. fatalis'' did exhibit some sexual dimorphism, there would have been evolutionary selection for competition between males. Some bones show evidence of having been bitten by other ''Smilodon'', possibly the result of territorial battles, competition for breeding rights or over prey. Two ''S. populator'' skulls from Argentina show seemingly fatal, unhealed wounds which appear to have been caused by the canines of another ''Smilodon'' (though it cannot be ruled out they were caused by kicking prey). If caused by intraspecific fighting, it may also indicate that they had social behavior which could lead to death, as seen in some modern felines (as well as indicating that the canines could penetrate bone). It has been suggested that the exaggerated canines of saber-toothed cats evolved for

''Smilodon'' started developing its adult saber-teeth when the animal reached between 12 and 19 months of age, shortly after the completion of the eruption of the cat's baby teeth. Both baby and adult canines would be present side by side in the mouth for an approximately 11-month period, and the muscles used in making the powerful bite were developed at about one-and-a-half years old as well, eight months earlier than in a modern lion. After ''Smilodon'' reached 23 to 30 months of age, the infant teeth were shed while the adult canines grew at an average growth rate of per month during a 12-month period. They reached their full size at around 3 years of age, later than modern species of big cats. Juvenile and adolescent ''Smilodon'' specimens are extremely rare at Rancho La Brea, where the study was performed, indicating that they remained hidden or at denning sites during hunts, and depended on parental care while their canines were developing.

A 2017 study indicates that juveniles were born with a robust build similar to the adults. Comparison of the bones of juvenile ''S. fatalis'' specimens from La Brea with those of the contemporaneous American lion revealed that the two cats shared a similar growth curve. Felid forelimb development during

''Smilodon'' started developing its adult saber-teeth when the animal reached between 12 and 19 months of age, shortly after the completion of the eruption of the cat's baby teeth. Both baby and adult canines would be present side by side in the mouth for an approximately 11-month period, and the muscles used in making the powerful bite were developed at about one-and-a-half years old as well, eight months earlier than in a modern lion. After ''Smilodon'' reached 23 to 30 months of age, the infant teeth were shed while the adult canines grew at an average growth rate of per month during a 12-month period. They reached their full size at around 3 years of age, later than modern species of big cats. Juvenile and adolescent ''Smilodon'' specimens are extremely rare at Rancho La Brea, where the study was performed, indicating that they remained hidden or at denning sites during hunts, and depended on parental care while their canines were developing.

A 2017 study indicates that juveniles were born with a robust build similar to the adults. Comparison of the bones of juvenile ''S. fatalis'' specimens from La Brea with those of the contemporaneous American lion revealed that the two cats shared a similar growth curve. Felid forelimb development during

''Smilodon'' lived during the

''Smilodon'' lived during the

Along with most of the Pleistocene megafauna, ''Smilodon'' became extinct 10,000 years ago in the Quaternary extinction event. Its extinction has been linked to the decline and extinction of large herbivores, which were replaced by smaller and more agile ones like deer. Hence, ''Smilodon'' could have been too specialized at hunting large prey and may have been unable to adapt. A 2012 study of ''Smilodon'' tooth wear found no evidence that they were limited by food resources. Other explanations include climate change and competition with ''

Along with most of the Pleistocene megafauna, ''Smilodon'' became extinct 10,000 years ago in the Quaternary extinction event. Its extinction has been linked to the decline and extinction of large herbivores, which were replaced by smaller and more agile ones like deer. Hence, ''Smilodon'' could have been too specialized at hunting large prey and may have been unable to adapt. A 2012 study of ''Smilodon'' tooth wear found no evidence that they were limited by food resources. Other explanations include climate change and competition with ''

hippopotamus

The hippopotamus ( ; : hippopotamuses or hippopotami; ''Hippopotamus amphibius''), also called the hippo, common hippopotamus, or river hippopotamus, is a large semiaquatic mammal native to sub-Saharan Africa. It is one of only two exta ...

are able to open their mouths extremely wide without tearing tissue due to a folded orbicularis oris muscle

In human anatomy, the orbicularis oris muscle is a complex of muscles in the lips that encircles the mouth.

It is a sphincter, or circular muscle, but it is actually composed of four independent quadrants that interlace and give only an appearance ...

, and such a muscle arrangement exists in modern large felids. Antón stated that extant phylogenetic bracketing (where the features of the closest extant relatives of a fossil taxon are used as reference) is the most reliable way of restoring the life-appearance of prehistoric animals, and the cat-like ''Smilodon'' restorations by Knight are therefore still accurate. A 2022 study by Antón and colleagues concluded that the upper canines of ''Smilodon'' would have been visible when the mouth was closed, while those of ''Homotherium'' would have not, after examining fossils and extant big cats.

