Seán Treacy on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Seán Allis Treacy ( ga, Seán Ó Treasaigh; 14 February 1895 – 14 October 1920) was one of the leaders of the Third Tipperary Brigade of the

On 11 October 1920, Treacy and Breen were holed up in a safe house owned by a professor and IRA sympathiser named John Carolan – Fernside – in Drumcondra on the north side of Dublin city when it was raided by a police unit, led there by a

On 11 October 1920, Treacy and Breen were holed up in a safe house owned by a professor and IRA sympathiser named John Carolan – Fernside – in Drumcondra on the north side of Dublin city when it was raided by a police unit, led there by a

Treacy's death sent alarm bells through the upper echelons of the IRA leadership.

A commemorative plaque above the door of 94 Talbot Street, now the Wooden Whisk and directly across from Talbot House, commemorates the spot where Treacy died. His coffin arrived by train at Limerick Junction station and was accompanied to St Nicholas Church, Solohead by an immense crowd of Tipperary people. He was buried at Kilfeacle graveyard, where, despite a large presence of British military personnel, a volley of shots was fired over the grave.

Treacy is remembered each year on the anniversary of his death at a commemoration ceremony in Kilfeacle. At noon on the day of any All-Ireland Senior Hurling Final in which Tipperary participate, a ceremony of remembrance is held at the spot in Talbot Street, Dublin where he died, attended mainly by people from West Tipperary and Dublin people of Tipperary extraction. The most recent ceremonies were held at on Sunday 4 September 2016 and 18 August 2019, each attracting a large attendance of Tipperary folk en route to Croke Park. The ceremony usually consists of the reading of the

Treacy's death sent alarm bells through the upper echelons of the IRA leadership.

A commemorative plaque above the door of 94 Talbot Street, now the Wooden Whisk and directly across from Talbot House, commemorates the spot where Treacy died. His coffin arrived by train at Limerick Junction station and was accompanied to St Nicholas Church, Solohead by an immense crowd of Tipperary people. He was buried at Kilfeacle graveyard, where, despite a large presence of British military personnel, a volley of shots was fired over the grave.

Treacy is remembered each year on the anniversary of his death at a commemoration ceremony in Kilfeacle. At noon on the day of any All-Ireland Senior Hurling Final in which Tipperary participate, a ceremony of remembrance is held at the spot in Talbot Street, Dublin where he died, attended mainly by people from West Tipperary and Dublin people of Tipperary extraction. The most recent ceremonies were held at on Sunday 4 September 2016 and 18 August 2019, each attracting a large attendance of Tipperary folk en route to Croke Park. The ceremony usually consists of the reading of the Speech at Ballyporeen

, Tipperay by US President Ronald Reagan, June 3, 1984 The song most closely identified with him, ''Seán Treacy and Dan Breen'' commemorates his and Breen's escape from Fernside, and mourns his death:

at www.clarelibrary.ie

at republican-news.org

at homepage.eircom.net

* ttp://www.helensfamilytrees.com/treg03.htm Helen's Family Trees (Treacy page)*

Sean Treacy & Talbot street

{{DEFAULTSORT:Treacy, Sean 1895 births 1920 deaths Irish Republican Army (1919–1922) members Members of the Irish Republican Brotherhood People from County Tipperary Irish Republicans killed during the Irish War of Independence People killed in United Kingdom intelligence operations

IRA

Ira or IRA may refer to:

*Ira (name), a Hebrew, Sanskrit, Russian or Finnish language personal name

*Ira (surname), a rare Estonian and some other language family name

*Iran, UNDP code IRA

Law

*Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, US, on status of ...

during the Irish War of Independence

The Irish War of Independence () or Anglo-Irish War was a guerrilla war fought in Ireland from 1919 to 1921 between the Irish Republican Army (IRA, the army of the Irish Republic) and British forces: the British Army, along with the quasi-mil ...

. He was one of a small group whose actions initiated that conflict in 1919. He was killed in October 1920, on Talbot Street

Talbot Street (; ) is a city-centre street located on Dublin's Northside, near to Dublin Connolly railway station. It was laid out in the 1840s and a number of 19th-century buildings still survive. The Irish Life Mall is on the street.

Locati ...

in Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of th ...

