Shanghainese dialect on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Shanghainese language, also known as the Shanghai dialect, or Hu language, is a variety of

Shanghainese macroscopically is spoken in Shanghai and parts of eastern

Shanghainese macroscopically is spoken in Shanghai and parts of eastern

Pott, F. L. Hawks (Francis Lister Hawks), 1864–1947 , The ...

* * * * * *

Shanghai steps up efforts to save local language

Archive

. '' CNN''. March 31, 2011.

Shanghainese audio lesson series

Audio lessons with accompanying dialogue and vocabulary study tools

Resources on Shanghai dialect including a Web site (in Japanese) that gives common phrases with sound files

Wu AssociationIAPSD , International Association for Preservation of the Shanghainese Dialect

*Recordings of Shanghainese are available through

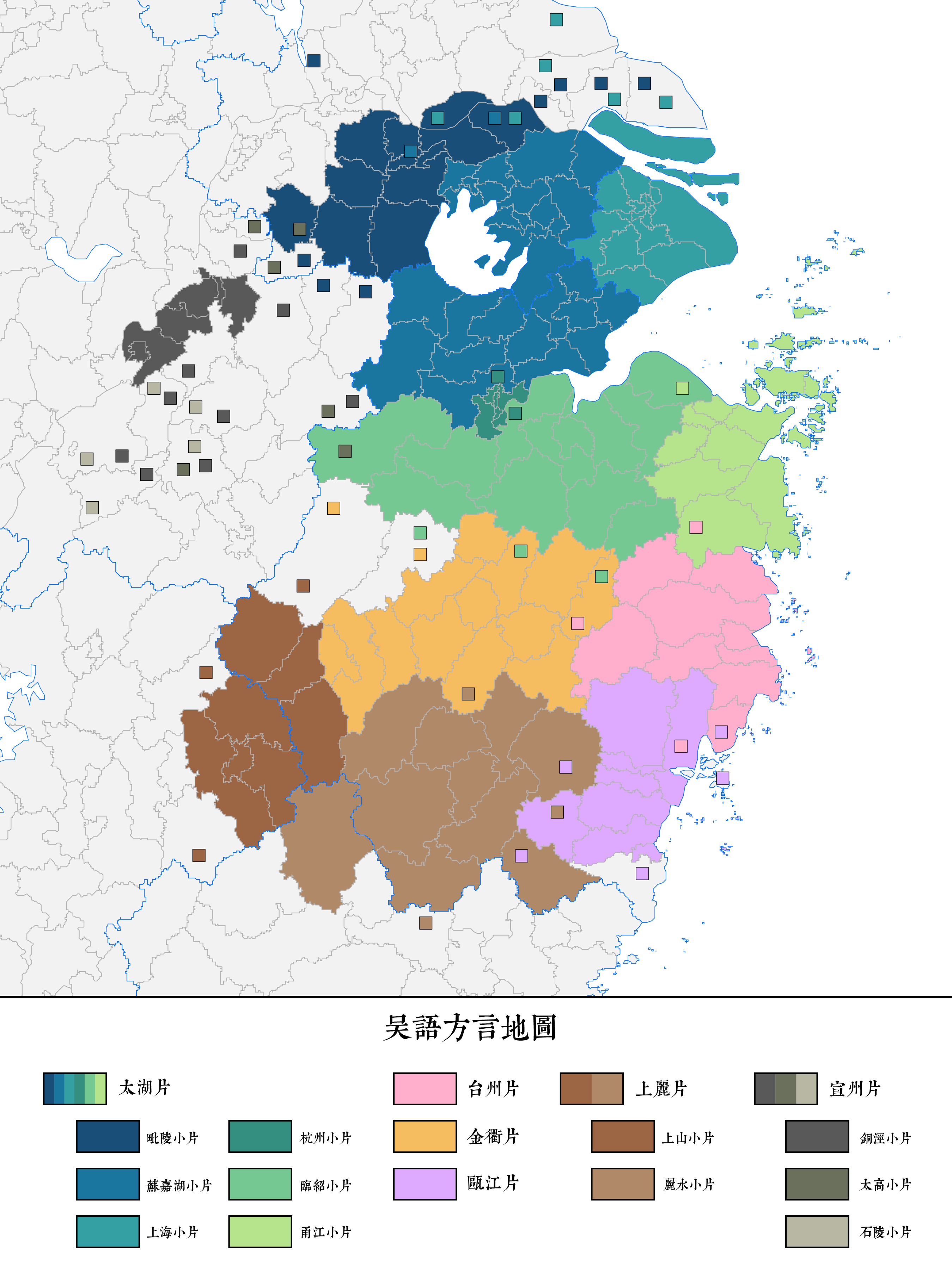

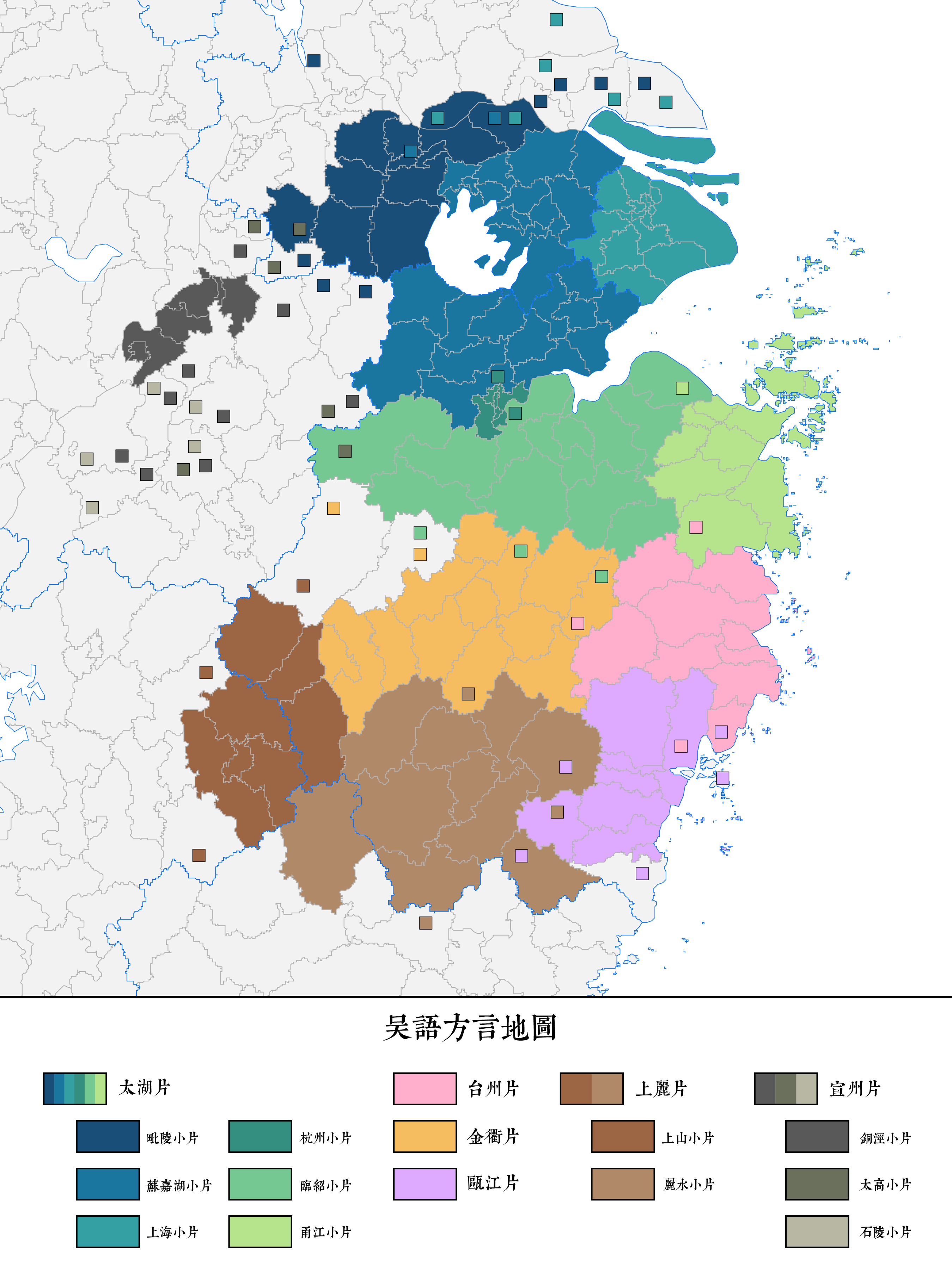

Wu Chinese

The Wu languages (; Wu romanization and IPA: ''wu6 gniu6'' [] ( Shanghainese), ''ng2 gniu6'' [] (Suzhounese), Mandarin pinyin and IPA: ''Wúyǔ'' []) is a major group of Sinitic languages spoken primarily in Shanghai, Zhejiang, Zhejiang Provin ...