''Smilodon'' and other saber-toothed cats have been reconstructed with both plain-colored coats and with spotted patterns (which appears to be the ancestral condition for feliforms), both of which are considered possible. Studies of modern cat species have found that species that live in the open tend to have uniform coats while those that live in more vegetated habitats have more markings, with some exceptions. Some coat features, such as the manes of male lions or the stripes of the tiger, are too unusual to predict from fossils.

Paleobiology

Diet

An apex predator, ''Smilodon'' primarily hunted large mammals.

An apex predator, ''Smilodon'' primarily hunted large mammals. Isotope

Isotopes are two or more types of atoms that have the same atomic number (number of protons in their nuclei) and position in the periodic table (and hence belong to the same chemical element), and that differ in nucleon numbers ( mass num ...

s preserved in the bones of ''S. fatalis'' in the La Brea Tar Pits reveal that ruminants like bison ('' Bison antiquus'', which was much larger than the modern American bison

The American bison (''Bison bison'') is a species of bison native to North America. Sometimes colloquially referred to as American buffalo or simply buffalo (a different clade of bovine), it is one of two extant species of bison, alongside the ...

) and camels ('' Camelops'') were most commonly taken by the cats there. In addition, isotopes preserved in the tooth enamel

Tooth enamel is one of the four major tissues that make up the tooth in humans and many other animals, including some species of fish. It makes up the normally visible part of the tooth, covering the crown. The other major tissues are dentin, ...

of ''S. gracilis'' specimens from Florida show that this species fed on the peccary '' Platygonus'' and the llama

The llama (; ) (''Lama glama'') is a domesticated South American camelid, widely used as a meat and pack animal by Andean cultures since the Pre-Columbian era.

Llamas are social animals and live with others as a herd. Their wool is soft ...

-like ''Hemiauchenia

''Hemiauchenia'' is a genus of laminoid camelids that evolved in North America in the Miocene period about 10 million years ago. This genus diversified and moved to South America in the Early Pleistocene, as part of the Great American Biotic I ...

''. Isotopic studies of dire wolf (''Aenocyon dirus'') and American lion

''Panthera atrox'', better known as the American lion, also called the North American lion, or American cave lion, is an extinct pantherine cat that lived in North America during the Pleistocene epoch and the early Holocene epoch, about 340, ...

(''Panthera atrox'') bones show an overlap with ''S. fatalis'' in prey, which suggests that they were competitors. More detailed isotope analysis however, indicates that ''Smilodon fatalis'' preferred forest-dwelling prey such as tapirs, deer and forest-dwelling bison as opposed to the dire wolves' preferences for prey inhabiting open areas such as grassland. The availability of prey in the Rancho La Brea area was likely comparable to modern East Africa

East Africa, Eastern Africa, or East of Africa, is the eastern subregion of the African continent. In the United Nations Statistics Division scheme of geographic regions, 10-11-(16*) territories make up Eastern Africa:

Due to the historica ...

.

As ''Smilodon'' migrated to South America, its diet changed; bison were absent, the horses

The horse (''Equus ferus caballus'') is a domesticated, one-toed, hoofed mammal. It belongs to the taxonomic family Equidae and is one of two extant subspecies of ''Equus ferus''. The horse has evolved over the past 45 to 55 million ...

and proboscidea

The Proboscidea (; , ) are a taxonomic order of afrotherian mammals containing one living family ( Elephantidae) and several extinct families. First described by J. Illiger in 1811, it encompasses the elephants and their close relatives. Fr ...

ns were different, and native ungulates such as toxodonts

Toxodontia. Retrieved April 2013. is a suborder of the meridiungulate order Notoungulata. Most of the members of the five included families, including the largest notoungulates, share several dental, auditory and tarsal specializations. The gr ...

and litopterns were completely unfamiliar, yet ''S. populator'' thrived as well there as its relatives in North America. Isotopic analysis for ''Smilodon populator'' suggests that its main prey species included '' Toxodon platensis'', '' Pachyarmatherium'', '' Holmesina'', species of the genus '' Panochthus'', ''Palaeolama

''Palaeolama'' () is an extinct genus of laminoid camelid that existed from the Late Pliocene to the Early Holocene (). Their range extended from North America to the intertropical region of South America.

Description

''Palaeolama'' were rel ...

'', ''Catonyx

''Catonyx'' is an extinct genus of ground sloth of the family Scelidotheriidae, endemic to South America during the Pliocene and Pleistocene epochs. It lived from 2.5 Ma to about 10,000 years ago, existing for approximately . The most recent dat ...

