Shays' Rebellion on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Shays Rebellion was an armed uprising in

The economy during the

The economy during the

One early protest against the government was led by

One early protest against the government was led by

Protests were also successful in shutting down courts in Great Barrington,

Protests were also successful in shutting down courts in Great Barrington,

While the government forces assembled, Shays and Day and other rebel leaders in the west organized their forces establishing regional regimental organizations that were run by democratically elected committees. Their first major target was the federal armory in Springfield. General Shepard had taken possession of the armory under orders from Governor Bowdoin, and he used its arsenal to arm a militia force of 1,200. He had done this even though the armory was federal property, not state, and he did not have permission from Secretary of War

While the government forces assembled, Shays and Day and other rebel leaders in the west organized their forces establishing regional regimental organizations that were run by democratically elected committees. Their first major target was the federal armory in Springfield. General Shepard had taken possession of the armory under orders from Governor Bowdoin, and he used its arsenal to arm a militia force of 1,200. He had done this even though the armory was federal property, not state, and he did not have permission from Secretary of War

Lincoln's march marked the end of large-scale organized resistance. Ringleaders who eluded capture fled to neighboring states, and pockets of local resistance continued. Some rebel leaders approached

Lincoln's march marked the end of large-scale organized resistance. Ringleaders who eluded capture fled to neighboring states, and pockets of local resistance continued. Some rebel leaders approached

At the time of the rebellion, the weaknesses of the federal government as constituted under the

At the time of the rebellion, the weaknesses of the federal government as constituted under the

The convention that met in Philadelphia was dominated by strong-government advocates. Delegate

The convention that met in Philadelphia was dominated by strong-government advocates. Delegate

in JSTOR

* * * * (Reprints a petition to the state legislature.) * * (The earliest account of the rebellion. Although this account was deeply unsympathetic to the rural Regulators, it became the basis for most subsequent tellings, including the many mentions of the rebellion in Massachusetts town and state histories.) * * Shattuck, Gary, ''Artful and Designing Men: The Trials of Job Shattuck and the Regulation of 1786–1787''. Mustang, OK: Tate Publishing, 2013. * * ;Fictional treatments * (Fictional depiction of the rebellion, as social commentary.) * (The rebellion is the central story of this children's novel.) * * (The rebellion plays a central role in this novel.)

Shays's Rebellion

(George Washington's Mount Vernon)

"To Gen Washington from Gen. Benjamin Lincoln" (a letter extensively covering the events of Shays' Rebellion)

(National Archives) {{DEFAULTSORT:Shays' Rebellion Agrarian politics Conflicts in 1786 Conflicts in 1787 Rebellions in the United States 18th-century rebellions 1786 in Massachusetts 1787 in Massachusetts Amherst, Massachusetts Great Barrington, Massachusetts Chicopee, Massachusetts Concord, Massachusetts Taunton, Massachusetts Northampton, Massachusetts Palmer, Massachusetts Pelham, Massachusetts Petersham, Massachusetts West Springfield, Massachusetts History of Berkshire County, Massachusetts History of Bristol County, Massachusetts History of Hampden County, Massachusetts History of Hampshire County, Massachusetts History of Middlesex County, Massachusetts History of Springfield, Massachusetts History of Worcester, Massachusetts History of Worcester County, Massachusetts Tax resistance in the United States

Western Massachusetts

Western Massachusetts, known colloquially as “Western Mass,” is a region in Massachusetts, one of the six U.S. states that make up the New England region of the United States. Western Massachusetts has diverse topography; 22 colleges and u ...

and Worcester

Worcester may refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* Worcester, England, a city and the county town of Worcestershire in England

** Worcester (UK Parliament constituency), an area represented by a Member of Parliament

* Worcester Park, London, Engla ...

in response to a debt crisis

Debt crisis is a situation in which a government (nation, state/province, county, or city etc.) loses the ability of paying back its governmental debt. When the expenditures of a government are more than its tax revenues for a prolonged period, th ...

among the citizenry and in opposition to the state government's increased efforts to collect taxes both on individuals and their trades. The fight took place mostly in and around Springfield

Springfield may refer to:

* Springfield (toponym), the place name in general

Places and locations Australia

* Springfield, New South Wales (Central Coast)

* Springfield, New South Wales (Snowy Monaro Regional Council)

* Springfield, Queenslan ...

during 1786 and 1787. American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

veteran Daniel Shays

Daniel Shays (August 1747 September 29, 1825) was an American soldier, revolutionary and farmer famous for allegedly leading Shays' Rebellion, a populist uprising against controversial debt collection and tax policies in Massachusetts in 1786� ...

led four thousand rebels (called Shaysites) in a protest against economic and civil rights injustices. In 1787, Shays' rebels marched on the federal Springfield Armory

The Springfield Armory, more formally known as the United States Armory and Arsenal at Springfield located in the city of Springfield, Massachusetts, was the primary center for the manufacture of United States military firearms from 1777 until ...

in an unsuccessful attempt to seize its weaponry and overthrow the government. The confederal government found itself unable to finance troops to put down the rebellion, and it was consequently put down by the Massachusetts State militia and a privately funded local militia.

The widely held view was that the Articles of Confederation

The Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union was an agreement among the 13 Colonies of the United States of America that served as its first frame of government. It was approved after much debate (between July 1776 and November 1777) by ...

needed to be reformed as the country's governing document, and the events of the rebellion served as a catalyst for the Constitutional Convention and the creation of the new government. There is still debate among scholars concerning the rebellion's influence on the Constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of Legal entity, entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When ...

and its ratification.

Background

The economy during the

The economy during the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

was largely subsistence agriculture in the rural parts of New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian provinces ...

, particularly in the hill towns of central and western Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett language, Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut assachusett writing systems, məhswatʃəwiːsət'' English: , ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is the most populous U.S. state, state in the New England ...