spoken in the central districts

The Central Stags, formerly known as Central Districts, are a first-class cricket team based in central New Zealand. They are the men's representative side of the Central Districts Cricket Association. They compete in the Plunket Shield firs ...

of the City of Shanghai and its surrounding areas. It is classified as part of the Sino-Tibetan language family

Sino-Tibetan, also cited as Trans-Himalayan in a few sources, is a family of more than 400 languages, second only to Indo-European in number of native speakers. The vast majority of these are the 1.3 billion native speakers of Chinese languages. ...

. Shanghainese, like the rest of the Wu language group, is mutually unintelligible

In linguistics, mutual intelligibility is a relationship between languages or dialects in which speakers of different but related varieties can readily understand each other without prior familiarity or special effort. It is sometimes used as ...

with other varieties of Chinese

Chinese, also known as Sinitic, is a branch of the Sino-Tibetan language family consisting of hundreds of local varieties, many of which are not mutually intelligible. Variation is particularly strong in the more mountainous southeast of mai ...

, such as Mandarin.

Shanghainese belongs a separate group of the Taihu Wu

Taihu Wu () or Northern Wu () is a Wu Chinese language spoken over much of southern part of Jiangsu province, including Suzhou, Wuxi, Changzhou, the southern part of Nantong, Jingjiang and Danyang; the municipality of Shanghai; and the northern p ...

subgroup. With nearly 14 million speakers, Shanghainese is also the largest single form of Wu Chinese. Since the late 19th century it has served as the lingua franca

A lingua franca (; ; for plurals see ), also known as a bridge language, common language, trade language, auxiliary language, vehicular language, or link language, is a language systematically used to make communication possible between groups ...

of the entire Yangtze River Delta

The Yangtze Delta or Yangtze River Delta (YRD, or simply ) is a triangle-shaped megalopolis generally comprising the Wu Chinese-speaking areas of Shanghai, southern Jiangsu and northern Zhejiang. The area lies in the heart of the Jiangnan re ...

region, but in recent decades its status has declined relative to Mandarin, which most Shanghainese speakers can also speak.

Like other Wu varieties, Shanghainese is rich in vowel

A vowel is a syllabic speech sound pronounced without any stricture in the vocal tract. Vowels are one of the two principal classes of speech sounds, the other being the consonant. Vowels vary in quality, in loudness and also in quantity (len ...

s and consonant

In articulatory phonetics, a consonant is a speech sound that is articulated with complete or partial closure of the vocal tract. Examples are and pronounced with the lips; and pronounced with the front of the tongue; and pronounced w ...

s, with around twenty unique vowel qualities, twelve of which are phonemic

In phonology and linguistics, a phoneme () is a unit of sound that can distinguish one word from another in a particular language.

For example, in most dialects of English, with the notable exception of the West Midlands and the north-west ...

. Similarly, Shanghainese also has voiced

Voice or voicing is a term used in phonetics and phonology to characterize speech sounds (usually consonants). Speech sounds can be described as either voiceless (otherwise known as ''unvoiced'') or voiced.

The term, however, is used to refer ...

obstruent

An obstruent () is a speech sound such as , , or that is formed by ''obstructing'' airflow. Obstruents contrast with sonorants, which have no such obstruction and so resonate. All obstruents are consonants, but sonorants include vowels as well as ...

initials

In a written or published work, an initial capital, also referred to as a drop capital or simply an initial cap, initial, initcapital, initcap or init or a drop cap or drop, is a letter at the beginning of a word, a chapter, or a paragraph that ...

, which is rare outside of Wu and Xiang varieties. Shanghainese also has a low number of tones compared to other languages in Southern China

South China () is a geographical and cultural region that covers the southernmost part of China. Its precise meaning varies with context. A notable feature of South China in comparison to the rest of China is that most of its citizens are not n ...

, and has a system of tone sandhi similar to Japanese pitch accent

is a feature of the Japanese language that distinguishes words by accenting particular morae in most Japanese dialects. The nature and location of the accent for a given word may vary between dialects. For instance, the word for "now" is in ...

.History

The speech of Shanghai had long been influenced by those spoken aroundJiaxing

Jiaxing (), alternately romanized as Kashing, is a prefecture-level city in northern Zhejiang province, China. Lying on the Grand Canal of China, Jiaxing borders Hangzhou to the southwest, Huzhou to the west, Shanghai to the northeast, and the p ...

, then Suzhou

Suzhou (; ; Suzhounese: ''sou¹ tseu¹'' , Mandarin: ), alternately romanized as Soochow, is a major city in southern Jiangsu province, East China. Suzhou is the largest city in Jiangsu, and a major economic center and focal point of trad ...

during the Qing Dynasty

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing,, was a Manchu-led imperial dynasty of China and the last orthodox dynasty in Chinese history. It emerged from the Later Jin dynasty founded by the Jianzhou Jurchens, a Tungusic-speak ...

. Suzhounese literature, Chuanqi, Tanci

Tanci is a narrative form of song in China that alternates between verse and prose.Wang, Lingzhen, p53 The literal name "plucking rhymes" refers to the singing of verse portions to a ''pipa''.Hu, Siao-chen, p539 A ''tanci'' is usually seven words ...

, and folk songs

Folk music is a music genre that includes traditional folk music and the contemporary genre that evolved from the former during the 20th-century folk revival. Some types of folk music may be called world music. Traditional folk music has be ...

all influenced early Shanghainese.

During the 1850's, the port of Shanghai was opened, and a large number of migrants entered the city. This led to many loanword

A loanword (also loan word or loan-word) is a word at least partly assimilated from one language (the donor language) into another language. This is in contrast to cognates, which are words in two or more languages that are similar because ...

s from both the West and the East, especially from Ningbonese, and like Cantonese

Cantonese ( zh, t=廣東話, s=广东话, first=t, cy=Gwóngdūng wá) is a language within the Chinese (Sinitic) branch of the Sino-Tibetan languages originating from the city of Guangzhou (historically known as Canton) and its surrounding a ...

in Hong Kong, English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ...

. In fact, "speakers of other Wu dialects traditionally treat the Shanghai vernacular somewhat contemptuously as a mixture of Suzhou and Ningbo dialects." This has led to Shanghainese becoming one of the fastest-developing languages of the Wu Chinese subgroup, undergoing rapid changes and quickly replacing Suzhounese

Suzhounese (; Suzhounese: ''sou1 tseu1 ghe2 gho6'' [] ), also known as the Suzhou dialect, is the Varieties of Chinese, variety of Chinese traditionally spoken in the city of Suzhou in Jiangsu, Jiangsu Province, China. Suzhounese is a varie ...

as the prestige dialect

Prestige refers to a good reputation or high esteem; in earlier usage, ''prestige'' meant "showiness". (19th c.)

