Sheridan Downey on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sheridan Downey (March 11, 1884 – October 25, 1961) was an American lawyer and a Democratic

Before long, more than 2,000 grassroots EPIC clubs sprouted throughout the state, and the most popular EPIC anthem, "Campaign Chorus for Downey and Sinclair," was made into a

Before long, more than 2,000 grassroots EPIC clubs sprouted throughout the state, and the most popular EPIC anthem, "Campaign Chorus for Downey and Sinclair," was made into a

Portraits of American Women: From Settlement to the Present

', Oxford University, 1998, pg. 554.

After his narrow reelection to the Senate in 1944, defeating Republican Lieutenant Governor Frederick F. Houser by 52 percent to 48 percent, Downey began a push for the California Central Valley project, which had been initiated during the 1930s as part of the

After his narrow reelection to the Senate in 1944, defeating Republican Lieutenant Governor Frederick F. Houser by 52 percent to 48 percent, Downey began a push for the California Central Valley project, which had been initiated during the 1930s as part of the

Sheridan Downey

at ''The Political Graveyard''

Guide to the Sheridan Downey Papers

at

U.S. Senator

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and powe ...

from California

California is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, located along the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the List of states and territori ...

from 1939 to 1950.

Early life

He was born in Laramie, the seat of Albany County in westernWyoming

Wyoming () is a U.S. state, state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is bordered by Montana to the north and northwest, South Dakota and Nebraska to the east, Idaho to the west, Utah to the south ...

, the son of the former Evangeline Victoria Owen and Stephen Wheeler Downey

Stephen Wheeler Downey (July 25, 1839 – August 3, 1902) was a lawyer and politician in Wyoming. A Union Army veteran of the American Civil War, he was an early white settler of Wyoming, and served as its treasurer, auditor, and delegate to ...

. He was educated in public schools of Laramie, and attended the University of Wyoming

The University of Wyoming (UW) is a public land-grant research university in Laramie, Wyoming. It was founded in March 1886, four years before the territory was admitted as the 44th state, and opened in September 1887. The University of Wyoming ...

. Downey attended the University of Michigan Law School

The University of Michigan Law School (Michigan Law) is the law school of the University of Michigan, a Public university, public research university in Ann Arbor, Michigan. Founded in 1859, the school offers Master of Laws (LLM), Master of C ...

, and attained admission to the bar in 1907. In 1914, the school awarded Downey his LL.B.

Bachelor of Laws ( la, Legum Baccalaureus; LL.B.) is an undergraduate law degree in the United Kingdom and most common law jurisdictions. Bachelor of Laws is also the name of the law degree awarded by universities in the People's Republic of Chi ...

degree as of the graduating class of 1907. He practiced law in Laramie, and in 1908 he was elected district attorney

In the United States, a district attorney (DA), county attorney, state's attorney, prosecuting attorney, commonwealth's attorney, or state attorney is the chief prosecutor and/or chief law enforcement officer representing a U.S. state in a l ...

of Albany County as a Republican. In 1910 he married Helen Symons; they had five children. In 1912, Downey split Wyoming's Republican vote by heading the state's "Bull Moose" revolt in support of Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

, thus leading to a Democratic victory statewide.

Politics

In 1913, Downey moved toSacramento, California

)

, image_map = Sacramento County California Incorporated and Unincorporated areas Sacramento Highlighted.svg

, mapsize = 250x200px

, map_caption = Location within Sacramento C ...

, and continued to practice law with his brother, Stephen Wheeler Downey, Jr. During his first few years in California, he devoted most of his time and energy to his law practice and various real estate interests. In 1924 he supported Robert La Follette, Sr.

Robert Marion "Fighting Bob" La Follette Sr. (June 14, 1855June 18, 1925), was an American lawyer and politician. He represented Wisconsin in both chambers of Congress and served as the 20th Governor of Wisconsin. A Republican for most of his l ...

's Progressive party campaign for the presidency, and in 1932 he became a Democrat and campaigned for the election of Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

.

In October 1933, Downey announced that he was running for governor of California. After a series of meetings with the writer Upton Sinclair

Upton Beall Sinclair Jr. (September 20, 1878 – November 25, 1968) was an American writer, muckraker, political activist and the 1934 Democratic Party nominee for governor of California who wrote nearly 100 books and other works in seve ...

, who also had designs on the governorship, Downey agreed to run for Lieutenant Governor of California

The lieutenant governor of California is the second highest executive officer of the government of the U.S. state of California. The lieutenant governor is elected to serve a four-year term and can serve a maximum of two terms. In addition to l ...

while Sinclair ran for governor. Their political platform was the End Poverty in California

End Poverty in California (EPIC) was a political campaign started in 1934 by socialist writer Upton Sinclair (best known as author of ''The Jungle''). The movement formed the basis for Sinclair's campaign for Governor of California in 1934. The p ...