'', '' Equus neogeus'', and the crocodilian '' Caiman latirostris''. This analysis of its diet also indicates that ''S. populator'' hunted both in open and forested habitats. The differences between the North and South American species may be due to the difference in prey between the two continents. ''Smilodon'' may have avoided eating bone and would have left enough food for scavengers. However, coprolite

A coprolite (also known as a coprolith) is fossilized feces. Coprolites are classified as trace fossils as opposed to body fossils, as they give evidence for the animal's behaviour (in this case, diet) rather than morphology. The name is ...

s assigned to ''S. populator'' recovered from Argentina preserve '' Mylodon'' osteoderms and a ''Lama

Lama (; "chief") is a title for a teacher of the Dharma in Tibetan Buddhism. The name is similar to the Sanskrit term ''guru'', meaning "heavy one", endowed with qualities the student will eventually embody. The Tibetan word "lama" means "hig ...

'' scaphoid bone. In addition to this unambiguous evidence of bone consumption, the coprolites suggest that ''Smilodon'' had a more generalist diet than previously thought. Examinations of dental microwear from La Brea further suggests that ''Smilodon'' consumed both flesh and bone. ''Smilodon'' itself may have scavenged dire wolf kills. It has been suggested that ''Smilodon'' was a pure scavenger that used its canines for display to assert dominance over carcasses, but this theory is not supported today as no modern terrestrial mammals are pure scavengers.

Predatory behavior

The

The brain

A brain is an organ (biology), organ that serves as the center of the nervous system in all vertebrate and most invertebrate animals. It is located in the head, usually close to the sensory organs for senses such as Visual perception, vision. I ...

of ''Smilodon'' had sulcal

Sulcalization (from la, sulcus 'groove'), in phonetics, is the pronunciation of a sound, typically a sibilant consonant, such as English language, English and , with a deep ''groove'' running along the back of the tongue that focuses the airstre ...

patterns similar to modern cats, which suggests an increased complexity of the regions that control the sense of hearing, sight, and coordination of the limbs. Felid saber-tooths in general had relatively small eyes that were not as forward-facing as those of modern cats, which have good binocular vision

In biology, binocular vision is a type of vision in which an animal has two eyes capable of facing the same direction to perceive a single three-dimensional image of its surroundings. Binocular vision does not typically refer to vision where an ...

to help them move in trees. ''Smilodon'' was likely an ambush predator

Ambush predators or sit-and-wait predators are carnivorous animals that capture or trap prey via stealth, luring or by (typically instinctive) strategies utilizing an element of surprise. Unlike pursuit predators, who chase to capture prey ...

that concealed itself in dense vegetation, as its limb proportions were similar to modern forest-dwelling cats, and its short tail would not have helped it balance while running. Unlike its ancestor ''Megantereon'', which was at least partially scansorial

Arboreal locomotion is the locomotion of animals in trees. In habitats in which trees are present, animals have evolved to move in them. Some animals may scale trees only occasionally, but others are exclusively arboreal. The habitats pose nu ...

and therefore able to climb trees, ''Smilodon'' was probably completely terrestrial due to its greater weight and lack of climbing adaptations. Tracks from Argentina named ''Felipeda miramarensis'' in 2019 may have been produced by ''Smilodon''. If correctly identified, the tracks indicate that the animal had fully retractible claws, plantigrade

151px, Portion of a human skeleton, showing plantigrade habit

In terrestrial animals, plantigrade locomotion means walking with the toes and metatarsals flat on the ground. It is one of three forms of locomotion adopted by terrestrial mammals. ...

feet, lacked strong supination

Motion, the process of movement, is described using specific anatomical terms. Motion includes movement of organs, joints, limbs, and specific sections of the body. The terminology used describes this motion according to its direction relati ...

capabilities in its paws, notably robust forelimbs compared to the hindlimbs, and was probably an ambush predator.

The heel bone of ''Smilodon'' was fairly long, which suggests it was a good jumper. Its well-developed flexor and extensor muscles in its forearm

The forearm is the region of the upper limb between the elbow and the wrist. The term forearm is used in anatomy to distinguish it from the arm, a word which is most often used to describe the entire appendage of the upper limb, but which in ...

s probably enabled it to pull down, and securely hold down, large prey. Analysis of the cross-sections of ''S. fatalis'' humeri indicated that they were strengthened by cortical thickening to such an extent that they would have been able to sustain greater loading than those of extant big cats, or of the extinct American lion. The thickening of ''S. fatalis'' femur

The femur (; ), or thigh bone, is the proximal bone of the hindlimb in tetrapod vertebrates. The head of the femur articulates with the acetabulum in the pelvic bone forming the hip joint, while the distal part of the femur articulates ...

s was within the range of extant felids. Its canines were fragile and could not have bitten into bone; due to the risk of breaking, these cats had to subdue and restrain their prey with their powerful forelimbs before they could use their canine teeth, and likely used quick slashing or stabbing bites rather than the slow, suffocating bites typically used by modern cats. On rare occasions, as evidenced by fossils, ''Smilodon'' was willing to risk biting into bone with its canines. This may have been focused more towards competition such as other ''Smilodon'' or potential threats such as other carnivores than on prey.