Prestige may also refer to:

Arts, entertainment and media Films

* ''Prestige'' (film), a 1932 American film directed by Tay Garnet ...

of the Yangtze River Delta

The Yangtze Delta or Yangtze River Delta (YRD, or simply ) is a triangle-shaped megalopolis generally comprising the Wu Chinese-speaking areas of Shanghai, southern Jiangsu and northern Zhejiang. The area lies in the heart of the Jiangnan re ...

region. It underwent sustained growth that reached a peak in the 1930s during the Republican era Republican Era can refer to:

* Minguo calendar, the official era of the Republic of China

It may also refer to any era in a country's history when it was governed as a republic or by a Republican Party. In particular, it may refer to:

* Roman Rep ...

, when migrants arrived in Shanghai and immersed themselves in the local tongue. Migrants from Shanghai also brought Shanghainese to many overseas Chinese communities. As of 2016, 83.4 thousand people in Hong Kong

Hong Kong ( (US) or (UK); , ), officially the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China (abbr. Hong Kong SAR or HKSAR), is a List of cities in China, city and Special administrative regions of China, special ...

are still able to speak Shanghainese. Shanghainese is sometimes viewed as a tool to discriminate against immigrants. Migrants who move from other Chinese cities to Shanghai have little ability to speak Shanghainese. Among the migrant people, some believe Shanghainese represents the superiority of native Shanghainese people. Some also believe that native residents intentionally speak Shanghainese in some places to discriminate against the immigrant population to transfer their anger to migrant workers, who take over their homeland and take advantage of housing, education, medical, and job resources.

After the People's Republic of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

's government imposed and promoted Standard Chinese

Standard Chinese ()—in linguistics Standard Northern Mandarin or Standard Beijing Mandarin, in common speech simply Mandarin, better qualified as Standard Mandarin, Modern Standard Mandarin or Standard Mandarin Chinese—is a modern standa ...

as the official language of all of China, Shanghainese has started its decline. During the Chinese economic reform

The Chinese economic reform or reform and opening-up (), known in the West as the opening of China, is the program of economic reforms termed " Socialism with Chinese characteristics" and " socialist market economy" in the People's Republic of ...

of 1978, Shanghainese has once again took in a large number of migrants. Due to the prominence of Standard Mandarin, learning Shanghainese was no longer necessary for migrants. However, Shanghainese remained a vital part of the city's culture and retained its prestige status within the local population. In the 1990s, it was still common for local radio and television broadcasts to be in Shanghainese. For example, in 1995, the TV series ''Sinful Debt

''Sinful Debt'' is a 1995 Chinese television drama directed by Huang Shuqin and produced by Shanghai Television. It was written by Ye Xin, based on his 1992 novel '' Educated Youth''. The series follows five innocent-eyed teens (all portrayed by f ...

'' featured extensive Shanghainese dialogue; when it was broadcast outside Shanghai (mainly in adjacent Wu-speaking areas) Mandarin subtitles were added. The Shanghainese TV series ''Lao Niang Jiu'' (, "Old Uncle") was broadcast from 1995 to 2007 and was popular among Shanghainese residents. Shanghainese programming has since slowly declined amid regionalist-localist accusations. From 1992 onward, Shanghainese use was discouraged in schools, and many children native to Shanghai can no longer speak Shanghainese. In addition, Shanghai's emergence as a cosmopolitan global city consolidated the status of Mandarin as the standard language of business and services, at the expense of the local language.

Since 2005, movements have emerged to protect Shanghainese. At municipal legislative discussions in 2005, former Shanghai opera

Shanghai opera (), formerly known as Shenqu (), is a variety of Chinese opera from Shanghai typically sung in Shanghainese. It is unique in Chinese opera in that virtually all dramas in its repertoire today are set in the modern era (20th and 21 ...

actress Ma Lili moved to "protect" the language, stating that she was one of the few remaining Shanghai opera actresses who still retained authentic classic Shanghainese pronunciation in their performances. Shanghai's former party boss Chen Liangyu, a native Shanghainese himself, reportedly supported her proposal.Shanghainese has been reintegrated into pre-kindergarten education, with education of native folk songs and rhymes, as well as a Shanghainese-only day on Fridays in the ''Modern Baby Kindergarten''. Professor Qian Nairong

Qian Nairong (Shanghainese: ; born 1945 in Shanghai) is a Chinese linguist. He received a master's degree in Chinese from Fudan University in 1981. He is a professor and the head of the Chinese Department at Shanghai University. He is a research ...

is working on efforts to save the language. In response to criticism, Qian reminds people that Shanghainese was once fashionable, saying, "the popularization of Mandarin doesn't equal the ban of dialects. It doesn't make Mandarin a more civilized language either. Promoting dialects is not a narrow-minded localism, as it has been labeled by some netizens". Professor Qian has also urged for Shanghainese to be taught in other sectors of education, due to kindergarten and university courses being insufficient.

During the 2010's, many achievements have been made to preserve Shanghainese. In 2011, Hu Baotan wrote ''Longtang'' (, " Longtang"), the first ever Shanghainese novel. In June 2012, a new television program airing in Shanghainese was created. In 2013, buses in Shanghai started using Shanghainese broadcasts. In 2017, Apple

An apple is an edible fruit produced by an apple tree (''Malus domestica''). Apple trees are cultivated worldwide and are the most widely grown species in the genus '' Malus''. The tree originated in Central Asia, where its wild ancest ...

's iOS 11

iOS 11 is the iOS version history, eleventh major release of the iOS mobile operating system developed by Apple Inc., being the successor to iOS 10. It was announced at the company's Apple Worldwide Developers Conference, Worldwide Developers C ...

introduced Siri

Siri ( ) is a virtual assistant that is part of Apple Inc.'s iOS, iPadOS, watchOS, macOS, tvOS, and audioOS operating systems. It uses voice queries, gesture based control, focus-tracking and a natural-language user interface to answer qu ...

in Shanghainese, being only the third Sinitic language to be supported, after Standard Mandarin and Cantonese. In 2018, the Japanese-Chinese animated anthology drama film ''Flavors of Youth

''Flavors of Youth'' ( ja, 詩季織々, shikioriori, lit. "From Season to Season"; zh, s=肆式青春, t=肆式青春, p=sì shì qīng chūn, Cantonese Jyutping: ''sei³ sik¹ cing¹ ceon¹'', Shanghainese Wugniu: ''sy⁵ seq⁷ tshen¹ chin ...

'' had a section set in Shanghai, with significant Shanghainese dialogue. In January 2019, singer Lin Bao

Lin or LIN may refer to:

People

*Lin (surname) (normally ), a Chinese surname

*Lin (surname) (normally 蔺), a Chinese surname

* Lin (''The King of Fighters''), Chinese assassin character

*Lin Chow Bang, character in Fat Pizza

Places

* Lin, Iran ...

released the first Shanghainese pop record ''Shanghai Yao'' (, "Shanghai Ballad"). In December 2021, the Shanghainese-language romantic comedy movie ''Myth of Love

''Myth of Love'' ( zh, 爱情神话) is a 2021 Chinese romance comedy, romantic comedy romance drama, drama film, written and directed by Shao Yihui, produced by Xu Zheng (actor), Xu Zheng, and starring Xu, Ma Yili, Wu Yue (actress), Wu Yue, , and ...

'' () was released. Its box office revenue was ¥260 million, and response was generally positive.

Today, around half the population of Shanghai can converse in Shanghainese, and a further quarter can understand it. Though the number of speakers has been declining, a large number of people want to preserve it.

Status

Due to the large number ofethnic groups of China

China's population consists of 56 ethnic groups, not including some ethnic groups from Taiwan.

The Han people are the largest ethnic group in mainland China. In 2010, 91.51% of the population were classified as Han (~1.2 billion). Besides the ...

, attempts to establish a common language have been attempted many times. Therefore, the language issue has always been an important part of Beijing's rule. Other than the government language-management efforts, the rate of rural-to-urban migration in China has also accelerated the shift to Standard Chinese

Standard Chinese ()—in linguistics Standard Northern Mandarin or Standard Beijing Mandarin, in common speech simply Mandarin, better qualified as Standard Mandarin, Modern Standard Mandarin or Standard Mandarin Chinese—is a modern standa ...

and the disappearance of native languages and dialects in the urban areas.