(EPIC) plan. Opponents called the ticket "Uppie and Downey". EPIC began as a mass movement, calling for an economic revolution to lift California out of the depression. The EPIC platform called for state support for the creation of jobs, a massive program of public works, and an extensive system of state-sponsored pensions and radical changes in the tax structure.

Before long, more than 2,000 grassroots EPIC clubs sprouted throughout the state, and the most popular EPIC anthem, "Campaign Chorus for Downey and Sinclair," was made into a

Before long, more than 2,000 grassroots EPIC clubs sprouted throughout the state, and the most popular EPIC anthem, "Campaign Chorus for Downey and Sinclair," was made into a phonograph record

A phonograph record (also known as a gramophone record, especially in British English), or simply a record, is an analog sound storage medium in the form of a flat disc with an inscribed, modulated spiral groove. The groove usually starts nea ...

by Titan Records for mass distribution. It featured the speaking voice of Downey, announcer Jerry Wilford, and the singing of three men calling themselves the "Epic Trio." While EPIC was defeated by Republican Frank Merriam

Frank Finley Merriam (December 22, 1865 – April 25, 1955) was an American Republican politician who served as the 28th governor of California from June 2, 1934 until January 2, 1939. Assuming the governorship at the height of the Great Depress ...

in November 1934. Downey, who had been subjected to less vitriol than Sinclair during the campaign, remained a viable political force in the state. Downey actually garnered 123,000 votes more than his running mate. Downey gained a statewide reputation as a champion of progressive politics.

After Sinclair's defeat, Downey became an attorney involved with Dr. Francis Townsend

Francis Everett Townsend (; January 13, 1867 – September 1, 1960) was an American physician and political activist in California, In 1933 he devised an old-age pension scheme to help alleviate the Great Depression. Known as the "Townsend Plan ...

, the main advocate of the Townsend Plan for government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive, and judiciary. Government is a ...

old-age pension

A pension (, from Latin ''pensiō'', "payment") is a fund into which a sum of money is added during an employee's employment years and from which payments are drawn to support the person's retirement from work in the form of periodic payments ...

s. Townsend's $200-a-month pension plan had won a large following in California, particularly among retirees. Downeys support lead to him writing ''Why I Believe in the Townsend Plan (1936).'' In 1936, the two drifted apart, as Townsend supported Union Party presidential nominee William Lemke

William Frederick Lemke (August 13, 1878 – May 30, 1950) was an American politician who represented North Dakota in the United States House of Representatives as a member of the Republican Party. He was also the Union Party's presidential cand ...

of North Dakota

North Dakota () is a U.S. state in the Upper Midwest, named after the Native Americans in the United States, indigenous Dakota people, Dakota Sioux. North Dakota is bordered by the Canadian provinces of Saskatchewan and Manitoba to the north a ...

, and Downey remained a Democrat committed to Franklin Delano Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

.

U.S. Senate

In 1938 Downey was elected to the United States Senate where he served until his resignation in November 1950. He ran as a supporter of the proposed "Ham and Eggs

Ham and eggs is a dish combining various preparations of its main ingredients, ham and eggs. It has been described as a staple of "an old-fashioned American breakfast". It is also served as a lunch and dinner dish. Some notable people have prof ...

" government pension program and defeated incumbent

The incumbent is the current holder of an official, office or position, usually in relation to an election. In an election for president, the incumbent is the person holding or acting in the office of president before the election, whether seek ...

Senator William Gibbs McAdoo

William Gibbs McAdoo Jr.McAdoo is variously differentiated from family members of the same name:

* Dr. William Gibbs McAdoo (1820–1894) – sometimes called "I" or "Senior"

* William Gibbs McAdoo (1863–1941) – sometimes called "II" or "Ju ...

in the Democratic primary by more than 135,000 votes. Despite the strong backing McAdoo received from the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in 1800. ...

and a personal campaign appearance by President Franklin Roosevelt to endorse McAdoo, Downey won the primary and went on to win the general election, defeating Republican Philip Bancroft 54%-46%. On October 24, 1938, Downey appeared on the cover of ''Time

Time is the continued sequence of existence and events that occurs in an apparently irreversible succession from the past, through the present, into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequence events, to ...

'' magazine.

Though he had been considered a staunch liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

, Downey as a senator became a conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization i ...

Democrat who won the support of California's major oil

An oil is any nonpolar chemical substance that is composed primarily of hydrocarbons and is hydrophobic (does not mix with water) & lipophilic (mixes with other oils). Oils are usually flammable and surface active. Most oils are unsaturated ...

interests. He supported the efforts of oil companies and agribusiness

Agribusiness is the industry, enterprises, and the field of study of value chains in agriculture and in the bio-economy,

in which case it is also called bio-business or bio-enterprise.