. Some residents in these areas had few assets beyond their land, and they bartered with one another for goods and services. In lean times, farmers might obtain goods on credit from suppliers in local market towns who would be paid when times were better. In contrast, there was a market economy

A market economy is an economic system in which the decisions regarding investment, production and distribution to the consumers are guided by the price signals created by the forces of supply and demand, where all suppliers and consumers ...

in the more economically developed coastal areas of Massachusetts Bay

Massachusetts Bay is a bay on the Gulf of Maine that forms part of the central coastline of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

Description

The bay extends from Cape Ann on the north to Plymouth Harbor on the south, a distance of about . Its ...

and in the fertile Connecticut River Valley

The Connecticut River is the longest river in the New England region of the United States, flowing roughly southward for through four states. It rises 300 yards (270 m) south of the U.S. border with Quebec, Canada, and discharges at Long Island ...

, driven by the activities of wholesale merchants dealing with Europe and the West Indies. The state government was dominated by this merchant class.

When the Revolutionary War ended in 1783, Massachusetts merchants' European business partners refused to extend lines of credit to them and insisted that they pay for goods with hard currency

In macroeconomics, hard currency, safe-haven currency, or strong currency is any globally traded currency that serves as a reliable and stable store of value. Factors contributing to a currency's ''hard'' status might include the stability and ...

, despite the country-wide shortage of such currency. Merchants began to demand the same from their local business partners, including those operating in the market towns in the state's interior. Many of these merchants passed on this demand to their customers, although Governor John Hancock

John Hancock ( – October 8, 1793) was an American Founding Father, merchant, statesman, and prominent Patriot of the American Revolution. He served as president of the Second Continental Congress and was the first and third Governor of the ...

did not impose hard currency demands on poorer borrowers and refused to actively prosecute the collection of delinquent taxes. The rural farming population was generally unable to meet the demands of merchants and the civil authorities, and some began to lose their land and other possessions when they were unable to fulfill their debt and tax obligations. This led to strong resentments against tax collectors and the courts, where creditors obtained judgments against debtors, and where tax collectors obtained judgments authorizing property seizures. A farmer identified as "Plough Jogger" summarized the situation at a meeting convened by aggrieved commoners:Zinn, p. 91

I have been greatly abused, have been obliged to do more than my part in the war, been loaded with class rates, town rates, province rates, Continental rates, and all rates ... been pulled and hauled by sheriffs, constables, and collectors, and had my cattle sold for less than they were worth... The great men are going to get all we have and I think it is time for us to rise and put a stop to it, and have no more courts, nor sheriffs, nor collectors nor lawyers.Veterans had received little pay during the war and faced added difficulty collecting payments owed to them from the State or the

Congress of the Confederation

The Congress of the Confederation, or the Confederation Congress, formally referred to as the United States in Congress Assembled, was the governing body of the United States of America during the Confederation period, March 1, 1781 – Mar ...

. Some soldiers began to organize protests against these oppressive economic conditions. In 1780, Daniel Shays resigned from the army unpaid and went home to find himself in court for non-payment of debts. He soon realized that he was not alone in his inability to pay his debts and began organizing for debt relief.Zinn, p. 93