As more people moved into Shanghai, the economic center of China, Shanghainese has been threatened despite it originally being a strong topolect of Wu Chinese

The Wu languages (; Wu romanization and IPA: ''wu6 gniu6'' [] ( Shanghainese), ''ng2 gniu6'' [] (Suzhounese), Mandarin pinyin and IPA: ''Wúyǔ'' []) is a major group of Sinitic languages spoken primarily in Shanghai, Zhejiang, Zhejiang Provin ...

. According to the Shanghai Municipal Statistics Bureau, the population of Shanghai was estimated to be 24.28 million in 2019, of whom 14.5 million are permanent residents and 9.77 million are migrant residents. To have better communication with foreign residents and develop a top-level financial center among the world, the promotion of the official language, Standard Mandarin, became very important. Therefore, the Shanghai Municipal Government banned the use of Shanghainese in public places, schools, and work. Around half of the city's population is unaware of these policies.

A survey of students from the primary school in 2010 indicated that 52.3% of students believed Mandarin is easier than Shanghainese for communication, and 47.6% of the students choose to speak Mandarin because it is a mandatory language at school. Furthermore, 68.3% of the students are more willing to study Mandarin, but only 10.2% of the students are more willing to study Shanghainese. A survey in 2021 has shown that 15.22% of respondents under 18 would never use Shanghainese. The study also found that the percentage of people that would use Shanghainese with older family members has halved. The study also shows that around one third of people under the age of 30 can only understand Shanghainese, and 8.7% of respondents under 18 cannot even understand it. The number of people that are able to speak Shanghainese has also consistently decreased.

Much of the youth can no longer speak Shanghainese fluently because they had no chance to practice it at school. Also, they were unwilling to communicate with their parents in Shanghainese, which has accelerated its decline. The survey in 2010 indicated that 62.6% of primary school students use Mandarin as the first language at home, but only 17.3% of them use Shanghainese to communicate with their parents.

However, the same study from 2021 has shown that more than 90% of all year groups except 18-29 want to preserve Shanghainese. 87.06% of people have noted that the culture of Shanghai cannot live without its language, and around half of the respondents stated that a Shanghainese citizen should be able to speak Shanghainese. More than 85% of all respondents also believe that they help Shanghainese revitalization, and it would be useful to announce station names in Shanghainese on buses.

Classification

Shanghainese macroscopically is spoken in Shanghai and parts of eastern

Shanghainese macroscopically is spoken in Shanghai and parts of eastern Nantong

Nantong (; alternate names: Nan-t'ung, Nantung, Tongzhou, or Tungchow; Qihai dialect: ) is a prefecture-level city in southeastern Jiangsu province, China. Located on the northern bank of the Yangtze River, near the river mouth. Nantong is a vit ...

, and makes up the Shanghai subranch of the Northern Wu

Taihu Wu () or Northern Wu () is a Wu Chinese language spoken over much of southern part of Jiangsu province, including Suzhou, Wuxi, Changzhou, the southern part of Nantong, Jingjiang and Danyang, Jiangsu, Danyang; the municipality of Shanghai; a ...

family of Wu Chinese

The Wu languages (; Wu romanization and IPA: ''wu6 gniu6'' [] ( Shanghainese), ''ng2 gniu6'' [] (Suzhounese), Mandarin pinyin and IPA: ''Wúyǔ'' []) is a major group of Sinitic languages spoken primarily in Shanghai, Zhejiang, Zhejiang Provin ...

. Some linguists group Shanghainese with nearby varieties, such as Huzhounese and Suzhounese

Suzhounese (; Suzhounese: ''sou1 tseu1 ghe2 gho6'' [] ), also known as the Suzhou dialect, is the Varieties of Chinese, variety of Chinese traditionally spoken in the city of Suzhou in Jiangsu, Jiangsu Province, China. Suzhounese is a varie ...

, which has about 29%-30% lexical similarity

In linguistics, lexical similarity is a measure of the degree to which the word sets of two given languages are similar. A lexical similarity of 1 (or 100%) would mean a total overlap between vocabularies, whereas 0 means there are no common words. ...

with Standard Mandarin, into a branch known as Suhujia (), due to them sharing many phonological, lexical, and grammatical similarities. Newer varieties of Shanghainese, however, have been influenced by standard Chinese as well as Cantonese and other varieties, making the Shanghainese idiolects spoken by young people in the city different from that spoken by the older population. Also, the practice of inserting Mandarin into Shanghainese conversations is very common, at least for young people. Like most subdivisions of Chinese, it is easier for a local speaker to understand Mandarin than it is for a Mandarin speaker to understand the local language. It is also of note that Shanghainese, like other other Northern Wu languages, is not mutually intelligible with Southern Wu languages like Taizhounese and Wenzhounese

Wenzhounese (), also known as Oujiang (), Tong Au () or Au Nyü (), is the language spoken in Wenzhou, the southern prefecture of Zhejiang, China. Nicknamed the "Devil's Language" () for its complexity and difficulty, it is the most divergent div ...

.

Shanghainese as a branch of Northern Wu can be further subdivided. The details are as follows:

* Urban branch () – what “Shanghainese” tends to refer to. Occupies the city centre of Shanghai, generally on the west bank of the Huangpu River

The Huangpu (), formerly romanized as Whangpoo, is a river flowing north through Shanghai. The Bund and Lujiazui are located along the Huangpu River.

The Huangpu is the biggest river in central Shanghai, with the Suzhou Creek being its maj ...

. This can also be further divided into Old, Middle, and New Periods, as well as an emerging Newest Period.

The following are often collectively known as ''Bendihua'' (, Shanghainese: , Wugniu: ''pen-di ghe-gho'')

* Jiading branch () – spoken in the most of Jiading

Jiading is a suburban district of Shanghai. It had a population of 1,471,100 in 2010.

History

Historically, Jiading was a separate municipality/town, until, in 1958, becoming under the administration of Shanghai. In 1993, Jiading's designate ...

and Baoshan.

* Liantang branch () – spoken in the southwestern ends of Qingpu

Qingpu District, is a suburban district of Shanghai, Shanghai Municipality. Lake Dianshan is located in Qingpu.

The population of Qingpu was counted at 1,081,000 people in the 2010 Census. It has an area of .

Qingpu District is the western ...

.

* Chongming branch () – spoken in the islands of Hengsha, Changxing

() is a county of the prefecture-level city of Huzhou, in the northwest of Zhejiang province, China. Situated on the southwest shore of Lake Tai, it borders the provinces of Jiangsu to the north and Anhui to the west. It has a total area of an ...

and Chongming, as well as the eastern parts of Nantong

Nantong (; alternate names: Nan-t'ung, Nantung, Tongzhou, or Tungchow; Qihai dialect: ) is a prefecture-level city in southeastern Jiangsu province, China. Located on the northern bank of the Yangtze River, near the river mouth. Nantong is a vit ...

.

* Songjiang branch () – spoken in all other parts of Shanghai, which can be further divided into the following:

:* Pudong subbranch () – spoken in all parts of the east bank of the Huangpu River, taking up most of the Pudong

Pudong is a district of Shanghai located east of the Huangpu, the river which flows through central Shanghai. The name ''Pudong'' was originally applied to the Huangpu's east bank, directly across from the west bank or Puxi, the historic city ...

district.

:* Shanghai subbranch () – spoken in the rest of the periferal areas of the city center, namely southern Jiading and Baoshan, as well as northern Minhang

Minhang District is a suburban district of Shanghai with a land area of and population of 2,429,000 residents as of 2010. The original Minhang consist of present-day Jiangchuan Road Subdistrict (Former Minhang Town) and the eastern strip of Wu ...