, in a shootout with British troops during an aborted British Secret Service

The Secret Intelligence Service (SIS), commonly known as MI6 ( Military Intelligence, Section 6), is the foreign intelligence service of the United Kingdom, tasked mainly with the covert overseas collection and analysis of human intelligenc ...

surveillance operation.

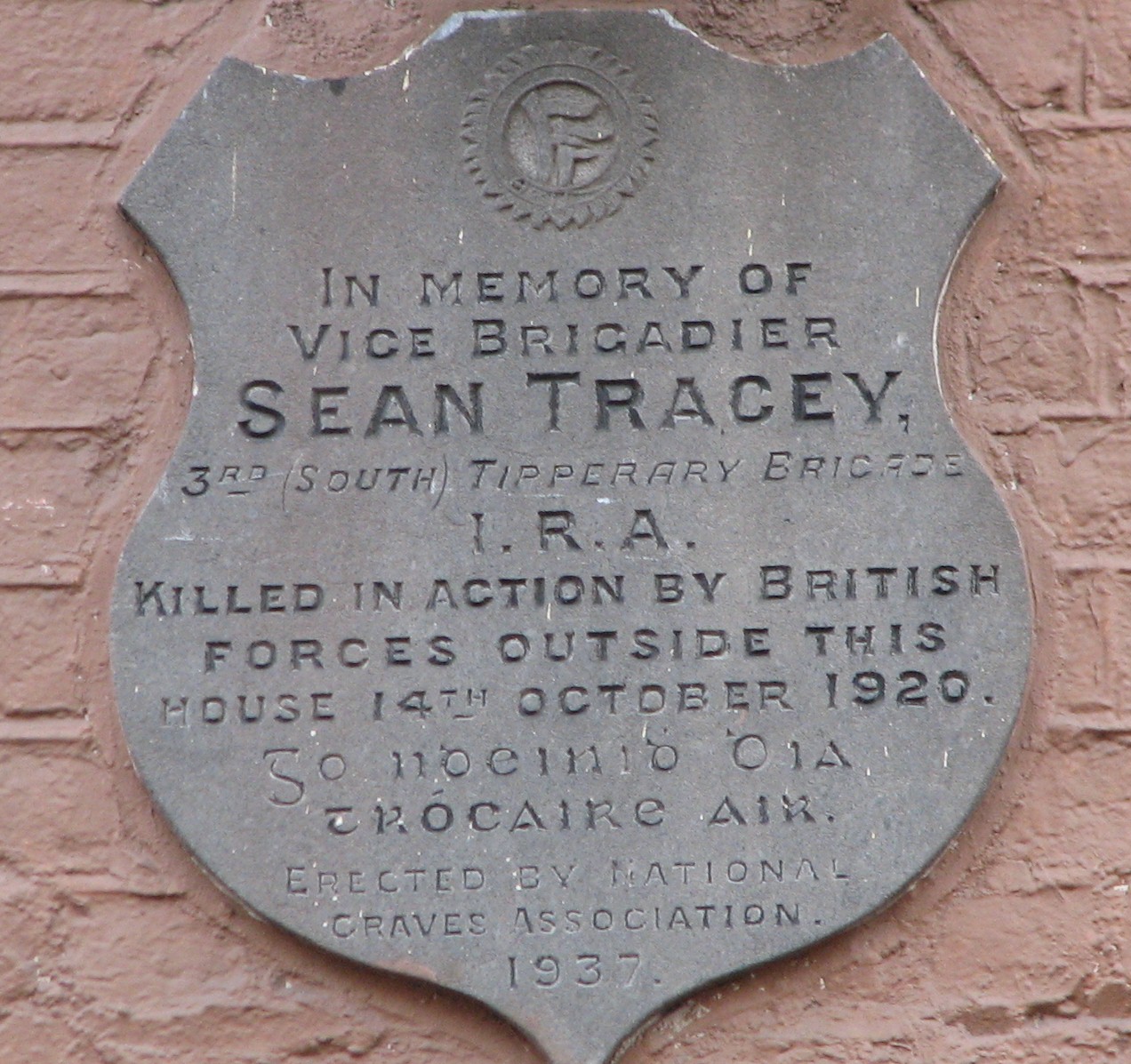

Although sometimes written as Tracey, as inscribed on the commemorative plaque in Talbot Street, or even as Tracy, his surname is more usually spelt 'Treacy'.