Early rumblings

One early protest against the government was led by

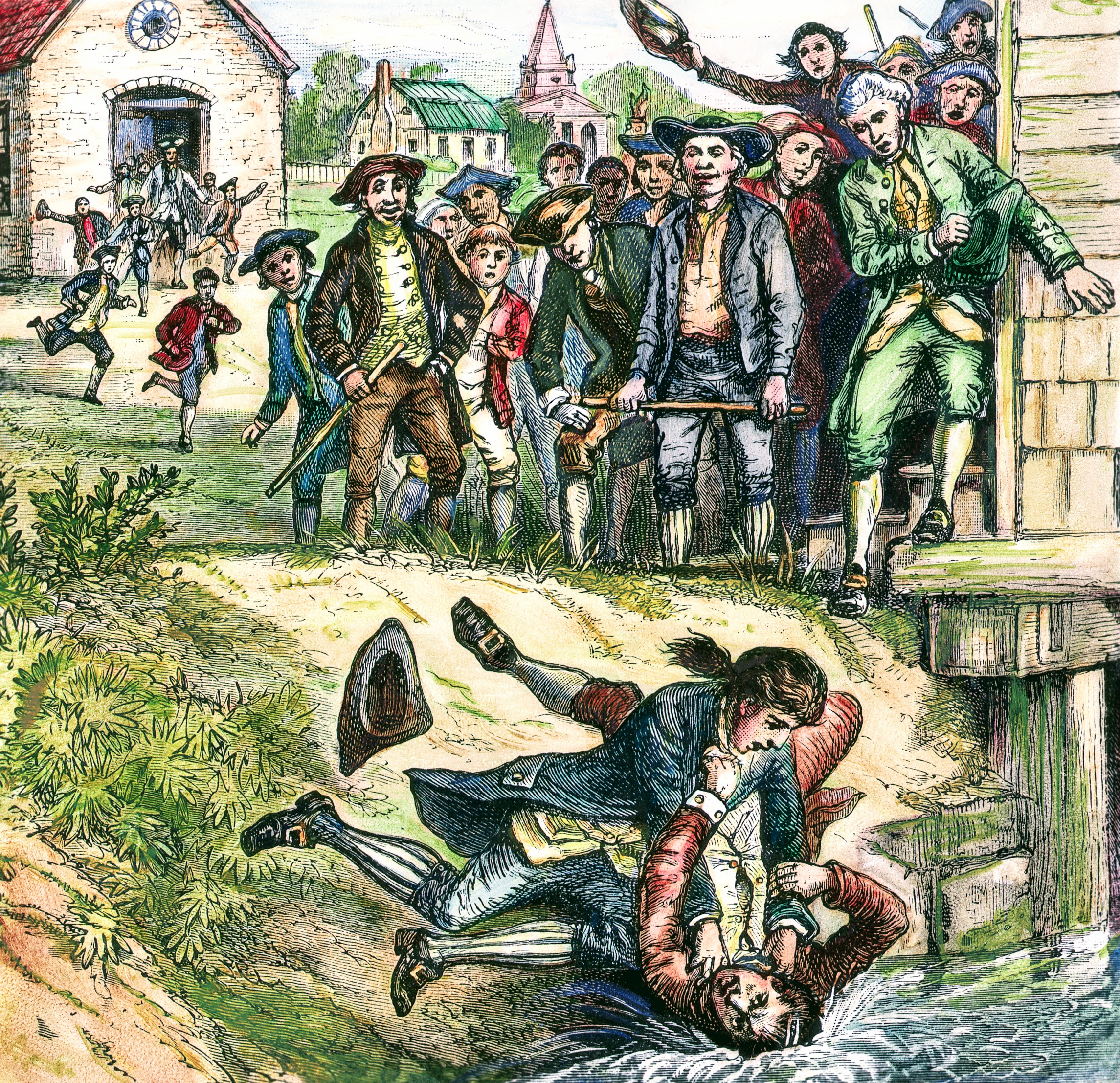

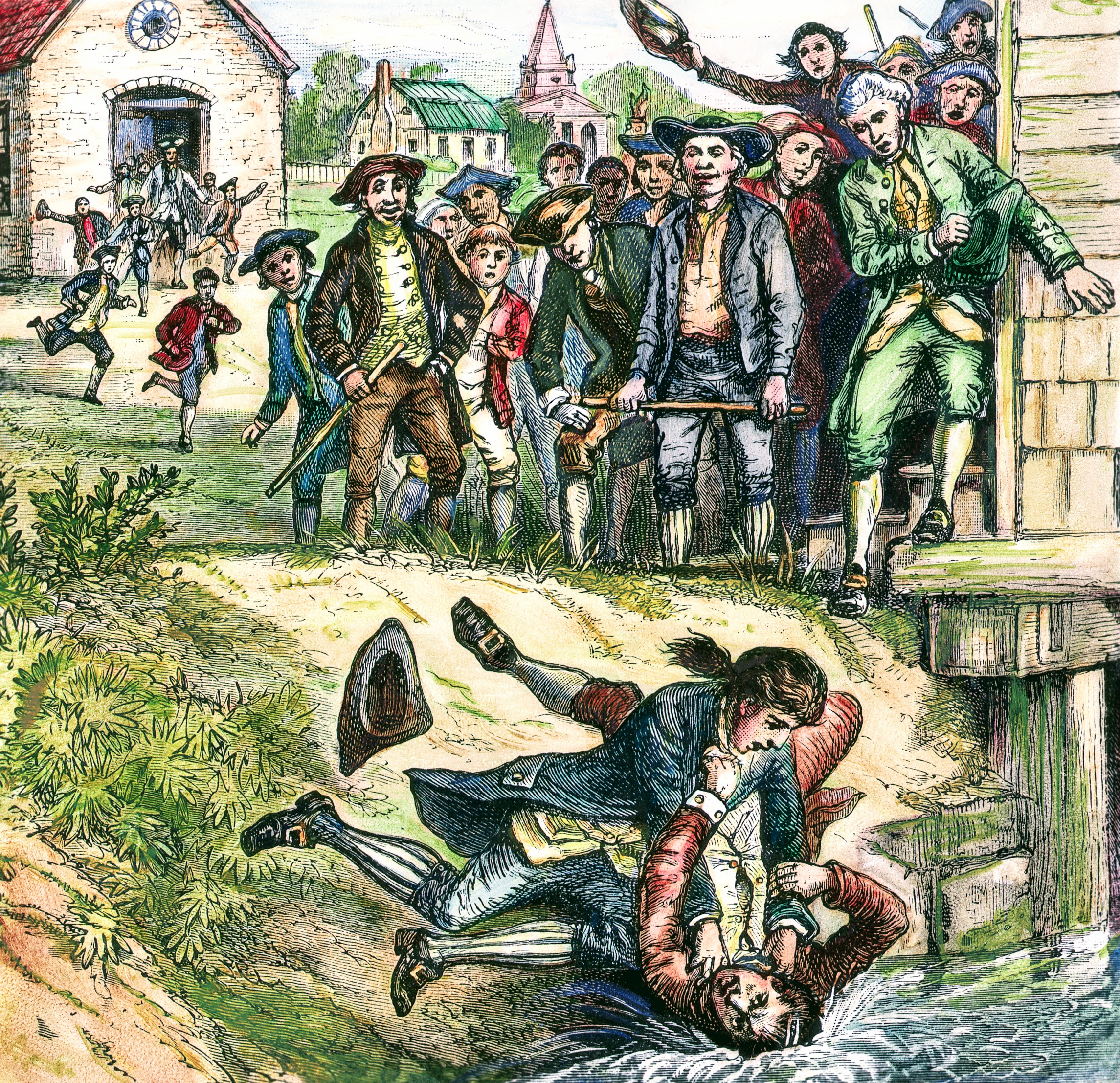

One early protest against the government was led by Job Shattuck

Job Shattuck (February 11, 1736 – January 13, 1819) was a British colonial soldier during the Seven Years' War and a member of the Massachusetts state militia during the American Revolutionary War. He first served with the British in the 1755 ...

of Groton, Massachusetts

Groton is a town in northwestern Middlesex County, Massachusetts, United States, within the Greater Boston metropolitan area. The population was 11,315 at the 2020 census. It is home to two prep schools: Lawrence Academy at Groton, founded in 1 ...

in 1782, who organized residents to physically prevent tax collectors from doing their work. A second, larger-scale protest took place in Uxbridge, Massachusetts

Uxbridge is a town in Worcester County, Massachusetts first colonized in 1662 and incorporated in 1727. It was originally part of the town of Mendon, MA, Mendon, and named for the Marquess of Anglesey, Earl of Uxbridge. The town is located south ...

on the Rhode Island border on February 3, 1783, when a mob seized property that had been confiscated by a constable and returned it to its owners. Governor Hancock ordered the sheriff to suppress these actions.Bacon, p. 1:148

Most rural communities attempted to use the legislative process to gain relief. Petitions and proposals were repeatedly submitted to the state legislature to issue paper currency, which would depreciate the currency and make it possible to pay a high-value debt with lower-valued paper. The merchants were opposed to the idea, including James Bowdoin

James Bowdoin II (; August 7, 1726 – November 6, 1790) was an American political and intellectual leader from Boston, Massachusetts, during the American Revolution and the following decade. He initially gained fame and influence as a wealthy ...