.

:* Songjiang subbranch () – spoken in the rest of Shanghai. Named after the Songjiang Songjiang, from the Chinese for "Pine River" and formerly romanized as Sungkiang, usually refers to one of the following areas within the municipal limits of Shanghai:

* Songjiang Town (), the former principal town of the Shanghai area

* Songjia ...

district.

Phonology

Following conventions of Chinese syllable structure, Shanghainese syllables can be divided intoinitials

In a written or published work, an initial capital, also referred to as a drop capital or simply an initial cap, initial, initcapital, initcap or init or a drop cap or drop, is a letter at the beginning of a word, a chapter, or a paragraph that ...

and finals. The initial occupies the first part of the syllable. The final occupies the second part of the syllable and can be divided further into an optional medial and an obligatory rime

Rime may refer to:

*Rime ice, ice that forms when water droplets in fog freeze to the outer surfaces of objects, such as trees

Rime is also an alternative spelling of "rhyme" as a noun:

*Syllable rime, term used in the study of phonology in ling ...

(sometimes spelled ''rhyme''). Tone is also a feature of the syllable in Shanghainese. Syllabic tone, which is typical to the other Sinitic languages, has largely become verbal tone in Shanghainese.

Initials

The following is a list of all initials in Middle Period Shanghainese, as well as the Wugniu romanisation and example characters. Shanghainese has a set of tenuis,lenis

In linguistics, fortis and lenis ( and ; Latin for "strong" and "weak"), sometimes identified with tense and lax, are pronunciations of consonants with relatively greater and lesser energy, respectively. English has fortis consonants, such as the ...

and fortis plosive

In phonetics, a plosive, also known as an occlusive or simply a stop, is a pulmonic consonant in which the vocal tract is blocked so that all airflow ceases.

The occlusion may be made with the tongue tip or blade (, ), tongue body (, ), lip ...

s and affricate

An affricate is a consonant that begins as a stop and releases as a fricative, generally with the same place of articulation (most often coronal). It is often difficult to decide if a stop and fricative form a single phoneme or a consonant pai ...

s, as well as a set of voiceless

In linguistics, voicelessness is the property of sounds being pronounced without the larynx vibrating. Phonologically, it is a type of phonation, which contrasts with other states of the larynx, but some object that the word phonation implies ...

and voiced

Voice or voicing is a term used in phonetics and phonology to characterize speech sounds (usually consonants). Speech sounds can be described as either voiceless (otherwise known as ''unvoiced'') or voiced.

The term, however, is used to refer ...

fricative

A fricative is a consonant produced by forcing air through a narrow channel made by placing two articulators close together. These may be the lower lip against the upper teeth, in the case of ; the back of the tongue against the soft palate in ...

s. Alveolo-palatal

In phonetics, alveolo-palatal (or alveopalatal) consonants, sometimes synonymous with pre-palatal consonants, are intermediate in articulation between the coronal and dorsal consonants, or which have simultaneous alveolar and palatal artic ...

initials are also present in Shanghainese.

Voiced stops are phonetically voiceless with slack voice phonation in stressed, word initial position. This phonation (often referred to as murmur) also occurs in zero onset syllables, syllables beginning with fricatives

A fricative is a consonant produced by forcing air through a narrow channel made by placing two articulators close together. These may be the lower lip against the upper teeth, in the case of ; the back of the tongue against the soft palate in t ...

, and syllables beginning with sonorants

In phonetics and phonology, a sonorant or resonant is a speech sound that is produced with continuous, non-turbulent airflow in the vocal tract; these are the manners of articulation that are most often voiced in the world's languages. Vowels are ...

. These consonants are true voiced in intervocalic position. Sonorants are also suggested to be glottalised in dark tones (ie. tones 1, 5, 7).

Finals

Being a Wu language, Shanghainese has a large array of vowel sounds. The following is a list of all possible finals in Middle Period Shanghainese, as well as the Wugniu romanisation and example characters. The transcriptions used above are broad and the following points are of note when pertaining to actual pronunciation:Qian 2007. * is enunciated with any part of the tongue, and is therefore in free variation as . * is often rounded into . * The in and are often lowered to , whereas the in and are often lowered to . * is only pronounced as in front of labials and alveolars. whereas it is in front of glottal and alveolo-palatal initials. * High vowels in front of can undergo breaking. * can be merged into , resulting in one fewer rime. * Rimes with final is often simply realised as a shortened vowel nucleus when it is not utterance-final. * Lips are not significantly rounded in rounded vowels, and not significantly unrounded in unrounded ones. * are similar in pronunciation, differing slightly in lip rounding and height ( respectively). are also similar in pronunciation, differing slightly in vowel height ( respectively). * Medial is pronounced before rounded vowels. TheMiddle Chinese

Middle Chinese (formerly known as Ancient Chinese) or the Qieyun system (QYS) is the historical variety of Chinese recorded in the '' Qieyun'', a rime dictionary first published in 601 and followed by several revised and expanded editions. The ...

nasal

Nasal is an adjective referring to the nose, part of human or animal anatomy. It may also be shorthand for the following uses in combination:

* With reference to the human nose:

** Nasal administration, a method of pharmaceutical drug delivery

* ...

rimes are all merged in Shanghainese. Middle Chinese rimes have become glottal stops, .

Tones

Shanghainese has five phonetically distinguishable tones for single syllables said in isolation. These tones are illustrated below in Chao tone numbers. In terms of Middle Chinese tone designations, the dark tone category has three tones (dark rising and dark departing tones have merged into one tone), while the light category has two tones (the light level, rising and departing tones have merged into one tone). Numbers in this table are those used by the Wugniu romanisation scheme. The conditioning factors which led to the ''yin–yang'' (light-dark) split still exist in Shanghainese, as they do in most other Wu lects: light tones are only found with voiced initials, namely , while the light tones are only found with voiceless initials. The checked tones are shorter, and describe those rimes which end in a glottal stop . That is, both the ''yin–yang'' distinction and the checked tones areallophonic

In phonology, an allophone (; from the Greek , , 'other' and , , 'voice, sound') is a set of multiple possible spoken soundsor ''phones''or signs used to pronounce a single phoneme in a particular language. For example, in English, (as in ' ...

(dependent on syllabic structure). With this analysis, Shanghainese has only a two-way phonemic tone contrast, falling ''vs'' rising, and then only in open syllables with voiceless initials. Therefore, many romanisations of Shanghainese opt to only mark the dark level tone, usually with a diacritic such as an acute accent

The acute accent (), , is a diacritic used in many modern written languages with alphabets based on the Latin, Cyrillic, and Greek scripts. For the most commonly encountered uses of the accent in the Latin and Greek alphabets, precomposed ...

or grave accent

The grave accent () ( or ) is a diacritical mark used to varying degrees in French, Dutch, Portuguese, Italian and many other western European languages, as well as for a few unusual uses in English. It is also used in other languages usin ...

.

Tone sandhi

Tone sandhi

Tone sandhi is a phonological change occurring in tonal languages, in which the tones assigned to individual words or morphemes change based on the pronunciation of adjacent words or morphemes.

It usually simplifies a bidirectional tone into a ...

is a process whereby adjacent tones undergo dramatic alteration in connected speech. Similar to other Northern Wu dialects, Shanghainese is characterized by two forms of tone sandhi: a word tone sandhi and a phrasal tone sandhi.

Word tone sandhi in Shanghainese can be described as left-prominent and is characterized by a dominance of the first syllable over the contour of the entire tone domain. As a result, the underlying tones of syllables other than the leftmost syllable, have no effect on the tone contour of the domain. The pattern is generally described as tone spreading (1, 5, 6, 7) or tone shifting (8, except for 4-syllable compounds, which can undergo spreading or shifting). The table below illustrates possible tone combinations.