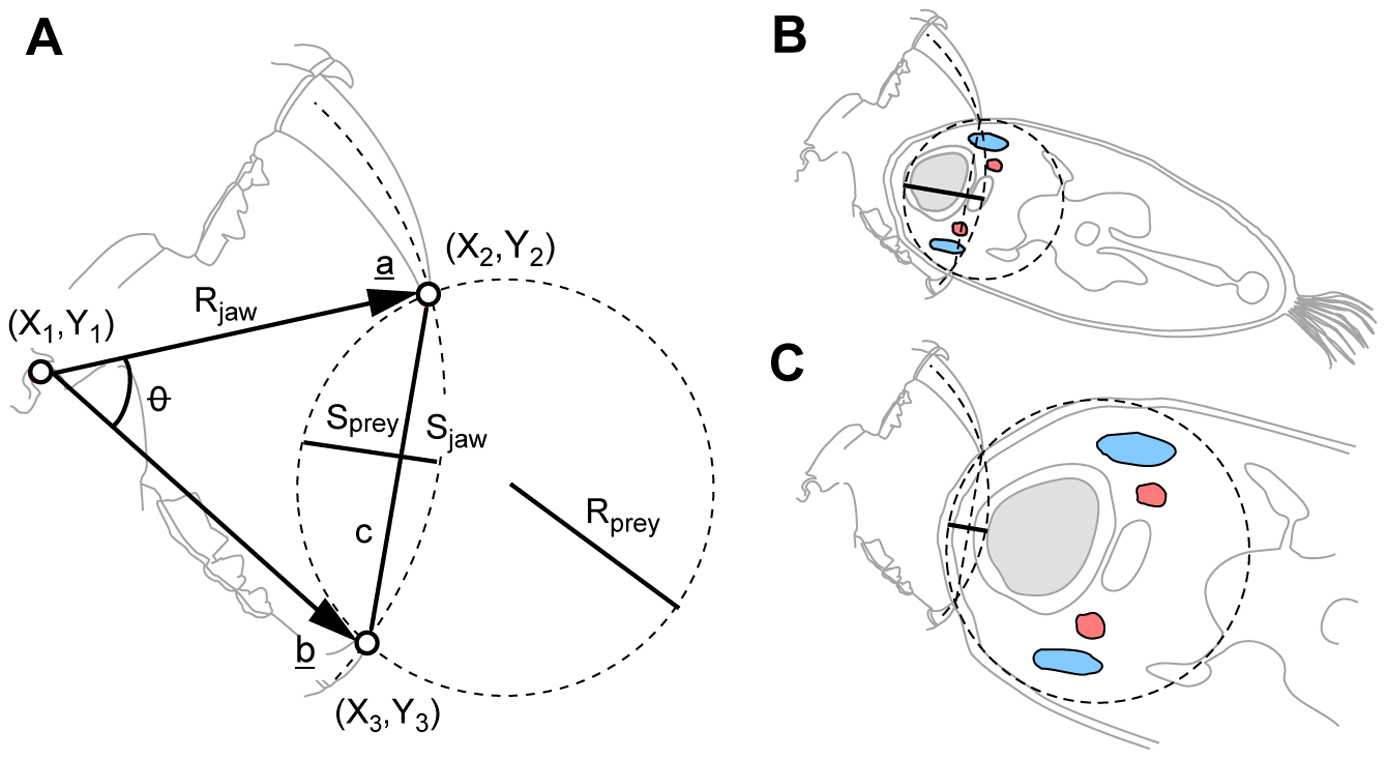

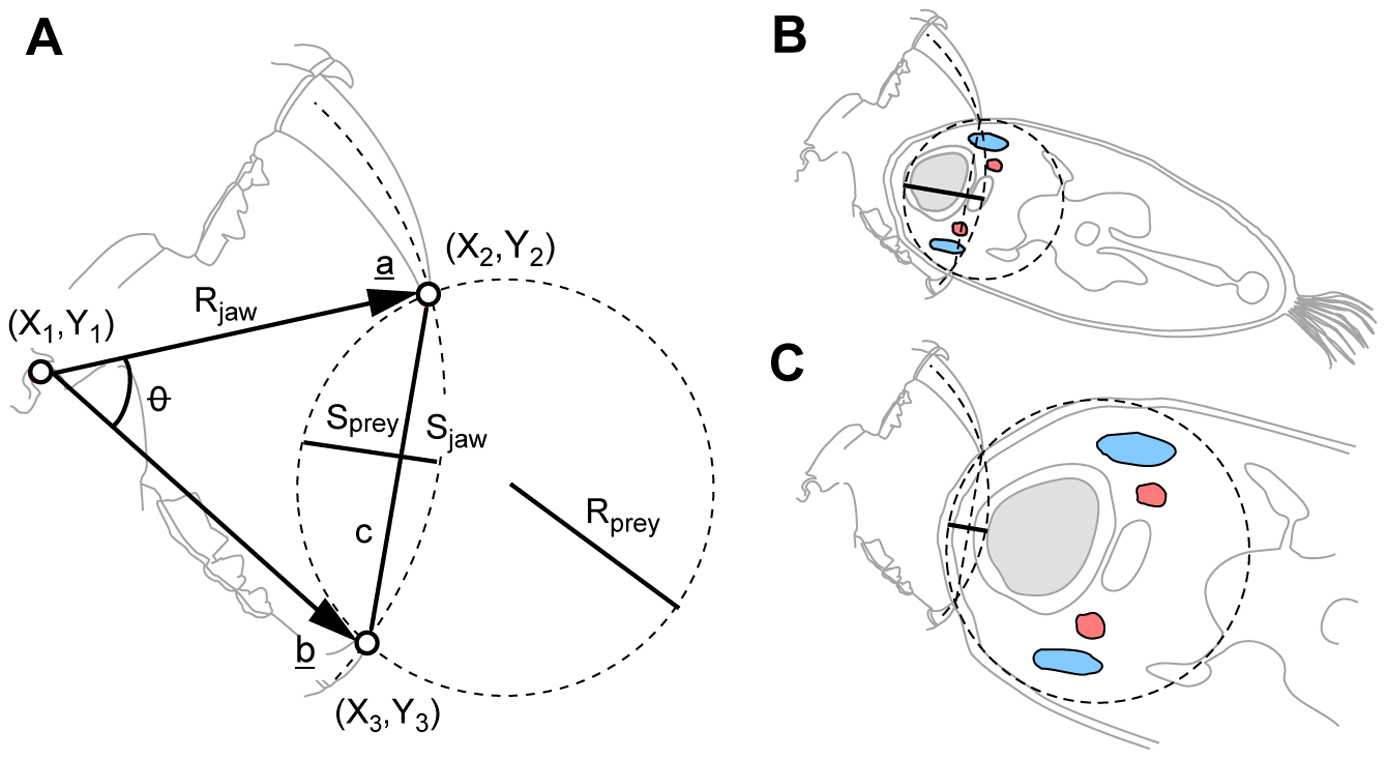

Debate continues as to how ''Smilodon'' killed its prey. Traditionally, the most popular theory is that the cat delivered a deep stabbing bite or open-jawed stabbing thrust to the throat, killing the prey very quickly. Another hypothesis suggests that ''Smilodon'' targeted the belly of its prey. This is disputed, as the curvature of their prey's belly would likely have prevented the cat from getting a good bite or stab. In regard to how ''Smilodon'' delivered its bite, the "canine shear-bite" hypothesis has been favored, where flexion of the neck and rotation of the skull assisted in biting the prey, but this may be mechanically impossible. However, evidence from comparisons with ''Homotherium'' suggest that ''Smilodon'' was fully capable of and utilized the canine shear-bite as its primary means of killing prey, based on the fact that it had a thick skull and relatively little trabecular bone, while ''Homotherium'' had both more trabecular bone and a more lion-like clamping bite as its primary means of attacking prey. The discovery, made by Figueirido and Lautenschlager ''et al.,'' published in 2018 suggests extremely different ecological adaptations in both machairodonts. The mandibular flanges may have helped resist bending forces when the mandible was pulled against the hide of a prey animal.