, since they stood to lose from such measures, and the proposals were repeatedly rejected.

Governor Hancock resigned in early 1785 citing health reasons, though some suggested that he was anticipating trouble. Bowdoin had repeatedly lost to Hancock in earlier elections, but he was elected governor that year—and matters became more severe. He stepped up civil actions to collect back taxes, and the legislature exacerbated the situation by levying an additional property tax to raise funds for the state's portion of foreign debt payments.Richards, pp. 87–88 Even comparatively conservative commentators such as John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, attorney, diplomat, writer, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Befor ...

observed that these levies were "heavier than the People could bear".

Shutting down the courts

Protests in rural Massachusetts turned into direct action in August 1786 after the state legislature adjourned without considering the many petitions that had been sent to Boston. On August 29, a well-organized force of protestors formed inNorthampton, Massachusetts

The city of Northampton is the county seat of Hampshire County, Massachusetts, United States. As of the 2020 census, the population of Northampton (including its outer villages, Florence and Leeds) was 29,571.

Northampton is known as an acade ...

and successfully prevented the county court from sitting. The leaders of this force proclaimed that they were seeking relief from the burdensome judicial processes that were depriving the people of their land and possessions. They called themselves ''Regulators'', a reference to the Regulator movement

The Regulator Movement, also known as the Regulator Insurrection, War of Regulation, and War of the Regulation, was an uprising in Province of North Carolina, Provincial North Carolina from 1766 to 1771 in which citizens took up arms against colo ...

of North Carolina

North Carolina () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the 28th largest and 9th-most populous of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, Georgia and So ...

which sought to reform corrupt practices in the late 1760s.

Governor Bowdoin issued a proclamation on September 2 denouncing such mob action, but he took no military measures beyond planning a militia response to future actions. The court was then shut down in Worcester, Massachusetts

Worcester ( , ) is a city and county seat of Worcester County, Massachusetts, United States. Named after Worcester, England, the city's population was 206,518 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, making it the second-List of cities i ...

by similar action on September 5, but the county militia refused to turn out, as it was composed mainly of men sympathetic to the protestors. Governors of the neighboring states acted decisively, calling out the militia to hunt down the ringleaders in their own states after the first such protests. Matters were resolved without violence in Rhode Island

Rhode Island (, like ''road'') is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is the List of U.S. states by area, smallest U.S. state by area and the List of states and territories of the United States ...

because the "country party" gained control of the legislature in 1786 and enacted measures forcing its merchants to trade debt instruments for devalued currency. Boston's merchants were concerned by this, especially Bowdoin who held more than £3,000 in Massachusetts notes.

Daniel Shays had participated in the Northampton action and began to take a more active role in the uprising in November, though he firmly denied that he was one of its leaders. The Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts indicted 11 leaders of the rebellion as "disorderly, riotous, and seditious persons". The court was scheduled to meet next in Springfield, Massachusetts

Springfield is a city in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, United States, and the seat of Hampden County. Springfield sits on the eastern bank of the Connecticut River near its confluence with three rivers: the western Westfield River, the ...

on September 26, and Shays organized an attempt to shut it down in Northampton, while Luke Day organized an attempt in Springfield.Holland, pp. 245–247 They were anticipated by William Shepard

William Shepard (Contemporary records, which used the Julian calendar and the Annunciation Style of enumerating years, recorded his birth as November 20, 1737. The provisions of the British Calendar (New Style) Act 1750, implemented in 1752, ...

, the local militia commander, who began gathering government-supporting militia the Saturday before the court was to sit, and he had 300 men protecting the Springfield courthouse by opening time. Shays and Day were able to recruit a similar number but chose only to demonstrate, exercising their troops outside of Shepard's lines rather than attempting to seize the building. The judges first postponed hearings and then adjourned on the 28th without hearing any cases. Shepard withdrew his force (which had grown to some 800 men) to the Springfield Armory

The Springfield Armory, more formally known as the United States Armory and Arsenal at Springfield located in the city of Springfield, Massachusetts, was the primary center for the manufacture of United States military firearms from 1777 until ...

, which was rumored to be the target of the protestors.

Protests were also successful in shutting down courts in Great Barrington,

Protests were also successful in shutting down courts in Great Barrington, Concord

Concord may refer to:

Meaning "agreement"

* Pact or treaty, frequently between nations (indicating a condition of harmony)

* Harmony, in music

* Agreement (linguistics), a change in the form of a word depending on grammatical features of other ...

, and Taunton, Massachusetts

Taunton is a city in Bristol County, Massachusetts, Bristol County, Massachusetts, United States. It is the county seat, seat of Bristol County. Taunton is situated on the Taunton River which winds its way through the city on its way to Mount ...

in September and October. James Warren wrote to John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, attorney, diplomat, writer, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Befor ...

on October 22, "We are now in a state of Anarchy and Confusion bordering on Civil War." Courts were able to meet in the larger towns and cities, but they required protection of the militia which Bowdoin called out for the purpose.Morse, p. 208 Governor Bowdoin commanded the legislature to "vindicate the insulted dignity of government". Samuel Adams

Samuel Adams ( – October 2, 1803) was an American statesman, political philosopher, and a Founding Father of the United States. He was a politician in colonial Massachusetts, a leader of the movement that became the American Revolution, and ...

claimed that foreigners ("British emissaries") were instigating treason among citizens. Adams helped draw up a Riot Act

The Riot Act (1 Geo.1 St.2 c.5), sometimes called the Riot Act 1714 or the Riot Act 1715, was an act of the Parliament of Great Britain which authorised local authorities to declare any group of 12 or more people to be unlawfully assembled and o ...

and a resolution suspending ''habeas corpus

''Habeas corpus'' (; from Medieval Latin, ) is a recourse in law through which a person can report an unlawful detention or imprisonment to a court and request that the court order the custodian of the person, usually a prison official, t ...