As an example, in isolation, the two syllables of the word (''China'') are pronounced with a dark level tone (''tsón'') and dark checked tone (''koq''): and . However, when pronounced in combination, the dark level tone of (''tsón'') spreads over the compound resulting in the following pattern . Similarly, the syllables in a common expression for (''zeq-sé-ti'', "foolish") have the following underlying phonemic and tonal representations: (''zeq''), (''sé''), and (''ti''). However, the syllables in combination exhibit the light checked shifting pattern where the first-syllable light checked tone shifts to the last syllable in the domain: .

Phrasal tone sandhi in Shanghainese can be described as right-prominent and is characterized by a right syllable retaining its underlying tone and a left syllable receiving a mid-level tone based on the underlying tone's register. The table below indicates possible left syllable tones in right-prominent compounds.

For instance, when combined, (''ma'', , "to buy") and (''cieu'', , "wine") become ("to buy wine").

Sometimes meaning can change based on whether left-prominent or right-prominent sandhi is used. For example, (''tshau'', , "to fry") and (''mi'', , "noodle") when pronounced (i.e., with left-prominent sandhi) means "fried noodles". When pronounced (i.e., with right-prominent sandhi), it means "to fry noodles".

Vocabulary

''Note: Chinese characters for Shanghainese are not standardized and those chosen are those recommended in . IPA transcription is for the Middle Period of modern Shanghainese (), pronunciation of those between 20 and 60 years old.'' Due to the large number of migrants into Shanghai, its lexicon is less noticably Wu, though it still retains many defining features. However, many of these now lost features can be found in lects spoken in suburban Shanghai. Its basic negator is (''veq''), which according to some linguists, is sufficient ground to classify it as Wu. Shanghainese also has a multitude of loan words from European languages, due to Shanghai’s status as a major port in China. Most of these terms come from English, though there are some from other languages such as French. Some terms, such as , have even entered mainstream and other Sinitic languages, such asSichuanese Sichuanese, Szechuanese or Szechwanese may refer to something of, from, or related to the Chinese province and region of Sichuan (Szechwan/Szechuan) (historically and culturally including Chongqing), especially:

* Sichuanese people, a subgroup of th ...

.

Common words and phrases

Literary and vernacular pronunciations

Like other Sinitic languages, Shanghainese exhibits a difference between expected vernacular pronunciations, and literary pronunciations taken from the Standard Mandarin of the time, be it Nanjingnese,Hangzhounese

The Hangzhou dialect (, ''Rhangzei Rhwa'') is spoken in the city of Hangzhou, China and its immediate suburbs, but excluding areas further away from Hangzhou such as Xiāoshān (蕭山) and Yúháng (余杭) (both originally county-level citi ...

, or Beijingnese.

These readings must be distinguished in vocabulary. Take for instance the following.

Some terms mix the two pronunciation types, such as (“university”), where is literary (da) and is colloquial (ghoq).

Generational difference

Shanghainese has undergone several dramatic changes throughout the ages, and can thus be classified into several generational categories. * Οld Period Shanghainese () is spoken mostly by the elderly. * Middle Period Shanghainese () is spoken by the majority of the population, and acts as the standard of Shanghainese. The Shanghai People's Radio Station, for instance, uses this as a standard of Shanghainese. * New Period Shanghainese () is spoken by the youth, and is heavily influenced by Standard Mandarin. As time goes on, the number of finals generally shrinks, whereas one extra initial, (''zh''), is added in Middle Period. The total number of phonemic tones has also generally declined.Old Period

The Old Period refers to Shanghainese spoken before the 1930's. The following is a table of Old Period initials, as of the year 1915. Though these seem generally similar, there are some important distinctions. * Old Period Shanghainese distinguishes historical si- and ki- (). For instance, ≠ , whereas they are both after the 1940's. * The addition of the initial originates from Old Period syllables pronounced as , such as . It emerged at approximately the same time. * Before the 1940's, the initial could be realised as approximants and . * Before the 1920's, some terms with the contemporary initial had a initial. Some changes listed here happened during the Early Middle Period, but would be atypical of common Middle Period speech. In terms of finals, there are also several important evolutions. * Old Period splits contemporary into and . For instance, ≠ . These sounds were merged after the 1940's. * The exact nature of the final has changed among time. The following is a chart of its evolution, up to the Middle Period. : * The finals of and were different - and respectively – which were merged in around the 1920's to 1930's. The finals of and used to be one and the same, , which split after the 1940's. * Contermporary was realised as . * Contemporary were split into and . For instance, ≠ . * The finals of , and were different. The first two were first seen merged during the early 1900's whereas the latter merged as well during the 1920's. * Old Period also had an extra rime. This will merge into rime during the latter half of the 20th century. * Contemporary , , , and are split as and , and , and , and and respectively. A dictinoary from the 1850's shows that Shanghainese appeared to have 8 tones. These will merge into 6 during the 1900's, and then finally settle at 5. The tone sandhi chains are also different, with Old Period having a system where all syllables had phonemic tone, whereas all syllables except the first in a left-prominent tone sandhi chain lose phonemic tone in contemporary Shanghainese. Old Period also differs with the other two in terms of vocabulary and grammar. Take the following examples:New Period

The New Period starts at around the 1990's, and is primarily used by the youth. It is defined by its heavy "Mandarinisms". Phonologically, its posesses many striking features which mark it different to New Period. The following are often observed: * The and finals merge into and respectively. For instance, ''yoe'' = ''yu'', and ''kuoe'' = ''koe''. * The distinction between and nuclei is lost, for instance ''taon'' = ''tan''. They are also sometimes pronounced as rather than being truenasal vowel

A nasal vowel is a vowel that is produced with a lowering of the soft palate (or velum) so that the air flow escapes through the nose and the mouth simultaneously, as in the French vowel or Amoy []. By contrast, oral vowels are produced with ...

s.

* The distinction between and nuclei is lost, merging into , for instance ''meq'' = ''maq''. The final, however, gets merged into , for instance, ''jiaq'' = ''jiq''.

* The and finals are sometimes realised as and respectively.

* The vowel is pronounced like , more similar to Standard Mandarin.

''Note that in the above section, all instances of the Wugniu romanisation transcribes for the expected Middle Period pronunciation.''

In terms of grammar, the word order is also sometimes changed to be more similar to Mandarin. Take for example the following sentences, which all mean "come over to my place and play when you have time!":

Newest Period

Due to the decline of Shanghainese, and the increasing userbase of Standard Mandarin, Shanghainese has entered an emerging "Newest Period". The exact phonology generally varies from person to person. The following is a non-exhaustive list of phonological changes seen in Newest Period Shanghainese, and are heavily proscribed. Initials: * Voicing is lost in historical rising and departing tone words: → . * The and some initials are merged into the null, especially when pronouncing Written Standard Chinese (): → . * The initial is almost completely lost. They are distributed either to , such as , or , such as . * Some words with and initials change to the , primarily in literary pronunciations: → . * The alveolo-palatal series approach . * The voiced initials merge with their unvoiced counterparts: → . :* However, gets merged into the null initial: → . Finals: * Some words with the final create a new : → . * Some words with the final merge into the final: → . * The final splits into , and : ≠ ≠ . * Some words with the final gets pronounced : → * The final gets pronounced as . * The final gets pronounced as . * The distinction between and sometimes gets blurred: → , → . * The syllable merges into the syllable: = * The and finals merge: = * The syllabic nasals, and , are lost. Tones: * The two checked tones merge into the 55 contour. * Some light departing words becoming dark rising: → . * 4 or 5 syllable sandhi chains break into shorter 2 or 3 character chains.Grammar

Like otherSinitic languages

The Sinitic languages (漢語族/汉语族), often synonymous with "Chinese languages", are a language group, group of East Asian analytic languages that constitute the major branch of the Sino-Tibetan languages, Sino-Tibetan language family. ...