Early life and Irish Republicanism

Born as John Treacy, Seán Allis Treacy came from a small-farming background inSoloheadbeg

Sologhead beg or Solohead beg (; , IPA: �sˠʊləxoːdʲˈvʲaɡ is a townland and civil parish in County Tipperary, Ireland, lying northwest of Tipperary town.

History

In 968, Soloheadbeg was the location for the Battle of Sulcoit, where the ...

in west Tipperary

Tipperary is the name of:

Places

*County Tipperary, a county in Ireland

**North Tipperary, a former administrative county based in Nenagh

**South Tipperary, a former administrative county based in Clonmel

*Tipperary (town), County Tipperary's na ...

and grew up in Hollyford. He was the son of farmer Denis Treacy and Bridget Allis.

He left school aged 14 and worked as a farmer, also developing deep patriotic

Patriotism is the feeling of love, devotion, and sense of attachment to one's country. This attachment can be a combination of many different feelings, language relating to one's own homeland, including ethnic, cultural, political or histor ...

convictions; locally, he was seen as a promising farmer, calm, direct, ready to experiment with new methods, and intelligent. He was a member of the Gaelic League

(; historically known in English as the Gaelic League) is a social and cultural organisation which promotes the Irish language in Ireland and worldwide. The organisation was founded in 1893 with Douglas Hyde as its first president, when it emer ...

, and of the Irish Republican Brotherhood

The Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB; ) was a secret oath-bound fraternal organisation dedicated to the establishment of an "independent democratic republic" in Ireland between 1858 and 1924.McGee, p. 15. Its counterpart in the United States ...

(IRB) from 1911 and the Irish Volunteers

The Irish Volunteers ( ga, Óglaigh na hÉireann), sometimes called the Irish Volunteer Force or Irish Volunteer Army, was a military organisation established in 1913 by Irish nationalists and republicans. It was ostensibly formed in respons ...

from 1913.

He was picked up in the mass arrests in the aftermath of the Easter Rising

The Easter Rising ( ga, Éirí Amach na Cásca), also known as the Easter Rebellion, was an armed insurrection in Ireland during Easter Week in April 1916. The Rising was launched by Irish republicans against British rule in Ireland with the a ...

in 1916 and spent much of the following two years in prisons (Cork Prison

Cork Prison () is an Irish penal institution on Rathmore Road, Cork City, Ireland. It is a closed, medium security prison for males over 17 years of age, with capacity for 275 prisoners. It is immediately adjacent to Collins Barracks and near t ...

, Dundalk Gaol

Dundalk Gaol is a former gaol (prison) in Dundalk, County Louth, Ireland. The men's wing is now "The Oriel Centre", the women's wing is the Louth County Archive and the Governor's House now a Garda station.

__TOC__

History

Built in 1853 to ...

and Mountjoy Prison

Mountjoy Prison ( ga, Príosún Mhuinseo), founded as Mountjoy Gaol and nicknamed ''The Joy'', is a medium security men's prison located in Phibsborough in the centre of Dublin, Ireland.

The current prison Governor is Edward Mullins.

History

...

), where he joined the ongoing hunger strike

A hunger strike is a method of non-violent resistance in which participants fast as an act of political protest, or to provoke a feeling of guilt in others, usually with the objective to achieve a specific goal, such as a policy change. Most ...

(22 September 1917). Treacy was released from Mountjoy in June 1918.

From Dundalk

Dundalk ( ; ga, Dún Dealgan ), meaning "the fort of Dealgan", is the county town (the administrative centre) of County Louth, Ireland. The town is on the Castletown River, which flows into Dundalk Bay on the east coast of Ireland. It is h ...

jail in 1918 he wrote to his comrades in Tipperary: "Deport all in favour of the enemy out of the country. Deal sternly with those who try to resist. Maintain the strictest discipline, there must be no running to kiss mothers goodbye."

In 1918 he was appointed Vice Officer-Commanding of the 3rd Tipperary Brigade

The 3rd Tipperary Brigade () was one of the most active of approximately 80 such units that constituted the IRA during the Irish War of Independence. The brigade was based in southern Tipperary and conducted its activities mainly in mid-Munster ...

of the Irish Volunteers

The Irish Volunteers ( ga, Óglaigh na hÉireann), sometimes called the Irish Volunteer Force or Irish Volunteer Army, was a military organisation established in 1913 by Irish nationalists and republicans. It was ostensibly formed in respons ...