'' so the authorities could legally keep people in jail without trial.

Adams proposed a new legal distinction that rebellion in a republic should be punished by execution

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the State (polity), state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to ...

. The legislature also moved to make some concessions on matters that upset farmers, saying that certain old taxes could now be paid in goods instead of hard currency. These measures were followed by one prohibiting speech critical of the government and offering pardons to protestors willing to take an oath of allegiance. These legislative actions were unsuccessful in quelling the protests, and the suspension of ''habeas corpus'' alarmed many.

Warrants were issued for the arrest of several of the protest ringleaders, and a posse of some 300 men rode to Groton on November 28 to arrest Job Shattuck and other rebel leaders in the area. Shattuck was chased down and arrested on the 30th and was wounded by a sword slash in the process. This action and the arrest of other protest leaders in the eastern parts of the state angered those in the west, and they began to organize an overthrow of the state government. "The seeds of war are now sown", wrote one correspondent in Shrewsbury

Shrewsbury ( , also ) is a market town, civil parish, and the county town of Shropshire, England, on the River Severn, north-west of London; at the 2021 census, it had a population of 76,782. The town's name can be pronounced as either 'Sh ...

, and by mid-January rebel leaders spoke of smashing the "tyrannical government of Massachusetts".

Rebellion

The federal government had been unable to recruit soldiers for the army because of a lack of funding, so Massachusetts leaders decided to act independently. On January 4, 1787, Governor Bowdoin proposed creating a privately funded militia army. Former Continental Army GeneralBenjamin Lincoln

Benjamin Lincoln (January 24, 1733 ( O.S. January 13, 1733) – May 9, 1810) was an American army officer. He served as a major general in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War. Lincoln was involved in three major surrender ...

solicited funds and raised more than £6,000 from more than 125 merchants by the end of January. The 3,000 militiamen who were recruited into this army were almost entirely from the eastern counties of Massachusetts, and they marched to Worcester on January 19.

While the government forces assembled, Shays and Day and other rebel leaders in the west organized their forces establishing regional regimental organizations that were run by democratically elected committees. Their first major target was the federal armory in Springfield. General Shepard had taken possession of the armory under orders from Governor Bowdoin, and he used its arsenal to arm a militia force of 1,200. He had done this even though the armory was federal property, not state, and he did not have permission from Secretary of War

While the government forces assembled, Shays and Day and other rebel leaders in the west organized their forces establishing regional regimental organizations that were run by democratically elected committees. Their first major target was the federal armory in Springfield. General Shepard had taken possession of the armory under orders from Governor Bowdoin, and he used its arsenal to arm a militia force of 1,200. He had done this even though the armory was federal property, not state, and he did not have permission from Secretary of War Henry Knox

Henry Knox (July 25, 1750 – October 25, 1806), a Founding Father of the United States, was a senior general of the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War, serving as chief of artillery in most of Washington's campaigns. Following the ...

.

The insurgents were organized into three major groups and intended to surround and attack the armory simultaneously. Shays had one group east of Springfield near Palmer

Palmer may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Palmer (pilgrim), a medieval European pilgrim to the Holy Land

* Palmer (given name), including a list of people and fictional characters

* Palmer (surname), including a list of people and ...

. Luke Day had a second force across the Connecticut River in West Springfield. A third force under Eli Parsons was situated to the north at Chicopee. The rebels originally had planned their assault for January 25. At the last moment, Day changed this date and sent a message to Shays indicating that he would not be ready to attack until the 26th. Day's message was intercepted by Shepard's men. As such, the militias of Shays and Parsons approached the armory on the 25th not knowing that they would have no support from the west.Richards, p. 29 Instead, they found Shepard's militia waiting for them. Shepard first ordered warning shots fired over the heads of Shays' men. He then ordered two cannons to fire grape shot

Grapeshot is a type of artillery round invented by a British Officer during the Napoleonic Wars. It was used mainly as an anti infantry round, but had other uses in naval combat.

In artillery, a grapeshot is a type of ammunition that consists of ...

. Four Shaysites were killed and 20 wounded. There was no musket fire from either side. The rebel advance collapsed with most of the rebel forces fleeing north. Both Shays' men and Day's men eventually regrouped at Amherst, Massachusetts

Amherst () is a New England town, town in Hampshire County, Massachusetts, United States, in the Connecticut River valley. As of the 2020 census, the population was 39,263, making it the highest populated municipality in Hampshire County (althoug ...

.

General Lincoln immediately began marching west from Worcester with the 3,000 men that had been mustered. The rebels moved generally north and east to avoid him, eventually establishing a camp at Petersham, Massachusetts

Petersham is a town in Worcester County, Massachusetts, United States. The population was 1,194 at the 2020 census. Petersham is home to a considerable amount of conservation land, including the Quabbin Reservation, Harvard Forest, the Swift R ...

. They raided the shops of local merchants for supplies along the way and took some of the merchants hostage. Lincoln pursued them and reached Pelham, Massachusetts

Pelham is a town in Hampshire County, Massachusetts, United States. The population was 1,280 at the 2020 census. Its ZIP Code is shared with Amherst.

Pelham is part of the Springfield, Massachusetts Metropolitan Statistical Area.

History

Pe ...

on February 2, some from Petersham. He led his militia on a forced march to Petersham through a bitter snowstorm on the night of February 3–4, arriving early in the morning. They surprised the rebel camp so thoroughly that the rebels scattered "without time to call in their out parties or even their guards". Lincoln claimed to capture 150 men but none of them were officers, and historian Leonard Richards has questioned the veracity of the report. Most of the leadership escaped north into New Hampshire and Vermont, where they were sheltered despite repeated demands that they be returned to Massachusetts for trial.