The protruding incisors were arranged in an arch, and were used to hold the prey still and stabilize it while the canine bite was delivered. The contact surface between the canine crown and the gum was enlarged, which helped stabilize the tooth and helped the cat sense when the tooth had penetrated to its maximum extent. Since saber-toothed cats generally had a relatively large infraorbital foramen (opening) in the skull, which housed nerves associated with the whiskers, it has been suggested the improved senses would have helped the cats' precision when biting outside their field of vision, and thereby prevent breakage of the canines. The blade-like

Debate continues as to how ''Smilodon'' killed its prey. Traditionally, the most popular theory is that the cat delivered a deep stabbing bite or open-jawed stabbing thrust to the throat, killing the prey very quickly. Another hypothesis suggests that ''Smilodon'' targeted the belly of its prey. This is disputed, as the curvature of their prey's belly would likely have prevented the cat from getting a good bite or stab. In regard to how ''Smilodon'' delivered its bite, the "canine shear-bite" hypothesis has been favored, where flexion of the neck and rotation of the skull assisted in biting the prey, but this may be mechanically impossible. However, evidence from comparisons with ''Homotherium'' suggest that ''Smilodon'' was fully capable of and utilized the canine shear-bite as its primary means of killing prey, based on the fact that it had a thick skull and relatively little trabecular bone, while ''Homotherium'' had both more trabecular bone and a more lion-like clamping bite as its primary means of attacking prey. The discovery, made by Figueirido and Lautenschlager ''et al.,'' published in 2018 suggests extremely different ecological adaptations in both machairodonts. The mandibular flanges may have helped resist bending forces when the mandible was pulled against the hide of a prey animal.

The protruding incisors were arranged in an arch, and were used to hold the prey still and stabilize it while the canine bite was delivered. The contact surface between the canine crown and the gum was enlarged, which helped stabilize the tooth and helped the cat sense when the tooth had penetrated to its maximum extent. Since saber-toothed cats generally had a relatively large infraorbital foramen (opening) in the skull, which housed nerves associated with the whiskers, it has been suggested the improved senses would have helped the cats' precision when biting outside their field of vision, and thereby prevent breakage of the canines. The blade-like carnassial

Carnassials are paired upper and lower teeth modified in such a way as to allow enlarged and often self-sharpening edges to pass by each other in a shearing manner. This adaptation is found in carnivorans, where the carnassials are the modified f ...

teeth were used to cut skin to access the meat, and the reduced molars suggest that they were less adapted for crushing bones than modern cats. As the food of modern cats enters the mouth through the side while cutting with the carnassials, not the front incisors between the canines, the animals do not need to gape widely, so the canines of ''Smilodon'' would likewise not have been a hindrance when feeding. A study published in 2022 of how machairodonts fed revealed that wear patterns on the teeth of ''S. fatalis'' also suggest that it was capable of eating bone to a similar extent as lions. This and comparisons with bite marks left by the contemporary machairodont ''Xenosmilus

''Xenosmilus hodsonae'' (from Greek, , ''xenos'', "strange" + , ''smilē'', "chisel" ) is an extinct species of the Machairodontinae, or saber-toothed cats.

Description

The species name ''hodsonae'' originates from Debra Hodson, the wife of a ...

'' suggest that ''Smilodon'' and its relatives could efficiently de-flesh a carcass of meat when feeding without being hindered by their long canines.

Despite being more powerfully built than other large cats, ''Smilodon'' had a weaker bite. Modern big cats have more pronounced zygomatic arch

In anatomy, the zygomatic arch, or cheek bone, is a part of the skull formed by the zygomatic process of the temporal bone (a bone extending forward from the side of the skull, over the opening of the ear) and the temporal process of the zygo ...

es, while these were smaller in ''Smilodon'', which restricted the thickness and therefore power of the temporalis muscles and thus reduced ''Smilodon''s bite force. Analysis of its narrow jaws indicates that it could produce a bite only a third as strong as that of a lion (the bite force quotient measured for the lion is 112). There seems to be a general rule that the saber-toothed cats with the largest canines had proportionally weaker bites. Analyses of canine bending strength

Flexural strength, also known as modulus of rupture, or bend strength, or transverse rupture strength is a material property, defined as the stress in a material just before it yields in a flexure test. The transverse bending test is most frequ ...

(the ability of the canine teeth to resist bending forces without breaking) and bite forces indicate that the saber-toothed cats' teeth were stronger relative to the bite force than those of modern big cats. In addition, ''Smilodon'' gape could have reached over 110 degrees, while that of the modern lion reaches 65 degrees. This made the gape wide enough to allow ''Smilodon'' to grasp large prey despite the long canines. A 2018 study compared the killing behavior of ''Smilodon fatalis'' and ''Homotherium serum'', and found that the former had a strong skull with little trabecular bone for a stabbing canine-shear bite, whereas the latter had more trabecular bone and used a clamp and hold style more similar to lions. The two would therefore have held distinct ecological niches.