, Shanghainese is an isolating language

An isolating language is a type of language with a morpheme per word ratio close to one, and with no inflectional morphology whatsoever. In the extreme case, each word contains a single morpheme. Examples of widely spoken isolating language ...

that lacks marking for tense, person, case, number or gender. Similarly, there is no distinction for tense or person in verbs, with word order and particles generally expressing these grammatical characteristics. There are, however, three important derivational processes in Shanghainese.Zhu 2006, pp.53. However, some analyses do suggest that one can analyse Shanghainese to have tenses.

Although formal inflection

In linguistic morphology, inflection (or inflexion) is a process of word formation in which a word is modified to express different grammatical categories such as tense, case, voice, aspect, person, number, gender, mood, animacy, and ...

is very rare in all varieties of Chinese, there does exist in Shanghainese a morpho-phonological tone sandhi

Tone sandhi is a phonological change occurring in tonal languages, in which the tones assigned to individual words or morphemes change based on the pronunciation of adjacent words or morphemes.

It usually simplifies a bidirectional tone into a ...

that Zhu (2006) identifies as a form of inflection since it forms new words out of pre-existing phrases.Zhu 2006, pp.54. This type of inflection is a distinguishing characteristic of all Northern Wu dialects.

Affixation, generally (but not always) taking the form of suffixes, occurs rather frequently in Shanghainese, enough so that this feature contrasts even with other Wu varieties, although the line between suffix and particle is somewhat nebulous. Most affixation applies to adjectives. In the example below, the term (''deu-sy'') can be used to change an adjective to a noun.

::

Words can be reduplicated

In linguistics, reduplication is a morphological process in which the root or stem of a word (or part of it) or even the whole word is repeated exactly or with a slight change.

The classic observation on the semantics of reduplication is Edwar ...

in order to express various differences in meaning. Nouns, for example, can be reduplicated to express collective or diminutive

A diminutive is a root word that has been modified to convey a slighter degree of its root meaning, either to convey the smallness of the object or quality named, or to convey a sense of intimacy or endearment. A ( abbreviated ) is a word-form ...

forms; adjectives so as to intensify or emphasize the associated description; and verbs in order to soften the degree of action. Below is an example of noun reduplication resulting in semantic alteration.

::

Word compounding is also very common in Shanghainese, a fact observed as far back as Edkins (1868), and is the most productive method of creating new words. Many recent borrowings in Shanghainese originating from European languages are di- or polysyllabic.

Word order

Shanghainese adheres generally to SVO word order. The placement of objects in Wu dialects is somewhat variable, with Southern Wu varieties positioning the direct object before the indirect object, and Northern varieties (especially in the speech of younger people) favoring the indirect object before the direct object. Owing to Mandarin influence, Shanghainese usually follows the latter model. Older speakers of Shanghainese tend to place adverbs after the verb, but younger people, again under heavy influence from Mandarin, favor pre-verbal placement of adverbs.Pan et al 1991, pp.271. The third person singular pronoun (''yi'') (he/she/it) or the derived phrase (''yi kaon'') ("he says") can appear at the end of a sentence. This construction, which appears to be unique to Shanghainese, is commonly employed to project the speaker's differing expectation relative to the content of the phrase. ::Nouns

Except for the limited derivational processes described above, Shanghainese nouns are isolating. There is no inflection for case or number, nor is there any overt gender marking. Although Shanghainese does lack overtgrammatical number

In linguistics, grammatical number is a grammatical category of nouns, pronouns, adjectives and verb agreement that expresses count distinctions (such as "one", "two" or "three or more"). English and other languages present number categories of ...

, the plural marker (''la''), when suffixed to a human denoting noun, can indicate a collective meaning.Zhu 2006, pp.59.

::

There are no articles in Shanghainese, and thus, no marking for definiteness

In linguistics, definiteness is a semantic feature of noun phrases, distinguishing between referents or senses that are identifiable in a given context (definite noun phrases) and those which are not (indefinite noun phrases). The prototypical ...

or indefiniteness of nouns. Certain determiners (a demonstrative pronoun or numeral classifier, for instance) can imply definite or indefinite qualities, as can word order. A noun absent any sort of determiner in the subject position is definite, whereas it is indefinite in the object position.

::

::

Classifiers

Shanghainese boasts numerous classifiers (also sometimes known as "counters" or "measure words"). Most classifiers in Shanghainese are used with nouns, although a small number are used with verbs.Zhu 2006, pp.71. Some classifiers are based on standard measurements or containers. Classifiers can be paired with a preceding determiner (often a numeral) to form a compound that further specifies the meaning of the noun it modifies. :: Classifiers can be reduplicated to mean "all" or "every", as in: ::Verbs

Shanghainese verbs areanalytic

Generally speaking, analytic (from el, ἀναλυτικός, ''analytikos'') refers to the "having the ability to analyze" or "division into elements or principles".

Analytic or analytical can also have the following meanings:

Chemistry

* ...

and as such do not undergo any sort of conjugation

Conjugation or conjugate may refer to:

Linguistics

*Grammatical conjugation, the modification of a verb from its basic form

* Emotive conjugation or Russell's conjugation, the use of loaded language

Mathematics

*Complex conjugation, the change ...

to express tense or person.Zhu 2006, pp.82. However, the language does have a richly developed aspect

Aspect or Aspects may refer to:

Entertainment

* ''Aspect magazine'', a biannual DVD magazine showcasing new media art

* Aspect Co., a Japanese video game company

* Aspects (band), a hip hop group from Bristol, England

* ''Aspects'' (Benny Carter ...

system, expressed using various particles. This system has been argued to be a tense system.Qian 2010.

Aspect

Some disagreement exists as to how many formal aspect categories exist in Shanghainese, and a variety of different particles can express the same aspect, with individual usage often reflecting generational divisions. Some linguists identify as few as four or six, and others up to twelve specific aspects.Zhu 2006, pp.81. Zhu (2006) identifies six relatively uncontroversial aspects in Shanghainese. Progressive aspect expresses a continuous action. It is indicated by the particles (''laq''), (''laq-laq'') or (''laq-he''), which occur pre-verbally. :: The resultative aspect expresses the result of an action which was begun before a specifically referenced timeframe, and is also indicated by (''laq''), (''laq-laq'') or (''laq-he''), except that these occur post-verbally. :: Perfective aspect can be marked by (''leq''), (''tsy''), (''hau'') or (''le'').Zhu 2006, pp.83. is seen as dated and younger speakers often use , likely through lenition and Mandarin influence. :: Zhu (2006) identifies a future aspect, indicated by the particle (''iau''). :: Qian (1997) identifies a separate immediate future aspect, marked post-verbally by (''khua''). :: Experiential aspect expresses the completion of an action before a specifically referenced timeframe, marked post-verbally by the particle (''ku'').Zhu 2006, pp.84. :: The durative aspect is marked post-verbally by (''gho-chi''), and expresses a continuous action. :: In some cases, it is possible to combine two aspect markers into a larger verb phrase. ::Mood and Voice

There is no overt marking for mood in Shanghainese, and Zhu (2006) goes so far as to suggest that the concept of grammatical mood does not exist in the language.Zhu 2006, pp.89. There are, however, several modal auxiliaries (many of which have multiple variants) that collectively express concepts of desire, conditionality, potentiality and ability. :: Shen (2016) argues for the existence of a type ofpassive voice

A passive voice construction is a grammatical voice construction that is found in many languages. In a clause with passive voice, the grammatical subject expresses the ''theme'' or '' patient'' of the main verb – that is, the person or thing ...

in Shanghainese, governed by the particle (''peq''). This construction is superficially similar to by-phrases in English, and only transitive verbs can occur in this form of passive.

::

Pronouns

Personal pronouns in Shanghainese do not distinguishgender

Gender is the range of characteristics pertaining to femininity and masculinity and differentiating between them. Depending on the context, this may include sex-based social structures (i.e. gender roles) and gender identity. Most culture ...

or case

Case or CASE may refer to:

Containers

* Case (goods), a package of related merchandise

* Cartridge case or casing, a firearm cartridge component

* Bookcase, a piece of furniture used to store books

* Briefcase or attaché case, a narrow box to ca ...