Aftermath

Lincoln's march marked the end of large-scale organized resistance. Ringleaders who eluded capture fled to neighboring states, and pockets of local resistance continued. Some rebel leaders approached

Lincoln's march marked the end of large-scale organized resistance. Ringleaders who eluded capture fled to neighboring states, and pockets of local resistance continued. Some rebel leaders approached Lord Dorchester

Guy Carleton, 1st Baron Dorchester (3 September 1724 – 10 November 1808), known between 1776 and 1786 as Sir Guy Carleton, was an Anglo-Irish soldier and administrator. He twice served as Governor of the Province of Quebec, from 1768 to 177 ...

for assistance, the British governor of the Province of Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirteen p ...

who reportedly promised assistance in the form of Mohawk Mohawk may refer to:

Related to Native Americans

* Mohawk people, an indigenous people of North America (Canada and New York)

*Mohawk language, the language spoken by the Mohawk people

* Mohawk hairstyle, from a hairstyle once thought to have been ...

warriors led by Joseph Brant

Thayendanegea or Joseph Brant (March 1743 – November 24, 1807) was a Mohawk people, Mohawk military and political leader, based in present-day New York (state), New York, who was closely associated with Kingdom of Great Britain, Great B ...

. Dorchester's proposal was vetoed in London, however, and no assistance came to the rebels. The same day that Lincoln arrived at Petersham, the state legislature passed bills authorizing a state of martial law and giving the governor broad powers to act against the rebels. The bills also authorized state payments to reimburse Lincoln and the merchants who had funded the army and authorized the recruitment of additional militia. On February 16, 1787, the Massachusetts legislature passed the Disqualification Act to prevent a legislative response by rebel sympathizers. This bill forbade any acknowledged rebels from holding a variety of elected and appointed offices.

Most of Lincoln's army melted away in late February as enlistments expired, and he commanded only 30 men at a base in Pittsfield

Pittsfield is the largest city and the county seat of Berkshire County, Massachusetts, United States. It is the principal city of the Pittsfield, Massachusetts Metropolitan Statistical Area which encompasses all of Berkshire County. Pittsfield� ...

by the end of the month. In the meantime, some 120 rebels had regrouped in New Lebanon, New York

New Lebanon is a town in Columbia County, New York, United States, southeast of Albany. In 1910, 1,378 people lived in New Lebanon. The population was 2,305 at the 2010 census.

The town of New Lebanon is in the northeastern corner of Columbia ...

, and they crossed the border on February 27, marching first on Stockbridge, Massachusetts

Stockbridge is a town in Berkshire County in Western Massachusetts, United States. It is part of the Pittsfield, Massachusetts, Metropolitan Statistical Area. The population was 2,018 at the 2020 census. A year-round resort area, Stockbridge is h ...

, a major market town in the southwestern corner of the state. They raided the shops of merchants and the homes of merchants and local professionals. This came to the attention of Brigadier John Ashley, who mustered a force of some 80 men and caught up with the rebels in nearby Sheffield

Sheffield is a city status in the United Kingdom, city in South Yorkshire, England, whose name derives from the River Sheaf which runs through it. The city serves as the administrative centre of the City of Sheffield. It is Historic counties o ...

late in the day for the bloodiest encounter of the rebellion: 30 rebels were wounded (one mortally), at least one government soldier was killed, and many were wounded. Ashley was further reinforced after the encounter, and he reported taking 150 prisoners.

Consequences

Four thousand people signed confessions acknowledging participation in the events of the rebellion in exchange for amnesty. Several hundred participants were eventually indicted on charges relating to the rebellion, but most of these were pardoned under a general amnesty that excluded only a few ringleaders. Eighteen men were convicted and sentenced to death, but most of these had their sentences commuted or overturned on appeal, or were pardoned. John Bly and Charles Rose, however, were hanged on December 6, 1787. They were also accused of a common-law crime, as both were looters. Shays was pardoned in 1788 and he returned to Massachusetts from hiding in the Vermont woods. He was vilified by the Boston press, who painted him as an archetypal anarchist opposed to the government. He later moved to theConesus, New York

Conesus is a town in Livingston County, New York, United States. The population was 2,473 at the 2010 census. The name is derived from a native word meaning "berry place".

Conesus is on the county's east border, and is north of Dansville.

His ...

area, where he died poor and obscure in 1825.Zinn, p. 95

The crushing of the rebellion and the harsh terms of reconciliation imposed by the Disqualification Act all worked against Governor Bowdoin politically. He received few votes from the rural parts of the state and was trounced by John Hancock

John Hancock ( – October 8, 1793) was an American Founding Father, merchant, statesman, and prominent Patriot of the American Revolution. He served as president of the Second Continental Congress and was the first and third Governor of the ...

in the gubernatorial election of 1787. The military victory was tempered by tax changes in subsequent years. The legislature cut taxes and placed a moratorium on debts and also refocused state spending away from interest payments, resulting in a 30-percent decline in the value of Massachusetts securities as those payments fell in arrears.

Vermont was an unrecognized independent republic that had been seeking independent statehood from New York's claims to the territory. It became an unexpected beneficiary of the rebellion by sheltering the rebel ringleaders. Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton (January 11, 1755 or 1757July 12, 1804) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first United States secretary of the treasury from 1789 to 1795.

Born out of wedlock in Charlest ...

broke from other New Yorkers, including major landowners with claims on Vermont territory, calling for the state to recognize and support Vermont's bid for admission to the union. He cited Vermont's de facto independence and its ability to cause trouble by providing support to the discontented from neighboring states, and he introduced legislation that broke the impasse between New York and Vermont. Vermonters responded favorably to the overture, publicly pushing Eli Parsons and Luke Day out of the state (but quietly continuing to support others). Vermont became the fourteenth state after negotiations with New York and the passage of the new constitution.