(which became the Irish Republican Army

The Irish Republican Army (IRA) is a name used by various paramilitary organisations in Ireland throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. Organisations by this name have been dedicated to irredentism through Irish republicanism, the belief tha ...

in 1919).

Soloheadbeg ambush

On 21 January 1919 Treacy andDan Breen

Daniel Breen (11 August 1894 – 27 December 1969) was a volunteer in the Irish Republican Army during the Irish War of Independence and the Irish Civil War. In later years he was a Fianna Fáil politician.

Background

Breen was born in Grang ...

, together with Seán Hogan

Seán Hogan (13 May 1901 – 24 December 1968) was one of the leaders of the 3rd Tipperary Brigade of the Irish Republican Army during the War of Independence.

Early life

Hogan was born on 13 May 1901, the elder child of Matthew Hogan of Green ...

, Séumas Robinson (known as the 'big four’) and five other volunteers, helped to ignite the conflict that was to become the Irish War of Independence. They ambushed and shot dead two members of the Royal Irish Constabulary

The Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC, ga, Constáblacht Ríoga na hÉireann; simply called the Irish Constabulary 1836–67) was the police force in Ireland from 1822 until 1922, when all of the country was part of the United Kingdom. A separate ...

(RIC) — Constables Patrick O'Connell and James McDonnell – during the Soloheadbeg ambush

The Soloheadbeg ambush took place on 21 January 1919, when members of the Irish Volunteers (or Irish Republican Army, IRA) ambushed Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) officers who were escorting a consignment of gelignite explosives at Soloheadbeg, ...

near Treacy's home. Treacy led the planning for the ambush and briefed the brigade's O/C Robinson on his return from prison in late 1918. Robinson supported the plans and agreed they wouldn't go to GHQ for permission to undertake the attack. The RIC men were guarding a transport of gelignite

Gelignite (), also known as blasting gelatin or simply "jelly", is an explosive material consisting of collodion-cotton (a type of nitrocellulose or guncotton) dissolved in either nitroglycerine or nitroglycol and mixed with wood pulp and saltpe ...

explosives. Some accounts say the Volunteers shot them dead when they refused to surrender and offered resistance; other accounts suggest that shooting them was the intent from the start.

Breen later recalled:

...we took the action deliberately, having thought over the matter and talked it over between us. Treacy had stated to me that the only way of starting a war was to kill someone, and we wanted to start a war, so we intended to kill some of the police, whom we looked upon as the foremost and most important branch of the enemy forces... The only regret that we had following the ambush was that there were only two policemen in it, instead of the six we had expected...

Knocklong train rescue

As a result of the action, South Tipperary was placed undermartial law

Martial law is the imposition of direct military control of normal civil functions or suspension of civil law by a government, especially in response to an emergency where civil forces are overwhelmed, or in an occupied territory.

Use

Marti ...

and declared a Special Military Area under the Defence of the Realm Act

The Defence of the Realm Act (DORA) was passed in the United Kingdom on 8 August 1914, four days after it entered the First World War and was added to as the war progressed. It gave the government wide-ranging powers during the war, such as the p ...

. After another member of the Soloheadbeg ambush party, Seán Hogan, who was just 17, was arrested on 12 May 1919, the three others (Treacy, Breen and Robinson) were joined by five men from the IRA's East Limerick Brigade to organise Hogan's rescue.

Hogan was brought to the train which was intended to bring him from Thurles

Thurles (; ''Durlas Éile'') is a town in County Tipperary, Ireland. It is located in the civil parish of the same name in the barony of Eliogarty and in the ecclesiastical parish of Thurles (Roman Catholic parish), Thurles. The cathedral ch ...

to Cork city

Cork ( , from , meaning 'marsh') is the second largest city in Ireland and third largest city by population on the island of Ireland. It is located in the south-west of Ireland, in the province of Munster. Following an extension to the city' ...

on 13 May 1919 — his escort grinning at him as he told the ticketmaster: "Give me three tickets to Cork — and two returns." As the train steamed across the Tipperary border and into Co Limerick

"Remember Limerick"

, image_map = Island_of_Ireland_location_map_Limerick.svg

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Ireland

, subdivision_type1 = Province

, subdivision_name1 = Munster

, subdivision_ ...

the IRA party, led by Treacy, boarded it at Knocklong

Knocklong () is a small village situated in County Limerick, Republic of Ireland, Ireland, located on the main Limerick to Mitchelstown to Cork (city), Cork road. The population was 256 at the 2016 census.