.Zhu 2006, pp.64. Owing to its isolating grammatical structure, Shanghainese is not a pro-drop language

A pro-drop language (from "pronoun-dropping") is a language where certain classes of pronouns may be omitted when they can be pragmatically or grammatically inferable. The precise conditions vary from language to language, and can be quite int ...

.

::

There is some degree of flexibility concerning pronoun usage in Shanghainese. Older varieties of Shanghainese featured a different 1st person plural (''ngu-gni''),Hashimoto 1971, pp.249. whereas younger speakers tend to use (''aq-laq''),Chao 1967, pp.99. which originates from Ningbonese. While Zhu (2006) asserts that there is no inclusive 1st person plural pronoun, Hashimoto (1971) disagrees, identifying as being inclusive. There are generational and geographical distinctions in the usage of plural pronoun forms, as well as differences of pronunciation in the 1st person singular.

Reflexive pronouns are formed by the addition of the particle (''zy-ka''), as in:

:

Possessive pronouns are formed via the pronominal suffix (''gheq''), for instance, (''ngu gheq''). This pronunciation is a glottalised lenition of the expected pronunciation, ''ku''.

Adjectives

Most basic Shanghainese adjectives are monosyllabic. Like other parts of speech, adjectives do not change to indicate number, gender or case. Adjectives can take semantic prefixes, which themselves can be reduplicated or repositioned as suffixes according to a complex system of derivation, in order to express degree of comparison or other changes in meaning. Thus: :: ''lan'' ("cold") :: ''pín-lan'' ("ice-cold"), where means ice :: ''pín-pín-lan'' ("cold as ice")Interrogatives

The particle (''vaq'') is used to transform ordinary declarative statements into yes/no questions. This is the most common way of forming questions in Shanghainese. ::Negation

Nouns and verbs can be negated by the verb (''m-meq''), “to not have”, whereas is the basic negator. ::Writing

Chinese character

Chinese characters () are logograms developed for the writing of Chinese. In addition, they have been adapted to write other East Asian languages, and remain a key component of the Japanese writing system where they are known as ''kanji' ...

s are often used to write Shanghainese. Though there is no formal standardisations, there are characters recommended for use, mostly based on dictionaries. However, Shanghainese is often informally written using Shanghainese or even Standard Mandarin near-homophone

A homophone () is a word that is pronounced the same (to varying extent) as another word but differs in meaning. A ''homophone'' may also differ in spelling. The two words may be spelled the same, for example ''rose'' (flower) and ''rose'' (pa ...

s. For instance "lemon" (), written in Standard Chinese, may be written (person-door; Pinyin: , Wugniu: ''gnin-men'') in Shanghainese; and "yellow" (, Wugniu: ''waon'') may be written (meaning king; Pinyin: , Wugniu: ''waon'') rather than the standard character for yellow.

Some of the time, nonstandard characters are used even when trying to use etymologically-correct characters, due to compatibility (such as ) or pronunciation shift (such as ).

Correct orthography according to

Mandarin-influenced orthography

Romanization

Romanization or romanisation, in linguistics, is the conversion of text from a different writing system to the Roman (Latin) script, or a system for doing so. Methods of romanization include transliteration, for representing written text, a ...

of Shanghainese was first developed by Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

English and American Christian missionaries

A Christian mission is an organized effort for the propagation of the Christian faith. Missions involve sending individuals and groups across boundaries, most commonly geographical boundaries, to carry on evangelism or other activities, such ...

in the 19th century, including Joseph Edkins. Usage of this romanization system was mainly confined to translated Bibles for use by native Shanghainese, or English–Shanghainese dictionaries, some of which also contained characters, for foreign missionaries to learn Shanghainese. A system of phonetic symbols similar to Chinese characters called "New Phonetic Character" were also developed by in the 19th century by American missionary Tarleton Perry Crawford

Tarleton Perry Crawford (May 8, 1821 – April 7, 1902) was a Baptist missionary to Shandong, China for 50 years with his wife.

Early life and education

Crawford was born in Warren County, Kentucky. He was the fourth son of John and Lucretia Cr ...

. Since the 21st century, online dictionaries such as the Wu MiniDict and Wugniu have introduced their own Romanization schemes. Nowadays, the MiniDict and Wugniu Romanizations are the most commonly used standardised ones.

Protestant missionaries in the 1800s created the Shanghainese Phonetic Symbols to write Shanghainese phonetically. The symbols are a syllabary similar to the Japanese ''kana

The term may refer to a number of syllabaries used to write Japanese phonological units, morae. Such syllabaries include (1) the original kana, or , which were Chinese characters ( kanji) used phonetically to transcribe Japanese, the most ...

'' system. The system has not been used and is only seen in a few historical books.

See also

*Shanghainese people

Shanghainese people (; Shanghainese: ''Zaanhe-nyin'' ) are people of Shanghai Hukou or people who have ancestral roots from Shanghai. Most Shanghainese are descended from immigrants from nearby provinces of Zhejiang and Jiangsu. According to ...

*Haipai

''Haipai'' (, Shanghainese: ''hepha'', ; literally "hangai style") refers to the avant-garde but unique "East Meets West" culture from Shanghai in the 20th and 21st centuries. It is a part of the culture of Shanghai.

Etymology

The term was coin ...

*Wu Chinese

The Wu languages (; Wu romanization and IPA: ''wu6 gniu6'' [] ( Shanghainese), ''ng2 gniu6'' [] (Suzhounese), Mandarin pinyin and IPA: ''Wúyǔ'' []) is a major group of Sinitic languages spoken primarily in Shanghai, Zhejiang, Zhejiang Provin ...

**Suzhounese

Suzhounese (; Suzhounese: ''sou1 tseu1 ghe2 gho6'' [] ), also known as the Suzhou dialect, is the Varieties of Chinese, variety of Chinese traditionally spoken in the city of Suzhou in Jiangsu, Jiangsu Province, China. Suzhounese is a varie ...

**Hangzhounese

The Hangzhou dialect (, ''Rhangzei Rhwa'') is spoken in the city of Hangzhou, China and its immediate suburbs, but excluding areas further away from Hangzhou such as Xiāoshān (蕭山) and Yúháng (余杭) (both originally county-level citi ...

** Ningbonese

*List of varieties of Chinese

The following is a list of Sinitic languages and their dialects. For a traditional dialectological overview, see also varieties of Chinese.

Classification

'Chinese' is a blanket term covering the many different varieties spoken across China. ...

* Chinatown, Flushing

References

Citations

Sources

* Lance Eccles, ''Shanghai dialect: an introduction to speaking the contemporary language''. Dunwoody Press, 1993. . 230 pp + cassette. (An introductory course in 29 units). * Xiaonong Zhu, ''A Grammar of Shanghai Wu''. LINCOM Studies in Asian Linguistics 66, LINCOM Europa, Munich, 2006. . 201+iv pp.Further reading

* * * * * * * * * *Pott, F. L. Hawks (Francis Lister Hawks), 1864–1947 , The ...

* * * * * *

Shanghai steps up efforts to save local language

Archive

. '' CNN''. March 31, 2011.

External links

Shanghainese audio lesson series

Audio lessons with accompanying dialogue and vocabulary study tools

Resources on Shanghai dialect including a Web site (in Japanese) that gives common phrases with sound files

Wu Association

*Recordings of Shanghainese are available through

Kaipuleohone Kaipuleohone is a digital ethnographic archive that houses audio and visual files, photographs, as well as hundreds of textual material such as notes, dictionaries, and transcriptions relating to small and endangered languages. The archive is stored ...

, including talking about entertainment and food, and words and sentences

{{DEFAULTSORT:Shanghainese Dialect

Wu Chinese

Culture in Shanghai

Languages of China

Languages of Taiwan

Languages of Hong Kong

Languages of the United States

Languages of Canada

City colloquials