Impact on the Constitution

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

was serving as ambassador to France at the time and refused to be alarmed by Shays' Rebellion. He argued in a letter to James Madison on January 30, 1787, that occasional rebellion serves to preserve freedoms. In a letter to William Stephens Smith on November 13, 1787, Jefferson wrote, "The tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants. It is its natural manure."Foner, p. 219 In contrast, George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of th ...

had been calling for constitutional reform for many years, and he wrote in a letter dated October 31, 1786, to Henry Lee, "You talk, my good sir, of employing influence to appease the present tumults in Massachusetts. I know not where that influence is to be found, or, if attainable, that it would be a proper remedy for the disorders. Influence is not government. Let us have a government by which our lives, liberties, and properties will be secured, or let us know the worst at once."

Influence upon the Constitutional Convention

At the time of the rebellion, the weaknesses of the federal government as constituted under the

At the time of the rebellion, the weaknesses of the federal government as constituted under the Articles of Confederation

The Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union was an agreement among the 13 Colonies of the United States of America that served as its first frame of government. It was approved after much debate (between July 1776 and November 1777) by ...

were apparent to many. A vigorous debate was going on throughout the states on the need for a stronger central government, with Federalists

The term ''federalist'' describes several political beliefs around the world. It may also refer to the concept of parties, whose members or supporters called themselves ''Federalists''.

History Europe federation

In Europe, proponents of de ...

arguing for the idea, and Anti-Federalists

Anti-Federalism was a late-18th century political movement that opposed the creation of a stronger U.S. federal government and which later opposed the ratification of the 1787 Constitution. The previous constitution, called the Articles of Con ...

opposing them. Historical opinion is divided on what sort of role the rebellion played in the formation and later ratification of the United States Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the Supremacy Clause, supreme law of the United States, United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, in 1789. Originally comprising seven ar ...

, although most scholars agree that it played some role, at least temporarily drawing some anti-Federalists to the strong government side.

By early 1785, many influential merchants and political leaders were already agreed that a stronger central government was needed. Shortly after Shays' Rebellion broke out, delegates from five states met in Annapolis, Maryland from September 11–14, 1786, and they concluded that vigorous steps were needed to reform the federal government, but they disbanded because of a lack of full representation and authority, calling for a convention of all the states to be held in Philadelphia in May 1787. Historian Robert Feer notes that several prominent figures had hoped that the convention would fail, requiring a larger-scale convention, and French diplomat Louis-Guillaume Otto

Louis-Guillaume Otto, comte de Mosloy (7 August 1754 – 9 November 1817) was a Germano- French diplomat.

Life

A student of Christoph Wilhelm von Koch and a friend of Emmanuel-Joseph Sieyès at the University of Strasbourg, Ludwig Otto graduat ...

thought that the convention was intentionally broken off early to achieve this end.

In early 1787, John Jay

John Jay (December 12, 1745 – May 17, 1829) was an American statesman, patriot, diplomat, abolitionist, signatory of the Treaty of Paris, and a Founding Father of the United States. He served as the second governor of New York and the first ...

wrote that the rural disturbances and the inability of the central government to fund troops in response made "the inefficiency of the Federal government more and more manifest". Henry Knox

Henry Knox (July 25, 1750 – October 25, 1806), a Founding Father of the United States, was a senior general of the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War, serving as chief of artillery in most of Washington's campaigns. Following the ...

observed that the uprising in Massachusetts clearly influenced local leaders who had previously opposed a strong federal government. Historian David Szatmary writes that the timing of the rebellion "convinced the elites of sovereign states that the proposed gathering at Philadelphia must take place". Some states delayed choosing delegates to the proposed convention, including Massachusetts, in part because it resembled the "extra-legal" conventions organized by the protestors before the rebellion became violent.

Influence upon the Constitution

The convention that met in Philadelphia was dominated by strong-government advocates. Delegate

The convention that met in Philadelphia was dominated by strong-government advocates. Delegate Oliver Ellsworth

Oliver Ellsworth (April 29, 1745 – November 26, 1807) was a Founding Father of the United States, attorney, jurist, politician, and diplomat. Ellsworth was a framer of the United States Constitution, United States senator from Connecticut ...

of Connecticut argued that because the people could not be trusted (as exemplified by Shays' Rebellion), the members of the federal House of Representatives should be chosen by state legislatures, not by popular vote. The example of Shays' Rebellion may also have been influential in the addition of language to the constitution concerning the ability of states to manage domestic violence, and their ability to demand the return of individuals from other states for trial.

The rebellion also played a role in the discussion of the number of chief executives the United States would have going forward. While mindful of tyranny, delegates of the Constitutional Convention thought that the single executive would be more effective in responding to national disturbances.

Federalists cited the rebellion as an example of the confederation government's weaknesses, while opponents such as Elbridge Gerry

Elbridge Gerry (; July 17, 1744 – November 23, 1814) was an American Founding Father, merchant, politician, and diplomat who served as the fifth vice president of the United States under President James Madison from 1813 until his death in 18 ...

, a merchant speculator and Massachusetts delegate from Essex County, thought that a federal response to the rebellion would have been even worse than that of the state. He was one of the few convention delegates who refused to sign the new constitution, although his reasons for doing so did not stem from the rebellion.

Influence upon ratification

When the constitution had been drafted, Massachusetts was viewed by Federalists as a state that might not ratify it, because of widespread anti-Federalist sentiment in the rural parts of the state. Massachusetts Federalists, including Henry Knox, were active in courting swing votes in the debates leading up to the state's ratifying convention in 1788. When the vote was taken on February 6, 1788, representatives of rural communities involved in the rebellion voted against ratification by a wide margin, but the day was carried by a coalition of merchants, urban elites, and market town leaders. The state ratified the constitution by a vote of 187 to 168. Historians are divided on the impact the rebellion had on the ratification debates. Robert Feer notes that major Federalist pamphleteers rarely mentioned it and that some anti-Federalists used the fact that Massachusetts survived the rebellion as evidence that a new constitution was unnecessary. Leonard Richards counters that publications like the ''Pennsylvania Gazette

''The Pennsylvania Gazette'' was one of the United States' most prominent newspapers from 1728 until 1800. In the several years leading up to the American Revolution the paper served as a voice for colonial opposition to British colonial rule, ...