History

Knocklong was originally known ...

. A close-range struggle ensued on the train. Treacy and Breen were seriously wounded in the gunfight. Two RIC men died, but Hogan was rescued. His rescuers rushed him into the village of Knocklong, where a butcher's wife slammed down the shutters to hide them and her husband cut off Hogan's handcuffs using a cleaver.

Dublin and the Squad

A search for Treacy and others was mounted across Ireland. Treacy left Tipperary for Dublin to avoid capture.Michael Collins Michael Collins or Mike Collins most commonly refers to:

* Michael Collins (Irish leader) (1890–1922), Irish revolutionary leader, soldier, and politician

* Michael Collins (astronaut) (1930–2021), American astronaut, member of Apollo 11 and Ge ...

employed him on assassination operations with "the Squad". He was involved in the attempted killing of the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland

Lord Lieutenant of Ireland (), or more formally Lieutenant General and General Governor of Ireland, was the title of the chief governor of Ireland from the Williamite Wars of 1690 until the Partition of Ireland in 1922. This spanned the Kingdo ...

, Sir John French

Field Marshal John Denton Pinkstone French, 1st Earl of Ypres, (28 September 1852 – 22 May 1925), known as Sir John French from 1901 to 1916, and as The Viscount French between 1916 and 1922, was a senior British Army officer. Born in Kent t ...

, in December 1919.

In the summer of 1920, Treacy returned to Tipperary and organised several attacks on RIC barracks, notably at Hollyford, Kilmallock and Drangan, before again moving his base of operations to Dublin.

By spring 1920 the political police of the Crimes Special Branch and G-Division (Special Branch) of the Dublin Metropolitan Police

The Dublin Metropolitan Police (DMP) was the police force of Dublin, Ireland, from 1836 to 1925, when it was amalgamated into the new Garda Síochána.

History

19th century

The Dublin city police had been subject to major reforms in 1786 and ...

(DMP) had been effectively neutralised by IRA counterintelligence operatives under Collins. The British thoroughly reorganised their administration at Dublin Castle, including the appointment of Colonel Ormonde Winter as chief of a new Combined Intelligence Service (CIS) for Ireland. Working closely with Sir Basil Thomson

Sir Basil Home Thomson, (21 April 1861 – 26 March 1939) was a British colonial administrator and prison governor, who was head of Metropolitan Police CID during World War I. This gave him a key role in arresting wartime spies, and he was clos ...

, Director of Civil Intelligence in the British Home Office, with Colonel Hill Dillon, Chief of British Military Intelligence in Ireland, and with the local British Secret Service Head of Station, "Count Sevigné" at Dublin Castle, Winter began to import dozens of professional secret service agents from all parts of the British Empire into Ireland to track down IRA volunteers and Sinn Féin leaders.

Treacy and Breen were again relocated to Dublin, in the "Squad". Its mission was to discover and assassinate British secret agents, political policemen and their informants, and to carry out other special missions for GHQ. With help from police inspectors brought up to Dublin from Tipperary, CIS spotted Treacy and Breen and placed them under surveillance.

Death

tout

A tout is any person who solicits business or employment in a persistent and annoying manner (generally equivalent to a ''solicitor'' or '' barker'' in American English, or a ''spruiker'' in Australian English).

An example would be a person who ...

, Robert Pike. In the ensuing shootout, two Royal Field Artillery

The Royal Field Artillery (RFA) of the British Army provided close artillery support for the infantry. It came into being when created as a distinct arm of the Royal Regiment of Artillery on 1 July 1899, serving alongside the other two arms of t ...

officers, Major Smyth and Captain White, were wounded and died the next day, while Breen was seriously wounded. Carolan, who worked at the nearby St Patrick's Teacher Training College, was shot in the neck during the crossfire which occurred during the shootout. Treacy and Breen managed to escape through a window and shot their way through the police cordon. The injured Breen was spirited away to Dublin's Mater Hospital where he was admitted using a false name. Treacy had been wounded but not seriously.