Natural traps

Many ''Smilodon'' specimens have been excavated from asphalt seeps that acted as natural carnivore traps. Animals were accidentally trapped in the seeps and became bait for predators that came to scavenge, but these were then trapped themselves. The best-known of such traps are at La Brea in Los Angeles, which have produced over 166,000 ''Smilodon fatalis'' specimens that form the largest collection in the world. The sediments of the pits there were accumulated 40,000 to 10,000 years ago, in theLate Pleistocene

The Late Pleistocene is an unofficial age in the international geologic timescale in chronostratigraphy, also known as Upper Pleistocene from a stratigraphic perspective. It is intended to be the fourth division of the Pleistocene Epoch withi ...

. Though the trapped animals were buried quickly, predators often managed to remove limb bones from them, but they were themselves often trapped and then scavenged by other predators; 90% of the excavated bones belonged to predators.

The Talara Tar Seeps in Peru represent a similar scenario, and have also produced fossils of ''Smilodon''. Unlike in La Brea, many of the bones were broken or show signs of weathering. This may have been because the layers were shallower, so the thrashing of trapped animals damaged the bones of previously trapped animals. Many of the carnivores at Talara were juveniles, possibly indicating that inexperienced and less fit animals had a greater chance of being trapped. Though Lund thought accumulations of ''Smilodon'' and herbivore fossils in the Lagoa Santa Caves were due to the cats using the caves as dens, these are probably the result of animals dying on the surface, and water currents subsequently dragging their bones to the floor of the cave, but some individuals may also have died after becoming lost in the caves.

Social life

Scientists debate whether ''Smilodon'' was

Scientists debate whether ''Smilodon'' was social

Social organisms, including human(s), live collectively in interacting populations. This interaction is considered social whether they are aware of it or not, and whether the exchange is voluntary or not.

Etymology

The word "social" derives from ...

. One study of African predators found that social predators like lion

The lion (''Panthera leo'') is a large cat of the genus '' Panthera'' native to Africa and India. It has a muscular, broad-chested body; short, rounded head; round ears; and a hairy tuft at the end of its tail. It is sexually dimorphic; adu ...

s and spotted hyena

The spotted hyena (''Crocuta crocuta''), also known as the laughing hyena, is a hyena species, currently classed as the sole extant member of the genus ''Crocuta'', native to sub-Saharan Africa. It is listed as being of least concern by the IUC ...

s respond more to the distress call

A distress signal, also known as a distress call, is an internationally recognized means for obtaining help. Distress signals are communicated by transmitting radio signals, displaying a visually observable item or illumination, or making a soun ...

s of prey than solitary species. Since ''S. fatalis'' fossils are common at the La Brea Tar Pits, and were likely attracted by the distress calls of stuck prey, this could mean that this species was social as well. One critical study claims that the study neglects other factors, such as body mass (heavier animals are more likely to get stuck than lighter ones), intelligence (some social animals, like the American lion, may have avoided the tar because they were better able to recognize the hazard), lack of visual and olfactory

The sense of smell, or olfaction, is the special sense through which smells (or odors) are perceived. The sense of smell has many functions, including detecting desirable foods, hazards, and pheromones, and plays a role in taste.

In humans, ...

lures, the type of audio lure, and the length of the distress calls (the actual distress calls of the trapped prey animals would have lasted longer than the calls used in the study). The author of that study ponders what predators would have responded if the recordings were played in India, where the otherwise solitary tigers are known to aggregate around a single carcass. The authors of the original study responded that though effects of the calls in the tar pits and the playback experiments would not be identical, this would not be enough to overturn their conclusions. In addition, they stated that weight and intelligence would not likely affect the results as lighter carnivores are far more numerous than heavy herbivores and the social (and seemingly intelligent) dire wolf is also found in the pits.

Another argument for sociality is based on the healed injuries in several ''Smilodon'' fossils, which would suggest that the animals needed others to provide them food. This argument has been questioned, as cats can recover quickly from even severe bone damage and an injured ''Smilodon'' could survive if it had access to water. However, a ''Smilodon'' suffering hip dysplasia at a young age that survived to adulthood suggests that it could not have survived to adulthood without aid from a social group, as this individual was unable to hunt or defend its territory due to the severity of its congenital issue. The brain of ''Smilodon'' was relatively small compared to other cat species. Some researchers have argued that ''Smilodon'' brain would have been too small for it to have been a social animal. An analysis of brain size in living big cats found no correlation between brain size and sociality. Another argument against ''Smilodon'' being social is that being an ambush hunter in closed habitat would likely have made group-living unnecessary, as in most modern cats. Yet it has also been proposed that being the largest predator in an environment comparable to the savanna of Africa, ''Smilodon'' may have had a social structure similar to modern lions, which possibly live in groups primarily to defend optimal territory from other lions (lions are the only social big cats today).