'' explicitly tied anti-Federalist opinion to the rebel cause, calling opponents of the new constitution "Shaysites" and the Federalists "Washingtonians".

David Szatmary argues that debate in some states was affected, particularly in Massachusetts, where the rebellion had a polarizing effect. Richards records Henry Jackson's observation that opposition to ratification in Massachusetts was motivated by "that cursed spirit of insurgency", but that broader opposition in other states originated in other constitutional concerns expressed by Elbridge Gerry, who published a widely distributed pamphlet outlining his concerns about the vagueness of some of the powers granted in the constitution and its lack of a Bill of Rights

A bill of rights, sometimes called a declaration of rights or a charter of rights, is a list of the most important rights to the citizens of a country. The purpose is to protect those rights against infringement from public officials and pri ...

.

The military powers enshrined in the constitution were soon put to use by President George Washington. After the passage by the United States Congress of the Whiskey Act

The Whiskey Rebellion (also known as the Whiskey Insurrection) was a violent tax protest in the United States beginning in 1791 and ending in 1794 during the presidency of George Washington. The so-called "whiskey tax" was the first tax impo ...

, protest against the taxes it imposed began in western Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

. The protests escalated and Washington led federal and state militia to put down what is now known as the Whiskey Rebellion

The Whiskey Rebellion (also known as the Whiskey Insurrection) was a violent tax protest in the United States beginning in 1791 and ending in 1794 during the presidency of George Washington. The so-called "whiskey tax" was the first tax impo ...

.

Memorials

The events and people of the uprising are commemorated in the towns where they lived and those where events took place. Sheffield erected a memorial (pictured above) marking the site of the "last battle” on the Sheffield- Egremont Road inSheffield

Sheffield is a city status in the United Kingdom, city in South Yorkshire, England, whose name derives from the River Sheaf which runs through it. The city serves as the administrative centre of the City of Sheffield. It is Historic counties o ...

, across the road from the Appalachian Trail

The Appalachian Trail (also called the A.T.), is a hiking trail in the Eastern United States, extending almost between Springer Mountain in Georgia and Mount Katahdin in Maine, and passing through 14 states.Gailey, Chris (2006)"Appalachian Tr ...

trailhead. Pelham memorialized Daniel Shays by naming the portion of US Route 202

U.S. Route 202 (US 202) is a spur route of US 2. It follows a northeasterly and southwesterly direction stretching from Delaware to Maine, also traveling through the states of Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York, Connecticut, Mass ...

that runs through Pelham the Daniel Shays Highway. A statue of General Shepard was erected in his hometown of Westfield.

In the town of Petersham, Massachusetts

Petersham is a town in Worcester County, Massachusetts, United States. The population was 1,194 at the 2020 census. Petersham is home to a considerable amount of conservation land, including the Quabbin Reservation, Harvard Forest, the Swift R ...

, a memorial was erected in 1927 by the New England Society of Brooklyn, New York in commemoration of General Benjamin Lincoln's rout of the Shaysite forces there on the morning of February 4. The lengthy inscription is typical of the traditional, pro-government interpretation, ending with the line, "Obedience to the law is true liberty."

See also

*Fries's Rebellion

Fries's Rebellion (), also called House Tax Rebellion, the Home Tax Rebellion and, in Pennsylvania German, the Heesses-Wasser Uffschtand, was an armed tax revolt among Pennsylvania Dutch farmers between 1799 and 1800. It was the third of three t ...

* List of incidents of civil unrest in the United States

Listed are major episodes of civil unrest in the United States. This list does not include the numerous incidents of destruction and violence associated with various sporting events.

18th century

*1783 – Pennsylvania Mutiny of 1783, June 20 ...

* Paper Money Riot

* Tax resistance in the United States

Tax resistance in the United States has been practiced at least since colonial times, and has played important parts in American history.

Tax resistance is the refusal to pay a tax, usually by means that bypass established legal norms, as a means ...

* Whiskey Rebellion

The Whiskey Rebellion (also known as the Whiskey Insurrection) was a violent tax protest in the United States beginning in 1791 and ending in 1794 during the presidency of George Washington. The so-called "whiskey tax" was the first tax impo ...

Notes

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

;Additional scholarly sources * * Gross, Robert A. "A Yankee Rebellion? The Regulators, New England, and the New Nation," ''New England Quarterly'' (2009) 82#1 pp. 112–13in JSTOR

* * * * (Reprints a petition to the state legislature.) * * (The earliest account of the rebellion. Although this account was deeply unsympathetic to the rural Regulators, it became the basis for most subsequent tellings, including the many mentions of the rebellion in Massachusetts town and state histories.) * * Shattuck, Gary, ''Artful and Designing Men: The Trials of Job Shattuck and the Regulation of 1786–1787''. Mustang, OK: Tate Publishing, 2013. * * ;Fictional treatments * (Fictional depiction of the rebellion, as social commentary.) * (The rebellion is the central story of this children's novel.) * * (The rebellion plays a central role in this novel.)

External links

Shays's Rebellion

(George Washington's Mount Vernon)

"To Gen Washington from Gen. Benjamin Lincoln" (a letter extensively covering the events of Shays' Rebellion)

(National Archives) {{DEFAULTSORT:Shays' Rebellion Agrarian politics Conflicts in 1786 Conflicts in 1787 Rebellions in the United States 18th-century rebellions 1786 in Massachusetts 1787 in Massachusetts Amherst, Massachusetts Great Barrington, Massachusetts Chicopee, Massachusetts Concord, Massachusetts Taunton, Massachusetts Northampton, Massachusetts Palmer, Massachusetts Pelham, Massachusetts Petersham, Massachusetts West Springfield, Massachusetts History of Berkshire County, Massachusetts History of Bristol County, Massachusetts History of Hampden County, Massachusetts History of Hampshire County, Massachusetts History of Middlesex County, Massachusetts History of Springfield, Massachusetts History of Worcester, Massachusetts History of Worcester County, Massachusetts Tax resistance in the United States