The primary goal of agribusiness is to maximize profit w ...

to procure state, rather than federal, control of California's oil resources. He also worked to exempt the California Central Valley

The Central Valley is a broad, elongated, flat valley that dominates the interior of California. It is wide and runs approximately from north-northwest to south-southeast, inland from and parallel to the Pacific coast of the state. It covers ...

from the Reclamation Act

The Reclamation Act (also known as the Lowlands Reclamation Act or National Reclamation Act) of 1902 () is a United States federal law that funded irrigation projects for the arid lands of 20 states in the American West.

The act at first covere ...

of 1902 to assist corporate farms. In the Senate, Downey also introduced a series of pension bills, and in 1941, he was named chairman of a special Senate committee

This is a complete list of U.S. congressional committees ( standing committees and select or special committees) that are operating in the United States Senate. Senators can be a member of more than one committee.

Standing committees

, there a ...

on old-age insurance.

He took an early stand supporting a military draft

Conscription (also called the draft in the United States) is the state-mandated enlistment of people in a national service, mainly a military service. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it continues in some countries to the present day und ...

but opposed the Roosevelt administration's plans to requisition industries in time of war. During World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, he called for the creation of a committee to investigate the status of blacks and other minorities in the armed forces and advocated a postwar United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and international security, security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be ...

, international control of atomic energy, increased veterans' benefits, and federal pay raises. At the end of the war, he opposed continuation of the military draft.

During his years in the Senate, Downey often represented the interests of California's powerful motion picture industry. His shift from a liberal New Dealer to a conservative Democrat would become officially recognized after the war ended.G. J. Barker-Benfield, Catherine Clinton, Portraits of American Women: From Settlement to the Present

', Oxford University, 1998, pg. 554.

Re-election

After his narrow reelection to the Senate in 1944, defeating Republican Lieutenant Governor Frederick F. Houser by 52 percent to 48 percent, Downey began a push for the California Central Valley project, which had been initiated during the 1930s as part of the

After his narrow reelection to the Senate in 1944, defeating Republican Lieutenant Governor Frederick F. Houser by 52 percent to 48 percent, Downey began a push for the California Central Valley project, which had been initiated during the 1930s as part of the New Deal

The New Deal was a series of programs, public work projects, financial reforms, and regulations enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1939. Major federal programs agencies included the Civilian Cons ...

's vast array of public works projects, such as power dams and irrigation canals.

In a 1947 book entitled ''They Would Rule the Valley'', Downey argued that the farmers of the Central Valley, who controlled water rights based on state law, would come into conflict with the federal Bureau of Reclamation. Downey acknowledged that Central Valley farmers were technically in violation of the Reclamation Act of 1902, but defended these violations of Federal law as necessary because, in the context of California agriculture the Federal limitation was impractical. Downey's political views made him vulnerable. Helen Gahagan Douglas

Helen Gahagan Douglas (born Helen Mary Gahagan; November 25, 1900 – June 28, 1980) was an American actress and politician. Her career included success on Broadway, as a touring opera singer, and in Hollywood films. Her portrayal of the villain ...

challenged him in a primary. In 1950 Downey dropped out of the race, citing ill health, and threw his support in the Democratic primary behind Manchester Boddy

Elias Manchester Boddy (; "Boady") (November 1, 1891– May 12, 1967) was an American newspaper publisher. He rose from poverty to become the publisher of a major California newspaper and a candidate for Congress. His estate, Descanso Gardens ...

, the conservative and wealthy publisher of the ''Los Angeles Daily News

The ''Los Angeles Daily News'' is the second-largest-circulating paid daily newspaper of Los Angeles, California. It is the flagship of the Southern California News Group, a branch of Colorado-based Digital First Media.

The offices of the ''Dai ...

''. He even indicated that if Douglas won the primary, which she did, he would support Republican U.S. Representative Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

in the general election

A general election is a political voting election where generally all or most members of a given political body are chosen. These are usually held for a nation, state, or territory's primary legislative body, and are different from by-elections ( ...

. In the ensuing Douglas-Nixon race, Nixon prevailed in what his critics called a smear campaign

A smear campaign, also referred to as a smear tactic or simply a smear, is an effort to damage or call into question someone's reputation, by propounding negative propaganda. It makes use of discrediting tactics.

It can be applied to individual ...

. From this race, Nixon emerged with the sobriquet

A sobriquet ( ), or soubriquet, is a nickname, sometimes assumed, but often given by another, that is descriptive. A sobriquet is distinct from a pseudonym, as it is typically a familiar name used in place of a real name, without the need of expla ...

"Tricky Dick".Kenneth Franklin Kurz, ''Nixon's Enemies'', NTC/Contemporary Publishing Group, 1998, p. 103 Downey resigned from his Senate seat on November 30, 1950, enabling the governor to appoint Nixon, which gave him a seniority advantage over other new senators elected in 1950.