The British began to search for the two and Collins ordered the Squad to guard them while plans were laid for Treacy to be exfiltrated from the Dublin metropolitan area. Treacy hoped to return to Tipperary. Realising that the major thoroughfares would be under surveillance, he bought a bicycle with the intention of cycling home by back roads. When Collins learned that a public funeral for the two officers killed at Fernside was to take place on 14 October, he ordered the Squad to set up along the procession route and to take out two powerful men, the Chief Secretary for Ireland

The Chief Secretary for Ireland was a key political office in the British administration in Ireland. Nominally subordinate to the Lord Lieutenant, and officially the "Chief Secretary to the Lord Lieutenant", from the early 19th century un ...

Hamar Greenwood and Lieutenant-General Henry Hugh Tudor

Lieutenant-General Sir Henry Hugh Tudor, KCB, CMG (14 March 1871 – 25 September 1965) was a British soldier who fought as a junior officer in the Second Boer War (1899–1902), and as a senior officer in the First World War (1914–18), b ...

, who had established the Black and Tans

Black is a color which results from the absence or complete absorption of visible light. It is an achromatic color, without hue, like white and grey. It is often used symbolically or figuratively to represent darkness. Black and white have ...

.

Several members of the Squad assembled at a Dublin safe house, the Republican Outfitters shop at 94 Talbot Street

Talbot Street (; ) is a city-centre street located on Dublin's Northside, near to Dublin Connolly railway station. It was laid out in the 1840s and a number of 19th-century buildings still survive. The Irish Life Mall is on the street.

Locati ...

early on 14 October in preparation for this operation. Treacy was to join them for his own protection, but arrived late, to discover that Collins had cancelled the attack. Treacy was extremely distressed — he and his closest friend, Dan Breen, each thought that the other had been killed. Breen had managed to get away, his feet cut to ribbons by the glass of Professor Carolan's greenhouse, and was now being hidden by the medical staff in a nearby hospital.

While the others quietly dispersed, Treacy lingered behind in the shop. But he had been followed by an informer, and a British Secret Service surveillance team led by Major Carew and Lt Gilbert Price was stalking him in the hope that he would lead them to Collins or to other high-value IRA targets.

Treacy realised that he was being followed, and ran for his bicycle. But he grabbed the wrong bike — taking a machine far too big for him — and fell. Price drew his pistol and closed in. Treacy drew his parabellum automatic pistol and shot Price and another British agent before he was hit in the head, dying instantly. Rushing to the scene, Winter was horrified to see the bodies of Treacy and his own agents lying dead in Talbot Street.

The entire confrontation had been witnessed by a 15-year-old Dublin trainee photographer, John J. Horgan, who captured the scene moments after the shooting, showing Treacy lying dead on the pavement and Price propped up against a doorway a few feet away. Making a statement to a reporter, Winter called the event "a tragedy".

British forces immediately attacked the Republican Outfitters shop, riddling the shop with bullets and throwing Mills Bombs inside to wreck it.

Legacy

Treacy's death sent alarm bells through the upper echelons of the IRA leadership.

A commemorative plaque above the door of 94 Talbot Street, now the Wooden Whisk and directly across from Talbot House, commemorates the spot where Treacy died. His coffin arrived by train at Limerick Junction station and was accompanied to St Nicholas Church, Solohead by an immense crowd of Tipperary people. He was buried at Kilfeacle graveyard, where, despite a large presence of British military personnel, a volley of shots was fired over the grave.

Treacy is remembered each year on the anniversary of his death at a commemoration ceremony in Kilfeacle. At noon on the day of any All-Ireland Senior Hurling Final in which Tipperary participate, a ceremony of remembrance is held at the spot in Talbot Street, Dublin where he died, attended mainly by people from West Tipperary and Dublin people of Tipperary extraction. The most recent ceremonies were held at on Sunday 4 September 2016 and 18 August 2019, each attracting a large attendance of Tipperary folk en route to Croke Park. The ceremony usually consists of the reading of the

Treacy's death sent alarm bells through the upper echelons of the IRA leadership.