Whether ''Smilodon'' was sexually dimorphic has implications for its reproductive behavior. Based on their conclusions that ''Smilodon fatalis'' had no sexual dimorphism, Van Valkenburgh and Sacco suggested in 2002 that, if the cats were social, they would likely have lived in monogamous pairs (along with offspring) with no intense competition among males for females. Likewise, Meachen-Samuels and Binder concluded in 2010 that aggression between males was less pronounced in ''S. fatalis'' than in the American lion. Christiansen and Harris found in 2012 that, as ''S. fatalis'' did exhibit some sexual dimorphism, there would have been evolutionary selection for competition between males. Some bones show evidence of having been bitten by other ''Smilodon'', possibly the result of territorial battles, competition for breeding rights or over prey. Two ''S. populator'' skulls from Argentina show seemingly fatal, unhealed wounds which appear to have been caused by the canines of another ''Smilodon'' (though it cannot be ruled out they were caused by kicking prey). If caused by intraspecific fighting, it may also indicate that they had social behavior which could lead to death, as seen in some modern felines (as well as indicating that the canines could penetrate bone). It has been suggested that the exaggerated canines of saber-toothed cats evolved for

Another argument for sociality is based on the healed injuries in several ''Smilodon'' fossils, which would suggest that the animals needed others to provide them food. This argument has been questioned, as cats can recover quickly from even severe bone damage and an injured ''Smilodon'' could survive if it had access to water. However, a ''Smilodon'' suffering hip dysplasia at a young age that survived to adulthood suggests that it could not have survived to adulthood without aid from a social group, as this individual was unable to hunt or defend its territory due to the severity of its congenital issue. The brain of ''Smilodon'' was relatively small compared to other cat species. Some researchers have argued that ''Smilodon'' brain would have been too small for it to have been a social animal. An analysis of brain size in living big cats found no correlation between brain size and sociality. Another argument against ''Smilodon'' being social is that being an ambush hunter in closed habitat would likely have made group-living unnecessary, as in most modern cats. Yet it has also been proposed that being the largest predator in an environment comparable to the savanna of Africa, ''Smilodon'' may have had a social structure similar to modern lions, which possibly live in groups primarily to defend optimal territory from other lions (lions are the only social big cats today).

Whether ''Smilodon'' was sexually dimorphic has implications for its reproductive behavior. Based on their conclusions that ''Smilodon fatalis'' had no sexual dimorphism, Van Valkenburgh and Sacco suggested in 2002 that, if the cats were social, they would likely have lived in monogamous pairs (along with offspring) with no intense competition among males for females. Likewise, Meachen-Samuels and Binder concluded in 2010 that aggression between males was less pronounced in ''S. fatalis'' than in the American lion. Christiansen and Harris found in 2012 that, as ''S. fatalis'' did exhibit some sexual dimorphism, there would have been evolutionary selection for competition between males. Some bones show evidence of having been bitten by other ''Smilodon'', possibly the result of territorial battles, competition for breeding rights or over prey. Two ''S. populator'' skulls from Argentina show seemingly fatal, unhealed wounds which appear to have been caused by the canines of another ''Smilodon'' (though it cannot be ruled out they were caused by kicking prey). If caused by intraspecific fighting, it may also indicate that they had social behavior which could lead to death, as seen in some modern felines (as well as indicating that the canines could penetrate bone). It has been suggested that the exaggerated canines of saber-toothed cats evolved for sexual display

A courtship display is a set of display behaviors in which an animal, usually a male, attempts to attract a mate; the mate exercises choice, so sexual selection acts on the display. These behaviors often include ritualized movement ("dances"), ...

and competition, but a statistical study of the correlation between canine and body size in ''S. populator'' found no difference in scaling between body and canine size concluded it was more likely they evolved solely for a predatory function.

A set of three associated skeletons of ''S. fatalis'' found in Ecuador and described in 2021 by Reynolds, Seymour, and Evans suggests that there was prolonged parental care in ''Smilodon''. The two subadult individuals uncovered share a unique inherited trait in their dentaries, suggesting they were siblings; a rare instance of familial relationships being found in the fossil record. The subadult specimens are also hypothesized to have been male and female, respectively, while the adult skeletal remains found at the site are believed to have belonged to their mother. The subadults were estimated to have been around two years of age at the time of their deaths, but were still growing. The structure of the hyoid bone

The hyoid bone (lingual bone or tongue-bone) () is a horseshoe-shaped bone situated in the anterior midline of the neck between the chin and the thyroid cartilage. At rest, it lies between the base of the mandible and the third cervical verteb ...

s suggest that ''Smilodon'' could roar like modern big cats, which may have implications for their social life.

Development