Later life and achievements

After he left the Senate, Downey practiced law inWashington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

, until his death in San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish language, Spanish for "Francis of Assisi, Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the List of Ca ...

in 1961. Downey also served as a lobbyist representing the city of Long Beach

Long Beach is a city in Los Angeles County, California. It is the 42nd-most populous city in the United States, with a population of 466,742 as of 2020. A charter city, Long Beach is the seventh-most populous city in California.

Incorporate ...

and the large petroleum concerns leasing its extensive waterfront. Upon his passing, he donated his body to the University of California

The University of California (UC) is a public land-grant research university system in the U.S. state of California. The system is composed of the campuses at Berkeley, Davis, Irvine, Los Angeles, Merced, Riverside, San Diego, San Francisco, ...

Medical Center in San Francisco. His papers are archived at the Bancroft Library

The Bancroft Library in the center of the campus of the University of California, Berkeley, is the university's primary special-collections library. It was acquired from its founder, Hubert Howe Bancroft, in 1905, with the proviso that it retai ...

in Berkeley

Berkeley most often refers to:

*Berkeley, California, a city in the United States

**University of California, Berkeley, a public university in Berkeley, California

* George Berkeley (1685–1753), Anglo-Irish philosopher

Berkeley may also refer ...

.

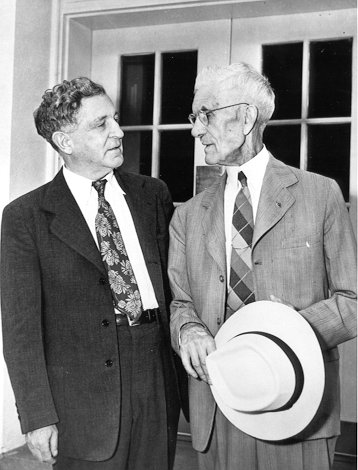

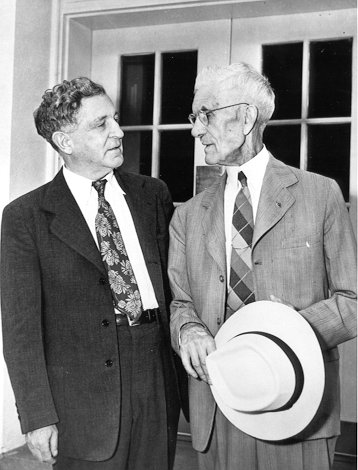

During his years in the Senate, Downey was often described as slight, grayish, and strikingly handsome. His political career in many ways typified the transformation of millions of Republican progressives who supported Theodore Roosevelt and the "Bull Moose" movement of 1912 into Democratic supporters of Franklin Roosevelt and the New Deal in the 1930s. During the 1930s and early 1940s, Downey was one of California's most significant progressive politicians. While he was often overshadowed in state politics by Republican progressives like Hiram Johnson

Hiram Warren Johnson (September 2, 1866August 6, 1945) was an American attorney and politician who served as the Governor of California, 23rd governor of California from 1911 to 1917. Johnson achieved national prominence in the early 20th century ...

and Earl Warren

Earl Warren (March 19, 1891 – July 9, 1974) was an American attorney, politician, and jurist who served as the 14th Chief Justice of the United States from 1953 to 1969. The Warren Court presided over a major shift in American constitution ...

, Downey left a significant mark because of his tireless advocacy of old-age pensions, organized labor, and racial justice. His conservative turn after his reelection in 1944, when he increasingly represented the interests of big business, large agribusiness concerns, and the oil industry, has obscured his historical reputation as a one-time liberal and progressive force in California politics.

Works

*''Onward America'', 1933. *''Courage America'', 1933. *''Why I Believe in the Townsend Plan'', 1936. *''Pensions or Penury?'', 1939. - An early book of New Deal advocacy. *''Highways to Prosperity'', 1940. *''They Would Rule the Valley'', 1947. - A book written to inform Californians about the Federal Government's efforts to impose undue economic restrictions on agriculture via the Reclamation Bureau.References

External links

*Sheridan Downey

at ''The Political Graveyard''

Guide to the Sheridan Downey Papers

at

The Bancroft Library

The Bancroft Library in the center of the campus of the University of California, Berkeley, is the university's primary special-collections library. It was acquired from its founder, Hubert Howe Bancroft, in 1905, with the proviso that it retai ...

{{DEFAULTSORT:Downey, Sheridan

1884 births

1961 deaths

California Democrats

California lawyers

California Progressives (1924)

Politicians from Laramie, Wyoming

People from San Francisco

Richard Nixon

Democratic Party United States senators from California

University of Michigan Law School alumni

Wyoming Progressives (1912)

Wyoming lawyers

Wyoming Republicans