A commemorative plaque above the door of 94 Talbot Street, now the Wooden Whisk and directly across from Talbot House, commemorates the spot where Treacy died. His coffin arrived by train at Limerick Junction station and was accompanied to St Nicholas Church, Solohead by an immense crowd of Tipperary people. He was buried at Kilfeacle graveyard, where, despite a large presence of British military personnel, a volley of shots was fired over the grave.

Treacy is remembered each year on the anniversary of his death at a commemoration ceremony in Kilfeacle. At noon on the day of any All-Ireland Senior Hurling Final in which Tipperary participate, a ceremony of remembrance is held at the spot in Talbot Street, Dublin where he died, attended mainly by people from West Tipperary and Dublin people of Tipperary extraction. The most recent ceremonies were held at on Sunday 4 September 2016 and 18 August 2019, each attracting a large attendance of Tipperary folk en route to Croke Park. The ceremony usually consists of the reading of the Proclamation of the Irish Republic

A proclamation (Lat. ''proclamare'', to make public by announcement) is an official declaration issued by a person of authority to make certain announcements known. Proclamations are currently used within the governing framework of some nations ...

, a recitation of a decade of the rosary in Irish, singing of 'Tipperary so far away', an oration by one of the organising party and the playing of the Irish National Anthem. The first event took place in 1922 and has been held on almost 30 occasions.

In Thurles

Thurles (; ''Durlas Éile'') is a town in County Tipperary, Ireland. It is located in the civil parish of the same name in the barony of Eliogarty and in the ecclesiastical parish of Thurles (Roman Catholic parish), Thurles. The cathedral ch ...

, Co Tipperary Seán Treacy Avenue is named after him. The town of Tipperary is home to the Seán Treacy Memorial Swimming Pool, which contains many historic items related to the Easter Rising

The Easter Rising ( ga, Éirí Amach na Cásca), also known as the Easter Rebellion, was an armed insurrection in Ireland during Easter Week in April 1916. The Rising was launched by Irish republicans against British rule in Ireland with the a ...

and the War of Independence, and a copy of the Proclamation of the Irish Republic

A proclamation (Lat. ''proclamare'', to make public by announcement) is an official declaration issued by a person of authority to make certain announcements known. Proclamations are currently used within the governing framework of some nations ...

. The Seán Treacy GAA Club takes his name in honour and represents the parish of Hollyford, Kilcommon and Rearcross in the Slieve Felim Hills, which straddle the borderland between the historical North and South Ridings of Tipperary. He is remembered in many songs. The song ''Seán Treacy'', also called ''Tipperary so Far Away'', is about Treacy's death and is still sung with pride in west Tipperary. A line from this song was quoted by former US president Ronald Reagan when he visited Tipperary in 1984: "''And I'll never more roam, from my own native home, in Tipperary so far away''"., Tipperay by US President Ronald Reagan, June 3, 1984 The song most closely identified with him, ''Seán Treacy and Dan Breen'' commemorates his and Breen's escape from Fernside, and mourns his death:

Give me a Parabellum and a bandolier of shells, Take me to the Murder Gang and I'll blow them all to hell, For just today, I heard them say that Treacy met defeat, Our lovely Séan is dead and gone, shot down in Talbot Street. They were at the front and at the back; they were all around the place. None of them anxious to attack; or meet him face to face. Lloyd George did say, "You'll get your pay - and a holiday most complete", But none of them knew what they would go through, in that house in Talbot Street. When he saw them in their Crossley trucks, like the fox inside his lair, Seán waited for to size them up before he did emerge, With blazing guns he met the Huns, and forced them to retreat, He shot them in pairs coming down the stairs, in that house in Talbot Street. "Come on", he cried, "'Come show your hand, you have boasted for so long, How you would crush this rebel band with your armies great and strong". "No surrender", was his war cry, "Fight on lads, no retreat" Brave Treacy cried before he died, shot down in Talbot Street.

Footnotes and References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * *External links

at www.clarelibrary.ie

at republican-news.org

at homepage.eircom.net

* ttp://www.helensfamilytrees.com/treg03.htm Helen's Family Trees (Treacy page)*

Sean Treacy & Talbot street

{{DEFAULTSORT:Treacy, Sean 1895 births 1920 deaths Irish Republican Army (1919–1922) members Members of the Irish Republican Brotherhood People from County Tipperary Irish Republicans killed during the Irish War of Independence People killed in United Kingdom intelligence operations